András György Kovács[1] - Gergely Barabás[2]: Why Judicial Independence Matters? (ELTE Law, 2018/2., 127-155. o.)

Administrative Judiciary: the Transmission Point Between National and EU Law

I. Introduction

This paper shows that the trends in Hungarian requests for preliminary ruling proceedings, which constitute the main connection and transmission point between national and EU law, are strongly determined by administrative justice. Our premise is that, if there are challenges to the perception of administrative judicial independence, those are likely to lead to the disengagement of national and EU law. The number and trends of references for preliminary rulings can be one but not the exclusive litmus test of judicial independence. In our view, the independence of the administrative judiciary is a cardinal and strategic issue for both the European Union and Hungary. The Hungarian EU law judicial advisors (members of ELAN) have had a decisive role in the implementation of EU law, though the centralisation of their network in 2013 has not yet had a significant impact on the quality of references. The study states that conclusions on the independence and impartiality of administrative justice can only be drawn from at least a seven-year period of administrative judicial case-law related to the initiation of preliminary rulings.

The paper discusses the essential characteristics of preliminary rulings given on the initiative of Hungarian administrative courts since the accession of Hungary to the European Union in 2004 until 2018. The text summarises the implications of these references to the ECJ for preliminary rulings on the depth of the harmonisation of EU law, as well as on the role of Hungarian administrative jurisdiction in the implementation of EU law.

For this purpose, we have compiled a database of 170 queries with 158 lines and grouped the data into 9 columns. The database contains all the data on Hungarian references for preliminary ruling procedures that are relevant for the evaluation of administrative case law.

- 127/128 -

We have also collected the additional comparative data needed to evaluate the data from this database. The data were obtained from EUR-Lex (https://eur-lex.europa.eu) and were individually assessed.

It is worth remarking, regarding the methodology, that the database contains all Hungarian references, irrespective of whether a judgment or order was rendered at the end of the procedure or it is pending. Still, the aggregated data of EU Member States and the data of the countries in the CEE region are not exactly the same due to inconsistent inputs or input errors in the EUR-Lex database.[1] There is a certain degree of inaccuracy in the data for the European Union as a whole and for other countries (although we attempted to refine the data using several types of control searches), so the Hungarian data used for comparison were not exactly the same as the data collected in our detailed database. However, the difference between the data with the same parameter is in reality 1-2 judgments or orders per country of the total processed 15-year data. We therefore did not focus on the specific numbers, which may be inaccurate by some minor margin of error, but rather on tendencies, shifts and trends. Hence, accurate data are indicated only where the exactness of the data is beyond any doubt and its reliability - based on control queries - is unquestionable.

It must be noted that we have written this paper as EU law judicial advisors[2] and administrative law judges, with more than 20 and nearly 10 years of judicial experience at various levels of administrative justice. We - as referring courts - have submitted more than 10% (10) of the overall Hungarian administrative court requests (98) for preliminary rulings in the last 15 years. As such, the paper contains some background information and assessments of the effects of the cases on the judiciary and national case law - whether we were directly involved or not -which are not publicly available or only partially accessible. Various data cannot be quantified precisely in the absence of suitable domestic databases. Accordingly, several pieces of information are not verifiable by scientific methodology or only partially verifiable, but we believe that our expertise can be an interesting and useful supplement to the scientific discourse on preliminary ruling proceedings. Hence, we did not refrain from sharing and using such less scientifically verifiable information; however, we make the anecdotal non-scientific nature of this kind of information recognizable in this paper. In some respects, we have also been forced to override the traditional dogmatic interpretations in favour of a narrative methodology.[3]

- 128/129 -

II. The Place of Administrative Case Law in Preliminary Rulings

1. Preliminary Rulings in General

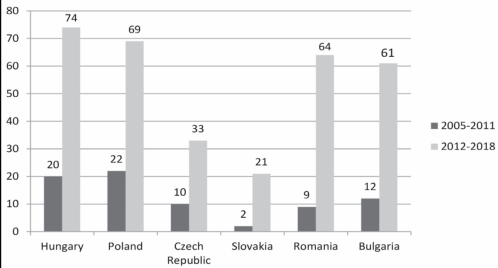

The history of requests for preliminary rulings in Hungary can be divided into two 7-year periods based on the number of judgments of the ECJ: 2005-2011 (hereinafter referred to as 'period I') and 2012-2018 (hereinafter referred to as 'period II'). Between 2005 and 2011, annually less than 3 (totally 20) judgments of the ECJ were given on the initiative of Hungarian courts on average, while between 2012 and 2018 it was annually more than 10 (altogether 74). It means that the number of the judgments in the second phase more than tripled (3.65). In the case of period II judgments, requests for preliminary rulings were made from 2010. An upward trend in the number of references could be traced from 2011. The requests have steadily and continuously increased in the past few years; the number of ongoing procedures and requests submitted in 2018 are especially high.[4] In general, the total number of judgments of the ECJ has increased by 50% between the two periods. Accordingly, the judgments delivered on the initiative of Hungarian courts increased fourfold, from 0.5% to almost 3.5% of all ECJ judgments. This ratio is significantly higher than many relevant indicators connected to the number of cases would suggest (population / 1.9% / GDP / 0.8%).[5]

It would be an oversimplification to explain the above-mentioned trends either with the establishment of the constitutional system in 2010, which is politically based on a dominantparty public law system[6] ('dominant party with a competitive fringe'), or with the political confrontation with EU institutions. Even though the cases of period II stem from 2010 and after, the factual basis of these cases dates back to the pre-2010 period. Also, the number of judgments of the ECJ was already on the rise by then. A number of factors can explain this rise. Among others, the expansion of the volume and scope of applicable EU law, wider and deeper integration, the growing tension between the EU institutions and the interests of the Member States (not only Hungary), as well as the internal tensions within the EU institutional system, all contributed to the rise. Consequently, we checked these numbers in the other members of the V4 states joining the EU with Hungary in 2004, along with the data for Romania and Bulgaria that joined later.

In the first period, the average number of judgments per year in Poland was slightly above 3, while in the second, it was moderately below 10, which is slightly more than a threefold (3.13.) increase. The Czech data shows a multiple of 3.3, the Romanian a 4.06 rise (where the first judgment of the ECJ appears in 2008), while the Bulgarian data almost triples (2.9). In this

- 129/130 -

respect, the result in Slovakia is staggering. There were some unsuccessful requests in the first period (3 cases closed by order), and only one request was qualified admissible in 2011. The ten-fold (10.5) increase from such a low base is not surprising and it still means only 3 judgments on average per year. In the case of Slovakia, the lack of successful requests for preliminary ruling procedures in the first period is due to the brevity of its pre-accession period and the consequent delay in adapting the judicial system to EU law compared to other Eastern European countries.[7] If we ignore the data for Slovakia as being an outlier, the Hungarian data of period II are not so surprising and they not only fit the general phenomenon of growth in the European Union, but also that of the Eastern European region, characterised by a three- or fourfold increase. This implies that the first period can be considered as a learning or training period, while the second one is a mature phase of consolidation and adaptation of the national judicial system to EU law.

