dr. Kristóf Benedek Fekete[1]: A Comparative Study of Court Administration in Europe, with special regard to Germany, Finland and Hungary* (JURA, 2025/1., 23-52. o.)

I. Introduction

The most pressing dilemma in the comparative study of court administration in Europe is the narrowing and definition of the enormous data pool. The question is, therefore, whether the study should remain within the confines of continental legal systems or open to solutions found in Common Law or Anglo-Saxon legal systems. In this regard, the comparing of certain legal institutions is most effective when the study group is in the same period as the institution that is the main subject of the research and shares many similarities with it. Thus, the issue of court administration can be examined in a narrower context, and we can obtain results that can be evaluated.

Therefore, the research program's main objective is to compare and evaluate specific state solutions in court administration as outlined above in light of Hungarian regulations, considering domestic and international trends (see, for example, the rule of law criteria or the EU Justice Scoreboard). This examination is justified and timely because transitioning to specific solutions is a recurring issue in some countries (e.g., moving away from ministerial administration in Germany). However, it is also worth mentioning the evaluation of actual experiences with change (e.g., Finland's recent judicial administration reform). Since each solution places the regulatory emphasis differently, exploring how the various court administration systems work is interesting: are there any "good" models worth considering, or are there any "cautionary" experiences that call for caution?

The study relies essentially on qualitative methods in terms of methodology. The analysis is mainly based on interpreting and analyzing relevant legal documents using known interpretative techniques and exploring contexts and trends.

- 23/24 -

II. Comparison bases

Central administration of courts essentially means ensuring that the judiciary has the human and material resources necessary to administer justice, which can be interpreted in several ways. Based on the latest literature[1] and supplemented by additional information, this study divides the judicial administrative tasks of individual states into nine groups or dimensions, analyzes them (through more than 60 competencies), evaluates the role of the supreme court(s) in each state, and reviews their relationship with the judicial administration solutions implemented in the states examined. However, before doing so, it is necessary in each case to briefly review the judicial system of the state examined and its central judicial administration institution(s).

III. Some European solutions for central administration of courts

1. The German court system and its ministerial court administration

Due to Germany's federal structure, judicial power is exercised by federal and state courts, supplemented by the Federal Constitutional Court.[2] Judicial functions are therefore performed by the federal courts and the courts of the 16 federal states, with the Federal Constitutional Court also forming part of the judicial system, as it not only performs tasks of a normative review nature but also issues decisions that constitute effective legal remedies. Hence, the Federal Constitutional Court - alongside the federal supreme courts - also functions as the final court of appeal.[3] Within each state, there are Local, Regional, and Higher Regional Courts,[4] meaning that, together with the federal level, Germany has a fourtier court system.[5] There are five supreme courts at the federal level, consisting of the Federal Court of Justice, which has general jurisdiction, and four specialized supreme courts, the Federal Administrative Court, the Federal Fiscal Court, the Federal Labour Court and the Federal Social Court.[6] These may be supplemented - as their establishment is optional - by other federal courts dealing with industrial property rights, military criminal matters and disciplinary matters concerning persons performing public service.[7]

The judicial administration is carried out at the federal and state levels, which aligns with the logic of the GG. At the federal level, the administration of courts is generally the responsibility of the Federal Minister of Justice, who also supervises the Federal Court of Justice, the Federal Administrative Court and the Federal Fiscal Court. However, due to their specific nature, the Federal Labour Court and the Federal Social Court are administered by the Federal Ministry of Social Affairs and Labour.[8] In the case of state courts, they are typically administered by the ministers of justice of the individual state governments, over whom the federal ministries and federal courts have no jurisdiction.[9]

- 24/25 -

The German court administration can be interpreted at both the federal and state level, but also at the ordinary and specialized court levels, meaning that the administration of German courts is four-tiered, as it simultaneously exhibits federal, state, ordinary, and specialized elements. Nevertheless, since the introduction of ministerial administration, there has been a recurring dilemma regarding the shift towards judicial self-administration, which promises more effective administration.[10] However, the introduction of non-ministerial court administration alone does not guarantee more efficient administration of justice,[11] especially since Germany has a stable democratic political system and legal culture, which in itself can serve as a guarantee - given the traditions that have been established - for the development of a judiciary that is committed to complying exclusively with the law and a ministerial administration that is incapable of self-restraint.[12]

2. The Finnish court system and its mixed court administration

According to Section 3(3) of the Constitution of Finland (hereinafter: the Finnish Constitution), judicial power is exercised by independent courts, together with the Supreme Court, the Court of Appeal, and the Supreme Administrative Court as the highest courts.[13] Judicial power is thus exercised by the Supreme Court, six courts of appeal and 27 district courts as courts of general jurisdiction, and by the Supreme Administrative Court and eight regional administrative courts of appeal as courts with jurisdiction in administrative matters.[14] These are joined by the High Court of Impeachment, which adjudicates in cases involving members of the government, the chief justice, members of parliament, and members of the Supreme Court or the Supreme Administrative Court for violations of the law committed in the course of their duties. Under the Finnish Constitution, there are also special courts, the detailed rules of which are laid down by law.[15] In Finland, as in other Scandinavian countries, there is no constitutional court, but courts and other authorities are required to interpret legislation by the Finnish Constitution and to respect the fundamental rights enshrined therein.[16] Therefore, if the application of the law in a case before a court would be manifestly contrary to the Constitution, the court shall give priority to the provisions of the Constitution.[17]

Although the court system and the associated procedural codes followed the Swedish model after Finland gained independence in 1917,[18] the administration of the courts took a different path from that of the "mother country".[19] The previous purely ministerial system of administration of the Finnish courts was replaced on January 1, 2020, by the National Courts Administration (hereinafter: NCA), an independent central agency serving the entire judiciary, which is part of the administrative branch of the Ministry of Justice.[20] The agency's fundamental task - in order to ensure the quality of judgments - is to provide the courts with the neces-

- 25/26 -

sary personnel and material resources, with particular attention to adequate (financial) resources and facilities.[21] The highest decision-making powers of the NCA are exercised by the Board of Directors, while the day-to-day work of the agency is managed by the Director General.[22] The eight members of the Board of Directors are appointed by the government for a term of five years, based on recommendations from the Ministry of Justice, with no legal restrictions on reappointment. Six members are judges from different levels of the judiciary, one member represents other court staff, and one additional member (who is not a judge) is appointed based on of expertise in the management of special public administration.[23] The law narrows the composition of the Board of Directors by stipulating that one of the six judges must be the president of an appellate or district court and one must be the president of an administrative or special court.[24]

The law lays down strict rules for the appointment of members of the Board of Directors, according to which the highest judicial body appoints one member and one alternate member from among its staff, following an expression-of-interest procedure (i.e., consultation with labor organizations), the presidents of the courts of appeal and district courts and the presidents of the administrative and special courts nominate one member and one alternate member for the positions of president of the Administrative Court and the Special Court. After the consultation, the aforementioned court presidents nominate the representative member and alternate member for the other court staff. All nominations for court presidents must be "doubled", i.e., twice as many members and alternate members must be nominated for vacant positions on the board of directors as the number of candidates selected for the position. The rationale behind this rule is to enable the government to influence the composition of the Board of Directors (e.g., in terms of gender or geographical location).[25] At the same time, the chair and vice-chair are elected by the members from among themselves.[26] The NCA consists of three units responsible for finance, various developments, and administration.[27] However, the Supreme Court and the Supreme Administrative Court are self-governing in terms of their operations. It can, therefore, be concluded that the Finnish court administration has a three-tier structure: state, ordinary, and specialized supreme court administration.

