Klára Kerezsi[1]: Alternative Sanctions: Rehabilitation, Deserved Punishment, Decreasing of Crime (Annales, 2005., 229-280. o.)

Proportionality is not always linear.

Like every human action the implementation of sanctions is also an activity that tends to produce some effect. But as soon as we begin to analyse the content of this effect, the meaning of this obvious statement is not so clear any more, because immediately a number of questions arise:

What kind of effect do we expect from the application of criminal sanctions: should it decrease criminal activity in general or should it, suited to the perpetrator's personality, keep him/her from committing the next crime? Should it retain others, or should it only punish the perpetrator in proportion with the seriousness of the offence committed? Should the effect of the sanction be perceived on the short or on the long term? Should it affront the perpetrator, should it awaken remorse, or is it enough if it leads to self-examination? Should it send out a message that social control is actually working, or is it to be acknowledged that it only serves to discipline certain groups of society?

From what do we expect these results: from punishments only, or a similar effect is expected from measures of criminal law, or perhaps from diversion? Do we expect this effect to come only from the criminal sanction applied, or does the whole vertical of the justice system belong here? And, if yes, is it only the court phase or also the investigation phase? How do we evaluate the functioning of the institutional system that is negative, slow, prolongs the procedure? How do we account for unregistered criminal activity, or criminal activity that is not known by the authorities, or this has no effect whatsoever on punishments?

How do we measure this effect: with the intensity of decrease, or do we expect that another crime shall not be committed at all? If the punished does commit a crime, do we consider the sanction to have worked if the latter offence is less serious, or if a longer period of time passes between the commit-

- 229/230 -

ting of the two offences? Is it sufficient for only the majority to agree with the application of the punishment, or do we wish to involve the offender in order to maximise the effect?

What is the role of the victim in the process of imposing punishment? Is the punishment more effective based on an interpersonal relationship or based on state power? To what extent are the interests of the victim to be taken into consideration by the application of a sanction?

Crime control can assign different roles to the reinforcement of law and punishment. Reprisal is one of the oldest objectives, in which the idea is expressed that society disapproves of the act committed, and the punishment re-establishes the balance lost by the committing of the offence. The purpose of neutralization seems most simple: if we close up people that commit crimes higher than the average, then a smaller number of offenders endanger the others. The realization of selective neutralization is more complicated than it may first seem: the record of the offender is not the best indicator of the actual behaviour, as the offender is not found at all in many cases; furthermore, the crime itself remains latent many times. Incapacitation is a mechanical process, whereas determent builds upon the ability of the punishment to change the behaviour of the potential offender. Crime control based on deterrence wishes to influence this process of decision-making, it is therefore important that its possible consequence is clear and known. This aim is rooted in medieval time: the hanged body on the gallows was a spectacular illustration of the consequences of crime. However, problems with the spectators of executions existed in Dickens' times: "it seemed much more a mass entertainment, than a participation in somebody's suffering for committing his crime. ... When John Holloway was executed in 1807, 45 thousand people were gathered. Twenty-seven people were trampled on or killed in the crowd; more than a hundred people were injured. Railway companies recruited travellers with cheaper fares to the execution's location."[1]

1. Why and how we punish?

The nature of punishment, the fundament of the punishment practice has been an area of concern not only for philosophers, but also for criminal lawyers and criminologists. The question has been dealt with by numerous foreign and Hungarian social scientists; I shall therefore rely upon their statements and scientific data, when examining the historical changes in the social function of punishment in order to highlight and uncover the new role and function of alternative sanctions.

- 230/231 -

The utilitarian approach to punishment surfaced with the Enlightenment. "The punishment of criminals should be useful. A hanged man is good for nothing -a man sentenced to public labour provides a benefit for his country on the one hand, and also serves as a living example" - claimed Voltaire.[2] Punishment is a social necessity - said Durkheim. It serves to maintain moral order, and to defend it, even if it costs more than the harm caused by the crime. Furthermore it establishes the feeling of solidarity and belonging together in the society. Foucault thought that punishment is a statement of authoritative dominance; Elias placed the enforcement of punishment into the process of civilization.

However, the recognition of the social necessity of punishment does not mean the agreement of views upon the social function of punishment. The justification of punishment corresponds strongly to what we think about its purpose. The theories concerning punishment adapt to the wider idea of the state on the justification of the use of punishment, and also mirror the views of mankind of a given age.

If we regard the function of punishment as a category already given in legal thought, which criminal law borrows from ethics, it needs no further justification.[3] "Punishment is a sanction that concerns dignity, as opposed to any other legal sanction." - claims András Szabó.[4] "The function of punishment is not other than - he says elsewhere[5] - to ensure impeccable cohesion through the preservation of the liveliness and effectiveness of community awareness, and the addressee is not primarily the criminal, but this community of decent people, in whom the lack of punishment would raise serious doubts concerning the effectiveness of the norm. In other words, the fundamental role of criminal punishment is actually the strengthening of the broken law. ... Crime negates this cohesion and solidarity categorically, and cohesion and solidarity would weaken if there were no community answer, and would not equilibrate the loosening of social solidarity." Determent can be "differentiated through its distinct and unmistakable emotional nature from all other sanctions applied by non-criminal areas of law" - states István Bibó. Determent is therefore "a sanction of deep outrage in spite of its rationalized and institutionalized form of legal procedure. Consequently, we are unable to accept a system of punishment that simply aims at functional defence: we feel it is indifferent towards the crime, and it lacks the solidarity towards the outrage of the victim and the vic-

- 231/232 -

timized community."[6] Can the deterring nature of the punishment be decreased? We might ask and answer with István Bibó's own words: "it can only be decreased in case and to the extent of the decrease of society's incline to outrage and determent."[7]

But did society's incline to outrage and determent really decline at the beginning of the 21st century to an extent that solidarity with the victim can be expressed not only through a deterring sanction? Can society afford the luxury to try to provide the equilibrium between the harm, damage, and suffering caused for the victim, and the malum caused by the punishment to the offender without the application of a deserved punishment? In order to be able to answer these questions, we must be familiar with society, its state of affairs, structure and nature. We must know what kind of social order it stands for, or wants to stand for, how it regards deviants, and what kind of measures it considers suitable for deviants - formal and criminal or informal and non-criminal measures.

The search for the causes of criminal human behaviour changed the theories about the justification and purpose of punishment. Denis Szabó divides these criminological approaches into "consensual" and "conflict" models, emphasizing that based upon the two paradigms, these are rather to be labelled intellectual currents. The ways of the two paradigms in their views on man, and the relationship between man and his surroundings differ fundamentally. One of them claims the great ductility of human nature, in which environmental factors play a great role.[8] The changeability of man as an idea leads to the requirement that the punishment should be effective, therefore the main function of the punishment becomes prevention. The greater emphasis placed on community interests increases the possibilities of the state to interfere to a greater extent in order to achieve the wished goal, and combine the punishment system with welfare elements. We can determine which elements of the crime are actually or potentially dangerous: this way we can cause the offender "harm" through the punishment, in order to prevent the greater damage done by the committing of a further criminal act. Szabó calls this view of man "homo socials".

