Dr. Bettina Nyikos[1]: Problems in disclosing and promulgating local government decrees in the light of government office supervision[1] (JURA, 2019/2., 390-404. o.)

I. Introduction

I have chosen "problems in disclosing and promulgating local government decrees in the light of government office supervision" as the topic of this paper mostly because of my strong interest in the topic and the fact that the legality of public administration is one of the most frequent topics in public administration law literature. The main goal of my paper is to describe the system and the specificities of legal control over Hungarian local municipalities and to draw conclusions-with focus on the promulgation and disclosure of local government decrees.

I have structured my paper to first analyse the history of local legislation and its place in the hierarchy of sources of law, then, second, to describe legal supervision as an institution. After the overview of this institution, I will describe the rules of local legislation, with focus on the promulgation and disclosure of local decrees.

My overview of the topic will use practical examples taken from the work of the Baranya County Government Office to illustrate the results of legal supervision in terms of the promulgation and disclosure of local decrees.

The place and role of local government legislation are determined by the place of local government system in the Hungarian public administration system. Local government legislation is basically determined by the relationship between the central power and the local power. The central power's legislation basically coordinates local legislation. We can say with courage that proper preparation of local government legislation is of essential importance. Consequently, normative regularisation will most probably not achieve its goal without perfect preparation, and poor preparation might frustrate all objectives. The problem can be aggravated further by the improper promulgation of legal regulations (the ignorance of decrees in our case), which might often have detrimental legal consequences.

Legislative changes in the recent years, including the new Local Government Law, the new Administrative Proceedings Act and the Administrative Procedure Act, had the inherent dilemma that local governments themselves had to adopt several new decrees and adjust existing ones to current affairs as well, with the consequence of producing a huge legislative mass that needs to be managed. The situation was made even more complex by the uploading of decrees in a common structure, the rules of which I will also describe.

II. History of local legislation

The right of local governments to legislate has a long history. This history began as early as in Hungary's medieval feudal society; its immediate predecessor was the functioning of local councils in the Hungarian local council system and the right to adopt local council decrees. The medieval relics of Hungarian local legislation are city lawbooks of city rights of mostly foreign origin and written in German or Latin. Such city lawbooks were, for example, the Lawbook of Nagyszőllős[2] or Buda. One of the most important sources was the statute, or "(helyhatósági) szabályrendelet" (local authority regulatory decree) in its adopted Hungarian name. The right to adopt statutes became significant as cities became more and more powerful during the 14[th] and 15[th] centuries when Hungarian cities exercising the right to adopt statutes emerged. From the 16[th] century onwards, counties and guilds also adopted statutes. The designation of local legislation developed as local legislation was emerging. "In his Hungarian translation of Kithonich's Directio Methodica, János Kászoni calls local

- 390/391 -

legislation "order". Hungarian lawyers of the 19[th] century coined new designations, for example, Czövek called local legislation "minor acts", Szlemenics called them "special orders" and Frank called them "act-like regulations". The latter designations already refer to the statute concepts conceived by the authors as well as the appearance of statutes as sources of law and their places in the feudal system of sources of law. The most common designation is "szabályrendelet" (regulatory decree); this, however, applies to sources of law issued by municipal bodies after 1848. The first rules of statute adoption (ius statuendi in Latin) are in the Tripartium of István Werbőczy[3]."[4] It must be pointed out that the requirement of absence of conflict between local laws and countrywide applicable customs and laws was expressed as early as at that time. During the 18[th] and 19[th] centuries, cities' local legislation meant statutes and normative council decisions. Before 1886, the source of the mandatory force of regulatory decrees was the royal privilege or ancient custom. Within the scope of statutory legislation, the proposal of 1843 defined the concept and scope of regulatory decrees. Regulatory decrees were determined to regulate local affairs t hat cannot be regulated with countrywide effect, because they are required to consider local affairs. According to the proposal, orders ("Kászoni" orders) that are adopted as standards for all similar cases are called rules. "The Hungarian absolutist state eliminated the self-government of the estates and deformed the cities' organisations as well as their rights increasingly during the 17[th] and 18[th] centuries. Regulatory decrees required the approval of the sovereign or government bodies, and statutes in force were often repealed quickly. Regulatory decrees were degrading in the hierarchy of sources of law and were deemed to regulate increasingly insignificant local affairs. The first modern statutes appeared in the Hungarian Reform Era."[5] Act XLII of 1870 on the Regulation of Municipal Authorities played a very major role in this field, as it was the first to regulate the right to adopt regulatory decrees in detail. Section 2 of Act XLII of 1870 regulated the right to adopt regulatory decrees as follows. "Given their right to self-governance, municipalities take measures, decide and adopt regulatory decrees (statutes) for its own internal affairs independently; they implement their regulatory decrees through their own bodies; elect their officers; determines the costs of municipal administration and secures funds for them; contacts the government directly."[6] Section 5 of the same Act sets the limits of the right to adopt regulatory decrees: "Municipalities may adopt regulatory decrees only within the scope of its own competence as a local authority. Regulatory decrees may not conflict acts and government regulatory decrees in force, violate the right to self-government of municipalities (villages and market towns) and may be implemented 30 days after their due promulgation."[7] Another major act regulating the right of villages to adopt regulatory decrees was Act XVIII of 1871 on the Regulation of Villages. We must point out that this was the first time in Hungarian legal history when the legislator recognised the right to legislate of villages. Basically, we can speak of local decrees since the appearance of this act. Section 29 of this Act laid down that "regulatory decrees of villages may not conflict acts of Parliament, regulatory decrees in force of the Government and the municipality; regulatory decrees are to be immediately submitted to the municipality and may be implemented only after its public or implied approval."[8] Act XXI of 1886 on Municipalities re-regulated the right to adopt regulatory decrees as well. It sustained "private parties' opportunity to appeal (Section 8), and the minister responsible for the subject area of a regulatory decree had to issue a submission disclaimer for it. This was necessary for the promulgation of regulatory decrees and their implementation on the 30[th] day following their promulgation."[9] Without aiming to be exhaustive, the next major milestone was the regulation of the promulgation of county regulatory decrees in Section 33 of Act XX of 1901 on the Simplification of Administrative Proceedings: "The Rules of Administration of every county shall establish a county official gazette. County regulatory decrees and decisions in the general interest shall be communicated in the county official gazette and shall be deemed promulgated on the eight day following the publication of the relevant issue. General regulations and communications of

