Bence Juhász[1]: Privacy protection amid surveillance capitalism: a cross-atlantic comparative legal enquiry* (Annales, 2023., 205-231. o.)

https://doi.org/10.56749/annales.elteajk.2023.lxii.12.205

Abstract

This essay researches privacy laws related to the analysis of big data performed by global online service (GOS) corporations such as Google and Facebook. First, I expose the business model of GOS corporations, 'surveillance capitalism' and discuss its potential to undermine the dignity of individuals and the integrity of the democratic process.[1] Next, I perform a comparative legal investigation between the USA and the EU to evaluate their regulatory frameworks amid surveillance capitalism. Additionally, I propose an initiative to enhance individuals' data protection. I conclude that the current US framework is unable to provide an effective protection of data and privacy, due to the absent horizontal effect of the Fourth Amendment and its limited protective scope due to the third party doctrine. The EU regime, however, could effectively protect citizen's data amid surveillance capitalism by considering the criteria for free user consent in conjunction with tests following from consumer protection and competition law. I therefore suggest that in the US a federal legislative bill that mimics the GDPR should be passed, while the GDPR should be adjusted to accept the exploitation of User-Generated Content (UGC) data, as opposed to User-Generated Traces (UGT) data, according to the logic of the reasonable expectation of privacy test.

Keywords: Digital Privacy, Surveillance Capitalism, GDPR, Qualified Consent, Democratic Resilience, Autonomy, Exploitation

- 205/206 -

I. Introduction

While the technological revolution of the last decades enabled continuous access to information and communication, it also provided novel challenges for citizens and policy-makers to overcome. Citizens face addictive urges towards online platforms,[2] feelings of depression due to their excessive, agonistic use[3] and feelings of stress due to the relative scarcity of their attention compared to the constant overload of information online.[4] Simultaneously, a major regulatory challenge concerns the legal status attached to vast data sets produced by the users of online services and collected or rather 'aggressively hunted' by surveillance capitalists.[5] Global Online Service (GOS) provider corporations such as Google, 'the pioneer of surveillance capitalism', are in the business of commodifying private human experiences.[6] Their surveillance tools, cookies or mobile cell towers gather and translate human experiences into standardized data sets. These are consequently fed into powerful artificial intelligence neural networks where machine learning capabilities generate predictions on the potential future needs, desires and activities of agents, driven by the aim of maximizing user attention paid to the online platform.[7] The knowledge derived from these predictions is then sold to firms seeking to advertise on these influential platforms, generating the vast majority of the GOS corporations' revenue.[8] Provided the extensive analyses of rich behavioural data, the content eventually shown to users has the potential to exploit human psychological vulnerabilities, to nudge and manipulate citizens into feelings and

- 206/207 -

actions the advertising customer and the surveillance capitalists see fit.[9] Given such potent capabilities to manipulate and exploit the users of online services, the legal status attached to these big data sets and the regulatory framework that ought to control their collection, use and transfer are the focus of this normative research.

The underlying hypothesis of this essay - the empirical testing of which falls outside the scope of the study - is that by limiting the data we feed into the AI neural networks of GOS corporations, we can effectively temper the manipulative capabilities of the social networks, upon which we are so reliant upon. Consequentially, my assumption is that by taming the manipulative power of online services, we can meaningfully contribute to a greater protection of individual dignity and social cohesion amid surveillance capitalism. Therefore, the primary aim of this study is to contribute to a legal framework of data protection that (1) secures cheap and wide access to information for people combined with (2) respect for personal and collective autonomy, while (3) providing a reasonable revenue stream for innovative GOS corporations. Contributing to the development of such an 'ideal' regulatory framework is the primary aim of this thesis, motivated by ultimate objective of protecting individual dignity and social cohesion in constitutional democratic regimes.

Pursuant to these aims, I first establish the groundwork of the research. In section three, I proceed with normative arguments from liberalism and Marxism converging upon a critique calling for reforms amid surveillance capitalism. Then, I assess the (il)legitimacy of state intervention into the private contractual relationship between GOS corporations and their users. In section four, the frameworks of data protection of the USA and the EU will be scrutinized by means of a primarily doctrinal, internal[10] comparative research focusing on authoritative texts and relevant case law from the apex courts of the jurisdictions, followed by a concluding section.

The study concludes that the current US framework is unable to provide an effective protection of data and privacy, due to the absent horizontal effect of the Fourth Amendment and its limited protective scope due to the third party doctrine. However, the EU regime could effectively protect citizen's data amid surveillance capitalism by considering the requirements for free user consent in conjunction with tests following from consumer protection and competition law. Finally, I remark that a federal privacy bill, mimicking the GDPR, ought to be institutionalized in the US,

- 207/208 -

although a slight reform to the GDPR framework should be pursued, by accepting the exploitation of User-Generated Content (UGC) data, as opposed to User-Generated Traces (UGT) data. This way the tripartite aim of the 'ideal' regulatory framework would be ensured: citizens would continue with unprecedented communication capabilities, the manipulative capabilities of GOS providers would be tempered, while GOS providers would still enjoy stable revenues.

II. Groundwork

The aim of the second section is to establish and legitimize the methodological and theoretical approach of the research. Additionally, it aims to create a common understanding of key concepts that appear throughout the following sections.

1. Relevance of the project

There are several factors that justify, or indeed necessitate that scholars engage in a multidisciplinary project to examine the nature of surveillance capitalism. On the one hand, behavioural data as the raw material of surveillance capitalism produced some of the most valuable corporations of the 21st century.[11] Some even refer to data as the oil of the 21st century.[12] In turn, corporations who refuse to collect the 'surveillance dividend'[13] face significant comparative disadvantages vis-á-vis their peers. Therefore, data protection is highly relevant from the perspective of corporate competition, wealth generation and innovation. On the other hand, the collection and exploitation of behavioral data is relevant for those whose experiences are analyzed and exploited by surveillance capitalists to maximize profits. Some might be concerned by a violation of their privacy, while others by the loss of their autonomy, as data analysis enables GOS to manipulate the future feelings and actions of their users.[14]

Additionally, the social aspect of individual privacy is also concerning. Liberal democratic regimes are based on the assumption that individual citizens comprising

- 208/209 -

the sovereign power and supplying authority to its constitution[15] are autonomous agents of society capable of collectively and indirectly leading society.[16] Under surveillance capitalism the validity of this assumption is severely threatened. As humans increasingly inform themselves from online sources, nowadays increasingly the algorithms of GOS corporations determine their informational input instead of their general situatedness in the matrix of timespace.[17] This is relevant for constitutional democracy as citizens formulate political opinion on the basis of that information input. If the fundamental assumption of liberal democracy concerning the autonomy of citizens ceases to be valid, the logical hierarchy of these regimes is severely undermined. Afterall, as Jürgen Habermas put it, 'the institutions of constitutional freedom are only worth as much as a population makes of them'.[18] Are not then liberal democracies running the risk of handing over sovereign power to private corporations and undermining their own logical and moral basis? Therefore, individual privacy should also be thought of as a public good under liberal constitutionalism, the protection of which justifies the present research.[19]

2. Methodological Approach

The methodology of this enquiry is multidisciplinary in its nature. Additional to the central role that the legal perspective occupies, insights from psychology, ethics, economics and machine learning are essential in claiming that the core values of liberal democracy are under siege. As such, novel explanatory theories of modern-day capitalism such as surveillance capitalism[20] and the attention economy[21] help to understand the new method of wealth generation and means of production. Key behavioural insights revealed by social psychologists[22] identified those vulnerabilities of the human mind that are rather easily exploited by modern day capitalists operating

- 209/210 -

GOS, thus, helping policy-makers to understand how exploitation in the 21st century might be widespread. In addition, computer scientists engaged in AI and machine learning capabilities informed policy-makers of how neural networks function, identified their raw material and highlighted the crucial role that their objective has in the logic of GOS corporations.[23] Building on the immense work of these scientists and engaging in a multidisciplinary discourse to create synergies, legal and political theorists might propose reform initiatives to preserve the foundational values of liberal democratic societies. To contribute to the embryonic discourse around overcoming the challenge posed by surveillance capitalism is precisely the aim of this research.

