Boaz Oyoo Were[1]: Judicial Independence as a Contemporary Challenge - Perspectives from Kenya (FORVM, 2018/1., 365-399. o.)

Abstract

This paper examines the concept of judicial independence in Kenya with a view to providing a deeper understanding of the challenges that work against its practical aspects. It uses a generalizable analytical framework to illuminate the relationship between judicial independence and specified essential factors normally considered as critical to strengthening the judicial independence in a democratic society. Descriptive method has been used to relate data to theory and to provide a coherent explanation on impediments to judicial independence in Kenya. The empirical analysis that draw on two datasets-the Afrobarometer and The CIRI Human Rights, is provided to augment theoretical explanations. These datasets directly relate to Kenya, hence their usefulness. This paper provides a detailed description of perceived challenges to judicial independence in Kenya and makes summaries on reasons why such challenges subsist.

1. Introduction

Building and maintaining a strong culture of judicial independence is of great importance to a democratic society. Indeed, judicial independence has been seen as fundamental, not only in terms of the rule of law, constitutionality and human rights perspectives, but also in regard to globalization, free and efficient economic activity.[1] Scholars of judicial independence submit that it is not only one of the basic values which lie at the core foundation of the administration of Justice, but also very fundamental in creating an efficient and reliable judiciary (i.e Shetreet and Forsyth 2012). Judicial independence has also been perceived as an imperative element of 'fair trial' (Bado 2014). Further, judicial independence is also seen, not as an end to itself, but as a means to achieving ends. If judges are independent, they are essentially protected from undue influences from all possible agents

- 365/366 -

in society that could undermine their impartiality. Consequently, judges are more likely to uphold the rule of law, preserve the separation of powers, promote the due process of law (Geyh 2008) and provide fair adjudication as long as their independence is guaranteed.

While the desire to have an independent judiciary is fairly important in many democratic societies, there are myriad factors (socio-political and economic) that impede this desire from being realized. Indeed, from a sociological perspective, we learn about a society better by understanding its systems and how they function, myriad conflicts that it presents, and a plethora of symbolic interactions that we experience in our day-to-day life. All these analytical frameworks are important in not only understanding legal systems but also in describing and explaining contemporary challenges that bedevil judicial systems in a democratic society.

Moreover, it is important to realize that waves of social life appear to swirl incessantly (Cotterrell 1992) around judges and magistrates as they are also human beings who experience numerous everyday encounters with creditors, debtors, landlords, tenants, families (see Cotterrell 1992), and other state actors or agents. All these are social realities, and it is particularly appropriate, therefore, to understand the work that judges and magistrates do as a 'confrontation' between justice and social realities. The common sense perception is that the intentions and motivations of judges and magistrates are more likely to be influenced by social realities. From a functionalist perspective, each aspect of society is interdependent; from symbolic interactionist perspective, people attach meanings to symbols and then they act according to their subjective interpretation of those symbols; and from conflict perspective, unequal groups of individuals usually have conflicting values and agenda. All these perspectives may help illuminate the elusive nature of judicial independence in Kenya's democracy.

The concept of judicial independence has been linked to essential aspects such as judicial reforms, judicial selection, constitutional safeguards and the war on corruption.[2] The purpose of this paper therefore is to examine the efficacy of these predictions in relation to judicial independence in Kenya. The rest of this paper is organized as follows: part 2 provides a detailed treatment of judicial independence in Kenya; part 3 focuses on the methodology; part 4 provides discussion and recommendations; and part 5 makes a conclusion.

2. Judicial Independence in Kenya

The concept of 'judicial independence' is fairly well recognized both by international resolutions and domestic laws of a modern democracy. The 'United Nations Basic Principles on the Independence of the Judiciary and the Role of Lawyers' were endorsed by the UN General Assembly in 1985 and 1990. Subsequently, the 'Bangalore Principles of Judicial Conduct' endorsed in 2003 recognizes "judicial independence as a prerequisite to the rule of law and a fundamental guarantee of a fair trial." Judges are therefore expected to uphold and exemplify judicial independence in both individual and institutional aspects. Legal scholars equate judicial independence to judicial power (Fleck 2014), while Bado (2014) opines that judicial independence is a prerequisite to fair trial.

- 366/367 -

Despite great importance in having judicial independence in a democratic society, Kenya has not taken adequate concrete steps in terms of securing and preserving judicial independence. This might be attributed to the fact that practical aspects of judicial independence have proven elusive despite myriad competing theoretical predictions. A section of scholarly literature suggests that judicial independence can be achieved through broader institutional [legal and judicial] reforms (i.e Shetreet and Forsyth 2012; Bado 2014; ICJ 2005), while another group of thinkers believes that judicial independence can be realized through a fair selection process of judges (see Bado 2014; Zoll 2012). Yet, there are those who believe that weaker ethical traditions, corruption and lack of appropriate code of conduct in the judiciary are potent factors in undermining judicial independence (Shetreet and Forsyth 2012; Ackerman 2007; Arvidson and Folkesson 2010; Chodosh 2012). Still, other scholars link judicial independence to fairness in the distribution of cases (see Bado and Szarvas 2014). But each of these propositions suffer severe difficulties in evaluating the efficacy of their predictions because of the apparent lack of systematic empirical work to scientifically test and relay concrete results on these predictions. However, analyzing these predictions with a focus on Kenya's judiciary reveals great challenges that significantly affect the institutionalization of judicial independence in Kenya.

Probably, the best starting point in understanding the nature of judicial independence in Kenya is to make reference to Kenya's Constitution and also examine related subjects of much interest: the so called judicial reforms, judicial selection and judicial corruption. In one common approach, judicial independence is conceived of as "autonomy"[3], where a judge is perceived to be independent and her decisions are free from undue influence from external forces or government (Rosenn 1987; Kornhausser 2002). However, scholars view judicial independence as a two-dimensional concept: institutional independence and decisional independence.[4]

On the one hand, institutional or relational independence is mainly concerned with the 'autonomy' and the capacity of the judiciary as a separate branch of government to resist encroachments from the political branches and thereby preserve the separation of powers.[5] For instance, Larkins (1996) views judicial independence as a scope of the judiciary's authority as an institution in its relationship to other parts of the political system and society and its legitimacy as an entity entitled to determine what is legal and what is not. On the other hand, decisional independence concerns the capacity of individual judges to decide cases without threats or intimidation that could interfere with their ability to uphold the rule of law (Geyh 2008). Similarly, Becker (1987) takes the view that judicial independence is the degree to which judges believe they can decide and do decide consistently with their own personal attitudes, values and conceptions of the judicial role in opposition to what others who have or are believed to have political and judicial power think about such matters.[6]

Judicial independence reinforces the pillars of the rule of law by ensuring that law applies to everyone, laws are enforced fairly, the justice system is fair, and laws are not

- 367/368 -

arbitrary.[7] It is a concept that some countries are likely to treat with a 'rider'. While the practical aspect of judicial independence is likely to significantly enhance the doctrine of separation of powers, the political class in many countries are less likely to be comfortable with that norm. Unless the political climate and social consensus support judicial independence, then it is a concept that will only remain fanciful, but with little efficacy. In the words of former U.S. Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O'Connor, "It is tremendously hard to create judicial Independence, and easier than most people imagine to destroy it."[8] The historical dominance of the executive branch over the judiciary in Kenya has made it difficult for the Kenya's government to respect separation of powers and create a free, fair and independent judiciary. But Kenya is party to the general rules of international law[9] and therefore, the Kenya's government has a constitutional obligation to establish, respect and preserve the democratic principle of judicial independence.

Principle 1 of the United Nations (UN) Basic Principles on the Independence of the Judiciary asserts that, "The independence of the judiciary shall be guaranteed by the State and enshrined in the Constitution or the law of the country. It is the duty of all governmental and other institutions to respect and observe the independence of the judiciary."[10] It is against this background that Kenya's judiciary is established as an independent body by the Constitution. Article 160(1) of Kenya's Constitution affirms that, "In the exercise of judicial authority, the judiciary, as constituted by Article 160, shall be subject only to this Constitution and the law and shall not be subject to the control or direction of any person or authority."[11] Apparently, in both spirit and text, Kenya's Constitution recognizes and affirms the principle of judicial independence as an important aspect in safeguarding the rule of law.

Unfortunately, however, the actual realization of 'judicial independence' seems to be a pipe dream in Kenya. Scholars observe that although there is an international convergence, especially regarding what an 'independent and an impartial court' is all about, requirement for the implementation of judicial independence remains a challenge due to different legal systems in different countries.[12] But one would argue that the practical challenges regarding the principle of judicial independence is not very much about the differences that exist in terms of legal systems, but rather has much to do with 'cultural attitude'.[13] To put it more bluntly, judicial independence should become a global culture in all legal systems and therefore the norms and standards of judicial independence should be upheld in all democracies. To give enough force and perspective to the aforementioned theoretical predictions, the sub-sections below provide analyses mainly on Institutional (legal and judicial) reforms, judicial selection, judicial corruption and code of conduct, and constitutional safeguards. The idea is to evaluate whether or not these 'essential' as-

- 368/369 -

pects of creating the culture of 'judicial independence' have been effective or incompetent in strengthening the culture of judicial independence in Kenya's judiciary.