- 391/392 -

authorities of second instance shall be generally disclosed in the county official gazette as well"[10]. "The overview of the previous era also shows that Hungarian legislation focused most on the issue of promulgating laws in terms of this topic. We can already identify two facts as its weaknesses. One of them belongs to the field of political theory. Given that the building of a Marxist state (and political establishment) started in 1949; the system was not either democratic or free from discrimination. According to the official ideology of the state, the working class held the power of the people. Many who did not belong to this class could expect stigmatisation, persecution or, in the worse case, the loss of their property, freedom or even their lives. The other weakness, a legal one, was, consequently, that the Marxist-Leninist establishment of the state-based on democratic centralism-was governed less by the law but, much rather, by the will of leading party officers of the Hungarian Working People's Party, later Hungarian Socialist Worker's Party, with special regard to the political and power interests of the occupying Soviet Union."[11]

Section 31 of Act XX of 1949, the second written Constitution of Hungary, said the following about local legislation: "Within the scope of their operations, local councils shall adopt local decrees that may not conflict statutes, law decrees or decrees of the Cabinet Council, the ministers or superior councils. Local council decrees shall be announced as customary. Local councils may annul or change their subordinated councils' decrees, decisions or measures that conflict the Constitution or constitutionally adopted legislation."[12]

It is imperative that we mention legislative issues concerning the council system. "The opportunity to adopt regulatory decrees existed between 1945 and 1950; local administrations, however, took it to a lesser extent owing to the strengthening of the Soviet-type centralised state model. Act I of 1950 on Local Councils (Council Act 1) ensured the opportunity for local councils to adopt local decrees, called regulatory decrees, in matters requiring permanent regulation in their territories of jurisdiction. Act X of 1954 on Councils (Council Act 2) ensured the issuance of council decrees and council decisions. These were not allowed to conflict pieces of legislation adopted by superior state bodies and public administration bodies. Sections 33 and 34 of Act I of 1971 (Council Act 3) dealt with local legislation by practically repeating the text of Council Act 2. What we should point out about Council Act 1 is that it regulated council legislation and paid special attention to organisational and operational rules, which are a type of decree. These were the only decrees that remained subject to approval. As a result of these regulations, the number of local decrees in force at the end of the council system was around 17,000-18,000. These included regulations establishing obligations as well as ones establishing provisions that lay down something. After the political changes in 1989-1990, the legal status and legislation of local governments were regulated by the Constitution, Act LXV of 1990 on Local Governments and Act XI of 1987 on Legislation.

Under the authorisation granted in Paragraph (1) of Section 16 of the Local Governments Act, the municipal council adopts local government decrees to regulate local social affairs not regulated by an act of Parliament and to implement acts under statutory authorisation. "Local government decrees shall be promulgated in the local government's official gazette and/or as locally customary (defined in the organisational and operational rules)."[13] Accordingly, the organisational and operational rules must regulate

- that the local government has an official gazette; promulgation is done in the official gazette; the date of promulgation shall be the month and day of the publication of the official gazette;

- that the local government does not have an official gazette; local government decrees shall be promulgated by displaying it in its entirety on the bulletin board of the mayor's office. Promulgation on posters is possible on other advertising means such as advertising columns, bulletin boards, etc. The foregoing clearly show that we are arriving and coming nearer and nearer to today's regulations.

In the following, I will describe the Hungarian regulations in force-more specifically, the piece of legislation called Act CLXXXIX of 2011

- 392/393 -

on the Local Governments of Hungary, which determines the basis for the functioning of local governments. I would also point out Act CXXX of 2011 on Legislation, which establishes detailed procedural and substantive rules for local decrees. I would also mention Decree No. 61/2009. (XII. 14.) of the Minister of Justice and Law Enforcement on Legislative Drafting, which also provides regulations concerning this topic.

III. Relation between local decrees and the hierarchy of sources of law

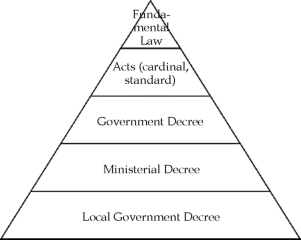

To understand legislation in force, it is important that we first see where local government decrees are in the hierarchy of sources of law. To do that, we must understand two basic concepts, the "legal system" and the "source of law", to derive other conclusions from them. The legal system is nothing more than all the legal norms in force in a state at a specific point of time. A source of law means, in the sense of constitutional law, the appearance of the law (e.g. act of Parliament, decree, decision, instruction) as well as the legislative body (e.g. Government, minister). In this context, we can speak of internal or external sources of law. Internal sources of law are the power making the law (e.g. the National Assembly) and having legislative capacity. External sources of law are the appearance of the law that allow the understanding of a specific piece of legislation (e.g. act of Parliament). We can also speak of legal instruments of state administration including normative decisions and normative instructions. "In Hungary, a country with a legal system belonging to the legal family of continental law, these sources of law form a closed system and are organised hierarchically. The basis of the hierarchy is always declared by the place of the material or internal source of law in the state structure. The point of the hierarchy is to ensure that pieces of legislation of lower levels may not conflict those of higher levels. In making sources of law, therefore, the essential requirement for content that the source of law being made does not conflict with the content of higher-level sources of law must apply, the source of law would otherwise be invalid. Local government decrees are the lowest level of this system of source of law; it may, therefore, not conflict any other laws.

