Marek Antoš[1]: Constitutional Complaint and its Limits in the Czech Republic[1] (Annales, 2012., 119-132. o.)

I. Basic characteristics of the constitutional complaint

The basic definition of the institution of constitutional complaint is provided in Art. 87 (1) d) of the Constitution of the Czech Republic, which became effective on the 1[st] of January 1993, i.e. on the first day of the independent existence of the Czech Republic. Under the Constitution, the Constitutional Court has jurisdiction "over constitutional complaints against final decisions or other encroachments by public authorities infringing constitutionally guaranteed fundamental rights and basic freedoms".

This provision is rather general and contains no specification of who may file the constitutional complaint, and under what circumstances. Regarding these issues, as well as the rules of procedure and other details, Art. 88 (1) of the Constitution refers to regulation in an ordinary act; in this particular case it is Act No. 182/1993 Sb. on the Constitutional Court ("CCA").

The main objective of this paper is to introduce basic features of the institution of the constitutional complaint in the Czech Republic, the limits of its application and certain practical experience collected during almost twenty years of its existence in Czech law.

- 119/120 -

II. Statutory regulation of the constitutional complaint proceedings

II.1. Procedural standing to file the complaint

The right to file the constitutional complaint is possessed by both an individual and legal entity, should they claim that intervention by a public authority has resulted in the violation of their constitutionally guaranteed basic particular right or freedom (s. 72 (1) a) CCA). The scope of persons having the standing is defined quite widely. Most basic rights and freedoms are awarded to anyone, irrespective of their citizenship; this implies that the filing of a constitutional complaint is not bound to citizenship and may be pursued even by foreigners. Rights which, by their nature, may be applicable to legal entities can be claimed by those entities: a positive example can be the right of ownership, the contrary example being the right to life, the right not be tortured, etc.[2]

The CCA stipulates that all types of proceedings require obligatory representation by a lawyer (member of the Bar), which also applies to constitutional complaints even in cases when the complainant himself possesses a law degree. Unlike all other types of procedure, the filing of a constitutional complaint is not bound to the payment of any court fee.

There is a specific situation should the State intend to file a constitutional complaint; it is usually represented by some of its competent bodies (so-called "organizational units of the State"). The Constitutional Court awards this right to the State in cases where the State has a position equal to the other parties, typically in the field of private relations (e.g. a dispute over the ownership right of the State); should the State act in its interventive capacity of a public body[3] in a particular case it is deprived of this right.

II.2. The subject-matter of a constitutional complaint

The constitutional complaint may be directed against any intervention by a public body resulting in the violation of a basic right of the complainant.

- 120/121 -

This is usually the final decision of a public body; however, there may be a measure issued or any other intervention pursued (s. 72 CCA). A measure should be understood as an actual order or prohibition issued within the interventive powers of the State in its capacity as a public person against a particular person, which does not have the form of a decision.[4] Another type of intervention is used in the case of failure to act: the Constitutional Court may provide a complainant with protection where undue delays in their proceedings occur. In accordance with the principle of subsidiarity of constitutional justice, the constitutional complaint in such cases can be used only if there are no other means of remedy available. As a result of the case-law of the European Court of Human Rights applicable in the Czech Republic, there have been various procedural instruments introduced in Czech procedural law in order to prevent delays (such as a complaint for delays in proceedings, an application to set a time-limit for pursuing certain procedural acts, an action for the failure of an administrative body to act, etc.), which has resulted in a lower number of complaints submitted to the Constitutional Court in this respect.

II.3. Time-limits for the filing of the constitutional complaint

The Complaint may be lodged only after the complainant has exhausted all ordinary procedural instruments provided by the law for the protection of their right (s. 75 CCA), such as an appeal, administrative action, etc. A complaint submitted before all other means have been used would be rejected by the Constitutional Court as inadmissible. However, the law provides for an exception in the case of a complaint exceeding by its significance the actual interests of a particular complainant. The application of this exception requires that an element of strong and substantial public interest be present. This would typically cover situations of repeated unconstitutional applications of a law, which should be repealed or interpreted in conformity with the Constitution, or where the decision on a constitutional complaint may have an impact upon thousands of other persons and may thus prevent a massive number of court actions to be filed.[5]

- 121/122 -

The constitutional complaint should be lodged not later than within 60 days of the service of decision on the last procedural means provided by the law to protect the right at issue. The time-limit is not computed from the moment of the legal effect of the judgment but from the moment of its service to the particular party. It is considered to be a procedural time-limit, therefore it is sufficient if the constitutional complaint is submitted to the postal delivery on the last day of the time-limit; the actual receipt of the complaint to the Constitutional Court within the time-limit is not required.