Discussions in subsequent sub-sections use an overarching - a generalizable analytical framework known as 'ideological polarization' to provide coherent relational perspectives between judicial independence and the aforementioned theoretical predictions. This 'ideological polarization' framework advances an important, new understanding of how the enforcement of judicial independence is more often than not problematic because of 'ideological distance' between groups of individuals, hence diverging relational interests of certain specific actors in society. In so doing, each discussion undertaken under each sub-section herein provides fresh insights into understanding the challenges that pose threats to judicial independence. To be more precise, the usage of the word 'ideological' derives from the word 'ideology', which for the purposes of this paper refers to inducement, [incentive, persuasion, a belief or sets of beliefs]. The analytical framework is oversimplified to enable ease of grasp and appreciation.

Dalton (2008), Curini and Hino 2012, and Sartori (1976) have long concluded in their analyses of political parties that ideological polarization is one of the most established and discussed indicators of political party systems. This understanding can be extrapolated into the study of judicial systems. Every society is made up of fragmented and polarized groups of individuals on the basis of interests. For instance, sometimes judges want to uphold their code of ethics and apply rational and fair adjudication while political actors want to weaken existing legal norms or act with impunity to achieve selfish interests. There can never be a peaceful co-existence between the two groups of individuals in society. They hold different belief systems and thus there is an 'ideological distance' between them. Their belief systems are distance apart. Political actors may then use intimidation and influence to force judges to co-opt or give in to their [politicians'] belief system-ill-designs. That is how judicial independence gets weakened, threatened and subordinated. Detailed treatment of this analytical frame is provided in the sub-sections hereunder.

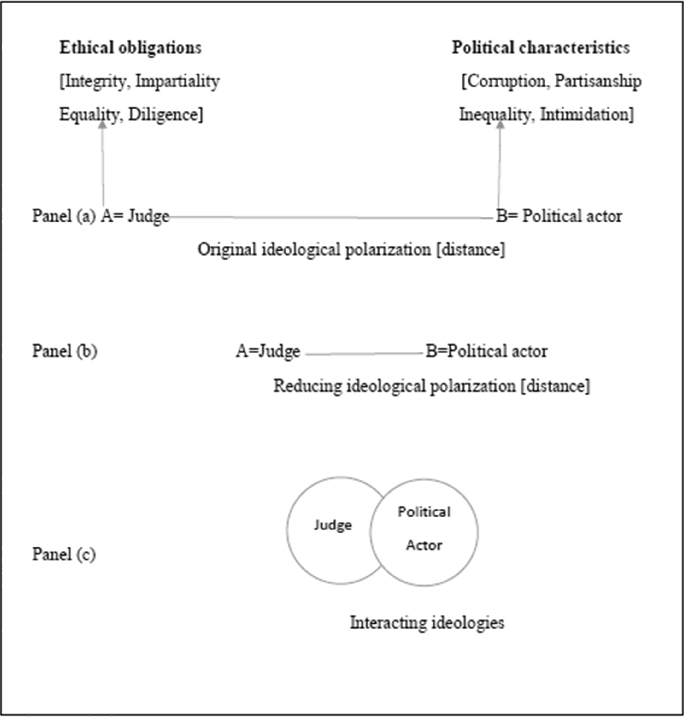

Figure 2.1 below provides an analytical model which is mainly a broad and generalizable analytical framework for purposes of appreciating challenges to judicial independence. It operates on the concepts of 'ideological polarization' and 'ideological distance'.

- 369/370 -

Fig. 2.1

Analytical Model: Generalizable analytical framework

Source: Author

The generalizable analytical framework in figure 2.1 above represents a phenomenon whereby there are potential rational actors. In other words it represents a rational 'game' between two sets of actors. In order for the game to play out, it makes the assumptions that there are a set of players, in this case: a judge and a political actor. The political actor could also be replaced by a litigant or other influential persons who want to restrain or influence justice. The other assumption is that all players are rational in the sense that each player understands any action that he or she takes would affect his expected benefit. Judges for example, are normally assumed to care about their reputation in the bench and therefore any decision they make should be seen as independent, impartial, competent and

- 370/371 -

possessing unquestionable integrity. Political actors on the other hand also care about their reelection and their actions must be geared towards instrumental gains that would enhance their bid for reelection. Politicians care more about resources, amassing wealth, and serving their own interests and some interests of their constituents. For a politician to succeed in all these, he or she cannot be fully innocent of corruption, intimidation, inequality and partisanship. The other assumption that is made is that there is a set of action for each player and the final assumption is that each player expects a set of payoffs.

The game is simplified and moves as follows: a judge cares about his reputation in the bench and wants to maintain ethical obligations [integrity, impartiality, independence, competent] of the bench. On the other hand, a political actor cares about his or her reelection and would want to create resources using all manner of tactics [corruption, intimidation, political influence]. The two actors are obviously at two distant, in fact, extreme poles of ideologies. If the judge is strictly professional and loath external influence in adjudication, he or she will resist any attempt by the political actor to narrow the gap of the ideological distance. If this gap is maintained and remains constant at its original as shown in panel (a) of figure 2.1, then the judge is more likely to uphold his decisional independence. No external influence will corrupt the decisional independence of members of the bench and a fair adjudication is therefore guaranteed. However, if the judge allows the ideological distance to reduce (panel b) to a level of ideological interaction shown in panel c of figure 2.1, then he or she is likely to indulge in corruption and impartiality and this would very likely interfere with his or her decisional independence, hence the threat to judicial independence.

The ideal scenario for justice and social order in society would be when both actors hold moral norms and share similar ideologies: integrity, impartiality, wise, and respectful. In this case, whenever the two actors' ideological distances reduces to a level of interaction (panel c), the product of that interaction is a 'social order' of justice. When there is harmony and cohesion of moral norms in society, then the moral obligation for upholding judicial independence is strengthened. Judicial independence can be said to mirror the social order of the society. But this is only possible when the society respects social norms. Durkheim, (1897/1997); Parson (1937), Merton (1942), and Dahrendorf (1958) had long laid emphasis on social norms as prerequisite condition for the establishment of social order in any society. Norms also can strongly restrain individuals from self-interests (Winter, Rauhult and Helbing 2012). According to Robert K. Merton, when moral norms are legitimized in terms of institutional values, societal norms then become moral consensus. Indeed, many of our daily activities are governed by social norms, which set the rules of how we ought to behave (Winter et al. 2012).

As classic examples of how political actors can use intimidation to influence the bench, there are three important phenomena to draw on. Firstly, in the 2017 Kenya's presidential elections in Kenya that was held on August 8, 2017, the electoral body (Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission) of Kenya declared the incumbent (Mr. Uhuru Kenyatta) to have won an election by 54 percent over his closest rival (Mr. Raila Odinga) who had obtained 45 percent. Mr. Odinga successfully launched an election dispute at the Kenya's Supreme Court and the Supreme Court nullified the presidential election terming it as "null and void" due to several irregularities and illegalities that failed to comply with the Kenya's

- 371/372 -

Constitution and the election laws[14]. After the Supreme Court verdict, President Kenyatta was angered and openly attacked the Chief justice and other judges of the Supreme Court whom he accused of deliberately nullifying his victory. The President even went ahead and termed the bench as "wakora" a Swahili word for crooks or thugs[15].

"Unajua hapo hawali nilikuwa Rais mtarajiwa, lakini sasa Maraga na watu wake wamesema hii ipotee, sasa Maraga na hao wakora wake wajue mimi ni Rais aliyekalia kiti. (As you all know, I had been declared as the president-elect, but Maraga (Chief Justice) and his people have decided that I lose it. But Maraga and his team of thugs should know that I am the sitting President)," Uhuru said at Burma Market.[16] Then the following day at State house Nairobi, President Uhuru revisited the issue and shocked the public with his vicious attack of the Supreme Court. "President Uhuru Kenyatta and his deputy William Ruto this afternoon used a nationally televised meeting to call as "stupid" the Supreme Court judges who nullified the August 8 presidential election and threatened to deal with them if Jubilee is re-elected in the fresh election ordered by the court". [17] "We shall revisit this thing. We clearly have a problem. Who even elected you? Were you? We have a problem and we must fix it,"[18] a visibly angry Uhuru declared at State House, Nairobi, where he and Ruto summoned Jubilee governors and members of the county assembly from around the country. Kenya's Citizen TV and KTN channels carried large part of the meeting live.

The Supreme Court ordered for a fresh election within 60 days based on the Constitutional provision. However, the NASA coalition headed by Mr. Raila Odinga felt that the national electoral body was being unduly influenced by the executive to bungle elections in favor of President Kenyatta. The electoral body set the fresh presidential elections on October 26 and even before this date, there were again several petitions launched in the Supreme Court to call off and postpone the elections because the electoral body had not fully complied with the constitutional requirements for conducting a fresh election. Then on the eve of October 25, which was the day the Supreme Court had scheduled to hear the pre-election petition before the October 26 fresh elections, a driver cum security agent of the Deputy Chief Justice was attacked and shot by unknown people. Then on October 25 when the Supreme Court was supposed to sit, only 2 judges out of 7 showed up. The Chief Justice who turned up with one of the judges addressed the Court and said that one judge was reportedly unwell and hospitalized and the Deputy Chief Justice was attending to her official driver who had been shot the previous evening. However, the remaining three other judges were simply unable to come[19]. This saw the Supreme Court suffer an 'artificial' quorum hitch. So the petition hearing was called off and postponed to later date, obviously after the fresh presidential election that was to take place on October 26.

