Réka Kovács[1]: Health professionals on the move: analysing Brexit's influence on diploma recognition and the employment of health care workers (Annales, 2023., 163-188. o.)

https://doi.org/10.56749/annales.elteajk.2023.lxii.10.163

Abstract

In the area of healthcare Britain has long relied on foreign labour, including EEA professionals benefiting from the automatic recognition of their qualifications based on EU law. As a result of the negotiations on future relationship after Brexit, the previous regime for the recognition of professional qualifications has been completely abolished, and a solution of possible agreements on the initiative of professional organisations has been adopted. The UK however introduced measures unilaterally to maintain previous EU rules concerning the recognition of qualifications, and facilitated the inflow of foreign healthcare staff by easier immigration rules for professionals with NHS or adult social care job offer. The article examines - based on the analysis of the data of the British General Medical Council and the Nursing and Midwifery Council and of Hungarian authorities - how the 2016 British referendum affected the UK health sector as for the health workforce concerned.

Keywords: health workforce, mobility, Brexit, recognition of qualifications

I. Introduction

The historic decision by the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland to exit the European Union, commonly known as Brexit, marked a pivotal moment in the European Union's history. On the 23rd of June 2016, the UK population cast their votes, the majority in favour of leaving the EU, setting in motion a complex and protracted process that culminated on the 31st of January 2020, when the UK officially severed its ties with the EU, being the first country to make use of the possibility provided by Article 50 of the Lisbon Treaty. This decision, shaped by various political,

- 163/164 -

economic, and social factors, had far-reaching consequences, significantly impacting the dynamics of relations between the EU and UK.

One of the most contentious issues that underscored the referendum leading up to Brexit was the substantial presence of foreign workers, particularly those from Central and Eastern Europe, within the UK.[1] Prime Minister David Cameron's declaration at the EU summit in February 2016, in which he emphasised the necessity for the UK to distance itself from the principle of "ever closer integration" within the EU, served as a critical turning point. He expressed a firm commitment to ensure that British taxpayers' money would no longer be utilised without constraints to fund the social benefits of EU citizens, particularly those from Central and Eastern Europe, who were actively contributing to the British workforce.[2]

The United Kingdom has historically been a preferred destination for healthcare professionals due to a combination of factors, including competitive salaries, state-of-the-art medical technology, ample opportunities for professional growth and development, and the relative ease of communication thanks to English being the most widely used language. These factors, together with the strong demand for healthcare services, made the UK an attractive proposition for healthcare workers, including those from the European Union. However, as the UK formally separated from the EU, several uncertainties arose, reshaping the landscape of healthcare employment in the region.

The healthcare labour market within the EU has faced severe challenges in the past years. The European Union's 2012 Action Plan for Health Workforce had already foreseen a significant shortage of healthcare professionals, projecting a deficit of one million workers by the year 2020.[3] In addition to the existing challenges, the COVID-19 pandemic has had a profound impact on the health workforce. Healthcare professionals worldwide have faced increased workloads and burnout due to the surge in COVID-19 cases, extended working hours, staff shortages and the emotional toll of the pandemic.

At present, UK media are abuzz with the news of healthcare professionals in the UK embarking on strikes, which were triggered by the government's pay declaration in July 2022 and have endured through the entirety of Autumn 2023. The strikes were initiated due to concerns among some NHS workers and their trade unions about the

- 164/165 -

adequacy of their pay increases, as they believed they did not keep pace with the rising cost of living. Additionally, health workers sought to improve patient safety, which they believed was compromised by inadequate staffing levels and staff burnout. The dispute also stemmed from concerns that, without better pay, it would be challenging to attract and retain healthcare professionals, exacerbating existing staffing issues.[4]

This article delves into the multifaceted ramifications of Brexit on the UK's healthcare sector and its ability to attract, retain and ensure a skilled and diverse healthcare workforce in the post-Brexit era. It examines the post-Brexit regulatory framework for the recognition of professional qualifications and the impact of Brexit on the willingness of the EEA and Hungarian healthcare workforce to work in the UK, based on data from the British professional chambers and the National Directorate General for Hospitals of Hungary (OKFŐ).

II. EU and post-EU rules regulating the mutual recognition of professional qualifications

1. Secondary legislation of the EU: Directive 2005/36/EC - main rules concerning health professionals

To facilitate the freedom of establishment and the freedom to provide services, the European Parliament and the Council adopted Directive 2005/36/EC on the mutual recognition of professional qualifications on 7 September 2005.[5] The Directive applies to nationals of a Member State wishing to pursue a regulated profession in a Member State other than that in which they obtained their professional qualifications, on either a self-employed or employed basis. It only applies to regulated professions, meaning a professional activity or group of professional activities, access to which, the pursuit of which, or one of the modes of pursuit of which is subject to the possession of specific professional qualifications. According to the provisions of the Directive, the recognition of professional qualifications by the host Member State shall allow beneficiaries to gain access in that Member State to the same profession as that for which they are qualified

- 165/166 -

in the home Member State and to pursue it in the host Member State under the same conditions as its nationals.[6] It includes that the professional not only possesses the diploma but fulfils all the necessary requirements of the home country (e. g. professional experience, membership of the chamber, etc.).

The Directive retained the framework for health professions that had been evolving since the 1970s, allowing automatic recognition of qualifications between Member States on the basis of common minimum training requirements for certain health professions. In fact, under Article 21 of the Directive, each Member State recognises evidence of formal qualifications in general medical practice, specialised medicine, nursing, dentistry, specialised dental practice, midwifery and pharmacy listed in Annex V, which satisfy the minimum training requirements laid down in the respective Articles of the Directive and, for the purposes of access to and pursuit of the professional activities, gives such evidence the same effect on its territory as the evidence of formal qualifications which it itself issues.

Regarding the recognition of health qualifications not covered by automatic recognition, the main rule of the Directive applies: under the so-called general system of recognition, the authorities of the host Member State will examine the professional content of the training received and will consider it as equivalent to the training required under their national law, provided that it attests to a level of professional qualification at least equivalent to the lower level of qualification required in their country, immediately preceding the level of professional qualification described in Article 11.[7] Where necessary, the authority may lay down compensatory measures to remedy the substantial shortcomings identified in the Directive, namely a maximum of three years' adaptation period or an aptitude test.[8]

It is important to mention the European Professional Card, introduced by the comprehensive amendment of Directive 2005/36/EC (2013/55/EC), to further facilitate mobility in certain professions via the adoption of implementing acts. The introduction of a European Professional Card for a particular profession is only possible if there is significant mobility or potential for significant mobility in the profession concerned; there is sufficient interest expressed by the relevant stakeholders; and the profession or the education and training geared to the pursuit of the profession is regulated in a significant number of Member States.[9] Until now, this possibility - meaning a simpler alternative for a recognition procedure to be initiated electronically in the sending country - has only been introduced for five professions, three of which are health professions - nursing, pharmacy and physiotherapy. Although experience in Hungary and Europe shows that the European Professional Card has been less

- 166/167 -

widespread in the health professions subject to automatic recognition (pharmacists, nurses),[10] and has not yet been introduced for doctors, it can possibly become a serious alternative to the previous procedures.

2. Rules of the Withdrawal Agreement on the regime on professional qualifications

The Withdrawal Agreement,[11] which was adopted on 17 October 2019 following lengthy negotiations and entered into force on 1 February 2020, provided for the continuation of the previous regulatory regime and the retention of acquired rights during the transitional period. According to Article 27 of the Agreement, the legal effects of the recognition of professional qualifications acquired by EU or UK nationals and their family members before the end of the transitional period by the host or host country of employment under Title III of Directive 2005/36/EC will continue to apply in that country, including the right to practise their profession on equal terms with nationals. Article 28 contains a provision on pending proceedings, stipulating that proceedings initiated during the transitional period would continue to be governed by EU law, even after the exit of the UK from the EU. Finally, Article 29 introduced a cooperation obligation to facilitate the application of Article 28 and allowed the United Kingdom to use the Internal Market Information System for procedures under Article 4d[12] for a period not exceeding nine months from the end of the transitional period.

