Prof. Dr. habil. Marian Malecki PhD[1] - Dr. habil. Orsolya Falus PhD[2]: On the Updated EU Honey Directive 2024/1438 - from the Spectacle of a Polish and a Hungarian Legal Historian (JURA, 2025/1., 136-149. o.)

"Eat honey my son, because it is good"

Holy Bible, Proverbs 24: 13

(Motto)

I. Introduction

The European Union is the world's second largest honey producer after China. Production, however, does not cover demand: hundreds of tons of honey are imported into the EU, mainly from China, which accounted for about 40 percent of EU imports. Compared to other competitors, EU beekeepers face relatively high production costs, and limited EU exports are priced higher than EU imports.[1] While the EU beekeeping sector is small, it is important for agriculture, food security and biodiversity, as bees pollinate crops and wild plants. Profitability is crucial for the sustainability of the apiculture sector. Outbreaks of animal diseases, intensive agriculture, exposure to chemicals, as well as habitat loss and adverse climatic conditions can also threaten the productivity of beehives. By the beginning of the 21[st] century, the sector is struggling with many difficulties.

The European Parliament thus called on the European Commission and EU countries to develop new measures to protect bees and help beekeepers. In particular, the representatives called for better protection of bee species, greater financial support for beekeepers, as well as a ban on harmful pesticides and action against the importation of fake honey. World competitors with lower production costs and cheaper prices represent a threat to EU producers' market share. Furthermore, a control plan organised recently by the European Commission has highlighted illicit practices as adulteration of honey with sugar carried out both in and outside the EU. Non- compliance with EU rules on production standards, and false labelling affect beekeeper income and have triggered a call from producers for broader checks to secure fair competition on the EU market. In its role as co-legislator, the European Parliament has adopted a number of measures promoting EU beekeeping. The 2013

- 136/137 -

reform of the CAP addressed concerns expressed in a number of Parliament resolutions on bee health and the situation of beekeeping (20 November 2008, 25 November 2010, 15 November 2011), while an own-initiative report (2017/2115 INI) tabled by the rapporteur Norbert Erdős (EPP, Hungary) on prospects and challenges for EU beekeeping is currently under deliberation.[2] The European Parliament called on the Commission and the Member States to provide support for the EU apiculture sector via strong policy tools and appropriate funding measures corresponding to the current bee stock. It proposed, therefore, a 50 % increase in the EU budget line earmarked for national beekeeping programmes. The Parliament also called on the Commission to promote and boost European beekeeping research projects and suggested broadening and sharing beekeeping research topics and findings. Members suggested that greater private and public investment in technical and scientific know-how is essential and should be incentivised, at national and EU level, in particular on genetic and veterinary aspects and the development of innovative bee health medicines. They also called on the Member States to ensure appropriate basic and vocational training programmes for beekeepers. The resolution highlighted the need for the EU to take the necessary and immediate steps to implement a long-term and large-scale strategy for bee health and repopulation in order to preserve the declining wild bee stock in the EU. The Commission is called on to ensure that honey and other bee products are considered as "sensitive products" in ongoing or future negotiations for free trade agreements, since direct competition may expose the EU apiculture sector to excessive or unsustainable pressure.[3] The revised EU Honey Directive (2024/1438) has come into force on 13 June 2024.[4] According to it all honey marketed in the EU must comply with the quality and labelling rules in this directive which sets out the definition and composition criteria for honey and other rules, in particular it provides for mandatory origin labelling for honey. From 2026, the countries of origin in honey blends will have to appear on the label in descending order with the percentage share of each origin. EU countries will have the flexibility to require percentages for the four largest shares only when they account for more than 50% of the blend. It empowers the Commission to introduce harmonised methods of analysis to detect honey adulteration with sugar. It confers powers to the Commission to adapt the composition criteria for honey to ensure that it is not overheated, pollen is not removed from honey, and the methods are put in place to trace its geographical origin, including exploring the feasibility of EU-wide traceability system from beekeeper or importer to the final consumer. All countries of origin will have to be indicated on the label of honey mixtures in descending order according to the indication of the exact percentages. Under the current EU rules, honey pots must show the exact country of origin if the honey comes from one country. However,

- 137/138 -

this is not the case for blends containing honey with different origins, making it hard for consumers to know the true origin of honey. Labels either include: "blend of honey from EU and non-EU countries", "blend of honey originating from the EU", or "blend of honey not originating from the EU". In addition, additional measures will be available to the national authorities. According to this, for example, in the case of packages smaller than 30 grams, the name of the country of origin can be replaced with a two-letter ISO code. Mandatory origin labeling with an exact percentage can effectively supports the combat against honey of uncertain origin and dubious quality from outside the EU.[5]

