Csenge Merkel[1]: Doctrine of Functionality in Trademark Law: An EU and a US Perspective (IAS, 2021/4., 241-261. o.)

Decisions of the Court of Justice of the European Union and the Supreme Court of the United States regarding the principle of functionality

Absztrakt

A műszaki funkcionalitás doktrínája a védjegy jog meghatározó része. Elválasztja a védjegyek jogi védelmét a többi szellemi tulajdontól, és megakadályozza, hogy hasznos terméktulajdonságokon monopóliumot szerezzenek a gyártók. A funkcionalitás elve mind az Egyesült Államokban mind az Európai Unióban ugyanazt a célt szolgálja, ennek ellenére a joggyakorlat különbözőképpen értelmezi és alkalmazza azt. A tanulmány a két jogrendszer hasonlóságait és különbségeit mutatja be az Európai Unió Bírósága és az Amerikai Egyesült Államok Legfelsőbb Bírósága ítéletei tükrében. A két bíróság különböző teszteket használ annak érdekében, hogy egy termékjellemzőről megállapítsák, hogy funkcionális-e. Ennek következtében a gyártók és forgalmazók más eredményekre számíthatnak a két kontinensen.

Kulcsszavak: védjegy, funkcionalitás, Európai Unió Bírósága, Amerikai Egyesült Államok Legfelsőbb Bírósága, összehasonlítás

Abstract

This paper examines how functionality doctrine in the field of trademark law has been elaborated in the United States (US) and in the European Union (EU) focusing on the case law of the Supreme Court of the United States (Supreme Court) and of the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU). Although trademark law has similar goals in the two systems, there are partial differences between them. The two jurisprudences elaborated different tests under which the functionality of a product feature is decided. As it is shown in this paper, the CJEU applies a stricter test, which leads to less possibilities to obtain trademark protection.

Keywords: trademark, functionality, Court of Justice of the European Union, Supreme Court of the United States, comparison

1. Introduction

This paper aims to examine how functionality doctrine in the field of trademark law has been elaborated in the United States (US) and in the European Union (EU) focusing on the case law of the Supreme Court of the United States (Supreme Court) and of the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU).

In our globalized world the economy would not be imaginable without brands, and the economic benefits of trademarks are undeniable. Judge Easterbrook summarized the benefits the following way: "Trademarks help consumers to select goods. By identifying the source of goods, they convey valuable information to consumers at lower costs. Easily identified trademarks reduce costs consumers incur in searching for what they desire, and the lower the costs of search, the more competitive the market. A trademark also may induce the supplier of goods to make higher quality products and to adhere to a consistent level of quality."[1] The plain purpose of a trademark is source-identification, and that is important for consumers to prevent their confusion.[2] Further, source identification is also crucially important for producers, because trademark

- 241/242 -

rights can directly affect their reputation and goodwill.[3] Having a strong brand is one of the most valuable assets of a firm.[4] Since trademarks are source-identifiers, they give (or can give) perpetual intellectual property rights over marks. This opportunity of perpetuity brings us to the problem of functionality. Firms are willing to "trademark" as many features of a product as possible, to prevent competitors from using them. When a feature of a product is functional, trademark rights over it might harm free competition on the market.

The doctrine of functionality basically prevents the latter situation and means that an undertaking cannot obtain perpetual trademark rights on features that also serve as a function of a product or are otherwise useful. If a feature adds somehow a competitive non-reputational advantage to a product, that feature cannot be protected under trademark law. The purpose of functionality doctrine is the prevention of granting monopolies over those useful features that can make products better. Functionality doctrine allows competitors to copy features that they need in order to manufacture better goods.

The doctrine of functionality also expresses the differences between trademark law and other intellectual property rights. While copyright grants rights to creators over their artistic works and patent law protects scientific inventions, trademark law protects brands. Patent law is the part of intellectual property law that gives patent owners exclusive rights granted for an invention, but this protection can only last for a limited period of time. Time limitation is important, because after the years of granted monopoly, policymakers want competition to flourish again on the affected market.[5] For the same reason the legislation does not want trademark owners to have perpetual rights on inventions or other features that competitors need in order to be effective. Therefore signs must lack functionality to be protectable, meanwhile patent protection requires some kind of functionality.[6] To sum up, if something is useful, it generally cannot be trademarked. "Competitors should have free access to copy a product not protected by a patent or copyright, provided that such competitors do not use confusingly similar trademarks with respect to that product."[7] The only "monopoly" that trademark law would like to give to trademark owners is the right to prevent others from using identical or similar marks on their products, misleading consumers regarding the source.[8] The doctrine of functionality in trademark law maintains the

- 242/243 -

balance between intellectual property rights and competition needs, and prevents the evergreening potential of trademarks.[9]

Despite the same goal of functionality in all legal systems, there can be differences to a greater or lesser degree in how legislators and courts understand these interrelated principles and interests. Each jurisdiction will have to choose and elaborate its own interpretation of functionality. For example, if a feature is useful can it be protected if it does not hinder competition? Or if a feature is useful might it never be protected under trademark law? Isn't this approach too formalist and rigid? These are some of the questions that policymakers and courts must deal with while elaborating the doctrine of functionality. The way different jurisdictions see these different questions is going to be the crux of this analysis.

In the first part of this paper, I will present the US and the EU trademark system in a nutshell. The doctrine of functionality cannot be understood without the system it is incorporated in. In the second part I will present the case-law of the two courts regarding functionality. In the third part I will compare the case-law of the two Courts and draw the conclusions.

2. Main differences and similarities between EU and US Trademark system

2.1. EU law

In the EU, trademark law is governed by several EU legal acts:[10]

1) The EUTMR (Regulation (EU) 2017/1001 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 14 June 2017 on the European Union trade mark)

2) The EUTMDR (Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2018/625 of 5 March 2018 supplementing Regulation (EU) 2017/1001 of the European Parliament and of the Council on the European Union trade mark, and repealing Delegated Regulation (EU) 2017/1430)

3) EUTMIR (Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2018/626 of 5 March 2018 laying down detailed rules for implementing certain provisions of Regulation (EU) 2017/1001 of the European Parliament and of the Council on the European Union trade mark, and repealing Implementing Regulation (EU) 2017/1431)

4) Directive approximating the laws of the Member States relating to trade marks (Directive (EU) 2015/2436 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 16 December 2015 to approximate the laws of the Member States relating to trade marks).

In the EU, EU trademark law has created a parallel trademark protection system, having a protection system at national level and another one at EU level. The EU level of protection is governed by the EUTMR, while national protection is governed by national law. This national level has been harmonized by Directive (EU) 2015/2436,

- 243/244 -

thus EU Member States do not enjoy total freedom in the development of their national legislation.

