Csanád Antal[1]: Legal transplantation in India? (JURA, 2009/2., 185-190. o.)

Introduction

One would suspect, that after so many conquests, such a long colonization period, and foreign rule, that really changed the "face" of the present state, affected the supposed ancient law of India that much, that we can't regard the present system to be really "indian".

According to Alan Watson, the "father" of the theory of legal transplantation, if any legal regulation exested once, we can be sure, that it has longlife effects on subsequent legislations.

"A pattern is already begining to emerge: law lives on long after the death of the law maker, and in territories distant from his place of business. And it continues to thrive even in very different circumstances and even though misapplied.[1]"

The next question is: what kind of law could be the "basic" law of the sub-continent? Emperor Ius-tinianus divides the law into two main parts: "ius civile" and "ius gentium". This system supposes, that inspite of the obvious differences between different laws of different territories (ius civile -composed by the nations for themselves) there should be a similarly dominant part (ius gentium - here "composition" not mentioned) according to that all are living[2].

In this article I will try to find the second one, by short analization of some legal customs, ancient and modern legal terms, and ancient principles of the hindu law.

1. Modern or traditional?

The answere seems to be very easy: "a kind of mixture". But more detailed, I give some examples of the impact of the so called "traditional" hindu law on modern provisions:

The law of marriage is regulated according to the main religions of the country: even the "special marriages act" - that came into force during the en-lish rule - regulates the civil marriage as a marriage of spouses of different religion (containing cases of lack of any religious beliefs), though without any religious requirements. What more, any objections based on cast, religion, or tradition is prohibited. A marriage officer is needed for the compulsory registration even at the lowest level of state offices, the "panchayat".

The age requirements are following the pattern of the hindu marriage to the next type, the hindu one: 21 for the male and 18 for the female. Some additional requirements are: neither party can be lunatic, and ceremony (most important part is 7 steps around the sacred fire) according to the customary rites - varying from place to place. During the cool season it is a "attraction" of many cities and villages.

For muslim people marriage is characterised as a civil contract for the procreation of children, that is performed by a proposal and acceptance, and registration is also not compulsory.

The most different provisions are ruling the parsi marriage: minority and insanity are not a bar to the marriage!

Old custom prescribes for the family of the bridegroom - belonging to either religion - to give dowry as a consideration of the marriage. More than 1000 years ago there was legislation on the protection of dowry as a property of the wife; the husband was described just as the custodian[3]. Since this legal protection wasn't enough sufficient for the wife, now "total" ban came into force: "giving, abetting, accepting a dowry transaction is punishable with imprisonment"

But what is dowry defined to be? "...given by anyone before or after a marriage as a consideration..." - so the real effect of the prohibition is diluted by the later, because given "not as a consideration" is regarded to be lawful...[4]

But no need for worrying, because there is another way of protection of women's property and life: the Indian Penal Code contains it, under section 498/A, known as "dowry death": "If a woman commits suicide within 7 years after wedding and there is an allegation that she was subject to cruelty, there is a presumption against the husband and his

- 185/186 -

relatives."[5] The custom should be still vigorous, if such a provision is needed.

Now, a few lines about social legislation: Retirement has 3 financial basis, out of these one is the socalled "provident fund". The employee and the employer contributes to it equally. Generally it makes 8.33% of the wage.

But in certain cases the employee can withdraw from the fund certan % of his contribution in case of "urgent need". E.g.: damage due to natural calamities, illness, daughter's marriage[6]! - not son's marriage!

So, if we think over the abovementioned, on one hand dowry is prohibited, proving the modernity of India's law. Describing the title of the gift is a compromise ("not as consideration") making possible the custom to survive. And both provision are protected by criminal law, because women can't be subject of cruelty on the basis of not providing dowry, or because of not making the received sum available to her husband.

Still, the legislation regrets, that legal provisions can remain insufficient against customs, so the bridegrooms family must also be protected, by describing the daughter's marriage like "natural calamity". I think, we can agree, that this solution is very smart, and wise at the same time.

2. The Smriti of Manu

In the latest chapter I mentioned an ancient legislation forming a whole code, called the "Smriti of Manu". Manu was (were?) an emperor - like Hamurabbi from the legal point of view-, Smriti means usage, collection of usage, actually legal customs. The structure of this code is a bit different from the later "classical" codes achieved in the XIX. th century:

- although it differenciates between civil-, penal-or other branches of law,

- mainly describes duties of different types of people (like the wife, the husband, the judges, the emperor etc.) and is not based on fundamental rights - however it does not put on emphasys on caste system,[7]

- contains both material and procedural law,

- it describes the order of the world, and the purpose of the life.[8]

It establishes a kind of legal hierarchy, by rendering itself under the controll of religious provision contained in the Vedas, - sacred (and innumerous) scripts of the hindu religion (dharma)

According to it, on one hand the religious provisions are acting like legal principles, general clauses in modern law, they are guidelines for interpretation[9].

