Gergely Gosztonyi: Alternative media in the European media regulation (Annales, 2013., 191-224. o.)

1. Introduction[1]

As media developed, four main models of media broadcasting have emerged. The first two models have developed in a different order in Europe and the US: while in the US the model of commercial media broadcasting was the first to emerge, in Europe it was public service broadcasting that people first encountered. The remaining two models mentioned by relevant literature on media are the media of dictatory systems, characterized by propaganda, and the fourth is community/alternative type of media broadcasting. At the present, the propaganda model no longer exists in the European media landscape, and a media model consisting of three actors, i.e. public service, commercial and community media prevails.

Lately, one might have noticed that all media are trying to become community media: an image change of public service media is also seen as something that is 'at the same time the first step in public service media becoming community media',[2] and an otherwise excellent Hungarian journalist, while discussing the broadcasting of the 2012 Olympic games by the Hungarian public service television, states that public service media 'simply forgot to appear in community media'.[3] In my opinion, the above is a great example of the confusion in today's media speech and regulation concerning community media, a concept adapted from English.

- 191/192 -

Replying to the question is made even more difficult by the technological boom of the past couple of years. We spend our time enchanted by blogs, tweets and Facebook status updates, and the average person might almost feel inferior if he does not have at least a profile page on Facebook. Such use of the concept of community media, that we might call commercially oriented, complicates the situation of community/alternative media even further. This is getting even more difficult in Hungarian language communication about media, due to the fact that there is just one term which is used for two distinct subjects. In English, classic community media and the new, web 2.0 community media are called 'community media' and 'social media'. To be able to distinguish these two in Hungarian, perhaps the use of the terms 'consumer/audience media' and 'community media' would be the most suitable, indicating that in the case of technology based new media the involvement of the audience is based on commercial and not on community building considerations. In classic community media, the audience is not just a targeted 'object', but a part of the community of the medium just like the makers of the medium. So, in the case of classic media, we have a community and not just an audience.

Various terms used in different countries for community media have almost identical meanings: it is a type of media broadcasting that is different from the mainstream media, usually operated in a democratic manner, with programmes prepared mostly by volunteers for their own communities about topics most relevant and interesting for them, and it is not a goal of the medium to make financial profit. The present paper shall discuss the emergence and directions of regulation of this type of media.

2. A short summary of European media regulation

The need for a common European media regulation in the narrow sense and for a joint audiovisual policy have first emerged with the beginning of satellite broadcasting in the beginning of the 1980's. Even though that, according to the principle of subsidiarity, a guiding principle of European Union, media legislation issues are subject to legislation of the member countries, there are initiatives to change or at least soften this rule. As Section 94 of the preamble of the Audiovisual Media Services

- 192/193 -

Directive[4] is putting it: 'In accordance with the duties imposed on Member States by the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, they are responsible for the effective implementation of this Directive. They are free to choose the appropriate instruments according to their legal traditions and established structures, and, in particular, the form of their competent independent regulatory bodies, in order to be able to carry out their work in implementing this Directive impartially and transparently. More specifically, the instruments chosen by Member States should contribute to the promotion of media pluralism.' The emphasized importance of audiovisual regulation is ensured by the fact that the European Commission, according to the 'Copenhagen criteria', is entitled to investigate both legally binding and non-binding documents in the case of countries wishing to join the EU.

2.1. The realm of legally binding rules

The Television without Frontiers Directive[5] was adopted on 3 October 1989 following the drafting of a Green Book in 1984. The Directive took steps towards the formation of a common media market by breaking down barriers within the EU with regard to the founding principle of the four freedoms. As a main rule, all member states had to abolish any unnecessary restrictions that either legally or technically restricted the reception of broadcasters originating from the area of other member states. In addition to that, the Directive also laid down important common European rules for, among others, television advertising and sponsorship, the protection of minors and the right of reply. Due to rapid technological development the modification and refinement of the Directive became necessary in 1997. The greatest change, in my opinion, is that according to the modified Directive, broadcasters are subjects to the jurisdiction of the country of the location of their head office or the place where programming decisions are made. This regulation was aimed at putting an end to broadcasters' attempts to evade regulations and manoeuvre themselves in a more favourable position. The second revision was however more than just a cosmetic change. For the media market, by

- 193/194 -

now entirely changed both in technological and economical terms, a Directive discussing solely television broadcasting was not sufficient any longer, thus another revision of the Directive was on the agenda since the beginning of the 00's. The Directive in a consolidated structure with all amendments was discussed by the European Parliament and the Council of the EU in 2007. The new Directive, from that point bearing the title 'Audiovisual Media Services Directive' was adopted on 24 May 2007. According to the procedural rules of the EU, all member states were to incorporate the contents of the Directive into their respective legislations, but the form and rules of doing so were open for them to choose. The new Directive, stepping across classical media broadcasting structures, has now taken into consideration technological changes, and introduced the concepts of linear and non-linear audiovisual media services.[6] The aim of the Directive is to provide equal opportunities for competition for cross-border linear and non-linear audiovisual media services, and at the same time promote cultural diversity, protect minors and consumers,[7] promote the protection of the diversity of mass media, and combat incitement to hatred based on race, sex, religion or nationality. Member states were obliged to harmonize their national law with the regulations of the new Directive. The necessity of the will to promote pluralism can be found among the regulations of the Directive, but no new type of community media is mentioned in the document.

2.2. The realm of 'soft law'

In the legal system of the EU, besides 'hard law', the rules of 'soft law' are also known, and this of course applies to audiovisual regulation as well.[8] 'Soft law' includes the statements, opinions and recommendations of various European institutions, which do not have a binding legal force for member states. However, in certain instances 'soft law' might be a significant regulatory tool, first, because it might influence the change of legislation and practice in member states, and second, because there is a chance that with time, due to the change of circumstances, the parties

- 194/195 -

will transform these rules into 'hard law'. 'Soft law' solutions are usually applied in politically sensitive situations, when parties agree about the fundamental principles, but cannot come to a consensus concerning the mode of implementation or the details. In such cases, releasing a 'soft law' document provides an opportunity for laying the fundaments, and for the later (detailed) discussion of the issue.

Alternative community media, as we will see, has not yet reached the level of attention for European politicians and policy makers to have the special rules of the sector laid down in legally binding norms, but more than one 'soft law' document was released on the subject in the past couple of years. The drafting of these documents can be considered as a first initial step leading to the sector taking its deserved position on a European level.

3. Alternative community media's case with Europe

When investigating the aspect of alternative community media manifested in European regulations, we might choose the approach of investigating its relationship to various European policies (telecommunication policy, audiovisual and media policy, policies related to freedom of speech, cultural policy, policies related to equal opportunities and discrimination)[9], or we might choose to review the topic by taking the institution (of national or European scope) drafting the regulation (European Parliament, European Council, UN, OSCE, OAS, ACHPR, etc.[10]). However, from the aspect of the topic, choosing the third approach[11] seems the most appropriate, i.e. the chronological introduction, as alternative community media's emergence, albeit with stops and turns, progresses from being a marginal phenomenon to the mainstream, therefore separating relevant legislation by different institutions would not illustrate sufficiently the emergence of community media.

