Attila Sipos[1]: The Air Carrier's Liability for Damage Caused to Cargo (Annales, 2020., 155-184. o.)

https://doi.org/10.56749/annales.elteajk.2020.lix.9.155

Abstract

The consignment of cargo always lags behind passenger traffic as the focus of attention (as well as from a legal point of view), but under the circumstances of the pandemic it became more important than ever before. Countries closed their borders, but commercial and aid operations between the states were maintained by cargo flights on state and civil aircraft. For this reason, the liability of the air carrier for cargo was also given utmost attention. The liability of the air carrier for damage during international carriage can be established - under the Convention for the Unification of Certain Rules for International Carriage by Air (Montreal Convention - 1999)[1] - in cases when 1) the death or bodily injury of the passenger is caused by an accident; 2) the baggage is destroyed, lost or damaged; 3) the cargo is destroyed, lost or damaged; 4) the carriage of the passenger, baggage or cargo is delayed. This study introduces the air carrier's strict liability for damage caused to cargo (destroyed, lost, damaged or delayed) as regulated by the Montreal Convention.

Keywords: air waybill, international carriage, code-share carriage, successive carriage, combined carriage, exoneration

I. Preface

The role of civil aviation in the global world is of outstanding significance. Its unequalled development was stopped by the COVID-19 pandemic, which as early as in the first months of 2020 took its drastic effect, and consequently, the revenue of air transport fell by 90 per cent worldwide in April. This set-back is well-illustrated by the fact that the number of passengers decreased from more than 4 billion[2] to 1.8 billion in 2020

- 155/156 -

in the largest crisis of the aviation industry since World War II.[3] Millions lost their jobs. Aircraft manufacturers downsized their capacities; airports and air navigation service providers registered severe losses. The greatest losers of the pandemic on an industrial level were the airlines, which epitomise the financial driving force of this commercial activity (aircraft are manufactured for them; they carry out the transport of persons, cargo and mail, while the surface and aerial infrastructure depend on them to a large extent). The majority of air carriers requested and received large amounts of state subsidies. Despite all these facts the cargo business[4] was not stricken severely; moreover, it started expanding during the pandemic era.

1. The carriage of cargo

The air carrier's liability extends to every international carriage of persons, baggage or cargo performed by aircraft for reward [Article 1(1)]. As a matter of course, air carriage can be divided into the carriage of persons and cargo with two differences in principle:

- upon the carriage of cargo, the object of carriage is removed from the disposal of the consignor, obviously this does not take place in the case of the transport of passengers;

- upon the carriage of cargo, a triangular legal relation is established (consignor, air carrier and consignee), while the carriage of passengers posits a bilateral legal relation (passenger and the air carrier) with the exception of code-share carriage (see III. 1), which also implies a triangular legal relation: the passenger, the contracting carrier and the actual carrier.

(The Montreal Convention contains general and specific provisions; the general provisions apply to passengers and baggage, and the specific provisions apply to cargo.)

The consignor is the person/company sending the cargo (freight) and may act through a cargo forwarder (or its agent) that engages the carrier to ship it. Consignors usually wish the cargo to be delivered to another person. This person, to whom the cargo is sent, is the consignee acting as a customer or client. The drafters of the

- 156/157 -

Convention did not avail themselves of the opportunity to define cargo; therefore, the air carriers circumscribe the scope of objects falling in this category under their General Conditions of Carriage. Accordingly, in the practice of air carriers, cargo includes, for instance, double coffins containing the mortal remains of a deceased person or carried pets and livestock (e.g., dogs, racehorses).[5] For this reason, injuries to animals must be considered under the cargo provisions of the Montreal Convention (Article 18).[6] Live animals may be forwarded pursuant to industry prescriptions and the prior consent of the air carrier. The conditions of forwarding live animals include their confinement in a regular, portable, escape-proof carrier (not hindering the movement of the animal, in compliance with industry specifications and the limitations of size and weight prescribed by the air carrier), the production of valid official, veterinary and vaccination certificates and entry permits, as well as other documents required by the prescriptions of the states concerned by the carriage.

From the enumeration of classical objects (such as baggage, cargo and mail), postal goods forward were omitted, the reason for which is that the provisions of the Convention do not apply to the carriage of postal items. As to the carriage of postal items (letters, parcels, postal orders) the lawmaker merely requires that the air carrier shall only be liable toward the relevant postal administration in accordance with the rules applicable to the relationship between the carriers and the postal administrations [Article 2(2-3)].

2. Contractual relationship

Within the framework of civil law, a written contract is concluded between the consignor of the cargo and the air carrier as an expression of their mutual and unanimous intent, which contains the designation of the place of departure and the place of destination and of the agreed stopping place(s). According to the contract of the carriage of cargo, the air carrier delivers the goods on an aircraft from the airport of departure to the airport of arrival. The air carrier may derogate from the route indicated in the air waybill for a reason related to air traffic. The contract between the parties is concluded if

- the consignor pays the fee determined by the air carrier (with the addition of authority taxes, dues and other contributions); and

- the air carrier issues the air waybill (also known as an air consignment note or informally designated an airbill).

- 157/158 -

The air waybill comprises multiple copies, so that each party involved in the shipment can document it. The air waybill, until the contrary is proved, attests at first sight (prima facie)[7] content of the legal declaration made by the air carrier and the consignor; that is, the conclusion of the contract. The sections of the journey indicated in one air waybill or connecting air waybills constitute the parts of one contract. A separate air waybill qualifies as a separate contract. The contract of carriage can be concluded freely. Nothing in the Montreal Convention shall prevent the air carrier from:

- refusing to enter into any contract of carriage;

- waiving any defences available under the Convention; or

- laying down conditions which do not conflict with the provisions of the Convention (Article 27).

Pursuant to the above, the air carrier may refuse to enter into a contractual relationship with any client for whom, for some reason, it does not wish to provide service, for instance, if the consignor does not hold appropriate documents (customs clearance form, dangerous goods' or other permits) or does not produce them in time; furthermore, if the condition of the cargo does not facilitate safe carriage. At the same time, the lawmaker expressly formulates that any clause contained in the contract of carriage and all special agreements entered into before the damage occurred, by which the parties purport to infringe the rules laid down under the Convention, whether by deciding on the law to be applied, or by altering the rules as to jurisdiction, shall be null and void (Article 49).

The Convention only generally provides for the formal requirements and the content of the documents of carriage; therefore, the numerous and complex issues emerging during the carriage shall be settled under the General Conditions of Carriage or other separate rules specified by the air carriers. Pursuant to these rules, the air carriers set out the rights and obligations of the consignors and the conditions of the carriage of cargo in detail.

3. General Conditions of Carriage

The detailed conditions of the contract of carriage concluded between the air carrier and the consignor not specified under effective regulations are stipulated under the General Conditions of Carriage. The provisions of the General Conditions of Carriage constitute part of the contract between the air carrier and the consignor.

The General Conditions of Carriage, containing the conditions integral to the contract, does not constitute a legal statute, but it regulates the servicing strategy of

- 158/159 -

the airline, which is predetermined unilaterally by one of the parties (the air carrier) in order to conclude several contracts via the establishment of the servicing framework, while the other party (the consignor) is not involved in determining the conditions part of the contract.

It is therefore a basic legal requirement that the air carrier may not unreasonably and disproportionately determine the rights and obligations of the contracting parties proceeding from the contract to the detriment of the consignor. This is guaranteed by the obligation of the party applying the General Conditions of Carriage to prove the fact of the contingent violation of the law; furthermore, the General Conditions of Carriage is to be drafted by the airline in consideration of international and EU regulations and the International Air Transport Association (IATA)[8] specifications and recommendations, as well as the national statutes and authority prescriptions with the approval of the authority. The General Conditions of Carriage may not be contrary to statutes but, apart from this, the air carriers decide themselves, maybe differently, what services under what conditions they provide for the consignors. For reasons of flight safety, the air carrier may prohibit or restrict the transport of various goods or items.

