Endre Orbán: The Effect of the Financial Crises on the Inner Migration in the European Union* (IAS, 2016/2., 105-125. o.)[1]

1. Introduction

The realization of the European internal market has created a totally new segment of the so-called classical migration theory and patterns. Therefore, it seems to be plausible to differentiate the question of original international migration from the issues concerning the internal mobility within the European Union.[1] The latter might be divided into two further approaches. One can analyze the migration flows either among regions or between Member States.[2]

The entire opening of the European labour market for all Member States that have joined the EU in 2004 or 2007 has been launched on 01 January 2014.[3] By this

- 105/106 -

moment all kind of legal barriers have been lifted which were introduced according to the '2+3+2' formula. In light of the latter formula the 'old' Member States were not required to respect the free movement of workers for two years after the accession of the new Member States. Later, the old Member States could continue their restrictions for an extra 3 years provided that they made a notification to the Commission. And finally, the old Member States in the case of serious disturbance of their labour markets or a threat thereof and after notification of such to the European Commission might continue their restrictive policy for a final 2 year-long-phase.

However, in the same time many negative political statements have come to light. First of all David Cameron, Prime Minister of the United Kingdom has declared the necessity of re-thinking of the free movement of persons;[4] secondly Berlin has become more severe regarding the potential migrant workers and limited the time-period of job seeking;[5] and last but not least, an out-of-EU referendum seems to have a great impact on the inner migration policy: Switzerland[6] has voted in favor of restrictive quotas regarding the European workers.[7]

Therefore this paper aims to analyze the question of mobility which has become such an outstanding topic in 2014. A highly plausible hypothesis is to consider whether the economic crises made the countries to become more closed and less open to foreign employees thus protecting their own workforce market. Therefore it will be assessed how the economic crises has affected the inner migration trends within the EU.

In order to make such an assessment in the next chapter will be presented the theoretical and conceptual backgrounds of migration (Chapter 2); furthermore the underlying freedom of movement of European citizens will be analysed which can be interpreted as a tool to reduce the migration costs (Chapter 3); Chapter 4 presents the data on the factors which might shape the stay or go decisions of potential migrants and formulates the hypothesis; furthermore, it will be assessed whether there is a correlation between the migration data and the financial crises (Chapter 5); and finally, Chapter 6 concludes.

2. The determinants of migration - literature review

2.1. Neoclassical migration theory and its critiques

The phenomena of migration and recently the internal mobility within the European Union has become into the focus not only among lawyers and politicians but also

- 106/107 -

among economists,[8] and sociologists[9] as well. Therefore, the practical administration oriented approach of the lawyers has been backed by many theories which attempt to analyse the underlying trends, causes and incentive structures of migration and try to explain the different migration patterns. Before presenting a few theories and some empirical results it has to be emphasised that the literature concerning migration is far from being conclusive while those relatively little empirical studies which deal with migration seem to be far from presenting robust results.[10] Nevertheless, the classical migration theory might serve useful in order to understand and analyse the European mobility. However, the empirical research concerning the free movement within the European Union is very moderate.

The economic theory of migration and mobility seems to be comprisable into three sub-questions: why people migrate, who migrates and what the consequences of migration are.[11] The current study relates to the first sub-question as it attempts to analyse whether the financial crises had any influence on the factors which shape the migration tendencies. The question of who migrates can be understood empirically as the attributes concerning the typical migrant (in case of Europe young, well-educated, single men[12]) and theoretically as the analysis of the role of self-selection[13] which seems to have less importance in the European context: the freedom of movement and past migration understood as the established social networks decrease the transaction costs relating to mobility. As a consequence, low immigration costs will diminish the self-selection process.[14] And finally, the third sub-question might be understood as the impact of migration on both the immigration and emigration countries.[15] The latter question might involve analyses regarding the effect of migration on the GDP, on the rate of unemployment, and might highlight concepts like brain drain, brain gain or brain exchange.[16]

- 107/108 -

The question of why to migrate finds its root in the work of Adam Smith who has observed the different returns depending on the place where one works.[17] Accordingly, the first economic theories explaining the phenomena of migration find the difference between wages to be their core explanatory variable.[18] In addition, Ravenstein states seven laws which articulate migration flows.[19] Among others, he emphasizes for example the fact that rural population is more likely to migrate, the role of the distance and the attractiveness of cities. Hence, the distance between the country of origin and the host state has an imminent role provided the fact that it will determine the costs of migration. This approach is called the gravity law of migration where the distance between two places functions as a cost-determining proxy.

Later, the model of migration has been extended further. Harris-Todaro have outlined the usage of expected income instead of the income differences between two countries.[20] The underlying reason of this refinement is the presence of unemployment. As it is not sure that a migrant is going to find a job, consequently, it is more useful to calculate the costs and benefits using the sum of the expected income. In addition, Sjaastad has underlined the differences between the costs of living at two different places. Therefore, in order to decide about leaving a country not only with the costs of migration but also the differences between the costs of living must be deducted from the expected income.[21]

The previously mentioned theories seem to be quite easy to apprehend. However, the reality confirms them only partially. Notwithstanding the fact that wage differences have a huge explanatory power in terms of migration, one must notice that such a simplistic incentive structure would cause that most of European people should live in the northern and western part of the continent today. This conclusion, however, does not exist which might have different reasons.

First of all, one might think about the convergence effect of migration. From a macroeconomic perspective, once people migrate from one country to another the loss of labour supply in the original country will push up the level of wages, while in the destination country the consequence should be the opposite. Thus, a convergence in wages will occur which will lead to an equilibrium where no more migration takes place.[22] Yet, again despite the explanatory power of this theory one might be suspicious whether migration had ever produced such a result in reality therefore, it worth to look after other explanations as well.

- 108/109 -

A critique which might be raised against the simplistic rational theories based solely on the wage differences is the question of its individualistic view. Mostly family members decide together whether they migrate or not. Even if in case of one of the family members the wage-based theory is applicable, it does not offer any explanation for the decision of the rest of the family members. Therefore the costs of the whole family should be included into the cost-benefit analysis so the net gain of one family member must exceed the total costs of migration and the loss of income of other family members. Nevertheless, it might happen also that the family sends on purpose only one of its members abroad in the hope of remittance payments which has the function of diversification of the family incomes.[23]

Another approach handles migrants as consumers. This view goes back in the Law and Economics literature to the theory of Tiebout who constructed the idea of 'voting by feet'.[24] The underlying idea of this concept is that different territories have different characteristics such as climate or clean air. Therefore, the migrant chooses between two places according to what they offer. In the theory of Tiebout the provision of public goods is the relevant factor. People might choose to emigrate if they find a place with lower taxes and better public goods or for example people might prefer to emigrate from a dictatorship to a democratic society, from a place characterized by low quality of life to a place where the average quality of life is higher. This approach might have strong connections with other theories which underline the importance of life cycles.[25] In the latter view deciding about migration is not a simple one-shot game but it is the function of age. Young people tend to choose places with challenging high paid jobs and dynamic cities while pensioners might value more the climate and the calm of a village in Southern Europe ('sunset migration'[26]).

