András Schlett: On the Horns of a Dilemma - Redesigning the Pension Systems in Europe (IAS, 2006/3-4., 127-143. o.[1])

I. Economic, demographic and institutional background

A worldwide consensus has emerged that social security is at a critical juncture in its development and that an objective and broad-based discussion, involving all of the social partners, is needed to redefine social security. The reasons are many and complex but among the leading causes are the following:

Population ageing: The ageing of populations is a general phenomenon in the most of the industrialised world. Declining birth rates and longer life expectancy are the main factors contributing to this process. As a result, the ratio of elderly people those of working age (often referred to as the 'elderly dependency ratio') is forecast to increase substantially in the medium to long term, with a particularly steep increase foreseen after 2020, at which point the largest cohorts of the population will start to reach retirement age. Birth rates in industrialised economies have been declining substantially over recent decades. Current rates - an average of around 1,5 children per woman - are too low to allow for a natural replacement of the population and a stabilisation of its structure. Longevity is another important determinant of population ageing. Largely on account of improved medical standards and health care, life expectancy at birth of men in euro area countries has increased from around 67 years in 1960 to 76 years in 2000. For women, the increase was from 73 to 82 years.[1] In 1960, the number of older people was about 22% of the number of employees. That is, for every older person there were over 4 employees to provide support. Currently, there are about 3 employees for each older person, and after 2010, the trend changes sharply. By 2030, the size of the older population will grow to 50%. That is, there will be only two employees for every older person.[2] So the potential fiscal and broader economic consequences of population ageing are a serious cause for concern.

- 127/128 -

Old-age dependency ratio (%)

(Population older than 64 to population at age 15-64)

Dominance of market-oriented thinking: The close of the 20th century is strongly marked by the triumph of market-oriented approaches over other socio-economic models. The very notion that social protection can be in harmony with or even a positive factor in promoting economic growth has been called into question. The critics of public pension provisions, in particular, have marshalled a growing number of supporters, in favour of funded individual savings' accounts by arguing that such schemes are able to create new savings and thereby foster higher economic growth. We are daily reminded of the fact that the debate about the future of social security is not being framed by social policy experts and specialists, who are the most knowledgeable about the operations and results of social security programmes, but rather by the critics, particularly by those interested less in social protection than in fiscal policy and diminishing the role of the state.

Globalisation of national economies: Globalisation has significant implications for social protection. Countries with the most open economies are most exposed to the vicissitudes of global markets, and research shows that they are the countries which have the highest social security expenditure. Fewer and fewer countries can stand apart from worldwide economic trends. The growing divisions of labour in the world's market place affects virtually every country. Industries which were formerly the mainstay of a national economy have within a few years been made obsolete by economic developments on the other side of the globe. Capital moves at incredible rapidity, as witnessed by the continuing economic crisis in Asia, taking advantage of currency fluctuations and brighter prospects for investment returns elsewhere. Even highly developed industrialized nations are unable to defend their economic interests on their own and are obliged to seek the assistance of the international financial institutions. It is thus hardly surprising that growing doubts are being expressed about the capacity of governments to decide on the kind and level of social security protection to be provided to their populations in a world where they are less and less in control of their own economic and financial destinies. One of the

- 128/129 -

striking realities of globalisation is that while governments are still able to tax labour, they have a far more difficult time taxing the ebb and flow of international investments and financial transactions.

Loss of confidence in the ability of governments to plan for the future: Perhaps the gravest charge raised against social security at the end of this century relates to the lack of confidence, in the ability of nations to take collective and democratic decisions to ensure economic prosperity while, at the same time, maintaining a degree of social justice - solidarity - among the members of the population. The 'crisis of legitimacy' of the public sector is not restricted to any particular country or region of the world. It may be closely related to the globalisation of the flow of ideas and technology, but private solutions are routinely advocated instead of public solutions. State institutions are constantly accused of inefficiencies and poor service which the private sector could supposedly overcome.[3]

Convergence of the social security systems in the European Union: The differences between social security systems significantly have influence on the European integrational process. The differences between the EU-countries' social security's quality can hinder the economical integration as well. Two process can be observed within the area of the social security in the EU. On the one hand the number of common provisions of law about social security have increased. On the other hand these common provisions of law don't serve only exclusively the economical integration. However it endeavour to improve stressed continuously the common civils' social security. Harmonisation of social security systems didn't realise, but in spite of the rejection, defined social purposes and politics' coordination could be observed. The concept of the convergence of the national social security systems has raised from the beginning of the '90.

II. Pension systems in Europe

Lack of the unified regulation, pension systems of the member states show a very varied picture. In the terminology of the European Union, pillars mean something else in comparison with the Hungarian one.

Pension schemes are traditionally classified into the following three categories, although the variations are sufficiently large.

1. Publically managed pension schemes with defined-benefits and pay-as-you-go finance, usually based on a payroll tax. They are mandatory for covered workers. In most countries coverage is (near) universal. Variations involve partial advance-funding and notional individual accounts. In some countries, there are two quite different public schemes: an anti-poverty programme (often funded out of general revenues and not related to work experience); and an earnings-related programme designed to prevent major drops in living standards on retirement. The anti-poverty programme is often known as a flat-rate pension, even though it some times means-tested.

