Róbert Zsolt Faránki-Szalay[1]: The market economy operator principle (MEOP) in EU State Aid Law (Annales, 2024., 125-137. o.)

https://doi.org/10.56749/annales.elteajk.2024.lxiii.7.125

Abstract

Article 107(1) TFEU prohibits granting state aid as a rule of thumb. However, TFEU remains silent regarding the notion of state aid and the possible justification of public financing through which states may prove that measures do not constitute state aid. However, soft law and case law provide the market with some solutions, inter alia, the Market Economy Operator Principle (MEOP/MEIP) test, the due running of which may prove state financing to be state-aid free, therefore escaping the prohibition of the TFEU. In this case, financing is not to be confused with a completely different scenario in which a measure does constitute state aid but is deemed compatible with the internal market (e.g., in the case of some subsidies).

Keywords: MEIP; MEOP; state aid; pricing

I. Background

Market Economy Operator (MEO)-conformable financing is the most frequent and typical resort of a state that is keen on providing financial support to undertakings but not willing to do so according to the provisions that justify granting state aid under Article 107(2)(3) TFEU. A State cannot provide such amounts of money without restrictions, as aid such as this could easily distort competition in the internal market as set out in Article 107(1) TFEU. On the other hand, as Article 354 TFEU declares property ownership systems as neutral under EU law, stemming from the equal treatment principle, states cannot be prohibited from engaging in and undertaking financial activities like any other entity,[1] as they may function in a 'dual capacity', with no difference made between the investments of public and private entities.[2]

- 125/126 -

States cannot, however, give support to the detriment of the free competition on the internal market, as the assets, the actio radius, and the economic power of states are usually beyond what individual market entities possess. Keeping in mind that some undertakings are certainly more significant actors than some states,[3] generally, states are always more resourceful - not to mention their exclusive capability to legislate, by which they can easily overcome any obstacles, not to mention their inexhaustible power of printing banknotes. I am deeply convinced that state aid rules exist not only to protect market economy competitors, but also to protect the competitors of smaller states, and smaller states themselves from larger states' competitors (and the larger states themselves). It does not take much imagination to envisage the outcome of a battle between a Hungarian company and its German counterpart, with the backing of their governments. There is not much debate about what advantage this would mean for the German company compared to the Hungarian one if the former enjoyed the limitless support of its government. Germany's real GDP per capita is about 2.5 times greater than Hungary's,[4] and its nominal GDP (so to speak, the total GDP at their disposal) is about 23 times bigger than Hungary's.[5] In a simplified way, this means that if the German government wanted a certain company to overpower its Hungarian competitor, it would have 23 times more assets to back it up, resulting, in my opinion, in the total destruction of the competing Hungarian company. Due to this simple logic, I am convinced that state aid rules, first and foremost, benefit smaller Member States (if we talk about the issue's national economic dimension) and may save them from the unimaginably huge and relatively inexhaustible resources of the larger Member States. In terms of the second dimension, certainly, the core of state aid rules is to prevent any kind of distortion in the internal market to the detriment of all undertakings of any background, and, consequently, to the detriment of the whole European economy, which ongoing distortion it may lead to if not regulated and monitored duly. This is why I strongly claim that state aid rules are not a matter of law, but rather a matter of the natural symbiosis of economic reality and politics that is clearly visible from the imprint of the General Court's and the Commission's decisions. Further, also from the fact that state aid law is, exaggeratedly, basically the billion-page long legal branch of three paragraphs of the TFEU comprising thousands of cases and hundreds of soft law communications, along with some opinions and recommendations, corroborating the claim that it was developed case by case, always reflecting the Zeitgeist and economic reality. Additionally, along with massive political contemplations, only about 1 percent of it and its raison d'être are laid down in actually binding legal sources,