The opposing approach regards man as a "homo morals", which is sceptical concerning the abilities of man to change and it claims that a man's actions and behaviour are determined by the biological and psychological boundaries of the human body. It does not take into consideration the possible consequences, when justifying crime and the possible future effects of the punishment. It evaluates the act done in the past, which in itself determines the measure of the necessarily punitive reaction.

- 232/233 -

By Durkheim, punishment is the metaphor of moral communication, but its practical language depends fundamentally on the cultural sensitivity of society. Punishment as moral communication is only effective, if it can be interpreted in only one way,[9] and if the one punished truly understands the message of the punishment.[10] Post-modern society is characterized by the plurality and clash of values and cultures; therefore punishment as a reaction of state authority can be interpreted in multiple ways. According to Sherman's studies for instance, members of different groups of society interpret the interference by the police in cases of family violence differently.[11] Therefore the sanction, as a definite and direct reaction to the act can be questioned, because the individual is socialized in a special form of social relationships and reactions, which in a given case may transfer values that are in opposition to mainstream culture. The reasonableness or unreasonableness of a sanction is not always determined the same way by lawmakers, law-enforcers and the citizen. Reasonable sanctions enforce obedience to the law through underlining the legitimacy of the validity of law. Unreasonable sanctions, however, lessen obedience to the law, as they lessen the legitimacy of the validity of law.[12] The fairness of any humiliation depends upon the offender's social bounding to the enforcer of the sanction and society itself,[13] which is emphasized by Sherman from another angle: "the effectiveness of criminal sanctions depends on the basis created by informal social control. Therefore, the more informal social control decreases, the more careful and held-back we have to be in applying criminal sanctions".[14] However, criminal sanctions can be reintegrative, but also humiliating and exclusive.[15]

- 233/234 -

The sentencing practice therefore not only shows the changes in criminality, but also indicates the mode of practicing authority held to be rightful, and follows the modifications in the feeling of security of citizens. The larger the tension between society's fear of crime and the efficiency of justice, the more possible the want for repressive-authoritative criminal policy, and opposing, the longer a given justice system is able to fulfil its duties with the measures available, and satisfy society's need for security, the wider room it shall have for a more humane and liberal criminal policy.[16] The essence of criminal sanction is therefore determined by the wider cultural and social environment, which is also indicated by the fact that the sentencing practice of different countries does not necessarily correspond directly to the tendencies of criminality. Aebi and Kuhn justified with European data that the frequency of imposing imprisonment is in no relation with the tendencies of criminal behaviour.[17] In 1979 in Sweden, the prison population decreased in spite of the increase of crime rate. Svensson claims that an explanation is provided by the attitude of Swedes, who - especially in case of crimes against property - find restoration more important than imprisonment.[18] Christie found a similar difference between crime rate and prison population.[19] Platek, based on Polish data, draws attention to the following: the increase of the male prison population resulted in an overcrowdedness of prison, the Polish government therefore targeted the decreasing of prison sentences for female offenders. The number of female offenders imprisoned declined in spite of the crime rate being constant.[20] Savelsberg compared the criminal and sentencing data of Germany and the United States for a longer period of time. He found that in Germany prison population declined, although the crime rate was up by 25%. Between 1970 and 1984, the 75% growth of the crime rate was only accompanied by a 50% growth in prison population. In the United States, in spite of the dramatic increase of crime in the 60s and 70s, the frequency of the imprisonment sentence did not change. On the other hand, along with the slight increase of the crime rate in the 1980s, imprisonment sentences doubled. Savelsberg explains the phenomenon with the treatment and labelling theories' sudden popularity in the

- 234/235 -

60s and 70s that hindered the dramatic growth of prison sentences. The punitive attitude of Americans developed only a little late, after the end of the great increase in crime rates. The attitude of the public to crime did not develop in itself; it was rather parallel to the strengthening of the neoconservative approach, as a result of which the responsibility for success and unsuccessfulness both economically and socially transferred from the state to the individual.[21] A large number of research experiences have been compiled to show that punishment, as a social institution does not connect to criminality only, but also to economical and social status, especially in well identifiable groups of society. John Irwin, when examining American prisons, came to the conclusion that, irrespective of sanctioning principles, the American prison serves as a means of

controlling the potentially dangerous group of poor and unemployed population.[22]

2. The metamorphosis of punishment

The dilemma of "Why we punish?" is closely connected to the question of "How we punish? " In course of the arguments on sanctions, one thing seems to be agreed upon: in the process of the metamorphosis of punishment, the greatest change occurred at the turn of the 18[th] and 19[th] century, when physical punishment was replaced by institutionalized punishment, what was so logically deduced by Foucault.[23]

Concerning the changes on the essence of punishment, the next big step had come in the 1960s, which evaluation is ambiguous. From among the new phenomena of the mid-20[th] century, Andrew Scull assigns great significance to two parallel tendencies:

1. community corrections movement, in which the offenders are dealt with in the community, instead of locking them up in custodial institutions,

2. community care movement, which treats mental patients under community circumstances along similar guidelines, and which results in the systematic closure of large-scale psychiatric institutions.[24] (Although in my opinion this does not clarify, whether the closing of large psychiatric institutions is an effect or a cause of this principle.)

- 235/236 -

Scull claims that the similar treatment policy of "bad ones" and "mad ones" was made possible by the policy of decarceration dominating both domains. He originates the intention of decarceration from a necessity of cost-cutting, and he does not regard it as intent to create more effective forms of treatment. In his opinion, the abolishing of institutions served neither the interest of deviants, nor that of the public. The process was not a planned one, but a quick step from treatment to non-treatment, which resulted among other consequences in homelessness and big city ghettos.

Reducing the problem to solely financial elements simplifies it to quite an extent. It implies that the state was forced to abolish institutions, because the traditional methods of treating and controlling the "problematic population" had become relatively expensive, even though the cost could have been cut in other ways as well, such as through cutting welfare costs. According to Cavadino and Dignan, this was exactly what the state did: simultaneously with decarceration, the state diminished the expenditures on public service.[25] However, why public service expenses had been cut only in the welfare services, whereas criminal justice was provided increasing financial support, demands an explanation. Stanley Cohen evaluates the above phenomena not as a changing, but as a strengthening of the essence of punishment. The changes of criminal policy connected to the appearance of sanctions enforced in the public provide strong evidence for the control mechanisms of the state being deeply incorporated into society.[26] He identifies a number of forms of this kind of spreading of control. Cohen regards the formation of public justice as a form of disciplinary measure, which penetrates into society through the large institutions. Mathiensen, who emphasizes the possibility of control in relation to not only individuals, but also to whole groups and categories of persons, carries on the thought. According to his example, the forms of control involving developed technical devices are furthermore dangerous, because the features of disciplinary measures change, and the application of open measures becomes more and more hidden.[27] Bottoms, however, contradicts this view.[28] In his analysis, the disciplinary measure in the Foucaultean sense contains two key elements:

- 236/237 -

authority, and the practical technique of tampering a person's soul in order to compel an obedient, law-abiding behaviour. This way the form of control mentioned by Mathiensen is a more developed one, but only a technical part of police work, and not the practical technique Foucault talks about. Furthermore, Bottoms points out an interesting fact in the post-war sentencing practice: the significant growth in the frequency of financial sentences. Notwithstanding it could serve as a substitute for imprisonment, it cannot be interpreted as a disciplinary punishment in the Foucaltean sense. This is because neither the financial sentence, nor the suspended sentence required the constant surveillance of an institution of the criminal justice system, therefore it had the role to provide equilibrium opposing to disciplinary sentence. The conclusion is thus drawn, not the disciplinary forms spread in the mid-20[th] century, but the so-called judicial-jurisdiction model is renewed, which, beside physical punishment, and the replacing institutional punishments, provides a third alternative. Bottoms explains the repellence of their model in the course of development with the techniques of social control, which were built upon this model and had proven ineffective at the time to maintain social order. There is indeed a second big transformation in the mid-20[th] century, this, however, should not be interpreted in the way that the control concentrated in the prison proliferates into society, but that institutional punishment starts moving towards judicial punishment systems. In the course of this process, the role of punishment among the instruments of social control rather decreases than grows. Contrary to institutional punishments, the offender was meant to be reformed through disciplinary measures, the aim of judicial punishment is to "downgrade individuals to objects", which is served mainly by the formation of uniform sentencing conditions. Bottoms says that the dominance of the judicial system is indicated by the fact that the enforcement of a number of sanctions is not controlled formally by an organization of criminal justice, such as the financial sanctions and lately compensation.[29]

Needless to say, both directions mentioned are present in the criminal justice practice of today. In spite of being able to argue - especially regarding the European development - either for the proliferation of the control of criminal justice, or for that of judicial punishment and of strengthening the symbolic function of punishment, the first model regarding community punishments is more significant. Bottoms, as well as Cavadino and Dignan also argue that there is no such agent of criminal justice on stage, that would help in expanding the control.

- 237/238 -

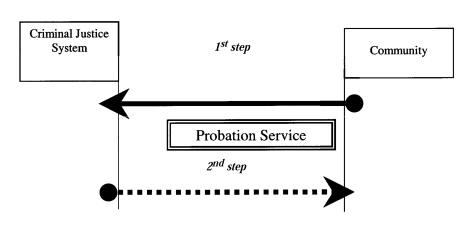

In my opinion, today's changes in community sanctions (and probably also the changes in direction) can be interpreted as a social extension of control. This is perhaps because there is an agent already present in the community, which is able to expand the disciplinary control of criminal justice: it is the probation service. This role is made fulfilled by two new features of the institution enforcing community sanctions: (1) the new approach in criminal policy that pushed these organizations into the community arena, and defines the victim and the community more and more as a client instead of the offender. However, this change would not be in itself sufficient for the proliferation of control. There is another identifiable element, which, connected to the former one, solves the problem: (2) the principle of zero tolerance concerning antisocial behaviour that disturbs the quality of life. Probation services, being "trapped" between the two areas, cannot do anything else but transform the expectations back and forth. Besides, there are two further characteristics to be identified, which underline the statement: (a) the change of the principle and philosophy of crime control, which is necessarily present in the aims to be accomplished with the punishment, and (b) the defining of those governmental goals, which connect the probation services closer and closer to the sphere of criminal justice. The mechanism can be illustrated with a relatively simple diagram.

The aforementioned process can be most plastically traced in a governmental intent conceived in the United Kingdom, which binds the probation service to criminal justice. This convergence can be experienced in other countries as well. The paper entitled "The new foundations of the parole service" published in Norway in 1993 had as one of its fundamental suggestions for change "the need to establish a closer organizational link with the criminal justice sys-

- 238/239 -

tem".[30] The new Dutch projective "Sanctions in perspective" transformed the old "task-based" legal consequences into criminal sanctions, which "are enforced under the probation service's strict supervision, from the sentencing to the withdrawing of freedom and through the phases of constraint of freedom to social reintegration."[31] The same tendency is to be observed in Eastern-European countries, where the newly formed or transformed probation services are originally in close connection with the criminal justice branch.

The degree of punishment depends upon the degree of moral outrage - claimed Denis Szabó. The degree of moral outrage, however, depends rather on how much the public trusts the effectiveness of the organizations of public safety -he adds most practically.[32] This trust can naturally be defined in a positive and a negative manner as well, and can have heightened significance in cases, which are not carried out under closed institutional circumstances. The noncustodial penalties do not only raise the question where their place is among the arsenal of criminal sanctions, but also the question of along which guidelines and principles should they be applied. Do they have to be imposed in accordance with the requirement of proportionality, and if yes, how can this be achieved? Does it have any significance that these sanctions place a smaller financial burden on the criminal justice system than imprisonment? Have the special features of the "environment", in which these sanctions are carried out, to be taken into consideration? Is it important how criminal justice regards community?

The relationship between state, market participants, and citizens changes doubtlessly and is constantly transforming in late-modern societies, as did the explanation of the need for this relationship. In the past decades, the gradual dominance of the idea of community in criminal justice and in neighbouring areas was detectable. New categories such as community policing, community prosecution and community justice or community correction all indicate that the notion of community has indeed come into close proximity with criminal justice. These phrases nonetheless also indicate that this relationship is created between participants, among which connection would have been unimaginable a few decades ago. Among the sanctions the formation of the idea of community penalties, or the means of restorative justice (such as mediation, compensation, or family group conferences), which introduce new characters into the

- 239/240 -

system of accountability, and apply formerly unknown ways of problem solving, all indicate that community has become a central notion in criminal justice. Thus, there seems to be a need to examine, which elements justify the riveting of this notion in criminal justice. Does the essence of this concept differ from that in other disciplines, does it rearrange the correlation between the traditional and new participants of criminal justice, and does it change the functioning of criminal justice? The concept of community in the aforementioned context deserves further examination from at least two aspects: from the relation between (1) crime and community, and (2) community and the criminal justice system.

3. The concept of community

Let us start by clarifying what we mean by the concept of community. According to Vilmos Csányi "the biological optimum of social aptitude is at small groups of 50-100, perhaps at tribal and clan formations of a couple of hundred members. In modern societies, people belong to numerous groups and organizations at the same time, nonetheless quite loosely. ... The groups based upon relationships involving feelings and faithfulness are less significant ... Modern people behave as though they themselves were a group."[33] Community can be defined as a neighbourhood, school team, trade union, civil circles, or circles based on friendship, large family, native tribe, or any other actual group -claim Bazemore and Griffiths.[34] Howard Zehr uses the word "shalom" to describe a group, which is peaceful, obedient, and free. This does not mean no conflicts, but oppositions and crimes are secured by a process that respects all rights - especially those of children.[35]

Most sources build the concept of community upon one or more aspects of social complexity, which can be a geographical territory, consensus, division of labour, etc. Tönnies' description relies on the distinction of the concepts of community and society, according to which all trusting, homely and exclusive coexistence should be regarded as a community (Gemeinschaft). Community is a living organism, whilst society is a mechanical compound, an artificial crea-

- 240/241 -

tion (Gesellschaft).[36] MacIver and Page emphasize the social relations of the individual and community cohesion in the definition of community: "community is an area of social life, which is characterized by a certain degree of social cohesion. The fundament of community is locality and a feeling of community." The development of communication weakens without doubt the criterion of being bound locally, but this change in the opinion does not diminish the relation between social cohesion and geographical location in the concept of community.[37] It is an accepted statement in the social studies of today that "high modernity" is formed by the twin processes of globalization and localization.[38] It is thus an important aspect, stressed by MacIver and Page that communities exist within larger communities, and that the basis of community is locality. Talcott Parsons takes on a systematic approach in defining community as a special phenomenon of the structure of the social system, which can be regarded as the local arrangement of persons, as well as their actions.[39]

