Hordósi Ágnes[1]: Possible Causes and Effects of Overcrowding in Hungary's Prison Population (JÁP, 2020/1., 69-83. o.)

I. Introduction

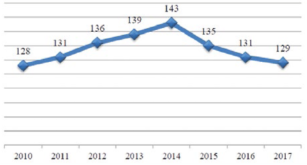

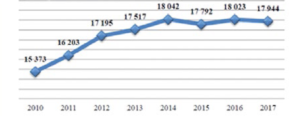

The over crowdedness of penal institutions is an evergreen problem, which, at the same time, is not a Hungarian peculiarity; the disproportion of the places and detainees in these institutions is well-known by many states. According to the latest statistical data, in 2017 penalty institutions were 129% overcrowded with 17 944 detainees. With regards to the previous years, this number was the highest in 2014 by 143% and 18 042 detainees.

Chart 1.: Degree of Average Fullness

(Source: Review of Hungarian Prison Statistics, 2018, 7.)

Chart 2.: Formation of the Annual Average Number of Detainees

(Source: Review of Hungarian Prison Statistics, 2018, 4.)

- 69/70 -

The over crowdedness of institutions is factual, it can have several reasons and its consequences can primarily be perceived in the institutions' everyday life.

II. Possible reasons of over crowdedness

1. The History of Detainee Rates

Hungary's strict criminal policy and the practice of law-enforcement coming from that together form the bases of the high rate of detainees - detainees per every 100 000 citizens. In a 2013 study written by Ferenc Nagy[1] states are listed into 5 categories along this line. In the next part of the study we are going to list European states based on the recent 2017 data.

So, according to the 2017 data, countries with a small rate of detainees - where this value is maximum 80 - are Slovenia (64), Finland (57), Denmark (59) Finland (74) Norway (74), Sweden (57), Croatia (78). Currently Germany (77) and the Netherlands (59) also belong to this category, however, these countries only belonged to the second group according to the 2013 data.

Countries with general rate - where this rate is between 81-100 - are for instance Switzerland (82), Belgium (94)[2] Greece (91) and Austria (94) according to the 2013 data.

The next group consists of countries with a high rate of detainees, where this rate is between 101-150. Such countries are Serbia (142), Romania (153) and Bulgaria (125).

The fourth group is given by those states where the detainee rate is very high, falls between 150-200. Hungary (184), Slovakia (188), Ukraine (167) and Poland (194) belong here for example.

The last group is formed by those countries where the rate exceeds 200, so it is extremely high, such as the Czech Republic (212) or Russia (421).[3]

We can establish that with regards to the rate of detainees an increasing tendency has emerged in most European states in the past decades, which can also be observed in the Hungarian data. In 1995 in Hungary the relevant data was 120, while in 2011-2012 it was already 173, and there was no decrease in the years between them, either. According to practitioners, the change in the rate of detainees is usually simultaneously connected to the rates of crimes. Based on international special literature this is far from the truth, the change in the rate of detainees does not only depend on the effect of only one element but it is affected by several reasons' interaction.[4]

- 70/71 -

As far as Nils Christie is concerned, social traditions, public opinion, the activity of law enforcement and political views also affect the formation of detainee rate.[5]

Therefore, external elements affecting this data contain significant political turns, as well as for instance changes of economic conditions. The influence of political culture can be justified by the mentioning a child murder's evaluation in the United Kingdom and in Norway. In the UK the case was followed by an open, widespread dispute and the government, taking advantage of it, introduced more strict rules. In opposition to this, in Norway this case was presented to the public in a more decent way, more experts investigating the underlying circumstances could present their viewpoint, and the reintegration of the perpetrator also appeared as a significant aim.[6]

The change of political situation, which also brings along economic and social changes led to the decrease of prison population in some Middle and Eastern-European countries such as in the Czech Republic due to amnesties applied in the 1980s and 1990s. Following that in a short period of time an opposing mechanism has been formed, partly due to the increase in crime and violent criminality. Still, statistics showed that, compared to the 1980s, the number of detainee decreased in Bulgaria, Romania and Hungary as well.[7] Therefore, the number of detainees is greatly influenced by politics as well, professional viewpoints are many times overruled by the circumstance that political decision makers aim at serving potential voters. Based on this, the effect of public opinion is also significant.[8]

