Robert Atkinson - Stephen Stec: Civil Society Turning - Development of Environmental Civil Society Groups in the West Balkans (IAS, 2009/1., 67-84. o.[1])

Introduction

The development of civil society in Eastern Europe is one of the remarkable phenomena of recent history. Counting from its beginnings in the waning years of one-party rule to today, sufficient time has passed to warrant an assessment of the shape of environmental civil society as it has passed through its teenage years and is on the verge of turning 21.

This is an appropriate topic for a volume honouring Alexandre Kiss. After the events of 1989 Alexandre Kiss's Hungarian citizenship was restored and he began returning to Hungary, organizing summer programmes with Santa Clara and other universities. For the rest of his life he made it a priority to inspire a new generation of young lawyers from countries in transition to see the law as a means for respect for human rights and unleashing human potential for protection of the environment. Many of the young lawyers touched by Alexandre went on to non-government careers, either as key members of civil society organizations agitating for change, or providing critical legal services to build the capacity of NGOs to conduct more effective campaigns.

This article therefore examines in some detail the legal aspects of environmental civil society, including the legal conditions for organization of associations, the framework for operations including economic incentives, and some of the most significant legal tools for participation of Environmental Civil Society Organisations (ECSO's). Drawing upon similar studies done for the region of Central and Eastern Europe, this particular analysis focuses on a nearby region that has emerged from a decade of conflict, but which shares many of the same historical characteristics of the CEE region - that is, South Eastern Europe.

- 67/68 -

Methodology

The background for the findings presented in this paper is the research and analysis the authors, and others, carried out for the Regional Environmental Center for Central and Eastern Europe (REC) in 2006-7 on ECSOs[1] in South Eastern Europe. REC made this extensive survey of the ECSOs of seven South East European countries or territories[2] as a part of a Swedish International Development and Cooperation Agency (Sida) funded aid programme called SECTOR (Supporting Environmental Civil Society Organisations in South Eastern Europe). The surveying was conducted in the period of April - September 2006 and had two main objectives:

. To conduct an in-depth assessment of the nature and status of the environmental civil society organisations in the South East European region, providing in-depth analysis of the challenges and opportunities they face.

. To give specific answers and information for the preparation and planning of other forms of support through the SECTOR programme.

Additionally, information gathered throughout the survey was planned to be used for broad dissemination to all potential stakeholders and people interested in the status and challenges of rapidly developing environmental civil society in the West Balkans region. This paper is one of the ways information on the survey may be disseminated to a wider audience.

The research was focused around five key modules that delimited the effectiveness and efficiency of ECSOs. The five research modules were: (1) Legal and Regulatory Framework, (2) Resource Base, (3) Human and Organisational Capacities, (4) Information and Knowledge and (5) Accountability. All of the modules considered the internal and external environment of ECSOs and each module's key assumptions, research focus and survey questions were elaborated by a dedicated expert or module leader.[3]

The assessment survey of ECSOs was done in three main stages: (i) collection of data from open sources, (ii) distribution of a survey questionnaire to a wide audience

- 68/69 -

of ECSOs (used for collating into a directory as well as the assessment); and (iii) semi-structured personal interviews. Therefore quantitative and qualitative data were collected in the course of the survey.

The survey questionnaire was developed by the research team and widely distributed (in local languages) by the REC's country and field offices to ECSOs between June and July 2006. The questionnaire was divided into two parts: Part A was used for the organisations' entry into the REC's NGO Directory.[4] Part B of the questionnaire was designed for a deeper, confidential assessment of the groups, and that information was not used within each organisation's directory entry.

Supplemental questionnaires were developed for the personal interviews to generate data concentrating on opinions and trends seen by the interviewees. Interviewees were from a variety of stakeholders, including ECSOs, Civil Society support organisations, donors, national and local government officials, and civil society lawyers.

The total number of questionnaires received from organisations was 434 and the number of individuals interviewed was 116[5]. Data from the questionnaires and personal interviews were compared with data from open sources. Although there are certainly many more environmental civil society organizations registered in the region than responded to the questionnaire, the researchers believed that the respondents represented a large proportion of the most active organizations in the region. Indeed the numbers are comparable to those gathered during a previous study carried out by REC in 2001[6] and which have been used below to make some trend analyses.

The data entered were aggregated and analysed in order to assess the status and needs of the environmental movement in SEE. The outputs of the assessment were partly published in the 2006 SEE NGO Directory with national chapters, plus a brochure called Striving for Sustainability that presents a summary of the results, findings and recommendations.[7] Additionally the findings and recommendations were presented at the 6th Environment for Europe Conference (Belgrade, October 2007) and a European Commission conference on the Commission's new Civil Society Development Facility (Brussels, April 2008). Due to funding and other limitations, however, the referenced publications could present only a partial picture of the results of the research.

- 69/70 -

General Findings

The findings of the survey and interviews showed that many and varied issues face SEE ECSOs. Naturally the region has developed differentially - within countries there are local differences - however, it is possible and valuable to give a general regional summary of the ECSOs' situation and the trends in their development. The legal aspects of civil society development in SEE are the prime topic of this paper, in a section that follows. Nevertheless it is useful to provide context by setting out some of the general findings and recommendations.

When we plot the year of founding of the ECSOs in SEE and CEE[8] against the absolute number of groups founded in that year we get the following graph:

In comparison with CEE there were quite low levels of ECSO foundation in SEE in the early to mid 1990's. This was obviously due to the years of conflict and civil strife in the region. However since 2000 the patterns are fairly similar. This demonstrates that in SEE the majority of ECSOs are young groups, which may imply something about their experience and abilities. It may also mean that society in general is less familiar with the concept of civil groups and their role in society. As the title of this paper is Civil Society Turns 21 we see in reality that practically many of the civil society groups in SEE are still in their infancy.

