Paola Andrea Villegas Ramirez[1]: An analysis of the 10 years of the FTA between the EU and Colombia, Peru, and Ecuador - opportunities and challenges (Annales, 2024., 177-200. o.)

https://doi.org/10.56749/annales.elteajk.2024.lxiii.10.177

Abstract

This article examines the first decade of implementation of the Free Trade Agreement (FTA) between the European Union (EU) and Colombia, Peru, and Ecuador, focusing on trade relations, economic impacts, and legal developments. The analysis highlights both the opportunities and challenges that have emerged since the adoption of the FTA, emphasising tariff liberalisation, export growth, and improved market access for key sectors, particularly coffee and pharmaceuticals. Despite these benefits, the study identifies significant shortcomings in terms of sustainable development, particularly with regard to labour rights and environmental protection in Colombia. It concludes that while the FTA has promoted economic cooperation and regulatory harmonisation, the expected progress on sustainable development remains slow. Strengthened enforcement mechanisms and further regulatory adjustments are recommended to achieve the broader objectives of the agreement.

Keywords: EU-Colombia trade agreement; sustainable development; market Access; trade balance; legal harmonisation

I. Introduction

The European Union (hereinafter EU), as a member of the World Trade Organization (WTO), the world's largest economic bloc,[1] and whose economic policies significantly impact the world economy, always seeks to improve its global trade relations. In this

- 177/178 -

regard, the European Commission, in its 2018 report on the implementation of Free Trade Agreements (FTAs),[2] states that the EU implements different types of Trade Agreements according to their content and goals, which can mainly be classified into four categories: The 'First generation of trade agreements' mostly focused on tariff liberalisation and concluded before 2006; 'Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Areas' (DCFTAs) were usually adopted with EU neighbouring countries and focused on approaching the commercial legislation of the parties and supporting regional integration into the EU market. Moreover, there are Economic Partnership Agreements (EPAs) whereby the EU provides wider trade assistance to support its partners in implementing the agreement. Finally, there is the new generation of Free Trade Agreement' (FTAs) that, besides tariff liberalisation, also include obligations on services, investment, public procurement, regulatory issues, and particular provisions on trade and sustainable development (TSD).[3]

The EU and the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States (CELAC)[4] have been trading partners for many years, as most of them are also WTO members. Colombia is a member of CELAC, but at the South American level, it is also part of the Andean Community (CAN). Moreover, the EU is the largest investor in Latin America and the second most significant trade partner; thus, the EU has used different association mechanisms with Latin American nations, such as trade agreements, to achieve further regional integration.[5] In 2012, the EU signed two agreements with Latin American countries.[6] First, the Association Agreement between the EU and Central America, and later the multilateral Free Trade Agreement between the European Union and Colombia, Peru, and Ecuador[7] (hereinafter FTA), one of the known "New Generation" of FTAs of the EU. This FTA was signed on December 21,

- 178/179 -

2012, by the EU, Colombia and Peru, and Ecuador has also been a member since 2016, and it entered into force on October 14, 2024.[8]

This document reviews the ten-year implementation of the FTA in the EU and Colombia, focusing on its economic impact and legal developments. It examines the associated trade relations, particularly imports and exports, and assesses the broader implementation of the agreement, including its TSD provisions. It also examines how, while the FTA has increased trade and opened markets, progress on environmental, peace and labour issues remains slow in less developed countries such as Colombia. The analysis covers the background of the EU-Colombia FTA, initial objectives, and evaluations for 2018[9] and 2022,[10] as well as reports from Colombian institutions and FTA subcommittees.

In addition, this document will show that some of the legal instruments created by both parties have been explicitly adopted in the context of the FTA. However, the EU has created most of the rules related to the topics covered by the agreement as a homogeneous legal framework applicable to those trade agreements to which the EU is a party. I chose coffee and pharmaceutical products as illustrations of the EU-Colombia trade relationship to analyse the legal conditions and progress exercised by the EU with regard to Colombian coffee imports, as well as the legal framework applicable to pharmaceutical products imported from the EU to Colombia.

Finally, this document concludes that although the trade agreement has had a positive economic impact, as it has helped to reduce tariffs and promote the expected opening of each other's markets, slow progress on sustainable development undermines its effectiveness and it will require a more significant effort by the parties if the envisioned objectives in this area are to be achieved along with general compliance with the FTA. It is also evident that the EU is the main driver of legal developments produced by the parties, being the dominant party to the agreement.

- 179/180 -

II. Relationship between the EU and Colombia

The EU and Colombia have had a long-standing relationship based on economic cooperation and political dialogue for a long time, and significant efforts have been made in the last two decades to achieve peace and work to reach sustainable development.

The Andean Community (CAN) was founded with the signing of the Cartagena Agreement in 1969, but this Regional Trade Agreement only entered into force in 1988.[11] Currently, there are four member countries of this community: Colombia, Peru, Ecuador, and Bolivia (all are members of the WTO).

For its part, the European Union has been a member of the WTO since 1 January 1995[12] and has maintained economic integration relations with the Andean Community ever since. For several years, the Andean countries were beneficiaries of the preferential tariffs under the EU's General Scheme of Preferences (GSP) until the multilateral FTA concluded between the EU and Colombia, and Peru was signed on 26 June 2012, which covers further topics besides the customs and tariffs duties for its signatories.

This FTA has been provisionally applied in Colombia since 1 August 2013, in Peru since 1 March 2013, and Ecuador was added to the agreement in November 2016 and provisionally applied since 1 January 2017. From the EU's side, the FTA has been provisionally applied since 1 August 2013.[13]

Bolivia has the option to become a member of the FTA, based on Article 329 of the agreement, and currently gains benefits from the GSP+ in its trade relations with the EU. Moreover, Bolivia is the biggest Latin American beneficiary of bilateral EU development assistance.[14]

Since the adoption of the FTA, Colombia has become the EU's most important trading partner in the Andean Community and the fifth largest in Latin America, with a trade volume of EUR 8,305 million in 2020.[15] The EU is Colombia's third-

- 180/181 -

largest trading partner and the main source of foreign direct investment.[16] Beyond trade, the FTA has strengthened cooperation in areas such as development and diplomacy. The EU played an important role in facilitating the 2016 peace agreement with the FARC (Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia) and continues to support its implementation through initiatives such as the €130 million European Peace Fund for post-conflict efforts.

