Dr. Benedek Kristóf Fekete[1]: The Relationship Between Judicial Service as Employment and Judicial Independence* (JURA, 2023/2., 5-37. o.)

I. Introduction

Judicial service is one of the main features of the judiciary, which also affects the entire judicial organisation of a state. Given the role of the judiciary in a constitutional democracy, the requirement of independence must prevail in all circumstances, and it is therefore justified and exciting to explore how the Hungarian regulatory solution for judicial service as an employment relationship is developing and how it is related to judicial independence. The academic analysis, therefore, aims at explaining this defining feature of the judiciary, remaining within the field of social sciences, more specifically, law and political sciences.

The reason for the choice of the topic is the problem that can be described by the network of rights and obligations of employers and employees, i.e. how the role of the "boss" develop within the judicial organisation, what regulatory solutions channel employers' exercise of individual rights so that they do not violate the constitutional requirement of independence, but serve an efficient adjudication.

The main aim of this paper is to outline the trichotomous (organisational, personal and professional) system of judicial independence, and to describe the substantive content (similarities and differences) and limitations of judicial service and employment.[1] As outlined above, this paper therefore examines the employment aspect of judicial service, bearing in mind the requirement of judicial independence. It is essential that judicial independence as a requirement both protects the manifestation of judicial work and judicial activity, and at the same time imposes limits on it. Consequently, it is essential to systematise the factors that have a positive or negative impact on judges and courts, based on an appropriate conceptual basis.

- 5/6 -

The methodology of the paper is essentially qualitative: the analysis is mainly based on the interpretation and analysis of the relevant legal documents using known interpretative techniques, and on the identification of contexts and trends.

II. The trichotomous system of judicial independence and the requirement of independence

An independent judiciary is one of the foundations of the rule of law,[2] and judicial independence, in the consistent practice of the Constitutional Court of Hungary (hereinafter: the Constitutional Court), is the "most important" guarantee of judicial independence.[3] As the most important guarantee, its content presents a very complex picture, with many meanings stemming from its many components. Consequently, and in line with the widely accepted position in the literature[4], the independence in question must have at least three components, organisational, personal and professional (otherwise: internal) independence.[5] They are indivisible in their integrity, so the absence of any component can result in a deficiency of justice (judicial procedure).

1. Organisational independence

Organisational independence, as a basic condition for an independent judiciary, refers essentially to the independence of the judiciary from other branches of power, such as the executive, the legislature and political parties. Organisational independence resulting from the separation of powers therefore requires the existence of guarantees and, more narrowly, procedural guarantees that allow this to be achieved. The key is an appropriate division of powers through constitutional arrangements.[6] Its importance lies in the fact that the judicial system, as part of public law, cannot exclude itself from its necessary interfaces. As part of public authority, it also implies a degree of cooperation with other institutions such as the National Assembly, the President of the Republic and the Government, i.e. with certain bodies of the legislative and executive branches.

With proper regulation, the external and internal autonomy of the judicial organisation should ultimately emerge. For one thing, from an external point of view, the court cannot serve another branch of power, which implies the framework of an autonomous judicial organisation.[7] For another thing, at the internal and organisational level, the decision taken by the judge cannot be defined in any form, either in terms of content or form, since it must be the result of the intellectual work of the judge, who must be free from any influence.

In the light of the above, the Constitutional Court uses the independence enshrined in the Fundamental Law in a double sense: on the one hand, as the independence of the judicial organisation as a whole, and on the other hand, as the independence of the judge hearing a case.

- 6/7 -

2. Personal independence

The judge himself or herself is an essential element of due process. The safeguards for the due process of a judge can in fact be grouped around the creation and termination of the judge's term,[8] which is complemented by the rules on immunity and conflicts of interest.

Historically, two forms of professional judgeship have emerged, namely appointment and election. However, the form itself (appointment or election) may become theoretically irrelevant with appropriate substantive requirements, since the lessons of historical development also prove that "[the] creation of a mandate serves the personal independence of the judge if its procedure ensures the selection of persons suitable to perform the judicial function, or if its form of creation does not create a direct dependence between the judge and the creating body."[9]

Without going into the very detailed rules, it can be stated that in Hungary, judges are selected on the basis of the system for appointing judges by competitive calls for applications, in a multiple-stage process (taking into account objective and subjective criteria)[10], and, if the post is awarded, the appointment is made by the President of the Republic.[11] Judges may be removed from office only for reasons specified in a cardinal law (e.g. incompetence, conflict of interest, unworthiness, etc.) and in the framework of a procedure.[12] In this context, a further safeguard is the institution of immovability (prohibition of transfer), according to which "[a] judge may not be instructed, dismissed against his or her will or removed from his or her position." The reasoning of the Constitutional Court also emphasises that "personal independence is also a fundamental right guaranteed to the subjects of the proceedings; the immovability of judges is also a guarantee of the right to an independent and impartial tribunal. Immovability from office is therefore "'an element not only of the status of a judge but also of judicial independence'."[13]

To ensure the independence of the proceedings, judges enjoy the same immunity as members of Parliament.[14] This covers two aspects: for one thing, we have the immunity (of a general nature) linked to the person, and, for another thing, we have the immunity linked to the specific acts of a person.[15] In the words of the Constitutional Court, "[t]he right of immunity of judges is also linked to their office subject to public law and the duties they perform. It is not a personal privilege, but a functional legal protection attached to the status of a public office, which protects the judiciary as the third branch of power against undue or unjustified influence and harassment by providing personal protection to support the smooth functioning of the judiciary."[16] However, if there are reasonable grounds for suspecting the judge of having committed a criminal offence, the proceedings cannot be continued without waiving immunity. The suspension of immunity shall be decided by the President of the Republic on the proposal of the President of the

- 7/8 -

National Office for the Judiciary (hereinafter: NOJ).[17]

Personal independence also necessarily includes the so-called conflict of interest rules, according to which, in order to ensure judicial independence, judges must refrain from certain conduct and activities. Conflicts of interest rules can concern political, official, occupational, economic and procedural conflicts of interest (prohibition of co-employment[18]).[19]

3. Professional independence

According to the practice of the Constitutional Court, in addition to personal independence, another element, the so-called professional independence, is also linked to the person of the judge, the person holding the judicial office. This kind of independence can be identified with the free interpretation of the law by the judge in the case before him or her, which in turn may be linked to the requirement of independence not only in a professional sense, but also in an organisational sense, since other branches of power, typically the executive, may seek to "control" the adjudication process in addition to the parties.[20] The Constitutional Court points out as a matter of principle that "[p]rofessional independence guarantees the judge's freedom from influence in the course of his or her judicial activity, while personal independence is the independent status in public law, consisting of several components, which a judge enjoys during the term of his or her service."[21] It is a general problem that judges can be subject to a wide range of influences and pressures in the course of their judicial activity. For one thing, there are the influences, mostly not even conscious, that result from social (origin, upbringing, etc.) and workplace (socialisation, type of relationships, etc.) contexts. For another thing, specific influences to which the judge is subject by virtue of his or her position.[22] It can be described as the freedom that is necessary for the judge to be able or dare to reject the external influence [e.g. the expectations of society (public opinion)] that is very often directed towards him or her. In this context, "[t]here seems to be a consensus in the literature that internal pressure and the resulting bias is less of a problem than external [influence]."[23]