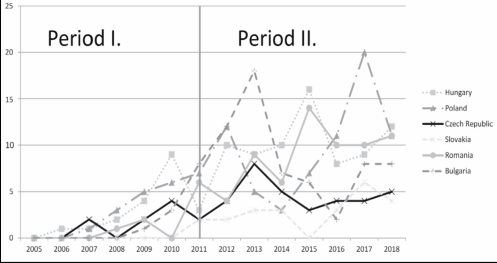

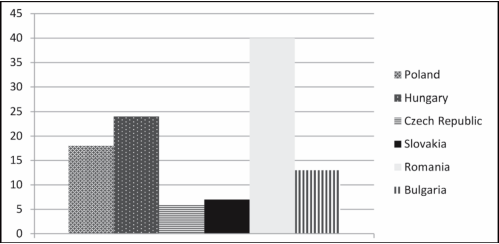

Chart 1. Number of ECJ judgments according to referring countries (2005-2018)

As demonstrated, there is one outlying data concerning Hungary in period I, the 9 judgments in 2010, which may be explained by the emergence of disputes concerning agricultural subsidies based directly on EU regulations (2 out of 9 judgments). Otherwise, in Hungary, the period 2012-2018 shows a constant rise. Although the chart illustrates some minor leaps in other countries, there is a clear upward trend in the last three years (2016-2018) in Poland, in the last four years in Romania (2015-2018), and in a four-year period in Bulgaria (2011-2014) peaking in 2012-2013. The number of requests for preliminary ruling proceedings remains relatively stable and high after that. As for the Czech Republic and Slovakia, there is a slow but steady increase with some irregular peaks in the number of references, taking into account that there

- 130/131 -

were no successful - i.e. admissible - requests until 2011 in Slovakia. The fact that in Poland the upward trend materialised just after the parliamentary elections in 2015, when serious tensions emerged due to the intervention in the justice system triggering an Article 7 procedure, raises suspicion about the correlation. This is also true in the case of Hungary, as the intention to transform the Hungarian court system had become apparent from April 2011. However, it may be a coincidence, especially taking the Romanian data into account, which weakens the former explanation, as it cannot be explained by such interventions. We have also seen that there are no fractures in the Czech data; the number of judgments shows a similar growth rate for the same period as for Hungary and Poland.

despite the fact that a clear conclusion cannot be drawn from the trend change in period II, both the Hungarian legal theory[8] and the case law-study group of the Curia[9] have already noted that, among those countries that joined in 2004, the number of requests for preliminary rulings initiated by Hungarian courts is the highest. The Hungarian cases account for 3.5% of all judgments given by the ECJ, which is basically the same as the Polish data and more than double the Czech data, while the fall-off in the Slovakian data is proportional to the size (and population) of the country.

Chart2. Number of ECJ judgments according to referring countries (2005-2018) in Period I. and Period II.

- 131/132 -

These data can be explained by structural (population, willingness to litigate, level of compliance with EU law) and non-structural, country-specific factors.[10] Although structural factors have some explanatory power, the significant deviations from the trend suggest that non-structural factors also play a significant role.[11] The larger the population, the higher the number of requests for preliminary rulings. Hungary is on the trendline,[12] so the data from other Eastern European countries seem to be low. However, any misconception that Hungary stands out in the region due to a high willingness to litigate should be dispelled. Analysing the number of administrative cases per 100 inhabitants in 2016, which we have compared with 2012 data (in the case of the Czech Republic, those of 2014) the rate is 0.2 in Hungary, 0.2 in Poland and 0.16 in Slovakia. The Romanian 0.6 and Bulgarian 0.35 rates are significantly higher, while the Czech willingness to litigate (0.11) is indeed significantly lower. The correlation coefficient is 0.441 between the number of the judgments of the ECJ in period II and the number of administrative cases per 100 inhabitants in 2016.[13] This is a weak relationship and cannot establish a causal connection. Ongoing infringement procedures are often used as an indicator for the level of compliance with EU law, but it does not constitute a high figure in Hungary either.[14]

Accordingly, these data do not confirm that the change in the political system in Hungary after 2010 had significant impact on the growing trend for requests for preliminary ruling proceedings and on the relationship between EU and national law. Therefore, it seems necessary to dig deeper, as well as to identify the cases of references influenced by the political change in 2010 by means of a qualitative analysis and finally to show the summary of the structural effects, if there are any.

The number of requests for preliminary ruling procedures can be influenced by non-structural, country-specific factors, such as language skills, specialised training, judicial preparedness for the enforcement of EU law, national judges' attitude towards parties' initiatives and the time and cost of such proceedings before the ECJ.[15] The first three issues are going to be discussed in Chapter 3, while in Chapter 4 we turning to other issues explored by the legal literature on preliminary rulings, such as turf wars inside the judiciary.

2. The Weight of Administrative Cases in the Number of Requests for Preliminary Rulings

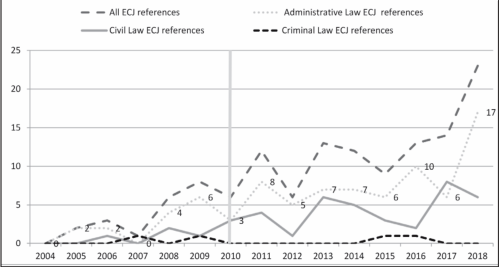

In Hungary, 2/3 of the requests for preliminary ruling procedures are referred to the ECJ by administrative courts, whether based on the number of requests (65.6%) judgments of the ECJ (64.5% and 66.3%[16]), or even pending cases (63.3%).

- 132/133 -

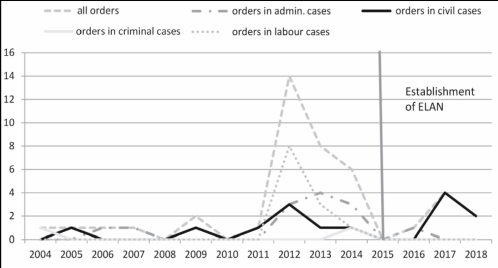

Chart 3. Number of successful and ongoing Hungarian courts requests to ECJ according to the nature of cases and all in each year

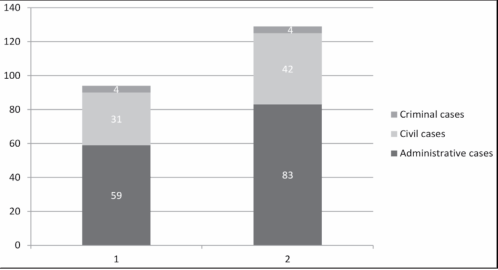

Chart 4. ECJ judgments delivered on the initiative of Hungarian courts and successful and ongoing procedures according to the nature of cases (2004-2018)

The charts show that no successful request has been submitted by Hungarian labour courts since 2004. Regarding criminal cases, there were 4 requests and 4 judgments of the Court. Accordingly, administrative and civil courts dominate the requests for preliminary rulings in

- 133/134 -

a 3:1 ratio. This not only shows the overwhelming importance of administrative justice in the enforcement of EU law, but it also proves that administrative courts in Hungary determine the trends of requests for preliminary rulings.

In addition, 16.6% of the 42 civil court requests were partly related to administrative matters. For example, the judgment of the Court (C-56/13) concerning compensation for damages caused in the exercise of public authority in relation to measures controlling avian influenza,[17] or the Incyte Corporation case (C-492/16) could both be considered from a theoretical point of view as administrative cases.[18] In this latter case, the National Intellectual Property office refused to grant the rectification of the date of expiry of a supplementary protection certificate for a medicinal product developed by Incyte. Furthermore, we include among the administrative law-related matters three public procurement cases, one case on the regulation of the gambling market, and the Eurospeed case (C-287/14)[19] which concerned compensation for the damage resulting from fines imposed by szeged Administrative and Labour Court.

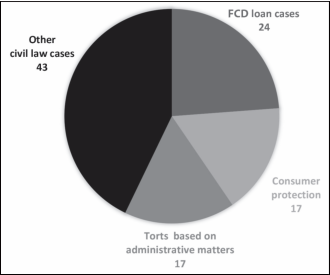

Chart 5. Types of request for preliminary ruling procedures made by civil courts (2004-2018, percentage)

Considering that nearly 25% of the references made by civil courts were brought before the Court in the so-called 'foreign currency-denominated loan cases' ('FCD loan cases' in the graph), linked to a specific and unique legal and social situation, we can assume that the implementation of EU law is primarily based on administrative justice in Hungary. This observation is

- 134/135 -

confirmed by the fact that the criminal and a third of the civil cases classified as 'other civil law cases' (6 of 18 [42% on the graph]) in the above graph are related to subject matters that can be subject to classic international agreements. These do not require the level of integration already achieved in the EU, even if their enforcement is more effective as EU law. These matters include cases of jurisdiction in civil matters, mutual recognition of judgments and judicial cooperation, which are traditionally international private law matters, regulating the relationships between natural and legal persons of different nationalities. Beyond these international private law issues, civil courts promote EU integration by deciding compensation claims for damages due to EU law infringements,[20] and with the enforcement of the four basic freedoms and consumer protection regulations. An emerging area is the private enforcement of competition law, including litigation on prohibited state aid. In this regard, the first two requests have already been submitted before the ECJ (C-451/18 and C-672/13)[21]. This means that, in the end, civil courts are expected to implement important EU policy, even if the number of cases is not expected to reach that of foreign currency-denominated loan cases. These have been 60% of the requests for preliminary rulings filed by Hungarian civil courts (10 + 7 + 7 = 24 cases between 2004 and 2018).