III. FTA Content and current implementation at the economic level

1. FTA Content

The FTA document has 14 titles, 14 annexes, and one joint declaration. Among its elements are, Title I on initial provisions, Title II on the Trade Committee and its functions as a guarantor of the implementation of the FTA, Title III on trade in goods, Title IV on trade in services and electronic commerce, Title VII on intellectual property, Title IX on the TSD provisions, Title XII on dispute settlement, and Title XIII on technical assistance. In turn, the annexes are very precise on specific subjects such as tariff elimination schedules (Annexe I), agricultural safeguards measures (Annexe IV), sanitary and phytosanitary measures (Annexe VI), government procurement (Annexe XII), and the mediation mechanism for non-tariff measures (Annexe XIV).

The accession of Ecuador was concluded with a protocol signed for the EU, Colombia, Peru, and Ecuador, which includes the same Annexes (annexes XV-XX) already applicable for the EU, Colombia, and Peru.

The FTA, in its Title XIII on technical assistance and trade capacity building, requires the creation of a Trade Committee formed by delegating people from each State Party. This committee has the main responsibilities of supervision, evaluation of the FTA's application, operational facilitation to develop the agreement, and monitoring the work of all the specialised bodies (such as sub-committees). In addition, there are eight specialised sub-committees for eight different areas covered by the agreement, namely Agriculture; Customs, Market Access, Intellectual Property; Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures; Trade Facilitation and Rules of Origin; Government Procurement; Technical Obstacles to Trade; and Trade and Sustainable Development.

- 181/182 -

2. Current implementation

In 2012, the European Commission published the 'Assessment of the Economic Impact of the Trade Agreement between the EU and signatory countries of the Andean Community (Colombia and Peru)'[17] once the structure of the final trade agreement draft had been completed. This assessment established several economic objectives to be achieved, but overall, it forecasted a positive impact on the gross domestic product (GDP) of the parties. For Colombia, it predicted growth in its GDP by 0.4% (around 500 EUR million), and for the EU, 0.05% (2.3 EUR million).[18] Moreover, other matters were expected to improve market access, such as the opening of the government procurement and services market and eliminating tariffs, which could save around 500 EUR million/year on import duties. Regarding trade benefits by sectors, it is believed that the FTA would mainly benefit Colombia in four areas: agricultural and fishing products, services, industrial and raw materials, and investment.

The 2018 ex-post evaluation by the European Parliament Research Service assessed the impact of the EU-Colombia FTA from its provisional application in 2013 to 2017. Economically, Colombia's macroeconomic performance improved, with a cumulative GDP growth rate of 3.95% from 2005 to 2016. However, post-FTA, GDP growth slowed from 4.23% (2005-2013) to 1.66% (2014-2016). Similarly, GDP per capita growth declined after the implementation of the FTA, from 3.2% to 1.06%. While the FTA had a positive impact on Colombia's economy, these figures indicate slower growth after its implementation due to the stricter requirements of the TSD provisions and the more rigorous testing of food products from the EU side.[19]

Bilateral trade has shown mixed results. The value of Colombian exports to the EU fell significantly, from €8,634 million in 2012 to €5,606 million in 2017, a decrease of 35%. Meanwhile, EU exports to Colombia increased by 8.6% from 2012 to 2017, reaching EUR 5,986 million, with growth of 10.5% compared to 2016.[20] Colombia's exports mainly consist of agricultural and mineral-energy products, which are affected by fluctuations in the price of coal, which is directly reflected in the statistics presented above. On the other hand, the EU's exports are goods of higher value, such as pharmaceuticals, vehicles, and machinery, whose value does not constantly fluctuate, thus contributing to a trade imbalance.

- 182/183 -

Later, in 2022, the European Commission published the 'Ex post evaluation of the implementation of the Trade Agreement between the EU and its Member States and Colombia, Peru and Ecuador', covering the FTA implementation period of 2013-2019. It declares that

"EU sectors benefitting most in the form of increased exports to Colombia are various types of manufactured products, such as vehicles (an increase of USD 974 million or 122% compared to no Agreement), machinery (USD 801 million/39%), electronics (USD 334 million/49%), and others. Garments, leather, and processed food (notably meat products and vegetable oils and fats) are also expected to have benefited substantially. Among Colombian sectors, the Agreement led to the highest increases in exports to the EU for fruit and vegetables (an increase of USD 64 million or 50% compared to the situation without the Agreement in place in 2020), other food products (USD 50 million/87%) and chemicals (USD 33 million/36%), as well as garments, and rubber and plastic products."[21]