At EU level the protection is granted as "European Union trade mark" ("EU trade mark")[11], which is defined in the EUTMR as follows:

"An EU trade mark may consist of any signs, in particular words, including personal names, or designs, letters, numerals, colors, the shape of goods or of the packaging of goods, or sounds, provided that such signs are capable of:

a) distinguishing the goods or services of one undertaking from those of other undertakings; and

b) being represented on the Register of European Union trade marks ('the Register'), in a manner which enables the competent authorities and the public to determine the clear and precise subject matter of the protection afforded to its proprietor."[12]

"An EU trade mark shall be obtained by registration."[13] This means that the EU is a registration based system, thus only registered marks can enjoy legal protection. Prior to registration, only by usage no marks can acquire protection.

In the EUTMR, as well as in the Directive, functionality is under the rules establishing the absolute grounds for refusal of registration. The provisions in the two legal acts are identical, and the CJEU has interpreted them in the same fashion. "Article 7

1. The following shall not be registered: (e) signs which consist exclusively of:

(i) the shape, or another characteristic, which results from the nature of the goods themselves;

(ii) the shape, or another characteristic, of goods which is necessary to obtain a technical result

(iii) the shape, or another characteristic, which gives substantial value to the goods".[14]

Article 7 (e) (ii) is about technical functionality[15], and Article 7 (e) (iii) treats aesthetic functionality[16]. This third indent's main purpose is to demarcate between trademarks and copyrights and designs.[17]

In Hauck the CJEU stated that the three grounds for refusal of registration operate independently of one another, and thus each of those grounds must be applied

- 244/245 -

independently of the others.[18] In Kit Kat the CJEU added that, it is possible that the essential features of a sign may be covered by one or more grounds of refusal set out under Article 7 (e). However, in such a case, registration may be refused only where at least one of those grounds is fully applicable to the sign at issue.[19]

Thus, if any of the criteria listed in Article 7 (e) or Article 4 (e) is satisfied, a shape or another characteristic in question cannot be lawfully registered.[20] If, despite being functional, a mark has been registered, that trademark shall be declared invalid on application to the European Union Intellectual Property Office (EUIPO) or on the basis of a counterclaim in an infringement proceeding.[21]

Besides these legal acts, the EUIPO issued Guidelines that lists types of advantages that might probably be regarded as "technical." "The examples include product features that: (a) fit with another article; (b) give the most strength; (c) use the least material; (d) or facilitate convenient storage or transportation."[22]

2.2. US law

In the US, there are also two parallel legal frameworks for trademark protection. There exists a legal framework at state level and one at federal level.[23] First trademark laws evolved from case law[24], then in 1946, under the Commerce Clause of the US Constitution, Congress adopted the Lanham Act[25]. The Lanham Act defines trademark as follows:

"The term "trademark" includes any word, name, symbol, or device, or any combination thereof

(1) used by a person, or

(2) which a person has a bona fide intention to use in commerce and applies to register on the principal register established by this chapter, to identify and distinguish his or her goods, including a unique product, from those manufactured or sold by others and to indicate the source of the goods, even if that source is unknown."[26]

As the definition in the Lanham Act indicates it, in the United States trademark rights - contrary to the system of the EU - can not only be acquired through registration, but

- 245/246 -

also by use, this is why the US system is said to be a use-based system.[27] Rights to a trademark can be acquired in one of two ways: (1) by being the first to use the mark in commerce; or (2) by being the first to register the mark with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office ("PTO").[28] The term "use in commerce" means the bona fide use of a mark in the ordinary course of trade, and not made merely to reserve a right in a mark.[29] The functionality doctrine in US trademark law has evolved as a judicially formulated doctrine.[30] Courts excluded functional features from trademark protection for the sake of promoting free competition. In 1998, Congress amended the Lanham Act, and included functionality in it.[31] The case law is described in Chapter III of this paper.

2.3. Comparison of the two systems

There is an obvious difference between the US and the EU trademark systems. The US trademark system is use-based, whilst the EU is solely registration-based. In spite of this, both EU and US lawmakers had the same purposes in mind, when they opted to guarantee trademark rights. Their goal was to protect consumers from confusion and to give producers the possibility to build strong brands. Neither the legislator of the US nor of the EU wanted to grant monopolies towards functional features through trademark law. In both systems the protection of "functionality" belongs to other forms of intellectual property rights, like patents.

In the EU, Article 7 EUTMR gives the basic concept of functionality. Nevertheless, those short rules needed further interpretation by the CJEU. In the US the Lanham Act does not contain any provisions of functionality, and the whole doctrine was elaborated in case-law by the courts.

In the following part this paper presents the case-law of the CJEU, and then the one made by the US Supreme Court.

3. Presentation of the case-law of the CJEU

The Regulation, as described previously, treats functionality under Article 7, and the Directive under Article 4. Both of the two Articles state that a shape, or another characteristic of goods shall not be registered if they are necessary to obtain a technical result (technical functionality), or which gives substantial value to the goods (aesthetic functionality). Since the regulation does not go further, the European Court of Justice had to interpret this passage. In the following part of this paper I present the case law of the CJEU.

- 246/247 -

The Philips case is the first case to be presented. This case was one of the first cases in which the CJEU had to deal with the interpretation of functionality. Besides this, it was the first case to use the expression of "essential characteristics", which later became an important expression in the interpretation of the EU doctrine of functionality. The Court also established that competitors' freedom of choice cannot be limited.

3.1. The Philips case

Picture of the three-headed Philips shaver:

Source of image: https://bit.ly/3kCObA3

The first case in which the CJEU treated the question of functionality was the Philips case. In 1966, Philips developed a new type of three-headed rotary electric shaver. Two years later Philips filed an application and the trademark of the three circular heads was successfully registered.[32] In 1995, Remington, a competing company, began to manufacture and sell in the United Kingdom a similar shaver with three rotating heads also forming an equilateral Source of image: https://bit.ly/3kCObA3 triangle. Philips accordingly sued Remington for the infringement of its trademark, and Remington counter-claimed for revocation of the trade mark registered by Philips.[33] The case ended before the CJEU, which found that the registered shape was functional. The Court in its decision established the rule that registration as a trademark of a sign consisting exclusively of a shape must be refused when the 'essential functional features' of that shape perform a technical function. Moreover, the ground for refusal or invalidity of registration imposed by that provision cannot be overcome by establishing that there are other shapes which allow the same technical result to be obtained.[34] Without this exclusion competitors' freedom of choice would be limited.[35]

The next case to be presented is the Lego case, where the CJEU clarified the relation between a technical result and technical solutions. The Court also gave the definitions of the notions "exclusively" and "necessary" used in the language of Article 7 EUTMR. All of these were important steps toward defining the doctrine of EU functionality. In addition, the CJEU examined the role of an expired patent in the functionality assessment.