The feeling of belonging together, of belonging somewhere has a central place in many approaches of the concept of community. The close relationship, however, exactly because of the aforementioned technical development, does not necessarily mean territorial identicalness. Melvin Webber mentions professional communities as an example, members of which maintain close relationships with a wide network of fellow professionals, who may live all over the world. Webber concludes that the fundamental element of community is therefore communication. Thus, he names two defining elements of community: mutual interest and communication.[40]

The concept of community does not only occur in relation to the need of clarifying conceptual terms, but many times out of emotional reasons. The main question of this approach is: how can something, which is lost, be restored? The conclusion is - interestingly - mostly that the trouble is not with the community, but much more with the people the community is or should be constituted of.[41] Putnam's description in 1995 was that America is no longer a nation

- 241/242 -

of joiners; Americans are "bowling alone", not in bowling leagues. Some might respond so what or good riddance.[42] The socio-psychological approach cannot be forgotten when dealing with the concept of community, which defines it as a compound of personality types, as "every community can set boundaries to the possibilities of the development of personality".[43] It is hardly a coincidence, that the hero type of American films is the lone ranger, the 'one against all'-type, whereas in Europe the hero is more wavering, full of doubts. Community gets great emphasis in the system of arguments of conservatives, especially in regarding the possible emotional aspect, the lost community, which is not only a preserving, but also an environment full of requirements. Amitai Etzioni created the communitarian manifesto in 1991, in which great emphasis was placed on the need to establish balance between rights and obligations.[44] In defining the concept of community Etzioni mentions as important the closeness of relationships and the community of culture. Community can be mostly characterized by two features - he says - the creation of effective networks of relation within groups of members (opposed to simple pair attachments, or a chain of individual relationships), such, which thoroughly intertwine the group, and one strengthens the other. At the same time the concept of community also contains commitment, which means accepting the values, norms and approaches adapted by the community.[45] This approach claims that there are two simultaneous powers predominantly present: the centripetal power of community and the centrifugal power of individual autonomy. These two powers, obeying rules and autonomy are present in the tension between rights and obligations.

It is hardly a coincidence, that connection with the concept of community, the question of the relationship of different communities is raised, just as the problem of majority/minority, which puts the problem in a special light concerning the relation between community and crime. According to Hobsbawm, "the word community had never before been used without any consideration or content, than in the decade in which communities, in the sociological sense, were most difficult to find in real life".[46] During the past decades, the relationship to crime, as a community problem changed. It became general in public

- 242/243 -

opinion and politics that crime is a result of the decline and malfunctioning of the community, which can be traced back to the weakening of community relations, to the moral decline of the community, and on the whole to the malfunction of the informal control mechanisms of the community. This approach leads directly to the idea that crime can be decreased through the strengthening of communities. The key element of the approach is how to define the community - along what guidelines and principles -, the community that needs to be strengthened. A further problem is that in some cases community norms themselves lead to breaking the law - as already proven by research on sub-culture and the football-hooliganism of nowadays. Regarding crime prevention Currie points out convincingly that community can be defined out of two premises, which evaluate the possible problem-solving capacities of a community differently. The first hypothesis, characteristic especially of political discourse, assigns a symbolic meaning to community, and explains it as a given allocation of common approaches, actually from a socio-psychological point of view. It relies upon the symbolic notion of community in people's minds, and if attitudes and symbols can be changed, that does not only lead to the right behaviour, but also strengthens the people's sense of community and vice versa. In the field of crime control, the principle of "broken windows" shows that the concept is easily definable on the level of symbols and attitudes being significant. Wilson and Kelling say that the "policy of broken windows" in the field of crime control means that it cannot be detached from community. On the contrary, it depends upon the success in restoring and strengthening community: "the new focus in maintaining public order is not the vigilance liberals' fear, but the new sense of optimism, in which civilization and community can be restored.[47] According to Currie, the symbolic approach of the first premise lacks the "structural awareness" of the second one. From this point of view, the community is not merely an allocation of approaches, which needs to be "implanted" or "mobilized", but an active creation of institutions of long-term effect (e.g. work, family connections, religious and community organizations) that are able to affect integrity of economic and social forces.[48]

The elements of the concept of local community, especially locality - 'belonging somewhere' - and the system of relations regarding a given community are extremely significant in the evaluation of the new developments of crime control. This feature is not to be neglected when examining community sanctions, because this is the environment, the locality, in which alternative sanctions are

- 243/244 -

realized. Interestingly, a small number of sources are attentive to the question of community, they rather focus on the effectiveness and the enforcing 'technique' of sanctions. The literature concerning crime prevention deals with the question in ample detail; therefore I shall use these sources to analyze the 'enforcing environment' of community sanctions. I will not deal with the quite rich literature of crime prevention; I will rather concentrate on the problems that can influence the enforcement of community sanctions.

4. New notion in the system: the 'community safety'

The studies of latency indicate that citizens assign greatest significance to those crimes, which were committed in their residential area. There are differences in the security of the residential areas, merely being a member of a minority can be a determining factor in victimization: black Americans have a 31% greater chance of becoming a victim than whites.[49] Crime prevention therefore aims at influencing the individual and social causes of criminality, decreasing the danger of committing a crime, reducing the harmful effects of criminality on individuals and society, as well as the fear of crime of citizens. The importance of crime prevention and the imposing of preventive factors are not questioned, and have extreme significance in dealing with petty offences and unlawful behaviour endangering the life of a local community. It is more and more accepted that this is associated with the activity of local self-governments.

Naturally, the question arises: why did the approach emphasizing the security of the community prevail just in the 80s and 90s? It is clear that by this time it became apparent that the system of crime control is no longer able to follow the growth of crime, and to bring to a halt the unfavourable changes, so new solutions were indispensable. The loss of trust in the state had a central role in the process. Especially the faith in the state's ability to guarantee safety, and because of the escalation of social fear, people have begun to 'take back' the care for their own security from the state. The loss of trust is characteristic not only in connection with the institutions of criminal justice, but also with governmental establishment in general. Although in the 1970s the distrust in authorities was regarded as a democratic crisis, today it is rather regarded as a requisite of the modernization process.[50] This is illustrated by the fact that in the new