- 129/130 -

2. Occupational pensions are privately managed and offered by employers to employees. Within this category of funds there is a trend from defined-benefit and partially funded schemes towards defined-contribution schemes.

3. Personal pension plans in the form of saving and annuity schemes. These schemes are normally voluntary and based on fully funded defined-contribution plans. Tax incentives encourage the development of these plans, although at present their share of total income in old age is relatively small but growing.

It was recognised that there is a vary widely from country to country and cannot be readily compared using traditional concepts such as three pension schemes. The following approaches can help us in our orientation: management (public-private); finances (funded-unfunded); participation (mandatory-voluntary); what is definite? (benefit-contribution); risk (political-economical) etc.

| Approach | Formal | Informal | ||

| Management | public schemes | Occupational programmes | Private savings | Familiar |

| Finances | unfunded | mixed | funded | private |

| Participation | mandatory | mixed | mixed | social sanctions |

| Redistribution | yes | yes | Little part | Family |

| What is definite? | benefits | mixed | contributions | Within family |

| Kind of risk | political, social | economical, social | economical, investment | familiar |

As well as table shows, the given idea-pairs actually are not dichotomies, yes or no alternatives. These are rather extreme points of a continuous scale with many kinds of solutions between the two limits. According to this, surely cannot be ordered to a good and a bad subsystem.[4]

In almost all advanced economies, the social security pension scheme is by far the largest provider of old-age benefits. It is usually a defined benefit scheme, providing benefits which are related to previous earnings and/or benefits of a flat-rate amount. In most cases the scheme is contributory, but a few countries have a universal, basic pension scheme financed out of taxation (usually but not always) in addition to an earnings-related scheme. All countries have some means-tested arrangements, either as part of their general social assistance scheme or in the form of a special scheme for pensioners, to supplement the incomes of those whose pension entitlements are insufficient to meet an officially determined minimum level.

The generosity of the social security pension schemes varies substantially from one country to another: benefits vary as a percentage of covered earnings, and covered earnings themselves vary (as a percentage of national average earnings). These differences are linked to the varying importance of private pension provision from one country to another. In some countries, where private occupational pensions have existed for a long time, the pension industry has exerted influence to limit the role of

- 130/131 -

the social security system, which has in turn encouraged the further development of occupational schemes. On the other hand, the existence of generous social security pension schemes in other countries has discouraged or rendered unnecessary the creation of private occupational schemes, except for small numbers of very highly paid staff.

Characteristics of public pension plans in some European countries

| Country | Statutory retirement age | Average retirement age | Indexation scheme | Public expenditure on pensions in relation to GDP (2000) | ||

| Men | Women | Old age | Early retirement | |||

| Austria | 65 | 60 | 64,1 | 57,9 | Net wages | 14,9 |

| Belgium | 65 | 63 | 63,7 | 55,6 | Prices | 12,0 |

| Finland | 65 | 65 | 64,5 | 60,4 | Wages/prices | 12,8 |

| France | 60 | 60 | 58,8 | - | Prices | 13,3 |

| Germany | 65 | 65 | 62,6 | - | Net wages | 12,0 |

| Ireland | 66 | 66 | 62,0 | - | Discretionary | 5,4 |

| Italy | 65 | 60 | 61,4 | 55,6 | Prices | 15,0 |

| Luxembourg | 65 | 65 | - | - | Wages/prices | 12,6 |

| Netherlands | 65 | 65 | 65,0 | 60,0 | Wages/prices | 11,9 |

| Portugal | 65 | 65 | 65,8 | - | Discretionary | 9,5 |

| Spain | 65 | 65 | 65,3 | 60,9 | Prices | 10,6 |

Source: ECB Monthly Bulletin. November 2006.

In most countries private occupational pensions play little part in providing retirement income. They have an important role in only about a dozen high-income countries, in particular the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom in EU - and even there private pensions are less important than social security benefits for most retirees. Some countries, such as Switzerland, have made these schemes a mandatory supplement to the social security scheme for all employees. In others, such as France, they are not only mandatory but are highly coordinated, both for financial purposes and in order to ensure continuity of coverage when workers change employer. Most private occupational pension schemes are advanced funded, but the French complementary schemes and the German book reserve schemes are important exceptions.

The role of the State in relation to private pension schemes varies from one country to another. Governments recognize an obligation to regulate these schemes. This may mean laying down and enforcing general principles, such as joint management by employers' and workers' representatives, and leaving most of the details to be agreed by the two parties, as in France. Or it may mean formulating and enforcing complex and voluminous prudential regulations, as in the United Kingdom.

The State will usually wish to facilitate private provision for old age. One aspect of this is ensuring through regulation that private pension schemes are a safe vehicle for retirement savings. Another aspect may be to subsidize the contributions that

- 131/132 -

workers and employers make to these schemes - a function, which is typically (but not necessarily) undertaken through the tax system. A third aspect may be to encourage private provision by providing pension funds with various types of insurance or guarantees, and with indexed bonds in which they can invest pension assets.