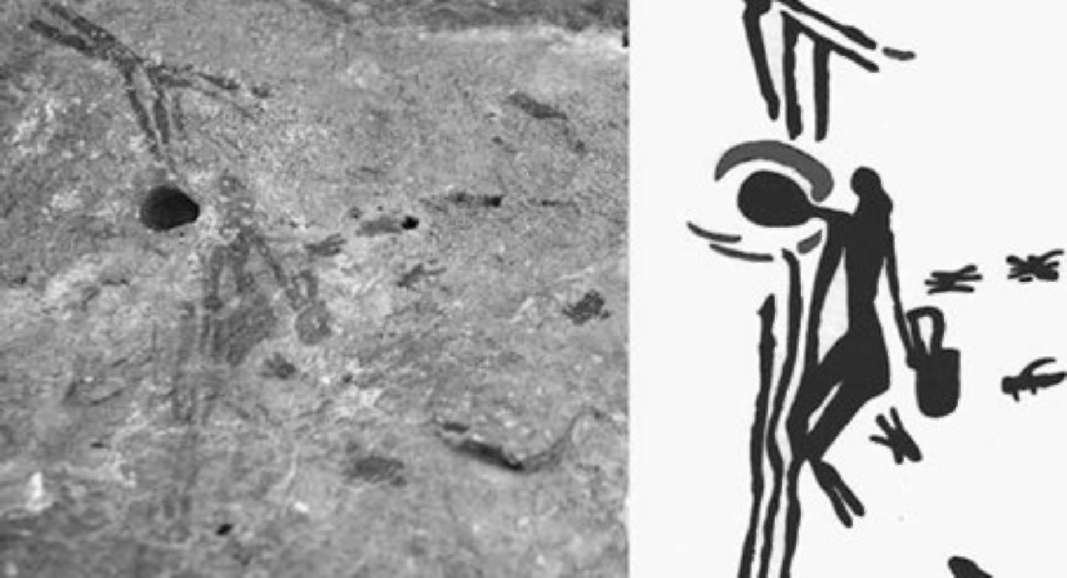

The sector and its regulation have roots that are almost as old as human culture, reaching back into the past. The honeybee (Latin: apis mellifera) as a species probably evolved 8 to 30 million years ago, so it can be considered a relatively young species. The human utilization of honey produced by bees is as old as humanity itself. Beekeeping, the collection of honey, and its use for food and medicine dates back to antiquity. Honey is the natural sweet substance collected by bees from plant nectar or live plant juices or from selected material from living parts of plants by insects that absorb plant sap, which the bees collect, transform by adding their own substances, store, dehydrate and ripen in honeycombs. Man knew and consumed honey as early as the Stone Age. This is evidenced by a 8,000-year-old rock drawing in in the Cuevas de la Araña (English: Spider Caves) in Valencia, Spain situated on the river Cazunta depicting a man collecting honey from a honeycomb: a honey hunter (Figure 1).[6]

Figure 1 - Rock painting of honey Hunting at the Araña Caves in Valencia, Spain (Turismo Comunidad Valenciana)[7]

- 138/139 -

Honey thus obtained was the only sweetener at the time. It was also used as bait for bear hunting. The Old Testament also writes about keeping bees and harvesting honey. According to St. Augustine, honey indicates the tenderness and goodwill of God. As stated in Surat An-Nahl (16:68-69) of the Qur'an bees were commanded to eat the fruit and make honey, which has a healing effect on humans. Honey production is an integral part of the Hungarian and Polish culture as well. This paper aims to present the beginnings of its legal cultural history in Hungary and Poland - as EU's leading honey-producing countries - in order for today's legislators to see: honey production has been considered an important agricultural sector throughout the ages, and the value of honey in the centuries of the Middle Ages and early modern times was even higher than it is today. Accordingly, the producers of the sector were able to effectively represent their legitimate interests in all branches of law for the sake of a sustainable legislation.

II. The Legal Cultural History of Honey Production in Hungary in the Middle Ages and Early Modern Times

The Thracians were engaged in beekeeping even before the Hungarian conquest of the Carpathian Basin (cc. in 895-896). Our ancestors initially obtained honey by plundering wild bee colonies.[8] Robbery of bee colonies was enough at the beginning, however, the rapidly growing demand could not be met by this, and bee colonies were also ruined. After the conquest, with the spread of the Christian faith - The actual conversion of the country and its ecclesiastical organization was the work of St. Stephen, son of Duke Géza, who succeeded his father in 997 - there was an increasing need for beeswax candles in churches.