3. EU-UK Trade and Cooperation Agreement - new rules on the recognition of qualifications

a) Regulatory solution

After nine months of intensive negotiations, the Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA), governing the UK's future relations with the EU, was finally agreed on 24 December 2020, days before the end of the transition period.[13] In view of the expiry of

- 167/168 -

the transitional period, the Agreement was provisionally applied from 1 January 2021 by Council Decision.[14]

The new agreement did not maintain the EU system of mutual recognition of professional qualifications, but introduced in Article 158 a framework under which professional bodies and authorities can develop and submit to the Partnership Council joint recommendations on the recognition of professional qualifications, demonstrating its economic value and the compatibility of regulations. This will therefore allow for agreements on the recognition of professional qualifications between the UK and EEA Member States on a case-by-case, profession-specific basis, modelled on the free trade agreement with Canada, CETA, where cooperation between professional bodies results in such a proposal. To assist, Annex 24 provides guidelines for professional organisations on the recommendations to be submitted to the Partnership Council.

It is interesting to compare the solution used by the UK-EU Trade and Cooperation Agreement and the Canada-EU Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA) on the recognition of professional qualifications. CETA contains a whole Chapter on the mutual recognition of qualifications. As having no previous common history of the recognition of professional qualifications between the contractual parties, Chapter eleven of CETA provides more specific provisions, including definitions for terms such as "jurisdiction", "negotiating entity", "professional experience", "professional qualifications", "relevant authority", and "regulated profession", describes the scope and objective and it also gives a more detailed description of the negotiation procedure of a Mutual Recognition Agreement (MRA) in the respective Joint Committee (MRA Committee). However, it seems to be evident that the main elements from the CETA agreement were taken over, including that joint recommendations have to be developed for the respective body (CETA established a special Committee, while the UK-EU Agreement uses the Partnership Council), having taken into account the economic value (explained in more details in CETA) of such an agreement and the compatibility of the respective regimes.

It is important to refer to the footnote to Article 158(1) of the UK-EU Agreement (there is no such footnote in CETA), according to which the Parties may conclude an agreement between themselves laying down conditions and requirements other than those provided for in this Article. This provision, according to the majority view,[15] allows the UK and the Member States to settle their ideas on the recognition of

- 168/169 -

professional qualifications in bilateral agreements, which, if subsequently agreed at EU level for certain professions, could lead to a complex picture in the systems of recognition of diplomas.[16]

b) Evaluation and current developments

Based on the information available on the negotiations, it seems that the resulting regulation is mainly closer to the position of the European Union.[17] Statements by UK government politicians[18] suggest that the UK would have preferred to include more ambitious provisions in the agreement. A complex solution was proposed which, while retaining regulatory autonomy, would still provide for a joint assessment mechanism whereby EU and UK regulators would have the possibility to reject candidates with insufficient experience. According to the UK Trade Policy Observatory,[19] the agreement is disappointing and half-baked. They believe that little progress can be expected from a solution such as CETA, given that, in the three years since the Canadian FTA came into force, no recognition agreements have been concluded.

It seems however that some progress has been made from the UK side, as Leo Docherty, Parliamentary Under-Secretary (Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office) announced on the 29th of March 2023 in the UK Parliament that the UK government is actively supporting regulators and professional bodies proposing professional qualifications for recognition through the TCA framework by technical guidance published in May 2021 on GOV.UK and by launching a Recognition Arrangements Grant Programme to support regulators' financial costs to agree recognition arrangements in August 2022.[20]

The most recent developments concern the adoption of the first joint recommendation, pursuant to Article 158 of the TCA. The first proposal on the recognition of architects' qualifications was submitted to the Partnership Council on 3 October 2022 by professional bodies from the EU and the United Kingdom. The

- 169/170 -

Partnership Council is due to review the consistency of the joint recommendation with the rules on services and investment of the TCA.[21] The first discussions took place on the recommendation at the Services, Investment and Digital Trade Specialised Committee on 20 October 2022; however, according to the minutes of this meeting, no real discussion took place on the substance.[22] The developments are rather slow, as the Services, Investment and Digital Trade Specialised Committee convened its next meeting a year later, the 6th of October, the report of which is not yet available, but, according to the agenda, the issue was planned to be discussed further. It is worth noting that the first MRA under CETA will be adopted in the near future, and the profession is the same, architects. According to the Report of the Committee on the Mutual Recognition of Professional Qualifications to the Joint Committee on 10th of March 2022, the negotiations have been concluded after nine rounds, and the text will be finalised and formally adopted at a CETA MRA Joint Committee meeting to be scheduled, if possible, in the second half of that year.[23] The process at the end has slowed down somewhat, as the Proposal for a Draft Decision of the Joint Committee is scheduled for 12th of October 2023,[24] but it seems that the first MRA will be adopted in the very near future, showing that there is hope to provide results in the frame of the TCA as well. However, t cannot be seen yet if there will be a similar initiative concerning any of the health professions in the near future.

- 170/171 -

III. Rules on employment of foreign health professionals in the UK after Brexit

1. Special visa arrangements for health professionals

From 1 January 2021, workers from EEA and non-EEA countries are subject to the same immigration rules, namely a so-called points-based immigration system.

To facilitate international recruitment into the health sector for employers and workers, the UK government is offering an accelerated, exceptional opportunity for the majority of health professionals with a job offer in the NHS (National Health Service) and qualified social workers coming into adult social care (Health and Care Worker Visa[25]). The visa is not only designed to help address the health professional crisis within the UK healthcare sector by offering an attractive route for foreign nationals to work in the UK and to be joined by close family members, but also offers the potential to settle permanently in the UK in the long term. According to the information provided on the government website, eligible and successful applicants can work in the UK for a period of up to five years and can apply to extend their visa as many time as they like, provided they remain eligible, and after 5 years they can also apply to settle permanently in the UK (also known as 'indefinite leave to remain'). Successful visa applicants in this category are also exempt from the health immigration surcharge.[26] In early 2023, the UK government announced £15 million in funding to help health and care sector employers hire from overseas under the Health and Care worker route.[27]

2. Standstill provisions concerning diploma recognitions

As far as the recognition of qualifications is concerned, the government, according to the European Qualifications (Health and Social Care Professions) (Amendment etc.) (EU Exit) Regulations (2019/593),[28] has decided to recognise health care diplomas

- 171/172 -

obtained in the EEA and Switzerland that are subject to automatic recognition under a transitional regime unilaterally for a further two years after the end of the transitional period, under almost the same rules.[29] In addition, Regulation 14 of the EU Exit Regulations obliges the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care to review the operation of the provisions concerned after the end of the period of two years beginning with the day on which those Regulations came into force (meaning January 2023) and provide a report on the findings within 6 months of the start date.

The UK government issued a written Call for Evidence on 25 August 2020, which ran until 23 October 2020,[30] in order to discuss and review the UK's approach to the recognition of professional qualifications from other countries with regulators, trade associations, other organisations and academics from all parts of the UK. The consultation process has served as an important input to the revision of the registration requirements for EEA qualified practitioners for the period after January 2023.[31]

The government conducted the analysis placed on it as a legal duty by Regulation 14 of the EU Exit Regulations and published its findings in July 2023.[32] The report includes a data analysis, the results of the stakeholder consultation and also some wider considerations. According to the analysis, data demonstrated a decline in the number of applications from EEA or Swiss-qualified professionals in 2021 and 2022 compared to 2019, likely influenced by the COVID-19 pandemic. However, there was a notable increase from Q1 2021. While it is challenging to project future application numbers due to the volatility linked to pandemic-related deferred applications, the upward trend between 2021 and 2022 reinforces the importance of standstill provisions in maintaining a simplified application process and mitigating potential negative impacts on EEA-qualified healthcare professional inflow, according to the governmental considerations. Stakeholders indicated support for the short-term retention of standstill provisions, thereby preventing operational challenges for EEA-qualified applicants in the UK. Stakeholders generally favoured maintaining these provisions for now, with possible re-evaluation in the future. Regulators also suggested additional legislative changes, such as extending the provisions to Gibraltese qualifications and enhancing