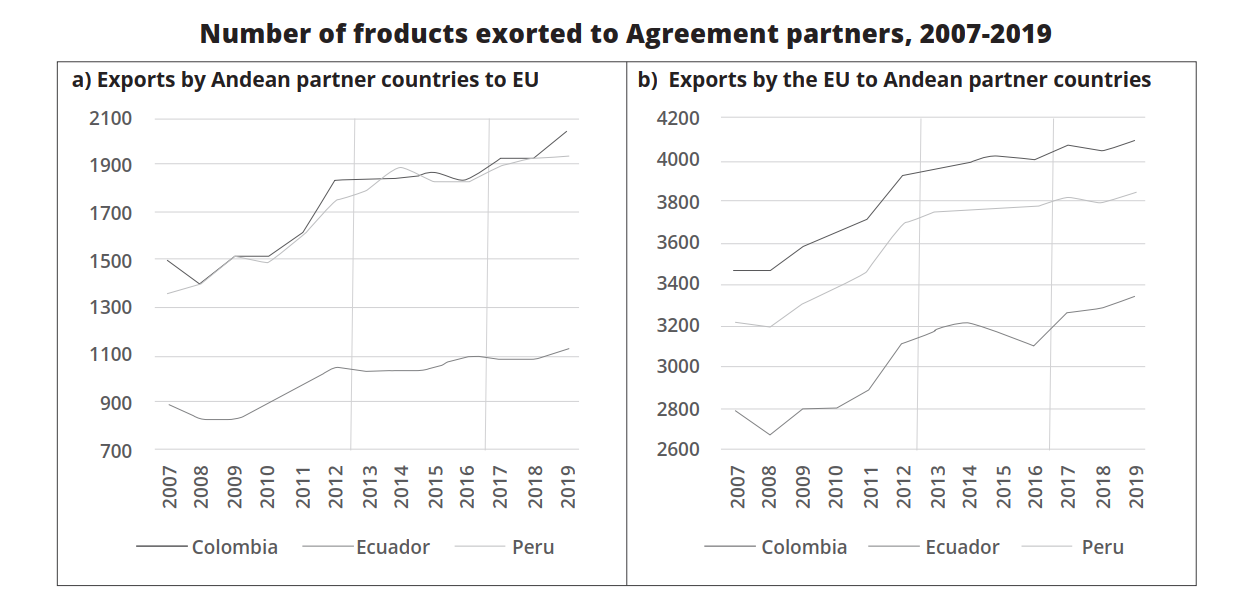

Figure 1. The COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 disrupted global trade, including between the EU and Colombia[22]

No specific FTA reports were issued for this period, but Colombia's Ministry of Commerce, Industry and Tourism[23] noted a decrease in both exports and imports, which reduced the trade deficit. In 2020, Colombia's main exports to the EU were gold and coffee (19% each), with coal falling to third place (10%). In 2021, coal regained its

- 183/184 -

top position (19%), while coffee remained in second place (18%). On the import side, pharmaceuticals, especially vaccines and COVID-19-related inputs, became the largest category (20% in 2020 and 17% in 2021), overtaking mechanical and electrical machinery. The pandemic affected trade by shifting demand towards essential goods such as pharmaceuticals and reducing trade in other sectors.

The Trade Committee and subcommittees overseeing the implementation of the FTA continued their work during the pandemic, mostly through online meetings since 2020. Reports of their discussions are available on the EU CIRCABC website and on the Colombian Ministry of Trade and Industry website.[24] The committee adopted its rules of procedure early on and applied them to the subcommittees. They also designated arbitrators, established a Code of Conduct and outlined procedures for dispute settlement, particularly under the Trade and Sustainable Development (TSD) provisions, thus ensuring a structured approach to managing compliance with the FTA.

From an economic point of view, the FTA implementation reports issued by the EU and Colombian institutions show progress in trade cooperation and tariff liberalisation as planned since the negotiation of the treaty. However, these reports also show that this FTA is one of the agreements in which the least developed party (in this case, Colombia) is the one mainly obliged to adapt to the commercial standards and legal guidelines created by the stronger party to the agreement; in other words, there is a kind of implicit harmonisation of commercial conduct and a legal framework created by the stronger party to the trade agreement.

Likewise, it should also be noted that although the official reports of the FTA are mainly positive in terms of its economic impact, other commercial actors in Colombia have publicised their discontent with the trade agreement because, since 2015, Colombia has had a deficit in its trade balance.[25] Although some products have penetrated the European market, agricultural producers (mainly farmers) feel that they need more partnerships, training, and safety guarantees (such as food safety standards, quality control and phytosanitary measures) to meet all the requirements stipulated by the EU, because, from their point of view, the FTA has affected the marketability of some products, such as milk and rice, produced in Colombia.[26]

- 184/185 -

IV. TSD provisions as a challenge to FTA's implementation

Sustainable development in the EU is based on three pillars: economic, environmental and social. The EU aligns its trade policy with these pillars to promote human rights, social justice and high environmental and labour standards. EU trade agreements, in particular the new generation of free trade agreements (FTAs), include trade and sustainable development (TSD) chapters to promote these goals. However, studies have shown weaknesses in the implementation of TSD provisions, mainly due to the lack of enforceable sanctions and unclear guidelines for dispute settlement. Despite these challenges, the EU continues to use trade agreements as a tool to promote sustainable development with its partners.[27]

In response, the EU Commission published the "15-Point Action Plan"[28] in 2018, aimed at improving the enforcement of TSD chapters. By 2021, the Commission had launched a review of the Action Plan and requested an independent study to further assess the effectiveness of TSD implementation in trade agreements. This plan aims to strengthen compliance with the EU's sustainability goals.

This study was conducted by the London School of Economics and Political Science - LSE Consulting, which extensively and critically reviewed different approaches to TSD chapters in eleven EU FTAs and made some comparisons with TSD provisions applied in US agreements. This study showed that the US uses TSD provisions before signing trade agreements as a requirement in negotiations and as an incentive to promote effective environmental reforms. In this sense, "the US sanction-based approach is more likely to have an impact ex-ante (before FTA ratification), while the EU's soft approach is said to yield greater results ex-post (after ratification)".[29]

In 2022, based on the information obtained in the requested LSE study, the open public consultation on the review of trade and sustainable development, and the reports issued by the TSD subcommittees of the various EU FTAs, the European Commission published its final review report on the 15-Point plan,

- 185/186 -

which sets out six key action points to enhance the effectiveness and enforcements of FTA TSD provisions.[30]

1. TSD chapter and its application in the EU- Colombia/Peru/Ecuador FTA

The EU-Colombia, Peru, and Ecuador FTA includes Trade and Sustainable Development (TSD) provisions in Title IX aimed at strengthening commitments to human, labour, and environmental rights. These provisions are consistent with International Labor Organization (ILO) standards and environmental agreements such as CITES and the Kyoto Protocol. The agreement addresses issues such as sustainable forest management, combating illegal fishing, cooperation on climate change, and ensuring equal working conditions. It also emphasises transparency through consultations with civil society.