- 247/248 -

3.2. The Lego case

Picture of the Lego brick:

Source of image: Case C-48/09 Lego Juris [ECLI:EU:C:2010:516]

Lego had trials in many different countries regarding the registrability of the shape of their brick as a trademark. Different jurisdictions arrived at different outcomes.[36] For instance, the Hungarian Supreme Court found the Lego bricks protectable under trademark law. The main argument of the Hungarian Court was that competitors can use alternative shapes; thus, no competitor is prevented from using the "mechanical" characteristics of the brick.[37] The European Court of Justice ruled differently than the Hungarian Supreme Court and found the bricks unregistrable because of functionality.

The question in the actual case before the CJEU was whether the form of the famous previously patented Lego brick was functional. The stakes for Lego were high, because in the case of functionality the company would lose its registered EU trademark, and its competitors would be able to manufacture the exact same toy brick.

Lego's main argument to claim non-functionality was that the term 'technical solution' should be distinguished from the term of 'technical result', in that a technical result can be achieved by various solutions. In other words, Lego wanted to convince the CJEU, that only those functional features should fall under the Article 7 (e) (ii) of the regulation that are the only ways to achieve a specific technical result. Lego claimed that when there are several shapes which are equivalent from a functional point of view, the protection of a specific shape as a trademark, in favor of an undertaking, does not prevent competitors from applying the same technical solution[38]. The CJEU dismissed those arguments and interpreted the functionality in a far narrower way. The CJEU underlined that the disputed Article 7 (1) e) (ii) must be interpreted in the light of the public interest underlying them, namely to prevent trademark law granting an undertaking a monopoly on technical solutions or functional characteristics of a product.[39] The CJEU added that in the system of intellectual property rights developed

- 248/249 -

in the European Union, technical solutions are capable of protection only for a limited period, so that subsequently they may be freely used by all economic operators.[40]

The Court added that even if a shape of a product which is necessary to obtain a technical result has become distinctive in consequence of the use, it is prohibited from being registered as a trademark.[41] The legislature duly took into account that any shape of goods is, to a certain extent, functional and that it would therefore be inappropriate to refuse to register a shape of goods as a trade mark solely on the ground that it has functional characteristics, and this is why the terms 'exclusively' and 'necessary' become important in the regulation.

By the terms 'exclusively' and 'necessary', the regulation ensures that solely shapes of goods which only incorporate a technical solution, and whose registration as a trade mark would therefore actually impede the use of that technical solution by other undertakings, are not to be registered.[42] 'Exclusively' means that the presence of one or more minor arbitrary elements in a three-dimensional sign, all of whose essential characteristics are dictated by the technical solution to which that sign gives effect, does not alter the conclusion that the sign consists exclusively of the shape of goods which is necessary to obtain a technical result. Article 7(1)(e)(ii) is applicable only where all the essential characteristics of a sign are functional, this ensures that a sign cannot be refused registration as a trademark if the shape of the goods at issue incorporates a major non-functional element, such as a decorative or imaginative element which plays an important role in the shape.[43]

'Necessary' to obtain the technical result intended, that Article 7 (e) (ii) does not mean that the shape at issue must be the only one capable of obtaining that result.[44] The Court stated that the mere fact that the same technical result may be achieved by various solutions, does not in itself mean that registering the shape at issue as a trade mark would have no effect on the availability, to other economic operators, of the technical solution which it incorporates.[45] If solely the existence of alternative shapes would allow to grant trademark rights to its proprietor, that trademark would prevent other undertakings not only from using the same shape, but also from using similar shapes. A significant number of alternative shapes might therefore become unusable for the proprietor's competitors.[46] The CJEU dismissed the arguments of Lego, and enforced the strong competition rationale behind the doctrine of functionality.

In the following three cases (Gömböc, Yoshida, and Rubik's cube) the CJEU furnished further information about the meaning of "essential characteristics" and the correct assessment of it. For instance, the Court ruled, that the relevant public's perception is not relevant regarding the functionality of a feature, and that all elements

- 249/250 -

of a product have to be examined equally on a case-by-case basis. In addition, the Court in Yoshida stated, that the functionality exemption applies to all signs, regardless of being three or two dimensional.

3.3. The Gömböc case

Picture of "Gömböc":

Source of image: https://bit.ly/3oC02iS

Gömböc is a decorative item which has two points of equilibrium, which means that the object always returns to its position of balance. Gömböc's registration as a trademark was rejected by the Hungarian Patent and Trademark Office (Szellemi Tulajdon Nemzeti Hivatala). The producer of Gömböc appealed, and the Hungarian Supreme Court (Kúria) referred questions Source of image: https://bit.ly/3oC02iS to the CJEU to clarify the doctrine of functionality according to the Directive.[47] The CJEU first revoked that in Philips it had already established the rule that registration as a trademark of a sign consisting exclusively of a shape must be refused when the 'essential characteristics' of that shape perform a technical function.[48] The presence of one or more minor arbitrary features in a three-dimensional sign, all of whose essential characteristics are dictated by the technical solution to which that sign gives effect, does not alter the conclusion that the sign consists exclusively of the shape of goods which is necessary to obtain a technical result.[49] The correct application of that ground for refusal requires that the authority deciding on the application for registration of the sign, first, properly identifies the essential characteristics of the three-dimensional sign at issue and, second, establishes whether they perform a technical function of the product concerned.[50] With regards to the first step of the analysis the Court held that the competent authority may either base its assessment directly on the overall impression produced by the sign or, as a first step, examine in turn each of the components of the sign. Consequently, the identification of the essential characteristics of a three-dimensional sign with a view to a possible application of the ground for refusal under Article 3(1)(e)(ii) may be carried out by means of a simple visual analysis of the sign or, on the other hand, be based on a detailed examination in which relevant criteria of

- 250/251 -

assessment are taken into account, such as surveys or expert opinions, or data relating to intellectual property rights conferred previously in respect of the goods concerned.[51] In that regard, the Court has held that the presumed perception by the relevant public is not a decisive factor when applying that ground for refusal, and may, at most, be a relevant criterion of assessment for the competent authority when identifying the essential characteristics of the sign.[52]

