Krisztina Karsai[1]: External Effects of the European Public Prosecutor's Office Regime (MJSZ, 2019., 2. Különszám, 2/1. szám, 461-470. o.)

1. Introduction

On 12 October 2017, a groundbreaking new regulation establishing the European Public Prosecutor's Office (EPPO) was adopted by twenty-two Member States (MS) of the European Union.[1] Those MS are now part of a so-called enhanced cooperation (EPPO-EnC[2]) which targets the establishment of a new and genuine legal and judicial joint framework against crimes affecting the financial interests of the Union recognizing that it can be better achieved at Union level by reason of its scale and effects. The present situation, in which the criminal prosecution of offences against the Union's financial interests is exclusively in the hands of the authorities of the MS of the EU, does not always sufficiently achieve that objective. The framework of this joint efforts provides for a system of shared

- 461/462 -

competence between the EPPO and national authorities in combating crimes affecting the financial interests of the Union, based on the right of evocation of the EPPO. The EPPO will be granted powers of criminal investigation and prosecution, it will be an independent and accountable institution of the Union. EPPO will act in the interest of the Union as a whole. The TFEU provides[3] that the material scope of competence of the EPPO is limited to criminal offences affecting the financial interests of the Union. The offences against the financial interests of the EU are laid down in the directive on the fight against fraud to the Union's financial interests by means of criminal law,[4] which defines the relevant offences (fraud, corruption, money laundering, misappropriation and other related offences) and provides minimum-ruling and calls for implementation in the MS. These offences fall within the direct material scope of competence of the EPPO, meanwhile, the EPPO-Reg contains rules on supplementary material scope of competence of the EPPO as well: the EPPO investigates, prosecutes and brings to judgment the perpetrators of any other offences so far as they are inextricably linked to the offences against the financial interests of the EU.

There are some MS remained which are not participating in the enhanced cooperation.[5] However, I think non-participating MS can be affected heavily by enhanced cooperation in this field especially due to the 'coercive power' of legal integration in connection with the nature of the related offences as being transnational. This will make joining the enhanced cooperation on EPPO also for them necessary.

2. Enhanced Cooperation and its External Effects

Enhanced cooperation[6] is a procedure under which a minimum of 9 EU countries are allowed to establish advanced integration or cooperation in an area within EU structures, but without the involvement of the other EU countries. Other EU countries maintain their right to join when they wish to do so. This enables them to move at a different pace and towards different goals than those outside of the enhanced cooperation areas. The procedure is designed to overcome paralysis,

- 462/463 -

where a proposal is blocked by an individual country or a small group of countries who do not wish to be part of the initiative. It does not, however, allow for an extension of powers outside of those permitted by the EU Treaties. The possibility was first introduced by the 1999 Amsterdam Treaty ('closer cooperation'), with the 2009 Lisbon Treaty formalizing the procedure and extending the possibility for enhanced cooperation to include defence.[7]

This procedure was being applied in the fields of divorce law, and patents (European Unitary Patent), and is approved for the European Public Prosecutor Office, and is presently under negotiations or at final stage of approval for use in the field of a financial transaction tax and of property regime rules (of international couples). As several initiatives of enhanced cooperation have already been approved, which demonstrates huge potential

"in a period of disillusion with European integration (...). Therefore, the question is no longer whether or not the rules on enhanced cooperation are useful. Rather, it remains to be properly assessed how far forward they will push European asymmetry, whether more asymmetry is desirable and what level of asymmetry is sustainable."[8]

Enhanced cooperation provides an opportunity for a certain group of member states to deepen integration along EU objectives even if not each and every member state wishes to realize the given aim under the given stage of integration - neither legal solutions outside of the EU legal framework nor restricting the discretion to speed up can be viable options. Obviously, with this, the reality of the multispeed Europe has disrobed the negative connotations materializing in analyses and political declarations, as the establishment of enhanced cooperation legal opportunity is what justifies the varying levels of inclination for integration and provides a formal, legally supported framework.