However, implementing the provisions of the TSD in Latin American countries such as Colombia is challenging due to long-standing problems of corruption, economic instability, and violence. These factors make achieving sustainable development goals more difficult than in more developed countries such as EU Member States.

The 2018 assessment of the implementation of the FTA highlighted the important role of the EU in supporting Colombia's peace agreement with the FARC, contributing to its success through negotiation, implementation and monitoring. The creation of the EU Trust Fund for Colombia in 2016 and annual budgets for post-conflict programs further strengthened this cooperation. In addition, Colombia has passed legislation to facilitate international agreements such as the Paris Agreement and the Minamata Convention on Mercury. However, challenges remain in the area of the protection of human and labour rights, particularly in the mining and palm oil sectors, where Colombia has failed to ensure adequate consultation with indigenous and Afro-descendant communities, a legal requirement for land-impacting projects.[31]

The FTA evaluation published in 2022 proved that although the signing of the peace agreement between the Colombian government and FARC was an excellent achievement in terms of peace, statistics from later years showed that human rights violations persist in other areas, such as violence against trade union activists or civil society in general. The Commission also highlighted some problems that have been recurrent since the beginning of the implementation of the FTA, such as the lack of participation by civil society in the implementation of this agreement, the violation

- 186/187 -

of some vulnerable population groups' human and labour rights, such as those of farmers, indigenous communities, and people of African descent. Overall, although the FTA has produced a more open market, especially for agricultural goods, this increase in demand is not aligned with current labour conditions.

Furthermore, the latest available report (2021) of the Subcommittee on Trade and Sustainable Development[32] provides information on recent programs and initiatives by the parties on sustainable development, with a particular focus on the challenges generated by the COVID-19 pandemic. For example, the EU presented its progress through the Next Generation program implemented in February 2021. Colombia, for its part, explained the range of measures applied to mitigate the effects of the pandemic, such as the 'Formal Employment Support Program', and the relief program for workers whose contracts had been suspended since the start of the COVID-19 confinements. In addition, the EU acknowledged Colombia's efforts and welcomed the information thus presented but insisted that measures to protect social and union leaders must still be improved, and dialogue with civil society must be strengthened.

V. Legal development since the adoption of the FTA

Since the FTA began to apply between the parties, some specific rules have been issued for implementing this agreement. On 30 July 2013, the European Commission published Regulation (EU) 740/2013[33] on derogations from the rules of origin set out in Annexe II to the Trade Agreement, which determines the conditions for the application of these exceptions for imports from Colombia. Regulation (EU) 741/2013[34] on opening and providing for the administration of Union tariff quotas for agricultural products originating in Colombia was also issued on that date.

- 187/188 -

Moreover, Regulation (EU) 19/2013[35] states the rules for the stabilisation mechanism applicable to bananas exported from Colombia and Peru to the EU due to the enormous quantities imported. In 2017, this regulation was amended by Regulation (EU) 2017/540,[36] implementing the stabilisation mechanism for bananas exported from Ecuador. Other EU norms applicable to the subjects covered by the agreement have not been issued exclusively due to this trade agreement; in other words, they are, in general, legal measures that can be applied to similar EU agreements.

Colombia has implemented several regulations to improve the effectiveness of its trade agreement with the EU, influenced by the subcommittees that oversee the implementation of the FTA. Decree 1636 of 2013[37] established the conditions for the fulfilment of Colombia's market access commitments. Similarly, Law 1609 of 2013[38] outlined the government's responsibility to adjust tariffs and customs regulations to facilitate trade agreements. Based on this law, Decree 390 of 2016 introduced new customs regulations in line with international agreements, which were later replaced by Decree 1165 of 2019,[39] which governs Colombia's current customs regime. In 2021, Decree 360 of 2021[40] introduced a simplified procedure for customs users, which

- 188/189 -

grants certain benefits once compliance with the requirements of the Colombian customs authority is achieved, streamlining international trade transactions for qualified users.

Nevertheless, as indicated at the beginning of this document, another issue of interest in the legal development since the FTA is the study of the legal framework applicable to imports and exports between the parties, in particular coffee and pharmaceutical products, as the key goods driving the EU-Colombia trade relationship.

The FTA includes (general and specific) provisions applicable to imports and exports between the parties; however, particular rules on trade in goods under Title III of the Agreement and Annexes IV and VI on agricultural safeguard measures and sanitary and phytosanitary standards are relevant to the export of coffee from Colombia to the EU, and the import of EU pharmaceuticals to Colombia.

1. Coffee exports from Colombia to the EU

Coffee is one of the world's most in-demand products, grown in more than 70 countries, with Latin America being the largest exporting region. The EU is the largest coffee market, consuming 44% of the world's coffee, with Germany, Italy and France accounting for 10% of global consumption.[41] Each EU citizen consumes an average of 4.67 kilos of coffee per year, leading the EU to import 46.2 million bags of green coffee, 0.7 million bags of roasted coffee and 2 million bags of soluble coffee per year.[42] Colombia is a major player in the coffee industry, with large exports to the EU, Japan and the U.S., supported by the Colombian Coffee Federation (FNC) and its internationally recognised "Café de Colombia" brand.[43]

Approximately 86% of Colombian coffee is exported as green coffee, and the remaining amount (nearly 60 kg bags or 120 thousand tons) is processed as instant or roasted coffee and is consumed locally. Colombia is also an important producer of certified coffee worldwide. This country has joined seven certification programs, among which Colombia is the largest producer of Fairtrade-certified coffee and the second-largest producer of Rainforest Alliance-certified coffee.[44]

- 189/190 -

In 2013, when the FTA started to be applied provisionally, imports of Colombian speciality coffee to the EU reached EUR 606.3 million, with the strongest demand from Switzerland and Germany, representing 31% and 18% (respectively) of total coffee imports during that year.[45] By 2022, Colombian coffee imports to the EU were valued at EUR 758 million.[46] These numbers may not represent a significant increase in the value of Colombian coffee imports after nine years of FTA implementation; however, a deep analysis of these amounts requires taking other external variables into account, such as changes in the price of the product or the particular circumstances of production each year in Colombia.

a) EU legal framework

The coffee industry at the EU level is covered by the EU food safety policy "Farm to fork food", which sets high standards for plant protection, animal health and welfare, and specifies the need for clear information on origin, among other biosecurity requirements, to ensure the quality of food products and the protection of human health in the EU.[47] To this end, the EU has established an extensive legal framework covering various aspects of food production, such as hygienic standards and monitoring residues, pesticides, and contaminants. These rules generally apply to all foodstuffs distributed in the territory of the Union; it means that they also apply to food products produced by third countries and imported into the EU.

