dr. Csaba Koppány Varga[1]: The Role of Product Designations in Shaping Competitiveness and Consumer Decision-Making (JURA, 2024/4., 133-146. o.)

I. Introduction

The development of the Hungarian food economy[1] has long been dominated by faith in the omnipotence of efficiency and productivity.[2] Following the turn of the millennium, however, it soon became obvious that the competitiveness of the Hungarian food market - not independently from the restructuring of the world market, the globalization which has hit the aforementioned sector, and the breakthrough of developing countries, mainly Turkey and China - is no longer more than wishful thinking.

As the early 2000s unfolded, it became increasingly clear that this traditional model of development faced mounting challenges. The first signs of strain were already visible in the aftermath of Hungary's accession to the European Union in 2004, when domestic producers were suddenly required to compete within a much broader and more dynamic market framework. EU membership did bring certain advantages, such as subsidies and access to new markets, but it also exposed inefficiencies that had been previously concealed by protectionist policies and state support.

More broadly, global trends began to reshape the playing field for food economies around the world. The restructuring of international food markets, accelerated by technological advances and the intensification of global trade networks, introduced new pressures. Countries that had previously held peripheral roles in food production-most notably Turkey and China-began to assert themselves as formidable competitors. These emerging players, often benefiting from lower labor costs, rapidly modernizing infrastructure, and increasingly efficient supply chains, were able to offer products at prices that undercut European producers. For Hungary, whose agricultural exports had once been a point of national pride, this shift was disorienting. The comparative advantage it once enjoyed in certain staples and processed foods began to erode.

In this context, the assumption that efficiency and productivity alone could guarantee competitiveness started to unravel. The Hungarian food sector, while still boasting skilled labor, rich agricultural traditions, and favorable natural conditions, found itself ill-prepared for the complexities of the globalized market. Strategic shortcomings-such as limited innovation in product

- 133/134 -

development, insufficient marketing strategies, and weak integration into value chains-became increasingly evident. The dominance of multinational corporations within the domestic retail market also placed local producers at a disadvantage, limiting their bargaining power and market access.

Thus, by the end of the second decade of the 21st century, a more sobering view began to take hold. It became clear that competitiveness in the global food economy was no longer simply a matter of producing more, faster, or cheaper. The structural realities of globalization, coupled with shifting consumer preferences and evolving trade dynamics, necessitated a broader rethinking of priorities. The dream of a revitalized, competitive Hungarian food economy remained - yet it now required a more nuanced strategy, one that could hold space for change, innovative thinking, and efficient use of the national resources, including the use of designations of protected origin and trademarks. As the research below indicates, these goals have so far seldom been reached (however not for the lack of trying by the competent Hungarian authorities).

II. The contribution of intellectual works

The question is whether Hungary is taking advantage of the benefits offered by the protections of origin, geographical indications and trademarks, and whether the domestic legal environment is sufficiently supportive.

It is hardly debatable that intellectual property is one of the key factors of competitiveness. The European Union Intellectual Property Office (EUIPO) and the European Patent Office (EPO) have launched a common project in 2013 with the goal of determining how much do intellectual property intensive branches contribute to the European Union economy.[3] The project regards those branches as intellectual property-intensive "within which IPR per employee is above average compared to other IPR sectors."[4] Such branches are typically found in the processed goods industry, and the technological and business service sectors.

The research has come to the conclusion that in the period between 2011 and 2013, 42.3 percent of the EU economy and 27.8 percent of employment came from the intellectual property-intensive branches. The most added value was generated by the PO-intensive and the trademark-intensive branches, in annual average the share of the total EU GDP was 35.9 percent in the former, and 15.2 percent in the latter. However a significant contribution was shown in the case of the plant variety right-intensive and the geographical indication-intensive branches as well: in the former ones, the annual average value added relative to GDP was 51 710 million Euros (0.4 percent of the total GDP), and in the latter ones, 18 109 million Euros (0.1 percent).[5]

In general it can be stated that the added value per employee in such branches is higher than in other areas of the economy. In addition, the wages are higher too: in IP-intensive branch-

- 134/135 -

es, the sum of the weekly average wage is 776 EUR, as opposed to the 530 EUR of other branches not of that nature, that is, the difference is 46 percents. This "wage premium" amounts to 48 percent in the branches using trademarks and 31 percent in those using geographical indications intensively.[6]

Graph 1: EU foreign trade in the IP-intensive branches, 2013.

