Dr. Kristóf Benedek Fekete[1]: Models of the Central Administration of Courts* (JURA, 2024/2., 5-31. o.)

The author describes the solutions for the central administration of courts that are still in use nowadays and then, bearing in mind the requirement of judicial independence, presents their predominant and less mainstream models in a systematic and detailed manner. Starting with the relevant international and Hungarian literature, as well as the practice of the Venice Commission, the Consultative Council of European Judges, and the Constitutional Court of Hungary, the paper describes and analyses the various (mainly European) solutions for the central administration of courts as a model, in search of an answer to the question of what a "good" system for the central administration of courts is. In this context, the paper discusses, by examining regulatory schemes, the question of why courts require administration, the advantages and disadvantages of each solution, and how they can be combined, in particular in terms of the timeliness, efficiency, etc. of justice, judicial independence, and responsibility for justice, and what mechanisms can be put in place if the system is beset by dys-function(s). The paper concludes that no model is perfect or free of dysfunc-tion(s). Furthermore, since each model can always be operated in the light of the social, economic, historical, etc. aspects of a given state, it is not possible to say that one model is better or less good than another, also because of the lack of exact indicators. With the existence of appropriate constitutional rules and the resulting balanced operation, all models for the central administration of courts may be able to meet the expectations of the 21st century, provided that the administration is limited to the organisational operations of courts and does not substantially affect professional operation, i.e., the judicial processes and the related judicial independence.

- 5/6 -

I. Introduction

The judicial administration, court administration, or administration of courts is a highly complex set of activities,[1] involving activities linked to the functioning of the courts and bodies necessarily related to justice.[2] Nevertheless, the central administration of courts has areas that are more closely linked to the rule of law and the separation of powers, requiring further elaboration. This academic programme aims to determine and group together the most widespread and dominant models for the central administration of courts among European courts while remaining within the field of social sciences, especially law and political sciences.

The main objective of the research programme is to carry out a model study of the primary and less prominent sub- and sui generis categories of the central administration of courts, as outlined above, taking into account Hungarian and international trends. This is most interesting from the perspective that the central administration of courts can be divided into three basic, or predominant, groups, each with a different regulatory focus, but all of which may offer an accepted and used solution. Their most essential common feature is the provision of the personal and material conditions of judicial activities. Therefore, it is crucial to systematise, on an appropriate conceptual basis, the actors that positively or negatively impact judges, the courts, or even judgment.

When comparing the models of judicial administration, it is necessary to start with the central administration of courts and then to proceed towards the local administration system. In this context, it is appropriate to systematise the different regulatory schemes, highlighting the advantages and disadvantages of each of these models and how they can be combined, particularly in terms of equality, timeliness, efficiency, accessibility, etc., of justice, judicial independence and the (government's and state's) responsibility for justice. This analysis aims to outline, in the light of the abovementioned aspects, why courts require administration, who bears responsibility (for judging and administration), and what mechanisms can be put in place if the system is beset with dysfunction(s).

The study relies essentially on qualitative methods in terms of methodology. The analysis is mainly based on the interpretation and analysis of relevant legal documents using known interpretative techniques and exploring contexts and trends.

II. Groups of solutions for the central administration of courts

The central administration of courts is, in fact, the provision of the courts with the human and material resources necessary for judgment, which can be interpreted in several dimensions. According to a recent classification in the literature, administrative tasks can

- 6/7 -

be divided into eight groups [(1) regulatory, (2) administrative, (3) personal, (4) financial, (5) educational, (6) informational, (7) digital and (8) ethical].[3] The content of these categories may, of course, vary from country to country. However, their substantive implementation or lack thereof can make the administration of courts more measurable, particularly in terms of judicial independence, accountability, transparency, efficiency, and the achievement of social control.[4]

It should be noted that since there have been courts, there have been defenders and critics of their performance, as well as debates about how to make their administration more efficient. The key to efficiency lies above all in ensuring judicial independence through a separate judicial administration, which is a prerequisite to the development of the courts' capacity to resolve disputes in a manner that is fair (i.e. reinforces fundamental democratic values), economical and speedy.[5] Court administration must necessarily be independent, i.e., the solutions for the central administration of courts can be grouped on the basis of a scale "yardstick" of independence.

At the level of the central administration of courts, international and Hungarian literature uses different typologies, which in many cases overlap but are sometimes difficult to compare. This raises the question of whether the administration of courts has a universal (international) content, and if it does, then what is it.[6] In order to determine this, it is most useful to follow international literature and apply the organisational and functional approach to find the smallest common multiple that can be used to classify the central administration of courts.[7] This common point is the degree to which judicial independence is achieved (in principle).

Summarising the relevant works on the subject, it can be concluded that the central administration of courts assumes three main models,[8] generally ministerial, self-government and mixed, complemented by different sub-models.[9] These can of course be extended, along certain aspects of distinction, by further categories and sub-categories (e.g. socialist, court service, co-responsible or supreme court model)[10], real or hypothetical solutions, and templates.[11]

1. The ministerial model

Traditionally, the basic model of central administration of courts is the so-called "purely" external court administration model,[12] which, because of the characteristic predominance of the government, can also be called the ministerial model.[13] Initially, only this single, unitary or executive model existed,[14] and then, because of concerns about judicial independence, accountability, and performance improvement, "the longest standing model"[15] lost its predominance,[16] but, with some modifications, many countries around the world still opt for it (e.g., Austria, the Czech Republic or Germany).[17]

In the ministerial model, the government, typically the minister of justice/ ministry of justice, has the central role,[18] covering all administrative matters re-

- 7/8 -

lated to the courts.[19] As the unipersonal, i.e. monocratic, organ responsible for the central administration of courts, the minister of justice has the characteristic of exercising his or her functions and powers jointly with other officials belonging to the body. However, they are essentially subject to his or her instructions, in other words, all decisions are attributed to the minister of justice, either by the minister himself or herself or by his or her staff acting for him or her and according to his or her guidance, but their actions and their consequences are attributed to the minister of justice and, through him or her, to the state.[20] In this respect, the minister of justice as a "[m]onocratic organ is a cooperative organisation of subordinate bodies and offices based on a division of functions, but governed by the will of the head of the organ."[21]

In general, judges also have essential administrative functions in the ministerial model (e.g., selection of judges, disciplinary matters, etc.), and, in states that have such a system, the role of judges in court administration gradually increases,[22] i.e. judges have a strong influence on the administration of courts,[23] despite the ministerial model, although it is not typical to create a separate body for this purpose.[24] In this model, court administration is perceived to be more closely linked to the executive (e.g., in the appointment and dismissal of presidents of courts[25] and the promotion of judges in general[26]), which may raise problems of functional division of court administration, but this model presupposes the most detailed constitutional regulation and should in no way affect the independence of judges in their judgments.[27]

It would be misleading to suggest that, in this model, judges have little say in the appointment and promotion of their colleagues, or the general and day-to-day management of the courts, or that the ministry of justice has unilateral control over these processes.[28] All of these may have a significant role to play in the ministerial model, for example in the state legislature, the head of state and other bodies. In addition, in states with such a model, the presidents of the courts of appeal and the supreme courts usually have a prominent role, as they will be consulted by the minister of justice on crucial issues such as judicial career paths and appointments. Moreover, some appointments and promotions can only be made with their agreement. Thus, while it is called a "ministerial model," in practice, it is a form of administration beyond the executive.[29]

A substantial positive aspect of this model is that the minister/ministry of justice has direct government/parliamentary responsibility for the administration of the courts,[30] due to the stronger government "presence," but it also has a weakness, as this is where the risk of unilateral concentration of power is most significant.[31] In this context, the development of resources and judicial budgets is a particularly important area, which is itself a susceptible area, as it is easy to see that the shaping of human and material resources can have a direct impact on the equality, timeliness, efficiency, and accessibility of justice.[32] In other words, financial

- 8/9 -

autonomy is elementary, because "[a]n organisation or institution that is exclusively or predominantly financed by public funds has a 'semblance of autonomy', or at least is doomed to (also) meet the expectations of the financier. With other people's money, there is no unlimited autonomy, or if there is, it can only be apparent."[33] In any case, the key question in such a model is where, for how long and to what extent the "financier" grants autonomy, and how it draws the boundaries of its intervention possibilities. In this context, it is practical to use strong self-limitation, i.e., to guarantee the (financial) autonomy and independence of the funded organisation in the constitution or in other act.[34] Nevertheless, as far as the question of responsibility is concerned, the minister is responsible for practically everything.[35] He or she is also responsible both directly to the government of the day and indirectly to the electorate, and so faces constant threats of removal or non-reappointment (e.g. not being re-appointed following a general election).