For the export of coffee to the EU, it is possible to classify the legal requirements applicable to this product into four groups: food safety, food contaminants, general labelling - packaging requirements, and official controls and enforcement.

Food Safety

Regulation (EC) 178/2002, also known as the "General Food Law Regulation",[48] was adopted in 2002 and serves as the primary framework for food safety legislation in the EU. It outlines the principles and procedures for all stages of food and feed production and distribution. A key feature of this Regulation is the "Rapid Alert System for Food and Feed" (RASFF),[49] which allows for the rapid exchange of information between Member States in the event of food safety risks. The regulation also established the

- 190/191 -

"European Food Safety Authority" (EFSA),[50] an independent agency that provides advice on risks associated with food production and distribution.

Regulation (EU) 2017/625[51] lays down general rules on the hygiene of foodstuffs during production, processing and distribution. It aims to protect consumer interests, ensure fair trade practices, and regulate the use of materials in contact with food. This Regulation also plays a crucial role in the enforcement of food safety rules, in particular through official controls. In addition, Regulation (EC) No 852/2004 on food hygiene applies to specific products such as coffee and ensures compliance with the Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Points (HACCP) principles throughout the food production chain. Together, these regulations ensure the safety and integrity of food within the EU.

The Commission's Health and Consumers Directorate General has also contributed in this area by publishing a guidance document, "Key questions related to import requirements and the new rules on food hygiene and official food controls",[52] addressed to the competent food authorities and commercial food operators from the EU Member States and third countries, in order to address some key questions regarding the implementation of food hygiene import requirements.

Food Contaminants

Food contamination is another critical issue in food security, as it can occur at different stages of food production under different circumstances. Coffee is obtained from a basically agricultural process; therefore, contamination control begins with the cultivation process, where the monitoring of pesticides used on coffee plants is relevant. Later, norms related to food contact materials in labelling are essential in the packaging and transport phases of the product.

- 191/192 -

Regulation (EC) 1881 of 2006[53] sets the maximum levels of contaminants allowed in food and divides them into nine groups listed in an Annexe. If a product exceeds these contaminant limits, it cannot be sold or distributed in the EU. Each EU Member State is responsible for testing food for contaminants and reporting the results to the EFSA. As a food product, coffee is subject to specific contaminant regulations, particularly for mycotoxins such as ochratoxin A, which can contaminate green coffee beans during production, post-harvest or transportation. Regulation (EU) 2022/1370[54] sets the maximum level of Ochratoxin A at 3% for roasted coffee and 5% for ground and instant coffee.

In addition to mycotoxins, coffee may be contaminated by hydrocarbons such as polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) and mineral oil aromatic hydrocarbons (MOAHs) during the drying process. Although coffee is not specifically included in Regulation (EU) 835/2011, this regulation addresses PAHs in all foods. Some EU Member States, such as Germany, have issued guidelines about the potential risks of MOAH contamination in green coffee.[55] These hydrocarbons, particularly MOAHs, may be carcinogenic, although the EU has not set a specific maximum level for them.

Another potential contaminant in coffee is acrylamide, a carcinogenic substance formed during roasting at temperatures above 120 °C. Regulation (EU) 2017/2158 limits the amount of acrylamide in roasted coffee to a maximum of 400 μg/kg.[56] These regulations aim to protect consumer health by controlling the presence of harmful substances in coffee and other food products.

Pesticide control is a critical aspect of food safety, especially for plant protection products. Regulation (EC) 396/2005[57] sets the maximum residue levels (MRLs) of pesticides allowed in food of plant and animal origin. The European Commission's EU Pesticides Database allows users to search for MRLs, active substances and emergency authorisations for plant protection products in the - Member States.[58] Regulation (EU)

- 192/193 -

2023/334,[59] adopted in February 2023, amended Annexes II and V of Regulation (EC) 396/2005 to update the MRLs for clothianidin and thiamethoxam in coffee beans, setting the limit at 0.05 mg/kg. This will ensure that pesticide residues in food are kept at safe levels.

EU food safety legislation also covers food contact materials (FCMs) to prevent contaminants from migrating from packaging to food. These materials must comply with Regulation (EC) 1935/2004, as amended by Regulation (EU) 2019/1381, which requires that FCMs do not change the composition, smell or taste of food in an unacceptable way. The European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) oversees the risk assessments associated with the manufacture of FCMs. FCMs must also adhere to Good Manufacturing Practices (GMP) as outlined in Regulation (EC) 2023/2006.[60] These regulations ensure that materials such as plastics and ceramics used in food packaging are safe for consumers and comply with both EU and national legislation.

General labelling and packaging requirements

Food labelling is important for providing customers with essential information about products and allowing them to make informed choices about what to consume. In this area, the EU has some mandatory and general rules on food labelling that apply to any food or beverage distributed within EU territory.