- 244/245 -

member states of the EU, 27% of those questioned trust their countries' legal system, whilst the rate was 48% in the old member states. There is a significant difference regarding the trust in the police: 45% of the citizens of the new member states as opposed to the former positive answer of 65% given by old member states.[51] Americans employ 1.5 million private police officers for duties the professional police force is unable to handle.[52] Accordingly, it is interesting to note the study, which shows that Americans trust neither their banking system, nor the education system, nor the system of state justice. In spite of this, their trust in the police is quite high. In Sherman's opinion, the loss of trust is to be traced back to the general decline in trusting hierarchical relations.[53] His example illustrates the symbols of inequality manifested in criminal justice by the procedures that require persons to stand up as the judge enters the room, or citizens who are required to obey instructions of the police, even though the police officer in charge is disrespectful. These rules suggest that the official is more important than the citizen, and this intensifies the distrust in law. He defines the theory of procedural equality, according to which the equal treatment of citizens encourages trust in authorities. Thus, people demand relationships based upon equality in all areas of life. Let us examine Sherman's statements and align his claims and the aspects he does not take into consideration. According to him, citizens do not accept hierarchy in the public sphere, as the authenticity of state establishment's declines. However, American citizens believe in the police, even though it is also an institution of state authority. Sherman explains this with egalitarian culture and the prevailing of consensual procedural equality, which he traces back to the changed relationship of police and public. The police pay attention to local problems, play a role of service, and interpret its activities according to the consensual model. All of this sounds very convincing. It fails to recognize, however, that the relation of state power and citizens cannot be interpreted simply from the point of view of equality. Especially, because people do not at all esteem each other equal in interpersonal relationships, as they do not question financial inequality. Most people accept other types of differences beside financial inequality, such as differences in sexuality or forms of coexistence in families. (This is what Moynihan refers to, when speaking about the "devaluation" of deviance.) Financial inequality is what produces actual differences, not only regarding income circumstances, but also opportunities and possibilities for the promotion of interests. In other words, the acceptance of financial inequalities cannot be fit into Sherman's consensual model of equality. The symbols pre-

- 245/246 -

vailing in criminal justice do not really represent the person wearing the judge's robe or the police officer's uniform, but rather the connotations of the role. Just like a medicine man is not respected by people as a person, but as an entity, whose function is to establish a link with gods and supernatural powers. The special treatment is for the role, and the person embodying the role. Consequently, if people do not want to stand up upon the judge's entering, or do not follow the instructions of the police officers, that is not because they feel themselves equal, but because they do not respect the role the person embodies, and do not obey the rule it represents. The theory of procedural equality does not take into consideration an important initial step, namely that the requirement of equality only arises in those cases already chosen. The theory of procedural equality therefore returns to the concept of equality before law, which it replenishes with a few new elements, but leaves the very important question open, whether it is in connection with the equality of opportunities. The consensual procedural model could indeed be significant in criminal justice, and can have an important effect in treatment of offences, especially in the assistance to proliferate measures of restorative justice. As if, beside the "consensual equality model" existed a "consensual inequality model", for the analysis of which one needs to step out of the justice system to the examination of systems of social inequality. A detailed analysis would lead far from our studied topic, however, it needs to be noted that it can have significance, when dealing with community sanctions that most people now accept the "splitting apart" of society, that is to say normalizes the phenomenon, and assigns a role to criminal justice in dealing with the consequences. The greater trust in the police is most probably due to the fact that this organization is thought to guarantee security.

Giddens claims that the main reason for the changing of the community is due to the alteration in the source of trust. The importance of local trust has been replaced by relationships, which correspond to abstract systems that are not fully embedded.[54] The research of Lawrence Friedman shows that the nature of authority has changed in modern cultures built upon fame: the former vertical point of view (in which people looked up to their leaders) has been replaced by the horizontal approach (in which people choose a leader from the centre of society, whom they know by name and face).[55] It is unquestionable, says Bottoms, that trust used to be locally based, and that most important relationships were those of family and relatives. The local community meant a geographi-

- 246/247 -

cally well-definable territory, where members of the community knew each other. Religion was practiced in local churches, and traditions served as a guideline for actions. The local binding of trust did indeed weaken, but has not fully disappeared. Instead of local trust, financial and political guidelines have become important, and the ability to adjust to one's surroundings constantly. Personal relationships have also altered, "people increasingly define themselves as individuals rather than in the context of group affiliations. In the field of personal relationships, trust is increasingly placed on personally chosen one-to-one relationships".[56]

Liddle feels the relationship of globalization and community has to be examined, when dealing with the question of crime prevention becoming a community issue.[57] The change in this relation - in close connection with the welfare state becoming a residual welfare state - resulted in the state withdrawing himself from direct service provision to co-ordinate service delivery. The changing of this role is well illustrated by the boat example of Osborn and Gaebler: the advancing of the boat depends on the strength of the oarsman, whereas the heading depends on the skill of the boat-setter, the state therefore has become a boat-setter instead of its former position of oarsman.[58] Not only did state functions transform, but also the relationship between central and local governments, as did the structures through which central governments made an impact.

It is hardly a coincidence, that there is always a contradiction between the use and recognition of the necessity of short term (situational) and long-term (social developmental) aims of crime prevention. The practice of crime prevention shows that situational and social developmental crime prevention fuse easily in the idea of community security: it endeavours to limit the opportunity of crime in every possible and actual way, and takes into equal consideration all possible and actual motivations for committing crimes. This combination has been realized in practice with the primacy of situational measures. New technique (such as CCTV, electronic monitoring) is applied intensively in situational crime prevention, and influences to a great extent the acceptance of measures of community sanctions, which operate along the same principles (such as electronic surveillance or house arrest). The question of community security was supplemented with the purpose of influencing the citizens' fear of crime. The gravity of the problem is represented by the irrationally great fear of crime

- 247/248 -

compared to the general situation shown in the British Crime Survey.[59] Research data show that the lack of feeling of safety is not connected to traditional categories of crime, but rather to the disorder of the environment, which contributes to the discomfort of citizens: graffiti, neglected residential areas, parking difficulties and the growing number of beggars.[60] It is of great significance that the lack of feeling secure is not characteristic of those in actual danger of becoming a victim, but of those, who are only insignificantly endangered, and it has the consequence that they regard their environment as a hostile one, which they cannot control.[61] The reference to community does not only mean the place in which they apply measures of crime prevention, but also the community, which invites to participate in problem-solving - it is naturally doubtful what kind of co-operation can be achieved in the general lack of feeling of safety. The approach towards crime and other breaches of law, as well as the changing of the self-image of the community can indeed have a significant impact on the enforcement of community sanctions.

As I have already mentioned, the determining factors of belonging to a community are territory and the 'feeling of belonging somewhere'. Both raise the question, where the boundaries of community lie, or more precisely, what are the boundaries of acceptance and exclusion. The question is in close connection with the other important element of belonging to a community, which requires the acceptance of community values and rules. The acceptance, however, presupposes the community to be homogeneous, and this homogeneity is exactly what simplifies the decision for crime control based on community: it can rely on social groups, in which the presupposition proves to be true. Crime prevention provides the example, which illustrates the paradox nature of the hypothesis: the movement of neighbours for each other can best be organized in middle-class areas, where the problem of crime is insignificant (unlike the fear of crime).[62] It is also a fact that this approach does not function at the most endangered groups: it is impossible to form groups of crime prevention in areas of disadvantageous situation with a high crime rate.[63]

- 248/249 -

Undoubtedly, the community measures of problem solving applied in the field of crime prevention are innovative, meet the expectations of the community, and refer to a systematic-theoretical approach. The question remains, however, how local community is defined by the forming cooperation between the local residential groups, the local business sphere and civil organizations. In the crime prevention strategy of community safety, the differentiation between social and situational may lead to the differentiation of " us " (those who obey the law) and "them " (those to be controlled, deterred, and punished).[64] The policy and practice of crime prevention building upon community ideas may not only change the relationship of certain groups of society, but has also begun to reorder the relationship between citizen and state, and to draw new boundaries between public and private domains and between "legitimate citizens" and suspects or outsiders.[65] The community in this respect also demonstrates the existence of an 'in-between' area, which is situated somewhere between the individual and the far-away government, and is able to combine the conservative idea of individual responsibility with the liberal approach, which believes that individual problems should be treated within the community. The logic of prevention seeks for the earliest opportunity to intervene: so early that the problem has not even evolved, so that it can be dealt with before it becomes unmanageable. With zero tolerance, this purpose leads to even stronger control. What was regarded as pre-delinquent behaviour is now labelled as antisocial, or as an act that 'worsens the quality of life', and justifies early intervention according to the theory of 'broken windows' before the decline and the spiral of disorder starts, or the criminal career develops. This is the area of zero tolerance, which leaves little room to the constructive measures with the use of means of criminalization and control.[66] The security of community as an objective reaches far beyond the traditional scope of criminal offences.