Yet, the core of the investigation involves a comparison of authoritative legal texts from the perspectives of constitutional and human rights law. This legal endeavor is motivated, supported and legitimized by the underlying normative aim of preserving individual dignity, collective self-ownership and the integrity of the democratic process. These considerations necessitate the inclusion of a particular theory of justice, exposing the basis of the thesis rooted in ethics and natural law. In other words, one might refer to this primarily comparative legal enquiry, as a 'universalist' pursuit of moral principles that should compel societies, as being posited upon the citizenry by means of the law.[24] However, this essay does not attempt to argue for a novel theory of justice, as a truly universal attempt would do. Instead, it limits itself to operate within the boundaries of liberal democratic constitutionalism - the adequacy of which I hereby assume explicitly - and employs the strategy of 'aversive precedents'.[25] Thus, the study aims to establish principles and practices that societies properly committed to liberal democracy should institutionalize amid the challenge of surveillance capitalism. This limitation is legitimate and necessary, as the scope of the essay does not allow for a meaningful discussion of theories of justice, yet without an explicit normative framework, the objectives of the 'ideal' theory would be arbitrary.

In narrowing the focus to the comparative legal exercise there are additional methodological issues to justify. As such, the decisive factors determining the selection of comparators include their shared historical traditions and common liberal democratic constitutional identities and the substantive market power that the USA and the EU, with their roughly 800 million citizens, represent. Similarly, the significant normative power of these entities also motivated their inclusion. Moreover, as the EU has created a substantive data protection framework, notably the GDPR, and that many GOS corporations reside in the USA these jurisdictions in theory could practice

- 210/211 -

substantive control over surveillance capitalists. Furthermore, the choice of these jurisdictions, both being of a federal type, is motivated by the global nature of the phenomena under scrutiny and the appearance of 'new spheres of normativity distinct from the nation state'.[26]

3. Theoretical Framework

To proceed meaningfully, establishing a common denominator of key concepts appearing in this research is necessary. First, I attempt to introduce a distinction in terms of the data that lie in the core of this dissertation. The line of demarcation in this case should follow the intention of users and demarcate data that are intentionally shared by the user of a GOS, from data that are not intentionally shared, but rather left behind as an online fingerprint or trace that any user's online behaviour generates automatically, 'by dint of the online service's operation'.[27] The intentionally shared data is referred to herein as user-generated content (UGC) and the unintentionally shared data as user-generated traces (UGT). This distinction is relevant when determining the validity of claims of privacy, since the intentional sharing of information could undermine one's 'legitimate expectation of privacy'.[28] However, this might imply that the data generated unintentionally, which are compiled as a seemingly unavoidable consequence of the functioning of the services - UGT - should fall under privacy protection. The aim of performing this distinction is to work towards the 'ideal' theory.

The revolutionary changes of communication technologies unfolding during the previous decades, altered the way in which individuals and societies relate to information. This transformation, which I refer to as the information revolution, shifted the human struggle from receiving information, to the struggle of distinguishing between harmful, manipulative and overwhelming versus valuable, trustworthy and necessary qualities of information. The 'information revolution' alleviated the human struggle of receiving information, as this resource is nowadays constantly and abundantly available to the members of the online community. The difficulty is no longer gaining access to the continuous flow of global information, but rather exercising one's capability to process overwhelming quantities of information and to judge their quality against one's particular objectives became the key challenge instead.[29] The constant overload of information highlights the limited human capacity to process

- 211/212 -

information and assess its reliability, value and utility. According to the law of supply and demand scarcity of a raw material drives up its value, explaining why the competition for human attention is so fierce as to involve constant surveillance and exploitation of private human behaviour.

According to Zuboff, Google was the first corporation to realize how to effectively commodify the immense amount of behavioral data compiling in their systems and simultaneously, how to maximize the absorbed human attention by their platform.[30] This revolutionary method consists in 'aggressively hunting' UGC and UGT as behavioral data, standardizing and feeding them into powerful neural networks, tasked with figuring out how best to engage the user to maximize the attention absorbed.[31] The better the behavioral data analysis, the more user engagement. The more engagement, the more place for ads and the more revenue for surveillance capitalists. As shown by psychological studies, often what maximizes engagement is content that provokes either complete surprise, fear and outrage[32] or content that resonates well with the already existing opinion of the user.[33] Thus, the spreading of fake news and the proliferation of echo chambers online might also be linked to the logic of surveillance capitalism. Thus, it seems that people's novel capability to communicate and access information online on unprecedented scales, reciprocally translates into GOS corporations ability to control and steer the information a particular person or community receives. As experiments showcase, by means of their immense agenda setting power, GOS corporations can manipulate the emotions and actions of users which is not only concerning from the perspective of individual mental health, but also from the perspective of voter behavior and the integrity of the democratic process.[34]

Moreover, approaching the challenge of surveillance capitalism from a legal perspective, a crucial theoretical debate concerning the distinction between public and private law must be clarified. After all, in both jurisdictions there are constitutional

- 212/213 -

provisions that ensure individual privacy. Nevertheless, the core of the public-private law debate is whether fundamental and constitutional rights should have a horizontal direct effect in private disputes. Meaning, whether fundamental rights, originally conceived as limiting the exercise of state powers vis-á-vis individuals, should also influence the relationship between private parties and if so, to what an extent. There are generally two sides to this debate: some legal theorists would argue that fundamental rights are exogenous, while others would contend that they are endogenous to private law.[35] Those arguing that fundamental rights are exogenous recall the historical development of such rights, which were conceived to limit intrusions by the state into a citizen's private life. Hence, the application of fundamental rights should be limited to the domain of public law, while private parties should be free to engage in voluntary contractual relationships.

In contrast, legal theorists who argue that fundamental rights are endogenous to private law emphasize the hierarchical normative structure of legal systems. Afterall, constitutions are the basis of jurisdictions, creating the state itself, which posits other laws. They claim that it is in the nature of fundamental rights that their normative value trumps that of other laws. They logically uphold the entire legal system, so their provisions should also constrain parties to voluntary private contracts.[36] The EU has also undertaken to provide horizontal applicability to some of its fundamental rights provided in its Charter of Fundamental Rights (CFR), such as the right to non-discrimination (Article 21) in the Kücükdeveci decision.[37] Moreover, through directly applicable regulations such as the GDPR, the EU has provided for their direct application in private disputes. This theoretical debate will be a crucial perspective during the comparative exercise of Section IV.

III. The Normative Basis for Privacy Regulation

In section III, I discuss two normative arguments following from sharply different philosophical traditions, namely liberalism and Marxism, but converging on their conclusions as to the present case. Moreover, as most online services are products of private corporations, this section also attempts to establish the legitimacy of governmental intervention into the horizontal relationship between GOS corporations and their users.

- 213/214 -

1. Two arguments for data protection

Under the school of liberal egalitarianism, it is generally assumed that a person is free, equal to other persons and is capable of being the author of her own life, to behave autonomously.[38] As Rawls put it, 'citizens recognize one another as having the moral power to have a conception of the good (...) capable of revising and changing this conception on reasonable and rational grounds'.[39] Based on these assumptions concerning the nature of a person, in liberal democratic regimes confer a huge responsibility on citizens, the collective leadership of the constituency through elected representatives. Now, the question remains: how is the political opinion of the individual formed? In that regard, the crucial role of the media becomes apparent, as it is the institution that is supposed to supply the citizen with information about the state of the world, complementing her own sensory experience. Based upon such information about a particular state of the world X, a citizen develops a moral judgement concerning the adequacy of X. This judgement subsequently becomes a constituent part of her own conception of the good. Therefore, if one accepts that politics might be defined as the arena where competing conceptions of the good supply alternative solutions to collective action problems, one sees that there is a straightforward relationship between the informational input of citizens - largely supplied by the media - and their political alignment, action or inaction. Hence, it is clear that the institution of the media - often referred to as the 4th branch of power - exerts a significant influence on citizens' political stance. Now, is the third liberal assumption regarding the nature of a person still valid in the era of surveillance capitalism?

While citizens' vulnerability towards the media has remained largely unchanged during the modern history of mankind, when technological changes increased the manipulative capabilities of the media, the development of novel regulatory frameworks was necessary to secure the continued integrity of liberal democratic regimes. With the development of the community of continuous flow of information online and the employment of the logic of surveillance capitalism, the service providers of such a community - GOS corporations - possess an unprecedented capability to manipulate and nudge citizens' conception of the good.[40] Today it is overwhelmingly human-made online service algorithms that determine who receives what information and when.