| Export (million EUR) | Import (million EUR) | Net export (million EUR) | |

| Trademark-intensive branches | 1 275 472 | 1 261 002 | 14 470 |

| Industrial design-intensive branches | 945 084 | 701 752 | 243 332 |

| Patent-intensive branches | 1 231 966 | 1 157 909 | 74 057 |

| Copyright-intensive branches | 119 554 | 102 389 | 17 165 |

| Geographical designation-intensive branches | 12 923 | 1 335 | 11 588 |

| Plant variety right-intensive branches | 5 065 | 5 369 | -304 |

| IP-intensive branches, total | 1 605 516 | 1 509 099 | 96 417 |

| Non-IP-intensive branches | 117 561 | 256 048 | -138 487 |

| TOTAL EUROPEAN UNION TRADE | 1 723 077 | 1 765 147 | -42 069 |

Source: EUIPO 2016, 11.

In the research they examined the role of IP-intensive branches in the EU foreign trade as well. In 2013 the European Union had a trade deficit amounting to about 42 billion Euros, this accounted for 0.3 percent of the GDP. In the same year the IP-intensive branches produced about 96 billion Euros of foreign trade surplus. However, there was a fairly large variation by sector. As is shown on the table below, considering all intellectual property-intensive sectors the export value was 106 percent of the import value, in the geographical designation-intensive sectors, the situation was far more favorable: this ratio was 986 percent.

Based on the information above, it can be concluded that the contribution of products distributed with trademarks and geographical designations of origin is significantly greater than that of other products.[7] A research from 2008 rated national policies regarding geographical designations and their efficiency. According to the final study, by using geographical designations and protections of origin, a surchange of at least five but up to three hundred percents can be reached, however it is also true that the the cost implications of the designations are also significant, so higher profits may not necessarily be realized. Despite this fact, two-thirds of the tested products achieved a higher profit margin - two and a hundred and fifty percent higher - than the reference products.[8] A research conducted in 2013 compared the profitability of Hungarian pálinka distilleries; those distrilleries that were producing pálinka with Community geographical indications were to a small extent more profitable than their peers who did not use such indications. The researchers also examined the effects of origin protection on an international scale, however, they were only able to indicate the

- 135/136 -

lack of competitiveness of the Central Europe region, especially Hungary. It was established that "no correlation can be demonstrated between Central European distillates with protected origin and their comparative competitive advantages."[9]

Based on the above, protection of origin and the use of geographical indications do not in themselves guarantee either domestic or foreign success. Geographical indications express a product's quality by indicating its geographical origin. The indication of geographical origin as a way of expressing quality has been known for several thousand years; this is especially true of the food industry. Legislators today try to ensure the truthfulness of the indications of geographical origin by several means and legal institutions. These legal institutions fall partly into the field of competition law and partly into the field of trademark law - even overlapping and complementing each other - and in addition to all this, there is a sui generis system of geographical indications. The protection of geographical indications in the European Union develops in a unique way, as in the case of industrial (e.g. handicraft) products, the regulation remains within the competence of the Member States, while the protection of geographical indications of agricultural products and foodstuffs has been settled at the Community level. The legal protection provided by geographical indications - including the two types of geographical indications, designations of origin and geographical indications and traditional designations that can be protected - covers the entire territory of the European Union. One of the most important features of this legal protection is that after registration, protected names may not become ordinary names or common names. Designations of origin, geographical indications and traditional speciality indications for agricultural products and foodstuffs are protected under Regulation (EU) No. 1151/2012, and the procedure for protection is the same for all applicants from all of the member states. The procedure leading to the acquisition of European Union protection consists of a national and an EU level stage.

Following Hungary's accession to the European Union, up until 1 August 2009, the national stage consisted of two procedures: first the product specification for the application for protection had to be submitted to the ministry (the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development [Földművelésügyi- és Vidékfejlesztési Minisztérium], FVM), which the FVM published in the Agriculture and Rural Development Bulletin in case it was accepted. If no objections were received to the product description, the FVM - after seeking the opinion of the Hungarian Council for the Protection of Origin - issued a professional authority resolution on the acceptance of the product description. Only after all of this was the producer group able to submit its application for Community protection to the Hungarian Patent Office [Magyar Szabadalmi Hivatal] (MSZH), attaching the FVM's position statement. The MSZH examined the application based on industrial property rights consider-

- 136/137 -

ations and made a favorable decision if the application did not conflict with the names of plant varieties, animal varieties, or previous trademarks, and there were no other reasons excluding protection. Following the MSZH's positive decision, the FVM forwarded the application to the European Commission. The partitioned nature of the Hungarian domestic regulation did not benefit the applicants; on the one hand, it made the administrative procedure unreasonably complicated, costly and time-consuming, and on the other hand, it also created a disadvantageous situation in terms of the priority of the geographical indication.[10]