In contrast, administrative law cases requiring preliminary rulings directly concern the policies of the EU as, in the implementation of EU law, Member States' public administrations are essentially orientated by the case law of national administrative courts. While civil court judges meet EU law in a small, but rapidly rising percentage of the cases, dealing with EU law has become commonplace for administrative law judges. In addition, the types of cases invoking EU law are usually the more difficult and complex ones (public procurement, competition law, environmental protection, tax law) and cover - at least in Budapest - cca. 70% of the overall number of cases.[22] Hungarian judges apply national law in the light of EU law every day; where necessary, they also routinely set aside national law in favour of EU law without a reference for preliminary ruling. Furthermore, cases referred for preliminary ruling generally affect several other cases, as the same legal question often appears at the same time in different cases. While the ECJ has never joined civil court cases, six joined administrative cases (including withdrawn references involving two pairs of joined cases 2-2 cases) were judged by the ECJ. The number of withdrawn requests may therefore indicate that the same legal question is at issue in ongoing cases before the national courts. For example, two of the four

- 135/136 -

withdrawn administrative cases concerned the nature of HIPA, the local business tax (joined cases C-283/06, C-312/06).[23]

In our view, the independence of the administrative judiciary is a cardinal and strategic issue for the European Union and Hungary. This statement can be supported by the thorough analysis of preliminary ruling procedures in this article. The interaction between EU and national law would cease to exist without the independence of administrative courts, which is likely to lead to the creation of a colonial-type, isolated coexistence of the two legal systems.[24] Our conviction is that it is neither in the interest of Member States nor in the interest of the EU.

III. Quality of References in Administrative Cases

It is worth exploring briefly how effective the relationship between national and EU law is. Perhaps the best indicator for this is a comparison of cases ending with judgment and order. One in five (18.9%) requests concerning administrative matters, and one in three civil cases (31.8%) have ended with an order. Although 33% of criminal cases were closed by an order, it only means that 2 out of 6 requests were unsuccessful, while all the 12 references regarding labour cases resulted in an order.

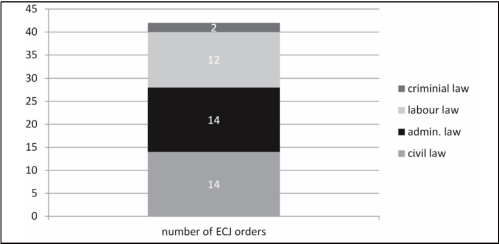

Chart 6. All ECJ orders according to judicial branches (2004-2018, Hungary)

- 136/137 -

The content of orders varies greatly; therefore it is difficult to draw a clear conclusion from these numbers. Some of them contain substantive answers, where the referring court had not recognised that there already was clear case-law in that matter. In these cases, as in those of withdrawal of a reference, ECJ case-law often develops after the request. As such, we cannot reach an unambiguous conclusion about quality problems. A more accurate conclusion can be drawn from orders based on manifest inadmissibility or lack of jurisdiction. All orders delivered on requests for preliminary ruling submitted by the Hungarian labour courts in 2012-2013 concerned the dismissal of civil servants without justification. The abundance of the references was a judicial reaction to the new legislation adopted by the new government in 2010. The Hungarian Constitutional Court annulled the provisions in question 'pro futuro', which did not remedy the situation of the government employees concerned.[25] The referring courts (Curia, Budapest Metropolitan Court, Administrative and Labour Court of Budapest and Debrecen), which had just been placed under institutional reform at that time, expected the restoration of rule of law and the implementation of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union. The ECJ dismissed these requests on the ground of lack of jurisdiction, owing to the inapplicability of the Charter, since the legal context of the dismissal of the civil servants did not concern the implementation of EU law. A possible explanation for this outcome is that Hungarian labour court judges were not sufficiently prepared to cope with EU law matters, but the truth is that the scope of the Charter was rather equivocal at that time. The Akerberg Fransson judgment was only delivered on 26 February 2013 (C-617/10) and until then it was ambiguous whether the fundamental rule of law guarantees would be enforceable by EU law.[26]

This argument is confirmed by case C-45/14.[27] The ECJ dismissed a reference for a preliminary ruling submitted by a Hungarian criminal court based on manifest lack of jurisdiction of the Court because of the inapplicability of the Charter. The other - and the first Hungarian - reference for a preliminary ruling made in criminal proceedings, was in the Vajnai case (C-328/04).[28] The request concerned the interpretation of the principle of non-discrimination as a fundamental principle of EU law in the course of criminal proceedings brought against Mr. Vajnai for the violation of the Hungarian Criminal Code, which sanctioned the use of 'totalitarian symbols' (the five-point red star) in public. The ECJ stated that it had no jurisdiction over national provisions outside the scope of EU law and in cases when the subject matter of the dispute is not connected in any way to any of the situations contemplated by the treaties. It was clear for the Court that Mr Vajnai's situation was not connected in any way to any of the situations contemplated by the provisions of the treaties and the Hungarian provisions applied in the main proceedings were outside the scope of EU law. The legal assessment of the use of the five-point red star in public was not at all uniform in the Hungarian and European practice and theory. In the end, the ECtHR and not the CJEU solved

- 137/138 -

the problem - again.[29] In our opinion, it is not possible to draw a general conclusion from these cases, because the relatively high proportion number of orders the Court delivered on the initiative of Hungarian criminal courts was due to the small number of references and not to inadequate preparation. The occurrence of some false erroneous references is in fact the sign of the proper functioning of the judiciary. Occasional mistakes must not prevent national courts from exercising their powers guaranteed by the treaties.

However, the slightly lower level of preparedness of civil judges compared to that of administrative law judges can be demonstrated by the 1:5 to 1:3 ratio of the 74 administrative and 44 civil court orders received on reference. This observation is supported by the fact that only 2.7% of the administrative law requests were dismissed based on manifest inadmissibility or lack of jurisdiction of the Court, while in civil matters 11.3% of the references fall into this category. The proportion of reasoned orders[30] is the same regarding administrative (8%) and civil (9%) cases. The latter data may indicate that the interpretation of the referring court and the ECJ on the existence of relevant practice differs once in every 10 cases. This incidence seems acceptable. The remaining orders concerned either cases with a factual basis from Hungary's pre-accession period or withdrawn references, from which it is impossible to draw exact conclusions. The quality of the references is not measurable based on withdrawn cases, which is well-illustrated by cases C-447/06 and C-195/07 related to local business tax.[31] The Court delivered its judgment in the joined cases C-283/06 and C-312/06.[32] The fact of the withdrawal in these cases shows only that the same legal issue arose in several cases in the national practice of the taxation authorities, which can result in simultaneous requests. For the sake of comparison, we looked at the number of orders in the EUR-Lex database with the search criteria of 'country of origin' and discovered that the number of orders in Romania is peaking, while the number of orders in Polish cases is slightly lower. All in all, we might also conclude, based on the available data, that the slightly weaker Hungarian performance can be attributed to the weaker performance of civil courts. The real question is, however, whether this is just a weaker performance during an initial period and the courts will improve or the capabilities capacity of the courts will stay as they are.

In Hungary, due to the specific linguistic conditions, the level of foreign language proficiency is lower than in other Member States. The Hungarian judicial system has been trying to eliminate this disadvantage by establishing the institution of the ELAN. In 1999, 46 judges were appointed as national trainers and by 2002 this trainer network consisted of 58 judges. In 2009, the participating judges were awarded the title of European law judicial

- 138/139 -

advisor; their role is to provide professional advice to judges in EU law matters. The centralisation of the network was completed in 2013, after the 12 requests for preliminary rulings submitted by Hungarian labour courts were dismissed for lack of jurisdiction. The network is chaired by the President of National Office for the Judiciary. Its actual operation can be evaluated from 2015 on the following graph.