The main legal source for food labelling in the EU is Regulation (EU) 1169/2011[61] on the provision of food information to consumers (FIC Regulation). This sets out the harmonised requirements for all food labelling information, such as the name of the food, ingredients list, allergen information, quantity of ingredients, date of marketing, expiry date, country of origin, quantity, storage conditions (if required), and the name and address of the food business operator or principal importer. Likewise, there are some specific rules for some food products. In the case of coffee, there are some specific labelling requirements, including the ICO's coffee identification

- 193/194 -

code, the label in English for green coffee, the country of origin, grade, net weight in kilograms, the inspection body's name, and the certification number for certified coffee.[62]

Official controls and enforcement

Regulation (EU) 2017/625, also known as the Official Control Regulation (OCR), outlines the mandatory controls that food safety authorities in EU Member States must carry out. It covers official certificates, health approvals and approved establishments involved in food distribution to ensure compliance with food safety standards. Moreover, Regulation (EU) 2019/1793[63] imposes strict conditions on food products from countries that repeatedly fail to meet safety requirements and regularly updates the list of non-compliant products and countries.

The European Commission also provides tools to help companies understand specific requirements for food products. For example, the Access2Markets website's "My Trade Assistant Goods",[64] a tool that allows users to search for information based on a product's name or Harmonised System (HS) code, country of origin, and country of destination. The HS code for coffee is 0901. In addition, the RASFF, established by the General Food Law Regulation, acts as a database to monitor food safety, including cases when coffee is rejected or approved for distribution in the EU.

In summary, exporting food products (such as coffee) to the EU requires a prior assessment exercise by the food business operators to identify all the general EU requirements on food safety and the specific conditions relevant to each product. In the case of coffee, once coffee exporters are aware of the general food regulations, they need to demonstrate compliance with the HACCP principles, MRLs, the maximum permitted levels of contaminants, and packaging conditions for the different types of coffee.

2. Pharmaceutical goods exports from the EU to Colombia

Pharmaceutical goods are among the most important goods in the EU-Colombia economic relationship. Along with aircraft and automotive machinery, pharmaceuticals

- 194/195 -

are the most valuable imported goods from the EU to Colombia. In 2022, Colombia's imports of pharmaceutical products from the EU amounted to EUR 1,128 million, representing 13.22% of total imports in that year.[65]

Annexe VI of the FTA covers sanitary and phytosanitary measures, and Appendix 3 provides general guidelines for the harmonisation of testing requirements and audits for animal and plant products that have an impact on health. These provisions ensure transparent cooperation and alignment of technical guidelines for high-quality pharmaceuticals and medical devices, thereby promoting international regulatory harmonisation.[66] Its Appendix I highlights the shared responsibilities of EU Member States and the European Commission for controlling production conditions, inspections and issuing health certificates. The European Commission coordinates inspections and implements legislation to ensure uniform application of standards across the EU and compliance with the requirements of importing parties.

In Colombia, the control and surveillance of imports, especially from the EU, are managed by the Colombian Agricultural Institute (ICA 'Instituto Colombiano Agropecuario') and the National Institute for Medicaments and Food Surveillance (INVIMA 'Instituto Nacional de Vigilancia de Medicamentos y Alimentos'). These institutions are responsible for verifying that imports meet Colombia's sanitary and phytosanitary standards, including inspections and certificates from EU Member States.[67] INVIMA specifically handles the authorisation and control of pharmaceutical product imports, ensuring compliance with health regulations.

INVIMA is a public institution under the Colombian Ministry of Health and Social Protection, which enforces health surveillance and quality control policies for medicines and biological products. It also engages in international cooperation, sharing best practices with regulatory authorities in Latin America and beyond. INVIMA maintains direct relations with health authorities in Spain, Denmark, and the Netherlands, fostering bilateral cooperation with the EU in areas related to public health and safety standards.[68]

a) Colombian legal framework

Colombia's main legal framework for import registration and licensing is outlined in Decree 925 of 2013, issued by the Ministry of Trade, Industry and Tourism. This decree updates previous licensing systems to streamline trade processes and align with Colombia's international trade commitments, such as the Free Trade Agreement

- 195/196 -

with the EU.[69] Article 12 of the Decree defines the import license as an administrative permit based on criteria established by the national government. Import registration is only mandatory for goods that require a permit, as specified in Article 24, with health checks or other compliance measures supervised by the competent authorities prior to authorisation (Article 25).[70]

The registration and sanitary approval of pharmaceuticals is primarily regulated by Law 9 of 1979, later amended by Decree 2106 of 2019. Article 88 of the Decree requires that all medicines, cosmetics and related products that affect public health, with the exception of those for agricultural use, must obtain a permit or sanitary notification from INVIMA.[71] In addition, Article 94 outlines the process for obtaining sanitary registrations for new medicines, which requires a comprehensive evaluation, including pharmacological, pharmaceutical and legal assessments, by INVIMA prior to the approval of applications for sanitary registrations. This framework ensures the safety and regulatory compliance of products entering the Colombian market.

Subsequently, Decree 1782 of 2014 outlines the procedures for the pharmacological and pharmaceutical evaluation of biological medicinal products during the health registration process in Colombia. Article 12 requires that laboratories producing biological medicinal products obtain Good Manufacturing Practices (GMP) certification, as defined by the Ministry of Health and based on the latest World Health Organization (WHO) reports.[72] The pharmacological evaluation is described as an assessment of the quality, safety and efficacy of a medicinal product, carried out by the Specialized Room of Medicines and Biological Products at INVIMA, Colombia's regulatory agency. The regulation was introduced in response to advances in GMP standards set by the WHO.

Then, Regulation 5402 of 2015 complements Decree 1782 of 2014 and provides a manual for verifying GMP compliance in the manufacture of biological medicines. The regulation is aligned with WHO guidelines and outlines procedures for the manufacture of biological medicinal products, taking into account the origin and production methods of these products. This GMP manual was notified to the World

- 196/197 -

Trade Organization (WTO) in 2014 under code G/TBT/N/COL/202, and no objections were raised.[73] The purpose of these regulations is to ensure that biological medicinal products manufactured in or imported into Colombia meet strict safety and quality standards.

