Peter Csonka[1]: Homage to Professor Farkas Ákos The European Union's criminal justice area: what's next? (MJSZ, 2019., 2. Különszám, 2/1. szám, 199-205. o.)

1. Introduction - achievements

Professor Farkas has a long-standing interest in the Union's criminal law and policy matters, on which he reflected and published extensively, both before and after Hungary had joined the European Union in 2004[1]. He has inspired young colleagues, like me, and generations of law students to study this special branch of law, called back then as "community law", which is neither national nor international[2] but which has gradually become the dominant source of law for Union's Member States. While criminal law remained, essentially, a national competence[3], the Union has gradually expanded its influence in this area.

The Union's criminal law - both substantive and procedural - is now a key component of the European Union's policies, which also seek to provide citizens with a high level of security and rights by establishing an area of freedom, security and justice and by ensuring coordination and cooperation between police and judicial authorities, mutual recognition of judgments in criminal matters, as well as approximation of criminal laws. Since 2014, this area has fully entered the "ordinary" EU legal framework, whereas previously intergovernmental methods were still largely in use given the sensitivity of the subject matter.

A lot of progress has been achieved over the last twenty years, i.e. since the 1999 Tampere Programme. There is a large Union acquis on cooperation between judicial authorities, such as the European Arrest Warrant or the European Investigation Order, along with the recognition of other judicial decisions between

- 199/200 -

Member States (such as supervision orders pending trial, or the execution of prison sentences or financial penalties) and the progressive harmonisation of certain aspects of national substantive criminal and procedural laws, including through the adoption of minimum standards to protect the rights of suspects and victims, while remembering that it remains an important challenge to ensure the effective implementation of these legal instruments in all Member States.

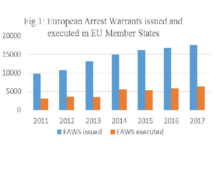

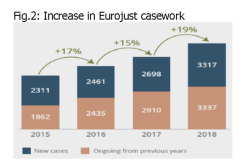

EU's efforts to establish a common area of justice are visible both in the progress of judicial cooperation, as well as in how it protects the rights of people involved in justice-related issues, including those of victims and suspects. Fig.1 shows the increase in the number of European arrest warrants issued/executed[4] and Fig.2 the increase in the number of cases referred to and handled by Eurojust. These are good illustrations of how the Union's instruments or agencies for judicial cooperation help national authorities to fight cross-border crime.

2. The challenges

As the world around us becomes more fractured and unsettled, our core task is to protect and further Europe's achievements, including its open democratic societies and liberal economies, while keeping terrorism and cross-border organised crime effectively under control.

Judging by the relevant indicators it is clear that the terrorist threat in the Union remains high and new attempts to carry out attacks are highly likely. While the number of fatalities has decreased since 2015 (from 151 to 62 in 2017), the number of jihadist-inspired attacks (33) in 2017 more than doubled the figure of 2016 and the number of arrest in relation to jihadist terrorist activities remains high (705). Right-wing terrorism is assessed to be generally under-reported in the EU, yet the threat is assessed to increase and the number of arrests (20) almost doubled in 2017.

Similarly, organised crime remains a challenge for authorities: Europol's current Serious and Organised Crime Threat Assessment (SOCTA), published in 2017,

- 200/201 -

indicates more than 5,000 organised crime groups (OCGs) operating on an international level and currently under investigation in the EU. The increased number in comparison to previous years points to the emergence of smaller criminal networks, especially in criminal markets that are highly dependent on the internet as part of their modi operandi or business model. Overall, the number of organised crime groups operating internationally highlights the substantial scope and potential impact of serious and organised crime on the EU. More than one third of the organised crime groups active in the EU are involved in the production, trafficking or distribution of drugs. Other key criminal activities for organised crime groups in the EU include organised property crime, migrant smuggling, trafficking in human beings and excise fraud. 45% of the organised crime groups reported for the 2017 Assessment are involved in more than one criminal activity. The share of these "polycriminal" groups increased sharply compared to 2013. Organised crime groups operating on an international level are typically active in more than three countries (70%). A limited number of groups are active in more than seven countries (10%).

A study of the European Parliament[5] pointed to an economic loss due to organised crime and corruption in terms of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) of between EUR 218 and 282 billion € annually. That study also builds on existing estimates of the size of illicit markets representing a value of around EUR 110 billion and points to the significant social and political costs of organised crime and corruption, such as the infiltration of the legal economy by organised crime groups. Furthermore, a 2015 study on Transnational Crime[6] concluded the assets of criminal groups are increasingly invested in other Member States.

3. The Union's future response

In the face of such adversity the Union should aim to preserve the European way of life, defend our common values and advocate multi-lateral institutions and global regulatory standards. Fairness and sustainability should remain guiding political values.

Among the key priorities in the area of justice the Union should seek to strengthen mutual trust based on democracy, the rule of law and fundamental rights, increase fairness and sustainability in society and the smooth functioning of the single market and strengthening enforcement.

