Éva Kereszty[1]: Legislative Reform of the Hungarian Health Care (Annales, 2008., 215-258. o.)

1. Scope of the issue

The Hungarian health care system is in a permanent crossfire by the patient and the professionals, and also by the politicians. The criticism is in the front line of the first groups' voice, while the politicians run a reform rooted in the mid-eighties that has lead to weak results. There are huge zigzags in the goals and main elements of the reform because of the lack of negotiation on the future responsibility of the state in the Hungarian health care.

In the history of the Hungarian health care reform, economists had a leading position: most problems were communicated to the public, as the problem of the budget. The main message seemed to be to lessen the costs, but a really cost saving health service system hasn't been set up. Because of the budgetary led changes, the service infrastructure, the service content, the long-term investment into the health of the people remained in the background and in spite of legislative and budgetary reform steps a huge proportion of the system is working similarly to the mid-eighties.

The term "reform" has become increasingly popular during the last few years. In spite of the wide use of this concept, there is no consistent and universally accepted definition of what constitutes a health sector reform. In some cases, national policy-makers and politicians have sought to magnify small changes by labeling them "reforms". It is useful to distinguish structural reforms from incremental changes. The introduction of new technologies in diagnostics, the use of new pharmaceutical products, the regular supervision of the professional guidelines is not a reform. In my regard, the continuous modernization is essential (and incremental) in health sciences and in the practice, but this is not a reform. When some say, that "only" much more money, new equipment, higher level of comfort is needed, they deny the necessity of the reform, they just narrow the existing problems to a modernization agenda. In my opinion the reform is a change, which turns the immanent logic of aimed system elements. The new logic and the concerning practice may lead to a quicker modernization and a self-remedy of the system errors.

- 215/216 -

The pillars of a reform are the changing health policies and the institutions through which these are implemented. The institutions, the organizational structures and the management system should be changed; the redefinition of policy objectives alone is not enough. Thus, health care reform is concerned with "defining priorities, refining policies and reforming the institutions through which those policies are implemented"[1].

Beyond the traditional roles of the legislation, the "reform acts" may have two basic functions concerning the definition: making the painful changes inevitable, and clarifying the changed state position in the health care area.

In spite of the lack of a real reform, very important modernization steps have been introduced to improve the Hungarian health care system since the early '90s and some sub-areas of the health care system have been reformed. These reforms have often endeavored to bring best practice, for example through the introduction of social insurance principles, mixed public and private ownership, separation of payment and control, increased management autonomy and the rationalization of primary care services. Nevertheless, due mainly to implementation difficulties, achievements of these steps are inconsistent, and now we are at the starting-point of a new phase of the health care service accession: the reform of the compulsory social security health insurance system.

Most studies of the Hungarian health care reform present a management and financing reform. There are some studies on health policy and public health issues. In the recent years the patient-physician connection is also on the table. The structural, administrative and legal analysis is rare, the implementation efficiency is practically not examined, and the application is not supervised. In a long-term thinking it would be necessary to have a stabile, fair and applicable legal background for the better outcome of the health sector. For these purposes it can be useful to compare the aims, the legal instruments and the practical implementation. With regard to the complexity of the issue in the study I will focus on the legislative and other regulative measures of the health care modernization and reform, and don't pay attention to the practical health practice issues, public health challenges, the daily management problems, the professional education of personnel, or the detailed financing and paying problems and the potential European financial resources of development. I try giving a retrospective blueprint of the reform steps introduced seventeen-twenty years ago, and try to analyze the importance of the changes, the supporting measures and the obstacles, the positive elements and the unsuccessful points.

- 216/217 -

2. Starting point of the health care reform - 1989

2.1. Legislation

In Hungary, the Constitution[2] declares the right of everybody living in the territory of Hungary "to the highest possible level of physical and mental health.[3]" In addition and for the practical realization of it, citizens have a right to social security, which involves an entitlement to benefits guaranteeing income for old people, widows, orphans and unemployed who lost their jobs due to reasons other than their own fault, or in the event of ill health and disability[4]. The state satisfies this obligation through social security and social institutions[5]. The Constitution sets a task for the Government to define the public system of social and health care, and to secure funding for these services[6]. The right to health as a constitutional right was declared in 1989[7]. The former text declared the "right to the protection of citizens' life, physical integrity and health[8]" and the state was responsible for organizing the health institutions and the health care system. It's only a general misunderstanding that the right to highest possible level of health is a residue of the socialist health care system, on the contrary: it is the result of the changed attitude on constitutional rights, and one of the transformed norms when preparing the transformation of the whole political regime.

The health sector regulation stood mostly on a decree base; the majority of the professional rules were issued in direct orders and by-laws. There were almost 300 acts and decrees and hundreds of orders. It is a controversial phenomenon, that the physicians knew these professional by-laws and orders better, than the legislative instruments now. The professional, ministerial documents were accepted and followed voluntarily, while today the legal instruments don't even reach physically the physicians or the hospital wards, they stop in the offices of the management. So the better and more democratic legislation now is, it is not so effective for the health professionals, than it was in the former regime.

The Health Act[9] was the basic document of the health care system, declaring the free service to the Hungarian citizens.[10] The basic success of the act was in 1972, when this legislation introduced the total coverage of citizens by health

- 217/218 -

care.[11] The scope of the Social Insurance Act[12] is the subsidy system (maternal subsidies, sick-allowances, pensions) and the regulation of the contributions. The health services were not under the scope of the social insurance, they got into it in the middle of the first governmental cycle of transition in 1992, when health services became (theoretically) insurance-based services.[13]

The most impressive and effective change of 1989 is the gate opening for private health enterprises. The health sector - officially - was totally state possessed and state run. Two elements were overflowing the totality of the state: the part-time minimal private outpatient services of specialists[14] and the illegal private praxis in the state hospital financed by the gratitude.[15] The essence of the new regulation was, that the health enterprises could start to work without state ownership or public service employees. This legislation wanted to inspire the individual physicians to work in the out-patient sector as micro (individual) enterprise, but the legislation had a much broader sense: on the basis of it any types of investments could be put into the health sector, any kind of privatization was possible, private hospitals and diagnostic centers could be founded -as it really happened in the following years. This legislation and the private initiatives introduced several unknown or unused ideas in the health providers' terminology, like fee for service, price of the device, competition of providers, patient satisfaction. In my opinion this order was a really important reform step in full harmony with the planned political and economical changes of the regime. This order was frequently applied, while the prior mentioned constitutional changes were not echoed by the people or by the professionals.

