Attila Badó[1] - Mátyás Bencze[2]: Quality of justice in Hungary in European context (FORVM, 2016/2., 5-23. o.)

The main objective of maintaining the judicial system lies in the final adjudication of disputes and bringing violators of the law to justice. A democratic state governed by the rule of law is expected to have courts carrying out this activity both at a highly professional level and with efficiency.[1] The former requirement does not only incorporate competent and impartial judicial activity, but also a well thought-out application of the law that takes the principles lying behind it seriously. Apart from court proceedings handled within reasonable time, the latter includes judicial activity that results in a final ruling on the merits and preferably is associated with few negative externalities.

In both domestic and international specialist literature, organizational, managerial and constitutional law aspects come to the fore,[2] this approach being reflected in comparative analyses carried out by various international organizations as well.[3] Although these efforts also focus on important parameters, it is desirable on the author's part to leave the simple listing of organizational and docket data behind. In this chapter, the direction marked by John Griffith in his book entitled The Politics of the Judiciary is going to be followed.[4]

- 5/6 -

In it, he established a connection between empirical data relating to the judicial system, the trends in judicial practice and the accomplishment of the judiciary's social function.

Since there is no room for a comprehensive description of the Hungarian judicial system and the mapping of each problem,[5] the presentation of general data will be carried out by grouping them around two questions and in respect thereof. It is considered that efficiency and quality judgments as emphasized in the official strategy of the National Office for the Judiciary (hereinafter referred to as NOJ) encompass the two hubs that best reflect the current state of the Hungarian judicial system.[6]

The guarantee of the standards and efficiency of the administration of justice may, on the one hand, be found in structural conditions, and, on the other, the characteristics of the staff. The legal background (legislation on court procedure, the constitutional situation of courts, structural regulation of courts, the scope and distribution of managerial and supervisory powers) and working conditions (e.g. the solidified institutional practice, workload, personal and physical infrastructure, budget developments) may be regarded as structural conditions. The personal conditions are characterized by classic judicial virtues: professional competence, experience, wisdom, impartiality and fairness. In order to get a realistic image of the functioning of the judicial system, both sides have to be taken into consideration when carrying out the examination.

Within the entire judicial system, first and foremost, the operation of local courts (district courts) are analyzed since only a modicum of academic attention is paid to these courts while more than 90% of all court proceedings[7] are initiated in them; thus, citizens most frequently come into contact with this level (and, on the other hand, appeal rate remains relatively low, around 20%).[8]

With respect to the above described main function of courts, out-of-court procedures fall outside the field of vision of this study: they often lack a legal dispute on the merits (such as company proceedings, records of social organizations etc.); thus, they are barely taken into consideration as explanatory factors - should they exert any influence on the standards or efficiency of adjudicating lawsuits.

Although the structural changes taking place in 2012 significantly affected the current situation, there is no intention to analyze them here.[9] However, in certain instances where they possess explanatory power, they will be referred to, and, where appropriate, the year 2010 or 2011 will be used as a base period for illustrative purposes of the changes.

- 6/7 -

The efficiency of administering justice

A dominant factor in the efficiency of justice administration is the number of the judiciary staff which has developed in the past three years as shown in Chart No. 1. For the purposes of interpretation, it is advised to be aware of the fact that in the starting year of 2011, the number of judges was higher because in 2008 the National Judicial Council with its resolution No. 197/2008 (IX. 25.) granted a temporary approval of extra statuses at the Metropolitan Court and the Budapest Environs Regional Court until 31 December 2011. The growth in the number of the judiciary since 2012 does not reveal much about the efficiency of the structure in itself; however, it can be stated that this number is high allowing comparison at EU level. Hungary ranks seventh place regarding the number of judges per 100,000 inhabitants.[10] Currently, there are no comparative data in relation to the number of the judicial staff that aids and partially relieves the workload of judges. Table No. 2 reveals that the number of court clerks has significantly been on the rise since 2011. As for court aids, there is stagnation, while the number of other administrative employees has dramatically increased.

Table No. 1

The number of judges in Hungary (the author's compilation based on NOJ annual reports)

| Approved status | Actual | |

| 2011 | 2,914 | 2,871 |

| 2012 | 2,875 | 2,767 |

| 2013 | 2,910 | 2,807 |

| 30/06/2014 | 2,910 | 2,815 |

Table No. 2

The number of administrative employees in Hungary

(the author's compilation based on NOJ annual reports)

| Number of court clerks | Approved | Actual |

| 2011 | 614 | 605 |

| 2012 | 767 | 732 |

| 2013 | 767 | 777 |

| 30/06/2014 | 776 | 764 |

| Number of court aids | Approved | Actual |

| 2011 | 359 | 256 |

| 2012 | 359 | 239 |

| 2013 | 359 | 260 |

| 30/06/2014 | 348 | 252 |

| Number of other administrative employees | Approved | Actual |

| 2011 | 6,902 | 6,786 |

| 2012 | 7,016 | 6,920 |

| 2013 | 7,091 | 6,963 |

| 30/06/2014 | 7,073 | 7,019 |

- 7/8 -

These figures correlate to the time needed to resolve a case: while sixth in civil and commercial divisions, Hungarian courts rank fourth in the administrative division among EU Member States.[11] However, budgetary support for Hungarian courts is rather low compared to the general European level. Court expenditure per 100,000 inhabitants ranks Hungary merely at the 18[th] place.[12] All this is suggestive of efficient court operation; however, there are some factors that impede making reliable inferences.

In international comparison, there exists no methodology as to when a case may be regarded as resolved. Does only resolving a case on the merits (judgment) or also technical/case management resolution count (e.g. transfer to another court or interruption in civil proceedings)? How easy or difficult it is in a legal system for a judge to "get rid of" a case (which e.g. include the legal prerequisites of rejection of claim without summons) also makes a difference.

