Andrzej Paduch[1]: Fair Administrative Trial after COVID-19 Pandemic (ELTE Law, 2023/1., 71-83. o.)

https://doi.org/10.54148/ELTELJ.2023.1.71

Abstract

The article addresses the problem of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the scope of the notion of fair administrative trial. Legal measures adopted in different countries in connection with the pandemic have modified the course of court proceedings, in particular those conducted before administrative courts. Will these modifications be permanent? The answer will be given using the dogmatic-legal and comparative method. On the basis of these, an analysis of acts of international law regulating the right to a fair trial is conducted. Selected works on the particular court proceedings' modifications in connection with the COVID-19 pandemic are also analysed.

First, the article analyses the concept of fair administrative trial, pointing out two of its aspects, which were particularly threatened by the measures adopted in the pandemic era: openness of the proceedings and reasonable time. The second part of article identifies the legal measures adopted in different countries, dividing them into two groups, measures of suspension and measures of transformation. The first group led to the temporary suspension of court procedures. The measures from the second group limited the openness of the procedure, transferring its course to closed, remote or hybrid hearings. The third part of the article indicates possible paths for modifying the fair administrative trial after a pandemic.

In conclusion, the author states that although the concept of fair trial itself has not changed, some of the measures adopted constitute its more complete protection and, as such, should remain in individual legal systems.

Keywords: COVID-19, fair trial, administrative judiciary

- 71/72 -

I. Introduction

The right to a fair trial is undoubtedly one of the most fundamental human rights.[1] This is because only when the trial meets the conditions of a fair one is it possible to determine the legal situation of an individual effectively, or to verify the obligations imposed on him or her, or to determine the rights to which they are entitled. The concept of the right to a fair trial has been known for decades and is already mentioned in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.[2] In general, it consists of the right to a public hearing without undue delay by an independent tribunal established by law.

The above-mentioned aspects of the right to a fair trial should always be met. This means that lawmakers should shape procedural law in such a way that the indicated elements of the right to a fair trial are met, even in the event of special circumstances in which maintaining the guarantee of human rights protection is difficult.[3] Moreover, if any of the aspects could not be guaranteed - the court case should be suspended from being heard.

The article analyses the scope of the notion of the right to a fair trial in a specific set of circumstances - in the context of the post COVID-19 pandemic world. The massive incidence of this disease and the various precautionary measures introduced as a result[4] (including the prohibition of movement and business activity - lockdowns[5]) undoubtedly made it very difficult to maintain the guarantee of a fair trial as presented above. At the same time, it was not possible to suspend the examination of all court cases until the end of the pandemic: it is difficult to imagine a situation in which courts would not decide any cases for 2 or 3 years.[6] For this reason, the legislators of various countries have introduced

- 72/73 -

many measures aimed at strengthening the guarantees of the right to a fair trial in these specific circumstances. This raises the question of whether the right to a fair trial currently has a different meaning or scope than before the outbreak of the pandemic. What normative shape should it be given after the end of the COVID-19 pandemic?

When looking for answers to the above questions, the dogmatic-legal method will be used, on the basis of which the normative acts regulating the right to a fair trial at the international level will be analysed. A comparative method will also be used, comparing the model of the right to court, resulting from different acts of international law. Other studies on the modification of the course of the trial in connection with the COVID-19 pandemic will also be analysed. The analysis will be carried out as follows: first, the concept of a fair administrative trial will be examined under international law; then the typical anti-COVID court measures will be presented. The last part of the article is devoted to the possible paths for modifying the scope of the fair administrative trial concept in the post-pandemic period.