It is clear that the independence of the judiciary depends crucially on the judges' capacity for individual (internal) independence, which can be identified as a kind of complex moral courage.[24] The judge's dependence on his or her own conscience can therefore be described as the "most embarrassing" dependence: "[a] judge finds it much more difficult to overcome the doubts of his or her own conscience than to faithfully obey the orders of his boss."[25]

A "fair" remuneration is part of ensuring the independence of the judiciary. Financial recognition plays a central role in the judge's high-quality and uninfluenced judgement.[26] Such independence can be divided into two parts. For one thing, the remuneration of judges must meet the needs of the profession, and, in keeping with their status and prestige, must provide financial security and respect. For anoth-

- 8/9 -

er thing, an objective and predictable set of requirements must be established which also contributes to strengthening independence. The requirement for adequate remuneration and how to stop it can be approached from two angles. For one thing, the remuneration of judges can be compared to the average salary in the country, and for another, a comparison should be made to take into account the competitiveness of judicial remuneration in relation to the competitive sector.[27]

III. Conflict of interest

Conflict of interest is a cardinal issue for judicial services as well. The Fundamental Law, in the light of Hungarian historical particularities, is limited to the definition of political conflicts of interest. Thus, according to the third sentence of Paragraph (1) of Article 26 of the Fundamental Law, "[judges] may not be members of political parties or engage in political activity." The Judges' Status Act repeats this wording and lists further detailed rules in Chapter 21 on what work is and is not permitted in the context of judicial activity. Taking the positive approach, it is more practical to discuss what work a judge may do beyond his or her judicial office and under what conditions, since work in other areas is excluded ex lege.

In addition to his or her duties as a judge, a judge may only engage in gainful employment as an academic, teacher, coach, referee, umpire, artist, copyright holder, proofreader, editor, technical creator or foster parent. This, however, must not, of course, compromise judicial independence or impartiality or give the appearance of doing so, nor hinder the performance of his or her duties.[28] In view of the latter constraints, these activities are generally worthy of the status of judge, and the theoretical risk of creating a relationship of instruction or dependence that would be contrary to the essence of the judicial profession is low.[29]

Therefore, in order to ensure that the judiciary is able to adjudicate in accordance with the requirements of the rule of law, the prior consent of the person exercising employer powers is required for the establishment of other employment relationships affecting all or part of the working time of the judge in the context of his or her service. In this context, it is the discretion of the person exercising employer powers whether or not to allow the above. This is a strong power, which means that no legal action can be brought for refusal to give consent.[30] In contrast, the situation is different when a judge wishes to establish other employment relationships without affecting his or her working time. In such a case, only a prior notification must be made to the person exercising employer powers, and he or she may only prohibit the other legal relationship if it would otherwise resuit in a conflict of interest under the provisions of the Judges' Status Act.[31]

The Judges' Status Act also establishes a special employment arrangement when it states that judges assigned to the Hungarian National Office of the Judiciary, the Curia and, with the exception of the Prosecution Office, to the

- 9/10 -

body concerned may only hold a position of head of division, deputy head of division or head of department.[32] Positions that would otherwise constitute a conflict of interest are therefore exempted by law from the above.

Here we can also mention the prohibition of co-employment, which is a special rule that excludes the possibility of a relative of the head of a court or court department being a judge.[33]

IV. Eligibility rules

In order to ensure an adequate standard of judicial functioning, judges must meet certain eligibility criteria laid down by law. These aspects can be divided into two broad categories: on the one hand, the broad dimension of health, covering health, physical and psychological aspects, and on the other hand, the relatively narrow dimension of professional competence, assessing the quality of the activities of a judge. These can be complemented by a further special category of eligibility rooted in disciplinary rules, the personal dimension.

1. Health dimension

One of the big "watersheds" for one's suitability for a career as a judge is the so-called "career aptitude test," which is a comprehensive health, physical and psychological fitness test. This test reveals the psychological and health reasons that preclude or significantly influence the performance of judicial work, as well as the judge's personality traits of intelligence and character. As a result of the test, it must be established whether the person is, as expected, suitable to work as a judge.[34]

The career aptitude test or review is carried out by a panel of forensic experts designated by the Minister of Justice, with the agreement of the President of the NOJ.[35] The detailed rules are set out in Decree No. 6/2020 (25 May) of the Minister of Justice on the career aptitude test for judges, Annex 1 of which divides the tests into three main parts: general medical, (neuro-)psy-chiatric and psychological. These are supplemented by the 20 competency measurements specified in Annex 5 of the Judges' Status Act, namely (i) decision-making ability; (ii) cooperation; (iii) analytical thinking; (iv) foresight; (v) discipline; (vi) responsibility; (vii) decisiveness; (viii) demandingness; (ix) integrity; (x) communication; (xi) conflict management; (xii) creativity; (xiii) confidence, decisiveness; (xiv) autonomy; (xv) problem and situation analysis; (xvi) problem solving; (xvii) application of professional knowledge; (xviii) organisation and planning; (xix) oral and written communication skills; and (xx) objectivity. This review must be sent to the applicant and is valid for three years as a general rule and can be used in case of a new application.[36]

In duly justified cases, the President of the Court may subsequently order a medical examination if the judge is permanently unable to carry out his or her duties for health reasons (e.g. the judge is physically only able to move around in a wheelchair and is becoming mentally deterioration.). If, however, a judge who has been requested in

- 10/11 -

writing to resign does not do so within 30 days, the judge's health must be examined as described above and the action taken depending on the result.[37] This can have the following outcomes:

(a) If the test does not take place because the judge concerned does not attend the medical examination ordered by the employer [the person exercising employer's powers] through his or her own fault, he or she shall be deemed to have acquiesced in the application of the legal consequences of inaptitude.[38]

(b) The test establishes that the person examined is fit to perform the duties of a judge, in which case he or she may perform those duties in the position held.

(c) The test concludes that the judge is currently or permanently unfit to perform the duties of judge. In the first case, the health problem is temporary and, once it has passed, the possibility of reinstating the judge is in principle open. In the latter case, however, the incapacity is of a permanent nature, so that the occupation of the status of judge by the person concerned, i.e. the judicial service, is terminated permanently.[39] This may be because a physical impairment renders the judge physically unfit for the job (e.g. certain chronic illnesses) or because he or she is found mentally fit but not fit to do the job (e.g. a mental disorder affecting his or her aptitude for the job).[40] It is important that the judge concerned should in any case be given full access to the professional opinion on ineptitude.[41]

If medical incapacity is established, the judge is entitled to a quasi severance payment, which is a fixed multiple of his or her salary, depending on the length of service. If his or her length of service does not exceed 10 years, he or she is entitled to 9 months' salary, and if he or she has served for more than 10 years, he or she is entitled to 13 months' salary. However, if a judge who has been dismissed for medical reasons is granted a pension in his or her own right, he is not entitled to the benefit just mentioned.[42]

According to the annual reports of the President of the NOJ, medical incapacity was found for 6 judges between 2014 and 2021.