- 214/215 -

More accurately, the content a user is served with online is determined by artificial neural networks working toward the human created objective of maximizing user engagement. With the constant surveillance of people on private GOS platforms, citizen's very reactions are fed back into algorithms tasked with exploiting psychological vulnerabilities to maximize user engagement, including by exposing the citizen to false, misleading or superfluous information. Therefore, those who create and control these algorithms substantiate an enormous amount of control and consequent responsibility over the users of GOS. Therefore, I maintain that the third liberal assumption is at best under a serious threat by the largely unregulated business model of GOS corporations. From a liberal perspective the unrestricted operation of GOS corporations, under their right to property, freedom of business and contractual freedom, threatens the personal and collective decision-making process. Thus, perhaps it should be regulated to preserve the state's core liberal characteristics in the form of personal self-ownership and the integrity of the democratic process.

On the other side, one finds argumentative grounds for the regulation of GOS corporations in Marxist moral philosophy. The centrepiece of that school is the exploitation of the less powerful, by the more powerful. Exploitation is often defined as taking unfair advantage of someone, or 'using another person's vulnerability for one's own benefit'.[41] Here the emphasis is on "unfair", since few would condemn a person for taking advantage of the inattention of the opponent in an otherwise structurally fair setting such as a football game.[42] What makes taking advantage unfair is the element of coercion or necessity to submit oneself to a particular treatment. In the famous account of Marx, without ownership of the means of production, the workers' need to sustain themselves effectively forces them to sell their labor. If the wage they receive for labour is insufficient to secure a meaningful life, their vulnerability is being exploited by the more powerful.[43]

The application of the Marxist account of exploitation to the subject of the present enquiry is elegantly performed by Celis Bueno in his book 'The Attention Economy'. His point of departure is that as societies grow richer in terms of the production and consumption of information, comparatively they become poorer in terms of human attention.[44] With the overabundance of information online, human attention becomes an 'intrinsically scarce and therefore valuable resource'.[45] Provided that advertising companies derive profit from capturing human attention, there is a fierce competition to maximise user engagement including by employing constant

- 215/216 -

surveillance. Similarly, Zuboff[46] claims that GOS corporations regard human experience - data derived about the allocation of attention - as 'free raw material for hidden commercial practices of extraction, prediction and sales'.[47] 'At first such data was found', but as the pioneers of surveillance capitalism became conscious of the possibilities behind the resource, it was 'hunted aggressively' by means of mass surveillance.[48] Effectively, the act of paying attention became a new form of labor creating surplus value.[49] This simultaneously 'blurs the line between labor time and leisure time', while alienating the spectator from her own vision.[50]

The only premise missing from legitimately claiming that the structure of the attention economy amounts to exploitation of the user of a GOS corporation is the element of necessity or coercion. In that regard, I claim that humans of the 21st century are effectively obliged to be members of the online community. While I expand this argument in the next section, suffice to say that not only is membership essential for participation in the job-market, it also became a prerequisite of receiving an education and essential for maintaining social relationships. Thus, it is not far-fetched to claim that under the status quo, GOS corporations are effectively exploiting their users by performing a constant surveillance of their actions to exploit their psychological vulnerabilities, creating addiction to their sites and reaping profits from the maximized user engagement.

All in all, it is rather alarming that the application of such diverse moral traditions as liberalism and Marxism jointly imply that the status quo necessitates reforms to protect and respect people's autonomy. Uniting the forces of these arguments, I intend to claim that undermining personal and collective autonomy by manipulation and exploitation amounts to using people as a mere means as opposed to ends in themselves. This conduct goes against the second formulation of the Kantian Categorical Imperative (CI) prescribing that one must treat humanity 'always at the same time as an end, never merely as a means'.[51] Now, the violation of this deontological principle is crucial in this primarily legal enquiry, for this formulation of the CI has been highly influential in constructing a meaning for the term 'dignity', often referred to as a supreme, legitimating value of human rights protection.[52] This is the case under

- 216/217 -

the EUCFR and the jurisprudence of the ECtHR.[53] Thus, it seems that if the argument for the violation of dignity remains intact, it might have severe consequences for the legality of the behavior of GOS corporations.

2. The (il)legitimacy of state intervention

While the above arguments exposed the troublesome nature of GOS corporations, it is yet to be determined whether a public intervention into the investigated private relationship would be legitimate. Given that the present research operates within the boundaries of liberal democracy, the legitimacy of state intervention must also be established within that paradigm. This might result to be a challenging task, since state neutrality is often praised as a foundational liberal principle.[54] This principle shall be understood as requiring the state to refrain from prioritizing any particular conception of the good over others and to respect and secure the autonomy of citizens. Afterall, from the perspective of liberal neutrality, 'no life goes better by being led from the outside according to values the person does not endorse'.[55]

Nevertheless, there is another strand of liberal thought that positions itself closer to communitarianism and objects to the atomistic perspective employed by scholars endorsing state neutrality.[56] This latter position is defended and elaborated for example by Charles Taylor, for example, in his 'social thesis' arguing that individual autonomy might only be exercised in a particular community with an enabling environment, sustained by a non-neutral government of the common good.[57] 'Some limits on individual self-determination are required to preserve the social conditions which enable self-determination'.[58] The degree of autonomy available for a particular individual is largely determined by the surrounding social environment. In order for the community as a whole to be free and for its members to enjoy the beauty of self-ownership, the state shall be under a positive obligation to actively protect the community's dominant way of life. The state's duty is to maximize the aggregate level of autonomy enjoyed by the members of the community and often this requires some

- 217/218 -

agents' autonomy to be limited. Indeed, even Rawls concedes in the formulation of his 'First Priority Rule' that liberty might be limited, however, only for the sake of liberty.[59] This position is not alien to legal thinking, more so, the often and rightly praised proportionality analysis between competing fundamental rights is a prime example of the social thesis in practice. The state attempting to maximize overall enjoyment of liberty, often limits some citizens' ability to do so on the basis of a rule of law.

Turning from abstract principles to the concrete controversy at hand, there is certainly a natural reaction to the attempt of intervening into the horizontal relationship between GOS corporations and users. If the use of GOS poses such a threat to individual dignity, people should just stop using them. After all, it is their decision to be online or not and governmental regulation should not restrict the private contractual relationship between GOS corporations and their users. While there is certainly some legitimacy to this remark, there is a tripartite counterargument that I defend below.

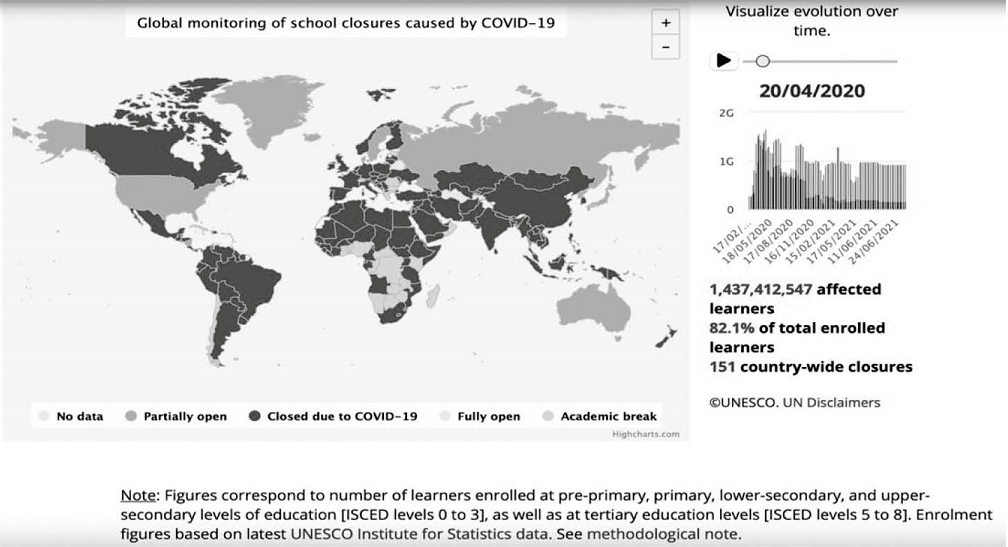

Firstly, I maintain that leaving citizens with a choice between giving up their capability for self-ownership or abandoning the tremendous benefits that GOS provide them would impose an undue burden on individuals. Composing this research in 2021 perfectly showcases citizens' high level of dependency upon online services and thus, the undue burden that avoiding them would impose on citizens. From library access to a 10 year old's math class, from communication with the state to participation in remote work opportunities, from social engagement to political participation, humans of the '20s are to rely upon online services to participate meaningfully in society. Specifically, as education migrated to online services due to Covid-19, students who faced difficulties in accessing online communication experienced a decrease in their capabilities to participate in education, which increased the already existing achievement gaps due to social backgrounds.[60] If one accepts the premise that access to education is constitutive of human flourishing, then one should also accept the conclusion that - at least with Covid-19 - membership of the online community became a prerequisite for achieving social flourishing.[61] Provided that both self-ownership and access to GOS are integral to human flourishing, the supposedly free decision, actually imposes an undue burden on individuals. This choice should not be forced upon citizens. Therefore, governmental regulation of data protection remains legitimate.