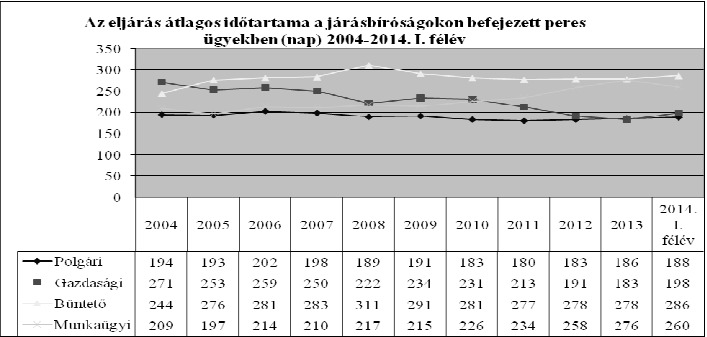

The result of a time series analysis seems to support the assumption based on which the period to resolve a case does not only depend on the number of judges and judicial employees, their working conditions and efforts. While the number of judges and judicial employees as well as the budgetary support of courts are constantly on the rise, the time needed to resolve a case at district court level in various divisions has shown significant variations over the years. As regards commercial cases, the clearance period followed the decrease in incoming cases, while the time needed to resolve cases in the civil division and in criminal proceedings reflects a slight, and in labor disputes a significant, increase (Chart No. 1).

- 8/9 -

Chart No.1.

Time needed to resolve cases at district court in four divisions

(the author's compilation based on NOJ annual reports)

One of the obvious explanatory reasons is the change in incoming cases, thus it is examined in Tables No. 3 and 4.

Table No. 3.

Changes in the number of litigious incoming cases at local courts (district courts)

(the author's compilation based on NOJ annual reports)

| LITIGIOUS | ||||||||

| Year | Civil proceedings | Commercial proceedings | Criminal proceedings | Misdemeanor proceedings | Administrative proceedings* | Labor proceedings | Total | |

| Total | publicly prosecuted | |||||||

| 2010 | 168,045 | 15,217 | 80,155 | 63,827 | 91,554 | - | 26,745 | 381,716 |

| 2011 | 161,335 | 13,881 | 77,980 | 61,510 | 107,276 | - | 22,844 | 383,316 |

| 2012 | 143,904 | 12,324 | 70,886 | 54,785 | 188,463 | - | 18,299 | 433,876 |

| 2013 | 148,181 | 12,924 | 77,978 | 60,455 | 369,783 | 17,597 | 16,023 | 642,486 |

| 2014 | 147,428 | 10,900 | 58,944 | 55,521 | 51,339 | 13,622 | 14,186 | 296,419 |

- 9/10 -

Table No. 4.

Changes in the number of non-litigious incoming cases at local courts (district courts) (the author's compilation based on NOJ annual reports)

| NON LITIGIOUS | |||||||

| Year | Civil and commercial non-litigious | Court execution cases | Criminal non-litigious cases in total | Misdemeanor non-litigious | Administrative non-litigious | Labor non-litigious | Total** |

| 2010 | 375,981 | - | 64,265 | 28,915 | - | 4,346 | 473,507 |

| 2011 | 64,328 | - | 62,186 | 26,547 | - | 1,860 | 154,921 |

| 2012 | 61,521 | - | 58,838 | 11,651 | 1,501 | 133,511 | |

| 2013 | 62,138 | 134,734 | 59,012 | 4,647 | 4,611 | 1,232 | 131,640 |

| 2014 | 62,019 | 118,522 | 78,074 | 311,655 | 4,386 | 1,322 | 575,978 |

At first glimpse, it seems that variation was equally great between 2010 and 2014 with regard to incoming litigious and non-litigious cases. If, however, merely the "classic" court proceedings are examined (civil, commercial, labor and administrative proceedings as well as publicly prosecuted criminal proceedings), a considerable 10% or so decrease may be found in incoming cases (whereas in civil and criminal divisions the decrease exceeded 10%, the number of incoming cases was at a third as regards commercial cases and it dropped almost by half in respect to labor law cases). Although the number of misdemeanor proceedings temporarily grew in a drastic fashion (in 2012 and 2013), by 2014 it had dropped to slightly more than half of the 2010 figure.

The number of non-litigious proceedings also requiring court resources and, to a certain extent, influencing the judges' workload, showed considerable variability in the examined period. The volatile drop from 2010 to 2011 was due to the fact that payment warrant procedures were assigned to the notarial function. However, this did not result in the decrease in the working load since it was one of the simplest procedures that could be handled practically in a mechanical fashion. From 2013 to 2014, just the opposite process took place, since misdemeanor case handling turned mainly into a simpler non-litigious procedure.

The most plausible correlation between the number of incoming cases and the period of resolving a case would be the fact that the decreasing case amount induces a shorter resolving period because the judge may hear the same case in shorter intervals. Therefore, with the exception of the commercial division working with the smallest case number, the question is why a slight or a significant increase follows the considerable decrease in the number of cases. The answer may be found in the interaction of factors that are unknown[13] (work organization issues, the changes of case structure etc.). Generally speaking, one may venture to state that changes in legislation resulting in the massive

- 10/11 -

incoming of cases[14] (e.g. in the misdemeanor division or in company cases relating to courts of law) do not improve predictable case management and, thus, resolving cases within reasonable time.

It may be projected as a prognosis that if the decrease of incoming cases continues or it stabilizes at the present level, the timeliness of court proceedings will also continue to be improved. However, it would not be unwise to separate the technical resolving of cases and resolving cases on the merits in statistical figures in the future. Although it is true that not resolving cases on the merits may also be final and the case is not brought back to court, a court settlement or the judgment usually constitutes a reassuring decision for the parties. The general public will not judge a court based on the velocity with which it resolves the proceedings by rejection of a claim without summons, transferring the case or otherwise trying a case not on the merits, but based on the amount of time needed to resolve the legal dispute. This modification would also be productive because if this kind of registry was introduced in other EU Member States as well, comparison would then better reflect reality.[15] The current system encourages Member State court management to improve on the surface indicators if it expects to achieve good results, which is far simpler than achieving the thorough hearing of cases, yet within a reasonable time limit.[16]

From this aspect, changes that have recently made the citizens' right to apply to the courts difficult or fall behind in terms of reconcilability with the due process requirement may be assessed as a negative tendency. Two examples of such changes may be emphasized in the field of civil procedural law.