- 172/173 -

flexibility in accepting European qualifications under specific circumstances. According to them, extending the standstill provisions will allow further exploration of these legislative improvements over the next 2 to 3 years. Taking also wider considerations into account, such as the need for amending, revoking or replacing retained EU law, a wider regulatory reform and some issues relating to Northern Ireland, the government decided on retaining the standstill provisions for a temporary period of 5 years, in order to support the department's ambition to attract and recruit overseas healthcare professionals, without introducing complex and burdensome registration routes. The Department of Health and Social Care is taking on some additional responsibilities: it will explore the legislative improvements suggested by regulators in the consultation and the viability of delivery between 2024 and 2026, determine what is required to establish emergency cross-border working arrangements on the island of Ireland and also determine whether to carry out a further review of the operation of the standstill provisions in 5 years' time, as part of the wider programme of regulatory reform.[33]

3. Bilateral agreements - Switzerland

Collaboration between Switzerland and the United Kingdom regarding the mutual recognition of professional qualifications commenced more than two decades ago, primarily under the Swiss-EU Agreement on the Free Movement of Persons (AFMP).[34] This agreement ruled on the extension of Directive 2005/36/EC to Switzerland, including the rules on the mutual recognition of healthcare diplomas. According to the press release of the Swiss Ministry of Economics, Education and Research,[35] following the United Kingdom's departure from the European Union and by extending the AFMP, a Swiss-UK bilateral agreement was established to safeguard the rights of their citizens, allowing for a transitional period until the end of 2024. They also report that, in preparation for a robust framework for the mutual recognition of professional qualifications from 2025 onward, Switzerland and the United Kingdom have recently

- 173/174 -

forged a new agreement,[36] poised for public consultation in the near future. The agreement awaits ratification by the Swiss Parliament, a process expected to take place in 2024. The new agreement concerns regulated professional activities, and has no specific provisions upholding the previous rules on the automatic recognition of healthcare qualifications; special privileges (e.g. automatic recognition) could be established either through mutual recognition arrangements (MRAs) or by adding annexes to the current agreement. These two options furnish the contracting parties with the essential tools to adjust the system as necessary over time.

IV. Measurement of health professional mobility

In order to examine changes in the mobility of health professionals in the light of Brexit, it is important to look at what data can help us identify trends. Given that health professionals can accept job offers anywhere and at any time, using their right to free movement even in the framework of circular migration,[37] there are no mandatory statistics on their work abroad, and we can only estimate their movements. We can use the statistics on those requesting certain certificates required by Directive 2005/36/EC (home country information), as well as on recognition decisions, operational registries (host country information) and international data collections.

Passive intention to work abroad[38] is shown by the different certificates issued by the home country on the basis of the provisions of Directive 2005/36/EC of the European Parliament and the Council on the mutual recognition of professional qualifications as implemented by national legislation. Directive 2005/36/EC makes it possible for Member States authorities to require those who want their qualifications recognised to receive different certificates, to be issued by the authority of the country of establishment.[39] Since it is not possible to know whether the applicants will eventually work abroad, we therefore consider them as attesting a passive intention to work. As in most cases these certificates are requested for employment abroad, those who wish to do so usually ask the authorities to issue one or more of the certificates.

- 174/175 -

The certificates can attest compliance, acquired rights or the good standing/character of the person concerned. The certificate of conformity/compliance confirms that the training led to the qualification satisfies the minimum training requirements laid down in the relevant Articles (24, 31, 34, 40-41, 44) of the Directive in the case of professions under automatic recognition. It is necessary if the training started before a country acceded the EU (and training did not have to be conformant), or the name of the training changed (so cannot be recognised among those listed in the respective Annex of the Directive). The certificate of acquired rights - based on Articles 23, 27, 30, 33, 37 and 43 of the Directive in the case of health professions - issued for those, who qualified before the reference date set out in Annex V to the Directive and whose qualification does not meet the minimum requirements for training, and in other specific situations provided for in the Directive, attests as a main rule (with certain exceptions) that the applicant has been effectively and lawfully engaged in the relevant healthcare activity for at least three consecutive years during the five years preceding the award of the certificate. A third certificate is often required from the foreign authorities; it is the so-called good standing certificate, which is proof that the professional is of good character or repute or has not been declared bankrupt, or is not under suspension or prohibition in the pursuit of the profession because of serious professional misconduct or a criminal offence.[40]

The provisions of the Decree C of 2001 on the recognition of foreign certificates and diplomas for doctors, dentists, (general) nurses, midwives and pharmacists have implemented the above possibilities into Hungarian law. Certificates of acquired rights[41] are issued under Article 60/B of the Act on the Recognition of Qualifications, while Certificates of Conformity[42] are issued under Article 60/C of the same act. Certificates of good standing can be issued under Article 110/A of Act CLIV of 1997 on Health Care for persons with any kind of health professional qualification.

More information on working abroad can be found in the host country's statistics on recognition decisions, as well as in the European Commission's database on official decisions on the recognition of professional qualifications.[43] The recognition of a diploma abroad already reflects a so-called active intention to work,[44] since the person concerned has not only requested the official certificate(s) from the authorities

- 175/176 -

of the sending country, but has also initiated the procedure for the recognition of the professional qualification. Similarly useful information on the country of qualification can be found in each country's operational registers, although even here we do not know whether the licensed professional is actively practising. However, these registers might not be accessible, but reports from their data are often available.

It is also very important to mention the different international data collections, the most known and used of which is the Joint Questionnaire (JQ) on non-monetary health care statistics. The data collection covers the Member States of the European Union, the OECD and the WHO European Region. To improve the monitoring of international health workforce migration through the collection of a minimum dataset that is relevant to both source and destination countries, the JQ was complemented in 2015 by the Health Workforce Migration module, for which Member States provided data on the stock of doctors and nurses abroad and annual inflows back to 2000. The data collection focuses mainly on the place of training (defined as the place of first qualification) and collects immigration data from destination countries by all countries of origin, based on the available national sources (e.g., professional registries, specific surveys of health personnel), according to the concept of 'practising' (i.e. healthcare professionals directly providing services to patients). If not possible, the data can be reported for professionally active physicians or physicians licensed to practise.[45] The legal basis for this data collection in the EU is Regulation (EC) No 1338/2008 of the European Parliament and of the Council on Community statistics on public health and health and safety at work, implemented by Commission Regulation (EU) 2022/2294 as regards statistics on healthcare facilities, healthcare human resources and healthcare utilisation. The latter legislative measure encompasses data categories for which compulsory collection has been in effect since either 2021 or 2023, it's worth emphasising that the provision of migration data is not obligatory. Derogations to the requirements of the legislation are specified in Commission Implementing Decision (EU) 2022/2306 (5) granting derogations to certain Member States with respect to the transmission of statistics pursuant to Regulation (EC) No 1338/2008 of the European Parliament and of the Council, as regards statistics on healthcare facilities, healthcare human resources and healthcare utilisation.[46]

- 176/177 -

V. Employment of health workers in the UK after Brexit

In the wake of the Brexit referendum, there has been much writing about how the UK healthcare system will be affected by the possible departure of healthcare professionals. For example, a 2017 qualitative study[47] found that although the majority of doctors felt they would not be forced to leave due to staff shortages, some were concerned about the uncertainty caused by Brexit. Perhaps more significantly, doctors said the Brexit vote made them feel unwelcome and undervalued in the UK. It is worth examining whether the available data support or refute these fears.

1. UK as a receiving country - examining data on EEA immigrants, with special focus on Hungarian-trained professionals

a) Analysis of data on doctors

In order to analyse the developments of UK health workforce we don't even need to dig into the international data collections, but we are served by the yearly reports of the British Medical Council (GMC) on the data available for qualified doctors from the European Economic Area (including Switzerland for the purposes of analysis). The latest study published in November 2021[48] on the EEA workforce - forming 8.7% of the total medical workforce, including 5% of general practitioners and 13.4% of specialists[49] - introduces the annual number of people entering and leaving the UK healthcare system, the proportion of those entering from EEA countries in aggregate and by specialisation, and their employment in each part of the country, and also analyses recent trends.

Concerning the number of EEA doctors on the register, the report displays how the proportion of those with a licence to practise has been evolving in the last decade. It concludes that while the number of EEA doctors has been decreasing as a proportion of those registered - as graduates from the UK and outside the EEA have grown at faster rates than EEA graduates -, their absolute number has increased slightly since the 2016 referendum.