II.4. The framework of decision-making and parties to the procedure

The lodgement of a constitutional complaint institutes new proceedings; the original proceedings (if applicable) were closed with a final and legally enforceable judgment, against which the complaint is directed, and do not continue. This has consequences for the subject-matter of a complaint and parties to the proceedings. In addition to the complainant there is only a public body (such as a court) against whose decision (or any other intervention) the complaint is directed, and which can defend its decision. Other parties to the original action (e.g. the opposing party in a civil litigation) closed with the challenged decision become only collateral participants in the constitutional complaint proceedings.

The grounds for a constitutional complaint may subsist only in the violation of constitutionally guaranteed human rights and freedoms; the substance of the original action becomes secondary. Therefore, the breach of an "ordinary" right protected by an ordinary law may not be raised unless constitutionally guaranteed rights have been violated thereby. The Constitutional Court has emphasized in its case-law several times that it is not part of the court system and its role is not to protect legality but constitutionality. This can be seen in that the Constitutional Court does not usually evaluate the facts of the case, except for extreme situations where evidence procedure in the original proceedings suffers from such serious defects that, as a result, it constitutes a violation of the constitutional right to fair trial.[6]

- 122/123 -

The concept of "constitutional order" is interpreted liberally by the Constitutional Court as including not only the Constitution and constitutional acts, the Charter of Fundamental Rights and Freedoms (see Art. 112 (1) of the Constitution), but also international treaties and conventions on human rights binding on the Czech Republic. Thus it is possible to claim the violation of rights guaranteed nationally (usually stipulated by the Charter of Fundamental Rights and Freedoms) but also violation of international documents such as the (European) Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms or the United Nations International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. Such an approach has an influence upon the potential argumentation by complainants who may then refer to the case-law of the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg.

II.5. An accessory application for the repeal of a law or any other legal regulation

The constitutional complaint may be complemented with an application to repeal a law or any other piece of legislation, or their particular provisions, as a result of which the basic right of a complainant was interfered with and such interference is the subject-matter of proceedings before the Constitutional Court (s. 74 CCA). Whilst an application for an abstract review of legislative rules may be submitted only by qualified applicants (the President of the Republic, 41 members of the Chamber of Deputies, or 17 Senators), here is the space for anyone to challenge the legislation. However, the Constitutional Court, in order to prevent its own overload, has interpreted this possibility rather restrictively; it is required that a law, or its part, that should be repealed, must have been directly applied to the decision subject to the constitutional complaint and mere links are insufficient.[7]

- 123/124 -

An application for the repeal must be of an accessory nature with respect to the constitutional complaint at issue; should the complaint be rejected (typically for its apparent lack of grounds) it is impossible to deal with the application autonomously. However, even if a constitutional complaint is found admissible, proceedings for the accessory application do not commence automatically. The panel (court chamber) in charge of the case must first suspend the proceedings for the constitutional complaint and refer the application for repeal to the plenary of the Court (s. 78 (1) CCA); only after the decision of the plenary session has been issued may the panel resume the proceedings for the constitutional complaint.[8] A potential failure of the application for repeal does not automatically mean that the constitutional complaint would also be unsuccessful; the plenary session may conclude that, instead of a repealing decision, interpretation of the respective provisions in conformity with the Constitution would be sufficient. However, this does not imply that the challenged decision had constituted the violation of constitutionally guaranteed rights of the complainant.

II.6. The composition of the Court

The plenary session of the Constitutional Court is composed of 15 Justices subdivided into four three-member panels.[9] Subject-matter jurisdiction of the plenary session is precisely defined in section 11 CCA; all other issues are decided by panels. The vast majority of their agenda is covered by constitutional complaints.

The plenary session of the Constitutional Court may, under the law, reserve for their determination other cases, which can be seen in practice.[10] In exceptional cases the plenary session may decide on a constitutional complaint in lieu of panels; recently, there have been constitutional complaints against decisions of Great and Extended Panels of the Supreme

- 124/125 -

Court of the CR and the Supreme Administrative Court, consideration of constitutional complaints where one party is one of the supreme constitutional bodies, etc. In addition, the plenary session may assume any other case to decide, should it be a case of extreme seriousness and significance, or should there be requirements for making the case-law of the Constitutional Court uniform. In such an extraordinary case the consent of all members of a respective panel in charge of the case is required as well as of all parties to the case.

