Miklós Lévay[1]: 'Social Exclusion' - a Prosperous Term in Contemporary Criminology; Social Exclusion and Crime in Central and Eastern Europe* (Annales, 2006., 119-142. o.)

1. Introductory remarks

This paper will be basically dealing with two issues. One is the content of the concept of 'social exclusion'. Here I will cover the components of the concept, the most important measures of the European Union to combat social exclusion as a social phenomenon, certain conclusions in the professional literature as to the relation between social exclusion and crime, as well as the significance of this concept and its relevant research in the development of criminological thinking. The second topic of the paper is the relation between social exclusion and crime in the former socialist countries, particularly in the countries that joined the European Union on 1 May 2004.

2. On the concept of 'social exclusion'

2.1. The concept and term of 'social exclusion' is more and more often encountered in works on criminology. I think this term and concept has two facets: it is simultaneously true that we understand its contents and it does not call for clarification, and, on the other hand, it is not necessarily self-evident what 'social exclusion' means. As a result of the latter supposition, I will give a short overview of the major semantic contents of the concept.

Ever since its first appearance in the 1980s, 'social exclusion' has nearly always been a concept in social sciences and a policy program at the same time. Regarding its latter form, we have to add for accuracy's sake that it is reducing 'social exclusion' and ensuring its opposite, 'social inclusion'. It has become

- 119/120 -

widely accepted in the social sciences very fast. An eminent authority on the topic, Atkinson, wrote about its causes as early as in 1998 that the popularity of the concept was partly due to it not being elucidated.[1] By now, however, and -mostly thanks to Atkinson himself and his fellow researchers - the contents of the concept have been clarified even if not in the form of a definition. Its essence, I think, is truly expressed in the following description by Julia Szalai, a Hungarian sociologist: "The term 'social exclusion' has an ... unambiguous semantic content, which at the same time has several layers. The concept represents a process, the state resulting from the process as well as - through the preposition/prefix 'ex' - a relation at the same time. This latter is the most important layer of content of the concept, and hints at the consequence of the unequal distribution of power, attributably to which the social position of certain players is protected in a way that results in other players getting into a deprived state".[2]

As for the process and state, the definition by Trevor Bradley says: "social exclusion refers to the dynamic, multidimensional process of being shut out, fully or partially, from the various social, economic, political or cultural systems which serve to assist the integration of a person in a society".[3] The concept hints at the same time at the marginalisation, impoverishment, social isolation, and vulnerability of those affected and at the lack of full 'citizenship'. Thus 'social exclusion' is a concept covering people and groups being 'shut out of' the everyday life of society in multiple deprivation, which concept has essentially replaced the category of "underclass", primarily in the European social sciences. The professional literature is agreed on 'social exclusion' being a collective phenomenon, the basis of which is the increasing inequality and insecurity related to the structural and social changes in society.

2.2. Following Jock Young's work of outstanding significance, The Exclusive Society (1999), criminology literature differentiates three levels of 'social exclusion'. The first level is "the economic and material exclusion of individuals denied access to paid, full-time employment". The second is "the isolation from relationships produced by social and spatial segregation" And the third one is "the ever-increasing exclusionary policies and practices of the criminal justice system".[4]

Regarding the title of the work by Young referred to and with respect to the topic of the second part of my paper, I also have to mention the categories of 'inclusive society - exclusive society' that have developed in connection with

- 120/121 -

the term 'social exclusion'. According to the author mentioned the first one is a "society which both materially and ontologically incorporated its members and which attempted to assimilate deviance and disorder", while exclusive society is one "which involves a great deal of both material and ontological precariousness and which responds to deviance by separation and exclusion."[5] According to Young, the last third of the 20[th] century is a period leading from modernity to late modernity, and which is a period of transition from inclusive society to exclusive society.[6] In a later work, however, the excellent author emphasises that "inclusionary and exclusionary tendencies must, of necessity, exist in both periods."[7]

2.3. In policy, primarily in social policy programs we encounter the concept of 'social inclusion' in the mid-1980s in a framework of efforts aimed at the elimination of poverty. Supported by the European Community, research work that covered the phenomena of social exclusion was started from 1985 on.[8] With respect to the propagation of the concept, and what is more important, with respect to combat against the phenomena, a significant stage is represented by the Treaty of Amsterdam of 1997, modifying the Treaty on the European Union. Its Article 136 namely stated that the European Union and its Member States declared the combating of social exclusion to be their objective.

The European Council in Lisbon in March 2000 represented a landmark in the Union's combat against social exclusion. Partly because at the summit "social cohesion as an effort appeared at the same time as the economic objective that the Union should be the most competitive region in the world within a decade."[9] And partly because the presidency conclusions "called the number of people living in poverty and social exclusion in the European Union unacceptable"[10] and identified the major method of combating social exclusion. And that is an open method of coordination between the Member States, in which the Member States share the positive experience of their National Action Plans on Social Inclusion with each other. As one of the instruments of the open method of coordination the presidency conclusions of Lisbon ordered the elaboration of indicators suitable for measuring poverty and social exclusion and for comparing the two phenomena between the Member States. The Social Protection Committee and its sub-commission on the indicators with the involvement of social scientist - including Atkinson, whom we already mentioned, and his colleagues - prepared the social indicators. The principle underlying the preparation of the indicators was that "an indicator should explore

- 121/122 -

the essence of the problem, and that it should have an unambiguous and accepted normative interpretation."[11] Finally a three-level system of specifications was accepted. The primary indicators include the most important indicators leading to social exclusion. The secondary indicators serve the purpose of the deeper exploration of individual problems related to the primary ones. The primary and secondary indicators are the commonly agreed indicators of the Union, and each Member State is required to use them.[12] Tertiary indicators "include indicators that are decided by the member states in accordance with their particular features."[13] These do not need to be harmonised, however the National Action Plans on Social Inclusion may assist in the interpretation of the primary and secondary indicators. Tertiary indicators of social exclusion reflecting national features are for example in Great Britain the indicators showing the risks increasing poverty and social exclusion, such as frequent absence from school or juvenile pregnancy.[14] The commonly agreed indicators are not final lists, and their improvement is still on the agenda so that the dimensions of social exclusion can be grasped as appropriately as possible.[15] The common indicators were agreed on at the European Council of Laeken in December 2001, and the presidency conclusions declared them to be "important elements in the policy defined at Lisbon for eradicating poverty and promoting social inclusion."[16]

