Frank Máté[1]: A (Cost)Efficiency Analysis of Development Risk in EU Law[1] (JÁP, 2024/4., 45-61. o.)

https://doi.org/10.58528/JAP.2024.16-4.45

Abstract

The aim of this study is to provide a detailed analysis of the most controversial exemption rule of the producers' objective liability for damages caused by defective products. Our objective is, on the one hand, to identify the legal and economic policy considerations that led to the creation of the development risk exemption, also known as the state of the art defence. In this perspective, it analyses the legislative process leading up to the Product Liability Directive, which left the decision of the deployment of the development risk exemption to the discretion of Member States as a compromise solution. On the other hand, in this context, the study aims to take a comprehensive overview of the current application of the development risk clause across Member States, while reflecting on the effectiveness of the legal instrument in light of the number of product liability claims in Member States at EU level. This analysis aims to determine whether the liability framework favors or disadvantages injured parties.

Keywords: product liability, development risk, burden of proof

I. Introduction, the Definition of Development Risk

In several cases, the Product Liability Directive[2] allows the producer to be exempted[3] from the strict liability for damages caused by defective

- 45/46 -

products. By the exemption usually referred to in the literature as 'development risk'[4] and/or 'state of the art' exemption,[5] the producer may also be exempted from liability by proving that the defect in the product was not detectable by the state of scientific and technical knowledge at the time the producer placed the product on the market.[6]

In addition to the term 'state of the art', the term 'development risk' appears several times in the study when referring to the scope of the exemption. It is based on the fact that the term 'development risk' appears to be more widely used and generally accepted in the relevant literature. In view of the fact that the relevant documents (drafts, opinions, resolution papers)[7] produced during the process of drafting the Directive, as well as the Commission reports[8] resulting from the periodic reviews of the Directive, also use the term development risk as a designation of the exemption, the present study also uses the term of the exemption under this name. A distinction between the two different terms applied to the same exemption is justified because the term development risk may be preferable to the term state of the art, since development risk refers to undetectable defects, whereas state of the art refers to the state of the scientific, technological and safety standards in a given industry against which the detectability or non-detectability of a product defect must be judged, so that the term state of the art is relevant for determining whether a product is defective or not.[9] There is also a view in the literature which does not even consider the term development risk to be sufficiently expressive to designate the scope of the exemption case, because the ground for exemption refers not only to the risks of

- 46/47 -

products but also to their discoverability, thus accepting its content as broader than that suggested by the development risk, which is a common synonym for the exemption case.[10]

A study specifically examining the economic impact of the exemption (the Rosselli report) - which also formed the basis of the Commission's third report on the Directive - defines development risks in a laconic way as risks that only become apparent when the new product is used.[11] The possibility of producers exemption is summarised by Judit Fazekas as "the producer can be exempted by proving that the defect was undetectable by following the research and production protocol and by properly carrying out the checks on product safety standards".[12] With regard to the state of science and technology, it should be stressed that this is a condition which is an objective standard, namely the producer will not be able to obtain exemption merely by proving that it did not subjectively possess information which could have been used to detect the defect, nor can it be considered that the producer has taken all reasonable steps to obtain such knowledge.[13]

The objective nature of the state of scientific and technical knowledge was highlighted while providing an explanation of the concept in the CJEU's judgment in Commission v United Kingdom[14]. In the judgement, it was examined whether the Directive had been correctly implemented. When the English Consumer Protection Act[15] came into force, it provided, and still provides, for development risk in such a way as to provide for an exemption for producer as: "the state of scientific and technical knowledge at the relevant time was not such that a producer of products of the same description as the product in question might be expected to have discovered the defect if it had existed in his products while they were under his control where the state of scientific and technical knowledge at the time was not such that the manufacturer of products of the same description as the product in question could have been expected to have recognised the defect if it had existed in his products while they were under his control.[16] In opposing the implemented provision, the Commission argued that the United Kingdom legislature had significantly broadened the exemption under Article 7(e) of the Directive and converted the strict liability provided for in Article 1 of the Directive into liability based on fault.[17]

- 47/48 -

In the Commission's view, the state of the art in the Directive objectively refers to the state of the art,[18] not to the ability of the producer of the product or of a similar product to detect the defect. In contrast, the wording of the provision implemented by the United Kingdom, 'the manufacturer of products of the same description could have been expected to discover the defect', suggests that the exemption is based, as a subjective condition, on the reasonable conduct of the manufacturer.[19] The Commission argues that the manufacturer would be in an easier position to prove that it could not have detected the defect if it were required to demonstrate only that neither it nor a similarly situated manufacturer could have detected the defect, it had taken the normal precautions applicable to the industry concerned and had acted in accordance with the standard of ideal care. According to the Commission, this would be less onerous than proving, as required by the Directive, that the level of scientific and technical knowledge (objectively) was such that no one would have been able to detect the defect.