Speculations were rife, however, that the judges were under threat by the executive and that is why there was a quorum hitch. The shooting of the Deputy Chief justice's driver was

- 372/373 -

also viewed by some citizens as part of the intimidation of the judiciary by the executive. Whether this was true or not, it remains unconfirmed. But regarding the President issuing direct threats to the judiciary was seen as an executive influence on the judiciary.

In 2016, there were similar political threats to judicial independence by political actors. One of the notable threats was issued by the National Assembly Majority Leader Aden Duale who was quoted in the national news media saying that he "will not be intimidated from presenting a notice of motion to discuss the conduct of Justice George Odunga in Parliament in January next year"[20] [2017]. This followed censure by the Law Society of Kenya[21], Chief Justice David Maraga and CORD principals over his criticism of Justice Odunga. Mr. Duale stated on social media that the Constitution under Article 94 gives him the legislative powers to file a motion to discuss the conduct of a sitting judge. "I will be on record as the first Member of Parliament in independent Kenya who will bring a motion to discuss the conduct of a sitting judge," he declared. He indicated that as per the Standing Order 87, he intends to give notice of motion to discuss the conduct of Judge Odunga when house resumes in January 2017. He reiterated that any citizen can petition the Judicial Service Commission for the removal of the CJ or any other judge as per the constitution. "I would also want to remind CJ @dkmaraga that any citizen can petition the JSC for his removal or any other judge as per the constitution."[22]

To summarize on how the analytical model in figure 2.1 works and based on the aforementioned happenings, it is apparent that acts of intimidation and threats by political actors are real. If judges stand by their ethical obligation and don't allow themselves to be swayed by political threats or intimidations, then the concept of judicial independence is more hopeful. However, if judges allow the ideological distance between them to reduce to a level of interaction then judicial independence is likely to be threatened resulting in lack of justice and social disorder in society. Such ideological interactions should only be allowed when they are all purely based on moral norms, which guarantee justice and social order in society. This social order should be seen as the plinth or pedestal for underpinning judicial independence.

In the next sub-sections, factors perceived to be influencing judicial independence: judicial reforms, judicial selection, judicial corruption and constitutional safeguards are given profound treatment. Discussions provided in each of the sub-sections are grounded in relevant sociological theories and the generalizable analytical model in figure 2.1 above. The main focus is to make logical arguments on each of these theoretical predictions and make conclusions on how they potentially influence judicial independence in Kenya.

2.1. Judicial Reforms in Kenya

In recent years, there has been a reform engine fueled by both international and local forces on the need to reform legal and judicial systems in in many developing countries. For instance, Kenya, Ghana, Burkina Faso, Uganda, Sri Lanka, Mozambique, Costa Rica,

- 373/374 -

Ethiopia, Zambia, Nigeria, Tunisia and many others have undertaken some form of legal and judicial reforms under the auspices of the World Bank and the United Nations.[23] The overarching objective of these reforms is to strengthen judicial institutions. Kenya has therefore been 'proactive' on matters of judicial reforms. The initial judicial reforms started back in 1998 when the late Chief Justice Z.R. Chesoni appointed a committee of experts to look into a raft of issues that were bedeviling the judiciary: inefficiency, incompetence and corruption. The Chief Justice stressed that there was need for the Kenya's judiciary to inspire public confidence since the Kenyan public viewed judiciary with fear and suspicion. This called for the need to take appropriate steps to improve the image and performance of the judiciary in the administration of justice. These reforms were being fashioned against the spectacle of the historical dominance of the executive branch over the judiciary.

It is conceivably necessary to bring into emphasis that the initial judicial reforms in Kenya failed to establish a framework for a truly independent judiciary. Little attention was paid to the principle of 'judicial independence' as far as the initial reforms were concerned. The fact that judicial appointment was still squarely the ambit of the President meant that the executive arm of government still had a lot of influence in the administration of the judiciary. In other words, the Kenya's President remained a symbol of authority, influence and interaction in the judiciary. To give this phenomenon more perspective, symbolic interactionists believe that people attach meanings to symbols, and then they act according to their subjective interpretation of those symbols. In other words, since the President was perceived as the symbol of authority in the judiciary, it made it difficult for judges to be impartial, especially in adjudicating cases in which the executive had considerable interest.

The second attempt at introducing judicial reforms in Kenya was in 2003 after a political transition from President Daniel Arap Moi to President Mwai Kibaki in 2002. Another committee of experts was established headed by Justice Evans Gicheru, Judge of the Court of Appeal. The task of this committee was to outline the modalities and oversee the implementation process of the previous committee's recommendations and proposals. Corruption was seen as one of the major obstacles to justice delivery by the Kenya's judiciary. Addressing corruption as an obstacle to the rule of law, the new government led by President Kibaki set up the "Integrity and Anti-Corruption Committee of the Judiciary in Kenya to implement its policy known as "radical surgery."[24] This committee was headed by Justice Aaron Ringera who was also a judge of the superior court. Following the release of the Ringera Report in 2003, five out of nine Court of Appeal justices, 18 out of 36 High Court justices and 82 out of 254 magistrates were implicated as corrupt[25]. The government then ordered the publication of their names, which then appeared in the national press.

In a blatant display of raw, naked executive intimidation, the impugned judges and magistrates were issued a two-week ultimatum either to resign or be dismissed. They were never given a chance to mount a legal defense in fair and impartial proceedings. Some of

- 374/375 -

them voluntarily opted to retire while a few others decided to challenge dismissal in court. In what was again seen as bare- knuckle interference of the executive on the Kenya's judiciary, President Kibaki single-handedly appointed 28 acting High Court judges to replace the 18 who were dismissed. The appointment process raised serious concerns as to the 'casual' manner in which judges were appointed. Many people voiced concerns that the new judges may have been appointed in response to political, tribal and sectarian interests since there was lack of transparency or merit-based system in their appointment. This further fueled public disenchantment with the judiciary. The selection process undermined the public confidence in the quality of those named to the bench[26].

In both instances of undertaking the so called 'judicial reforms', it is apparent that the Kenya's judiciary was beholden to the executive interests and was more likely to pander to political partisans rather than being impartial. More emphatically, the spirit of judicial independence was subjected to a 'mockery'. Based on the aforementioned, a mere mentioning of "Judicial Independence" in Kenya would probably fail to throb many hearts. But one may ask, why would this be the case? The spirit of judicial independence in Kenya seems likely, one of the most 'tortured' virtues of Kenya's democratic principles. Despite the fact that judicial independence is being perceived as the first necessary 'ingredient' in the Kenya's justice system, this great virtue has produced less full and complete effects of judicial efficacy.

From a functionalist perspective, each aspect of society is interdependent and contributes to society's functioning as a whole. If all goes well, the parts of society produce order, stability, and productivity. If all goes wrong, the parts of society then must adapt to recapture a new order, stability and productivity. Clearly, what can be deduced from the judicial reforms in Kenya is "all goes wrong" situation, instead of "all goes well" in regards to the independence of the judiciary. All goes wrong because the executive arm has undue control over the judiciary. The remedy required to restore stability and order to the judicial independence is for the Kenya's executive to observe and respect the separation of powers doctrine.

The third round of judicial reforms in Kenya came about with the promulgation of the new 2010 Constitution. This is the Constitution that established the Supreme Court of Kenya and Hon. Justice Willy Mutunga was appointed as its President and the Chief Justice. "We found a judiciary that was designed to fail," said Willy Mutunga, Kenya's new chief justice, in a speech four months after his June 2011 confirmation to the post. "We found an institution so frail in its structures; so thin on resources; so low on its confidence; so deficient in integrity; so weak in its public support that to have expected it to deliver justice was to be wildly optimistic."[27]

The reforms under the new Constitution mainly focused on establishment of new courts, strengthening system of administration and creation of an all-inclusive Judicial Service Commission (JSC), which is a body in charge of recruiting, appointing and disciplining judges. The first new Court that was established under this new Constitution is the Supreme Court of Kenya. Other courts established were the Environment and Land Court

- 375/376 -

and the Employment and Labor Relations Court. Regarding strengthening system of administration, the Constitution created the position of Chief Registrar to improve service delivery. It also enabled the recruitment of 28 judges and additional magistrates through a vetting process that were seen as positive steps in the reform aimed at strengthening of justice in the country. But even with these reform efforts, their contribution to Kenya's judicial independence has not been adequate and effective. Even if we take, for instance, the creation of an all-inclusive JSC as 'ideal' for recruiting competent and impartial judges, the composition of the newly established JSC is still problematic.

Article 171 (1) of the Kenya's Constitution asserts that, "There is established the Judicial Service Commission[28]." The Commission consists of the Chief Justice who is also the Chairperson of the Commission, one Supreme Court Judge elected by the judges of the Supreme Court, one Court of Appeal judges elected by the judges of the Court of Appeal, one High Court judge and one magistrate, the Attorney-General, two advocates elected by the members of the Statutory body responsible for professional regulation of advocates, one person nominated by the Public Service Commission, and two non-lawyer representatives appointed by the President with the approval of the National Assembly. Out of the 11 members of this Commission, 4 of them are directly under the authority and control of the executive. The fundamental question that should then be asked is this: Does this purportedly all-inclusive JSC have the capacity to recruit and select impartial judges and strengthen judicial independence in Kenya's democracy?