II. The General Concept of Fair Administrative Trial in International Law

The concept of the right to a fair trial has been formulated in many different acts of international law. From the European perspective, there are four basic normative acts which indicate the right to a fair trial as an element of the standard of trial in a democratic state. These acts were adopted by various international organisations, including cooperation of states at the regional and global level. As regards the first circle of cooperation, it is necessary to point to the acts adopted within the Council of Europe [European Convention on Human Rights[7] and Recommendation R (2004) 20 on judicial review[8]] and the European Union (Charter of Fundamental Rights of The European Union[9]). It has to be mentioned that the last document not only establishes the right to a fair trial in matters transferred to the EU as such, but also gives it the same meaning as that adopted on the basis of the ECHR.[10]

- 73/74 -

As part of the global scope of cooperation, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights[11] should be noted. This act was adopted under the auspices of the UN.[12]

When comparing the wording of the provisions on the right to a fair trial in the acts mentioned above, it should be assumed that they provide for the same concept. Although it is not verbally established in most of them, the concept of fair trial applies also to judicial review.[13] However, the ECtHR excluded tax, immigration, election law, military service and customs law from the scope of civil matters in art. 6 sec. 1 ECHR. These cases were recognised as the exclusive prerogatives of the state, not subject to the jurisdiction of the ECtHR.[14] However, there are, in principle, no similar exceptions in the case of the other acts mentioned. Therefore, it seems that a uniform standard of the right to a fair trial has been created at the international law level, as shown in the table below.

- 74/75 -

Table 1.

Summary of provisions regulating the right to a fair trial at the international level Source: the author's own work

| European Convention on Human Rights | Art. 6 sec. 1: In the determination of his civil rights and obligations or of any criminal charge against him, everyone is entitled to a fair and public hearing within a reasonable time by an independent and impartial tribunal established by law. Judgment shall be pronounced publicly but the press and public may be excluded from all or part of the trial in the interests of morals, public order or national security in a democratic society, where the interests of juveniles or the protection of the private life of the parties so require, or to the extent strictly necessary in the opinion of the court in special circumstances where publicity would prejudice the interests of justice. |

| Recommendation R (2004) 20 on judicial review | Art. 4 Sec. A: The time within which the tribunal takes its decision should be reasonable in the light of the complexity of each case and of the procedural steps or postponements attributable to the parties, while respecting the adversary principle. Sec. F: The proceedings should be public, other than in exceptional circumstances. |

| Charter of Fundamental Rights of The European Union | Art. 47 sentence 2: Everyone is entitled to a fair and public hearing within a reasonable time by an independent and impartial tribunal previously established by law. Everyone shall have the possibility of being advised, defended and represented. Art. 52 sec. 3: In so far as this Charter contains rights which correspond to rights guaranteed by the Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms, the meaning and scope of those rights shall be the same as those laid down by the said Convention. This provision shall not prevent Union law providing more extensive protection. |

| International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights | Art. 14 sec. 1: All persons shall be equal before the courts and tribunals. In the determination of any criminal charge against him, or of his rights and obligations in a suit at law, everyone shall be entitled to a fair and public hearing by a competent, independent and impartial tribunal established by law. The press and the public may be excluded from all or part of a trial for reasons of morals, public order (ordre public) or national security in a democratic society, or when the interest of the private lives of the parties so requires, or to the extent strictly necessary in the opinion of the court in special circumstances where publicity would prejudice the interests of justice; but any judgement rendered in a criminal case or in a suit at law shall be made public except where the interest of juvenile persons otherwise requires or the proceedings concern matrimonial disputes or the guardianship of children. |

- 75/76 -

In the abovementioned context, two aspects of the right to a fair trial, which are important from the pandemic perspective, are the openness of the proceedings and the reasonable duration of the proceedings. According to the ECtHR, openness of the proceedings means such a structure of a court process in which social control of its course is guaranteed by its participants (parties), third persons or the media.[15] Openness of the proceedings means, on the one hand, a public trial and, on the other, a public announcement of the decision.[16] A special element of the above is the right of the party to be heard, which should be guaranteed in at least one instance.[17] On the other hand, reasonable time of the proceedings refers to the examination of a case in which the activities of the proceedings are performed continuously, i.e. there are only necessary and justified breaks between individual activities.[18] The task of this element is to protect parties against excessive delays in legal proceedings, and underline the importance of rendering justice without delays.[19]

III. Anti-COVID Measures in the Field of Administrative Judiciary

The outbreak of the pandemic made it necessary for legislators to react quickly in many aspects of life. At first, many states adopted some strategies of combating COVID-19 in general.[20] The subject of those acts was primarily the legal and sanitary framework for