- 177/178 -

Of particular interest to us is the graph[50] in the study showing the regional breakdown of EEA doctors with a licence. Among the trends is noteworthy - and the report also emphasises it in its conclusions - that there has been a change in the mix of doctors joining UK registers from the EEA in recent years; in 2021 the number of graduates from Central and Eastern Europe and Baltic countries exceeded those from North-western Europe for the fourth year in succession. According to the data presented in the report, the number of North-western Europe doctors is roughly constant, Southern Europe reached the lowest point in 2018 and a considerable increase can be observed since then. The most significant surge, from 2016 onward, has become evident in the new Member States encompassing Central Europe, Eastern Europe, and the Baltic countries (namely Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Romania and Slovakia) and in Bulgaria from Southern Europe. Another interesting figure[51] which concerns our region is that while more than half (5,563) of the more than 10,000 EEA licensed specialists came from four countries, Ireland, Greece, Italy and Germany, one sixth of all lower-ranked and locally employed (SAS - Specialty and Associate Specialist or LE - Locally Employed) doctors came from Romania, and the incidence is higher than average for the other CEE countries as well. It can also be seen that Hungary ranks tenth among the countries of origin; the first ten includes five countries from the CEE region (Romania, Poland, Czechia, Bulgaria and Hungary).

To examine the wider perspective, it is useful to look at the GMC report on the whole medical workforce from 2022,[52] which highlights a dramatic increase in international medical graduates (IMGs) practicing in the country. The number of UK medical graduates joining the workforce rose by only 2% from 2017, while IMGs increased by 121%. According to the report's statement, it has a real relevance concerning the Brexit vote, as the growing trend of IMG doctors joining has increased significantly after 2016, while the joiners from EEA countries has already more or less stabilised at a decreased level since 2015. This heavy reliance on IMGs presents challenges too, not only because the inflow is unpredictable, but data indicate that IMGs leave the UK workforce at a higher rate. There has been an overall increase in the number of doctors joining the workforce by around 17% over the last five years. According to the report, there are however huge variations in workforce growth across different categories, including trainees, GPs, specialists, SAS, and LE doctors. The number of GPs has grown by 7%, and specialists by 11% with variations among specialties, while the number of SAS and LE doctors has surged by 40%. This increase is attributed to the rising demand for healthcare services, leading to more opportunities

- 178/179 -

for SAS and LE doctor recruitment, where IMGs have played a valuable role. This trend is expected to continue.

To conclude, according to the report on the EEA workforce, the slow and steady increase in the number of licensed EEA graduates in the UK since the EU exit referendum suggests that the results of the referendum itself have not affected the number of EEA doctors who want to come and work in the UK. However, on the other hand, in order to cover the increasing demand for a medical workforce in the UK, the inflow of IMG doctors provides the most prominent contribution, which trend has accelerated since 2016 and showing an obvious connection to the Brexit vote. Concerning the EEA workforce, the report is also uncertain as to how the end of the standstill period - which has now been postponed - will affect the number of EEA graduates coming to the UK.

b) Data on nurses

The Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC) issues an annual report on healthcare professionals, which includes nurses, midwives, and nursing assistants registered with the council. The latest report covers the period from April 1 2022, to March 31 2023, and also provides insights into trends over the past five years.[53] According to the report, the number of registered nurses, midwives and nursing associates practicing in the UK has reached a new record high, totalling 788,638 by 2023. The year 2022-2023 marked a significant milestone, as it witnessed the highest number of new entrants joining the register in a single year, with over 52,000 individuals. Among these, 27,142 were newly educated professionals in the UK, while 25,006 professionals received their education from various parts of the world, primarily outside of Europe. In parallel to this significant increase, however, the number of EEA nationals has been steadily decreasing over the last seven years, starting from 2016[54] (from 38,024 to 28,082). This led to a composition of 17.1% professionals from the EEA and 82.9% from other countries of origin among those professionals on the register whose initial registration was outside the United Kingdom. The count of professionals departing the professions decreased marginally last year, totalling just below 27,000. Nevertheless, apprehensions regarding the future retention of staff persist, as 52 percent of professionals who left the register stated they departed earlier than initially intended.

- 179/180 -

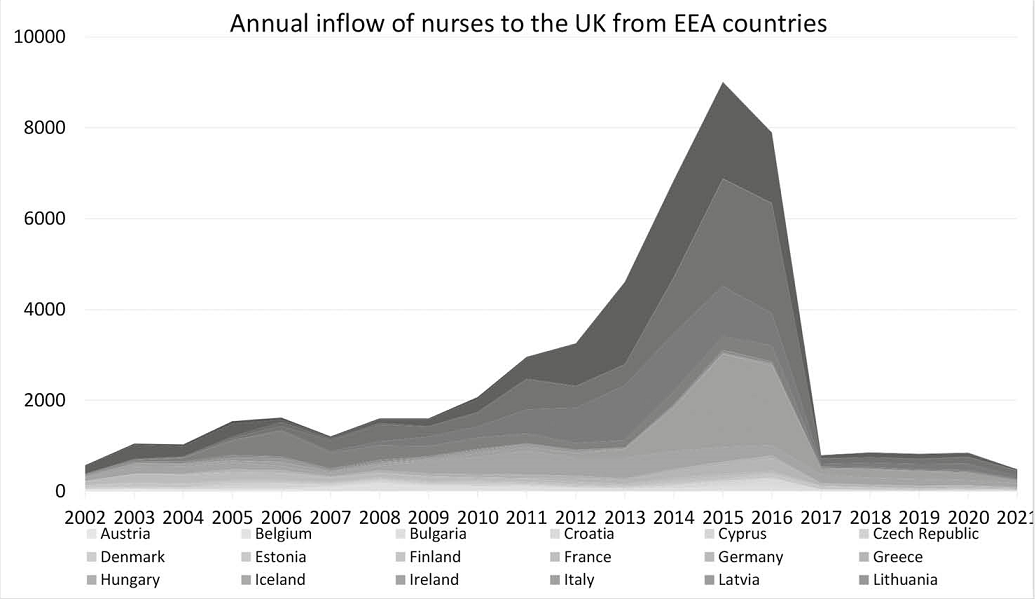

To support the most recent NMC analysis -which is not as detailed as the GMC1s one - with numbers broken down by EEA country, we have to check the OECD database[55] for migration data about nurses. The annual inflow of foreign-trained nurses in the UK has witnessed a striking decline - see Figure 1 - across nearly all EEA countries, coupled with a consistent decrease in the overall stock notably from all regions, including Spain, Romania, Italy, Portugal and Ireland, being the top five in the stock, as also emphasised by a previous report.[56] This latter also contained a survey on the reasons for leaving. Of the 21,800 professionals who left the register between July 2019 and June 2020, 14,996 were asked to complete the questionnaire, with 5,639 respondents (37.6%). Each respondent could select three reasons for leaving. The results show that the 342 respondents who were educated in the EU were on average the youngest of the leavers (78.4% aged 21-40), with a significant number (79.2%) indicating that they were leaving or had left the UK, while the second most important reason given was Brexit itself (52.7%), followed by a change in personal circumstances (21.9%). The latest report used a new approach concerning the questionnaire; however, of the respondents from the EU, 57% listed leaving the UK as a reason without explicitly mentioning Brexit, along with 30% stating a change in personal circumstances.[57]

Figure 1. Annual inflow of EEA nurses to the UK

Source: Joint Questionnaire of Eurostat, OECD and WHO, OECD database

- 180/181 -

The above-introduced increase in nursing workforce numbers, and especially in overseas nurses is the result of a conscious political programme. The Conservatives, who won the December 2019 election and are now in government, recognising the problem, committed in their 2019 election pledges to recruit 12,000 nurses for the NHS by 2024/2025[58] as part of a wider commitment to increase the numbers of registered nurses in the NHS in England by 50,000 by the end of the Parliamentary term. The government issued a policy paper in March 2022, which sets out the programme in more detail, including the progress so far, the plans for meeting the target, the uncertainties, risks and mitigations and the next steps.[59] According to the analysis of the report and official statistics, as of March 2022, over 27,000 more nurses are working across the NHS since the programme began, including over 12,000 more nurses in training and over 15,000 more registered nurses. The sources of the increase in the number of registered nurses include a 40% increase in international nurses recruited to the NHS since 2019. The report is positive, saying the programme is on track to meet its target, but there are a number of challenges that need to be addressed. One challenge is the recruitment and retention of nurses. The government is taking a number of steps to address this, including increasing the number of nurse training places, offering bursaries to student nurses and improving the working conditions for nurses. Another challenge is the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the NHS. The pandemic has put a significant strain on the NHS workforce, and it has also led to delays in nurse training and recruitment. Despite these challenges, the government is committed to delivering the 50,000 Nurses Programme and believes in its success.