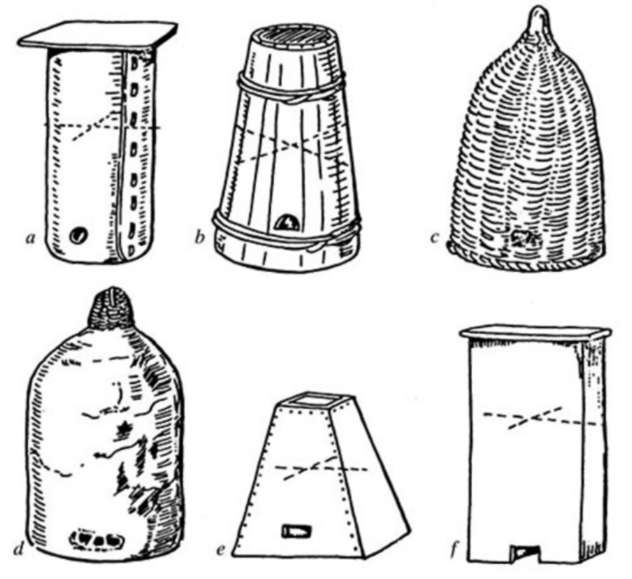

Beekeeping did not develop much in the Middle Ages. Presumably, in the beginning, bees were not kept around the house and were not cared for separately, but wild bees farmed in the woods were looted. For this the so-called bee bone or honeycomb was used. The device was made of ox horns and the bees captured in it were released one by one and followed in the footsteps of the beehive. Later, the bee colony in the tree litter was probably taken home with the tree stump. In Hungary, the first reliable data on forest beekeeping can be found in a Transylvanian document from 1355, according to which the forest of the bishop of Várad bees were bred in places called "Méhlő".[9] Artificial beehives were made for the swarms, imitating the original wooden path with a carved tree trunk. It is certain that bees have been kept around the house since the middle of the 11[th] century, because in 1055 King Andrew I (r. 1046 - 1060 ) counted the bees per hive.[10]

Figure 2 - Traditional medieval Hungarian beehives[11]

From the 11[th] century through the Middle Ages, the data of numerous documents and historical records testify that the Hungarians who settled

- 139/140 -

in the Carpathian Basin were engaged in beekeeping. Hungary's first king, St. Stephen I (r. 1001 - 1038), already ordered in his donation letter 1019 that the abbey of Zalavár should not be disturbed by its lands, vineyards, fishing and beekeeping.[12],[13] At that time, the abbey also received twelve pounds of wax a year from the Drava region. Hungary's monasteries were large beekeepers in the time of the Árpáds, the first ruling dynasty of Hungary from 1000 to 1301, named after their ancestor, Árpád, head of the confederation of the Hungarian tribes at the turn of the 9[th] and 10[th] centuries. Beekeepers are often mentioned in old documents as a separate class (Latin: apes custodes, curatores apiarios, apiarii or mellidatores). According to the founding diploma, already in 1015, among the staff of the Benedictine monastery of Pécsvárad[14] we find 12 beekeepers, a wax maker (Latin: cerearius), and a gingerbread maker. King Andrew I (r. 1046 - 160) donated two beekeepers and 50 hives to the Tihany abbey,[15],[16] while according to the 1075 decree of King Géza I (r. 1074 - 1077) the village of Ártánd was obliged to give annually 12 five-year-old pigs, 12 akos (~1 ton) of honey, and 2 horses each in winter and summer to the Garamszentbenedek abbey: "quorum servitus sit dare omni anno XII porcos Vannorum et XII modios mellis [...] et tam estate, quam hyeme duobus equis abbati semper servire".[17] From the 13[th] century, the ecclesiastical owners collected a bee tithe from their serfs.[18]

Until 1370, royal beekeepers lived in Baranya county in possession of the Bodvölgy valley passion. With the immigration of the Saxons to Szepes (now: Spią, Slovakia) and Transylvania, the industries processing raw bee products also began to flourish, such

- 140/141 -

as wax makers (Latin: cerarii), beekeepers and honeymakers. In 1370, the Saxons of Nagyszeben (now: Sibiu, Romania) obtained an exclusive patent from King Louis I the Great (r. in Hungary 1342 - 1382) to sell wax with the seal of their town on the market in Székesfehérvár. He extended this patent to 1374 in Brasov (Hungarian: Brassó; German: Kronstadt - now: Braşov, Romania). They could also sell or exchange their wax cakes at the market in Székesfehérvár, and if their stock was not sold there, they could take them further, and they really traded in Venice as well.[19] The medieval Hungarians consumed a lot of honey, but they even sweetened their wine with honey many times, and also liked beers. Wax candles were usually used in the divine service, these were sacrificed in memory of the deceased, wax seals were applied to the diplomas, all of which increased the high demand for wax. It also played a major role in the waxing church bureaus, in gaining mastery, and in the life of guilds in general. Churches, guilds, often imposed punishment on the perpetrators of minor transgressions in wax. For failing to visit the services, Roman Catholic believers responded by supplying a certain amount of wax candles. On the occasion of his inauguration as a master, new members of the guild donated wax candles to the guild. The importance of beekeeping in the Middle Ages is also indicated by the certificates that contain data on the use of wax in the discussed period. The huge consumption of wax in the Middle Ages is also shown by the fact that when King Matthias I (r. 1458 - 1490) was visiting Archbishop Hyppolit of Esztergom in 1487, 300 wax candles were bought to illuminate the castle. The construction and illumination of the splendor of the royal palace did not only represent the usual generosity, but Matthias used all this to strengthen his royal authority, to express his power and dignity, since this was the only way he could compete with the prestigious ruling dynasties. In addition to wax candles, wax was also needed to make seals for sealing various official letters. The seal was made in melted wax with the seal press -however, not everyone had the right to do so, they were authenticated by royal secretaries and in official chancelleries. Honey is also mentioned among the salaries of village priests.[20] The continuously developing beekeeping over time is also proven by the data, according to which medieval Hungarians used a lot of honey and honeydew to prepare their favorite drink, mead beer. Mead was also often included as a serf's service. The serfs of the 13 villages of the Dömsöd rectory, for instance, paid a total of 175 casks of mead per year to their landlord based on the property census of the Pannonhalma Benedictine Abbey between 1237 and 1240.[21]