The more serious effect may have been triggered by the price increase of court fees in 2011. The amount of court fees in procedures at first instance was maximized to HUF 1,500,000 and HUF 2,500,000 on appeal,[17] and the conditions of granting exemption from costs have not been altered (per capita income not exceeding the minimum old-age pension and the lack of assets ensuring livelihood and, apart from that, if litigation costs endangered the livelihood of the litigant).[18] It is a new regulation that 10% of the court fees will have to be paid even if the case was rejected without summons by the court.[19]

Moreover, in 2011, concerning certain litigious cases, the legislator considerably extended the scope of litigation where legal representation is mandatory (e.g. copyright

- 11/12 -

proceedings).[20] In these cases, both the plaintiff and the defendant are obliged to have legal representation, otherwise their procedural statements will become invalid.[21] This means a considerable burden on the litigants who may sometimes have only high hopes for the losing party to be solvent. [22]

Naturally, these conditions contribute to the decrease in incoming cases; however, they may discourage citizens to apply to the courts and encourage them to utilize other extralegal, even illegal means to enforce their claims.

As far as criminal procedure is concerned, the tendency is that the legislator achieves accelerated proceedings by curtailing procedural safeguards. These include the option of the defendant not to appear at the hearing,[23] the court may order witnesses to make a written testimony in lieu of oral examination[24] and, unless an unforeseeable and insurmountable obstacle arises, it has become the obligation of the counsel for the defence to provide for a substitute should he not be present at a procedural action.[25]

In addition to procedural means, a featured role is also attached to work organization within the court to reduce backlog of cases. Following the case transfer system that failed under review by the Constitutional Court [Constitutional Court Ruling No 36/2013 (XII. 5.)], a practice evolved according to which judges are assigned from other courts to a court with surpassing backlog; however, they do not try the cases at the place of their assignment, but at their original courts - on behalf of the court which they have been assigned to.[26] Although this method is undoubtedly an efficient means to distribute caseloads, it raises serious misgivings as well. On the one hand, in substance, it is smuggling back case transfer (since judges are assigned to try specific cases) and this way litigants and the accused are deprived of access to their legitimate court. On the other hand, the losing party or the convicted defendant will have to bear the extra costs that incurred due to the necessity to travel much further than the venue of the competent court (e.g. travelling expenses of witnesses).

Based on the above, it may be established that prioritizing the improvement of time management efficiency over the prevalence of the quality requirement by the courts and leaders disposing over the entire operations of the legal system constitutes a serious risk factor. Naturally, the desire to have quantifiable results to show off before external and internal forums is understandable; however, the personal impressions of citizens coming into

- 12/13 -

direct contact with courts also has to be balanced on the scales, which is a determining factor of the trust placed in the entire justice system.

The conditions of quality justice

Applied methods of assessing quality

The objective assessment of the quality of judicial activities is one of the most challenging tasks for the internal management of justice as well as the political leaders responsible for the condition of the judiciary system. On the one hand, one has to respect the courts' structural and the judges' personal independence and, on the other hand, it is rather difficult to evaluate a sequence of complex and deep thinking such as dispensing justice with exact methods.[27] Therefore, an indirect and mixed assessment method (based on a variety of indicators) is generally applied in the world's different legal systems.[28] What follows now is the analysis of the two applied methods within the Hungarian judicial system. One is the appeal ratio serving as a tool in the assessment of the operation of a specific court and the other is the personal assessment of the judges' work.

Appeal ratio

The NOJ refers to issues of quality with the expression of "the soundness of dispensing justice" in its assessment practice. The NOJ's surveillance over the appeal ratio has been traceable since 2012. Despite various practical problems that arise, this indicator may be regarded as a relatively reliable one because it does not utilize any internal standards of the judicial profession, but it is based on a court "user" assessment, therefore, it reflects upon the ultimate goal of the justice system. If the concerned parties in court proceedings are satisfied, one may not have any misgivings about the quality of dispensing justice.[29]

Comparative data of sufficient weight in number are only available regarding civil cases. An international comparison would be extremely problematic since contrasting remedial regulations of different legal systems may distort the picture. To be able to interpret the Hungarian data, one should be aware that the 2011 and 2012 figures reflect the rate of appeals against all final decisions, while the 2014 chart only contains the appeals against judgments. This difference explains why compared to 2012, the appeal ratio is almost twice as much in 2014 (unfortunately, no data are available from 2013). Apart from this, the 2014 chart contains an aggregate of the appeal ratio of all non-criminal (and non-misdemeanor) cases, whereas these data were only available from 2011 and 2012 broken down according to case division.

- 13/14 -

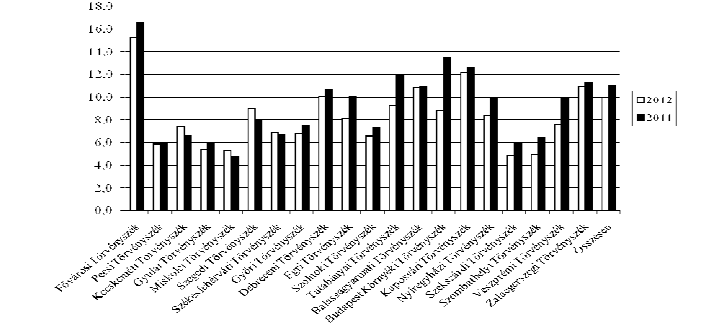

Chart No. 2.