British sources[60] state that it was the failure of human resources planning in health that has resulted in the NHS now incorporating a programme of overseas recruitment into its long-term plans for 2019. Recruitment from third countries gained momentum in the wake of the COVID-19 epidemic, which began in 2020, with more than 8,000 (including more than 300 critical care nurses) recruited to the NHS in the 10 months following the first wave (April 2020 to January 2021). Hospitals in England were given £28 million in October 2020 to help provide flights, airport transfers and accommodation for nurses arriving as part of the international recruitment drive to get them to the UK as soon as possible.

- 181/182 -

So, for the time being, the UK has turned to overseas recruitment as one the main inputs to keeping the UK care system viable post-Brexit, which is ethically questionable, especially in the context of the WHO Global Code of Practice on the International Recruitment of Health Personnel,[61] adopted by WHO member states in 2010, which prohibits recruitment from countries with serious shortages. This voluntary Code has been taken over by the UK in a Code of practice for the international recruitment of health and social care personnel in England,[62] clearly specifying that active recruitment from countries categorised as 'red list' is discouraged, although individual applications from health and social care personnel are not restricted. According to a recent analysis,[63] since the 2019/20 period, there has been a tenfold surge in the count of new NMC registrants from countries on the red list. In the year 2022/23, more than one in ten (12%) of the new NMC registrants - just over 6,000 individuals - received their training in red list countries, with Nigeria accounting for over half of this group. Notably, Ghana has also experienced a substantial rise in the number of new NMC registrants over the past five years, increasing from 19 in 2017/18 to 1,263 in 2022/23.

2. The example of Hungary - what can we know from the available data?

a) Composition of Hungarian-trained doctors moving to the UK

In his PhD thesis on the monitoring of health professional mobility from Hungary, Cserháti[64] analysed data between 2010 and 2018 on official certificates requested for foreign employment and also compared them with the data on new entrants in the receiving countries register to determine the composition of those migrating. According to his work, the United Kingdom was the second most popular destination for doctors migrating out of Hungary between 2010 and 2018, following Germany. The peak of

- 182/183 -

this mobility was in 2011 based on Hungarian data, and in 2012 based on UK registration data. Afterward, the trend showed a decreasing and then stabilising pattern.

The analysis showed that the majority of applicants for these certificates were Hungarian citizens, while the number of British citizens who graduated in Hungary and applied for these certificates was quite low. In the case of the United Kingdom, the mobility of British medical students to Hungary was not significant, except in 2017 and 2018. Noteworthy is the trend in the number of Hungarian citizen doctors who requested these certificates for the first time. Between 2012 and 2016, this trend correlated most closely with the number of Hungarian-trained doctors registered in the destination country. Based on this, it can be assumed that the influx into the United Kingdom primarily consists of Hungarian doctors with Hungarian citizenship migrating for work purposes. Cserháti also adds that, among the certificate applicants, an average of about 30 doctors who had graduated in Hungary and were citizens of other countries applied each year. This indicates that the United Kingdom is a popular destination, not only for Hungarians but also for doctors from other countries who studied in Hungary. Among the certificate applicants, there are generally more than 20 Hungarian citizens each year who were not born in Hungary, including Hungarians from beyond the borders of Hungary who migrate further.

To conclude, in order to examine the post-Brexit mobility situation, it is a good estimate to rely on the aggregate numbers of certificates, as the major directions of mobility are determined by the largest groups being Hungarian citizens going to the UK for employment.

b) Analysis of sending country data

After having examined the data available in UK reports and international databases, it is also useful to have a look at the data of the Hungarian authority, the National Directorate for Hospitals (OKFŐ) in order to draw conclusions within the limitations of data expressing only the intention to leave. First, it is worth checking whether there has been any change in the number of qualifications obtained in the UK and recognised in Hungary following the Brexit referendum, as it is possible that Hungarians living/working abroad may have their new qualifications recognised if they move home. According to OKFŐ data, there has been a slight shift in the recognition of qualifications obtained in the UK compared to the 0-1 cases in previous years, particularly for allied health professionals, where there have been more cases than in previous years since 2016, with 11 such decisions in 2017, the year following the referendum, and 11 in 2020, the year of exit, and yearly 5-8 in other years, among which almost all are Hungarian citizens (Table 1). These numbers are rather low, but the increase after 2016 concerning allied health professionals might have been caused by the situation following the referendum.

- 183/184 -

Table 1. Number of recognition decisions for UK qualifications 2011-2022, including HU citizens

| Doctors all | Doctors HU citizen | Dentists all | Dentists HU citizen | Pharmacists all | Pharmacists HU citizen | Allied HPs all | Allied HPs HU citizen | |

| 2011 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 2012 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 2013 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2014 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2015 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 2016 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 2 |

| 2017 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 11 |

| 2018 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 8 |

| 2019 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 4 |

| 2020 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 11 |

| 2021 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 5 |

| 2022 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 5 |

Source: OKFŐ data, 30 October 2023.

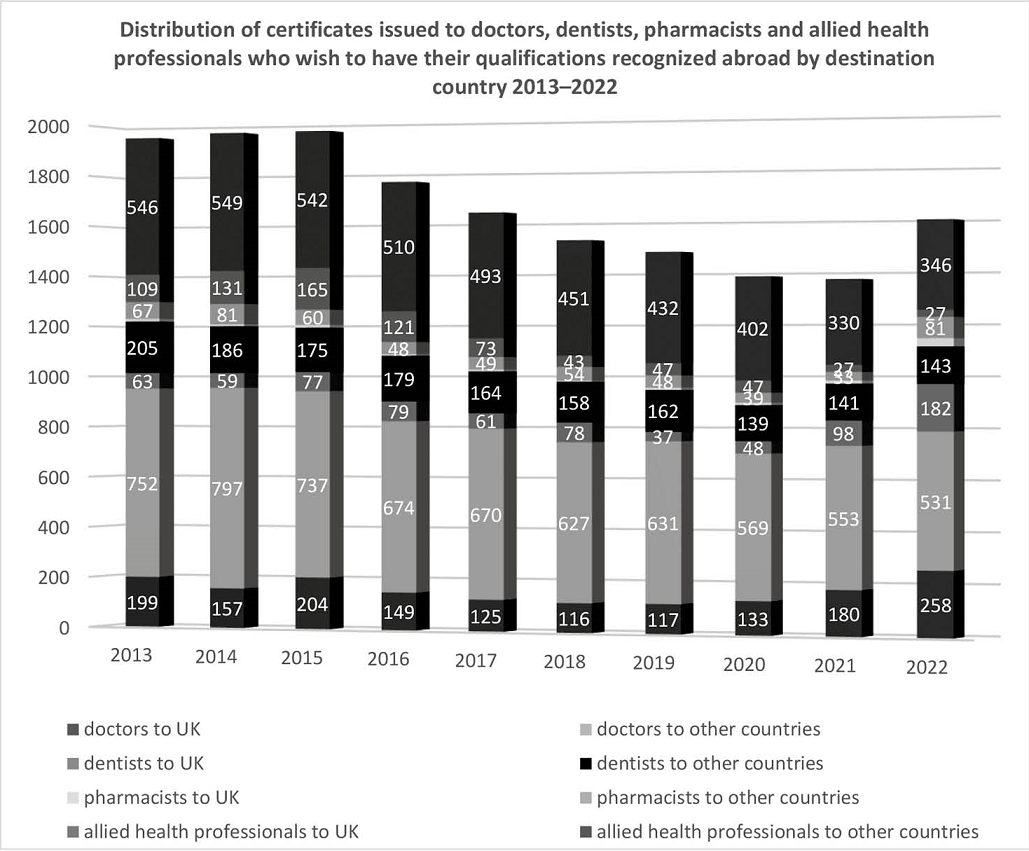

To examine the impact of Brexit on working abroad, it is even more important to look at the number of people applying for any of the certificates which the home country authorities might require. OKFŐ has only estimates of the country of destination, as it asks applicants on a voluntary basis in the procedure for issuing the official certificate, but a comparison of the respondents over several years shows the trends in choosing UK as a destination country. OKFŐ has been asked for data for the purpose of this study on doctors, dentists, pharmacists and allied health professionals (including mainly nurses).