Moreover, Notice 18 of 2020, issued by the Foreign Trade Directorate of the Ministry of Commerce, addresses the permits and authorisations required prior to applying for registration and import licenses, particularly for pharmaceutical products handled by INVIMA. Article 1.4 stipulates that products such as drugs, vaccines and medical instruments must be approved by INVIMA when applying for tariff exemptions.[74] Article 2.5 defines pre-import control measures, including sanitary registrations, marketing authorisations and other necessary approvals for the import of finished products and raw materials used in pharmaceuticals and medical devices, all within the scope of INVIMA.[75]

In addition to existing regulations, Decree 481 of 2004 from the Ministry of Social Protection provides more flexible rules for the production, import, and commercialisation of 'vital medicines not available' in Colombia. These medicines are essential for saving lives or alleviating patient suffering, but are unavailable or insufficient due to their low commercial profitability. The Specialized Chamber of Medicines of INVIMA's Review Commission is responsible for determining which medicines fall into this category, ensuring access to essential treatments despite market limitations.

In 2020, as a response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the Colombian government issued Decree 1148 of 2020, which established sanitary requirements to facilitate the production and importation of essential products and services. This decree addressed the global shortage of medical supplies by classifying COVID-19 treatments, such as vaccines, as "vital not available", allowing for their expedited import and distribution under the supervision of INVIMA. It also temporarily relaxed labelling, packaging and Good Manufacturing Practices (GMP) regulations to meet the urgent demand for Covid-19-related products.[76]

- 197/198 -

To further combat the pandemic, Decree 1787 of 2020 established the sanitary conditions for granting Emergency Use Sanitary Authorization (EUSA) for chemical synthesis and biological medicines used in the diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of COVID-19. This decree emphasised the need for rigorous regulatory processes to ensure the quality, safety, and efficacy of these highly specific medicines prior to their commercialisation.[77] Based on international standards, such as those set by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), Colombia adopted similar temporary authorisations to streamline the approval of COVID-19 treatments and ensure the rapid availability of crucial medical products during the pandemic.[78]

By mid-2022, although the COVID-19 situation had improved globally, in Colombia, the WHO had not yet declared the pandemic over. In response, the Colombian Ministry of Health and Social Protection issued Decree 1651 of 2022 on August 6, 2022, which approved the Emergency Technical Regulation for the Emergency Use Sanitary Authorization (EUSA) of chemical and biological medicines. This regulation, which is based on Decree 1787 of 2020, outlines the procedures for granting EUSA for new medicines or those with an existing sanitary registration seeking additional uses. The authorisation is valid for one year and renewable up to three times, with restrictions on medical or gift samples.[79]

In summary, all pharmacological products, whether manufactured in or imported into Colombia, require an authorisation from INVIMA for use or commercialisation, as well as sanitary registration. The specific procedures vary depending on the type and intended use of the drug. Colombia has been actively updating its regulatory framework to comply with international standards set by organisations such as the WHO, the WTO and the European Union's EMA. This ensures that Colombia's pharmaceutical regulations remain in line with global best practices.

- 198/199 -

VI. Conclusions

This document shows that the revision of the FTA has strengthened the economic relationship between the EU and Colombia. As one of the EU's New Generation FTAs, this agreement goes beyond traditional trade agreements by addressing tariff liberalisation, services, public procurement, and sustainable development. The EU's role as Colombia's third-largest trading partner and main source of foreign direct investment underscores the economic interdependence between the two regions. In addition to improving market access, the FTA has facilitated cooperation in areas such as development, diplomacy, and Colombia's post-conflict peace process. For example, the EU played a key role in Colombia's peace agreement with the FARC, supporting both the negotiation and implementation phases, including the creation of the European Peace Fund. This cooperation underscores the broad scope of the EU-Colombia relationship, combining economic growth with peacebuilding and sustainable development initiatives. Despite these positive aspects, Colombia has faced challenges in maintaining a consistent trade balance, reflecting the uneven benefits of the agreement across sectors.

Economically, the FTA has had mixed results. While it has contributed to Colombia's macroeconomic growth and opened markets, it has also exposed the country to fluctuations in global commodity prices, particularly in sectors such as coal, coffee and agricultural products. The EU's exports to Colombia have largely consisted of high-value goods such as pharmaceuticals, vehicles and machinery, contributing to a trade imbalance. In contrast, Colombia's exports, mostly agricultural and mineral products, are subject to global price volatility, which has affected their market performance. Between 2012 and 2017, the value of Colombia's exports to the EU decreased by 35%, while EU exports to Colombia increased by 8.6%, exacerbating the trade deficit. This imbalance highlights the structural economic challenges Colombia faces when competing with a more developed economic bloc such as the EU. Furthermore, while the FTA aimed to boost Colombia's GDP growth, the post-FTA period saw a slowdown in growth rates. This suggests that while the FTA has facilitated trade, the expected economic benefits have been uneven, especially when compared to the gains experienced by the EU.

Another distinctive feature of the EU-Colombia FTA is the inclusion of TSD provisions aimed at promoting human, labour and environmental rights. These provisions underscore the EU's commitment to integrating sustainable development into its trade policy, ensuring that economic growth does not come at the expense of social justice or environmental protection. However, the implementation of these TSD provisions has faced significant challenges in Colombia, largely due to the country's internal problems, including corruption, economic instability, and violence. While the FTA has supported the peace process and Colombia's alignment with international environmental

- 199/200 -

agreements, it has been less successful in improving labour rights, particularly in sectors such as mining and palm oil production. Reports of ongoing human rights violations, including violence against trade unionists and the failure to adequately consult with indigenous and Afro-descendant communities on land-use projects, point to the limitations of the FTA's provisions. Without enforceable sanctions or clear dispute resolution mechanisms, TSD chapters risk becoming symbolic rather than effective.