- 70/71 -

The survey examined the groups' responses as to whether their activities involved any from a list of 26 possible topics. It was found that the more political, or perhaps technical issues feature in the lower half of those most commonly worked on.[9] Topics like nuclear power, GMOs, climate change, or transport[10] are clearly less popular among the ECSOs. This finding in itself is important, but takes on even more significance when correlated with the organizations' capacities and the sources of funding that particular ECSOs have access to for their activities. This in turn helps us to understand whether the programming priorities of donors tend to lead organisations to work into fields that would normally not be their own highest priority. Moreover, from the point of view of building capacities of these ECSOs, the findings of the assessment pointed to the need for an increase in their knowledge on a specific range of issues.

| Most common topic | 2001 | 2006 |

| 1st | Nature protection | Environmental education/ESD |

| 2nd | Environmental Education | Nature protection |

| 3rd | Public Participation | Sustainable development |

| 4th | Biodiversity preservation | Waste |

| 5th | Tourism/Eco-Tourism | Water |

The assessment considered the sources of funds for the environmental movement in the region. The five most frequent sources of funds (regardless of amount) were found to be:

1. Foreign/international foundation grants - 52%.

2. Domestic government grants - 52%.

3. Membership dues (fees) - 44%.

4. Foreign government/international grants - 36%.

6. Domestic corporate/business grants - 34%

However, if we compare this list with those donors that ECSOs characterise as primary funders (more than 25% of their budget coming from that donor) the picture changes:

1. Foreign/international foundation grants - 23%

2. Domestic government/public sector grants or donations - 15%

3. Foreign government/international grants - 14%

Notably, membership fees, while relatively common, only appear in tenth place as a significant source of funding. In addition, the results show that there are relatively

- 71/72 -

fewer dependable, nationally based funds available for ECSOs in SEE - funds that these organisations could perhaps influence. The overall conclusion is that the financial situation of ECSOs is bound to worsen as foreign donors phase out. The survey also showed that SEE ECSOs are more dependent on fewer donors. On average a SEE ECSO receives funding from 3.5 donors, as compared to 5.0 average donors in CEE. This lack of diversity of funding is a further vulnerability and source of insecurity, which also has the effect of making SEE ECSOs more responsive to donor priorities.

In addition to sources of funding the survey also asked the groups about the sizes of their budgets (using eight categories, starting at zero to over one hundred thousand Euros per year). The following graph plots the number of ECSOs in each category against the sum of their combined budgets (using the median point in each category as an estimate).

The chart shows that there is a distinct "class" of wealthier groups that has accumulated a large proportion of the available resources, a sizable 'middle class' of groups, but also a quite large group with very limited or no financial resources at all. In comparison with the data from the 2001 survey the distinctions among these classes have been exacerbated.