It is unquestionable that the community approach more and more characterizes the debate on the diverse measures of crime control. With this, however, the danger of substituting possibilities comes along, limited by guarantees of the institutions of criminal justice by the definition of "community", and the "community" becomes a general solution to a lot of problems relating to criminal justice. Garland calls the attempt of the state to seek to shift responsibility to the individual and the market through making links with the community and the private sector as the responsibilization strategy, and defines it as

- 249/250 -

redistribution of the tasks of crime control.[67] The danger becomes especially big if governments prefer the community-oriented approach. In political rhetoric, the references to community indicate that in this context, community means groups of humans, which are theoretically unified, but split apart in the practical realization of community control. They split apart into groups of people living in mainly middle-class environments, whose anguishes have to be decreased and who have to face relatively few problems, and into people, whose problems, or rather the problems related to them, need to be diminished with means of control. Some approaches endeavour to make people part of symbolic places from which they were excluded, while other approaches are rather interested in identifying and isolating the social groups to be excluded, forgetting entirely the necessity of integration. The possible consequence is indicated by the formation of actuarial justice, in which the danger involving individuals is replaced by the danger involving groups, and the treatment of dangerousness requires the application of generalized measures of control, as well as the elaboration of developed techniques of control.[68]

In the field of crime control, locality became first significant in the practice of community policing, which seeks to increase community participation in crime control. Tyler's research shows that Americans, especially members of minority groups are highly sensitive to how the criminal justice system treats them, and polite or rude behaviour of officials becomes more important than whether they are fined or not.[69] The prevailing of procedural equality, or the lack of it, influences the people's attitude towards authorities. However, the essence is pointed out by Szigeti in relation to community policing: "heterogeneous social norms of heterogeneous communities form the nature of social norms beyond legality in modern, pluralistic society; therefore the taking over of competence beyond legality and the control of everyday moralities could mean an unlawful interference in the life of a given community."[70] The problem is similar concerning the community relations of other institutions of criminal justice. The 'community policing' can become a notion without content (as authorization and mutual dependence), and can be easily regarded as a solution for various urban problems - warns Kaminer.[71]

- 250/251 -

We nevertheless experience that the notion of community has a life of its own in criminal justice, and after the police all traditional organizations of criminal justice have been assigned with the attribute of community. All signs indicate that the criminal justice relies more and more on the community performing its duties, and this process continues to evolve. This can be detected not only in the United States, but also in Europe, nevertheless with different content - in the long-term as I would like to believe. The community has doubtlessly great significance in the implementation of non-custodial sanctions, although numerous factors have not yet been clarified. The recommendation of the European Union on community sanctions[72] does not deal with the defining of community in connection with alternative sanctions, it only reacts to the 'non-custodial' component, and does not at all take into consideration the environment, in which these sanctions are enforced. The content of community sanctions is determined by the status and cultural characteristics of a given community. In this context, it is especially important to take the ambivalent tendencies of today into consideration: the simultaneous presence of the usually merely rhetorical global inclusion and the very practical local exclusion. Gilling has quite a pessimistic view of the future in claiming that "although reformers and people of leftist values may regard this change as the reoccurrence of welfare values in the area of criminal justice, it is not what is happening in practice, and is highly unlikely to happen in the future".[73] McGuire on the other hand feels that the interest in rehabilitation is reviving, which is also indicated by the probation programs building upon the conscious regulating of behaviour applied by parole services and the community initiatives effective in the decreasing of repeating offences.[74] Carney has a similar opinion in evaluating the Australian situation in observing that the application of drug-courts and restorative justice are characterized by the "direct achieving of determined social purposes (such as rehabilitation and reintegration)".[75]

However, probation services, the objective of reintegration and rehabilitation should not yet be dismissed in criminal justice. It is nonetheless a fact that the approach, which eliminated the moral elements from punishment and regarded it as a purely therapeutic treatment based on social work, has indeed come to an end. As I stated in 1995, the difference between the English and the Hungarian

- 251/252 -

parole service is that the English one is too close to social work and is too far from the expectations of criminal justice.[76] In Hungary on the contrary: there are no relations to the social sphere, only to criminal justice. The right way is somewhere in the middle, where criminal policy and social policy are overlapping each other. In other words, the probation service can be the organization in criminal justice, which enables the cooperation of different professions, and establishes a link between the traditional and modern measures of the criminal justice system. However, the somewhat hectic times in criminal policy do not really facilitate this evaluation. Although no final analysis can be made, we are able to enumerate the existing tendencies, and even more articulately identify the probable dangers impending upon community punishments.

5. Alternative sanctions and community sanctions: old content in new disguise?

Imprisonment roots in the principle system of the Enlightenment, and was an "alternative" sanction raising hopes as opposed to the death penalty, body mutilation, forced labour or the galley. At that time it not only seemed a humane and rational solution, but also carried in itself the possibility of rehabilitation and reforming the offender. It is more than a hundred years ago, that the idea of alternative sanctions surfaced instead of short-term imprisonment, first in connection with juveniles. Since then, perhaps only except the USA from among the defining countries, the treatment system of juveniles has always been an experimental ground for progressive initiatives. This is well detectable in the field of community sanctions.

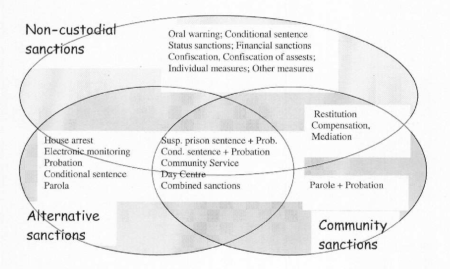

The systematic placement of alternative sanctions and the enlightening of its other features should be started with clarifying the concept itself. As György Vókó rightly states, in the area of sanctions not involving imprisonment, the alternative is actually ambiguous: (a) it can mean the process before the court phase, which purpose is to hinder the case to be taken to court, (b) it can also mean the actual precipitation of imprisonment, (c) and the elimination of the harmful effects of the imprisonment.[77]

The question has even more sides, as different approaches in criminal policy may have notions with definitely different significance:

- 252/253 -

1) The concept of non-custodial sanctions in its neutral formulation does not mean anything else, than that the sanction is not enforced in a closed institution.