The interesting thing about the Kenya's Judicial Service Commission is that 5 of its members are drawn from the bench through an election process by other judges of the bench. As is the practice in other civil law jurisdictions such as Hungary and Turkey where judges are appointed through independent bodies, such as Judicial Councils comprised mostly of judges,[29] the Kenya's Judicial Service Commission (JSC) serves a similar purpose of selecting judges. However, one would see that there is a lively debate regarding who should appoint judges to the JSC, who should be appointed and which procedure should be used? In Kenya, judges of the bench who are interested in becoming members of the JSC are required to campaign and pitch to be elected by their fellow colleagues. Just before leaving office in 2016, Chief Justice Willy Mutunga himself witnessed corruption in the judiciary when members of the bench were campaigning for new elections for the membership posts in the JSC. Justice Mutunga lamented that "elections to the country's Judicial Service Commission had been riddled with bribery." He observed that "It causes me a lot of pain that an election involving judges and magistrates would be corrupt," Justice Mutunga said, adding that there was evidence to back up his allegations. "Can you imagine a judge bribing another judge so that they can vote for them?" he asked.[30]

The question that one may ask is this: what should the Kenya's Chief Justice have done after witnessing 'first-hand' corruption in the Judiciary? The answer to this question can be successfully traced to the Kenya's Constitution. Indeed, if the Chief Justice was really disturbed about bribery and corrupt practices by members of the bench, then since by his

- 376/377 -

own admission there was sufficient evidence to show that some judges were involved in bribery, then the first step he should have taken was to report the matter to the Judicial Service Commission (JSC) for disciplinary purposes. Article 172 (1) (c) of the Kenya's Constitution asserts that functions of the JSC include: appointing, receiving complaints against, investigating and removing from office or otherwise discipline registrars, magistrates, other judicial officers and other staff of the judiciary. No sources has confirmed that the Chief Justice ever took any action against the corrupt members of the bench. This inaction by the Chief Justice undoubtedly leaved a dent on his ability to rein in corruption in the Judiciary and the President and the Chief Justice. It also became clear that the judiciary was condoning corruption by members of the bench. One would then wonder how a corrupt bench would fairly and competently adjudicate on corruption cases that come before them.

Chapter 6 of the Kenya's Constitution on Leadership and Integrity under Article 173 (2) (a) states that "The guiding principles of leadership and integrity include- selection on the basis of personal integrity, competence and suitability, or election in free and fair elections." Better still, under Article 166 (2) (c) of the Kenya's Constitution-"Each judge of the Superior Court shall be appointed from among persons who-have a high moral character, integrity and impartiality."[31] This law requires that all appointed or elected State officers must be men and women of personal integrity, competence and suitability. This conceivably means that even the incumbent judges (members of the bench) were appointed to the bench based on those moral and merit standards. If that was the criteria used by the JSC in appointing judges to the bench then it means that the practical aspects of personal integrity by members of the bench is also questionable. It sadly points to the fact that however fair the merit-based selection of judges is, it still does not usually translate into selecting judges of high moral standards to the bench.

To summarize discussions on judicial reforms in Kenya, it is very clear from the aforementioned that Kenya has been able to undertake a raft of judicial reforms. However, in the process of undertaking these reforms, the executive is still seen as interfering in the judicial selection process. Also, while the Judicial Service Commission is said to be independent, it is not necessarily impartial because it consists of 4 members who are directly under the executive authority. Finally, it is apparent that even the already appointed judges who sit in the bench and serve as members of the Judicial Service Commission get their appointments to the JSC through bribery of their fellow judges to win elections to serve as a member of the JSC. This therefore implies that the executive interference on the judiciary, the impartiality of the JSC and corruption among judges are strong impediments to judicial independence and they cannot simply be defeated by judicial reforms. This makes judicial reforms in Kenya look like a weak exercise incapable of effectively strengthening judicial independence.

Parsons (1951, 1971) had long observed that society is made up of systems and sub-systems. In fact, Parson emphasized that a society is a system of interdependent parts that tend toward equilibrium. This equilibrium means a state of harmony or calm in society due to social order. In this case, it can be said that the executive system, the judicial selection system and the judicial system all work together in quest for instituting judicial reforms. However, these systems need to function fairly in order to assure social order. For

- 377/378 -

instance, democratic political systems must embrace and respect separation of powers and checks and balances. This enables our democratic systems to operate optimally, hence a society with no conflict. Parsons also observed equilibrium is attained through social control-that is, sanctions imposed either informally through norms and peer pressure or through formal organizations, such as courts of law.

Drawing on Parsons' insights, it can be said that corruption among judges can be mitigated formally or informally through peer pressure. The Chief Justice, after witnessing first-hand judicial corruption among judges should have reported the matter to the JSC for formal action. At the same time, members of the bench including the Chief Justice should have informally castigated their colleagues for engaging in bribery for purposes of winning election to serve as members of the JSC. In this particular discussion, it can be emphatically said that each system has an obligation to demonstrate manifest functions. According to Merton 91968), manifest functions are actions that contribute to equilibrium that are tended to be recognized by members of society.

To summarize on this discussion, Solomon (2007) observed that it is both perplexing and incomprehensible why widespread, ambitious and costly institutional reforms lead only to limited results. The answer to addressing institutional failure could probably be linked to cultural attitudes, especially if they subordinate societal moral norms. In applying the analytical model in figure 2.1, it can be said that when systems that lack moral norms reduce their ideological distance to the level where their ideologies interact (panel c), then the outcome of that interaction is a social disorder. For instance, if you have an executive system that is impartial, a judicial selection body that is impartial and a judiciary that is impartial, then there is very little guarantee for the institutional independence of the judiciary. Judicial reforms in Kenya must aim at building a strong culture of judicial independence.

2.2. Judicial Selection in Kenya

Methods of judicial selection and their impact remain a contested debate. There are about four basic models of judicial selection: contested elections, legislative appointment, merit selection and gubernatorial appointment.[32] In some countries, however, the head of state appoints judges as a formal duty, but nomination or actual selection is done by political institutions such as legislature, executive or the judiciary itself. In Thailand, for example, each judge is appointed by the King, but only after the candidate has passed a judicial exam presided over by the courts, and then serve a one-year term of apprenticeship. This type of system can be considered one in which the judiciary plays the primary role, notwithstanding formal appointment by the King. [33]

Different countries with common law or civil law legal systems may use one or a variety of the above methods depending on the stipulated law on judicial appointment. The U.S. system, which is a common law system, for example, uses election for some state judges, and gubernatorial appointment in some states, but not at the Federal level. In Hungary, which is a civil law system, a merit-based selection is normally used through some version

- 378/379 -

of appointment by a judicial council is used.[34] Likewise, Kenya, which is a common law system also uses a merit-based selection through an 'independent' body known as the Judicial Service Commission.

Whichever method that is being employed to select judges, there is no single agreed method that is perceived to be superior to the others. They all have merits and demerits and no particular method can be said to guarantee judicial independence. Selection through an electoral system could be good for legitimacy and accountability reasons, but could be bad in the sense that it involves partisanship and therefore is unlikely to insure judicial independence. This method may also raise biasness and prejudice concerns. Merit-based selection could be good in terms of appointing the most qualified legal experts to the bench, but this does not in itself guarantee fairness and impartiality by the bench and is therefore also does not guarantee judicial independence. Appointment by political institutions such as the legislature could also be good in terms of legitimacy and accountability, but it might also raise concerns of pandering to political interests and thus less likely to insure independence of judges. This makes the practical realization of 'judicial independence' a contemporary challenge in many democracies around the world.

Article 166(1) of the Kenya's Constitution asserts that: "The President shall appoint (a) the Chief Justice and the Deputy Chief Justice, in accordance with the recommendation of the Judicial Service Commission (JSC), and subject to the approval of the National Assembly; and (b) all other judges, in accordance with the recommendation of the Judicial Service Commission. Article 171(1) of the Constitution establishes the Judicial Service Commission and prescribes its membership, which includes 4 judges of the superior courts (High court, Court of Appeal and Supreme Court), one Magistrate, the Attorney-General, 2 advocates, 1 member of the Public Service Commission and 2 members appointed by the President with the approval of the National Assembly. It is apparently clear that out of these 11 members, 4 of them are directly under the executive authority or control. Even though the Kenya's JSC is perceived to be an all-inclusive in its membership, questions still arise as to whether it is capable of impartially selecting impartial judges and fair enough to make fair selection.

Although the JSC is seen to consists of highly qualified individuals from different professions (legal and non-legal professionals), the selection process is to a large extent driven by politics. For instance, in regard to the appointment of the Chief Justice or the Deputy Chief Justice, the new Kenya's 2010 Constitution clearly stated that the JSC shall advertise for vacant positions in the judiciary then only qualified individuals are allowed to apply for vacant slots. Upon receiving applicants' requests, the JSC is required to carefully go through all the applications and then shortlist the most qualified candidates. Once the shortlisting has been done, the JSC sends out messages to all the shortlisted candidates to appear for an interview. During the interview, the past history, performance and conduct of each candidate is brought to public scrutiny and the candidate has to defend his or her past record.