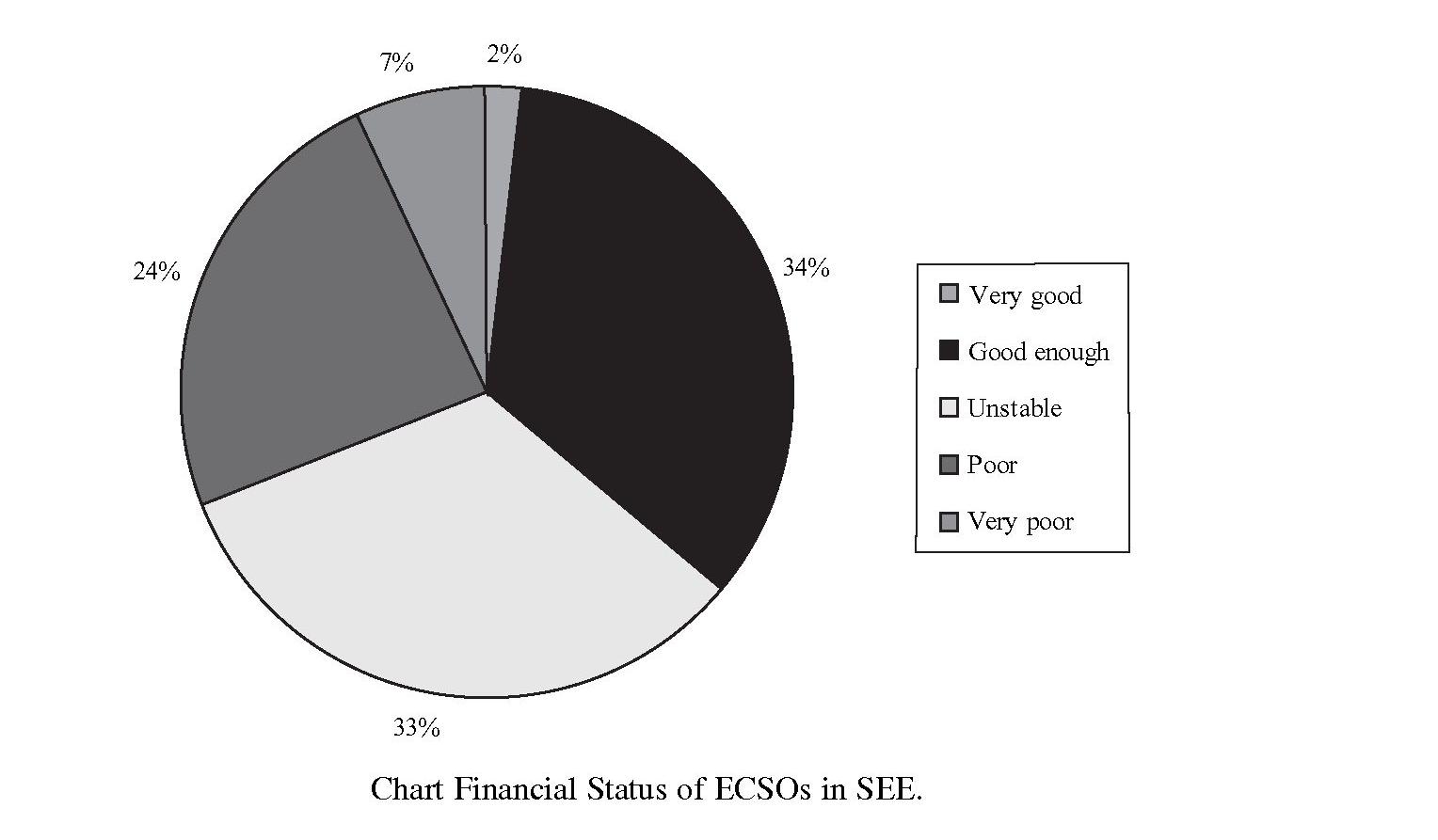

The following pie chart reinforces these findings. When asked about their financial status, two-thirds of all ECSOs in SEE stated that they are financially unstable or worse. This is a sobering analysis and goes some way to define the resource stresses that ECSOs in the Balkans are under. Certainly there is some concern for how viable they are as organisations and in being effective in fulfilling their role.

- 72/73 -

The survey findings paint a picture of the 'average Balkan ECSO' that can be summarised thus:

. formed after 2000;

. with a 17 000 EUR annual budget;

. rents its office;

. covers environmental education, nature conservation & waste issues;

. has to adapt to donor priorities; and

. struggles to define its fundraising strategy and to support its two paid staff.

Relating to the trends exhibited by the movement there are a number of headline findings that raise concerns over the future direction of the development of civil society groups. There is an evident and growing disparity between different types of ECSOs (the haves-and-have-not's), both in financial resources and capacities. The funding environment is becoming increasingly difficult for 'grassroots' organizations, particularly those that rely on membership fees and therefore may be better connected to the local community.

In general there appears to be less capability among Balkan ECSOs on politicised or campaign issues (GMOs, climate change, et. al.) than is required for the increasingly complex environmental agenda. However, a 'professional class' of ECSOs that are addressing these policy issues is developing, but such groups may be criticized for having a questionable connection or relevance to the community. Some view them as important ECSO think-tanks while others view them as opportunistic crypto-consultancies using CSO funds for profit-making. Additionally donors are criticized for pushing their own agendas without considering the needs of ECSOs. Some interviewees even consider that donors use ECSOs as vectors for their own positions and questioned whether the priorities chosen reflect those of the local civil society.

The question now is: how will SEE ECSOs develop further from this point? It could be assumed that as the countries of SEE are looking towards EU integration,

- 73/74 -

and will come under the influence of those processes, much of this development may follow the pattern exhibited in the new Member States or CEE. Based on the findings of a similar survey in the CEE region[11] it was found that those CEE ECSOs with higher incomes and more paid staff (the 'professional class') tend to get primary funding (more than 50% of their budget) from EU institutional sources, yet have lower levels of members. At the same time, those with lower levels of income and fewer paid staff tended to have primary funding from membership fees (dues) - and higher levels of membership - yet also tended to have lower staff capacity and overall funding levels.

Additionally it was also found that these two groups are inclined to concentrate on different forms of activity - respectively policy advocacy and direct actions. Consequently, CEE ECSOs doing direct action have comparatively few resources while EU institution-supported ECSOs appear to represent a smaller but wealthier set of organisations. An analysis of trends, moreover, shows a clear tendency for the 'professional' ECSOs to capture a greater proportion of overall funding. This can contribute to an "insider" culture that is difficult for new organizations to break into. One of the methods used by such organizations to maintain their funding is to follow donor priorities. As donor priorities have shown a tendency in recent years to become concentrated on a narrower set of fields this phenomenon has the effect of focusing 'professional' ECSO priorities towards those of the donors.

The pattern in CEE appears to be a further evolution of what is now being exhibited in SEE. Perhaps this is a natural process of ECSO evolution. Certainly the diversity of types of groups is necessary and while many persons have an understanding of "true" civil society organizations limited only to the grassroots variety, no picture of the development of civil society in CEE and SEE is complete without an understanding of the role and characteristics of the 'professional' public organizations. Still we need to consider what we foresee as the 'best' role and function of civil society organizations on environmental issues, and thus consider what the movement needs to develop to fulfill them. Donors especially need to judge the effect of their funding on the movement in the long-run and would perhaps be better off in focusing on the infrastructure of the CSO arena as opposed to supporting projects along their own narrow aims.

Legal Findings and Analysis

These have been the main findings of the survey. Now we may present in greater detail the main legal aspects of the study, and some general observations about legal tools. In the field of Legal and Regulatory Framework the survey looked at several aspects of legal regimes relevant to civil society organizations, covering legislation as well as its implementation. These included the basic legal foundation for the

- 74/75 -

establishment of civil society organizations, including systems for registration, the use of tax regimes to encourage civil society activity, and the rules of the legal profession that affect the ability of ECSO lawyers to engage in advocacy. As in the other parts of the survey, both the actual state of the law and the perceptions of the various stakeholders were examined. Thus, the survey also gathered information concerning the extent to which ECSOs consider complying with legal requirements a priority, thereby indirectly providing information on overall enforcement of the law. As one element of the SECTOR project was to identify training needs, legal training was included as one of the areas surveyed.

Finally, the project examined the legal frameworks in the countries and territories for access to information and participation, and gathered information from ECSOs about the frequency with which they make use of such legal provisions. Raw data about the number of cases brought to court was also gathered. The main findings in these areas are presented in the following section.

Legal and regulatory framework

Registration Issues

Often the first thing an NGO has to do is to register, and this process is still in many countries time-consuming, bureaucratic and expensive. Some countries employ a two-step process with tax registration separate, and for some NGOs outside of capital cities they have to register once locally and once with different authorities in the capitals. The use of computerized databases accessible online or in local communities would help solve this problem.