Honey and wax were very important in the folk household as well. Significant amounts of honey were consumed for nutritional and nedical purposes. György Lencsés's Hungarian manuscript book from the end of the 16[th] century recommends honey for the treatment of various diseases.[22] Also significant amounts of honey were needed to make gingerbread from the

- 141/142 -

Middle Ages to the early 19[th] century. There was a flourishing gingerbread industry in Hungary in the middle of the 14[th] century, but the monasteries already had gingerbread makers. Gingerbread made in Transylvanian cities in the 16[th]-17[th] centuries. century was a favorite delicacy not only of the Transylvanian princes but also of the Turks during the Ottoman rule in Hungary between 1541-1686.[23]

During the 13-15[th] centuries there were Hungarian villages in which the king's beekeepers lived. Some village names - as Méznevelő (now: Medovarce, Slovakia), Méhész (now: Včeláre, Slovakia), Méhkerék, and Méhesfalva (now: Pčoliné, Slovakia) - prove that the population was a beekeeper before or was mostly engaged in beekeeping.[24] The Hungarian word "méz" in English means honey, and the Hungarian expression "méh" in English means bee.

Bees played a prominent role in the collection of the priestly tithe and the noble ninth, the latter only in the 18[th] century terminated. During the Ottoman rule in Hungary the taxation of honey took great proportions. In Baranya county, for example, a significant portion of the tax was collected in honey, and it was not infrequently added to the imperial taxes.[25] After the bees, until the end of the 18[th] century, the Church, the king, and the landlord collected honey-, honeybeer- and wax-taxes from the serfs. As early as 1121, in the village of Páka (Zala county, Hungary), 6 tortillas waxes had to be delivered to the Church for each house.[26] It is characteristic of the value of honey that in the 11[th] century, in 1067, approximately a cart of shingles was added for 10 liters of honey. Later - in the middle of the 16[th] century - a Christian prisoner could be bought for 1 liter of honey on the Turkish market in Buda.[27]

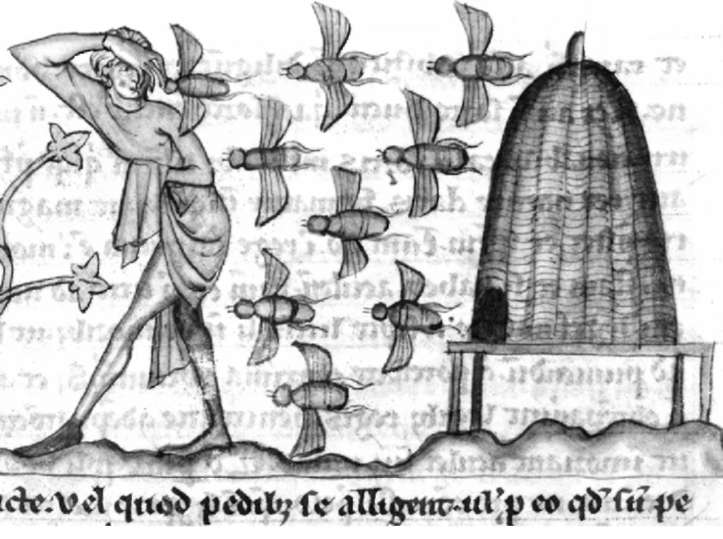

Figure 3 - Bees in military defense. (De Natura animalium, Cambrai ca. 1270 Douai, Bibliothèque municipale, ms. 711, fol. 37 r.)

- 142/143 -

Bees were used in 14-17[th] century military technology as well. At the city besiegers, the defenders threw piles full of bees among the besiegers. This way of defending the castle has been preserved to this day by some Transylvanian legends. The tradition of the court remembers the beehives thrown at the forcibly converting Jesuit monks.[28]

The situation of Hungarian beekeeping during the 150-year rule of the Turks did not change significantly. At the Sultan's command, no one could disturb the honey merchants. Thus, in 1625, nearly 900 tons of Hungarian honey were exported to Vienna. Recognizing the importance of honey, Sultan Suleiman I (r. 1520 - 1566) imposed huge taxes on bee colonies. In the middle of the 16[th] century a significant amount honey, but mainly wax was exported to Poland, Austria, and Venice.[29] Hungary's oldest beekeeping book, published in 1645 in Nagyvárad (now: Oradea, Romania) by Miklós Horhi, the chief beekeeper of György Rákóczi, dates from this time.[30]