Article 327 TFEU declares that any enhanced cooperation shall respect the competences, rights and obligations of those MS that do not participate in it, but also underlines that the non-participating MS shall not impede its implementation by the participating Member States. Under TFEU, the new rules on enhanced cooperation provide a 'no veto' regulatory scheme, which also means that the non-participating MS no longer (before the Nizza Treaty that was the case) have the power to block an initiative and may join the enhanced cooperation at any time. However, the MS can only join if it has fulfilled the conditions for participation and adopts any transitional measures necessary with regard to the application of the acts already adopted within the framework of enhanced cooperation (Article 331 TFEU). This also means that it is the non-participating member state's primary interest to monitor the operation of the enhanced cooperation that was created without [the member state] and logically, to make sure that its lack of participation

- 463/464 -

does not adversely affect its interests. Although the TFEU sets forth that enhanced cooperation considers the interests of the non-participants as well, in the event of a conflict, the integrity of the interests of the non-participating MS shall be surpassed by the general EU integration interests and rules, of course.

The CJEU stated in its judgement C-274/11 (16. April 2013) in relation with the unitary patent enhanced cooperation that

"it is essential for enhanced cooperation not to lead to the adoption of measures that might prevent the non-participating Member States from exercising therr competences and rights or shouldering their obligations, it is, in contrast, permissible for those taking part in this cooperation to prescribe rules with which those non-participating States would not agree if they did take part in it. Indeed, the prescription of such rules does not render ineffective the opportunity for non-participating Member States of joining in the enhanced cooperation. As provided by the first paragraph of Article 328(1) TFEU, participation is subject to the condition of compliance with the acts already adopted by those Member States that have taken part in that cooperation since it began."[9]

Therefore, in connection with the establishment of EPPO, one of the most important questions to be addressed is handling changes affecting non-participating MS, as the insignificance of territorial boundaries is especially distinct in this area: in particular, it had been the efforts to combat transnational- and cross-border crime that had brought the area based on freedom security, and justice to life in the first place (obviously, starting based on its history), and that the joint efforts of the MS would provide sufficient and effective solutions to modern forms of crime. The result of the joint efforts was that criminal prosecution and criminal justice operating under the national framework has opened, and many such achievements have come to life that have raised the national instruments of the judiciary for exercising power to a supranational European- or cooperative level between MS. But by comparison, the EPPO enhanced cooperation will actually reinstate geographic restrictions - in my opinion, without much luck however, and following its commencement, the EPPO enhanced cooperation will give rise to effects concerning criminal justice within non-participating MS that could dislodge provisions of Article 327.

Whereas EPPO follows the European territoriality principle within the MS of the enhanced cooperation, the same regime would reactivate 'state borders' in its cooperation with non-participating MS inflating the achievements in area of freedom, security and justice. I believe that the external effects of this so-called enhanced cooperation will be significant, necessary, and inevitable - and the conflicts emerging because of these will presumably only be solvable if all MS enter the EPPO system.

- 464/465 -

3. Mutual recognition rules the discrepancies of implementation

Due to the directive containing the concerned offences, the substantive criminal law protection of MS will be uneven after implementing procedures, and there will certainly be unique constellations deriving from different legal systems of the MS and the minimum regulatory method of the directive, that will generate basic differences concerning specific questions, among the most important being punishability and impunity. Some examples:

- the rules on the period of limitation (limitation of liability by the lapse of time) of certain MS set the minimum time limits to a later period, while others set a different but earlier maximum time limit for punishability;

- different interpretation of accessory character of the participation could result in different judgment of the same aiding or abetting conduct;

- as a result of the fundamentally different dogmatic approaches related to the stages of perpetration, the same act could be considered punishable attempt in one MS or perhaps preparation in another depending on the acceptance of an objective or a subjective theory;

- the concrete conditions for sanctionability of legal persons can be fundamentally different (is the establishment of a crime by a natural person necessary; what causal relationships must be examined, etc.).

Such regulatory asymmetries are inevitable in this co-working system of European law and national criminal law, and only systematic research can provide real prognose in this regard.[10] However, the main fundamental problem can be identified nonetheless, and it is that the limits (or scope) of punishability for the given offences do not overlap entirely in the different MS, thus the scope of competence on the side of the EPPO will show discrepancies in the different MS because only the MS 'jurisdiction' on offences turns the competence of EPPO into reality.