Two further arguments can be made in favour of this model. On the one hand, the courts are also state organs, integrated into the state structure. Therefore, the government's responsibility extends to them even if the judges are independent in their judgments. The latter may not make the former questionable because the functioning of the state structure as a whole must reflect the power of the people, primarily through parliament (representation of the people) and government (state governance). On the other hand, the courts' budget is always decided by parliament, and no other organ can take its place because no other body can escape this responsibility, even if the judgment must be independent.

It is worth briefly highlighting the particular case where the central administration of ordinary and administrative courts are separated (e.g., in the Czech Republic[36] or Germany). A case in point is Hungary, where the ministerial administrative model of administrative courts was almost introduced in 2020. The ministerial administration of administrative courts, which had been envisaged for a long time, could have been implemented, according to the legislator's vision, by a model based on the cooperation and balance of powers between judicial bodies (bodies of judicial self-government), court leaders and the minister responsible for justice. This "balanced cooperation model" would have been a guarantee that would have institutionally excluded the imposition of extra-legal "wills" in judgment.[37] Nevertheless, because of the controversy surrounding the rule of law, the Government, wanting to avoid even the suspicion that there might be any problem with the independence of the judiciary in Hungary (see below), first postponed the introduction of the administrative court system without any deadline, and later decided not to introduce it at all.[38]

In summary, the ministerial model is generally an acceptable solution.[39] However, it is vital to stress that in the 21st century, this model of judicial administration is not possible without the efficient and substantial involvement

- 9/10 -

of elected judicial bodies and respect for the guarantees of judicial independence.[40] Nonetheless, it is also necessary to record that "[t]he more involvement of executive and legislative powers in judicial administration the more potential threats exist to judicial independence."[41] In practice, the "merging" of the powers of the executive and the judiciary may violate the principle of separation of powers. Conflicts are coded in the model if the relations between the persons involved in court administration are not sufficiently formalised, as the lack of this inevitably leads to the politicisation of judges and courts, which may ultimately result in a constitutional crisis. In this model, abusive practices are therefore very easy to occur, because there are hardly any institutionalised checks and balances, and, therefore, this model requires a high level of professional ethos and self-restraint from the ministry, its head and its staff (which is why it is not recommended for the former socialist countries). In connection with this, there is another inescapable phenomenon, which is that for the average law-seeking public, the question of responsibility is blurred, i.e., the public believes that almost all responsibility for the quality of the functioning of the courts lies with the courts and judicial bodies, because the average citizen does not perceive a systemic distinction between the responsibility of the executive and the judiciary. Consequently, the reputation of judges and courts is very fragile for reasons beyond their control, whether directly or indirectly due to the actions of the executive.[42] Avoiding this requires mature and objective constitutional regulation, communication and information,[43] which is not a practical problem in states with a well-developed democratic tradition,[44] because the actors of the administration act with sufficient restraint, based as they are on traditions that replace formal checks and balances.

Table 1 - Countries using the ministerial model (own ed.)[45]

| No. | Country | Administration body/bodies | Constitutional provision(s) | Act(s) |

| 1. | Austria | The Federal Ministry of Constitutional Affairs, Reforms, Deregulation and Justice | The Federal Constitution of Austria Art. 82-94 | Court Organisation Act (RGBl. Nr. 217/1896) |

| 2. | Czech Republic | Ministry of Justice of the Czech Republic | The Constitution of the Czech Republic Art. 79 | Act No 6/2002 on law courts and judges |

| 3. | Germany | The Federal Minister of Justice and federal ministries of justice | The Constitution of the Federal Republic of Germany Art. 92-104 | German Judiciary Act as published on 19 April 1972, as last amended by Article 4 of the Act of 25 June 2021 |

| 4. | Belarus | Ministry of Justice of the Republic of Belarus | The Constitution of the Republic of Belarus Art. 109-116 | Code of the Republic of Belarus on judicial organization and status of judges and other regulatory legal acts No. 139-3 of June 29, 2006 |

- 10/11 -

2. The self-government model

The second model is characterised by strong, outward-looking independence,[46] which is why it is also called "autonomy-oriented," managerial, self-government, or simply judicial model.[47] This model of judicial administration, in the context of a move away from executive power, and its spread, can be explained essentially by the interrelationships between legal families,[48] the compensatory transition from authoritarian to democratic systems,[49] and the process of Europeanisation (standardisation).[50]

The main feature of the self-government model is that there is extensive "judicial self-administration," i.e., a body consisting exclusively or mostly of judges decides on administrative matters,[51] although the weight of this body varies from one state to another.[52] In this model, we can distinguish between northern and southern,[53] civil law and common law,[54] or strong and weak types,[55] typified in different ways. Under the aegis of autonomy, powers may extend not only to the selection and promotion of judges but also to budgetary and organisational administration,[56] i.e., they may perform all tasks related to the organisation, management, and operation of the court.[57] In other words, these bodies can administer and depending on the legislation in question, counterbalance the executive in terms of power.[58]

Collective or collegiate organs, which implement the self-government model, are organs that are made up of several offices and are usually established with the same or similar powers in terms of exercising the powers vested in the organ. The offices in such an organ are usually equal, i.e., the officers who hold them, the members of the collective organ, have equal rights, decide together, and are jointly responsible for the decisions taken. Given that each office is created with the same rights and obligations, there are no substantial differences between the certain offices and certain officers.[59]

It is proposed that these bodies should be made up of a majority or sole majority of judges, and it is encouraged by international documents that "colleagues" elect the officers to the body from among themselves.[60] There is a European trend, especially in the light of the intention to join the EU,[61] towards the implementation of the judicial model, especially in countries that applied the ministerial model in the past, which in turn implies a complete transformation of responsibilities.[62] In this model, the said bodies are established by the constitution, which regulates their main rules, and their primary function is to protect and strengthen judicial independence, since all decisions (recruitment, training, evaluation, appointment, promotion, transfer, disciplinary law etc.), functions and powers related to the career of judges are vested in them.[63] Another advantage of self-governance is that, as administration is done within the organisation itself, the judicial body responsible for

- 11/12 -

administration is able to secure the material and personnel resources without the distorting influence of the executive (or even the legislature), thus increasing the efficiency and quality of justice.[64] The obvious aim of this model, and also its greatest potential, is to create a body that would (at least) explicitly separate judicial career decisions from party politics, while ensuring effective accountability.[65]

In addition to the still "unclear"[66] advantages (because judicial administration raises severe questions of measurability, and, in my view, only those involved in it can have so-called "indicators"), the literature mentions several negative aspects and effects that can be objectively detected. Such serious problems include judicial independence and accountability. On the one hand, for accountability, it is imperative to establish that the mechanism of holding to account is difficult to understand for corporate bodies, which is a clear and transparent responsibility for ministerial administration, but is divided or even lost for corporate bodies. This is a problem in itself, as transparency is achieved, but accountability is compromised.[67] On the other hand, this model can also have a solid isolating effect, contributing to so-called informal practices such as patronage in the negative sense, nepotism or corruption.[68] In addition to these external factors, self-governance faces many internal threats. Judicial independence is compromised even, and even more so, when colleagues or superiors influence judges.[69] Judges as individuals, as well as groups, can have self-interest, just like other actors in the branches of power, which is why judicial independence can be understood as a "consequence of self-restraint by powerful actors."[70] In most European countries, the separation of judicial power from the political branches and the protection against undue influence from them is also a fundamental requirement, but it cannot stop at formal (legal) instruments. Precisely because, if certain tasks and powers are taken away from other actors and placed within the judiciary, they can also become a problem, but they cannot be dealt with externally. For example, influential actors in the court system may directly or indirectly, consciously or unconsciously, favour judges with certain qualities or characteristics (e.g., selection or promotion of judges). Changing and distorting the judiciary in this way is a long-term goal that requires sustained and focused action. Conversely, it is an immediate so-called chilling effect when the actors in the decision-making position use their influence (e.g., through disciplinary or transfer powers) to present and prescribe desirable or undesirable actions to the judges.[71] It is also a criticism of self-governance that there is, in fact, no parliamentary political responsibility over the actions of the judiciary, which also raises some problems. This is because self-governance tends to be inward-looking (as was also the case in Hungary[72])[73] as there is little external control in this model, and in the absence of feedback, the judiciary can easily become detached from society, elitist, etc.[74]