- 218/219 -

Figure 1. Number of children forced to participate in online education. Source: Unesco, Global Monitoring of School Closures, https://en.unesco.org/covid19/educationresponse (Last accessed: 29.12.2023.)

Another argument for the legitimacy of intervention rests on the social relevance of individual privacy in liberal democratic regimes. This has been duly considered above in Section III.1 as part of the liberal critique of the status quo. The business model of GOS threatens the foundational values of liberal democratic regimes - autonomy, dignity and the integrity of the democratic process. Therefore, recalling Taylor's social thesis, it is not only legitimate, but should be a duty of a state properly committed to the above values to develop a regulatory framework that effectively protects its citizens and itself from the threat of surveillance capitalism. The preservation of the liberal democratic constitutional identity legitimizes intervention.

The third line of defense of state intervention targets the validity of the contractual relationship between corporations and individuals. In developing this account, the normative foundations of consumer and competition law become relevant, particularly the notions of exploiting a dominant position and operating under an information and power asymmetry.[62] The freedom of economic competition is at the heart of a liberal market economy. Economic actors should be free to practice their autonomy within the provided limits of the law, however, the aim that those limits ought to promote remains contested. Some argue that the overall welfare created by a

- 219/220 -

regulatory framework - the sum of consumer and producer surplus - should be maximized by regulation.[63] Nevertheless, others maintain, notably Adam Smith, that market regulation should make 'consumer preferences the ultimate controlling force in the process of production', a principle also known as consumer sovereignty.[64] While the producers that might benefit by 'escaping the burden of competition' will inevitably only represent a segment of producers and will conflict with others, a market regulation that favours consumer sovereignty will benefit all consumers indiscriminately, thus assuring a general compensation for any particular cost they have as a producer.[65] A similar conclusion is implied by assessing the specific objectives behind EU competition law. In that regard, referring to Articles 101 and 102 TFEU, Botta and Wiedemann asserts that by sanctioning the anticompetitive behavior of undertakings, EU competition law indirectly 'safeguards the aggregate welfare of consumers'.[66] Furthermore, crucially for the present essay, they also assert that the application of these provisions is horizontal: they apply directly to private undertakings.[67] All in all, this limited account of the normative basis of consumer and competition law implies that consumer interest should be prioritized by maintaining healthy competition in the market.

Finally, one additional line of argument could be developed concerning the public importance of the functions that certain GOS corporations perform.[68] For example, operating the most wide-reaching contemporary political agora and the consequent sensitive regulatory functions associated with freedom of speech or the reliability of news. While there is no space here to duly expand this counterargument, I believe the case is made that for the protection of the liberal democratic constitutional identity and its foundational values, governmental intervention into the investigated relationships is legitimate. This position implies that the constitutional protection of privacy should have a horizontal effect on the private contractual agreements between GOS providers and their users.

- 220/221 -

IV. Cross-Atlantic Comparison: Does Regulation Keep the Pace of Technology?

In this section, I investigate in a comparative fashion the legal protection of data privacy in the jurisdictions of the USA and the EU. For sake of space, I omit the otherwise significant discussion of the structural differences between the jurisdictions and I perform a textual and contextual analysis of the main authoritative texts.

1. The Basis of Privacy Protection - A Textual and Contextual Analysis

First, I turn towards the US Constitution. Its particular structure with seven main Articles and the following Amendments is a result of the tense political debates between the federalist and the anti-federalists.[69] Known as the Massachusetts Compromise, a sufficient number of states of the Confederation agreed to ratify the new Constitution provided that certain amendments would be proposed rather soon in order to prevent the freshly established executive power from usurping too much power and threatening individual rights.[70] Thus, in the context of protecting the rights of individuals against encroachments of the federal government, 10 Amendments were codified into the Constitution. One of such is the 4th Amendment:

Figure 2. The Fourth Amendment to the US Constitution, own illustration[71]

Without any doubt this Amendment primarily aims to protect US citizens' privacy and security from arbitrary interferences by the government.[72] The Fourth Amendment

- 221/222 -

does not confer an absolute right upon citizens, but similarly to its European counterparts,[73] only a limited one. The phrase 'The right of the people to be secure (...) against unreasonable searches and seizures' implies a balancing exercise between the competing interest of the government and the individual as an inherent part of determining which interferences meet the reasonability criteria. The reasonable expectation of privacy test was fleshed out in Katz v. United States.[74] First it must be evaluated whether the individual concerned had a subjective expectation of privacy and second, whether society would be prepared to recognize that subjective expectation as a reasonable one.[75] Interestingly, this test has migrated to the other side of the Atlantic as well, where the ECtHR has integrated it into its own jurisprudence, and there are references to it even in the GDPR.[76]

Similarly, the fundamental rights provided in the ECHR primarily entail negative obligations on states. Nevertheless, to undertake positive obligations by contracting parties was a clear intention among the framers of the Convention. Positive state obligations originate from the state's duty to protect citizens under its jurisdiction (Article 1 ECHR).[77] For the state to violate its positive duties, the conduct of private parties allegedly contrary to the Convention must arise from the contracting party's failure to act or toleration.[78] In line with the principles of conferral and subsidiarity, in controversies involving positive duties, the Court grants a certain margin of appreciation to the states.[79] Nevertheless, under certain circumstances, especially where vulnerable parties are concerned, contracting states are under the positive obligation to develop regulatory frameworks that provide practical and effective[80] protection to citizens from foreseeable infringements of their rights resulting from the actions of private parties.[81] Similarly to the US, the rights entailed in Article 8 ECHR

- 222/223 -

are not absolute, but are limited in various ways. Thus, like in the USA, the interest of the individual in the form of the enjoyment of her right must be balanced against the state interest of providing the enlisted public goods.

The European focus on the universality of fundamental rights[82] constitutes a major textual difference compared to the US Constitution. Nevertheless, in the USA human rights also have their foundations in natural law, implying a universalistic conception of rights and an objective value order.[83] This is exemplified by the famous lines of the Declaration of Independence: 'We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights.' Therefore, while from a textual perspective[84] and from one perspective of the contextual analysis the Constitution implies a clear intention to create only negative obligations for the state, another contextual perspective undoubtedly implies that the theoretical foundation of human rights in the US lies in natural law, implying and objective value order. From this theoretical perspective, it would not be overambitious to maintain that constitutional rights such as the Fourth Amendment should have a radiating effect into private disputes.