2. Professional dimension

Looking at the professional dimension, the first impression is that it is a rather neglected issue, while more emphasis should be put on how to filter out incompetent judges, as there may still be many of them today.[43] The question is crucial because it is not essentially about disciplinary cases, but about cases where the judge does not commit a disciplinary offence, but his or her judicial practice is of a rather poor quality. This is also significant because it is also related to independence: the review of the judge's work must be such that it cannot be used to render the judge ineffective (e.g. he or she receives difficult cases, cannot finish on time, trial is delayed, etc.), but at the same time it must filter the judge's preparedness, judgement, etc., i.e. there must be some kind of aptitude filtering mechanism. Consequently, it is necessary in this context to examine the relationship be-

- 11/12 -

tween the review and the service.[44] It is practical to link the assessment of the professional competence dimension to two temporal aspects: the fixed-term[45] appointment on the one hand, and the indefinite[46] appointment on the other.

2.1 Judges appointed for a fixed term

If the appointment of a judge is, as a rule, for a fixed term of three years, it is easier to filter out judges who are considered unfit, as they are still at the "beginning" of their career, i.e. they are not allowed to enter the judicial organisation on a permanent basis.

According to the relevant rules of the Judges' Status Act[47], the president of the court shall obtain the declaration of the judge concerned 90 days before the last day of the fixed term of the judge's appointment, whether he or she requests to be appointed for an indefinite term. If the answer is in the affirmative, it is necessary to examine the judge's work throughout his or her term of office, but only if the actual term of office exceeded 18 months.

The investigation on which the review is based shall be ordered by the president of the court under Paragraph (1) of Section 70 of the Judges' Status Act, either ex officio or on the initiative of the head of the chamber with authority over the judge's place of work and area of specialisation or the head of the appellate chamber with authority over the judge's place of work and area of specialisation. It should be stressed that, in the case of a district court judge, the president of the district court may also initiate such an investigation. The examination shall be carried out by the head of the division with authority over the judge's place of work and area of specialisation or by the judge designated by him or her (hereinafter together: examiner) in accordance with the provisions of the Judges' Status Act.[48]

For the examination, the necessary cases are selected and for the review (i) the notes of the president of the chamber on the judge's cases during the period under examination; (ii) the judge's annual activity report; (iii) the summary opinions of the president of the chamber of appeal who reviewed the judge's cases, with the exception of Curia judges; (iv) documents containing administrative measures taken as a result of the judge's protracted litigation; (v) information concerning the judge's attendance at compulsory training courses; and (vi) other documents, opinions and information as the President of the NOJ may determine by regulation. The procedure for the selection of cases for the review and the detailed rules of the examination are laid down in the Regulations issued by the President of the NOJ, Instruction No. 8/2015 (12 December) of the President of the NOJ on the Regulations on the review of the work of judges and the detailed criteria of the examination. Accordingly, the professional competence of the judge under investigation is assessed in sufficient detail, by examining in depth, in addition to the competences listed in Annex 5 of the Judges' Status Act, (i) the files of his or her (non-appealably) completed cases (both litigation and non-litigation, if heard in mixed cases); (ii) his or her other cases

- 12/13 -

and files (where there has been an objection on the grounds of delay or bias or where a well-founded complaint has been lodged); (iii) his or her procedural actions (conduct of proceedings, conduct of hearings, presentation at appeal or review hearings); (iv) elements of timeliness (e.g. case flow data, case completion rates, etc.).[49] The aim of the investigation is therefore to identify the judge's substantive, procedural and administrative law application and trial management practices on the basis of cases that have been non-appealably concluded.

Following this, the person exercising employer powers, who ordered the investigation, makes an overall review of the judge's work, taking into account the report received and the review proposal, on the basis of the investigation material and the documents and opinions obtained.[50] The review, which must include only factually founded judgments, must include an opinion on the judge's suitability for appointment for an indefinite term. In the case of a judge appointed for an indefinite term, the review scale will be (i) excellent, suitable for a higher judicial position; (ii) excellent; (iii) fit and (iv) unfit.

In addition to the president or the vice-president of the court ordering the investigation, the judge under review and the examiner, the head of the division of the court with authority over the judge under examination and the president of the court where the judge is serving are present at the presentation of the review. The judge under examination may make oral and written comments at the latest at the presentation, which may still have a significant influence on the outcome of the review, as the president of the court ordering the review will communicate the review taking into account what was said at the presentation.

As a result of the above, there are two possible outcomes of the examination and review. On the one hand, if the judge is found suitable for appointment for an indefinite term, the proposal for appointment is submitted to the President of the Republic within 30 days before the last day of the third year, without a call for applications. On the other hand, if the judge has not applied for appointment as a judge for an indefinite term or if, as a result of the examination, he or she is found to be unfit for appointment, the judge's employment shall ipso iure cease on the last day of the third year following the date of appointment.[51]

However, this also requires the professional incompetency procedure provided for in Paragraph (1) of Section 81 of the Act. Therefore, in the event of a declaration of unfitness, the person exercising employer powers shall, at the same time as the review is communicated, call upon the judge to resign from his or her position as a judge within 30 days.[52] If the judge concerned has not complied with this request, the president of the court will immediately inform the court of first instance hearing service-related cases. In such cases, the court hearing service-related cases conducts an inaptitude procedure based on the rules of disciplinary procedure, with the appropriate derogations of course, and decides on the

- 13/14 -

judge's aptitude in an extraordinary procedure.[53]

In terms of remedies, the grounds relied on by the evaluated judge are of particular importance.[54] If a judge is found to be unfit in this context, he or she may challenge the decision taken in this respect only in accordance with the rules applicable to disciplinary decisions, i.e. under Sections 81 and 84 of the Judges' Status Act. An appeal against the result of the review itself is only possible if the qualification is "excellent, suitable for a higher judicial position," "excellent" or "fit," i.e. according to Section 79 of the Judges' Status Act.

2.2 Judges appointed for an indefinite term

The professional competence of judges is review through ordinary and extraordinary evaluations. The former, as a general rule, takes place before the appointment of a judge for a fixed term and every eight years thereafter, while the latter can take place for various reasons. It is important to note that, in the case of a judge appointed for a fixed term, the examination is the same as described above, with the difference that, as time goes on, the reviews made previously are taken into account.

According to Section 69 of the Judges' Status Act, the activity of a judge appointed for an indefinite term as well as a judge appointed for a fixed term shall be reviewed out of turn if for any reason it appears that (i) the judge is unable to perform his or her duties for professional reasons (e.g. the drafting of the decision does not include substantive legal reasoning, does not follow the law in force, does not follow the guidance of higher courts, etc.); (ii) the judge requests it [e.g. a judge asks for an extraordinary review because he/she needs to obtain a fresh, excellent rating (suitable for a higher judicial position) for an application] and (iii) a case before him or her is pending for more than two years without any change in the person of the judge who is hearing the case and it is established on the basis of an examination of the case file that the judge is at fault for acting in a way that would delay the completion of the case within a reasonable time (e.g. not taking any action to expedite the expert's appearance if the expert does not appear, not taking any action to replace original documents not returned by the expert, not submitting the appeal to the Higher Court, etc.).[55] Given that judges appointed for a fixed term are under greater "professional control," it is more appropriate to discuss this issue with judges appointed for an indefinite term.