- 12/13 -

Table 2 - Countries using the self-government model (own ed.)[75]

| No. | Country | Administration body/bodies | Constitutional provision(s) | Act(s) |

| 1. | Albania | High Council of Justice | The Constitution of the Republic of Albania Art. 135-147/dh | Law No 115/2016 For the governing bodies of the justice system |

| 2. | Bosnia and Her- zegovina | The High Judicial and Prosecu- torial Council of Bosnia and Herzegovina | The Constitution of Bosnia and Herze- govina IV.C.1. Art. 4 | Law on court of Bosnia and Herzegovina (49/09) |

| 3. | Bulgaria | Supreme Judicial Council | The Constitution of the Republic of Bulgaria Art. 129-133 | Judicial System Act, pub- lished in State Gazette No 64/2007 |

| 4. | North Macedo- nia | The Judicial Council of the Republic of North Macedonia | The Constitution of the Republic of North Macedonia Art. 98-105 | Law on Courts (58/2006, 62/2006, 35/2008, 150/2010, 83/2018 and 198/2018) |

| 5. | Estonia | The Council for Administra- tion of Courts | The Constitution of the Republic of Estonia Art. 146-153 | Courts Act (RT I 2002, 64, 390) |

| 6. | France | The High Council for the Judiciary | The Constitution of October 4, 1958 Art. 64-65 | No 58-1270 of 22 December 1958 enacting the institu- tional Law on the status of the judiciary |

| 7. | Greece | The Supreme Judicial Council of Civil and Criminal Justice | The Constitution of Greece Art. 90 | The Code on the Organiza- tion of Courts and Status of Judicial Officers (Law 1756/1988). |

| 8. | Georgia | The High Council of Justice / The Administrative Office of the Courts | The Constitution of the State of Georgia Art. 64 | Organic Law of Georgia on Common Courts |

| 9. | Croatia | The National Judicial Council | The Constitution of the Republic of Croatia Art. 124 | Judiciary Act (141/2004) |

| 10. | Kosovo | The Kosovo Judicial Council | The Constitution of the republic of Kosovo Art. 108 | Law No. 06/L-054 on Courts |

| 11. | Poland | The National Council of the Judiciary | The Constitution of the Republic of Poland Art. 186-187 | Act of 12 May 2011 on the National Council of the Judiciary |

| 12. | Lithu- ania | The Judicial Council | The Constitution of the Republic of Lithuania Art. 112 | The Law on Courts of the Republic of Lithuania (31 May 1994, No. I-480) |

| 13. | Moldova | The Superior Council of Magis- trates | The Constitution of the Republic of Moldova Art. 122-123 | Law of the Republic of Moldova of July 20, 1995 No. 544-XIII about the status of the judge |

- 13/14 -

(Table 2, cont.)

| No. | Country | Administration body/bodies | Constitutional provision(s) | Act(s) |

| 14. | Monte- negro | The Judicial Council | The Constitution of Montenegro Art. 126-128 | Law on the Judicial Council and Judges (no.011/15 of 12 March 2015, 028/15 of 3 June 2015) |

| 15. | Italy | The Superior Council of the Magistracy / The High Council of the Judiciary | The Constitution of the Italian Republic Art. 104-110 | Judiciary Act (n. 195 of 1998 and 44 of 2002.) |

| 16. | Portugal | The High Council for the Judiciary | The Constitution of the Portuguese Republic Art. 217-218 | Law 21/85, July 30th; Law 36/2007, August 14th; Law 52/2008, August 28th |

| 17. | Romania | The Superior Council of Magis- tracy | The Constitution of Romania Art. 125(2), 133-134 | Law No 304/2004 on judi- cial organization, Law no.317/2004 on the Superior Council of Magis- tracy |

| 18. | Spain | The General Council for the Judiciary | The Spanish Con- stitution Art. 122 | Law 6/1985, July 1st, on the Judiciary and amendments introduced by Law 4/2013, June 28th |

| The Constitution | ||||

| 19. | Serbia | The High Judicial Council | of the Republic of Serbia Art. 153-155 | Law on Judges (no 116/2008, 58/2009) |

| 20. | Slovakia | The Judicial Council of the Slovak Republic | The Constitution of the Slovak Repub- lic Art. 141a | Act No. 185/2002 Coll. on the Judicial Council of the Slovak Republic |

| The Constitution | ||||

| 21. | Slovenia | The Judicial Council | of the Republic of Slovenia Art. 130-131 | The Courts Act and Judicial Service Act |

| 22. | Republic of Tür- kiye | The Council of Judges and Prosecutors | The Constitution of the Republic of Türkiye Art. 159 | Law No. 6087 on the Coun- cil of Judges and Prosecu- tors |

| 23. | Ukraine | The High Council of Justice | The Constitution of Ukraine Art. 131 | Law of Ukraine on the Judi- ciary and Status of Judges (2016, No. 31, p.545) |

Anyhow, it is important to highlight another solution in the self-government model, which is widely known in the literature as European Model of Judicial Councils, also known as "Euro-model."[76] In this "perfect" model of self-government, six criteria would have to be met, as follows: "(1) a judicial council should have constitutional status; (2) at least 50% of the members of the judicial council must be judges and these judicial members must be selected by their peers, i.e. by other judges; (3) a judicial council ought to be vested with decision-making and not merely advisory powers; (4) a judicial council

- 14/15 -

should have substantial competences in all matters concerning the career of a judge including selection, appointment, promotion, transfer, dismissal and disciplining; (5) a judicial council must be chaired either by the President or Chief Justice of the Highest Court or the neutral head of state; and (6) court presidents and vice-presidents are not precluded from becoming members of the judicial council."[77] This solution was taken into account by post-communist states in their judicial reforms during their transformation in the early 1990s as the only "right" model, developed by the European Commission and the Council of Europe, that can overcome the previous failures of justice in these states. Therefore, most Central and Eastern European countries (e.g., Bulgaria, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Romania, Slovakia and Slovenia) adopted this "pan-European template."[78]

In addition to the above, it should also be mentioned that recent research is trying to distinguish between the different judicial councils regarding the separation of powers, i.e., depending on their relationship with the other branches of power, and to establish them theoretically as "fourth-branch" institutions. The justification and the timeliness of these studies is given by the fact that there are states where judicial councils have been hijacked by both political branches (e.g. in Poland) and the judiciary (e.g. in Slovakia or Georgia) and used for suspicious purposes, but there are also Western European democracies where these councils have been highly politicised (e.g. in Spain) or are the subject of struggles within justice itself (e.g. in Italy). As there are both academic and political repercussions for judicial councils,[79] they can be grouped along certain lines. As a result of this distinction, four types of council models can be identified: "(1) a judge-controlled judicial council, which is a self-governing representative of a judicial branch; (2) a politician-controlled judicial council, which formally represents the judiciary but is de facto controlled by political actors; (3) an inter-branch judicial council, which works as a coordinating institution representing all three traditional branches of power; and (4) a fourth-branch judicial council, which is autonomous of any of the three powers."[80]

Unfortunately, it only looks good on paper. In particular, the fact that the presidents of the courts can be members of these councils in the countries of south-eastern Europe strongly contributes to the fact that the feudalisation and nepotism that is taking place in society as a whole is also taking root in justice, in the courts and in the judiciary, where it is happening speedily and systematically.[81] This allows, among other things, the conclusion that judicial councils cannot protect justice from societal phenomena (such as feudalisation or nepotism), and that if presidents of courts can play a dominant role in the judicial council, they have a vested interest in transforming the judiciary into a system of feudal, "good" jobs, and they are very active in doing so. Moreover, the conflict between the interests of the judicial ad-

- 15/16 -

ministrative body and the apparatus that implements these decisions may also be a problem in this model.