- 218/219 -

2.2. Actual situation before the socio-economic changes

Examining the reform process it is useful to have an overview of the main characteristics of the Hungarian health care system in the late '80s. This could be the base line for the later comparison to the changed elements. The list also reflects on the main problems of the system clarified by the reform committee of the health ministry in 1988-1989.

a) Health care and health insurance care is not divided; health care is an integrated part of the socialist state sectors. Each citizen is covered by full service of health care; everyone gets (theoretically) everything. Equity and equality of access is the part of the political communication, but the "VIP" elite enjoys extra privileges without plus contribution[16].

c) State owned and directed, hospital focused system, health is social good for the citizens.

d) Weakness of prevention and healthy lifestyle actions; "in-patient orientation" of the actors, health sector is dominated by curing doctors; health is the responsibility of the health care system.

e) Health care is cheap (officially free), medicine and devices are cheap for patients, but the choice of these products is poor. Newest and hightech technology is not affordable for the state.

f) Money under the table for compensating the law income of the doctors and buying individual, private services in the state institutions.[17]

g) In-patient over-capacity, outpatient capacity is not satisfactory (inequalities, queuing, quality assurance problems), low prestige of the GPs.[18] Health sector has a strong social function, in-patient health care

- 219/220 -

facilities substitute the shortage of long-term care and institutional care for aged and poor.

h) Shortage of health professionals in some areas (the non-gratitude specialties), plenty of them at others, part-time private practice of the clinicians.

i) Lack of home-care capacity, the basic nursing, help and it is not solved to care the aged, sick, single in their homes. This shortage in social care functions is not really substituted by the hospitals, because the chronic and long-term care is not preferred by the professionals, so "social indication" patients are laying on the active (internal medicine) capacity.[19]

j) Control mechanisms (professional performance and insurance) are weak; the direct state command system doesn't need neither an independent control authority nor a state guided "self-control" mechanism.[20]

2.3. Perspective of the reforms

"Equity" or "equality of access" would be the overwhelming response if European legislators and businessmen were to be asked for their characterization of the important values of the health care system. This is an approach, which can readily be identified in government policy statements across Europe. The important issue, however, is that there is a principle that the poor, disadvantaged and chronically sick should not be financially ruined or socially excluded from health care because of their life circumstances, and that this is accepted by society. As always, there are differences between principle and practice as evidenced by the increasing recognition of European governments that they have to tackle the issues of widening inequalities in health care. In the socialist countries "equality of access" was declared, but the clear inequalities were not confessed. At the same time the "equality in poverty" was the basic characteristic of the public health care system, and the politically VIPs and the blackmarket consuming rich ones stepped out from the solidarity based uniform pubic health services. The real equity and equality is not only constitutional right in the health accession, but also a practical problem of the structure of the institutions, the quality of the care offered in the institutions and at the cost-

- 220/221 -

sharing mechanisms among the consumers of health care. The hypothesis, that health care is a social good, and is accessible without time, cost or other limitations cannot be maintained any more. Some people say, that the solidarity is weakened after the socio-economic changes, and rich ones don't show solidarity any more with those who are in need. On the other side a big number of free-riders live on the solidarity of the insurance premium payers. A huge challenge for the decision-makers is to find a good and acceptable balance between solidarity and the fulfilling of extra personal needs.

At the opposite extreme of the social good concept, there is the view that health care is essentially a private consumption good for which the individual is responsible, because many if not most modern diseases are rooted somehow in the individual's behavior. The doctrine of personal responsibility for one's own health has always been present, but it has taken a higher profile in recent years as the pressure on health care resources has increased; and the attention has been focused much more on prevention being a more effective and less costly approach, than cure is. This is now stated clearly and specifically in government publications on health strategy and public health across Europe. Poverty and unhealthy lifestyle is in a close connection. Other than information and education, help and motivation to change could lead to the deepening of the gap between the lower social classes and the rich. The sanctioning legislation is not realistic in the countries in transition.

3. Socioeconomic changes and reforms of the health care 1989-2007

Countries have developed a wide variety of strategies for policy intervention at different levels of the health care system. Across Europe four integrating themes can be observed as instruments of the reform objectives[21]. The four are as it follows:

• The changing roles of the state and the market in the health care;

• Decentralization to the lower levels of the public sector or to the private sector;

• Greater choice and empowerment of patients;

• The evolving role of public health.

- 221/222 -

The Hungarian reform could also be analyzed from these aspects, but taking into consideration the hot points of political discussions, I follow a bit different, structural, five-element analysis and don't pay too much attention to the pressure of health trends, ageing, mortality and morbidity challenge in Hungary. None the less it is one of the strongest constraints of the long-term reform vision.

3.1. The five branches of reform:

It is hard to make a systematization of the reform steps, because so many elements are mixed in it, and so many external effects, interests and circumstances influenced the health care reform agenda. The next keystones reflect the political, socio-economical changes, the pressure of the international health policy trends, the main problems and tension in our system and the repeatedly raised questions and advise of the national and international experts[22].

3.1.1. Social security

The free health care, total access and state guaranteed high quality were the three principles of the socialist health care. However, it was clear, that the three together are impossible to be maintained, this false belief still exists among the people. Some try to explain the text of the present Constitution (right to possible highest level of health) in the way that it means the free access to the totality of highest level services. As we mentioned before, the separation of the Insurance Funds was one of the first steps of the economic changes, and the social security health system was put on a compulsory insurance pillar, with special contribution (1992). The insurance package (the health plan of the citizens in the framework of the compulsory insurance) was defined, and the direct state financing was reduced to the public health issues. From 1992 the health services are not free of charge, but the great majority of the services are covered by a 100 percent third party payment - the Health Insurance Fund.[23] However, the legislation opens a broad door for the introduction of co-payment, the raising personal expenditure is seen only on the pharmacy bills. As a result the people (and sometimes also the decision makers) don't make a difference between the health care sector as a whole and the health insurance sector. The health insurance sector covers 90-95% of the health sector, and the most costly services are not available in the private health arena.

- 222/223 -

From the mid '90s the main slogan of the social security reform is "growing into real insurance system". The revision of the insurance plan, the detailed regulation of the insurance covered services, the role of the co-payment and patient-insurance administration connection has been debated for more than a decade now. The Bokros' consolidation package led to the revision of the plans, and the insurance coverage was narrowed. The occupational health services are not paid by the Insurance Fund, the recuperation service coverage was narrowed drastically - and this regulation still exists. The co-payment for the dental care has been partially withdrawn[24], and the regulation of the symbolic co-payment to the ambulance-transportation was repealed because too much administration, too strong resistance and too small income was the one-year experience.[25]

The next revision of the plans was due to the new health act and the new social security health insurance act in 1997. At this time a systematization, a clearer separation of the state financed, insurance financed, and third party financed and consumer paid services has been done, but nothing changed. Some clarification of the luxury service (or comfort service) co-payment was also added to the legislation, but the next milestone of the revision was the year 2007. The appointment fee and the daily in-patient contribution[26] is a compulsory, general co-payment, which reminds the insured patient, that health care is not free.

The possibility of voluntary supplementary health insurance is also open to people. For-profit forms and voluntary "mutual health insurance" enterprises exist. These are not too popular for two reasons: on the one hand people's health awareness and the recognition of the importance of the supplementary health savings is weak. On the other side uncontrolled full coverage of the big majority of possible care doesn't leave services to be offered beyond the compulsory system.[27]

- 223/224 -

The other change is the narrowed service package[28]: some services were put into the direct governmental responsibility (e.g. the death detection and pathology issues). Some services were excluded from the common risk management of the social security; it is not covered by the solidarity of the clients of the national, compulsory health insurance (risk) community. The exclusion could be much fairer, if the alternative payment channels and the people were prepared to this change. The extreme sports represent a kind of personal responsibility for the dangerous activities. The injuries and hurts originated in connection with the extreme sport activity is not in the coverage any more, so the targeted sportsmen must save the medical costs or conclude a private insurance contract.