Social-demographic factor also plays a role here. Migration, and the participation of ethnical and foreign minority also has to be mentioned. We have to highlight that among others, France also got in a fight with second and third generation migrants, which members often got to the edge of society. During the examination of the connection between economic situation and criminality contradicting results have been established. Certain investigations aimed at presenting that worsening economic situations have a direct effect on the population of prisons, their increase is stimulated without the crime rates increasing.[9]

Through the risk factors of committing crimes, family background and family relations may also affect the increase of detainee rate. Studies mainly highlight the responsibility of antisocial parents, conflicts and child abuse with regards to juvenile perpetrators, which is even more strengthened by the disadvantageous social-economic situation of such families.[10]

According to other viewpoints, we can justify it - based on international comparative analyses - that the high degree of detainee rate comes from the high

- 71/72 -

rate of social and economic inequality. According to Baechtold, we cannot miss the circumstance whether society has a punitive viewpoint or not, whether media shows unduly increased attention or political decision makers kind of overrate something.[11]

According to the Scandinavian viewpoint, in those states where there is no significant difference between various social classes, the detainee rate is low. However, where there is a noticeable difference among social classes, lower social classes are despised by members of the higher classes, and are being punished more easily.[12]

As an inner factor criminal policy, more precisely, criminal policy and the law enforcement system also affect this data. The increase in the rate of detainees can be connected to the tendency prevailing all over Europe according to which with regards to some pre-determined, primarily violent crimes penalty drastically improves and being excluded from conditional release is also increased.[13]

The role of law enforcement is also obvious in the increase of this rate with that courts more and more often impose imprisonment, also, convicted people spend a longer period of time in penal institutions. This latter circumstance can have various reasons as well. On the one hand, the punishment imposed can be long, on the other hand, people excluded from the possibility of conditional release is higher, also, the practice of ensuring conditional release on the side of law enforcement judges shows a more strict tendency.[14] However, we have to realize that the increasing number of imprisonment in itself is not an explanation to the increase of detainee rate, several of the above mentioned factors contribute to it.[15]

Besides the above mentioned two categories - external and internal reasons -other factors may also contribute to the rate of detainees. Such reason is the role of media and public opinion, as it was duly presented with the example above.[16] Switzerland has to be highlighted here, where the pressure of public opinion and the media can be felt in a way that these two factors also affect the practice of conditional release at courts. They do not want to take any risks with regards to ensuring conditional release to such people who may impose any threat to society.[17]

2. Overview

The radical increase of detainee rate is not only the characteristic of European states, but it also emerges in the USA, too, where the policy of massive imprisonment exists. In order to discover the route to the especially high rate of

- 72/73 -

detainees, we have to look back to the 1970s and 1980s, the root of this phenomenon can be found there.

On the one part, the base was given by the harsh policy of the 1970s, which considered criminals as "cancer cells" and prioritized rehabilitation and social reintegration, then the tendency continued with President Reagen's fight against drugs.[18] As for numbers, it meant that between 1973 and 1993, the number of detainees increased with 332%. By the 1990s, American criminologists started to realize that instead of treatment ideology, the highlight should be based on deterrence, and it was realized in frames of the neoclassic trend. The more and more strict criminal policy was also demanded by various social groups: organizations prioritizing the interests of victims achieved that the use of middle path became compulsory, after which the act of three strikes was also introduced. According to it, those suspects can be punished with life sentence, who commit certain types of crimes three different times.[19]

Due to the above mentioned circumstances, in the 1980s, the detainee rate was around 200, in 2008 it was 753, then according to the most recent sources 666, which is still relatively high.[20] So, the USA's restrictive policy stands on the three bases of the zero tolerance,[21] the three strikes and fair judgement, the increase of detainee rate traces back to the strict criminal policy emerging in frames of the fight against drugs. This weak practice also justifies for us that the formation of institutions and the massive imprisonment of perpetrators do not have a positive impact on committing crimes. Regardless of the change in the rate of detainees, institutions' places were filled all the time. According to a study in 2009, the population of prisons in the United States exceeds 2.3 million. This extremely high data also projected financial problems and made it clear for professionals that decreasing the number of prisoners cannot be delayed further. Based on some viewpoints, it has to be decreased at least by half in order to have an impact on the costs of execution.[22]