Thus, the Court held that Article 3(1)(e)(ii) shall be interpreted as meaning that, in order to establish whether a sign consists exclusively of the shape of goods which is necessary to obtain a technical result, assessment does not have to be limited to the graphic representation of the sign. The perception of the relevant public may also be used to identify the essential characteristics of a sign; however, such information must originate from objective and reliable sources and may not include the perception of the relevant public.[53]

Article 3(1)(e)(iii) "must be interpreted as meaning that the perception or knowledge of the relevant public as regards the product represented graphically by a sign that consists exclusively of the shape of that product may be taken into consideration in order to identify an essential characteristic of that shape. The ground for refusal set out in that provision may be applied if it is apparent from objective and reliable evidence that the consumer's decision to purchase the product in question is to a large extent determined by that characteristic."[54]

3.4. The Pi-Design case (6 March 2014)

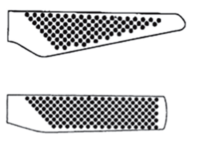

Picture of Yoshida's trademark:

Source of image: https://bit.ly/3qGnZs7

Yoshida Metal Industry Co. Ltd (Yoshida) had a registered trademark in respect of kitchenwares (cutlery, knife, scissors, etc.). In 2007, Pi-Design and Bodum, a competitor of Yoshida, applied for the invalidation of those trademarks on the basis of Article 7 (1)(e)(ii) of Regulation (EC) No 40/94. The mark Yoshida previously had registered was a pattern (black dots on the surface) on knives and on other kitchen aids. Pi-Design alleged that those patterns had functional properties and served as little dents giving the products a non-skid effect. This claim was also sustained by the fact that Yoshida had already had patent rights regarding that design. The Court found that the dots were functional. In its legal analysis the Court first, like in all

- 251/252 -

other cases, pointed to the public interest behind the exclusion set out in Article 7, namely the prevention of monopolies granted by trademark rights. The Court has also made it clear that a correct application of the functionality exemption requires that the essential characteristics of a sign for which registration as a trademark is sought be properly identified by the authority deciding on an application.[55] The identification of those essential characteristics must be carried out on a case-by-case basis, there being no hierarchy that applies systematically between the various types of elements of which a sign may consist. In determining the essential characteristics of a sign, the competent authority may either base its assessment directly on the overall impression produced by the sign, or first examine in turn each of the components of the sign concerned.[56] The Court added that Article 7(1)(e)(ii) applies to any sign, whether two- or three-dimensional, where all the essential characteristics of the sign perform a technical function'.[57] In a second judgement the Court reinforced these principles.[58]

3.5. The Rubik's cube case

Picture of Rubik's cube:

Source of image: C-30/15 P - Simba Toys v EUIPO [ECLI:EU:C:2016:849]

Rubik's cube, just like Lego brick, is a famous toy that was seeking protection through trademark law. Rubik's cube is a cube having nine squares on each side. By being able to rotate each square, the player can adjust the colors on the cube. Seven Towns registered the shape of the toy as a trademark. On the other hand, Simba Toys claimed that the mark consisted exclusively of the shape of the good which was necessary to obtain a technical result, and thus the shape could not have been registered as a trademark. The Court in its decision found Simba's claims well-founded and annulled the decision sustaining the registrability of the shape of Rubik's cube. The Court started its analysis with the competition rationale. The Court stated that the essential characteristics of the sign at issue have to be properly identified. In this case the essential characteristics are a cube and a grid structure on

- 252/253 -

each surface of the cube.[59] Neither the General Court nor the Board of Appeal had found this structure functional. The Court, agreeing with the reasoning of the Advocate General found this an error of law.[60] When examining the functional characteristics of a sign, the competent authority may carry out a detailed examination that takes into account material relevant to identifying appropriately the essential characteristics of a sign, in addition to the graphic representation and any descriptions filed at the time of application for registration. The competent authority would not have been able to analyze the shape concerned solely on the basis of its graphic representation without using additional information on the actual goods.[61]

The last case to be presented is the Kit Kat case, which was one of many litigations between Nestlé and Mondelez, the two chocolate giants. In Kit Kat the English High Court was referring questions to the CJEU, in order to interpret the Directive. In one of these questions the CJEU gave its ruling about the relation between functionality and manufacturing.

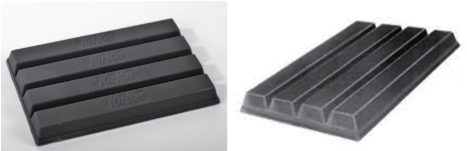

3.6. The Kit Kat case

Picture of Kit Kat:

Source of image: Case C-215/14 - Société des Produits Nestlé [ECLI:EU:C:2015:604] para 11 and 13.

The relationship between Nestlé (the owner of Kit Kat) and Mondelez (the owner of Cadbury) has not been "sweet" in the past years. There had been several litigations between the two parties related to the mark of Kit Kat. In one case Kit Kat wanted to achieve registration as an EU Trademark for its chocolate shape, but Cadbury has successfully prevented it. The "problem" in that case with Kit Kat was that its shape did not acquire distinctiveness in all EU Member States.[62]

In this case Kit Kat wanted a national registration in the UK, and so in 2010 Nestlé filed an application for registration of the three-dimensional sign of the form of "Kit

- 253/254 -

Kat chocolate". In 2011, Cadbury filed a notice of opposition to the application for registration putting forward various pleas, in particular a plea alleging that registration should be refused on the basis of technical functionality.[63] So the High Court of Justice of England and Wales referred under Article 267 TFEU three questions to the CJEU. Two of the three questions were about functionality. One of those questions was in essence, whether Article 3(1)(e)(ii) of the Directive must be interpreted as referring only to the manner in which the goods at issue function or whether it also applies to the manner in which they are manufactured. The CJEU answered this question with a literal interpretation: "the wording of that provision refers expressly to the shape of goods which is necessary to obtain a 'technical result', without mentioning the process for manufacturing those goods." And then added that that the manufacturing method is not decisive in the context of the assessment of the essential functional characteristics of the shape of goods either.[64] The CJEU clarified in this decision that technical functionality refers only to the manner in which the goods at issue function and it does not apply to the manner in which goods are manufactured.[65]

In the national litigation after receiving the answers of the CJEU, the referring court solved the case on the basis of acquired distinctiveness, and thus functionality was not litigated further, because the Court held that Kit Kat's shape did not acquire distinctiveness in the UK, which made the functionality exemption irrelevant.[66]

3.7. Summary of the findings of the CJEU and interim conclusions

The rules that have been established by the CJEU and their consequences are the following:

a. Functionality has to be understood and interpreted in the light of the public interest underlying it, namely the competition rationale. This principle has been repeated in all cases and was always the first sentence of the CJEU in each legal analyses.

b. To examine whether a shape is functional, the following examination must be done:

(i) First the essential characteristics of a good must be identified (the identification of those essential characteristics must be carried out on a case-by-case basis).