According to Paragraph (2) of Article T) of the Fundamental Law of Hungary, legal regulations shall be Acts, government decrees, prime ministerial decrees, ministerial decrees, decrees of the Governor of the National Bank of Hungary, decrees of the heads of autonomous regulatory organs and local government decrees. In addition, decrees of the National Defence Council adopted during a state of national crisis and decrees of the President of the Republic adopted during a state of emergency shall also be legal regulations.

(3) No legal regulation shall conflict with the Fundamental Law."[14]

The figure illustrates the place of local government decrees in the hierarchy of sources of law perfectly; it is, therefore, lowest-level source of law and may not conflict any legal regulation. The Fundamental Law of Hungary is at the top of the hierarchy of sources of law. We should also mention that territorial and local governments are not different in this regard; the local council decrees and territorial government decrees are, therefore, in a subordinate relationship. In addition, we must also consider, in substantive terms, the room for maneuvering provided by European community law and EU legal acts, although these are not shown in the figure; i.e. we must stay within the framework of national regulation. Among the EU norms, we should mention the Strasbourg Charter of 1985, the European Charter of Local Self-government. It is an inter-

Figure 1. Hierarchy of the sources of law

- 393/394 -

national convention and not an EU directive; EU membership is not required for joining it. The European Union does not have a single structure of public administration. The Charter attempts to summarise the common features and values of different local government systems, and the signatory member countries assume the obligation to create and uphold the conditions for free and democratic self-government. Hungary could not meet the conditions of the Charter during the council system; the Charter was, therefore, promulgated in 1997 (Act XV of 1997) and applies from 1 July 1994.

Generally, there are four types of validity conditions and these must apply together. The first condition is that legal regulations must come from a body with legislative competence (Parliament, local government). The second one is that it must be in line with the hierarchy of sources of law; i.e. local government decrees may not conflict any act of Parliament. (This is stressed in Paragraph (3) of Article 32 of the Fundamental Law of Hungary.) The third requirement is that legal regulations must be disclosed, i.e. promulgated, appropriately. This can be done either in the Hungarian Official Journal or in local papers. Finally, local regulations must meet general and special procedural rules; more specifically, validity of the legal regulation requires a two-third majority, and this must be guaranteed.

IV. Regulations in force concerning the promulgation and disclosure of local decrees

The law is accessible and knowable, which means that any legal regulation becomes effective and operative only through promulgation. Legal regulations hidden from the public or confidential do not exist. Publicity applies to the preparation of legal regulations as well as the disclosure of draft legislation. The promulgation of legal regulations is usually regulated by an act of Parliament. Legal regulations are promulgated mostly in official gazettes, but they may be promulgated on electronic interfaces as well. Local government decrees may be promulgated currently on the website of the minister responsible for local governments. The promulgation of legal regulations means the first official disclosure of written legal regulations to reveal and make the adopted and signed texts of the legal regulations to the beneficiaries and obligors. The promulgation of legal regulations, therefore, implies the disclosure of legislation in the first place, i.e. allowing all to familiarise themselves with the legal regulation. Whereas "ignorance of legal regulations does not constitute exemption", or, in other words, nobody may refer to ignorance of appropriately published norms; the state, therefore, must ensure access and availability of the legal regulations only. This is, however, often not that simple, because local governments do not disclose legal regulations on their own internet interfaces (websites) or do not indicate them appropriately or fail to meet their government-decree obligation, i.e. to upload them to the online interface of the National Legislation Database, njt.hu, causing considerable inconvenience and material damage to those involved, including themselves.

The disclosure of legal regulations means the first official publication of written legal regulations, informing beneficiaries and obligors of the adopted and signed text of a legal regulation, or at least making it accessible to them. Organisational and operational rules often have an integral provision that the promulgated decree must be available in a library or public entity. Having regard to the fact that the indication of legal regulations during promulgation is not a matter od legislative drafting, the law lays down the relevant fundamental rules in an act and authorises the definition of detailed rules. Several regulations of the Fundamental Law of Hungary, the legal regulation at the top of Hungary's hierarchy of sources of law, have rules pertaining to local governments regarding promulgation, disclosure and legal supervision. Article 32 of the Fundamental Law of Hungary provides for that local governments have the right to adopt decrees and make decision. "Acting within their functions, local governments shall adopt local government decrees to regulate local social relations not regulated by an Act, and/or on the basis of authorisation by an Act."[15] The Fundamental Law of Hungary specifies the superior body

- 394/395 -

to which local governments are subordinated; these are the government offices. The Fundamental Law also specifies the legal consequences the superior body may enforce against local governments in case of breach of the law. "The capital or county government office may apply to a court for the establishment of non-compliance of a local government with its obligation based on an Act to adopt decrees or take decisions. Should the local government fail to comply with its obligation to adopt decrees or take decisions by the date determined by the court in its decision establishing non-compliance, the court shall, at the initiative of the capital or county government office, order the head of the capital or county government office to adopt the local government decree or local government decision required to remedy the non-compliance in the name of the local government."[16] I will discuss the supervisory system in detail in the latter part of this paper.

Decree-making is left to the scope of competence of the local council. This competence may not be transferred. Decrees are made with the qualified majority of the local council. The Local Government Act lays down the following rules on promulgation. "Section 51 (2) Local government decrees shall be promulgated in the local government's official gazette and/or as locally customary (defined in the organisational and operational rules). Decrees of local governments that have own websites shall be disclosed on the local government's website as well. The municipal notary shall procure that decrees are promulgated. Local governments shall send the local government decree to the government office immediately after promulgation, and the government office shall forward it to the minister responsible for the legal supervision over local governments.