Chart 7. Number of orders according to country of origin (2004-2018) without withdrawn cases[33]

Chart 8. Preliminary ruling procedures ending with order according to judicial branches (2004-2018)

- 139/140 -

While the number of references has not decreased, the number of requests ending with an order has decreased significantly. Due to the low number of criminal cases, no meaningful conclusion can be drawn for criminal courts, but the number of administrative and labour law references ending with an order has reduced to almost zero. In 2014, the Court dismissed two - very poor quality - administrative law requests for preliminary rulings on the ground of manifest inadmissibility, while in 2015 the Court delivered one reasoned order on the initiation of one of the administrative law panels comprising a European law judicial advisor (C-28/16), by qualifying the referred questions as 'acte clair'. The occasional and rare occurrence of such cases is not a mistake, but rather the normal operation and dialogue between the ECJ and national courts. However, this is not the case for civil courts' requests.

One of the requests for preliminary ruling in 2014 resulting in manifest inadmissibility was known to the ELAN, but the newly appointed judicial advisor was insufficiently prepared and gave inappropriate advice.[34] The other case where the reference was manifestly unfounded on several grounds was completely out of sight of the network.[35] Orders delivered by the Court based on manifest inadmissibility or lack of jurisdiction indicate a malfunction in the network. There are two causes: either the judicial advisor can reach the judge opting for referring questions to the Court but does not give proper advice, or the advisor cannot even reach the referring judge. It can be clearly seen from the above chart that in 2017-2018 there were six orders in civil cases, two of which were reasoned orders, while three others were completely and one was partly manifestly inadmissible. In our view, this implies that the network operates efficiently where it has been configured in a matrix system, meaning that all court levels and judicial communities are covered by at least one judicial advisor. This was feasible in the relatively small administrative law judge community (100-120 judges)[36], while such access to the numerous (several thousand) civil and criminal law judges was not possible. In addition, since the centralisation, the network has become a self-training group of civil and criminal law counsellor judges, who put more emphasis on judicial advisors' professional training than on providing EU law advice.

- 140/141 -

IV. Requests for Preliminary Ruling Procedures According to Levels of the Hungarian Judicial System

Between 2004 and 2013, there were three administrative court levels. General courts at county level heard administrative cases in the first instance. The Regional Court of Budapest heard appeals brought against decisions delivered by general courts. The Supreme Court was the supreme and final judicial body of Hungary, hearing motions for review in administrative matters, ensuring that courts apply the law uniformly, and adopting law harmonisation decisions binding on all courts. Since 2013, administrative and labour courts have been operating in the first instance. Until the end of 2017, general courts heard appeals delivered by administrative and labour courts in cases specified by law. The Curia (The name of Supreme Court from 2012) and its administrative section is the supreme administrative judicial body in Hungary. The general appeal function of general courts ceased to exist from 2018, and the Budapest Metropolitan Court became the first instance administrative court in priority administrative cases, such as public procurements, competition law and media law. Meanwhile 8 of the 20 administrative and labour courts were transformed into general first instance administrative courts hearing 95% of administrative cases.

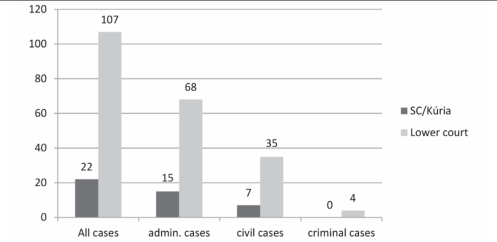

For the purposes of Article 267 TFEU, it is important to distinguish between the Curia taking the final decision in most of the cases and the other lower courts. 15 of 22 requests made by the Curia resulting in a judgment before the Court were submitted by the administrative, and 7 by the civil section of the Curia, while 68 of 106 references judged on the initiation of lower courts belonged to the administrative branch, 7 (as seen below in the graph) concerned civil law and 3 in criminal cases. 18% of the references belonged to the Curia in administrative, and 16% in civil matters. It follows that the large number of requests was due to the overwhelming activity of lower courts.

Chart 9. References according to judicial instances (2004-2018)

- 141/142 -

In period I, there was only one Supreme Court request, in 2006, which followed the references of the lower courts relating to local business tax (C-283/06 C-312/06 Joined Cases)[37] and was joined to the request made by a lower court in Zala County. All other requests were submitted in period II. The number of administrative law requests started to increase in 2011. This shows that the activity of the lower courts has triggered the sensitivity of the Supreme Court to EU law, even though the difference in time can also be partly explained by the fact that the first cases in which applications concerned European law were brought only later before the supreme judicial body. Half of the references are VAT cases, except for the first local business tax case. in addition, requests concern competition law (2), state aid (2), consumer protection (1), immigration policy (1) and data protection (1). Five of the taxation cases stem from the administrative panel of the Curia (Supreme Court), one of whose members is the European advisor judge of the Curia while five of the references concerning 'classic' administrative law fields were initiated by the administrative panel, a member of which is responsible for the coordination of European law advisor administrative judges (one of this publication's writer). A few more references emerged from other panels, which reflect the continuous development of implementing EU law in the national case law.

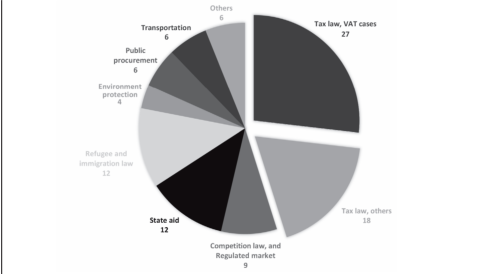

Chart 10. Percentage of administrative law references (successful and ongoing) for preliminary ruling procedures according to the nature of the case (2004-2018)

It is clear that every 4th reference (every 5th judgment) is related to VAT. A third of the judgments (37.45%) and about half of the references (45.12%) concern tax matters. During the same period, 18.02% of all the judgments of the ECJ concerned tax law, which shows that tax

- 142/143 -

law requests outweigh all other fields of law in the Hungarian practice (or the number is too low in other cases). VAT cases are followed by (agricultural) state aid cases (10), which relate to a field of law totally governed by directly applicable regulations, so almost each case requires the interpretation of EU law. Then come a relatively large number of requests concerning asylum and immigration policy, and competition law in a broad sense.

V. Evaluation of References According to Fields of Law

1. Taxation and Customs

There are 26 judgments given by the ECJ and 8 preliminary ruling procedures are pending in the field of taxation and customs. Most of the cases are VAT cases. In this field, 22 references were submitted; 5 of them are still pending and the ECJ has given 16 judgments representing 60% of all tax and customs cases. In most of these cases, tax authorities refused to allow the right to deduct input value added tax (VAT) on transactions considered to be suspicious. According to the applicable Taxation Act, the right of deduction may only be exercised by persons who hold documentation attesting to the amount of tax charged. Invoices, simplified invoices and documents that take the place of an invoice, made out in the name of the taxable person, are to be considered to constitute such documentation. In addition, Paragraph 44(5) of the VAT Act provides that the issuer of the invoice or simplified invoice shall be responsible for the veracity of the information given therein. According to the ECJ, the prevention of possible tax evasion, avoidance and abuse is an objective recognised and encouraged by EU law and it cannot be relied on for abusive or fraudulent ends. Therefore, it is a matter for the national authorities and courts to refuse to allow the right to deduct where it is established, based on objective evidence that the right is being relied on for fraudulent or abusive ends. A taxable person can be refused the benefit of the right to deduct if it is established, on the basis of objective factors that the taxable person knew, or ought to have known, that that transaction was connected with fraud previously committed by the supplier or another trader at an earlier stage in the transaction. We have to add that this had already been a well-known problem in Hungarian theory and practice before the accession to EU.[38]

The phrase 'the issuer of the invoice shall be responsible' in Paragraph 44(5) was considered by Hungarian administrative courts as a special form of civil liability. The tax authority used this interpretation to refuse a taxable person (recipient of the invoice) the right to deduct from the VAT, which he is liable to pay, the VAT due or paid in respect of services supplied to him. The ground for this was only that the issuer of the invoice relating to those services, or one of his suppliers, acted improperly, without that authority establishing that the taxable

- 143/144 -

person concerned was aware of that improper conduct or colluded in that conduct himself.[39] The Taxation Act was complemented later by the rule that the taxation rights of the taxable person indicated as the purchaser in the receipt may not be called into question if that person acted with due diligence as regards the chargeable event, bearing in mind the circumstances under which the goods were supplied or the services performed. This modification did not have a significant impact on the case-law. Although the non-payment of VAT by invoice issuer could no longer justify the refusal of VAT deduction by the taxable person, supply-chain arguments (i.e. deduction may be refused in the case of a supply chain with non-existent or improper transactions) however continued to allow this practice. despite the legislative and theoretical efforts, only the intervention of the ECJ was able to overcome these barriers.