It can be said that today in the European Union combat against social exclusion takes place in terms of promoting social inclusion. And that means - quoting Klára Kerezsi, a Hungarian criminologist - that "the European Union policies for the prevention and redressing of social exclusion regard increasing the offer of services, strengthening solidarity and assisting the re-socialisation of those living in or threatened by social exclusion as of primary importance."[17] The institutional components are as follows:

- The commonly agreed objectives of the Summit in Nice in December 2000 on poverty and social exclusion,

- National Action Plans on Social Inclusion,

- Commission and Member States Joint Reports on Social Inclusion,

- Common indicators,

- Community Action Plans for promoting cooperation between the Member States in combating social exclusion.

- 122/123 -

2.4. From a criminological point of view, the importance of declaring the eradication of social exclusion to be a European Union objective is that combating the processes and the phenomena leading to social exclusion has its impact on the social risk factors of crime as well. And the objective mentioned has created an opportunity for an old criminological perception to prevail finally in practice: that is "efficient social policy is the best criminal policy."

The eradication of social exclusion as an objective is present not only in the documents of the Union and its Member States on social policy. For example the Drug Strategy of the European Union for 2000-2004 states in connection with demand reduction that "the general public should be informed on the effects of the social exclusion, particularly from the viewpoint of the drug problem." Unfortunately, I have to add that there is no mention of avoiding social exclusion in the strategy for the years 2005-2012. However, we can find it mentioned in the National Strategy for Crime Prevention of Hungary adopted by the Parliament in 2003. In the Strategy one of the constitutional requirements of crime prevention is avoiding exclusion. In this context the Strategy states: "Combating crime is a socially accepted objective. However, measures taken to pursue this objective, and the fear of crime, have the possible side-effects of excluding certain groups and raising prejudices against juvenile delinquents, ex-prisoners, drug addicts, homeless people, poor people and Gypsies. The social crime prevention system is based on the principle of social justice. It must therefore endeavour both to avoid social exclusion and prejudice and to uphold rights of security."[18]

2.5. To conclude what I wanted to say on the use of the concept of social exclusion as a policy category, let me refer to the Constitution of the European Union including provisions of this kind. For example Article 3 on the objectives of the Union states: The Union shall combat social exclusion and discrimination, and shall promote social justice and protection ... (Article 3.3.). Among the provisions on social policy, the Constitution declares that the objectives in this field have the primary purpose of serving high employment and combating exclusion (Article 209.).

2.6. The following will be a short overview on the most important findings in the criminology literature on the relations between social exclusion and crime.

The concept of social exclusion has been present as a category in works on criminology since the late 1980s or early 1990s. Its application and propagation was helped by its initial lack of definition and vagueness, but also by the fact that it could be used to describe and interpret the relations between inequalities, poverty, deprivation, stigmatisation and crime more comprehensively. In addi-

- 123/124 -

tion, if we accept, following Jock Young, that "crime itself is an exclusion"[19], then we can take the success story of the concept in criminology for granted. The criminology literature of the topic shows basically two approaches to the relation of the social ecxlusion and crime. One approach puts the emphasis on crime as being a consequence of social exclusion, and the other stresses that social exclusion is a consequence or by-product of crime, or rather that of the operation of the crime control system.

The approach interpreting crime as a consequence of social exclusion is typically based on research into registered offences, particularly property crimes and the offenders, as well as juveniles and recidivists. The common lesson of the research is that social processes and states leading to social exclusion encourage crime, furthermore that an increase in the number of those excluded from society "can itself generate certain types of crime."[20] Approaching the relation between social exclusion and crime from the social background of the offenders, the findings by Jakov Gilinszkij on deviances in Russia can be regarded as typical. In a paper he indicates as one of the causes of the disorganised state of Russian society the exclusion of masses of the population from the active life of society. Then he writes the following: "deprofessionalisation (loss of profession), dequalification (loss or lack of qualification), marginalisation, alcoholism, impoverishment . unemployment. These excluded people give the fundamental social basis of crime, drug abuse, alcoholism and suicide."[21]

It was following the recognition of 'the universality of crime' (a term used by Jock Young), that is the recognition that crime is not the 'privilege' of the deprived and excluded, as well as after research into the exploration of the selectivity and harmful effects of the criminal justice system that the other approach to the relation between social exclusion and crime began to spread, which says that social exclusion is a consequence and by-product of crime. One of the major messages of research based on this approach is that the total crime in a society is not represented by registered crime and those excluded from society are overrepresented only among the registered offenders. Research has also shown that using the criminal justice system against certain social problems exerts by itself exclusionary effects. This is particularly true for criminalising drug use.

At the Criminological Research Conference of the Council of Europe of 2003 Heike Jung focused attention on the fact that legislation demonstrating a safety-oriented and strong state is counterproductive. Professor Jung emphasised that the consequences are social exclusion and an increasing lack of feeling of secu-

- 124/125 -

rity.[22] In the fields of research which emphasise that social exclusion is a consequence of crime, most results that were also unambiguous to the greatest extent were achieved on the relations between the activities and operations of the criminal justice system and social exclusion. The research laid a special emphasis on the harmful effects of imprisonment on reintegration. It can be established from the results that "prison is the definitive form of exclusion and the imprisoned are a distinctly excluded population."[23]

Other aspects of the operations of the criminal justice system also exert stigmatizing effects leading to social exclusion. These include the obligation of accounting for previous convictions. In this respect, however, it is a welcomed development that in its Recommendations of 2003, New Ways of Dealing with Juvenile Delinquency and the Role of Juvenile Justice, the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe asked the Member States - quote - "to facilitate their entry into the labour market, every effort should be made to ensure that young adult offenders under the age of 21 should not be required to disclose their criminal record to prospective employers, except where the nature of the employment dictates otherwise."[24]