Bees stealing, spoiling bees, were severely punished. In 1556, a serf who hid the stolen bee in the attic was sentenced to undress naked to the waist and the bees were covered on his head. In Bártfa (now: Bardejov, Slovakia) in 1569 a woman was burned at the stake for stealing honey and damaging bees. The bees and honey thieves were punished with similar severity by the Cheremises, Estonians, and Poles, as well.[31]

III. The Outline of the Starts of Apiarian Law in Poland

Beekeeping and the subsequent benefits have been in the centre of legal attention since the beginning of Polish statehood up to the present day. In the Old Polish language, the beekeeping law was known as obelny law. It concerned the use of beehives, but also the legal obligations between beekeepers and forest owners. In particular, the apiarian law regulated the following: the system of the so-called beekeeping fraternities; the duties of beekeepers; the inheritance system; and the criminal cases involving beehive theft. For this purpose, a special court was established in Mazovia. It consisted of the starost (English: mayor) - referred to as a judge of the beekeeping law - and six jurors selected by the beekeeping community amongst the habitants of a nearby town or village. There were attempts to unify beekeeping courts. From the 17[th] century onwards, the beekeepers' farms were controlled by a beekeeper, a judge and a magistrate, and crimes were punished severely - as mentioned below - including capital punishment.

The origin of the term obelus is not yet known, although the Polish ethnographer Zygmunt Gloger in his Encyklopedia Staropolska (English: The Old Polish Encyclopaedia) suggested the origin of the term derived from a spit, spear or an arrow.[32] The name likely referred to the people known as osocznicy, i.e. hunters who surrounded the large game in the forest with a whole group and spears in their hands.

- 143/144 -

Apiarian law was regulated in the Statutes of King Casimir the Great (r. 1333-1370) and was developed in particular in the 15[th] century, although it was still changing later on, especially in some regions of Poland, such as Masovia, the Sandomierz Country, Podkarpacie and the Tuchola Forests. In the early modern period, the use of beehives constituted a piece of land, usually granted in perpetual ownership. This is related to the placing of bee hives on forest trees, which applies to the property. Obviously, the owner of the property had no right to set up an apiary next to the house. In the Middle Ages however, for example, in Masovia, it was a monarch's priority, jura regalia. This was because the dukes of Masovia used to seize the revenues from the beehives and the associated rights for themselves. Later, after the incorporation of Masovia to the Polish Crown (1529), the execution of the apiary law was entrusted to royal beekeepers. According to preserved historical records, the lucrativeness of the regalian rights led to numerous abuses, and this, in turn, led to changes in the law and its tightening. During a session of the Sejm in Piotrków (1538), regulations were introduced according to which royal beekeepers could no longer collect honey from beehives belonging to the gentry.[33]

The concept of the beekeeping regalia was introduced by Polish prewar scholar Józef Rafacz. According to him "beekeeping regalia should be understood as the ruler's right to keep beehives on his private estate and profit from them. The rights of the landowner, on the other hand, were limited to the free use of the property. At first, the donation of regalia had to be explicit, but later in the 16[th] century it was considered implicit".[34]

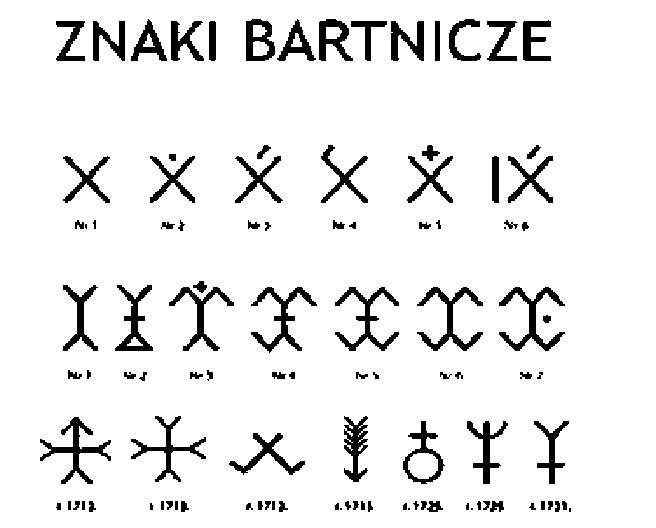

Wild beehives were usually built in forests: on pine and oak trees, less frequently among firs and ash trees. From court records of 1523 we learn that the court usher "omnia et singula arbora quercorum et pinatica ecavata per mellicidas omnes ducales (...) exclamavit et inhibuit".[35] Such trees could not be burnt or cut down under penalty of a fine called '50'". The royal beekeeper was allowed to inspect the beehives, and the 'right to the beehives' could be either permanent or temporary. He was usually subordinate to the land court clerk of the given district and -as the ruler's representative - could collect tribute from honey producers. The royal beekeeper was also in charge of rationing apiary equipment, even in noble estates. For this purpose, in Masovia, the vice-mayors and caretakers of beekeeping used to confiscate illegal or forged tools.[36] The basic beekeeping unit was the so-called bór (Latin: mellificium), or obelstwo, which included 60 beehives, i.e. 60 trees with bees. However, it was possible to sell individual parts (e.g. half of the bór, or even one beehive). The trees were marked to determine the ownership of the particular beehives. If there was a new buyer, the old mark was removed and a new one placed in. If a beehive was mortgaged (as a pledge), two symbols appeared on the tree.[37] Occasionally beehive trees two marks appeared in the records.