The supervision of the service package set up an entitlement to the basic care services, like the life saving and emergency services, the care of the pregnant women, newborn babies. When providing the services in these cases, the provider doesn't check the validity of the insurance card before the needed immediate interventions. In the other cases - before the medical intervention - the existence of the insurance coverage is controlled and if it is not valid the patient cannot be treated on a social security basis. Without a valid insurance card the patient has to pay the (market) price of the service. Theoretically the legislation hasn't introduced a new entitlement or process. The legislation is rather a clarification of the not questioned basic treatment situations. But on the other hand this is a revolutionary reform step forward for serving as an effective instrument to catch the free-riders of the social security system. The income related compulsory contribution has been in force for decades, but after the socio-economic changes it hasn't operated well. The growing number of the self-employed, the weak control mechanisms have let an open space for the contribution (and tax) evasion. It is not the legislation, "only" the executive measures to make the law operate, this is the core element in rebalancing the Health Insurance Fund and strengthening its insurance character.

The next step, the involvement of the private health insurance companies into the social security health insurance is still not finally decided, but needs a brand new legislation of the insurance system.

- 224/225 -

3.1.2. Ownership, decentralization, local government

3.1.2.1. Ownership - privatization

Hospitals are primary owned by local governments[29], and secondly by the state, on behalf of which the Ministry of Health exercises the ownership rights over university clinical departments and national institutes. In Hungary a large number of hospitals are run by churches, foundations and private owners, although the bed volume in such hospitals is low.

As part of the overall political transformation, the system of public administration was greatly decentralized during the 1990s and the coordinating function of the county governments was eliminated. Local governments were given responsibility for the development of their own healthcare infrastructure and hospitals (among other state-owned assets) were transferred to them (municipal and county). As a result, significant duplication and excess capacities have become more prevalent, while available financial resources to operate existing physical capacities have declined.

Financially, hospitals were exposed to an imbalance between the large catchment areas (panels) they were meant to serve and the often very small communities to which they belonged. Local governments without specialty health care services didn't pay any contribution to the running and development costs of the panel hospital, however, the possessors of the panel hospital didn't have any targeted resources (e.g. from the central budget) for this purpose. A number of hospitals were unable to meet the demands without generating large deficits. Part of the responsibility for these deficits lies with the local governments, who as owners, failed to exercise effective control over their hospitals and were unable to finance the deficits themselves, but simultaneously refused to give up ownership and control.[30] As a result, the central government has been placed in the position of bailing out the hospitals or letting them go bankrupt. Understandably, the former option was taken, but this has generated a serious moral hazard problem.[31]

Legal provisions allowing private services (also corporate forms) to operate have been in place since 1990 and, most notably, private provision is now used in a significant share of outpatient care. Contracts set up by the National Health

- 225/226 -

Insurance Fund Administration (NHIFA) involve a number of private service providers: family doctors; suppliers of outpatient equipment and office spaces; pharmacies; and specialized medical providers, notably providers of magnetic resonance imaging and kidney dialysis. The presence of these private providers has contributed to increases in the amount of non-subsidized private spending on health. Figures for 2002 suggest about half the total outpatient spending was either in this form of health spending or in co-payments for subsidized drugs or "gratitude money".[32]

Privatization is the ultimate form of decentralization, in that is intended to replace direct public authority over decision making with corporate firms. The market incentives for greater efficiency and higher quality of the management of the care providers can be the benefit of privatization. However, the disadvantages of privatization are also considerable. The required financial return (which is consistent with the market economy) pressures the owners to abandon the social character of health services to intentionally discriminating against sick and vulnerable groups, who require care. In the first stage of the Hungarian reform this questions were simplified: there was no need for investment or capital to become a health care micro-enterprise, because the governmental motivation of privatization aimed the so-called "functional" privatization[33]. The GP system started the privatization with this type of operation contract, they didn't need return of investment, because they didn't have investments into the praxis, but they could easily raise their personal income, through the self-employment income and tax regulations.[34] The Hungarian Medical Chamber issued several declarations in which they emphasized that the micro-enterprises of the physicians or the self-employed physician (with the office and the devices and total decision-making entitlement in this praxis and employer role in relation with the assistance) is "not a privatization", because the personal profit is so small. Their opposition is focused against the privatization of the outpatient centers[35] and hospitals, based on the profitability of the institutions where the physicians would be employees.

- 226/227 -

After the 1989 gate-opener governmental decree no further steps were taken to regulate the privatization of the service providers.[36] General rules operated in the sector sometimes with a lot of problems because of the differing interpretations. The two forms of privatization in the Hungarian health care are the following: private health providers conclude a contract with the NHIFA to provide public services, and optionally conclude a contract with the local government for providing the services, which are in the responsibility of the local government. The other form is the real privatization, when a former public owned and run institution changes to an enterprise. The big majority of the buildings, devices, real estates remained in the ownership of the local governments, the transformation was limited to the operation and the management. The health care property belongs to the limited negotiable possess category, which in a different interpretation is understood as not negotiable, or "only for health care use." This misunderstanding is also an obstacle of the privatization and needs some future clarification.[37]

The privatization in the '90s was not only an option for the physicians and the investors, but also a need for the institutions. From the mid '90s the growing deficit of the health care providers alarmed the governments to input more financial resources to sustain the system. The state budget was not able to ensure the resources, so the government tended to get the cover from the private sector, from investors. From the point of ownership and of the contracts of providing public services the "first capacity act[38]" was not discriminative for private providers, the Health Act (1997) and the Health Insurance Act (1997) is expressively neutral in this sense. Thus the spontaneous privatization became widespread: handbooks, manager information were published, postgraduate trainings started for the privatizing doctors. In 2000 the "theoretical value of the praxis" was given (free of charge) to the GPs in the form of "entitlement of panel operation".[39] After a three-year preparation in 2001 the first "act on institutions" entered into force[40], regulating the privatization, the role of the private providers in the health sector and regulating the forms of self-employment. Some points were in a strong crossfire in this act, so - keeping the majority of the former regulation - in the next governmental cycle a new act[41] was voted

- 227/228 -

for the purpose of introducing new types of operational forms, already existing in other fields of the economy (corporate forms) in order to modernize the health care system. The Institutional Act introduced the concept of public health services (health service partly or fully financed by the budget), established rules for the organization of public health services, determined the conditions under which health service providers can provide public health services, and also defined responsibility for the organization for public health services. The act also provides that local governments may satisfy their obligation to provide health services not only by operating their own health institution, but also through contracts (health service contract), and defined the rules of such contracts, too. The Constitutional Court declared this act anti-constitutional for formal reasons, and annulled it, but did not examine the contents of the act at all. The Ministry intended to cover the key elements of the regulations contained in the Institutional Act in other legal regulations on a lower legislative level.[42]

The State Audit Office (SAO) examined the privatization process in the health sector in 2005; the report underlined the lack of legislation and the unreasonable political talk on this issue[43]. In the recent months some politicians questioned the privatization. Whatever legislation is to be prepared, the decision makers must face the fact, that the Hungarian public health service system is based on a mixed ownership and in several fields the private sector ensures the majority of the care. The proportion of the public services provided by private/corporate health care institutions in 2005 is presented in the next table [Table 1][44]:

- 228/229 -

Table 1

The rate of public services provided by private/corporate institutions (2005) by payment contracts of the NHIFA[45]

| Service type | Proportion of private/corporate provider (%) |

| GP service | 85 |

| Dentistry | 91 |

| Patient transport | 47 |

| CT/MRI diagnostics | 28,3 |

| Professional nursing home care | 93 |

| Out-patient specialty services at all | 14,3 |

| In-patient specialty services at all | 4,6 |

3.1.2.2. Decentralization

Decentralization is a central tenet of the health sector reform in many European countries. It is seen as an effective measure to stimulate improvements in service delivery, to ensure better allocation of resources (according to the needs), to involve the community in priority setting, and to facilitate the reduction of inequalities in health. Decentralization is attractive because it is difficult for the central administration to be close enough to the users and address appropriate and sensitive responses to the local preferences. In almost every country, the same drawbacks of the centralized systems had been identified: poor efficiency, slowness of change and innovation, lack of responsiveness to local changes in health and health care needs. The suspect of political manipulation in the centralized systems is also experienced as a cause of concern.