As Austin believes, the increase in the number of prisoners also comes from the growth of population, which brought the increase in committing crimes and the number of prisoners with it and the decrease only happened in the '90s. Still, the termination of conditional release increased, therefore, 2/3 of prisoners got back to the institutions due to its violation, also, due to legislations hindering conditional release, the period spent in penal institutions became longer by 40%. Farrington highlighted that for committing the same type of crime an American perpetrator is sentenced to a two times longer period of time than a British perpetrator, three times longer compared to a Canadian perpetrator, four times

- 73/74 -

longer than a Dutch one, five times longer than a Swedish one and five-ten times longer than a French one.[23] The reason behind is that in the United States the aim of punishment is basically and based on their viewpoints is still retaliation and not the reintegration of prisoners. This problem was also in the centre of investigations in the United States as well and according to some, with the help of the Norwegian scheme, it would be advisable to transfer to the system focusing on reintegration via changing their criminal policy.[24]

In the State of Indiana in the 2000s, a reform plan affecting national jurisprudence was formed, which aimed at increasing public safety, decreasing connected costs, forming adequate circumstances in prisons, as well as appropriately holding liable perpetrators. Hence, solving the problem of over crowdedness was not a specified aim here, still, in the background of forming expenses, the decrease of prison population was truly hidden. So this problem was finally realized, however, the change in criminal policy just did not happen.[25]

The Californian penitentiary system reached the critical point in 2006, still, they did not see the solution in focusing on the principle of reintegration, rather in the expansion of places.[26] This is not considered as a long-term solution by international and European law either, as the relief is only short-term, places are quickly filled by the system along the same criminal policy. However, they seem to agree in overseas as well in that the true solution lies in the change of criminal policy which occurrence cannot be seen yet.[27]

The JFA Institute conducts researches in order to form a more effective criminal justice, and its 2007 report highlighted that the massive number of imprisonment does not really affect the rate of crimes in reality, however, its costs are even higher. In order to decrease prisoners by half, they see the solution in the decrease of the period of imprisonment, as well as they highlight the application of alternative punishments, the assistance of the released prisoner and the decriminalization of crimes without victims.[28]

3. The Crucial Significance of Criminal Policy

For the formation of institutions' over crowdedness, the numerical situation of detainee rate cannot be blamed in itself. In Hungary, the well-known historical facts have also contributed to this, due to which the number of penalty institutions is not enough.

- 74/75 -

Furthermore, we can establish that data of over crowdedness rather depends on the criminal policy, which was separately listed above among inner factors due to its significance, forming the basis of the high rate of detainees, rather than the number of crimes committed. Since the transition based on the changes in the criminal policy, the tendency and willingness to be more restrictive is clear.[29] Based on the tendency prevailing these days, Act C of 2012 on the Criminal Code (CC) is built on the trio of justice - the appropriateness of the measure itself - and consistency.

In total, it means that continuing the policy of firm hand that started in 1998, the age of criminal responsibility has been decreased with regards to certain serious crimes, the compulsory application of actual life imprisonment has been ordered and the legal institutions of three strokes and middle path have been reintroduced. With regards to the system of sanctions, the act kept the dual system, at the same time, new sanctions have been introduced: confinement, prohibition from attending sport events, reparation work and the legal sanction of final blocking of access to electronic data. Along with the set direction of criminal policy, the maximum duration of a fixed-term imprisonment shall be twenty years, but for crimes committed in the framework of a criminal organization, if the perpetrator is a repeat offender or a habitual recidivist, as well as in the case of cumulative sentences or the merger of sentences, it shall be twenty-five years. Strict rules were introduced with regards to the eligibility for parole as well, those became excluded from this discount who are repeat offenders, or if their term of imprisonment is to be carried out in a penitentiary; who are repeat offenders with a history of violence; and persons sentenced for criminal offenses committed in the framework of a criminal organization. However, an opposing regulation was formed compared to the more strict directions of criminal policy with regards to release on parole from fixed-term imprisonment, as now its earliest date is adjusted to the perpetrator's previous records. As a main rule, if the detainee has served at least two-third of his penalty, he can be released on parole, with regards to recidivists this period is increased to three-fourth of the penalty. Even more favourable rules appear in the legal institution of half discount; if the sentence imposed is for less than five years of imprisonment, in cases deserving special consideration, the court may include a clause of eligibility for parole. In this case eligibility for parole can be applied, if at least half of the imprisonment has been served. There is a significant strengthening in the area of actual life imprisonment, as in this case the earliest date of release on parole shall be after serving twenty-five to forty years. Furthermore, the act rules on those cases when any eligibility for parole is precluded and cases of this exclusion is also determined.[30]

- 75/76 -

Having regard to that according to the statistical data[31] a vast majority of prison population is given by recidivists, we believe that the brief overview of special legal consequences referring to them is needed.