Furthermore, another critique takes into his center the role of uncertainty. The simplistic neoclassical model assumes perfect knowledge about the destination country and the job perspectives of the migrant. However, this is unlikely to be true. The migrant must face a huge lack of information therefore he or she has to invest a lot of search costs in order to reduce this uncertainty. The latter issue has more relevant consequences. First of all, the need for information raises the total migration costs which might undercut the net gain of migration. Secondly, the risk attitude of the migrant will have a huge importance. Risk averse people will tend to value more their secure home countries compared with their risk neutral and especially risk loving fellows.

In this context, sociologists have drawn attention to the relevance of kinship and migrant networks.[27] Namely, their existence might radically decrease the level of uncertainty and information costs. In economic terms, these social networks serve as

- 109/110 -

a 'migration insurance'[28] which defend migrants from the unnecessary expenses. In addition, as a network at one destination country grows one might find more obvious to immigrate to that territory even if the potential net gain at another destination (but together with higher level of uncertainty) might be higher ('chain migration'[29]).

2.2. Push and pull factors and the role of transaction costs

In the light of the theories mentioned it seems to be useful to turn to a broader conceptualization of the phenomena of migration which might allow us to incorporate many aspects analysed above. Consequently, it seems to be useful the introduction of the sets of 'push' and 'pull' factors which might shape the migration decisions. In addition, two other sets might be relevant to consider: the sets of 'stay' and the sets of 'stay away' factors.[30]

The pull factors denote those incentives which attract the potential migrants. For example a pensioner in the United Kingdom might think attractive to move under the sunny climate of Spain or an expected high wage in Germany might be tempting for an engineer in Poland. On the contrary, the push factors cover those elements which might mean strong arguments on the side of leaving a country. Accordingly, the harmful social atmosphere or the lack of human rights might create the feeling that one cannot live further in a particular country. The stay factors denote those elements which are in favour to remain in a particular country. Among others, one might think about the social embeddedness[31] or the role of family ties. All these elements can be translated as psychological costs which accompany a decision of leaving. On the contrary, the stay away factors are a bit less relevant as they are taken into account only as dissociating arguments relating to one particular place which, however, does not hinder anyone to go to a third destination country.

All in all, the decision of migrating depends largely on the push, pull and stay factors. The latter element can be incorporated in the broader concept of migration costs or transaction costs of migration which is always taken into account in the cost and benefit analysis of migration decisions. Therefore, the size of transaction costs has an imminent role as it will highly influence whether the decision to migrate will be followed by a net gain or a net loss of wealth. Accordingly, high transaction costs might hinder migration while lower transaction costs make migration easier and more attractive.

To contextualize, contrary to the conditions surrounding the emergence of the early neoclassical theories, nowadays for example the so-called 'Ryanair-effect' has

- 110/111 -

decreased the concrete expenses of migration. As a consequence, the role of distance between two countries seems to be less relevant. In addition, the different channels of social media (such as Facebook groups of immigrants) further decrease the level of uncertainty in an impressive manner. All these decreasing costs raise the question again why people do not migrate in an even huger mass. One potential answer to this question puts into the focus of the analyses the role of immigration policies. Yet the different administration costs have a huge impact on the decisions to migrate or not. However, this is one of the most important distinctive elements which differentiate the European mobility from the classical migration. While a so-called 'third country national' has to face with many administrative obstacles in order to entry and reside in an EU Member State (entry visa, border control, long-term work permit, transferability of skills understood as the recognition of qualifications, internal controls, residence permit and so on[32]), citizens of the EU Member States enjoying their European citizenship have a different legal position. Thus in economic terms, one can interpret the free movement of people within the EU as an attempt to decrease transaction costs which influences the internal mobility.[33]

In order to enlighten the importance of the low mobility barriers within the European Union another relevant theory can be mentioned. The classical migration literature draws attention on the fact that from poor countries many people do not immigrate despite their willingness just because they do not have enough resources. At a later level of development a family might have enough resources to send one of the family members abroad who will return part of his or her earnings to his or her family which step by step raises the wealth level of the family. The aggregate pattern of this theory can be illustrated as a reversed U shaped curve which states that migration will increase together with economic development up to a certain point where people tend to value less attractive to leave the country and the migration pressure will decrease.[34] In European context this theory suggests that taking into account the GDP gap among the western EU15 and the new Member States the flow from east to west had to increase by nature after the enlargement of the Union depending on the point of the reversed U shaped curve where the economic development of the new Member States is. However, such a theory should be assessed empirically. At this point of the analysis it is fair enough to underline the existence of a potential migration flow from east to west which might have been aggravated upon the enlargement of the EU.

- 111/112 -

2.3. Some empirical findings

Before presenting the legal solution applied in the European Union a few empirical studies should be presented. However, one must deal with many of these empirical researches having a critical approach. Besides the fact that immigration data is mostly far from being accurate and it is difficult to compare the data provided by different countries, some researches focus on one single country. Regarding the European states Hatton for example has analysed the immigration trends to the UK which has become a net destination country during the seventies. According to his findings, the most significant reasons for migration were unemployment rate and income differences among the countries, while less significantly but also the income inequalities in the UK has been found relevant as it tended to decrease migration flows.[35]

Lewer and Van den Berg have introduced the role of past migration (as the number of source country natives who already live in the destination country) and variables of language and culture (as colonial heritage) next to contiguity in the so-called augmented gravity model. They have found that all of the first three variables are highly significant. However, the common border seems to be less relevant. According to them the most likely reason of the latter finding is "the freedom of movement within the European Union [where] it is just as easy (or difficult) for a Russian immigrant to move to Germany as it is for her to move one country further."[36]

And finally regarding the European Union one must consider the findings of Brücker et al.[37] and Brücker-Eger.[38] Their analysis pays attention on the consequences of internal mobility and also on the dispersion of migrants. They find that migration has a positive economic effect in the long run equal with 0.2% in the EU15 countries while its impact on the wages and unemployment rate is more moderate. As regards the age and skill structure of migrants, the younger generation seems to be overrepresented among the migrants as compared with their proportion among the stayers in the country of origin. Furthermore, and according to the Borjas model,[39] the higher the proportion of the high skilled people is the more of them leaves the country. However, the freedom of movement diminishes the effect of self-selection and also low skilled people tend to migrate. The overall assessment draws attention on the ageing workforce of the emigrant Member States and on the outflow of the most skilled population. Nevertheless, they estimate the expected amount of migration for 2020 which will hardly reach 3.1% of the total population of the European Union. However, they underline that there was a huge

- 112/113 -

decline in the number of immigrants in 2008 which they assume to be a consequence of the financial crises.