In addition to the above, the criminology literature on the relation between crime and social exclusion gives high priority to the fear of crime, as well as to the relations between crime prevention and the privatisation of security and social exclusion. At the conference of the Council of Europe of 2003 already mentioned, Klaus Boers made important statements on the relation between fear of crime and social exclusion in his paper. Among other issues, he talked about the reasons for overestimating the problems of fear of crime in a situation where the rate of fear of crime had been decreasing in several countries since the mid 1990s. Boers answer and conclusion is: fear of crime provides an opportunity for general social agreement on the measures for keeping crime under control and for crime prevention; these measures, however, - as Boers warns us- are not necessarily aimed at the offenders and crime, but at people undesirable for public order; and for the measures leading to social exclusion reference to fear of crime provides the appropriate legitimisation foundations.[25] Boers mentions among other things that the evaluative researches into closed circuit television systems (CCTV) show the use of the system is justified by aspects of social exclusion (for example expelling beggars and drug users from shopping precincts) and police tactics, including costs saving (reducing the number of patrols), rather than by crime and considerations aimed at reducing crime.

- 125/126 -

The commercialisation of security or opening the market of crime control is also linked to social exclusion. Evaluating the developments in Poland, Maria Los states that many people cannot afford the goods and services offered by private security companies. And this results - she writes - in "(T)hose who did not gain economically with the advent of the market or whose living standards actually dropped experience further marginalization because they cannot afford the private security measures the market flaunts."[26] Papers on the topic also point out the impact of the 'privatization of public space' resulting in spatial segregation and thus social exclusion.

2.7. To conclude the first subject of my paper I wish to evaluate the significance of 'social exclusion' as a concept and of the related research for the development of criminology thinking. First, I wish to determine in which criminological perspective of the interpretation of crime we can put the concept and the research field.

In my view the three prevailing criminology perspectives are as follows: a) the social perspective, b) the individual perspective and c) the situational perspective. Social perspective is the approach that interprets crime as a social phenomenon. This means both that crime is a phenomenon that can be derived from certain social, economic and cultural factors and that the crime and the criminal justice system are both social constructions. The individual perspective focuses on the individual processes of becoming an offender, and the situational perspective focuses on the situations of offences and crime opportunities. Each perspective has its own crime prevention approach.

Interpretations and research of social exclusion fall into the social perspective of criminology thinking. Within that, they represent a continuation of the tradition starting with Durkheim, which gave priority attention to the investigation of the relations between social cohesion, the phenomena and processes influencing its state and crime. The theoretical and experimental works on social exclusion strengthen the social perspective and enhance this tradition. Due to the multi-dimensional concept of social exclusion, both the social phenomena representing the social risk factors of crime and the impact of the operation of the crime control system leading to social exclusion can be studied. I think that thanks to the works and research on the topic, the social perspective of the interpretation of crime has by now come out of the shadows of the situational perspective of the past years. At the same time, in addition to situational crime prevention, social crime prevention has been given greater emphasis, which led to the requirement of social justice in the response to crime. And in criminology, the increasing attention given to social exclusion creates a chance for

- 126/127 -

criminal policy - in the words of Katalin Gönczöl - "to prevail as part of social policy and harmonised with welfare policy."[27]

In a recent study (2005), Lawrence Sherman considers the predominance of theoretical works over experimental works to be a negative concomitant phenomenon of the development of criminology since the Enlightenment: "For criminology to be truly useful, it needs to be accurate, not just used"[28], writes the American criminologist and for this purpose urges the propagation of experimental criminology. I have quoted Sherman's statement because his statement is also true for the criminology literature on social exclusion. If the criminology of the field deserves any criticism, it is because there are a great deal fewer empirical research results on social exclusion than analytical conclusions. I think more experimental criminology would be justified for the purpose of enhancing the efficiency of policies against social exclusion as well as for improving the relevant theories.

In the second part of my paper I will be looking at certain issues of social exclusion and crime in the former socialist countries of Central and Eastern Europe.

3. Social exclusion and crime in Central and Eastern Europe

In this study I am trying to find a hypothetical answer to the same question that Krzysztof Krajewski attempted to answer in his paper at the course of the International Society for Criminology held in Miskolc in the spring of 2003. The question is "to what extent this (Jock Young's formula) 'transition from modernity to late modernity can be seen as a movement from an inclusive to exclusive society'[29] applies also to Central and Eastern European countries."[30] It has already been discussed what these two kinds of society mean. Now I would only like to add that Young considers stability and homogeneity to be qualities of inclusive society and change and division to be qualities of exclusive society.[31]

The first problem to arise when answering the question is whether the former socialist countries of Central and Eastern Europe were inclusive or exclusive societies. I agree basically with those who regard the socialist countries before the changes of 1988-1990 as examples of the exclusive type of society.[32] At the

- 127/128 -

same time, if we look at the characteristics of the first of the three levels of the appearance of social exclusion, it seems justified to modulate this qualification, particularly with respect to the developments in economic and welfare policies existing in these countries today. In the countries of the one-time real socialism, certain features of inclusive society were present in the economic and welfare sphere, primarily a kind of secure livelihood, a not very high level of living standards and moderate differences in incomes. The last item is well illustrated by two figures from Hungary. In the 1970s in my country the average income of the upper tenth of the population was about 4.5 times as high as that of the lowest tenth, while at present the difference is nine-ten-fold.[33] These features derive from the ideology of the period which made efforts to reduce the inequalities and increase public welfare.[34] Its prevalence was helped by the lack of private property. The factors mentioned can explain the full employment in the period studied and in certain countries the level of welfare provisions similar to the level in the welfare states. Naturally, it has to be added that from the '80s on primarily in the countries that made attempts at introducing a limited extent of market economy, the inequalities increased and furthermore cutting down on the welfare expenditure of what was called 'the premature welfare state' was begun. All this resulted in an increase in the proportions of the absolute and relative poor. The characteristics of the other two levels of social exclusion in the socialist period reflect the features of exclusive society, which I do not think justify any modulation. However, I want to make two remarks on the third level. One is that the one-time 'solid public safety', a lower level of crime and of fear of crime than there exists today and there existed in the Western countries of the period, existed in closed societies and often under authoritarian-type conditions, and lack of freedom, so we cannot regard them as features hinting at inclusivity. The other remark is: at the same time in spite of a not very dramatic crime situation, in the former socialist countries the number of the prison population was extremely high: in the former socialist countries of the region the prison population rate per 100,000 of the national population was or exceeded 200 in the 1980s.