3. The Hungarian court system and its sui generis court administration

In Hungary, only courts exercise judicial power;[28] the Constitutional Court of Hungary is the supreme body for the protection of the Fundamental Law.[29] The Fundamental Law, therefore, assigns judicial power exclusively to the courts, in contrast to the fundamental laws and constitutions of other countries.[30] Consequently, judicial activities are carried out by the court system on four levels: the Curia, which has national jurisdiction and is the highest court in all matters, is supported by five courts of appeal, 20 regional courts

- 26/27 -

with territorial jurisdiction and 114 district courts with local jurisdiction, some of which are located in cities and others in the districts of the capital.[31]

Since January 1, 2012, the administration of the courts and its central tasks have been performed by the president of the National Office for the Judiciary (hereinafter: NOJ), who is elected for a nine-year term by a two-thirds majority of the National Assembly of Hungary on the recommendation of the president of the republic[32] from among judges appointed for an indefinite term who have at least five years of judicial service, including at least two years in a judicial management position. This position may only be held once, which is quite appropriate.[33]

The only exception is the Curia, which has its own self-governing body. It can be concluded that the domestic court administration is two-tiered: it can be interpreted at the state and supreme court levels. This new sui generis model of judicial administration has now separated the tasks and powers of the former President of the Supreme Court and the President of the National Council of Justice (hereinafter: NCJ), which, in contrast to collegial decision-making, will be able to decide on almost all matters previously within the competence of the NJC.[34] The wide range of powers vested in the President of the NOJ is set out in the Court Organisation Act. In order to ensure effective and efficient administration, he or she has powers and responsibilities covering almost all areas of the functioning of the courts.[35] In contrast, the main task of the President of the Curia is to ensure the uniformity and professional quality of judicial decisions, which is a specific legal policy expectation arising from the Fundamental Law and the Court Organisation Act.[36]

IV. Dimensions of certain European solutions of central court administration

1. Regulatory dimension

The main rules governing the establishment, abolition, merger, division, and jurisdiction of courts are laid down in the GG (see Articles 95-96 and 99) and in the fundamental laws of the federal states, as well as in the relevant federal (see DRiG, GVG) and state laws. These powers are exercised by the federal and state parliaments, with judges not directly involved in the subsequent adoption of changes to these regulatory powers.

The Finnish Constitution also provides a constitutional framework for the same powers, with the restriction that it stipulates that temporary courts may not be established.[37] Since parliaments exercise regulatory powers and judges do not participate directly in these processes, the NCA plays a significant role in shaping legislation, measures, and developments affecting the courts through the initiatives it submits to the government within the scope of its activities.[38] In Hungary, the Fundamental Law assigns the powers in question to the level of cardinal laws,[39] as regulated by Act CLXXXIV of 2010,[40] In other words, all of these fall within

- 27/28 -

the competence of the Hungarian parliament, with the proviso that judges may comment directly and indirectly on laws and draft legislation relating to the administration of justice. On the one hand, individual judges may, therefore, directly express their opinions on draft legislation relating to the administration of justice (typically acts) in particular, as their freedom of expression is not restricted in this area. On the other hand, according to Section 76(1)(e) of the Court Organisation Act., the President of the NOJ, in his general central administrative capacity, obtains and summarizes the opinions of the courts through the NOJ and, except municipal regulations, issues opinions on draft legislation affecting the courts. In this context, the President of the NOJ may also submit legislative proposals concerning the courts to the body competent to initiate legislation and participate as a guest in the meetings of the committees of the National Assembly of Hungary when agenda items directly concerning the courts are discussed.[41]

2. Administrative dimension

In contrast to the Finnish Constitution and the Fundamental Law, Article 101(1) of the GG unambiguously establishes one of the most important fundamental principles of fair trial, namely the right to a lawful judge, i.e. a constitutional guarantee against arbitrary case allocation ("directed" case assignment).[42] According to the Federal Constitutional Court, "[t]he guarantee of a lawful judge is a specific expression of the general requirement of objectivity under the rule of law and ensures that the competence of the judge is generally predetermined and cannot be assigned ad hoc or ad personam. In this way, the second sentence of Article 101(1) of the GG protects the adjudicating bodies from manipulative influence."[43] In this context, it should be stressed that this right has historically been linked to the prohibition of the establishment of extraordinary courts, with the aim of preventing the principle from being circumvented and thus deprived of its practical application.[44] Therefore, it is necessary to determine in advance the order of case allocation, which in Germany is done in different ways, but in a so-called "blind" system,[45] according to a case allocation plan, i.e. court cases are assigned to individual judges or panels of judges according to a type of automatism.[46] The so-called presidium (Präsidium) in each court, or the president and elected members of the court, are responsible for setting up the judicial panels and for drawing up the annual case allocation plan, which predetermines the assignment of cases to individual judges or panels.[47] Deviation from this is only possible in a pre-defined manner and case, based on a substitution order.[48] The Finnish and Hungarian models only address the issue of case allocation at the statutory level.[49] Although case allocation is not (entirely) automatic, strict rules govern the assignment of cases to judges and courts in both models: in Finland, a case assigned to a specific judge may only be reassigned (transferred) against the will of the judge concerned if there are serious reasons for doing so, such

- 28/29 -

as the judge's illness, the delay in the case, the judge's workload or other relevant factors.[50] Although case allocation is not (entirely) automatic, strict rules govern the assignment of cases to judges and courts in both models: on the one hand, in Finland, a case assigned to a specific judge may only be reassigned (transferred) against the will of the judge concerned if there are serious reasons for doing so, such as the judge's illness, the delay in the case, the judge's workload or other relevant factors. On the other hand, in Hungary, the assignment of a judge to a case can only be done objectively by applying pre-set, general rules, and only then can we talk about a lawful judge, meaning "[a] judge who works in a court with pre-set competence and jurisdiction, appointed according to a pre-set case allocation system."[51] It should be emphasizing that, as an independent criterion of fair trial, the right to a lawful judge requires the legislator not only to establish a predetermined order of allocation, but also to refrain from enacting laws that would remove cases already pending from the jurisdiction of the lawful judge.[52] Therefore, the public seeking justice must know which court and which judge is competent to hear a given case.[53] For instance, the previous practice of transferring cases by the president of the NOJ was rightly deemed unconstitutional.[54] In this context, it is also worth highlighting the modification of the case allocation system and deviations from the case allocation rules. The former refers to changes to the case allocation system itself, which may be made in the interests of the service or for important reasons affecting the functioning of the court.[55] The latter means that cases are assigned differently from the published, valid case allocation rules. This may occur in cases regulated by procedural law (the most typical example being the disqualification of a judge) or through administrative channels (based on the decision of a single administrator) for important reasons affecting the court's functioning (e.g., the illness of a judge).[56]

The number of judges performing judicial duties in a court in Germany, as well as the composition of the panels in which they sit, is determined by the relevant federal and state regulations, as well as the caseload and the specific budget. The total number of administrative staff and legal assistants also depends on the above factors, which are determined by the state government (typically the Ministry of Justice) in conjunction with the above.[57] In Finland, the NCA - unless it falls within the remit of the Ministry of Justice -is responsible for the administration of court premises and decides on the creation, abolition and transfer of posts in the courts, as well as on internal recruitment measures,[58] and deals with issues relating to the employment of court staff, unless these matters fall within the competence of a court or authority.[59] Furthermore, individual courts (management groups) are responsible for,[60] among other things, significant matters concerning the leadership, administration, finances, operation, and personnel of the court, as well as their development.[61] Accordingly, the number of judges and the composition of the ju-

- 29/30 -

dicial panel at a given court (including court staff assigned to the court) depend mainly on the budget, on the one hand, and on the caseload and other professional considerations relating to the administration of justice, on the other. One of the main tasks of the new administrative model launched in Hungary in 2012 was to eliminate disparities in the workload of individual judges and to ensure fairness in the long term, which was essentially aimed at improving the efficiency of judgments. Within this framework, judicial positions were redistributed according to new principles and the distribution of cases was also adjusted.[62] In this regard, the President of the NOJ shall, with the agreement of the National Judicial Council (hereinafter: NJC), which supervises it, regarding on the average national workload indicators for proceedings pending before the courts, define the number of judiciary and judicial staff of courts.[63] The President of the NOJ, with agreement with the NJC, also determines the data sheets and methods for measuring the workload of judges and sets the average national workload for litigation and non-litigation proceedings at each court level and for each type of case.[64] All things considered, it is essentially the president of the NOJ who, with the agreement of the NJC, decides on the total number of judges appointed to a given court and other judicial personnel assigned to it, but the number and composition of judicial panels is not his or her responsibility, but falls within the remit of the plenary session of judges.