Upon the completion of all interviews, the JSC was required by the Constitution to forward only one name for the position of Chief Justice and only one name for the position of the Deputy Chief Justice to the President for appointment. However, due to politi-

- 379/380 -

cal interests in judicial affairs, the majority ruling party (Jubilee coalition) made amendment to this critical part of the Constitution and the JSC will now be required to forward 3 names of candidates to the President for appointment instead of one name. This new law came into effect on December 15, 2015. Once the President makes his appointment of his preferred individual, he then forwards that name to the National Assembly and the Senate for approval or disapproval. In most cases, Kenya's Parliament usually approves Presidential appointees.

The Law Society of Kenya (LSK), which is a professional organization of all registered Kenyan advocates faulted the Kenya's National Assembly for making amendments to the law and thereby making it possible for the executive to interfere with the independence of the judiciary. The LSK went to Court to challenge the constitutionality of the new law arguing that it amended critical sections of the Judicial Service Act therefore interfering with judicial independence. "The Act as amended fundamentally upsets the doctrine of Separation of Powers between the three arms of government and should be suspended because the independence of the judiciary is at stake. The Constitution has clearly stated that the Judicial Service Commission (JSC) shall forward one name of a qualified person to the President for nomination as Chief Justice or Deputy Chief Justice but the Act has come up with a formulation requiring JSC to forward three names," said LSK through senior counsel Nzamba Kitonga. Unfortunately, Kenya's court declined to suspend law giving President the appointment power and the LSK lost the suit.[35]

According to international standards, judges must be appointed through strict selection criteria through fair and transparent process, which must be effective in safeguarding against appointments for wrong motives. International standards also require the authorities in charge of judicial selection and appointment of judges to be independent of the executive and legislative powers. Based on these standards, the Kenya's method of judicial selection and appointment still falls below the international standards. Although Kenya has an 'independent' body (JSC) mandated to recruit judges and magistrates, the body is not purely delinked from the executive and the legislative influence and is therefore less likely to guarantee fair selection and judicial independence.

In comparison to other jurisdictions, Hungary under civil legal system uses Judicial Council, which is a body equivalent to Kenya's Judicial Service Commission. The Venice Commission, in its Judicial Appointments Opinion concluded that an "appropriate method for guaranteeing judicial independence is the establishment of a Judicial Council, which should be endowed with constitutional guarantees for its composition, powers and autonomy and that such a Council should have a decisive influence on the appointment and promotion of judges and disciplinary measures against them." Since Hungary is a member of the European Union, its judicial selection method is bound by the Venice Commission.

The question that really matters is whether these judicial selection bodies (Judicial Service Commission or Judicial Council) can really guarantee a fair selection process that would eventually strengthen judicial independence. In Kenya, we have the so called merit-based selection of judges. Without being cynical, the process of merit-based selection is justifiable and needs to be encouraged. However, due to symbolic interaction factors, this

- 380/381 -

process is less likely to engender efficacious outcome, hence its inability to guarantee judicial independence. A better way to understand this is to consider the fact that Kenya is a multi-ethnic society and the country appears to be deeply divided along ethnic lines. Using the analytical framework of symbolic interactionism, Kenyans tend to favor members of their own ethnic tribe or political group more than those from outside their ethnic tribe or political group. Belonging to a particular ethnic community or political party is seen as a symbol that can either earn somebody a job or deny him, irrespective of his or her competence, academic qualifications and stellar credentials. Substantial subjectivity usually plays out and tends to override objectivity when it comes to "in-group" and "out-group" symbols of identity. This also applies to the judicial selection committee in Kenya.

Although the Kenya's Judicial Service Commission is said to be an 'independent' body and consists of professionals, the selection process cannot be said to be fully innocent of symbols of tribe and partisan politics. Strict professionalism is less likely to play a bigger role when it comes to judicial selection in Kenya. This is because members of the selection committee subtly apply the concept of ideological distance to candidates during the interview, and they make favorable approval of the candidate whose ideological distance (tribe and partisan politics) is closer to theirs. In essence, ideological polarization exists even among members of the selection committee and selection of candidates is based on the ideological distance. There is need, however, for merit plan selection system to be more transparent and strictly nonpartisan for its efficacy to be realized.

When judges are selected based on ideological distance (ethnicity, political affiliation), that is, when their identity ideology interacts with some members of the selection committee, then they are likely to reciprocate that gesture by establishing cooperation with those who selected him. This cooperation, based upon reciprocity, continues and each party has an incentive to cooperate for mutual benefits. The judge feels obligated to cooperate because he doesn't want to 'Burn Bridges' while the selection party also feels obligated to cooperate due to anticipated [future] litigation payoffs. In other words, each party has an incentive to cooperate[36]. In summary, merit-based judicial selections that are affected by ideological distance are more likely to influence the decisional independence of judges. Any time the ideological distance is reduced to a level of ideological interaction involving a judge and a member of the selection committee as is shown in figure 2.1 above, then professionalism gets subordinated and the whole merit-based system is turned into partisan-based system. This cannot assure the decisional independence of a judge.

To summarize on this discussion, when the executive system's ideology, judicial selection system's ideology and the judicial system's ideology are based on moral norms, even if their ideological distance is reduced to a level where they interact as seen in panel c of figure 2.1, then the outcome of that interaction will always be a social order that contributes to equilibrium in society. Institutional independence of the judiciary can be said to be that social order, hence equilibrium.

- 381/382 -

2.3. Judicial Corruption and Code of Professional Responsibility in Kenya

Maintaining the integrity and improving the competence of the bench to meet the highest standards of adjudication should be the unequivocal ethical responsibility of every judge. Fundamentally, good character in the members of the bench is essential to the preservation of judicial dignity and integrity of courts. This requires that judges should be of good moral character. A judge's fiduciary duty should be of the highest order and he or she must not represent interests adverse to justice as doing so would amount to travesty of justice. Neither should judges allow their private interests to conflict with those of litigants. It is very likely that a financial interest in the outcome of litigation might result in the maladministration of justice in courts. It is a fair characterization of judge's responsibility to stand as a shield and to ward off corruption. Corruption according to Black's Dictionary is characterized as: illegality; a vicious and fraudulent intention to evade the prohibitions of the law; moral turpitude or exactly opposite of honesty involving intentional disregard of law from improper motives; an act done with an intent to give some advantage inconsistent with official duty and the rights of others.[37]

To provide more perspectives on the issue of ethics, judges need to uphold both normative and practical ethics. On the one hand normative ethics ask questions such as: what is the best way, broadly understood, to live [as a judge]? Are there general principles, rules, guidelines that we should follow, or virtues that we should inculcate, that help us distinguish right from wrong and good from bad?[38] On the other hand, practical ethics ask questions such as: how should we behave in particular situations [as judges]? When should we tell the truth? Under what circumstances can or should we resist gifts or inducements? How should we relate to the political and social environment around us? Most important, however, judges need to understand that ethics is primarily a matter of practice-and not a matter of abstract moral knowledge.[39] Inadequate knowledge of normative ethics is more likely to weaken the enforcement of practical ethics and thus resulting into loose morals such as indulgence in corruption by judges. In fact, judges should find acts of corruption or bribery sufficiently repulsive that they would thereby be motivated to refrain from indulging.

Scholars agree that a non-corrupt judiciary is a fundamental condition for the endorsement of rule of law and the ability to guarantee basic human rights in society. The judiciary must therefore be an independent and fair body that fights corruption, not the other way around.[40] Further, the effects of corruption might be detrimental and more likely to break down the very core of rule of law and this may lead to corrupt judges neglecting fundamental principles such as equality, impartiality, propriety and integrity (Arvidson and Folkesson 2010). The question that must be grappled with is whether the Kenya's judiciary has taken the right steps in ensuring that mechanisms of judicial independence are strengthened so as to prevent corruption within the judiciary itself.

Prior to the 2002 political transition from President Daniel Arap Moi to President Mawai Kibaki, the Kenya's judiciary was widely known to be corrupt. In fact, when the new

- 382/383 -

government took office (the Kibaki administration), it addressed corruption as an obstacle to the rule of law and vowed to deal with the vice. To be seen to be wedding rhetoric with action, the new government set up the "Integrity and Anti-Corruption Committee of the Judiciary in Kenya" to implement its policy known as "radical surgery." The report of this committee saw several judges retiring due to implications in various corrupt practices. While this measure was seen as a step in the right direction to clean up the Kenya's Judiciary of corruption and to restore public confidence in the Judiciary, it would only last for a few months if not weeks. This was the case because the intended judicial reforms failed to establish a framework for truly independent and accountable judiciary.