The General Conditions of Carriage becomes part of the contract if its applier has enabled the other party to familiarise themselves with its content prior to concluding the contract and the other party consented to this. In this way, the specifications of the General Conditions of Carriage are made accessible to consignors by the air carriers so they can become familiar with them, either in their customer service offices or electronically. The IATA prescribes that consignors shall be notified of the fact that the detailed and all-encompassing system of the conditions of carriage is contained in the General Conditions of Carriage of the air carrier.

The IATA determined the minimum conditions of the contract to be applied by its member airlines as recommended practices in Carrier Agreements.[9] If the General Conditions of Carriage and the contract differ from each other, the latter is decisive and becomes the guideline. Any breach of the obligations determined under the contract of carriage entails legal consequences.

4. International Carriage (extended to passengers)

According to the nature of the activity, carriage can be divided into international and domestic carriage. The Convention encompasses international air carriage exclusively,

- 159/160 -

not domestic carriage. The lawmaker defines the concept of international air carriage precisely, since this is one of the basic conditions of the applicability of the Convention. The precise definition of the document of carriage, proving the existence of the contractual relationship and of international carriage, provides help in establishing its international character. The document of carriage is the first manifestation and proof of the contractual relationship, which, upon the consignment of cargo, including the air waybill or the cargo receipt (analogically for air passenger is the air ticket and, upon checking baggage in the baggage identification tag).

The air waybill unambiguously indicates the place of departure and the place of destination, as well as the agreed stopping place(s), which are significant for the carriage to qualify as international. For the purposes of the Montreal Convention, the expression "international carriage" means any carriage in which, according to the agreement between the parties,

- the place of departure and the place of destination - whether or not there is a break in the carriage - are situated within the territories of two States Parties; or

- the place of departure and the place of destination are within the territory of a single State Party, if there is an agreed stopping place within the territory of another State, even if that State is not a State Party to the Montreal Convention.

The latter point aimed to unify the regulation of air cargo in the broadest practicable scope. Initially, the documentation of the carriage is examined, because that is indispensable for establishing the personal and substantive scope of application and jurisdiction. If the carriage qualifies as international, the Convention is applicable; if, pursuant to the Convention, the carriage is not international, liability for damages shall be adjudged under national law of the state which has jurisdiction. In air transport flying over borders is unequivocally deemed to be international carriage, although this fact in itself under the Convention, and emphatically merely here, does not imply the qualification of the carriage as international. Cambodia has not acceded to the Montreal Convention, whereas, it has ratified the Warsaw Convention (just like, for instance, Iraq, Iran or Yemen), thus, the passengers on the flight travelling one way from Phnom Penh to London (PNH-LHR) or from London to Phnom Penh (LHR-PNH) are not governed by the Montreal Convention, therefore, these flights are not international. But in case the flight takes place between Phnom Penh-London-Phnom Penh (PNH-LHR-PNH), it is governed by the Warsaw Convention, therefore, the flight shall be international. At the same time, if the destination is Funafuti (FUN), the capital of Tuvalu in the Pacific Ocean, on the route connecting Funafuti-Phnom Penh-London-Funafuti (FUN-PNH-LHR-FUN) or on the one way route to London from Funafuti (FUN-LHR), the passengers shall be subject to the rules of liability for damage under the national law of Tuvalu, since the flights are not deemed to be international given that Tuvalu has not ratified either the Montreal Convention or the Warsaw Convention.

- 160/161 -

Pursuant to the rules of the Convention, what is not deemed to be international is determined solely and exclusively by the geographical connecting points designated under the contract of carriage. For instance, in an air waybill the following geographical connecting points need to be indicated:

- the place of departure: the town or airport indicated in the first place in the air waybill;

- the place of destination: the town or airport indicated as the last place in the air waybill;

- the agreed stopping place: all towns or airports indicated between the first place and the last place.

The agreed stopping place may imply more than one geographical connecting point, if, in the air waybill, several landing or transhipment places are indicated. The places of departure and destination are of crucial importance. Whether the states of the geographical connecting points have ratified the Montreal Convention is a further essential aspect.

Let us consider an example, that the country of town [A] ratified the Montreal Convention, whereas the country of town [B] did not ratify it. Pursuant to the definition under the Convention:

- on route ([A]-[B]), between town [A] and town [B], or

- on route ([B]-[A]) between town [B] and town [A], the carriages are not deemed to be international.

For example, the best way to comment on the variety of the carriages, the return air ticket of the passenger:

- the return flight on route [A]-[B]-[A], the carriage is deemed to be international;

- the return flight on route [B]-[A]-[B], the carriage is not deemed to be international.

In the case of the carriage of passengers, the flight travelling on route [A]-[B]-[A] qualifies as international carriage, irrespective of the fact that the country of town [B] did not accede to the Convention. This applies even in the event that damage occurs in the territory of the country of town [B], or the flight is operated by the airline of a country not acceded to the Convention with its own crew, and if the citizens of the country of town [B] are on board exclusively. Despite these circumstances, the Convention is governing, since the citizenship of the passengers, the geographical point of the occurrence of damage or the place of business, the headquarters of the airline performing the carriage or the State of the registration of the airplane do not matter in the least, nor does the fact whether the flight is non-scheduled or operated according to a schedule. What matters is merely one aspect: the route delineated by the geographical connecting points indicated in the document of carriage. Precisely this positively determined route may qualify according to the criteria stipulated under

- 161/162 -

the Convention as international or non-international carriage. The international character of the carriage is key issue because this is one of the basic conditions of the applicability of the Convention.

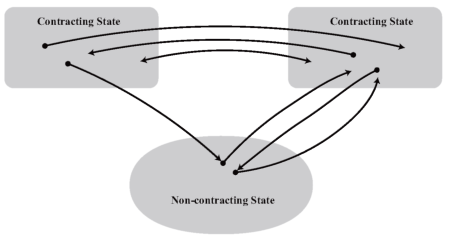

Figure 1. International air carriage (5 instances)

If the aircraft of the State Party lands in a State that has not acceded to the Convention and then it continues its flight to another State that has acceded to the Convention, the Convention shall be applicable. Pursuant to the provision of the Convention, this carriage qualifies as international, since, for instance on route [A]-[B]-[C], the country of town [C] indicated as a place of destination acceded to the Convention.

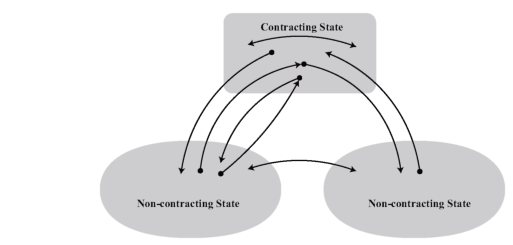

Figure 2. Non-international air carriage (6 instances)

Pursuant to the Convention, domestic carriage in itself does not qualify as international. Within the purview of the Convention, the carriage also does not qualify as international

- 162/163 -

if the carrier travelling between two points of a State Party lands in another State as well, but the parties did not designate an agreed stopping place [Article 1(2)]. If the aircraft performs domestic carriage but, for technical, meteorological or other extraordinary reasons (e.g., hijack, forced landing, medical aid) it is forced to land in the territory of another State, the onward carriage qualifies as domestic, because the place of landing was not stipulated jointly and in advance in the contract as an agreed stopping place by the parties.