And finally, coming back to the present policy debate between Brussels and London which has put into the political focus the freedom of movement one might mention the analysis of two institutes from London.[40] According to their findings the curbs on the European migration would cause 50 billion pounds loss by 2050 which is equal with 2% of the British GDP. The latter number on the one hand suggests that it is quite damaging politicalizing the achievements of the internal market. On the other hand, it underlines and confirms the importance of the free movement of persons within the European Union.

3. The free movement of persons of the European Union

3.1. The freedom of movement as a legal institution

The regulation of the freedom of movement can be found on both layers of the law of the European Union, both in the primary law (Treaty and case law) and in the secondary law (regulations, directives).[41]

The freedom of movement can be traced in three different aspects of the internal market rights: free movement of workers, the freedom of establishment and the freedom to provide services. The delimitation of these terms is provided by a couple of dichotomies. The free movement of workers refers to a temporary stay on the territory of another member State, while the freedom of establishment has a permanent character. In addition, the freedom to provide services involves that the provider is supervised from his country of origin, while in case of free movement of workers the control rights belong to an entity which is located in the host country.

According to Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union "Freedom of movement for workers shall be secured within the Union."[42] This economic freedom is one of the four basic freedoms which were devoted to create the internal market in the territory of the EU. The regulation of this freedom is structured as follows: one might find the general rule quoted above as a purely economically motivated rule as it is restricted for the workers. The next paragraph connects the freedom of movement with the principle of non-discrimination based on nationality while the paragraph 4 gives an exception under the non-discriminatory principle for the case of public service employment.

There are two other directions of the regulation. The first one is the list of the potential restrictive arguments which may be used by the Member States in order to limit the freedom of movement. These are public policy, public security and public

- 113/114 -

health.[43] All three grounds of limitations are subject to judicial control which claims to satisfy the so-called test of proportionality[44] in order to rely successfully on one of the three restrictive arguments.

The other relevant direction of the regulation is again in connection with the interpretative power of the Court of Justice of the European Union [further: ECJ]. The Court does not only determine the sphere of application of the above mentioned restrictive measures, but it has also developed other restrictive possibilities, the so-called 'mandatory requirements'.[45] The corollary of this legal development was that not only the directly or indirectly discriminating measures had to face the judicial review of the ECJ but it ruled out that any kind of obstacles which might hinder the effective functioning of the rights provided by the Treaty has to be in accordance with the test of proportionality. A strong proof of this legal development are the D'Hoop,[46] or most recently the Kranemann and Turpeinen cases[47] where the ECJ has declared that the right of free movement can be violated even in the country of origin if the country punishes its citizen because he or she was using his or her rights provided by the Treaty.

In addition, the ECJ has broadened through interpretation the terms of the Treaty. Thus the ECJ has widened step by step the scope of application of the Treaty even for non-economically active migrants (tourists,[48] students[49]) which was backed by the introduction of the concept of 'European citizenship'[50] by the Maastricht Treaty in 1992. This process has unloosed the freedom of movement from its initial economic purpose. A prominent point of this legal development was when the ECJ has connected the right of free movement through the principle of equal treatment with the social

- 114/115 -

benefits.[51] From a Law and Economics perspective this point enables the researcher to refer back to the theory of Tiebout[52] and ask whether the different social services might function as an incentive for the European citizens to change their place to live. Accordingly, many scholars and nowadays politicians have also questioned whether this could lead to a kind of social welfare tourism among the Member States.

The second layer of regulation of free movement of persons has evolved in many steps since the Treaty of Rome has introduced this freedom in 1954. At present there are two important legal tools which have to be mentioned here. The first one is the so-called Citizens' Rights Directive[53] which regulates in detail the different possible periods of stay of the European citizens in another Member State. In the light of the directive, citizens have the right to stay freely in another Member State without any additional administrative act up to three months. Even for a longer period there is no need for a residence permit but the citizens must register in the new host state which will issue a registration certificate. The latter, however, is subject to some conditions. In order to acquire the certificate the applicant must be either engaged in an economic activity or he or she must have a health insurance together with enough resources which ensures that he or she will not become a burden on the social system of the host Member State. As a final step, after a five-year-long legal stay citizens acquire the right for permanent residence.

The second relevant legal act is a directive on the coordination of Member States' social security systems[54] which for example gives answer for the question of how to calculate the pension eligibility of a citizen who has been working in different Member States and was paying taxes to different social security systems accordingly. The importance of such a coordinative legal act has already been identified in the seventies. Referring back to the economic theories this directive neutralizes many uncertainty factors of the European mobility which otherwise would discourage potential migrants to move.

Nevertheless, as it has been pointed out, the freedom of movement of workers might have a temporary character. Migrant workers with or without families might simply go to another Member States and find there a job for a specific period of time. What happens if they never want to return? According to Article 45 paragraph 3 the freedom of movement entails not only the right to accept offers of employment, to move freely within the country and to stay there for the purpose of a work but also "to

- 115/116 -

remain in the territory of a Member State after having been employed in that State, subject to conditions which shall be embodied in European regulations adopted by the Commission." In addition, another relevant aspect of the right of free movement can be found in the Articles 49 to 55 which regulate the freedom of establishment. This clearly regulates not only the temporary stay in another Member State but the right of a European citizen to choose another Member State as his or her new home country. However, this freedom is again strongly connected to the economic activity and this character was not dissolved by the judgments of the ECJ. The relevance of this right mainly consists in the field of corporations and in the right to pursue activities as self-employed persons.

In order to make self-employment easier the text of the Treaty emphasizes the principle of mutual recognition of diplomas and other qualifications and the necessity of coordination of the provisions of the Member States regarding "the right to take up and pursue activities as self-employed persons"[55] Consequently, a regulation has been launched on the recognition of professional qualifications. Referring back to the economic theories the function of such a regulation relates to the question of skill transferability. As the signaling process of jobseekers might be hindered if their diplomas are not acknowledged to be equal with the native diplomas this would decrease the general willingness to immigrate. In addition, a further negative consequence of non-recognition is the phenomena called underemployment which leads to brain waste and loss in productivity.