(3) If the promulgated text of the local government decree deviates from the signed text of the local government decree, then the mayor or municipal clerk shall initiate the correction of the deviation. Local governments shall be corrected prior to their entry into force or on the sixth working day following their promulgation at the latest. If a deviation is detected, the municipal clerk shall ensure the disclosure of the correction in the same way as the local government decree was promulgated."[17]

Literature on constitutional law and legislation distinguishes, although not always consequently, between the promulgation of legal regulations and theirdisclosure (communication). Promulgation means the first official communication available for and addressed to all. Accordingly, legal regulations, as norms obligatory to everybody, require promulgation. Promulgation must always be as regulated by the law and in the place and form specified by the law.

Disclosure (communication), on the other hand, means that a conceptual element of promulgation in the narrower sense is missing, i.e. it is not about a legal regulation and not the first or non-official publication. Accordingly, the publication of legal instruments of state administration as well as any other publication of legal regulations and other norms for information (e.g. education) purposes is disclosure.

"In connection with legislative competence, the Fundamental Law of Hungary lays down the constitutional obligation that generally mandatory behavioural rules be promulgated in the official gazette [Paragraph (1) of Article T]. The same provision also allows that a cardinal Act may lay down different rules for the promulgation of local government decrees, and of legal regulations adopted during a special legal order."[18]

Act CL of 2016 on General Public Administration Procedures and Act XCCC of 2010 on Legislation do not provide for any theoretical obstacle to or exclude the promulgation of local government decrees on the local government website in the near future, as being locally customary, having regard to the internet electronics modernisation of the municipality. Laying down the relevant procedural rules in the local government's organisational and operational rules is, however, crucial in this case. Another interesting question is the publicity of the preparation of legal regulations, which focuses on familiarisation with the legal regulations being prepared and the right to submit proposals.

Government Decree No. 338/2011. (XII. 29.) on the National Legislation Database defines the conditions and requirements for uploading to the National Legislation Database in detail. "Section 4 (1) The promulgated texts of all local

- 395/396 -

government decrees that were promulgated after 30 June 2013 and still have not entered into force shall be disclosed in the National Legislation Database. If the Local Government Council of the Curia rules that a local government decree or any of its provisions is not to enter into force, then the relevant decision must be immediately referred to at the legal regulation concerned by the decision after publication in the Hungarian Official Journal.

(2) Except for Paragraph (3), the following of each local government decree promulgated after 30 June 2013 and in force on the day of the search shall be disclosed with consolidated text in the National Legislation Database, including local government decrees amended by local government decrees promulgated after 30 June 2013

(a) its text in force on the day of the search, and

(b) the "as at" statuses on and after the search date.

(3) Local government decrees that entered into force before 1 July 2013 and were changed after 30 June 2013 and are in force on the search date shall be disclosed in the National Legislation Database in their consolidated version in force on the search date as well as in an "as at" status applicable after the search date.

(4) The municipal clerk shall forward the local government decree and its consolidated versions pertaining to each of its "as at" versions to the Budapest-Capital Government Office and the county government office, the minister responsible for the legal supervision over local governments and the minister of justice through the designated IT system set up by the provider of the National Legislation Database.

(5) The municipal clerk shall disclose the consolidated version in the National Legislation Database within five working days following the promulgation of the local government decree or the amending local government decree."[19]

The strict requirements allow the conclusion that publicity plays a special role in the initiation of decrees as well. Decree-making may be initiated by the law or a suggestion of a practitioner of law or the motion of the local council. It must be stressed that the territorial scope of such laws covers only the administrative area of their respective municipality. "In case of local government decrees, it applies to natural persons, legal entities and organisations without a legal personality within the administrative area of the local government; in the case described in Paragraph (1a) of Section 5, it applies to the natural persons, legal entities and organisations without legal personality within the administrative area of local governments members to an association of local governments; in the case described in Paragraph (1b) of Section 5, it applies to the natural persons, legal entities and organisations without legal personality within the administrative area of local governments members to the association of local councils."[20]

The person preparing a piece of legislation must perform a preliminary impact assessment to assess the expected consequences and results of the regularisation. If the preliminary impact assessment is performed for a local government decree, then the council of the local government must be informed of its result. The preparatory phase might be different from time to time, because in most of the cases it is the subject-matter of the local government decree that determines the organisation which will perform the preparation; however, I do not want to say here that this could make the notary obsolete, because this is actually excluded by the law; however, it is not against the law-moreover it is sometimes obvious and expedient-that a professional, specialised organisation participates in this procedure.

The impact assessment must study the different impulses such as the social, economic, budget effects, the necessity of the piece of legislation in question, the consequences in case it is not made, the reason for making it and the personnel, material and financial requirements of applying it. If the draft decree is ready, then the next step is opinionating. Depending on the subject-matter of the decree, opinionating might consider different bodies, organisations. Opinions might come from the committees, legal practitioners, residents (if the draft decree is made available for public inspection), and social organisations may also play a special role.. Finally, the draft decree is submitted to the local council, and it is the municipal notary who plays the greatest role in a profession-

- 396/397 -

al submission. Decrees are usually adopted in two rounds. First, the submission is prepared and provided to the members of the local council in advance, then it is discussed in the sitting of the local council. The municipal clerk then drafts the final decree and he/she and the mayor sign it. The final step is promulgation, i.e. when the legal regulation is uploaded to the website of the municipality and the website of njt.hu and is promulgated in the locally usual way which can take several forms, as we know. The question what makes a local website good is obvious, because there are only a few websites that are indeed perfect and simple. There are several local websites that are simply impossible to understand. This raises several concerns regarding knowableness and disclosure. It is often difficult to steer through the websites themselves or to find the decrees despite the fact that local governments have more or less the same website structure. The situation is complicated further if somebody does not find a particular decree on the website. This does, however, not put an end to searching, because several local governments do not use search engines to ease the search.