On the other hand Vedas are like the modern constitutions, because provisions contrary to the spirit of Dharma are invalid, and not to be applied!

Contrary to muslim religion -that was the religion of the mogul emperors rule at the time of english colonilyzation- law was regarded to be changable in that part created by the emperor. That caused a misunderstanding for the english, didn't knowing about the difference between "dharma" and "vidhi".

There is another similarity to roman law: many legal provisions and institutions are very much the same:

Smriti:

- "a gift or sale made by anyone other than its owner is null and void"[11]

Roman:

- "nemo plus iuris ad alium transferre potest quam ipse haberet"[12]

quae res si quidem dominus fuit venditor facit et emptorem dominium, si non fuit tantum evictionis nomine venditorem obligat[13]

"usucapio"

Smriti:

- "whatever chattel an owner, not being a minor or an idiot, sees being enjoyed by another during a period of ten years without taking any objection, is lost in law to the owner"[14]

Roman:

- requirements of usucapio: res habilis, titulus, fides, possessio, tempus

- these requirements were changing from time to time, "bona fides" was not constantly taken into account before Hadrianus, unlike "iusta causa"[15]

Invalidity of cotracts: Smriti: "a fraudulent mortgage or sale, gift or acceptance and any transaction where the fraud is detected, shall be null and void.

What is given by force, what is enjoyed by force, and what has been caused to be written by force, and all other transactions brought aboutby force, are invalid.

A contract entered into by a person who is insane, intoxicated or suffering from disease, or by infant or by very old man or by one, who was not duly authorized, is not valid."[16]

Roman law also recognized these types of invalidity (the last one called "negotium gestum") even more detailed as for the sanctioning.[17]

Liability of the deposit holder: Smriti: "a deposit holder shall not be liable to return or make good the value

- 186/187 -

of deposit in the case of its being stolen or in the event of destruction by water or fire".

Roman: "custodia" liability in case of "vis maior"[18] for the deposit holder[19]

Mortgage: Smriti: "Once a property is given as a mortgage for use, the transaction shall always be regarded as mortgage."

"A property held as mortgage should be returned to the debtor on demand, and deposit should be returned on demand without dely whatever be the length of time lapsed aftert the mortgage or deposit."[20]

Roman: Just the possession of the mortgage is transferred to the creditor.[21]

Smriti: " a person who stands surety for the appearance of a debtor before the court is bound to discharge the debt if he fails to make the debtor appear before the court[22]".

Roman: sponsio/fidepromissio -obliging themselves to give the same that the debtor used to give.[23] Smriti: "Should money be given by a person to another for pious purpose, the gift shall be void if the gift is not used for the purpose for which it was given. If it was only promised and was not given, it need not be given."[24]

Roman: "conditio causa data causa non secuta" has very similar meaning, though not emphasising the "pious purpose"

Warranty: Smriti: "whenever a person after buying or selling feels that he has commited a mistake in buing or selling the article or property in question, he is entitled to get back the money paid or article given on sale, after giving back the article or money received, within 10 days from the date of purchase or sale, as the case may be.[25]"

Roman: similarly the roman law grants petition to one who purchases slave incapable for work.[26]

Treasure Trove: Smriti: "The king is entitled to one-sixth or one twelfth of a treasure trove recovered by a person..."[27]

Roman: the emperor is also entitled for a certain amont of the treasure depending on where the treasure was situated [28]

Sometimes we experience, that humanity exceeds the european standards of that time: Smriti: "the king having fully considered and having the due regard to the motive, the place of occurance, the ability of the offender to suffer the penalty, and the nature of the crime -should impose the penalty which the accused deserves."[29]

3. Probability of connection with roman law

The question is given: how comes, that so much similarities can be found between the roman and the indian law? The first known unification of India was achieved by the Gupta dinasty (around 350.). That time the Smriti was existing, and commentaries were written about it. Before that, for long centuries the northern and middle part of the sub-continent was inhabited by continuosly arriving groups of conquerers of various nomad tribes of Central-Asia. The territory of these empires was usually similar, containing the present Afghanistan, Pakistan, East-Iran, and North-India bordered by the present mem-berstate, Maharashtra. The caste system, formed by the arian conquerers supported a relatively isolated state (or group of states) that was based mainly on agriculture. In the meanwhile, norther from the surrounding mountains of Hindukush, Pamir, and the Himalaya a commercial route was formed ranging from Chinese territories to Europe - acually to the Roman Empire at this period - commonly know as the "silk-road".