In May 2002, an Advisory Panel of Eminent Commonwealth Judicial Experts visited Kenya to give recommendations and proposals on the Judiciary and in their report, they indicated that there was rampant corruption in the Kenya's Judiciary and bluntly stated that "complaints of corruption exceeded level that can be expected or tolerated.[41] Further, in a survey conducted in September 2002 by the International Commission of Jurists to (ICJ) assess the perceptions of the Kenyan public (consumers of justice) on judicial reforms and the impact on the administration of justice in Kenya, 92 percent of the responses indicated that the civil division of the Court was corrupt followed by criminal division at 83 percent, commercial division at 73 percent and family division at 42 percent. [42] A similar ICJ report in 2005 concluded corruption in the administration of justice, including the judiciary, has been a serious impediment to the rule of law in Kenya. The report indicated that "while corruption is a principal obstacle to the proper functioning of an independent judiciary in Kenya, anti-corruption measures themselves must be implemented in a way that strengthens and does not weaken the separation of powers and the independence of the judiciary."[43]

The new 2010 Kenya's Constitution under Article 173 (1) established a fund to be known as the 'Judiciary Fund' and gave the Chief Registrar of the judiciary the responsibility of managing the fund. Article 173 (2) of the 2010 Constitution states that: "The Fund shall be used for administrative expenses of the Judiciary and such other purposes as may be necessary for the discharge of functions of the Judiciary. In essence, the 2010 Constitution gave the Kenya's judiciary some latitude on how to manage its own finances without strict regulations. What followed in 2013 was a shock to the nation. Chief Registrar of the judiciary, Gladys Boss Shollei and seven senior officials were charged with massive corruption including irregular procurement of building materials[44].

Judiciary Chief Registrar Gladys Shollei was then sacked by her employer, the Judicial Service Commission (JSC), over allegations that she misused Sh2.207 billion. The JSC president Chief Justice Dr. Willy Mutunga said she (Shollei) had been fired for incompetence, misbehavior, violation of the code of conduct for judicial officers, insubordination and violation of Chapter Six and Article 232 of the Constitution. Article 232 asserts the values and principles of public service, which include (a) high standards of professional ethics and (b) efficient, effective and economic use of resources. In a detailed statement, Dr Mutunga

- 383/384 -

said Mrs Shollei had admitted 33 allegations in which Ksh1.7 billion "is at risk or has been lost". Mrs Shollei allegedly also denied another 38 allegations in which Sh250 million was lost. The JSC stated that her responses to allegations involving Sh361 million were "mixed, flippant and flimsy". "Having fully appreciated the allegations served on her, and having read the responses, and noting that she elected to appear in person before the commission, and after in-depth interrogation of all issues, it is the unanimous resolution of the commission that the Chief Registrar of the Judiciary is hereby removed from office with immediate effect," said Dr Mutunga[45].

In its 2015 Corruption Index, Transparency International (TI) ranked Kenya as a highly corrupt Country in the East African region, ahead of Uganda, Tanzania, Burundi and Rwanda. Kenya was ranked 139 out of 167 countries.[46] According to the International Commission of Jurists report of 2002, corruption had taken root in every sector of Kenya that even the Judiciary could not escape it.[47] "Various reports published, especially from mid-eighties to date have indicated that corruption is very serious in the Judiciary. Thus the Judiciary is no longer viewed to be above suspicion and consequently, many people no longer look up to it as the protector and guarantor of citizens' rights and freedoms. On many numerous occasions, government officials and the wealthy have used this institution to get illegal orders for their own selfish interests without due consideration to the law and or people's rights."[48] It is therefore little surprising that a few years ago, Mazingira Institute, (a domestic transnational organization and an activist progressive participant in local and global social process), launched a vigorous campaign against judicial corruption using the slogan "Why hire a lawyer when you can buy a judge?" This clearly shows how judicial corruption in Kenya had gotten out of hand.

Just recently in 2016, one of the Kenya's Supreme Court justices was accused of allegedly receiving bribes to influence an election petition case before the Supreme Court. The Judicial Service Commission received complaints of the alleged offense and accordingly advised the Kenya's President to constitute a tribunal to investigate the accused judge[49]. The President then appointed a seven-member tribunal to investigate Justice Philip Tunoi's conduct in connection with an election petition lodged by Ferdinand Waititu against his opponent, Nairobi Governor Dr. Evans Kidero[50]. It was alleged that Justice Tunoi received a bribe of $2 million to rule in favor of Governor Evans Kidero. The then Law Society of Kenya (LSK) President, Mr. Eric Mutua reiterated that "If the allegations against the judge are true, then the judge must have taken this money on behalf of at least two or three other judges" sitting on the bench. This case was seen as the first of its kind to test the credibility of the Kenya's Supreme Court which was established when the country promulgated a new constitution in 2010. Article 168 (1) (b) of the Kenya's Constitution

- 384/385 -

asserts that "A judge of a Superior Court may be removed from office on the grounds of-a breach of a code of conduct prescribed for judges of the Superior Courts by an Act of Parliament."

Unfortunately, however, even before the sitting tribunal completed its hearing on the matter, it got disbanded. This was because there was a concurrent case going on at the Supreme Court lodged by Justice Philip Tunoi challenging the decision of the JSC to retire him at the age of 70, which was the official retirement age as per the new 2010 Constitution, instead of being retired at the age of 75, which was the official retirement age of judges according to the old Constitution. Justice Tunoi had argued that since he was hired under the old Constitution which provided for his retirement age at 75, the new Constitution's age requirement of 70 should not affect him. The Supreme Court, however decided to uphold the Court of Appeal decision, which had decided that justice Tunoi's retirement age should be at 70 and not 75. When the judge was being investigated, his age was already past 70 with some months. The tribunal decided to disband without completing its work because it now treated justice Tunoi as a retired judge who the Tribunal did not have any authority or a mandate to investigate. Based on the aforementioned happening, whether or not it was true that justice Tunoi accepted bribe from Governor Evans Kidero remained mere speculation since the tribunal did not give its verdict[51].

The Kenya's new Chief Justice, David Maraga, who came into office in 2016 and having only stayed in office for a few months admitted there was corruption in the Judiciary. According to Justice Maraga, 10 percent of the staff in the judiciary including judges and clerks were involved in graft which was tainting the name of the institution[52]. Up to this far, a lucid account has been provided of alleged bribery, corruption and misconduct by judges and staff members of the Kenya's judiciary. The focus hereafter then should be on how the potent of corruption in the Kenya's judiciary influences (impedes or weakens) its judicial independence.

There are contradicting and perhaps, stimulating views as to whether it is the presence of judicial corruption that impedes judicial independence or the other way round, which is, presence of judicial independence impedes judicial corruption. Some people see judicial corruption as responsible for undermining the rule of law. One the one hand, some scholars argue that the presence of judicial corruption compromises the capacity of the judiciary to be an independent and impartial arbiter[53]. Arvidsson and Folkesson (2010) makes interesting observation on the relationship between corruption and judicial independence and concludes that corruption weakens judicial independence[54]. On the other hand, there are those who argue that the presence of judicial independence weakens judicial corruption[55]. "Bearing in mind the independence of the judiciary and its crucial role in combating corruption, each State Party shall, in accordance with the fundamental principles of its legal

- 385/386 -

system and without prejudice to judicial independence, take measures to strengthen integrity and to prevent opportunities for corruption among members of the judiciary" (United Nations Convention Against Corruption, Article 11)[56]. Apparently, even according to the UN Convention Principles, judicial independence is critical to preventing judicial corruption.

To summarize on this discussion, judges cannot be said to be some "Angels" siting in the bench. They are also human beings who experience numerous everyday encounters with creditors, debtors, landlords, tenants, families (Cotterrell 1992), and other state actors or agents. They also want to enjoy their freedom and rights of investing and owning properties. Even though their conduct of judges is strictly regulated by code of ethics, it is very likely that normative conflict may arise and if the judge is not very careful about preventing himself from co-optation, then he would be in essence allowing the ideological distance between himself and the other actors (political agents, creditors, business partners, family members) to significantly reduce to a level of ideological interaction. When that happens, then the ethical norms of the judge may get subordinated and the judge will be co-opted in the immoral norms in society. It is only moral norms that play an important role in establishing social order in society. Immoral norms may, however, establish cooperation of actors whose intentions are inimical to social order. This phenomenon may lead to threats on the decision independence of the judge.

2.4. Constitutional Safeguards to Judicial Independence in Kenya

Kenya has been able to provide constitutional safeguards for members of the bench by ensuring that all judges enjoy security of tenure and earn better salary so that they can comfortably do their job without fear or favor. Article 167 of the Kenya's Constitution asserts, "Tenure of office of the Chief Justice and other judges." This law requires judges to work until they reach the age of 70 then they can retire. The usual retirement age for all public servants in Kenya is at 60 years. Also, Article 160 (4) says that subject to Article 168 (6) of the Constitution, the remuneration and benefits payable to, or in respect of, a judge shall not be varied to the disadvantage of that judge, and the retirement benefits of a retired judge shall not be varied to the disadvantage of the retired judge during the lifetime of that retired judge. Further, Article 160 (5) of the Kenya's Constitution says that, "A member of the Judiciary is not liable in an action or suit in respect to anything done or omitted to be one in good faith in the lawful performance of a judicial function.