(ii) It must be established whether the identified "essential characteristics" perform a technical function of the product concerned. "Central to any functionality assessment is understanding what the technical result is

- 254/255 -

that the sign is meant to achieve. This is (also) a question on which there is very little scholarship and equally little guidance from the CJEU."[67]

(iii) The presence of one or more minor arbitrary features in a three-dimensional sign does not alter the conclusion that the sign consists exclusively of the shape of goods which is necessary to obtain a technical result.

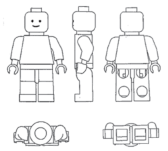

It is crucial for manufacturers to foresee and know whether a shape will be characterized as necessary to achieve a technical result. In order to "predict" whether a shape is registrable, Lukácsi insists on the importance of finding the 'essential characteristics'.[68] According to him, 'functional design' and 'aesthetic design' has to be distinguished in the shape of a good. When more effort has been put into the "aesthetic design" than into the "functional design", and many arbitrary elements have been added to the "functional design" the shape is likely to be registrable as a trademark.[69] A good example to sustain this is described by Ilanah Fhima: "Best-Lock applied unsuccessfully to invalidate a shape mark registration for a LEGO Minifigure on technical functionality grounds. This mark had been registered for "Games and playthings; decorations for Christmas trees": The Grand Chamber upheld the Board of Appeal's finding that none of the essential characteristics (see its head, body, arms, and legs) of the minifigure had a technical function. Even the various apertures under the figure's feet and inside the backs of its legs were held not to have a technical function, because Best-Lock's evidence had not made it clear that these holes were designed to enable the figures to interlock with Lego's building blocks"[70]

Picture of the LEGO Minifigure:

Source of image: T-395/14 - Best-Lock (Europe) v OHMI - Lego Juris Forme d'une figurine de jouet) [ECLI:EU:T:2015:380]

c. The existence of alternative shapes did not affect the CJEU's opinion on functionality. The CJEU ruled in each case that the existence of alternative solutions (shapes) does not make possible for functional features to be registered. The Court saw a risk to competition in letting a functional solution be registered, because

- 255/256 -

that trademark would prevent other undertakings not only from using the same shape, but also from using similar shapes. A significant number of alternative shapes might therefore become unusable for the proprietor's competitors. This also means that the CJEU refused to consider whether the registration of a sign would lead to the grant of monopoly in a technical result to a single undertaking or not.[71] In addition the Court in Philips ruled that the freedom of choice of competitors cannot be limited.

d. The existence of a patent or a previous expired patent is a red flag regarding functionality. "Protection of a shape as a trademark once a patent has expired would considerably and permanently reduce the opportunity for other undertakings to use that technical solution."[72] This excerpt from the CJEU shows how a strong evidence a patent is regarding the functionality of a feature.

e. Even acquired distinctiveness does not change the fact that functional features cannot be protected under trademark law. "The interests at stake are so important that Article 3(1)(e) is one of the few exclusions that cannot be overcome by evidence that the sign serves as an identifier of origin in practice. The law thus tolerates a degree of consumer confusion in order to avoid monopolies in technical characteristics."[73]

f. As described in the Kit Kat case, Article 3 (e) (ii) refers only to the manner in which the goods at issue function and it does not apply to the manner in which the goods are manufactured.[74]

4. Presentation of US functionality case law

In the following part of this paper I briefly present the case law of the United States Supreme Court in the field of functionality. I will start with the cases of Kellogg and Inwood in which the Court developed its "traditional test". In the second part of this chapter I present the In re Morton-Norwich and Qualitex cases, in which the Court treated the "competitive necessity" test. In Re Morton-Norwich is not a case decided by the Supreme Court, however it is an important case for the understanding of the TrafFix decision. In the third part I summarize the TraFfix decision and its aftermath.

4.1. The Kellogg case

In Kellogg, National Biscuit Company was suing Kellogg for unfair competition. National Biscuit Company alleged that Kellogg unfairly used the name "shredded wheat" and unfairly copied the "pillow-shaped" form of its biscuits. The Court found that the name "shredded wheat" was generic and cannot be protectable.

- 256/257 -

Regarding the pillow shape, Kellogg was arguing that the form was functional, and so could not be protected. The machines that made possible to produce shredded-wheat were designed only to produce the pillow-shaped biscuits. The Supreme Court found persuasive, that the form of biscuits was functional, because using another form would have increased the cost of the biscuit and its high quality would have lessened. In the last part of its judgment the Supreme Court even examined whether the products of Kellogg can be differentiated from National Biscuit's products. The Court stated that the Kellogg cartons were distinctive enough, and so that prevented confusion. Even if in hotels cereals are not served in their cartons, this only represents 2,5% of Kellogg biscuits sales. The Court added that it is undoubted that Kellogg is sharing in the goodwill of National Biscuit Company's biscuit, but it is not unfair.[75]

4.2. The Inwood case

In Inwood, the defendant started to produce a generic version of the plaintiff's drug after the plaintiff's patent had expired. Defendant dyed the pills in the same color as plaintiff did. Plaintiff in response sued the defendant for trademark infringement alleging that the pills' color was its trademark. The Supreme Court stated that "a product feature is functional if it is essential to the use or purpose of the article or if it affects the cost or quality of the article". The Supreme Court ruled that competitors were free to copy the color, because in cases of drugs the familiar color of the pills prevented patients from confusing the specific pill with other pills, thus the color-usage was functional in the case.[76]

4.3. The Qualitex case

In Qualitex, the issue was whether the color of Qualitex's product was functional. Qualitex produced dry cleaning press pads that had a specific green-gold color. The Court held that colors can be protected under trademark law, unless they are functional. "Although sometimes color plays an important role (unrelated to source identification) in making a product more desirable, sometimes it does not." And this latter fact indicates that the doctrine of functionality does not impede automatically the use of color as a trademark.

The Court in its analysis first invoked the test applied in Inwood: "The functionality doctrine forbids the use of a product's feature as a trademark where doing so will put a competitor at a significant disadvantage because the feature is "essential to the use or purpose of the article" or "affects its cost or quality" "The functionality doctrine thus protects competitors against a disadvantage that trademark protection might otherwise impose, namely, their inability reasonably to replicate important non-reputation-related product features". The Court than held that "the ultimate test of aesthetic functionality

- 257/258 -

is whether the recognition of trademark rights would significantly hinder competition". In this case the protection of the color did not hinder the interest of competitors.

