Richard Soyer[1]: The Right to a Fair Trial The European Multilevel Approach to Criminal Justice in Austria (MJSZ, 2019., 2. Különszám, 2/2. szám, 385-394. o.)

The following article focuses on the fact that criminal justice governance in Austria is to be seen as a multilevel system which cannot be considered as a purely domestic issue. The international aspects of this system go far beyond the significant number of international or hybrid criminal tribunals or courts, which have been established for bringing justice to those who committed war crimes or crimes against humanity. Rather, I will address this topic regarding the daily criminal practice in Austria, focusing the inter- and supranational courts in Europe, which are guaranteeing a high level of human rights. Namely these are the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg as an instrument of the Council of Europe-system and the Court of Justice of the European Union in Luxembourg.

In the third part of this article I will present two case studies, in which I was acting as an Austrian criminal defense lawyer. These cases are still remarkable as they shaped the recent Austrian regulations on criminal procedure in a significant way. The contribution will end with an insight into one specific aspect of the right to a fair trial regarding our criminal procedure law.

1. The European Multilevel Approach to Criminal Justice in Austria

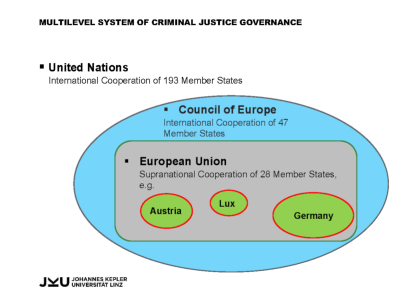

I will start with giving just an overview on the human rights protection and the multilevel system of criminal justice governance in Austria. This system can be described as follows:

There is the global system of the United Nations (UN), having now 193 Member States; offering both human rights instruments as well as treaties focusing on combating and preventing transnational or other forms of serious crimes. Other treaties are strengthening the mutual legal assistance between state parties of the

- 385/386 -

UN system.

The next level is the Council of Europe (CoE) as a regional system of international cooperation of now 47 Member States: At this level, treaties are established for combating serious and transnational crimes and mutual legal assistance too.

Furthermore, at this level the protection of human rights is addressed on the one hand by the European Convention of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms (ECHR) and the respective court in Strasbourg.

On the other hand, this level is providing guidelines for various aspects of the criminal justice system such as the European Prison Rules. Additionally, there are monitoring mechanism for the compliance of national criminal justice systems with specific requirements.

The next level is the European Union (EU) as a special regime in international law, being a supranational cooperation of 28 Member States at the moment: The EU law does not only address its Member States, but also directly the citizens of these states.

Let me recall in this context: The EU was founded as a treaty-based economic union, based on the free-movement of persons, goods, services, labour and capital. As a result, the abolition of internal border control demanded stronger cooperation in justice and home affairs. But stronger and broader integration demands also the guarantee of human rights.

The last level is the domestic criminal justice system, for instance in Austria. I would like to point out, that human rights standards are very different throughout the Member States. In Germany, as an example, the standards are - often -higher than the European ones. Not so in Austria.

Table 1: The Multilevel System of Criminal Justice Governance

- 386/387 -

2. The multilevel human rights regime and jurisdiction in Austria

Let me first address and point out some of the most relevant, mainly substantive laws on these levels:

United Nations: e.g. the Universal Declaration of Human Rights; the International Covenants for Political and Civil Rights as well as the UN Convention against Torture.

Council of Europe: the European Convention on Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms (ECHR); the case law of the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg (ECtHR).

European Union: The human rights case law of the European Court of Justice (ECJ); the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights. On the EU level exists an advanced system of police and judicial cooperation in criminal matters - enforceable; with primacy over national law; sometimes even direct applicable law. Austria: Let me underline at this point that the ECHR is for more than 50 years part of the Austrian Constitutional Law.