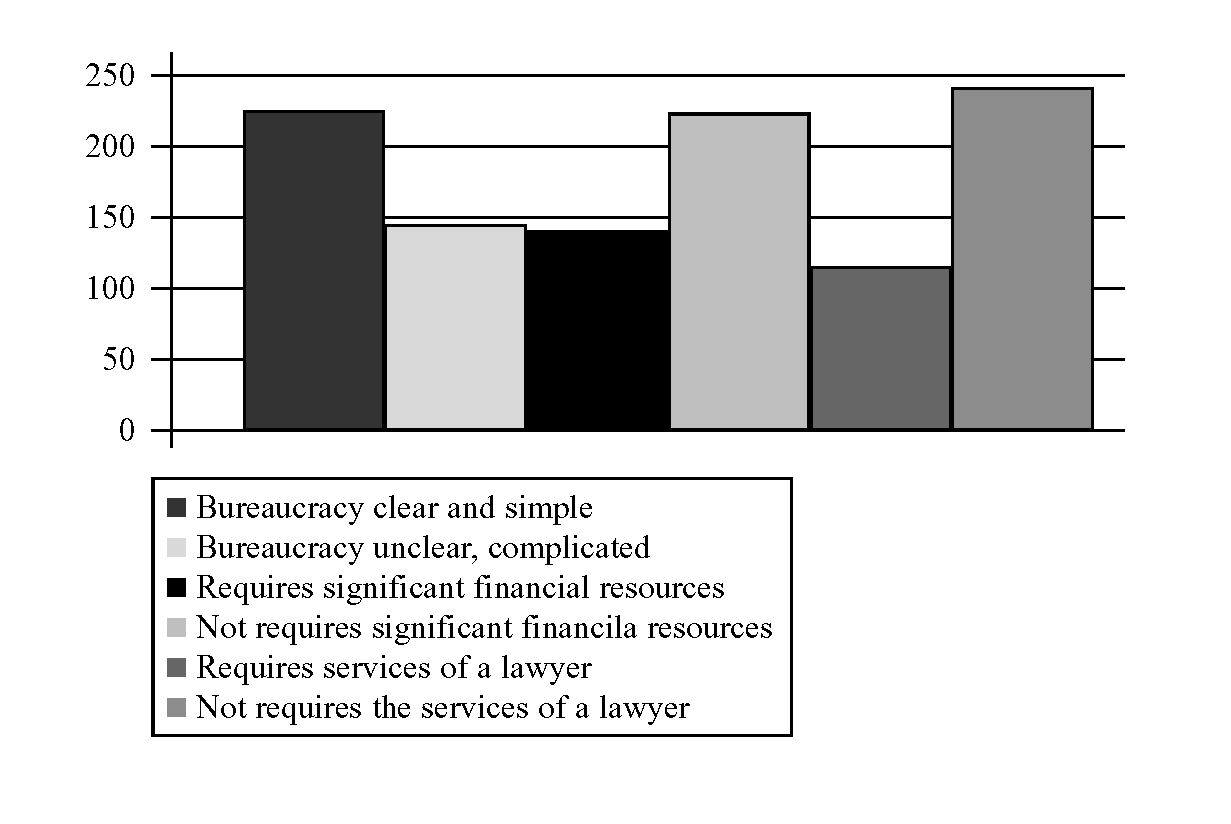

Complexity of registration procedure

The survey found that in most places the situation for registration of a CSO is fairly simple, straightforward and inexpensive (notably Kosovo, Macedonia, Montenegro, and Serbia).[12] However, in all countries there are some specific issues associated with registration:

> In Albania the state of CSO registration law is partly in flux, especially with regard to tax and financial matters. ECSOs in the regions are particularly affected by the two-stage registration process, which may require several trips to various authorities to complete.

> The legal framework in BiH for registration is good, but administrative practice is problematic. A multiplicity of authorities and jurisdictions creates obstacles for smooth operations of ECSOs throughout the country.

> The legal framework for registration in Croatia is likely the best in the region. But excessive legal requirements prevent the establishment of foundations.

> In Macedonia the legal framework for registration is good, but procedures can be time-consuming.

> The process of registration in Montenegro is simple, straightforward and inexpensive, and CSO status offers significant tax advantages. But, there is a high rate of abuse of CSO registration possibilities by for-profit companies.

> In Serbia registration has been relatively simple up to now.

Legal Compliance

A series of questions, particularly in the interviews, addressed the extent to which the legal framework related to the operation of ECSOs, including the particulars of an organization's statute or registration, is taken seriously. In several of the countries the survey revealed that overall lax enforcement of legal provisions leads to possibilities for ECSOs to operate without full legal compliance or without due regard for particular legal requirements, in particular those related to governance and financial reporting. Of note in this regard were: Albania, Kosovo, FYR Macedonia, and Montenegro. In contrast, Croatian ECSOs generally operate consistent with their legal status and legal requirements.

Tax Issues

Tax incentives or tax exemptions are in use in many CEE and even SEE countries, with a broad range of tools being used, some rather experimental. The tax regime affecting ECSOs varies markedly from country to country, with the most favourable regime in Albania and the least favourable in Serbia. For Bosnia and Herzegovina the tax structure is not fully developed and differs across jurisdictions. In both Croatia and FYR Macedonia, ECSOs generally do not benefit from tax advantages, and have the same tax treatment as for-profit companies.

- 76/77 -

Percentage of NGOs for the different tax exemptions

Key:

1: Income taxes for grants, donations 2: Income taxes on generated fees 3: Employment taxes 4: VAT 5: Other

Q 5: Are donations to your organization tax deductible?