On the other side the autonomy of the local governments may result in the neglecting of the mainstream plans and steps of centrally initiated reforms and may lead to a kind of political resistance opposing the new initiatives. In the Hungarian experience these negative effects have also been detected. The economy incentives (performance related payment system), the limitation of working hours, the introduction of some quality standards could not press the local governments to voluntarily change the structure and profile of the care system and to cooperate with each other on a long-term contractual basis. They preferred lobbying for central budget subsidies and the postponing of the effect of the legal standards.[46]

- 229/230 -

Achieving equality of public services throughout the country is one of the most important objectives in expanding central governments' powers. The regulations, specific and general grants (and the close future European Union resources of development projects) are used to reallocate the resources geographically, which conflicts the local interests.[47] In the Hungarian system the local governments are legally equal, but county governments have more responsibilities for organizing the full spectrum of specialty health services, than the municipal level. The latter is responsible only for the primary care to be ensured, but the maintenance of anything more is voluntarily undertaken. The share of the responsibility, the ultimate decision making in debated questions in not clear, the local prestige fights and political bargaining overwrite the health sector rationality. Central governments have increasingly tended to place restrictions on local governments. These restrictions couldn't be effective enough without the modification of the Act on Local Governments[48], which is almost impossible concerning the lack of the consensus of parliamentary political parties and the need of 2/3 majority votes.

Analyzing the trends after the political changes we see a swing in the decentralization and re-centralization of the decision-making. Similar trends are seen in the governmental sector and civil sector relation. The involvement and participation of the NGOs, professional associations, chambers, the controlling and bodies in the health sector governing is permanently changed, their competency is disputed, their position in the system is not fixed. Most of them are dependent from the state budget subsidies. Their role and competence is more or less only a declaration in the Acts, but don't have an enforcement instrument. The central government's responsibility and full authority in the decision-making is not limited by the civil participation or the democratic consultation before. The Constitutional Court also declared this principle in a health legislation case.[49]

The third element of the decentralization is the intra-governmental authority sharing, which has also been swinging. The autonomy of the Health Insurance Fund never has become reality in the financial sense and the shared authorities between the government and the self-governing body of the Funds were also

- 230/231 -

temporary. From 1999 a strong, direct subordination of the NHIFA has been effected. There is a political competition on the ministerial level for the supervisory authorities between the ministry of health and the ministry of finance. The doubled supervision system led to weak control over the NHIFA, which has not changed in the last months by the establishment[50] of a governmental office, the Health Insurance Supervisory Body.[51]

In the state administration one of the leading principles is not to keep authorities for the minister in individual administrative cases. In the health sector the general authority is the National Public Health and Chief Medical Officer's Office, but several authorities manage the drug registration, the registration of the professionals, the ethical supervision of clinical trials, etc. After a step by step decentralization a re-centralization is recently experienced, when some decisions are redirected to the minister, recalling the memories of direct state intervention and command system instead of legislative governance. Parallel to these, the de-concentration of the system is reshaped, the regional level takes over the county administrations. In the NHIFA the authority of the de-concentrated county agencies was disputed, some general managers tended to concentrate a strong personal authority, others let the most appropriate local administration to exercise the decision-making on their own.

The Regional Health Councils[52] could be the example of a decentralized and de-concentrated mixed decision-making platform[53], but the above mentioned rigidity of the Act on Local Governments restricts the potential authority of these bodies.[54] In 2006 the Councils denied the dispute and decision preparation of the reductive capacity sharing plan of the health minister, and gave the total responsibility back to the minister, who centralized the final authority of issuing the resolution. In this case the decentralization conveyed an impression that the minister only wanted to push the political responsibility out from his competency, but never prepared for a really decentralized decision-making. The absolute little range of choice offered to the regional bodies was the result of the Act, which fixed the number of hospital beds by the list of hospitals on the highest parliamentary level, undertaking the role and responsibility of the

- 231/232 -

Government in administrative and executive spheres. Summarizing the phenomenon we can say, that there was decentralization (devolution) only on the superficial institutional level, while the decision-making authority was centralized and taken to the highest possible level.

The types and forms of decentralization are colourful. If we want to systematize it (focusing on the health sector) it is useful to use the categories of deconcentration, devolution or political decentralization, delegation and privatization. During the heath care reform each of them appeared, and changed a lot. Examining the health insurance system we can't see so big changes. The most sensitive issue of the reform is whether a kind of devolution, delegation and privatization (by detailed legislation and strengthened state control) of the social health insurance is acceptable, or there is no social security without a total and direct ownership and supervision of the insurance system.

Each type of decentralization may be learnt in the European Union member states as well. There are plenty of experiences of benefits and risks of decentralization[55]. Devolution results in a lack of political control, or in local government political control opposing the governmental plans. Delegation has the risk that on the lower level the professionalism is much less, as it is seen in the local governments administrative staff, where they can't afford even to have contracted experts. The risk of privatization is the emergence of monopolies that may exploit their power (market failure), as this accusation was targeted to the hemodialysis service provider owners or to the privatized laboratories - and sometimes this really could happen.

The next table [Table 2] shows the decentralization map of the health care system in four time ranges from the political changes until now.

- 232/233 -

Table 2

Decentralization and re-centralization in the Hungarian health care system

1989-2007

| End of 1980s | Early and mid 1990s | Around the millennium | From 2002 | |

| Devolution (political decision-making decentralization) | State budget covers the health expenditure | 1991: National Insurance Fund - and 1993: its self-governing body | 1998: Governing Body's termination 1998- 1999: Supervisory authority is the Prime Min- ister's Office 1999-2001: Supervisory au- thority is the MOF's Politi- cal State Secretary 2001-2005: Supervisory au- thority is the MOH | 2005: Small Supervisory Board (appointed by the Government) 2007: National Health Insurance Supervisory Au- thority for centralized con- trol functions, termination of the supervisory board |

| Direct state (government) responsibility for the cen- tralized care system | 1990: Local government is responsible for maintenance of care for the inhabitants | NO CHANGE | NO CHANGE | |

| Governmental decisions on development policy | 1996: County Negotiation Forums for capacity self- regulation | 2001: professional colleges give opinion for the ministe- rial (MOH and MOF) deci- sion on new capacities Service providers apply once a year for the right of contracting | 2006: Detailed act on the capacities (with centralized decision of the Parliament) and for the minor propor- tion of the further capacities Regional Health Councils share the competence with the Minister of Health Administrative resolution: Minister of Health |