It is important to note that disparities in the limits of punishability/non-punishability in the different MS is not new for the area of freedom, security and justice (and for ECL). Actually, the principle of mutual recognition[11] is the tool dedicated to overcome these differences if necessary. Moreover, there are some supporting instruments availing the compensation of differences in the scope of punishability by approaching mutual recognition: meanwhile in the system of the European arrest warrant, a certain automatism serves for rounding off the differences, the principle of assimilation will apply in the regime of European investigation order. Mutual recognition plays a role also in the system of EPPO (Article 31) but not as it regards the competence rules. The implementation of a directive according to a national criminal law system does not provide automatic compliance with all other MS criminal law, the risk of a 'relative gap of punishability' (= not fully overlapping prohibitions by criminal law) cannot be

- 465/466 -

eliminated by mutual recognition. That is the trap in this regime. A more focused legal unification could provide a rescue route if the political consensus is given in this regard. The activist jurisprudence of the CJEU cannot be an option thereto because the key issue here is gap of punishability or - from the opposite point of view - acceptance of non-punishability. And case law in criminal matters itself cannot fill gaps of punishability, it cannot extend or establish criminal responsibility if the (written) law does not provide a solid basis for it. However, if we accept that EU has been granted partial ius puniendi by the MS regarding the protection of the financial interests the CJEU will have the entitlement to apply more activism in this regard as well.

4. Scope of application

According to Article 23 the EPPO shall be competent for the offences referred to in Article 22 where such offences: (a) were committed in whole or in part within the territory of one or several Member States; (b) were committed by a national of a Member State, provided that a Member State has jurisdiction for such offences when committed outside its territory, or (c) were committed outside the territories referred to in point (a) by a person who was subject to the Staff Regulations or to the Conditions of Employment,[12] at the time of the offence, provided that a Member State has jurisdiction for such offences when committed outside its territory.

The crimes that the EPPO will have an important role in stepping up against are often such that due to their transnational character could be committed within the territory of non-participating MS. In the case of carousel fraud or other types of VAT fraud acts, for example, that can be committed in the territory of a non-participating MS and are inextricably linked to similar activities perpetrated in other MS that are EPPO participants, the following scenarios could be conceivable.

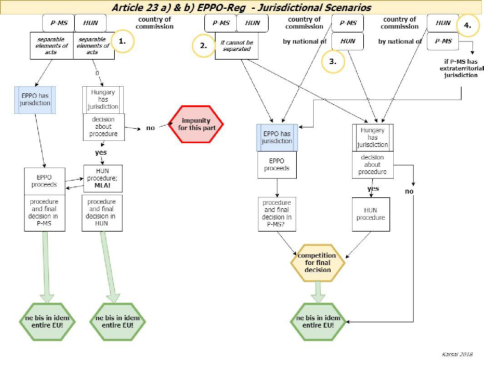

Applying Article 23 section a) and b) there are the following initial scenarios:

- the offence has been committed in at least two participating MS - this is the normal case of EPPO, it is a full acceptance of the principle of European territoriality.

- the offence has been committed in at least two MS (one of them is a non-participating country; 1. and 2.) or

- the offence has been committed in a participating MS but by a citizen of a non-participating MS (3.) or

- the offence has been committed in a non-participating MS but by a citizen of a participating MS (4.).

It does not fall under the scope of application of the regulation, if the offence has been committed only on the territory of non-participating MS by their citizens.

- 466/467 -

The second case has two further alternatives (1. and 2. in the graph) according to the factual circumstance whether the offence has separable acts committed on the territory of a non-participating MS.

If its separable: EPPO does not deal with the cases committed in non-participating MS but signals the possible need for a procedure to national law enforcement authorities. The domestic authorities will decide whether to proceed, however the background directive requires the prosecution, thus a decision not to prosecute would constitute a violation of the union law. (1.)