2) The usage of alternative sanctions in criminal policy refers to its ability to decrease prison population.

3) Community sanctions indicate that criminal policy relies on community resources during the process of enforcement of the sanction.

The development of community sanctions characterized by steps forward and backward, shows a constant search and change. This search firstly lead to a) formation of alternatives of short-term imprisonment, and the appearance of new forms of sanctions, and b) the development of effectiveness-augmenting elements, which increase the authenticity of sanctions. At the same time, the new forms of community sanctions occurred together with the rebirth of old forms.

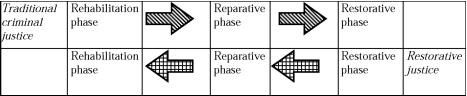

In the first phase of development, the alternatives of imprisonment surfaced in the 1970s and 80s. The search for alternatives and new solutions was urged by the disappointment of the reforming ability of imprisonment and the extreme numbers of prison population, therefore at this time, similar to the first phase, the search aimed at alternatives for short-term imprisonment. Hudson claims that although developed countries were in modern times characterized by reform, rehabilitation and resocialization, there existed a combination in different ways with determent (USA, UK, and West-Germany), deterrence (Scandinavia), or neutralization (France, Italy). It seems that the countries, which emphasized general deterrence were the ones looking for imprisonment substituting solutions, or encouraged suspended sentences, whereas the countries preferring determent and individual deterrence moved towards the application of community based alternative sanctions.[78]

The scepticism surrounding the reforming ability of prisons in connection with the rehabilitation capacity of the prison became a part of formal criminal policy, and the criminal justice systems of almost all European countries began to look for new alternatives. This happened when suspended sentence and community service emerged. The theoretical debate of the 60s emphasized the unwanted effects of imprisonment, such as stigmatization, but at this point, in spite of the aforementioned crisis of experience, the rehabilitation of offenders still had strong support in politics as well as in public opinion. The crisis of resource of the first burst of energy prices in the mid-1970s, similar to other public services of the state, justified the decreasing of costs in criminal justice.

- 253/254 -

The new sanctions had an increasingly double purpose: (a) certain forms still served rehabilitation (b) other forms aimed at cutting costs by deterrence from a penal way, or by cheaper sanctions. Furthermore, the approach according to which there should be a wide variety of sanctions at hand in the service of individualization resulted in the expansion of the types of non-custodial sanctions. In the theoretical crisis, the authenticity of the rehabilitation ideology was questioned, which not only concerned the frequency of use of the probation as an alternative sanction, but also placed the organization itself into the centre of debate. The harsh philosophical contradiction between the supporting and controlling side of the service and the sanction itself became an issue. The categories of alternative sanctions, intermediary sanctions and community sanctions have been present from this time on.

The third phase of alternative sanctions came about in the 1980s and 1990s. At this time, a number of new phenomena are detectable in the development of these kinds of sanctions. New sanctions appear, which enforce elements of control and supervision to a greater extent, at times exclusively (such as house arrest), and as a consequence of technical development, new more and more sophisticated forms of control develop (such as electronic monitoring). The management approach emerges in criminal justice and consequently, the question of the effectiveness of sanctions becomes important. This explains the fact that in most countries of Western Europe, these new forms of sanctions become applicable on their own right after a so-called pilot, a trial phase. As a result of economic hardships, more and more forms of diversion surface in criminal procedure. The measures of restorative justice appeared among these diversion forms, which do not only decrease costs, but may also serve the constructive ending of the procedure. This era coincided with the requirement of the punishment to be a proportionate and deserved reaction to the offence, which affected the contextual features of alternative sanctions.[79] The thought on criminal policy in the 1980s pointed towards the enforcement of the repressive element of sanctions. The re-evaluation of the concepts of punishment and control began in the United States and in some countries of Western Europe already at the beginning of the 1980s, as indicated by the appearance of intensive forms of supervision, such as the regulation in England concerning juvenile offenders. House arrest was introduced in a number of US states in 1983, and adapted later by the Netherlands, Sweden and the UK, and later its combined form with electronic monitoring as a result of technical development.

- 254/255 -

In the 1990s, labelled "smart penalties" by Garland, a new generation of punishments appears, which in part meet the expectations of the stricter criminal policy, and in part reflect the new achievements of technical development: in the field of non-custodial sanctions, combined sanctions and forms of restraining freedom secured by electronic monitoring emerge. It is unquestionable, that the idea of rehabilitation, which has been a principle thought of criminal justice, has faded. The emphasis of criminal policy has changed: the attention is drawn primarily towards organized crime and new types of offences, towards offenders who make rational decisions, are foreign or belong to a minority group, and finally towards the criminal responsibility of legal persons.[80]

As detectable from the above, a hundred years after the formation of alternative sanctions it became clear that the road can lead elsewhere (also): the expectations on rehabilitations in penitentiaries have not been met, and it seems as though the world would once again believe in the prison sentence. At the same time, although only on the margin of criminal justice, the system of measures of restorative justice has emerged, making room for new interpretations of resocialization.

6. The place of alternative sanctions in the sanctioning system of criminal law

The raising expectations regarding the functioning of the justice system (such as the simultaneous securing of the timeliness of procedures, and the safeguarding of guarantees), and the increasing load of crime both burden the functioning of criminal justice. Therefore, the measures of sanctioning offenders within criminal justice and the forms of diversion all attempt to ensure that the system of measures of criminal justice be able to answer, at least partly, to the wide palette of crime. We must naturally never forget that if we try to adjust the sanctioning system to criminal behaviour and offenders, we only take into consideration those offences and offenders, which we know, that is to say non-latent crime. Regarding this characteristic the containment of crime is impossible with only the operating of criminal justice. If one compares the present, even merely the European, sanctioning system with that of 30-40 years ago, one is faced with the phenomenon that the "simple" system of sanctioning using fines, conditional sentences and suspended sentences has disappeared in most countries. The list of sanctions was complemented by non-custodial sanc-

- 255/256 -

tions such as intensive probation, community service, compensation, restoration, mediation (agreement between victim and offender), or the suspension of the driver's license. Educational courses and training programs for the learning of consciously influencing behaviour - especially regarding drug and sex offenders should also be mentioned here. Sanctions prescribing supervision and participation have become part of the sanctioning system, as have the participation in probation hostel and daytime activities, curfew, house arrest, electronic monitoring, suspended sentencing with supervision, combined measures (which contains in itself two or more elements), and countless other solutions.

Besides the aforementioned changes, there is another development, which seems extremely important. In the case of alternative sanctions, civil law "infiltrates " more and more into criminal law and criminal procedural law. This process has been intensified by the appearance of the measures of restorative justice. Naturally, this loosened the system of criminal law from multiple aspects, but the "loss" seems to be equalled by the "profit" of the effectiveness of using sanctions. The need of solutions of civil law in the sanctioning system is indicated by the attitude studies in connection with criminal law, according to which criminal justice should ensure protection from the offenders of violent crimes, the accountability of offenders, the restoration of the damage caused, the treatment of offenders, and the possibility of participation in the decision process.[81] A lot of research data show that the expectations of citizens concerning punishments are less rigorous than politicians believe.[82]

The Directive of the European Union defines community sanctions as: "punishments and measures which do not tear the offender away from society, but contain elements of restraining freedom through the imposing of diverse conditions and obligations, which are enforced by an authorized organization."[83] The malum element of alternative sanctions is therefore the restraining of freedom, labour and supervision; their rehabilitative effect is based upon the reintegrating force of the community. Accordingly, community sanctions serve the defence of society; their aim is to prevent the offender from repeating the offence. Behind every alternative sanction, however, there is the possibility of a custodial sanction, consequently the non-fulfilment of the conditions may result in imprisonment.