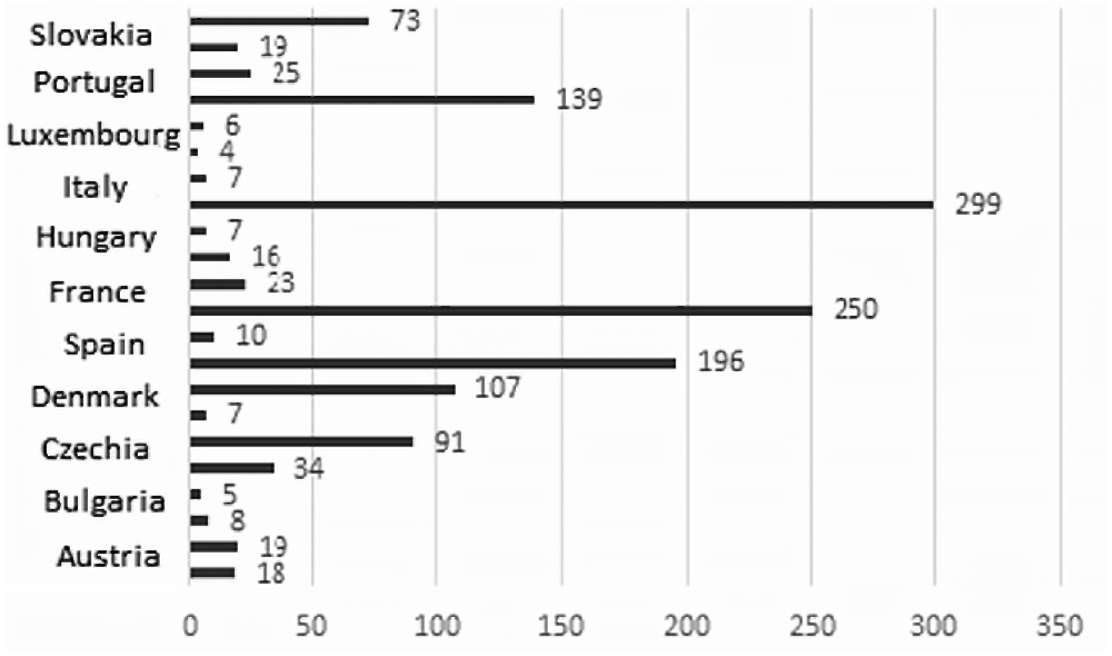

Graph 2: Number of designations of origin, geographical indications and traditional speciality guaranteed indications for foodstuffs in the countries of the European Union, as of 1 August 2019

Author's own edit based on the European Commission database, 2019

Act XXVII. of 2009 simplified the process somewhat by abolishing the double partitioning of the national stage. According to the current rules, applications for EU protection for foodstuffs -as well as wines and spirits - must be submitted directly to the Ministry of Agriculture; the Minister - based on the opinion of the Hungarian Intellectual Property Office - decides on the admissibility of the application and whether it can be forwarded to the Commission.[11]

On 1 August 2019, a total of 1,363 registered trademarks were listed in the European Union Register.[12] The number of products with protected origin - or other similar protections - depends on the climatic conditions of the given

- 137/138 -

country, and even more on the mechanisms of the previous origin protection system.[13] As the graph below shows, in the case of Hungary, a relatively small number of such product indications were registered, and neither is there a large number of applications presently under consideration.

Boros, analyzing Eurobarometer results in his 2015 research, has come to the conclusion that the awareness of product labels and, in this context, the consumer perception of regional products is not the same in individual member states of the European Union. In southern countries, locally produced products are more popular and their support for protection of origin systems is higher. In contrast, in northern member states, trademark use is more dominant. Geographical indications of origin primarily are of more value to the conservative, more right-wing, older, rural consumers.[14]

Place names and geographical names can also be registered as trademarks, but this is ruled out if the given designation is protected by a trademark or contains a designation that is protected by such a trademark, and given the reputation and long-standing use of this earlier trademark, the use of the geographical indication would be misleading with regard to the given product. However, if a geographical indication has been registered, a subsequent conflicting trademark application must be rejected without consideration.[15] Literature concerning the collision of trademarks and geographical indications is trying to solve this contradiction by working out various principles.[16] For example, Burkhardt Goebel and Manuela Groeschl point out that geographical indications are mostly expressions of the cultural heritage of a region or nation, or of the public good, and thus "stand above the private property embodied in a registered trademark."[17]