Lastly, if we look at how courts are evaluated in different countries, we can say the following. In Germany, due to the separation of powers, no state body evaluates the quality of court decisions, meaning that individual judgments can only be "assessed" or "reviewed" through appeals. The Federal Constitutional Court and the constitutional courts of the federal states play an indispensable role in evaluating the courts and supervising the judicial system since the so-called "real" constitutional complaint is an effective instrument in a specific context. From a financial point of view, it can be said that the state government of the day decides on the budget for the administration of justice. Adequate resources and staffing are essential for a well-functioning justice system. Thus, at the federal and state levels, the budget for the justice system is determined in the budget law, with the involvement of the Minister of Justice.[65] In Finland, the Ministry of Justice is responsible for evaluating Finnish courts, as this ministry is responsible for the administration of the judicial system, including the overall evaluation of the efficiency and performance of courts.[66] Of course, the NCA also monitors the performance of the courts and prepares studies and evaluations in this regard.[67] All evaluations aim is to ensure the independence and efficiency of the courts and to improve the quality of legal services, i.e. the overall development of the courts. In this context, the NCA has a key role and responsibility as the agency representing the judicial system in national development and other projects, unless these fall within the remit of a specific court, the government, or another au-

- 30/31 -

thority, and promotes, supports and coordinates development projects affecting the courts and their activities.[68] In this connection, it should be mentioned that the NCA is responsible for the technical and routine central administration of the entire court system and also participates in international cooperation within his sphere of activity.[69] In Hungary, there is no institutionalized method for evaluating courts. A comprehensive picture of the courts' performance can be obtained from the annual reports of the President of the NOJ, which are submitted to the National Assembly of Hungary for approval. In addition, some representatives of the legal profession attempt to evaluate courts in some way (e.g., based on the number of appeals).[70]

3. Personal dimension

The constitutions of the countries examined contain only brief provisions on becoming a judge, typically only symbolic acts (e.g., appointment),[71] with detailed rules laid down in (cardinal) acts.[72] All of the countries examined have a so-called career judiciary, meaning that judges devote their entire lives or a significant part of their lives to the judiciary, and their careers typically begin in a court of first instance.[73]

In selecting judges, the countries examined, as states with Civil Law or Roman-Germanic legal systems, strive to develop a system of judicial selection that focuses on objective, professional criteria.[74] In Germany, the individual federal states are responsible for establishing the system for the initial recruitment and promotion of judges.[75] The competent minister (typically the minister of justice) is responsible for this process,[76] taking into account federal requirements such as general and professional (legal) requirements.[77] If no consensus can be reached on the appointment of individual judges, the decision is referred to a judge selection committees (Richterwahlausschüsse), which operate in half of the federal states[78] and are "dominated" by fellow judges,[79] but their decisions are considered unconstitutional without the consent of the competent (justice) minister.[80] It is clear that the German appointment and selection process is not uniform, but varies from state to state, meaning that judges can be appointed independently by state governments, in accordance with the GG and federal laws.[81] The same applies to judicial promotion, which is quite formal and follows the principle of selecting "the most suitable candidate for the position". In other words, even if the ministry makes a decision, it is not able to "override" the established ranking.[82] In Finland, however, appointments (and preparations for appointments) are the responsibility of the 12-mem-ber Judicial Appointments Board. The Finnish judicial appointment procedure has three stages. First, the Judicial Appointments Board prepares the fill positions and makes a reasoned proposal to the government for appointment to judicial office. The government then submits a draft appointment decision to the President of the Republic, who finally, by the Finnish Constitution, the President of the Republic appoints

- 31/32 -

the persons proposed for judicial office based on the draft decision submitted by the government.[83] Following the public announcement of judicial positions,[84] the Judicial Training Board shall request a reasoned opinion from the court that announced the vacancy, and, in the case of applicants for district judge positions, also from the district court where the position has become vacant, on which of the applicants it considers appropriate to appoint to the position.[85] The board may also obtain additional opinions and statements and hear the candidates and experts. Under the law, candidates must be allowed to express their views on the opinions and statements obtained during the preparation of the appointment.[86] Only after all this can the appointment proposal be made.[87] The Hungarian solution, as a general rule, is also within the judicial system: a person with a law degree (lawyer) begins working as a court clerk at the court following a written and oral exam containing elements regulated by Order 3/2016. (II. 29.), and then start working as a court clerk (at least 3 years of experience). After passing the legal professional examination and the aptitude test, you will be appointed as a court clerk (at least 1 year of experience), and only then can you apply for a vacant judgeship. Therefore, an appointment without prior court experience is not the norm but rather an exception.[88] This is confirmed by the annual reports of the President of the NOJ, as 822 of the 862 new judicial appointments were made within the judicial system, while 40 were made outside it. In other words, more than 95% of all new judicial appointments were made within the system; on the other hand, less than 5% were outside the organization.[89] As a general rule, judicial positions in Hungary are filled through an application process,[90] with job vacancies call for applications by the president of the NOJ.[91] Appointments to and transfers between judicial positions in Hungary are based on the appointment system introduced in 2011, according to which judges are selected through a multi-stage competitive selection process. According to KIM Decree 7/2011 (III. 4.) KIM on the detailed rules for evaluating applications for judicial positions and the points that may be awarded during the ranking process, judges are selected on two levels: one objective and one subjective.

The requirement of "remaining in office" (unremovability) is enshrined in the constitution/fundamental law of all three countries, meaning that, in summary, judges may only be removed from office against their will for reasons specified in (fundamental) law and by the procedures laid down therein (including temporary transfers). The Finnish Constitution and the GG also specifically mention retirement and reorganization in this context.[92] In the absence of a provision in the Fundamental Law, there is greater scope for removal in Hungary than in the other two countries.