- 195/196 -

3.1. The beginnings

The term 'alternative community media' is entirely absent from documents drafted before the Millennium, but it is still worth investigating the most important of these documents. First, because they lay down important regulations related to fundamental rights (e.g. related to the freedom of expression), and second, because their terminology allows more recent documents to build on them and cite them to introduce and discuss alternative community media.

3.1.1. Three fundamental documents

Following World War II, on 10 December 1948, the UN General Assembly adopted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.[12] According to the famous and frequently quoted Article 19[13] 'Everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression; this right includes freedom to hold opinions without interference and to seek, receive and impart information and ideas through any media and regardless of frontiers.' The European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms[14] (CPHRFF) adopted in Rome, on 4 November 1950, discusses freedom of expression in Article 10. It is evident that each of the documents introduced below refer to the articles of the UN's fundamental documents.

The Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union[15] identified the fundamental rights of the European Union in 7 Titles and 54 Articles. The Charter complements the above mentioned European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms. Article 11, found under the title 'Freedoms' discusses the freedom of expression and information. The first paragraph is almost identical to Article 10 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, but is complemented with an

- 196/197 -

important element: among values to protect the Article mentions freedom and independence of media but also adds its diversity and pluralism.

3.1.2. The Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe comes on the scene

The Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe[16] is one of the organizations that address the situation of community media. The Council of Europe has been addressing issues related to freedom of speech, freedom of expression, and freedom of press and media from the very beginning. The Committee of Ministers has adopted a Declaration[17] at its 70th meeting on 29 April 1982, which emphasized that member states, in order to promote freedom of speech and pluralism, should aim at having as many and as diverse autonomous media actors on the media market as possible.

The Committee of Ministers has released a Recommendation[18] in 1999, recommending member states to take measures in order to promote media pluralism. Specifically, it sets the goal for the entire media market in general, and public service media in particular, to give voice to various groups and interests (language, social, economical, cultural or political minority) representing them in their portfolio. In addition, it highlights that the existence of autonomous and independent media service providers on different levels (including local, regional and national) facilitates pluralism and democracy, and explicitly states the need for state support of media actors broadcasting in minority languages.

- 197/198 -

3.2. The beginning of the 00's

It occurred for the first time at the beginning of the 00's that a world organization substantively addressed the issue and stood up for the third type of media: the Constitution of UNESCO advocates the strengthening of pluralism and the recognition of minority rights, so in relation with the organization's work it is worth briefly discussing a document that is not a legally binding one, though it promotes legal solutions. The study comparing the community radio legislations of 13 countries[19] did not aim at compiling a taxative and comprehensive list of relevant regulations, but rather just picked typical examples from all around the world, thus introducing not only European regulations (by describing the situation in Spain and Poland) but relevant legislations of the other four continents as well. For UNESCO, the topic is very much significant as these media contribute to the development of democracy, and they, 'without discrimination on the grounds of race, gender, social class, sexual orientation, disabilities or political or religious opinions, are indispensable for the promotion of social dialogues and the culture of peace'[20]

The Recommendation[21] of the Congress of Local and Regional Authorities of the Council of Europe[22] was released at around the same time, drawing member states' attention to recognizing that 'Non-profit making community media entities are recognised as a third sector supplementing the national public service and the private broadcasting sector'.[23] Even if not on a very high level, this was the first time that the term 'community

- 198/199 -

media' was used in a document of legal nature in relation to the Council of Europe. Furthermore, the Recommendation highlights that member states must pass legislation that will guarantee access to all currently known and future analogue and digital types of broadcasting opportunity for multilingual community media, promoting citizen participation in the media and the participation of individuals in democratic processes.

3.3. Community media's increasing significance in legal documents by the end of the 00's

Starting from the 90's, the recognition of participatory democracy and participatory type of media has had an increasing significance in the thinking of European and international organizations and thus in the documents released by these organizations.

3.3.1. The Media Task Force of the European Commission

In 2007, the European Commission's Directorate General for Communications Networks, Content and Technology[24] has set up a three step schedule for the Media Task Force, a body focusing on European media concentrations and their impact on media pluralism. The three steps[25] were planned as follows:

1) Publication of a Commission Staff Working Paper on Media Pluralism in the member states of the EU.

2) An independent study on media pluralism in EU Member States to define and test indicators for assessing media pluralism in the EU Member States.

3) A Commission Communication on the indicators for media pluralism in the EU Member States.

- 199/200 -

The Commission Staff Working Papers[26] were presented to the public at the same time as the three step schedule, on 16 January 2007. The plans were to publish the activities set out in step 2 in the same year (2007), while the implementation of step 3 was planned in 2008. However, deadlines were not fully met. The Commission Staff Working Paper gave a brief introduction of the audiovisual and printed press markets of the member states, and analysed the regulatory models for media ownership in all 27 member states. From the document it is clearly seen that there are vast differences between the media markets of member states. From the aspect of the community media sector, the working document represented a step back, as the relevant section analyses the dual (!) media market at great length, describing it as a market where public service media service providers work alongside and compete commercial media. So not surprisingly, the working document was criticized by many for this shortcoming.

3.3.2. A hard day's night

On 31 January 2007, the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe had a busy day: they have adopted three documents (a declaration and two recommendations) at one lengthy session. The Declaration and one of the Recommendations contained key novelties from the aspect of this paper's topic. In their Declaration[27] on protecting the role of the media in democracy in the context of media concentration, the Committee of Ministers emphasize that the Committee is conscious of the development of new communicational technologies, and the opportunities offered by alternative[28] community media. These media facilitate people's participation in democratic processes, thus in debates, the increasing of the force of the public, or the acquisition of key information of public interest. The Committee also states that member states should take positive

- 200/201 -

and active steps in order to maintain and further promote pluralism in the media, thus facilitating the development of democratic society. Therefore it calls upon member states to take steps necessary for the development of non-profit media, thus allowing access to information and expression of opinion for social groups that mainstream media relatively rarely concentrates on.

The recommendation[29] on media pluralism and diversity of media content is of no legally binding force, but is still a significant document, as it states that media pluralism and diversity of media content are essential for the functioning of a democratic society. Media makes a crucial contribution to the functioning of democracies, notably by providing different groups in society - including cultural, linguistic, ethnic, religious or other minorities - with an opportunity to receive and impart information, to express themselves and to exchange ideas. The document provides recommended measures in four great areas for member states: measures for promoting structural pluralism of media, measures promoting content diversity, media transparency and scientific research. Concerning structural pluralism, the Committee of Ministers emphasized that 'member states should encourage the development of other media capable of making a contribution to pluralism and diversity and providing a space for dialogue. These media could, for example, take the form of community, local, minority or social media. The content of such media can be created mainly, but not exclusively, by and for certain groups in society, can provide a response to their specific needs or demands, and can serve as a factor of social cohesion and integration.' Community media is mentioned once more indirectly in the document when stating that member states should take any financial and regulatory measures necessary to protect and promote structural pluralism of media.

- 201/202 -

3.3.3. The year of an important joint declaration

At the end of 2007, a joint declaration[30] on diversity of broadcasting drafted by the UN Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Opinion and Expression, the OAS Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Expression[31] and the ACHPR Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Expression acknowledged the third type of media sector in yet another document. A special feature of the document is the fact that it does not discuss a range of topics, but focuses on just one: preserving the diversity of broadcasting. The Declaration stresses the fundamental importance of diversity in the media to the free flow of information. The parties recognize that media of any type and reach contribute to the pluralism of media, that is, local, national, regional and international media as well as commercial, public service and community media. According to the Declaration, pluralism of media may manifest in three levels:

- a distinction based on outlet (types of broadcasters),

- based on source (ownership),

- based on content.