- 126/127 -

unlike in the case of criminal law, procurement law, or civil law, etc. The truth be told, even this 1 percent blends politics and economic reality. To mention just one point: even according to the TFEU's explicit and already mentioned provision ex lege, per se, the TFEU makes it compatible with the rules on the common market to grant aid to remedy the consequences of the division of Germany, but not to remedy explicitly the economic divisions of Italy's south and north, Ireland's east and west, or regions of Hungary or Poland or Romania or the Slovak Republic. While these imbalances may be remedied indirectly by the GBER or de minimis regulations, they are not directly based on the TFEU itself. However, the TFEU provides a variety of cases in which it considers aids compatible with the internal market and also enables the Commission to establish detailed rules and legal bases, thereby leaving the door open to granting state aid if justified by the reality of economic dictates, and, plainly put, when political games play a role. However, there is a balance to be struck between law, politics, and economics, just like there are developments in other fields of competition law - for instance, balancing the positive outcomes of the restriction of competition with the need for regulation and market behaviour restrictions.[6]

However, the state can act - just as any other market player may - because, as the communis opinio holds, if a private actor would undertake the same action and the state merely steps in to do it instead, no harm is done. What is dictated by fair market rules and does not confer uneven advantages is, essentially, not wrongful. The hardship of assessing what a market economy player would and would not do and on what terms is a shaky and highly hypothetical task, albeit still the core of state financing. However, predicting what a market economy operator would do remains guesswork. Such guesswork - that must be corroborated almost as if it had actually occurred - forms the basis of this entire concept. It is grounded in 'what if' scenarios that, in criminal law, would render the matter entirely inadmissible. Yet, interestingly, this constitutes the centrepiece of this field of state aid law - or 'state financing law' - governing and deciding the fate of billions of euros and shaping the present and future of the internal market in economic terms, all based on a hypothetical. This 'what if', therefore, has to become an 'it is' and an 'it is not' - rock hard - mainly without the specifics being defined by consistent case law. The State acts out of its market economy operator character "whenever...(it) makes available to an undertaking funds which in the normal course of events would not be provided by a private investor applying ordinary commercial criteria and disregarding considerations of a social, political or philanthropic nature",[7] when the recipient "receives an economic advantage which it would not have

- 127/128 -

obtained under market conditions"[8] due to the fact that the State has engaged in a transaction that a market economy operator would never have.[9] This approximation applies to all kinds of transactions, which is why some jurisconsults believe that the basis of this kind of acting is the 'market economy operator principle' (MEOP),[10] and specific ramifications of it, like the 'market economy investor principle' (MEIP). The latter concerns when the transaction is about investing, or the 'private debtor principle/market economy debtor principle' (MEDP), when the State acts in the character of a debtor, triggering different regimes to assess its behaviour (as the core premise is that the state cannot repay or recover more than it duly should, manifesting for the first time explicitly in 2019 in a Polish case concerning motorway concessions[11]). There are, however, dissenting opinions about this, as well. In private correspondence on 9 August 2022, Professor Phedon Nicolaides stated the following to me about the relation between MEOP and MEIP: "There is no consensus in the profession or the case law. They are treated as synonymous. However, the Commission tends to use MEO to assess the management of infrastructure and the MEIP to assess injections of capital or provision of loans. But the logic is exactly the same." The logic I intend to follow in this paper is that I consider MEIP a subcategory of MEOP in connection with investments. What we do know for sure, however, is that the MEIP first appeared and immediately became of landmark importance in 1984 when the Commission issued its Communication on Government Capital Injections,[12] and ever since, the Commission has brought it up as an exception to general TFEU-stipulated state aid provisions. Recently, however, it has stated that it considers MEIP a general test rather than an exception, making it a vital part of state aid law and representing the constantly changing character of this branch of law.

There are various tools in the hands of economic actors (and ultimately, in the hands of the Commission) to help them decide whether a transaction is in line with the MEO criteria. In my opinion, one of the most insightful examples of this is the case of Milan Airport,[13] in which the Commission identified significant criteria that must be met to align with the MEO standard (and its special form, MEIP). These conclusions were approved by the General Court and later the Court as well, after a lost annulment procedure and a similarly unsuccessful appeal. The specialty of the three decisions is not only the harmony manifesting on all three levels but also that, by reading the decision of the Commission, we can easily identify what criteria should have been met