In Germany, disciplinary measures against judges are determined by Article 98(2) of the GG, which assigns responsibility for deciding on the consequences of intentional and unintentional law violations to the

- 32/33 -

Federal Constitutional Court and the Federal Parliament (Bundestag). In other cases, disciplinary powers are exercised by the specific judge's superior and by the federal and state service courts by the Federal Disciplinary Act (Bundesdisziplinargesetz, hereinafter: BDG) and the relevant state disciplinary legislation.[93] In Finland, as a general rule, disciplinary proceedings cannot be initiated against a judge for a judgment he or she has rendered,[94] so the most notable measures within the scope of disciplinary law for judges are written warnings and suspension from office. The former is issued by the head of the court where the judge serves if the judge has violated or neglected his or her duties.[95] However, the judge who receives the written warning may appeal against this decision.[96] The latter is no longer made by the president of the court, but by the court within which the judge serves. Of course, the suspended judge may also appeal against the decision. Despite the rigorous selection process, there may be cases in Hungary where judges are unsuitable for judicial office or the profession due to their personality or conduct. This type of unsuitability typically arises at a later stage and can only be remedied through disciplinary proceedings. Under to Section 106(1) of the Judges' Status Act, the president of the court or the person exercising the power of appointment - in the case of judges assigned to the NOJ, exclusively the president of the NOJ[97] - shall initiate proceedings for disciplinary misconduct.[98] There are two types of misconduct: (i) when a judge culpably violates his or her obligations related to his or her service, or (ii) when a judge's lifestyle or conduct violates or jeopardizes the authority of the judicial profession.[99] The former refers to cases laid down in cardinal acts (e.g., procedural or administrative delays[100]), while the latter covers a wide range of situations which, due to their diversity, cannot be exhaustively listed, but which may serve as guidelines for the enforcement of disciplinary law, such as the Code of Ethics for Judges (hereinafter: Code of Ethics),[101] previous decisions of the Ethics Council[102] and domestic service court practice.

In Germany, the judicial performance evaluation is generally a competence of the federal states. Most federal states have, therefore, established criteria catalogs for evaluating judges. These catalogs outline criteria for certain judicial positions (first instance judge, appeal judge, presiding judge, etc.).[103] Judges, who are independent, are responsible for the evaluation in so-called presidential councils (Präsidialräte).[104] The Finnish judicial system includes several quality control elements: firstly, the NCA monitors the performance of courts and prepares studies and evaluations in this regard; secondly, the individual courts themselves monitor and analyze statistics and feedback; thirdly, academic and research institutions prepare studies on the court system, contributing to its continuous evaluation. In contrast, Hungary has the most detailed professional review of judges, which has two practical time frames: one for judges appointed for a fixed term[105] and another for judges appointed for an indefinite term.[106] When examining

- 33/34 -

the issue of professional competence, it can be concluded that judges appointed for a fixed term are subject to a strict selection mechanism, where the subject is more important, i.e. there is greater discretion as to whether a person can be appointed as a judge for an indefinite period or not. In fact, unsuitable persons can be excluded from the judiciary "without restriction" in this category. Later, it will be possible to "remove" judges appointed indefinitely from office in a much more restricted manner, with disciplinary/criminal law institutions playing a prominent role.

Regarding financial bonuses, it can be noted that judges' bonuses in Germany depend on the state governments[107] while in Finland, judges do not receive any bonuses or other benefits whatsoever.[108] In Hungary, on the other hand, there is a strict legal framework providing for jubilee awards after 25, 30, 35, 40, and 45 years of service,[109] and, depending on the appropriations provided in the annual budget of the courts, other benefits may also be granted outside the cafeteria system ("simple" bonuses).[110] The president of the NOJ plays a decisive role in this regard.[111]

Lastly, regarding rules on responsibility, it is generally true that under Article 98(1) and (3) of the GG, federal and state legislatures must regulate the legal status of judges in separate formal laws. This expresses the special legal status of judges, who exercise their judicial functions in personal and actual independence.[112] In addition, judges are individually protected by the traditional principles of public service.[113]

Judges are subject to official supervision, which is regulated by Section 26(1) of the DRiG, but must be organized and administered in such a way that their independence is not impaired by Article 97 of the GG. The basic limits of the criminal liability of judges are laid down in Article 98(2) and (5) of the GG, which sets out the most fundamental rules governing the liability of judges.[114] More detailed provisions are contained in Section 30 of the DRiG and the relevant sections of the German Criminal Code (Strafgesetzbuch, hereinafter: StGB). Under Article 110 of the Finnish Constitution, the Chancellor of Justice or the Ombudsman takes the decision on whether to bring charges against a judge for misconduct in office. The criminal liability of Hungarian judges, which derives from ministerial responsibility and the system of responsibility of public officials but considers the principle of judicial independence, has also been modified.[115] Consequently, in Hungary, only the public prosecutor's office conducts investigations into crimes committed by judges,[116] that the judge, as a person enjoying immunity, may be questioned as a suspect, coercive measures may be used against him or her - except in cases of flagrante delicto - and charges may be brought only after his or her immunity has been suspended.[117]

4. Financial dimension

In Germany, two federal ministries and the state ministries are responsible for the budget of the courts, including their administration, with the Federal

- 34/35 -

Constitutional Court submitting its court budget for approval.[118] The individual ministries generally manage the budget of the courts together with the public prosecutor's office, which means that in most federal states, the budget of the courts cannot be separated from that of the public prosecutor's office.[119] Abstracting the issue, the judiciary and the executive cooperate in preparing the "budget allocated to the courts," but the executive and the legislature decide the official proposal and its adoption. However, the control and evaluation/audit of this budget is in the hands of the judiciary and the executive.[120]

In Finland, the Board of Directors submits proposals to the Ministry of Justice on the appropriations for the operating expenses of the courts and the NCA, the Judicial Appointments Board and the Judicial Training Board, and, in addition to the appropriations allocated directly to specific courts, the same body decides on the distribution of appropriations between individual courts by the approved budget.[121] The Finance Department of the NCA is responsible for preparing the operational and financial plans, expenditure and budget proposals, and supplementary budget proposals for the administration of justice.[122] The Finance Department is also responsible for the financial management of the courts' accounting units unless the relevant decision-making powers fall within the remit of the Ministry of Justice.[123] Judges' salaries are determined by the state budget and are based on experience. As the detailed breakdown of the budget allocated to the courts is not available because the Finnish Parliament allocates a lump sum to the courts in the state budget, the actual "items" can be found in the accounts.[124]

In accordance with their distinguished role in the state, the courts shall have a separate budget chapter in act on central budget of Hungary, with the Curia and, from June 1, 2024, the NJC having separate titles within that chapter.[125] In this regard, the President of the NOJ, acting in his capacity as responsible for matters relating to the budget of the courts, shall prepare a proposal for the budget of the courts and a report on its implementation.[126] A significant change is that, from June 1, 2023, the budget of the NJC will no longer be determined by the president of the NOJ - who otherwise supervises its work - but by the NJC itself, in addition to the chapter on courts in this bud-get.[127] In the case of the Curia, the position of the President of the Curia will continue to be taken into account, as the President of the NOJ must consider requesting and presenting his opinion.[128] It should be emphasized that the financial autonomy of the Hungarian courts in its current form is merely symbolic, not real, as it is ultimately subject to the discretionary power of the ruling (parliamentary) forces.[129]

5. Educational dimension

General legal education in Germany aims to prepare students for the judicial profession, which means that the training places great emphasis on acquiring relevant skills. Unlike in most European countries, young law graduates can be

- 35/36 -

appointed as judges without further training.[130] However, it is widely accepted that (early) "supplementary" training is necessary after appointment in order to perform daily court duties and acquire know-how, for which the federal states have developed separate methods.[131] Since January 1, 2019, continuing education for judges has been organized by the Federal Office of Justice, which is part of the Federal Ministry of Justice and responsible for training legal practitioners (Rechtsprechung) both within Germany and at the European level (e.g., exchange programs). This includes organizing and participating in training programs offered by the German Judicial Academy, the European Judicial Training Network, the Academy of European Law, and the European Patent Office.[132] Among these, the German Judicial Academy plays a special role as the leading institution for (further) training of judges and is therefore responsible for training at the national level. The Academy invites lecturers to Trier and Wustrau to deliver free continuing education courses, mainly in the form of conferences, which, due to their nationwide coverage, contribute significantly to the development and maintenance of legal uniformity in Germany.[133] In addition, individual federal states may introduce compulsory training for young judges. Fundamentally, these fall within the scope of continuing education, but they are limited to the period prior to permanent appointment (hence their mandatory nature), as their purpose is not to maintain and expand professional knowledge and expertise but to enable participants to acquire the basic skills necessary for judicial work. It is important to note that individual performance is not assessed in these training courses; instead, the first 3-5 years following the initial appointment are taken as a basis for determining whether, in the opinion of those responsible, the candidate is sufficiently qualified for permanent appointment[134] and can apply for a vacant position.