The Court even added that federal courts were careful and reasoned enough to apply these different functionality rules with sensitivity to the effect on competition. For example a Federal Court has barred the use of black as a trademark on outdoor boat motors. The reason behind this decision was that the color black decreases the apparent size of the motor and ensures compatibility with many different boat colors. In that case the color gave a competitive advantages to that product, and so it was not granted trademark protection (aesthetic functionality).[77]

4.4. The In Re Morton-Norwich case

In Re Morton Norwich Appellant was seeking application for its container configuration as a trademark for spray starch, etc.. The PTO Trademark Attorney found the design to be "merely functional". In addition Appellant also owned a U.S. design patent directed to the mechanism in the spray top. To "solve" the case, the Court listed all the relevant factors to be taken into consideration. The first thing to assess was the "superiority" of the design, then the second inquiry was about whether there were other alternatives available, because the "effect on competition" was "really the crux of the matter". The Court added that costs of manufacturing are also significant in functionality decisions. In this case of the spray bottle, the Court found that there were infinite variety of forms or designs with the same functions, and so allowing the Appellant to exclude others from using its trade dress would not hinder competition. Competitors may copy and enjoy all of its functions without copying the appearance of the spray top.[78] In this case court applied the competitive necessity test.

4.5. The TrafFix case

In TrafFix, the legal issue was whether the dual-spring design of temporary road signs produced by TrafFix were functional. To solve the case, the Supreme Court revisited several questions regarding the doctrine of functionality. One of the principal questions was the effect of an expired patent on a claim of a trade dress infringement since TrafFix owned one before the litigation. Another question was about the relation between the two tests presented in the previous cases.

Regarding the problem of an expired patent, the Court stated that a prior patent has vital significance in resolving a trade dress claim. A utility patent is strong evidence that the claimed features are functional. It puts the burden of proof of non-functionality on the person seeking protection. In this case TrafFix could not prove successfully the non-functionality of the dual spring design. The Court ruled that:

- 258/259 -

"The dual-spring design serves the important purpose of keeping the sign upright even in heavy wind condition, and, as confirmed by the statements in the expired patents, it does so in a unique and useful manner [...] The dual-spring design affects the cost of the design as well, it was acknowledged that the device "could use three springs but this would unnecessarily increase the cost of the device".

The most controversial part of the judgment is the following part, where the Court tried to clarify its previous case-law: "As explained in Qualitex and Inwood, a feature is also functional when it is essential to the use and purpose of the design or when it affects the cost or the quality of the device. The Qualitex decision did not purport to displace this traditional rule. Instead it quoted the rule as Inwood had set it forth. It is proper to inquire into a "significant non-reputation-related disadvantage" in cases of aesthetic functionality, the question involved in Qualitex. Where the design is functional under the Inwood formulation there is no need to proceed further to consider if there is a competitive necessity for the feature".

The Supreme Court added that with functionality having been established, there is no need to consider whether the dual-spring design has acquired secondary meaning. "Here the functionality of the spring design means that competition needs not to explore whether other spring juxtapositions might be used, The dual-spring design is not an arbitrary flourish of the product, it is the reason the device works. Other designs need not to be attempted".[79]

4.6. The controversial afterlife of TrafFix

The TrafFix judgment has become controversial for several reasons. TrafFix has made a distinction between utilitarian and aesthetic functionality but its wording lacks clarity.[80] As a consequence, courts started to interpret and apply it differently.[81] Before rendering the TrafFix decision, lower courts usually decided whether a design feature was functional by means of weighing evidence of the availability of functionally-equivalent alternative design features.[82] After TrafFix, some courts started to interpret the Inwood test as the "traditional test", and the additional language of competitive necessity of Qualitex as a "secondary test". Some courts use the two tests together, meaning that a feature must pass through both tests to get protected. Other courts apply the Inwood test to mechanical features, and the "competitive necessity" test only to aesthetic features.[83]

- 259/260 -

For example, the Fifth Circuit stated that the test for when a design is functional is now (after TrafFix) whether a "feature is essential to the use or purpose of the product or whether it affects the cost or quality of the product."[84] "In contrast, the Federal Circuit read TrafFix differently and concluded that evidence of alternative designs remained a relevant consideration in determinations of functionality."[85] The Federal Circuit ruled: "We do not understand the Supreme Court's decision in TrafFix to have altered the Morton-Norwich analysis.... Nothing in TrafFix suggests that consideration of alternative designs is not properly part of the overall mix, and we do not read the Court's observations in TrafFix as rendering the availability of alternative designs irrelevant. Rather, we conclude that the Court merely noted that once a product feature is found functional based on other considerations there is no need to consider the availability of alternative designs, because the feature cannot be given trade dress protection merely because there are alternative designs available. But that does not mean that the availability of alternative designs cannot be a legitimate source of evidence to determine whether a feature is functional in the first place."[86] Amy B. Cohen interpreted this excerpt as "the Federal Circuit was implicitly suggesting that even if a product design was useful, it would still not be legally "functional" and denied trade dress protection if available alternatives existed."[87]

Mark Alan Thurmon also pointed to these problems in his article "The Rise and Fall of Trademark Law 's Functionality Doctrine". He came to the conclusion that within one year after the TrafFix decision lower federal courts were divided on the question which standard should be used, and this split was directly caused by the decision of the Supreme Court.[88]

5. Differences between the case law of the US and the case law of the EU

Trademark law has similar goals in the two systems, however there are partial differences between them. The first thing that one notices is that the wording and the language used in the statutory provisions and in the case law are different.

A preexisting patent has pivotal importance under both jurisdictions. The CJEU and the US Supreme Court both have stated that the existence of a patent on a feature is a strong evidence in the assessment of functionality. It basically creates a rebuttable presumption of functionality.

Regarding the interpretation of the notion "functional" the CJEU has not uncovered the expression in details. The CJEU mostly gave a strict legal analysis of it. Its analysis revolves around "essential characteristics" that are dictated by technical solutions. As

- 260/261 -

Ilanah Fhima pointed it out "there remains a surprising degree of uncertainty regarding the meaning of its central concepts."[89] In contrast to this, the US Supreme Court has a different style in writing its analysis. The Supreme Court in its judgments gave examples and explanations to make the doctrine more comprehensive and practical. Nevertheless, in TrafFix the Supreme Court broke somehow that clarity, and since then the lower courts are fragmented regarding its interpretation.