For doctors, the Brexit referendum does not seem to have caused major disruption, with a steady decline in both total and UK employment intentions until 2019, and an increase since then, meaning that the popularity of the UK among destinations is increasing since the turning point in 2018, while the number of the remaining certificates (required to other countries or without stating the destination) is still decreasing (two bottom parts of the column in Figure 3). As the number of doctors with an intention to move to the UK decreased only until 2018, together with the overall number (so not because of Brexit but perhaps due to measures taken by Hungary to retain the workforce), and has been increasing since then, I tend to agree with the conclusions of the GMC in the previous chapter that Brexit had no influence on CEE doctors' intention to work there, but, on the contrary, their number and

- 184/185 -

proportion of the total has been increasing since then. As far as dentists are concerned, we see stable numbers with small fluctuations, followed by a drop in 2019 and a significant upswing in numbers since then, showing a similar trend to that seen for doctors. The flow of pharmacists to the UK was quite negligible, fluctuating between 4 and 12 from 2013 to 2021; however, there was a jump to 32 in 2022 following the pattern of the overall number, so it most probably has nothing to the with Brexit or UK policies. As expected however, the picture is completely different for allied health professionals, the majority of whom are nurses. For them, too, we observe a decrease in both total and emigration intentions to the UK (from 655 to 373 in total and from 109 to 27 to UK respectively between 2013 and 2022), while since 2016, following the Brexit referendum, we see a considerable decrease in the popularity of the UK as a destination (between 2013 and 2022, the proportions within the total were 16.64% 19.26% 23.34% 19.18% 12.90% 8.70% 9.81% 10.47%, 7,56% and 7,24%, the two upper parts of the columns in Figure 2).

Figure 2. Intention to work in the UK for each health profession, compared to other destinations 2013-2022

Source: OKFŐ data, 30 October 2023.

- 185/186 -

VI. Conclusions

In the initial phase of the Brexit negotiations, specifically during the adoption of the Withdrawal Agreement, a mutual decision was reached by the parties to uphold the existing regime throughout the transition period. It would have been in the best interest of the United Kingdom to extend this system for the recognition of professional qualifications post-Brexit. This continuity could have been crucial for facilitating the seamless attraction of the essential workforce, particularly in occupations facing shortages, of which the majority falls within the healthcare professions. Maintaining the simplest possible procedures via a reciprocal EU arrangement would not only have benefited the United Kingdom but also enabled British nationals to gain recognition on favourable terms within other EU Member States. Despite the British government's efforts, the previous regime on the mutual recognition of professional qualifications has however been discontinued and is only maintained unilaterally by the UK.

In the absence of a specific agreement on recognition, legal relations between the two jurisdictions on the mutual recognition of diplomas have been severed since the UK left the EU. A first initiative concerning architects is now on the table of the Partnership Council, but progress is slow. Previously, experts assessed it as highly uncertain whether the possibility of agreements based on the initiative of individual professional organisations, as introduced by the Trade and Cooperation Agreement governing future relations, would lead to results, as the Free Trade Agreement with Canada has not yet produced anything substantive. However, the fact that Canada-EU relations have never been characterised by a level of integration comparable to that of the UK-EU cannot be overlooked in this assessment, and this may influence the development of possible profession-specific agreements, especially where the training content is very similar. As architects were among the professionals who previously benefited from automatic recognition, it will be interesting to see how quickly an agreement can be reached, especially compared to the CETA, where the same profession has been the primary proposal.

As regards bilateral agreements, no EU country has yet concluded one, however Switzerland, having had the same EU rules in force previously, has just concluded an agreement with the UK, stating that, in order to reach the strategic objective of the international recognition of Swiss professional qualifications, additional mutual recognition agreements are needed to cover qualifications awarded in countries with a comparable education system is to Switzerland's. As both UK and Switzerland have an outstanding education system, the United Kingdom is an ideal partner for Switzerland to support this objective.[65] This agreement does not yet have special rules on healthcare

- 186/187 -

qualifications, but can later be modified by adding Annexes or special recognition agreements. It will be interesting to observe whether any EU Member States will follow the Swiss example. The question is of course how the political will of the UK government and especially individual Member States will evolve, given the growing shortage of health professionals in all Member States.

In terms of the evolution of Hungarian work preferences following Brexit, the number of official certificates requested in Hungary, which are usually required for employment abroad, decreased for doctors in the UK as a destination country between 2013 and 2019 at a similar rate as the number of people requesting a certificate overall, so not because of Brexit, and has been increasing since then, meaning that UK as a destination country has not lost its popularity for Hungarian-trained doctors, but the opposite. UK data on doctors also show that Brexit disruption is not visible in the employment of EEA-trained doctors. The absolute number has been increasing slightly since 2016, and the regional breakdown of the data clearly shows that the largest and continuous increase in arrivals is from the new Member States.

The situation of Hungarian and EEA nurses however are completely different. The data from Hungary indicates a notable decline in the attractiveness of the UK as a destination for nurses after 2016. Simultaneously, the data from the British Chamber reveals a substantial departure of EEA nurses in recent years, coupled with a considerably reduced annual intake of new entrants from the EEA since that period. There have been many studies and articles analysing the possible causes for such a huge decline.

As the article examining the situation and migrant NHS nurses' sense of being only tolerated citizens in post-Brexit Britain[66] collects, apart from blaming Brexit,[67] the outward mobility of EU NHS nurses and the lower interest of new EU nurses in joining the NHS have been attributed also to other factors, such as: uncertainty connected to the position of EU citizens post-Brexit, as the report of the Nursing and Midwifery Council of 2018 suggested,[68] the increased incidents of xenophobia and racism[69] and the introduction of English language requirements for EU nurses by the

- 187/188 -

NMC in 2017, already in place for non-EU nurses.[70] In order to compensate for the loss and lack of inflow of EEA nurses, and to meet the constantly increasing demand for NHS nurses, as part of a government programme, a significant increase in the number of overseas nurses could be observed in the last couple of years. The increased international recruitment however - also with regard to doctors where the number of IMG doctors has also considerably increased - raises questions about the implementation of the WHO Global Code of Practice on the International Recruitment of Health Personnel, especially towards countries on the "red list", from where international recruitment should not happen according to its provisions.

The King's Fund, an independent think tank involved in work relating to the health system in England suggests in its analyses of 2019[71] that the NHS and the social care system will not be able to survive without an international workforce. In the short term, the NHS shortage in nursing is such that 5,000 more nurses would be needed each year until domestic training capacity is strengthened. A long-term and more complex solution would be needed to keep up with the NHS's increasing needs, including measures increasing the number of training places, reducing the drop-out rate during training, and encouraging more people to join the NHS once they qualify. Additional measures such as improving pay and working conditions in order to make the NHS a more competitive employer and helping to retain staff, investing in health workforce planning, creating a more supportive workplace culture to reduce stress and burnout and also the need to address the wider social determinants of health, such as poverty and inequality to reduce the demand for healthcare services in the long term, are among their not surprising proposals. The King's Fund concludes that the UK government must take urgent action to address the workforce crisis in the health and care system, which requires a long-term commitment to investment and reform. It will be interesting to follow what decisions Britain will take in the future to establish and maintain a sustainable heath workforce. ■

NOTES

[1] É. Gellérné-Lukács, Á. Töttös and S. Illés, Free movement of people and the Brexit, (2016) 65 (4) Hungarian Geographical Bulletin, (421-432) 422; É. Gellérné Lukács, Brexit - a Point of Departure for the Future in the Field of the Free Movement of Persons, (2018) (1) ELTE Law Journal, 141-162. DOI: https://doi.org/10.15201/hungeobull.65.4.9

[2] Kovács R., A Brexit hatása a diplomák kölcsönös elismerésére, illetve az egészségügyi szakemberek külföldi munkavállalására, in Fazekas M. (szerk.), Jogi tanulmányok 2021, (ELTE ÁJK Doktori Iskola, Budapest, 2021) 448-466; Bóka J., Halmai P. and Koller B., Válás "Angolosan" - A BREXIT politikai, jogi és gazdasági agendái. (2016) (2) Magyar Közigazgatás, 58-79.