- 76/77 -

combating COVID-19.[21] However, its provisions also indirectly related to the course of court proceedings, including those before administrative courts. For instance, in Poland, this took place under the Act of 2 March 2020 on special solutions related to preventing, counteracting and combating COVID-19, other infectious diseases and emergencies caused by them.[22] These acts limited the possibility of people gathering, created a framework for remote work, and introduced benefits for employers potentially affected by the pandemic.[23]

Difficulties in organising court work and appearing in court - resulting from both legal restrictions (e.g. lockdown) and factual circumstances (increasing number of COVID cases, resulting changes in plane, bus or train timetables, etc) may have resulted in the fact that leaving court procedures unchanged could lead to an actual violation of either the principles of active participation of a party in court proceedings or the principle of reasonable time of the proceedings. For these reasons, it was necessary to adopt appropriate measures.

Therefore, some instruments focused on guaranteeing the openness of the proceedings. Since it was legally impossible or difficult to attend court hearings, for example, decisions were made to suspend court proceedings until the number of cases was reduced.[24] Those measures of suspension could be grouped as follows:

1) suspension of hearing cases,

2) suspension of initiating a court case,

3) suspension of time limits,

4) temporarily limited access to court buildings, court documents and court clerks.

The aim of the indicated group of measures was - apart from ensuring the safety of the population, including court clerks - to secure the right to file a court case and openness of the proceedings. At the very beginning of pandemic in particular, it was not known how long it would last; it was then assumed that the duration of the pandemic would not be long. Therefore, temporary difficulties in access to court or postponing hearings were considered as effective tools for of guaranteeing a fair trial, which would take place in future.

- 77/78 -

The lengthening period of the pandemic made it necessary to adopt a different strategy, including strengthening the aspect of speed of proceedings by increasing the number of cases heard remotely, online or in closed sessions.[25] Those measures would transform the traditional courtroom into a remote or virtual one, or transform oral procedures into procedures in writing. Those measures are:

1) limited access to open hearings,

2) hearing in camera instead of open hearings,

3) written hearings (or proceedings in writing) instead of open or limited hearings,

4) hearings online.

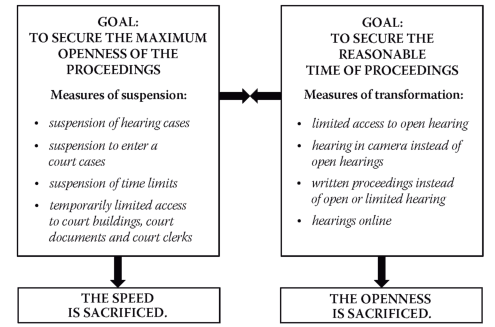

The second group of measures therefore refers to the enhancement of the speed of the procedure, by limiting its openness at the same time. Similarly, the previously analysed measures of suspension were to ensure the openness of procedures at the expense of their speed. This dependence is presented in the graph below:

Graph 1.

The dependence between securing openness and reasonable time of court proceedings

Source: the author's own work

- 78/79 -

Therefore, the question arises whether the discussed solutions are in line with international law. There are no doubts that both pillars of fair trial are not unlimited. For certain reasons, both the openness and the speed of the proceedings may be limited or extended.[26] There is therefore a certain feedback between both foundations: withdrawing from a public hearing is possible when the court is able to adjudicate on the basis of the materials already presented by the parties or collected in writing. In this way, it guarantees that the case is resolved without undue delay, reducing its public examination to a minimum. On the other hand, hearing a case should be postponed if it is necessary to secure the attendance of parties or third persons (including the public) or the complexity of the problem analysed in the court case suggests the need for public hearing.[27] From this perspective, limiting the scope of public hearing of the case is to accelerate court proceedings; on the other hand -by referring to the need to ensure the public hearing of the case, it is possible to slow down the course of the proceedings.

However, it should be noted that the discussed re-balance of the right to a fair trial cannot be arbitrary. This should take place only when, without any response, there is a risk of violating the right to a fair trial and the proposed amendment reduces or eliminates the resulting threat. Moreover, it does not violate other aspects of the right to a fair trial, or at the same time compensates for the violations that have arisen.[28] Otherwise, the introduction of the solutions discussed must be considered contrary to international law.