The large number of references for preliminary ruling procedures connected to this topic show the slow process of how national authorities have changed the way they have thought about tax evasion and the right to VAT deduction. The ECJ - by means of the preliminary ruling procedure - had a key role in the transformation of national case law and administrative practice.[40] new and more effective technological devices have been developed and launched against tax evasion (for example online cash-registers and implementation of the EKAER, Electronic Trade and Transport Control System). The case law of the ECJ has made an extraordinary contribution towards the creation of a 'client-friendly' and supportive attitude by tax authorities, which were at least partly forced to leave behind the punitive approach to taxpayers.

The other smaller group of requests within taxation cases consists of industry-based discriminatory tax issues resulting directly from the political change in 2010. It includes store retail trade (Hervis 2014, national tax legislation establishing an exceptional tax on the turnover of store retail trade), advertisement tax (Google 2018) and references concerning discriminatory taxation resulting in prohibited state aid (Tesco 2018).

One of the largest ECJ judgments in terms of financial effects[41] ruled that the HIPA (local business tax) differed from VAT so much that it could not be characterized as a turnover tax for the purposes of Article 33(1) of the Sixth Directive. In the Nádasdi case, involving a wide range of other consumers, the ECJ declared that a vehicle of the same model, age, mileage and other characteristics, bought second-hand in another Member State and registered in Hungary, attracted the full rate of registration duty for that category of vehicle. The duty was thus a heavier burden on imported used vehicles than on the similar used vehicles already registered in Hungary, which have already borne that duty at an earlier stage. Thus, although the purpose of and reason for the registration were environmental in nature and unrelated to the market value of the vehicle, the consequence of the first paragraph of Article 90 EC was that account must be taken of the depreciation of used vehicles when they were being taxed. The duty was characterised by the fact that it was charged only once when the vehicle was first registered

- 144/145 -

for use in the Member State concerned and was thus incorporated in that value. The facts of these disputes were linked to period I. However, the largest taxation case ever in which a Hungarian administrative court submitted a reference for a preliminary ruling was the Webmindlicenses case in 2014. Here the taxpayer prevailed and the tax authority - again - had serious difficulties in obtaining evidence lawfully and establishing the facts.

2. Proportionality of Administrative Penalties

Four of the five cases concerning transport touch on the topic of proportionality of administrative penalties, but they overlap with taxation cases as well and so these cases may cover several issues.

The inefficiency in taking evidence on the part of the Hungarian public administration, as seen in taxation cases, is a more general problem. In transport cases, it is demonstrated by the institution of strict liability penalties, meaning a flat-rate fine for all breaches, no matter how serious they are. Recognizing the imperfections of the Hungarian administrative operation, the ECJ accepted the system of strict liability as a whole in the Urban case, but the judgment shows inconsistency. Questioning the proportionality of the punishment, it applies the 'little guilty principle. The Hungarian administrative law theory already pointed out that it is hard to compare a Danish truck driver's income level to a Hungarian truck driver's. In spite of the prohibition of discrimination on the basis of nationality, different amounts of fines could be considered proportionate according to this judgment.[42] The Urban judgment has been applied by Hungarian administrative courts with much difficulty. The inconsistency of this judgment is also obvious here: if the system of administrative penalties based on strict liability can be justified: in other words, a penalty must be imposed without any margin of appreciation and the administrative court shall not be capable of exercising judicial discretion in order to deliberate the proportionality of the fine. It is illustrated by the administrative court judgement delivered on the basis of C-384/17, which declared the imposed penalty disproportionate by setting aside the Government Decree that regulated the amount of fines for breaches of certain provisions concerning the transport of goods and persons. Instead, the court applied the provisions of the Act on Road Transport, which were not fully applicable to the case, hence their application them seems somewhat arbitrary. At same time, it is quite understandable that the court tried to create a legal framework to meet the requirements of EU law and find a national legal basis for imposing proportionate penalties.

According to the position of the ECJ (C-255/14), Article 9 (1) of Regulation (EC) No 1889/2005 on controls of cash entering or leaving the Community[43] must be interpreted as

- 145/146 -

precluding national legislation, such as that at issue in the main proceedings. The legislation in question imposed a payment of an administrative fine of up to 60% of the amount of the undeclared cash, where that sum is more than EUR 50,000, in order to penalise the failure to comply with the obligation to declare. The case again concerned the proportionality of administrative penalties. The ECJ recognised in this case that the requirement that the penalties introduced by the Member States under Article 9 of Regulation No 1889/2005 must be proportionate does not mean that the competent authorities must take account of the specific individual circumstances of each case. However, in light of the nature of the infringement concerned, namely a breach of the obligation to declare laid down in Article 3 of Regulation No 1889/2005, a fine equivalent to 60% of the amount of undeclared cash, where that amount is more than EUR 50 000, was disproportionate. Such a fine goes beyond what is necessary in order to ensure compliance with that obligation and the fulfilment of the objectives pursued by that regulation.

In nearly all fields of administrative law, the Hungarian legislation tends to solve the inefficiency of taking evidence and the lack of a comprehensive doctrine of administrative law responsibility by devising serious and non-discretionary administrative penalties, which cannot be effective.[44] However, it is likely that sooner or later the EU law will enforce the application of the results of domestic legal theory using preliminary ruling proceedings.

3. Competition Law and State Aid

Of the seven competition law cases, only two concerned agreements with an anti-competitive aim. The judgment in the Allianz case is a rare example of how EU law is shaped by national law and not vice versa. This decision made the concept of 'restriction of competition by object' fluid. According to the ECJ, in order to determine whether an agreement involves a restriction of competition 'by object, regard must be paid to the content of its provisions, its objectives and the economic and legal context of which it forms a part.[45] When determining that context, it is also appropriate to take into consideration the nature of the goods or services affected, as well as the real conditions of the functioning and structure of the market or markets in question. In addition, although the parties' intention is not a necessary factor in determining whether an agreement is restrictive, there is nothing prohibiting the competition authorities, the national courts or the Courts of the European Union from taking that factor into account.

The other case, the so-called MIF cartel case, is still pending. Nevertheless, there are only a few 'classic' competition law cases, despite the fact that even the administrative decisions

- 146/147 -

adopted exclusively on the basis of national law by the Hungarian Competition Authority are generally based on the soft law of the Commission and the case-law of the ECJ. This is also a consequence of the Allianz case, which was also based solely on national competition law. The explanation for this small number is that the ECJ has a well-established and extensive case-law in the field of competition law and so many questions can be answered without a request for a preliminary ruling. it is also typical that the parties attempt to initiate a reference for a preliminary ruling on questions of evidence (direct or circumstantial evidence, unum testis etc.), while the Hungarian administrative courts have so far only submitted questions on legal issues. In addition, the Hungarian Competition Authority's ability to take appropriate evidence is not questioned in general by administrative courts, compared to other administrative authorities' capabilities.