The State may go one step further and make it mandatory either for the enterprise to provide an occupational scheme for its employees or for workers themselves to contribute to an approved pension fund of their choice. Private pension is also regulated and encouraged in the case of the self-employed, but for them it is not made mandatory.[5]

The choice between public and private pension provision is influenced to a very large extent by political philosophy and by the confidence which people have in the government and in the capabilities of the public system. In recent years, governments themselves in various countries have promoted a greater role for the private sector, by expressing doubt about the financial sustainability of existing public systems.

II. Pension financing

Pensions constitute the largest element of social protection expenditure in most countries, usually exceeding the amount spent on health care. Nevertheless, the percentage of GDP devoted to pensions varies enormously between countries. The cause the relative cost of financing pensions is tending to rise, as:

- pension systems are maturing: this means that the number of people drawing benefits is rising and the level of their entitlements is increasing, due to their longer periods of coverage; and

- the population is ageing, thanks to falling birth rates and, to a lesser extent, greater life expectancy.

These are long-term trends, which have been duly recognized over the years; inevitably, they affect the relative levels of pension system revenue and expenditure. Labour market developments are also important for pension financing, namely: employment and unemployment trends; labour force participation rates of people of working age; and informalization of the labour market. The importance of these non-demographic variables is vividly illustrated by comparing Italy and Sweden. Although its share of elderly in the population is larger, Sweden has 2,5 active contributors for each pensioner, and Italy now has only one active contributor per pensioner. In countries, which have experienced high rates of unemployment, early retirement has been a widely used mechanism to remove excess labour from the labour market. Governments concerned about the medium-term political fallout from high unemployment rates where often favourably disposed to early retirement arrangements - particularly where they considered it as a way to provide jobs for unemployed young people. Employers, keen to shed labour without provoking industrial unrest, where generally enthusiastic, particularly when they did not have to foot the bill themselves. And workers, especially manual workers, often wished to retire early while still in relatively good health. Early retirement took a variety

- 132/133 -

of forms: more flexible provisions in the pension system (in some cases a lowering of the standard pensionable age); less rigorous treatment of applications for disability benefits; introduction of special early pension arrangements co-financed by employers and government; and payment of extended unemployment benefit to workers over a certain age. In recent years, governments have been much less disposed to pursue this approach, having understood its serious long-term financial implications.

The retirement decision involves complicated calculations, assuming that the worker is in a position to choose - which in recent years has often not been the case. Continuing work brings earnings and possibly enhanced pension benefits; retirement may bring current benefits and possibly reduced future benefits (if there is an actuarial penalty). These calculations may be summarized in terms of their effect on net social security wealth, defined as the expected discounted value of the stream of benefits less contributions. In many cases, a person who started work at age 20 derived no gain at all in terms of pension form continuing to work beyond age 55.[6]

It is visible, that current public pension systems, tax systems and social programmes interact to provide a strong disincentive for workers to remain in the labour force after a certain age. Removing these disincentives, perhaps even providing positive incentives to work longer, coupled with effective steps to enhance the employability of older workers, could make an important contribution to sustaining the growth of living standards.[7]

IV. Budgetary consequences

In the pay-as-you-go financed systems, the financial situation depends on the following four sets of variables: (1) contribution rates on wages, (2) replacement rates, i.e. average pensions in relation to average incomes, (3) the support ratio, i.e. the number of contributors to the pension scheme in relation to the number of recipients of public pensions - which largely depends on effective retirement ages, labour force participation and employment rates - and (4) budgetary transfers.

The most basic method for calculating potential future trends in pension expenditure assumes that per capita public pension transfers will grow in line with per capita real income and applies this assumption to demographic forecasts. The pension expenditure in relation to GDP will increase very substantially in most euro area countries in the period from 2000 to 2030. This increase could be in the order of magnitude of 5 percentage points of GDP or even more. Under current arrangements, the net present value of the balance between pensions and contributions would be up to twice the level of GDP in some countries. This compares with - and effectively adds to - outstanding general government gross dept levels, which, on average, are still very high within the euro area.

All in all, complex and potentially undesirable economic effects may result from the ageing of the population, in particular against the background of comprehensive PAYG pension systems. According to simulations of future fiscal and economic

- 133/134 -

trends in a general equilibrium setting, taking into account various effects of population ageing and the respective links between economic variables, a continuation of current policies would result in a substantial loss of output in the EU as a whole over the next 50 years. Population ageing would lead to a noticeable lowering of the annual GDP growth rate and would be detrimental to the international competitiveness of the EU, as well as to the living standards of its inhabitants. Such developments would add considerably to the direct financial burdens which population ageing is already imposing on public finances and the sustainability of fiscal policies.[8] These results imply that policy adjustments are urgently needed.