- 233/234 -

| 1998: National Health Council (governmental ad- visory body with very weak competence) | NO CHANGE | NO CHANGE | ||

| Professional advisory coun- cils help the preparations of the reform steps | NO CHANGE | NO CHANGE | NO CHANGE 2007: stakeholders advisory councils help the prepara- tions of the reform steps | |

| Trade Unions have legally guaranteed rights in deci- sion-making process | Political round tables work on political consensus | 1999: Medical Chamber gets general, guaranteed rights (consultative rights) in decision-making and leg- islation | 2007: Membership in the Chamber is not compulsory - consultative rights are ob- tuse or withdrawn | |

| Deconcentration (administrative decentralization) | County and Municipal Council's Executive Com- mittees are responsible for the local execution of central initiatives and orders; Municipal authorities are in the hierarchic subordination of the county level | 1991: Chief Medical Offi- cer's Office for administra- tive procedures and profes- sional control 1996: Chief Medical Offi- cer's Office (and its county and town offices) have the licensing authority of any health care provider | NO CHANGE | NO CHANGE 2007: Parallel professional control authorization of the National Health Insurance Supervisory Authority NO CHANGE |

| 1994: Medical Chamber op- erates the national registry of physicians, has the right for veto in the settlement of foreign physicians | 2000: Medical Chamber gets the licensing authority of GP's praxis operating competency | 2007: Chambers are termi- nated, administrative tasks and authorities go back to the Office of Health Au- thorization and Administra- tive Procedures, which be- long to the MOH |

- 234/235 -

| 1996: NIHF Administration - administrative resolution on capacity sharing | 2001: decision making is located directly to the MOH and MOF | 2006: MOH and Regional Health Council's shared au- thority | ||

| 1994: Professional Colleges set up professional stan- dards | 1999: Operation and super- vision of the professional colleges is the task of the Medical Chamber, the fi- nancial resources of this are in the state budget | 2004: Strengthened role of self-governance of colleges, as ministerial advisory bod- ies, financial resources are in the state (ministerial) budget | ||

| Delegation (task allocation to lower organizational level) | 1994: Pharmacists' Cham- ber's consultative and veto rights in licensing of the newly opened pharmacies; authority is at the MOH | 1999: Pharmacists' Cham- ber's consultative and veto rights in licensing of the newly opened pharmacies; authority is at the Chief Medical Officer's Office | 2007: Chambers are termi- nated, authority is directed to the Chief Medical Offi- cer's Office | |

| Ethical magistrates operated by the Trade Union of Health Sector Workers | 1994: Ethical magistrates operated by the Medical Chamber Ethical Code: voted by the General Assembly of the Medical Chamber (legality control of ethical procedures is at the court) | NO CHANGE | 2007: Centralized ethical body governed by the Chief Medical Officer's Office for the non-members of the Chamber, other belong un- der the ethical authority of the Chamber Ethical Code: ministerial order of the MOH | |

| 1995: Occupational health is the responsibility of the em- ployers (it is outside from the compulsory health in- surance services) | NO CHANGE | NO CHANGE |

- 235/236 -

| Privatization (task transfer from the public to the private sector) | Part-time private job | 1992-: private out-patient services contract with the NHIF (also investments: CT, MRI, hem dialysis, laboratory) or with other care providers | 2002. Act on the privatiza- tion of health care institu- tions | 2003: modified act on the privatization of health care institutions and the regula- tion of investment, and the financial-economic operation of the health care institutions 2003: Annulation of the act by Constitutional Court Neither regulation, nor pro- hibition: general rules for the privatization |

| 1989: authorization of pri- vate praxis | 1994: Privatization of phar- macies | NO CHANGE | NO CHANGE | |

| 1995: privatization of oc- cupational health | NO CHANGE | NO CHANGE | ||

| 1992: GPs' privatization | 2000: "Praxis operating li- cense" as a property is intro- duced; Right to privatize the real estate and other material property of the GP's office | NO CHANGE |

NHIF = National Health Insurance Fund

GP = general practitioner (some mention it as "family practitioner")

MOH = Minister of Health

MOF = Minister of Finance

- 236/237 -

3.1.3. Structure of the health care system

The most important structural problem of the Hungarian health care system is its hospital centered structure and the hospital centered legislation: very often and without any specific reason, care often takes place at the highest and most costly level of the system, as if bypassing the primary health and/or specialty outpatient care. The most frequently, but not exclusively, mentioned problem is the concentration of hospital capacities in Budapest: nearly 30% of all hospital beds are situated in Budapest, with its 2-million population, which is one-fifth of the total population of the country. The absorbing capacity of Budapest and the fact that national tertiary-care inpatient institutions (top of progressive care) are situated in Budapest explain the high volume of hospital beds exceeding the proportion of population, but the figures are definitely excessive. The centralized road railway map of the country also makes the capital a collection point for services.

In a European comparison, Hungary has relatively few but large hospitals, with an average number of 458 beds per hospital. In the 1960s and 1970s the level of development of the health system was measured with the number of hospital beds, in addition to the doctor/population ratio, both in the western and eastern parts of the world. However, in the 1980s it was recognized in the west that the number of beds is higher than the required number, and the surplus capacity only increased expenditure Therefore they began to reduce the number of hospital beds. Hungary started to follow this trend only in 1995. Although one-fifth of the hospital beds have disappeared, the number of hospital beds is still higher than in several EU Member States, and the structure of the specialties is behind the times.

The first capacity reduction through the discretional authority of the ministry and the NHIFA was unconstitutional.[56] The complicated bargaining system of the local governments on county level resulted in the wished reduction in bed number, but also resulted in unprincipled, unprofessional compromises and background contractions for their peaceful co-existence[57]. The 2001 legislation[58] was simply fixing the prior capacities and regulating the contracting conditions for new applicants. The execution of the Act was double-sided: the preparatory phase became more professional, a kind of provider's competition started, but minister of health and the minister of finance never kept the legal terms and in some cases broke the professional criteria.[59] In 2006 the reduction

- 237/238 -

covered the number and the structure.[60] The professional preparations of the decision are not known, the transparency of the legislation is weak. The absolutely centralized decision involving the Insurance Fund budgetary balance in 2007 seems to be effective, but the structural decisions and the payment limits together with the unlimited obligations of the health care providers and the owners raise questions on the constitutional character of the legislation.[61] The legislation led to a rigid, frozen system, in which the number of hospital beds of named wards in named hospitals are fixed in the act, so there is no place for professional change, supervision is only possible by way of the modification of the act. In my opinion this "shocking reduction legislation" can only be a short-term instrument to start a speedier phase of structural reforms following the prior, "small steps policy" reforms.

3.1.4. Professional organizations and civil initiatives, patient's participation

Decentralization policy has a great impact on the role of the NGOs' in health policy. The traditional patriarchic relation of the physicians and their patients needs a longer time to be transformed into partnership, a personal treating relation, in the local and central health policy relations as well. Legal provisions and the "introduction of patient's rights" from one day to the other are not enough, the daily practice, the court cases together may lead to a changed relation of the actors. Following the political changes the newly established NGOs were warmly welcomed on a general level, but not accepted in the local, bilateral level. Health care and the operation of its institutions are not transparent, the decisions are subjective, and doctors consider themselves unquestionable. For this attitude the NGOs were kept far from the providers' inner life. The NGOs as lay people's organizations were also criticized when asking more information and explanation on health care or health policy issues. Professional organizations existed prior to the political changes as well, but most of them represented the scientific community and served as a scientific platform. Health policy issues or advocates role for the members haven't been on the agenda. The boom of the civil organization establishment appeared in the health sector as well. The types of these organizations are as follows:

1. Professional organizations of medical professionals

a. Bodies endowed with public authority (chambers)

b. Associations of medical management interest groups (hospital managers)

c. Medical associations of sciences

- 238/239 -

2. Patients' organizations focusing on a special health problem ("diagnosis organizations")

3. Organizations for healthy lifestyle, health promoting groups and organizations

4. Interest groups, patients' rights organizations, patients' advocate organizations

The short history of the NGOs makes it difficult to involve them into the health policy consultations, because it is hard to select the really "voicing" NGOs. There are too many, separate organizations, too few members of them and the nationwide umbrella organizations are extremely rare. Most of the NGOs are not self-financed, they are absolutely dependent on the state budget, and are in competition with each other for the resources. Consequently the selection for partnership is based on the lobby capacity and the mutual political confidence.[62] The legal opportunity for partnerships in the health policy decision-making is relatively rich. The Act on Legislation[63] started to give place for participation and the Act on the Freedom of Electronic Information[64] ensured also technically the transparency of the legislation. However, the one-side opinion forming is not a partnership in the preparation and execution of the regulations. In the health sector the Health Act introduced the representation of the NGOs in the National Health Council and the participation of the local patients' organizations in the Hospital Supervising Councils, but their role is extremely weak. This is one cause of the low-level understanding and acceptance of the reforms.