Appeal ratio at district courts in civil division and at administrative and labor courts in the first six months of 2014 (informative analysis published by the NOJ)[30]

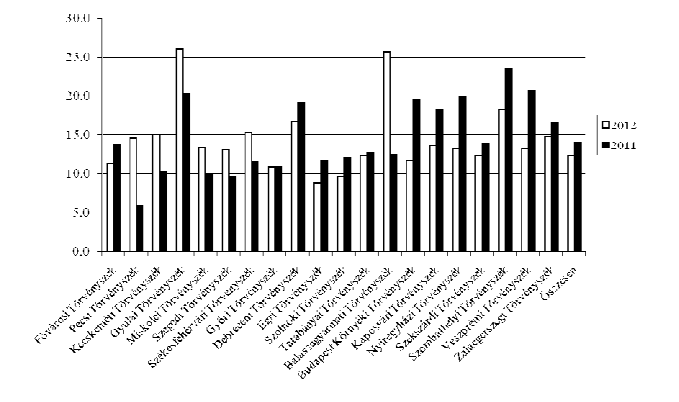

Chart No. 3.

Appeal ratio against final decisions at district court in civil division in 2011 and 2012 (Informative analysis published by the NOJ)[31]

- 14/15 -

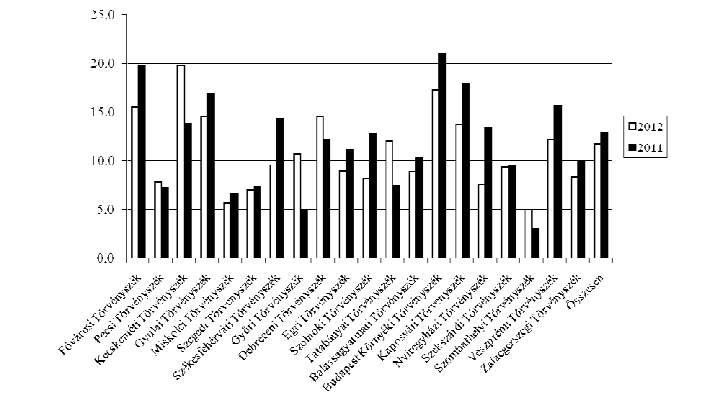

Chart No. 4.

Appeal ratio against final decisions at district court in commercial division in 2011 and 2012 (Informative analysis published by the NOJ)

Chart No. 5.

Appeal ratio against final decisions at district court in labor division in 2011 and 2012 (Informative analysis published by the NOJ)

- 15/16 -

By studying the 2014 figures, it is striking how considerable the variation is at each court of law. A well-founded inference for the causes might be concluded if data were available going back years; however, it is apparent from their comparison to the 2011 and 2012 data that there are courts of law where appeal ratios are steadily higher that in the case of others.

One tendency is that district courts operating in the jurisdictional venue of the Metropolitan Court (metropolitan district courts) have a significantly high appeal ratio. The phenomenon may have various causes. It is possible that at courts with greater caseloads there is less time available for trying cases thoroughly, thus, clients are more dissatisfied with the final decisions.[32] The high appeal data of the capital may be justified by the fact that there are a lot more cases pending there in proportion, behind which quite considerable financial or other interests lie. Also, the parties use every opportunity to enforce them regardless of the higher appeal fees.

Another explanation lies in that apart from the Central Hungarian Region, there is a relatively small number of panels operating in courts of law in a specific division; therefore, establishing uniform practice is facilitated depending on which district courts may adjust themselves more easily. That is why the rate of successful appeal will be lower, which may weaken the litigants' willingness to appeal.

This explanation is contradicted by the fact that among the district courts operating at the venue of certain courts of law in the country, there is a considerable variation regarding appellate rates (the disparity amounted to as high as 80% between the counties with the highest and lowest ratio in the first half of 2014). This situation may be traced back to two reasons to the best of our knowledge. On the one hand, it is possible that there are consistently and less consistently deciding second instance panels. Where appellate divisions function more consistently, the number of lodged appeals are smaller because of the above reason. The other possible reason may be that there really is a quality disparity among the justice quality of certain district courts and the higher appeal ratio, which constitutes one of the manifestations of the dissatisfaction of the clientele.

Personal assessment

The quality of dispensing justice, on the other hand, is ensured by the assessment of the work performed by specific judges. Pursuant to the statute in effect, as a general rule, judges are assessed within 3 years from their appointment and every 8 years following it.[33]

During assessment, the competent chief justice of the division (or the person appointed by him) shall assess the judge's substantive, procedural and case managerial law application and trial conduct practice. The annual activity of the judges shall be assessed in a statement based on caseload and activity-related data as well as second instance and review decisions, which shall be taken into consideration during overall assessment. Apart from this, a certain number of final judgments rendered by the judge shall be examined and panel justice notes prepared in the examined period shall be obtained (which is an

- 16/17 -

assessment made by the chief justice of the appellate division reviewing appeals) as well as the opinion of the division chief justice competent in the legal area (if that person is different from the person conducting the examination).

The judges' professional activities are therefore assessed by their immediate professional superior who knows them personally as well as on whom their professional advancement is decisively dependent. This situation raises the problem that apart from the detailed assessment criteria (National Council of Justice Policy No 4 of 2011), the assessor's personal opinion on the examined judge may play a role in the assessment. The subject of the assessment is encouraged to align his or her judicial activity predominantly to the viewpoint of the reviewing second instance panel as well as its judicial style (even regardless of his or her opposing professional convictions).

This assessment method may just as easily lead to the atomization of legal practice. Since only a fragment of all incoming cases at district court level is reviewed by the Curia, the direction of legal practice conducted in the majority of cases is preponderantly determined by the conceptions of the specific judges employed at a specific court of law. The assessing judge is also from the ranks of the appellate judges reviewing the cases of the assessed judge; therefore, the judicial qualification mechanism may promote divergence of court of law practice. This is especially true for questions of judicial activity that are typically not subject to review by the Curia (e.g. trial conduct style, evidence practice or even sentencing).[34]

For the sake of excluding prejudice and exacting a uniform application of the law, an evaluation of the judicial activity should be carried out based on the best system during the quality examination of scientific publications. Therefore, assessment of judgments rendered by the judge could be trusted to professionally renowned fellow justices functioning at other courts of law, who would give their opinion on the particular judge's work based on disidentified decisions (perhaps case documents). This way, disparities of legal practice within a country may be brought to the surface more easily apart from the objective assessment of the particular judge. This kind of blind peer-review system could bring full awareness to dispensing justice.