V. Assessment of current pension reforms

Forthcoming population ageing problems will be unprecedented in terms of their quantitative impact. Awareness of the fiscal and economic risks implied by these developments has motivated debates about the structure of public transfer schemes and has led to the gradual implementation of pension reforms in many countries. Some states had already set their systems on a sounder financial footing in the past.[9] Many countries are in the process of phasing in changes to their pension systems or have decided on changes but have not yet started the implementation phase. Reforms differ from one country to another but will generally result in lower pensions and higher contribution rates. In general, two variants of pension reform have been extensively discussed: (I) the adjustment of existing public pension schemes with regard to the structure of benefits and contributions (often referred to as 'parametric reforms'); and (II) more fundamental changes in pension schemes towards funded systems which base future benefits on accumulated assets ('systemic reforms'). In practical policy-making, combinations of the two variants have often been proposed.

VI. Parametric reforms

A relatively small increases in contribution rates or budgetary transfers to the pension scheme were normally sufficient in the past to restore the solvency of pension schemes in the event of increasing financial imbalances. Effective parametric pension reforms largely concentrates on different variants of lowering benefits, normally implemented gradually and mainly affecting future recipients. Basic options for lowering benefits are (1) an increase in the effective average retirement age, (2) a reduction in replacement rates and (3) a change in the indexation rules for pensions.

1. Raising pensionable age and greater flexibility

The fundamental problem posed by the so-called ageing crisis is that there will be too many pensioners and too few workers. From a budgetary point of view, higher standard

- 134/135 -

retirement ages are beneficial because they increase the number of years during which an average worker contributes to the pension system, while they also reduce the number of years during which an average pensioner receives transfers. A number of euro area countries have recently introduced or have announced a phased-in rise in statutory retirement ages.[10] It makes sense to tackle this problem by increasing the age of retirement, but only if policies are also pursued which will provide work for the millions currently excluded from regular employment. The need for greater flexibility in pensionable age is increasingly being recognised, especially for workers who have completed a high number of years in insured employment.[11]

2. Reduction in replacement rates

Replacement rates mean the value of a pension as a proportion of a worker's previous wage (sometime the lifetime wages, but usually for a specified period of years). The number of years taken as an assessment period for an individual's work history, as well as the factor determining the accrual of pension rights in relation to annual assessed income ('the accrual factor'), are key elements in characterising the generosity of a PAYG pension plan. Average replacement ratios could be adjusted by changing the accrual factors, or by extending the number of years of income taken into account in order to calculate pension entitlements.[12]

Accrual rates differ greatly between countries. In Germany and in the Netherlands, rights accrue steadily in line with contributions throughout working life. In most countries, though, rights accrue at a steady rate (though vesting period differ) only until the individual attains a maximum number of years-commonly 35-40 years-of contributions, after which there is no further increase in eventual pension rights. This implies that 55 year old workers who started to work at 20 will not increase the size of their public pensions by working a further 10 years, thus increasing the incentive to retire earlier (contributions normally continue to be obligatory even after additional rights disappear).[13]

Such reforms would lower the generosity of public pension schemes, (which is often argued to be excessive in a number of euro area countries), and would introduce stronger elements of actuarial fairness, i.e. a closer proportionality between contributions paid and the accruing pension entitlements.

3. Change in indexation rules (Linking benefits more closely to contribution)

The evolution of replacement ratios would also be altered by changing the indexation rules for pensions. When pensions are linked to prices rather than to wages, significant budgetary savings are made. There has been a trend towards linking benefits more

- 135/136 -

closely to contributions. A corollary of this type of measure has been a reduction in certain forms of solidarity in favour of persons with low or zero earnings during periods of their adult life - unemployed persons, students and homemakers, for example. Wherever it has been thought necessary to maintain such solidarity, measures have had to be taken to make it more explicit. This has served to create greater transparency but also greater inequality in old age.

A particularly close link between contributions and benefits was established by the reforms recently adopted in Italy and Sweden. Both countries have had generous pay-as-you-go pension systems, providing earnings-related pensions and covering most of the labour force. (Sweden in addition has an universal flat-rate pension, of which more later.) Under these two reforms the old schemes, in which benefits were defined as a percentage of previous earnings, are to be replaced (over a transitional period) by schemes in which a defined rate of contributions is credited to notional individual accounts. The pension will be determined by contributions throughout working life rather than by earnings in the 15 best years as in the old scheme. This new type of system has become known as a notional defined contribution. (NDC) scheme. In the Swedish case, Parliament's aim was to ensure that the contribution rate would not have to be raised in future because of changes in life expectancy at retirement.

The indexation of account balances is crucial to the adequacy of an NDC system but it is problematic for a non-specialists to understand the full implications of the different indexation methods which may be proposed. Almost all these methods have the effect of transferring some of the demographic and economic risks from contributors (workers and employers) to pensioners.[14]

Summing up the parametric reforms, it is visible that many of these kind of changes being implemented to pension systems will encourage people to work longer in life. Increased standard retirement ages, lower benefit levels, higher pension accrual rates at older ages due to longer required contribution periods for full pension would all reduce the disincentives currently embedded in public pension systems. However increases in pension contribution rates go in the opposite direction, raising the opportunity cost of remaining in work. Also, since pension reforms have typically not involved flanking changes in other benefit systems, important distortions remain. All in all, reforms to pay-as-you-go systems have only modestly reduced financial barriers to working later in life.[15]

But an increased willingness on the part of older workers to work longer will have to be matched by a sufficient number of job opportunities for the if higher unemployment is to be avoided. This, in turn will require a major change in the attitudes of firms towards hiring and retraining older workers. Since these changes will have to be reflected in wage and labour cost structures, the co-operation of the social partners could play a very useful role in this process.