It should therefore be considered whether the measures taken shift the centre of gravity of the right to a fair trial and counterbalance the limitations caused by the pandemic. As regards the measures of suspension, it should be stated that their aim is to create a situation in which - the examination of the case is suspended until the parties can exercise their conventional entitlement to participate in the proceedings. The measures of transformation - by limiting the openness of procedures - aim to settle matters without undue delay. At the same time, the party does not lose the right to be heard: they can still express their position in writing or participate in a remote session, which, in the assessment of the judicature and doctrine, meets the criteria of being heard.[29] In this approach, both groups of measures should be considered generally admissible under international law.

- 79/80 -

IV. Fair Trial after COVID-19 Pandemic: Possible Paths

How will the pandemic affect the right to a fair trial? In this context, it should be noted that the law should be a living creation, reacting to changes in the socio-economic situation, the level of technological development and, consequently, the needs of individuals. Moreover, the specific shape of the regulations influences the legal environment of court proceedings, and shapes or modifies the practical rules of legal transactions and the awareness of individuals. The functioning of solutions modifying the existing process regulations for over two years may therefore have a permanent impact on the shape of procedural regulations. It therefore seems that three scenarios are possible in the post-pandemic era.

1. Extra Measures as 'New Order' Measures

First, it is possible to assume that the measures adopted in the pandemic constitute 'new order solutions'. After COVID-19 pandemic, states should consider whether some of measures introduced during it may ensure the openness and reasonable time of hearing a case with the balance of some additional solutions (e.g. digitalisation of court papers, online hearings, written procedures instead of oral hearings). In this approach, the extra measures adopted in the course of the pandemic will simply become part of the procedural law system, and their use by the courts will be mandatory. There will thus be a kind of reshaping of the right to a fair trial in the direction of increasing the guarantee of the speed of the trial, while at the same time ensuring the active participation of the party through the use of electronic communication technologies.

However, the indicated structure requires two conditions to be met. First, the compliance of the solutions adopted at the national level with international law cannot raise any legal doubts. Therefore, in the event of any doubts as to the legality of the regulations in question, they should not constitute a permanent element of the procedural law system. For instance, referring above to Poland, it should be stated that the issue of the legality of extra measures has already been the subject of several judgements, in which they were considered admissible in the light of the Polish Constitution.[30] However, this admissibility has always been related primarily to the constitutional aspect and the possibility of its application in the context of extraordinary circumstances. So far, however, there is no judicature that would not relate the regulations in question to just the circumstances of the pandemic, but to admissibility as such. In my opinion, such a ruling would be in favour of extra measures. There are no grounds for considering them as violations of the standard of the right to a fair trial.

- 80/81 -

Another important element from this perspective is the positive social assessment of the adopted regulations. This aspect seems to be as important as the issue of legality described above. It seems that, if the hitherto temporary regulations are deemed excessively restrictive of the right to a fair trial, damage may be caused to the foundations of a democratic state ruled by law. Hence, in my opinion, extending the scope of the discussed regulations to the time after the pandemic requires an analysis of society's assessments as to the functioning of extra measures.

2. Extra Measures as Emergency Measures

The second possible path includes the use of extra measures, but only as solutions functioning in the event of an emergency situation. The trial would therefore take place according to procedural rules similar to those from before the pandemic, considered to be the most fully for implementing the right to a fair trial. A kind of re-balance would only take place in the event of an emergency need that would make it impossible to ensure a fair trial in these emergency conditions. Therefore, anti-COVID solutions remain in force, but only in the event of special situations, in which ensuring the active participation of the party or effectiveness and speed according to traditional rules may be impossible or highly difficult.

Such a solution seems undoubtedly acceptable, but the question arises as to what extent the legal solutions provided for the duration of a pandemic can prove successful in the context of other catastrophes or natural disasters. The specificity of the COVID-19 pandemic included the need to limit direct contact between people, which forced the necessity to move to a larger scale of electronic communication than in the previous order. In the case of natural disasters other than an infectious virus epidemic (e.g. flood, hurricane, fire), these solutions may turn out to be ineffective or insufficient (e.g. due to the inability to establish an Internet connection because of damage to optical fibres or a lack of electricity). It therefore seems that basing the current extra measures structure as that in the event of any future special circumstances seems pointless and potentially ineffective.