For community media, the Declaration is an important point of reference from the aspect of classification, as it is declared that community media should be legally acknowledged in all countries in the world. The issue of receiving a radio frequency as well as the financial background need to be settled. It has been recommended that community media too should be granted opportunity to have access to advertising, and that ideally, every media broadcaster should be granted the opportunity to switch from analogue to digital broadcasting, and measures must be taken to ensure that the high transition costs would not restrict community media in exploiting the opportunity to do so. The Declaration also states that different types

- 202/203 -

of broadcasters - commercial, public service and community - should be able to operate on, and have equitable access to, all available distribution platforms, which might also include specific measures such as must-carry rules or reservation of adequate frequencies for different types of broadcasters.

3.3.4. 'The state of community media in the European Union' - the European Parliament and the third sector

A study 'The state of community media in the European Union'[32] requested by the European Parliament's Committee on Culture and Education, from around the same time, reported for the first time how the diverse group of alternative media is connected to the policies of the European Union, and how they can facilitate the implementation of these policies. The document attempts to sum up the common characteristics of the sector, one that includes a very diverse and different group of community media of all European countries. It declares that this difference is due to a great extent to the legal recognition[33] of the sector and the interest of the audience/public in each of the countries. The fundamental finding of the study is that the most important task of the sector is to raise awareness of European politicians and the public. The most important result of the study is the list and analysis collecting how community media can contribute to the realization of public interest:[34]

• A Diverse Range of Societal Contributions (community media's contributions regarding public interest can be of cultural, political, social and economic nature and depend on each organisation's individual intentions and abilities)

• Media Pluralism and Diversity (community media help to strengthen media pluralism and diversity)

• Community Cohesion and Cross-Cultural-Dialogue (community media help to strengthen the identities of specific communities

- 203/204 -

of interest while at the same time enable members of those communities to engage with other groups of society)

• Social Inclusion and Local Empowerment (community media can be an effective means to enable disadvantaged members of a community to become active participants in society and to engage in debates concerning issues that are important to them)

• Media Literacy, Skills Development and Education (community media raise media literacy rates among participants as they help to demystify the process of media production. The sector has also often been the training ground for future media professionals as it provides its volunteers with the creative, practical and technical skills needed to succeed in a highly competitive media industry)

• Local Public Service Delivery (community media provide a link between local communities and local public services)

• Promotion of Local Creative Potential (community media act as a catalyst for local creativity and give resident artists and creative entrepreneurs a platform for testing new ideas and concepts with an audience)

The study concludes that of the characteristics listed above, it is very rare that all of them are realized at the same time in the case of an alternative medium, the case is usually that they concentrate on just a few of these objectives. Another important asset of the study is the map that shows the spreading of community media activities in the European Union. Hungary gained a place in the second best category due to its lively and active community media sector. It would be interesting to take a look at such a map 5-10 years later...[35]

3.3.5. The last Ligabo report

Ambeyi Ligabo, the Special Rapporteur of the UN on the right to freedom of opinion and expression, has not only published joint declarations as the one discussed in Chapter 3.3.3., but he also prepared annual reports[36]

- 204/205 -

on the situation of the right to freedom of opinion and expression in the world. In his last report in 2008,[37] he confirmed that in order to assess the realization of media pluralism, all three of the factors analysed earlier (types of media, and diversity of sources and content) should be investigated. He highlighted that the governments of some countries use the state-controlled licensing procedures for distributing radio frequencies to apply political pressure on editorial independence (point 26). However, he also declared that marginalized and vulnerable groups in society have often no access to media content, and that is a problem that governments of the world need to pay special attention to. Minorities, indigenous peoples, migrant workers, refugees and many other vulnerable communities have faced barriers, some of them insurmountable, to be able to fully exercise their right to impart information. For these groups, the media plays the central role of fostering social mobilization, participation in public life and access to information that is relevant for the community. Furthermore, the strengthening of educational and cultural content and the increase in the space given to minorities and vulnerable groups to express their views, for example, can greatly increase the quality of the media outlets themselves.

3.3.6. Strengthening of social cohesion

The Council of Europe often asks experts to elaborate topics before their discussion. This is how the analysis 'Promoting Social Cohesion: the role of community media'[38] was written in 2008 by Peter Lewis, a British expert on community media. This second such analysis, this time a comprehensive one covering 22 European countries investigated, among others, the legal status of community media, funding, and the existence of a national association representative of the sector. Following a thorough analysis, the author of the study came to the conclusion that community media has a key role in strengthening social cohesion and in promoting active citizenship. This is achieved by a receptive type of programming

- 205/206 -

giving voice to those not represented on a permanent basis by the other two actors of the media sector.

3.4. Naming the sector

By the end of the 00's, the sector has achieved that it was considered a distinct sector mentioned by their own name in the documents of European and world organizations. From the aspect of further development it is of key importance that the sector is recognized as an actor with equal rights compared to the others on European public thinking. Furthermore, we must not forget about the significance of giving/receiving a name as a more abstract, mystical phenomenon: if something has a name, then it exists. So it can be referred to, and as a result, one can step one step up on the ladder to a higher level of discussing the phenomenon.

3.4.1. The Maputo Declaration

3 May was declared as the World Press Freedom Day by the UN in 1991. At the 2008 UN conference, the Maputo Declaration,[39] a document of key importance from the aspect of community media was adopted, as that year's dedicated topics were related to the freedom of expression and information and empowerment of people. Participants of the conference discussed three key means of empowerment of individuals and communities: freedom of press, community media and access to information. Free, independent and pluralistic media empowers people to participate in democratic processes, and community media as the most readily available means of involving people. The Declaration addresses in a separate paragraph how each of the three types of media, i.e. public service, commercial and community media sectors, contribute to the realization of media pluralism, and in addition, community media has an additional role in representing otherwise underrepresented and marginalized groups. Participants of the conference finally called upon the member states to create an environment

- 206/207 -

for media in their countries which promotes the development of all three tiers of broadcasting. They highlighted that this request particularly refers to improving conditions for the development of community media and for the participation of women within the community media framework.

3.4.2. The Resetarits report

The Committee asked Karin Resetarits, an Austrian MEP to prepare a report based on the study 'The state of community media in the European Union' requested by the European Parliament's Committee on Culture and Education, discussed above. The so-called Resetarits report,[40] adopted by the Committee on 2 June 2008,[41] and submitted to the European Parliament on 24 June, 'looks for measures to support community or alternative media in Europe in order to guarantee a more pluralistic media environment, cultural diversity and to clearly define the sector as a distinct group in the media sector'.[42] The report emphasizes the community media are a distinct group alongside public service and commercial media within the media sector. It points out that while active, for community media social and cultural benefit of the society are primary concerns, the exact forms of which are listed as: they help to strengthen the identities of specific social groups, extend dialogue between cultures and increase social integration and local emancipation. Furthermore, referring back to the study, the report also emphasizes the role of community media in increasing media literacy and promoting local creative potential (artistic or entrepreneurial). It also points out that community media can be an excellent tool for the European Union to interact its own citizens, understand and address their needs.