The Judges' Status Act treats as an exception and exempts heads falling within the power of appointment of the President of the NOJ, as well as fixed-term heads falling within the power of appointment of the President of the Curia and the Deputy President of the Curia, and the Judge Deputy President of the NOJ during their term of appointment, judges assigned to the NOJ, the body concerned and the Curia during their term of appointment from regular judicial review.[56] Due to their special status, these people cannot be subject

- 14/15 -

to regular reviews, but the Judges' Status Act does not exclude the possibility of an extraordinary review. In other words, if the listed heads fall under Section 69 of the Judges' Status Act, they may also be examined. There is also a special provision that the activity of the judge assigned to the Curia is evaluated by the President of the Curia, while the activity of the judge assigned to the NOJ is reviewed by the President of the NOJ in accordance with the rules of the Act on the service of justice staff.[57] The work of a judge assigned to any of the bodies concerned are assessed by the head of the body to which he or she is assigned in accordance with the rules applicable to staff serving in the body to which he or she is assigned.[58] This distinction is necessary because these people do not carry out traditional judicial activities, and therefore the Judges' Status Act places their review in a different framework.

2.3 Review of professionalism in the annual reports of the President of the NOJ[59]

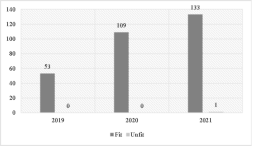

Based on the 2012-2021 reports of the NOJ, all but six of the judges appointed for a fixed term were found to be fit during the preparation of the review. Based on the available data, the following graph is only an illustration of the review of judges appointed for a fixed term.

Figure 1: Review of judges appointed for a fixed term based on the annual reports of the President of the NOJ (own ed.)

It is interesting to note that between 2014 and 2021, 21 reviews were referred to the relevant service-related courts. This includes those who have appealed on grounds of inaptitude and those who have appealed against a review of their work as a judge. The outcome of the proceedings is mixed, with several cases where the review was indeed more negative than it should have been, several cases where a new examination was ordered and, as known from judicial and constitutional practice, cases where it was maintained that the judge was not fit to be a judge. A related point is that between 2012 and 2021, less than 1% of the judges examined were found to be unfit, including both fixed-term and permanent judges.

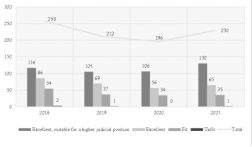

Figure 2: Review of judges appointed for an indefinite term based on the annual reports of the President of the NOJ (own ed.)

- 15/16 -

The annual reports of the President of the NOJ also show that since 2012, there have been fewer than six cases of judges appointed for an indefinite term being found unfit, which either means that the vast majority of judges are professionally fit or that the system is not always able to screen out judges who are already "in the system." I would add that if it were the latter, there would have to be significantly more professional incompetency proceedings.

3. Personal dimension

In addition to the cases discussed above, there are also cases where, despite the screening mechanism described above, the judge is unfit for judicial office or profession because of his or her person or conduct. This type of incompetence typically arises later and can only be "remedied" through disciplinary proceedings.

Pursuant to Paragraph (1) of Section 106 of the Judges' Status Act, mutatis mutandis, the president of the court or the person exercising the power of appointment shall initiate proceedings for disciplinary offences.[60] There are two categories of this misdemeanour, namely where a judge (i) breaches the obligations arising from his or her service or (ii) by his or her conduct or behaviour, damages or endangers the prestige of the judicial profession.[61] The former are basically cases laid down in cardinal laws (e.g. procedural or administrative delays[62]), the latter, on the other hand, cover an extremely wide range of situations which, due to their diversity, it is not practical to define in an exhaustive manner, but the Code of Ethics for Judges[63], the previous decisions of the Ethics Council[64] and the practice of the Hungarian courts hearing service-related cases and the findings of the report "Judicial Ethics - Principles, Values and Qualities" of the European Network of Councils for the Judiciary (hereinafter: ENCJ)[65], the Bangalore Principles, the ENCJ London Declaration or the ECtHR Code of Ethics can serve as a benchmark for the enforcement of disciplinary law. It is, of course, a category beyond this, but it can include cases where a judge becomes unfit because of the commission of a criminal offence.

Personal incompetence is not rooted in medical or cognitive capacity, so the judge's judicial activities cannot be the subject of scrutiny in the enforcement of disciplinary law (but if there is a criminal offence, there may be elements that need to be reviewed, for example if the judge colludes with certain actors in the proceedings by using his or her position).

It goes without saying that the seriousness of each disciplinary offence may vary, but, taking into account the principle of gradualness, the judge may have to be removed from his or her post. This is a legitimate sanction under the Fundamental Law from the point of view of judicial independence, provided that it is not indirectly a "response" to the judicial activities of the judge concerned and that it is done in the manner provided for in the cardinal laws.[66]

- 16/17 -

V. The essential manifestation of the exercise of employer powers: the right to give instructions

The general characteristic of the employment relationship is that it is subordinate: by virtue of its position, the person exercising the employer's rights determines, specifies and directs the employee's performance throughout the duration of the employment relationship by unilateral acts. In such a context, this aspect of the employer powers is usually referred to as the right to direct, to specify, or otherwise to instruct.[67]

This type of dependency is, however, incomprehensible in the context of judicial service. The right to instruct is not contractual, but derives from public law, from a state "intervener," i.e. the "unlimited" nature of this right is excluded,[68] its exercise by the employees) is limited by cardinal law. Thus, judges are not required to act under the direction of the person exercising employer powers as stipulated in the employment contract, but in accordance with the law, although, similar to Section 52 of Act I of 2012 on the Labour Code (hereinafter: Labour Code), they are obliged to comply with the relevant rules, customs and certain instructions in the relationship in question, but are otherwise independent and cannot be instructed.[69]

Nevertheless, there are certain cases, provided for by law, in which the judge may be instructed, and it is therefore appropriate to specify the substance of this right, in particular in order to ensure the effectiveness of the independence of the judge.

1. General characteristics and types of the right to instruct

The right to instruct can otherwise be described in terms of dependencies and relationships, which are thus very narrowly defined, but nevertheless still predominant, since, like employment relationships, they express how a given organisational unit and individual persons are related to management, and thus also reflect the quality of management consistency and compliance with work discipline.[70] This can be interpreted at several levels and in several ways as follows.

(a) Pursuant to Paragraph (b) of Section 119 of the Court Organisation Act, the president of the court is the person who exercises the employer powers conferred on him or her by law, including the right to give instructions. Traditionally, working under the instructions of the employer (person exercising employer powers) does not cause problems in practice.[71] In all circumstances, however, the president of the court must ensure that the exercise of the power of instruction is proper and not abusive.[72] The president of the court can give individual or specific instructions, but this is limited to a narrow range of cases specified by law (see below).