This route was controlled from east to west by the following states and empires: the Kushan (the present Mongolia and the Tarim-basin) - known by the chinese as "Yüe-Chi" - the later Indo-Schytians (western side of the Altay-mountains) Khorezm (the Turanian - flatland) Baktria (the present Türkmeni-stan, Afghanistan) and various dynasties of Iran (like Parthus, Sassanida etc.)[30]. Eastern from this "row", the huns were living, who managed to defeat and drive out the kushans from their territory, who - also by defeating the neighbouring empires occupied wast parts of Central-Asia.

This empire was a bridge between the western (greek originated), "indian" (based on arian) sanskritized and central-Asian cultures. Most kushan coins contain two kinds of scripts: greek on one and some brahmi (sanskrit/prakrit) on the other side[31]. Thanks to kushan emperors the buddhism could spread from the indian subcontinent towards Tibet and China: "passing through" the former Baktria (established by Alexander the great) buddha statute's hair became curly, (and the body sometimes really athletic) like greek gods! Inspite of that most coins contain the portrait of Shiva, the hindu god of war, and in the capital of the empire, in Mathura, a Mitra satute was found, that is a persian god of the sun[32], prooving the great variety of religions and believes as well. (Mithras had many followers in the Roman empire as well, for exaple in my city, the former "Sophianae"). Thanks to their irrigation experiences in Khorezm they developed this system in Gujerat (indian member state), and other dry parts of the empire.[33]

The indian historians agree, that the most important deed of the kushan rule was that they connected the indian territories to the silk-road, that enabled developement of industy as well (don't forget about the iron pillar in Delhi, that weights 9 tonns, appr. 1500 years old, and rostfree! Or the unique technic

- 187/188 -

of making bows from steel). The starting point of the silk road's sea division was Barbaricum in Gujerat - also ruled by the kushans (in allience with the indo-schythians). This harbour connected the Kushan and the Roman empire; the first tiger in roman circus was a kushan gift to the emperor Traianus[34].

Commerce - especially the international - developes it's own usages, standards: inside the Roman empire "ius gentium" was a really important component of developement of the whole system of the roman law codificated later by Iustinianus. Many new legal insitutions emerged in the everyday practice of commerce, that later became binding for all.[35] Ruling vast territories of different cultures, nationalities, religions also encouraged the developement of administration system based on law, legal institutions, that resulted the great codes of Iustinianus.

Acording to the abovementioned - although I don't have information about researches improov-ing the nature of legal connections between the two big empires - we can regard it to be possible that travelling goods and ideologies involved some "harmonization" of legal standards.

4. Legal expressions of hindi language

After the experience of similarities of ancient hindu and roman law we should ask the question: In what extent is the ancient hindu law can be regarded to be the ancestor of the present law of India? If it is, there should be a continuity of the language.

The muslim moguls conquest did not changed the whole system of the society (just like in South-East Europe) they upheld the caste-system, and in some periods reconversion was also allowed for the former hindus. (Shah Akhbar)

Still, the muslim Shar (sharya law) as the peronal law of the ruling class - a kind of "highest cast" -suppressed the use of hindu law, because in most cases, where muslim party was also involved in the case, the muslim law was applicable[36], or at least prevalent.

From institutional point of view, the application of hindu law was restricted to the lowest level, called "panchayat"; the first instance court formed by the elders of a village, that also had administrative functions. (Today for example it must contain a marriage officer, who can conduct civil marriage according to the Special Marriages Act.) This continuosly operating "court" became the basement of the english rule's legal sytem: under the administration of the East Indian Company the formed mixed courts were exesting of "pandits" (not exactly legal experts, rather moralists) from the panchayat, and a learned english judge. Through this composition - according to René David - "the english brought out Hindu law of the shadows by officially recognizing it's authority and value, which had not occured during the muslim domination."[37]

Later on they formed the sole judicial system, and composed codes like Indian Code of Civil Procedure 1908., Criminal Code 1860., Code of Criminal Procedure 1860., Succession Act 1925. Evidence Act 1872.[38], Instrument Act 1881[39]. Many of them still in force! As the member of the British Commonwealth, Indian courts can refer to other common-law states precedents.[40] Due to the numerous similarities of system and practice, today's law of India is regarded to be "modified common law"[41].