However, as can be seen by the chart above, there appears to be some confusion among ECSOs as to whether tax deductions for donations are available. For a large group of ECSOs, this is due to the fact that donations are not a source of funding.

More experience sharing is needed to see what tax mechanisms work and which do not within the region. In some countries certain preferences are granted to "patriotic" or other groups. Abuse of tax benefits through sham NGOs that are involved in many kinds of shady enterprises is one of the biggest challenges in the region, and undermines the credibility of legitimate NGOs. Public opinion surveys in some countries outside

- 77/78 -

of SEE have shown that the public believes NGOs to be mechanisms for smuggling, tax avoidance and other forms of criminality. This has not been specifically tested in SEE but many of the same social conditions are present there.

Legal Advocacy and General Standards of Justice

In many of the countries general legal frameworks to enable advocacy are in place, but implementation and enforcement are lacking. Consequently genuine legal advocacy has not developed and there is a general lack of sense of ownership of the legal regime. Croatia's legal system was not seen to be very favourable to genuine legal advocacy, but conversely there is a higher rate of the use of this tool than in other parts of the region.

Official corruption is still a problem. One typical example arose out of the interviews. Some countries require - at least informally - the use of specific lawyers for NGO registration who work in cahoots with judges to extort extra fees, but the problem goes far beyond such examples and is endemic. The problem of corruption obviously has an impact on whether ECSOs use legal or other means for their purposes. In the EU member states with one or two notable exceptions this problem has been managed, but it is a big problem elsewhere.

The survey also revealed deficiencies in the training of authorities and judges to ensure a standard interpretation of the law and of justice. Different interpretations of requirements and of the law itself depending upon the official are reported to be still common. It is obvious that training is not keeping pace with legal reform. The inability to predict the outcome of legal actions contributes to a general reluctance to make use of the justice system.

In CEE because of the overall stabilization of society and the legal system, the strategic use of litigation has taken hold, but despite assistance efforts, in SEE most ECSOs do not seriously consider the use of legal cases to further their goals. This is due partly to ineffectiveness of justice systems and partly to the existence of other avenues for success. While Aarhus Convention tools, e.g., have been used to great effect in some countries, in others the level of inefficiency of the system makes this only a dream.

Nevertheless, there is general awareness in the region that legal mechanisms, and by implication an improved legal system, have the potential to provide important opportunities for ECSOs to meet their goals. In around half of the countries (Albania, Bosnia & Herzegovina and Croatia), legal assistance, training and expertise are relatively important needs identified by the ECSOs themselves.

Use of legal tools - Access to Information

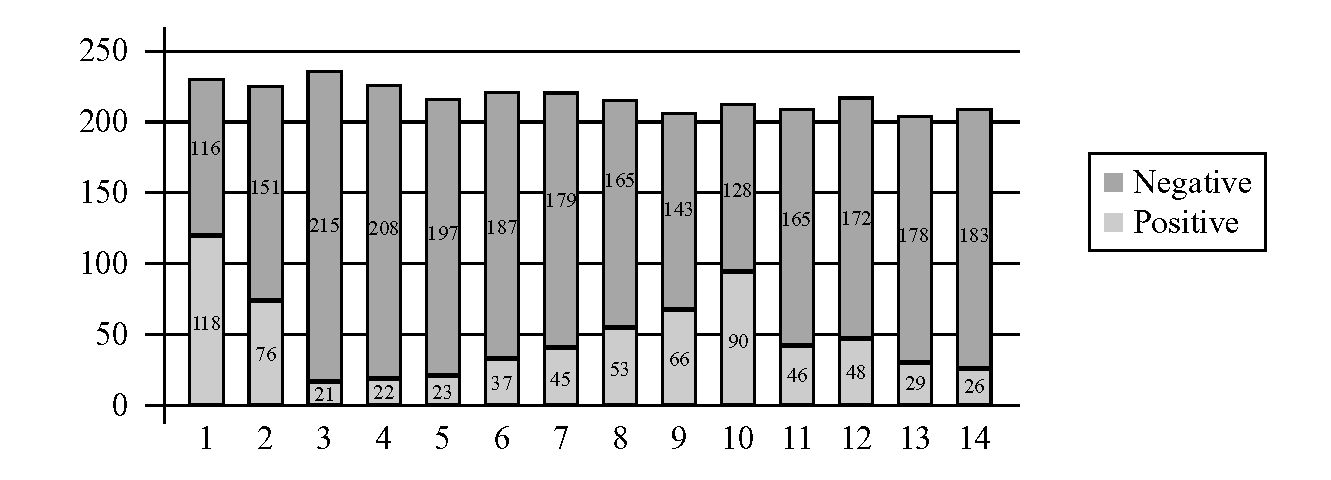

The research team also investigated the perceptions of ECSOs and other stakeholders concerning the effectiveness of a range of available legal tools. The information gathered included whether the ECSOs had positive or negative experiences or impressions related to the use of the specific tools. For example, the following chart shows the number of respondents characterizing different aspects of the use of the law

- 78/79 -

on access to information as positive or negative. Even where the legislation is largely considered in a positive light (as shown by the first column), procedures are viewed less positively and the level of enforcement shows significant problems, contributing to overall negative scores. Only the cost of receiving information is viewed in a generally positive light. Common problems identified included failure to answer information requests, late response, lack of capacity of authorities to handle requests, poor information flow between authorities, and under-developed infrastructure for electronic information.

The snapshot below should be considered in light of the responses in a number of countries stating that access to information has improved in recent years.