The United Kingdom, on the other hand, argued that the state of the art reflected in the Directive does not refer to what the producer concerned actually knows or does not know, but to the knowledge that similar producers in the category of the producer in question could objectively be expected to possess. It is precisely this objective level of knowledge that the implemented and contested provision requires as a condition for a successful exemption.[20]

According to the CJEU's judgement[21] the UK has correctly transposed the development risk exemption rule and perhaps, almost as importantly as complying with the harmonisation obligation, and maybe more importantly, if we look at the 'afterlife' of the exemption rule and its current reporting period, it has also provided some guidance on the interpretation of the exemption case in the reasoning of its judgement.

1) In its judgment, the CJEU explained that, when determining the duration of the risk of development, it is appropriate to start from the premise that the state of the art relates to the most advanced scientific and technical knowledge available at the time the producer placed the product on the market, and not specifically (only) to the practices and safety standards in the industrial sector in which the producer operates.[22]

2) Secondly, it should be noted that the provision granting the exemption does not take account of the level of knowledge of which the producer concerned was or could have been aware, whether actually or subjectively, but of the objective state of scientific and technical knowledge of which the producer was deemed to have been aware.[23]

- 48/49 -

3) Thirdly, it follows implicitly from the wording of the Directive that the relevant scientific and technical knowledge must have been available at the time the product in question was placed on the market.[24] It is worth mentioning here the question of the availability and meaning of the most advanced state of the art, objectively assessed. In the context of the question of accessibility, the argument in the Rosselli report suggests[25] that the level and state of knowledge, in the scientific community as a whole, must include all the data in the information/scientific cycle and that these data must also be accessible. In this respect, the possibility of access to knowledge by the producer should also be considered in terms of the rationality of the spreading of the available knowledge.

In the event that the producer succeeds in proving that the defect was undetectable at the time of placing the product on the market, and the injured party does not accept this, he will be obliged to prove that the producer had the possibility to detect and recognise the defect at the time of placing the product on the market. In the current allocation of development risk between producers and potential victims, the imaginary scales are tipped in favour of producers, since by regulating it as an exemption, the potential victim essentially bears the risk of scientific and technical progress.[26]

Considering that in the language of the present study, both the state of the art exemption and the development risk term are used for the naming of the exemption, it is therefore practical to state that the author also considers the latter, namely the term development risk as the name of the exemption. The development risk term is generally accepted - in accordance with the prevailing views in the literature - for the designation of the exemption case. The term development risk as an exculpatory circumstance is consistently understood to mean the risk of whether the burden of proving that a product defect is detectable or not, on the basis of the state of the art and information reasonably available to the producer, will be borne by the party causing the damage or the party suffering the damage.

- 49/50 -

II. The Emergence of 'Development Risk' as an Exemption in EU Law

If we look at the historical development of the Directive, we can conclude that from the Commission's proposal[27] in 1976 to the current normative text, the Directive has undergone a cardinal transformation. We note that it is not our intention to provide a complete overview of the changes and amendments to the wording of the Directive, but only to focus on the specific cases of exemption, the introduction of development risk in the Directive and the evolution of this specific exemption rule.

The Proposal adopted by the Commission did not even include development risk as an exemption. Article 1 of the Proposal provided that the producer of the product was liable for the damage caused by the defective product, irrespective of whether the producer knew or could have known of the defect. Article 1 of the Proposal went even further and extended the liability of the producer to product defects which are not recognisable in the light of the scientific and technological development, thereby making the producer liable for damage occurring within the scope of the development risk.[28] Part of the reasoning behind the rule is also set out in the preamble to the Proposal. In the Commission's view, equal and adequate protection of consumers can only be achieved by introducing liability independent of the fault or faultlessness of the producer of the defective and harmful product. The objectives pursued and achieved by the legislation can only be achieved by applying strict liability, since any other type of liability imposes almost insurmountable difficulties of proof on the injured party.[29]

Already in the preamble of the Proposal, the cost aspect of the liability formula is analysed and it is stated that the producer could include in the cost of production the costs of potential product damage when calculating the price of the products before placing it on the market. Such cost projections and cost planning by producers could be a way for them to share their liability costs among consumers.[30] In effect, it will be the rigour of strict liability that will force the producer to take into account the cost implications of potential damages, while at the same time, he is in a position to pass on and share these costs between all consumers of the same type of defect-free products. The Proposal also introduced a more consumer-friendly version of the concept of development risk. Although the rule did not fully pass through the various commenting bodies, it certainly underwent significant changes before the Directive was adopted in its final wording in the legislative procedure. The Proposal, which placed the bur-

- 50/51 -

den of development risk on manufacturers, provided that liability - for damage caused by products which could not be considered defective according to the state of scientific and technological development at the time of the placement on the market - could not be excluded. Otherwise, (by leaving the burden of development risk on consumers), the consumer would be exposed without protection to the risk that the defect in the product would only become apparent later, during use.[31]

In addition to these provisions, the possibility of exemption was also limited in the Proposal. Article 5 of the Proposal provided for two types of exemption for the producer: if he proves 1) that he did not place the product on the market, 2) or that it was not defective when he placed it on the market.[32] The first case, the proof of not placing the product into circulation, does not raise any particular issues, given that it is one of the cases for which exemption is granted under the current rules.[33] On the other hand, the second, namely proving that the product was not defective when it was placed on the market, was highly questionable. The reason for the questionability was that there was a significant discrepancy between the provisions of Articles 1 and 5 of the Proposal. While the first Article explicitly holds the producer liable for defects which are not recognisable in the state of scientific and technological knowledge, Article 5 requires the producer to prove that the product was free from defects when it was placed on the market as a condition for successful exemption. By leaving the development risk entirely on the producer's side, the exemption provided for in the second paragraph of Article 5 is rather weightless. This is because, if the producer is liable even for defects in the product which could not have been detected at the time when it was placed on the market in the light of the state of the art, it would hardly be able to prove effectively that the product in question was free from defects when it was placed on the market.