- 128/129 -

to determine if the measure in question was in line with MEIP terms (in this specific case, the Council of the City of Milan, Italy, was found to have been acting in a way that was incompatible with the character of MEO). It overstepped its economic borders and hence granted state aid, which activity, in the absence of any justification (as mentioned before), was found to be incompatible with the common market. The definition of MEI (market economy investor) behaviour in this case is outlined as not necessarily the attitude of a normal investor who invests capital for the purpose of realising a profit in a relatively short time. It must, however, at least be the conduct of a private holding company or a group of private undertakings which is pursuing a general or sectoral structural objective and has longer-term prospects of profitability in mind. A private investor may provide capital to ensure the survival of an undertaking that is experiencing temporary difficulties but is still capable of recovery. However, when the capital injected by a public investor does not have long-term prospects of profitability, the capital injection may be considered aid in line with the meaning of Article 107 TFEU. It is then necessary to go back in time to the point at which the financial support measures were taken to assess whether the State's behaviour was economically rational, and judgements should not be based on the situation that subsequently developed. The recent decision of the Court concerning Wizzair in Romania[14] also emphasised the need to scrutinise the situation at the time of the decision and whether the decision maker made an ex ante forecast or not.

II. MEIP in practice: the Milan Airport case

I hereby detail the seven aspects I observed that the investment failed to meet, but would have been necessary for the state to have been aligned with the MEIP standard in the Milan Airport case.

First, it lacked a multi-annual loss coverage strategy as part of the strategic business plan. As Italy argued, while the decisions to cover losses were formally taken on an annual basis, the multi-annual strategy to cover losses over the restructuring period could not have been renegotiated annually, and the results thereof could only be assessed over a multi-annual period. The Commission's reaction thereto was that, given that the preparation of a new business plan normally involves an assessment of the company's business strategy to determine whether the company should continue to follow a pre-existing strategy or change it, it could have been revised at any time to take account of market developments. Italy argued furthermore that the closure of Alitalia's hub airport in 2007 had serious consequences for the activities of SEA Handling (a subsidiary of the company operating the airport, which is more than 99 per cent state-

- 129/130 -

controlled). The consequences that had an impact on the financial performance of the company were exacerbated by the economic downturn, forcing SEA (the 99% State-controlled company operating the airport) to reassess the viability of the hub model and to assess the possibility of opting for a different business model. Instead of outsourcing ground handling services, SEA finally created a new business model. The new model required the tight control of ground handling activity, which demonstrated that SEA had made a rational decision to continue to cover the operating losses of its subsidiary, SEA Handling, to restore the profitability of its ground-handling business. The Italian authorities upheld that the unforeseen external circumstances fully justified the revision of SEA's strategy for its subsidiary and that it did not, in any way, jeopardise SEA's plan to restore the long-term profitability of its ground handling business. The Commission counter-argued however, by stating that while the existence of a multi-annual strategy for loss coverage by the Italian authorities had been noted, the Commission still considered that this strategy would not correspond to the behaviour of a prudent private investor because while any restructuring process may take several years to achieve results, a prudent private investor would not make a multi-annual commitment in the absence of a clear vision (but would try to decide each year whether to inject new capital into the company, taking into account the results of the restructuring process and the prospects of future viability). In the present case, a private investor would certainly have reassessed the strategy in 2003 or 2004, when it was already clear that the objective of restoring profitability by 2005 was simply not feasible, but in any event, at the latest in 2005, once it became convincingly clear that the objective originally pursued had not been achieved. A private investor pursuing a long-term loss cover strategy, assuming in any event the absence of binding legal constraints, would have reviewed the strategy each time it was asked to provide funds to cover SEA Handling's losses. Furthermore, a decision of such importance as a capital injection, which requires the approval of the general meeting, cannot be considered simply a step in the implementation of a general decision to cover future losses - and decisions to cover future losses over several years are not mentioned in SEA Handling and SEA's strategic business plans. SEA's governing body did not make a formal, binding commitment, based on a business plan, that SEA would make specific capital injections over a specified number of years. The decisions were mostly concerned with restructuring SEA Handling and not the coverage of losses over several years. In any event, a private investor would not have undertaken to cover losses over several years without at least a preliminary estimate of the total costs.