These constitutional safeguards serve to embolden judges so that they can do their work with courage and diligence. However, the aforementioned discussion reveal that even with all these constitutional protection of judges and the judiciary, the Kenya's executive and legislative arms still have unfettered nerves to berate judges and intimidate the judiciary. This further makes the plinth of judicial independence in Kenya to be on shaky ground. Unleashing attacks on the judiciary, especially if it is being done by the executive serve as strong signals or symbols of threat to judicial independence. It reveals that both the judiciary and the executive are not on the one side of moral norms. As the analytical

- 386/387 -

model in figure 2.1 reveals, if the ideological distance is at panel (a), then the executive issues threats to reduce that distance to a level of panel (c) where it can actually force the judiciary to give in to its (executive's) ill-designs. The outcome of this co-optation is likely to be a social disorder (impartiality), hence lack of independence of the judiciary.

3. Methodology

Descriptive research method has been employed for the treatment of the topic of this paper. This method is more attractive because the main interest here is to be able to describe specific behavior in regards to judicial independence as they occur in the Kenya's society. According to Aggarwal (2008) descriptive research is very useful for gathering of information about prevailing conditions or situations for the purpose of description and interpretation[57]. This type of research method is not simply used for amassing and tabulating facts but includes proper analyses, interpretation, comparisons, identification of trends and relationships.

3.1. Data and Analysis

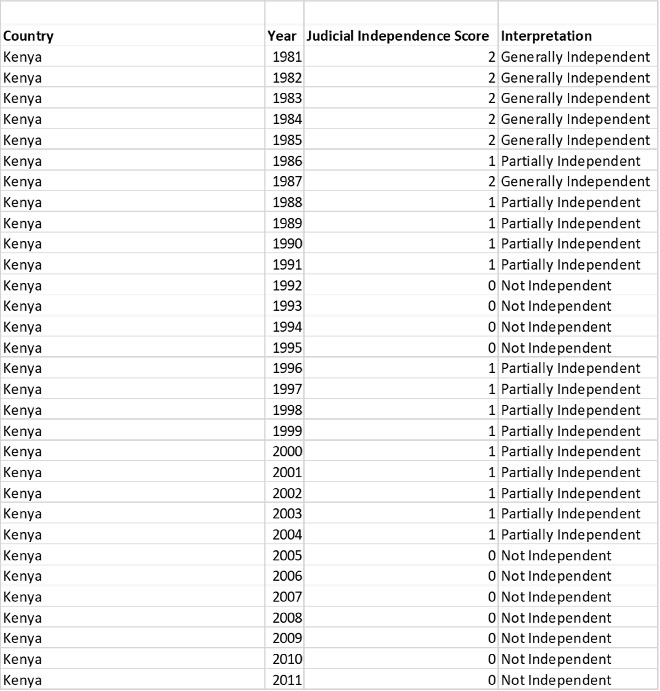

Specifically, datasets used draw on two different survey research design conducted by the Afrobarometer, and The CIRI Human Rights Data. Survey research design is important as it employs applications of scientific method by critically analyzing and examining the source materials, by analyzing and interpreting data, and by arriving at generalization and prediction[58]. Afrobarometer is a pan-African, non-partisan research network that conduct public attitude surveys on democracy, governance, economic conditions, and related issues in more than 35 countries in Africa. It collects and publishes high-quality, reliable statistical data on Africa. Two batteries of (survey) questions that specifically focus on judicial corruption in Kenya were selected. The first question asked respondents their perception on corruption among judges and magistrates in Kenya, while the second survey question asked respondents about their trust on courts of law in Kenya. These two questions are considered important in unravelling the perceived level of judicial corruption in Kenya for the period between 2005 and 2011. Afrobarometer has an online statistical tool for data visualization and it was effectively used to visualize data presented in section 3.2 below. The data has mainly been visualized in form of bar charts and pie charts and thus provides a summary of the entire question regarding perceived judicial corruption in Kenya.

The CIRI Human Rights Dataset contains standards-based quantitative information on government respect for 15 internationally recognized human rights for 2002 countries annually from 1981-2011. In particular, the dataset contains a variable known as INJUD (independence of the judiciary), which indicates the extent to which the judiciary is independent of control from other external sources of power. Since the topic of study focuses exclusively on Kenya, observations on the variable INJUD are extracted from this dataset

- 387/388 -

to illustrate the extent of judicial independence in Kenya for the period between 1981 and 2011. The illustration is lucidly provided using raw data in a table format.

3.2. Statistical Results

Statistical results presented in figures below contain two survey questions from the Afrobarometer. The first question was asked in rounds 3 to 6 of the Afrobarometer survey and it mainly examined perception on corruption involving judges and magistrates in Kenya from 2005 to 2015. Responses to this question are presented in the bar charts below. The second question is focusing on the perceived trust in courts of law in Kenya from 2005 to 2015. Responses to this question are provided in pie charts below.

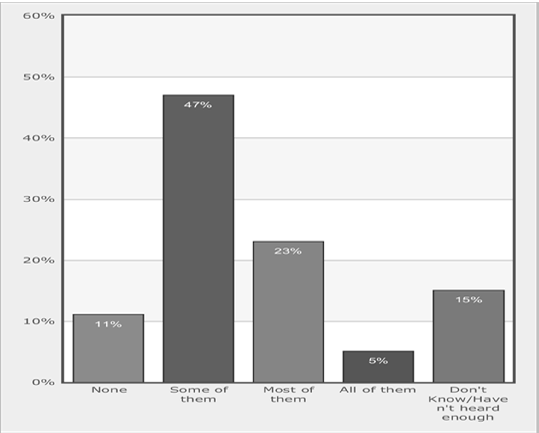

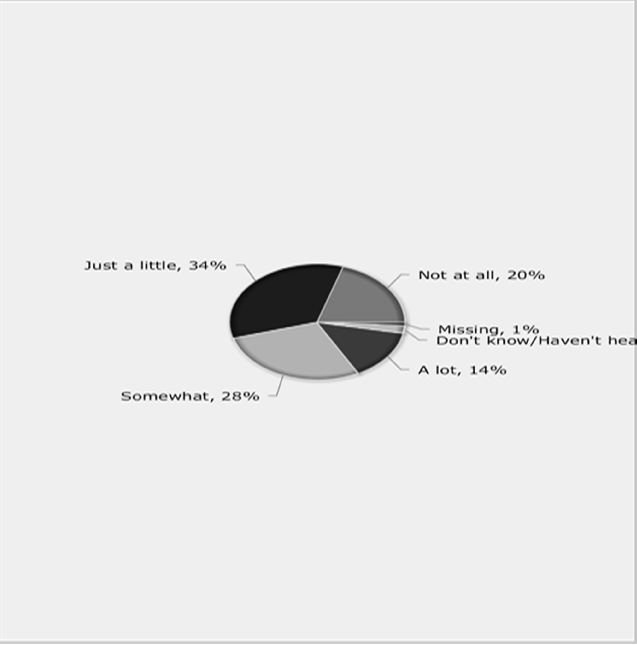

Fig. 3.2.1(a)

Perception on corruption among judges and magistrates in Kenya

Source: Afrobarometer Survey (R3 2005/2006) on judicial corruption in Kenya

The bar chart above represents round 3 of public responses on perceived corruption among judges and magistrates in Kenya between 2005 and 2006. A total of 1,278 respondents took the survey and 135 of them (10.5 percent) felt that none of judges and magistrates were corrupt, 600 (46.7 percent) believed that some judges and magistrates were corrupt, 290 (22.7 percent) believed that most judges and magistrates were corrupt, 67 (5.3 percent) felt that all judges and magistrates were corrupt, and 187 (14.6 percent) answered that they were not aware whether judges and magistrates were corrupt.

- 388/389 -

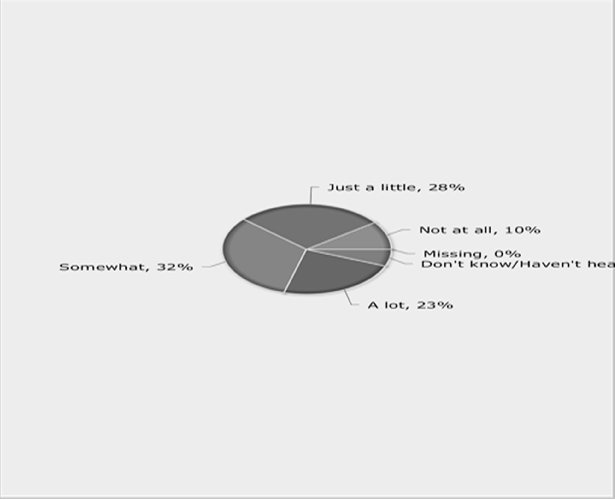

Fig. 3.2.1(b)

Trust on Courts of Law in Kenya

Source: Afrobarometer Survey (R3 2005/2006) on trust on courts in Kenya.

The pie-chart in fig. 3.1 (b) above represents Afrobarometer survey R3 conducted between 2005/2006 results. The survey question asked a total of 1,278 respondents how much they trusted courts of Kenya. 127 of the respondents (9.9 percent) said they don't trust courts of law at all, 360 (28.2 percent) said they trusted courts of law just a little, 412 (32.2 percent) said that they somewhat trust courts of law, 299 (23.4 percent) said they trusted courts of law a lot, while 74 (5.8 percent) answered they didn't anything about courts of all and 6 (0.5 percent) failed to answer.