In assessing and evaluating the potential economic impact of the Proposal and, increasingly, of the legislation after its adoption, the Proposal has maximised the amount of damages that can be claimed as compensation for the strict liability imposed on producers. On the one hand, for personal injuries caused by products with the same or identical defects, it limited the liability of the producer to a maximum of 25 million European currency units.[34] On the other hand, as regards damage to immovable goods, the limit was set at 15.000. ECU in case of property at 50.000. ECU.[35]

The next major stage in the regulatory process and the next stage for development risk-settling was the European Economic and Social Committee (EESC). In its opinion, the EESC still highlighted as one of the most important princi-

- 51/52 -

ples on which product liability regulation should be based, the optimal way of sharing costs, namely the least costly but fairest way of sharing the financial burden of the damage caused to users by defective products and the costs of such damage.[36] In this context, the Committee has also assessed the issue of the allocation of development risk, but has not reached a definitive position on whether development risk should be covered by the Directive at all and, if so, which party should bear the burden of development risk.[37] The main reason for this division was that placing the development risk on producers could pull back innovation, and consequently regulation could put European sectors with strong R&D at a disadvantage, not only in Europe but also on the global market.[38] Those arguing against the inclusion of the development risk rule in the scope of the Directive have approached the cost of the rule against innovation from the perspective of the insurance sector.[39] Their argument was based on the assumption that insurance of unforeseeable risks by producers are likely to lead to such high costs that the producer could easily become uninterested to develop products. On the other hand, those in favour of the Directive's regulation of development risk and its transfer to the producers' side argued that a move towards adequate consumer protection and a liability regime free from fault requires that the Directive should cover these risks. In particular, because this is precisely the function of the insurance industry - to spread the risks among the insured through risk-sharing, while guaranteeing the possibility of recovery in the event of a covered insured event[40] - insurance companies may also be able to cover these costs.[41]

The dilemma of the regulatory justification for development risk and whether the risk should be placed on the producer or the victims' side also divided the European Parliament, which made significant changes[42] to the draft adopted by the Commission and passed through the Committee's filter. The European Parliament has completely reversed the logic of development risk setting. The draft EP opinion text provided that the producer is not liable if he can prove that the product cannot be considered defective according to the state of scientific and technological development at the time of marketing.[43] In addition to setting the burden of development risk on the harmful party, a sub-parag-

- 52/53 -

raph was added to Article 1, which would have effectively given the producer an additional exemption. Under this provision, the producer was not liable if, as soon as it became aware of the defect or ought to have become aware of it, it took all adequate and timely steps to inform the public and took all measures which could reasonably be expected in the circumstances of the case to remedy the harmful effects of the defect.[44] The provision would have essentially been an 'unspoken' extension of the scope of the exemptions, as a 'simple' but timely product recall and compliance with the producers' obligation to provide information could have resulted in exemption. The burden of proving compliance with these obligations would otherwise also have been placed on the producer under the draft text of the EP opinion.[45] The EP opinion would have left the system of grounds for exemption largely unchanged, except that, according to the wording of the opinion, the producer would have been exempted only if he could prove, taking all the circumstances into account, that he had not placed the product on the market or that it was not defective at the time of placing on the market, and would have provided the producer with a contributory damage like exemption.[46]

The discrepancy between Article 1 of the Proposal, which included liability for development risk, and Article 5, which provided for exemption, has certainly been reduced, as the EP opinion states, but the rules were far from being as well established as they are today.

In 1979, following amendments proposed by the European Parliament and the EESC, the Commission adopted the Amended Proposal,[47] which once again placed the risk of development on the producer by reinstating the 1976 Proposal's wording that the producer is liable for defects in products which were not known at the time of their being placed on the market, in accordance with the state of the art,[48] and by extending the scope of the exemption.[49]

The legislative procedure finally resulted in the adoption of a final version of the text,[50] which was also quite different from the Amended Proposal, and which provided a compromise solution between the Commission, which was in favour of shifting the development risk to producers, and the European Parliament, which was against it.[51] The dilemma of the allocation of development