Personal and structural factors influencing the quality of justice

Personal composition of the judiciary staff

High quality justice may not be guaranteed by even the best quality assurance system if the qualifications of the judges are unsuitable. Nevertheless, the professional preparedness of a particular judge and the degree of practicing judicial virtues cannot be measured. Thus, inferences may only be made from factors that suggest something about the judiciary. If, however, the legal sociological tenet is accepted that judges do not administer justice "in a vacuum" and certain sociological and social-psychological

- 17/18 -

patterns may be applied to them, such an approach may be considered an asset. Among others, it may be examined as to what the age distribution, gender rate and financial situation of judges are, as well as to what extent a society's ethnic minorities are represented in judicial bodies.[35]

As for the Hungarian judiciary staff, few reliable data exist. One set is about the age distribution of judges. According to it, in 2012 more than half of the local judges trying the vast majority of cases were relatively young with less than 10 years of practice (Table No. 5). This ratio may explain in part, for example, the "prosecution-friendly" feature of the Hungarian criminal judicial practice (success rate of indictment has been 96-97% for years).[36] A younger and less experienced judge obviously listens more to the public prosecutor and respects the facts in the indictment rather than expose himself to the danger of being mistaken. Reducing the retirement age of judges from 70 to 62 years of age as of 1 January 2012 increased the rate of these judges together with its consequences.[37] Generally speaking, it can be established that it does not raise the standards of dispensing justice if a considerable part of the judiciary vanishes from the system from one day to the next with special regard to the fact that no research and experience supported that judges between 62 and 70 would have given a weaker performance in any field than their younger counterparts.

Table No. 5:

Distribution of judges based on practice time in Hungary

(the author's own compilation based on annual NOJ reports)

| 0 to 10 years (total) | over 10 years (total) | 0 to 10 years (at district courts) | over 10 years (at district courts) | |

| 2012 | 1,009 | 1,758 | 842 | 831 |

| 2013 | 990 | 1,817 | n/a | n/a |

| 2014 | 1,087 | 1,728 | n/a | n/a |

It constitutes a further danger that, expressly or implicitly speaking, the current career chances encourage judges with outstanding abilities and ambition to attain the highest possible level in the judicial hierarchy. Thus, it is encoded in the operation of district courts that a large number of judges with short periods of practice will dispense justice,[38] and they will have to tackle the problems of fact-finding, trial procedure and primary construction of legislation. In comparison, judges working at higher levels do not function

- 18/19 -

or do so only within a very curtailed scope as fact-finding courts; in fact, they review the work of judges operating at a lower level.

District court judges with little practice are further burdened with the fact that we live in a more and more complicated and specialized world, which is reflected in the composition of cases brought before court. At the inception of the modern justice structure (in the 19[th] century), an adequate legal expertise and a general experience in life was sufficient to adjudicate a typical case. However, nowadays, scores of legal problems reach the court which need specialist (e.g. economic, financial, accounting or IT) knowledge to understand their facts or establish liability. Judges are generally devoid of such knowledge and the Hungarian procedural law does not know concepts and procedures which could aid a judge's work (the judge may appoint an expert; however, asking the questions directed to the expert would require appropriate specialist knowledge). Thus, it is encoded in the system that complex high-profile cases drag on and completely different decisions are reached at different levels of the judicial hierarchy, which may result in the weakening of trust in courts.[39]

The situation is rendered more precarious by the fact that district court judges have to proceed as sole judges while at second and third instance courts dispense justice in panels consisting of special judges. Due to the above-mentioned specificities of the first instance procedure, however, it is the first instance sole judge that has to pay attention to a variety of factors in a concurrent fashion, while the second and third instance procedure is less energy-consuming since the direction of the appeal determines the focus of the examination. With respect to all of this, it may seem a waste that the professional and political machinery responsible for the judicial system and procedural rules maintains the current structure.

A more reasonable solution to the problem would mean that first instance courts would administer justice in panels consisting of three special judges, thus, the workload would be shared among them and there would be a lower risk of judges "overlooking" anything. However, the chances would increase that the appellate court should affirm the trial court decision, also triggering the depletion of appeals made. Therefore, at courts of second and third instance a smaller judiciary staff would seem sufficient and the consolidation of legal practice would also become more efficient.[40]

The notion of the career judge is associated with this area. One may become a judge in the Hungarian judicial system and the typical way of becoming one is that one starts working at court as a court aid, then a court secretary and waits until the appointment arrives.[41] It is not a requirement that one should acquire experience in other legal professions for at least a few months (e.g. with a lawyer or at another law enforcement body). However, a number of ex-judges who are now attorneys state that if they returned to the judges' bench, they would view some cases in a different way since they now have experience which they did not have previously while working as judges. With regard to

- 19/20 -

the above, one should not discard the solution that would prescribe that judges spend some time in other legal areas prior to appointment (mostly as attorneys).

Apart from the length of time spent in judicial practice, another empirical fact that describes the composition of the judiciary staff relates to gender ratio. Prior to the regime change, one of the main problems of the profession was that it was thought to have become overly feminine. One reason for this was the predictability of the judicial profession compared to the hectic but more lucrative work of attorneys. Thus, working in the judiciary was particularly favored by women, as it allowed them to have a challenging profession, which at the same time did not force them to neglect their families, either. The situation has undergone some changes since the 90s; however, female dominance in the profession may still be observed. Almost 70% of judges working at local and county courts are women (according to relevant data, it has been fluctuating between 68 and 70% for years).[42] This rate is interesting because there may be substantial disparities in vision and commitment between a man and a woman in considering specific cases.[43] The financial situation of judges and the quantity of cultural capital at their disposal may constitute a factor having an indirect effect on administering justice. In Hungary, no survey concerning the social strata from which members of the judiciary staff were recruited has been carried out since the regime change. That is why there are few sources at our disposal if the social background of Hungarian judges is brought under analysis. Perhaps it is due in part to the lack of empirical examinations that two polar opposite points of view - without any particular factual support - formed a few years ago regarding judges' political views. Béla Pokol writes that the majority of the Hungarian judiciary staff have social-liberal inclinations,[44] while Gáspár Miklós Tamás says that a considerable number of judges professes extreme right-wing views.[45]