[3] Commission Staff Working Document on an Action Plan for the EU Health Workforce, 2012., https://health.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2016-11/staff_working_doc_healthcare_workforce_en_0.pdf (Last accessed: 29.12.2023.).

[4] K. Garratt, NHS strike action in England, Research Briefing, 17.10.2023., https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/cbp-9775/ (Last accessed: 29.12.2023.).

[5] Directive 2005/36/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 7 September 2005 on the recognition of professional qualifications (consolidated version of 09/10/2023), https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:02005L0036-20231009 (Last accessed: 29.12.2023.); Directive 2011/24/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 9 March 2011 on the application of patients' rights in cross-border healthcare was also adopted to give effect to mobility of patients; É. Gellérné Lukács, Prior and Subsequent Authorization of Cross-Border Healthcare under Directive 2011/24/EU, (2023) 11 (1) Hungarian Yearbook of International and European Law, 50-73. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5553/HYIEL/266627012023011001005

[6] Ibid, Article 4.1.

[7] Ibid, Article 12(1b).

[8] Ibid, Article 14.

[9] Ibid, Article 4a (7).

[11] Agreement on the withdrawal of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland from the European Union and the European Atomic Energy Community, Official Journal of the European Union, CI 384/1. 12.11.2019., https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:12019W/TXT(02) (Last accessed: 29.12.2023.).

[12] Issuing of a European Professional Card for the purpose of establishment and the temporary and occasional provision of services covered by Article 7(4).

[13] Trade and Cooperation Agreement between the European Union and the European Atomic Energy Community, of the one part, and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, of the other part, Official Journal of the European Union, L149/10, 30.04.2021., https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:22021A0430(01) (Last accessed: 29.12.2023.).

[14] EU-UK Trade and Cooperation Agreement - Press Release, 24 December 2020, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/hu/IP_20_2531 (Last accessed: 29.12.2023.).

[15] I. Jozepa, UK-EU Trade and Cooperation Agreement: professional qualifications, House of Commons Library Briefing Paper, No. 9172, 27 May 2021. 5., https://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/CBP-9172/CBP-9172.pdf (Last accessed: 29.12.2023.); Deloitte, Mutual recognition of professional qualifications, Brexit deal analysis, https://www2.deloitte.com/uk/en/pages/about-deloitte-uk/articles/fta-mutual-recognition-of-professional-qualifications.html (Last accessed: 29.12.2023.).

[16] There are, however, divergent interpretations, e.g. Catherine Barnard, Professor at the University of Cambridge, has pointed out that the text of Article 158 does not make it clear that a bilateral agreement that bypasses the EU as a contracting party to the TCA is possible: it is possible to argue both [Cambridge University Centre for European Legal Studies (CELS), Rapid Response Seminar on the EU-UK Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA) and the EU (Future Relations) Act; 1h 48 min, 14 Jan 2021].

[17] Jozepa, UK-EU Trade and Cooperation Agreement: professional qualifications, 4.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Ibid. 6.

[20] UK-EU Trade and Cooperation Agreement: Qualifications, Question for Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office UIN 172446, tabled on 23 March 2023., https://questions-statements.parliament.uk/written-questions/detail/2023-03-23/172446/ (Last accessed: 29.12.2023.).

[21] REPORT FROM THE COMMISSION TO THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND THE COUNCIL on the implementation and application of the Trade and Cooperation Agreement between the European Union and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland 1 January - 31 December 2022 Brussels, 15.3.2023 COM(2023)118 final, 7., https://commission.europa.eu/system/files/2023-03/COM_2023_118_en.PDF (Last accessed: 29.12.2023.).

[22] In addition, the Parties took note of the receipt of the Joint Recommendation for a Mutual Recognition Arrangement for Architects from the Architects Council of Europe and the Architects Registration Board. The Parties took note of the relevant procedures on professional qualifications in Article 158 of the TCA, also noting that the TCA requires the Partnership Council to review the consistency of a joint recommendation with the Services and Investment Title within a reasonable period of time. Joint Minutes of The second Trade Specialised Committee on Services, Investment and Digital Trade under the EU-UK Trade and Cooperation Agreement Brussels, 20 October 2022., https://commission.europa.eu/system/files/2023-02/Minutes%20-%20Second%20meeting%20of%20TSC%20on%20Services%2C%20Investment%20and%20Digital%20Trade.pdf (Last accessed: 29.12.2023.).

[23] Report of the Committee on the Mutual Recognition of Professional Qualifications to the Joint Committee, March 10, 2022., https://www.international.gc.ca/trade-commerce/trade-agreements-accords-commerciaux/agr-acc/ceta-aecg/2022-03-10-joint-report-rapport-conjoint.aspx?lang=eng (Last accessed: 29.12.2023.).

[24] Draft DECISION OF THE JOINT COMMITTEE ON MUTUAL RECOGNITION OF PROFESSIONAL QUALIFICATIONS setting out an agreement on the mutual recognition of professional qualifications for architects. Brussels, 12 October 2023 (OR. en) 11527/22 ADD 1., https://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/ST-11527-2022-ADD-1/en/pdf (Last accessed: 29.12.2023.).

[25] Health and Care Worker visa, https://www.gov.uk/health-care-worker-visa (Last accessed: 29.12.2023.).

[26] Guidance. Immigration health surcharge: guidance for health and care reimbursements, Updated 1 October 2021, https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/immigration-health-surcharge-applying-for-a-refund/immigration-health-surcharge-guidance-for-reimbursement-2020 (Last accessed: 29.12.2023.).

[27] P. Barbato, Health and Care Visa Guide 2023. 4 October 2023., https://www.davidsonmorris.com/health-and-care-visa/ (Last accessed: 29.12.2023.).

[28] The European Qualifications (Health and Social Care Professions) (Amendment etc.) (EU Exit) Regulations 2019, https://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2019/593/contents/made (Last accessed: 29.12.2023.).

[29] Guidance. EEA-qualified and Swiss healthcare professionals practising in the UK, https://www.gov.uk/guidance/eea-qualified-and-swiss-healthcare-professionals-practising-in-the-uk (Last updated. 11.05.2022, last accessed: 29.12.2023.).

[30] The Recognition of Professional Qualifications and Regulation of Professions: Call for Evidence, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1005090/recognition-professional-qualifications-regulation-professions-cfe-summary-responses.pdf (Last accessed: 29.12.2023.).

[31] Jozepa, UK-EU Trade and Cooperation Agreement: professional qualifications, 8.

[32] E. Parr, Automatic recognition of EU doctors to continue for at least five years, 12 July 2023, https://www.pulsetoday.co.uk/news/workforce/automatic-recognition-of-eu-doctors-to-continue-for-at-least-five-years/ (Last accessed: 29.12.2023.).

[33] Department of Health and Social Care: Decision. Professional qualifications - EU Exit standstill provisions: review by the Secretary of State (Updated 7 September 2023), https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/professional-qualifications-eu-exit-standstill-provisions-review-by-the-secretary-of-state/professional-qualifications-eu-exit-standstill-provisions-review-by-the-secretary-of-state#fn:1 (Last accessed: 29.12.2023.).

[34] Agreement between the European Community and its Member States, of the one part, and the Swiss Confederation, of the other, on the free movement of persons, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A02002A0430%2801%29-20210101 (Last accessed: 29.12.2023.).

[35] Switzerland and United Kingdom sign agreement on mutual recognition of professional qualifications, Press releases, 14.06.2023., https://www.eda.admin.ch/countries/united-kingdom/en/home/news/news.html/content/europa/en/meta/news/2023/6/14/95673 (Last accessed: 29.12.2023.).

[36] At their meeting in London on 14 June 2023, Federal Councillor Guy Parmelin and British Secretary of State for Business and Trade Kemi Badenoch signed the agreement on the mutual recognition of professional qualifications, as the second agreement signed with a partner outside the EU, after Quebec.