The Finnish NCA (more specifically, its training group) is responsible for organizing the training of judges and other court staff,[135] but educational powers are concentrated in the Judicial Training Board, which must cooperate with the NCA and the courts.[136] The Judicial Training Board itself is a ten-member body appointed by the government and composed of a president, a vice-president and eight members, of whom the president, vice-president and four other positions are judges, one position is a prosecutor, one position is a lawyer, one position is held by a university lecturer/researcher and one position is held by a representative of the NCA for a term of five years.[137] The Courts Act (673/2016) also states that judges must maintain and develop their legal knowledge and skills, for which appropriate education and training must be provided.[138] During their term of office, selected and appointed candidates for judges must participate in a continuing education program for judges developed by the Judicial Training Board (minimum 3 years) in accordance with their personal study plans prepared for them at the training location in order to[139] enable them

- 36/37 -

to take independent judicial decisions even in complex and extensive cases.[140] Aside from general training, this body also handles leadership training.[141] So, the Judicial Training Board sets up the exams for these, as well as the structure and content of the training, and decides on the qualifications of each judge.[142]

Similarly to the above, the Hungarian training system also aims to contribute to pursuing high-quality justice within an organized and transparent framework. The operation of the training system (setting guidelines and making decisions) falls within the remit of the President of the NOJ.[143] In accordance with modern requirements, the president of the NOJ primarily provides uniform preliminary and continuing training for judges through an educational center,[144] the Hungarian Academy of Justice (hereinafter: HAJ).[145] The professional content of the training courses is determined by the President of the NOJ in a central training plan prepared by the HAJ Training Department. This department develops the training methods and prepares the annual central training plan [with the participation of a variable number of experts (usually 16-17) appointed by the President of the NOJ[146]], and after its approval, takes steps to ensure its implemen-tation.[147] The central training courses organized by the HAJ based on the Central Education Plan issued annually and approved by the President of the NOJ include compulsory basic professional training related to the judicial career, continuing professional training (mandatory and recommended) for experienced judges and judicial staff with independent signing authority, as well as training related to their position and supporting the functioning of the courts (e.g., leadership training).[148] In terms of implementation, the training courses can typically be divided into three cycles per year, with a wide variety of locations. HAJ delivers the training courses in person and online, in close cooperation with the courts and coordination with local training courses.[149] The main venues for face-to-face training are the HAJ buildings in Budapest and Balatonszemes. There are many forms of education, with panel and individual presentations still popular, but active and experiential learning techniques are gaining ground. In addition, distance learning and web-based learning have recently gained in importance as alternatives to face-to-face lectures, mainly due to the pandemic situation, and are often more cost-effective and timelier than live, classroom-based teaching.[150]

6. Informational dimension

Information and transparency are given high priority in all three countries examined. Accordingly, since 2010, the Federal Ministry of Justice and the Federal Office of Justice in Germany have made selected decisions for the Federal Constitutional Court, the highest federal court, and the Federal Patent Court, which are available freely on the Internet for the legal community. These decisions are contained in a database that is updated daily, where they can be accessed in their entirety, albeit anonymized, and used for indi-

- 37/38 -

vidual decisions.[151] The court administration decides on the publication of court judgments, but less than 1% of court decisions are made public.[152] In Finland, it is also typical to publish decisions that are considered important or precedents in legal matters. In general, summaries of court decisions, particularly those of the Supreme Court, the Court of Appeal, the Supreme Administrative Court, and the administrative courts, are published regularly online in Finnish and are available free of charge.[153] It should be noted that the Supreme Court and the Supreme Administrative Court also publish unofficial English summaries of some of their precedents.[154] In order to ensure adequate transparency, the President of the NOJ is responsible for publishing the Collection of Court Decisions (Bírósági Határozatok Gyűjteménye, hereinafter: BHGY) (Anonymized Decisions Archive),[155] which contains the decisions of the Curia, the courts of appeal and, to a somewhat lesser extent, the regional courts in a free, anonymized[156] and searchable[157] digital format.[158] Although not required by act, numerous district court and former administrative and labor court decisions are also available in the BHGY. Due to its special role, the Curia must also publish its decisions on requests for review, decisions on complaints regarding legal uniformity, decisions on proceedings for legal remedies in the interest of legality, and decisions on the merits of cases and decisions repealing previous decisions, it must also publish its decisions on the merits of review requests. In addition to the decision published by the Curia, the theoretical content of the decision must be indicated, or in the absence thereof, a brief summary and the applicable legal provisions.[159] However, the search engine of the BHGY still leaves something to be desired, as its search engine is overly complicated and difficult to use, making it difficult to search, and only a small portion of the judgments are accessible,[160] even though the decisions of lower courts are just as important, if not more so, to the legal community than those of higher courts.

In Germany, court hearings are generally open to the public under to Section 169(1) of the GVG, but as a general rule, audio and video recordings and the public presentation or publication of their content are not permitted.

However, Section 169(2) of the GVG, taking into account the legitimate interests of the parties concerned, allows the court to authorize audio and video recordings of the trial for scientific and historical purposes if the proceedings are of outstanding historical significance.[161] In contrast, in Finland,[162] and in Hungary, procedural codes regulate when and in what cases it is permissible or prohibited to record proceedings.[163] These cases are set out in detail in the acts and, as a general rule, the decision on whether and how recording may take place is left to the discretion of the judge or panel hearing the case, which may in some cases be subject to the consent of the persons concerned. After comparing the rules, it is clear that the Hungarian system provides the most regulated and, at the same time, the most complete transparency.

- 38/39 -

German judges must declare their personal wealth, but this does not automatically mean that these declarations are made public. They are only disclosed in exceptional cases, such as legal proceedings. The disclosure of judges' political affiliations is at their discretion. Judges may also make their official position on political matters public, but their political opinions must be distinguished from their official (judicial) statements.[164] In contrast, Finnish judges are required to make a declaration of interests, as specified in the laws governing public officials. Under this obligation, people nominated for judicial office must declare their private interests prior to their appointment, i.e., their industrial and commercial activities, business or property ownership, secondary occupations, and any other duties or liabilities that may be relevant to the assessment of their suitability for the position applied.[165] Following this, as a judge, if there is any change, they must immediately make the necessary amendments and corrections and, at the request of the competent authority, provide the relevant information. However, the authority shall keep the content of this declaration confidential.[166] Judges may exercise their political opinions with restraint but may not disclose their political affiliations to preserve their independence and impartiality. In Hungary, to ensure the impartial and unbiased enforcement of fundamental rights and obligations, as well as ensure the integrity of public life and prevent corruption, all judges are required to make a declaration of personal wealth with the content specified in Annex 4 to the Judges' Status Act (including their spouse/partner and children living in the same household), which must be repeated every three years as a general rule,[167] but the employer may, for good reason, require an extraordinary declaration of personal wealth.[168] Judges' personal wealth declarations are not public. Only the person exercising the employer's rights and the NOJ shall ensure that all documents relating to the declaration of assets (including the sealed envelopes containing them) are kept separate from other documents.[169] Given that the declaration of personal wealth is already a prerequisite for judicial appointment and oath-taking in Hungary,[170] the Judges' Status Act quite rightly attaches serious consequences to failure to comply with or breach of this obligation. "[A] judge must be relieved from office if: deliberately refused to file a compulsory declaration of personal wealth, or if the judge has knowingly disclosed false data or information in the statement or withheld important information, including information pertaining to those of his family members who live in the same household, or if the judge has withdrawn his/her declaration of personal wealth or his authorization for processing his personal data."[171] Under Article 26(1) of the Fundamental Law, Hungarian judges may not be members of a political party or engage in political activities. Without going into detail, this also means that they must refrain from political statements in public and exercise their political opinions with the utmost restraint. Although judges are entitled to participate in public events