V. Legal supervision

As prescribed by the Fundamental Law, the local government sends the decree to the government offices of the capital city and the counties immediately after the promulgation. "If the capital or county government office finds the local government decree or any of its provisions to be in conflict with any legal regulation, it may initiate a judicial review of the local government decree. The capital or county government office may apply to a court for the establishment of non-compliance of a local government with its obligation based on an Act to adopt decrees or take decisions. Should the local government fail to comply with its obligation to adopt decrees or take decisions by the date determined by the court in its decision establishing non-compliance, the court shall, at the initiative of the capital or county government office, order the head of the capital or county government office to adopt the local government decree or local government decision required to remedy the non-compliance in the name of the local government."[21]

The Government ensures-through its Department of Legal Supervision-the legal supervision over local governments through the government offices of the capital city and the counties. The purpose of legal supervision is to investigate the lawful operation of the council, committees, mayor, municipal notary, partial local government, association (if any) of the local government. The supervisory toolset is quite diverse, the one I would like to examine in detail is the scheme related to decree-making.

The Local Governments Act specifies it as follows: "If a local government decree conflicts the Fundamental Law of Hungary, then the government office shall suggest-through the minister-the revision of the decree in question by the Constitutional Court to the Government, if the legality appeal or initiative failed in terms of convoking the local council or the council of association, and-in the case specified herein - convocation of the local council or the association council was fruitless.

The government office shall send the draft motion both to the minister responsible for the legal supervision over local governments and to the local government concerned.

The Government Office may suggest the revision of the compliance of the local government decree with the relevant piece(s) of regulation to the Kúria (Supreme Court of Hungary). Concurrently with the launching of the court proceedings, the Government Office shall send the motion to the local government concerned."[22] It may be concluded that a local government decree may be sent to two constitutional bodies after its adoption, to the Constitutional Court for the inspection of its consistency with the Fundamental Law, to the Curia for the inspection of its consistency with other piece(s) of legislation. Local governments may, however, make not only decrees but decisions as well, which are then revised (if necessary) by the relevant administrative and labour court. It must be stressed that the legal supervisory procedure of the government office does not cover the local government's and its bodies' decisions which give grounds for labour disputes or disputes arising from public service

- 397/398 -

employment (except if the decision violates the law in favour of the employee) or a statutory court proceeding or administrative procedure, or which the local council adopted within the scope of its discretionary powers. The government office may investigate the lawfulness of the decision-making process of decisions made within the scope of discretionary powers.

The analysis of the effectiveness of legal supervision was supported by the report of the Baranya County Government Office[23], which was sent to me. The study analysed 60 local authorities of the 302 local governments of the county. More specifically: the office of the county general assembly, 5 mayors' offices and 54 joint local authorities. The study also analysed 264 nationality self-governments and 85 local authority associations. Accordingly, the number of users in the county, registered in the National Legislation Database's Written Correspondence Module for Legal Supervision, is high. The total number of individual partners using written correspondence for legal supervision is 409.

The government office's report investigated whether local government decrees had been submitted in time and whether the local government decrees had been uploaded in their consolidated versions through the relevant IT system. Currently, the National Legislation Database does not provide any information on decree publication dates. Although the designated rapporteur gets an email about the publication of new decrees and "as at" versions; these automatically generated emails, however, do not give proper grounds for the legal supervisory procedure, because the exact publication date should the known as well. The number of decrees uploaded to the National Legislation Database differs from the OSAP data[24] reported by municipal clerks. The number of uploaded decrees was 404 less than the reported figure in 2017; in 2018, the difference was 47. This difference is attributable to several things, in part to the data processing issues, in part to non-published decrees.

The report compared primarily the "as at" status data of the National Legislation Database's statistics with the total number of published decrees[25] included in Annex 1 of

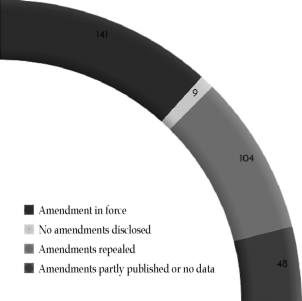

Figure 2[26]

this paper. It is likely that local governments the relevant figures of which were the same or showed only a minor difference met the deadlines and the obligation to disclose the consolidated versions of their decrees.

A question regarding the interpretation of the law came up during the preparation of the report: Are local government decrees that contain only amending provisions required to be disclosed on the National Legislation Database's site? Within the meaning of Section 12 and Paragraph (2) of Section 13 of the Legislation Act, amending decrees and repealing decrees become implemented with their entry into force, and implemented decrees become ineffective on the day following their implementation. Having regard to the fact that the disclosure obligation applies to decrees in force, some municipal clerks' interpretation of the law is that ineffective amending decrees are not required to be published.

Given this false application of the law in practice, the Government Office paid special attention to the local governments' publication of their amending decrees. Their investigation found that only 9 local governments did not disclose their amending decrees at all, 48 local governments disclosed them only in part, and the available data did not allow them to establish nonaction unequivocally. 104 local governments disclose their decrees containing only amending and repealing provisions, and

- 398/399 -

Figure 3[27]

they also repeal them according to the referred sections of the Legislation Act. The other 141 local governments disclose their amending decrees, but they fail to repeal them.

The investigation found that 42% of the local governments produced consolidated versions for all amendments. 89 local governments produced the "as at" status of the consolidated version in part and they correspond to 29% of all the local governments.

Consolidated versions are not published mostly after the amendments of budget decrees. Figure 4 shows the disclosure of the consolidated versions of decrees. In some cases, consolidated versions were not disclosed owing to the lack of knowledge to use the National Legislation Database site. Although the website of the National Legislation Database offers a detailed guide on generating the consolidated versions and "as at" versions of decrees, publication was still incorrect in several cases.