According to the act in effect there is no place for applying the rules of active regret - nor with regards to habitual recidivists[32] - and the maximum duration of a fixed-term imprisonment with regards to repeat offender - and a habitual recidivists - is twenty-five years,[33] a sentence of imprisonment imposed shall be carried out in a penitentiary, if imposed for a term of two years or more and the convicted person is a repeat offender,[34] in the case of eligibility for parole special consideration may not be applied for repeat offenders,[35] also, there is no legal possibility to the execution of a sentence of imprisonment, if the perpetrator is a repeat offender.[36] Repeat offenders may not be released on parole, if their term of imprisonment is to be carried out in a penitentiary, while repeat offenders with a history of violence may not be released on parole at all.[37]

89. § of the Criminal Code forms further legal consequences to special, repeat offenders and repeat offenders with a history of violence with regards to imposing penalty. With regards to special offenders and repeat offenders, the ceiling of the new crime's punishment increases with half in case of imprisonment, however, it cannot exceed twenty-five years. According to 82. § (1) of the criminal code, a punishment less severe than the punishment applicable can only be applied in special cases with regards to special offenders and repeat offenders. However, more serious legal consequences set in paragraph (1) cannot be applied, if the Special Part of this act orders to punish committing a crime as a special repeat offender as a more strict case of the crime.

Subsection (4) of Section 33 shall not apply to repeat offenders with a history of violence. This subsection expresses that if the criminal offense committed carries a maximum sentence of three years of imprisonment, the term of imprisonment may be substituted by custodial arrest, community service work, fine, prohibition to exercise professional activity, driving ban, prohibition from residing in a particular area, ban from visiting sport events or expulsion, or by any combination of these. Therefore, this regulation cannot be applied. The minimum sentence for violent crimes against the person, if committed by repeat offenders with a history of violence and if carrying a higher sentence, the maximum penalty prescribed for such crimes, if punishable by imprisonment, shall be doubled. If the maximum penalty increased as per the above would exceed twenty years, or if either of the said offenses carry a maximum sentence of life imprisonment, the perpetrator

- 76/77 -

in question must be sentenced to life imprisonment. The punishment of repeat offenders with a history of violence shall not be reduced under Subsection (1) of Section 82, or may only be reduced without limitation where this is permitted under the General Part of this Act. According to paragraph (1) of 95 § of the Criminal code, in the case of the merger of offenses for which imprisonment is imposed to be executed in different degrees, the merged sentences shall be carried out in the most severe degree. However, if the term of imprisonment imposed in a merger of sentences is for three years or more, or, in case of a repeat offender, two or more years, the merged sentence shall be carried out in the degree determined accordingly.

Among regulations emerging in frames of the more strict tendency, we have to mention regulations providing opportunity to apply actual life imprisonment, however, at the same time, we shall not disregard that from the point of view of over crowdedness the number of prisoners convicted to actual life imprisonment - 54 people according to the 2017 data[38] - is not at all significant.

When talking about dissuasive effects, it is still an accepted viewpoint that with regards to committing crimes the inevitability of crimes has a greater impact than the weight of crimes. The dissuasive effect of imposing a punishment, the realization of preventive aim cannot be measured today, having regard to at least that this effect prevails differently in various layers of society. Its crime prevention effect, which narrows down to that the convicted person cannot commit crimes during the period of execution or can only commit them along more difficult circumstances, cannot be denied.[39] Since today's legal execution is greatly imprisonment centred, the over crowdedness of institutions has been in the centre of attention for a long time, and it is all based on the attitude represented by the criminal policy.