- 136/137 -

A more flexible work-retirement transition is one example of 'active ageing' - the capacity of people, as they grow older, to lead productive lives in the society and economy. Active ageing implies a high degree of flexibility in how individuals and families choose to spend their time over life - in work, in learning, in leisure and in caregiving. Public policy can foster 'active ageing' by removing existing constraints on life-course flexibility. It can also provide support that widens the range of options available to individuals via effective life-long learning or by medical interventions that help people maintain autonomy as they grow older. Indeed, the available evidence shows that the more active older people are, the better the quality of life they enjoy.

VII. Systemic reforms

Given the magnitude of the forthcoming population ageing problems, more substantial changes in pension arrangements are needed and are currently under discussion in many euro area countries or already have established. The debate takes place in an environment of rapid globalisation of economies. Some correlation has been found between the increasing share of trade in GDP in recent years and a reduction in social security expenditure - which suggests that globalisation may be making it more difficult for countries to finance social protection. The increased mobility of capital has certainly made it much more difficult to tax capital, so that governments are increasingly resorting to taxes on labour and on consumption which may meet with greater resistance from voters.

It has become clear that substantial further adjustments in pension systems, coupled with reform in other areas of public finances, are now needed. Without such changes, sizeable future increases in contribution rates or in government dept or substantial cuts in benefits will endanger economic efficiency and threaten intergenerational equity. Postponing the necessary policy changes will ultimately lead to the need for even more painful measures.[16]

Therefore there is a move towards multiple-pillar systems of providing retirement income. None of the systemic reforms have affected existing retirees, or those close to retirement, because imposing a burden on those who have few means to adjust would undermine trust in the pension systems. Some of the more radical reforms will be phased in very gradually to allow sufficient time for young working to adjust the changes. In all reforms it is ultimately the younger generation mainly those who are currently less than 40 years of age, who will have to carry the bulk of the pension burden way or another.

There has already been a big increase in private savings, channelled through pension funds. It can take various forms, including occupational pensions organised along sectoral or company lines and individual retirement schemes. These are now typically advance-funded and tie pension benefits much closer to contributions than has been the practice in public schemes.

- 137/138 -

A growing reliance on private pension schemes also calls for an adequate regulatory framework, which is a precondition for maintaining the confidence of both beneficiaries and the public at large. Appropriate regulations will contribute to safeguarding beneficiaries' rights, which include inter alia non-discriminatory access to pension schemes, protection of vested rights, the implementation of provisions of transferability and the related promotion of labour mobility and the adequacy of benefits. Regulations concerning investors' protection are also critical to guard against an abuse of the system.

A shift to more advance-funding often brings with it a shift to defined contributions and a resulting strong linkage between what an individual contributes and receives. This is an important element in promoting greater choice in the decision to retire. Pay-as-you-go systems can shift their benefits to a defined-contribution basis, mimicking some of the features of advance funding. Company plans can be shifted from defined-benefit to defined-contributions. (The problem with defined-contribution plans is that they transfer risk to individuals.)[17]

VIII. Pension funds

Size, financial performance and regulation of private pension funds

Pension funds are already the key players in many financial markets and they importance seems clearly set to increase. The holdings of financial assets by pension funds have grown at a rate of 11 per cent over a decade for the OECD area as a whole the stock raising from 28 per cent of GDP in 1987 to nearly 39 per cent of GDP on average in 1996. Although there are a great variation among individual OECD countries. In many European countries pension fund assets amounted to less than a tenth of GDP in 1996; they exceed 50 per cent of GDP in the United Kingdom, the Netherlands and Switzerland.[18]

The financial rates of return on pension assets have varied significantly across countries. Over the 1967-1990 period, the average annual real total return ranged from close to zero in Sweden to close to six per cent in the United Kingdom. In a few countries the rates were no higher than the growth in average earnings (and in Sweden they were significantly tower), whereas they were significantly higher than the growth in labour income in several countries. The variability of returns across countries appears to be related to different regulatory structures and other structural factors.[19]

In the design of regulatory structures for pension supervision, there are a wide variety of options. Countries have adopted different models according to the stage of development of the private pension sector and the institutional arrangements for pension provision as well as the historical and cultural circumstances in the individual country. In most western-European countries, pension regulation and supervision are

- 138/139 -

fragmented, i.e., there is more than one agency responsible for pensions. This is a result of the gradual development of private pensions.