The CJEU has clearly rejected the competitive necessity test in every case. The CJEU in every case denied the importance of alternative shapes and solutions.[90] This led to an interpretation that is more formal than its American counterpart. The competitive necessity test makes possible for the courts to assess the concrete market and the competitors' needs. Trademark protection under this test in only denied if the grant of trademark rights would hinder competition in that actual case. The application of the competitive necessity test can result in fair outcomes, because only in those cases will trademark protection be denied, where there is a real market need to copy the litigated feature, thus manufacturers have greater possibilities to enjoy the benefits of trademark law, and only be deprived of it when necessary. In addition, in cases where consumers can identify the source with those "functional" marks, consumers' interests also become protected by eliminating the probable confusions. The rejection of the competitive necessity test under EU law can also be read as a strong value choice of the competition rational. The CJEU even stated in one case that "competitor's free choice" cannot be impeded.

In the United States, despite the post-TrafFix chaos, competitive necessity test is still applied by some courts. Some courts abandoned it when dealing with utilitarian functionality. In my view, the existence of the competitive necessity test in the US, and the absence of it in the EU is the biggest difference between the two systems. This difference is not a side issue, because in the US some marks might "survive" under this test, while in the EU the existence of alternative solutions cannot be examined per se.

In the Kit Kat case the CJEU held that the manner in which the goods are manufactured does not affect the functionality of goods. This approach also differs from the case-law established by the Supreme Court in the United States, where manufacturing efficiency supports a finding of utilitarian functionality.[91] This view of the CJEU narrows the situations in which a feature can be found functional, this restriction can have impacts on competitors.

To summarize, on the one hand, with the rejection of the competitive necessity test the CJEU allowed greater freedom for competitors to copy each other's products. On the other hand, with the restriction on the assessment of manufacturing advantages, it has restricted competitors' possibilities. ■

NOTES

[1] Graeme B. Dinwoodie - Mark D. Janis: Trademarks and unfair competition. Wolters Kluwer, [5]2018. 17.

[2] Mark P. McKenna: A Consumer Decision-Making Theory of Trademark Law. Virginia Law Review, vol. 98., no. 1. (2012) 67-141., JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/41350238.

[3] Howard P. Marvel - Lixin YE: Trademark Sales, Entry, and the Value of Reputation. International Economic Review, vol. 49., no. 2. (2008) 547-576., JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/20486807.

[4] Luís M. B. Cabral: Stretching Firm and Brand Reputation. The RAND Journal of Economics, vol. 31., no. 4. (2000) 658-673., JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/2696353.

[5] A. Samuel Oddi: The Functions of Functionality in Trademark Law. Hous. L. Rev. Vol. 22. (1985) 925.

[6] Anastasia Caton: It's Hip to Be Round: The Functionality Defense to Trademark Infringement. Tul. J. Tech. & Intell. Prop., Vol. 13. (2010) 271.

[7] Oddi op. cit. 927.

[8] Daniel M. McClure: Trademarks and Unfair Competition: A Critical History of Legal Thought. Trademark Rep, Vol. 69. (1979) 307.

[9] Uma Suthersanen - Marc D. Mimler: An autonomous EU Functionality Doctrine for shape Exclusions. GRUR International, Vol. 69., Iss. 6. (2020) 571.

[10] https://euipo.europa.eu/ohimportal/hu/eu-trade-mark-legal-texts.

[11] Regulation (EU) 2017/1001 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 14 June 2017 on the European Union trade mark, Article 1.

[12] Regulation (EU) 2017/1001 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 14 June 2017 on the European Union trade mark, Article 4.

[13] Regulation (EU) 2017/1001 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 14 June 2017 on the European Union trade mark, Article 6.

[14] Regulation (EU) 2017/1001 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 14 June 2017 on the European Union trade mark, Article 7.

[15] Suthersanen-Mimler op. cit.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Suthersanen-Mimler op. cit. 572.

[18] Case C-205/13 Hauck case [ECLI:EU:C:2014:2233].

[19] Case C-215/14 - Société des Produits Nestlé [ECLI:EU:C:2015:604] para 48.

[20] Case C-205/13 Hauck case [ECLI:EU:C:2014:2233] para 10.

[21] Regulation (EU) 2017/1001 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 14 June 2017 on the European Union trade mark, Article 35.

[22] EUIPO Guidelines for Examination of European Union Trade Marks (hereinafter "EUIPO Guidelines"), Part B, Section 4, Ch. 6., https://www.inta.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/TMR-Vol-110-No-03-062920-Final.pdf.

[23] Dinwoodie-Janis op. cit. 9.

[24] Oddi op. cit.928-929.

[25] Lanham Trademark Act, 15 U.S.C. §§ 1051-1127 (1976).

[26] 15 U.S. Code § 1127.

[27] Dinwoodie-Janis op. cit. 46.

[28] https://cyber.harvard.edu/metaschool/fisher/domain/tm.htm.

[29] 15 U.S. Code § 1127. Section 45.

[30] Oddi op. cit. 928.

[31] Kerry S. Taylor: TrafFix Devices, Inc. v. Marketing Displays, Inc. Berkeley Technology Law Journal, vol. 17., no. 1. (2002) 205-223., JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/24120103.

[32] Case C-299/99 Philips [ECLI:EU:C:2002:377] para 11.

[33] Case C-299/99 Philips [ECLI:EU:C:2002:377] para 12-13.

[34] Case C-299/99 Philips [ECLI:EU:C:2002:377] para 84.

[35] Case C-299/99 Philips [ECLI:EU:C:2002:377] para 79.

[36] S. Robert H.C. MacFarlane - Christine M. Pallotta: Kirkbi Ag and Lego Canada Inc. v. Ritvik Holdings Inc.: A Review of the Canadian Decisions. Trademark Rep., Vol. 96. (2006) 575.; and Michael Handler: Disentangling Functionality Distinctiveness and Use in Australian Trade Mark Law. Melb. U. L. Rev., Vol. 42. (2018) 55.; and also: Benjamin Fox Tracy: Lego of My Technical Functionality: The Perpetual Evolution of the European Community's Trademark Law in Comparison with the Law of the United States. Touro Int'l. Rev., Vol. 14. (2011) 412.

[37] Lukácsi, Péter: Védjegy-verseny-közkincs: a térbeli megjelölések védjegyoltalma. Doktori disszertáció. 2018. https://edit.elte.hu/xmlui/handle/10831/37483

[38] Case C-48/09 Lego Juris [ECLI:EU:C:2010:516] para 30.