In the area of justice and home affairs, the Union should tackle two main challenges:

- Prevention of the causes of crime: including an action plan on crime prevention both online and offline, hate speech, violence against women, other societal causes leading to crime, over-crowding and radicalisation in prisons.

- 201/202 -

- Developing the criminal justice area: including the capability and scope of the European Public Prosecutor's Office, making corruption an EU crime, international agreements on electronic evidence.

3.1. Crime prevention. Crime prevention is widely understood as any positive action by governments and private sector to reduce and deter crime and criminals. Enforcing the law and maintaining criminal justice are key elements of crime prevention. However, preventing crime is also a larger societal issue and social responsibility whereby the causes of crime, such as poverty exclusion and violence, are reduced so that offending behaviour and thus criminal enforcement can be avoided. The objective is to address the causes of crime before it takes place, so that less resources are spent on dealing with the impact of crime after it has taken place.

In the justice area, while crime prevention is, as a rule, within the competence of Member States[7], the Union may establish measures to promote and support the action of Member States in this field. Thus far the Union has contributed to preventing crime essentially in two areas, i.e. establishing preventive measures in specific areas such as money laundering and terrorist financing[8] and reducing re-offending or facilitating rehabilitation through criminal justice measures, such as supporting the use of alternatives to imprisonment.

One of the factors which can prevent crime is a proper investment in rehabilitation or social reintegration of (ex) offenders. There are reasons to believe that the chances of social reintegration of (ex) offenders can be improved by common action at EU level. In 2008 and 2009, the Council adopted a package of three framework decisions with this aim, namely the Framework Decision on Transfer of Prisoners, the Framework Decision on Probation and Alternative Sanctions and the Framework Decision on the European Supervision Order.

Overcrowding of prisons and poor detention conditions reduce the possibilities for rehabilitation and social reintegration. Over recent years a growing number of Member States have been condemned by the European Court of Human Rights via so-called pilot judgments for overcrowding and poor detention conditions. Nine EU Member States have a prison occupancy rate of more than 100%. In some Member States, the proportion of pre-trial detainees amounts to more than 40% of the prison population (compared to the EU average of 21%). Poor prison conditions also enhance the risk of radicalisation leading to violent extremism. The use of alternative (non-custodial) sentences can help to resolve the structural problem of overcrowding.

While the problems of racism, xenophobia, discrimination and intolerance are not new, over recent years hatred and violent threats have become normalised, in particular as a response to the challenges posed by events such as the refugee crisis and the backlash to tolerance in the aftermath of devastating terrorist

- 202/203 -

attacks. Taking firm action to counter and prevent hate crime and hate speech is crucial to upholding the Union's values which requires fostering a society where pluralism, tolerance and non-discrimination prevail.

Crime can also be prevented by increasing the likelihood of getting caught and successful prosecution, and ensuring that appropriate sanctions are applied. These are policy areas where the Union is active through its agencies (Europol, Eurojust, European Public Prosecutor's Office - EPPO) and through its material criminal law initiatives, including harmonised sanctions for serious forms of crime.

3.2. Developing further the criminal justice area. EU Criminal Law (both substantive and procedural) has been a key component of the EU policies for the last 20 years. In the area of freedom, security and justice the EU provides citizens security and rights, in particular it ensures coordination between judicial authorities, mutual recognition of judgments in criminal matters, and approximation of criminal laws.

There is a large acquis on cooperation between judicial authorities (e.g. via Eurojust), on the recognition of judicial decisions from other Member States (MS) (e.g. the European Arrest Warrant) and approximation of substantive and procedural criminal laws, e.g. in the area of rights of suspects and accused persons or victims of crime. It is important to continue to ensure the effective implementation of these existing legal instruments.

With the evolution of crime, globalisation and technological innovations, there are continuous calls for changes and new initiatives to adapt the Union's acquis to actual needs of practitioners and citizens and to give appropriate responses to new developments, including those linked to digitalisation and the use of Artificial Intelligence (AI).

A key challenge is to establish a solid EU criminal law framework, coherently tackling serious and/or cross-border crimes (so called "euro-crimes") and other crime areas where the approximation of offences or sanctions is essential for enforcing EU law (so called "accessory crimes"), in full respect of Member States' legal traditions. It is important to strike the right balance between EU action and the respect for Member State's legal traditions, in particular in the area of sanctions.

Further efforts are required to facilitate mutual recognition of judgments and judicial decisions in criminal matters, including by ensuring minimum harmonisation of criminal procedural rules. The issue is the growing lack of mutual trust due to poor prison conditions in some Member States.

A further challenge is to set up and ensure there is a robust EU institutional framework for facilitating cross-border cooperation in this area via Eurojust, the European Judicial Network in criminal matters or other networks (Joint Investigation Teams, European Judicial Network in civil matters and Genocide Networks), or direct criminal enforcement via the European Public Prosecutor's Office (EPPO). The main challenge is ensuring coherence of action and adequate funding.