Such transplantations used to result in the grevi-ous influence of the legel theory. One component is the composition of the same legal terms: sometimes the use of the foreign expressions without changes (like "leasing" in Hungarian law is "lízing"[42]), sometimes the use of translations. It is obvious, when all, or most meanings of the expression is the same in the two languages ("Spiegelübersetzung") - often occuring in Central-European laws as a result of german influence. (e.g: the german term for corporation, the "Gesellschaft mit Beschränkter Haftung"-GmBH was translated to hungarian, though, the meaning doesn't express the content)

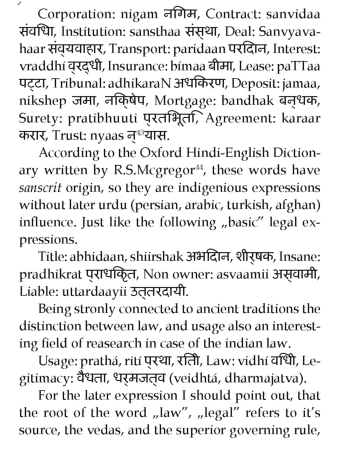

Let's examine some hindi expressions of comerce first.

- 188/189 -

the Dharma, the religion, expressing the clear, and direct connection between them. So that time law and usage were recognized to be different.

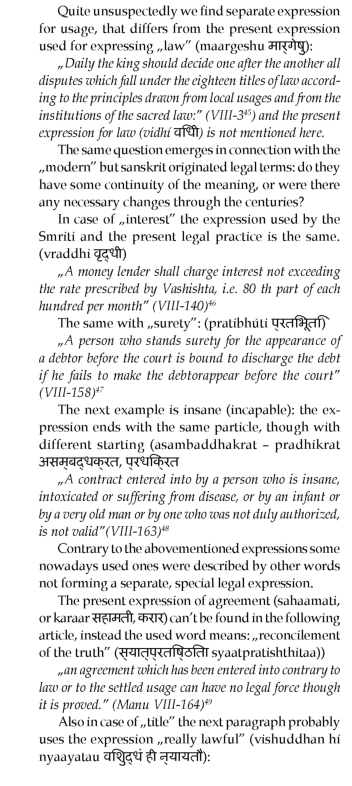

5. The texts of Smriti

As I mentioned before, the "Smriti" has the meaning of collection of usage. It is clear, that the present law makes difference between law, and usage, but how was it 1000 years ago?

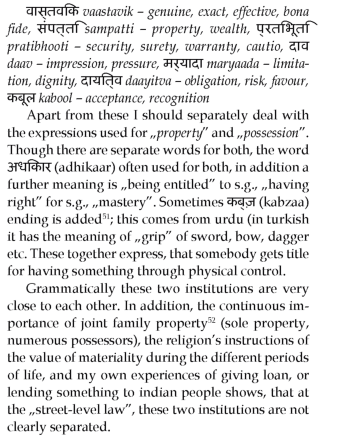

6. Ambiguities

Despite of the abovementioned, most expressions happens to have more meanings, sometimes very confusing for the european - who probably doesn't have the proper knowledge of the language. I give some examples below:

7. Summary

The reception of english-made law started in India from the beginning of the colonization, it was upheld by the Constitution, and still supported by the judi-tial system. Whenever - like in case of the english colonial law in India - a legal reception as a kind of transplantation appears to be succesful, we can suspect some factors enabling the coming into force of the legal provisions other than the fact of mere "con-quest", "ruling", sometimes suppression. Acceptance and daily routine requires something more. Because of the different origin of the muslim and hindu law -

- 189/190 -

though each are regarded to be religion based legal system - the mogul's muslim law couldn't change and supress hindu law that extent that would have made impossible it's later "renessaince" during and after the english rule. The probability of the continuity of hindu legal tradition seems to be obvious. The english legal system is regarded to be free from roman influence, although we can be doubt, that by use of foreign (latin) language one can maintain national law, custom, language, and science. In english law, almost all of the legal institutions mentioned in this study are expressed by latin words.

The empires of sanskrit language could develop their own set of expressions and legal institutions that - according to my opinion - after matching the legal practice of the countries of that time, nowadays still plays an important role in enabling the present law of India be the recipient of "european" ideas of law. The "roman connection" happens to be existing, but the nature of this kind of transplantation is still subject of question.■

NOTES

[1] Alan Watson: Law, reality and Society in http://www.alanwatson.org/law_reality_society.pdf

[2] Institutiones (I. II-1.) in Iustinianus császár Istitutioi négy könyvben translated by: ifj. Mészöly Gedeon, Egyetemi Könyvkereskedés Budapest 1939. page14.