Among the professional organizations the chambers played a specific role in the reform. When established the chamber was a voluntary association to have a not clinical specialty based organization of physicians (while the trade union lost its attractiveness). In 1994 compulsory membership was introduced and the chamber was one of the clearest examples of decentralization and delegation of public authorities.[65] That time the compulsory membership was argued even before the Constitutional Court.[66] After 10-12 years the chambers acquired a strong political profile in their advocate and health policy-influencing role but - in the background - they set up a correct registry and post-graduate training registry system. The annulment of the mandatory membership of chambers

- 239/240 -

(only in the health sector) cannot be regarded as a reform step; it is contrary to the democratization and self-governance principles of the social reforms.

3.1.5. New public health

On the basis of the unfavorable public health processes of the last few decades, the government assigns priority importance to the improvement of the public health situation and recognizes the population's expectation to gradually close the gap between life expectancy at birth of Hungarians and the average of the EU Member States. Any tangible improvement in the health status of people and in the healthcare delivery system may only be achieved over a longer period, covering several electoral cycles. Maintaining and promoting health cannot be regarded as expenditure only, but the implementation of the Public Health Program is a productive investment, and a prerequisite for the social and economic development. The weakest point of the reform is that these programs are not considered to be important by the majority of the decision-makers, and they simply "don't believe in" the importance of prevention, screening[67], influencing of lifestyle.[68] The flops of the programs originate in the hospital focused, treatment committed thinking, inherited from the socialist value ranking, where not the health itself, but the capacity of health care facilities represented the development in the sector.

The long-term public health programs have been rewritten and changed frequently, thus the programs can hardly be planned for more than one year. The lacks of the present public health programs determine the health problems of the country for a twenty years time. From the point of legislation the prevention appears only in the protection of non-smokers[69] and in the numerous EU directives harmonized in the framework of "standards of health and safety at work."

3.2. What have we reached?

If we want to prove that the governments following each other conducted huge transformation of the Hungarian health system, we can compare some institutional and legal characteristics. The great changes of the 18-20 years of the reform are shown in [Table 3], concentrating on the state and governmental interest in the reforms.

- 240/241 -

Table 3

Main changes of the actors and main changes in the role of the actors in the Hungarian health care system from the mid '80s

| Elements of comparison | Mid '80s | 2006- |

| Responsibility for organizing and maintaining the health services | State | Generally: local governments, exceptionally: the state (listed in the Health Insurance Act)[70] |

| Basic values | Egalitarianism | Equality, equity, cost- effectiveness |

| Professional supervision | Direct governmental supervision, ministerial orders are compulsory | Supervision and control by law and administrative procedure, self-governance through the by-laws and the leading role professional colleges |

| Organizational supervision | Direct governmental supervision, the "agents" of the compulsory ministerial orders are the local councils | Legal norms for supervision and the owner's supervision |

| Ownership | Exclusive state ownership | Mixed system of ownership |

| Measuring efficiency | Volume of infrastructure development, number of hospital beds, number of physicians | Budgetary balance, hospital and quality standards[71], lessening of the nursing days, proportion of the one-day surgery |

| Competency of the management | Low competence physicians are the leading managers | Management board with a responsible general manager, wide range of competence in local decisions |

| Education of the management | Medical education and political dependability | Education in health management, frequently political dependability |

| Financial resources | State budget | Compulsory health insurance contribution and health tax[72], mandatory co-payment (fee |

- 241/242 -

| for appointment and fee for in-patient day)[73] | ||

| Development, payment | Informal (political) negotiations, discretional decisions of the central administration | Informal (political) negotiations in the Parliament mixed with open application system, EU systems of application for development resources |

| Health service structure | Hospital care centered | Slow move to the out-patient and one-day surgery, slow move to the necessity based services (geriatrics, hospice, long-term nursing, rehabilitation) |

| Quality control in the system | No systematic quality control, national institutions play a leading role also in ranking the institutions; strong administrative and professional control of communicable diseases and epidemiological situation | Licensing of the providers on the basis of minimal requirement[74], compulsory liability insurance, medical inspectorate, supervision by the health insurance administration and its Supervisory Authority, mandatory quality management systems at the providers |

| Position of the physicians | Employee for low, fix income, money under the table, part-time private office after the working hours | Public service employees for low, fix income, money under the table, at the same time possibility of private health enterprises |

| Position of the patients | Paternalistic, almost hierarchic connection with the staff and the institution, narrow competence for decision-making, some criminal accusation and practically none of liability suits for professional misconduct | Legally based patient's rights, free choice of physician (GP) and the care provider, restrictions of the service choice in the framework of compulsory insurance, growing number of malpractice lawsuits with more damages |

- 242/243 -

| Professional organizations and interest representation | The monopolistic position of the only trade union with relatively weak capacity of interest representation | The professional chambers had a compulsory membership with strong rights and competencies in decision-making. In 2007 the mandatory membership has been terminated. Now there is no generally accepted "one- voice" professional organization[75]. |

| Civil organizations, NGOs | Practically not existing | Miscellaneous structure with only a few NGOs covering the whole country, their financial resources primarily from the state budget. |

| Civil control and participation in the operation of the health care providers and supervision | There's no civil participation | The health committees of the local governments and the hospital supervisory boards[76] are present in the system with weak competencies, and the National Health Council[77] on the governmental level |

4. Phases of legislative reforms and its connection with the EU accession

4.1. Chronology of the reform legislation

The chronology table [Table 4] shows the picture of the returning elements of the reform, which were never implemented either because of the budgetary shortage, or because of the short-term interests of the decision makers (public health programs). It is clearly seen, that the political changes and governmental political changes were also mirrored in the health legislation.