The regulatory regime and the extent to which regulators have to define detailed rules for pension funds' operations depend on the types of pension schemes allowed or prevalent in a particular country. If only defined-contribution (DC) schemes exist, regulation is much easier than if only defined-benefit (DB) plans or, as in most countries, both plans must be supervised. DC plans are usually fully funded (an exception is the notional DC plans which operate according to pay-as-you-go principles and are currently being introduced in Sweden and Latvia and under consideration in Poland). Therefore, issues such as determining and measuring adequate funding levels and ownership of surpluses do not apply. Until a plan beneficiary reaches retirement, DC pension plans basically operate like mutual funds, with the objective of managing the investment of assets to achieve the highest return possible for a given level of risk. If the worker purchases an annuity from an insurance company at the end of the accumulation phase, the annuity contract becomes subject to insurance supervision.

In the regulation of DB plans, a much wider range of issues need to be addressed. Since the plan sponsor, usually the employer, makes a promise to provide beneficiaries with a certain level of benefits upon retirement, regulators have to ensure that the plan's funding is adequate to meet current and future benefit obligations. The most appropriate method and the determination of the 'right' prices and interest rates to use in the valuation of assets and liabilities of pension plans, however, are controversial. The funding rules are very important not only to safeguard the participating workers' pension rights but also because they influence the investment strategies that pension funds adopt. Regulatory difficulties also arise in trying to ensure the portability of defined-benefit rights between different pension schemes when a worker transfers from one company to another. With DC plans, these problems do not exist, since workers are immediately owners of their accrued benefit rights and funds can easily be transferred from one pension scheme to another. Insurance of benefits is another issue that applies only to DB schemes: since DC schemes do not promise any benefits, the risk that the plan sponsor will default on its promise does not have to be insured against; but there are usually safeguards against fraud or mismanagement of funds in DC schemes.[20]

There are basically two different regulatory approaches guiding the investment and management of pension funds: 'asset restriction' and 'prudent person' (usually referred to as 'prudent man') investment rules. In the 'asset restriction' approach the authorities impose quantitative restrictions on the assets which can be included in pension funds' portfolios: funds may be requested to hold a minimum amount of safe assets, such as government bonds; there may be a limit on the share of foreign assets in general or assets from certain geographical areas in particular; there may be restrictions to what extent investment in non-quoted companies are permitted; etc. Under the 'prudent person' principle, quantitative restriction are not applied, but fund managers are expected to behave as careful professionals in making investment decisions.