Regarding food industry products, the most suitable options are the collective trademark and the certification trademark. In the former case, the trademark distinguishes the goods and services of the entitled association from those of others, on the basis of the quality, origin or other characteristics of the goods and services designated by the collective trademark. The right to use such a trademark is based on membership in the association that owns the trademark, although the right to use it does not automatically come with membership. A certification trademark, on the other hand, is a trademark that distinguishes goods or services with a specific quality or other characteristic from other goods or services by certifying their quality or characteristic. While in the case of a collective trademark, the conditions for the use of the trademark are laid down in its regulations by the owner, in the case of a certification trademark, a person or body independent of the trademark owner certifies the quality of the product - and this is precisely what gives the certification trademark its competitive advantage. In the European Union, trademarks can be registered on four levels. The choice is determined by the business plans of the given enterprise. If someone wants to obtain trademark protection in only

- 138/139 -

one EU Member State, whether it is the country where they are established or another in which they intend to trade, it is sufficient to file their application with the intellectual property office of the relevant Member State. Anyone wishing to obtain trademark protection in Belgium, the Netherlands and/or Luxembourg can file their application with the Benelux Office for Intellectual Property. This is the only regional intellectual property office in the European Union that offers trademark protection for the territories of these three countries. A business that needs trademark protection in several EU Member States can file its trademark application with the EUIPO. The national, regional and EU systems complement each other, and work in parallel with each other. European Union trademarks enjoy the same protection in each member state.

The fourth stage of trademark protection is the international level. The applicant can use their national, regional or European Union trademark application to request an extension of protection to any country that is a signatory to the Madrid Protocol. The number of certification marks registered in Hungary and used in the food sector - in August 2019 - is approaching fifty, and in addition, the number of marks used on food is around eleven thousand. In addition to serving to identify goods and services, the trademark refers to the manufacturer of the product or the service provider, and also acts as a kind of quality indicator, informs consumers - and, of course, competitors - and in the optimal case encourages consumption, and functions as a kind of marketing tool. However, the current "labyrinth" of trademarks seems to be destroying this very competitive advantage: due to the large number of certification marks, "the consumer is faced with an overload of information that makes or could make these marks trivial."[18]

In addition to trademark protection and the system of sui generis designations of origin and registered geographical indications, there are origin protection solutions in Hungarian law that cannot be included in any of these systems, but there are points of connection: the Hungarian Product Decree was created in connection with geographical origin, and the protection of Hungarian products is ensured by a certification mark created specifically for this purpose.

The international trend is trademark harmonization efforts, and these are contradicted by regional collective (mostly considered a kind of hybrid) trademark solutions. It is true that the Hungarian product regulation, or even the Hungaricum law, is not without precedent.

In Western Europe, the Euroterroirs (European Territories) program was launched at the end of the 1980s on a French initiative. The goal was for each European Union member state to create a collection of its own traditional and regional foods, thereby promoting the economic utilization of domestic foods. The base concept of the Euterroirs program was that traditional foods should be regarded as part of the national cultural heritage, and be provided with a special protection. The Japanese exam-

- 139/140 -

ple is also instructive: in 2006, the Chiiki ("region") trademark was introduced in the island country, which also bore the characteristics of geographical indications. The registration of the Chiiki trademark can be applied for by an organization that provides its members with the use of the trademark based on a uniform set of criteria. The condition of the protection is that the given sign is well known and recognised by consumers, that it acquires recognition in the course of long-term commercial use, and that the geographical name has a secondary meaning in addition to referring to the geographical area. The Chiiki trademark differs from geographical indications in that there is not necessarily a connection between the origin of the given region and the quality or other characteristics of the product/service. The undisguised goal of the trademark monopoly created by the law is to strengthen the Japanese economy. Although the law does not preclude a foreign organization from filing such a trademark application, it is obvious that such a trademark has no significance for foreigners.[19] The Hungaricum trademark is not a certification trademark, it does not certify the quality of the given product or service in itself; rather, it can be interpreted as a kind of geographical indicator, which guarantees the geographical origin of the product or service and its connection to Hungary. It is therefore not difficult to discover the similarity between the Chiiki trademark and the Hungarian product trademark and the product marking system established by the Hungaricum Act.