- 53/54 -

risk ended up with a solution that was unfavourable to potential victims and favourable to producers. The liability provision in Article 1 covering development risk has been deleted. The non-detectability of the product defect in the light of the state of the art at the time of marketing has been regulated as a separate exemption. The compromise solution of leaving the burden of the development risk on the producer or the potential victim was to ensure in Article 15(b) of the Directive the possibility for Member States to maintain or introduce in their legislation, a derogation from Article 7(e). According to the Directive Member States can create legislation which makes the manufacturer liable even if he succeeds in proving that the defect of the product was not recognizable at the time when it was placed on the market according to the state of science and technology at that time.[52] In effect, Article 15 'outsourced' to the Member States the resolution of the almost nine-year 'dispute' between the Commission and the European Parliament on this issue. According to Article 15(b), when implementing the Directive, Member States have the possibility to decide to extend the liability of the manufacturer for defective products to defects which are not objectively measurable at the time of placing on the market and which are not recognisable according to the state of the art. In accordance with the rule, the eligibility of placing development risk on manufacturers is a matter for the national decision of the Member States. With this solution, the Directive does not have to declare the manufacturers' liability for development risks. However, by omitting the stated ground for exemption, Member States could provide for such an allocation of development risk. In addition to allowing Member States to derogate from the scope of the exemption for development risk under national law, the Directive also provided a monitoring obligation. The Commission has required reporting to the Council on the impact of the application of Article 7(e) and Article 15(1) (b) of the Directive by the courts on consumer protection and the functioning of the common market.[53] As a result of the monitoring and reporting exercise, the Council would decide, on a proposal from the Commission, on the repeal of Article 7(e), namely the scope of the exemption for development risk.[54]

Taking into account the different opinions on the deployment of development risk and the Directives' enabling norm allowing for further heterogeneous national regulation, it is useful to provide a comprehensive summary of national regulatory practices following the transposition of the Directive and the current EU regulation of development risk.

- 54/55 -

III. Member States' Regulatory Practices on 'Development Risk'

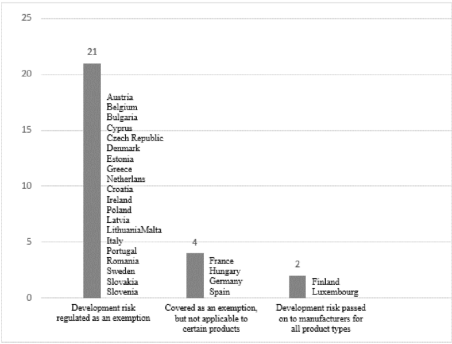

Since it entered into force, only two Member States, Finland and Luxembourg,[55] have not transposed the scope of the exemption and thus extended the producers' liability to cover defects in products which were not technically and scientifically known at the time of their placing on the market. Three Member States (Germany, France and Spain)[56] have either made the scope of the exemption partially applicable by not allowing this form of producers' exemption for certain products,[57] or have not narrowed the scope of the exemption but have narrowed the scope of the Directive by excluding certain products from its scope.[58]

In the case of Finland and Luxembourg,[59] the exclusion of this form of manufacturer's exemption was not unanimously welcomed by the producer organisations. Their position was based on the fact that the exclusion of the possibility of state of the art exemption was likely to discourage scientific and technical research and make it more difficult to import foreign products into these countries. They considered that exports to the Finnish and Luxembourg markets would be made more difficult because any producer exporting to these countries would have to take out separate insurance to cover the risk of damage resulting from development.[60] The additional insurance would lead to an increase in costs for the producers and the increased costs would also have a negative impact on the final price of the products. However, these negative arguments, which at the same time justify the unsustainability of the provisions in force, have not yet been confirmed in the Commission's second report.[61]

If we look at the implementation practice of development risk in the Member States after the entry into force of the Directive, it can be seen that, with a few exceptions, the vast majority of Member States have allowed producers to exempt themselves on the grounds of development risk. This picture has not changed

- 55/56 -

much until today. Looking at current implementation practices in the Member States, it can be concluded that there has been no significant change in the Member States' approach to development risk. Finland and Luxembourg still do not allow for this type of exemption for the reasons discussed above,[62] while France and Spain narrow the scope of products for which the state of the art defence can be invoked,[63] namely they do not allow for exemption under Article 7(e) of the Directive for certain types of products, and Germany narrows the scope of the Directive.

With regard to Germany, it could be argued that the Member State has implemented an unfriendly transposition of the Directive for potential victims since the German legislator has made use of all the derogations provided for in the Directive and has designed the German product liability legislation in accordance with it.[64] Although the German Product Liability Act[65] allows for producers the exemption for development risk,[66] however it excludes medicinal products from the scope of product liability. Under paragraph 15 of the ProdhaftG, which narrows the scope of product liability, the provisions of the Product Liability Act are not applicable if, as a result of the administration of a medicinal product intended for human use, which was distributed to the consumer within the purview of the German Medicinal Products Act[67] and which is subject to compulsory marketing authorisation or is exempted by ordinance from the need from a marketing authorisation, a person is killed, or the body or the health of a person is damaged. The legal policy justification behind the German Product Liability Act is that the German Medicines Act explicitly provides the strict liability of pharmaceutical producers[68] for death, personal injury or damage to health caused by the use of a medicinal product for human use subject to marketing authorisation or exempted by regulation.[69] The producer is also liable for damages under that provision even if the side-effects to the medicinal product were not known at the time of its placing on the market. Although pharmaceuticals as a type of product fall outside the scope of the specific German product liability rules, the German Medicines Act also makes the producer liable for development risks, and therefore the right of potential victims to compensation is also guaranteed for this type of "product".