The examination of the international character of carriage would lose its significance if all the ICAO Member States ratified the Convention, which is utopian. Since this is unlikely in the near future, it will occur further on that, in the actions for damages by two passengers, or two different cargo units on the very same flight, depending on the route to which their air ticket or air waybill entitles them, irrespectively of the citizenship of the passenger or consignor and the nationality of the operating airline, different rules of liability for damages will be applicable.[10]

This implies that the claims for damages of the consignors on a specific cargo flight are adjudged individually and differently (dependant on the applicability of the Convention) in consideration of the place of departure and the place of destination and, if this applies, of the agreed stopping places indicated in the air waybill. Consequently, on a specific flight there may be goods to which different rules of liability apply for the simple reason that these are transported in different contractual relations. For instance, one cargo unit is just arriving at its destination, while, for the other cargo unit, this is an agreed stopping place, from where these goods are carried further or are returned.

It may have been simpler if the drafters of the Convention had not demanded the examination of the applicability of the Convention according to the contracts from consignor to consignor (from passenger to passenger), but if they had taken into account the specific aircraft itself upon the occurrence of damage. This can be conceived as follows: the consignors of all the cargo on the flight subject to the Convention, upon the occurrence of damage, would be without exception indemnified under the same regime

- 163/164 -

of liability for damages; that is, on the same flight, the same private legal rules of liability would apply to each consignor at all times. The legal status of the aircraft subject to the scope of the Convention would be determined by whether the State which registered the aircraft is party to the Convention. However, the drafters of the Convention did not opt for this opportunity, but they chose a more complicated form, in which the emphasis is laid on the contractual relation relevant in the air waybill.[11]

5. The air waybill or cargo receipt

The documents of carriage have probative force; they attest the conclusion of the contract by the parties, proving without doubt the route acknowledged by the parties, which is necessary for the establishment of the applicability of the Convention. They are made out in writing; in the case of the consignment of cargo, the air waybill or the cargo receipt [Article 4(1-2)], [in the case of the passenger, the air ticket and the baggage identification tag (Article 3)].

The provisions of the Montreal Convention simplify and renew the specifications concerning the documentation of the carriage of cargo considerably. Air waybills are designed and distributed by the IATA. There are two types of air waybills: an airline-specific and a neutral one. Each airline-specific air waybill must include the air carrier's name, head office address, logo, and an air waybill number. Neutral air waybills have the same layout and format like airline-specific air waybills. An air waybill has 11 numbers and contains eight sheets of varying colours. However, paper-based air waybills are no longer required; e-air-waybills have been in use since 2010.[12] Due to a strategic objective, the IATA has made the documents of carriage paperless within a simplification programme. In the modern, paperless world, in the reality of the electronic air waybill, it suffices to send a message from an iPhone, by fax or email or to produce either an invoice or a memorandum made out by an agent, furthermore, merely to be registered by the IATA or the air carrier, all of which prove the conclusion of the contract.[13] This new system entails considerable financial and administrative relief not only for the industrial performers, but it also rendered access to air services substantially easier for the consignors (and for the passengers).

In respect of the carriage of cargo, an air waybill shall be delivered [Article 4(1)]. The most important functions of the air waybill include that it emphasises the limited liability provision (only where the Warsaw Convention and its system is applicable),

- 164/165 -

provides evidence of the terms and conditions of the contract of carriage, serves as an acknowledgement of the receipt of the cargo by the air carrier and furnishes evidence of the description and the condition of the cargo when it was received by the carrier.[14]

Upon the carriage of cargo, the consignor transfers the cargo to the disposal of air carrier, so it is unable to influence either the process of the carriage or the conduct of the air carrier during the consignment. Therefore, all circumstances of the carriage need to be regularly documented. The Convention permits that the air waybill may be substituted by any other instrument that records the carriage to be performed. Issuing such in electronic form had already been facilitated under the Montreal Additional Protocol 4 (MAP - 1975).[15] If the air waybill is issued electronically, the carrier shall, if so requested by the consignor, deliver to the consignor a cargo receipt permitting identification of the consignment and access to the information contained in the record [Article 4(2)]. The Montreal Convention has incorporated all relevant provisions of the Montreal Additional Protocol 4 (e.g., paperless air waybill, unbreakability (inviolability) of the liability limits, simplification, jurisdictions etc.).

Upon the carriage of cargo, the air waybill or the cargo receipt as prima facie evidence proves the conclusion of the contract, the acceptance of the cargo and the conditions of carriage mentioned therein [Article 11(1)]. The air waybill or the receipt of cargo proves the route agreed on by the parties without doubt, therefore, it contains three obligatorily prescribed elements:

- an indication of the place of departure and the place of destination;

- if the places of departure and destination are within the territory of a single State Party, one or more agreed stopping places being within the territory of another State, an indication of at least one such stopping place; and

- an indication of the weight of the consignment (Article 5).

In practice, the airway bill will also contain the consignor's (shipper's) name and address, the consignee's name and address, a three-letter departure (origin) airport code, a three-letter destination airport code, a declared shipment value for customs, the number of pieces, gross weight, a description of the goods and any special instructions (e.g., fragile, perishable, dangerous, temperature controlled). If the persons named only in the air waybill are not the cargo forwarder or its agent, the consignor and the

- 165/166 -

consignee can enforce rights under the contract of carriage.[16] The air waybill serves on one hand as a receipt of goods issued by the air carrier, and on the other hand as a contract of carriage between the consignor and the air carrier. It is a legal agreement, enforceable by law after the consignor (or the consignor's agent) and the air carrier (or the air carrier's agent) have both signed the document.

The lawmaker significantly simplified the requirements pertaining to the documents of carriage under the Convention. The Warsaw Convention[17] required the mandatory indication of 17 pieces of information and data, of which failure to indicate 10 of them resulted in the carrier forfeiting the opportunity for the application of limited liability guaranteed under the Warsaw Convention and having to perform unlimited liability for any contingent damage to cargo.[18]

The air carriers may oblige the consignor to meet, if necessary, the formalities of customs, police and similar public authorities, to deliver a document indicating the nature of the cargo. This provision creates no duty, obligation or liability for the carrier resulting from it (Article 6). This new rule gives rise to the air carrier's simple obligation to furnish information which otherwise it needs to provide for the proceeding customs, police and other public authorities pursuant to national law. The consignor must furnish such information and such documents as are necessary for the examinations carried out by the customs, police and any other public authorities before the cargo can be delivered to the consignee. The consignor is liable to the carrier for any damage occasioned by the absence, insufficiency or irregularity of any such information or documents, unless the damage is due to the fault of the carrier, its servants or agents. The carrier is under no obligation to enquire into the correctness or sufficiency of such information or documents [Article 16(1-2)].

The carriage of cargo posits a triangular legal relationship. According to this, the air waybill shall be made out by the consignor in three original parts:

- The first part shall be marked "for the carrier", and it shall be signed by the consignor;

- The second part shall be marked "for the consignee" and it shall be signed by the consignor and the air carrier;

- The third part shall be signed by the air carrier, who shall hand it to the consignor after the cargo has been accepted.

The signature of the carrier and that of the consignor may be printed or stamped. If, at the request of the consignor, the carrier makes out the air waybill, the carrier shall be deemed, unless there is proof to the contrary, to have done so on behalf of the

- 166/167 -

consignor [Article 7(1-4)]. If cargo consisting of multiple packages or pieces needs to be consigned and, upon the issuance of the air waybill, a document made out electronically (other instrument) is used

- the carrier of cargo has the right to require the consignor to make out separate air waybills;

- the consignor has the right to require the carrier to deliver separate cargo receipts (Article 8).