Key:

1: Legislation regarding rights and responsibilities 2: Procedures and rules 3: Legislation enforcement

4: Knowledge about what rights citizens and CSOs have 5: Knowledge and skills about how to use rights 6: Timeframe to receive the information 7: Handling confidentiality of information 8: Costs for receiving the information

9: Information on where and how the information can be accessed 10: How up-to-dat is the information 11: Format of the information 12: Amount of information

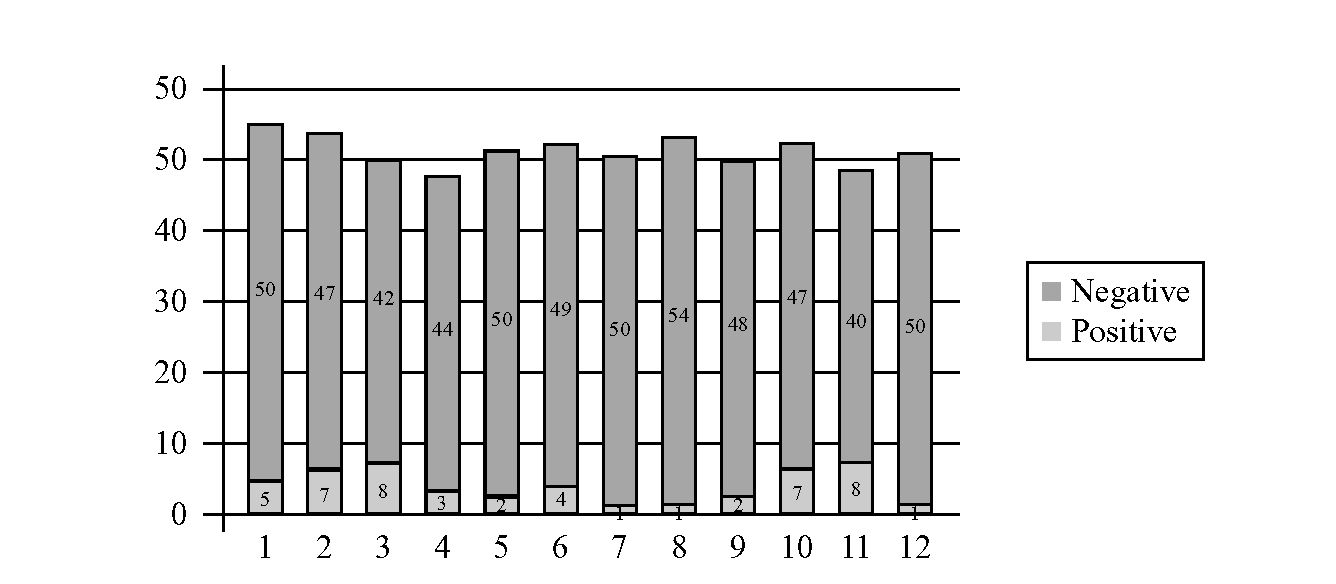

Public participation

A similar pattern could be found when respondents were asked how they evaluate the system for public participation in their countries. However, perceptions concerning public participation were somewhat more negative overall, with only a bare majority contending that the legislative framework was positive. Despite the developing practice in the field of public participation, especially within environmental impact assessment, procedural requirements (e.g., notification, accessibility of documents, and taking due account of comments) are seen as being often not implemented properly. Limitations of the capacities of ECSOs to participate effectively must be taken into account. Among the matters identified as obstacles is the practice of Croatian authorities to a restrictive interpretation of standard in EIA procedures. In some countries such as Serbia, relatively few ECSOs attempt to participate in EIA, preferring to work on a higher, policymaking level. Those ECSOs reporting that they are involved by

- 79/80 -

authorities in policymaking tend to perceive of their role as consultative only, without particular influence. Most such procedures are by invitation only, and ECSOs wish to maintain good relations to ensure their involvement, so are willing to accept a limited role.

Key:

1: Legislation regarding rights and responsibilities 2: Procedures and rules 3: Legislation enforcement

4: Knowledge about what rights citizens and CSOs have 5: Knowledge and skills about how to use rights

6: Notification about upcoming decision-making and public participation opportunities 7: Information about upcoming opportunities 8: Timeframe to prepare for the public consultation 9: Having the recources 10: Having adequate technical expertise 11 : Organization of public hearings 12: Taking into account of public comments 13: Information about comments taken into account 14: Information about the outcome of the decision-making

Access to Justice

With respect to access to justice, as seen by the following chart, the assessment of respondents was almost entirely negative. The highest positive response rates were given for access to technical expertise (17%) and standing rights for citizens and CSOs (16%) but even these figures can hardly been seen as unproblematic. The negative impressions for knowledge and skills about how to use rights, timeliness of procedures, and availability of resources for fees were almost 100% negative. The high negativity cannot be attributed to a failure to attempt to use legal justice mechanisms - altogether 36 of the ECSOs surveyed had been plaintiffs in an environment lawsuit. Lack of access to justice was particularly notable in Albania, Bosnia & Herzegovina, Montenegro and Serbia. Contributing factors were the slow pace of reform, lack of knowledge about the existence of rights, the lack of affordable legal assistance and a lack of clarity of appeal opportunities.

- 80/81 -

Key:

1: Court system

2: Access to justice requirements 3: Standing rights for citizens and CSOs 4: Existence of special standing rights for CSOs 5: Enforcement of existing legislation and court decision 6: Knowledge about rights of citizens and CSOs 7: Knowledge and skills about how to use rights 8: Timelines of procedures 9: Court fees

10: Access to lawyers and legal advice 11: Access of technical expertise

12: Availability of resources to finance fees for experts and lawyers/attorneys

Several of the matters surveyed have a relation to the Aarhus Convention. This instrument has been directly used in dozens of cases in countries of CEE and particularly in the EECCA region, or former Soviet Union. But more importantly, it has set the standard for rights of access to information, public participation and to some extent access to justice in these matters, and in doing so has raised understanding about the role of civil society and given strength and encouragement to a generation of environmentalists. Its power is exemplified by the fact that the EU reformed its own laws as a result of Aarhus. It is not yet in great use in SEE, but the Aarhus Convention may still be considered as the single most important legal development for civil society in Europe in the last generation.