After its adoption by the Committee, the press release of the group of MEPs Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe Group[43] captured

- 207/208 -

one of the main characteristic of this type of media as 'Alternative media [...] allow a community to integrate'.

3.4.3. The European Parliament resolution

The Resetarits report also formulated a draft for a European Parliament resolution. Based on that draft, the European Parliament adopted a resolution[44] on 25 September 2008 on Community Media in Europe. Even though again this was 'only' a resolution with no legal binding force, still it was the first time in the history of community media that one of the leading bodies of the European Union addressed the sector on its own right and not as part of the bigger media market. The resolution discusses the situation in Europe, saying that 'none of the relevant Community legal acts have yet addressed the issue of community media" (Point I.), but this statement needs to be amended to say that such legal acts have not yet addressed the issue on its own right, as an independent phenomenon.

The resolution also remarks that the diverse and colourful nature of the sector might be the reason for its playing a key role in Europe in strengthening local identity, social integration and cultural and linguistic diversity. In addition, they foster intercultural dialogue and tolerance in European citizens. The resolution highlights that community media contributes to strengthening media pluralism by improving the perception of groups in society threatened with exclusion (such as refugees, migrants, Roma and other ethnic and religious minorities); acting as a catalyst for local creativity, improving citizens' media literacy by educational and training programmes, decreasing the distance between the European Union and its citizens, and providing information about local public services. However, it cannot guarantee all of the above in proper quality without proper financial resources.

Finally, the European Parliament came up with four important recommendations. First, it advised Member States, without causing detriment to traditional media, to give legal recognition to community

- 208/209 -

media as a distinct group alongside commercial and public media where such recognition is still lacking. Second, it called on Member States to make television and radio frequency spectrum available, both analogue and digital, bearing in mind that the service provided by community media is not to be assessed in terms of opportunity cost or justification of the cost of spectrum allocation but rather in the social value it represents. Third, it called on Member States to support community media more actively in order to ensure media pluralism. In addition to these three suggestions, the European Parliament called on the Commission to take into account the added value represented by community media when designing indicators for media pluralism.

3.4.4. The Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe

2008 was a busy year from the aspect of media pluralism. The Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe has adopted two documents on the topic at its 36th sitting on 3 October 2008. Officially, neither the resolution nor the recommendation have legally binding force for member states.[45] According to point 8.18 of the Resolution 1636 (2008)1,[46] national legislative bodies should take concrete positive actions in order to promote media pluralism. Recommendation 1848 (2008)1[47] recommended the Council of Europe to establish indicators for a functioning media environment in a democracy, and draw up periodical reports with country profiles of all member states concerning their media situations.

- 209/210 -

3.4.5. The Committee of Ministers also acknowledges the sector by its own name

By the end of the 00's, the sector got its 'own' documents, in which it is mentioned not just as an actor of peripheral role in the entire big media system, but as a distinct sector having its own specific characteristics. The aforementioned study by Lewis 'Promoting Social Cohesion: the role of community media' has proved to be the antecedent of such a document: on 11 February 2009, the Council of Europe Committee of Ministers 'awarded' the free media sector a Declaration dedicated to the sector solely, titled The role of community media in promoting social cohesion and intercultural dialogue'.[48]

The Committee of Ministers stated that community media is complementary to the other two (commercial and public service) media sectors, noting that community media operate in many Council of Europe member states and in over 115 countries worldwide. It acknowledges that community media significantly contributes to fostering public debate, political pluralism and awareness of diverse opinions by providing various groups in society -including cultural, linguistic, ethnic, religious or other minorities - with an opportunity to receive and impart information, to express themselves and to exchange ideas. According to the Declaration, the Committee was conscious that in today's radically changed media landscape, community media can play an important role, notably by promoting social cohesion, intercultural dialogue and tolerance, as well as by fostering community engagement and democratic participation at local and regional level. The Declaration once more confirmed that community media contributes to developing media literacy through the direct involvement of citizens in the process of creation of media content, as well as through the organisation of training programmes.

For the above reasons, the Council of Europe Committee of Ministers declared its support for community media. In relation to that, it recognised community media as a distinct media sector, and drew attention to the

- 210/211 -

desirability of allocating to community media a sufficient number of frequencies, both in analogue and digital environments; and called upon the member states to recognise the social value of community media and examine the possibility of committing funds at national, regional and local level to support the sector, while duly taking into account competition aspects.

3.4.6. Independent report about the indicators of media pluralism

As seen before, the 2007 preparatory work paper of the European Commission about media pluralism did not identify community media as the third actor of media market. The second step of the Media Task Force was accomplished somewhat later than planned, by 2009, when the final report of the group consisting of three higher education institutes and a consultant agency was complete. The document titled 'Independent Study on Indicators for Media Pluralism in the Member States - Towards a Risk-Based Approach'[49] redresses the mistake committed against community media, and names it as an important actor of plural media market. It already states in the introduction that all types of media - public service, commercial and community media - play important roles in creating pluralism and that the presence of all of them are important to be able to talk about pluralism.

However, the report adds that the realization of pluralism greatly depends on the structure and state of media environment in member states, in particular on how its key elements are related to one another. As an example, the report mentions the relation of public service, commercial and community media, and mainstream and minority media to one another. Community media is again a key actor in this respect too, as it is able to offer an alternative/alternatives to the audience. However, even according to the authors of the report, the fulfilling of this task in practice and the functioning of this type of media depends to a large extent on governmental media policy regulation, subsidies and control.

- 211/212 -

The report discusses the absence or insufficiency of minority and community media as a threat and risk for the entire media market, considering the absence or insufficiency of public support[50] a related issue. A quantitative indicator for this issue could be the number of such media, the number of analogue and digital frequencies provided to them, or the sum of subsidies. As qualitative indicators, one might examine the sustainability of investment and sum of subsidies.

Concerning the legal indicators for the field,[51] a two direction research can be performed in member states: first, to the existence of such legal regulation (A), and second, to the utilization of legal regulation (B). The document discusses the following issues:

(A.) How to check the existence (E) of such safeguards:

| YES | NO | |

| E.1. Does the media law contain specific provisions on minority and community media (granting legal recognition to such media as a distinct group alongside commercial and public media)? | + | - |

| E.2. Are frequencies reserved for minority and community media? | + | - |

| E.3. Does the media legislation ensure access by regional and/or local media to platforms of electronic communication network providers (in particular, via must carry rules)? | + | - |

| E.4. Does the State, regional and/or local authority actively support minority and community media through direct or indirect subsidies or other policy measures? | + | - |