However, if the aforementioned basic requirements concerning the documents of cargo carriage (Articles 4-8) are not observed according to the specifications of the Convention, non-compliance shall not affect the existence or the validity of the contract of carriage (in a similar manner to air tickets), which shall, nonetheless, be subject to the rules of the Convention, including those relating to limitation of liability (Article 9). The consignor is responsible for the correctness of particulars and statements relating to the cargo. The consignor shall indemnify the air carrier against all damage suffered by it, or by any other person to whom the carrier is liable due to the irregularity, incorrectness or incompleteness of the particulars and statements furnished by the consignor or on its behalf. At the same time, the carrier shall indemnify the consignor against all damage suffered by it, or by any other person to whom the consignor is liable, due to the irregularity, incorrectness or incompleteness of the particulars and statements inserted by the carrier or on its behalf in the cargo receipt or in the record preserved by other means [Article 10(1-3)].

Any statements in the air waybill or the cargo receipt relating to the weight, dimensions and packing of the cargo, as well as those relating to the number of packages, are prima facie evidence of the facts stated. The statements relating to the quantity, volume and condition of the cargo do not constitute evidence against the air carrier, except so far as they both have been and are stated in the air waybill or the cargo receipt to have been checked by it in the presence of the consignor, or relate to the apparent condition of the cargo [Article 11(2)]. The furnishing of correct data and the clarification of real circumstances are legal obligations beyond the confidential relationship between the contracting parties, because, if they carry special cargo which requires distinct attention and care (e.g., baby chicks, animals, perishable products), a factual statement concerning its condition is necessary and an agreement on the conditions of carriage can be reached with its due consideration. These pieces of information have significance with respect to the establishment of the scope of liability for damage caused during the carriage.

- 167/168 -

6. Carriage performed in extraordinary circumstances

The provisions concerning the documentation of the carriage of cargo shall not apply in the event of carriage performed in extraordinary circumstances outside the normal scope of a carrier's business (Article 51). The lawmaker does not define flights under extraordinary circumstances. These may include experimental flights, air navigation flights (e.g., the air carrier flies over a polar route) and calibrating flights, when the devices and the navigation system of the airport are checked, as well as when the devices of the aircraft are set during the flight. Similar flights encompass the rescue of persons or merchandise from war zones by state or civil aircraft and flights not aligned with the normal operation of the aircraft due to flight safety risks, meteorological circumstances or other events unrelated to ordinary operation by the air carrier. In these cases, no legal consequences (sanctions) are set forth by the lawmaker vis-à-vis the air carrier that is non-compliant with the content and formal requirements of the documents of carriage.

II. The transportation of cargo

The concept of air cargo is not unfolded by the lawmaker; as such, its interpretation is restricted to national level. Air cargo includes essentially all portable, valuable objects forwarded by the air carrier. With respect to the fact that, in the event of the destruction, loss of or damage to the cargo, it can always be replaced, repaired or reproduced, the lawmaker is less rigorous in this area, and focuses primarily on accidents sustained by persons instead (of course, this is not valid for priceless works of art or treasures, which are generally forwarded by aircraft, but these objects have separate, special insurance from the outset). The destruction of the cargo does not only mean the physical annihilation of the cargo, but it also involves the change of the features or the substance of the cargo, therefore, due to its damage, it cannot be used in compliance with its original designation.[19] The similarity between the loss and the destruction of the cargo is that, in both cases, the cargo forfeits its financial value or utility.[20] Transporting cargo is a complex task for the air carriers. However the cargo does not cause damage "purposefully", or does not act "unlawfully" etc., due to which it would require enhanced protection or attention. It is not accidental that, in the event of damage to cargo, the amount of liability of the air carrier for damage is weight-based and limited.

- 168/169 -

1. The time period of air carriage

The air carrier is liable for damage sustained in the event of the destruction, loss of or damage to cargo on condition that the event which caused the damage so sustained took place during its carriage by air [Article 18(1)]. Air carriage implies the time period during which the cargo is in charge of the air carrier. Its duration, as a main rule, does not extend to any carriage performed outside the airport by land, by sea or by inland waterway.[21]

If, however, such carriage takes place in the performance of a contract for carriage by air in order to load, deliver or transship it, any damage is presumed, unless there is proof to the contrary, to have been the result of an event which took place during the carriage by air. The air carrier may substitute air carriage by another mode of transport, for instance, on public roads by truck, but this possibility shall be due to prior agreement under the air waybill by the parties. In such cases, the liability of the air carrier prevails during the whole section of road transport, with respect to the fact that the parties deem consecutive forwarding to be one carriage.[22]

The carrier may also resort to other modes of transport without the consent of the consignor. If a carrier, without the consent of the consignor, substitutes carriage by another mode of transport for the whole or part of a carriage intended by the agreement between the parties to be carriage by air, it is deemed to be within the period of carriage by air [Article 18(3-4)]. If the cargo is deposited in a bond store outside the area of the airport, but it remains in the charge of the airline and its agent,[23] this time period is deemed to be part of carriage by air. The liability of the air carrier prevails, because upon the establishment of liability for damage, supervision, not the location, has legal preponderance.

2. The delivery of cargo

The consignor has a right of disposition over the cargo. This right is due to the consignor if it carries out all its obligations under the contract of carriage. The consignor in possession of the right of disposition may:

- withdraw the cargo at the airport of departure or destination; or

- stop the cargo in the course of the journey on any landing; or

- call for the cargo to be delivered at the place of destination or in the course of the journey to a person other than the consignee originally designated; or

- require the cargo to be returned to the airport of departure.

- 169/170 -

The consignor must not exercise this right of disposition in such a way as to prejudice the carrier or other consignors and must reimburse any expenses occasioned by the exercise of this right. If it is impossible to carry out the instructions of the consignor, the carrier must so inform the consignor forthwith [Article 12(1-2)]. If the carrier carries out the instructions of the consignor for the disposition of the cargo without requiring the production of the part of the air waybill or the cargo receipt delivered to the latter, the carrier will be liable, without prejudice to its right of recovery from the consignor, for any damage which may be caused thereby to any person who is lawfully in possession of that part of the air waybill or the cargo receipt. The right conferred on the consignor ceases at the moment when the carrier delivers the cargo to the consignee. Nevertheless, if the consignee declines to accept the cargo, or cannot be communicated with, the consignor resumes its right of disposition [Article 12(3-4)]. As long as the consignor has not exercised its right of disposition over the cargo, that is, the cargo has arrived at its destination, the consignee, after the payment of the due charges and compliance with the conditions of carriage, becomes entitled to require the air carrier to transfer the delivered cargo and to receive it. Unless it is otherwise agreed, the air carrier is obliged to notify the consignee of the arrival of the cargo. Notification needs to take place at the earliest convenience. Although the Convention does not prescribe a concrete time, action needs to be taken as early as possible in compliance with the situation. For instance, in the case when the consignee was notified 19 hours after the arrival of the expiring cargo, the court did not deem the duration between the arrival and the notification to be suitable and so it obliged the carrier to pay indemnity.[24]

If the cargo was lost and the carrier admits its fact, or, if the cargo did not arrive after the expiry of seven days after the date on which it should have arrived, the consignee is entitled to enforce the rights which flow from the contract of carriage against the carrier [Article 13(1-3)]. Not only the consignee but also the consignor may enforce their rights proceeding from the former provisions (Articles 12-13). During the enforcement of their rights, the obligees, the consignor and/or the consignee each proceed in its own name, whether it is acting in its own interest or in the interest of another, provided that it carries out the obligations imposed by the contract of carriage (Article 14). The provisions above do not affect the relations of the consignor and the consignee with each other, nor the mutual relations of third parties whose rights are derived either from the consignor or the consignee. If the consignor or the consignee intends to derogate from the rules above, they can do so by express provision in the air waybill or the cargo receipt on the intention of modification [Article 15(1-2)].