(b) In addition to individual instructions, the President of the NOJ may issue normative instructions covering

- 17/18 -

the entire judicial system, i.e. he or she may, within the limits of the law, issue rules binding on the courts, as well as recommendations and decisions in order to perform his or her administrative functions.[73] This could be, for example, an instruction to make technical (naming) changes following the Eleventh Amendment to the Fundamental Law, or the (mandatory) use of a protective PMMA[74] or (mandatory) ventilation during a state of danger.[75] The Constitutional Court points out as a matter of principle that "[t]he regulations issued by the President of the NOJ may be based only on principles and values which are derived from or directly deducible from the Fundamental Law, the Court Organisation Act and the Judges' Status Act. The content of the regulations must therefore remain within the scope of the regulation of matters relating to judicial administration and must not affect the independence of the judge who is to judge."[76] Therefore, for example, if the instruction of the president of the NOJ does not exceed the limits set by the Fundamental Law, the Court Organisation Act or the Judges' Status Act, i.e. it does not influence judicial activity, it does not violate the independence of the judge.[77]

(c) The Fundamental Law considers the judgement in panels as the main rule.[78] This puts presidents of chamber in a special position, as they act not as administrative heads but as professional heads: they lead the chamber and organise its work.[79] This is a non-dependent relationship, in which the chamber president as professional head is entitled to give professional "instructions" or guidance to other judges (including the drafter and the secretary) who are not in a dependent relationship with him or her.[80] Here, the chamber is the court, i.e. the judicial body consists of three offices, a president and two members. The office of President gives (is linked to) the opportunity of giving instructions.[81] In this case, the court is composed of two types of office, president and member, and more precisely of three officers, with the independence of the adjudicating body, the chamber, which allows the president to influence the members. The decision of the chamber is the result of the will of the members of the chamber (president, members), i.e. care must be taken to ensure that presidency is not linked to the opportunity of giving instructions which would render some of the independence of the members impossible. A chamber does not mean three judges who are completely independent of each other, because that would not really make sense. A chamber means that it must be independent in its judgement, so that it can decide together, and each judge can be independent in his or her judgement. There is indeed no dependency here, because this is only conceivable in a hierarchical organisation, i.e. in the case of judges in the administration. But in judging, there can be no such thing. The president of the chamber may not give instructions on professional grounds if this affects the independence of the judgement. The president's right can only be to facilitate the decision-making of the body (the chamber), but he or she cannot say what the decision should be, in view

- 18/19 -

of the independence of the individual judges: he or she can instruct to decide (instruct the members to decide together), but he or she cannot determine the content of the decision for each member.

2. The obligation to work

If we proceed from the provisions of the Labour Code mutatis mutandis, the person exercising employer powers is obliged to employ the judge in accordance with the rules applicable to his or her service and public law status, and to provide him or her with the necessary conditions of service.[82] Since the administration of justice is in the public interest, which requires that the judge is be able to judge at a level commensurate with his or her abilities, be physically available to the public seeking justice (e.g. attendance days, attendance time, etc.), or keep his or her judicial knowledge up to date through training, the requirements for this are typically employer instructions concerning working conditions. Accordingly, if this type of instruction is not aimed at shaping the exercise of judgement, it may be a defensible measure in terms of independence.[83]

Therefore, as a general rule, judges are obliged to appear at the court to which they are assigned in the right time and fit for work, in accordance with the court's organisational and operational rules, and to carry out their work in person, in accordance with the law, with the professionalism and diligence expected of them, in accordance with the laws, regulations, instructions and customs applicable to his or her work, in such a way as to cooperate with his or her colleagues and to maintain and enhance the authority of the courts, judicial independence and impartiality and confidence in the administration of justice.[84]

3. Determining the place and time of work

The place of work of a judge, according to his or her first appointment and then, on promotion, appointment to another judicial post, is the court as an institution or, more practically, the court to which he or she is assigned, its seat. It is clear, therefore, that judges should be present in the court building on the days of the trial and to the extent necessary for the trial, as this makes it easy to monitor the judge's work and to strengthen the professional and social relationship between judges.[85] But what about beyond that?

Judicial activity is a creative intellectual activity that raises the question of whether judges should be permanently present at their place of work or whether they can work outside it. In my opinion, intellectual work in general requires a high degree of freedom, which can be interpreted both in space and in time. A limit to creativity may be if a judge has to spend 40 hours a week in court. Let's just think about the fact that a judge often has to go through extremely complex cases and legislation, a lot of reading, thinking and reflecting, which can be done - typically - quietly and without disturbing others, and let's face it, in most workplaces, includ-

- 19/20 -

ing courts, this is not necessarily the case. In addition, I believe that comfort factors (e.g. home environment) or inspiring locations (e.g. park, garden) can greatly facilitate his or her work. Anyone who does intellectual work knows that it is often not time-bound, there are cases when thinking and work are simply impossible, but the fallacy of this is that, in a given case, if someone "catches" the train of thought, he or she will do it - obviously even beyond working hours - until the workflow is finished. To facilitate this, the Judges' Status Act defines the working time of a judge as a weekly time limit, with the possibility of setting it at a monthly or four-weekly limit.[86] The determination of these elements, taking into account the criteria of reasonableness and expediency, is the task and duty of the person exercising employer powers.

Ultimately, the question is whether a rigid and presence-based regulation or a permissive and non-prescriptive regulation is justified, beyond what is strictly necessary. In my view, from the judge's point of view, the higher the level within the system, the greater the freedom he or she should be given, since over time he or she will acquire the professional experience and social connections necessary to determine what is required to perform at a high level, and thus no special control or professional itinerary is necessary, since he or she is likely to perform his or her work properly without these "interferences."[87]

Another extremely important issue that can be included in the scope of work is the obligation of continuing training. In principle, there is no concern if the law provides for regular and compulsory continuing training, as is the case in the Judges' Status Act,[88] since there is no binding force for the judge to adapt his or her judgements to these, typically to the current position in the literature, but only to obtain a kind of up-to-date approach and explanation of the applicable law. Practical problems may arise from the consequences and sanctions related to the omission of training, since they may be decisive for the career of the judge concerned, and are therefore directly related to judicial independence.

The Hungarian legislation follows the solution that the judge is obliged to certify the fulfilment of the training obligation to the person exercising employer powers every three years, in the manner prescribed by the regulations issued by the president of the NOJ.[89] If the judge fails to comply with this obligation through a fault of his or her own, the president of the court must order an extraordinary inquiry and the judge concerned may not ipso iure apply for a higher judicial post.[90] I would add that the sanctioning of the "obligation for cooperation" in this way is not constitutionally problematic, because, on the one hand, it is free of charge and,[91] on the other hand, the timeliness of justice is an overriding public interest, in line with which it is a justifiable sanction against non-compliant judges, since their office cannot be terminated for this reason alone.[92] Although it cannot be ruled out that the conduct in question could, in the long run, be included in the scope of disciplinary offences, it

- 20/21 -

is not inconceivable that the service of a particular judge could be terminated in the context of disciplinary proceedings.

This point may also cover cases where the judge is assigned to the NOJ or to a relevant body. In such cases, if the judge is also performing a judicial function, he or she must, in addition to his or her judicial function, comply with the measures and instructions of the President of the NOJ or the head of the body concerned, as the person exercising employer powers, and must promote their effectiveness.[93]

Finally, a brief word on the issue of on-call duty and standby duty. Even though ipso iure the judge's working week cannot exceed 48 hours, it is still a very powerful power. Although the judge is entitled to a separate remuneration for the performance of on-call and standby duties, the influence of the person exercising employer powers is "doubly decisive" for the definition of the work, since work must be performed on the basis of the instructions of the person exercising employer powers, in compliance with the detailed rules laid down by the President of the NOJ.[94]

4. Non-compliance with instructions

Although the general rule is that the judge must comply with the instructions of the person exercising employer powers, there are cases where he or she is entitled or obliged to refuse to do so. On this subject, the Judges' Status Act is not as clear as Section 54 of the Labour Code, as there are no expressis verbis provisions on the cases of refusal to comply with an instruction. In the context of the system set out by the Judges' Status Act, it is useful to separate and discuss separately the adjudicative and the administrative instructions.