Second, making a capital injection without a detailed business plan for an undertaking in difficulty would not be acceptable for an MEI. The core of the issue is that where public authorities provide capital to an undertaking in financial difficulty, it shall automatically be considered likely that providing the funds involves state aid, given the risks involved, as such investments very rarely yield returns that are acceptable

- 130/131 -

to private investors in a market economy. Such capital injections must, therefore, be notified in advance to the Commission for approval as State aid, as stipulated by Article 108(3) TFEU. In this case, the state's decision does not appear to have been based on a detailed business plan demonstrating that SEA Handling was in any way capable of improving its situation and restoring profitability within a reasonable timeframe. [1] A market investor would not have made these capital injections without a business plan based on sound and reliable assumptions and without sufficient details, which would have accurately described the measures necessary to restore the company's profitability, analysing possible scenarios and demonstrating that the investment (taking into account the inherent risks) would ever generate a satisfactory return for the investor in terms of dividends, increased shareholder value or other benefits. (The Italian authorities did not argue that the services are ones of general economic interest which the market could not provide.) [2] The business plans submitted were not sufficiently detailed to justify such a decision made by a private investor in a market economy. More precisely, the plans were not 'rescue plans' based on which a prudent private investor could make a significant capital injection into a company that had been in economic difficulty since its creation. The plans were not based on an in-depth analysis of the causes of the difficulties and the measures addressing them, nor did they assess the impact of improved productivity on the overall financial performance of the undertaking, nor did they set out specific measures to be taken. [3] There would have been alternatives. In particular, in a market with such low profit margins, instead of covering SEA Handling's losses, SEA should have taken much more radical measures to improve SEA Handling's efficiency and substantially reduce personnel costs, which, according to the Italian authorities, represented a significant part of the cost structure of operators in a sector subject to strong competitive pressure. A possible alternative would have been to outsource all or part of the services (different batches) and create a strategic alliance by selling the shareholding in SEA Handling to a strategic partner. Moreover, there was nothing to prevent SEA from trying to improve the efficiency of SEA Handling using more radical restructuring measures within a timeframe acceptable to a private investor, which it failed to do. Private companies' apparent lack of interest in SEA Handling as an investment indicates the company's lack of stable profitability prospects. [4] The calculations did not consider the significant costs that would have been incurred at SEA to cover losses, which could have been avoided by outsourcing part or all of its ground handling activities to a more competitive operator. It is possible that the outsourcing of certain business activities would have resulted in higher costs for SEA in view of the synergies resulting from combining those services with other activities within the organisation. Still, the overall benefit of outsourcing could have been positive. This argument alone does not support SEA's claim in its comments that there was no alternative to covering SEA Handling's losses. (On a personal note, American Airlines itself, for example, tried to achieve what it claimed

- 131/132 -

was cost rationalisation by reducing the amount of olives in each meal during in-flight service by one single olive, which interestingly proved to be an effective form of 'restructuring', yet the company was not an undertaking in serious difficulty.[15]) Some kind of cherry-picking was identified with regard to the outsourcing of all or part of the ground handling activities, as the Italian authorities first argued that the business was not intended to be acquired by any operator. This claim was not supported by concrete evidence, while several operators were authorised to provide services in Italy, particularly at Malpensa and Linate airports.

Third, (un)foreseeable expectations in the business plan were not duly detected and evaluated. Given that for Alitalia, Milan airport is a hub, it is not possible to avoid assessing the situation of the airline, especially in the context of air transport liberalisation. In this respect, the Italian State and the airline have concluded a large number of contracts. However, since it was to be expected that the liberalisation of the sector would eventually lead to a reduction in prices, the Commission did not consider SEA's claim that ticket price reduction was an 'unforeseen adverse event' to be well-founded. The business plan was therefore not based on realistic prospects. Moreover, the Commission considered that a private investor would have anticipated the change in the competitive environment brought about by the liberalisation of the sector and would not have pursued a strategy that made the restoration of profitability dependent primarily on an increase in turnover. This problem has been present since the 1990s, with increasing intensity. Yet, no action was taken to transform the airport until 2012, so not only was the fall in prices very predictable, but also the need to mitigate its consequences must have been obvious. Still, this did not happen during approximately 15 years, which would have been unthinkable for a private investor. The alternatives already mentioned could have remedied the foreseeable and even ongoing negative effects, so this lack of interest and misguided business reaction is also contrary to all the characteristics and rationality attributable to a private investor. A private actor looking at a business that has been loss-making since its establishment years earlier would have demanded thorough scrutiny and concrete action before investing such (or even any) resources in the business.