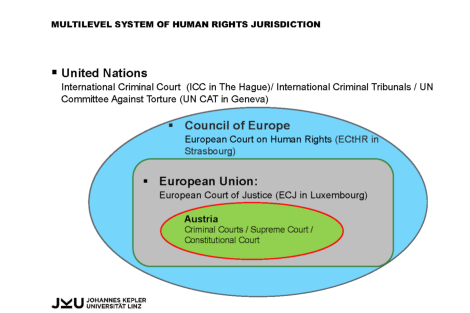

What is the structure of the human rights jurisdiction in this regard?

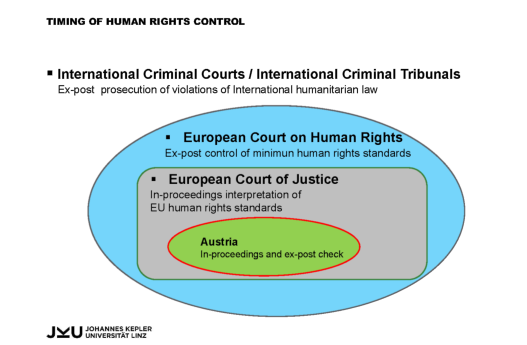

International criminal courts and tribunals are established with the support of the United Nations system, mostly as a fallback institution to guarantee the prosecution of most serious offences as recognized by the Nuremberg principles. Beside that there are in general no human rights courts existing at the UN level. Yet, the UN Committee against Torture in Geneva as a body with a special jurisdiction about torture issues needs to be mentioned - a case study with focus on this matter will follow below.

Next to the UN level, the CoE provides for an elaborated regional judicial system protecting minimum standards of human rights, accessible by individual complaints to the ECtHR. While the EU related ECJ in Luxemburg can be asked to interpret the requirements of EU fundamental rights within ongoing national proceedings by using a special preliminary rulings procedure, the ECtHR in Strasbourg may be applied only after a violation already happened. I will discuss a second case study later, in regard of the Strasbourg Court.

The last level are national courts, like in Austria, having tasks to fulfill regarding the criminal justice governance. The "daily business" of a criminal defense lawyer is taking place in front of these courts.

- 387/388 -

Table 2: The Multilevel System of Human Rights Jurisdiction

3. Two case studies

The case of Mr. Cani Halimi during the 1990ies was one of the biggest drug offences Austria had ever faced - Mr. Hal/mi was alleged for organizing and leading heroin imports and transits of hundreds of kilos pure heroin. When he was interviewed by the police immediately after being arrested, some unlawful interrogation methods seemed to be applied by the police - but Mr. Halimi did not confess anything. However, a severe injury on one of his eyes remained forever and the law enforcement agencies did not give an appropriate explanation for this injury. After long court trials, although not pleading guilty on any allegation, Mr. Halimi was convicted and sentenced to 14 years of imprisonment.

Before continuing with the case study, I have to draw the attention to the UN Convention against Torture (UN CAT). Austria ratified this convention in the 1980ies. It was common opinion among academics that this convention is self-executing. When I was taking over the representation of Mr. Halimi at the end of the public hearing in first instance, I quickly tried to build up a defense using two provisions of this treaty - Art 12 UN CAT, providing a right to an impartial investigation as soon as possible, and Art 15 UN CAT, providing an exclusionary rule for confession by torture. Unsuccessfully, the court of first instance as well as the Supreme Court being the appellate instance rejected my plea of nullity against the conviction.

- 388/389 -

Afterwards I lodged a complaint to the UN committee against Torture in Geneva, Switzerland.

Let me now cut a long story short: As Mr. Halimi never confessed anything, a breach of Art 15 UN CAT could not be identified by the UN Committee in its decision[1] - as the Austrian Supreme Court did before. But Austria was convicted in Geneva for the omission to promptly execute an impartial investigation of the torture allegation.