- 39/40 -

organized within the framework of the law, they must ensure that their participation does not give the impression of political commitment.[172]

In Germany, the Federal Statistical Office publishes a range of data on cases currently before the courts.[173] Individual courts also produce annual statistical reports analyzing the number of cases and the performance of judges, but the relevant ministries produce more comprehensive reports.[174] In Finland, under the Courts Act (673/2016), courts are required to prepare annual reports on their activities (including joint reports by several courts), which are public, i.e. they must be made available to the public.[175] Court statistics (e.g. number of cases, duration of proceedings) are also compiled by the judiciary and published on its website, usually in Finnish. The statistics come directly from the courts' information systems and have included information on court cases since the beginning of 2014. It should be noted that the NCA does not compile statistics on request, as this is the task of the information service of the Legal Register Centre, from which statistics on individual courts can also be obtained.[176] In Hungary, the President of the NOJ decides on the collection of court statistics and the central tasks related to data processing.[177] The NOJ carries out its official statistical activities for quality assurance purposes, within a regulated framework,[178] and as part of this, collects statistical data on the caseload of the courts, how cases are dealt with, the duration of completed and pending cases, and the defendants in criminal cases that have been concluded with a final decision. The NOJ collects, processes, stores, analyzes, provides, communicates, and publishes the data in a modern format using well-established statistical methods. This helps to ensure that, by providing information on the data and the links between them, citizens, state, social and economic organizations have an objective picture of the processes of the administration of justice in the courts.[179] Within the framework of the OSAP, the NOJ provides (i) statistical data on adult defendants in criminal proceedings that have been finally concluded, (ii) statistical data on juvenile defendants in criminal proceedings that have been finally concluded, (iii) statistical data on the caseload of district courts, (iv) statistical data on the caseload of courts of first instance, (v) statistical data on the caseload of courts of second instance, (vi) statistical data on the caseload of courts of appeal, (vii) statistical data on the caseload of commercial courts, and (viii) the case statistics of the Curia. It then publishes detailed case statistics from the data collected, and prepares detailed analyses and statistical year-books.[180] The data is made available to the public free of charge on the NOJ website in half-year and annual break-downs.[181] Turning to the question of annual reports, the President of the NOJ is required to report on his activities every six months, starting on June 1, 2023, in a document structured as specified by the NJC, and to report annually to the Curia, the presidents of the courts of appeal, and the presidents of the regional courts.[182] In addition, the President of the NOJ must report annually on the

- 40/41 -

general situation of the courts and their administrative activities to the National Assembly of Hungary and, once a year, to the National Assembly of Hungary's committee responsible for justice.[183] These essentially constitute the annual reports of the President of the NOJ and the reports for the first half of the year, which are also published on its website. These documents analyzing the administration of justice provide perhaps the most comprehensive overview of the situation of the courts, but their irreplaceable nature can also be criticized for the fact that, in many cases, they do not approach individual topics and issues in the same way, which often hinders transparency. It also happens that some annual reports simply do not address issues that have been examined in detail in the past, making it extremely difficult, if not impossible, to compare individual years.

7. Digital dimension

In Germany, the judiciary has no self-governing body. The tasks of the courts and their staff are differentiated according to whether they perform judicial or administrative functions. Where courts perform judicial administrative tasks (e.g., personnel matters, organization of IT operations), they act as part of the executive branch. In the federal states, judicial applications are operated by the state's IT service providers, either part of another ministry (e.g., the Ministry of Digital Affairs or the Ministry of the Interior) or belong to the court administration itself (e.g., ITD NRW). Each federal court is responsible for operating its applications. They maintain their infrastructure for this purpose, but in this case, they also act as part of the executive branch in accordance with the above division.

In Finland, as stated in the Strategy of the NCA 2021-2025, the agency is responsible for maintaining and developing the courts' information system, i.e., organizing ICT solutions.[184] It is well known that Finnish courts have some of the most advanced IT systems, which, thanks to their user-friendly nature, promote the efficiency and transparency of court proceedings. The Finnish Parliament and Government continuously support ICT developments in the judicial system to keep pace with technological innovations and social demands.[185]

In Hungary, the annual reports of the President of the NOJ show that the ongoing technical upgrading and modernization of courts, i.e., their computerization, informatization, and digitization of the courts is an essential tool that is also suitable for dealing with serious problems and, partly due to the most general narrative on digital governance, offers a more accessible, faster, more efficient, more cost-effective and more democratic (more transparent and open) justice system. In Hungary, therefore, the NOJ is responsible for developing, maintaining, operating, and improving the IT systems of the courts, meaning that ensuring the smooth functioning of the IT infrastructure that facilitates the administration of justice is not the responsibility of individual courts. The management and operation

- 41/42 -

of court servers are coordinated centrally by the NOJ.

8. Ethical dimension

The rules of conduct for judicial ethics are laid down in laws, but there is no uniform code of judicial ethics in Germany. According to Section 39 of the DRiG "[b]oth while performing and not performing their official duties, including political activities, judges are to conduct themselves in such a manner that confidence in their independence is not jeopardized". Issues relating to professional ethics are frequently and widely discussed among German judges, including in continuing education courses. In addition to initiatives by the federal states, the German Association of Judges (Deutscher Richterbund)[186] has published a document entitled Judicial Ethics in Germany. This document does not seek to lay down professional ethical guidelines or rules of conduct but rather summarizes values such as independence, impartiality/lack of bias, integrity, a sense of responsibility, moderation/restraint, humanity, courage, diligence, and transparency, which characterize self-aware and responsible judges.[187]

In Finland, the Finnish Association of Judges has drawn up and approved the Ethical Principles for Judges, which reflect the views of the judiciary on how the administration of justice can be carried out in a professionally ethical manner. These principles promote transparency and information, as they help people seeking justice to judge the administration of justice on the right basis; they also serve as a guideline for judges in their self-assessment. It should be emphasized that "[t]he purpose of these ethical principles is not to set out what is required of a good judge but to describe the ethically correct approach to a judge's work"[188]. As regards further elements of the ethical dimension of the courts, it can be said that, in general, judicial immunity is high, but Finnish judges can be considered accountable. Judges have no disciplinary body or functions, but in 2021, the Finnish Association of Judges established an ethical advisory body to assist judges concerning ethical rules. However, the body has not yet begun its work.[189]

In Hungary, the NJC adopts the Code of Ethics for Judges and publishes it on its central website,[190] and interprets it through its position statements.[191] Hungarian ethical guidelines follow the principles established at national and international level,[192] and in line with global trends, the ENCJ's Judicial Ethics - Principles, Values and Qualities, which has served as a guideline since June 2010 to reinforce common principles and values among European judges and to enable them to align their conduct as closely as possible with these principles and values.[193] In my viewpoint, the essence of this dimension, particularly in relation to Hungary, is summarized in the response given by former Minister of Justice Judit Varga to a request from the Constitutional Court of Hungary: "It should be noted that the Code of Ethics for Judges [...] defines the conduct to be followed by judges in accordance with ethical standards that go beyond legal