- 170/171 -

3. Delay

The air carrier is liable for damage occasioned by delay in the carriage of cargo by air (Article 19). Numerous reasons for flight delays are well-known; most often technical failures and various meteorological circumstances cause problems. At the same time, increased waiting time because of deficient airport infrastructure (e.g., lack of ground handling equipment) or the saturation of the airspace brings about delays. The specific tasks of aviation security and their implementation and even the inappropriate handling of cargo may also lead to delays. Delayed connecting flights contribute to further delays and the reasons deriving from the faults of administration are not scarce either. The lawmaker includes delays under the scope of liability of the air carrier for damages, since the consignors opt for air transport as a mode of carriage not only because of its safety, but chiefly because of its speed. The quality of the service is determined essentially by its rapidity and punctuality; punctual departure is simultaneously the pledge of delivery in time. If the air carrier cannot adhere to the timetable, the quality of its service suffers and damage, calculable in numbers, arises.

The Convention does not define the concept of delay. We think of delay in general when the cargo fails to arrive at the destination in time. The concept provides broad scope for interpretation. It is significant to separate the conceptual scope of delay from all other situations which the applier of the law does not wish to adjudge under the legal title of delay pursuant to the provisions of the Convention. The separation is necessary, since legal cases not falling under the category of delay shall be adjudged under the legal title of breach of contract on the basis of national law.

The category of delay does not extend to the case of non-departing, i.e., cancelled flight. The cancellation of the flight may have several reasons, mainly technical failure, accident, extreme weather circumstances, the act of a third party or strike.[25] From a legal viewpoint, it is essential that the air carrier does not carry the consignor's goods to the destination or to the next stop stipulated under the contract (because another flight is not feasible, there is no connecting flight etc.). In such a case, the air carrier breaches the contract, therefore, it is liable and indemnifies the consignor pursuant to the rules of national law.

If the cargo is delayed, the person entitled to receipt (the consignee) shall make a complaint to the air carrier at the latest within twenty-one days from the date on which the cargo has been placed at its disposal. On the basis of the complaint, the claim of the obligees for damages is adjudicated. Every complaint must be made in writing and given or dispatched to the air carrier within the deadline of twenty-one calendar days. The omission of the deadline entails forfeiture. The delayed initiation of action may not be exempted, with the exception of when the air carrier, in order to evade its obligation of indemnification, commits fraud (e.g., by stalling for time) [Article 31(2-4)].

- 171/172 -

III. The limited liability of the air carrier

In cases of damage to cargo, as well as upon the delayed carriage of cargo, the liability of the air carrier is limited to an amount of 22 SDR per kilogram [Article 22(3)].[26] The air carrier's liability is strict, limited and unbreakable. As the Montreal Additional Protocol 4 (MAP - 1975) stipulates under Article 8(2) "such limits of liability constitute maximum limits and may not be exceeded whatever the circumstances which gave rise to the liability" (see, I.4.) the claimant cannot break through the limited liability (unless they make a declaration of excessive value or if the Warsaw Convention, or the Warsaw Convention as amended by the Hague Protocol,[27] are applicable to the carriage of cargo).[28] The rules of the Montreal Convention pertaining to cargo guarantee less legal protection for the consignor than to the passenger, considering that the majority of objects can be reproduced and remanufactured. Therefore, the lawmaker stipulates that the liability of the air carrier for damages in the event of the destruction, loss or delay of, or damage to, the cargo is low and limited. For this reason, the air carrier cannot be obliged to pay more indemnity than the maximum amount. This is a fixed amount binding the parties. It cannot be exceeded even if the conduct of the servant of the air carrier caused the loss of or damage to the cargo. An exception from this is if the damage resulted from the act or omission of the air carrier, its servants or agents, done with intent to cause damage or recklessly and with knowledge that damage would probably result, provided that, in the case of such act or omission by a servant or agent, it is also proved that such servant or agent was acting within the scope of their employment [Article 22(5)].

If the consignor intends to have the air carrier forward cargo of higher value, it may make a special declaration of excessive value (interest). The fixed amount determined in the declaration provides sufficient guarantee for the consignor so that it can be reassured about its cargo. The condition of making a special declaration of interest in delivery at destination is that the consignor of the cargo determines the real value in the declaration and pays a supplementary sum if the case so requires. It means that the air carrier shall be liable up to the declared sum unless the sum is greater than

- 172/173 -

the consignor's actual interest in delivery. For this reason, if the consignor declares the value in bad faith and the air carrier proves that the declared sum exceeds the actual interest of the consignor in delivery at destination, the air carrier will not pay the sum exceeding the real value [Article 22(3)].

In the event of the destruction, loss, damage to or delay of the consigned cargo, for the purpose of establishing the upper limit of the liability of the air carrier, the total weight of the package or packages concerned shall exclusively be taken into consideration. Nevertheless, when the damage to or delay of a part of the cargo affects the value of other packages covered by the same air waybill (or the same receipt), the total weight of such package(s) shall also be taken into account in determining the limit of liability [Article 22(4)]. In calculating liability only the weight of the package(s) concerned are taken into account. If some parts of the whole cargo are damaged, the question arises: for which part is the air carrier liable? In the Motorola versus Federal Express case, the defendant could not provide evidence that the damage to several mobile telecommunication station modules did not affect the value of the whole station, so the court awarded full restitution to the injured party based on the weight of the entire shipment.[29] In the Deere & Co. versus Deutsche Lufthansa case, the shipment consisted of various components together comprising a mainframe computer. The damaged package contained one of those components, namely the "directors frame". These damaged computer parts were not easily replaceable with similar parts, so, upon adjudication, the total weight of the shipment was taken into account by the court.[30] In these cases, the damage to a part of the cargo results in the consideration of the weight of the entire shipment as a basis of indemnification.

The air carrier may stipulate unilaterally that the contract of carriage shall be subject to higher limits of liability than those provided for in the Convention or to no limits of liability whatsoever (Article 25). This new opportunity of application and the client-friendly step manifested on the part of the air carrier rarely ensues in practice.

The lawmaker expressly prohibits provisions aiming to exclude the air carrier from liability or impose a lower limit of liability than that laid down in the Convention. In this way, the air carrier cannot evade the prevalence of the limits of liability stipulated in the Convention. If the air carrier still sets out such a limiting provision, it is null and void, but the nullity of the contested provision does not involve the nullity of the whole contract. Its provisions, apart from the contested part, remain effective (Article 26).[31]

- 173/174 -

The drawback of the limited liability for damage is that the amount of compensation to be paid to the obligees is generally deemed low, since it is not always in proportion with the extent of the damage sustained. Therefore, the consignor needs to purchase supplementary insurance so that, in the event of damage, besides the indemnity paid by the air carrier, they can receive further compensation depending on the amount paid and the conditions set out in the insurance contract. This conception does not conform entirely to the basic principle of compensation deriving from the liability for damages, the essence of which is that the claimant needs to be restituted in such a situation as if the damage had not occurred. The entity liable for the damage is obliged to restore the original state (in integrum restitutio). Obviously, the phrase of the original state has a literal, but also a metaphorical meaning.[32] If the consignor recovers the object stolen from the cargo unit, the original state is reinstated indeed. However, if the cargo is destroyed, restitution to the former state becomes impossible. In this case, the damaging party indemnifies the damage caused. If the actual damage does not exceed the upper limit, the air carrier indemnifies the damage of the claimant within the limited amount with respect to the extent of the proven damage.