3. Extra Measures as 'Nearby' Measures

The third path involves leaving extra measures in legal systems as ordinary instruments ensuring a fair trial next to temporary solutions, while establishing the discretionary power of the judge in choosing the instruments necessary to apply in a given case. Thus, in a case where, for example, a party does not request a direct hearing at a court session, it would be possible to organise a remote hearing, or possibly one in camera, in order to ensure quick settlement of the case. On the other hand, in a case where a party expressly requests a hearing, the court could be bound by such a request, unless it found that it would only be aimed at unduly delaying the proceedings.

- 81/82 -

Therefore, the discussed structure is based on the particular court trial, in which the course of the trial depends on the will of the parties and the court. Instruments introduced to legal systems during the COVID-19 pandemic therefore become an additional range of measures that can enable quick examination of the case while ensuring the possible active participation of the party. The discussed solutions, although derived from a special regulation, would in this approach become a part of a traditional process, which however does not mean, of course, that they could not be used in emergency situations.

Leaving the discussed instruments in force would mean that their compliance with both constitutional acts and the provisions of international law regulating the right to a fair trial is beyond doubt, and there is at least partial social consent to their use. It seems that, in the current economic and social situation and in the absence of clear controversies of a legal nature, this solution seems to be the closest to be implemented. Perhaps in the longer term, extra measures would replace measures that guarantee the 'classic' course of a court trial.

V. Conclusions

The concept of the right to a fair trial has been formulated in many different acts of international law. The following documents refer to it in the broadest scope: ECHR, The Recommendation R (2004) 20 on judicial review, The Charter of Fundamental Rights of The European Union and The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. On the basis of the above-mentioned regulations, the right to a fair trial is uniformly understood as the right to a public hearing of a case without undue delay by an independent tribunal established by law. These indications also apply to the administrative judiciary.

In connection with the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, the first two aspects of the right to a fair trial are at risk of violation. The measures adopted to counteract this risk led to the suspension of court proceedings or limited their openness. For this reason, they can be divided into two groups: measures of suspension and measures of transformation. The legal assessment of the admissibility of such solutions is a complex issue and must always be related to a specific legal solution. Generally speaking, it could be said that the modification of the course of court proceedings in connection with the pandemic was necessary, and the measures adopted were acceptable if they served to strengthen certain aspects of the right to a fair trial.

The research question posed in the introduction concerned whether the right to a fair trial currently has a different meaning or scope than before the outbreak of the pandemic. In my opinion the conceptual scope of the right to a fair trial has not changed. It is still based on the openness of the proceedings and reasonable time of adjudicating the court case, although a balance between them can be maintained by specific or 'extra' legal instruments. According to the second research question - what normative shape should be given to right to a fair trial after the end of the COVID-19 pandemic - it has to be noted that those

- 82/83 -

'extra' measures shall be used to guarantee the reasonable time of adjudicating by courts and to maintain (or even widen) the openness of the proceedings. That applies to some of 'extra' measures of transformation (hearings in camera, written procedures and online hearings). Similarly, some of the detention measures may remain in the law as emergency measures. This applies in particular to the suspension of time limits and access to court buildings. Due to their restrictive nature, their retention in the legal system depends on their proportionality and their exceptional nature. ■

NOTES

[1] Christoph Grabenwarter, 'Fundamental Judicial and Procedural Rights' in Dirk Ehlers (ed), European Fundamental Rights and Freedoms (de Gruyter Recht 2007, Berlin) 152. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110971965.151

[2] See Art. 10 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

[3] Andreas Zimmermann, 'The Right to a Fair Trial in Situations of Emergency and the Question of Emergency Courts' in David Weissbrodt, Rüdiger Wolfrum (eds), The Right to a Fair Trial (Springer 1998, Berlin) 747.