- 56/57 -

France, like Germany, also provides development risk as an exemption,[70] but excludes this type of exemption for some products.[71] According to a narrowing rule in the Civil Code, "the manufacturer may not rely on the exemption provided for in Article 1245-10 (4) if the damage was caused by a component of the human body or by products derived from it".[72] The scope of an element of the human body or products derived from it includes, in addition to blood and blood products, parts of the human body and organs. The main reason for the restriction on blood and blood products is that blood is not immediately used 'pure' after it has been collected, but must undergo processing before it can be used as a blood product. By contrast, the range of elements of the human body or products derived from it does not undergo such processing and transformation in the case of organs, so it is not entirely clear why the French legislator has excluded the possibility of invoking the risk of development for all products derived from the human body.

Spain regulates the normative material on product liability under a comprehensive complex piece of legislation, the General Consumer and User Protection Act.[73] The law also provides for producers the exemption in the case of product defects that are not recognisable in the state of science and technology at the time of marketing,[74] but defines the scope of products for which the producer cannot benefit from this exemption in an even broader way than the German and French legislation. The law places the risk of development on the manufacturer in the case of medicinal products, foodstuffs or foodstuffs intended for human consumption, with the exception that in the case of these products, the responsible persons may not invoke Article 140(1).[75] Of the rule that narrows the scope of the exemption, it is worth highlighting the "intended for human consumption" phrase, which still allows the producer to invoke the development risk for medicinal products outside this scope, for example for veterinary use. The reason given for the exclusion of the exemption in the product areas referred to is that these areas may be the most affected in terms of development risk. Of the rule that narrows the scope of the exemption, it is worth highlighting the "intended for human consumption" turn of phrase, which still allows the producer to invoke the development risk for medicinal products outside this scope, for example, for veterinary use.[76]

- 57/58 -

Last but not least, in terms of the enabling rule allowing derogations from the Directive's rules on development risk, Hungary deserves to be highlighted. With the entry into force of the Hungarian Civil Code,[77] the Product Liability Act[78] was repealed and the rules on product liability were incorporated into the tort liability rules of the Civil Code. The Civil Code, like the legal sources analysed above, also provides for the possibility of producer exemption from development risk. According to § 6:555 (1) (d), the producer is exempted from liability if he proves that "at the time the product was placed on the market by him, the defect was not detectable by the state of science and technology". The legislator applies the provision on medicinal products, which is a product-specific limitation of the exemption case, by excluding the application of development risk in the case of damages caused by the use of a medicinal product in accordance with its prescription.

IV. Summary

For ease of reference and illustration, the following summary graph shows the current regulation of development risk in the Member States. After the entry into force of the Directive, and even with the gradual increase in the number of EU Member States, national regulatory practice has not become much more heterogeneous than already identified by the Commission in its' 1st Report. Apart from the Member States identified in the 1st Report, all new Member States, with the exception of Hungary, have implemented this exemption and continue to do so today.

- 58/59 -

Figure 1. Regulation of development risk in the Member States[79]

The allocation of development risk to the producer or even to the potential victims is not only a legal and legislative issue, but also an economic policy issue affecting economic efficiency. This regulatory issue may largely depend on the effectiveness of the economic arguments behind the legislation, and also the lobbying activities and its' efficiency of the parties representing them. From the perspective of the potential injurious party, it should not be ignored that, the product liability rule allowing development risk as an excuse - especially if setting it in parallel with the Directive's standard obligations of the injurious party to prove - may be able to make it significantly difficult for the injurious parties to assert a claim. This may also have the potential to have a negative impact on the willingness of the injured party to enforce claims in general. In response to this the EU legislator has launched a review of the Directive and the draft Directive[80] adopted in 2022 would, for example, operate with a radically different, reformed system of proof. However, it is also not impossible that a general ret-

- 59/60 -

hinking of development risk in a more favourable way for the potential victims could be on the agenda of the EU legislator.

Literature

• Dielmann, Heinz J. (1986): The European Economic Community's Council Directive on Product Liability. In: International Lawyer. No. 4., Vol. 20/1986.

• Fairgrieve, Duncan - Goldberg, Richard (2020): Product Liability. Third Edition. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

• Fairgrieve, Duncan (2005): Product Liability in Comparative Perspective. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

• Fazekas, Judit (2007): Fogyasztóvédelmi jog (Consumer protection law). CompLex Kiadó, Budapest.

• Fazekas, Judit (2022): Fogyasztóvédelmi jog 2.0 (Consumer protection law 2.0). Gondolat Kiadó, Budapest.

• Fuglinszky, Ádám (2015): Kártérítési jog (Tort law). HVG-ORAC Lap- és Könyvkiadó Kft., Budapest.