1. Limited liability of code-share carriage

It was under the Guadalajara Agreement (1961)[33] that special rules were formulated for the first time pertaining to the contracting and the actual carrier, which were incorporated into the system of rules set forth under the Montreal Convention by the lawmaker. The provisions of the Convention are to be applied to the so-called "code-share" carriage performed by the actual carrier instead of the contracting carrier. The code-share carriage is realised via an agreement between two or more air carriers. On the basis of the agreement, the air carriers operate the specific flight jointly under a common flight number on a route determined by them, on which the whole or part of the carriage shall be performed by the actual carrier.[34] The provisions of the

- 174/175 -

Convention apply when a contracting carrier makes a contract of carriage governed by the Convention with a consignor or with a person acting on behalf of the consignor, and the actual carrier performs, by virtue of authority from the contracting carrier, the whole or part of the carriage. Such authority shall be presumed in the absence of proof to the contrary (Article 39). Despite the fact that, in such a relation, two or more air carriers are concerned, the legal relation between the parties remains bipolar, since the consignor is only engaged in a legal relation with the contracting carrier. In this case, no contractual legal relation exists with the actual carrier. However, this fact does not imply that the carriage does not qualify as international, and consequently, the Convention is not applicable. In this case, both the contracting carrier and the actual carrier shall be subject to the rules of the Convention:

- the contracting carrier for the whole of the carriage contemplated in the contract; whereas

- the actual carrier solely for the carriage which it performs (Article 40).

The lawmaker serves the interests of the consignors by stipulating the joint liability of the contracting and the actual carrier for each other's acts and omissions:

- The acts and omissions of the actual carrier and of its servants and agents acting within the scope of their employment shall, in relation to the carriage performed by the actual carrier, be deemed to be also those of the contracting carrier.

- The acts and omissions of the contracting carrier and of its servants and agents acting within the scope of their employment shall, in relation to the carriage performed by the actual carrier, be deemed to be also those of the actual carrier.

The lawmaker creates the balance of joint liability by protecting the carrier performing the air carriage vis-à-vis the contracting carrier. The essence of the protection is that the lawmaker attaches the contract of the contracting carrier with the customer to conditions, thereby restricting its content. Thus, the contracting carrier may not conclude a special agreement

- on the basis of which the contracting carrier assumes obligations not imposed by the Convention; or

- which pertains to waiving rights or defences conferred by the Convention; or

- under which a separate declaration of interest in delivery at destination with respect to cargo affects the actual carrier unless agreed to by it (Article 41).

No act or omission may subject the actual carrier to liability exceeding the amount referred to under the Convention in Article 22. Any complaint to be made or instruction to be given under the Convention to the air carrier shall have the same effect, whether it is addressed to the contracting carrier or to the actual carrier. Nonetheless, instructions concerning the right of disposal over the cargo shall only be effective if they are addressed to the contracting carrier (Article 42). It is important to highlight that the plaintiff cannot break through the limited liability of the air carrier related to damage to cargo and delay. In relation to the carriage performed by the actual

- 175/176 -

carrier, any servant or agent of the actual or the contracting carrier is, pursuant to the Montreal Convention, entitled to avail themselves of the conditions and limitations of liability applicable to the air carrier of which they are the servants or agents. In relation to the carriage performed by the actual carrier, the aggregate of the amounts recoverable from that carrier and the contracting carrier, and from their servants and agents acting within the scope of their employment, shall not exceed the highest amount which could be awarded against either the contracting carrier or the actual carrier under the Convention, but neither the contracting nor the actual carrier shall be liable for a sum in excess of the limit applicable to that person (Article 44).

2. Limited liability of combined carriage

In the event of combined carriage performed partly by air and partly by any other mode of carriage, the provisions of the Convention shall apply only to the carriage by air, provided that the carriage by air qualifies as international and the aircraft performs the carriage for reward [Article 38(1)]. Different rules are applicable to carriage by other sub-branches of transport.

If for technical or meteorological reasons or because of strike, the aircraft does not land at its destination and is not capable of continuing its journey, or the flight is cancelled, the air carrier may find an alternative mode of carriage (land) within a certain distance, if it cannot perform carriage by air. For instance, if the goods are transported from Vienna (VIE) with transshipment in Frankfurt (FRA), but the flight to Frankfurt is cancelled, the connecting flight can be reached by truck or train. This mode of transport does not qualify as air carriage, since the Convention by its own vigour (exproprio vigore) does not encompass other transport sub-branches. Thus, the damage caused in this period of transportation is adjudged pursuant to the rules of national law pertaining to the sub-branch of transport concerned.

At the same time, the Convention facilitates that, in the case of combined carriage, the contracting parties insert conditions relating to other modes of carriage in the document of air carriage, provided that the provisions of the Convention are observed as regards the carriage by air [Article 38(2)]. Upon the carriage of cargo, if the consignor and the carrier of the cargo stipulate in advance in the air waybill that the carrier will take recourse to means of land (on the surface on public road or railway) or water transportation (ship) for certain sections, these modes of carriage will be governed by the rules of the Convention.[35] If the parties do not stipulate in advance the possibility of the use of other means of transportation in the air waybill, the period

- 176/177 -

of the carriage by air will not extend to any carriage by land, sea or inland waterway performed outside the airport.

In the Siemens versus Schenker International case,[36] the plaintiff demanded that the defendant indemnify the damage to its manufactured products caused during their consignment. The electronic products manufactured in Germany were consigned to Australia by the Schenker Logistics Company. The cargo arrived at the airport in Melbourne (MEL), from where it was delivered by lorry to the warehouse 4 kilometres away and stored there temporarily. However, during the consignment of the cargo back to the airport, a part of the products, owing to the fault of the lorry-driver, fell from the back of the truck, and significant damage was caused to the cargo. The carriage was deemed international; therefore, the case needed to be adjudged pursuant to the provisions of the Convention. Nevertheless, the damage was caused during the section performed outside the area of the airport and so the Convention was not applicable. However, carriage by air can be extended in writing in the air waybill to consignment by other means of transportation for loading, delivery or transshipment. In such a case, the Convention is governing, because this section is also deemed to be air carriage. Therefore, the Court established that the limited liability indicated in the air waybill had been extended by the parties to the whole carriage; thereby to consignment to the warehouse as well. Therefore, according to the rules of the Convention the carrier, sustaining its limited liability, was liable on the basis of weight for the damage. Finally, the carrier made a payment of 74,680 USD as damages calculated with 20 USD per kilogram [the real damage was valued at 1.7 million Australian Dollars (AUD)].

Essentially, the liability of the air carrier is maintained during the time of storage in the warehouse as well if the disposal of the cargo in the warehouse is deemed to be part of the carriage by air by the contracting parties. The lawmaker extends the section of air carriage to when, upon the performance of a contract for carriage by air, for the purpose of loading, delivery or transshipment, carriage takes place using other modes of transport. Any damage caused in this period of time is presumed, unless there is proof to the contrary, to have been the result of an event which took place during the carriage by air.[37] If a carrier, without the consent of the consignor, substitutes carriage by another mode of transport for the whole or part of a carriage intended by the agreement between the parties to be carriage by air, such carriage by another mode of transport is deemed to be within the period of carriage by air [Article 18(4)].