- 212/213 -

(B.) How to check the effective implementation (I) of such safeguards:

| YES | NO | |

| I.1. Was this specific regulation designed in close collaboration with the minority or community it is destined for? | + | - |

| I.2. Is this regulation sufficient (transparent, well-known within the minority community) to stimulate minority or community media to surface? | + | - |

| I.3 Does this regulatory framework guarantee independence of the minority or community media, meaning that they are de facto owned by or accountable to the community or the minority that they seek to serve (e.g. they can elect their own board/management bodies)? | + | - |

| I.4. Are these media de facto open to participation (both in programme making and management)? | + | - |

| I.5. Is there an administrative or judicial body actively monitoring compliance with these rules and/or hearing complaints and Is this supervision over these media done in an objective way? | + | - |

| I.6. Does the law grant that body effective sanctioning/ enforcement powers in order to impose proportionate remedies in case of non- compliance with the rules? | + | - |

| I.7. Are there effective appeal mechanisms in place: | ||

| - before a judicial body or if not, before a body that is independent of the parties involved, held to provide written reasons for its decisions and whose decisions are subject to review by a court or tribunal within the meaning of Article 234 EC Treaty, | ||

| - the procedures of which are not systematically misused to delay the enforcement of remedies? | + | - |

| I.8. Is there evidence - in case law, decision practice, press reports, reports of independent bodies or NGOs... - of systematic political censorship, interference or manipulation of these media? | + | - |

3.5. The developments of the past years

3.5.1. The Tenth Anniversary joint declaration by UN-OSCE-OAS-ACHPR

On 2 February 2010, the UN Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Opinion and Expression, the OSCE Representative on Freedom of the Media, the OAS Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Expression and the ACHPR

- 213/214 -

Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Expression and Access to Information met in the capital of the USA in order to discuss and draft a tenth anniversary joint declaration. Due to the festive event, the Declaration exceptionally discussed the future too. The document, titled 'Ten key challenges to freedom of expression in the next decade'[52] was publicized the next day, on 3 February 2010.

Though each of the ten points of the Declaration is of significance for media researchers and the public, from the aspect of community media, Points 5 and 7 are of special significance. In Point 5, the threat of discrimination is discussed which deprives historically disadvantaged groups (such as women, minorities, refugees, indigenous peoples and sexual minorities) from equal enjoyment of the right to freedom of expression. It is important that these groups make their voice heard and have access to all information relevant to them in all societies in the world. Point 7 discusses support for public service and community broadcasters. The Declaration emphasizes the significance of these two sectors in supplementing the content provided by commercial broadcasters, thereby contributing to diversity and satisfying the public's information needs. The authors are particularly concerned about the lack of legal recognition of the community broadcasting sector and the failure to reserve adequate frequencies for community broadcasters or to establish appropriate funding support mechanisms.

3.5.2. The 2010 La Rue report

About a month after the tenth anniversary joint Declaration, Frank William La Rue of Guatemala, the UN Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Opinion and Expression completed his annual report.[53] The report specifically[54] addresses the worldwide problem of people living in poverty finding it difficult to make their voices heard, as their circumstances prevent them from exercising their rights on this area (among many others). The author

- 214/215 -

highlights that by exercising the right to freedom of speech, these groups can obtain information, and participate in the (political) decisions that aim at improving their situation. An excellent tool for doing so is community based media.[55] This type of media provides an opportunity for minorities and groups excluded from communication to exercise their rights to communication. Therefore, it is the duty of Governments to assist and support the sector. The closing conclusions and recommendations call upon the world's governments to legally acknowledge community media, an effective instrument[56] for ensuring the exercise of the right to freedom of opinion and expression, and to find a balance in terms of frequency allocation among the three types of media in the media market.[57]

3.5.3. The new concept of media

The Recommendation by the European Commission on 21 September 2011 on the changed media situation has also had an impact on European media policy. According to the Commission,[58] media is capable of providing an opportunity for people to exercise their right to freedom of speech, thus allowing them to become active members of democracy, and to participate in decision making processes which concern them. However, despite the appearance of new actors in the media market, the change in communication in many respects, or the complete change of the concept of media due to technological development in the past few years, the role of media in democratic societies has not changed fundamentally, but is just expanded with new elements (such as interaction or engagement). The Commission recommended member states to review legal solutions with both old and new actors of the media market, in order to be able to guarantee the right for the exercise of freedom of speech in its entirety to all members of the society. The annex of the Recommendation states that there is no genuine democracy without independent media, and that all three actors of the media market (community, public service and

- 215/216 -

commercial media) are of key importance in the European media model.[59] It highlights that - not counting some exceptional cases - distribution of frequencies should be done with respect to public interest, that is, the existence of independent and diverse media should be guaranteed.

3.5.4. The digital agenda

The third step of the Media Task Force plan: the publication of a Commission Communication about media pluralism indicators in European member states, even though its realization was planned for 2008, has still not happened. In connection with that, in the autumn of 2011, in the framework of the European Commission's digital agenda[60] Neelie Kroes vice-president has made two announcements on the topic of media pluralism. First, the first meeting of the High-Level Group on Media Freedom and Pluralism[61], the mandate of which was to draw up recommendations for the respect, protection, support and promotion of pluralism and freedom of the media in Europe, was held on 11 October 2011.[62] Second: The European Commission gave a 600,000 EUR funding to the European University Institute (EUI) Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies[63] and created a centre for media pluralism and freedom of media. The goal of the Centre is, that with Professor Pier Luigi Parcu[64] as their director, to stimulate and renew the European discourse about media pluralism, and based on existing documents, prepare indicators for media pluralism.

- 216/217 -

4. Summary

Community/alternative media might become a tool for realizing a democratic, diverse media market in Europe as well as in other parts of the world. Community Media Forum Europe has published[65] the first Europe-wide survey about the community type of media at the end of October 2012, that made the weight and significance of the sector clear to everyone: in the beginning of November 2012 there were 2237 community radios and 521 community televisions in Europe.[66] In 2012, EPRA has set up a permanent working group[67] for community media, and at its second meeting held between 28-30 November in Jerusalem, Israel, Hungary was represented by the chair of the National Media and Infocommunications Authority[68] in the 'Local and Community Media' working group.[69] AMARC-Europe in its Budapest Declaration[70] on 13 November 2012 highlighted that the governments of Central-East Europe should finally acknowledge community media sector and adopt the relevant special regulations in their legal systems. The same organisation in its Montpellier Declaration[71] one year later requested the European states to guarantee access for community media to all available broadcasting platforms, so that the shift from analogue to digital technologies would become an opportunity for more media pluralism rather than for further media concentration.

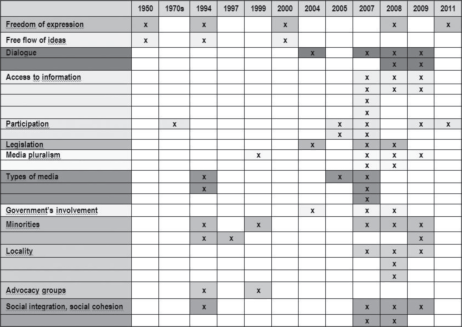

If we analyse the keywords in the documents which were presented in this article, we could easily see how those documents deal with more and more

- 217/218 -

relevant topics of the media pluralism. Started in the 1950s with freedom of expression and free flow of ideas solely, it became broader in the 1990s with the keywords of locality, minorities and social integration. After that in the early 2000s the politicians and European law-makers realised more and more important characteristics of the third type media such as creating field for dialogue, giving access to information and strenghtening participation. This table[72] - as a novum of the researches dealing with the alternative media - shows what could be the future ways of researches of community media and its relation to media pluralism.

As a conclusion we could say that it seems that the diversity and pluralism of media and the existence of third type of media services in democratic media markets is a very relevant issue today, and this is reflected in a growing number of legal and other media regulatory documents of legal nature in the past few years.