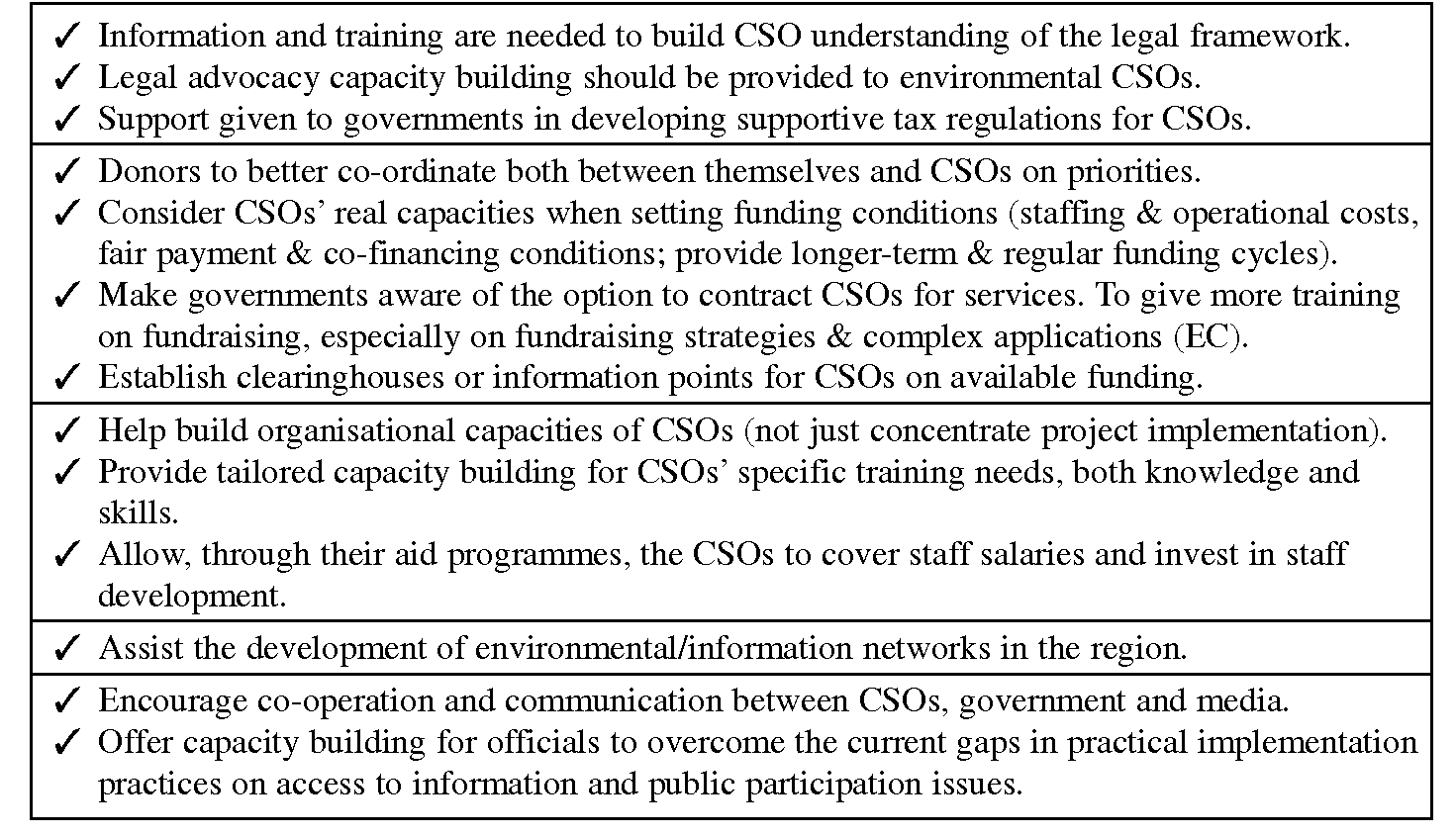

Recommendations

As a result of the SECTOR survey several sets of recommendations were produced, aimed at various elements of the survey and at different stakeholder groups. Recommendations aimed at the legal aspects of the survey are presented herein. The main sets of recommendations aimed at different stakeholder groups are set forth in the annex.

Although a good deal of work was done in many countries of the region to improve and open the registration process for CSOs, there is still room for improvement. None of the countries/territories is using the registration process to control or prohibit work

- 81/82 -

of the organizations, however, some countries make the registration very easy (e.g. Croatia), while others could improve the situation especially for the organizations outside of the capital cities (e.g., Albania), or improve capacities of the authorities dealing with the organizations in the regions (e.g., Serbia). In some countries (e.g. FYR Macedonia) measures should be taken to increase the capacity of judges to speed up the registration process.

The two-step registration process should be streamlined in countries with dispersed populations, possibly by using computerized databases that can be accessed from the regions. Authorities should proactively assist CSOs to complete registration procedures without threat of sanctions. In most countries, so many sets of norms are needed on the practical level, that all mechanisms should be tried simultaneously, including subsidiary legislation, regulations, rules, guidelines and protocols. Information campaigns and training programs are needed to consolidate understanding of the legal framework for registration and taxation.

Additional controls are needed over authorities responsible for registering CSOs, including administrative oversight and appeals procedures. As the first step in this direction, the actual implementation of registration rules and procedures should be assessed through extensive field surveys.

VAT exemptions and tax incentives are important tools for development of the CSO sector. Some countries (e.g. Montenegro) use them broadly, some others (e.g., Croatia) use them selectively only for some organizations. It is suggested to use these tools more broadly in the region and on an equal basis (regardless of when they were established or what are their activities - as long as they have a public purpose). Rules on financial and tax matters should be streamlined with a view towards encouraging private donations to legitimate CSOs. On the other hand, tax authorities should be provided with greater enforcement powers, e.g., to be able to check whether an organization's real activities are consistent with its non-profit status.