There are many more competition cases concerning regulated or state-controlled markets. Requests for preliminary rulings in relation to electronic communication also encompass cases regarding the principles of the freedom to provide services and the free movement of goods. In the E.ON case, E.ON Földgáz, the holder of a gas transmission authorisation, lodged several requests for long-term capacity allocation at the entry point of the gas interconnector between Hungary and Austria with the Hungarian manager of the gas transmission network. Given that those requests clearly exceeded the capacity available at that entry point, the network manager requested the regulatory authority to inform him what position had been adopted on those requests. Following the network manager's request, the regulatory authority adopted a decision that amended the previous decision approving the network code. It thus redefined the rules of the network code governing the allocation of capacity for a term longer than one gas year. E.ON brought an action before the national administrative court for the annulment of the decision concerning capacity allocation mechanisms relating to the gas year 2010/2011, but its action was dismissed. The regional court also dismissed the appeal brought by E.ON, on the grounds that the company did not have locus standi in the judicial review of an administrative decision concerning the network code. E.ON had failed to show that it had a relevant direct interest in relation to the contested provisions of the decision, insofar as it had not concluded a contract with the network manager and the decision referred only to that. Under Hungarian law, a party to an administrative procedure only has locus standi to bring an action against an administrative decision only that action is directed against a provision of the decision that directly affects its rights. It raises the question therefore whether the interest on which E.ON relies, which it describes as an economic interest, can constitute a direct interest capable of conferring locus standi on that applicant in the context of a legal action against a regulatory decision in the sphere of energy. According to the ECJ's ruling, the relevant EU law must be interpreted as precluding national legislation that, in circumstances such as those at issue in the main proceedings, does not make it possible to confer on an operator, such as E.ON, locus standi to bring an action against the decision of the regulatory authority on the gas network code. The ECJ has broken down the principle of Hungarian administrative law, which says that competitors, market participants do not have locus standi in general to bring an action against an administrative decision with reference only to an

- 147/148 -

economic interest. This also illustrates that the efficiency of administrative disputes concerning administrative acts of sector-specific national regulatory bodies could still be improved. In relation to the gambling industry, Hungarian administrative courts submitted three requests for preliminary rulings concerning market regulation and barriers to market entry contrary to EU law. These cases can be explicitly linked to the modification of the regulatory system introduced after 2010.

Out of the ten references concerning state aid, nine are directly linked to agricultural subsidies and cover different interpretations of the directly applicable EU regulation. The relatively high number of requests for preliminary rulings is entirely natural, considering that both the substantive and procedural rules of this field are defined by EU law and therefore Hungarian administrative courts apply EU law directly in every case. More than half of the cases (four) ended in 2009-2010, which shows that the novelty of this field of law induced a higher number of requests. Subsequently, in period II, there were only three cases between 2010 and 2017 in which the ECJ ruled substantively, and another request was manifestly inadmissible. Compared to this data, there were surprisingly many references (three) in 2018, two of which are currently pending. In all these cases, the question was whether the applicable national law was compatible with EU law, while in the past cases the interpretation of EU law was at issue. In the SD case (C-490/18) one of the referred questions is whether the EU Regulation can be interpreted as permitting the adoption of a national law under which a de minimis aid payment is subject to a requirement that is not compatible with EU law. However, the main point of the questions is still the interpretation of EU law. In the UTEP 2006 SRL case (C-600/18) the referring court asked whether Article 92 TFEU should be interpreted as precluding the interpretation of the national law on small and medium-sized enterprises[46]) and the practice of the authorities, according to which Article 12/A of the KKV Law cannot be applied to small and medium-sized enterprises (legal entities) that are not registered in Hungary but in another Member State. As such, this case is about a discriminatory support. The third request, in the Farmland case (C-489/18) was declared manifestly inadmissible in 2019, because of the failure of the national court to explain the relevance of the reference in the case.

Classic competition law-related unlawful state-aid cases have already appeared in Hungarian case-law, but for the moment these requests for preliminary ruling are submitted by civil courts (C-672/13). It should be borne in mind that there is an overlap between unlawful state aid and tax matters. For example, in the Tesco Global case (C-323/18) the referring court wanted to know whether Articles 107 TFEU and 108(3) TFEU must be interpreted as meaning that their effects extend to a tax measure that is intrinsically linked to a tax exemption (constituting State aid) financed by means of the tax receipts generated by the tax measure. The legislature has achieved the amount of budgetary revenue forecast, which was fixed before the introduction of the special tax on retail trade (based on the

- 148/149 -

turnover of market operators), through the application of a progressive tax rate based on turnover and not through the introduction of a standard tax rate, meaning that the legislation deliberately seeks to grant tax exemption to some market operators. Tax law cases may have competition law aspects as well. It follows from the above observations that the conflicts between national and EU law in period II cannot be linked explicitly to the political changes in 2010, even if legal problems arose from the legislations of that decade.

4. Asylum and Immigration Policy

In asylum cases, five judgments have been delivered and three proceedings are pending. One judgment has been delivered on immigration matters and one is pending. three of these references for preliminary ruling proceedings were submitted between 2009 and 2011, and seven (!) after 2015. These numbers show that the press and media campaign of the Hungarian government between 2015 and 2018, which started with the refugee crisis in 2015, was accompanied by changes in the law, the interpretation of which necessitated the intervention of the ECJ in order to reconcile them with EU law. Moreover, the ECJ clearly refused to accept the deprivation of the substance of asylum-seekers' right to judicial remedy. In case C-473/16, the ECJ ruled that Article 4 of Directive 2011/95/EC[47] must be interpreted as meaning that it does not preclude the authority responsible for examining applications for international protection or the reviewing courts from ordering an expert's report for the assessment of the facts and circumstances relating to the declared sexual orientation of an applicant. The procedures for such a report must be consistent with the fundamental rights guaranteed by the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union. The authority and the courts or tribunals shall not base their decision solely on the conclusions of the expert's report and they are not bound by those conclusions when assessing the applicant's statements relating to his sexual orientation. This case points out that in where the assessment of certain facts is difficult (sexual orientation or age determination), because there are no clear expert methods, the - false - expectation was that courts should recognise the findings of the experts as compulsory.

In the C-369/17 Shajin Ahmed case, the Hungarian legislation was also contrary to EU law, because it deprived the national courts of all margin of appreciation. According to the ECJ, Article 17(1)(b) of Directive 2011/95/EU[48] must be interpreted as precluding legislation of a Member State, pursuant to which the applicant for subsidiary protection is deemed to have 'committed a serious crime' within the meaning of that provision, which may exclude

- 149/150 -

him from that protection, on the basis of the sole criterion of the penalty provided for a specific crime under the law of that Member State. The ECJ rules that it is for the authority or competent national court ruling on the application for subsidiary protection to assess the seriousness of the crime at issue, by carrying out a full investigation into all the circumstances of the individual case concerned.

It follows from the case-law of the ECJ that the Court accepted the Hungarian government's concept of 'return to a safe third country, judging it appropriate to solve the crisis of mass immigration, but it precluded the deprivation of effectiveness of judicial review. The ongoing references for preliminary ruling procedures are challenging increasingly severe legal norms and administrative practices restricting the right to an effective remedy. Hungarian administrative courts are seeking to know whether Article 47 of the Charter of Fundamental Rights and Article 31 of Directive 2013/32/EU can be interpreted, in the light of Articles 6 and 13 of the European Convention on Human Rights, as meaning that a judicial remedy is effective, even if the courts cannot amend decisions given in asylum procedures, only annul them and order a new procedure to be conducted. In the C-40/19 and C-60/19. cases, the ECJ must also examine whether the same legal provisions can be interpreted as allowing a Member State to lay down a single mandatory time limit of 60 days for judicial proceedings in asylum matters, irrespective of any individual circumstances and without regard to the particular features of the case or any potential difficulties in relation to evidence. One case concerns the right to family reunification (C-519/18) and the practice of the Hungarian Immigration Agency, which applies a much stricter interpretation than usual. However, this case is an example of increasingly rigid law enforcement and not legislation as such. Consequently, only four of these cases could be considered as a result of the political change in 2010 (the cases on the restraint of judicial review) and not a necessary consequence of the immigration crisis.

5. Environmental Protection

Three references were submitted in the area of environmental protection. The relatively small number of requests is due to the abundant ECJ case-law in this field. There was a unique case on dangerous animals and another regarding waste management, where there is a decade of Hungarian case-law regarding the notion of waste and transport of waste. It is worth describing the third case, Túrkevei Tejtermelő Kft., (C-129/16) in detail. It concerned one of the basic problems of Hungarian environmental regulation on liability for environmental damage. Under Article 102(1) of the Act on Environmental Protection, liability for environmental damage or for environmental hazard is - except where evidence to the contrary is provided - to be borne jointly and severally by those who own or are in possession (the user) of the land on which the environmental damage or hazard has occurred. Under Article 102(2), the owner is relieved of joint and several liability if he identifies the actual user of the land and unequivocally proves that he cannot be held responsible. In the administrative practice, the Hungarian environmental protection agency is usually unable to decide on who is responsible

- 150/151 -

for the damages. It imposes a fine on the person who appears to be the most solvent. This is usually the current owner and not the polluter. Another problem in the practice is that, if the administrative enforcement of the fine is unsuccessful, the authority will initiate new administrative procedures, for example against the former owner(s) of the land and keep taking new administrative decisions until it can establish someone's responsibility for the damages. It is very difficult to bring a successful action against these further administrative enforcements, because these owners did not participate in the previous decision procedures.