• Koziol, Helmut - Green, Michael D. - Lunney, Mark (2017): Product Liability. Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin.

• Linger, Lori M. (1999): The Products Liability Directive: A Mandatory Development Risks Defense. In: Fordham International Law Journal. Vol. 14/1999, Issue 2., Art. 6.

• Machinowsky, Piotr (2016): European Product Liability, An Analysis of the State of the Art in the Era of New Technologies. Intersentia Ltd., Cambridge

• Surányi, Miklós (1994): A termékfelelősség alapjai és kockázatai (Product liability basics and risks). Építésügyi Tájékoztatási Központ Kft., Budapest.

• Váradi, Ágnes: A biztosítás komplex fogalma (The complex concept of insurance). In: Jog-Állam-Politika. 2010/4.

• Wellmann, György (ed.) (2018): A Ptk. magyarázata V/VI., Kötelmi jog első és második rész (Explanation of the Civil Code, Part V/VI, Law of Obligations, Parts I and II). HVG-ORAC Lap- és Könyvkiadó Kft., Budapest.

European Union Documents

• Adoption of the amended proposal by the Commission, in: Official Journal of the European Communities, C 271, Volume 3, 1979, COM/79/415.

• Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council on liability for defective products, (Draft directive), 2022.09.28.

• Fondasione Rosselli: Analysis of the Economic Impact of the Development Risk Clause as provided by Directive 85/374/EEC on Liability for Defective Products, Study for the European Commission Contract No. ETD/2002/B5.

• First Report on the Application on the Council Directive on the Approximation of Laws, Regulations and Administrative Provisions of the Member States Concerning Liability for Defective Products, 1995, Brussels, COM (95) 617.

• Fourth report on the application of Council Directive 85/374/EEC of 25 July 1985 on the approximation of the laws, regulations and administrative provisions of the Member

- 60/61 -

States concerning liability for defective products amended by Directive 1999/34/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 10 May 1999.

• Lovells: Product liability in the European Union, A report for the European Commission

• European Commission Study MARKT/2001/11/D, Contract No. ETD/2001/B5-3001/D/76, 2003.

• Opinion of the European Economic and Social Committee, in: Official Journal of the European Communities, C 114, Volume 22, 1979, Document C:1979:114:TOC, COM1976, 372.

• Opinion of the European Parliament, in: Official Journal of the European Communities, C 127, Volume 22, 1979, Document C:1979:127:TOC, Official Journal of the European Communities, C 127, 21 May 1979.

• Official Journal of the European Communities, L 210, Volume 28, 1985, J OL/1985/210/29.

• Proposal for a Council Directive Relating to the Approximation of the Laws, Regulations and Administrative Provisions of the Member States Concerning Liability for Defective Products, COM/76/372.

• Report from the Commission on the Application of Directive 85/374 on Liability for Defective Products, 2001, Brussels, COM(2000) 893.

• Report from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council and the European Economic and Social Committee on the Application of the Council Directive on the approximation of the laws, regulations, and administrative provisions of the Member States concerning liability for defective products (85/374/EEC), COM/2018/246.

• Third report on the application of Council Directive on the approximation of laws, regulations and administrative provisions of the Member States concerning liability for defective products (85/374/EEC of 25 July 1985, amended by Directive 1999/34/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 10 May 1999).

Sources of law

• Act V of 2013 on the Civil Code.

• Act X of 1993 on Product Liability.

• Code Civil.

• Consumer Protection Act, 1987, UK.

• Council Directive of 25 July 1985 on the approximation of the laws, regulations and administrative provisions of the Member States concerning liability for defective products (85/374/EEC).

• Gesetz über den Verkehr mit Arzneimitteln (Arzneimittelgesetz - AMG).

• Gesetz über die Haftung für fehlerhafte Produkte (Produkthaftungsgesetz - ProdHaftG).

• Royal Legislative Decree 1/2007, of 16 November, Approving the Consolidated Text of the General Consumer and User Protection Act and Other Complementary Laws.

Court judgements

• Judgment of the Court [Fifth Chamber) of 29 May 1997. Commission of the European Communities v United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, Case C-300/95. European Court Reports 1997, p. I-0264. ■

NOTES

[1] Supported by the ÚNKP-23-3-II-SZE-93 New National Excellence Program of the Ministry for Culture and Innovation from the source of the National Research, Development and Innovation Fund.

[2] Council Directive of 25 July 1985 on the approximation of the laws, regulations and administrative provisions of the Member States concerning liability for defective products (85/374/EEC), hereinafter referred to as 'the Directive'.

[3] Directive Article 7. a-f).

[4] Inter alia: Fuglinszky, 2015, 655.; Wellmann (ed.), 2018, 658.; Fairgrieve, 2005, 320.; Machinowsky (ed.), 2016, 75.; Koziol - Green - Lunney, 2017, 542.

[5] Fazekas, 2007, 119.; Fazekas, 2022, 142.; Surányi, 1994, 22.; Fairgrieve - Goldberg, 2020, 484.