- 144/145 -

In case of a conflict, the mark was being cut out of the tree and examined for its depth based on the tree rings. The symbols were mainly lines or combinations of lines, mostly crosses and their variants: Latin, St Andrew's, slanted etc., and circles and their combinations. Far less common were numerals (e.g. Latin), letters such as "C", "D" and even knight's crests like Osmoróg coat of arms.[38] The owners of the beehives were most often men, though of course, less often, also women.[39] As an example, in 1507, Marek Pieczonka from the village of Rudno bequeathed bee hives to his daughter Dorota.

Figure 4 - Beekeepers marks. Collected by Łapczyński, J. "Harvesting Honey in Kurpie"[40]

Many Polish legal acts regulated the beekeeping law. In the Middle Ages and the early modern period there were the Statutes of Casimir the Great (starting in 1347); the Statute of Warsaw (1401); the Statute of Warka (1420); the Armenian Statute (1519); the Three Statutes of Lithuania (1529, 1566, 1588); and the beekeeping law for the county of Przasnysz (1559). In addition to legal rights issued by the state, beekeeping was regulated by lords in their private estates. For example, in 1614, the voivode of Poznan, Ostroróg, regulated the beekeeping matters on his estate, Komarne.

The regulation of beekeeping law in the modern period was presented by Adam Antoni Kryński in his work Porządek prawa bartnego dla starostwa łomżyńskiego z 1616.[41] According to literary sources, the 17[th] century, and a bit earlier, was the golden age of beekeeping in Poland. Polish monarchs granted numerous privileges to beekeepers, which included the possibility of gouging beehives (in Polish referred to as "dzianie") and owning meadows and forests. The most important regulations on apiary law were "Prawo bartne bartnikom należące", published in 1559 by Krzysztof Niszczycki,[42] and the

- 145/146 -

aforementioned "Porządek prawa bartnego",[43] written by Stanisław Skrodzki. Apiculture developed most strongly in Mazovia, as the conditions in that area were more favourable, and the concentrations of bees were much better.

Beekeepers were a social group that was particularly protected by contemporary law. According to the III Statute of Lithuania (1588), a murder of a beekeeper was punished with a fine (Polish: główszczyzna) of 40 threescore of groschen, and in case of injury, compensation (art. XII. 3). Based on the Mazovian regulation local beekeepers created their own self-government, which was headed by the beekeeper starost who was subordinate to the royal starost (castle town starost) and his deputy was the beekeeper's assistant. The beekeepers convened separate sejmiki (English: regional assemblies), created the clerical staff and established and managed the beekeeping books. They were self-sufficient, creating not only the administration but also their own treasury. At the same time they were obliged to provide the so-called honey tribute, which was precisely defined by the specific duties of beekeepers. The measure of honey was rączki, i.e. from 5 to 15 pots.[44] After the death of their companion, they used to take care of orphans by appointing a legal guardian who was obliged to report annually on their activities. In case of any damage, he had to compensate the wards. The succession order in beekeeping estates was also different from the land law. The legislation aimed at making the estates indivisible; however, there were attempts to exclude women from the succession, as they were considered incapable of running a beekeeping farm.

The pre-war Polish historian, Przemyslaw Dąbkowski, wrote "if therefore, after the death of a beekeeper there remained sisters alongside with brothers, the brothers would take the entire homestead, and the sisters would be entitled only to compensation, while those daughters who had already been furnished by their father were not entitled to any repayment. If the sisters were left alone, the homestead was taken over by the eldest married sister, whose husband took care of the farm, while the younger sisters had to make do with the allowance. If there were only unmarried sisters, the homestead was presumably taken over by side relatives. When a beekeeper died childless, the farm would pass to the beekeeper's relatives; the widow was obliged to let them have the homestead without any difficulty. The second principle of the beekeeping law of inheritance was the pursuit of singular succession. If there were several sons left after the beekeeper, the homestead was not divided into parts, but it was passed to the brother who knew the beekeeping trade, while other brothers were to be paid off. Also, the father was allowed to pass the beehives to one of his sons, leaving the other sons out, and such a paternal disposition could not be violated by anyone after the father's death."[45]

In the 18[th] century, the importance of beekeeping declined, and in the draft of Andrzej Zamoyski's Collection of Judicial Rights (1778),[46] there was no longer any mention of a separate regulation for this area. It, however, should be noted that beekeepers were usually involved in handicrafts or other agricultural work on a daily basis. The dy-