(a) In the first case, the law lays down clear requirements for the judge: as a general rule, he or she may not refuse to perform his judicial duties, must act in all cases without influence or partiality, and must prevent any attempt to influence the decision, while informing the president of the court.[95] Based on the wording of the law, these requirements essentially relate to the prevention of influence from outside the court system and to judicial activity, but they also apply to influence from within the court system. Therefore, if an instruction regarding adjudication were to come from within the court system, the judge would have the right to refuse the instruction, both under the Judges' Status Act and directly deriving from the Fundamental Law.[96] The situation is similar if the instruction from within is to commit a crime. In such a case, refusal to comply is the only legally correct and justifiable course of action.

(b) In the latter context, the picture is more nuanced. Administrative instructions can be normative and individual. There may in principle be fewer problems with normative instructions as a legal instruments of state administration, but the unlawful situation may arise as a result of the normative instruction. In this case, several variations are possible. (i) On the one hand, if the system of rules of a normative instruction is in conflict with the law, the higher one must be applied in accordance with

- 21/22 -

the principle of hierarchy of sources of law,[97] i.e. the refusal to give a specific instruction is lawful. (ii) On the other hand, if the normative instruction does not fall under the previous point, the possibilities for action against it are reduced. The court hearing service-related cases is not an option here, because it is not entitled to decide on the constitutionality of normative instructions, this can only be done by the Constitutional Court pursuant to Paragraph (2) of Section 37 of Act CLI of 2011 on the Constitutional Court (hereinafter: Constitutional Court Act). Therefore, if the independence of the judge guaranteed by the Fundamental Law is violated by the normative instruction as a whole or by some of its provisions, he or she may apply for direct constitutional review,[98] i.e. the refusal to comply with an instruction may be lawful. With regard to individual instructions, Paragraph (1) of Section 145 of the Judges' Status Act already provides a point of reference when it states that a service dispute may be brought against a decision (see instruction) taken by a person exercising employer powers and discretionary power if the employer has infringed the law governing the making of the decision.[99]

5. Other dependencies linked to the exercise of the employer powers

In order to ensure proper, uninterrupted and smooth administration of justice, the person exercising employer powers, as the administrative head responsible for the personnel and material conditions necessary for the administration of justice, may give a number of other "instructions" in addition to those mentioned above.

5.1 The so-called right to reverse rankings

As a general rule, a post of judge is filled by competition.[100] The basis for the appointment/transfer of judges in Hungary is the appointment system introduced in 2011, according to which judges are selected in a multi-tiered manner, through a competitive selection process. Pursuant to Decree No. 7/2011 (4 March) of the Ministry of Justice on the detailed rules for the evaluation of applications for judicial posts and the scores to be awarded in the ranking of applications, the selection of judges is carried out on two levels, one objective and one subjective.

It is of fundamental importance that the criteria for becoming a judge, as one of the most important guarantees of judicial independence, should seek to be as objective as possible,[101] thus excluding from the selection process "[the] personal, possibly illegitimate considerations and interests of those in a decision-making position."[102] However, as a matter of principle, it should also be possible for those in the court system to filter out candidates they consider unsuitable subjectively and without arbitrary action.[103] In this sense, it can also be a filter to keep unfit people from becoming judges.

The ranking of candidates for judge-ships is a strict process, where objective and professional criteria prevail and the order of candidates is ultimately

- 22/23 -

determined by the judicial chamber of the court to which the application is made. This order may be changed by the president of the court corresponding to the level of the court, who may propose the second or third candidate for appointment in place of the first candidate, giving reasons if he or she disagrees with the order, and then refer them to the NOJ.[104]

Crucially, the final decision on judicial applications is taken by the NOJ or, in the case of the highest judicial forum, by the President of the Curia.[105] They, like the presidents of regional courts and the courts of appeal, are ipso iure entitled to reverse rankings, i.e. they may decide to fill the post with the second or third candidate, subject to the same obligation to state reasons. However, there may also be a situation where the National Committee of Justices (hereinafter: NCJ), which supervises the President of the NOJ, does not agree with the decision of the President of the NOJ, in which case, or in the case of an unsuitable candidate, the application may bedeclared inconclusiveas a matter of ultima ratio.[106]

It is therefore clear that the presidents of the courts and the presidents of the NOJ and the Curia have, in principle, a decisive influence on who can fill judicial posts by changing the ranking.

5.2 Questions relating to the work and workload of judges

There are a number of issues that may arise in relation to the work and workload of judges, which can be summarised in the following points.

(a) The determination of the actual place of service and assignment are strong powers which apply to both judicial and non-judicial occupations. This power is vested in the president of the court in the case of a judge appointed for an indefinite term, and in the President of the NOJ in the case of a judge appointed for the first time (for a fixed term). As discussed above, the administrative heads may decide, with the judge's agreement, to entrust the judge with other activities in addition to or instead of his or her judicial activity.[107]

(b) Designation is also a discretionary power of administrative heads, so that the President of the NOJ may, on the recommendation of the presidents of the courts, designate a judge to hear a specific case or cases, subject in principle to the agreement of the judge concerned.[108] Special mention should be made of the designation of administrative and labour judges, who, since the abolition of the administrative and labour courts, are selected by appointment within the ordinary judicial system.[109] The designation is decided by the President of the NOJ, or, in the case of the curia judges, by the President of the Curia, on the basis of a proposal from the presidents of the courts, with a discretionary power.[110] What may be problematic is that the Judges' Status Act does not specify the criteria or conditions for designation or termination of designation, so it may be terminated by the President of the NOJ or the President of the Curia at any time, without

- 23/24 -

the consent of the designated judge and without objective reasons and the obligation to state reasons.[111]

(c) In practical terms, reassignment means the ordering of a judge to sit in a temporary place of service other than his or her place of assignment. This institution may already present a number of problems, as it does not require the consent of the judge concerned, and the judge may be reassigned to another place of service for one year every three years, in order to optimise the caseload or for the professional development of the judge concerned.[112] This, too, is a matter for the administrative heads to decide (in accordance with the law, of course), but it is clear that in some cases the sending of a judge here and there is a soft legal technique that can be used to marginalise the legitimate interests of the person concerned and to undermine his or her professional motivation.