3.2. The freedom of movement as an economic tool

3.2.1. At individual level

The whole European project started to develop as an economic cooperation in the fifties. One of the core elements of the integration today is the functioning of the internal market through the four basic freedoms. The underlying economic approach of this institution is clearly highlighted in the wording of the Treaty[56] when it empowers the European Parliament and the Council to issue directives or make regulations to ensure close cooperation between national employment services, to remove administrative borders between States, to abolish qualifying periods which hinder free choice of employment and to establish transnational contacts between employer and employee in order to "facilitate the achievement of a balance between supply and demand in the employment market in such a way as to avoid serious threats to the standard of living and level of employment in the various regions and industries."[57]

- 116/117 -

If we recall the basic idea of the Coase theorem it can be pointed out the relevance of the introduction of such rules. Workers of a country can be highly motivated to seek a job in another Member States for example thanks to the higher payments, or higher expected payments. However, moving from one country to another entails a lot of migration costs. As it can be seen above among the theories concerning migration, Harris-Todaro point out that people will migrate if the expected income gains from migration exceed the migration costs. These migration costs have many components,[58] among which there are the high administration costs which can be reduced through the elimination of the legal barriers. The latter objective is served by the creation of the right to free movement. However, one must bear in mind that the fact that legal barriers have been eliminated it does not mean that all de facto obstacles have ceased to exist. The relevance of the latter is highlighted also by the European Commission which has published its Citizenship Report in 2010 and 2013 as well. The Commission has listed many practical obstacles which might hinder the internal mobility within the European Union and has also developed action plans to handle these issues.

3.2.2. At state level

The aggregated impact of a huge inner mobility might be quite significant. It is enough to refer back to the macroeconomic model of migration and its assumed impact on productivity, wages and unemployment. Such an impact can be justified under Kaldor-Hicks if the aggregated gains of the winners outweigh the losses of the losers. However, at this point turns out to be relevant not only the aggregated gains and losses of the migrants but also the net benefits of each Member States should be taken into account. Therefore, papers have been published which have analysed the economic impact of the inner migration in the European Union,[59] while critical voices have touched the sensible question of the social security systems and politicians state that many European citizens misuse their right in order to get better social care.

The fear of country-level labour market disturbances can be read out of the introduction of the '2+3+2' formula which has coordinated the opening of the labour markets of the old Member States and again through the wording of the Treaty. Namely, Article 48 empowers the European Parliament and the Council to take steps not only in order to secure the aggregation of all periods of works under the laws of different countries used to calculate benefits, but also introduces a so-called 'emergency break' mechanism. The latter means that the Treaty gives veto power to any Member State which considers a draft legislative act to affect "important aspects of its social security system, including its scope, cost or financial structure, or would affect the financial balance of that system".[60] In this case the legislative process will be suspended and negotiations are going to be passed to the European Council level.

- 117/118 -

4. Data Description

In the light of the theory one must admit that stay or go decisions of individuals are shaped by many factors. Accordingly, one must take into account a mix of economic and other social and psychological push, pull and stay factors which are going to determine whether one migrates.[61] However, bearing in mind that it is unrealistic to reduce potential migrants to solely wealth-maximiser homo oeconomicus (in that case a huge mass of people would migrate to the northern and western Member States) one must also admit that the comparison of macroeconomic data is indispensable. Nevertheless, this does not mean that one could diminish the importance of the non-economic motives such as the decisions of family members, pensioners and so on but ceteris paribus the weight of the measurable salient economic motives might be extremely relevant in shaping the attitudes towards migration.

Taking into account the different push and pull factors one might distinguish between the demand and supply side of migration.[62] On the one hand, the demand side consists of the openness of the receiving country. In other terms, one might expect that if the pull factors are not strong enough there will be no or at least less migration.[63] On the other hand, the supply side of migration needs to be analyzed as well which consists of the circumstances which push people to move. The more factors argue next to the leaving (such as no job opportunities, discomfort in a specific country and so on), the bigger the probability of migration.

The core relevance of the financial crises consists in the fact that it might influence both sides: people might migrate from a country where they lose their job and do not see any positive perspective. And people might not choose to go to a particular place where there is no chance to find a secure living. In the European context this economic phenomena has turned out to be extremely relevant after 2007 as many countries have suffered from different kind of economic crises. In this context it is enough to think about the many IMF and EU loans provided for the Member States and their financial systems and the many new proactive policy tools which have entered into force in order to prevent the potential future crises.[64] Therefore, in order to assess the effect of the financial crises, this analysis departs from the enlargement of the European Union which has antedated the emergence of the economic crises and examines the data till 2013. In order to assess whether a Member State was smote by any kind of

- 118/119 -

crises, this study refers to the IMF Systemic Banking Crises Database.[65] According to the paper of Laeven and Valencia eleven Member States of the European Union were affected by systemic banking crises since 2007[66] and they report six other border line cases[67] plus Switzerland. The latter country is also covered by the free movement of people according to the special treaties between Switzerland and the European Union.[68] Furthermore, Switzerland is included into this analysis also because of the political reason - the referendum - mentioned in the introduction. The dummy variable applied in order to control the crises is 0 if there were no crises in a specific year and 1 in the opposite case including the borderline cases.

Nevertheless, the amount of mobility was shaped by special policy question. Namely, the '2+3+2' formula will be taken into account so the restrictions applied by the former Member States are controlled for in the form of a dummy variable: 0 if the free movement of workers applies between two specific countries and 1 means the restrictive policy.

The data regarding the flux of migrants is taken from the Eurostat database. However, one must bear in mind the typical incompleteness of such a database. Many times the Member States have failed to report data. But even if they did so one must take into consideration the shortcomings related to illegal migration or the failure of registration and deregistration of migrants in case they return home or in case they move to a third country.

Furthermore, among the other relevant push and pull factors the unemployment rate, the size of the country, the per capita income level and the costs of living of both the sending and receiving country will be controlled for. All data have been taken either from the Eurostat database or from the World Development Indicators and country reports of the World Bank database. The size of the country is given in terms of population size which might be more accurate in the analysis of migration in contrast with the pure GDP data. Regarding the size of the country one might expect that the amount of migrants from a country might grow together with the size of the population.

The per capita income level for comparability reasons is taken in constant prices having the year of 2005 as reference base. According to the early migration theories one might expect that the development level of the country will highly influence the migration decisions of the citizens. Accordingly, a hypothesis can be generalized as the lower the per capita income level, the more people tend to leave the country. Or in another direction: the higher the per capita income level, the more people are willing to move to a specific country.