[3] Smriti of Manu (IX-194) in Ancient Indian Law page 33.

[4] Law for the Layman page 93.

[5] Ibid. 94.

[6] Ibid. 77.

[7] Ancient Indian Law p. 125.

[8] Ibid. p. 5.

[9] Smriti (1-v-4) in Anciant Indian Law XII. "Whenever it is found that there is conflict between any provision contained in the Vedas, and the provision in Smriti, Purana custom etc., then what is declared in the Vedas alone shall prevail."

[10] Ancient Indian Law 66.

[11] Smriti (VIII-199) in Ancient Indian Law 60.

[12] Takács György: Ha a jogász latinul beszél, Közgazdasági és Jogi Könyvkiadó, Budapest 1991. p.182.

[13] (Digesta 19.1.11.2.) in Brósz Róbert-Pólay Elemér Római jog, Tankönyvkiadó, Szeged 1974. P. 428.

[14] Smriti(VIII 147-148) in Ancient Indian Law 71.

[15] (Digesta 41.3.13.) in Brósz-Pólay ibid. 245.

[16] Smriti (VIII 165-168) in Ancient Indian Law 67.

[17] Brósz-Pólay 454.

[18] (Digesta 44.7.1.4.) in Brósz-Pólay 353.

[19] (digesta 13.7.8.9.) in Brósz-Pólay 414.

[20] Smriti (VIII-145) in Ancient Indian Law 70.

[21] "pignus nanente proprietate debitoris solam pos-sessionem transfert ad creditorem (Digesta 13.7.) in Brósz -Pólay 363.

[22] Smriti (VIII-158) in Ancient Indian Law 68.

[23] (GAIUS 3.119) in Brósz-Pólay: Római Jog 429.

[24] Smriti (VIII-212) inAncient Indian Law 71.

[25] Smriti (VIII.-222) in Ancient Indian Law 69.

[26] qui inmenta vendunt, palem recte dicunto, quid in quoque eorum morbi vitiique sit... si quid ita factum non erit... morbi autem vitiive causa inemptis faciendis in sex mensibus vel quo minoris cum venirent, fuerint, in anno iudicium dabimus (Digesta 21.1.38.) in Brósz-Pólay 429.

[27] Smriti (VIII-35-39) inAncient Indian Law 99.

[28] (Institutiones 2.1.39.) in Brósz-Pólay 233.

[29] Smriti (VIII-126-128) in Ancient Indian Law 82.

[30] Dr. Aradi Éva: Egy szkíta nép: a kusánok p. 25., 36., 94.

[31] Dr. Aradi Éva: Egy szkíta nép: a kusánok p. 176.

[32] Ibid. 146.

[33] Ibid. 122.

[34] Ibid: 115.

[35] like the titles of aquiringownership Brósz-Pólay Római jog p. 227.

[36] H.V. Shreenivasa Murthy: History of India p. 268., Eastern Book Company, Lucknow 2006

[37] René David - John E.C. Brierly: Major legal systems of the world today p.490. , Stevens & Sons, London 1985

[38] René David: Ibid. p. 506.

[40] Smt. Gian Kaur v. Sate of Punjab refering to Rodriguez v. B.C. Supreme Court of Canada in: Universal's Landmark Judgements, Universal Law Publishing C.O. PVT.LTD. 2008

[41] René David: Major Legal Systems. p. 508, 507.

[42] Hungarian Act of "special duties, fees and taxes"1990. XCIII. 26.§. (10) b.

[43] In roman law "mandatum pecuniae credendae" was a leasing like institution: the mandator could order the creditor to give loan to the debtor. In case of the later didn't pay back, the creditor could seege the mandator for repayment - In: Brósz-Pólay: Római jog p. 359.

[44] R.S. McGregor: The Oxford Hindi-English Dictionary, Oxford Univ. Press 2007

[45] Ancient Indian Law p.73.

[46] ibid. 69.

[47] Ibid 68.

[48] Ibid. 68.

[49] Ibid. 67.

[50] Ancient Indian Law p. 70.

[51] Kamlesh Chopra: English-Hindi Dictionary, Eastern Book Company, Lucknow 2001

Lábjegyzetek:

[1] The Author is a PhD-student.