III. The effect of over crowdedness

Therefore, over crowdedness can be regarded as the greatest problem of the penitentiary system, as it negatively affects all tasks and circumstances prevailing in frames of the system. Its negative effects affect all participants of the penitentiary legal relation. Due to the circumstances prisoners' "feeling of comfort" is hurt, during their time at the institutions everyday inconveniences prevail in a more decisive way, causing distress both among prisoners themselves as well as among prisoners and the prison staff. This problem affect the everyday life of prisoners from the point of view that participants become impersonal. This very general circumstance has its effect on extremely important areas as the quality of

- 77/78 -

prisoners' and professionals' cooperation greatly affects their activity's success, which final aim would be the successful reintegration. For professionals working in the system, the problem of over crowdedness also has a burden in a way that laic people identify the current situation with the incompetence of the organization. As the third group of burdens, we can consider international expectations which cannot be completely fulfilled due to the national circumstances, and the most significant problemin this area as well is the present situation of overcrowdedness.[40]

Reports written in the frame of the National Preventive Mechanism[41] system, which among others established the situation of over crowdedness in the Penal Institution of Somogy County and the Sátoraljaújhely Strict and Medium Regime Prison, also discovered anomalies in connection with over crowdedness with regards to other circumstances, which perfectly represent the negative effects of the phenomenon of over crowdedness in the everyday life.

At the time of the visit of the committee, in the Penal Institution of Somogy County out of 51 people employed at the Safety Department 40 had a direct contact with detainees. According to the viewpoint of the institute's psychologist, besides that this position is mentally extremely stressful, the personnel is overburdened, as they are too few to carry out all tasks. Therefore, the safe carrying out of duty tasks is done by an extreme labour input and high workload. According to the available data, a reintegration officer has to carry out his tasks connected to almost forty detainees. The report aimed to determine a system level problem having regard to that certain members of the personnel believe that they have to carry out administrative tasks rather than actually dealing with detainees. More additional positions exist in the system - such as disciplinary officer, investigating officer - which mean a further burden. This massive workload, as well as personal psychical problems emerging as the result of it and the lack of personnel psychologist have their effects on all parts of the institute's life. Violence among detainees is a circumstance existing in several institutions. Based on the opinion of a member of the personnel, the degree of aggression among detainees is different, so violent acts happen one to three times per week. He also noted that most detainees do not inform them on violent acts, so presumably the actual number of violent acts is much higher than the above mentioned numbers. According to a report of detainees, forms of aggression vary from mockery and the stealing of packages to humiliating, violent behaviour. In order to prevent such problems, the personnel reorganizes the personal structure of cells from time to time. According to detainee reports, they differentiate escaping, punishing

- 78/79 -

and cannibal cells among themselves. In the first one those detainees go who have been humiliated or hurt by others; 'punishing cells' are open for detainees who are considered as unmanageable by the personnel, so they most likely become part of such communities where they can experience violence. Under 'cannibal cells' we mean such cells which members are extremely dangerous, here as well we can talk about such unmanageable detainees who can be "regulated" by especially aggressive detainees.

The personnel also has the task to protect detainees from one another, so the personnel has to be qualified enough to cease the violence via adequately carrying out their tasks of maintaining and supervising order. They have to control any sign of disturbance and has to be adequately qualified and determined in order to intervene if it is necessary. According to detainee reports, it is obvious that the majority of violent acts committed among detainees is going to be undiscovered, just like it is typical that violence among one another happens with the knowledge and silent consent of the personnel.

Therefore, we can establish that there were worse conditions in institutions before with regards to over crowdedness - just think of the renovations happening in the past few years, in frames of which the separation of the toilet with a wall is important -, however, it is still there and causes tension among detainees, as well as among detainees and the personnel as well. The number of personnel is also inadequate compared to the number of detainees, so they cannot properly act against aggressive behaviour. The report also covered that the daytime employment and activity of detainees is not appropriate either, which can also cause problems together with the fact of over crowdedness. At the time of the visit, 73% of detainees did not participate in any employment; the reason of this low rate can be that the majority of them was in the institution in frames of pre-trial detention and these people cannot be obliged to work. Useful activity during the day has a great significance from the point of view of reintegration, however, based on what detainees say they are not informed on several possibilities at all and the use of the gym is not ensured to them, either. The personnel also confirmed that there is connection between the lack of programs and the violent behaviour of detainees.[42]

At the time of the visit to the Sátoraljaújhely Strict and Medium Regime Prison, there were 169 filled statuses who regularly had to do overtime in order to carry out their tasks properly. With regards to the violence among detainees, the personnel expressed that they cannot know what happens in the cells at nights, however, based on relevant reports misdemeanour assaults coming from beating, theft, sexual assault and blackmail can also happen, which origin is also connected to the phenomenon of over crowdedness, having regard to that the not enough number of personnel cannot have enough attention for detainees.[43]

- 79/80 -

IV. Instead of summary: The case of Varga contra Hungary

Based on the above mentioned circumstances going hand in hand with the overcrowded institutions and the everyday circumstance of detainees, the resulting effects were not avoided by the European Court of Human Rights (furthermore referred to as ECHR), either.