[4] Angelo Jr Golia, Laura Hering, C. Moser, T. Sparks, 'Constitutions and Contagion. European Constitutional Systems and the COVID-19 Pandemic' MPIL Research Paper Series (2020 No 42) 1, 8. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3727240; Edward P. Richards, 'A Historical Review of The State Police Powers and Their Relevance to the COVID-19 Pandemic of 2020' in Stephen Dycus, Eugene R. Fidell (eds), COVID-19: The Legal Challenges (Carolina Academic Press 2021, Durham) 93-118; Robert Knox, Ntina Tzouvala, 'International Law of State Responsibility and COVID-19 and Ideology Critique' (2021) Australian Yearbook Of Law 105-121. https://doi.org/10.1163/26660229-03901009; Upendra Baxi, 'International Law and Covid-19 Jurisprudence' in Werner Gephart (ed), In the realm of Corona Normatives. A Momentary Snapshot of a Dynamic Discourse (Kolestermann 2020, Frankfurt am Main) 179. https://doi.org/10.5771/9783465145318-179; Matthias C. Kettemann, Konrad Lachmayer, Pandemocracy in Europe. Power, Parliaments and People in Times of COVID-19 (Bloomsbury Publishing Oxford 2022, London) 9-346. https://doi.org/10.5040/9781509946396

[5] See Matthias Lehmann, 'Legal Systems Reactions to Covid-19: Global Patterns and Cultural Varieties' in Werner Gephart (ed), In the realm of Corona Normatives. A Momentary Snapshot of a Dynamic Discourse, (Klostermann 2020, Frankfurt am Main) 183-193. https://doi.org/10.5771/9783465145318-183

[6] Klaus Rennert, 'Sądownictwo w czasie pandemii koronawirusa' (2021) (3) Ruch Prawniczy, Ekonomiczny i Socjologiczny 7, 9. https://doi.org/10.14746/rpeis.2021.83.3.1

[7] See <https://www.echr.coe.int/documents/convention_eng.pdf> accessed 31 August 2022.

[8] See <https://rm.coe.int/09000016805db3f4> accessed 25 August 2022.

[9] OJ EU C 83, 30.03.2010, 389.

[10] For more see Christian Calliess, 'The Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union' in Dirk Ehlers (ed), European Fundamental Rights and Freedoms (de Gruyter Recht 2007, Berlin) 518-540. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110971965.518; Tobias Lock, Denis Martin, 'Right to an effective remedy and to a fair trial' in Manuel Kellerbauer, Marcus Klamert, Jonathan Tomkin (eds), The EU Treaties and the Charter of Fundamental Rights - A Commentary (OUP 2019) 2222-2225; Tobias Lock, 'Scope and Interpretation of Rights and Principles' in Manuel Kellerbauer, Marcus Klamert, Jonathan Tomkin, The EU Treaties and the Charter of Fundamental Rights - A Commentary (OUP 2019) 2255; Stanislaw Adam Paruch, 'Koegzysentacja systemów ochrony praw człowieka Rady Europy oraz Unii Europejskiej' in Jerzy Jaskiernia, Kamil Spryszak (eds), Regionalne systemy ochrony praw człowieka 70 lat po proklamowaniu Powszechnej Deklaracji Praw Człowieka. Osiągnięcia -bariery - nowe wyzwania i rozwiązania (Wydawnictwo Adam Marszałek 2019, Toruń) 14.

[11] See <https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/international-covenant-civil-and-political-rights> accessed 31 August 2022.

[12] Amal Clooney, Philippa Webb (eds), The Right to a Fair Trial under Article 14 of the ICCP (OUP 2021) 5. https://doi.org/10.1093/law/9780192897923.001.0001; Michał Kowalski, Prawo do sądu administracyjnego. Standard międzynarodowy i konstytucyjny oraz jego realizacja (Wolters Kluwer 2019, Warszawa) 31-50.