The investigation led to the issuing of 10 legality appeals. These legality appeals were based primarily on more material failures such as the complete non-disclosure of consolidated versions or the non-publication of several decrees. Given that a legislative provision leaves the responsibility for publishing local government decrees with the municipal clerk, the legality appeals were addressed to the relevant municipal clerk in all cases. The 10 legality appeals aimed at the elimination of

Figure 4[28]

failures to publish the decrees of 1 city's and 41 villages' local governments. Given that the relevant deadlines were later than the date of submission of the report, the legal supervisory procedures are still pending. The government offices do not use the legal supervisory tool for minor defects in decree publication. In our view, decree publication inconsistent with the National Legislation Database's user guide does, in itself, not give sufficient grounds for using the legal supervisory tool. The situation is similar when the municipal clerk does not upload the decrees text in an editable format but in a scanned or PDF format.

1. The legality appeal

If the government office becomes aware of a breach of law, it calls on the entity concerned to eliminate it by setting an at least 30-day time limit within the scope of legal supervision. The entity concerned is obliged to review the notification and inform the government office of its relevant actions or disagreement within the set time limit. If the time limit set expires fruitlessly, then the government office decides on applying other means of the legal supervisory procedure within the scope of its discretionary powers. There are two aspects to be considered: the first one is the earliest possible elimination of the breach of law, the second one is providing the entity concerned to eliminate the

- 399/400 -

unlawfulness with a sufficient amount of time. The legality appeal is further regulated by Government Decree No. 119/2012. (VI. 26.) on the Detailed Rules of Legal Supervision over Local Governments. The Government Decree allows the extension of the deadline, the ordering of which falls within the discretionary powers of the Government Office, the Office may however use it only if the person concerned has notified the Government Office of this intention in advance and in writing.

2. Initiating the convocation of the local council and its convocation in cases specified in this Act

The government office may initiate the convocation of the local council at the mayor if the discussion of legality issues by the local council is justified with a view to ensuring the legitimate functioning of the local government. In this special case, the government office may deviate from the rules laid down in the local government's organisational and operational rules in convoking the local council.

3. Initiating the review of the Constitutional Court if a local government decree is inconsistent with the Fundamental Law of Hungary; initiating a judicial review of the consistency of a local government decree with the law

If a local government decree is inconsistent with the Fundamental Law of Hungary, the government office initiates, through the minister responsible for the legal supervision over local governments, at the Government that the review of the local government decree by the Constitutional Court be moved for concurrently with sending a draft motion meeting the formal and substantive requirements laid down in the act on the Constitutional Court. The government office sends the motion to the local government concerned concurrently with the initiative sent to the Government. (initiative for moving for subsequent constitutional review) Within fifteen days counted from the receipt of the information sent to the local government or the fruitless expiry of the time limit open for providing information, the Government Office may suggest the revision of the compliance of the local government decree with the relevant piece(s) of regulation to the Curia (Supreme Court of Hungary).

4. Initiating the review of local government decisions by the regional court

The government office may initiate that the regional court reviews local government decisions. The regional court shall suspend the implementation of a decision, if the implementation of the unlawful decision of the local government would

(a) be materially injurious to the general interest, or

(b) entail unavoidable damage.

5. Non-fulfilment of the local government's obligation to make decisions or discharge responsibilities

Within fifteen days counted from the receipt of the information sent to the local government or the fruitless expiry of the time limit open for providing information, the Government Office may request the regional court to establish the non-fulfilment of the local government's statutory decision-making obligation and to oblige the local government to make the decision (by setting a deadline) or to establish the non-fulfilment of the obligation to discharge responsibilities (provide public services) and to oblige the local government to discharge such responsibilities (by setting a deadline). If the local government fails to fulfil its decision-making obligation within the time limit set by the court, then the government may, within thirty days following the lapse of the time limit, request the regional court to order the elimination of the nonaction by the government office at the cost of the local government.

6. Initiating the disbandment of the local council

The government office may suggest requesting the Government to disband local councils that operate inconsistently with the Fundamental Law of Hungary to the minister responsible for the legal supervision over local governments.

- 400/401 -

7. Initiating the withholding or withdrawal of assistance disbursed from the core budget

The government office may request the Hungarian State Treasury to withhold or withdraw the statutory part of the assistance disbursed from the core budget.

8. Filing a claim to terminate the position of the mayor

The government office may file a claim to terminate the position of a mayor who repeatedly violates the law.

9. Initiation of disciplinary action

The government office may initiate disciplinary proceedings against the mayor of a local government or against the municipal clerk at the mayor.

10. Initiating an investigation by the State Audit Office

The government office may request the State Audit Office to investigate the financial management of a local government.

11. Professional assistance

The government office provides local governments with professional assistance in matters falling within its scope of competence.

12. Legal supervision fine

The government office may impose a legal supervision fine on a local government (a) if the municipal clerk fails to fulfil his/her obligation to send minutes within the set time limit despite having been called upon by the government office to do so;

(b) if the mayor or municipal clerk fails to respond to the government office's request for information within the set time limit;

(c) if the regional court establishes that the local government has failed to fulfil its obligation to legislate, make decisions and discharge responsibilities (provide public services) and the time limit set by the court has lapsed fruitlessly;

(d) if the local council fails to conduct the disciplinary proceedings initiated by the government office against the mayor or the mayor fails to do the same against the municipal clerk within the relevant time limit.

Extent of the fine: The smallest amount per case of the legal supervision fine is the salary base of public officials; its highest amount per case is ten times as much as the salary base of public officials. Principles for imposing the fine: In imposing the legal supervision fine, the government office shall take into account (a) the gravity of the unlawful failure to fulfill obligation;

(b) the budgetary situation of the local government;

(c) the number and amount of previous fines.