- 389/390 -

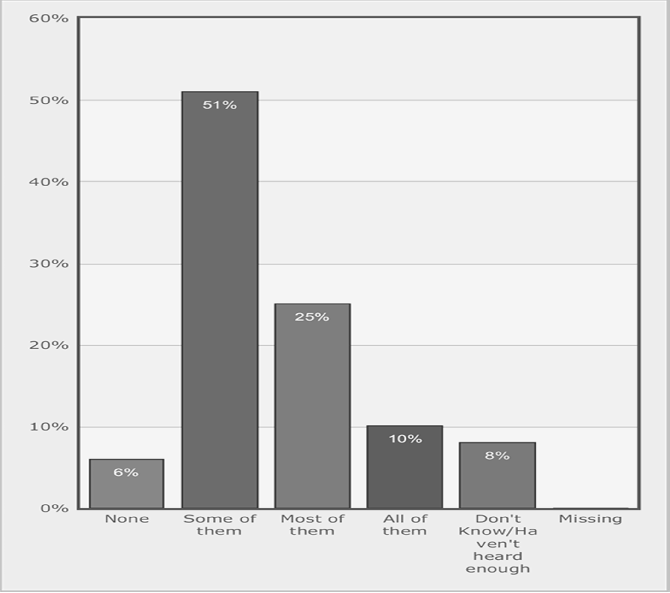

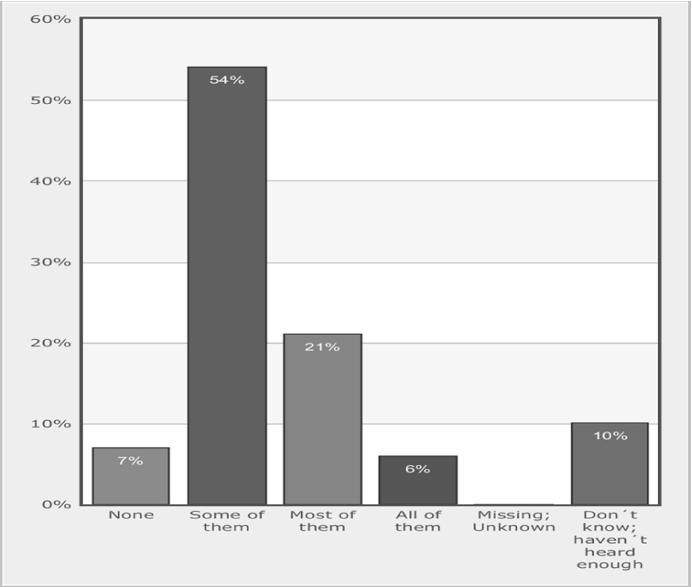

Fig.3.2.2 (a)

Perception on corruption among judges and magistrates in Kenya

Source: Afrobarometer Survey (R4 2008/2009) on judicial corruption in Kenya

The bar chart above represents round 4 of public responses on perceived corruption among judges and magistrates in Kenya between 2008 and 2009. A total of 1,104 respondents took the survey and 63 of them (5.7 percent) felt that none of judges and magistrates were corrupt, 563 (51 percent) believed that some judges and magistrates were corrupt, 278 (25.2 percent) believed that most judges and magistrates were corrupt, 113 (10.3 percent) felt that all judges and magistrates were corrupt, 86 (7.8 percent) answered that they were not aware whether judges and magistrates were corrupt, and 2 (0.2) failed to answer.

- 390/391 -

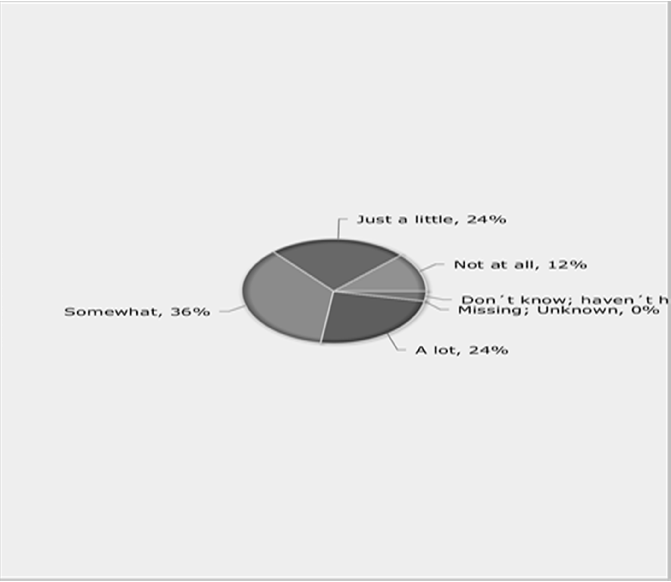

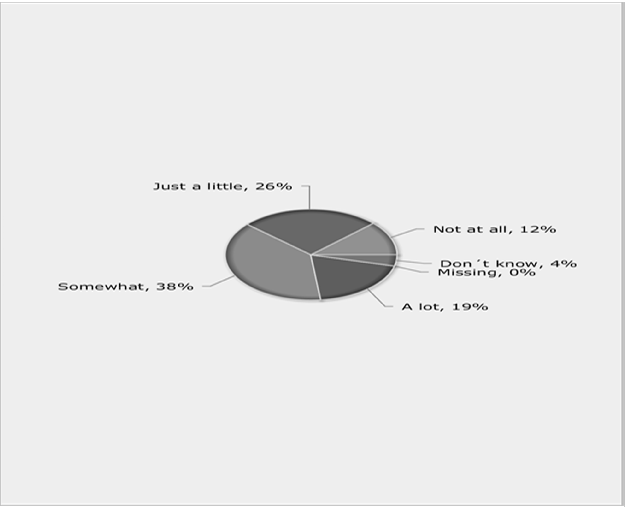

Fig. 3.2.2 (b)

Trust on Courts of Law

Source: Afrobarometer Survey (R4 2008/2009) on trust on courts in Kenya

The pie-chart in fig. 3.2 (b) above represents Afrobarometer survey R4 conducted between 2008/2009 results. The survey question asked a total of 1,104 respondents how much they trusted courts of Kenya. 225 of the respondents (20.3 percent) said they don't trust courts of law at all, 379 (34.3 percent) said they trusted courts of law just a little, 308 (27.9 percent) said that they somewhat trust courts of law, 156 (14.1 percent) said they trusted courts of law a lot, while 25 (2.2 percent) answered they didn't anything about courts of all and 12 (1.1 percent) failed to answer.

- 391/392 -

Fig. 3.2.3 (a)

Perception on corruption among judges and magistrates in Kenya

Source: Afrobarometer Survey (R5 2011/2013) on judicial corruption in Kenya

The bar chart above represents round 5 of public responses on perceived corruption among judges and magistrates in Kenya between 2011 and 2013. A total of 2,399 respondents took the survey and 172 of them (7.2 percent) felt that none of judges and magistrates were corrupt, 1,305 (54.4 percent) believed that some judges and magistrates were corrupt, 516 (21.5 percent) believed that most judges and magistrates were corrupt, 152 (6.4 percent) felt that all judges and magistrates were corrupt, 251 (10.5 percent) answered that they were not aware whether judges and magistrates were corrupt, and 3 (0.1) failed to answer.

- 392/393 -

Fig. 3.2.3 (b)

Trust on Courts of Law

Source: Afrobarometer Survey (R5 2011/2013) on trust on courts in Kenya

The pie-chart in fig. 3.2.3 (b) above represents Afrobarometer survey R5 conducted between 2011/2013 results. The survey question asked a total of 2,399 respondents how much they trusted courts of Kenya. 281 of the respondents (11.7 percent) said they don't trust courts of law at all, 564 (23.5 percent) said they trusted courts of law just a little, 874 (36.5 percent) said that they somewhat trust courts of law, 587 (24.5 percent) said they trusted courts of law a lot, while 10 (0.4 percent) answered they didn't anything about courts of all and 82 (3.4 percent) failed to answer.

- 393/394 -

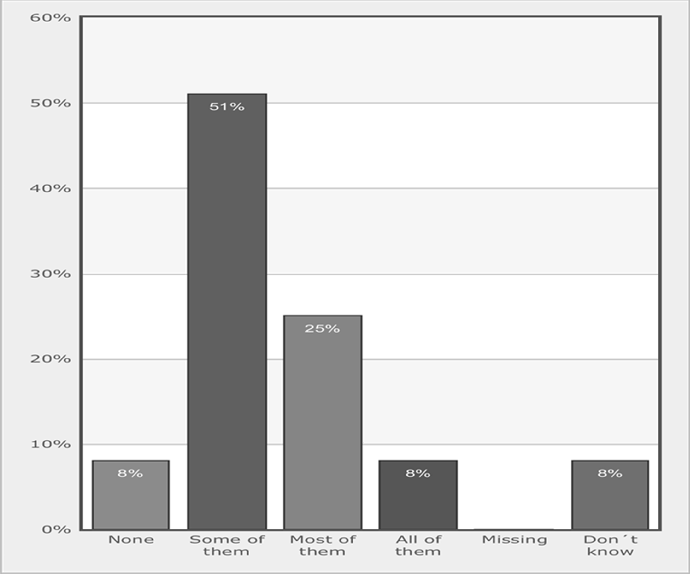

Fig 3.2.4 (a)

Perception on corruption among judges and magistrates in Kenya

Source: Afrobarometer Survey (R6 2014/2015) on judicial corruption in Kenya