The EPPO is dealing with an offence which (or at least part of it) has been perpetrated in a non-participating MS, and the case cannot be separated, the inextricable connection is given. In this case the procedure of the EPPO - in the case of a final decision having been reached, will result in res judicata and the ne bis in idem doctrine[13] will come into force. The negative effect of this will be that the ne bis in idem doctrine will also enter into force for the parts of the crime committed in the non-participating MS but without participation of this country in the adjudication process. The ne bis in idem principle shall prevail even if another MS criminal proceeding had been initiated in parallel, and further, if this procedure

- 467/468 -

was to be closed following substantive examination prior to the procedure initiated by EPPO, the res judicata power of the former would make the judgment of EPPO redundant. The EPPO ss dealing with an offence that (or at least part of it) had been perpetrated in a non-participating MS, and the case can be separated. In such a case, the competent authorities of this MS shall have a procedural obligation (principle of procedural legality) from the point knowledge is gained of the possible commission of the offence - at the latest after the EPPO informed the competent authorities. Unquestionably, it can be noted that on one hand, the above scenarios may give rise to abuse of the system, while on the other hand, these may result in the non-punishment of offences committed in the territory of non-participating MS. (2.)

It may also happen that an act is committed by a national of the non-participating MS abroad, that is, in the territory of a MS that has joined the enhanced cooperation scheme. If that MS acknowledges the active personal principle (which is generally dominant in any European country), its jurisdiction will be extended to the offence, but this will conflict with the jurisdiction of EPPO. In this case, as well as in the scope of the former cases, application of the coordination mechanism can be recommended, which in its current status covers conflicts of jurisdiction between MS but could logically be applicable in MS-EPPO relations as well.[14] (3.)

The rules applied for acts committed in the territory of non-participating MS are based on the extraterritorial jurisdictoon of the EPPO. In this scenario, Article 23 no. b) of the EPPO-Reg could be applied, such as a situation where under criminal law of the participating MS the active personal principle would prevail without limitation - in other words, the MS enforces claims for punishment for a criminal act committed elsewhere by its national. In such a case, the criminal jurisdiction of non-participating MS could exist for an act committed in its territory, but in this case the EPPO may also maintain the right of exercising competence. A criminal procedure carried out in parallel could also have consequences such as those outlined in the former point. If authorities of non-participating MS do not carry out a procedure, the principle of non-territorial jurisdiction acknowledged by EPPO-Reg would again precipitate that the EPPO may prosecute an act committed in the territory of this MS. (4.)

In summary it can be concluded that between the non-participating MS and the EPPO, both negative and positive jurisdictional conflicts will arise and in essence, settling these without infringing upon the rule of law principles is at most possible only if we sacrifice the effective prosecution of transnational crimes that violate EU financial interests. This is not among the possible options even for non-participating MS, since the provision under Article 328 of the TFEU already sets this forth as a fundamental obligation for all MS.

- 468/469 -

5. Ne bis in idem

The acknowledgement and the enforcement of the transnational validity of the classic ne bis in idem principle with the tools of European law is one of the most important material achievements of European criminal law. The enforcement of the principle bears a significant risk not only for EPPO, but as already mentioned, for the non-participating MS as well. When both EPPO and the non-participating MS have competence over the act, or a part of it - due to any provision giving ground to competence - it may result in starting a 'competition' or a 'race' for the blocking effect by delivering a final decision that can have a negative impact on the well-foundedness of the decision-making.

As a further risk, in the cases specified by the law of non-participating MS, the criminal procedure can also be carried out against an accused person who committed the relevant offence but is absent during the procedure (for instance in Hungary this is the case). It may easily result, on the basis of the personal principle, in allowing the non-participating MS to proceed as a general rule, and it shall indeed proceed, although on the basis of the principle of territoriality the offence has been committed in a state that handed over the procedure to EPPO, which is therefore also competent to proceed. Due to the principle of ne bis in idem, EPPO would only terminate the procedure if there was a final national decision, however, in such a case, the binding force upon EPPO of an in-absentia decision would still be questionable. In this case, the authorities of non-participating MS would not be bound to terminate the procedure, nevertheless the criminal procedure could possibly be transferred to the MS having jurisdiction according to the place of committing the offence. This would naturally imply accepting that the transferred criminal procedure shall be completed by EPPO.