The government office's decision on the fine is subject to the requirements of the Act on the General Rules of Administrative Proceedings and Service. Legal remedies: The local government may request the judicial review of the government office's decision on the fine within fifteen days counted from the communication of the decision. The regional court may change the decision of the government office; the government office may not be obliged to conduct a new procedure.

13. Establishment of the failure to fulfil the local government's legislative obligation and fulfilment of the legislative obligation

Informing the local government at the same time, the government office may request the Curia to establish the local government's failure to fulfil its legislative obligation, if the local government has failed to fulfil its statutory legislative obligation.

If the local government fails to fulfil its legislative obligation within the time limit set by the Curia, then the government may, within thirty days following the lapse of the time limit, request the Curia to order the elimination of the nonaction by the government office. The head of the government office adopts the decree in the name of the local government and under the regulations applicable to the local government decree; under the condition that the head

- 401/402 -

of the local government signs the decree and it has to be promulgated in the Hungarian Official Journal." The government office sends the promulgated decree to the local government. The municipal clerk arranges for the disclosure of the promulgated decree according to the rules laid down for the promulgation of local government decrees in the organisational and operational rules. Decrees adopted by the head of the government office in the name of the local government decree are local government decrees as meaning that the local government may amend and repeal them only after the next municipal elections, and the head of the government office may amend them during the time until then.

It may be concluded that the process of decree-making is quite complex and the supervision over it can make a great impact on it nowadays, as we can meet unmindful legislators rarer, although legal supervision has also not created perfect and flawless local legislation, we can still meet decrees that are unclear-either or both formally and substantively-, uninterpretable, their elimination is however of key importance, as the potential unmindfulness, technical imperfections of the legislator may cause that both the legal practitioner and the person(s) to whom the law applies suffer negative consequences, they might experience injustice, the result of which might be legal uncertainty. It is not perfectly implemented even despite the existing legal supervision; the resolution of the problems is, however, proceeding towards the right direction. The legal supervisory procedure may be divided to two distinct milestones and their detailed rules are laid down in Sections 1 and 2 of Government Decree No. 119/2012. (VI. 26.). According to Paragraph (1) of Section 1 of that Government Decree, the supervisory procedure starts with an investigation that is started either by the government office on its own motion or upon notification. The scope of the investigation of the government office is specified in Paragraphs (3) to (5) of Section 132 of the Local Government Act. If the government office does not detect any breach of law, then the procedure is closed without a separate decision. It must be pointed out that the government office may re-investigate previously investigated local government measures. Investigation is followed by action if the government office finds a breach of law associated with the local government's measures or the entity concerned does not respond to the government office's request for information. Within the meaning of Paragraph (4) of Section 2 of the Government Decree, if the legality appeal does not yield any result, then other legal supervisory tools may be used, and more tools may be used as long as the breach is eliminated.

VI. Analysis of the promulgation of local decrees

One of the most important criteria of the application of the law, that the legislator determines what will be applied and until when, and that whatever has been rescinded, it should not be applied any more. The question of the starting date of the applicability of a decree is answered by the date of promulgation, having regard to the period required for the preparation. Paragraph (3) of Section 2 of the Legislation Act reads: "The date of entry into force of a law must be set in a way leaving time enough to prepare for the application of that law"[29]. This provision is especially important when a decree imposes a detrimental legal consequence on the entities concerned. For instance, it imposes higher taxes on the residents. The 30-day time limit is statutorily regulated, and the relevant provision lays down that "At least 30 days must pass between the promulgation and entry into force of a legal regulation establishing payment obligation, extending the scope of entities obliged to pay, increasing the burden of the payment obligation, terminating or restricting benefits or exemptions."[30] This is exemplified by Local Government Decree No. 15/2016. (XII. 30.) of the Local Council of the Village of Pázmánd on local taxes[31] with only 15 days between promulgation and entry into force, not 30. Another example is the Local Government Decree No. 7/2018. (VIII. 30.) of the Local Council of the Village of Kulcs on local taxes[32] with only one day between promulgation and entry into force. It may be concluded that the time necessary for the preparation for the application of this piece of legislation

- 402/403 -

has not passed. The Legislation Act does not prohibit entry into force on the date of promulgation, but it sets out that the date of entry into force must be given as the hour in this case. The decree of Diósjenő[33] for instance, lacks the final provision and the date and time of promulgation and entry into force of the decree. The Decree of Mátraszele indicates the promulgation as follows:"Section 6 (1) This Decree shall enter into force on the date following its date of promulgation. (2) The municipal notary shall procure that this Decree is promulgated."[34] In this case, the date of adoption and the date of promulgation are not specified, which makes the date of entry into force unclear. Several local governments legislate with similar specificities.

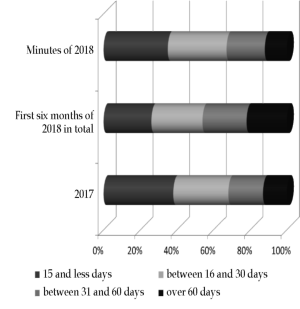

Decree No. 23/2012. (IV. 25.) of the Minister of Public Administration and Justice lays down the following. "Section 2 The municipal clerk shall send the minutes of the sitting of the local council of the local government, the committees, associations of the local council as well as that of the council of the partial local government to the government office via the designated IT system of the provider of the National Legislation Database within 15 days following the sitting."

The diagram shows minutes received after the deadline in 2017 and 2018. 34% of all the submitted minutes were received within 15 days, 29% were received in 30 days. Another

Figure 5[35]

21% were submitted within 60 days. 16% had a more serious failure, with a delay over 60 days. The government office paid special attention to the submissions of local governments identified by the audit after the period under investigation. If no improvement showed even despite the legal supervisory actions, then further means were used on the basis of the assessment of the annual work. The investigation resulted in 204 legality appeals, 9 requests for information and professional assistance in 22 cases. 2017 saw, outside the investigation, another 77 legality appeals with the same subject area. The failures are being eliminated continually, according to the report.