- 256/257 -

The sanctions belonging to community punishments are not agreed upon in literature, supposedly because "everything" (imprisonment) and "nothing" (probation) can be placed on a wide spectrum. Neither is great emphasis placed on this by the resources, the standpoint of authors can be detected by examining which sanctions are discussed, when dealing with community/alternative sanctions. Bard mentions the suspended sentence, house arrest, and the financial sentence, whereas Levay discusses the suspended sentence, community service, additional sanctions and measures and financial sentences. Albrecht cites the financial sentence, confiscation, confiscation of assets, suspended sentence, the parole service, compensation, restoration, and electronic surveillance.[84] Zvekic, taking into consideration the new phenomena of crime and criminal justice differentiates between traditional alternative sanctions substituting custodial ones and new types of non-custodial sanctions (confiscation, adjudication, inhibition).[85] Most authors in the United Kingdom group these sanctions based on the British sanctioning system, which is obvious to the extent that the statute itself treats the sanctions organically. The Research on Crime and Justice of the UN differentiates four groups of alternative sanctions: (a) non-custodial supervision, including probation as well, (b) warning and suspended imprisonment and the conditional sentence, (c) financial sentence, (d) community service.[86]

In the Hungarian national practice community sanctions can be placed between imprisonment and the financial sentence, irrespective of the fact that the Hungarian sanctioning system is not as polished as certain Western-European systems. I emphasize the contextual elements of non-custodial sanctions, and regard some non-custodial sanctions as community sanctions based on the following conditions:

1. they serve as an alternative to imprisonment, therefore their enforcement is non-institutional, but carried out in the community,

2. they contain elements of restraining freedom and support (although to alternating extent), and

3. there is a continuous and active (personal) relationship with the parole service (as the traditional organization in charge with the supervision of these sanctions), or with non-traditional participants (such as mediation).

- 257/258 -

Community sanctions are situated structurally between imprisonment and fine. The statement, however, raises numerous problems of denotation. Imprisonment deprives the sentenced totally from freedom, and during the enforcement of the punishment, isolates the offender from the community. (I do not take into consideration the temporary leave from the penitentiary in this respect.) Community sanctions are realized in the outside world, but the offender is burdened with a lot of obligations. Community sanctions can be distinguished from custodial sanctions by way that they do not contain a deprivation of freedom; they only have elements of restriction. Fines and other financial sanctions do not take away the freedom of the sentenced person; they nonetheless do contain financial restrictions. However, they miss the immanent element of community sanctions: the active relationship with one of the participants of criminal justice, and they do not require the partaking of community resources. The same element is missing by house arrest and electronic surveillance, where there is a relationship with a participant of criminal justice (either the police, or the parole service), but this is not an active one, much rather the passive behaviour of tolerating the surveillance technique. Therefore, I do not regard them as community sanctions, although they indeed function as an alternative to custodial sanctions. The commitment of the community and its participation in the enforcement are sine qua non conditions of community sanctions, especially those of community service, employment programmes, and sanctions involving the victim, and it is exactly based upon this characteristic that makes the labelling of community sanctions adequate. Consequently, "hybrid" types

- 258/259 -

of community sanctions should also be mentioned here, which combine custody with the community-part of the sanction, which do not involve the deprivation of freedom.

Most European countries do not consider legal solutions that shorten the duration of the imprisonment or moderate the severity of enforcement (such as weekend-custody, half-closed, half-open institutions, partly suspended sentence etc.) as real alternatives for imprisonment. Most resources of literature nevertheless discuss these sanctions as community punishments, as they reinforce the effect of integration. I also feel that these sanctions, if not formally, contextually do belong to community sanctions. This legal consequence meets all three requirements, because it substitutes custody when the inmate is on conditional release. In this respect, it could be risked that if we consider the capability to substitute imprisonment, conditional release is the "genuine" community sanction, as it actually substitutes imprisonment (at least during the parole phase), which is not so unambiguous in case of other community sanctions. On the other hand, this sanction does not belong to community sanctions, as it is not an independent sanction, but an additional element of the imprisonment sentence - at least in Hungarian criminal law.

The question of parole shows the insecurity of approaches, which characterizes community sanctions. Because of the insufficient theoretical fundament, these sanctions believed to be sanctions of substitution in most countries, they subordinate them to the 'real' sanction, the imprisonment. There is an uncertainty concerning the identification of the aims of community sanctions: they wish to ensure on the one hand the restoration of the consequences of the offence, and on the other hand would like to redress the personal and social problems of the offenders. This is very clearly detectable in the probation sentence. The double duty of the probation officers of treating the offender as a client, offering assistance and support, and as a participant of criminal justice exercising control and supervision, is hardly reconcilable. The support of underprivileged offenders, as they form the majority of the clientele of the probation service, is necessary, but may concur with the expectations of the public for punishment: the sanction should be taking something away from the offender, and not the other way around.[87] The point of view of the law is not at all obvious in this respect, mostly its clear and unambiguous purpose cannot be determined, and the different rationalities undermine the authenticity and application of these sanc-

- 259/260 -

tions.[88] The Model Law on Juvenile Justice represents the conceptional confusion: while in many countries community service for juveniles is placed among educational sanctions, this model law treats it as criminal sanction.[89] Because of the above insecurities, judges do not realize the punishing aspect of this sanction, although Point 6 of the European Rules confirms, "that the personal circumstances of the offender should be taken into consideration, but regarding the severity of the crime".

Hamai claims that the parole service is not an outside solution to the inside problems of criminal justice and criminal studies, but a possible frame into which the necessary and applicable measures can be embedded.[90] Consequently, the content of non-custodial sanctions and the method of enforcement are always determined by the preferred objectives of the current criminal policy. As the immanent element of alternative sanctions is the simultaneous realization of supervision and assistance, they can either be labelled as community treatment, assistance, or as community surveillance. The central part of the problem is constituted by the inner philosophical contradiction drawn between the functions of control and social support, one of which is emphasized by changing criminal policies. At the same time, the British Crime Survey and the survey initiated by the minister of justice of Victoria, Australia indicated that the results of a survey very much depend on the way of posing the question of what citizens think of suitable sanctions. If the question is "What do murderers deserve?" the answer will naturally be "To be hanged!" However, if the person questioned receives information on the case, the circumstances, motives and background, we see that citizens would actually welcome even milder sanctions, than those of the existing sanctioning practice. Not to mention the fact that all studies on victimology confirm that victims assign primary importance to restoration and compensation.

In past times, the objectives connected to the use of non-custodial sanctions changed significantly.[91] New types of criminal sanctions are indeed quite flexible, because of the combination of diverse sanctions or elements of sanctions.

- 260/261 -