In summary, in this model, judges can determine the framework and directions of court administration independently (or through a subordinate body/bodies).[82] More specifically, it is the choice and application of directions, methods, and instruments within the legislative framework since the judiciary has no power to legislate. It could be stated that a clear organisational separation applies, which objectively guarantees the principle of independence of justice in organisational terms.[83] It is also universal from the point of view that it has discretion over the main issues and decisions, so its role is inescapable, but not without concern, as responsibility is sometimes lost in the "fog" of corporate decision-making. What is absolutely sure is that this model is the most widely promoted and applied in Europe, as it is thought to raise the fewest problems.[84]

3. The mixed model

Following the traditional classification, the third group of the "administrative triad" includes the so-called mixed model, also known as court service[85] or partner model[86]. Generally speaking, this model is more "decentralised" than the ministerial model,[87] but it does not reach the level of autonomy of the self-government model. There is an element of competition in this intermediate solution, since, according to certain criteria, the functions and powers of court administration are shared between a general council for the judiciary and/or other bodies of judicial self-government and the government (mainly the minister of justice or an organ subordinate to or linked to it),[88] usually in favour of the latter.[89] This can be achieved by having a body that is independent of the government but part of public administration or a hybrid (sui generis) body, i.e., an office that is separate from the ministry of justice but is formally subordinate to a particular minister. Depending on the country in question, the executive and the judiciary may enter into (framework) agreements on functions and powers or organisational matters (see e.g. His Majesty's Courts and Tribunal Service or the Irish Court Service).[90] It could be said that this model is a kind of "stepchild," an intermediate solution to the two other models discussed above, since it combines the characteristics of both, although they are only found in different proportions in the analysis of a single country. Thus, the administration of the countries applying this model presents a very different picture, given their socio-economic, historical, etc. characteristics.[91]

- 16/17 -

Table 3 - Countries using the mixed model (own ed.)[93]

| No. | Country | Administration body/bodies | Constitutional provision(s) | Act(s) |

| 1. | Belgium | The High Council of Justice | The Constitution of Belgium (1831) Art. 151 | The Judicial Code |

| 2. | Denmark | The Danish Court Administra- tion | The Danish Consti- tution Art. 59-65 | The Danish Court Adminis- tration Act of 26 June 1998 (Law no. 401) |

| 3. | United King- dom* | His Majesty's Courts and Tri- bunals Service (Lord Chancellor and Lord Chief Justice) | The United King- dom has no written constitution. | Courts Act (2003) |

| 4. | Finland | The National Courts Adminis- tration of Finland | The Constitution of Finland Art. 98-105 | Courts Act (673/2016) |

| 5. | Nether- lands | The Dutch Council for the Judiciary | The Constitution of the Kingdom of the Netherlands Art. 112-122 | Judicial Organization Act |

| 6. | Ireland | The Judicial Council | The Constitution of Ireland Art. 34-37 | the Judicial Council Act 2019 |

| 7. | Iceland | The Judicial Administration | The Constitution of the Republic of Iceland Art. 98-103 | Act on the Judiciary |

| 8. | Latvia | The Council for the Judiciary | The Constitution of the Republic of Latvia Art. 82-86 | Law on Judicial Power |

| 9. | Malta | The Commission for the Ad- ministration of Justice | The Constitution of Malta Art. 101A-101B | Commission for the Admin- istration of Justice Act |

| 10. | Norway | The Norwegian Courts Admin- istration | The Constitution of the Kingdom of Norway Art. 86-91 | Courts of Justice Act |

| 11. | Sweden | The Swedish National Courts Administration | The Constitution of the Kingdom of Sweden Chapter 11 | The Swedish Code of Judi- cial Procedure (1998) |

* Includes the organs for judicial administration of England and Wales, Scotland, and Northern Ireland.

This is commonly reflected in the composition of these councils (number of members, governmental and/or judicial qualities, selection, single or collective leadership) and their legal powers. On the one hand, the councils for the judiciary are typically responsible for selecting and promoting judges. On the other hand, the government is responsible for the budget, the creation of the organisational system, and operational tasks.[92] However, there may be a different distribution of responsibilities, but it is important to stress that the scales of judicial administration in this model are tipped towards the government,[94] as typically the minister of justice/ministry of justice will continue to hold the general organisational powers, with the traditional functions and powers remaining concentrated in the executive.[95] The functions of these special councils (bodies) are thus typically of a managerial, "housekeeping" nature, which are "designed to prevent moral hazard: by insulating the

- 17/18 -

judiciary from the management of resources, the council prevents corruption or distraction from the core task of judging."[96]

In summary, the design of council for the judiciary is a key issue in this model, as their composition (e.g. whether they should have members with other professions) can determine the subsequent bargaining process and can also affect the authority of the courts,[97] but even an independent body cannot offer an automatic guarantee of proper administration, as it can become a battleground for the partners that set it up. It should not be neglected that special powers are usually exercised (e.g., opinion, selection, promotion), but traditional "privileges" are still retained by the executive (e.g., budget[98]). Anyhow, the fact that governments can take political responsibility and that council for the judiciary have the opportunity to shape the system from a professional point of view is positive. It should be noted that this model is also favoured in parliamentary systems of government by the Mount Scopus Standards, as well as by the International Bar Association Standards, as it is considered the most appropriate way to ensure the effective administration of lower courts.[99] Finally, as in the ministerial model, in the mixed model it is also a practical precondition that the actors do not abuse their formal powers, but carry out their activities with self-discipline, self-restraint and a proper professional ethos, aided by established traditions.

4. Hybrid or sui generis models

In Europe and beyond, there are of course regimes that are only partially similar to the previous patterns, but which are mixed and have a rather different solution in substance (e.g. Hungary, Israel or some Latin American countries). Given the diversity of solutions, it is appropriate here to briefly highlight only a few countries' solutions.

a) Hungary has a sui generis solution for judicial administration. The central (general) responsibilities of the administration of courts are borne by the President of the National Office for the Judiciary (hereinafter: NOJ), who is a single head elected by the Parliament for a term of 9 years on the recommendation of the President of the Republic. The central administration of courts and the work of the President of the NOJ is supervised by the National Judicial Council (hereinafter: NJC) a body composed exclusively of judges (the judges themselves elect the members). In this concept, the President of the NOJ has broad powers (e.g., personnel, budget, case allocation, training, information, etc.), while the NJC mainly has an opinion- and proposal-making role. Other judicial self-government bodies are also involved in the administration of courts.[100]

- 18/19 -

Table 4 - Countries using the hybrid/sui generis model (own ed.)[101]

| No. | Country | Administration body/bodies | Constitutional provision(s) | Act(s) |

| 1. | Azerbai- jan | The Judicial Legal Council | The Constitution of the Republic of Azerbaijan Art. 125 | Law dated 10 June 1997 of Azerbaijan Republic on Courts and Judges |

| 2. | Cyprus | The Supreme Council of Judi- cature (consisting of the President and 12 judges of the Supreme Court) | The Constitution of the Republic of Cyprus Art. 157 | Administration of Justice Act of 1964 (Law 33/64 as amended) |

| 3. | Israel | The Minister of Justice, the Director of Courts and the President of the Supreme Court | Israel has no writ- ten constitution. | Courts Law (1984) |

| 4. | Kazakh- stan | The Supreme Judicial Council | The Constitution of the Republic of Kazakhstan Art. 82 | On Judicial System and Sta- tus of Judges in the Repub- lic of Kazakhstan December 25, 2000 N 132 |

| 5. | Luxem- bourg | The Superior Court of Justice (and the Grand Duke) | The Constitution of Luxembourg 1868 Art. 84-95 | The amended law of 7 March 1980 on judicial organization |

| 6. | Hungary | The President of National Of- fice for the Judiciary | The Fundamental Law of Hungary Art. 25(5) | Act CLXII of 2011 on the Legal Status and Remunera- tion of Judges; Act CLXI of 2011 on the Organization and Administration of the Courts |