Graph 3: Trademark of the "Basic Level"

Source: magyarmezogazdasag.hu

If the goal is to make the Hungarian food industry competitive abroad as well, then these solutions are of little practical use. In the case of food industry entrepreneurs targeting EU markets, it seems more expedient to apply for an EU trademark application or to apply for EU protection for their geographical indications. At the same time, these hybrid trademarks can serve as a suitable tool to boost domestic consumption. However, it is also a fact that the large number and variety of distinctive signs does not currently facilitate consumer decision-making. Having recognized this, the government came to the decision of creating a new two-level trademark system by the name of "Kiváló Minőségű Élelmiszer"[20] (Excellent Quality Food).

According to the announcement of the Ministry of Agriculture[21] in June 2019, the KMÉ trademark system has

- 140/141 -

two levels. The first is the "Basic Level," which can be applied by any producer (farmers, small producers, small, medium-sized and large enterprises engaged in food production and processing, food retail companies distributing private label products) if they have a FELIR ID. The applicant must demonstrate the high quality of the product and the place of production will be audited during the selection process. Producers who have been awarded the "Basic Level" can apply for the "Gold Level" trademark with their best product. The safety, quality and popularity of the product are examined by an independent body (the National Food Safety Office) within the framework of a "product muster." Producers are entitled to use the trademarks for three years.

Graph 4: Trademark of the "Gold Level"

Source: magyarmezogazdasag.hu

"Although the market is overcrowded with trademarks, there is still a demand for a new trademark that provides a credible and genuine guarantee of outstanding quality," stressed the State Secretary who announced the new trademark system.[22]

At this point the question inevitably arises: what do consumers think about foods with designations of geographical origin, can Hungarian consumers distinguish domestic EU trademarks from other trademarks related to quality certificates? According to previous studies, Hungarian consumers "only recognize foods with geographical indications in the bonds of tradition"[23] because "EU trademarks are lost in the sea of Hungarian quality certificates,"[24] and "this decision-making confusion causes the failure of certain trademarks to be detected or unsuccessful."[25] A 2013 survey conducted by the Research Institute of Agricultural Economics has come to the conclusion that in general, consumers deem trademarks and food designations to be useful, think products with these designations to be safer, and in some cases, this greatly influences them in their choice of products. The research however also indicated that Hungarian consumers have no accurate knowledge regarding trademarks and other designations. A similar result was reached by Zoltán Szakály in his 2016 analysis, where he found that barely 35 percent of Hungarian consumers look for the trademarks on products. During the survey, hardly a few of those questioned were able to give an example of trademarks spontaneously. The Hungarian Product trademark is in first place, most people (26.1 per-

- 141/142 -

cent) mentioned it, while in the case of the other indications, none of their mention rates reached ten percent. All this indicates an extremely low level of spontaneous knowledge.[26]

Graph 5: Ratio of spontaneous mentions of designations and trademarks among the Hungarian consumers (2009, 2015, 2016 data, in %)

| Trademark, designation | In 2016 | In 2015 | In 2009 |

| Hungarian product | 26,1 | 34 | 30.5 |

| Forum of Excellent Goods (Kiváló Áruk Fóruma) | 5,4 | 5.6 | 7.1 |

| Hungarian poultry | 4,6 | 2.0 | under 5 |

| Excellent Hungarian Food | 4,2 | no data | 5 |

| Domestic product | 1,6 | no data | no data |

| Crown eggs (Koronás tojás) | 0,4 | no data | no data |

Source: storeinsider.hu 2017

As the table above shows, the mention rate of individual trademarks has decreased compared to 2009, meaning that the awareness of trademarks has fallen considerably even in half a decade. The low awareness - as Szakály also pointed out - can be explained by the increasing number of trademarks and by the fact that the names of the certification trademarks are quite similar to each other - for example, Hungarian Product, Domestic Product. Consumers are less and less able to distinguish between individual trademarks and are not even aware of which one certifies what. This leads to them becoming uninterested in the matter and no longer wanting to follow up on the individual designations: in other words, the trademarks in question are gradually losing their significance for the market. This is obviously not independent of the fact that the trademarks are not communicated properly. If the consumer cannot assess why a product with a given trademark is of value for money, they will make a purchase decision based on the price-performance ratio, and the added value of the trademarked products is lost. However, the studies also showed that, in contrast to the spontaneous mention of trademarks, the supported knowledge is high: the respondents recognized the presented logos in a high proportion and were able to name them. The awareness ranking in 2016 was led by the Hungarian Product trademark (89.8 percent), and the Excellent Hungarian Food trademark, which otherwise enjoys much greater marketing support, came in second place (83.9 percent).[27]