- 243/244 -

Table 4

First freely elected government

| 1990 | Health care: on compulsory insurance basis |

| 1990 | Ownership of health facilities transferred to local governments - Act on Local Governments |

| 1991 | National Public Health and Chief Medical Officer's Service (formation act) |

| 1991 | Private investments (pharmacies, etc.) - contracting for public services |

| 1992 | Act on the protection of conception (regulating also the legal conditions for artificial abortion) |

| 1992 | Health Insurance Fund separated from the Pension Fund (tripartite self-governing body elections in 1993) - health insurance card[78] |

| 1992 | Act on Public Employees - staff of the local governmental and state health facilities become public employees |

| 1992 | "Functional" privatization of GP, capitation in the payment |

| 1993 | Paying reform of the Health Insurance (performance related score based payment changes the global budgeting) |

| 1993 | Mutual Health Insurance Funds for non-for-profit, supplementary health services are authorized |

| 1994 | Reform of professional organizations (compulsory membership in Chambers) |

| 1994 | National Health Promotion Strategy is adopted by the government |

Bokros-package

| 1995 | Co-payment regulation (dentistry, patient transportation) |

| 1995 | Insurance package changes: occupational health withdrawn from the package |

| 1995 | Capacity reduction starts (unconstitutional for limiting the local government's autonomy) |

| 1996 | Act on Normative Capacity of Public Health Facilities - 20% reduction |

- 244/245 -

The new Health Act, Health Insurance Act and other "big legislation"

| 1997 | New Health Act |

| 1997 | New Health Insurance Act, 1997: first steps for "insurance package" |

| 1997 | Act on Data Protection of Health |

| 1996, 1997 | Regulation of public capacity: licensing and minimal requirements, quality assurance |

| 1998 | Act on Pharmaceutical Products |

| 1998 | Act on the protection of non-smokers |

| 1998 | Abolition of the Health Insurance Self-Government |

| 1998 | Introduction of fixed additional health contribution |

| 1998 | Health contribution is collected by the tax administration |

| 1999 | Managed care pilot project |

Fragmented legislation: GP praxis, capacity, hospital and privatization and the failed legislation

| 2000 | GPs' right of autonomous practice management, |

| 2000 | Act on Mediation in the Health Sector |

| 2001 | Capacity legislation changes |

| 2001 | National health promotion strategy - right-wing government |

| 2001 | First institutional and personnel act |

| 2002 | National health promotion strategy (left-wing government) |

| 2002 | Act on ratification of the Oviedo Bioethics Convention |

| 2002 | Ministerial decree on the one-day surgery |

| 2003 | Second institutional act |

| 2003 | Act on Health Personnel |

- 245/246 -

21 steps form "100 steps" program and the reform under free-democrat leadership of the Ministry of Health

| 2004 | New legislation on minimal standards of health care services, reformed license system, new license for each provider in the country |

| 2004 | Reform of the professional inspectorate system |

| 2004 | National professional guideline revision program - issuing the first 100 pieces until the end of 2005 |

| 2004 | Reform and reelection of the professional colleges |

| 2005 (April) | "100 Governmental Steps" Program - "21 Health Steps" - main strands: • Reform of emergency services • National complex program against cancer • Primary care and out-patient service changes: micro-regional program, Group-praxis, centralized on-call services, performance related payment in primary care • Generic drug program, reform of prescription and promotion • Equality of access, strengthening the quality control • Insurance contribution system: quitting free-riding • Fairness of the system: insurance package content clarification, market elements for the extra personal needs |

| 2005 | National Oncology Development Program, "Future of our Nation" Program (pediatrics) |

| 2006 | Act on Professional Medical Chambers (Act 97 of 2006) - abolition of public authorities |

| 2006 | Act on the Economic and Safe Supply Of Pharmaceutical Products And Medical Devices (Act 98 of 2006) |

| 2006 | Act on the Supervising Authority over the Health Insurance Sector (Act 116 of 2006) |

| 2006 | Act on the structural development of the health care system (Act 132 of 2006) - capacity reduction and structural redistribution of capacities |

| 2007 | Fixed co-payment - per attendance of out patient services, per day at in-patient facilities |

| 2007 | Reduction of health insurance services (extreme sports not covered) |

| 2007 | Introduction of a public insurance entitlement contribution payment monitoring system |

4.2. Accession to the European Union

In a Europe that is becoming more integrated, the place of health care in European law is increasingly unclear. From the earliest days of the European Community, health care has been seen as a national matter.[79]

- 246/247 -

From a European perspective the health care systems are also basic elements of the economy system of the countries. "One of the greatest paradoxes of public health in the European Community nowadays is that while the population has never been healthier, the demand on Member States' health systems and thus on the tendency towards increased expenditure, is ever-growing. The expenditure on health is being constantly forced upwards. The Community's public health strategy has been developed against this background and is designed to reflect and respond to the problems which are putting pressure on Member States' health services: pressure which is likely to become even greater in the future."[80] In Hungary the mortality and morbidity situation is worse that in the majority of the Member States, so the professional and financial burden is even more expressed.

The paradox of the EU accession was, that financial resources (Phare Programs) were exclusive for the health issues, but awaited the modernization of the systems, which were supervised by the minister of health.[81] The health policy and the public health reform was on the harmonization list with so important regulatory measures, such as

• Protection of non-smokers

• Chemical safety, environmental health

• Food safety

• Health and safety at work

• Consumer protection.

The harmonization of 200 directives and other legislative instruments had some elements, which can be regarded as a reform. The National Public Health and Chief Medical Officer's Office had to change most of their proceedings, the specialty training and exam system was changed, the drug registry system changed a lot, just to mention a few examples having a deep impact on the care system.

The scope of the Amsterdam Treaty[82] covers more health care issues than ever before. The general protection of health was underlined and the "free movements" were helped also in the health sector as well. Now the cell, tissue, organ transplantation, the blood transfusion issues are covered by directives, the European Center of Disease Control (EuroCDC) has the role of a supranational

- 247/248 -

epidemiological information center and clearing house, the central registration of numerous pharmaceutical products, the European emergency card for the health service accession of the member state citizens forms a partial health (care) policy in the EU.

4.3. The ongoing reform - denial of the prior results and continuity

The permanent budgetary deficit of the Health Insurance Fund, the lack of the individual insurance elements in social security, and the malfunctions of the Health Insurance Administration might lead to the impression that nothing changed in the Hungarian health system, and "THE REFORM" is still missing. We presented, that huge steps were made to change the basic structure and behavior of the health actors, however, there still is a gap between the legislative, administrative, health policy and constitutional modernization and the modernization of the health care infrastructure and devices which was more modest, than the needs of a high quality care system today.

For the financial burden of the Fund the strongest tension for the government is the sustainability of the budgetary balance of health contributions and expenditure, which has been unsuccessful from the setting of the Fund. When we try to find the intervention points, we can see that the relations of the health sector actors changed a lot in the provider-patient connection and in the Health Insurance Administration-provider connection, too. People don't feel the big reform, because the insured patient-Health Insurance Administration connection hasn't changed. Some new technical elements were introduced (e.g. the social insurance personal code number and the insurance identity card), but the budgetary correction of 1995 could only reach a small result or temporary changes (supervision of the services, introduction of co-payment, etc.). The motivation of the government for the big (shocking) interventions into the patient's insurance contract is understandable; but the actual steps can be questioned.