- 218/219 -

Annex 1.

| 1948 | 1950 | mid 1970s | late 1970s | 1982 | 1983 | 1986 | 1989 | 1991-1992 | 1994 |

| World | Europe | Europe | Europe | Europe | World | Europe | Europe | Hungary | Europe |

| UN | European Council | university, school radios | local community radios | Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe | AMARC | FERL | TWF | Tilos Radio, Fiksz Radio, Hungarian Federation of Free Radios | AMARC-Europe |

| Universal Declaration of Human Rights | The European Convention on Human Rights | declaration | The Community Radio Charter for Europe |

| 1996 | 1997 | 1999 | 2000 | 2004 | 2005 | 2007 | 2007 | 2007 | 2007 |

| Hungary | Europe | Europe | Europe | Europe | Europe | Europe | Europe | Europe | Europe |

| Parliament | Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe | Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe | European Council | CMFE | Congress of Local and Regional Authorities of the Council of Europe | European Commission Media Task Force | Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe | Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe | AMS |

| Act I of 1996 on Radio and Television | recommendation | recommendation | Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union | recommendation | working document | declaration | recommendation |

- 219/220 -

| 2007 | 2007 | 2008 | 2008 | 2008 | 2008 | 2008 | 2008 | 2008 | 2008 |

| World | Europe | World | World | World | Europe | Europe | Europe | Europe | Europe |

| UN, OSCE, OAS, ACHPR | European Parliament's Committee on Culture and Education | AMARC | UN | UNESCO | European Parliament's Committee on Culture and Education | European Parliament | European Parliament | Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe | Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe |

| joint declaration | The state of community media in the European Union | The Montreal Declaration | Ligabo- report | Maputo declaration | Resetarits- report | resolution 1 | resolution 2 | resolution | recommendation |

| 2009 | 2009 | 2010 | 2010 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | |

| Europe | Europe | World | World | Hungary | Europe | World | |

| Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe | European Commission Media Task Force | UN, OSCE, OAS, ACHPR | UN | Parliament | Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe | UN | ... |

| declaration | study | joint declaration | report | Act CLXXXV of 2010 on Media Services and Mass Media | Recommendation | report | ... |

- 220/221 -

Literature

Bailey, Olga Guedes - Cammaerts, Bart - Carpentier, Nico: Understanding alternative media. Open University Press, Berkshire, 2008

Buckley, Steve - Duer, Kreszentia - Mendel, Toby - Siochrú, Seán Ó - Price, Monroe E. - Raboy, Mark: Broadcasting, Voice and Accountability: A Public Interest Approach to Policy, Law and Regulation. The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development, The World Bank Group, 2008

Cammaerts, Bart: Community Radio in the West: A Legacy of Struggle for Survival in a State and Capitalist Controlled Media Environment. International Communication Gazette, (71:8), 2009, 635-654.

Carpentier, Nico - Scifo, Salvatore: Introduction: Community media's long march. Telematics and Informatics, (27:2), 2010, 115-118.

Carpentier, Nico: Media and Participation. A site of ideological-democratic struggle. Intellect Books, Bristol, 2011

Craufurd Smith, Rachael: Az audiovizuális médiaszolgáltatásokra vonatkozó szabályozói hatáskör meghatározása az Európai Unióban. ('The determination of regulatory powers on audiovisual media services in the European Union') In Medias Res, (1:1), 2012, 15-36.

Czepek, Andrea - Hellwig, Melanie - Nowak, Eva (ed.): Press Freedom and Pluralism in Europe. Concepts and Conditions. ECREA Book Series, Intellect Books, Bristol, 2009

Doliwa, Urszula - Rankovic, Larisa: Time for community media in Central and Eastern Europe. Central European Journal of Communication, (7:1), 2014 (under publication)

Downey, John - Mihelj, Sabina (ed.): Central and Eastern European Media in Comparative Perspective. Ashgate, Farnham, 2012

Fuller, Linda (ed.): The power of global community media. Palgrave Macmillan, New York, 2012

Gordon, Janey (ed.): Community Radio in the Twenty-First Century. Peter Lang Publications, Oxford, 2012

Gosztonyi Gergely: Az Európa Tanács Miniszteri Bizottsága és a közösségi média újfajta magyar szabályozása. ('The Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe and a new kind of Hungarian regulation of community media') Civil Fórum, (12:1), 2011, 7-9.

Gosztonyi Gergely: Past, Present and Future of the Hungarian Community Radio Movement. In: Howley, Kevin (ed.): Understanding community media. Sage Publications Ltd., London, 2009, 297-308.

Hitchens, Lesley: Broadcasting Pluralism and Diversity: A Comparative Study of Policy and Regulation. Oxford and Portland, Oregon, Hart Publishing, 2006

Howley, Kevin (ed.): Understanding community media. Sage Publications Ltd., London, 2009

Jakubowicz, Karol - Sükösd Miklós (ed.): Finding the right place on the map. Central and Easter European media change in a global perspective. ECREA Book Series, Intellect Books, Bristol, 2008

- 221/222 -

Kaplan, Andreas M. - Haenlein, Michael: Users of the world, unite! The challenges and opportunities of Social Media. Business Horizons, (53:1), 2010, 59-68.

Kende Tamás - Szűcs Tamás - Jeney Petra (ed.): Európai közjog és politika. ('European public law and politics') Complex, Budapest, 2007

Klimkiewicz, Beata (ed.): Media Freedom and Pluralism. Media Policy Challenges in the Enlarged Europe. Central European University Press, New York-Budapest, 2010

Lewis, Peter M.: Promoting Social Cohesion: the role of community media. Report prepared for the Council of Europe's Group of Specialists on Media Diversity (MC-S-MD), 2008

Mac Síthigh, Daithí: Death of a Convention: Competition between the Council of Europe and European Union in the Regulation of Broadcasting. Journal of Media Law, (5:1), 2013, 133-155.

Peissl, Helmut - Tremetzberger, Otto: Community media in Europe: the legal and economic framework of the third audiovisual sector in UK, Netherlands, Switzerland, Niedersachsen (Germany) and Ireland. Telematics and Informatics, (27:2), 2010, 122130.

Polyák Gábor: Pluralizmus és médiaszabályozás. ('Pluralism and media regulation') Jogtudományi Közlöny, (64:5), 2009, 208-219.

Puppis, Manuel: Media Regulation in Small States. International Communication Gazette, (71:1-2), 2009, 7-17.

Reguero Jiménez, Núria - Sanmartín Navarro, Julián: Community Media in EU Communication Policies (2004-2008). Observatorio Journal, (3:2), 2009, 186-199.

Reguero Jiménez, Núria - Scifo, Salvatore: Community media in the context of European media policies. Telematics and Informatics, (27:2), 2010, 131-140.

Saeed, Saima: Negotiating power: community media, democracy, and the public sphere. Development in Practice, (19:4-5), 2009, 466 - 478.

Scarone Azzi, Marcello - Sánchez, Gloria Cecilia: Legislation on community radio broadcasting: comparative study of the legislation of 13 countries. Division for Freedom of Expression, Democracy and Peace Communication and Information Sector, UNESCO, Paris, 2003

Velics Gabriella: The changing situation of Hungarian community radio. In: Gordon, Janey (ed.): Community Radio in the Twenty-First Century. Peter Lang AG, International Academic Publishers, Bern, 2012, 265-281.