- 139/140 -

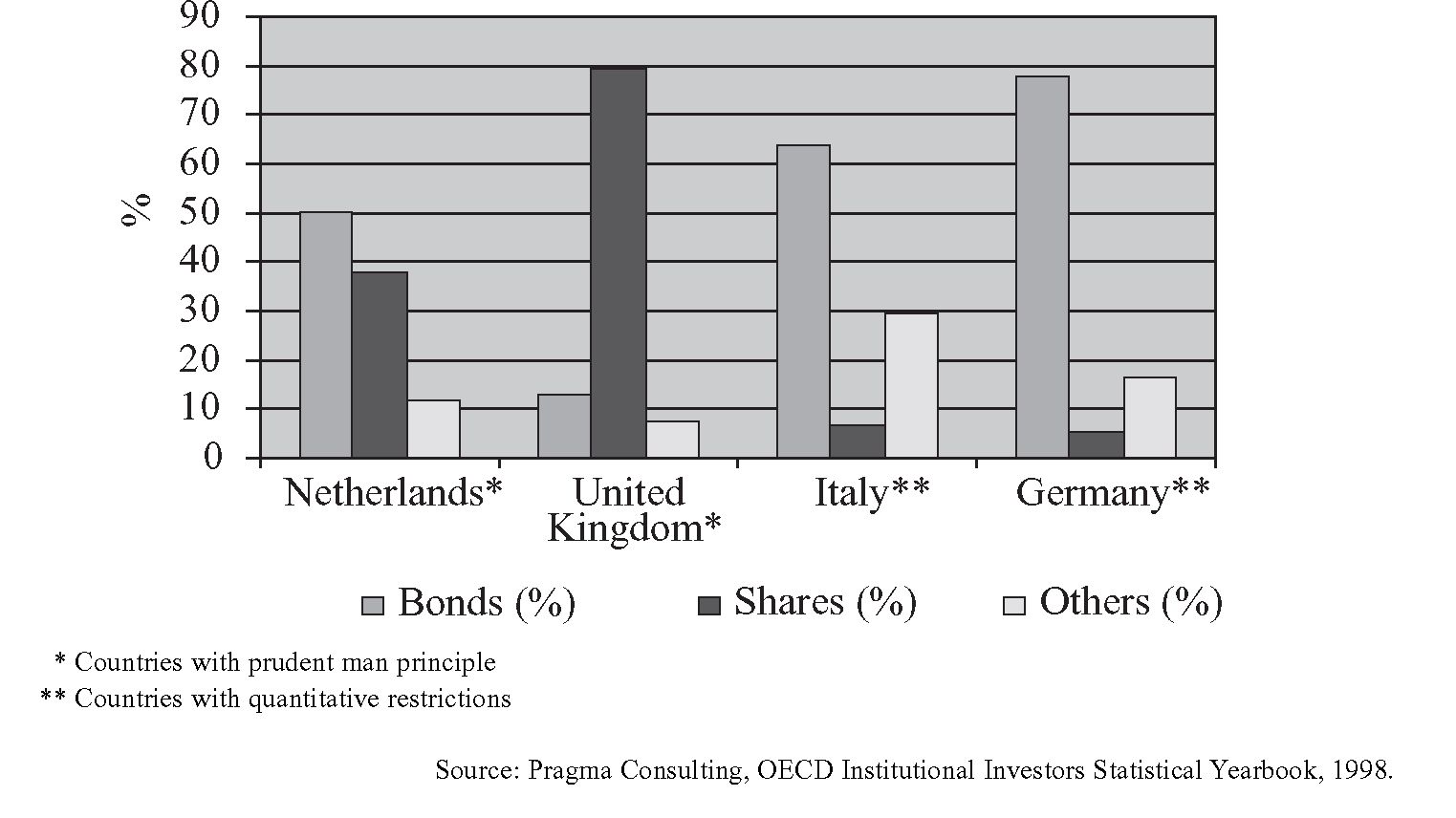

An examination of pension funds' asset composition in OECD countries with the prudent-man rule versus countries with asset restrictions shows that the former invest a higher share of their assets in equities; percentages range between 79,3 per cent in the United Kingdom(in 1996) and 38 per cent in the Netherlands. By comparing the aggregate returns on pension fund portfolios in countries that have less restrictive 'prudent person' investment rules with those of countries that have stricter quantitative restrictions, the indicates shows that pension funds' portfolio returns have been higher in 'prudent person rule' countries over the period 1967-1990. The average real returns of prudent-man countries were 3,4 per cent, as compared with 2,9 per cent in countries which applied asset restrictions.[21] However, it is important to note that these differences in returns may be the result of factors other than differences in regulatory arrangements, including macroeconomic policies, structural factors that influence economic growth (e.g. capital market segmentation, discoveries of mineral wealth, etc.) and various features of the institutional infrastructure.

Portfolio composition of pension funds' assets in selected some European countries (1997)

Sophisticated trading arrangements and investment techniques have been developed in response to the needs of pension funds and other institutional investors. The growing importance of institutional investors is generating also an increasing demand for risk-transfer techniques, which enable the investor to choose the desired combinations of return and risk. Such techniques include both securitisation, which enables the investor to transfer the credit risk as well as the market risk, and derivates, whereby market or price risk is reallocated among participants. The demand for risk-transfer

- 140/141 -

techniques has been strongly driven by the nature of the liabilities of the different types of pension schemes and regulatory requirements. For example, defined-benefit schemes and strict minimum-funding requirements have stimulated demand for hedging by pension funds. In order to minimise the costs of hedging, pension funds and life-insurance companies have an incentive to immunise their defined-benefit liabilities via an investment strategy of duration matching.

Commission Communication Towards a Single Market For Supplementary Pensions was issued in the 11[th] of May in 1999 in the European Union. (Based on Green Paper on Supplementary Pensions in the Single Market) It includes the following offers for the euro area countries:

Application of 'prudent man' principle instead of quantitative asset restriction in the investment rules; The necessity of portfolio diversification against the investment risks; Shares of one company must be maximalised within a portfolio; Introduction of a rigorous controlling systems and applications.[22]

Pension funds have the trading technology and financial muscle to move markets rapidly, thereby inducing a possible increase in short-term volatility. Increased financial instability would be welfare-decreasing when institutional investors engage in 'noise' trading or herding behaviour, leading to under- or overshooting of equilibrium prices. Moreover, recent periods with market turbulence seem to suggest that even very large financial institutions are not always willing or able to act as market makers in situations of massive imbalances between supply and demand in some markets. In these situations markets may become less liquid and more volatile, in particular the smaller ones.

IX. Concluding Comments

The picture drawn up is of a future retirement-income system that can consist of a flexible mixture of elements: pay-as-you-go and advance funded, defined-benefit and defined- contribution, public and private, mandatory and voluntary, saving and earnings. The particular combinations will reflect country circumstances. However, on balance, the demographic and fiscal pressures mean a larger role in coming years for the second element in of each of these pairs.[23]

A system of retirement provision that is based on many elements has the potential to reduce risk by diversifying across producers. A public pay-as-you-go system suffers from the risk by diversifying across producers. A public pay-as-you-go system suffers from the risks associated with uncertain demographic trends, and from the non-contractual nature of implicit pension promises. These risks are mostly absent in advance-funded private systems, but such arrangements are inevitably subject to risks associated with financial market developments and the risk of default of private funds. Indeed, each of the elements of the system has its own strengthens and weaknesses and a flexible balance among them not only diversifies risk but also offers a

- 141/142 -

better balance of burden-sharing between generations and gives individuals more flexibility over their retirement decision.