| 7. | Russia | The Council of Judges | The Constitution of the Russian Federa- tion Art. 118-129 | The Law of the Russian Federation No. 3132-1 on the Status of Judges in the Russian Federation |

| 8. | Armenia | The Supreme Judicial Council (shared with the Minister of Justice and Corruption Preven- tion Commission) | The Constitution of the Republic of Armenia Art. 173-175 | Judicial Code of the Repub- lic of Armenia |

| 9. | Switzer- land | Provisions are different from canton to canton. (The federal judiciary of Switzerland consists of the Federal Supreme Court with own administration, the Federal Criminal Court, the Federal Patent Court, and the Federal Administrative Court.) | The Federal Consti- tution of the Swiss Confederation Art. 188-191c | Provisions are different from canton to canton |

b) Israel has a three-component system centered around the Director of Courts, who is responsible for the regular day-to-day management of the courts. In this system, the Minister of Justice lays down the administration of the courts (i.e., he or she has ultimateadministrative responsibility), but the President of the Supreme Court, who has extensive powers, has a say in court administration (e.g., through presidential orders). Thus, many administrative decisions, such as the appointment of the Director of Courts or the presidents of courts, are subject to approval by the President of the Supreme Court. In this model, the Director of the Courts is a

- 19/20 -

"servant of two masters" while guaranteeing the day-to-day management, and must, therefore, mediate between the Minister of Justice and the President of the Supreme Court. It is clear that informality plays a vital role in this context.[102]

c) Many countries in Latin America have historically had a so-called Supreme Court model.[103] In this model, the presidents of the supreme courts used their influence, in the constitution-making processes, to shape the composition of the judicial councils, their functions and powers, etc., to their own ideas that served the judges. The stronger the influence of the supreme judicial forum, the more it shaped these processes, thus gaining a more expansive right over the careers of judges and, by extension, the administration of the courts.[104]

5. The special status of supreme courts

The prominent role of the supreme judicial forums is inherent in the problem of court administration, thus raising the question of whether a separate administration of supreme (ordinary) courts and/or a "specialised"[105] administration of supreme courts (typically supreme administrative courts) can coexist with any of the models of judicial administration described so far.

In the models described above, the supreme courts (more precisely, their presidents) have, to varying degrees, a wide range of "powers" in both domestic and transnational justice, which can affect judicial careers, case assignments, but also jurisprudential, financial or even media powers.[106] It should be stressed that, although court administration is not directly reflected in judgments, it nevertheless has an impact on them, as with organisational and status issues, through "[t]he activities of the heads of administration (from the allocation of cases to the conditions for adjudication, the continuous monitoring of administrative activity and to the examination of judicial activity)."[107] The realisation and implementation of all these presuppose a high degree of autonomy, which is not very different from the autonomy required by other (non-judicial) bodies, such as the need to ensure legal, internal and external organisational, inancial, and managerial autonomy. In other words, it is typically necessary to guarantee autonomous legal personality, protection against the removal of powers, autonomous budget and management, and general management and leadership in general.[108] It should be noted, however, that the guarantee of autonomous legal personality is an explicitly Soviet socialist standpoint. It is not the legal personality governed by private law that is important, but (quite independently of it) adequate powers, guarantees, etc. under public law. In Germany, even the Federal Constitutional Court has no legal personality, which does not impair its independence. In short, a very sharp distinction must be made between (irrelevant) legal personality governed by private law and status, position, and powers governed by public law.

The autonomy of supreme judicial forums can be reduced to a general

- 20/21 -

and specific requirement because of their typically lame distinctiveness. In general, since the supreme judicial forum is a court, it is subject to the same requirements as any other court. The striking difference, the specificity, is that the forum at the apex of justice is not one of many, as it has powers that other courts do not have.[109] In Europe, it is mainly in the regime-changing (post-socialist) countries that we see that they are separate not only in their functionality but also in their organisation, which emphasises the independence of the judiciary.[110]

The requirement of judicial independence applies not only to ordinary courts but also to specialised supreme courts as autonomous forums because they too enjoy autonomy in their personal decisions, in their cases assignment, and in their work to ensuring the uniform application of the law[111]. It is therefore possible that a given state has a model of court administration and, in addition, a special status and autonomy for the ordinary and specialised supreme court(s). This presupposes, of course, the separation of ordinary and specialised courts,[112] i.e., the existence of specialised courts that are partly or wholly separate from ordinary courts.[113]

III. Summary and de lege ferenda proposals

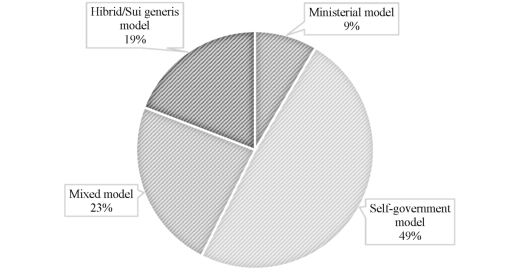

Generally speaking, there are a number of variants of international and Hungarian central judicial administrative arrangements, with ministerial, self-government and mixed models and their various sub-models (e.g. strong or weak self-government councils) as the dominant patterns. In the ministerial model, an external body, typically the minister of justice/ministry of justice, linked to the government, acts alone as the central entity and handles administrative tasks. With elected judicial councils, the self-government model relies on internal autonomy and is characterised by extensive "judicial self-administration." The composition of the administrative body varies considerably from state to state but is typically composed of a majority or absolute majority of judges. In contrast, in the mixed model, administrative responsibilities are shared between the minister of justice/ministry of justice and elected judicial bodies (councils), varying from country to country.[114]

It can also be concluded that no model is free of dysfunction(s). Since the issue of court administration is a highly complex issue, the choice of model of court administration must always take into account the specificities of the state concerned, if only because the social perception of the functionality of each model has a significant impact on its reputation. That is why each model can always be operated in the light of the social, economic, historical, cultural, etc. aspects of a given state, it is not possible to say that one model is better or less suitable than another, also because of the lack of exact indicators. In my view, with the existence of appropriate constitutional rules and the resulting balanced operation, all models for the central administration of courts

- 21/22 -

may be able to meet the expectations of the 21st century, provided that the administration is limited to the organisational operations of courts and does not substantially affect professional operation, i.e., the judicial processes and the related judicial independence.[115]

The concrete conclusions and recommendations of this paper are as follows:

a) The ministerial model is generally an acceptable solution. However, it is vital to stress that in the 21[st] century, this model of judicial administration is not possible without the efficient and substantial involvement of elected judicial bodies and respect for the guarantees of judicial independence. However, it is also necessary to note that as the executive and the legislature gain ground in the court administration, the threat to judicial independence gradually increase. In practice, the "merging" of the powers of the executive and the judiciary may violate the principle of separation of powers. Conflicts are coded in the model if the relations between the persons involved in court administration are not sufficiently formalised, as the lack of this inevitably leads to the politicisation of judges and courts, which may ultimately result in a constitutional crisis. In this model, abusive practices are therefore very easy to occur, because there are hardly any institutionalised checks and balances, and, therefore, this model requires a high level of professional ethos and self-restraint from the ministry, its head and its staff (which is why it is not recommended for the former socialist countries). In connection with this, there is another inescapable phenomenon, which is that for the average law-seeking public, the question of responsibility is blurred, i.e., the public believes that almost all responsibility for the quality of the functioning of the courts lies with the courts and judicial bodies, because the average citizen does not perceive a systemic distinction between the responsibility of the executive and the judiciary. Consequently, the reputation of judges and courts is very fragile for reasons beyond their control, whether directly or indirectly due to the actions of the executive. Avoiding this requires mature and objective constitutional regulation, communication and information, which is not a practical problem in states with a well-developed democratic tradition, because the actors of the administration act with sufficient restraint, based as they are on traditions that replace formal checks and balances.

b) In the self-government model, judges can determine the framework and directions of court administration independently (or through a subordinate body/bodies). More specifically, it is the choice and application of directions, methods, and instruments within the legislative framework since the judiciary has no power to legislate. It could be stated that a clear organisational separation applies, which objectively guarantees the principle of independence of justice in organisational terms. It is also universal from the point of view that it has discretion over the main issues and decisions, so its role is inescapable, but not without concern, as responsibility is sometimes lost in the "fog"