6. Safe-havens and forum shopping?

Any system allowing the opting out of certain geographic territories from the unified territorial competence and allowing for independent decisions to be passed in a proceeding with the case by authorities independent from each other, creates a fundamental 'hotbed' of forum shopping resulting from the collision of jurisdictions: it applies both for the prosecutors of crime and the criminals. In addition, there can be another layer that can further aggravate such a situation: when there are also political reasons behind opting out of EPPO.

The phenomenon of forum shopping is usually referred to in the context of the 'conscious' conduct of criminals: accordingly, more qualified criminal offenders may assess the differences between the provisions of criminal or procedural law when they decide on where to commit the offence. They may in particular orient themselves along the existence of criminal liability (i.e. whether or not the given act is a criminal offence), the gravity of the punishments, the rules on confiscation of property (e.g. the reversing of the burden of proof), or according to special procedural rules, and the existence or the lack of cooperation in extradition may

- 469/470 -

also be a relevant factor with regard to countries outside Europe. We may assume that - if the offender has an option to decide or to make an influence - he shall choose the country where he may expect a less severe adjudication or an extended (extendable) procedure, should his act still be discovered.

The factors that formulate forum shopping by prosecutors of crime are factually present in traditional interstate cooperation and they serve as concealed or open currency for political compromises and deals or as reciprocities between states that serve other interests. Between the European states, these manoeuvres have already lost their political charge, but concurrently they take force in a concealed (informal) way as they nonetheless exist as a consequence of the most important achievement of the integration of criminal law in the EU. The transnational acknowledgement of the ne bis in idem principle, the obligation of coordinating (at least in the beginning) parallel criminal procedures, the supranational EU legal basis established for resolving conflicts of jurisdiction all result - in the case of certain concrete criminal offences affecting several MS -, in putting the states with jurisdiction into a situation of being able to assess and make a decision binding upon all MS in the question of which state shall proceed finally with the case. Here the difference in the intensity of the evidence available in the different states can be a fundamental aspect, but the decision-making matrix shall also include the level of threat by punishment, the type of the sanctions and clearly the comparison of the procedural rules as well (possibility of pre-trial detention, option to use secret or concealed tools etc.). It is evident that the humanist principles of the criminal system based on force by the state would not allow choosing a proceeding state because it offers the most severe sanctions or as the causes excluding criminal liability are narrower there, or indeed because the requirement of the level of probability needed for passing an assured judgement as followed in the procedure of taking evidence is lower than in other states.

In this context, in any case where EPPO would otherwise proceed (in a participating country) there is a concrete and constitutive decision to be made by the non-participating MS: it may decide not to proceed or to proceed just in order to be able to enforce its 'own' decision as soon as possible, and with that, the legal force of the ne bis in idem principle - it may result in impunity, with a transnational enforceability all over Europe. If such a decision would have also been backed by political motivations aimed at locally concealing acts (suspected to be) offending the EU's financial interests, the 'safe-haven' nature of the Member State's decision would clearly violate the general interests of the Union.[15] ■

NOTES

[1] The road to this legislative act has been started in the 1990s, about the development see the works of the jubilee. Farkas Ákos: Az EU büntetőjogi korlátai. Ügyészségi Szemle, 2018/2. 74-96.; See in particular Weyemberg, Ann - Briere, Chloé: Towards a European Public Prosecutor's Office (2016. European Parliament, Policy Department for Citizen's Rights and Constitutional Affairs) 1-64.; Láris, Liliána: Reasons of the Establishment of the European Public Prosecutor's Office. Iustum Aequum Salutare, 13/2017. 219-234.; Bachmeier, Lorena (ed): The European Public Prosecutor's Office. Springer, 2018.; Geelhoed, Willem - Erkelens, Leendert - Med, Arjen (eds): Shifting Perspectives on the European Public Prosecutor's Office. Springer, 2018. For basics on EPPO see Ligeti, Katalin: The European Public Prosecutor's Office: How Should the Rules Applicable to its Procedure be Determined. EuCLR 2/2011, 123-148.; Ligeti, Katalin (ed): Toward a Prosecutor for the European Union. Volume 1. Hart Publishing, 2012.; Spencer, John R.: Who is afraid of the big, bad European Public Prosecutor? Cambridge Yearbook of European Legal Studies, 14/2012. 363-380.; Wade, Marianne: A European public prosecutor: potential and pitfalls. Crime, Law and Social Change 59/2013. 439-486.; Csúri, András: The Proposed European Public Prosecutor's Office - from a Trojan Horse to a White Elephant? Cambridge Yearbook of European Legal Studies, 18/2016. 122-151.; Trentman, Christian: Eurojust und Europäische Staatsanwaltschaft - Auf dem richtigen Weg? Zeitschrift für die gesamte Strafrechtswissenschaft, 129/2017. 108-145.