- 42/43 -

requirements and are in line with the moral expectations of an independent judiciary in a democratic state governed by the rule of law, and also lists conduct that is offensive or threatening to the dignity of the judicial profession, which, if committed seriously, may ultimately constitute a disciplinary offense. According to Section 105(b) of the [Judges' Status Act], a judge commits a disciplinary offense if he or she culpably violates or jeopardizes the authority of the judicial profession through his or her lifestyle or conduct. Consequently, the provisions of the Code of Ethics for Judges may also affect or influence the public law status of judges."[194]

9. Political dimension

Among the three countries examined, Germany has the most permissive regulations regarding the political involvement of judges, albeit within a clear legal framework.[195] In accordance with the separation of powers, Section 4(1) of the DRiG says judges cannot be judges and lawmakers or law enforcers at the same time. This also applies to members of the Constitutional Court under the Federal Constitutional Court Act.[196] If a judge runs for political office at the federal or state level, they must take unpaid leave for two months prior to the election. Suppose they accept a political office at the federal or state level. In that case, they must resign from the judiciary,[197] as under the applicable rules, holding political office is generally incompatible with the office of a judge while in office. In contrast, judges at local courts may hold political office at the local level during their term of office.[198] German law, therefore, does not expect judges to be apolitical; on the contrary, judges who actively participate in democratic processes and take on a community and social role are considered more desirable than their colleagues who reject this.[199] However, according to Section 39 of the DRiG, judges must conduct their political activities in such a way that confidence in their independence is not undermined, i.e. they must exercise a certain degree of restraint in their political expressions. There is currently a heated debate as to whether this practice is correct and, if so, how a person holding a political office can be reinstated to their judicial position, given that certain forms of conduct and actions cannot be forgotten when they return to their judicial position, which in turn may call into question their independence.[200]

The Finnish legal system emphasizes the practical implementation of the principle of judicial independence. Consequently, although freedom of expression and association are not prohibited per se, judges may not engage in active political activities or be members of political parties in order to preserve their independence, impartiality, and integrity.[201] In addition, judges are required by law to avoid anything that could compromise the objectivity of their judgments.[202] Point 2 of the Ethical Principles For Judges states explicitly that "[w]hen administering justice, a judge must remain independent of the legislative and executive branches of the government. In order to remain independent, a judge must also remain

- 43/44 -

free of ties to other parties wielding influence in society, such as politicians and business and media representatives".

According to the third sentence of Article 26(1) of the Fundamental Law, which is similarly enshrined in Section 39(1) of the Judges' Status Act, judges may not be members of political parties or engage in political activities. Accordingly, Hungarian judges must avoid any opinions or conduct that could reveal their political convictions to the public.[203] In addition, they should strive to avoid expressing opinions that could lead others to draw conclusions of a political nature or a dubious nature.[204] Nonetheless, the "top leaders" of the judicial administration, i.e., the president of the NOJ, the president of the Curia, and the president of the NJC, can express their opinions on political issues without excessive restrictions, which is a kind of an exception to the rule of staying out of political debates. At this point, it is worth noting that the courts are committed to shaping public debate on issues relating to the administration of justice from a professional perspective, which can contribute effectively to a (more) high-quality political and social discourse.

V. Conclusion

As an abstract conclusion, "[t]he improved models of court administration are not an end in themselves but merely a means to an end - and that end is the delivery of better judicial services to the public. [...] Put simply, what is required is a modern model of court administration that minimizes conflicts, facilitates long term planning, promotes cooperation and coordination amongst the branches of government, fosters change and systemic reforms and improves responsiveness and accountability to the public."[205]

The domestic judicial administration model change was expected to do something similar. However, today's debate is not so much about whether this paradigm shift was justified or necessary but about the extent to which the new model has lived up to the expectations of its introduction. Thus, the practical implementation of the control function of the National Judicial Council (hereinafter: NJC), and subsequently, the powers of the President of the National Office for the Judiciary (hereinafter: NOJ) continued to dominate over those of the NJC, not least because the current NJC, composed exclusively of judges, did not enjoy full autonomy and independence from the NOJ.[206] All in all, however, it can be said that since the creation of the President of the NOJ and the model based on the duality of the NJC, it has given insight into many aspects of the model, thus allowing room for corrections which now seem to be emerging as a workable central administrative construct in the long term.[207]

Different institutional arrangements in different states govern the relationship between the judiciary, the legislature, and the executive. However, the common denominator is the protection of the common constitutional values of judicial independence and impartiality. The financial and organizational opera-

- 44/45 -

tion of the courts and their accountability present a varied picture, but the type of institutional set-up - as in the case of Hungary - has a crucial influence on the extent to which tensions can arise between politicians, the administration, and the professionals in the judiciary.[208] In connection with accountability, special attention should be drawn to the earlier statements by Szonja Navratil, who said that "[a]n organization that monitors itself, where the public is only aware of half of its activities [...], which regards all criticism as an attack, clearly does not promote greater efficiency. [...] no organization can function effectively without adequate control and accountability. Even with the best of intentions, a lack of control and accountability undermines the activities of an organization".[209]

As with other solutions, the aim of Hungarian judicial administration is to guarantee the efficient and effective administration of courts, which, according to the Canadian Judicial Council Discussion Paper, has six cardinal requirements.[210] This pragmatic approach allows us to briefly examine the abstract essence of this concept.

Firstly, strong leadership is necessary for the administration of the courts. This allows for agile decision-making while taking into account the views of the participants and contributors to the administration. Without this, a model's stability cannot be guaranteed in the long term. In my opinion, the Finnish model is the best at meeting this requirement.

Secondly, a shared vision and set of objectives are essential. In order to achieve any lasting change in the field of judicial administration, it is necessary to know what the actors involved want to achieve (vision, objective) and how they can achieve it. It should also be borne in mind by the actors involved/decision-makers that whatever changes are made to the existing model or the introduction of an alternative model, the judiciary and the executive will remain jointly responsible for matters relating to justice, including judicial administration.[211] In this regard, the Finnish model also shows the most excellent stability and cooperation.

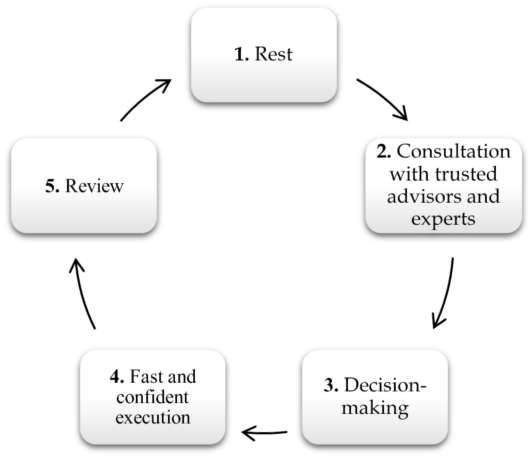

Figure 1 - Prudent resoluteness

Thirdly, a proper organizational and management structure is needed. This presupposes a constitutional/constitutional law accurately reflecting its essence, not too detailed but sufficiently comprehensive, and applying the so-called prudent resoluteness, the five-step decision-making system used in the corporate sphere.[212]

In this regard, each model has different strengths, which means settling on a single best solution is impossible.

- 45/46 -

On the one hand, the German model is concise, but at the same time it has subsidiary and autonomous regulation. On the other hand, the Finnish model has more detailed regulations, but its decision-making process is less rapid and less accountable. Finally, the Hungarian model has a more flexible organization but operates with vast and strong management powers.