According to the ruling of the ECJ, the provisions of Directive 2004/35/EC[49] read in the light of Articles 191 and 193 TFEU must be interpreted as meaning that the national legislation is not precluded from identifying another category of persons who, in addition to those using the land on which unlawful pollution was produced, share joint liability for the environmental damage. More specifically, the owners of that land can be identified as liable, without it being necessary to establish a causal link between the conduct of the owners and the damage established, provided that such legislation complies with the general principles of EU law, all relevant provisions of the EU and FEU Treaties and of the acts of secondary law of the European Union. Article 16 of Directive 2004/35 and Article 193 TFEU must be interpreted as not precluding national legislation, pursuant to which the owners of land are not only held to be jointly liable for environmental damage alongside the persons using that land, but may also have fines imposed on them by the competent national authority. Such legislation must be appropriate for the purpose of contributing to the attainment of the objective of more stringent protection and the methods of determining the amount of the fine shall not go beyond what is necessary to attain that objective, this being a matter for the national court to establish.

Similarly to other fields of administrative law, in the field of environmental protection this kind of regulation is used to eliminate the inefficiencies of taking of evidence and the assessment of facts, as well as the complete lacks of an overall administrative responsibility theory, which is still in its infancy in Hungarian administrative law.[50]

6. Public Procurements

As a result of the Hungarian judicial review system, in the field of public procurement law, both civil and administrative courts submitted several requests for preliminary rulings before the Court. According to the Public Procurement Act (hereinafter referred to as the PPA) of 2015, the public procurement Arbitration Board (hereinafter referred to as the PAB) is empowered to

- 151/152 -

conduct proceedings initiated against any infringement of the legislative provisions applicable to public procurement or contract award procedures. This includes proceedings initiated against the rejection of a request for prequalification specified in a separate act of legislation and deletion from the prequalification list. The PAB may open a procedure upon a claim or ex officio. The claim can be submitted by a contracting authority, a tenderer (in the case of a joint tender, any of the tenderers), or a candidate (in the case of a joint request to participate, any of the candidates). In addition, any other interested person whose right or legitimate interest is being harmed or is at risk of being harmed by an activity or default that is in conflict with the PPA can initiate a procedure. No direct appeal can be lodged against the PAB's decisions. The courts can only review these decisions if so requested in the form of a statement of claim. Therefore, the PAB has national jurisdiction to proceed as a first instance public administration agency in disputes concerning contract award procedures, and its resolutions are subject to judicial review exercised by the administrative judiciary.

However, jurisdiction is reserved to the civil-law courts related to procurement procedures, concession award procedures and contracts concluded pursuant to procurement procedures, as well as work or service concessions and the amendment thereto or the performance thereof. With the exception of some cases, any civil law claim grounded on an infringement of legislation applicable to public procurement or to the procurement procedure shall be admissible if the infringement has been stated in a legally enforceable decision by the PAB, or in the course of the review of the decision of the PAB by the court. Although it seems that the different branches of the judicial review are sharply divided, there is a strong interaction between them in practice. However, the division can raise serious 'fair trial' issues, not to mention the effectiveness of the right to remedy in public procurement law. For example, in the Hochtief case (C-300/17) the Curia decided to refer the following question to the Court for a preliminary ruling: Does EU law preclude a procedural provision of a Member State that makes the possibility of asserting any civil right of action resulting from an infringement of a public procurement provision conditional on a final declaration by an arbitration committee [PAB] or a court (hearing an appeal against a decision of the PAB that the provision has been infringed)? The Court replied that the relevant EU law must be interpreted as not precluding a national procedural rule that makes the possibility of asserting a claim under civil law in the event of an infringement of the rules governing public procurement and the award of public contracts subject to the condition that the infringement be definitively established by an arbitration committee or, in the context of a judicial review of a decision of that arbitration committee, by a court. In the light of Article 47 of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union, EU law must be interpreted as meaning that, in the context of an action for damages, it does not preclude a national procedural rule that restricts the judicial review of arbitral decisions issued by an arbitration committee responsible at first instance for the review of decisions taken by contracting authorities in public procurement procedures to examine only the pleas raised before that committee.

It shows that, even in public procurement cases, Hungarian courts intend to implement not just the provisions of the relevant secondary sources of EU law, but also the principles

- 152/153 -

provided by the Charter. Requests for preliminary rulings made by the Hungarian administrative courts are related more to technical and professional issues (see among others C-138/08, C-218/11, C-470/13) rather than the political changes in 2010. Hungarian administrative courts are hugely active in submitting references in this field. The reason for this tendency is the frequent and self-perpetuating modifications of the public procurement legislation, at both national and EU level, which usually 'overwrites' the elaborated case-law and thus necessitates further references.

7. Other Cases

The other six cases concern the relation between free movement of goods and public health (C-108/09) and unfair and misleading commercial practices (C-388/13 - erroneous information provided by a telecommunication undertaking to one of its subscribers, which has resulted in additional costs for the latter). In the VIPA case, the court referred the question whether the relevant EU law must be interpreted as meaning that the national legislation is contrary to the mutual recognition of prescriptions and to the freedom to provide services, and therefore incompatible therewith. The legislation distinguishes between two categories of prescriptions and allows medicinal products to be dispensed to a doctor who exercises his healthcare activity in a State other than the Member State concerned in the case of only one of those categories. The Weltimmo case (C-230/14) concerned the protection of individuals with regard to the processing of personal data and the determination of the applicable law and the competent supervisory authority in Member States.

The Segro and Gunther joined cases (C-52/16; C-113/16) concerned the regulation of transactions in agricultural and forestry land. The ECJ stated that Article 63 TFEU must be interpreted as precluding national legislation under which rights of usufruct which have previously been created over agricultural land and the holders of which do not have the status of a close relation of the owner of that land are extinguished by operation of law and are, consequently, deleted from the property registers. The legal context of the case was that Hungarian legislation stated that any right of usufruct or right of use existing on 30 April 2014 and created for an indefinite period or for a fixed term expiring after 30 April 2014 by a contract between persons who had not been close members of the same family shall be extinguished by operation of law on 1 May 2014. The Hungarian legislator adopted these measures preventing the application of legal arrangements known, in everyday language, as 'pocket contracts', which was a way of evading the previous prohibitions and restrictions concerning the acquisition of ownership by foreign natural and legal persons. The Hungarian Constitutional Court declared that the Hungarian Fundamental Law had been infringed because the legislature did not adopt, as regards the rights of usufruct and rights of use, exceptional provisions permitting compensation, which compensation, even if it related to a valid contract, could not have been claimed in the context of a settlement between the parties to that contract. In the judgment, the Constitutional Court also called on the legislature to rectify that omission by 1 December 2015 at the latest. That period expired without any

- 153/154 -

measure being adopted for that purpose. According to the Segro and Günther case, this legal situation also represented a serious breach of EU law. The ECJ's ruling has been applied by the Hungarian administrative justice not only in cases clearly falling within the scope of EU law, but also in matters without foreign elements. For example, in a case where a Hungarian citizen living on a farm in an underdeveloped eastern region lost his right of usufruct by the operation of the law, after having received a right of exploitation from his former life companion because of his previous house extensions. If the Curia had not done so, the legal regulation would have had the opposite effect, and Hungarian citizens would have suffered severe negative discrimination.[51]

VI. Conclusions

This paper has proved that period I was a learning period for EU law in Hungary, while period II is the consolidation phase of the uniform and organic functioning of EU and national law. In period II the number of requests increased three- or fourfold, which fits into the regional trends, and there is no clear link to the political or public policy change in 2010. Based on content analysis, only nine of the administrative law references can be considered as related to political issues. Three taxation and gambling cases concerning sector-specific discrimination, four requests challenging legislation hindering effective judicial review in asylum cases, and two but joined cases regarding transactions in agricultural lands can be clearly placed among those cases that have resulted from the government change in 2010. This is around 10% of all administrative references (83), which is not a striking figure.