Moreover, crucial for the present enquiry is whether and when the 4th Amendment could cover online communications and if so, what kinds of data? Concerning online data flows the case law is divided as it is not straightforward whether a person has a legitimate expectation of privacy when using an online service and thus sharing information with a third-party service provider. Cases concerning access to one's location information through GPS tracking were deemed to raise justified privacy expectations.[85] However, the Supreme Court found no justified expectation of privacy with regards to financial records being accessed through the network of a bank[86] or dialled phone numbers beings accessed by means of installing a pen register device to a telephone line.[87]

Interestingly, if one consents to a warrantless search or does not object to one, it becomes legitimate in the eyes of the law,[88] a logic that lies at the heart of EU privacy protection.[89] What are the safeguards surrounding consent in the US? The Supreme Court decided that the burden of proof rests with the prosecution as for the voluntariness of the consent and the awareness of the right of choice.[90] While these are

- 223/224 -

important safeguards, from the perspective of surveillance capitalism, would sharing data with a service provider with the intention of using a service qualify as consenting to a warrantless search? This brings us to the 'third party doctrine'. This principle was developed in Smith v. Maryland where it has been asserted that information that is voluntarily turned over to a third party can no longer fall under one's legitimate expectation of privacy.[91]

Nevertheless, the case Carpenter v. United States will offer some more appealing conclusions. Here the surveillance of cell site location information (CSLI) by government agents was the subject of the controversy. CSLI is a 'detailed, encyclopedic, and effortlessly compiled' data set, which is generated when a phone routinely connects to a nearby radio antenna.[92] The FBI accessed 13,000 data points illustrating the movement of a robbery suspect without a warrant and tried to use the information as evidence at the trials. Carpenter petitioned the Supreme Court to suppress the data and eventually won. In its reasoning the Court recalled that despite Smith, individuals have a 'reasonable expectation of privacy in the whole of their physical movements', and access to CSLI would enable the government to 'near perfectly retrace a person's whereabouts'.[93] Moreover, an individual does not truly voluntarily expose her CSLI, rather the 'cell phone logs a cell-site record by dint of its operation, without any affirmative act on the user's part beyond powering up'.[94] Finally, having regard to the fact that 'cell phones and the services they provide are such a pervasive and insistent part of daily life that carrying one is indispensable to participation in modern society',[95] the Court refuses to apply the doctrine here. Rather, the Court recognized Carpenter's legitimate expectation of privacy and in similar cases requires a warrant upon probable cause to access the information.[96] With Carpenter, I attempt to illustrate that the Supreme Court in its Fourth Amendment jurisprudence has the tools to protect citizens' privacy in the 21st century's digital reality. However, applying Carpenter's logic in a contractual, horizontal dispute would be at best contentious due to the lacking horizontal applicability of the Fourth Amendment and the third party doctrine's negative implications.

As for EU community law, the fundamental rights relevant to the present analysis are provided for in Article 7 and 8 of the CFR and Article 16 of TFEU. Concerning the context of these provisions, it should be noted that according to Article

- 224/225 -

1 CFR: 'Human dignity is inviolable. It must be respected and protected.' This formulation, similarly to the ECHR,[97] endorses an objective value order and a universal theory of fundamental rights, a key textual difference compared to the US Constitution. Another difference between the three textual bases is that the protection of personal data is explicitly covered under EU law. However, this need not result in a substantively wider protection since both Article 8 ECHR and the 4th Amendment apply to online communication data.[98] Another difference from the textual perspective is found in Article 8 §2 CFR: data processing should be based on consent. The element of consent is central in the protection of privacy under EU law. To investigate how this principle is further specified, I turn to the analysis of EU secondary legislation but, for the sake of space, I omit a general evaluation of the GDPR and focus on the element of consent.

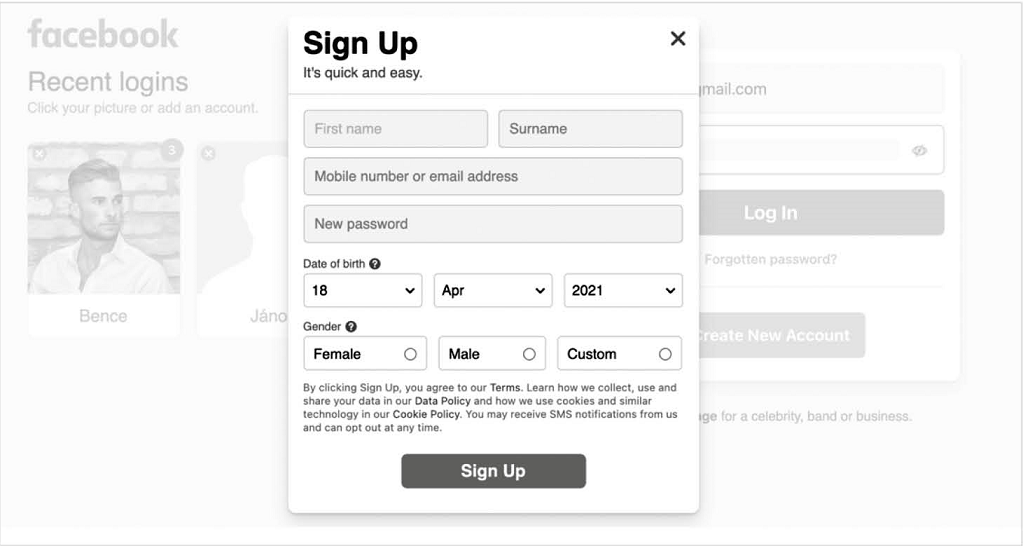

The use of most GOS is conditional upon consenting to controversial contracts or privacy policies.[99] Thus, the conditions for the legitimacy of consent is the most important aspect of this enquiry. Consent should be a freely given, specific, informed and unambiguous indication from the data subject.[100] Controllers shall request consent in a 'clearly distinguishable', 'intelligible and easily accessible form', 'using clear and plain language'.[101] While, the right to withdraw consent is provided for, given GOS conditionality on consent, this right is effectively void. In 7(4) the lawgiver asserts that in assessing whether a consent is freely given it shall be considered whether the requested service is 'conditional on consent to personal data processing that is not necessary for the performance of that contract'. This provision echoes the moral arguments elaborated above, however, it is difficult to interpret the exact meaning of the phrase. After all, one might argue that whatever purpose is included in the contract and hence consented to by the data subject, is thus necessary for the performance of that very contract. Nevertheless, an opposing argument could be developed from the fact that one uses Facebook or Google for specific communicative purposes and additional services such as personalized marketing are not necessary for the primary function of GOS (as reasonably expected by users). As such, making the use of services conditional on such profiling cookies for marketing purposes would render the consent constrained. If the first interpretation is applied, the provision fails to be effective in data protection amid surveillance capitalism, while in the second case it does provide an effective safeguard.[102]

- 225/226 -

Figure 3. Attempting to Register for Facebook in 2021.[103]

Further sophistication is provided by the recitals: 'Consent should not be regarded as freely given if the data subject has no genuine or free choice or is unable to refuse or withdraw consent without detriment'.[104] Additionally, if there is a 'clear imbalance between the data subject and the controller', the consent should not provide a lawful basis for processing.[105] Similarly, if 'the provision of a service, is dependent on the consent despite such consent not being necessary for such performance', then the consent is presumed not to be freely given.[106] While one should treat these recitals with due limitations, they clearly support the second interpretation of Article 7(4).

Finally, to consider a counterargument, some might argue that automated profiling for marketing is necessary for the provision of the contract as it generates the capital inflow that provides for the primary function without monetary fees. Nevertheless, 'necessity' implies that something cannot be otherwise. At least one possibility comes to mind, namely a subscription-based system. Thus, I maintain that the second interpretation of Article 7(4) GDPR should be applied in judging the

- 226/227 -

legitimacy of consents and therefore, I argue that the qualification of consent under the GDPR could provide a meaningful privacy protection amid surveillance capitalism.

The utmost importance of the requirements for free consent is also underlined by Article 9 GDPR, which prohibits the processing of 'special categories of data' revealing 'ethnic origin, political opinions, religious or philosophical beliefs, trade union membership' or sexual orientation. The reason why this provision underlines the previous discussion is that the prohibition of the exploitation of such special data is inapplicable, if the data subject consented to such practices.[107] This reveals that lawmakers are entirely aware of the threats posed by the exploitation of sensitive data, however, they trust the decision-making capabilities of data subjects and avoid paternalistic prohibition. From the liberal philosophical standpoint this is not a manifestly mistaken agenda. However, recalling GOS providers extensive manipulative capabilities, the utmost importance of their services and their conditionality upon consent, the legitimacy of relying on user consent even regarding such sensitive data is severely undermined as there is no substantive choice.

2. Evaluation of the jurisdictions

I conclude this comparative enquiry by assessing the different jurisdictions' ability to protect individuals' privacy amid surveillance capitalism. Two crucial questions should be answered: 1) Does privacy protection have a horizontal effect or is there a positive duty for the government to protect citizens' privacy in private contractual relationships? and 2) Does the material scope of privacy protection cover the kinds of data exploited by private corporations?