In the case of Varga contra Hungary being in progress in front of the ECHR, the over crowdedness of penal institutions in Hungary were in the centre of attention. The ECHR established that the lack of private sphere, the narrow spaces, the not separated toilets reach the level which form the bases of humiliating treatment. According to the justification, it cannot be harmonized with the Agreement if detainees have less than 3-4 m[2] of space for themselves and together with other circumstances it caused such a level of suffering for detainees which exceeded the necessary level connected to imprisonment. In this case the ECHR ruled a pilot judgement[44] - since they received 450 appeals connected to Hungary -, that is, if a problem appears on a system level in a state and they do not initiate changes upon infringement requests connected to individual cases, the court obliges the state to solve the problem during its identification.

With regards to that, Hungary got six months to prepare the solution regarding the problem of over crowdedness. As a result, 1600 more places were formed in the past few years, so over crowdedness decreased from 144% to 128%.

However, the Helsinki Committee had the viewpoint that establishing more penal institutions does not offer a real solution in itself, the modification of criminal policy is also justifiable.[45] As a result of the obligation expressed in this leading verdict of the court, in order to achieve that in line with the expectations of ECHR, in forms of effective legal remedy in Hungary, legal remedies connected to over crowdedness can be carried out in front of domestic forums, 22 § of Act CX of 2016 introduces the compensation procedure ensuring effective compensation in line with the legal impairment as a new legal institution, set in 10/A § of Act CCXL of 2013 on the execution of punishments, criminal measures, certain coercive measures and confinement for administrative offences.

In its resolution set on 23 November 2017, the ECHR accepted the measures that Hungary took in order to compensate over crowdedness in its penal institutions. Having regard to the legal institution of compensation, the Court suspended the examination of Hungarian cases until 31 August 2017. In the case of Domján contra Hungary the Court investigated the effectiveness of such legal remedy mechanisms. It established that preventive and compensation legal remedies can also be regarded as appropriate in order to remedy the violation of agreements coming from institutions' circumstances violating basic rights. Regarding the

- 80/81 -

daily amount of compensation that can be given the Court established that it was applied in line with the Court's practice. It noted that having regard to all that, the petitioner of the case and all other people being in the same situation are obliged to use these possibilities of legal remedy. The compensation case of Domján is in progress in Hungary, so his claim was regarded as premature by the Court, therefore it did not accept it and refused it due to obvious a lack of justification.[46] The old problem of over crowdedness in penal institutions is not fading away these days either, it is an existing problem which requires constant search for solutions. The rate of detainees according to their age[47] as well as data on repeated offenders show that without changing the criminal policy, the problem of over crowdedness won't show a different picture in the future, either.

Literature

• Besemer, Sytske-Farrington, David P. (2012): Intergenerational Transmission of Criminal Behaviour: Conviction Trajectories of Fathers and Their Children. In: European Journal of Criminology. SAGE Publications, Inc., Thousand Oaks.

• Bíró, Emese (2015): A fogvatartottak családi kapcsolatainak szerepe a bűnelkövetésben, a börtönélményben és a reintegrációban [The Role of Detaniees' Family Relations with Regards to Committing Crimes, Life in Prisons and Reintegration]. In: Szociológiai Tanulmányok [Social Studies]. 2015. vol. 2., MTA Társadalomtudományi Kutatóközpont, Budapest.

• Börtönstatisztikai Szemle [Review of Hungarian Prison Statistics]. 2018/1. szám. Igazságügyi Minisztérium, Budapest.

• Christie, Nils (1998): Bűnözés-kontroll Európában és Észak-Amerikában [Crime-control in Europe and North-America]. In: Kriminológiai Közlemények. Vol. 55. Magyar Kriminológiai Társaság, Budapest.

• Christie, Nils (1998): Drogkontroll-út a totalitárius viszonyok felé [Drug Controll Road Toward Totalitarian Relations]. In: Esély [Chance], 1998/6.szám. Hilscher Rezső Alapítvány, Budapest.

• Deltenre, Samuel-Mes, Eric (2004): Pre-trial Detention and the Overcrowding of Prisons in Belgium. In: European Journal of Crime, Criminal Law and Criminal Justice. 2004. vol. 12/4. Brill Publishers, Leiden.