- 22/23 -

of corporate decision-making. What is absolutely sure is that this model is the most widely promoted and applied in Europe, as it is thought to raise the fewest problems. However, it should not be concealed that it raises many problems: judicial inward-looking (judicial independence is often compromised because judges are increasingly dependent on their superiors, who are also judges), detachment from citizens, etc., elitism (misinterpretation of "we are above politics"), lack of control (professional evaluation has no serious consequences because judges evaluate each other), impossibility of political evaluation (there is always political evaluation, but there is nothing the parliament can do), etc. It is correct that this is the least of our worries regarding separation of powers, but it is not without problems. Otherwise, the system may be appropriate from a purely organisational point of view, but in the administration of the courts, as in all administration, one cannot ignore the determinants beyond the organisational elements: method (confrontational or cooperative), culture (the standard of political and legal culture), socialisation processes (how one becomes a judge, what one learns in the process, personal influences, etc.), moral scruples, trust in the courts, etc. Thus, these all have an impact on the administration (e.g., a judge socialised based on respect for authority, with a lower political and legal culture, less concerned with moral considerations is more likely to be loyal to political power even if the administration would otherwise be neutral or self-administering in principle).[116]

c) The design of council for the judiciary is a key issue in the mixed model, as their composition (e.g. whether they should have members with other professions) can determine the subsequent bargaining process and can also affect the authority of the courts, but even an independent body cannot offer an automatic guarantee of proper administration, as it can become a battleground for the partners that set it up. It should not be neglected that special powers are usually exercised (e.g., opinion, selection, promotion), but traditional "prerogatives" are still retained by the executive (e.g., budget planning and adoption). [The latter is, in fact, maintained by the ruling majority (the parliamentary majority and its government) because they are, after all, the legitimate and legal power that is the result of the exercise of power by the people. The judiciary cannot be isolated, it cannot be self-serving (the basic function of judges is to resolve individual legal conflicts, not to exercise a privileged and independent power for its own sake). In my viewpoint, it is indispensable to have representation from other professions: not only lawyers, prosecutors, and the executive, but also, for example, notaries public and members of parliament, as many more viewpoints can be raised in the discussions. Publicity, both in the administration and in the evaluation of judicial work, should be at least as important. If there is no change in these, the organisational model is almost irrelevant because each has advantages

- 23/24 -

and disadvantages.] Anyhow, the fact that governments can take political responsibility and that council for the judiciary have the opportunity to shape the system from a professional point of view is positive. It should be noted that this model is also favoured in parliamentary systems of government, as it is considered the most appropriate way to ensure the effective administration of lower courts. Finally, as in the ministerial model, in the mixed model it is also a practical precondition that the actors do not abuse their formal powers, but carry out their activities with self-discipline, self-restraint and a proper professional ethos, aided by established traditions.

d) In Europe and beyond, there are regimes that are only partially similar to the previous templates, which are mixed but essentially different, and which are collectively referred to as hybrid or sui generis administration models. It is not easy to assess them all together because of their diversity, but it can be concluded that each system tries to achieve independent, clear, efficient, and transparent central administration of courts, taking into account its own social, cultural, economic, historical, legal, etc. aspects. In these models, informal channels and political "struggles" play a noticeably more significant role, and their specific characteristics, therefore, call for further research.

e) The prominent role of the supreme judicial forums is inherent in the problem of court administration. Whether ordinary or specialised, the presidents of supreme judicial forums are responsible for a number of key decisions, which can be interpreted at national and transnational levels. Presidents of supreme forums can have a strong influence (at least in their organisations) on judicial careers, case assignments, jurisprudence, finance, or even media power. The autonomy of supreme judicial forums can be reduced to a general and specific requirement because of their typically lame distinctiveness. In general, since the supreme judicial forum is a court, it is subject to the same requirements as any other court. The striking difference, the specificity, is that the forum at the apex of justice is not one of many, as it has powers that other courts do not have (e.g. policy-making, legislative proposal or unifying powers).

f) There is one more inescapable question to be answered: what mechanisms can be put in place if the system of court administration in question is beset with dysfunction. In my viewpoint, a court administration system with dysfunctions can be adjusted in several ways, considering the constitutional rules and constitutional system of a given country. Firstly, the constitutional courts, as neutral organs of the state that are not attached to other branches of power can exercise constitutional control over court administration (e.g., when in 2013, the Constitutional Court of Hungary declared the practice of the President of NOJ in case transfers to be inconsistent with the Fundamental Law and in violation of international treaties).[117] This control is judicial, i.e. it is exclusively reactive, i.e., it presupposes the filing of a petition to the constitutional court, and the yardstick can

- 24/25 -

only be constitutional law. Institutional control, however, cannot be based on these case-by-case reviews of the constitutional court. In addition, account must be taken of the special relationship between constitutional courts and supreme courts, which is often fraught with tensions, which means fruitful cooperation cannot be expected, especially in the former socialist countries. Secondly, parliaments can play an unavoidable role, as they can change the whole central administration of the court system (ultima ratio character) through legislation. Thirdly, the administrators themselves have an essential role to play since poor management can ruin good regulations, and proper management can achieve success despite poor regulations.

Figure 1 - Models of judicial administration in Europe (n=47) (own ed.)

g) It is difficult to make universal de lege ferenda recommendations, but it can be said to be useful in any model that it is essential (1) to have sufficiently precise and clear constitutional rules; (2) to have adequate separation of powers; (3) to have rules that are as objective and formal as possible; (4) to establish and maintain clear rules of responsibility and accountability; and (5) to maintain or strengthen the authority of the relevant leader(s) and to exercise restraint.

h) Lastly, regarding administration systems, assessing the existing and functioning administration system itself would be worthwhile. Periodically, the case law and administration solutions should be examined and qualified by sociological, psychological, economic, and legal efficiency studies, as well as by evaluating social perception, confidentiality, etc. This kind of feedback is essential because changes must al-

- 25/26 -

ways start from the existing system (in any case, there can be no radical organisational change in the administration either, since internal operating processes and practices may be strong enough to make their way even within the new organisational setting), evaluating experience and seeking to find solutions that offer guarantees. It should be stressed that this is not just a question of legal regulation, but also as much a question of mentality, political culture, and people's personal convictions. ■

NOTES

* Supported by the ÚNKP-23-3. New National Excellence Program of the Ministry for Culture and Innovation from Source of the National Research, Development and Innovation Fund. The manuscript was completed on April 15, 2024. The starting point of this paper is a previous work of the author. See Fekete Kristóf Benedek: A bírósági központi igazgatás alapvető modelljeiről. Kodifikáció 2019/2, pp. 17-23.

The author would also like to thank Péter Tilk (Professor and Head of the Department of Constitutional Law, Faculty of Law, University of Pécs) for the irreplaceable professional support provided for the study, as well as for the indispensable comments and suggestions, József Petrétei (Professor, Department of Constitutional Law, Faculty of Law, University of Pécs) and Herbert Küpper (Associate professor, Andrássy Gyula German Speaking University Budapest; Doctor et Professor Honoris Causa, Faculty of Law, University of Pécs).

[1] See Besenyei Beáta: Az igazságszolgáltatáshoz fűződő jogalkotási problémák a XXI. században. Source: http://www.mabie.hu/index.php/cikkektanulmanyok/58-besenyei-beata-az-igazsagszolgaltatashoz-fuzodo-jogalkotasi-problemak-a-xxi-szazadban (Date of download: January 19, 2024.)

[2] Cf. Ürmös Ferenc: A szocialista bírósági igazgatás kialakulása és típusai. Acta Universitatis Szegediensis de Attila József Nominatae - Acta Juridica et Politica 1979/8, pp. 35-37.

[3] For more details, see Šipulova, Katarína - Spáč, Samuel - Kosař, David - Papouškov, Tereza - Derka, Viktor: Judicial Self-Governance Index: Towards Better Understanding of the Role of Judges in Governing the Judiciary. Regulation & Governance 2023/1, pp. 27-28.