On the basis of all this it can be said that the former socialist countries of Central and Eastern Europe began the transition into capitalism as exclusive societies in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Has the transition changed this feature of the societies and the features of what type of society can be identified today? Before giving an answer, and before drawing, I stress, the hypothetical conclusions, let us first examine some characteristics of the transition from the aspect of social exclusion.

- 128/129 -

The most important qualities of content of the transition are: the party-state was transformed into a state founded on the rule of law and based on parliamentary democracy, the planned economy was changed into a market economy, and the restriction of human rights was replaced by their guaranteeing. From the point of the structural transformation of society, the introduction of market economy was of decisive significance. Its implementation, however, entailed a number of dysfunctional effects and consequences, harmful to social integration. According to a Hungarian sociologist, Zsuzsa Ferge, the same two factors determined the introduction of market economy in almost all countries transforming their regimes. One is a global factor, the reign of the neo-liberal economic doctrine; the second is linked to the countries involved, and it is the ability to assert the previously repressed ownership and economic interests.[35] In order to achieve the latter, those had a better chance who had the appropriate political connections, professional, or perhaps financial capital. It can be attributed to the common impact of the two factors - states the sociologist - that "the increase in inequalities became very fast, and did not meet any legal, political or moral barriers. The result was a more unequal distribution of the shrinking gross domestic product than before, ... mass unemployment, the impoverishment of the majority of the population, a deepening of poverty, the shrinkage of the welfare systems and a transformation of their principles, a crash of the security of livelihood."[36] These processes were characteristic of the first period of the introduction of capitalism and brought about the first 'losers' of the transformation, the outcasts of society. We can only guess at their numbers and rate within a country's population. Thus, for example, according to the Laeken indicators, in Hungary 13% of the population, approximately 1 million 300 thousand people qualified as poor according to the poverty limit measured in 2001. At first glance this is barely worse than the 15% average of the old Member States of the EU. However, the poverty limit as defined by the EU is 60% of the median income calculated on the basis of one consumption unit, and that is less than the amount of subsistence level, it is about three quarters of that. Calculating on the basis of subsistence level, the rate of the poor in Hungary is about 30%.[37] According to the survey of 2001 based on the Laeken criteria, the poverty rate is 8 % in the Czech Republic, 11 % in Slovenia, 15 % in Poland.[38] (There are no data for Slovakia.) The rate of the permanently unemployed for the individual countries for 2002 shows that in the new Member States masses in considerable numbers have become excluded from the labour market.

- 129/130 -

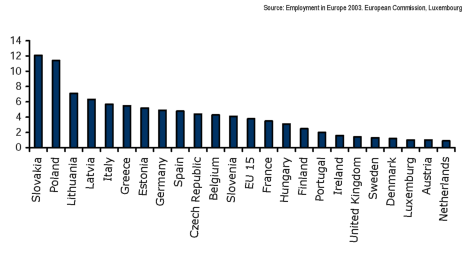

Long Term Unemployment Rate of the Age Group of 15-64 in Europe, 2002

Unfortunately, I have to add to the figure for Hungary that according to the latest report, Hungary is not under the average of the EU-15, for the rate now is 7.1%.

As regards unemployment, there are significant regional differences in the majority of the countries discussed, that is, there exists a spatial segregation. In estimating the rate of those excluded, the situation of the Gypsy population in the region is to be taken into special consideration. "Today there live more than eight million Roma (Gypsies) in Europe, 70 % of them in Central and Eastern Europe, and on the Balkan. All international surveys show - writes one of the Hungarian researchers of this ethnic population - that the Roma minority is at present the poorest group in Europe, which suffers the greatest number of discriminations against them."[39] To illustrate their situation in Hungary, I'll give you a few data from the national representative Roma survey of 2003. Their number is approximately 600 thousand, which is about 6 % of the total population. Roma families with an average income belong to the lowest income group of the total population. Among the 1 million people with the lowest income 280 thousand, that is 28 % may be the number of Roma. Spatial segregation is shown by the fact that 72 % of the Roma live in an environment segregated from the majority society. And finally some figures on their situation in the labour market. 21 % of the Roma population above 15 years of age had a job in

- 130/131 -

2003. In the same year the employment level was 51 % in Hungary. The tendency is shown by the fact that in the 1970s Roma men capable of work had jobs in the same proportion as non-Roma males. From the end of the 1980s to 1993 30 % of jobs were terminated on a national level, and the same rate for the Roma was 55%.[40]

The following table provides an essential basis for estimating the rate of the excluded. It contains the distribution of social groups in Hungary based on a survey in 1999 asking about lifestyles and consumption habits.

Consumer Groups in Hungary (Housing, material and cultural consumption)

| Groups | Detailed % | Cumulated % |

| Elite | 1 | 1 |

| Wealthy | 9 | 9 |

| Middle - accumulating | 14 | 31 |

| Middle - leisure-focused | 17 | |

| Good housing - Deprived | 28 | 59 |

| Deprived - Poor | 31 | |

| Total | 100 | 100 |

Source: Szívós, P. - Tóth, I. Gy. (eds), MONITOR 1999.