As a fourth element, anyone can become profitable through external influence. Given that SEA Handling's losses have been covered continuously for more than ten years, it is not surprising that it has finally become profitable again. Any firm that received the same financial support could restore its profitability with modest restructuring measures. However, this prospect would not be satisfactory for a private investor, as it would require at least a forecast that the expected return on the medium-

- 132/133 -

to long-term loss-covering strategy (in the form of dividends, increased shareholder value, avoidance of loss of public image, etc.) would exceed the amount of capital injection to offset losses. A MEI, therefore, would never have acted this way.

Fifth, the duration of the 'support', its objective, and the tendering procedures were all poorly founded. SEA Handling did not face 'temporary difficulties' but serious structural problems, and its losses were not covered by SEA for only a limited period. Moreover, suppose the purpose of the loss cover was to enable the subsidiary to cease its operations under the best possible conditions. In that case, it should have been noted that SEA had only launched two tendering procedures since 2001, and the ideal conditions were not met within a reasonable period. In any case, the objective mentioned does not in itself prove that the measures satisfied the prudent private investor criterion.

As the sixth issue, the ex-post legitimisation regarding the absence of a business plan and quantification was found unacceptable. Italy argued that SEA Handling had claimed that its results had been adversely affected by unforeseen events, particularly the SARS virus, the terrorist threat following the outbreak of the Iraq war in 2003, and the eruption of the Eyjafjallajökull volcano in 2010. The Commission, however, challenged this by saying that the impact of these events on SEA Handling's traffic was only quantified in a study by RBB Economics dated 1 June 2011. However, the study merely reiterated SEA Handling's claims, namely that the terrorist threat following the SARS virus and the outbreak of the Iraq war in 2003 had led to a 3 percent drop in turnover, while the eruption of the Eyjafjallajökull volcano had led to a loss of EUR 1.5 million. The analysis of the situation without the granted aid was based on these assumptions and did not provide an opportunity to analyse the impact of these events in their reality. Moreover, the Commission considered that, even if SEA's unsubstantiated estimates could be considered reliable, the effects of the unforeseen events described in the RBB Economics study would not have realistically justified SEA's serial capital injections, which amounted to almost EUR 360 million from 2002 to 2010. The Commission also considered that an investor operating under market conditions would probably have carried out an investigation immediately after such events, rather than after several years, in order to assess their impact and to determine whether to modify its strategy, adapt its existing strategy, or change its business plan. However, since the RBB Economics study was carried out years after the decision to initiate the procedure, the Commission considered that it did not correspond to the behaviour of a prudent private investor but was carried out for the purposes of the present procedure to demonstrate ex post the alleged economic rationality of SEA's behaviour. Consequently, the study could not be taken into account when applying the MEIP test.

Finally, a comparison with the profitability of other operators would have been essential. The Commission rejected the argument that it was not possible to compare

- 133/134 -

the economic performance of other ground handling operators of a different nature. The Italian authorities refer to 'airport operators with accounting separation', 'airport operators with separate companies', 'airlines providing their own ground handling services' and 'external service providers', which may be both domestic and international network operators, or even SMEs. Thus, they were trying to artificially twist the details about the market as if there were no comparable companies. The operators with which the Italian authorities did not wish to compare SEA Handling are nevertheless actual or potential competitors. In fact, the Italian authorities' argument reduced to zero the number of competitors comparable to SEA Handling, since no single operator provided all the services that SEA Handling did at that time, even if that operator was identical, i.e., a company linked to an airport operator but operating as a separate company. The fact that other operators on the ground handling market may have suffered losses during the same period did not prove that SEA's behaviour was reasonable, but rather suggested the opposite, since an undertaking in economic difficulty tends to concentrate on its core activities and usually ceases investing in activities which generate structural losses or are less profitable, generating alternative costs. Accordingly, the procedure was not in line with the potential behaviour of an MEI.