No survey has been carried out in Hungary concerning the financial situation of the judiciary staff that might permit a determination of their social status. Pursuant to a statutory provision,[46] each judge shall provide a wealth declaration; however, it never reaches the public. The sole indicator which may give rise to assessing the judges' financial situation is their remuneration. Generally speaking, it can be said that the judiciary staff was underpaid before the regime change. Measures were first taken to improve the situation in 1992, and the judicial remuneration was further increased by the 1997 justice reform.[47] The next giant leap was taken by the more than 50% raise in remuneration in 2003 executed in two steps.[48] With this, the Hungarian judiciary staff took a relatively prestigious place among the new Member States that acceded to the

- 20/21 -

European Union on 1 May 2004.[49] The remuneration of judges did not reach that of more renowned attorneys; however, the steady and considerable income compared to other state employees now ensured an appropriate livelihood.

However, the basic judicial salary has only increased by 11.72% in the past 10 years.[50] In 2015, the gross salary of a new judge appointed to the lowest rank of the judicial hierarchy amounts to HUF 430,760 which, reaching the highest step (if he or she does not receive any managerial title supplement, or is not appointed to a higher level court), will have topped at HUF 724,460 by the end of his or her career. It is worth comparing the 2014 gross average salary of university graduate employees to these figures, which is HUF 477,567.[51] It is no coincidence that in the 2012 CEPEJ rating the Hungarian gross judicial average salary remains the penultimate one among EU Member States.[52]

Thus, the starting judicial salary may not be deemed really appealing compared to other professions. Another non-negligible circumstance is that one may receive judicial appointment only after turning 30; therefore, one may have to make do with an income that is inferior to a staring judicial income for 5 to 7 years or even for a longer period following graduation from university.

In addition, the unfavorable payment status involves two risk factors. One of them is the danger of negative selection: the responsible judicial activity of practicing public power that also involves a serious intellectual challenge would require that only the most outstanding person should choose the judicial profession. However, with such remunerative conditions, the judicial profession will become less and less attractive, especially in regions where the graduate average income is inherently higher (the Central Hungarian Region and the Western Trans-Danubian Region).

The other serious danger is that the risk of corruption will be enhanced. An underpaid judge deciding in a high-profile case is only protected by his or her own personal honesty from illegitimate attempts at influence in proceedings where classic procedural and organizational solutions (public accessibility of the hearing, adversarial process, corrective mechanisms and joint justice) do not prevail or do so only in a limited way (company proceedings, prolongation and review of custody pending trial, winding-up proceedings, etc.). A responsible legislator should struggle to reduce the chance of corruption with every means possible. One side of this would include a salary commendable to the profession and the accompanying responsibility.

Obviously, one may not establish a direct correlation; however, it is a thought-provoking fact that criminal prosecution was initiated against three judges charged with bribery. One final criminal conviction has been rendered so far.[53]

- 21/22 -

Conclusion

This study attempted an evaluation of the Hungarian judicial system. It is considered that efficiency and quality judgments encompass the two hubs that best reflect the current state of the judicial system; however, any method suitable for international comparison only remains limited due to differences in the judicature of national legal systems. The disclosed data reflect an ideal state in some points and without any background information they show the image of an exceptionally efficient justice system. That Hungary ranks seventh place regarding the number of judges per 100,000 inhabitants at EU level may be considered so. Also, an efficient justice system is reflected in the end period of litigation: while sixth in civil and commercial divisions, Hungarian courts rank fourth in administrative division among EU Member States. These data seem excellent especially in light of the budgetary support of Hungarian courts being rather low as compared to the general European level. Court expenditure per 100,000 inhabitants merely ranks Hungary in the 18th place. This study pointed out that the above indicators are misleading and, in order to resolve this, the only solution would involve the establishment of a Pan-European uniform assessment methodology. The current system encourages Member State court management to improve on the surface indicators if it expects to achieve good results, which is far simpler than achieving the goal that cases be heard thoroughly, yet within a reasonable time limit.

It is a more serious problem that political leaders may "sell" the curtailing of institutional and personal autonomy of the judicature as a necessary step towards creating a high standard, efficient and client-friendly administration of justice. With regard to this context, what may be forecast is that strong pressure will be placed on courts in Hungary in the future in order to show continuous improvement concerning measurable parameters.

One of the means of political pressure may lie in the regulation of the levels of judicial remuneration. It was pointed out that the lack of financial acknowledgement of Hungarian judges constitutes a realistic danger of prejudice to judicial independence. In the 2012 CEPEJ rating the Hungarian gross judicial average salary remains the penultimate one among EU Member States. This, however, implies the realistic possibility of negative selection and corruption whose signs already loom on the horizon.

- 22/23 -

Összefoglaló - Badó Attila - Bencze Mátyás: A magyar igazságszolgáltatás színvonala európai kontextusban

A tanulmány a magyar igazságszolgáltatás színvonalának empirikus módszerre alapozott értékelésére vállalkozik. Az 1997-es, a bírósági hierarchia rendszert, a bíróságok igazgatását, és az eljárásjogi keretet is alaposan megváltoztató reform még az európai uniós csatlakozásra készülés jegyében zajlott, és kifejezetten európai mintákat követve kívánt az igazságszolgáltatás minőségén javítani. A 2010-ben hatalomra jutó Orbán kormány immár Uniós tagként valósított meg egy olyan reformot, ami nemzetközi szervezetek, Uniós intézmények erőteljes kritikáját váltotta ki. A reform egyes, a bírói függetlenséget féltők tiltakozását kiváltó elemeit a törvényhozó a minőségi, hatékonysági szempontok előtérbe helyezésével indokolta. A minőség és hatékonyság mérése és más országokkal való összevetése igen nehéz vállalkozás, ami az egyes jogrendszerek igazságszolgáltató rendszereinek különbségére vezethető vissza. A módszertani nehézségek ellenére mégis kísérletet teszünk arra, hogy a magyar igazságszolgáltatás állapotáról kórképet készítsünk, és ahol lehetőség adódik, az uniós országok igazságszolgáltatásának állapotával összemérjük. ■