- 177/178 -

3. Limited liability of successive carriage

In successive air carriage, different air carriers in their own right perform the carriage consisting of several sections under their own flight number. Carriage in that case, pursuant to the Convention, is deemed to be one undivided carriage. Its condition is that the contracting parties regard the carriage as a single operation, whether it had been agreed upon under the form of a single contract or of a series of contracts. Successive carriage does not lose its international character merely because one contract or a series of contracts are to be performed entirely within the territory of the same State [Article 1(3)].[38]

For instance, the Air France (AF) airline delivers the cargo on the Paris - Moscow - Vladivostok (CDG-SVO-VVO) route. In the Russian Federation, it is not possible to implement a domestic flight using an aircraft of a foreign airline, since the exercise of the right of cabotage (8th and 9th Freedoms of the Air Rights) is not permitted. Therefore, the cargo on the domestic route between SVO-VVO is transported on an Aeroflot (SU) aircraft. All sections of the transportation, including the domestic one, qualify as undivided carriage considered to be a single operation and, as international carriage, it is subject to the scope of the Montreal Convention (Russia ratified it in 2017).

However, if the original route was only Paris - Moscow and the consignor decided that the cargo which was delivered to Moscow should be transported to Irkutsk (IKT) and makes another contract with the same air carrier or its agent in order to have the goods carried from Moscow to Irkutsk, this separate transport would qualify as domestic carriage; therefore, it would not be subject to the scope of the Montreal Convention.

In the case of carriage to be performed by various successive carriers, each carrier which accepts cargo is subject to the rules set out in the Convention. The air carrier under the supervision of which the carriage is performed is deemed to be one of the parties to the contract of carriage insofar as the contract deals with that part of the carriage which is performed under its supervision [Article 36(1)].

Upon successive carriages as regards cargo, the consignor will have a right of action against the first carrier, and the consignee who is entitled to delivery will have a right of action against the last carrier. Essentially, each may take action against the carrier which performed the carriage during which the destruction, loss, damage or delay took place. These carriers will be jointly and severally liable to the consignor or consignee [Article 36(2-3)], so far as the consignor or the consignee does not take action for various reasons, and the entity of the owner of the cargo is different from these obligees, since the lawmaker does not expressly designate the owner as a person

- 178/179 -

entitled to take action; they may only sue for damages if they can prove that a real legal relation prevails with any of the parties concerned.[39]

4. Limited liability of the servant or agent

A lawsuit may be filed vis-à-vis the servant or agent of the air carrier for causing damage regulated under the Convention. In that case, the servant or the agent, if they can prove that they acted in the scope of their employment upon the occurrence of damage, shall be entitled to avail themselves of the conditions and limits of liability which are applicable under the Convention to the carrier whose servant or agent they are (Article 43).

The aggregate amounts recoverable from the carrier, its servants or agents in that case shall not exceed the limits stipulated under the Convention. Thus, the plaintiff cannot claim more compensation from the servant or agent than from the air carrier itself. At the same time, if it is proved that the damage resulted from an act or omission of the servant or agent done with intent to cause damage or done recklessly and with knowledge that damage would probably result, that prevents them from invoking the limits of liability in accordance with the Convention [Article 30(1-3)].

IV. Exoneration of the air carrier from liability

The Convention provides that, in the carriage of cargo, the liability of the air carrier in the event of destruction, loss, damage or delay is limited, unless the consignor, upon transferring the package to the carrier, has made a special declaration of interest in delivery at destination for the excessive value and has paid a supplementary sum charged for this [Article 22(3)].

The air carrier has strict (absolute) liability in the event of damage or delay during carriage by air. It means liability is imposed on the air carrier without regard to fault. Upon the exoneration of the air carrier, the burden of proof is placed on the air carrier [Article 21(2)]. As the cargo is not under the supervision of the claimant, the air carrier "in charge" is in the best position to report on what had happened to the cargo. The claimant (plaintiff), the entity of the consignor, or the shipper (the freight forwarder) is obliged to declare and prove the actual damage in detail, and furnish relevant and specific information about the damage and delay. If necessary, the claimant has to notify the carrier in a preliminary notice and they can specify their claim in this document.

- 179/180 -

If the applicability of the Convention has been established, the meritorious adjudication of the legal case commences. The court examines the extent to which the air carrier is liable for the damage and whether there are any circumstances on the basis of which it can be exonerated. It is important to highlight that the air carrier, as a matter of course, does not have to indemnify damage deriving from, the claimant's own fault; that is, the damage caused or contributed to by the negligence or other wrongful act or omission of the person claiming compensation, or the person from whom the claimant derives their right to claim compensation. In this way, the air carrier shall be exonerated from liability to the extent to which such (contributory) negligence or wrongful act or omission caused or contributed to the damage (Article 20).[40]

So far as no own fault prevails, and the responsibility of the claimant cannot be established, the air carrier shall be liable, provided that further reasons for exoneration expounded below do not prevail. If, on the basis of the provisions of the Convention, the air carrier is not liable since it exonerates itself, or its liability on the basis of the provisions of the Convention is not established, the air carrier can no longer be called to account in the concrete case in any other way. This implies that, in the specific case, the plaintiff cannot enforce their claim for damages vis-à-vis the air carrier pursuant to national law or any other legal regime. The institution of exclusive remedy is a special protective stronghold which, to all intents and purposes, provides ultimate protection for the air carriers of the States Parties.

In the carriage of (passengers, baggage) cargo, any action for damages, however founded, whether under the Convention or in contract or in tort or otherwise, can only be brought subject to the conditions and such limits of liability as are set out in the Convention without prejudice to the question as to who are the persons who have the right to bring suit and what are their respective rights (Article 29). This intricately formulated but all the more significant rule has been transplanted into the Montreal Convention from the Warsaw Convention without substantial changes; therefore, a considerable amount of case-law pertaining to exclusive application is available. Exclusive remedy means that if the Convention is applicable in the given case but, pursuant to its provisions, the award of compensation is not substantiated and, as a consequence, the liability of the air carrier is null and void, this claim cannot be enforced; that is, the air carrier cannot be sued on any other legal grounds proceeding from national or other law.[41] It does not mean that the consignors do not have an opportunity to enforce their rights solely because they cannot claim compensation from the air carrier itself any longer. The claimants may in their own right bring civil legal or criminal legal action vis-à-vis the tortfeasor third party pursuant to the rules of national law.

- 180/181 -

1. Exoneration from indemnity for damage caused to cargo

The air carrier is not liable for damage to the cargo if and to the extent it proves that the destruction, loss of or damage to the cargo resulted from one or more of the following:

- inherent defect, quality or vice of that cargo;

- defective packing of that cargo performed by a person other than the carrier or its servants or agents;

- an act of war or an armed conflict;

- an act of public authority carried out in connection with the entry, exit or transit of the cargo [Article 18(2)].

The air carrier's liability for damage to cargo is limited unless the consignor has made, at the time when the cargo was handed over to the carrier, a special declaration of interest in delivery at destination and has paid a supplementary sum to the air carrier. In that case, the carrier will be liable to pay a sum not exceeding the declared sum. The air carrier shall not be liable if it proves that the sum stated in the declaration does not correspond to the facts, since it is greater than the consignor's actual interest in delivery at destination [Article 22(3)]. In the latter case, the extent of indemnification is adjusted to the weight of the cargo, not to the value stated in the declaration.

2. Exoneration from the indemnification of damage caused by delay

The carrier shall not be liable for damage occasioned by delay if it proves that

- it and its servants and agents took all measures that could reasonably be required to avoid the damage; or

- it was impossible for the air carrier and its servants and agents to take such reasonable measures (Article 19).