- 146/147 -

namism of beekeeping organizations survived the partitions of Poland, as the records were still kept in Jedlnia near Radom in 1835. There were also recorded crimes committed on beehives. The punishment for counterfeiting honey (e.g. July honey) was fined, with payment in honey or money (e.g. the penalty of "30" - meaning thirty fines). Acts causing damage to beekeepers, such as destroying melliferous meadows located in the vicinity of beehives, were punished with similar financial penalties, while theft of beehives was severely and cruelly punished. The perpetrator's belly button was being cut out, nailed to the hive or a tree, and the unfortunate individual's innards were wrapped around it. In modern times, in Miechów, near Krakow, one such honey thief was caught. He came from central Poland (near Łęczyca), named Paweł Jadamczyk, who, during the inquisition process, additionally confessed to stealing horses. As it was stated in the sentence - the executioner was to behead him when "he begins to lose his strength". The justification set in the decree was quite interesting. The convict was accused of "not remembering, for the glory of God, which worms do it".[47] As noted by Marian Mikołajczyk, a bee is the only animal in the world that passes away but does not merely die (Mikołajczyk, 1998, p. 36).[48]

IV. Conclusions

The importance of bees' protection and consequently the world as a whole is indisputable. If there are no more bees, there will soon be no more people.

Thus in every geographical latitude, these unusual and fascinating creatures should undergo particular attention and care.

As can be seen, it has been a peculiarly important branch of production for Poland and Hungary since the medieval times. This is also proven by the fact that according to the sources the theft of honey has been regulated everywhere with cruel penalties for general deterrence. The contemporary documents show the high value of honey and the honey-producing sector in the legal historical eras examined in both countries. Considering the detail of the regulations and the special marking system used in Poland, as well as the fact that special statutory elements of honey theft were codified in medieval Central European criminal law indicates that in this area beekeeping was considered a particularly developed production sector, whose representatives were able to effectively represent their producer interests in the judicial system.

This lesson learned from legal history can serve as an example for the present-day representatives of the field, as the sector is exposed to many dangers in the 21[st] century from environmental damage to low-quality products delivered from countries outside the European Union sometimes even without an indication of origin. The European Union took immediate action against the import of counterfeit Chinese and cheap Ukrainian honey. In accordance with the interests of honey producers, from now it will be mandatory to indicate the place of origin and

- 147/148 -

the exact percentage of the honey on bottles of honey sold in the European Union. Legal cultural history helps legal practitioners of today to see that a sustainable development must also include sustainable legislation that takes into account the current political and economic conditions. ■

NOTES

[1] European Parliament: Key facts about Europe's honey market (infographie), 2024 https://www.europarl.europa.eu/topics/en/article/20180222STO98435/key-facts-about-europe-s-honey-market-infographic (2024. 11. 18.)

[2] Rossi, Rachele: "The EU's beekeeping sector. EPRS" European Parliamentary Research Service, 2017 https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/ATAG/2017/608786/EPRS_ATA%282017%29608786_EN.pdf (2024. 11. 18.)

[3] European Parliament, Legislative Observatory: 2017/2115(INI) - 01/03/2018 https://oeil.secure.europarl.europa.eu/oeil/popups/summary.do?id=1525333&t=e&l=en (2024. 11. 18.)

[4] EUR-Lex: Document 32024L1438 https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2024/1438/oj (2024. 11. 18.)

[5] Overview of the Annual Performance Report for Apiculture sectoral support under CAP Strategic Plans in FY 2023 (01/01/2023-15/10/2023)

[6] Nayik, Gulzar Ahmad et al.: Honey: Its History and Religious Significance: A Review. Universal Journal of Pharmacy 2024. 3(01). 5-8.

[7] Bogaard, Cecilia: The Araña Caves of Valencia: Entering a Bygone Era Through Rock Art. Ancient Origin, 6 July, 2021 https://www.ancient-origins.net/ancient-places-europe/ara-caves-0015539

[8] Gunda, Béla: A magyar gyűjtögető és zsákmányoló gazdálkodás kutatása. [Research on Hungarian gathering and exploiting farming] Néptudományi Intézet, Budapest 1948. 12.

[9] Kerecsényi, Edit H.: A népi méhészkedés története, formái és gyakorlata Nagykanizsa környékén [The history, forms and practice of folk beekeeping in the Nagykanizsa area]. Néprajzi Közlemények, 1969 13(3-4). 7.

[10] László Gyula: Árpád népe [Árpád's People]. Helikon, Budapest 1988. 102 - 124.

[11] Gunda Béla: Méhészkedés a magyarságnál [Beekeeping among the Hungarian]. Agria - Annales Musei Agriensis, 1991-1992 (27-28): 303-368. 334.

[12] Kristó Gyula: Pozsonyi Évkönyv [Pozsony Chronicle]. In: (Kristó Gyula ed.): Az államalapítás korának írott forrásai [Written Sources of the Era of the Founding of the State]. Szegedi Középkorász Műhely, Szeged 1999. 354 - 356.

[13] Győrffy György (ed.): Diplomata Hungariae Antiquissima. Akadémiai Kiadó, Budapest 1992 (=DHA) 1:90.

[14] DHA 1: 63.

[15] Erdélyi András: Méhészet a szerzetesek életében [Beekeeping in the Life of Monks]. Ciszterci Műemlékkönyvtár, Zirc 221. 10 - 14.o.