NOTES

[1] This objective is also embodied in the strategy of the National Judicial Office (NOJ), entrusted with the administration of courts. See http://birosag.hu/obh/strategia

[2] For the more important European initiatives, see http://www.iias-iisa.org/egpa/groups/permanent-study-groups/psg-xviii-justice-and-court-administration/ and http://www.iacajournal.org/index.php/ijca. For books and studies see: Philip Langbroek: Quality Management in Courts and in the Judicial Organisations in 8 Council Of Europe Member States, Council of Europe Publishing CEPEJ studies, Strasbourg, 2011; Marco Fabri, Philip Langbroek (eds.): The Challenge of Change for Judicial Systems: Developing a Public Administration Perspective, IOS Press, Amsterdam, 2000; Gar Yein Ng: Quality of Judicial Organisation and Checks and balances, Intersentia, Antwerp, 2007. In Hungarian literature, this trend is represented by Fleck, Zoltán (ed.): Bíróságok mérlegen I-II., Pallas Páholy, Budapest, 2008; Hack, Péter - Majtényi, László - Szoboszlai, Judit: Bírói függetlenség, számonkérhetőség, igazságszolgáltatási reformok, Budapest, http://www.ekint.org/ekint_files/File/tanulmanyok/biroi_fuggetlenseg.pdf

[3] In Europe, the two most renowned projects are "The European Commission for the Efficiency of Justice" (CEPEJ) and the "EU Justice Scoreboard." See http://www.coe.int/T/dghl/cooperation/cepej/default_en.asp and http://ec.europa.eu/justice/effective-justice/scoreboard/index_en.htm

[4] J. A. G. Griffith: The Politics of the Judiciary. Fontana Press, London, 1997.

[5] For instance, the published work edited by Zoltán Fleck as referred to in Footnote 4 analyses and evaluates the Hungarian system of judicial bodies and its operation in two volumes totaling 750 pages.

[6] With regard to the above and obvious limitations in volume, various and nonetheless significant areas are knowingly left untouched. They include the state of lay participation in dispensing justice, the unique position of the Metropolitan Court, the problems arising therefrom or even the relation between courts and the public. Although these issues are timely and relevant from a practical point of view, their inclusion is deemed to merely fine-tune the overall picture displayed following the analysis of the previous two problematic areas.

[7] See http://birosag.hu/obh/elnoki-beszamolok/feleves-eves-beszamolok

[8] See the data figuring in Chart No. 2.

[9] For this, see Darák, Péter: Sarkalatos Átalakulások - A bíróságokra vonatkozó szabályozás átalakulása. MTA Law Working Papers, 2010-2014 (http://jog.tk.mta.hu/uploads/files/mtalwp/2014_39_Darak.pdf) and Bencze, Mátyás: A bírósági rendszer átalakításának értékelése. MTA Law Working Papers, 2014. (http://jog.tk.mta.hu/uploads/files/mtalwp/2014_41_Bencze.pdf)

[10] In Footnote 4, according to the data acquired from EU Justice Scoreboard, see http://ec.europa.eu/justice/effective-justice/files/justice_scoreboard_2015_en.pdf

[11] Based on data acquired from EU Justice Scoreboard.

[12] Based on data acquired from EU Justice Scoreboard. Budgetary support of courts has developed as follows: 2011 - HUF 69.3 billion, 2012 - HUF 79.4 billion, 2013 - HUF 84 billion, 2014 - HUF 87 billion, 2015 - HUF 87.5 billion.

[13] There exists no accurate data as to the rate of replacing retired judges at a specific court following mandatory retirement in 2011. If this occurred in a territorially disproportionate manner, it is possible that this triggers the prolongation of the time needed to resolve cases.

[14] See the report on the NOJ's president: http://birosag.hu/sites/default/files/allomanyok/obt_dokumentumok/osszefoglalo_20150609.pdf

[15] There are statistics in existence concerning the method of resolving a case (http://birosag.hu/sites/default/files/allomanyok/media-lapszemle/stat-adatok/4_hosszu_elemzes_2012_kesz.pdf), showing that in the civil division in Hungary only a little more than half of the cases are resolved on the merits.

[16] A warning for this danger is presented by Jakab, András: A jogállamiság mérése indexek segítségével. [under publication].

[17] Sections 42 and 46 of Act XCIII of 1990 on court fees (Fees Act). Earlier, if the matter in dispute amounted to HUF 20,000,000, court fees of the first instance together with the appeal topped at HUF 1.8 million, which has now risen to HUF 3.1 million (with the rate of the duty on an appeal proceeding increasing from 6% to 8%). It would be a mistake to think that such a litigated amount arises in the lawsuits of otherwise wealthy parties. Applying for a housing loan for such a sum that becomes disputed later on may occur easily in the case of an average middle-class family as well. The HUF 3.1 million court fee is a disproportionately huge sum that may prevent enforcing claims through judicial channels even if a certainty of winning the suit seems plausible - especially if the solvency of the losing party is not ensured.

[18] Section 6 of the Decree No. 6/1986 (VI. 26.) IM of the Ministry of Justice.

[19] Section 58(1f) of the Fees Act.

[20] Section 73/A of the Act III of 1952 on the Code of Civil Procedure (Civ.Proc. Code).

[21] Section 73/B (1) of the Civ.Proc. Code.

[22] That is also why it is a worrying fact that during the codification of the new civil procedural code no comprehensive survey was carried out regarding the opinions of clients of the new regulation and how they respond to the fact that enforcing their rights and lawful interests becomes all the more difficult.

[23] Section 279(4) of the Act XIX of 1998 on Criminal Proceedings (Crim.Proc. Act).

[24] Section 85(5) of the Crim.Proc. Act.