This difference in the degree of spontaneous and supported recognition of trademarks suggests that consumers have only passive knowledge of trademarks and other product designations. In addition, when customers encounter the logo in a point-of-sale environment, they are highly confident in recognizing it.[28]

In my opinion, the right direction is not to introduce new trademarks and food labels, but rather to support existing and established labels with strong

- 142/143 -

marketing activities. Therefore, in this approach, we may not be faced with a legal question. As Török has shown: "reaching consumers clearly plays a key role in the value chains of protected food products."[29] When purchasing a protected product of special quality or a hungaricum, the consumer is not simply purchasing a product. In line with this, Pallóné Kisérdi considers it essential to increase the awareness of products of special quality that are clearly identifiable and unique to us, in order to increase competitiveness in terms of traditional and regional foods.[30]

Graph 6: Supported awareness of trademarks and designations among the Hungarian consumers (2009, 2015, 2016 data, in %)

| Trademark, designation | In 2016 | In 2015 | In 2009 |

| Hungarian product | 89.8 | 90,7 | 90,0 |

| Excellent Hungarian Food | 83.9 | 64,3 | 71,9 |

| Hungarian poultry | 76.8 | 56,0 | 57,2 |

| Forum of Excellent Goods | 65.7 | 60,0 | 66,6 |

| Milkheart (Tejszív) | 56.3 | 25,9 | no data |

| Excellent quality pork | 49.7 | 27,3 | no data |

| Crown eggs | 48.5 | 36,5 | no data |

Source: storeinsider.hu 2017

Many emphasize the significance of community marketing in connection with origin protected products of special quality (for example: Ferenc 2009; Jasák 2014; Pallóné Kisérdi 2003; Panyor 2007; Szakály 2014).[31] Nótári points out that when buying hungaricum products, the consumer does not merely buy a product, but "tastes, flavor, tradition"[32] Adequate information for consumers is one of the most important principles of the food sector, which, together with the principle of traceability, guarantees the smooth functioning of the food market. With regard to EU legislation on food labelling and product descriptions, it is a directly applicable legal material, which is supplemented by domestic legislation. While the right of consumers to information takes precedence, this should not lead to an unnecessary increase in the burden on food business operators.

Various surveys show that consumers want to get as much information as possible about food, for example, in the case of meat-based foods, they are not only interested in where the animal was raised, but also in which country it was born and in which country it was killed. However, other surveys show that consumers are completely unaware of the additional burden this would mean for food business operators. In addition, they tend to make their purchasing decisions based on taste, shelf life, or even the price/value ratio. They may want to know on the level of principles in which country the cattle were slaughtered, but they are usually not willing to pay more for this extra information. All in all, the conclusion can be drawn: the safety of the food chain and the interests of consumers require that the information and

- 143/144 -

labelling regulations be sufficiently detailed and strict. However, the further tightening of the information and labelling rules will not bring any benefits beyond a certain point.

III. Summary

The European Union's legislation on food indications is extremely diverse. This also means that a food business operator entering the market must be aware of a number of legal requirements and must fully comply with all of them. The European Union's food safety policy focuses on protecting the health and well-being of consumers, ensuring the free movement of safe and healthy food and, in this context, the functioning of the Single Market. However, the legislative process launched in 2003 has resulted in a change of approach in that it has made traceability a priority and has done everything possible to ensure that this principle can be applied to the entire food production and processing chain, to all food arriving in and out of the EU. Therefore, the scope of the EU's food safety policy applies not only to the rules on food hygiene and the labelling of foodstuffs, but also to the standards that ensure the health and well-being of animals or even the health of plants, and provide protection against contamination caused by external substances, such as soil contamination and pesticides.

The food business operator is obliged to ensure that the foodstuffs comply with the relevant rules at all points of the food chain, and to this end, it is obliged to carry out continuous controls. It is obliged to ensure traceability, i.e. that it is possible to identify all persons from whom the food and food contact materials have been obtained. It is obliged to inform the consumer of all the data and circumstances specified in the law. Food information must be clear, accurate and easy for consumers to understand. Any kind of misleading communication should be avoided.[33] The fulfilment of the obligation to inform imposes a significant administrative and, in this context, a financial burden on food business operators. However, it is important to emphasize that the obligation to provide information in the strict sense is not an end in itself, and - in addition to informing consumers - it also serves traceability and food safety.