[16] Gombos Ferenc Albin: Catalogus fontium historiae Hungaricae aevo ducum et regum ex stirpe Arpad descendentium ab anno Christi DCCC usque ad annum MCCCI ab Academia litterarum de Sancto Stephano Rege nominata editus: O - Z. Tomus I. Academia Litterarum de Sancto Stephano Rege Nominata, Budapest 1938.

[17] DHA. 1: 204-218.

[18] Erdélyi, 12.

[19] Neugeboren Emil: A szászok történelmi fejlődése [The Historical Development of the Saxons]. In: (Sas Pál ed.): Ódon Erdély. Művelődéstörténeti tanulmányok [Ancient Transylvania. Cultural History Studies]. Magvető, Budapest, 1913.

[20] Paládi-Kovács Attila: Magyar Néprajz [Hungarian Ethnography]. Akadémiai Kiadó, Budapest 2001, 64 - 65.

[21] H. Kerecsényi, n. 7, 11.

[22] Györffy István: Nagykunsági krónika [Nagykunság Chronicle]. Turul, Budapest 1941. 44.

[23] Szabadfalvi József: A magyar méhészkedés múltja [The Past of Hungarian Beekeeping]. Piremon, Debrecen 1992, 107 - 128.

[24] Kodolányi János: Zsákmányolás-vadfogás, méhészet, gyűjtögetés [Looting - hunting, beekeeping, gathering]. In: (Ortutay Gyula ed.): Magyar Néprajzi Lexikon [Hungarian Ethnographic Lexicon]. Akadémiai Kiadó, Budapest 1997, 47 - 60.

[25] Paládi - Kovács, n. 16, 64 - 65.

[26] Szabadfalvy, n. 19, 107 - 128.

[27] Bél Mátyás: Magyarország népének élete 1730 táján [The Life of the People of Hungary around 1730]. Wellmann Imre Kiadója, Budapest 1984, 294.

[28] Gunda Béla: A felmentő méhrajról szóló erdélyi mondák [Transylvanian Legends about the Liberating Swarm of Bees]. Erdélyi Múzeum 1945. 50(3-4). 234-235.

[29] Takáts Sándor: Méz és viasz kivitelünk a XVI-XVIII. században [Our Honey and Wax Export from the 16[th] to the 18[th] Centuries]. Magyar Gazdaságtörténelmi Szemle 1900. VII. 477-478.

- 148/149 -

[30] Szabadfalvy, n. 19, 107 - 128.

[31] Paládi - Kovács, n. 16, 65.

[32] Gloger, Zygmunt: Encyklopedia Staropolska [Old Polish Encyclopaedia]. Piotr Laskauer i Spółka, Warsaw 1792. 269.

[33] Dąbkowski, Przemysław: Prawo prywatne polskie [Polish private law].Towarzystwo dla Popierania Nauki Pol., Lwów 1911. 223.

[34] Rafacz, Józef J.: Regale bartne na Mazowszu w późniejszym średniowieczu [Beekeeping regalia in Masovia in the later Middle Ages]. Tow. Nauk. z zasiłkiem Funduszu Kultury Nar. im. J. Piłsudskiego, Lwów 1938. 4.

[35] Ibid, 6.

[36] Ibid, 15.

[37] Ibid, 18.

[38] Ibid, 20.

[39] Ibid, 22.

[40] Ibid, 15.

[41] Kryński, Antoni: Porządek prawa bartnego dla starostwa łomżyńskiego z 1616 [The Order of the Beekeeping Law for the County of Lomza from 1616]. Imperial Jagellonian University, Krakow 1886.

[42] Niszczycki, Krzysztof: Prawo bartne bartnikom należące [The Apiary Rights of Beekeepers]. K. Wł. Wójcicki, Warsaw 1559.

[43] Skrodzki, Stanisław: Porządek prawa bartnego [The Order of Apiary Law]. A. Kryński, Warsaw 1886.

[44] Braun, Adam: Z dziejów bartnictwa w Polsce [The history of beekeeping in Poland]. Sklad Główny w Księgarni E. Wende i S-ka, Warsaw 1911. 12.

[45] Dąbkowski, n. 29, 108.

[46] Zamoyski, Andrzej: Zbiór praw sądowych [Collection of Judicial Rights]. Michał Gröll. Warsaw 1778.

[47] Malecki, Marian: Z dziejów Miechowa, jego prawa i wymiaru sprawiedliwości [History of Miechów; Its Law and "Administration of Justice]. Sąd Rejonowy w Miechowie, Miechów 2011. 55.

[48] Mikołajczyk, Marian: Przestępstwo i kara w prawie miast miejskich południowej Polski XVI - XVIII wieku [Crime and punishment in the law of southern Polish towns in the 16[th] - 18[th] centuries]. Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Śląskiego, Katowice 1998. 36.

Lábjegyzetek:

[1] The Author is professor, Department of General History of State and Law, Faculty of Law, Jagiellonian University.

[2] The Author is associate professor, Institute of Social Sciences, University of Dunaújváros honorary professor, Department of Legal History, Favulty of Law, University of Pécs.