[13] Piero Leanza, Ondrej Pridal, The Right to a Fair Trial. Article 6 of the European Convention of Human Rights (Kluwer Law International 2014, Alphen aan den Rijn) 36-42; Christoph Grabenwarter, European Convention of Human Rights. Commentary (Hart Publishing 2014) 102. https://doi.org/10.5771/9783845258942_1; Grabenwarter (n 1) 154; Andrzej Pagiela, 'Zasada "fair trial" w orzecznictwie Europejskiego Trybunalu Praw Człowieka' (2003) (2) Ruch Prawniczy, Ekonomiczny i Socjologiczny 125, 127; Guide to Article 6 of the European Convention of Human Rights: Right to a fair trial (civil limb) (Council of Europe 2020, Strasbourg) 12; Michał Kowalski, Prawo do sądu administracyjnego. Standard międzynarodowy i konstytucyjny oraz jego realizacja (Wolters Kluwer 2019, Warszawa) 31-50; Aldo and Jean-Baptiste Zanatta v. France, no 38042/97 (ECtHR, 28 March 2000), § 22-26; Allan Jacobsson v. Sweden (No 1); no 10842/84 (ECtHR 25 October 1989), § 72-74, Skärby v. Sweden, no 12258/86 (ECtHR, 28 June 1990), § 26-30; Tre Traktörer Aktiebolag v. Sweden, no 10873/84 (ECtHR, 7 July 1989), § 43-44.

[14] Ferazzini v. Italy, no 44759/98 (ECtHR, 12 July 2001), § 25; Emesa Sugar N.V. v. Netherlands (decision), App no 62023/00 (ECtHR, 13 January 2005); Maaouia v. France, no 39652/98 (ECtHR, 5 October 2000); PierreBloch v. France, no 24194/94 (ECtHR, 21 October 1997), § 50 - for more see Guide to Article 6 of the European Convention of Human Rights: Right to a fair trial (civil limb) (Council of Europe, Strasbourg 2020) 18-20; Grabenwarter (n 13) 102.

[15] Diennet v. France, no 18160/91 (ECtHR, 26 September 1995), § 33; Martinie v. France, no 58675/00 (ECtHR, 12 April 2006), § 39; Fazliyski v. Bulgaria, no 40908/05 (ECtHR, 16 April 2013), § 69, Andrzej Paduch, 'The Right to a Fair Trial Under Article 6 ECHR during the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Case of the Polish Administrative Judiciary System' (2021) 2 (19) Central European Public Administration Review 11.

[16] Grabenwarter (n 1) 15; Grabenwarter (n 13) 147; Leanza, Pridal (n 13) 109.

[17] Fredin v. Sweden (No. 2), no 18928/91 (ECtHR, 23 February 1994), §§ 21-22; Allan Jacobsson v. Sweden (No. 2), no 18928/91 (ECtHR, 19 February 1998), § 46; Göc v. Turkey, no 36590/97 (ECtHR, 11 July 2002), § 47; Paduch (n 15) 11.

[18] Beaumartin v France, no 15287/89 (ECtHR, 24 November 1994), § 33, Andrzej Paduch, 'Supervision over a court as a tool to protect the right to have a case heard within a reasonable time' in Wojciech Piątek (ed), Supervision over courts and judges. Insights into Selected Legal Systems (Peter Lang 2021, Berlin) 152; Paduch (n 15) 10; Grabenwarter (n 13) 141; Grabenwarter (n 1) 158, Beaumartin v. France, no 15287/89 (ECtHR, 24 November 1994), § 33.

[19] Leanza, Pridal, (n 13) 141; Paduch (n 18) 153.

[20] Zhaohui Su, 'Rigorous Policy-Making Amid COVID-19 and Beyond: Literature Review and Critical Insights' (2021) 18 (23) International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 1-17. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182312447; Guangyu Lu, Oliver Razum, Albrecht Jahn, Yuying Zhang, Brett Sutton, Devi Sridhar, Koya Ariyoshi, Lorenz von Seidlein, Olaf Müller, 'COVID-19 in Germany and China: mitigation versus elimination strategy' (2021) 14 Global Health Action 1-11. https://doi.org/10.1080/16549716.2021.1875601; Henrik Wenander, 'Sweden: Non-binding Rules against the Pandemic - Formalism, Pragmatism and Some Legal Realism' (2021) (1) European Journal of Risk Regulation 127-142. https://doi.org/10.1017/err.2021.2; Domenico Piers De Martino, Katharina Plavec, 'Has COVID-19 Unlocked Digital Justice? Answers from the World of International Arbitration' (2021) 6 (1) Cambridge Law Review 45-59.