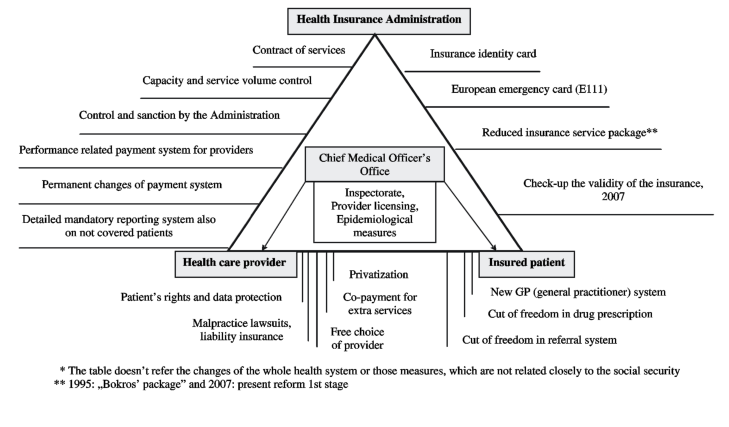

The next table [Table 5] shows the health insurance actors' relations and some important reform measures in their connection. The "emptiest side" of the social security relation triangle is the patient-insurance administration side. On this table two basic actors cannot be seen: the government and the local governments, we've examined them before. Analyzing the reform process we see, that the former stages of the insurance system reforms tried to close the gap between the income of the fund (free riders) and expenditure of the fund (capacity control, slight revision of the insurance services). Now we cannot see the result, the instrument of the potentially better cost-effectiveness became the goal of the reform: a limited and controlled market in the social health insurance sector with the multiplied and somehow competing insurance administrations under the umbrella of the uniform social security health insurance system, flat rate of contribution, and centralized redistribution.

- 248/249 -

Comparing the main messages of the health program of the "100 steps" project and the Green Book of the reform program in 2006, a contradiction can be seen. There are more conceptual elements in the "100 steps" with small steps towards them, while the Green Book[83] is rather a list of measures to correct several dysfunctional points in the operation. Three elements are mixed in the document: reform elements for the health sector, the instruments to reach the goals of the Program of Financial Convergence of Hungary and the practical tasks of the health administration. The problems and the present situation is presented in details, the measures to be taken are presented in a "list to do" form, but the planned new situation is not defined. This may have happened because the main political and professional question the radical, market oriented reform of the social health insurance system wasn't blueprinted and decided. Without the broader sense, it was impossible to formulate a coherent program.

Some say, that the blueprint of the reform of the insurance was even formulated in a draft form of a bill.[84] I don't agree with this opinion. The document didn't have any detailed explanatory text, or impact examination annexes, or even alternatives at some points. It didn't present the interactions with other elements of the health system, so it was rather an option for discussion, than a bill to vote for. This bill recalled the text of the drafted bill on the "Regional Managed Care System[85]" which failed on the governmental discussion level in 2005[86]. The same problems are not solved in the two documents and the same questions are not answered. The reform legislation must answer them in 2007 and in the following years.

The re-born illusions ("health is not for business") about the state health system question not only the ongoing reform steps and plans, but the whole two-decade reform. The re-nationalization of private or privatized institutes or only those in the ownership of non-medical professionals, or the only corporate forms would be discriminative thus unconstitutional in a market economy and practically impossible.

Without the clear vision of the reformed system it is hard to determine the competencies and the limitations of the market actors as well as the long-term state responsibility for the health system.

- 249/250 -

Table 5

Changed or reformed elements in the social security health insurance actors' relations from the early '90s

- 250/251 -

5. Deficits of the two-decade reform, lack of legislation

In 1989 neither the patients nor the health professionals were satisfied with the operation of the Hungarian health care system. What has been changed?

We listed many elements of the sector which have been changed, but the overall feelings, the general (negative) opinion about the care system remained the same. There are subjective and objective causes for the opinions. The most important subjective cause is that people were promised to enjoy the free of charge, high quality and accessible care in the socialist regime, and they want to get it irrespective of the new social, economic conditions. The other element is that the professionals evaluate quality by the number of complications, the lessening of nursing days, the availability of good diagnostic and therapeutic technologies, but the patients evaluate on grounds of the health facility buildings, the toilets, the comfort, and in this field the breakout has been being cancelled. The health staff was underpaid in the socialist regime, and this is the situation even now (the gratitude money is one of the most stabile elements in the sector).

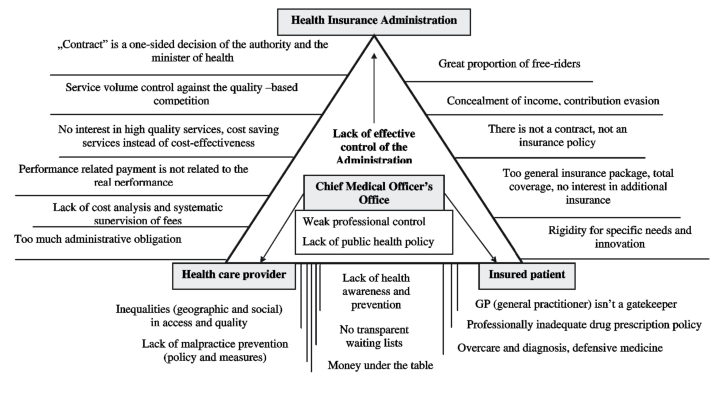

The [Table 6] shows the negative elements or unsolved problems of the health insurance actors' relation. Beyond those a few basic issues can be raised to be solved in the close future.

Difference between health system and health insurance system

People and the decision makers do not take into consideration, that there is an expanding health care market partially buffering the health insurance sector. The uniform health insurance regulations may find a balance in offering good quality services to all, in a regulated, but clearly defined non-insurance service. This could be based on the evidence based medicine principles.

State's role

In the reform the only redefinition of the state's responsibility in the health sector was the legislation of the Health Act. Without the supervision of the role none of the reforms could be successfully finalized.

Long-term thinking instead of lack of continuum

The health reforms need long-term planning, consequent execution, permanent monitoring. In the Hungarian reform history none of the programs followed this scheme: the preventive programs didn't get the resources for execution and programs were changed frequently, nobody remembers them after 10 years, when the first results should be seen.

- 251/252 -

Lack of professionalism

In the EU countries managers, economists, lawyers, administrative professionals are trained in public health, and they never work without the help of professional health organizations or expert physicians. In the Hungarian reform the professional expertise, the evidence based medicine protocols and medical ethics are accidentally used by decision makers. The weak professional inspectorate leads to a slow recognition of unwanted effects of the decisions.

The unclear status of the NHIFA

The NHIFA is over-centralized, it operates like an authority, the contracts are one-sided and in a lot of cases there is no opportunity for appeal against its decisions, which aren't formulated in a resolution, not even in a written form. There's no effective control over the NHIFA.

- 252/253 -

Table 6

Problems and deficits of the Hungarian social security health insurance actors' relations at the beginning of the 21st century

- 253/254 -

6. Conclusions

The practice of medicine in the modern era is beset with unprecedented challenges in virtually all cultures and societies. These challenges center on increasing disparities among the legitimate needs of patients, the available resources to meet those needs, the increasing dependence on market forces to transform health care systems, and the temptation for physicians to forsake their traditional commitment to the primacy of patients' interests.

In the (relatively well) developed countries the basic principles of an optimal health care haven't been changed in the recent decades, consequently the main, general goals of the reforms to fulfill these principles are also similar. The instruments to reach these aims can be and should be disputed and the interactions of the different measures should be examined before voting and executing the reform legislation[87].

The Hungarian health care reform is not a story of success. It is not accidental that (together with the Minister of Finance) the health ministers spent the shortest time in ministerial position. In most reform documents we find a detailed characterization of the present situation, sometimes we find the general goals (equity, cost-effectiveness, etc.) and never the analysis and consequences of the former (unsuccessful?) reform steps.

As we listed the acts of the last 18-20 years we see that really weight matters were voted in extremely short time. Thus the background consensus or the detailed, well-organized discussions before, and clear, convincing explanations for the execution are missing as well as the adequate preparatory period for the execution of the new regulation.