As for horizontality, in the USA the theoretical foundation of fundamental rights in natural law is perhaps the only grounds upon which a radiating effect could be argued for. Nevertheless, as far as I can judge, the intention of the framers of the Amendments and the textual basis arguments pointing to the opposite direction outweigh the natural law argument. The 'state action doctrine' established that individual rights provisions, except the Thirteenth Amendment, 'bind only governmental actors and not private individuals'.[108] The doctrine is derived from the language of the 14th Amendment. Nevertheless, Gardbaum argues that the state action doctrine does not rule out indirect influences of the Constitution to horizontal

- 227/228 -

disputes, exemplified by the cases NYTimes v. Sullivan[109] and Shalley v. Kramer.[110] Gardbaum claims that all US law is 'directly and fully subject to the Constitution' and individual rights provisions have a substantive indirect effect on the lawful behavior of individuals.[111] While this argument does allow for a more positive view of US as for the first question, all in all it seems that the 4th Amendment could not be used as grounds for successful litigation in a horizontal dispute against a GOS provider.

As for the protective scope, the third party doctrine 'allows for very far reaching access to private data that is much more restricted in other legal systems'.[112] The US Supreme Court seemed reluctant to extend the otherwise progressive logic of Carpenter[113] to cover the relationship between GOS providers and their users, although de facto there are various similarities between CSLI data and UGT data. They are both generated automatically, without an affirmative act of the user and as far as my argument goes, access to Facebook or Google is similarly to a mobile phone 'indispensable for participation in modern society'.[114] Thus, I conclude that the third party doctrine would probably in most cases render user's expectation of privacy unreasonable, while the 4th Amendment would not be applicable to a dispute between a data subject and a private GOS corporation. Thus, the current US system fails to provide effective protection amid surveillance capitalism.

Concerning the EU, it seems that despite the ECHR's explicit requirement of positive obligations, the margin of appreciation and the emphasis on the principles of conferral and subsidiarity would preclude a meaningful, short-term protection of privacy amid surveillance capitalism. While the standards of the court resemble that of EU community law, leaving the construction of the precise legislative frameworks to domestic legislatures would not provide a short term solution to the pressing issue of surveillance capitalism.

Nevertheless, my limited analysis found that EU citizens could rely on the GDPR for a meaningful protection against GOS providers and thus, the GDPR could function as an effective gatekeeper of democracy and protector of individual dignity. The reasons for this position include the qualification of free consent provided for in Article 7(4). According to its appropiate interpretation, GOS providers' requirement of consent to unnecessary data processing, from the perspective of the primary purpose of the service, provides grounds for regarding that consent constrained. Hence, such consents should fail to be legal bases for data processing. Additionally, there seems to

- 228/229 -

be clear information and power asymmetries between the actors which further reinforce the constrained nature of consents.[115] Concerning the EU framework I conclude that if (a) the CJEU pays due attention to the crucial importance of GOS for realizing one's potential for social flourishing, if (b) the CJEU recognizes that consent for processing of value added services is often required for the use of GOS, (c) that both refusing to use the services and consenting to the exploitation of one's most sensitive data impose an undue burden on individuals and (d) that GOS corporations exploit their dominant position resulting from the previous premises, then, the Court should not accept forced consents to privacy policies such as the one exemplified by Figure 3. above and the GDPR could provide substantive protection for citizens amid surveillance capitalism.

V. Conclusion: Towards an 'ideal' regulatory framework of privacy protection

To conclude the project I reflect on the 'ideal' data protection framework for an international community properly committed to the protection of individual dignity and the integrity of the democratic process, while aiming to provide a reasonable capital inflow for innovative GOS providers. Based on the normative arguments and the comparative legal enquiry, I argue that the GDPR framework with the focus on qualified user consent should be institutionalized as an effective international practice in relation to the investigated jurisdictions. However, as detailed below, I maintain that the GDPR should be further reformed following the logic of the reasonable expectation of privacy principle, to secure reasonable revenue streams for GOS corporations and to facilitate its acceptance in the USA.

Crucially, the adequate interpretation of the qualifications of consent under the GDPR supplied by the thresholds of Article7(4), the 'genuine choice without detriment'[116] and the 'clear imbalance between actors',[117] should function as effective protections of citizen's privacy. Effectively, an adequately implemented qualified consent approach leaves citizens with the freedom to decide for themselves what data are they willing to share for exploitation, while it secures GOS corporations capability to reap profits from providing personalized marketing for users who truly freely consent to it. Moreover, this approach marries data protection law to competition and consumer protection law, as it applies the logic of Article 102 TFEU under the rules of competition, prohibiting the abuse of a dominant position by imposing unfair trading

- 229/230 -

conditions.[118] the USA also has a long history of antitrust laws[119] and a powerful Federal Trade Commission protecting both competition and consumers.[120] Therefore, achieving data and privacy protection through sanctioning unfair and deceptive trading practices, like the one illustrated in Figure 3., by jointly enforcing data protection, competition and consumer protection laws should be the strategy adopted in internationally.

However, an objection to the qualified consent GDPR framework might arise from the perspective of the third aim of the 'ideal' approach - GOS revenues. It is conceivable that merely a fraction of users would agree to the exploitation of behavioural data for personalized marketing purposes, provided a substantive choice. Thus, GOS corporations would lose substantial revenues and this could result to be an excessive intrusion into the market. Hence finally, I argue that in line with the reasonable expectation of privacy test and the distinction introduced between UGC and UGT, GOS corporations should be allowed to use UGC data for profiling and other value added purposes, based on a consent contingent on the use of the service. Afterall, data subjects share such information intentionally, making it publicly available and they have an effective control over what they share as UGC. However, GOS providers should not be able to exploit one's online traces, only contingent on user consent that one can decline without detriment and that meets the strengthened consent qualifications of the GDPR interpreted through the lenses of competition and consumer protection law. Crucially, this does not contradict previous arguments concerning the legitimate conditions of necessity for the provision of the service, since GOS corporations' claim for revenues from innovative marketing practices is legitimate, to the extent that their business model does not manipulate and exploit people, or threatens the integrity of the democratic process. By allowing the use of intentionally shared UGC such as posts and comments, and substantively restricting the use of unintentionally produced UGT such as CLSI, the capabilities of GOS corporations that threaten the fundamental values of constitutional democracies would be sufficiently tempered.

This framework is I think the one that maximizes overall expected utility for our societies. GOS manipulative capabilities would be substantively lower as a considerably lower number of users would allow the exploitation of UGT data. Citizens would continue having unprecedented communication capabilities without monetary fees and they could effectively decide what information they allow for exploitation,

- 230/231 -

coinciding with the information they intentionally share online. Meanwhile, GOS providers would still secure stable revenues. Moreover, if the GDPR incorporates the reasonable expectation of privacy logic with the UGC-UGT distinction, the US could more easily internalize this framework as a federal privacy bill. With this conclusion I hope the paper could somewhat contribute to an ideal data protection framework for the international liberal democratic community. ■

NOTES

* Disclaimer: This essay is a slightly modified version of my master's thesis awarded with the highest mark as part of the Comparative Constitutional Law (LLM) program at the Central European University.

[1] S. Zuboff, The Age of Surveillance Capitalism, (Public Affairs Books, New York, 2019, ISBN 139781610395694).

[2] M. C., D'Arienzo, V., Boursier and M. D., Griffiths, Addiction to Social Media and Attachment Styles: A Systematic Literature Review, (2019) (17) Int J Ment Health Addiction, 1094-1118, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-019-00082-5

[3] C. Sagioglou and T. Greitemeyer, Facebook's emotional consequences: Why Facebook causes a decrease in mood and why people still use it, (2014) (35) Computers in Human Behavior, 359-363, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.03.003

[4] C. C. Bueno, The Attention Economy: Labour, Time and Power in Cognitive Capitalism, (Rowman & Littlefield International, 2016, ISBN-13 978-1783488230).

[5] Zuboff, The Age of Surveillance Capitalism, 94.

[6] Ibid. 9.

[7] Bueno, The Attention Economy: Labour, Time and Power in Cognitive Capitalism, and Predicting by Machine learning: Good Questions, Real Answers: How Does Facebook Use Machine Learning to Deliver Ads?, Facebook Business, (11.06.2020), https://www.facebook.com/business/news/good-questions-real-answers-how-does-facebook-use-machine-learning-to-deliver-ads (Last accessed: 29.12.2023.)