Nowadays there's a revaluation in connection with the priorities' appropriation of public incomes. In the last 70 years there was a centralization of significant incomes in the developed countries in the interest of the affirmation of social cohesion. Now it is changing influenced by market-oriented thinking approaches. The international agreements for the trade liberalization are decreased of regulation involves the extending investment-possibilities. On the other hand the range of economical effects, and the interventional possibilities of the state instruments have been decreased significantly. Some correlation has been found between the increasing share of trade in GDP in recent years and a reduction in social security expenditure -which suggest that globalisation may be making it more difficult for countries to finance social protection. The increased mobility of capital has certainly made it much more difficult to tax capital, so that governments are increasingly resorting to taxes on labour and on consumption which may meet with greater resistance from voters.[24]

The maturing of these systems and demographic and economic developments have major implications for pension financing. Governments need to seek solutions, not only through pension reforms, but also through appropriate economic and employment policies. Radical reforms which replace social insurance by privately managed mandatory retirement savings systems may solve the financing problem, but only in the long term and the cost of creating other problems.

In the discussion of the global pension reform the most significant opponent of the World Bank is the International Labour Office and the International Social Security Association. In the conceptions of the ILO and the World Bank the approaches according to the first and the third pillars are very similar. The basic contrast in connection in connection with the EU-countries is around the most significant second pillar.[25] As we've already seen (Selected recent reforms in EU), the EU-countries only in a small part submit to the offerings the World Bank (in contradistinction with the countries of Visegrád).

There is a growing recognition that privatisation is not the 'magic bullet' and that a mix of financing approaches is a prudent way of guarding against the unpredictable performance of the market and other factors which impact on the level of economic output. The role of the state in ensuring adequate retirement income is no longer contested, since even the proponents of private and funded approaches concede that the state must provide a 'decent' safety net to these who are not able to save for their old age and that the state must serve as the regulator (and some would even argue as guarantor) of privately managed pension arrangements.

The experience of the past decade demonstrates what confusion can be created and misinformation disseminated when the debate about the future of social security

- 142/143 -

is left to those who have other interests than preserving adequate social security protection. The lesson is thus that economic growth and increasing globalization does not necessarily reduce poverty or increase the social security protection of citizens. It should be noted with a certain sense of irony that at the same time as the welfare state has been called into question, the number of those living in poverty has increased in many countries around the world.

Up to this point, the debate about social security reform has focussed almost exclusively on financial questions. Solvency has been the objective which nearly obliterated discussion of any other criteria. One of the major challenges facing the social security community is to bring back to the bargaining table other criteria which are needed to ensure social justice in a changing society. Among the criteria which must be taken into consideration are:

- Intergenerational equity;

- Poverty alleviation;

- Flexibility to opt for education, employment, family care responsibilities, phased or partial retirement, lifelong learning, etc.;

- Individualization of social security rights;

- Coherence, transparency and understandability of social security policies and programme provisions;

- Consistency of social security provisions with job creation and labour mobility objectives;

- Consistency of social security with regard to work incentives and the fullest use of human resources.[26] ■

JEGYZETEK

[1] Population ageing and fiscal policy in the euro area. European Central Bank, Monthly Bulletin, July 2002. 59.

[2] Maintaining Prosperity in an Ageing Society, OECD, 1998. 122. In World Labour Report 2000.

[3] Dalmer D. Hoskins: The redesign of social security. In ISSA. 26th. General Assembly, Marrakech, 25-31 October 1998. 1-2.

[4] Augusztinovics Mária: Nyugdíjrendszerek és reformok az átmeneti gazdaságokban. Közgazdasági Szemle 7/1999, 59-60.

[5] Income security and social protection in a changing world. World Labour Report, Geneva, 2000. 124-126.

[6] World Labour Report, ib. 126-128.

[7] Maintaining Prosperity..., OECD. ib. 14.

[8] ECB, Monthly Bulletin. ib. 62., 63., 66.

[9] ECB, Monthly Bulletin. ib. 67.

[10] ECB, Monthly Bulletin. ib. 68.

[11] World Labour Report. ib. 129.

[12] ECB, Monthly Bulletin. ib. 68.

[13] Maintaining Prosperity., OECD. ib. 45-46.

[14] World Labour Report. ib. 130-131.

[15] Maintaining Prosperity., OECD. ib. 54.

[16] ECB. Monthly Bulletin. ib. 67.

[17] Maintaining Prosperity..., OECD. ib. p. 60-61.

[18] Pragma Consulting, OECD Institutional Investors Statistical Yearbook. 1998.

[19] Maintaining Prosperity..., OECD. ib. p. 65-66.

[20] Monika Queisser: Regulation and supervision of pension funds: Principles and practises. International Social Security Review, 2/1998. 41.

[21] Maintaining Prosperity..., OECD. ib. 67-68.

[22] Pénztárhírek, 5/1999. 27-28.

[23] Maintaining Prosperity., OECD. ib. 62.

[24] Botos Katalin: Gondolatok a pénzügypolitika komplexitásáról. Pénzügyi Szemle, 3/2001. 246-249.

[25] Katharina Müller: Az "új nyugdíj-ortodoxia" és ami mögötte van - a nyugdíjrendszer átalakítása Közép- és Kelet-Európában. Külgazdaság, 7-8./1999. 102.

[26] Hoskins ib. 4-5., 8.

Lábjegyzetek:

[1] A szerző assistant professor