The outcome of this long procedure was more or less poor for Mr. Halimi himself. But it has to be noted: Unlawful interrogation practices by the police generally changed after the Halimi case. Since prompt investigations in cases of alleged torture regularly took place in Austria from now on, I may guess that police practice is significantly improving since the year 2000. And concerning Art 15 UN CAT, since the year 2008 there is a special regulation in the Austrian Code of Criminal Procedure (§ 166 CCP[2]) which states an exclusionary rule for confessions forced by torture.[3] Hence, I still can see an outstanding value of the UN CAT after the Halimi case for the daily work of criminal defense in Austria.

The timing of human rights control is addressed and pointed out in the table below. At the ECtHR in Strasbourg an individual claimant may receive ex post control of minimum human rights standards violations. Let me underline that this was exactly the aim that I was trying to realise in the Kremzow case.

- 389/390 -

Table 3: The timing of Human Rights Control

ECtHR convictions can be characterized as an internationally perceived reminder to follow common minimum standards - but what does this really mean?

I will try to contribute to a better understanding of this question by explaining the Kremzow case, which I personally experienced as an Austrian human rights defense lawyer. This case will point out the value of the ECHR as a legally binding international human rights treaty from 1950 - with effective minimum standards.

The right to an individual complaint against state actions to the ECtHR is empowered with two central regulations I shall address in this context.

"Article 46 para. 1 Binding force and execution of judgments

The High Contracting Parties undertake to abide by the final judgment of the Court in any case to which they are parties."

"Article 41 Just satisfaction

If the Court finds that there has been a violaton of the Convention or the Protocols thereto, and if the internal law of the High Contracting Party concerned allows only partial reparation to be made, the Court shall, if necessary, afford just satisfaction to the injured party."

Before going in medias res, I may outline the cornerstones of the case: Mr. Kremzow was a judge in Austria, confronted with the suspicion of murdering a lawyer. In a jury trial in first instance he was convicted to 20 years of imprisonment. The prosecution as well as the defense side launched remedies

- 390/391 -

against the verdict to the Supreme Court. Mr. Kremzow was not granted to appear personally at the public hearing before the Supreme Court although he explicitly requested it. Following the appeal of the prosecution, the Supreme Court imposed a lifetime sentence.

Mr. Kremzow complained before the ECtHR, claiming that the Supreme Court did not allow him to participate at the public Supreme Court hearing. Because of that he was arguing that he could not defend himself and therefore was sentenced to lifetime imprisonment.

Mr. Kremzow won the ECtHR case[4] and Austria was convicted for a breach of Art 6 § 1 c) ECHR[5] (Right to defend himself). From the perspective of Mr. Kremzow this was not sufficient at all, as he had to continue serving his lifetime sentence. Such decisions of an international human rights court as the ECtHR should be more than a sort of a wall paper in the cell of a prisoner, they must have a real impact at all. Therefore Mr. Kremzow sued the Republic of Austria at civil courts, requesting effective compensation for this kind of unlawful imprisonment.

At this moment I started the representation of Mr. Kremzow. Surprisingly, in contrast to his common practice, the Supreme Court in civil matters decided to debate this case in a public hearing. During this public hearing, I argued that continuing the execution of the life sentence would be a breach of EU law principles. The main argument was: Not only the legislation of CoE member states, but also national courts are obliged to implement Strasbourg decisions to the benefit of the concerned citizen as far as possible. Following this motion, the Supreme Court decided to request a preliminary ruling of the ECJ in Luxembourg.[6] The Luxemburg court later ruled that it did not have jurisdiction in this special matter.[7]

Although the case was lost, the Austrian legislator was provoked to implement a new regulation: § 363a Austrian Code on Criminal Procedure (CCP).[8] Since then a Strasbourg decision is a reason for renewing the related national criminal procedure.