TÁRKI Monitor Reports, 1999. december p. 35. (Hungarian)

On the basis of the figures and the table we can draw the conclusion that about 30% of the population in Hungary can be regarded as excluded. Although the EUROSTAT investigation into the differences in income inequalities shows that there are differences between the new members, for example in Slovenia and in the Czech Republic the inequalities are smaller than in Poland or Hungary, the estimated rate of 30% of the excluded is perhaps a realistic figure for the rest of the former socialist countries of Central and Eastern Europe as well.[41]

The results of the survey of social groups in Hungary show significant similarities to Will Huttons '40:30:30 society', which is characteristic of the transition from inclusive to exclusive. It represents a society "where 40 per cent of the population are in tenured secured employment, 30 per cent in secure employment, and 30 per cent marginalized, idle or working for poverty wages."[42]

- 131/132 -

From the above we can say that regarding the capitalism being stabilised in the former socialist countries, social scientists are justified in talking about a "splitting society".[43] Social exclusion weakening social cohesion is markedly present in these countries. Can the impact of social exclusion on crime be shown? How does the criminal justice system affect social exclusion in these countries? I'll be talking about these issues briefly in the following.

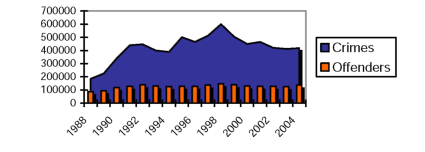

3.4. The collapse of real socialism in all the countries affected was followed by a dramatic increase in registered crime, a worsening of public safety, and a decrease in the people's feeling of security. The intensity of the rise is well reflected in the findings by Imre Kertész - József Stauber on the situation in Hungary. They showed that while in most Western European countries the number of offences per 100,000 of the population was doubled in 15 years, in Hungary it doubled first in 21 years, between 1971 and 1990, and it was doubled for a second time in 5 years between 1991 and 1995.[44] The structure of crime was also transformed: there was a significant increase in the rate of crime against property among registered crime in the first period of transition.

The interpretation of the changes in crime and in the patterns of crime has an abundant criminology literature. What these works share is that they attribute a significant role in the development of crime to the disorganisation generated by the changes. In the second phase of the transition period, typically from the mid 1990s, it is more difficult to find general features and common characteristics to describe the development of crime. We can find, namely, countries like Hungary, where the steep rise has come to a halt, and what's more, as can be seen from the figure, there has even been some decline.

Number of Registered Crimes and Offenders in Hungary, 1988-2004

Sources: Yearbooks of information on crime, Ministry of Interior - Chief Prosecutor Office, Budapest

- 132/133 -

Calculating the number of offences for 100,000 of the population, in my country the highest rate occurred in 1998, which represented 5926 offences; in 2004 the same figure is 4140. On the other hand, as can be seen from the next chart, in Poland registered crime has been increasing steadily in the past years.

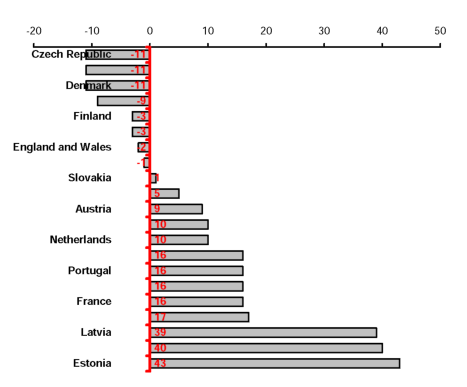

Crime trends in the European Union 1997-2001 (percentage)

Source: Barclay, G. - Travers, C, International Comparison of Criminal Justice Statistics 2001, Home Office Bulletin, Issue 12/03, 24 October 2003

It would be difficult to say anything definite about the causes of the differences without specific research. What we can, however, establish from the criminal statistics of the individual countries, from the European Sourcebook of Crime and Criminal Justice Statistics, from the International Crime Victim Surveys and from the relevant publications, is the level of criminality becoming stable at a higher level as compared to that in the period of 'real socialism' in these countries as well as that this higher level is still lower than the crime rate in the majority of the Western countries. And in terms of the relations between social exclusion and crime it can be seen from research into the social characteristics of the offenders of registered crime that their majority - similarly to the period

- 133/134 -

before the change of regime - have low levels of education, poor social circumstances, no vocational qualifications, no permanent employment or no employment at all.[45] As István Tauber pointed out in his study on the levels of education, employment and income of registered offenders in Hungary between 1990-1999, that "similar to 1981, around two thirds of the offenders were socially marginalized in at least one indicator. However, stated the author, this is a thoroughly new phenomenon today, as demonstrated."[46]

Research in Hungary, however, also shows that within crime against property the number of crime with a profiteering character increases as compared to theft and livelihood crime against property and the offenders are mainly young adults with secondary education.[47] In the background we can find the pressure of social conditions, social exclusion and the fear of becoming excluded in equal measure.

3.5. One of the significant indicators of the relation between the operation of the criminal justice system and social exclusion is the development of the use of prison sentences and the number of those imprisoned. The following table shows the rate of the prison population and within the prison population the percentage of those arrested in the countries of the European Union on the basis of figures of the International Centre for Prison Studies.

Prison Population Rates (PPR) and Pre-Trial Detainees (PTD) in the European Union