- 119/120 -

Another decision shaping factor might be the costs of living measured by the comparative price levels reported by the Eurostat. One might expect that the costs of living will play at least as a relative pull or stay away factor, so that it affects the choice among the host countries. The latter expectation can be formulated as the higher the cost of living in a particular country the less people tend to migrate to that specific place given the fact that in European context in many Member States the salaries are similarly high so the costs of living are expected to be easily comparable.

In addition, and in line with the critique of the rational cost-benefit analyser approach of migration, a subjective element will be controlled for, namely the perception of well-being of individuals in the sending countries. The latter psychological effect one might think relevant especially in the context of an economic crises as it might show whether citizens trust in a better future in their home country or they have no positive perspective which might strengthen their willingness to migrate. The latter data is taken from the World Database of Happiness reported by Veenhoven.[69]

And finally, a so-called wage rate is being controlled for which is expected to capture the level of openness or as a corollary the level of discrimination against migrants in the host countries. The rate is calculated through the numbers reported by the Eurostat database which presents separately the median income of migrants and the median income of natives in each Member State. Accordingly, the wage rate is equal to 1 if there is no difference between the median income of migrants and natives and it is below 1 if migrants earn less than the natives. The rate differences might be caused by several reasons. It is possible that the discrimination phenomena is only one interpretation from the many others as the wage differences might also be in connection with the age and qualification structure of the migrant population. However, and independently of the interpretation of the wage rate, one might expect that people use their social networks to gain information about the wage rates in the different host countries and they tend to go to that country where the wage rate is closer to 1.

Besides the above mentioned factors all other country specific differences (the so-called 'fixed' effects[70]) will be captured by a random disturbance term. The latter captures for example the role of some classical variables such as the distance which can be treated as a relative pull factor operating through both risk and cost reduction and thus influencing the choice of destination. Furthermore, the term captures the classical language and cultural variables which might be again relative pull factors influencing the choice of destination. However, one must note that the language variable might be less important in case of the highly skilled migrants.[71]

And last but not least, the so-called network effects are controlled for. In the light of the theory new migrants tend to follow their earlier fellows as this reduces their uncertainty and information costs. Therefore a time lag has to be introduced into the

- 120/121 -

model in that way so as it can capture the migration trends of the previous years. As a consequence of this lagged effect the dependent variable needs to be introduced into the model as an explanatory variable too.

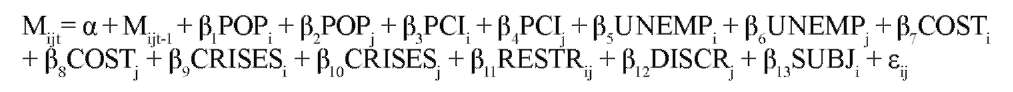

Based the above the equation used for estimating the role of economic crises in the internal mobility of the European Union looks as follows:

where Mijt accounts for the flow of migrants from country i to country j in year t while Mijt-1 denotes the flow of migrants of the previous year. POP accounts for the size of countries measured in terms of population in both the source and the host countries while PCI measures the income level in 2005 prices, UNEMP the rate of unemployment and COST captures the cost of living in both the sending and the receiving countries. CRISES is a dummy variables controlling for the occurrence of banking crises either in the source or in the host country and RESTR controls for the restrictive policy of Member State j towards the citizens of Member State i. SUBJ controls for the happiness indicator reported by Veenhoven and ε is the random disturbance term.

5. Estimation Approach and Results

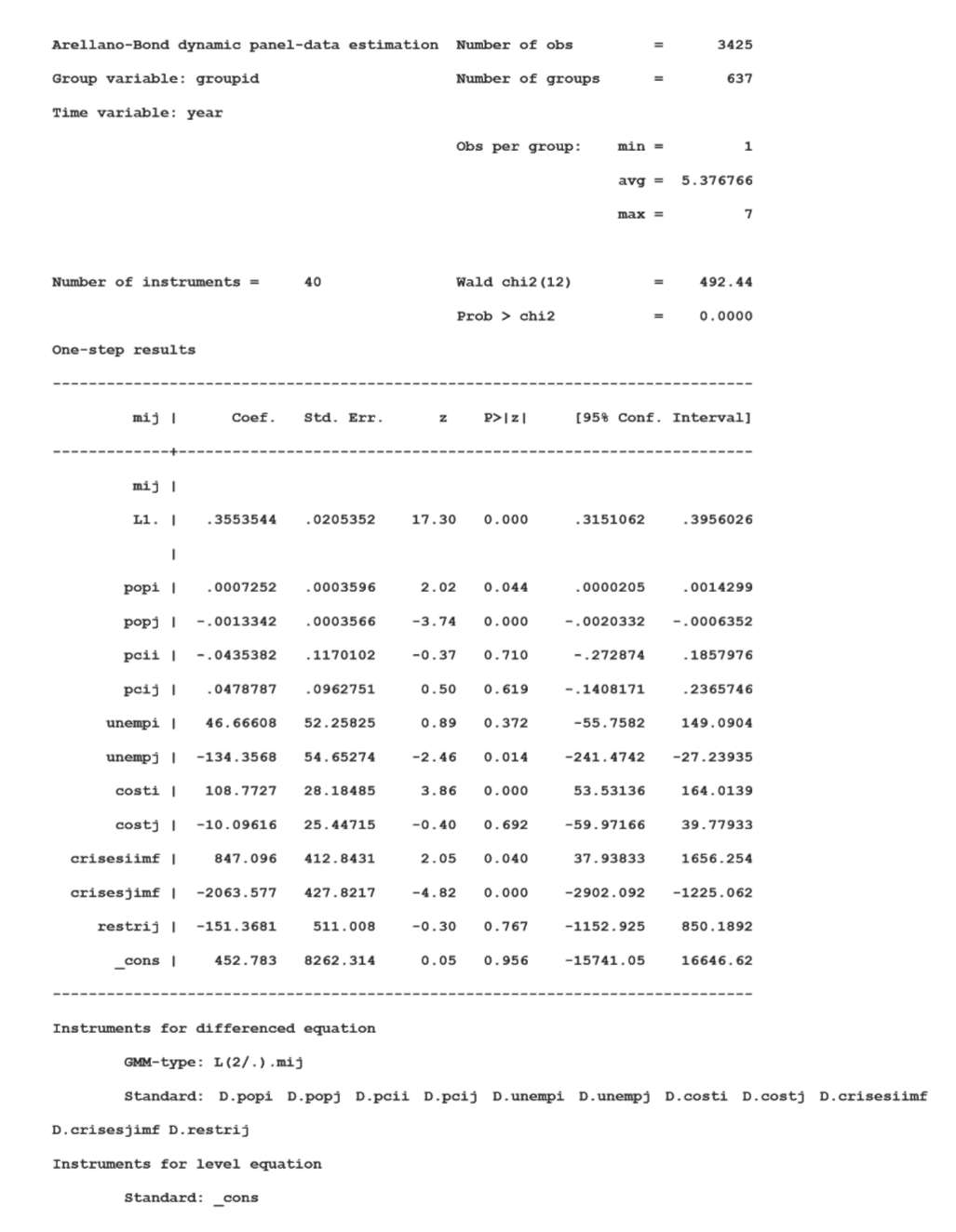

In order to test whether there is a correlation between the financial crises and migration flows among the EU Member States and Switzerland the Arellano-Bond dynamic panel data estimation seems to offer an adequate approach. This method captures for all the unobserved time invariant pair specific effects of the countries and also allows the model to contain a lagged dependent variable.[72]