- 391/392 -

4. The Right to a Fair Trial in Austria

Art. 6 ECHR can be considered to be the fundamental norm for the right to a fair trial in Austria. Unlike in some other EU Member States, it has even constitutional character in the Austrian legal order. The term "fair trial" is also explicitly used in the Austrian CCP. Hence, the regulations in the CCP needs to be interpreted in the light of Art. 6 ECHR.[9]

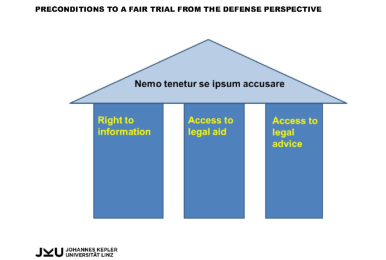

In general, the principle requires an equality of arms, including the right of the defendant to be present in court, the right of equal access to documents and records, the possibility of interrogating witnesses and experts, and the right to oppose the arguments advanced by the prosecution. And last but not least, the defendant has the right to effective legal representation. In this context, I may only focus this last aspect of the fair trial principle.

From a defense perspective there are three fundamental pillars as a precondition of the right to a fair trial: (i) The right to information (about the fair trial rights and about the allegation). (ii) The right to access to legal aid (if the means and merits test requires so). (iii) The access to legal advice (either for self-defense or defense by a lawyer of its own choice).

And as a cover for protection of these pillars, there is the effective right of the suspect not to be forced to incriminate him- or herself: "Nemo tenetur se ipsum accusare"

Table 4: Preconditions to a Fair Trial from the defense perspective

- 392/393 -

Before focusing on the access to legal advice in the case law of the Strasbourg Court as just one of these pillars, it should be clear, what the court recalled in the famous Artico case already 40 years ago:[10]

"The Court recalls that the Convention is intended to guarantee not rights that are theoretical or illusory but rights that are practical and effective."

Access to legal advice is also a question of time: One should keep in mind that the path of the proceedings will be laid down already at pre-trial stage, frequently even during the first interrogation of a suspect. Hence, the Strasbourg Court delivered a leading decision in the Salduz case in 2008:[11]

"National laws may attach consequences to the attitude of an accused at the initial stages of police interrogation which are decisive for the prospects of the defense in any subsequent criminal proceedings. In such circumstances, Article 6 will normally require that the accused be allowed to benefit from the assistance of a lawyer already at the initial stages of police interrogation."

However, Salduz does not provide a clear statement of the right to have the lawyer present during the interrogation. It refers to access to the lawyer before the interrogation takes place. Yet, from the Demirkaya case[12] in the follow up of Salduz it can be concluded that the right to access also includes the presence of a lawyer during the first police interrogation.[13]

Beside the Salduz case referring to access to the lawyer before an interrogation takes place,

the second leading decision is the one of Dayanan vs Turkey where the court pointed out:[14]

"In accordance with the generaly recognised international norms, which the Court accepts and which form the framework for its case-law, an accused person is entitled, as soon as he or she is taken into custody, to be assisted by a lawyer, and not only while being questioned [...]."

Both decisions, meanwhile, were transposed into EU secondary legislation on minimum standards for suspects rights in criminal proceedings and into the Austrian CCP.

And, consequently to the Salduz approach, the ECtHR pointed out that there are also minimum requirements for a valid waiver of the right to access to legal advice. It has been the Pishchalnikov case where the Court stated:[15]

"Having been denied legal assistance, the applicant was unable to make the correct assessment of the consequences his decision to confess would have on the outcome of the criminal case. [....] In the absence of assistance by counsel who could have provided legal advice and technical skills, the applicant could not make

- 393/394 -

full and knowledgeabe use of his rights afforded by the criminal-procedural law."