[39] Case C-48/09 Lego Juris [ECLI:EU:C:2010:516] para 43.

[40] Case C-48/09 Lego Juris [ECLI:EU:C:2010:516] para 46.

[41] Case C-48/09 Lego Juris [ECLI:EU:C:2010:516] para 47.

[42] Case C-48/09 Lego Juris [ECLI:EU:C:2010:516] para 48.

[43] Case C-48/09 Lego Juris [ECLI:EU:C:2010:516] para 52.

[44] Case C-48/09 Lego Juris [ECLI:EU:C:2010:516] para 53.

[45] Case C-48/09 Lego Juris [ECLI:EU:C:2010:516] para 54-55.

[46] Case C-48/09 Lego Juris [ECLI:EU:C:2010:516] para 56-59.

[47] Pfv.IV.21.920/2017. n. case.

[48] Case C-237/19 Gömböc [ECLI:EU:C:2020:296] para 26, Case C-299/99 Philips [ECLI:EU:C:2002:377] para 79.

[49] Case C-237/19 Gömböc [ECLI:EU:C:2020:296] para 26, Case C-48/09 Lego Juris [ECLI:EU:C:2010:516] para 52.

[50] Case C-237/19 Gömböc [ECLI:EU:C:2020:296] para 28, Simba Toys v EUIPO 40 42, Lego para 68, 72 and 84.

[51] Case C-237/19 Gömböc [ECLI:EU:C:2020:296] para 29.

[52] Case C-237/19 Gömböc [ECLI:EU:C:2020:296] para 31.

[53] Case C-237/19 Gömböc [ECLI:EU:C:2020:296] para 63.

[54] Case C-237/19 Gömböc [ECLI:EU:C:2020:296] para 63.

[55] Case C-337/12 Pi-Design and Others v Yoshida Metal Industry [ECLI:EU:C:2014:129] para 46.

[56] Case C-337/12 Pi-Design and Others v Yoshida Metal Industry [ECLI:EU:C:2014:129] para 47.

[57] Case C-337/12 Pi-Design and Others v Yoshida Metal Industry [ECLI:EU:C:2014:129] para 51.

[58] Case C-421/15 P Yoshida Metal Industry v EUIPO [ECLI:EU:C:2017:360]

[59] Case C-337/12 Pi-Design and Others v Yoshida Metal Industry [ECLI:EU:C:2014:129] para 36-41.

[60] C-30/15 P - Simba Toys v EUIPO [ECLI:EU:C:2016:849] para 44-45.

[61] C-30/15 P - Simba Toys v EUIPO [ECLI:EU:C:2016:849] para 49-50.

[62] C-84/17 P - Société des produits Nestlé v Mondelez UK Holdings & Services [ECLI:EU:C:2018:596].

[63] Case C-215/14 - Société des Produits Nestlé [ECLI:EU:C:2015:604] para 15-17.

[64] Case C-215/14 - Société des Produits Nestlé [ECLI:EU:C:2015:604] para 52-54.

[65] Case C-215/14 - Société des Produits Nestlé [ECLI:EU:C:2015:604] para 57.

[66] Société des Produits Nestlé SA -v- Cadbury UK Ltd [2017] EWCA Civ 358., https://www.judiciary.uk/judgments/societe-des-produits-nestle-sa-v-cadbury-uk-ltd/.

[67] Ilanah Fhima: Funcitionality in Europe: When Do Trademarks Achieve a Technical Result? The Trademark Reporter, The Law Journal of International Trademark Association, Vol. 110. No 3., May-June 2020., https://www.inta.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/TMR-Vol-110-No-03-062920-Final.pdf 679.

[68] Lukácsi, Péter: Funkcionalitás a védjegyjogban. Védjegyvilág, 2005/1.; Náthon, Natalie: Az új típusú védjegyek az Európai Unióban. PhD Értekezés. Pécs, 2009. https://ajk.pte.hu/sites/ajk.pte.hu/files/file/doktori-iskola/nathon-natalie/nathon-natalie-vedes-ertekezes.pdf.

[69] S. Lukácsi (2005) op. cit.

[70] Fhima op. cit. 682-683.; T-395/14 - Best-Lock (Europe) v OHMI - Lego Juris (Forme d'une figurine de jouet) [ECLI:EU:T:2015:380]; C-451/15 P - Best-Lock (Europe) v EUIPO [ECLI:EU:C:2016:269].

[71] S. Fhima op. cit.

[72] Case C-48/09 Lego Juris [ECLI:EU:C:2010:516] para 46.

[73] S. Fhima op. cit.; Case C-371/06 - Benetton Group SpA v. G-Star International BV [ECLI:EU:C:2007:542], para 27.

[74] Case C-215/14 - Société des Produits Nestlé (ECLI:EU:C:2015:604) para 57.

[75] Kellogg Co. v. National Biscuit Co. United States Supreme Court 305 U.S. 111 (1938).

[76] Inwood Laboratories, Inc. v. Ives Laboratories, Inc. United States Supreme Court 456 U.S. 844 (1982).

[77] Qualitex Co. v. Jacobson Products Co. United States Supreme Court 514 U.S. 159 (1995).

[78] 671 F.2d 1332 (1982).

[79] TrafFix Devices, Inc. v. Marketing Displays, Inc. United States Supreme Court 532 U.S. 23 (2001).

[80] Harold R. Weinberg: Trademark Law, Functional Design Features, and the Trouble with Traffix. J. Intell. Prop. L., Vol. 9., Iss. 1. (2001).

[81] Dinwoodie-Janis op. cit. 204-205 and 206.

[82] Weinberg op. cit. 23.

[83] S. Dinwoodie-Janis op. cit.

[84] 289 F.3d 351 (5th Cir. 2002). In: Amy B. Cohen: Following the Direction of Traffix: Trade Dress Law and Functionality Revisited, IDEA: The Intellectual Property Law Review, Vol. 50, Issue 4. (2010) 640.

[85] Cohen op. cit. 641.

[86] Valu Eng'g, Inc. v. Rexnord Corp., 278 F.3d 1268, 1272-73 (Fed. Cir. 2002); Cohen op. cit. 642.

[87] S. Cohen op. cit.

[88] Mark Alan Thurmon: The Rise and Fall of Trademark Law's Functionality Doctrine. Fla. L. Rev., Vol. 56. (2004).

[89] Fhima op. cit. 696.

[90] S. C-205/13 Hauck case [ECLI:EU:C:2014:2233].

[91] Fhima op. cit. 667.

Lábjegyzetek:

[1] The Author is PhD student (Eötvös Loránd University).