[4] Cf. Decision No. 22/2019. (VII. 5.) of the Constitutional Court of Hungary, in Decisions of the Constitutional Court (hereinafter: DCC) 2019, Volume 1, 581, 605.

[5] Cf. Fox, Natalie - Firlu, Jakub - Mikuli, Piotr: Models of Courts Administration: An Attempt at a Comparative Review. In: Mikuli, Piotr (ed.): Current Challenges in Court Administration, The Hague, Eleven International Publishing, 2017. (online version: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4365251) p. 1. For more details on this issue, see Wheeler, Russell: Judicial Administration: Its Relation to Judicial Independence. Williamsburg, National Center for State Courts, 1988.

[7] See Árva (2022) p. 12.

[8] Cf. Point 48 of Opinion No. 18 (2015) of the Consultative Council of European Judges (CCJE) on the position of the judiciary and its relation with the other powers of state in a modern democracy (London, 16 October 2015) CCJE(2015)4

[9] See Fekete (2019) p. 19. According to the classification of court administration by responsibility, we can distinguish, for example, (1) an exclusive judicial responsibility model, which can be divided into individual (responsibility is concentrated in one judge) and collective (responsibility is concentrated in a collegial judicial panel) sub-models; (2) an exclusive executive responsibility model; (3) a shared executive judicial model, which can be divided into the sub-models of vertical division of responsibility (the responsibility for court administration is vested in the judiciary in some cases and to other branches of power in other cases), horizontal division of responsibility (the administration of the higher courts is vested in the judiciary and the administration of the lower courts is left to the executive), joint responsibility (the responsibility for court administration is the complete and joint responsibility of the executive and the judiciary), and proportional collegial body responsibility (the responsibility for court administration is vested in a collegial body with a fixed proportion of executive and judiciary representation); (4) a multibranch responsibility model (the responsibility for court administration is vested in a body representing all three branches of powers and other organs); (5) a separate independent organ responsibility model (responsibility for court administration is vested in a separate and independent public body). See Shetreet, Shimon: Crossborder Enforcement and Recognition of Judgements and Awards in a Globalised World. Verwaltungsakademie Bordesholm and Kiel University 1214 July 2018. The Legal Position of Non-Recognized (or Partly Recognized) States. Source: https://www.eastlaw.uni-kiel.de/de/events/presentations/22-shetreet.pptxv (Date of download: June 4, 2024.)

[10] Cf. Bobek, Michal - Kosař, David: Global Solutions, Local Damages: A Critical Study in Judicial Councils in Central and Eastern Europe. German Law Journal 2014/7, p. 1265.; Castillo-Ortiz, Pablo: Judicial Governance and Democracy in Europe. Sheffield, Springer, 2023. p. 5.

[11] In summary, see Baar, Carl - Benyekhlef, Karim - Gélinas, Fabien - Hann, Robert - Sossin, Lorne: Alternative Models of Court Administration. Ottawa, Canadian Judicial Council, 2006. pp. 9-11.

[12] Cf. Decision No. 97/2009. (X. 16.) of the Constitutional Court of Hungary, in DCC 2009, 870, 876. See Fekete (2019) p. 20.

[13] See Badó Attila: Az igazságszolgáltató hatalom alkotmányos helyzetének és egyes alapelveinek összehasonlító vizsgálata. In: Tóth Judit - Legény Krisztián (eds.): Összehasonlító alkotmányjog. Budapest, CompLex Kiadó Jogi és Üzleti Társadalomszolgáltató Kft., 2006. p. 176.; Hack Péter - Majtényi László - Szoboszlai Judit: Bírói függetlenség, számonkérhetőség, igazságszolgáltatási reformok. Budapest, Eötvös Károly Közpolitikai Intézet, 2007. p. 37.

- 26/27 -

[14] See, for example, Fox - Firlu - Mikuli (2017) 5. o.; Castillo-Ortiz, Pablo: The politics of implementation of the judicial council model in Europe. European Political Science Review 2019/4, p. 503.; Árva (2022) p. 13.

[15] See Bobek - Kosař (2014) p. 1265.

[16] See Rieger, Alexander Verfassungsrechtliche Legitimationsgrundlagen Richterlicher Unabhängigkeit. Frankfurt, Peter Lang, 2011. p. 209.; Castillo-Ortiz (2023) p. 4.

[17] Cf. Mikuli, Piotr: In Search of the Optimal Court Administration Model for New Democracies. 10th World Congress of Constitutional Law 2018 SEOUL 18-22 June 2018. Workshop #18: New Democracies and Challenges to the Judicial Branch. pp. 6-7. Source: http://tinyurl.com/3hjhyhk6 (Date of download: January 11, 2024.)

[18] Cf. Decision No. 13/2013. (VI. 17.) of the Constitutional Court of Hungary, in DCC 2013, 440, 440506.; Decision No. 22/2019. (VII. 5.) of the Constitutional Court of Hungary, in DCC 2019, Volume 1, 581, 605. This is not necessarily always true either, because in Germany, for example, there are five supreme courts at the federal level (ordinary, general administrative, labour, social, and fiscal), and different federal ministries with specific powers for the subject matter administer the court(s).

[19] See Csink Lóránt: Mozaikok a hatalommegosztáshoz. Budapest, Pázmány Press, 2014. p. 142.

[20] Cf. Zippelius, Reinhold: Allgemeine Staatslehre. München, C. H. Beck'sche Verlagsbuchhandlung, 1999. p. 103.

[21] Cf. Dreier, Regel: Organlehre. In: Kunst, Hermann - Herzog, Roman - Schneemelcher, Wilhelm (eds.): Evangelisches Staatslexikon. Stuttgart - Berlin, Kreuz Verlag, 1975. pp. 1703-1704.; Mikuli (2018) pp. 6-7.

[22] See Kosař, David: Beyond Judicial Councils: Forms, Rationales and Impact of Judicial Self-Government in Europe. German Law Journal 2018/7, p. 1574.

[23] See Kosař (2018) p. 1587.

[24] Cf. Árva (2022) p. 13.

[25] See Bobek - Kosař (2014) p. 1265. A concrete example is Germany, where the administration of the courts, at the federal and national levels, is in the hands of ministries. However, the legislature predominates as a counterweight in major promotion and appointment matters. At the same time, judges strongly influence their career paths and have exclusive decision-making power in disciplinary and assignment matters. Also compensating is the automaticity of assignment, which is left to the judiciary, but also the diverse self-government bodies of judges, which have a strong informal influence. In sum, ministerial administration, in its pure form, only applies in matters unrelated to judgment (e.g., communication, technical matters supporting judgment, or further training). See Badó Attila - Márki Dávid: A német bírósági igazgatás alapjai. Comparative Law Working Papers 2020/1, p. 2. and foll.

[26] Cf. Kosař, David: Politics of Judicial Independence and Judicial Accountability in Czechia: Bargaining in the Shadow of the Law between Court Presidents and the Ministry of Justice. European Constitutional Law Review 2017/3, p. 106.

[27] See Berthier, Laurent - Pauliat, Hélène: Administration and Management of Judicial Systems in Europe. Strasbourg, European Commission for the Efficiency of Justice, 2006. pp. 10-11.; Marosi Ildikó - Nagy Gusztáv: A bíróságok igazgatása. In: Csink Lóránt - Varga Zs. András (eds.): Bírósági-ügyészségi szervezet és igazgatás. Budapest, Pázmány Press, 2017. p. 86.

[28] In Germany, at least, many ministerial employees are "assigned judges". This allows judicial ethics to prevail to a certain extent in the ministry, making its administration less "executive" compared to other ministries.

[29] See Bobek - Kosař (2014) p. 1265.

[30] See European Commission For Democracy Through Law (Venice Commission): Hungary Opinion on the Law on Administrative Courts and on the Law on the Entry Into Force of the Law on Administrative Courts and Certain Transitional Rules. Adopted by the Venice Commission at its 118[th] Plenary Session (Venice, 15-16 March 2019) CDL-AD(2019)004. p. 10

[31] Cf. Decision No. 13/2013. (VI. 17.) of the Constitutional Court of Hungary, in DCC 2013, 440, 467.; Decision No. 97/2009. (X. 16.) of the Constitutional Court of Hungary, in DCC 2009, 870, and foll.