[25] The latter may violate the principle of effective defence, since the substitute may not be able to carry out defence as professionally as the counsel authorized by the defendant. Section 50(1e) of the Crim.Proc. Act

[26] "... by assignment of the president of the National Judicial Office, 160 cases of the Budapest-Capital Regional Court of Appeal were resolved at the [Debrecen] Regional Court of Appeal in addition to their own tasks. Lajos Balla added that assignment shall continue, since between 1 September 2015 and 30 August 2016 the Debrecen Regional Court of Appeal helps the Budapest-Capital Regional Court of Appeal with resolving bankruptcy and liquidation proceedings." See http://birosag.hu/media/aktualis/szeleskoru-szakmai-kihivasoknak-kell-eleget-tenniuk-birosagoknak-sajtotajekoztato

[27] For an overview of the problems see Bencze, Mátyás - Ficsor, Krisztina - Kovács Ágnes: Útkereső konferencia a Debreceni Egyetem jogi karán,. Jogtudományi Közlöny, 2015/9. [under publication].

[28] The Finnish Rovaniemi Quality Project in the field is considered to be such a "pilot" study (http://www.courtexcellence.com/~/media/Microsites/Files/ICCE/QualityBenchmarksFinlandDetailed.ashx)

[29] Apart from being satisfied with the first instance ruling, willingness to appeal may be influenced by the costs of the appellate proceedings (not only financial considerations, but also the invested time, the insecurity due to the pending situation, etc.). Nevertheless, the Rovaniemi Quality Project mentioned in Footnote 28 also applied this indicator.

[31] The source of charts No 3 to 5 is the same analysis: http://birosag.hu/sites/default/files/allomanyok/media-lapszemle/stat-adatok/4_hosszu_elemzes_2012_kesz.pdf

[32] The disproportionately great caseload of the Central Region has been a problem for years, which is reflected in the annual NOJ presidential reports as well. The situation is present in the latest 2014 reports as well: http://birosag.hu/sites/default/files/allomanyok/obh/elnoki-beszamolok/elnoki_beszamolo_2014.pdf

[33] For specific provisions see Sections 71 to 77 of the Act CLXII of 2011 on the Status of the Judiciary (Status Act).

[34] For the latter see Badó, Attila - Bencze, Mátyás: Területi eltérések a büntetéskiszabási gyakorlat szigorúságát illetően Magyarországon 2003 és 2005 között. In: Fleck, Zoltán (ed.): Igazságszolgáltatás a tudomány tükrében. ELTE Eötvös Kiadó, (ELTE Jogi Kari Tudomány 6.) 2010. pp. 125--147.

[35] In the United States of America, for instance, every federal judge is registered according to his or her sex, race and ethnic origin as well as the university (s)he graduated from; therefore, bountiful data are available for sociological analyses. See http://www.fjc.gov/public/home.nsf/hisj Based on these data, feminist legal theory expounded its criticism according to which the judicial practice (and thus the entire legal system as well) reflects the value considerations and views of white middle-class men, which constitutes a serious disadvantage for women.

[36] This is data taken from the Chief Public Prosecutor's annual parliamentary reports.

[37] Based on official sources, this measure concerned a total of 276 judges out of the nearly 3,000 member judiciary staff. http://www.mabie.hu/node/1147

[39] See in more detail Bencze, Mátyás - Vinnai, Edina: Jogszociológiai előadások,. Debreceni Egyetemi Kiadó, Debrecen, 2012, p. 32.

[40] See in more detail Bencze: A bírósági rendszer átalakításának... 2014.

[41] Lamm, Vanda - Fleck, Zoltán: Az igazságszolgáltatás újabb 10 éve - Mit akart és mit ért el az igazságszolgáltatási reform? http://mta.hu/fileadmin/2008/11/17-igzasagszolg.pdf

[42] According to the 2014 NOJ presidential report, the rate of women among the judges was 68% (http://birosag.hu/sites/default/files/allomanyok/obh/elnoki-beszamolok/elnoki_beszamolo_2014.pdf). Unfortunately, the report did not include gender ratio broken down to court level and specific case divisions.

[43] See Footnote 35. However, based on the declaration of a psychologist expert, the hiatus lies somewhere else: there is a more marked difference in the judicial practice between judges without any children and judges who have children. Childless judges have no established opinions on how to raise a child and are more open to different child-rearing methods, especially of those being in different social-financial situations.

[44] Pokol, Béla: A bírói hatalom. Századvég Kiadó, Budapest, 2003. p. 46.

[45] http://www.magyarhirlap.hu/Archivum_cikk.php?cikk=74888&archiv=1&next=20

[46] Section 197 of the Judges' Status Act.

[47] See Badó, Attila - Bóka, János: Európa kapujában. Bíbor Kiadó, Miskolc, 2002. p. 262.[page number]

[48] http://24.hu/belfold/2002/10/09/megegyezes_szuletett_biroi_fizetesek/

[49] Gross judicial average wage was higher only in Slovenia among the newly acceded former "Eastern block" countries. See https://wcd.coe.int/ViewDoc.jsp?Ref=CEPEJ%282006%29Evaluation&Language=lanEnglish&Ver=original&BackColorInternet=eff2fa&BackColorIntranet=eff2fa&BackColorLogged=c1cbe6

[50] http://www.mabie.hu/sites/mabie.hu/files/letp%C3%A1lya%20I-II.r%C3%A9sz-1.pdf

[51] http://nfsz.munka.hu/engine.aspx?page=afsz_stat_egyeni_berek_2014

[52] http://www.coe.int/t/dghl/cooperation/cepej/evaluation/2014/Rapport_2014_en.pdf

[53] See NOJ presidential reports between 2011 and 2013: http://birosag.hu/obh/elnoki-beszamolok/feleves-eves-beszamolok

Lábjegyzetek:

[1] The author is professor of law, University of Szeged, Faculty of Law, Hungary.

[2] The author is professor of law, University of Debrecen, Facultiy of Law, Hungary - A tanulmány az OTKA K120693 azonosítószámú pályázata keretében készült.