However, it has to be mentioned that controlling for all above mentioned variables it proved to be unfruitful. Both the wage rate and the subjective perception of well-being and also the dummy variable controlling for the free movement of people and the '2+3+2' formula has turned out to be insignificant. In addition, the application of those variables - because of lack of data - has reduced drastically the number of observations therefore here only a narrower model is being reported which has produced more robust results with 3425 observations instead of only 2350.

Before assessing the table a couple of more comments have to be done. The dummy variable which has controlled for the '2+3+2' formula has obviously not reduced the number of observations but it has turned out to be insignificant. This might have several reasons. A possible explanation might be that the opening of newer labour markets should have the effect to stimulate the level of migration in a positive direction. However, during the crises period it seems that these flows have slow down. Therefore

- 121/122 -

in the context of the financial crises the opening of more and more labour markets might have solely a suppression effect.

Furthermore, an alternative explanation might be that the restrictive policy between two countries have already been captured as an almost time invariant pair specific effect. This explanation might also be true for the happiness index of the states as those might also have cultural roots which do not change during such a short period of time. Therefore in order to control for these variables this analysis should be repeated in the future having data on a longer time scale.

Nevertheless, there are a couple of important policy decisions which are related to the '2+3+2' formula. First of all, one old Member State (Spain) has re-introduced the restrictive labour market policy against only one another new Member State (Romania). This policy decision is a clear consequence of the economic crises which has dramatically affected Spain.

Secondly, it must be mentioned that much more old Member States have decided to open only at a later moment their labour market in the case of the Romania and Bulgaria as compared with the case of the enlargement in 2004. For this phenomena a possible explanation is offered by the researchers of the CEPS[73] who argue that the light-minded European Commission has given incentives for the old Member States to proceed so. The underlying argument says that many old Member States has taken heart to delay the opening of their market after that they could see that Austria and Germany can sustain their restrictive policy without any serious investigation. However, as a possible explanation one might call again for the role of the economic crises. The new Member States have accessed the European Union just a bit before the 'overture' of the economic crises. As a consequence, the old Member States who were highly affected by the crises have opted for a self-protective policy as the demand side of their labour markets have decreased.

- 122/123 -

- 123/124 -

Now turning to the results it can be stated that the central question of this paper has been confirmed: the crises dummy both in the sending and in the receiving country has produced significant results. On the supply side (or as a push factor) it has turned out that in case there is a crises in the source country then more people tend to migrate. On the other hand, on the demand side (or as a pull factor) the data shows that in case there is a crises in the host country then less people tend to move there.

Another relevant aspect has been confirmed by the data analysis, namely the so-called network effects. The one-year time lag has turned out to have a significant impact on the mobility trends of the next year: the more people moved to a specific country in year t-1 the more people are going to migrate there in the next year as well. This finding might also mean that in the European context the mobility of citizens is a sort of self-acting phenomena which confirms the potential fears of the national governments in the sense that governments have no tools to control the inner migration flows of the European citizens despite of any possible transitory periods.

Regarding the population of the country it has been confirmed that the bigger the size of a state the more people tend to migrate from there. The data proves also that the smaller the country the more people tend to migrate there. The latter finding might be explained by the fact that mobile people might see more perspectives and opportunities in a Member State having a smaller population.

Surprisingly the per capita income levels have produced insignificant results on both sides of the 'mobility market'. This finding can be attributed to methodological reasons. Namely, the dynamic panel data estimation captures only for the changes over time in the per capita income and not for the quite stable differences among the Member States which are handled as time invariant fixed effects. Therefore this result shows that the slight changes in the per capita income does not correlate with the migration flows which on the other hand does not mean that the per capita differences between the countries have no effect.

However, the unemployment rate in the host country seems to be a significant factor: in line with the expectation described above the higher the rate of unemployment in a specific country is the less people tend to choose it as their destination. In the meantime the rate of unemployment in the source country seems to have no significant impact on the mobility.

And finally, the cost of living shows also significant results. However, contrary to the expectations, the cost of living plays a role as a push factor and not as a stay away factor: the more expensive a country is the more people tend to leave it. Meanwhile the high cost of living in a particular host country does not affect the choice of destination. A possible explanation might be that this factor is too remote to play a serious role in the decision making process.

6. Conclusion and Outlook

The free movement of persons has started its career as a purely economically justified freedom. Later, the activism of the ECJ and the wording of the EU Treaty 'has upgraded'

- 124/125 -

this freedom through the creation of the European Citizenship which aims to guarantee a common set of political rights for all citizens of the European Union.[74]

Lately, the mobility of EU citizens has become politicized. Notwithstanding the fact that there might always exist a sort of 'populist gap'[75] between the governments and oppositions of the National Parliaments, the novelty of the current debate is that now a few governments claim to re-think the free movement of persons. In addition, to the classical vote maximizing public choice approach of politicians[76] one might interpret this debate as a sort of debate between two competing visions of Europe: the one in which the federal idea prevails and the one where the Member States try to keep the European process under control.[77] Hence, the free movement of persons can be interpreted as being at the borderline between existing as an economic institution versus as a political institution.

Nevertheless, mobility has serious economic consequences as it raises distributional issues. Sending countries might lose talent, money and people while receiving countries might fear from 'welfare shopping'.[78]

However, the mobility within Europe is far from being a mass phenomenon. In addition, it has been highly diminished by the recent economic crises, too. As this paper has presented, the crises both in the source and host country affects the migration decisions of people. On the one hand, crises at home countries push people to leave their country, while crises at potential destinations make people to stay away from that specific place.

The negative effect of the crises could not be counterweighted by the opening of more and more labour markets. In other terms, even if transaction costs are being reduced thanks to the legal provisions of the free movement of people the context of the crises might put much more burden on the migration flows.