[7] Inter alia: Opinion of the Economic and Social Committee, in: Official Journal of the European Communities, C 114, Volume 22, 1979, Document C:1979:114:TOC, COM1976, 372, 17., Opinion of the European Parliament, in: Official Journal of the European Communities, C 127, Volume 22, 1979, Document C:1979:127:TOC, Official Journal of the European Communities, C 127, 21 May 1979, 62.

[8] First Report on the Application on the Council Directive on the Approximation of Laws, Regulations and Administrative Provisions of the Member States Concerning Liability for Defective Products, 1995, Brussels, COM (95) 617., Report from the Commission on the Application of Directive 85/374 on Liability for Defective Products, 2001, Brussels, COM(2000) 893., Third report on the application of Council Directive on the approximation of laws, regulations and administrative provisions of the Member States concerning liability for defective products (85/374/EEC of 25 July 1985, amended by Directive 1999/34/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 10 May 1999). Fourth report on the application of Council Directive 85/374/EEC of 25 July 1985 on the approximation of the laws, regulations and administrative provisions of the Member States concerning liability for defective products amended by Directive 1999/34/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 10 May 1999., Report from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council and the European Economic and Social Committee on the Application of the Council Directive on the approximation of the laws, regulations, and administrative provisions of the Member States concerning liability for defective products (85/374/EEC), COM/2018/246.

[9] Fairgrieve, 2020, 484.

[10] Fondasione Rosselli: Analysis of the Economic Impact of the Development Risk Clause as provided by Directive 85/374/EEC on Liability for Defective Products, Study for the European Commission Contract No. ETD/2002/B5, 20. (hereinafter: Rosselli-report).

[11] Rosselli-report, 22.

[12] Fazekas, 2022, 142.

[13] Machinowsky (ed.), 2016, 75.

[14] Judgment of the Court (Fifth Chamber) of 29 May 1997. Commission of the European Communities v United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, Case C-300/95. European Court Reports 1997, p. I-0264.

[15] Consumer Protection Act, 1987.

[16] Consumer Protection Act 4 (1) e).

[17] Commission of the European Communities v United Kingdom, 16. paragraph.

[18] Fairgrieve, 2020, 484.

[19] Commission of the European Communities v United Kingdom, 17. paragraph.

[20] Fairgrieve, 2005, 175.; Fairgrieve, 2020) 490-491.

[21] Commission of the European Communities v United Kingdom, 39. paragraph.

[22] Machinowsky (ed.), 2016, 78.; Rosselli-report, 23.

[23] Commission of the European Communities v United Kingdom, 27. paragraph.

[24] Commission of the European Communities v United Kingdom, 28. paragraph.

[25] In such an approach, there may be a completely different perception between a study published in the United States in an international English-language journal and a study published only in Chinese in a local journal and not in the international academic community. With regard to the latter, in the context of knowledge published in a Chinese journal in a purely domestic context, it would be unreasonable to hold a European manufacturer liable for the error found in the study, as it cannot reasonably be expected to have information about this knowledge published solely in Chinese. See Rosselli-report, 23.; Fairgrieve, 2020, 492.

[26] Fazekas, 2022, 142.

[27] Proposal for a Council Directive Relating to the Approximation of the Laws, Regulations and Administrative Provisions of the Member States Concerning Liability for Defective Products, COM/76/372, (hereinafter: Proposal).

[28] Fairgrieve, 2020, 480.; Proposal art. 1. (2) paragraph. The producer is liable even if the product could not have been regarded as defective, having regard to the scientific and technological development at the time when the product was placed on the market.

[29] Proposal preamble 8. paragraph.

[30] Proposal preamble 9. paragraph.

[31] Proposal preamble 9. paragraph.

[32] Proposal art. 5.

[33] Directive art. 7. a), Ptk. 6:555. § [1) a).

[34] Proposal art. 7. [1).

[35] Proposal art. 7. [2).

[36] Linger, 1999, 481.; Opinion of the Economic and Social Committee (hereinafter: EESC proposal), in: Official Journal of the European Communities, C 114, Volume 22, 1979, Document C:1979:114:TOC, COM1976, 372, 16.

[37] EESC proposal 17., 1.2.1. paragraph.

[38] EESC proposal 17., 1.2.1.1. paragraph.

[39] EESC proposal 17., 1.2.1.1. paragraph, See more on the links between development risk and insurance Rosselli-report, 67-73.

[40] Varadi, 2010, 59.

[41] Commission proposal 17., 1.2.1.2. paragraph.

[42] Opinion of the European Parliament (hereinafter: EP Opinion), in: Official Journal of the European Communities, C 127, Volume 22, 1979, C:1979:127:TOC.

[43] EP Opinion, 62.

[44] EP Opinion, 63.

[45] EP Opinion, 63.

[46] EP Opinion, 64.

[47] Adoption of the amended proposal by the Commission (hereinafter: Amended proposal), in: Official Journal of the European Communities, C 271, Volume 3, 1979, COM/79/415, 3-11.

[48] Amended Proposal, 7-8.