Two-thirds of the requests for preliminary ruling proceedings are referred by administrative courts in Hungary, and a significant part of civil cases are related to administrative disputes. Civil justice is an important element in the enforcement of EU law, in particular in consumer protection and competition law. It also plays a cardinal role as a final instrument in case administrative justice does not function properly for any reason. nevertheless, the administrative judiciary system is the main institution that serves as a transmitter between EU and national law. The number of Hungarian references is still higher than the regional average, which cannot be explained by objective factors, unless it is imputable to the networking of EU advisor judges, in particular in the fields of administrative law, where the network is able to reach the entire administrative judiciary, given the relatively smaller number of judges (100-200 judges). This statement is supported by the fact that the lower courts (where most judicial advisors work) are extremely active in referring and that the Supreme Court (now Curia) has reacted to this trend with a much longer delay (here more than two-thirds of the requests are/can be linked to advisor judges). It is also clear that the operation of Hungarian public administration is inadequate compared to the EU average. This is especially due to

- 154/155 -

shortcomings and inconsistencies in the rules and theory of administrative law liability, which is closely related to the inadequacy of taking evidence. The disproportionate number of VAT cases and the issue of the proportionality of fines, along with the increasingly overwhelming number of asylum cases related to the limitation of the scope of judicial review, prove these points

As we have demonstrated, the efficiency of the application and implementation of EU law can be analysed over a 7-year period at least. Since the accession of Hungary to the European Union, the trends in the initiations of references for preliminary ruling procedures are clear, and they show a manifest upward trend. These trends may have several reasons. However, we state that the independence of administrative judiciary is one of the key indicators for the efficient operation of this transmission point, i.e. the preliminary ruling mechanism between national and EU law. If there is an independent administrative judiciary the number of requests will continue to increase. In addition there are several tendencies in the European Union that will increase the number of requests in the coming years. For example in the case C-416/17, the Court declared that, since the Conseil d'État (Council of State, France) failed to make a reference to the ECJ, in accordance with the procedure provided for in the third paragraph of Article 267 TFEU, the French Republic failed to fulfil its obligations under the third paragraph of Article 267 TFEU. A reference should have been made to the Court, because in this case (on the reimbursement for the advance payment of the tax unduly paid), the provisions of EU law based on the judgments of 10 December 2012, Rhodia, and of 10 December 2012, Accor, were not so obvious as to leave no scope for doubt. This case law is expected to give incentives to the national (supreme) courts to bring more references before the Court.

If the number of requests will not increase in the next seven-year period, but stagnate or decrease, it will clearly point out that the most important transmission point between EU law and national law has broken down. It is also conceivable that the lower courts become more active. What is going to happen? We will know seven years from now - not sooner than in 2026. ■

NOTES

[1] For example, the search in the text 'Hungary' '(Hungary),' and '[Hungary]' can all cause discrepancies, not to mention that the name of the country changed from the 'Republic of Hungary' to 'Hungary' during the period examined.

[2] The most important task of the ELAN (European Law Advisors' Network) judicial advisors is to advise Hungarian judges on their references regarding the interpretation and application of European Union law and the European Convention on Human Rights. In addition, they share their EU law expertise through a number of other means as well: they give lectures at training sessions for judges, publish working papers and prepare templates. Judicial advisors elaborate, according to certain criteria, explanatory notes - to be published on the blog site of ELAN's webpage - on the judgements of the Luxembourg-based European Court of Justice (ECJ) and the Strasbourg-based European Court of Human Rights (ECHR), as well as on those judgements of the Curia of Hungary that have EU law relevance. They perform their functions within their respective fields of law.

[3] Kazai Viktor Zoltán, 'A joggyakorlat értelmezésének nehézségei illiberalizmus idején - érvek a narratív módszer mellett' (2018) 2-3 Fundamentum 51-58.

[4] 30 of 158 references are still pending (22 were made in 2018).

[5] Eurostat 2018.

[6] Kornai János, 'Még egyszer a rendszerparadigmáról, Tisztázás és kiegészítések a posztszocialista régió tapasztalatai fényében' (2016) October Közgazdasági Szemle 1074-1119; Fareed Zakaria, 'The Rise of Illiberal Democracy' (1997) 76 (6) Foreign Affairs 22-43, 27; See also Unger Anna, 'A választás, mint rendszerkarakterisztikus intézmény' (2018) 23 Fundamentum 5-16.

[7] In Slovakia the accession negotiations were actually launched in 1999, Meciar's premiership, which resulted in a 5-6 year delay in preparation for EU Membership.

[8] Somssich Réka, 'Előzetes döntéshozatali eljárások - nemzetközi kitekintés a 2004-ben csatlakozott országok vonatkozásában' in Osztovits András (ed), A magyar bírósági gyakorlat az előzetes döntéshozatali eljárások kezdeményezésének tükrében 2004-2014. (HVG-ORAC 2014, Budapest) 32-33.

[9] <https://kuria-birosag.hu/sites/default/files/joggyak/az_europai_unio_joganak_alkalmazasa.pdf> accessed on 18 September 2019.

[10] Morten Broberg, Niels Fenger, 'Variations in Member States Preliminary References to the Court of Justice - Are Structural Factors (Part of) the Explanation?' [2013] European Law Journal.

[11] Várnay Ernő, 'Előzetes döntéshozatali eljárás - nemzetközi kitekintés' in (n 8) 51-67.

[12] Várnay (n 11) 52.

[13] CEPEJ Efficency of judicial system.

[14] Report from the Commission SWD(2018)377.

[15] Várnay (n 11) 55-58.

[16] We have taken into account the joined cases separately.

[17] C-56/13, Érsekcsanádi Mezőgazdasági Zrt. v Bács-Kiskun Megyei Kormányhivatal, ECLI:EU:C:2014:352.

[18] C-492/16, Incyte Corporation v Szellemi Tulajdon Nemzeti Hivatala, ECLI:EU:C:2017:995.

[19] C-287/14, Eurospeed Ltd v Szegedi Törvényszék, ECLI:EU:C:2016:420.

[20] Varga Zsófia, Az EU jog alkalmazása - Kézikönyv gyakorló jogászoknak (Wolters Kluwer 2017, Budapest) 173-176.

[21] Győri Ítélőtábla (Hungary) lodged on 10 July 2018 - Tibor-Trans Fuvarozó és Kereskedelmi Kft. v DAF TRUCKS NV. and JUDGMENT OF THE COURT (Sixth Chamber) 19 March 2015 C-672/13, OTP Bank Nyrt. vs Magyar Állam, Magyar Államkincstár, ECLI:EU:C:2015:185.

[22] Data of Budapest Metropolitan Court and Administrative and Labour Court of Budapest (2017), Annual Statistical Yearbook of Hungarian Judiciary, 2017 published by NOJ, <https://birosag.hu/statisztikai-evkonyvek> accessed on 05 June 2019 The proportion of initiated administrative cases in Budapest is 1 to 3 (cca 30%) compared to countryside courts, although almost 50% of requests of preliminary references stemmed from Budapest (31 from 68). It shows, too, that cca 40% of administrative cases have an obvious connection with EU law. We estimated - in respect of the proportation of requests for preliminary references, and considering the above mentioned data -that 50% of cases are linked to EU law.

[23] C-283/06, KÖGÁZ Rt. és társai v Zala Megyei Közigazgatási Hivatal Vezetője and C-312/06, OTP Garancia Biztosító Rt. v Vas Megyei Közigazgatási Hivatal, ECLI:EU:C:2007:598.

[24] Shalini Randeria 'Példabeszéd a Neemfáról, a jog transznacionalizációja ás a civil társadalmi szereplők szerep' [2003] Eszmélet 60, <http://www.eszmelet.hu/shalini_randeria-peldabeszed-a-neemfarol-a-jog-transznacio/> accessed on 18 April 2019.

[25] 8/2011. (II. 18.) AB határozat.

[26] Blutman László, Az Európai Unió Joga a gyakorlatban (HVG-ORAC 2013, Budapest) 531.