[32] The German model, for example, clearly rejects the corporative autonomy of the judiciary, i.e. court administration, including the budget and the promotion of judges, is not taken away from the ministry and transferred to judges for independent, uncontrollable and uninfluenceable administration. Thus, the German model does not follow the Anglo-American example, according to which "[j]udicial independence must include the collective independence of the court as a body but leaves the care of the judiciary to the government". See Bäumlin, Richard - Azzola, Axel (eds.): Kommentar zum Grundgesetz für die Bundesrepublik Deutschland. Band II. Neuwied, Hermann Luchterhand Verlag, 1984. p. 952.

- 27/28 -

[33] See the dissenting opinion of László Kiss, Member of the Constitutional Court of Hungary, to Decision No. 41/2005. (X. 27.) of the Constitutional Court of Hungary. In DCC 2005, 459, 492.

[34] Cf. the dissenting opinion of László Kiss, Member of the Constitutional Court of Hungary, to Decision No. 41/2005. (X. 27.) of the Constitutional Court of Hungary. In DCC 2005, 459, 492-493.

[35] The financial aspect of this responsibility implies accountability for allocating resources and for the results achieved through their use, i.e., accountability for efficient management, which can ultimately enhance the quality of judgment. Cf. Martin, Wayne Stewart: Court Administrators and the Judiciary -Partners in the Delivery of Justice. International Journal For Court Administration 2014/2, p. 8.

[36] See Badó Attila - Márki Dávid: Bírósági igazgatás Csehországban. Comparative Law Working Papers 2021/1, p. 2.

[37] Cf. the amicus curiae filed by the Ministry of Justice in case No. II/242/2019 of the Constitutional Court of Hungary. p. 16. Source: https://tinyurl.com/24x66x4r (Date of download: June 10, 2024.)

[38] For more details, see Fekete Kristóf Benedek - Kéri Valentin - Nadrai Norbert: Kiválasztás, előmenetel, igazgatás avagy a bírói pálya szegélyei. In: Tilk Péter - Fekete Kristóf Benedek (eds.): Az igazságszolgáltatással kapcsolatos egyes folyamatok alakulása az elmúlt években. Pécs, PTE ÁJK, 2020. pp. 155-181.

[39] Cf. Decision No. 22/2019. (VII. 5.) of the Constitutional Court of Hungary, in DCC 2019, Volume 1, 581, 613-614.

[40] Cf. European Commission For Democracy Through Law (Venice Commission): Rule of Law Checklist. Adopted by the Venice Commission at its 106[th] Plenary Session (Venice, 11-12 March 2016) CDL-AD(2016)007-e; and Makai Lajos: A bírósági igazgatás aktuális kérdései. Conference Presentation, Pécs, 2018.

[41] See Ginter, Jaan: Judicial Independence and/or(?) Efficient Judicial Administration. Juridica International 2010/1, p. 111.

[42] Cf. Fox - Firlu - Mikuli (2017) pp. 5-6.

[43] For more details on court communication, see Fekete Kristóf Benedek: Az igazságszolgáltatás kommunikációja. Magyar Jog 2022/11, pp. 642-653.

[44] See Badó Attila - Márki Dávid: A bírósági igazgatás modellje Finnországban és Ausztriában. Comparative Law Working Papers 2020/1, p. 3.

[45] The table is based on the work of Castillo-Ortiz (2023) and the relevant domestic legal sources. In countries where the constitution does not (precisely) contain the body that administers the judicial system, the articles on courts are referred to as the whole regulation of the system.

[46] See Berthier - Pauliat (2006) p. 12.

[47] See Marosi - Nagy (2017) p. 87.; Árva (2022) p. 13.

[48] See Castillo-Ortiz (2019) p. 506.

[49] Countries, typically post-socialism ones, with a strong "tradition" of executive interference in the court system want to compensate for the democratic deficit they experienced in the past, and one of the adequate solutions is the self-government model. Cf. Badó, Attila: The Constitutional Challenges of the Judiciary in the Post-socialist Legal Systems of Central and Eastern Europe. In: Csink, Lóránt - Trócsányi, László (eds.): Comparative Constitutionalism in Central Europe: Analysis on Certain Central and Eastern European Countries. Miskolc-Budapest, Central European Academic Publishing, 2022. p. 343.; Bunjevac, Tin: From Individual Judge to Judicial Bureaucracy: The Emergence of Judicial Councils and the Changing Nature of Judicial Accountability in Court Administration. University of New South Wales Law Journal 2017/2, pp. 822-823.

[50] See Castillo-Ortiz (2019) p. 506.

[51] See Csink (2014) p. 142.

[52] See Decision No. 97/2009. (X. 16.) of the Constitutional Court of Hungary, in DCC 2009, 870, 877.

[53] See Voermans, Wim - Albers, Pim: Councils for the Judiciary Countries. Strasbourg, Council of Europe, European Commission for the Efficiency of Justice (CEPEJ), 2003. p. 10. This distinction may also be valid for the mixed model, as the authors examined the councils according to their nature, i.e., their functions and powers may overlap.

[54] See Castillo-Ortiz (2019) p. 505-507.

[55] See Castillo-Ortiz (2019) p. 505.

[56] See Horváth Miklós: Az igazságügy stratégiai megújítása. Budapest, Nemzeti Közszolgálati Egyetem, 2014. p. 18.

[57] See Baar, Carl - Greene, Ian: Judicial Administration. In: Dunn, Christopher (ed.): The Handbook of Canadian Public Administration. Toronto, Oxford University Press, 2010. p. 132.

- 28/29 -

[58] See Hack - Majtényi - Szoboszlai (2007) p. 37.

[59] "However, as a result of efficient operation and in order to facilitate decision-making within the body, there may be certain differences in the office of the chairperson of the body session (primus inter pares), which are not essential, for example, about the chairperson's duties, the maintenance of discipline, the representation of the body, or the facilitation of decision-making (the chairperson's vote in the event of a tie). In the case of a collegiate organ, a distinction may be made between the different functions within the body according to the powers attached to each function, but the functions and powers of the organ may nevertheless be exercised only jointly by all the members of the organ." See Petrétei József: Szerv, tisztség, tisztviselő. Pécs, June 9, 2023, Online Conference Presentation: A jog és a jogállamiság aktuális kérdései.

[60] See Point 17 of Opinion No. 10 (2007) of the Consultative Council of European Judges (CCJE) to the attention of the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe on the Council for the Judiciary at the service of society. This Opinion has been adopted by the CCJE at its 8th meeting (Strasbourg, 21-23 November 2007); Point 27 of Recommendation CM/Rec(2010)12 adopted by the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe on 17 November 2010 and explanatory memorandum [Council of Europe: Judges: independence, efficiency and responsibilities.]; Aarli, Ragna - Sanders, Anne: Judicial Councils Everywhere? Judicial Administration in Europe, with a Focus on the Nordic Countries. International Journal For Court Administration 2023/2, p. 14.

[61] See Aarli - Sanders (2023) p. 7.

[62] See Voermans - Albers (2003) p. 7.

[63] Cf. Autheman, Violaine - Elene Sandra: Global Best Practices: Judicial Councils - Lessons Learned from Europe and Latin America. IFES Rule of Law White Paper Series 2004. p. 6.

[64] See Voermans - Albers (2003) pp. 71-72.

[65] See Šipulova - Spáč - Kosař - Papouškov - Derka (2023) p. 24.

[66] See Šipulova - Spáč - Kosař - Papouškov - Derka (2023) p. 23.

[67] This is especially the case if the individual member of the body cannot express his or her opinion specifically, such as the constitutional judge in a dissenting opinion.

[68] See Šipulova - Spáč - Kosař - Papouškov - Derka (2023) p. 23.

[69] Cf. Kosař, David - Spáč, Samuel: Conceptual-ization(s) of Judicial Independence and Judicial Accountability by the European Network of Councils for the Judiciary: Two Steps Forward, One Step Back. International Journal for Court Administration 2018/3, p. 39.