Every constitutional complaint, at the moment of its delivery to the Constitutional Court, is assigned to one Justice-Reporter (s- 40 CCA); the Justice-Reporter is responsible for the preparation of the case to be considered by the panel or the plenary session and possesses certain autonomous procedural powers (ss. 42-43 CCA).

II.7. Decisions of the Constitutional Court and their consequences

The Constitutional Court decides on the merits in the form of a judgment, and by resolution in other matters (s. 54 (1) CCA). Resolutions are issued by the Constitutional Court in procedural issues (suspension of proceedings, costs of proceedings, etc.); however, the same decision may be delivered where a constitutional complaint has been rejected for the apparent lack of cause.[11] The Act, considering the nature of a case, expressly stipulates who may issue a resolution, and under what circumstances: in some cases it could be the Justice-Reporter him/herself (e.g. where the complaint is filed by someone apparently unqualified, or the complaint suffers from defects not removed by the complainant within an additional time-limit, or where the complaint is inadmissible); in other cases the issuance of the resolution is the responsibility of the panel.

The latter group encompasses cases where the complaint has been rejected due to the apparent lack of cause, which may be unanimously determined by the panel even without an oral hearing (s. 43 (2) CCA). However, such a decision to reject must contain a reasoning. "The contents, and particularly the scope, of the reasoning would depend on the grounds having led to the rejection of an application. However, in the case of an

- 125/126 -

apparent lack of cause in the application, the reasoning should, at least in general terms, deal with individual groups of objections submitted by applicants so that no doubts could be raised regarding the lack of cause of the application."[12]

Where a constitutional complaint has not been rejected by the Constitutional Court it will be decided by a judgment either to dismiss the complaint or to dispose of it in the affirmative and to cancel the challenged decision (s. 82 (3) CCA). In order to preserve the rules of procedural economy, the Court usually cancels not only the decision on the last means of the legal protection subject to the constitutional complaint, but also all preceding decisions in the case at issue which created a violation of the constitutional rights of the complainant. Public bodies, which are to subsequently decide on the same case, are bound by the legal opinion of the Constitutional Court, which results from its position as a court of cassation.[13]

III. The limits for the exercising (primarily) of social rights

The Charter of Fundamental Rights and Freedoms ("the Charter") provides for the restriction of constitutional rights of an individual, should there be a conflict with constitutional rights of others or a conflict with public values, such as public order, health, security of the State, etc. However, Art. 4 (4) of the Charter stipulates that "When employing the provisions concerning limitations upon the fundamental rights and freedoms, the essence and significance of these rights and freedoms must be preserved."

Although there are separate generations of human rights distinguished, particularly for historical and pedagogical reasons, individual human rights are lacking any hierarchical nature and their potential conflict should be decided in other ways, for example by applying the test of proportionality. The Czech Charter of Fundamental Rights and Freedoms contains specific provisions weakening the protection of certain rights at

- 126/127 -

the constitutional level. Under Art. 41 of the Charter, these precisely listed rights "may be claimed only within the confines of the laws implementing those provisions". All rights thus determined are contained in Title Four of the Charter providing for economic, social and cultural rights; save some minor exceptions, what is common to all of them is the requirement for the material performance by the State. There are rights such as the right to social welfare in the old age and due to incapacity to work, the right to free health care, the right to education, etc.

This restrictive provision has been part of the Charter since its adoption in 1991; the reason has usually been given that it was a political compromise between right and left wing deputies arguing whether social rights should have been included in the Charter at all, as can be read in the transcript of the debates of the Federal Assembly, which adopted the Charter. Deputy V. Ševčik (later appointed a Constitutional Court Justice), in his capacity as the reporter of committees of the House of Nations, said: "The rights in this Title are mostly relative in a sense that their development - and this applies primarily to social and economic rights - is dependent upon the situation in the national economy, particularly upon its material results. This is why the conception of these rights respects the basic principles of their enforceability through courts, however, there are no conditions for social rights provided by constitutional legislation, which should create the basis for ordinary laws. Regulation by the rule of a lower degree may not be subject to changes dependent upon the development of economic and living standards, therefore an ordinary legislator should not be bound by constitutional barriers."[14]

Art. 41 of the Charter provides the legislature a wider scope of discretion regarding the extent to which the rights defined would be practically applied. Reasons for this may be that these rights are closely linked to the redistribution of the means of the society, i.e. to one of the basic political issues which should be decided in any democratic state primarily by a parliamentary majority, which possesses legitimacy gained in free elections. However, the space for discretion is not endless: even in such