• Domján v. Hungary. Application no. 5433/17. (Available at: https://hudoc.echr.coe.int/eng#(%22itemid%22:[%22001-179045%22]))

• Domokos, Andrea (2008): A büntetőpolitika változásai Magyarországon [The Changes of Criminal Policy in Hungary]. In: Jog és Állam [Law and State]. Book 11. Károli Gáspár Református Egyetem, Budapest.

- 81/82 -

• Dr. Tóth, Mihály (2018): A hazai börtönnépesség újabb kori alakulásának lehetséges okai és valószínű távlatai [Possible Reasons and Probable Perspectives of the Latest Situation of Hungary's Prison Population] (Available at: https://ujbtk.hu/dr-toth-mihaly-a-hazai-bortonnepesseg-ujabb-kori-alakulasanak-lehetseges-okai-es-valoszinu-tavlatai%C2%B9/, downloaded on: 10 January 2018.).

• Gál, Levente (2015): A munkaerő-piacon innen, börtönön túl [Labour Market and Prisons]. In: Szociológiai Tanulmányok [SocialStudies], 2015. vol. 2. MTA Társadalomtudományi Kutatóközpont, Budapest.

• Juhász, Zsuzsanna (2012): Az elöregedő börtönnépesség problémái [Problems of the Aging Prison Population]. In: Börtönügyi Szemle [Hungarian Prison Review], 2012. vol. 2. Igazságügyi Minisztérium, Budapest.

• Kertész, Imre (2001): Miért túlzsúfoltak a börtönök? [Why Are Pprisons Overcrowded?]. In: JURA. 2001. vol. 2. Pécsi Tudományegyetem, Pécs.

• Kirages, Drew (2015): Reentry Reform in Indiana: HEA 1006 and Its (Much Too Narrow) Focus on Prison Overcrowding. In: Indiana Law Review. 2015. vol. 49. IU Robert H. McKinney School of Law, Indianapolis.

• Király, Zoé Adrienn (2011): Az Egyesült Államok kriminálpolitikája és az amerikai szupermax börtönök [The Criminal Policy of the United States and American Supermax Prisons]. In: Börtönügyi Szemle [Hungarian Prison Review]. 2011. vol. 2. Igazságügyi Minisztérium, Budapest.

• Labutta, Emily (2017): The Prisoner as One of Us: Norwegian Wisdom for American Penal Practice. In: Emory International Law Review. 2017. vol. 31. Emory University, Atlanta.

• Nagy, Anita (2016): A túlzsúfoltság a büntetés-végrehajtási intézetekben, figyelemmel a nemzetközi szabályozásra [Overcrowdedness in Penal Institutions, Having Regard to the International Regulation]. In: Jogelméleti Szemle [Journal of Legal Theory]. 2016. vol. 1. ELTE-ÁJK, Budapest.

• Nagy, Ferenc (2013): Gondolatok a hosszú tartamú szabadságvesztésről és az európai börtönnépességről [Thoughts on Long Term Imprisonment and the European Prison Population]. In: Börtönügyi Szemle [Hungarian Prison Review]. 2013. vol. 1. Igazságügyi Minisztérium, Budapest.

• Nagy, Ferenc-Juhász, Zsuzsanna (2010): A fogvatartotti rátáról nemzetközi összehasonlításban [On the Deainee with Regards to International Comparison]. In. Börtönügyi Szemle [Hungarian Prison Review]. 2010. vol. 3. Igazságügyi Minisztérium, Budapest.

• Pallagi, Anikó (2014): Büntetőpolitika az új évszázad első éveiben [Criminal Policy in the First Few Years of the New Century] Doktori értekezés [Doctoral Dissertation]. Debreceni Egyetem, Debrecen.

• Palló, József (2015): Egyre jobban éget a seb... A túlzsúfoltság csökkentésének lehetséges útjai [The Scar is Burning More and More... Possible Ways of Reducing Overcrowdedness]. In: Börtönügyi Szemle [Hungarian Prison Review], 2015. vol 1. Igazságügyi Minisztérium, Budapest.

• Pitts, James M.A.-Griffin, Hayden O.-Johnson, Wesley W. (2014): Contemporary Prison Overcrowding: Short-term Fixes to a Perpetual Problem. In: Contemporary Justice Review. 2014. vol. 17. SAGE Publications, Inc., Thousand Oaks.