Fourthly, practical strategies, tactics and procedures, including an operational plan, are necessary for the prosperous administration of justice. The so-called 4 Disciplines of Execution or 4DX method can contribute to this. The essence of this is that it assigns success factors, i.e., high-impact activities to be carried out/implemented to achieve the selected vital goal, which are tracked and engaged by incentive scoreboards and report on results periodically and consistently on a scheduled basis.[213] In this regard, it should be noted that all the countries examined operate effectively, but the Hungarian model has the most complex powers and influence in this area.

Fifth, adequate resources, including sufficient ones for the change process, are an elementary presence since their absence, as shown above, can quickly lead to a vulnerable situation. As long as there is no free and adequate financial possibility for maneuvering, it is only a question of "pseudo-autonomy" since there is no unlimited autonomy with "other people's money". Each regulatory solution is financially dependent on the political branches of government.

Sixthly, a modern 21st-century judiciary is unthinkable without appropriate support systems, including management information systems, cashflow systems, etc. Each regulatory solution makes serious efforts in this regard, but currently, the Finnish model uses these systems most extensively.

To close the research, it is worth mentioning Robert W. Tobin's thoughtful thoughts on judicial administration: "[t]he introduction of court administration is more than a judicial acceptance of the latest trends in public administration. Court administration is preserving judicial independence in the modern era"[214], which not only affects the administration of justice but also has broader implications.[215] ■

NOTES

* This study was supported by the EKÖP-24-3. University Research Scholarship Program of the Ministry for Culture and Innovation from Source of the National Research, Development and Innovation Fund. The manuscript was completed on February 25, 2025. The author would also like to thank Péter Tilk (Professor and Head of the Department of Constitutional Law, Faculty of Law, University of Pécs) and József Petrétei (Professor of the Department of Constitutional Law, Faculty of Law, University of Pécs) for the irreplaceable professional support provided for the study.

[1] For more details, see ©ipulova, Katarína - Spáč, Samuel - Kosař, David - Papouąková, Tereza - Derka, Viktor: Judicial Self-Governance Index: Towards Better Understanding of the Role of Judges in Governing the Judiciary. Regulation & Governance 2023/1, pp. 27-28.

[2] See Article 92 of the Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany (Grundgesetz für die Bundesrepublik Deutschland, hereinafter: GG).

[3] Cf. Zeller Judit: Német Szövetségi Köztársaság. In: Chronowski Nóra - Drinóczi Tímea (eds.): Európai kormányformák rendszertana. Budapest, HVG-ORAC, 2007. p. 122.

[4] See Section 12 of the Courts Constitution Act (Gerichtsverfassungsgesetz, hereinafter: GVG).

[5] For more details, see Gombár Zsófia: A német igazságszolgáltatás felépítése és működése. Comparative Law Working Papers 2021/3, pp. 1-6.

[6] See Article 95(1) of the GG. For more details, see the German Judiciary Act (Deutsches Richtergesetz, hereinafter: DRiG).

[7] See Article 96 of the GG. Only the Federal Patent Court and the Federal Court for the Service of Military Personnel Stationed Abroad have been established of other federal courts. See Belling, Detlev W. - Szűcs Tünde: Bevezetés a német jogba. Acta Universitatis Szegediensis - Acta Juridica et Politica 2011/1, p. 101.

[8] See European Justice: Gerichtsorganisation der Mitgliedstaaten - Deutschland. https://tinyurl.com/347r2tnh (15.09.2024.)

[9] See Badó Attila - Márki Dávid: A német bírósági

- 46/47 -

igazgatás alapjai. Comparative Law Working Papers 2020/1, p. 19.

[10] See Badó - Márki (2020) p. 4.

[11] See Fekete, Kristóf Benedek: Models of the Central Administration of Courts. Jura 2024/2, pp. 2122.

[12] Cf. Badó - Márki (2020) p. 4.

[13] Cf. Kovács Mónika: Finn Köztársaság. In: Chronowski Nóra - Drinóczi Tímea (eds.): Európai kormányformák rendszertana. Budapest, HVG-ORAC, 2007. p. 262.

[14] In addition, the Aland Administrative Court operates as a separate administrative court in the autonomous Aland Islands, whose decisions can also be appealed to the Supreme Administrative Court. See Bergström, Erika: Finnish Law on the Internet. https://tinyurl.com/ynxyj78w (13.10.2024.)

[15] See Articles 98-101 of the Finnish Constitution.

[16] See Council of Europe: The Finnish Judicial System. https://tinyurl.com/6pyh28p7 (13.10.2024.)

[17] See Article 106 of the Finnish Constitution.

[18] See Nylund, Anna: An Introduction to Finnish Legal Culture. In: Koch, Sören - Sunde, Jørn Øyrehagen (eds.): Comparing Legal Cultures. Bergen, Fagbokforlaget, 2020. p. 155.

[19] Cf. Aarli, Ragna - Sanders, Anne: Judicial Councils Everywhere? Judicial Administration in Europe, with a Focus on the Nordic Countries. International Journal For Court Administration 2023/2, p. 21-22.

[20] See Chapter 19a, Section 1 of the Courts Act (673/2016).

[21] Cf. Tuomioistuinvirasto: Tuomioistuinlaitos. https://tinyurl.com/226bmytj (13.10.2024.)

[22] See Chapter 19a, Sections 5-6 of the Courts Act (673/2016).

[23] See Chapter 19a, Section 7 of the Courts Act (673/2016).

[24] See Chapter 19a, Section 7 of the Courts Act (673/2016).

[25] See Aarli - Sanders (2023) p. 22.

[26] See Chapter 19a, Section 8 of the Courts Act (673/2016).

[27] See Tuomioistuinvirasto: Tuomioistuinvirasto. https://tinyurl.com/mpv9fz84 (13.10.2024.)

[28] See Article 25(1) of the Fundamental Law of Hungary (hereinafter: Fundamental Law).

[29] See Article 24(1) of the Fundamental Law.

[30] Of course, the Constitutional Court is connected to the activities of the courts in many ways, suffice it to think of constitutional complaints. For more details, see Fekete Kristóf Benedek: Az alkotmányjogi panasz perjogi vonzatai, eredményeinek hatása a bírósági jogalkalmazásra. Jura 2021/3, pp. 5-31.

[31] See Article 25(4) of the Fundamental Law and Act CLXXXIV of 2010.

[32] See Article 25(6) of the Fundamental Law.

[33] See Section 66 of Act CLXI of 2011 on the Organisation and Administration of Courts (hereinafter: Court Organisation Act).

[34] Cf. Osztovits András: A bíróságok az új alkotmányban. In: Drinóczi Tímea - Jakab András (eds.): Alkotmányozás Magyarországon 2010-2011. II. kötet. Budapest-Pécs, Pázmány Press, 2013. p. 314.

[35] See OBH: Általános tájékoztató. https://tinyurl.com/49xwf8yj (07.10.2024.)

[36] See Osztovits (2013) p. 315.

[37] See Article 98 of the Finnish Constitution.

[38] See Chapter 19a, Section 2(11) of the Courts Act (673/2016).

[39] See Article 25(8) of the Fundamental Law.

[40] See Section 17 of the Court Organisation Act

[41] See Section 76(1)(d) and (f) of the Court Organisation Act. For a detailed discussion of this issue, see Fekete, Kristóf Benedek: Communication of the Judiciary. Essays of Faculty of Law University of Pécs Yearbook of 2021-2022, pp. 17-20.

[42] Cf. Rainer Lilla: A törvényes bíróhoz való jog, mint a tisztességes eljárás részkövetelményének szabályozása és a hazai gyakorlatban felmerülő problémái. In: Miskolczi Bodnár Péter (eds.): XI. Jogász Doktoranduszok Országos Szakmai Találkozója. Budapest, KRE ÁJK, 2018. p. 157.

[43] See BVerfGE 82, 159 [134].