- 127/128 -

cases the Parliament is bound by Art. 4 (4) of the Charter and must respect the substance and sense of these rights.[15]

In relation to this regulation the Constitutional Court has developed a methodology with respect to the rationality test which is a reserved alternative of the proportionality principle applied to the other fundamental rights. The basis of this methodology is whether the legislation under consideration intervenes in the very core (essential content) of a social right. If the Constitutional Court finds the intervention in the essential content, the proportionality test follows, which should evaluate whether such intervention "has been evoked by an absolute exceptionality of the situation at issue, which would justify the intervention"[16] If not, the Constitutional Court would apply only a softer rationality principle to consider whether "the legislation is to observe a legitimate objective; i.e. whether it is not only an arbitrary substantial reduction of the overall standard of human rights" and "whether the legal instrument used in order to achieve the objective is reasonable (rational) not necessarily the best, the most suitable, effective or the wisest."[17] The rationality test thus respects the wide scope of discretion of the Parliament, but it excludes the restrictions of rights as a result of arbitrariness.

The quoted conclusions were drawn by the Constitutional Court within the proceedings for the abstract control of rules, upon application submitted by a group of deputies. However, Art. 41 of the Charter should be interpreted accordingly with respect to the possibility of claiming those rights in the form of a constitutional complaint. The literal interpretation could lead to a conclusion that the constitutional complaint would be excluded in such cases, or that there should be a violation whose intensity intrudes other basic rights (such as human dignity under Art. 1 of the Charter). Such interpretation would be unacceptable due to the above-mentioned Art. 4 (4) protecting the substance and sense of all rights stipulated in the Charter.

- 128/129 -

Constitutional complaints in such cases are essentially admissible; the Constitutional Court has disposed of several of them in the affirmative.[18]

IV. Conclusion

The institution of a constitutional complaint is regulated in the Czech Republic in an extraordinarily open manner[19], which can be shown by the extent of its use. I would argue that what is essential for its application is not only the wide scope of cases where a constitutional complaint may be lodged (against a decision measure or any other intervention), but also, and in particular, the wide scope of public bodies whose intervention may be challenged, including courts. The combination of those factors has turned the constitutional complaint into the key instrument for the protection of constitutionality, through which the Constitutional Court has substantially influenced judicial and administrative decision-making in many legal branches during 19 years of its existence. It could be undoubtedly possible to discuss various procedural approaches to regulation de lege ferenda; however it can be concluded that the institution of the constitutional complaint has proved to be efficient in the Czech Republic.

- 129/130 -

Annex: Statistics[20]

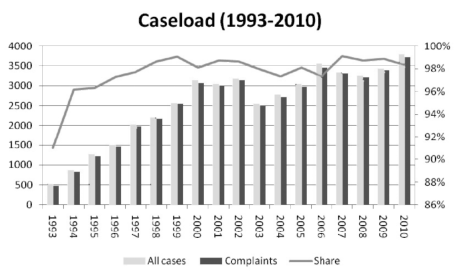

Total caseload, of which constitutional complaints (development in years)

- 130/131 -

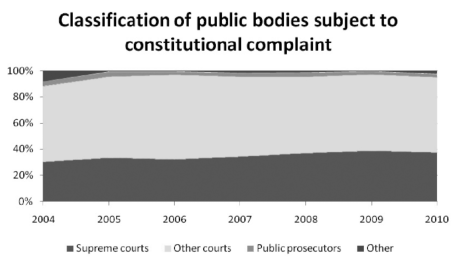

Classification of public bodies subject to constitutional complaint

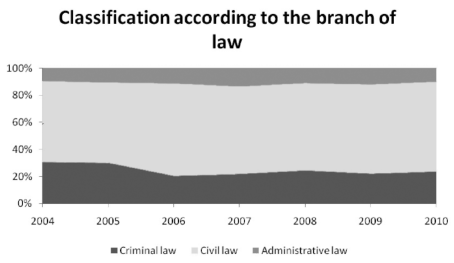

Classification according to the branch of law

- 131/132 -

Summary - Constitutional Complaint and its Limits in the Czech Republic

The Constitutional Court in the Czech Republic performs both abstract and concrete constitutional review, with the latter based mostly on individual constitutional complaints. The paper describes general conditions of the proceeding (i.e. who is entitled to file a complaint, permissibility, decisions etc.), limits of the review (esp. regarding the social rights) and the practical experience with this institute in the Czech Republic.