III. MEIP in practice: The Klagenfurt Airport case

Another insightful example of the MEIP test is the Ryanair-Klagenfurt[16] case. Klagenfurt Airport was majority state-owned (in varying forms) and the aid granted to it consisted - on the one hand - of granting Ryanair all operating costs at a fixed price, i.e. for five plus five years in advance, without taking into account that the fees of other companies were subject to increase year by year in line with market prices. On the other hand, they also entrusted the airline with the operation of the London route, which was a high-profit one for Ryanair, and the prices were also fixed, so that six years later the company would been able to work at a lower price due to the increase in competition and the rise of low-cost airlines in general. Possession of the London route also automatically gave the airline better slots, so it could operate its other flights at a better time and price. Klagenfurt Airport did not have such a contract with other airlines, so their fares were significantly higher, and they did not operate routes under individual obligations. In the case of Ryanair, the conditions pertained to the London route, the demand for which was artificially created, while load factors remained abnormally low. Austria argued that it was not responsible for the activities of the municipality of Klagenfurt, which owned 80% of the airport. The other 20% was held by a federal ministry. This argument was, of course, immediately rejected by the CJEU. In

- 134/135 -

particular, the acquisition of such a large share of the municipality's property required the consent of the federal government, which was granted, but even without it, Austria was to be held responsible, owing to the municipality's public nature, the CJEU pointed out, which is rather an issue of imputability and state resources. The Commission ran an MEIP test, which the CJEU agreed with: the conclusion of the contracts was not based on any impact studies, and Austria could not provide a single document showing that they had examined the competitors or the 10-year returns, or even the one-year returns. In other words, the contracts were simply concluded, probably based on some kind of backroom deal, running to about 15 pages long. Both grants were declared incompatible by the Commission, and the full amounts were ordered to be recovered, EUR 2.2 million. The Commission looked at the revenue generated each year, deducted the associated costs, and then deducted what would have been the real market price in that year based on expert assessment. The remaining amount was considered to be the prohibited state aid element. This case clearly proved that not only is financial capital relevant, but airline slots also have a financial value, which, if granted to one operator without justification (be it economic or legal), constitutes state aid.

IV. The MEIP test generally

Strictly speaking, there is no other way for a Member State to subsidise an undertaking apart from in line with certain titles and legal bases, as mentioned above. If the Member State still wishes to provide money to undertakings with no regard to these titles, it can only do so in line with the MEO/MEIP terms, and then we are no longer talking about granting aid or subsidising, but about providing financing, just like a market operator would, lacking any aid elements.

However, I consider several other important and widely applied methods to fall within the scope of MEO/MEIP-compliant financing, as recognized and supported in the Notice on the notion of State aid.[17] Paragraph 4.2. designates the so-called 'MEO test' as the main justification for financing, while Paragraph 4.2.3.2 describes a sub-method for establishing whether a transaction is in line with market conditions based on 'benchmarking or other assessment methods'. That being said, we immediately face a non-exhaustive list made by the Commission, leaving the door open to any suitable and reasonable methods feasible for corroborating the market-economy-conforming character of a deal.

- 135/136 -

In the meantime, we have to differentiate between the applicability of the MEIP test and actually applying it. As explained - inter alia - in the Larko case,[18] applicability means whether, in theory, the State could act as a private investor in the existing situation. Application, however, means actual evidence that the State acted as a private investor. It is for the Commission to examine the applicability of the MEIP, while the onus is on the Member State concerned to prove that it has, in fact, been applied. Consequently, if it is established that the private investor test is applicable, it is for the Commission to request the Member State concerned to provide all relevant information to enable it to establish whether the conditions for the application of the test are fulfilled.

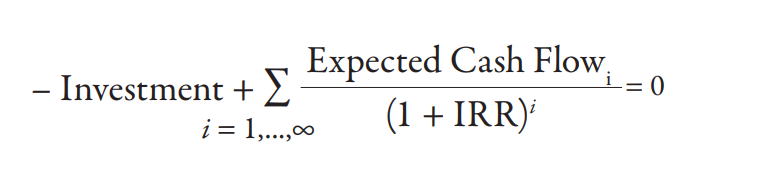

All in all, in general, we may say that the economic behaviour of the state under normal market conditions should be compared to the actions of a prudent and diligent private investor[19] whose moves are reasonable: i.e., if the expected return on the investment exceeds its opportunity cost, which is the return that the investor would expect to obtain from other investments of comparable risk (and at least the return that it could obtain with the same financial risk on the financial market, which is the forward-looking return[20]). Return on investment is often calculated as an accounting return, where earnings are divided by the book value of capital (ROE), assets (ROA), or investment (ROI). However, these accounting rates of return are not usually considered the most adequate measures of the average return expected by an MEI. Market investors may use these methods for smaller and more manageable investments using data from management. However, the calculation of accounting profits is carried out on an annual basis, and a reasonable investor would take into account the project's entire lifespan. The most effective method of determining the average annual return on an investment is the IRR (internal rate of return). The IRR is not based on incomes for a given year but considers the future cash flow stream the investor expects throughout the project's lifespan. Based on the future cash flow, the IRR can be calculated using the following equation:[21]