In my research, in addition to food designations, I dealt with trade labels that are important for the food industry. I established that the international trend is represented by the efforts of trademark harmonization, which are contradicted by regional collective trademark solutions (which can be considered as a kind of hybrid), such as the Hungarian product and the hungaricum label. My position is the following: if the goal is to make the Hungarian food industry competitive abroad, then the latter solutions are not suitable for that. For food business operators targeting EU markets, it seems more appropriate to apply for an EU trade mark application or to apply for EU protection for their geographical indications. At the same time, these hybrid

- 144/145 -

trademarks can serve as a suitable tool to boost domestic consumption.

Throughout this study, I have on various occasions noted that trademark alone is a deficient tool for boosting the competitiveness of the food economy, since the overabundance of such labels can incite consumers to make the wrong decisions in buying food products of quality. (Seeing that, as previously mentioned, they themselves are not inclined to remember trademarks, and are prone to making decisions based on other factors, such as price and taste. Therefore the quality of the product may or may not be accurately represented by the given trademarks and designations).

Considering these factors, it is important - not only to the regulating authorities, but to the food producers and the consumers as well - to properly assess the role of using trademarks and designations as tools for bolstering the popularity and/or competitiveness of food products, and not to over- or understate their capacities. ■

NOTES

[1] The role of food economy is to satisfy domestic food needs, and to produce foods and food industry ingredients. In our country it plays a vital role in foreign trade, in certain parts of the country, it employs a significant percentage of the population, and contributes to rural development as well.

[2] Boros Péter: Regionális élelmiszerellátó rendszerek kialakításának és működtetésének társadalmi-gazdasági környezete. [The socio-economic environment for the development and operation of regional food supply systems.] Doctoral dissertation. Budapest, Corvinus University of Budapest, 2015. 7. http://phd.lib.uni-corvinus.hu/867/17Boros_Peter.pdf

[3] European Union Intellectual Property Office (EUIPO) (2016): Intellectual property rights intensive industries and economic performance in the European Union. Industry-Level Analysis Report, October 2016, Second edition Executive Summary. 3. 7. https://euipo.europa.eu/tunnel-web/secure/webdav/guest/document_library/observatory/documents/IPContributionStudy/performance_in_the_European_Union/eperformance_in_the_European_Union_sum-hu.pdf

[4] Euipo 2016, 7.

[5] Euipo 2016, 8.

[6] Euipo 2016, 9.

[7] This is also the case with food products.

[8] London Economics (2008): Evaluation of the CAP policy on protected designations of origin (PDO) and protected geographical indications (PGI). Short Summary http://ec.europa.eu/agriculture/eval/reports/pdopgi/short_sum_hu.pdf

[9] Kis Krisztián - Pesti Kitti: Szegedi élelmiszeripari hungarikumok helyzete, lehetőségei a globalizáció és a lokalizáció kölcsönhatásában: eredet, hagyomány és minőség szögediesen [The situation and possibilities of the food industry Hungaricums in Szeged in the interaction of globalization and localization: origin, tradition and quality "the Szöged way."]. Jelenkori társadalmi és gazdasági folyamatok, (2015) vol. X., issue 2., 9-34. 17. http://bit.ly/2ZvJ6vV

[10] Szabó Ágnes: Hungarikumok, avagy a mezőgazdasági termékek és az élelmiszerek oltalmának lehetőségei. [Hungaricums, or the possibilities of protecting agricultural products and foodstuffs.] In: Stipta, István (ed.): Studia iurisprudentiae doctorandorum Miskolciensium, Miskolci Doktoranduszok Jogtudományi Tanulmányai [Legal Studies of Doctoral Students in Miskolc], Tomus 11, Miskolc, 2012. 331-344. 339-340.

[11] 2009. évi XXVII. törvény egyes iparjogvédelmi törvények módosításáról. [Act XXVII of 2009 on the Amendment of Certain Industrial Property Acts.]

[12] European Commission: EU Quality Schemes. 22.08.2019. https://bit.ly/2HZwc59

[13] Panyor Ágota: A védett eredet-megjelölésű és védett földrajzi jelzésű élelmiszerek jelentősége a versenyképesség szempontjából [The importance of foods with protected designations of origin and protected geographical indications for competitiveness]. In: Agriculture and the Vision of the Countryside. Scientific conference, Mosonmagyaróvár, April 17, 2009. Conference proceedings, Tome I. 58-64. 60. http://real.mtak.hu/78848/1/Mezogazdasag_es_a_videk_jovokepe_2009_aprilis_17_18_konferenciakiadvany_I.kotet_u.pdf

[14] Boros 2015, 108.