Resümee - Die Verfassungsbeschwerde und ihre Grenzen in der Tschechischen Republik

Das Verfassungsgericht der Tschechischen Republik übt sowohl abstrakte, als auch konkrete Formen der Überprüfung der Verfassungsmäßigkeit aus, die letztere am meisten im Rahmen des Verfahrens der Verfassungsbeschwerde. Die Abhandlung bietet einen Überblick über die allgemeinen Merkmale der Verfassungsbeschwerde (Antragsberechtigung, Zulässigkeitsvoraussetzungen, Entscheidungsausspruch etc.), die Verfahrensschranken (mit speziellem Hinblick auf die sozialen Rechte) und auch über die Erfahrungen in der Praxis dieses Verfahrens. ■

NOTES

[1] This paper was drafted with the support of the Grant Agency of the CR, project No. P408/11/P366 (Parlamentni forma vlády v ČR a možnosti její racionalizace - Parliamentarian form of Government in the CR and the potential of its rationalisation).

[2] See Wagnerová, E., Dostál, M., Langášek, T., Pospíšil, I.: Zákon o Ústavním soudu s komentářem [The Constitutional Court Act with Commentary]. Praha: ASPI, 2007, p. 321.

[3] See Judgment of the Constitutional Court of 6[th] April 2006, file No. I. US 182/05.

[4] See Ústava České republiky. Komentář. [The Constitution of the Czech Republic. The Commentary] Praha: Linde Praha, 2010, p. 1114.

[5] See Wagnerová, E., Dostál, M., Langášek, T., Pospíšil, I., op. cit., p. 387.

[6] For details see Šimíček, V.: Ústavní stížnost [The Constitutional Complaint]. Praha: Linde Praha, 2005, pp. 190-192.

[7] One example can be given, namely the dispute over the constitutionality of establishing electoral districts for the election to the Metropolitan Council of the Capital City of Prague in Fall 2010; this establishment resulted in some political parties obtaining no seats on the Council within the distribution of mandates although they had exceeded the technical electoral clause of 5 % in the election. This result was challenged first in an electoral action filed with an administrative court, whose negative decision was later subject to constitutional complaint, complemented with an application for the repeal of the provision enabling the establishment of electoral districts. However, the Constitutional Court rejected the application, since the provision, although forming the grounds for the dispute, had not been applied by the administrative court in the original action. (See the judgment of the CC of 29[th] March 2011, file No. Pl. US 52/10, item 49).

[8] See Wagnerová, E., Dostál, M., Langášek, T., Pospíšil, I., op. cit., p. 369.

[9] The President and two Vice-Presidents of the CC are not permanent members of any panel.

[10] See the Notice of the Constitutional Court on the adoption of a decision of 9[th] August 2011 No. Org. 40/11, regarding the assumption of powers, published under No. 242/2001 Sb.

[11] See Šimíček, V., op. cit., p. 263.

[12] See Wagnerová, E., Dostál, M., Langášek, T., Pospíšil, I., op. cit., p. 151.

[13] See Holländer, P.: Ústavněprávni argumentace: ohlednutí po deseti letech Ústavního soudu [Constitutional argumentation: the retrospective after the decade of the Constitutional Court]. Praha: Linde Praha, 2003, pp. 78-79.

[14] Stenographic transcript from the 11[th] common session of the House of Nations and House of the People of the Federal Assembly of the CSFR, 8[th] January 1991. Retrieved from: http://www.psp.cz/eknih/1990fs/slsn/stenprot/011schuz/s011004.htm

[15] For more details on this issue see the commentary on Art 41 of the Charter by J. Wintr in: Wagnerová, E., Šimíček, V., Langášek, T., Pospíšil, I. et al.: Listina základních práv a svobod s komentářem [The Charter of Fundamental Rights and Freedoms with Commentary]. Praha: Wolters Kluwer, 2012 (forthcoming).

[16] Judgment of the CC of 20[th] May 2008, file No. Pl. ÚS 1/08, item 104.

[17] Ibid, item 103.

[18] See the commentary on Art 41 of the Charter by J. Wintr in: Wagnerová, E., Šimíček, V., Langášek, T., Pospíšil, I. et al., op. cit., and quoted judgments II. US 348/04 and II. US 377/04.

[19] For a historical and comparative perspective see Ústava České republiky. Komentář [The Constitution of the Czech Republic. The Commentary]. Praha: Linde Praha, 2010, pp. 11101112.

[20] Data come from: Constitutional Court of the Czech Republic: Roční statistické analýzy [Annual Statistical Analysis 2010]. www.concourt.cz/clanek/GetFile?id=5568

Lábjegyzetek:

[1] Charles University, Prague