[21] Shaden A. M. Khalifa, Briksam S. Mohamed, Mohamed H. Elashal, Ming Du, Zhiming Guo, Chao Zhao, Syed Ghulam Musharraf, Mohammad H. Boskabady, Haged H. R. El-Seedi, Thomas Efferth, and Hesham R. ElSeedi, 'Comprehensive Overview on Multiple Strategies Fighting COVID-19' (2020) (17) International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 1-13. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17165813

[22] Journal of Laws of 2020, item 374.

[23] For more see Paduch (n 15) 13-17.

[24] The functioning of courts in the Covid-19 pandemic (Organisation for Security and Co-operation in Europe 2020, <https://www.osce.org/files/f/documents/5/5/469170.pdf> accessed 22 October 2022) 9; Emmanuel Slautsky, Frédéric Bouhon, Camille Lanssens, Andy Jousten, Xavier Miny, Élise Dermine, Daniel Dumont, Mathilde Franssen, 'Belgium: Legal Response to Covid-10' in Jeff King, Octavio Ferraz (ed), The Oxford Compendium of National Legal Responses to Covid-19 (Oxford University Press 2022) 10; Eirik Holmeyvik, Benedikte Moltumyr Hegberg, Christoffer Conrad Eriksen, 'Norway: Legal Response to Covid-19' in Jeff King, Octavio Ferraz (eds), The Oxford Compendium of National Legal Responses to Covid-19 (Oxford University Press 2022) 8. https://doi.org/10.1093/law-occ19/e3.013.3; Paduch (n 15) 14.

[25] The Functioning of Courts In The COVID-19 Pandemic (Organisation for Security and Co-operation in Europe 2020, <https://www.osce.org/files/f/documents/5/5/469170.pdf> accessed 22 October 2022, 9; Anne Sanders, 'Video Hearings in Europe Before During and After the COVID19 Pandemic" [(2020) 2 (12) International Journal For Court Administration, <https://www.iacajournal.org/articles/10.36745/ijca.379/> accessed 22 October 2022] 8. https://doi.org/10.36745/ijca.379; Holmøyvik, Høgberg, Eriksen (n 24) 9; Paduch (n 15) 15.

[26] Miller v. Sweden, no 55853/00 (ECtHR, 8 February 2005), § 30; Allan Jacobsson v. Sweden (No. 2), no 18928/91 (ECtHR, 19 February 1998), § 48-49; Valová et al. v. Slovakia, no 44925/98 (ECtHR, 1 June 2004), § 6568, Döry v. Sweden, no 28394/95 (ECtHR, 12 November 2002), § 37; Saccoccia v. Austria, no 69917/01), 18 December 2008, § 73; Grabenwarter (n 13) 156; Leanza, Pridal (n 13) 110; Paduch (n 15) 11, Hadobás v. Hungary, no 3686/20 (ECtHR, 10 December 2020), § 6; Comingersoll S.A. v. Portugal, no 35382/97 (ECtHR, 6 April 2000), § 19; Keaney v. Ireland, no 72060/17 (ECtHR, 30 April 2020), § 85, 89, 90; König v. Germany, no 6232/73 (ECtHR, 28 June 1978), § 98; Leanza, Pridal (n 13) 145-150; Pagiela (n 13) 125, 135-136.

[27] Grabenwarter (n 13) 142-143.

[28] For more Paduch (n 15) 19-20.

[29] Leanza, Pridal (n 13) 196 and cited there Pashayev vs. Azerbaijan, no 36084/06, 28.02.2012.

[30] Judgements of Supreme Administrative Court: 24.11.2020, II OSK 1305/18, 30.11.2020, II OPS 6/19, 26.04.2021, I OSK 2870/20, 11.05.2021, II OSK 2179/18, 15.07.2021, III OSK 3743/21. For more see Andrzej Paduch, 'Skierowanie sprawy sądowoadministracyjnej na posiedzenie niejawne na podstawie przepisów ustawy antycovidowej a prawo do jawnego procesu. Glosa do wyroku NSA z dnia 26 kwietnia 2021 r., I OSK 2870/20' (2022) (1) Orzecznictwo Sądów Polskich 156-176.

Lábjegyzetek:

[1] The author is Assistant professor, Department of Administrative and Administrative Judicial Procedure, Faculty of Law and Administration, Adam Mickiewicz University, Poznan, Poland.