[37] I. Sándor and É. Gellérné Lukács, Dual nature of international circular migration, (2022) 19 (2) Migration Letters, 149-158. DOI: https://doi.org/10.33182/ml.v19i2.1554

[38] Z. Aszalós, R. Kovács, E. Eke, E. Kovács, Z. Cserháti, E. Girasek and M. Van Hoegaerden, Health workforce mobility data serving policy objectives: D042 Report on Mobility data - Joint Action on European Health Workforce Planning and Forecasting 2016., 36 and 67., https://ja-archive.healthworkforce.eu/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/160127_WP4_D042-Report-on-Mobility-Data-Final.pdf (Last accessed: 29.12.2023.).

[39] Directive 2005/36/EC, Article 50(1), Annex VII.

[40] Országos Kórházi Főigazgatóság (OKFŐ), Humánerőforrás-fejlesztési Igazgatóság, Hatósági bizonyítványokkal kapcsolatos általános tájékoztató, https://www.enkk.hu/index.php/hun/elismeresi-es-monitoring-foosztaly/hatosagi-bizonyitvanyok/hatosagi-bizonyitvanyokkal-kapcsolatos-altalanos-tajekozato (Last accessed: 29.12.2023.).

[41] Directive 2005/36/EC, Article 23.1.

[42] Ibid, Articles 23.6, 24, 25, 28, 31, 34, 35, 40 and 44.

[43] European Commission, Regulated Professions Database, https://ec.europa.eu/growth/tools-databases/regprof/ (Last accessed: 29.12.2023.).

[44] Aszalós, Kovács, Eke et al., Health workforce mobility data serving policy objectives: D042 Report on Mobility data... 36.

[45] Healthcare non-expenditure statistics manual and guidelines for completing the Joint questionnaire on non-monetary healthcare statistics, 2023 edition, (Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, 2023) 38-39, https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/3859598/17120833/KS-GQ-23-001-EN-N.pdf/f7584d59-88c5-b263-f6e2-4670ed8e89a3?version=1.0&t=1688982804201 (Last accessed: 29.12.2023.).

[46] Ibid, 13.

[47] W. Chick and M. Exworthy, Post-Brexit views of European Union doctors on their future in the NHS: a qualitative study, (University of Birmingham, 2017), https://bmjleader.bmj.com/content/2/1/20 (Last accessed: 29.12.2023.). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1136/leader-2017-000049

[48] General Medical Council, Our data about doctors with a European primary medical qualification in 2021, Working paper, 12, November 2021., https://www.gmc-uk.org/-/media/documents/eea-pmq-report-2021-final_pdf-88482214.pdf (Last accessed: 29.12.2023.).

[49] Ibid. Figure 9.

[50] Ibid. Figure 8.

[51] Ibid. Table 2.

[52] The state of medical education and practice in the UK. The workforce report 2022, (General Medical Council, October 2022.), http://www.gmc-uk.org/workforce2022 (Last accessed: 29.12.2023.).

[53] Nursing and Midwifery Council, The NMC register 1 April 2022 - 31 March 2023, [NMC 2023], https://www.nmc.org.uk/globalassets/sitedocuments/data-reports/may-2023/0110a-annual-data-report-full-uk-web.pdf (Last accessed: 29.12.2023.).

[54] Comparing data from Nursing and Midwifery Council, The NMC register 1 April 2020 - 31 March 2021, https://www.nmc.org.uk/globalassets/sitedocuments/data-reports/annual-2021/0005b-nmc-register-2021-web.pdf (Last accessed: 29.12.2023.) and Nursing and Midwifery Council, The NMC register 1 April 2022 - 31 March 2023.

[55] OECD Statistics, https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?QueryId=68336# (Last accessed: 29.12.2023.).

[56] Nursing and Midwifery Council, The NMC register 1 April 2020 - 31 March 2021, 13.

[57] Nursing and Midwifery Council, The NMC register 1 April 2022 - 31 March 2023, 22.

[58] J. Holmes, What have the parties pledged on health and care? 28 November 2019, https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/parties-pledges-health-care-2019#international-recruitment (Last accessed: 29.12.2023.).

[59] 50,000 Nurses Programme: delivery update. Policy paper. 7 March 2022., https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/50000-nurses-programme-delivery-update/50000-nurses-programme-delivery-update (Last accessed: 29.12.2023.).

[60] S. Lintern, NHS recruits thousands of overseas nurses to work on understaffed wards. independent, 10.03.2021., https://www.independent.co.uk/news/health/coronavirus-nurses-nhs-overseas-recruitment-b1815367.html (Last accessed: 29.12.2023.).

[61] WHO Global Code of Practice on the International Recruitment of Health Personnel, https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/3090/A63_R16-en.pdf?sequence=1 (Last accessed: 29.12.2023.).

[62] Department of Health and Social Care, Guidance, Code of practice for the international recruitment of health and social care personnel, 25 February 2021. Last updated: 23 August 2023, https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/code-of-practice-for-the-international-recruitment-of-health-and-social-care-personnel/code-of-practice-for-the-international-recruitment-of-health-and-social-care-personnel-in-england#guiding-principles (Last accessed: 29.12.2023.).

[63] J. Buchan, N. Shembavnekar and N. Bazeer, How reliant is the NHS in England on international nurse recruitment? The Health Foundation, 12 June 2023., https://www.health.org.uk/news-and-comment/charts-and-infographics/how-reliant-is-the-nhs-in-england-on-international-nurse-recruitment (Last accessed: 29.12.2023.).

[64] Cserháti Z., Egészségügyi szakemberek Magyarországról külföldre irányuló mobilitásának monitorozása, Doktori értekezés, (Semmelweis Egyetem Mentális Egészségtudományok Doktori Iskola, Budapest, 2023), https://phd.semmelweis.hu/vedesek/2670/dolgozatDokumentumLetoltese (Last accessed: 29.12.2023.).

[65] Switzerland and United Kingdom sign agreement on mutual recognition of professional qualifications, Press releases, 14.06.2023., https://www.eda.admin.ch/countries/united-kingdom/en/home/news/news.html/content/europa/en/meta/news/2023/6/14/95673 (Last accessed: 29.12.2023.).

[66] G. Spiliopoulos and S. Timmons, Migrant NHS nurses as 'tolerated' citizens in post-Brexit Britain, (2023) 71 (1) The Sociological Review, 183-200. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/00380261221092199 (Last accessed: 29.12.2023.).

[67] D. Campbell, Brexit blamed as record number of EU nurses give up on Britain, The Guardian, 25.04.2018., www.theguardian.com/society/2018/apr/25/brexit-blamed-record-number-eu-nurses-give-up-britain (Last accessed: 29.12.2023.).

[68] New figures highlight 'major concern' as more EU nurses leave the UK, The NEN - North Edinburgh News, 28.04.2018., https://nen.press/2018/04/28/new-figures-highlight-major-concern-as-more-eu-nurses-leave-the-uk/ (Last accessed: 29.12.2023.).

[69] S. Johnson, EU workers in the NHS: 'I've faced racial abuse and will head home', The Guardian, 06.07.2016., www.theguardian.com/healthcare-network/2016/jul/06/eu-workers-nhs-faced-racial-abuse-head-home (Last accessed: 29.12.2023.); B. Quinn, Hate crimes double in five years in England and Wales, The Guardian, 15.10.2019., www.theguardian.com/society/2019/oct/15/hate-crimes-double-england-wales (Last accessed: 29.12.2023.).

[70] S. Lintern, Exclusive: 'Crash' in EU nurses working in UK since 'Brexit' referendum. HSJ, 12.06.2017., www.hsj.co.uk/topics/workforce/exclusive-crash-in-eu-nurses-working-in-uk-since-' Brexit'-referendum/7018591.article?blocktitle=News&contentID=15303 (Last accessed: 29.12.2023.); News and updates: Read our latest registration data report, Nursing and Midwifery Council, 08.05.2019., www.nmc.org.uk/news/news-and-updates/nmc-register-data-march-2019/ (Last accessed: 29.12.2023.).

[71] J. Beech, S. Bottery, H. McKenna, R. Murray, A. Charlesworth, H. Evans, B. Gershlick, N. Hemmings, C. Imison, P. Kahtan and B. Palme, Closing the gap: key areas for action on the health and care workforce, The King's Fund, 21.03.2019., https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/closing-gap-health-care-workforce (Last accessed: 29.12.2023.).

Lábjegyzetek:

[1] The Author is PhD student, ELTE University, Faculty of Law, Department of International Private Law and Commercial Law; senior policy expert at Semmelweis University, Health Services Management Training Centre.