There are many cases, where Strasbourg decisions play an important role. It would overload the scope of this article to present more. So, let me sum up: (i) The right to a fair trial was and is a predominant cornerstone in the Austrian criminal justice system. (ii) This principle - applicable in the daily domestic practice - enables the defense to challenge criminal charges effectively. (iii) As an Austrian academic and as a defense lawyer, I do not want to miss the multilevel-impact of international and European conventions and courts in human rights matters. I presume that Hungary is in this regard not so different from Austria. ■

NOTES

[1] Halimi-Nedzibi v. Austria, Comm 8/1991, UN Doc CAT/C/8/D/8/1991, 18/11/1993; http://www.worldcourts.com/cat/eng/decisions/1993.11.18_Qani_Halimi-Nedzibi_v_Austria.htm (06.05.2019.)

[2] «Inadmissible Evidence § 166. CCP

(1) Answers given by the accused as well as answers of witnesses and co-accused may not be used to the disadvantage of the accused - except against persons who are accused of breaking the law in the context of questioning - if:

1. They came about under torture (Art. 7 International Covenant of Civil and Political Rights, BGBl. No. 591/1978, and Art. 1 para. 1 and Art. 15 of the Convention against torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment, BGBl. No. 492/1987), or

2. They were otherwise obtained by illegally influencing a person's freedom of decision-making, or the freedom to use his or her will, or by using inadmissible methods of questioning if these violate fundamental principles of procedure and if exclusion of these answers is vital to repair this violation.

(2) Answers that came about or were obtained in the manner set out in para. 1 are void."

[3] For a more detailed view on the legal situation before implementing § 166 CCP see Richard Soyer, (K)Ein Verwertungsverbot gemäß Art 15 der UNO-Konvention gegen die Folter, AnwBl 1992. 349.

[4] ECtHR, Kremzow v. Austria, 12350/86, 21/9/1993.

[5] See footnote 5.

[6] For the text of the oral observations on behalf of Mr. Kremzow at the public hearing before the ECJ see Richard Soyer: Cives europaei sumus! - Ein Beitrag gegen die Indolenz gegenüber Urteilen internationaler Menschenrechtsinstanzen, Juridikum, 1997/2. 16.

[7] ECJ, Kremzow v. Austria, C-299/95, 29/5/1997.

[8] "Renewal of criminal proceedings § 363a. CCP:

(1) If a judgment by the European Court of Human Rights determines that a decision or order by a criminal court violates the Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms, BGBl. No. 210/1958, or one of ist Additional Protocols, upon request those proceedings have to be renewed insofar as it cannot be ruled out that this violation may have a negative impact on the content of the decision of a criminal court for the person concerned.

(2) In all cases, applications to renew proceedings are decided by the Supreme Court of Austria. [...]."

[9] Art 6 ECHR states: "1. In the determination of [...] any criminal charge against him, everyone is entitled to a fair and public hearing within a reasonable time by an independent and impartial tribunal established by law. [...] 3. Everyone charged with a criminal offence has the following minimum rights: [...] (c) to defend himself in person or through legal assistance of his own choosing or [...].

[10] ECtHR, Attico v. Italy 13/05/1980, series A No. 37 § 33.

[11] ECtHR (GC), Salduz v. Turkey, 27/11/2008, 36391/02 § 52.

[12] ECtHR, Demirkaya v. Turkey 13721/02, 13/10/09.

[13] It shall not be missed that in 2016 in Ibrahim and others v. UK, 13/09/2016, 5041/08, 50571/08, 50573/08 and 40351/09, the ECHR (GC) did not incriminate temporary limitations to the right in terrorism cases.

[14] ECtHR, Dayanan v. Turkey, 13/09/2009, 7377/03, § 32.

[15] ECtHR, Pishchalnikov v. Russia, 24/09/2009, 7025/04, § 85.

Lábjegyzetek:

[1] The Author is Professor of Criminal Law, Institute of Criminal Law and Criminal Justice, Johannes Kepler University, Linz (Austria); lawyer, Law Offices Soyer Kier Stuefer, Vienna (Austria). The paper includes a presentation given by the author at KAZGUU University in Astana (Nur-Sultan), Kazakhstan, when he was appointed on February 19, 2019, as Honorary Professor.