Ward, David: The European Union Democratic Deficit and the Public Sphere: An Evaluation of EU Media Policy. IOS Press, Amsterdam, 2002

- 222/223 -

Summary - Alternative Media in the European Media Regulation

We have seen the development of four major media service provider's model during the development of the media. The first two models appeared in Europe and in the United States of America in different orders: whereas in the USA the model of the commercial media services was the first to appear, on the Old Continent, the public service media was first introduced to the general public. One of the two remaining models is the propagandatype media service, which is characteristic, according to literature, for dictatorial communities and the other one is the alternative, community media service. The propaganda model has by now disappeared from the range of media services in Europe, and the threefold model combining the public service, commercial and community media is prevailing, which is also referred to as the "3K" model based on the Hungarian abbreviations.

The purpose of the study is to present the development of European legislation governing the alternative, so called "community media". Although the alternative, community media has not yet reached the threshold to stimulate the European professional politics and high politics to lay down the special rules for the sector in legally binding norms, several "soft law" documents have been created on the issue in recent years. The creation of these documents may be regarded as the first, initial step on the road to granting the sector a due and proper status on European level as well.

- 223/224 -

Resümee - Die alternativen Medien in der Europäischen Medienregulierung

Bei der Medienentwicklung konnten wir bislang die Entstehung von vier großen Medienvertriebsmodellen beobachten. Die Reihenfolge der Herausbildung der ersten beiden Modelle weicht in Europa und in den Vereinigten Staaten ab: Während sich in den USA zuerst das Modell des Medienvertriebs auf der Grundlage von Privatgesellschaften herausbildete, konnte das Publikum auf dem alten Kontinent zuerst die öffentlich-rechtlichen Medien kennen lernen. Von den anderen beiden Modellen ist das erste der Medienvertrieb mit Propagandacharakter, der der Fachliteratur zufolge für diktatorische Systeme gilt, das zweite Modell der alternative Medienvertrieb auf Gemeinschaftsbasis. Das Propaganda-Modell ist heute von der europäischen Medienpalette verschwunden, sodass das sogenannte 3K-Modell zur Geltung kommt, das durch das Triumvirat der öffentlich-rechtlichen, privaten und sozialen Medien gekennzeichnet ist.

Die Studie hat sich die Vorstellung der Entwicklung der europäischen rechtlichen Regelung in Bezug auf soziale, alternative Medien zum Ziel gesetzt. Zwar haben die alternativen, sozialen Medien die Reizschwelle der europäischen Fach- und Großpolitik bis heute nicht in einem Maße erreicht, dass sich diese mit den speziellen Vorschriften des Sektors in Form von rechtlich bindenden Normen beschäftigen, aber es sind in den vergangenen Jahren mehrere "Soft Law"-Dokumente in diesem Kreis entstanden. Die Entstehung dieser Dokumente kann als erster Schritt angesehen werden, der dazu führen kann, dass der Sektor auch auf europäischer Ebene den ihm gebührenden Platz einnimmt. ■

NOTES

[1] The first version of this article was published in Hungarian in In Medias Res 2013/1, p. 133-152.

[2] http://index.hu/kultur/media/2012/07/24/csak_egy_kor_maradt_a_kozmediabol/ [Downloaded on 10 November 2012]

[3] Ágnes Urban: Hol lehet lájkolni ifjabb Knézyt? ('Where could I 'like' Knézy Jr.?') In: Mérték blog, 2012, http://mertek.hvg.hu/2012/07/31/hol-lehet-lajkolni-ifjabb-knezyt/ [Downloaded on 10 November 2012].

[4] Audiovisual Media Services Directive (AMS), HL L 095, 15/04/2010 0001 - p. 0024.

[5] Television without Frontiers Directive (TVWF), HL L 298, 17/10/1989 0023 - p. 0030.

[6] AMS (11) paragraph of pre-amble.

[7] AMS (5) paragraph of pre-amble.

[8] Tamás Kende - Tamás Szűcs- Petra Jeney (ed.), 'Európai közjog és politika". ('European public law and politics') Complex, Budapest, 2007.

[9] The 2007 document 'The state of community media in the European Union' is taking steps to investigate in this direction (see sub-chapter 3.3.4. of this paper).

[10] Such as Reguero Jiménez, Núria - Sanmartín Navarro, Julián: 'Community Media in EU Communication Policies (2004-2008)'. Observatorio Journal, (3:2), 2009, 186-199.

[11] Annex 1 of this article shows the most important documents in table format, too.

[12] General Assembly resolution 217 A (III), Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

[13] http://www.un.org/en/documents/udhr/index.shtml#a19 [Downloaded on 10 November 2012].

[14] CETS No.: 005, Convention for the protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms, http://conventions.coe.int/treaty/en/treaties/html/005.htm [Downloaded on 10 November 2012].

[15] HL 2007/C 303/01, http://eur-lex.europa.eu/hu/treaties/dat/32007X1214/htm/C2007303HU.01000101.htm.

[16] The Committee of Ministers is the decision-making body of the Council of Europe, consisting of (currently) the foreign ministers of 47 member states, or their permanent diplomatic representatives in Strasbourg. The foreign ministers meet at least twice a year to review the problems of European cooperation and provide the necessary political background for the activity of the Council of Europe. The permanent representatives of ministers have the same decision making power as ministers, and they supervise the functioning of the Council of Europe. http://www.coe.int/.

[17] Declaration on freedom of expression and information, http://www.coe.int/t/dghl/standardsetting/media/Doc/CM/Dec%281982%29FreedomExpr_en.asp#TopOfPage [Downloaded on 10 November 2012].

[18] Recommendation No. R (99) 1 on measures to promote media pluralism, https://wcd.coe.int/ViewDoc.jsp?id=399303&Site=CM&BackColorInternet=9999CC&BackColorIntranet=FFBB55&BackColorLogged=FFAC75 [Downloaded on 10 November 2012].

[19] Scarone Azzi, Marcello - Sanchez, Gloria Cecilia, 'Legislation on community radio broadcasting: comparative study of the legislation of 13 countries. Division for Freedom of Expression, Democracy and Peace Communication and Information Sector', UNESCO, Paris, 2003, http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0013/001309/130970e.pdf [Downloaded on 10 November 2012].

[20] The message of Federico Mayor, p. 6.

[21] Recommendation 173 (2005)1 on regional media and transfrontier co-operation, https://wcd.coe.int/ViewDoc.jsp?id=866605&Site=Congress&BackColorInternet=C3C3C3&BackColorIntranet=CACC9A&BackColorLogged=EFEA9C [Downloaded on 10 November 2012].

[22] The main task of the Congress is to develop local and regional democracy, and strengthen the self government of local governments.

[23] 'Non-profit making community media entities are recognised as a third sector supplementing the national public service and the private broadcasting sector."

[24] European Commission's Directorate General for Communications Networks, Content and Technology (DG CONNECT).

[25] http://europa.eu/rapid/pressReleasesAction.do?reference=IP/07/52&format=HTML&aged=1&language=HU&guiLanguage=hu [Downloaded on 10 November 2012].