• Prisonstudies.org (2017): World Prison Brief Data | Europe (Available at: http://www.prisonstudies.org/map/europe. Downloaded on: 20 November 2017.).

- 82/83 -

• Prisonstudies.org (2017): World Prison Brief Data | United States of America (Available at: http://www.prisonstudies.org/country/united-states-america. Downloaded on: 20 November 2017.).

• Stelloh, Tim (2013): California's Great Prison Experiment. The State Faces a Deadline to Release Tens of Thousands of People from Prison. Is It Succeeding? In: The Nation. 2013. June 24/July 1. Katrina vanden Heuvel, New York.

• The Commissioner for Fundamental Rights' OPCAT National Preventive Mechanism Report in Case no. AJB-3865/2016. (Available at: https://www.ajbh.hu/opcat. Downloaded on: 20. November 2017.).

• The Commissioner for Fundamental Rights' OPCAT National Preventive Mechanism Report in Case no.AJB-679/2017. (Available at: https://www.ajbh.hu/opcat. Downloaded on: 20. November 2017.). ■

NOTES

[1] Nagy, F., 2013, 13-14.

[2] See further: Deltenre-Maes, 2004.

[3] Prisonstudies.org, 2017(a).

[4] Nagy-Juhász, 2010, 10.

[5] Christie, 1998, 153.

[6] Nagy-Juhász, 2010, 10.

[7] Nagy-Juhász, 2010, 9-10.

[8] Gál, 2015, 24.

[9] Nagy-Juhász, 2010, 11.

[10] Bíró, 2015, 74. (Cf.: Besemer-Farrington, 2012, 120-141.).

[11] Nagy-Juhász, 2010, 11.

[12] Nagy-Juhász, 2010, 13-15.

[13] Nagy-Juhász, 2010, 1.

[14] Review of Hungarian Prison Statistics, 2018.

[15] Tóth, 2018.

[16] Nagy-Juhász, 2010, 11.

[17] Juhász, 2012, 3-4.

[18] Cf.: Christie, 1998, 9-18.

[19] Király, 2011, 87-88.

[20] Prisonstudies.org, 2017(b).

[21] See further: Király, 2011, 88-89.

[22] Király, 2011, 85-101.

[23] Nagy-Juhász, 2010, 2-4.

[24] Labutta, 2017, 352.

[25] Kirages, 2015, 235-236.

[26] Stelloh, 2013, 31-34.

[27] Pitts-Griffin-Johnson, 2014, 130-137.

[28] Nagy-Juhász, 2010, 3-4.

[29] See: Domokos, 2008.

[30] Pallagi, 2014, 156-167.

[31] Review of Hungarian Prison Statistics, 2018.

[32] CC. 29. § paragraph (3).

[33] CC. 36. §

[34] CC. 37. § paragraph (3) point ba).

[35] CC. 38. § paragraph (3).

[36] CC. 86. § paragraph (1) point a).

[37] CC. 38. § paragraph (4).

[38] See further: Review of Hungarian Prison Statistics, 2018.

[39] Kertész, 2001, 53.

[40] Pallo, 2015, 18-19.

[41] Hungary ratified the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment with decree law 3 of 1988, then the optional protocol was presented by Act CXLIII of 2011. In order to fulfil its obligations they established the National Preventive Mechanism (NPM) in frames of the office of Commissioner for Fundamental Rights. Its aim is that together with its controlling activity it contributes to the realization of the prohibition of cruel, inhuman or humiliating punishment or treatment. See further: website of the Commissioner for Fundamental Rights (see at: ajbh.hu).

[42] The Commissioner for Fundamental Rights' OPCAT National Preventive Mechanism Report in Case no. AJB-3865/2016. Pp. 22-24.

[43] The Commissioner for Fundamental Rights' OPCAT National Preventive Mechanism Report in Case no. AJB-679/2017. Pp. 15-18.

[44] The pilot judgement obliges states to form such domestic legal remedy possibilities which provide adequate closure for cases not discussed by the ECHR, and is in line with its judgement.

[45] Nagy, A., 2016, 70-73.

[46] Domján v. Hungary (application no. 5433/17).

[47] See at: Review of Hungarian Prison Statistics, 2018.

Lábjegyzetek:

[1] A szerző sajtótitkár, PhD hallgató, Győri Törvényszék, SZE Deák Ferenc Állam- és Jogtudományi Kar.