- 136/137 -

The most important part of the IRR calculation is the correct estimation of the cash flow. In the case of capital investments, this means developing a realistic and detailed business plan. The revenues in the business plan should then be converted into cash flow figures, taking into account non-cash elements, such as depreciation or changes in working capital. Of course, the expected IRR of a capital investment could be over-optimistic or too pessimistic, as business plans can have a major impact on the expected return on an investment. Therefore, it is very important that the basic assumptions used in the forecasting process are realistic.[22] And this, in my mind, is the core of the behaviour of a market economy operator.

V. Conclusion

The MEOP/MEIP test varies by field, as there is a certain difference between the proximity of an investor and a guarantor in relation to the matter of their financing activity, as the status of an investor suggests and necessitates a closer and more imminent interest regarding the actual financing of a project. Therefore, specifying a definitive framework for implementing this test in every financing situation remains very challenging. To address this tangible difficulty, the Commission has adopted several soft law instruments to help financiers comply with less complicated criteria so they are able to provide financing through state aid freely, which I intend to introduce in future volumes. ■

NOTES

[1] C. Quigley, European State Aid Law and Policy (Third Edition, Hart Publishing, Oxford and Portland, Oregon, 2015) 153.

[2] Alfa Romeo case C-305/89 (para 17).

[3] https://www.investopedia.com/news/apple-now-bigger-these-5-things/ (last accessed: 31.12.2024.).

[4] https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/sdg_08_10/default/table?lang=en (last accessed: 31.12.2024.).

[5] https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/NAMA_10_GDP/default/table?lang=en&category=na10.nama10.nama_10_ma (last accessed: 31.12.2024.).

[7] Spain v Commission case, C-278/92 (Hytasa Case), Opinion of Advocate General Jacobs delivered on 23 March 1994 (para 28).

[8] SFEI v La Poste case, C-39/92 (para 60).

[9] Cityflyer Express v Commission case, T-16/96 (para 51).

[10] Land Burgenland v Commission case, T-268/08 (para 48).

[11] Autostrada Wielkopolska v European Commission Case, T-778/17 and P. Nicolaides, First Case of a "Private Debtor" Test? State Aid Uncovered Blog, Lexxion, (14 December 2021), https://www.lexxion.eu/stateaidpost/first-case-of-a-private-debtor-test/ (last accessed: 31.12.2024.).

[12] EC 9-1984.

[13] Milan Airport case, 2015/1225 and C-160/19/P.

[14] Carpatair v Commission case, Case T-522/20.

[15] https://www.aircraftinteriorsinternational.com/quiz/american-airlines-famously-saved-us40000-year-removing-one-olive-salad-first-class-much-money-northwest-airlines-reportedly-save-1987-cutting-limes-16-pieces.html (last accessed: 31.12.2024.).

[16] T-448/18 ECLI:EU:T:2021:626.

[17] 2016/C 262/01.

[18] Larko case, C-244/18 P and T-423/14.

[19] Larko case, C-244/18 P and T-423/14 (para 30).

[20] H. W. Friederiszick and M. Tröge, Applying the Market Economy Investor Principle to State Owned Companies - Lessons Learned from the German Landesbanken Cases, (2006) (1) Competition Policy Newsletter, 107

[21] Friederiszick and Tröge, Applying the Market Economy Investor Principle to State Owned Companies, 106.

[22] Staviczky P., A piaci magánbefektető elve az uniós joggyakorlat tükrében, (2012) 13 (1) Állami Támogatások Joga, (3-19., 9-10).

Lábjegyzetek:

[1] The Author is EU Lawyer at MFB Hungarian Development Bank, PhD student and external lecturer at ELTE Law, Department of Private International Law and European Economic Law.