[26] (SEC(2007) 32), http://ec.europa.eu/information_society/media_taskforce/doc/pluralism/media_pluralism_swp_en.pdf [Downloaded on 10 November 2012].

[27] Declaration of the Committee of Ministers on protecting the role of the media in democracy in the context of media concentration, https://wcd.coe.int/ViewDoc.jsp?id=1089615&BackColorInternet=9999CC&BackColorIntranet=FFBB55&BackColorLogged=FFAC75 [Downloaded on 10 November 2012].

[28] An interesting feature of the document is that this is the first time that the term 'alternative media' appears in a European Union document.

[29] Recommendation Rec(2007)2 of the Committee of Ministers to member states on media pluralism and diversity of media content, https://wcd.coe.int/ViewDoc.jsp?id=1089699&BackColorInternet=9999CC&BackColorIntranet=FFBB55&BackColorLogged=FFAC75 [Downloaded on 10 November 2012].

[30] Joint Declaration by the UN Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Opinion and Expression, the OSCE Representative on Freedom of the Media, the OAS Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Expression and the ACHPR Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Expression, http://www.article19.org/data/files/pdfs/igo-documents/mandates-broadcasting.pdf [Downloaded on 10 November 2012].

[31] Between 2004-2010 this position was occupied by the Hungarian Miklós Haraszti, a former opposition and subsequently SZDSZ politician and publicist: http://www.osce.org/fom/43206 [Downloaded on 10 November 2012].

[32] The official text: http://www.europarl.europa.eu/committees/en/studiesdownload.html7languageDocument=EN&file=22408 [Downloaded on 10 November 2012].

[33] The study mentions Hungary on page iv. as a positive example for the legal regulation of community media.

[34] The state of community media in the European Union, Chapter 2.2.

[35] AMARC-Europe has initiated negotiations with the European Parliament's Committee for Education and culture at the end of 2012 in order to update the member state data in the study.

[36] http://www.ohchr.org/EN/Issues/FreedomOpinion/Pages/Annual.aspx [Downloaded on 10 November 2012].

[37] http://daccess-ods.un.org/TMP/5069594.97928619.html [Downloaded on 22 October 2013].

[38] Lewis, Peter M.: Promoting Social Cohesion: the role of community media. Report prepared for the Council of Europe's Group of Specialists on Media Diversity (MC-S-MD), 2008, http://www.coe.int/t/dghl/standardsetting/media/Doc/H-Inf(2008)013_en.pdf [Downloaded on 10 November 2012].

[39] The 2008 conference was held in Maputo, Mozambique. The official text of the Declaration is available at: http://www.unesco.org/new/en/unesco/events/prizes-and-celebrations/celebrations/international-days/world-press-freedom-day/previous-celebrations/worldpressfreedomday2009001/maputo-declaration/ [Downloaded on 22 October 2013].

[40] http://www.europarl.europa.eu/sides/getDoc.do7pubRef=-//EP//TEXT+REPORT+A6-2008-0263+0+DOC+XML+V0//HU [Downloaded on 10 November 2012].

[41] An interesting fact of Hungarian relevance about the report is that at the final voting at the Committee, where the report was accepted by 20 'yes' votes against 1 'no' vote, Hungarian MEP Pal Schmitt was one of the voting MEPs, with Hungarian MEP Gyula Hegyi as substitute member.

[42] Explanatory statement 1.

[43] http://www.alde.eu/fr/archive-6th-legislature-2004-2009/details/article/alternative-and-community-media-are-vital-for-social-integration-9579/ [Downloaded on 10 November 2012].

[44] http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:C:2010:008E:0075:0079:EN:PDF [Downloaded on 10 November 2012].

[45] Besides Resolutions and Recommendations, the type of document most frequently adopted by the Assembly is Opinion.

[46] Resolution 1636 (2008)1 Indicators for media in a democracy, http://assembly.coe.int/ASP/Doc/XrefViewHTML.asp?FileID=17684&Language=EN [Downloaded on 10 November 2012].

[47] Recommendation 1848 (2008)1 Indicators for media in a democracy, http://assembly.coe.int/ASP/Doc/XrefViewHTML.asp?FileID=17685&Language=EN [Downloaded on 10 November 2012].

[48] Declaration of the Committee of Ministers on the role of community media in promoting social cohesion and intercultural dialogue, https://wcd.coe.int/ViewDoc.jsp?id=1409919 [Downloaded on 10 November 2012].

[49] Independent Study on Indicators for Media Pluralism in the Member States - Towards a Risk-Based Approach, http://ec.europa.eu/information_society/media_taskforce/pluralism/study/index_en.htm [Downloaded on 10 November 2012].

[50] 5.2.4.2., p. 62.

[51] C8.10., p. 294.

[52] Tenth anniversary joint declaration on key challenges to freedom of expression in the next decade, http://www.osce.org/fom/41439 [Downloaded on 10 November 2012].

[53] http://www2.ohchr.org/english/bodies/hrcouncil/docs/14session/A.HRC.14.23.pdf [Downloaded on 10 November 2012].

[54] Points 55-58.

[55] Points 66-70.

[56] Point 109.

[57] Point 122.

[58] Recommendation CM/Rec(2011)7 on a new notion of media, https://wcd.coe.int/ViewDoc.jsp?Ref=CM/Rec%282011%297&Language=lanEnglish&Ver=original&BackColorInternet=C3C3C3&BackColorIntranet=EDB021&BackColorLogged=F5D383 [Downloaded on 10 November 2012].

[59] Point 81.

[60] Digital Agenda for Europe, http://ec.europa.eu/information_society/digital-agenda/index_en.htm [Downloaded on 10 November 2012].

[61] High-Level Group on Media Freedom and Pluralism, http://ec.europa.eu/information_society/media_taskforce/pluralism/hlg/index_en.htm [Downloaded on 10 November 2012].

[62] A significant factor for creating the Group was the European debate concerning the Hungarian media law in 2010.

[63] http://www.eui.eu/DepartmentsAndCentres/RobertSchumanCentre/Index.aspx [Downloaded on 10 November 2012].

[64] http://www.eui.eu/departmentsandcentres/robertschumancentre/people/academicstaff/parcu.aspx [Downloaded on 10 November 2012].

[65] http://www.cmfe.eu/policy/first-mapping-of-community-media-in-europe [Downloaded on 19 November 2012].

[66] See Annex 3 of the document, https://docs.google.com/spreadsheet/pub?key=0AvZa5iTe_EmWdGNiRFhqRnJaa2c3NXRhNXpSZUhkQmc&single=true&gid=0&output=html [Downloaded on 19 November 2012].

[67] http://epra3-production.s3.amazonaws.com/attachments/files/1903/original/ANNUALWORK_PROGRAMME_2012_FINAL_EN.pdf?1329126889 [Downloaded on 19 November 2012].

[69] Row 60.: http://epra3-production.s3.amazonaws.com/attachments/files/2051/original/provisional%20participation%20list%20for%20the%20website.pdf?1352799678 [Downloaded on 19 November 2012].

[70] http://www2.amarc.org/?q=node/940 [Downloaded on 19 November 2012].

[71] http://www.amarceurope.eu/declaration-of-montpellier-france-may-18-2013/ [Downloaded on 20 June 2013].

[72] A coloured version of the table could be downloaded from http://href.hu/x/lbk3.