(d) In relation to transfer, the Judges' Status Act sets strict conditions for the requirement of non-movability, defining two categories of cases: first, the place of service of a judge may be changed if the judge will be appointed to a judgeship in another court on the basis of a call for applications; second, if the closure of the court or a substantial reduction in its area of jurisdiction or area of competence makes this absolutely necessary. In such cases, the President of the NOJ may therefore apply a transfer.[113]

(e) The institution of case transfer has come under the spotlight in the context of the former case transfer practice of the President of the NOJ. Because of this practice, the Constitutional Court has also addressed the issue on the basis of the practice of the ECtHR, taking into account the (highly critical) opinions of the Venice Commission[114].[115] The panel interpreted the right to a lawful judge and the prohibition of deprivation of a lawful judge from the requirement of due process, and then drew the conclusion: the designation of the proceeding court based on the discretion of the President of the NOJ violated the right to a lawful judge as laid down in Section 8 of the Court Organisation Act (prohibition of deprivation of a lawful judge), and the legal regulation did not meet the so-called objective test of impartial judiciary.[116] It is important to note that case transfer is essentially designed to optimise the workload of the courts and to provide temporary relief. A possible overloading of the courts is a clear threat to the right to start and finish proceedings within a reasonable time, which is an intrinsic part of the right to a fair trial.[117] In the context of case transfer, its volume must always be examined, whether it justifies an extraordinary and disproportionate reduction in the workload of the court having jurisdiction (which it is intended to remedy), as this alone can be a legitimate basis for the parties' deprivation of the right to a lawful judge.[118] This is in line with the Constitutional Court's finding that the designation of a new judge/court [in the event of the disqualification of a judge/court] only meets the criterion of a lawful judge if it is made by another court within the judicial organisation, as regulated by procedural law, and not by the number

- 24/25 -

one administrative head. It can therefore be concluded that the previous practice of the legal institution was in clear violation of the right to a lawful judge and the prohibition of deprivation of the right to a lawful judge.[119]

(f) Under this point, the definition of the allocation of cases, in which the right to a lawful judge manifests, should also be examined.[120] The most important principle of the right to a fair trial, including the right to an impartial judgement, is the right to a lawful judge, which expresses the prohibition of deprivation of the right to a lawful judge, i.e. safeguards against arbitrary case allocation ("directed" assignments) and equality before the law.[121] "[T]o ensure these requirements, the majority of states with a judicial organisation based on the rule of law apply an automatic sign-off system, which is also a prerequisite for the establishment of an objective system of judicial career development and review. To this day, most Western European countries apply a fully automatic sign-off system, independent of the subjective decision of the head, thus avoiding the violation of the right to a lawful judge."[122]

The modification of the case allocation mechanism must be distinguished from the institution of a derogation from the case allocation mechanism. The former means a change in the case allocation mechanism itself, which may be done for reasons of service or for important reasons affecting the functioning of the court.[123] The latter means that a case is allocated differently from the published and valid case allocation mechanism. This may be done in cases provided for in procedural laws (the most typical example is the disqualification of a judge) and administratively (by decision of the head of the court acting alone) for important reasons affecting the functioning of the court (e.g. the judge's illness).[124] It can therefore be concluded that, if the assignment of the judge to the case is constitutional, predetermined and based on objective grounds (in an appropriate manner) by applying general rules,[125] the theoretical possibility of arbitrary interference is the lowest.

(g) Finally, it is also necessary to mention here the caseload. The Constitutional Court first examined the possible link between caseload and judicial independence in 2020. According to the Constitutional Court, the organisation of work within the court and the specific caseload of individual judges may be related to the quality of the work performed by judges, but it does not in itself affect the outcome of cases and the ability to rule on specific cases without influence.[126] Judges will not be subject to instructions depending on the number of cases they have, will continue to be subject only to the law and will in all cases make their decisions autonomously on the basis of their own internal convictions. Consequently the caseload (its quantitative predetermination or lack thereof) does in essence not affect the independence of the specific judge, it has no impact on it, i.e., in terms of constitutional law, there is no correlation with the (professional) dimension of judicial independence.[127] Thus, possible differences in the interpretation of the legislative provision

- 25/26 -

aimed at ensuring the observance of procedural and administrative rules, the proportionate workload of judges, the determination of the maximum caseload (previously criticised by the petitioner in a specific case), do not, in the opinion of the Constitutional Court, show any connection with any aspect of judicial independence.[128]

In my view, however, the determination of the caseload is correlated with judicial independence, namely through the qualification of the judge's practice in his or her judgments. This method can therefore be a way of breaking in non-compliant judges: they can get so many cases that they cannot solve well, which means that their rating will be poor, since rating is also a condition of independence. Even if judges qualify, it is the "objective" facts that will undermine the judge's performance: missing deadlines, insufficient clarification of the facts, rushed evidentiary procedure, a series of cases decided differently by the higher court, etc. The qualifier cannot do anything other than to establish these, if they are indeed the case.

5.3 Authorisation of other work and activities

In line with the role of the judiciary in the rule of law, individual judges are subject to very strict conflict of interest rules. Pursuant to Paragraph (1) of Section 40 of the Judges' Status Act, a judge may only perform certain tasks outside the performance of his or her office, but may not compromise his or her independence and impartiality or give the appearance thereof, nor obstruct the performance of his or her official duties. These paid activities, which are enumerated in the Act, can be carried out without infringing the independence of the judiciary, i.e. in a specific case, the theoretical chances of damaging the authority of the court and the trust in its independence and impartiality are extremely low. (In such activities, however, the judge will inevitably have to form an opinion, which is subject to strict limits.[129]) However, a judge may, with the prior consent of the person exercising employer powers, enter into another relationship aimed at work involving all or part of the working time of the judge in the context of his or her judicial service, i.e. it is at the discretion of the president of the court whether the judge may accept other employment under such conditions. Let's face it, this can also result in slowing down the career and professional development of judges. However, if the judge establishes other employment relationships outside working hours, he or she is only subject to the obligation of prior notification, and such relationships can only be prohibited if there is a conflict of interest under the Judges' Status Act.[130]

5.4 Leave

The rules on leave from service for judges differ substantially in certain respects from those in the Labour Code. Starting with the fact that judges are entitled to 30 days of basic leave at grade 1 and 40 days ipso iure from the age of 50.[131] Heads are given 5 days' ad-

- 26/27 -

ditional leave, under the condition that they cannot exceed 40 days' leave.[132] It is worth noting that, in addition to public holidays, judicial staff have an additional day off on the occasion of the Day of the Courts (15 July).[133]

Given the prominent role of the administration of justice, it is essential that the ordinary administration of justice, apart from judicial breaks,[134] is uninterrupted, and therefore leave must be planned and the person exercising employer powers decides when to grant leave, after hearing the judge, of course.[135] As a general rule, one quarter of the ordinary leave, except for the first three months of judicial service, must be granted at the time requested by the judge. The judge requesting the leave must give 15 days' notice before it is due to begin, and this may be derogated from only in exceptional circumstances.[136] The person exercising employer powers also has the discretionary power to authorise unpaid leave, which is also required to be extremely justified, but the total duration of unpaid leave cannot exceed 1 year. The Judges' Status Act provides for one exception to this, namely the authorisation by the President of the NOJ, which is only granted in cases warranting special consideration.[137]

5.5 Potential anomalies arising from regulation and other issues

(a) Under the law, in many cases a given judge will automatically become the president of chamber without having to apply,[138] but occasionally there may be no chamber to which he or she could be assigned (e.g. the presidents of the abolished administrative and labour courts automatically became the president of chambers of the regional courts, but no chamber could be formed around them). In such a case, the solution could be to place the judge concerned in an existing chamber where there is already a president of chamber and to rotate the president of the acting chamber on a case-by-case basis. Perhaps the judges in the other chamber or chamber are also placed in his or her chamber. In any case, there may be serious difficulties in putting this into practice. In this context, we may mention the discretionary power of the President of the NOJ to appoint a judge as the president of chamber, without a call for applications, in two cases, firstly, when a judge is assigned to the NOJ, after the judge has ceased to hold office,[139] secondly, where the former judge has been elected as a representative or advocate (i.e. his or her term of office as a judge is interrupted) and then, on expiry of his or her term of office, applies for reappointment as a judge (which he or she is granted if the conditions are met and on a proposal from the President of the NOJ) and the NOJ considers that his or her appointment as president of chamber is justified.[140]

(b) The courts have some internal conduct regulation issues that require further investigation. Examples of this could include the authorisation of participation in academic research projects or the conduct of investigations necessary for academic research by the President of the NOJ or (separately) the

- 27/28 -

president(s) of the court. In this context, however, there may be a conflict between research and expression and the public interest in the administration of justice.[141]

VI. End and termination of judicial service and liability for damages

1. End and termination of judicial service

The end of a judge's service is exhaustively specified in the law. Here, it is worth dealing not only with the end, but rather with the more interesting, and not previously discussed, cases of termination, which are more closely related to employer powers.