[49] In addition to proving that the producer did not place the product on the market and that the product was not defective when placed on the market, the possibility of proving that the producer did not manufacture the product for sale, hire or any other commercial sale or that it did not manufacture or distribute the product in the course of its business has been introduced as an exemption. Amended Proposal, 8-9.

[50] Official Journal of the European Communities, L 210, Volume 28, 1985, J OL/1985/210/29, 29-33.

[51] Fairgrieve, 2020, 480.

[52] Dielmann, 1986, 1398.

[53] Fairgrieve, 2020, 486.

[54] Directive Art. 15. (3).

[55] First Report on the Application on the Council Directive on the Approximation of Laws, Regulations and Administrative Provisions of the Member States Concerning Liability for Defective Products, 1995, Brussels, COM (95) 617, 4., (hereinafter: 1st report).

[56] Lovells: Product liability in the European Union, A report for the European Commission European Commission Study MARKT/2001/11/D, Contract No. ETD/2001/B5-3001/D/76, 2003, 55. (hereinafter: Lovells-report) and Rosselli-report, 28.

[57] Spain has excluded the possibility of using development risk as an exemption for medicinal products, foodstuffs and food and food products intended for human consumption, while France has excluded the possibility of using development risk as an exemption for human organs. Fairgrieve, 2020, 486.; Lovells-report, 90-92.; Rosselli-report, 27.

[58] Germany has excluded the 'product group' of medicinal products from the scope of the Directive. See: Ulrich Magnis in. Machinowsky (ed.), 2016, 252.

[59] In the case of Luxembourg, the omission of the exemption was not entirely new, since even before the adoption of the Directive, case law had already held producers liable for development risks. See: Report from the Commission on the Application of Directive 85/374 on Liability for Defective Products, 2001, Brussels, COM(2000) 893, (hereinafter: 2nd report).

[60] Rosselli-report, 29.

[61] 2nd report, 17.

[62] COM(2018) 246, 4. (hereinafter: 5th report).

[63] Fairgrieve, 2020, 486.

[64] Ulrich Magnis in. Machinowsky (ed.), 2016, 241.

[65] Gesetz über die Haftung für fehlerhafte Produkte (Produkthaftungsgesetz - ProdHaftG).

[66] ProdHaftG § 1 (2) 5.

[67] Gesetz über den Verkehr mit Arzneimitteln (Arzneimittelgesetz - AMG), the scope of which covers medicinal products for human use. Substances or preparations of substances intended for use in or on the human body which are intended to have properties for treating, alleviating or preventing human diseases or conditions, or which may be used in or administered to a human body or body surface to correct or modify physiological functions or to make medical diagnoses. AMG § 2 (1).

[68] Ulrich Magnis in. Machinowsky (ed.), 2016, 270.

[69] AMG § 84 (1).

[70] Code Civil 1245-11.

[71] Jean-Sebastian Borghetti in. Machinowsky (ed.), 2016, 214.

[72] Code Civil 1245-11. art.

[73] Royal Legislative Decree 1/2007, of 16 November, Approving the Consolidated Text of the General Consumer and User Protection Act and Other Complementary Laws.

[74] Royal Legislative Decree 1/2007 140. cikk (1) e).

[75] Royal Legislative Decree 1/2007 140. cikk (3).

[76] Martin-Casals - Sole-Felia in. Machinowsky (ed.), 2016, 444.

[77] Act V of 2013 on the Civil Code (hereinafter: Ptk.).

[78] Act X of 1993 on Product Liability (hereinafter: Tftv.).

[79] The summary chart is the author's own editing based on Commission reports on the transposition of the Directive, its effects and its practices in the Member States.

[80] Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council on liability for defective products, 2022.09.28.

Lábjegyzetek:

[1] A szerző PhD-hallgató, Deák Ferenc Állam- és Jogtudományi Kar Doktori Iskolája egyetemi tanársegéd, Széchenyi István Egyetem, Deák Ferenc Állam- és Jogtudományi Kar, Polgári Jogi és Polgári Eljárásjogi Tanszék Ügyvédjelölt, Vándor, Keserű, Trenyisán & Partners Ügyvédi Társulás Egyetemi tanulmányait a Széchenyi István Egyetem Deák Ferenc Állam- és Jogtudományi Karán végezte 2015-2020 között, summa cum laude minősítéssel. 2020 óta folytat doktori tanulmányokat a Deák Ferenc Állam- és Jogtudományi Kar Doktori Iskolájában PhD-hallgatóként, míg 2021-tol egyetemi tanársegédként vesz részt a Kar Polgári Jogi és Polgári Eljárásjogi Tanszékének munkájában. Oktatói, kutatói minőségben aktív résztvevője a Kar fontosabb kutatási projektjeinek, többek között az önvezető gépjárművek, mesterséges intelligencia és az online platformok tárgykörében. Fő kutatási területeit a kártérítési jog, ezen belül kiemelten a termékfelelősség képezi. A PhD-tanulmányok folytatása és az oktatási tevekénység mellett gyakorló jogászként a Vándor, Keserű, Trenyisán & Partners Ügyvédi Társulás berkeiben ügyvédjelöltként tevékenykedik. dr.frank.mate@gmail.com