[8] "In 2019, about 98.5 percent of Facebook's global revenue was generated from advertising, whereas only around two percent was generated by payments and other fees revenue." Facebook: advertising revenue worldwide 2009-2019 Published by J. Clement, Feb 28, 2020, https://www.statista.com/statistics/271258/facebooks-advertising-revenue-worldwide/ (Last accessed: 29.12.2023.). "In the most recent fiscal period, advertising revenue through Google Sites made up 70.9 percent of the company's revenues." Google: annual advertising revenue 2001-2019 Published by J. Clement, Feb 5, 2020, https://www.statista.com/statistics/266249/advertising-revenue-of-google/ (Last accessed: 29.12.2023.).

[9] These studies revealed that a person's online context influences her emotions and actions. Thus, the authority or algorithm that determines the posts in one's feed, can influence the person's emotions and actions. D. I. A. Kramer, J. E. Guillory and J. T. Hancock, Emotional contagion through social networks, (2014) 111 (24), Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 8788-8790, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1320040111 and R. Bond, C. Fariss and J. Jones, et al., A 61-million-person experiment in social influence and political mobilization, (2012) (489) Nature, 295-298, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nature11421

[10] C. McCrudden, Legal Research and the Social Sciences, (2006) (122) Law Quarterly Review, 632-650.

[11] Out of the 10 largest corporations in the world by market capitalization, a minimum of four are GOS corporations using methods of surveillance capitalism, https://www.statista.com/statistics/263264/top-companies-in-the-world-by-market-capitalization/ (Last accessed: 29.12.2023.).

[12] The metaphor was allegedly coined by mathematician Clive Humby, https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2013/aug/23/tech-giants-data (Last accessed: 29.12.2023.).

[13] 'Surveillance dividend' refers to the marginal advertising profits a corporation can reap as a result of exploiting behavioural data. S. Zuboff, You are now remotely controlled, NY Times, (24.01.2020), https://www.nytimes.com/2020/01/24/opinion/sunday/surveillance-capitalism.html (Last accessed: 29.12.2023.).

[14] Kramer, Guillory and Hancock, Emotional contagion through social networks.

[15] A. Sajó and R. Uitz, The Constitution of Freedom, An introduction to legal constitutionalism, (OUP, New York, 2017) 87, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780198732174.001.0001

[16] J. Waldron, Autonomy and Perfectionism in Raz's Morality of Freedom, (1989) (62) S. CAL. L. REV., 1097-1152, https://heinonline.org/HOL/LandingPage?handle=hein.journals/scal62&div= 31&id=&page= (Last accessed: 29.12.2023.).

[17] L. M. Alcoff, Epistemologies of Ignorance, Three Types, in S. Sullivan and N. Tuana (eds), Epistemologies of Ignorance, (State University of New York Press, 2007).

[18] J. Habermas, Citizenship and National Identity: some reflections on the future of Europe' Praxis International, (1992) 12 (1) 1-19, (1992) (7) in W. Kymlicka, Contemporary Political Philosophy an Introduction, (Oxford University Press, 2002) 285.

[19] Zuboff, The Age of Surveillance Capitalism.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Bueno, The Attention Economy: Labour, Time and Power in Cognitive Capitalism.

[22] D'Arienzo, Boursier and Griffiths, Addiction to Social Media and Attachment Styles: A Systematic Literature Review; Sagioglou and Greitemeyer, Facebook's emotional consequences: Why Facebook causes a decrease in mood and why people still use it.

[23] J. Schmidhuber, Deep learning in neural networks: An overview, (2015) 61 Neural Networks, 85-117, DOI: https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1404.7828

[24] V. C. Jackson, Comparative Constitutional Law: Methodologies, in M. Rosenfeld and A. Sajó (eds), The Oxford Handbook of Comparative Constitutional Law, (OUP, 2012, ISBN: 9780199578610), DOI: https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199578610.013.0004

[25] Ibid. 6.

[26] R. Leckey, Review of Comparative Law, (2017) Social & Legal Studies, (3-24) 16, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/09646639166707

[27] 'by dint of its operation' this phrase referring to cell site location information was a significant expression determining the US Supreme Court decision Carpenter v. USA, 585 US (2018).

[28] Katz v. United States, 389 US (1967) and Barbulescu v. Romania, 61496/08.

[29] Ibid.

[30] Zuboff, The Age of Surveillance Capitalism.

[31] Ibid. 94.

[32] S. Vosoughi, D. Roy and S. Aral, The spread of true and false news online, (2018) 359 (6380) Science, DOI: https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.aap9559

[33] "Again, we find support for the hypothesis that platforms implementing news feed algorithms like Facebook may elicit the emergence of echo-chambers." M. Cinelli et al., Echo Chambers on Social Media: A comparative analysis, (Cornell University, 2020), DOI: https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2004.09603. While certain studies do establish this link between GOS algorithms and echo chambers, it is worth mentioning that humans in themselves are more prone to interact with opinions that align with their identity. See: D. M. Kahan, Misconceptions, Misinformation, and the Logic of Identity-Protective Cognition, (2017) (164) Cultural Cognition Project Working Paper Series, Yale Law School, Public Law Research Paper, No. 605, Yale Law & Economics Research Paper, No. 575., DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2973067

[34] Kramer, Guillory and Hancock, Emotional contagion through social networks; Bond et al., A 61-million-person experiment in social influence and political mobilization.

[35] M. de Mol, The novel approach of the CJEU on the horizontal direct effect of the EU principle of non-discrimination: (unbridled) expansionism of EU law?, (2011) 18 (1-2) Maastricht Journal of European and Comparative Law, 109-135, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/1023263X1101800106

[36] Ibid.

[37] E. Frantziou, The Horizontal Effect of the Charter: Towards an Understanding of Horizontality as a Structural Constitutional Principle, (2020) 22 Cambridge Yearbook of European Legal Studies, 208-232, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/cel.2020.7

[38] See Waldron, Autonomy and Perfectionism in Raz's Morality of Freedom, furthermore, the classical works of I. Kant, Grounding for the Metaphysics of Morals, in I. Kant, Ethical Philosophy, James W. Ellington (trans.), (Hackett Publishing Co., Indianapolis, IA, 1785 [1983]) and J. S. Mill, On Liberty, David Spitz (ed.), (New York, Norton, 1859, [1975]).

[39] J. Rawls, Kantian Constructivism in Moral Theory: The Dewey Lectures 1980, (1980) 77 Journal of Philosophy, 515-572, in W. Kymlicka, Contemporary Political Philosophy an Introduction, (Oxford University Press, 2002, ISBN 100198782748) 215. DOI: https://doi.org/10.2307/2025790

[40] Kramer, Guillory and Hancock, Emotional contagion through social networks; Bond et al., A 61-million-person experiment in social influence and political mobilization.

[41] M. Zwolinski and A. Wertheimer, Exploitation, in E. N. Zalta (ed.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2017 Edition), https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2017/entries/exploitation/ (Last accessed: 29.12.2023.).

[42] Ibid.

[43] Ibid.

[44] Bueno, The Attention Economy: Labour, Time and Power in Cognitive Capitalism, 1.

[45] Ibid. 3.

[46] Zuboff, The Age of Surveillance Capitalism.

[47] Ibid. 1.

[48] Ibid. 94.

[49] Bueno, The Attention Economy: Labour, Time and Power in Cognitive Capitalism.

[50] Ibid. 6.

[51] Kant, Grounding for the Metaphysics of Morals, 429.

[52] M. Mahlmann, Human Dignity and Autonomy in Modern Constitutional Orders, in M. Rosenfeld and A. Sajó (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Comparative Constitutional Law, (OUP, Oxford, 2012) 371-393, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199578610.013.0020. Mahlmann recalls that dignity appears in the Preamble and Art 1. to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the Preamble to the ECHR among many other examples.

[53] German BL Article 1., EUCFR Article 1. and Christine Goodwin v. The United Kingdom, no. 28957/95, in § 90 the Court provides that: 'the very essence of the Convention is respect for human dignity and human freedom'.

[54] W. Kymlicka, Contemporary Political Philosophy an Introduction, (Oxford University Press, 2002) 217, referring to endorsements of liberal neutrality by Rawls, Ackerman and Dworkin. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1093/hepl/9780198782742.003.0003

[55] Ibid. 216.