- 203/204 -

3.3. Open files.

- Legislative files: the e-evidence package is currently the only file under negotiation. The package - proposed by the Commission in April 2018 -consists of a Proposal for a Regulation on European Production and Preservation Orders for e-evidence in criminal matters and a Proposal for a Directive laying down harmonised rules on the appointment of legal representatives for the purpose of gathering evidence in criminal proceedings. A General Approach was reached on the Regulation and Directive respectively at the December 2018 and March 2019 JHA Council meetings. The Parliament did not deliver a position in this parliamentary term. To complement the internal e-evidence proposals, in February 2019 the Commission adopted Recommendations: (1) to open negotiations on an EU-US Agreement on cross-border access to e-evidence and (2) to participate in the negotiations on a Second Additional Protocol to the Council of Europe Convention on Cybercrime. Adoption in Council is foreseen in June 2019.

- Implementation work: there is a considerable acquis in the area of criminal justice, partly based on the Lisbon Treaty. However implementation is often patchy. The first-ever assessment of national implementation of EU criminal law Directives started in 2013. As of 1 December 2014, the Commission has been granted full infringement powers for EU criminal law measures adopted before the Lisbon Treaty's entry into force. In addition, the Commission will work together with Member States to ensure that recently adopted legislative acts are implemented and applied correctly (e.g. European Criminal Records Information System - ECRIS-TCN, anti-money laundering Directive, Regulation on Confiscation). It will also oversee the implementation work of the Eurojust Regulation, to be implemented by the end of 2019. The first version of the e-Evidence Digital Exchange System, supporting electronic communication between competent authorities in the context of the European Investigation Order and the Mutual Legal Assistance conventions, should go live by end 2019.

It is important to ensure the effective implementation of existing legal instruments, e.g. the six Directives on procedural rights, various mutual recognition instruments and the setting up of the EPPO (target date November 2020).

4. New ideas

Besides finalising the open legislative files and ensuring the implementation of the acquis, reflection has also started on possible additional legislative initiatives which could help the Union complete its criminal justice arsenal. The following issues may be mentioned as worth exploring:

- Rules on the transfer of criminal proceedings from one Member State to another, in a broader context of rules on conflicts of jurisdiction and the principle of ne bis in idem;

- 204/205 -

- Rules concerning the cross-border use of evidence, e.g. addressing the use or non-use of evidence in cross-border cases (rules on admissibility or rules on certain evidence types);

- Rules on the protection of vulnerable suspects and accused by introducing binding procedural rules;

- Revision of the Directive on Environmental Crime to ensure a more effective enforcement regime and to introduce the objective of sustainable development;

- Extending the material competence of the EPPO with a 2025 perspective;

- Developing minimum standards on pre-trial detention to strengthen mutual trust;

- Rules on compensation for unlawful detention;

- Continuing work on victims' rights, including more effective access to justice and compensation;

- Enhancing convergence of the current criminal records structures into one single system for identifying Member States which hold conviction information of a person, independent of the nationality;

- Enhancing Eurojust as a judicial cooperation centre for terrorism/organised crime; enhancing the work of the European Judicial Network (EJN) as a 24/7 professional judicial network and ensuring an effective cooperation between the three actors (EPPO, EJN, Eurojust);

- Revising the handbook on the European Arrest Warrant (EAW) to implement the jurisprudence of the Court of Justice and issuing new handbooks such as on transfer of prisoners;

- Reflecting on the use of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in criminal proceedings.

Exploring possible avenues for future work based on existing technical solutions, such as e-CODEX, including developing reference implementations for the digitalisation of EU criminal law procedures - further evolution of the e-Evidence system, digitalisation of procedures such as the EAW, financial penalties, custodial sentences, etc. ■

NOTES

[1] Example: Farkas Ákos: Az Európai Uniós büntetőjog fejlődésének újabb állomásai. In: Farkas Ákos -Nagy Anita - Róth Erika - Sántha Ferenc - Váradi Erika (szerk.): Tanulmányok Dr.Dr.h.c. Horváth Tibor Professor Emeritus 80. születésnapja tiszteletére. Bűnügyi Tudományi Közlemények. 8. Bíbor Kiadó, Miskolc, 2007. 483-508.

[2] Costa v. ENEL /Case 6/64/ in 'The relationship between EC law and national law. The cases' /Ed: A. Oppenheimer/, CUP 1994, Cambridge, 66-67.

[3] "As a general rule, neither criminal law nor the rules of criminal procedure fall within the Community's competence", Case C-176/03,se C-176/03, paragraph 47

[4] Based on data provided by Member States to the Council and Commission.

[5] Organised Crime and Corruption: Cost of Non-Europe Report, 2016

[6] From illegal markets to legitimate businesses: The Portfolio of Organised crime in Europe, 2015, 21.

[7] Article 84 Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union

[8] E.g. Directive (EU) 2015/849 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 20 May 2015 on the prevention of the use of the financial system for the purposes of money laundering or terrorist financing

Lábjegyzetek:

[1] The Author is Head of Unit at the European Commission. The views expressed are personal.