| PPR (per 100,000 of the population) | PTD (% with the PPR) | |

| 1. Estonia | 339 | 23.7 |

| 2. Latvia | 337 | 35.0 |

| 3. Lithuania | 234 | 16.9 |

| 4. Poland | 209 | 19.9 |

| 5. Czech Republic | 191 | 15.5 |

| 6. Slovakia | 165 | 33.1 |

| 7. Hungary | 164 | 24.8 |

| 8. Luxembourg | 144 | 49.2 |

- 134/135 -

| 9. UK England & Wales | 144 | 16.2 |

| 10. Spain | 141 | 22.1 |

| 11. Portugal | 124 | 23.6 |

| 12. Netherlands | 123 | 35.2 |

| 13. Austria | 106 | 26.9 |

| 14. Italy | 97 | 36.0 |

| 15. Germany | 96 | 19.7 |

| 16. France | 91 | 35.7 |

| 17. Belgium | 88 | 39.1 |

| 18. Ireland | 85 | 16.4 |

| 19. Greece | 82 | 28.2 |

| 20. Sweden | 81 | 20.5 |

| 21. Malta | 72 | 33.1 |

| 22. Finland | 71 | 12.7 |

| 23. Denmark | 70 | 29.0 |

| 24. Slovenia | 56 | 27.1 |

| 25. Cyprus | 50 | 13.2 |

Source: International Centre for Prison Studies. Last modified: 23.03.2005

At the top of the list are - and this is no credit to them - the former socialist countries, with the exception of Slovenia. "The ghosts of the past are here", we can say, that is, the high imprisonment rate of the period before the change of regime is back. Seeing the figures, we can agree with Krzysztof Krajewski, when he speaks about a "penal gap" in connection with the differences in the prison population rate in the West and East.[48] If we calculate averages based on the figures in the chart for groups of countries, we'll get the following numbers:

- 135/136 -

Average of the Prison Population Rates (PPR) in the European Union by group of countries

| Average of PPR (per 100,000 of the population) | |

| 1. EU 25 | 134 |

| 2. EU 15 (old members) | 103 |

| 3. EU 10 (new members) | 182 |

| 4. Eight former socialist countries | 212 |

| 5. EU 5 (Central and Eastern European former socialist countries) | 157 |

The average of the 25 Member States of the Union is 134, the average of the 15 old Member States is 103, and the average of the 10 new member states is 182. Among the new Member States the average of the eight former socialist countries is 212 and finally among the new Member States the average of the five Central and Eastern European countries is 157. On the basis of the figures and of the fact that crime level is higher in Western Europe, it is perhaps no exaggeration to speak about the gap between the cultures of crime control policies. The data show the situation in 2004, and in some cases in 2005. The tendency in the five countries in Central and Eastern Europe shows interesting developments.

Recent Prison Population Trends in Poland, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary and Slovenia

| Year | POLAND | CZECH REP. | SLOVAKIA | HUNGARY | SLOVENIA | ||||||

| Total | Rate | Total | Rate | Total | Rate | Total | Rate | Total | Rate | ||

| 1988 | n.a. | 212 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 19,366 | 193 | n.a. | n.a. | |

| 1992 | 58,619 | 153 | 12,730 | 123 | 6,311 | 119 | 14,810 | 143 | 836 | 42 | |

| 1995 | 62,719 | 163 | 18,753 | 181 | 7,412 | 138 | 12,703 | 124 | 825 | 41 | |

| 1998 | 57,382 | 148 | 21,560 | 209 | 7,409 | 138 | 13,405 | 132 | 756 | 38 | |

| 2001 | 70,544 | 183 | 21,538 | 210 | 6,941 | 129 | 15,539 | 152 | 1,148 | 58 | |

| 2004 | 79,807 | 209 | 17, 277 | 169 | 8,891 | 165 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | |

| 2005 | n.a. | n.a. | 19,506 | 191 | n.a. n.a. | 16,543 | 164 | 1,129 | 56 | ||

Source: International Centre for Prison Studies. Last modified: 09.04.2005

- 136/137 -

In the first period of the change of regime in spite of the dramatically increasing crime already mentioned the prison population decreased steadily in most of them. In its background harmonisation with the partners in Western Europe in the fields of criminal justice and particularly in sentencing policy was a decisive factor. Later, the sudden increase in crime stopped in most of the countries, and there was a country where it decreased, however, the prison population remained typically stable or rather increased. Among the causes of the increase the law and order views in certain Western countries are to be highlighted - and with this I modulate somewhat what I said about the gap between the cultures of crime control policies of the West and East. Unfortunately, those views found a fertile breeding ground in our region. And the ensuing criminal policy is one of the components of the processes leading to social exclusion.

4. Conclusions

Regarding what has been said so far, what can we answer to the question whether the former socialist countries in Central and Eastern Europe have exclusive or inclusive characters?

I think the statement by Jock Young that the features of exclusive and inclusive societies are coexistence in the societies of late modernity holds true of our countries as well. What is important is the proportions and the main tendencies. In this respect my paper can be read to say that the features of exclusive society are present in the countries of the region to an extent giving rise to serious concern. In addition the fear is that certain global and regional processes and challenges will further strengthen these qualities.

At global level the neo-liberal economic policy and the presence of international terrorism together with the responses to be given can have particularly adverse effects on the character of society. At regional level, and here I mean the European Union, it is a great challenge how we can meet one of the major objectives of the European Union in the new members and in the countries expecting to join soon: reducing the economic and social differences between the Member States. If we do not succeed in meeting this objective fairly soon, then the fear will be that what Maria Los wrote about in 1998, that is that "the East/Central European States ... may ... become a new periphery within the new regional power, European Union"[49] will become reality. Criminology must give priority attention in this social-cultural situation to social justice and to the investigation of phenomena such as social exclusion hindering its prevalence.

- 137/138 -

Supplement

EU Indicators of Social Exclusion I. - Primary Indicators

1. Low income rate after transfers with low-income threshold set at 60% of median income (with breakdowns by gender, age, most frequent activity status, household type and tenure status)

2. Distribution of income (income quintile ratio)

3. Persistence of low income

4. Median low income gap

5. Regional cohesion

6. Long term unemployment rate

7. People living in jobless households

8. Early school leavers not in further education or training

9. Life expectancy at birth

10. Self-perceived health status

EU Indicators of Social Exclusion II. - Secondary Indicators

11. Dispersion around the 60% median low income threshold

12. Low income rate anchored at a point in time

13. Low income rate before transfers

14. Distribution of income (Gini coefficient)

15. Persistence of low income (based on 50% of median income)

16. Long term unemployment share

17. Very long term unemployment rate

18. Persons with low educational attainment

References

Atkinson, A. B. (1998) 'Social exclusion, poverty and unemployment', in A. B. Atkinson and J. Hills (eds.), Exclusion, Employment and Opportunity. CASE paper 4. London: Centre for Analysis of Social Exclusion, London School of Economics, pp. 1-21.