[56] Ibid.

[57] Ibid. 245.

[58] Ibid.

[59] Ibid. 56.

[60] E. Dorn et al., New evidence shows that the shutdowns caused by COVID-19 could exacerbate existing achievement gaps, McKinsey, (01.06.2020), https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/public-and-social-sector/our-insights/covid-19-and-student-learning-in-the-united-states-the-hurt-could-last-a-lifetime# (Last accessed: 29.12.2023.).

[61] US Supreme Court case Carpenter v. USA, 585 US (2018). The Court asserted that "carrying one (a mobile device) is indispensable to participation in modern society." Although strictly speaking mobile devices and GOS differ, if carrying a mobile device "is indispensable to participation in modern society", one should ask: whether this logic - especially with the disruption of C-19 - should or could be extended to cover GOS?

[62] R. Nazzini, The Objective of Article 102, in R. Nazzini, The Foundations of European Union Competition Law: The Objective and Principles of Article 102, (Oxford Studies in European Law, OUP, Oxford, 2011, ISBN 0191630128, 9780191630125) 109-110, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1093/law-ocl/9780199226153.001.0001

[63] V. Vanberg, Consumer welfare, total welfare and economic freedom: on the normative foundations of competition policy. Competition Policy and the Economic Approach: Foundations and Limitations, (2011) 09 (3) Freiburg Discussion Papers on Constitutional Economics, 15, http://hdl.handle.net/10419/36471 (Last accessed: 29.12.2023.) DOI: https://doi.org/10.4337/9780857930330.00008

[64] Ibid. 15.

[65] Ibid. 16-17.

[66] M. Botta and K. Wiedemann, The Interaction of EU Competition, Consumer, and Data Protection Law in the Digital Economy: The Regulatory Dilemma in the Facebook Odyssey, (2019) 64 (3) The Antitrust Bulletin, (428-446) 434, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/0003603X19863590

[67] Ibid.

[68] See for example: O. Pollicino, Digital Private Powers Exercising Public Functions: The Constitutional Paradox in the Digital Age and its Possible Solutions, (ECHR, 2021), https://echr.coe.int/Documents/Intervention_20210415_Pollicino_Rule_of_Law_ENG.pdf (Last accessed: 29.12.2023.).

[69] M. Tushnet, The Constitution of the United States of America, A Contextual Analysis, 1. An Overview of the History of the US Constitution, (Hart Publishing, 2015, ISBN 9781841137384) 10-14.

[70] Ibid.

[71] Own illustration.

[72] Camara v. Municipal Court of City and County of San Francisco, 387 U.S. 523, 528, 87 S.Ct. 1727, 18 L.Ed.2d 930 (1967).

[73] See: Article 8 §2 ECHR and the case Privacy International v. Secretary of state, C-623/17. In this case the CJEU ruled that despite national security being the reason for surveillance, the general and indiscriminate retention of data is disproportional.

[74] Katz v. United States, 389 U.S. 347.

[75] Smith v. Maryland, 442 U.S. 735.

[76] See M. de Mol, The novel approach of the CJEU on the horizontal direct effect of the EU principle of non-discrimination: (unbridled) expansionism of EU law?, (2011) 18 (1-2) Maastricht Journal of European and Comparative Law, 109-135, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/1023263X1101800106 for ECHR and Recital §47 referring to GDPR Article 6(1).

[77] J.-F. Akandji-Kombe, Positive obligations under the European Convention on Human Rights. A guide to the implementation of the European Convention on Human Rights, (CoE, Human rights handbooks, No. 7., 2007) 14, https://rm.coe.int/168007ff4d (Last accessed: 29.12.2023.) and Barbulescu v. Romania, App no. 61496/08 (ECtHR, 5 September 2017).

[78] Akandji-Kombe, Positive obligations under the European Convention on Human Rights and Barbulescu.

[79] Akandji-Kombe, Positive obligations under the European Convention on Human Rights.

[80] The practical and effective doctrine is present e. g. in X and Y v. Netherlands, no. 8978/80, 26 March 1985 and Airey v. Ireland, No. 6289/73, 11 September 1979.

[81] Barbulescu, §115 and X and Y, §§ 23, 24 and 27.

[82] See CFR Article 1, and Article 1 ECHR all implying an objective value order.

[83] C. S. Desmond, Natural Law and the American Constitution, (1953) 22 (3) Article 1 Fordham Law Review, https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr/vol22/iss3/1 (Last accessed: 29.12.2023.).

[84] See the Fourteenth Amendment's 'state action doctrine'.

[85] United States v. Jones, 565 U.S. 400.

[86] United States v. Miller, 425 U.S. 435.

[87] Smith v. Maryland, 442 U.S. 735.

[88] Amos v. United States, 255 U.S. 313 (1921).

[89] In the EU under the GDPR, not objecting to surveillance, such as cookies does not constitute legal grounds for the search. The consent has to be an affirmative act from the user.

[90] Bumper v. North Carolina, 391 U.S. 543 (1968) and Johnson v. United States, 333 U.S. 10, 13 (1948).

[91] Smith v. Maryland, 442 U.S. 735.

[92] Carpenter v. U.S., 138 S.Ct. 2206 (2018).

[93] Carpenter (1).

[94] Carpenter (2).

[95] Carpenter (2).

[96] The Court referred to its conclusion as a "narrow" one: "does not disturb the application of Smith and Miller or call into question conventional surveillance techniques and tools, such as security cameras; does not address other business records that might incidentally reveal location information; and does not consider other collection techniques involving foreign affairs or national security." Carpenter, 9.

[97] The preamble to the ECHR provides: "this Declaration aims at securing the universal and effective recognition and observance of the Rights therein declared".

[98] See Barbulescu v. Romania, 61496/08) and Carpenter v. U.S., 138 S.Ct. 2206 (2018).

[99] See Figure 3. below concerning Facebook. The same is applicable when attempting to create a Google account.

[100] GDPR Article 4(11).

[101] GDPR Article 7(2).

[102] The WSJ claims that the EDPB decided that Meta cannot force users to agree to personalized ads by way of making their service conditional on such consent as part of the Terms and Conditions. See S. Schechner, Meta's Targeted Ad Model Faces Restrictions in Europe, WSJ, (06.12.2022), https://www.wsj.com/articles/metas-targeted-ad-model-faces-restrictions-in-europe-11670335772?mod=hp_lead_pos1 (Last accessed: 29.12.2023.).

[103] "Sign up It's quick and easy" while the contract you must agree to is well-hidden. A typical example of the many levels of nudging exerted by GOS corporations. One is required to accept the Terms, the Data Policy and the Cookie Policy which together comprise of 10786 words. Based on my estimation, roughly a person would need 89,88 minutes to read these terms.

[104] Recital to the GDPR §42.

[105] Recital to the GDPR §43.

[106] Ibid.

[107] GDPR Article 9(2)a.

[108] S. Gardbaum, The "Horizontal Effect" of Constitutional Rights, (2003) 102 (3) Michigan Law Review, 1, https://repository.law.umich.edu/mlr/vol102/iss3/2 (Last accessed: 29.12.2023.) DOI: https://doi.org/10.2307/3595366

[109] 376 U.S. 254 (1964).

[110] 334 U.S. 1 (1948).

[111] Gardbaum, The "Horizontal Effect" of Constitutional Rights, 390.

[112] M. Mahlmann, Normative Universalism and Constitutional Pluralism, in I. Motoc et al. (eds), Liber amicorum András Sajó: Internationalisation of Constitutional Law, (2017) 19, https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2998526 (Last accessed: 29.12.2023.).

[113] Carpenter (2)d.

[114] Carpenter (2).

[115] See the tests elaborated in recitals §§42-43.

[116] Recital in §42.

[117] Recital in §43.

[118] Botta and Wiedemann, The Interaction of EU Competition, Consumer, and Data Protection Law in the Digital Economy, 429.

[119] See the 1890 Sherman Act.

[120] A Brief Overview of the Federal Trade Commission's Investigative, Law Enforcement, and Rulemaking Authority, FTC, (2009) https://www.ftc.gov/about-ftc/what-we-do/enforcement-authority (Last accessed: 29.12.2023.).

Lábjegyzetek:

[1] The Author is LLM (CEU, Vienna), is a PhD candidate at the Doctoral School of Political Science at Eötvös Loránd University.