VII. Summary

The foregoing allows the conclusion that legal supervision aims at ensuring the lawful operation and decision-making of local governments and at the earliest possible elimination of breaches of law by the entities concerned upon legality appeals. Experience gained from the previously abolished and further developed institution of legality review show that the right to review is not enough for accomplishing the goals; more intensive means, i.e. supervision, were, therefore, necessary. We can also conclude that the legislator's purpose with the newly introduced supervisory means, including the supervisory fine, was to give more means to government offices to eliminate breaches of law as soon as possible. In my opinion, the introduction of these new tools was vital, because they make lawful operation and decision-making much more likely. The conclusion is that the legal supervisory procedure became regulated, because the government offices have got much stronger and more efficient powers than the previous review responsibilities and competences. This also improved compliance with the time-limits for sending minutes, which allows the soonest possible rectification of breaches of law. Experience gained from the restructured review system, however, show that local legislation requires continual revision, in which the government office, acting in its legal supervisory powers, could support the local government.

- 403/404 -

As regards the minutes of committees and associations, the legality appeals and requests for information drew the attention of municipal clerks to these failures, which occurred quite frequently. The minutes were drafted in time on countless occasions; submission did, however, still not take place.

As regards decree publication, non-fulfilment of tasks are mostly based on the lack of technical knowledge and information, which is being reduced through the advisory activities of government offices. Intense communication developed among municipal clerks and territorial rapporteurs in this subject-more specifically, the legal issues of disclosure and the operation of the site. This is absolutely positive and demonstrates the progress and quality of legal supervision.

Annex No. 1

| Mu- nici- pality | Decrees | "As at" versions | |||||

| Pub- lished | Total | Pub- lished | Publi- cation pending | Under draft- ing | Not enter- into force | Total | |

■

NOTES

[1] This paper has been made within the framework of the programmes initiated by the Hungarian Ministry of Justice to raise the standard of legal education.

[2] It was the seat of Ugocsa County, which now belongs to the Ukraine.

[3] The National Assembly of 1514 adopted it and the king signed it; the barons of the King's Council, however, did not want to involve the gentry into governance; it did, therefore, not became the law of the land. Werbőczy then issued it in Vienna at his own cost and sent it to the counties where the courts started to apply it. The Tripartium is a major collection of Hungarian customary law and was used up to 1848.

[4] Adrián FÁBIÁN: Az önkormányzati jogalkotás fejlődése és fejlesztési lehetőségei. [Development and development opportunities of local legislation] (doctoral dissertation) page 33

[5] Adrián FÁBIÁN: i.m. 36

[6] Section 2 of Act XLII of 1870

[7] Section 5 of Act XLII of 1870

[8] Section 29 of Act XVIII of 1871

[9] Section 8 of Act XXI of 1886

[10] Section 33 of Act XX of 1901

[11] Gyula KOI: Jogalkotásunk szabályozásának fordulópontjai. [Turning points of the regulation of our legislation] page 74

[12] Section 31 of Act XX of 1949

[13] Paragraph (2) of Section 16 of Act LXV of 1990 on Local Governments (hereinafter referred to as Local Governments Act)

[14] Paragraphs (2) and (3) of Article T of the Fundamental Law of Hungary (25 April 2011)

[15] Paragraph (2) of Article 32 of the Fundamental Law of Hungary (25 April 2011)

[16] Paragraph (5) of Article 32 of the Fundamental Law of Hungary (25 April 2011)

[17] Paragraphs (2) and (3) of Section 51 of the Local Governments Act

[18] László TRÓCSÁNYI and Balázs SCHANDA: Bevezetés az alkotmányjogba [Introduction to Constitutional Law]. Az Alaptörvény és Magyarország alkotmányos intézményei [The Fundamental Law and the Constitutional Institutions of Hungary]. page 72

[19] Government Decree No. 338/2011. (XII. 29.) on the National Legislation Database

[20] Point (b) of Paragraph (2) of Section 6 of Act CXXX of 2010 on Legislation

[21] Paragraphs (4)-(5) of Article 32 of the Fundamental Law of 2011

[22] Paragraphs (1)-(2) of Section 136 of Act CLXXXIX of 2011 on the Local Governments of Hungary

[23] Work Plan Task Report, minutes and decree submission

[24] National Statistics Data Recording Programme

[25] Annex 1

[26] Baranya County Government Office Work Plan Task Report, minutes and decree submission, page 4

[27] Baranya County Government Office Work Plan Task Report, minutes and decree submission, page 5

[28] Baranya County Government Office Work Plan Task Report, minutes and decree submission, page 6

[29] Paragraph (3) of Section 2 of Act CXXX of 2010 on Legislation

[30] Section 32 of Act CXCIV of 2011 on the Economic Stability of Hungary

[31] http://www.njt.hu/njtonkorm.php?njtcp=eh6eg5ed-0dr5eo0dt3ee6em3cj0by9bw6ca1cc4cc5ca6d

[32] http://www.njt.hu/njtonkorm.php?njtcp=eh1eg2ed-9dr4eo9dt2ee1em6cj5bz2bx3by2ce5cd4bz1f

[33] http://njt.hu/njtonkorm.php?njtcp=eh5eg2ed9dr4eo3d-t6ee7em2cj3cd2cd9cb6ce7ce0i

[34] http://njt.hu/njtonkorm.php?njtcp=eh5eg4ed5dr2eo9d-t6ee1em0cj5by6by3cf6cd9cb2cb5l

[35] Baranya County Government Office Work Plan Task Report, minutes and decree submission, page 20

Lábjegyzetek:

[1] The Author is Doctoral Student, Doctoral School of the Faculty of Law at the University of Pécs.