Atkinson, A. B., B. Cantillon, E. Marlier and Nolan, B. (2002) Social Indicators: the EU and Social Inclusion. Oxford, Oxford University Press.

- 138/139 -

Boers, K. (2003) 'Crime, fear of crime and the operation of crime control in the light of victim surveys and other empirical studies', paper presented at the 22[nd] Criminological Research Conference of the Council of Europe, Strasbourg, 24-26 November 2003. Manuscript.

Bradley, T. (2001) 'Social exclusion', in E. McLaughlin and J. Muncie (eds), The Sage Dictionary of Criminology. London, SAGE.

Ferge, Zs. (1999) 'Poverty and crime: is there a desintegrative or decivilizative danger?', (Hungarian) Belügyi Szemle, 2, pp. 3-27.

Ferge, Zs. (2000) 'The polarized society', (Hungarian) Belügyi Szemle, 6, pp. 3-17.

Ferge, Zs. (2002) 'Social structure and inequalities in the old state-socialism and in the new capitalism', (Hungarian) Szociológiai Szemle, 4, pp. 9-33.

Gábor, A. and Szívós, P. (2004) 'Poverty in Hungary is at hand of the European Union accession', (Hungarian), in Kolosi, T., Tóth, I. Gy., and Gy. Vukovich (eds), Social Report 2004. (Hungarian) Budapest, TÁRKI.

Gilinszkij, J. (2002) 'Crime tendencies in Russia', (Hungarian) Belügyi Szemle, Külföldi Figyelő, pp. 83-96.

Gönczöl, K. (1991) Evil poor people. (Hungarian) Budapest, KJK.

Gönczöl, K. (1996) 'Social reproduction of crime in Hungary during the nineties', (Hungarian) in K. Gönczöl, L. Korinek and M. Lévay (eds), Knowledge of Criminology, Crime and Crime Control. (Hungarian) Budapest, Corvina, pp. 108-118.

Havasi, É. (2002) 'Poverty and social exclusion in the present-day Hungary', (Hungarian) Szociológiai Szemle, 4, pp. 51-71.

Janky, B. (2004) 'Income figures of Roma families', (Hungarian) in T. Kolosi, I. Gy. Tóth and Gy. Vukovich (eds), Social Report - 2004. (Hungarian) Budapest, TÁRKI, pp. 400-413.

Jung, H. (2003) 'Government organisations and the influence on public perception of crime and its control', paper presented at the 22[nd] Criminological Research Conference of the Council of Europe, Strasbourg, 24-26 November 2003. Manuscript.

Krajewski, K. (2004) 'Transformation and crime control. Towards Exclusive Societies Central and Eastern European Style?', in K. Gönczöl and M. Lévay (eds), New tendencies in Crime and Criminal Policy in Central and Eastern Europe. Miskolc, Bíbor Publishing House, pp. 19-29.

- 139/140 -

Kerezsi, K. (2004) 'Human safety in Central-Eastern Europe', Annales Universitatis Scientiarum Budapestinensis De Rolando Eötvös Nominatae. Sectio Iuridica, Tomus XLV., Budapest, Faculty of Law, University of ELTE, pp. 101-120.

Kertész, I. and Stauber, J. (1996) 'Hungary is on the crime map of Europe', (Hungarian) Magyar Jog, 9, pp. 519-530.

Lawrence, W. S. (2005) 'The use and usefulness of criminology, 1751-2005: enlightened justice and its failures', The Annals of the American Academy, July, pp. 115-135.

Lelkes, O. (2003) 'Being outside, being inside', (Hungarian) Szociológiai Szemle, 4, pp. 88-106.

Łos, M. (1998) '"Virtual" Property and Post-Communist Globalization', Demokratizatsiya, The Journal of Post-Soviet Democratization, 1, pp. 77-86.

Łos, M. (1998) 'Post-Communist fear of crime and the commercialization of security', Theoretical Criminology 6(2), pp. 165-188.

Máté, M. (2004) 'Excluded population' (Hungarian) Belügyi Szemle, 2-3, pp. 177-183.

No. 115/223. (X. 28.) Parliamentary Resolution on the National Strategy for Social Crime Prevention

Papp, G. (2004) 'Crime and social exclusion' (Hungarian), in Poverty and SocialExclusion (Hungarian). Budapest, KSH, pp. 175-195.

Report on the social situation and the welfare system in Hungary (2003). Manuscript. (Hungarian)

Szalai, J. (2002) 'Certain issues of social exclusion in Hungary, in the turn of the millennium', (Hungarian) Szociológiai Szemle, 4, pp. 34-50.

Tauber, I. (2003) ' Change of the regime and crime. Criminals with deprived social status' (Hungarian) Belügyi Szemle, 7-8, pp. 80-97.

Tóth, I. Gy. (2004) 'Decomposition of income and inequalities in 2000-2003', (Hungarian), in T. Kolosi, I. Gy. Tóth and Gy. Vukovich (eds), Social Report - 2004 (Hungarian). Budapest, TÁRKI, pp. 75-95.

Young, J. (1999) The Exclusive Society. London, SAGE.

Young, J. (2002) 'Crime and social exclusion', in M. Maguire, R. Morgan and R. Reiner (eds), The Oxford Handbook of Criminology. Oxford, Oxford University Press, pp. 457-490.

- 140/141 -

Summary - 'Social Exclusion': a Prosperous Term in Contemporary Criminology; Social Exclusion and Crime in Central and Eastern Europe

The essay addresses two issues: the content of the notion of "social exclusion" and the relation between social exclusion and crime with a focus on post-Communist countries that acceded to the European Union on 1 May 2004.

In the first part of the study the author introduces the best-known positions in the Hungarian and international literature on the content of social exclusion as a sociological category, describes the most important measures that are taken against the social phenomenon of social exclusion in the European Union, and sums up criminological research findings on the interplay between social exclusion and crime.