[15] Millisits Endre: Porto/Port kontra Charlotte,

- 145/146 -

avagy végső döntés előtt az Európai Bíróság a földrajzi árujelzők és az európai uniós védjegyek közötti néhány konfliktus kérdésében. [Porto/Port v. Charlotte, or the European Court of Justice before final ruling on some conflicts between geographical indications and EU trade marks.] Iparjogvédelmi és Szerzői Jogi Szemle, vol. 12. (122.) no. 5., October 2017. 47-58. 48.

[16] Pusztahelyi Réka (2016): Regionális védjegyek a tájegység arculatában: a jogi oltalom előnyei és hátrányai. [Regional trademarks in the image of the region: advantages and disadvantages of legal protection.] In: Karlovitz, János Tibor (ed.): Társadalom, kulturális háttér, gazdaság [Society, cultural background, economy]. International Research Institute s.r.o., Komárno. 9-16. 10-11.

[17] Goebel Burkhart - Groeschl Manuela (2014): The Long Road to Resolving Conflicts between Trademarks and Geographical Indications. The Trademark Reporter, 104 (4). 829866. 831.

[18] Pusztahelyi 2016, 11.

[19] Port Kenneth L. (2015): Regionally Based Collective Trademark System in Japan: Geographical Indicators by a Different Name or a Political Misdirection? Cybaris An Intellectual Property Law Review, 6 (2), 1-61.

[20] "KMÉ"

[21] "AM"

[22] Kis Judit: Új nemzeti védjegyrendszer indul - Itt a Kiváló Minőségű Élelmiszer. [A new national trademark system has started - Here is Excellent Quality Food.] 2019. 06. 13. https://magyarmezogazdasag.hu/2019/06/13/uj-nemzeti-vedjegyrendszer-indul-itt-kivalo-minosegu-elelmiszer

[23] Popovics Anett: A földrajzi helyhez kapcsolódó és a hagyományos magyar termékek lehetséges szerepe az élelmiszerfogyasztói magatartásban. [The possible role of geographical and traditional Hungarian products in food consumer behaviour.] Doctoral dissertation, Szent István University, Gödöllő, 2009.

[24] Szakály Z. - Palloné K. I. - Nábrádi A.: Marketing a hagyományos és tájjellegű élelmiszerek piacán. [Marketing on the market of traditional and regional foods.] Kaposvár: University of Kaposvár, Faculty of Economics. 2010.

[25] Miklós Ilona: A vásárlói értékek és a gyenge elköteleződések az élelmiszerpiacon. [Consumer values and weak commitment on the food market.] Táplálkozásmarketing Vol. VI. 2019/1. 25-39. 26. http://bit.ly/2zpG2GX

[26] Storeinsider.hu: A védjegyek fogyasztói megítélése Magyarországon. [Consumer perception of trademarks in Hungary.] 2017.06.23. http://storeinsider.hu/cikk/a_vedjegyek_fogyasztoi_megitelesemagyarorszagon

[27] Storeinsider.hu: A védjegyek fogyasztói megítélése Magyarországon. 2017.06.23. http://storeinsider.hu/cikk/a_vedjegyek_fogyasztoi_megitelese_magyarorszagon

[28] Storeinsider.hu: A védjegyek fogyasztói megítélése Magyarországon. 2017.06.23. http://storeinsider.hu/cikk/a_vedjegyek_fogyasztoi_megitelese_magyarorszagon

[29] Török Áron: Hungarikumok - Magyarország földrajzi árujelzői. Az eredetvédelem szerepe a XXI. századi mezőgazdaságban és élelmiszertermelésben -a pálinka példájának tanulságai. [Hungaricums - geographical indications of Hungary. The role of origin protection in 21st century agriculture and food production - lessons from the example of pálinka.] Doctoral (PhD) dissertation. BCE GDI, Budapest, 2013.

[30] Palloné Kisérdi I. (2003): A versenyképesség biztosításának új minőségi dimenziója az élelmiszergazdaságban EU csatlakozásunk szempontjából. [A new qualitative dimension of ensuring competitiveness in the food economy from the point of view of our accession to the EU.] Doctoral (PhD) dissertation. BKAE, Budapest, 2003.

[31] Kis - Pesti 2015, 17-18.

[32] Nótári M. - Hajdú L.-né (2005): Marketing elemzések a kertészeti hungarikumok piacának fellendítésére a Dél-Alföld régióban. [Marketing analyses to boost the market of horticultural Hungaricums in the Southern Great Plain region.] Acta Agraria Kaposváriensis, 9(1), 1-9.

Lábjegyzetek:

[1] The Author is doctoral student, Doctoral School of the Law, University of Pécs.