The analysis has also revealed two other highly relevant decision shaping factors regarding the stay or go decisions of people. On the one hand, the importance of job opportunities in the potential receiving countries seems to be highly influential. The latter operates as a stay away factor and it is in close connection with the crises phenomenon. On the other hand, the network effects have turned out to be highly significant: people tend to go to those destinations to where their fellows have gone one year before. This finding also enables a potential further research topic as one might explore the specific regional hubs to where people migrate which might be a fruitful research agenda especially in the field of sociology. ■

- 125 -

JEGYZETEK

* The author is thankful to Prof. Veeramani C. (IGIDR Mumbai) for the help provided during the preparation of this paper in the frame of the European Master of Law and Economics (academic year 2013/2014). The author is also grateful to the anonymous reviewer of the Iustum Aequum Salutare for the constructive critics.

[1] Christina Boswell - Andrew Geddes: Migration and Mobility in the European Union. Basingstoke. Palgrave Macmillan, 2011. 3. This semantic differentiation can also be traced in the wording of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union. The classical migration has become an EU competence through the creation of the Justice and Home Affairs pillar in 1992. Today it can be found under Part III Title V (Area of Freedom, Security and Justice) while the internal mobility belongs to Title IV (Free Movement of Persons, Sevices and Capital).

[2] On the relevance of interregional migration see: Philip Rees - John Stillwell - Andrew Convey -Marek Kupiszewski (eds.): Population Migration in the European Union. Chichester. J.Wiley & Sons, 1996.

[3] The study excludes Croatia from its sphere of analysis as Croatia was not a Member State of the EU before and during the financial crises. However, it must be mentioned the for the first phase until 30 June 2015, the following countries apply restrictions vis-á-vis the workers of Croatia: Austria, Belgium, Cyprus, France, Germany, Greece, Italy, Luxembourg, Malta, Netherlands, Spain, Slovenia and the United Kingdom. See at: Croatia. http://ec.europa.eu/social/main.jsp?catId=1067&langId=en

[4] Tough new migrant benefit rules come into force tomorrow (press release). https://www.gov.uk/government/news/tough-new-migrant-benefit-rules-come-into-force-tomorrow

[5] Germany to revise EU migrant benefits to stop abuses. http://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-26764283

[6] Switzerland takes part of the European Free Trade Association (EFTA) along with Iceland, Lichtenstein and Norway. All EFTA countries take part of the internal market created by the EU either through the Agreement on a European Economic Area (EEA) or through bilateral agreements such as Switzerland.

[7] John Lichfield: Switzerland votes to limit the number of EU migrants. http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/europe/switzerland-votes-to-limit-numbers-of-eu-migrants-9117579.html

[8] Örn B. Bodvarsson - Hendrik Van den Berg: The Economics of Immigration. New York-Heidelberg, Springer, 2009.

[9] Zai Lang: The Sociology of Migration. http://www.uk.sagepub.com/leonguerrero4e/study/materials/reference/05434_socmig.pdf

[10] BODVARSSON-VAN DEN BERG op.cit. 75.

[11] Ibid. 27.

[12] Maria Kelo - Bernd Wächter: Brain drain and gain drain. Migration in the European Union after enlargement. The Hague, Netherlands Organisation for International Cooperation in Higher Education & Academic Cooperation Association, 2004. 24.

[13] Bodvarsson-Van den Berg op.cit. 79-106.

[14] Herbert Brücker et al.: Labour mobility within the EU in the context of enlargement and the functioning of the transitional arrangements. Final Report. Available at: http://www.iab.de/en/forschung-und-beratung/projekte/labour-mobility.aspx 91-92.

[15] Bodvarsson-Van den Berg op.cit. 107-219.

[16] The question of brain waste relates to the above mentioned sub-questions one and two. It covers the underemlpoyment of people compared with their capacities which might disincentivise some potential migrants and thus might lead to self-selection.

[17] Adam Smith: An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nation. Available at: http://www.econlib.org/library/Smith/smWN3.html#B.I, Ch.8, Of the Wages of Labour Point I.8.30.

[18] Bodvarsson-Van den Berg op.cit. 30.

[19] Ernst Georg Ravenstein: The laws of migration. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, 52/1889. 241305.

[20] John R. Harris - Michael P. Todaro: Migration, unemployment and development: a two-sector analysis. American Economic Review, 60/1970. 126-142.

[21] Larry A. Sjaastad: The costs and returns of human migration. Journal of Political Economy, 70/1962. 80-93.

[22] Bodvarsson-Van den Berg op.cit.22-26.

[23] Ibid. 52-53..

[24] Robert P. Inman - Daniel L. Rubinfeld: Federalism. http://encyclo.findlaw.com/9700book.pdf 669-676.

[25] Bodvarsson-Van den Berg op.cit.38.

[26] Boswell-Geddes op.cit. 193.

[27] Douglas S. Massey - Joaquin Arango - Graeme Hugo - Ali Kouaouci - Adela Pellegrino - J. Edward Taylor: Theories of International Migration: A Review and Appraisal. Population and Development Review, 3/1993. 431-466.

[28] Bodvarsson-Van den Berg op.cit.38.

[29] John Salt: Economic developments within the EU: the role of population movements. In: Dan Corry (ed.): Economics and European Union Migration Policy. London, Institute for Public Policy Research, 1996. 77.

[30] Ibid. 7.

[31] Alejandro Portes - Julia Sensenbrenner: Embeddedness and Immigration: Notes on the Social Determinants of Economic Action. American Journal of Sociology, 6/1993. 1320-1350.

[32] Rees et al. op. cit. 315.

[33] However, this does not mean the all barriers especially de facto barriers have been removed. Lists of the different difficulties can be found in the Citizenship Reports issued by the European Commission which formulates action plans in order to handle these further obstacles. See for example: Report from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions. EU Citizenship Report 2013. EU citizens: your rights, your future. COM(2013) 269 final. Available at: http://ec.europa.eu/justice/citizen/files/com_2013_269_en.pdf

[34] Peter A. Fischer - Thomas straubhaar: Is Migration into EU-countries demand based? In: Corry (ed.) op. cit. 16-17.

[35] Bodvarsson-Van den Berg op.cit.71.

[36] Ibid. 63.

[37] Brücker op.cit.

[38] Herber Brücker - Thomas Eger: The law and economics of the free movement persons in the European Union. In: Thomas Eger - Hans-Bernd Schäfer (eds): Research Handbook on the Economics of European Union Law. Cheltenham, Edward Elgar, 2012. 146-179.

[39] George J. Borjas: Self-selection and the earnings of immigrants. American Economic Review, 4/1987. 531-553.

[40] Harvey Nash - Center for Economics and Business Research: Impact of EU Labour on the UK. Available at: http://www.cebr.com/reports/migration-benefits-to-the-uk/

[41] Brücker-Eger op.cit. 147.