(a) It may seem trivial, but in view of Hungarian historical traditions, the oath of office of a judge is of particular importance, without which no judicial office can be filled. Therefore, as a general rule, 8 days are allowed from the date of appointment, and a maximum of 3 months (objective time limit) in the event of being prevented from taking the oath.[142]

(b) The declaration of assets is also a cardinal element, since the deliberate omission to make a declaration, or the deliberate misrepresentation or concealment of material facts or data, including those relating to the members of the household, or the withdrawal of such a declaration, also ends the service.[143] This obligation may also be imposed by the person exercising employer powers in exceptional circumstances.[144]

(c) A related and interesting problem is the former forced retirement of judges. Decision No. 33/2012 (17 July) of the Constitutional Court declared the Section of the Judges' Status Act that reduced the mandatory retirement age for judges from 70 to 62 years to be inconsistent with the Fundamental Law and annulled it. According to the panel's summary, the upper age limit for the service of judges can be set relatively freely by the constitutional legislator or, in the absence thereof, by a cardinal law, and no specific age for regulation can be derived from the Fundamental Law, but it is possible to introduce a new age limit (if it means a reduction of the upper age limit and not an increase of the previous age limit, as in this case) only gradually, over a sufficient transitional period, without prejudice to the principle of the judge's immovability.[145] Closely related to this is the removal of András Baka from his former position as President of the Supreme Court, who, due to his critical but not unprofessional opinions (also in connection with the law annulled in the decision), was not allowed by the new constitutional and legal rules to continue to hold the office of President, as the 17 years of judicial activity at the ECtHR no longer counted, and thus the required 5 years of judicial experience were not met.[146]

- 28/29 -

2. Liability arising out of judicial service

Given that many have already discussed the various approaches to judicial liability,[147] I will simply refer here to the fact that both the judge and the employer, i.e. the state, have a special liability for damages. The former is financially liable for any damage caused to the employer by a deliberate or grossly negligent breach of his or her obligations arising from his or her service (in full in the first case, and three times his or her monthly salary in the second case), and the employer may claim grievance award for the infringement of rights relating to personality.[148] The latter, however, is fully liable for any damage caused by the judge in the context of his or her service, regardless of his or her fault, and may be liable to pay grievance award for the infringement of rights relating to personality in the context of his or her service.[149]

VII. Conclusions and proposals

Generally speaking, judicial service, as an employment relationship, is a complex public-law relationship with elements of employment law, in which judges are obliged to work in accordance with the law, not with their employment contracts, and are also obliged to comply with the instructions of the person exercising employer powers, albeit within limits. The person exercising employer powers has a decisive influence on the selection and promotion of judges and on the personal and material conditions, i.e. working conditions. Although it cannot be said that the person exercising employer powers has powers that are as strong as those of the employer under the Labour Code, since cardinal laws place limits on them, their influence on judges is objectively evident, apart from the judgement.

Without repeating the specific findings of the paper, I would like to draw attention to and make the following proposals.

(a) On the issue of professional competence, it can be concluded that judges appointed for a fixed term are subject to a strict screening mechanism, which are more subjective, i.e. there is more discretion as to whether or not a person can be appointed as a judge for an indefinite term. In effect, this is a way of keeping unfit persons "indefinitely" from the judiciary. But it can also present problems. What if, for example, a judge has demonstrated his or her competence in all respects, and the professional opinions about him or her are positive. An example of this is the case of Judge Gabriella Szabó, which, as it is still ongoing at the time of writing, should be treated with particular caution, but offers interesting and exciting legal lessons.

The judge appointed for a fixed term, who has declared her wish to be appointed for an indefinite period, was subject to the normal review provided for in the Judges' Status Act at the beginning of 2021. As a result, in March of this year, she was declared unfit, on the basis of an examination and review, de-

- 29/30 -

spite the fact that the judge in question had successfully passed an interview with the Court of Justice of the European Union,[150] which strengthens rather than weakens her professional competence. She immediately challenged the review before the court of first instance, but, in the absence of a legal guarantee, her judicial service was terminated ipso iure on 30 June 2021, after the expiry of the fixed term, during the revision of the review, before a final decision could have been taken. Subsequently, the Curia, as the court of second instance to hear service-related cases, upheld the decision of the court of first instance hearing service-related cases in its final judgment No. Szfé9.2021/14 of 4 November 2021. The Constitutional Court rejected the constitutional appeal seeking to declare this decision of the Curia inconsistent with the Fundamental Law and to annul it in its Order No. 3239/2022 (18 May).

In view of all this, the hypothetical question may be raised, albeit with pragmatic content, as to what remedy would be available to a judge appointed for a fixed term if, following an "incompetency" review, the president of the court had not initiated the incompetency procedure. According to the Judges' Status Act, the service of a judge appointed for a fixed term ipso jure terminates after the expiry of the fixed term, but there is no subsidiary rule for the case where the president of the court fails to initiate the incompetency procedure.

(b) The example given in the previous point shows that there are fundamental legal shortcomings against the alleged unlawful removal of judges from the judiciary.[151] In this context, it would be justified, in order to provide greater protection for fixed-term judges, to amend the law in favour of fixed-term judges so that, if their review results in a finding of "unfitness," their judicial service does not automatically terminate at the end of the third year after their appointment, but only when a final decision has been taken by the court with jurisdiction over their cases.[152] According to the proposal of the NOJ, the judge would be exempted from the obligation to work during the period between the declaration of unfitness and the final decision, but would remain entitled to his or her average salary. This would prevent a judge who is declared unfit because of a possibly incorrect review from being left without a job and income for a longer period of time. For lost litigation, envisaging a partial repayment of this sum so that those declared unfit do not automatically sue. this would also be welcome, because even if a court hearing service-related cases subsequently finds that a judge is fit to serve, this does not automatically result in his or her reinstatement (see e.g. the Baka case). It is also not clear from the legislation whether in this case it is even possible to ensure that the person concerned is reappointed to her old post. This should be resolved by requiring courts hearing service-related cases to make decisions within a specified timeframe to meet this condition. It should also be stipulated that until a decision is made, the disputed judge's seat can only be filled temporarily (e.g. by re-

- 30/31 -

assignment), and that there should be no appointed judge (his or her position should be protected). At any rate, it is clear that the aptitude test before the expiry of a fixed term, without the establishment of stable safeguards, is undoubtedly a very strong power for the president of the court, which may inevitably be biased towards compliance with perceived or real expectations and, to this extent, represents a real risk to the requirement of judicial independence.[153]