In the second part the reader is informed about the characteristics of social exclusion before and after the transition to multi-party system in certain post-Communist countries of Central and Eastern Europe. A detailed discussion is given to the interconnection of social exclusion and crime in five post-Communist countries (the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Slovakia and Slovenia). Further topics raised are as follows: tendencies in the number of reported crime cases and the prison population in the above five states; the main research findings about the social welfare circumstances of known criminal offenders in Hungary.

The author expresses concern on that the countries examined show an alarming presence of signs of what is called "exclusive society." Among the criteria in question it is worth noting that the prison population is much higher in those countries than in the "old" EU member countries.

- 141/142 -

Resümee - "Soziale Ausgrenzung": ein Begriff in der Kriminologie der Gegenwart mit immer größerer Bedeutung; soziale Ausgrenzung und Kriminalität in Mittel- und Osteuropa

Die Studie beschäftigt sich mit zwei Fragenkomplexen. Der eine ist der Inhalt des Begriffes "soziale Ausgrenzung". Der zweite ist die Beziehung zwischen sozialer Ausgrenzung und Kriminalität, mit besonderem Blick auf die ehemaligen sozialistischen Staaten, die der Europäischen Union am 1. Mai 2004 beigetreten sind.

Im Rahmen des ersten Themengebietes legt die Studie diejenigen Standpunkte dar, die sich auf den Inhalt der sozialen Ausgrenzung als soziologischen Begriff beziehen und in der internationalen und ungarischen Fachliteratur als herrschend betrachtet werden. In diesem Teil kommt der Verfasser auf die wichtigsten Schritte des Kampfes der Europäischen Union zu sprechen, den diese gegen die soziale Ausgrenzung als gesellschaftliche Erscheinung führt. Danach gibt er einen Überblick über die wichtigsten kriminalistischen Forschungsergebnisse bezüglich des Zusammenhanges zwischen sozialer Ausgrenzung und Kriminalität.

Innerhalb des zweiten Themengebietes legt die Studie die Charakteristika der ehemaligen sozialistischen Länder Mittel- und Osteuropas aus der Sicht der sozialen Ausgrenzung vor und nach der Wende dar. Der Verfasser beschäftigt sich detailliert mit den Zusammenhängen zwischen sozialer Ausgrenzung und Kriminalität in fünf ehemaligen sozialistischen Staaten (Tschechische Republik, Ungarn, Polen, Slowakei und Slowenien). Im Laufe der Erörterungen gibt er den Verlauf der bekannt gewordenen Kriminalität und der Gefängnispopulation bekannt. Im Falle Ungarns stellt er darüber hinaus die wichtigsten Feststellungen der Untersuchungen bezüglich der sozialen Charakteristika der bekannt gewordenen Täter vor.

Die Schlussfolgerung des Verfassers ist, dass die Merkmale der ausgrenzenden Gesellschaft in den untersuchten Staaten in Besorgnis erregendem Maße präsent sind. Von den Merkmalen muss insbesondere der Anteil der Gefängnispopulation hervorgehoben werden, der im Vergleich zu den Zahlen in den alten Mitgliedsstaaten der Europäischen Union bedeutend höher liegt. ■

NOTES

* Revised version of the plenary session paper which was presented at the 5th Annual Conference of the European Society of Criminology, Krakow, Poland, August 31-September 3, 2005. The Hungarian text of the paper under publishing in the Jogtudományi Közlöny.

[1] Atkinson, 1998, p. 6.

[2] Szalai, 2002, p. 1.

[3] Bradley, 2001, p. 275.

[4] On the three levels see Bradley, 2001, p. 275.

[5] Young, 1999, p. 26.

[6] Young, 1999, p. 26.

[7] Young, 2004, p. 552.

[8] Havasi, 2002, p. 60.

[9] Lelkes, 2003, p. 89.

[10] Lelkes, 2003, p. 90.

[11] Lelkes, 2003, p. 91.

[12] See these indicators in the Supplement

[13] Lelkes, 2003, p. 92.

[14] Lelkes, 2003, p. 97.

[15] Lelkes, 2003, p. 92.

[16] See no. 28 of the Presidency conclusions - Laeken, 14 and 15 December 2001.

[17] Kerezsi, 2004.

[18] No 5. 1. of the National Strategy

[19] Young, 1999, p. 26.

[20] Gönczöl, 2002, p. 198.

[21] Gilinszkij, 2002, p. 84.

[22] Jung, 2003.

[23] Bradley, 2001, p. 276.

[24] Point no. 12 of the Recommendations (2003) 20E/24 September 2003

[25] Boers, 2003, p. 20.

[26] Los, 2002, p. 178.

[27] Gönczöl, 1991, p. 120.

[28] Sherman, 2005, p. 118.

[29] Young, 1998, p. 67.

[30] Krajewski, 2004, p. 26.

[31] Young, 1999, vi.

[32] E.g. Krajewski, 2004, p. 20.

[33] Havasi, 2002, p. 55; Ferge, 2002, p. 21.

[34] Ferge, 2002, p. 15.

[35] Ferge, 2002, p. 21.

[36] Ferge, 2002, p. 21.

[37] Report 2003, 11-12.

[38] Gábor-Szívós, 2004, p. 100-101.

[39] Máté, 2004, 2-3, p. 177.

[40] Source: Janky, 2004, p. 400-412.

[41] Tóth, 2004, p. 91.

[42] See Young, 2002, p. 459.

[43] See e.g. Ferge, 2002.

[44] Kertész-Stauber, 1996, p. 520.

[45] The National Strategy for Social Crime Prevention, 2003, p. 14.

[46] Tauber, 2003, p. 97.

[47] Gönczöl, 1996, p. 108-118.

[48] Krajewski, 2004, p. 23.

[49] Los, 1998, p. 78.

Lábjegyzetek:

[1] Department of Criminology, Telephone number: (36-1) 411-6521, e-mail: levaym@ajk.elte.hu