[42] Article 45, paragraph 1. TFEU.

[43] Article 45, paragrapgh 3. TFEU.

[44] In the Gebhard case the ECJ has developed the four conditions of the test which it will apply to assess the limitations of fundamental freedoms: "national measures liable to hinder or make less attractive the exercise of fundamental freedoms guaranteed by the Treaty must fulfill four conditions: they must be applied in a non-discriminatory manner; they must be justified by imperative requirements in the general interest; they must be suitable for securing the attainment of the objective which they pursue; and they must not go beyond what is necessary in order to attain it" C-55/94 Reinhard Gebhard v. Consiglio dell'Ordine degli Avvocati e Procuratori di Milano [1995] ECR I-4165 point no 37.

[45] The so-called 'mandatory requirements' have been introduced by the ECJ in the Cassis de Dijon case where the Court has mentioned as examples the effectiveness of fiscal supervision, the protection of public health, the fairness of commercial transactions and the defence of the consumer. See at: C-120/78 Rewe-Zentral (Cassis de Dijon) [1979] ECR 649. Later, the list has been broadened for instance with the aim of protection of the environment (C-302/86 Commission v Denmark [1988] ECR 460.), road safety (C-54/05 Commission v Finland [2007] ECR I-2473), the maintenance of press diversity (C-368/95 Familiapress [1997] ECR I-3689), the financial balance of the social security system (C-120/95 Decker [1998] ECR I-1831) and so on.

[46] C-224/98 D'Hoop [2002] ECR I-6191.

[47] C-109/04 Kranemann v Land Nordrhein-Westfalen [2005] ECR I-2421, C-520/04 Turpeinen [2006] ECR I-10685.

[48] C-186/87 Cowan v Trésor public [1989] ECR 195.

[49] C-184/99 Grzelczyk v Centre Public d'Aide Sociale d'Ottignies-Louvain-la-Neuve (CPAS) [2001] ECR I-6193.

[50] Article 20 TFEU.

[51] C-85/96 Martinez Sala v Freistaat Bayern [1998] ECR 2691, C-413/99 Baumbast and R v Secretary of State for the Home Department [2002] ECR I-7091 and C-456/02 Trojani v Centre public d'aide sociale de Bruxelles (CPAS) [2004] ECR I-7573.

[52] R. P. Inman - D. L. Rubinfeld: Federalism. http://encyclo.findlaw.com/9700book.pdf 669-676.

[53] Directive 2004/38/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 29 April 2004 on the right of citizens of the Union and their family members to move and reside freely within the territory of the Member States amending Regulation (EEC) No 1612/68 and repealing Directives 64/221/EEC, 68/360/ EEC, 72/194/EEC, 73/148/EEC, 75/34/EEC, 75/35/EEC, 90/364/EEC, 90/365/EEC and 93/96/EEC. Official Journal of the European Union, L 158, 77-123.

[54] Regulation (EC) No 883/2004 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 29 April 2004 on the coordination of social security systems. Official Journal of the European Union, L 200, 1-49.

[55] Article 53, paragraph 1. TFEU.

[56] A similar empowering rule can be found under Article 50, paragraph 2 which aims to reduce the transaction costs of the right of establishment. Furthermore, similarly can be assessed Article 53 relating to the mutual recognition of diplomas and qualifications.

[57] Article 46 TFEU.

[58] For example the utility loss from abandoning social contracts and the necessary investments to create new ones, time, effort, linguistical differences, recognition of qualifications and so on.

[59] Brücker-Eger op.cit.

[60] Article 48. TFEU.

[61] Fischer-Straubhaar op. cit. 13.

[62] At this point of the analysis the so-called 'stay' factors as seperate cathegory of determining elements are released. The reason for this is that many of the potencial stay factors are not quantifiable, however, some of them can be interpreted as negative push factors. E.g. the low rate of unemployment in the original country can be seen as a negative push factor as well. (Similarly, the high rate of unemployment in a potential destination country can be evaluated as a negative pull factor.)

[63] Dan Corry: Introduction. In: Corry (ed.) i. m. 3.

[64] Paul P. Craig: The Stability, Coordination and Governance Treaty: Principle, Politics and Pragmatism. European Law Review, 3/2012. 231-248. Available at: http://ssrn.com/abstract=2115538

[65] Luc Laeven - Fabian Valencia: Systemic Banking Crises Database: An Update. IMF Working Paper, No. 12/163, June 2012. Available at: https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/cat/longres.aspx?sk=26015.0

[66] Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Latvia, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Spain and the United Kingdom.

[67] France, Hungary, Italy, Portugal, Slovenia and Sweden.

[68] Boswell-Geddes op. cit. 183. See also: Agreement between the European Community and its Member States, of the one part, and the Swiss Confederation, of the other, on the free movement of persons. Official Journal, L 114, 30/04/2002, 6-72.

[69] Ruut Veenhoven: Happiness in Nations. World Database of Happiness, Erasmus University Rotterdam, The Netherlands. Available at: http://worlddatabaseofhappiness.eur.nl/hap_nat/nat_fp.php?mode=1

[70] Stephen Bond et al.: GMM Estimation of Empirical Growth Models. Available at: http://economics.ouls.ox.ac.uk/14464/1/bht10.pdf 3.

[71] Rees et al. op. cit. 65.

[72] Elitza Mileva: Using Arellano-Bond Dynamic Panel GMM Estimators in Stata. Fordham University, 2007. Available at: http://www.fordham.edu/economics/mcleod/Elitz-usingArellano%E2%80%93BondGMMEstimators.pdf 1-3.

[73] Elspeth Guild - Sergio Carrera: Labour Migration and Unemployment. What can we learn from EU rules on the free movement of workers? CEPS, February 2012, 8-10. Available at: http://www.ceps.be/ system/files/book/2012/02/Labour%20Migration%20&%20Unemployment%20-%20rev.pdf

[74] Article 20-25 TFEU.

[75] Boswell-Geddes op.cit. 190.

[76] Dennis C. Mueller: Public Choice III. New York Cambridge University Press, , 2003. See at: Chapter 11, 12, 15.

[77] The European Parliament and the European Council can be viewed as the institutional represantatives of the two visions. For a salient example see the election process of the new President of the European Commission.

[78] For the moral hazard issues see: Ian Preston: The Effect of Immigration on Public Finances. Center for research and Analysis of Migration. Discussion Paper Series, 23/2013. Available at: http://www.cream-migration.org/publ_uploads/CDP_23_13.pdf 9-12.

Lábjegyzetek:

[1] The author is law clerk (Constitutional Court).