Public authorities should receive more training on implementation of existing legal requirements under the framework. Additional efforts should be made to extend legal frameworks and implementation to all communities (e.g., in Kosovo under UNSCR 1244).

Legal advocacy training and capacity building are priority areas for assistance to ECSOs, in particular aimed at strengthening capacities to make use of formal and informal opportunities and rights for access to information, public participation and access to justice.

Legal frameworks for information and participation are comparatively well advanced, but a concerted effort needs to be made to improve procedures and to boost capacities for enforcement. At least a part of the problem is perception. Authorities should pay attention to mechanisms for increasing public awareness of successes, so as to break the low levels of expectations prevalent.

Conclusion

The SECTOR survey provided the basis for an overall assessment of civil society development in the region, with extensive detailed findings in several areas of interest. The general findings of the survey have been presented in this paper, together with

- 82/83 -

more detailed findings in the area of legal and regulatory matters. South Eastern Europe as a region is going through some of the same stages of civil society development as occurred in Central and Eastern Europe in the 1990s. The series of conflicts in the region delayed reforms and civil society development, but great strides have been made in recent years. The picture provided through the survey is one of progress particularly with legislation, but includes continued deep-rooted institutional shortcomings, preventing the new legal regime from being implemented and enforced. With only a few exceptions, the countries and territories of SEE have not been able to achieve a measure of social stability sufficient to enable the slow process of development of the rule of law to take hold. Despite these obstacles, a large number of environmental civil society organizations are active in the region. It is to be expected that their continuous efforts will slowly lead towards higher standards in the application of the law related to the establishment and functioning of these organizations, and in the provision of rights and opportunities for such organizations to move towards achieving their goals through legal means. Yet, hanging above this cautiously optimistic scenario is the reality that SEE ECSOs do not have the variety and magnitude of resources available to their CEE counterparts, and their ability to achieve their goals and to demonstrate the function of civil society is unfortunately dependent on a fragile and endangered financial footing.

Annex - Main recommendations per stakeholder group

The main recommendations for ECSOs are:

The main recommendations for eovernmental authorities are:

- 83/84 -

The main recommendations for the donor community and CSO support organisations are:

■

JEGYZETEK

[1] For the purpose of the survey the research team understood an ECSO as an officially registered organisation, other public association or otherwise clearly identifiable group of citizens that: does not act as an official governmental body; is a not-for-profit entity (i.e. non-commercial); functions at any geographical level; has a presence in public life, outside of family structures, expressing the interests and values of their members or others, based on ethical, cultural, political, scientific, or philanthropic considerations; and has a main purpose related to the promotion of one or more of the following:

- protection and conservation of the environment;

- the sustainable use of natural resources and renewables;

- traditional cultural values and knowledge leading to a decrease in society's environmental impact;

- environmentally friendly development, policies and projects;

- governance principles leading to the creation of an enabling environment for environmental protection and sustainable development (e.g. anti-corruption measures, transparency, accountability, and public participation).

[2] Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, Montenegro and Serbia, including a separate section for Kosovo (under UNSCR 1244).

[3] Organisational Capacities - Adriana Craciun, Senior Project Manager, Education & Capacity Building Programme; 4) Information and Knowledge - Jerome Simpson, Head of Information Programme; and 5) Accountability - Magdi Toth-Nagy, Head of Public Participation Programme. Overall coordination was by Dr Richard Filcak, Project Manager, NGO Support Programme.

[4] Richard Filcak-Robert Atkinson (Eds.): NGO Directory of South Eastern Europe: a directory and survey findings of West Balkan environmental civil society organizations. 2007, 5[th] Edition, Szentendre (Hungary): REC, 2007, 5th Edition, 302 pages.

[5] Country Survey/Interviewed: Albania: 68/21, Bosnia & Herzegovina 88/19, Croatia 70/19, FYR Macedonia 50/18, Montenegro 14/12, Serbia 114/11, Kosovo (UNSCR 1244) 30/16.

[6] SERGIU Serban (ed.): NGO Directory: A Directory of Environmental Nongovernmental Organizations in Central and Eastern Europe. Szentendre (Hungary): REC, 2001, 748 pages.

[7] See the REC website for these products: www.rec.org/sector

[8] CEE countries were surveyed in 2007 through a joint study by REC and MIT. For more details of this survey see: http://www.rec.org/REC/Databases/NGO_Dir_CEE/cee_ngo_survey_report.pdf Those countries surveyed were: Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Slovakia and Slovenia.

[9] The results were compared to those of the 2001 survey. See Serban op. cit.

[10] The full list of topics is presented in: Robert ATKINSON: Striving for Sustainability: A Regional Assessment of the Environmental Civil Society Organisations in the Western Balkans, A summary of results, findings and recommendations. Szentendre (Hungary): REC, (2007). 24 pages. http://www.rec.org/sector/brochure/sector_brochure_2007.pdf

[11] JoAnn Carmin-Elisabeth Albright-Rachel Healy-Tegin Teich: Environmental NGOs in Central and Eastern Europe. Summary of Survey Findings 2007. Department of Urban Studies and Planning, Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Cambridge-Massachusetts, USA. (unpublished report) 2007, 34 pages. This paper can be found at the following link: http://www.rec.org/REC/Databases/NGO_Dir_CEE/cee_ngo_survey_report.pdf

[12] Further information, including results for each country or territory, are available in the unpublished project report, on file with the REC.

Lábjegyzetek:

[1] Robert Atkinson Regional Environmental Center Stephen Stec lecturer Szentendre (CEU)