Under the Convention, the lawmaker prescribes that the air carrier, its servants and agents merely take all measures reasonably required for the avoidance of damage, in contrast to the more rigorous requirement of the Warsaw system, in which the basic expectation was taking all the necessary measures. There are situations when the air carrier cannot fulfil its obligation, since its servants and agents are unable to avert the unforeseeable, external and compelling circumstance or impediment and its consequences. On such occasions, it is impossible to take appropriate measures because one is powerless vis-à-vis superior power (vis maior), such as wars and emergencies, natural disasters (volcanic ash, earthquakes, tornados), catastrophes, and even strikes.[42]

- 181/182 -

It is worth emphasising that the Convention does not mention the legal institution of vis maior, hence it entrusts its relevant judgment of the case to national courts.

The eruption of the Icelandic Eyjafjallajökull volcano and the volcanic ashes hanging over a large part of Europe created severe chaos in air traffic in April 2010. In a matter of minutes, the natural phenomenon impeded the journey of more than ten million people and at least 100,000 flights were cancelled. Consequently, the air transport industry of the world suffered a loss of approximately 1.7 billion USD. The insurance companies, with reference to a situation of vis maior, denied the fulfilment of claims for damages.[43] The air carriers took all reasonably necessary measures in the interest of the prevention of damage by not taking off, therefore, their exoneration from liability for damage was deemed justified.

A further important aspect of the exoneration of the air carrier in the event of delay is that the delay should be justified. If the flight is performed on another airplane by the air carrier since the change of aircraft is justified for technical or flight safety reasons, its position based on the requirement of flight safety despite the delay remains defensible, if it can prove that it took all reasonably necessary measures to prevent damage. Beyond taking the reasonably necessary measures, the air carrier needs not only to do its utmost to remedy the situation (the prevention of damage), but also to prevent any delay. If the delay had been preventable or the recklessness and negligence of the air carrier underlie the technical failure, and the fault is repaired in vain, the air carrier cannot exonerate itself, and therefore it shall be wholly liable.

A further requirement of the exoneration of the air carrier from liability for delay is that the consignor does not contribute to the avoidance of delay. If the consignor does not follow the instructions of the air carrier and contributes to occasioning the damage, for instance, upon loading the rest of the cargo, it does not arrive in time and the goods miss the flight as a consequence, the consignor may not sue the air carrier since the delay does not occur due to the fault of the air carrier.

V. Dispute resolutions

The parties to the contract of carriage of cargo may agree that their dispute will be settled by arbitration. Arbitration organised by the parties is increasingly widespread, which is due to the claim that such disputes are resolved rapidly and efficiently by competent persons proficient in the subject-matter. The decision is made secretly at a closed session, and it is legally binding in the first instance; the opportunity for legal

- 182/183 -

remedy is very rare. The parties may determine the rules of procedure flexibly; they can decide on the language and place of the proceedings and the persons of the arbitrators.

The parties to a contract of carriage of cargo may stipulate, exclusively in cases of the legal relation of the carriage of cargo, that they shall settle any dispute arising with respect to the liability of carriage by way of arbitration.[44] The clause needs to be made out in writing. The clause or agreement on arbitration contains the following provisions mandatorily:

- The arbitration proceedings shall, at the option of the claimant, be conducted in the territories concerned in compliance with the Convention.

- The arbitrator or the arbitration tribunal shall apply the provisions of the Convention during the proceedings (Article 34.).

The scope of arbitration does not encompass accidents sustained by the person of the passenger; therefore, arbitrators may be elected only in relation to the first four fora of jurisdiction [Article 33(1)].[45]

VI. Conclusion

The majority of the provisions of the Montreal Convention pertain to the carriage of cargo.

The lawmaker meticulously establishes the liability system of the triangular legal relation; however, from the viewpoint of liability for damages, it does not place emphasis on the carriage of cargo, for which it does not guarantee the rights which are due to the passenger and their baggage. The cargo is deemed to be reproducible and replaceable in the case of its damage, loss or destruction; therefore, the legal protection of goods is not so important as that of the person in the event of an accident or their personal belongings in the case of damage to them. Therefore, for damage caused to cargo, the air carrier's liability is limited to an amount of 22 SDR per kilogram, which cannot be broken through, as opposed to the unlimited liability in the case of accidents sustained by persons and to the breakable limited liability for damage to baggage. Nonetheless, the regulation of the carriage of cargo has not lost its significance; surely, the system of liability for damage was formulated so that it encourages the consignor of the cargo to purchase supplementary insurance, make a special declaration of interest in delivery at destination and protect their valuables and assets with all available instruments. The safety of the carriage of cargo, and its adequate legal and financial protection undoubtedly impacts our life. The carriage of cargo is a factor of increasing

- 183/184 -

value; namely, the labour and energy invested in the service of shipment are integrated into the price of the shipped products, therefore, the consumer price of each product includes the cost of carriage, which entails on average a financial surplus of 30-40 per cent in the price. Furthermore, the system of rules regulating the carriage of cargo is extraordinarily complex. The Montreal Convention provides scope for national law, guiding case-law and the IATA resolutions, because it intends to unify the system of the liability of air carriers for damage only regarding the most important issues. At the same time, it will be capable of establishing uniform regulation worldwide only if all, but at least as many states as possible, accede to the Convention. The Montreal Convention for the Unification of Certain Rules for International Carriage by Air unifies merely the most significant rules; consequently, national law, supplemented by the rules of the industry proceeding from the character of air transport, has a prominent role in guaranteeing comprehensively the legal protection of the performers of the carriage of cargo and chiefly of the persons utilising the service. ■

NOTES

[1] ICAO Doc 9740 Convention for the Unification of Certain Rules for International Carriage by Air. Montreal, 28 May 1999.

[2] In 2019, 4.5 billion people travelled by airplane, while in 2018 there were more than 4 billion. Apart from the 3,780 airports for scheduled flights, a further 38,000 airports are available for civil, state (military) and commercial transport. The key performers of the air transport industry produce 3.5 per cent of the GDP of the world, which implies an estimated economic potential of 2,700 billion dollars annually. Aviation Benefits Beyond Borders. Executive Summary. ATAG Report, Facts and Figures, September 2020., www.atag.org (Last accessed: 31 December 2020).

[3] IATA, Annual Review, 2020., https://www.iata.org/contentassets/c81222d96c9a4e0bb4ff6ced0126f0bb/iata-annual-review-2020.pdf (Last accessed: 31 December 2020) 11., 18.

[4] Of the total transport of goods in world trade, the air transport sector ships nearly 52 million tons of products annually. By weight, this quantity of products accounts for barely 0.5 per cent of the total shipment of goods in world trade. However, the value of goods shipped by air accounts for 35 per cent of the total value of goods shipped in the world. These numbers suggest that goods of higher value and of smaller volume, as well as time-critical goods are worth shipping by air. Aviation Benefits Beyond Borders. Executive Summary. ATAG Report, September 2020.

[5] P. S. Dempsey and M. Milde, International Air Carrier Liability: The Montreal Convention of 1999, (McGill University Centre for Research in Air & Space Law, Montreal, 2005) 67.

[6] Aya v. Lan Cargo, S.A. (1:l4-cv-22260) District Court, S.D. Florida, 18 September 2014.

[7] A Latin expression meaning on its first encounter or at first sight. It is based on first impression; accepted as correct until proved otherwise.

[8] The active members of the IATA are the acceded airlines which operate scheduled flights on international routes. Today more than 290 airlines, representing 82% of global air traffic, are members of the IATA. IATA, Annual Review, 2020. 5.

[9] IATA, Recommended Practices 9074-40, Cargo Services Conference Resolutions Manual (CSCRM), (40th ed., 2020).