[2] O.J. 2017, L 283, Council regulation 2017/1939 of 12 October 2017 implementing enhanced cooperation on the establishment of the European Public Prosecutor's Office ('the EPPO')

[3] The Lisbon Treaty amended the original treaties, and the Treaty on the European Community was transformed into the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU). TFEU Article 86 Section 2 "The European Public Prosecutor's Office shall be responsible for investigating, prosecuting and bringing to judgment, where appropriate in liaison with Europol, the perpetrators of, and accomplices in, offences against the Union's financial interests, as determined by the regulation provided for in paragraph 1. It shall exercise the functions of prosecutor in the competent courts of the Member States in relation to such offences"

[4] O.J. 2017, L 198, Directive (EU) 2017/1371 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 5 July 2017 on the fight against fraud to the Union's financial interests by means of criminal law.

[5] Denmark, Sweden, Poland, Spain, Hungary and the UK.

[6] Kroll, Daniela - Leuffen, Dirk: Enhanced cooperation in practice. An analysis of differentiated integration in EU secondary law. Journal of European Public Policy, 22/2015. 353.; Cantore, Carlo Maria: We're one, but we're not the same: Enhanced Cooperation and the Tension between Unity and Asymmetry in the EU. Perspectives on Federalism, 3/2011. 1-21.

[7] The adoption of the decision authorising enhanced cooperation requires a qualified majority of Member States within the Council and the consent of the European Parliament. The adoption of the new rules then requires unanimity by the Member States participating in enhanced cooperation and the consultation of the European Parliament. The other Member States are free to join the enhanced cooperation at any time.

[8] Cantore: i.m. 14.

[9] Joined cases C-274/11 and C-295/11; Spain and Italy against the Council, EU:C:2013:240.

[10] Ligeti: i.m.

[11] See basics and summary in Farkas Ákos: Az Európai Bíróság és a kölcsönös elismerés elvének hatása az európai büntetőjog fejlődésére. Miskolci Jogi Szemle, 2011/6. 62-77.

[12] O.J. 2013, L 287, Regulation (EU, EURATOM) No 1023/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 October 2013 amending the Staff Regulations of Officials of the European Union and the Conditions of Employment of Other Servants of the European Union.

[13] Karsai Krisztina: Transnational ne bis in idem principle in the Hungarian Fundamental Law. In: Spinellis C. D. and others (eds): Europe in Crisis: Crime, Criminal Justice, and the Way Forward: Essays in Honour of Nestor Courakis. Sakkoulas Publications, Athens, 2017. 409.

[14] O.J. 2009, L 328/42, Council framework decision 2009/948/JHA of 30 November 2009 on prevention and settlement of conflicts of exercise of jurisdiction in criminal proceedings.

[15] This research was supported by the project Nr. EFOP-3.6.2-16-2017-00007 (European Union, co-financed by the European Social Fund and the budget of Hungary).

Lábjegyzetek:

[1] A szerző Intézetvezető egyetemi tanár, Szegedi Tudományegyetem, Állam- és Jogtudományi Kar, Bűnügyi Tudományok Intézete [Full professor, Head of Unit; University of Szeged, Institute of Criminal Law and Criminal Science; Jean Monnet Chair].