The text also shows that since the implementation of the FTA, both Colombia and the EU have adopted legal instruments, such as Colombia's Decree 1636 of 2013 and Law 1609 of 2013, to regulate trade and align policies with international commitments. These frameworks streamline trade processes, benefiting key sectors such as coffee and pharmaceuticals. Colombian coffee exports to the EU are thriving due to the FTA and Colombia's global position, while strict EU regulations ensure product quality. Similarly, pharmaceutical imports from the EU are governed by robust legal standards. However, ongoing regulatory adjustments are needed to realise the full potential of the FTA and maintain efficient trade.

Overall, the FTA has had a positive economic impact on the EU and Colombia, but its full benefits are limited by trade imbalances, slow progress on sustainable development, and the need for ongoing legal and regulatory updates. The agreement has facilitated market access and cooperation, but achieving its broader objectives, particularly in the areas of labour rights and environmental protection, will require sustained efforts and stronger enforcement mechanisms. As the FTA continues to evolve, it will be crucial for both parties to address these challenges to ensure that trade serves as a tool for inclusive and sustainable growth. ■

NOTES

[1] The European Union as a "political and economic union" is an individual member of the WTO; however, the EU Member States are also individual members of the WTO in their own right. https://www.wto.org/english/thewto_e/countries_e/european_communities_e.htm (last accessed: 31.12.2024.).

[2] European Commission, Report from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions on Implementation of the FTAs, (2018), https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/ES/TXT/?uri=celex%3A52019DC0455 (last accessed: 31.12.2024.).

[3] The classification of trade agreements made by the European Commission is based on the trade-based rules recognised by the WTO, https://www.wto.org/english/thewto_e/whatis_e/tif_e/utw_chap2_e.pdf (last accessed: 31.12.2024.).

[4] More information about the EU-CELAC relations can be found at https://www.eeas.europa.eu/node/13042_en (last accessed: 31.12.2024.).

[5] European Union External Action, EEAS. EU - Latin America & the Caribbean, https://www.eeas.europa.eu/eeas/eu-latin-america-caribbean_en#62678 (last accessed: 31.12.2024.).

[6] Information on the current status of EU trade agreements and negotiations can be found in https://policy.trade.ec.europa.eu/eu-trade-relationships-country-and-region/negotiations-and-agreements_en (last accessed: 31.12.2024.).

[7] Trade Agreement between the European Union and its Member States, of one part, and Colombia and Peru, of the other part. [2012] OJ L 354. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex%3A22012A1221%2801%29 (last accessed: 31.12.2024.).

[8] Council of the European Union, Council Decision (EU)2024/2751 of 14 October 2024 on the conclusion of the Trade Agreement between the European Union and its Member States, of the one part, and Colombia and Peru, of the other part, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=OJ:L_202402751 (last accessed: 31.12.2024.).

[9] European Parliament, Trade Agreement between the European Union and Colombia and Peru - European Implementation Assessment, (2018), https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2018/621834/EPRS_STU(2018)621834_EN.pdf (last accessed: 31.12.2024.) (Ex post evaluation 2018).

[10] European Commission, Directorate-General for Trade, Ex post evaluation of the implementation of the Trade Agreement between the EU and its Member States and Colombia, Peru and Ecuador: final report. Vol. I, Main report (Publications Office of the European Union, 2022), https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2781/9164 (last accessed: 31.12.2024.) (Ex post evaluation 2022).

[11] Andean Community. Official website: https://www.comunidadandina.org/quienes-somos/cronologia/ (last accessed: 31.12.2024.).

[12] The EU Member States are also individual members of the WTO, https://www.wto.org/english/thewto_e/countries_e/european_communities_e.htm#:~:text=The%20European%20Union%20%28until%2030%20November%202009%20known,union%20with%20a%20single%20trade%20policy%20and%20tariff (last accessed: 31.12.2024.).

[13] European Commission, EU trade relationship by country/region, "Overview of ongoing bilateral and regional negotiations", https://policy.trade.ec.europa.eu/eu-trade-relationships-country-and-region/negotiations-and-agreements_en (last accessed: 31.12.2024.).

[14] Ex post evaluation 2018, 9.

[15] Delegation of the European Union to Colombia, The European Union and Colombia, Bilateral, Regional and Multilateral relations between the EU and Colombia (EEAS, 2021), https://www.eeas.europa.eu/colombia/european-union-and-colombia_en?s=160#9210 (last accessed: 31.12.2024.) (EEAS 2021).

[16] World Trade Organization, Colombia and the WTO, https://www.wto.org/english/thewto_e/countries_e/colombia_e.htm (last accessed: 31.12.2024.).

[17] European Commission DG Trade, Assessing the Economic Impact of the Trade Agreement Between the European Union and Signatory Countries of the Andean Community (Colombia and Peru) (2012), https://circabc.europa.eu/ui/group/09242a36-a438-40fd-a7af-fe32e36cbd0e/library/dd23c915-e9a6-4aa6-a81c-a10561c966c8/details (last accessed: 31.12.2024.).

[18] These calculations were made with the application of computable general equilibrium (CGE) models.

[19] Ex post evaluation 2018, 35.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Ex post evaluation 2022, 31.

[22] Source: EU Commission. Directorate-General for Trade. Ex post evaluation published in 2022.

[23] Ministry of Commerce, Industry and Tourism, Report on the current trade agreements of Colombia 2022, https://www.tlc.gov.co/temas-de-interes/informe-sobre-el-desarrollo-avance-y-consolidacion (last accessed: 31.12.2024.) (Colombian FTAs report).

[24] Ministry of Commerce, Industry and Tourism, Agreements. European Union, https://www.tlc.gov.co/acuerdos/vigente/union-europea (last accessed: 31.12.2024.).

[25] Mas+ Colombia, FTA with the European Union: Colombia has exported less, (22 August 2021), https://mascolombia.com/colombia-ha-exportado-menos-a-partir-del-tlc-con-ue/ (last accessed: 31.12.2024.).

[26] Colombia: the peasants who want to defeat "free trade", BBC News, (2 September 2013), https://www.bbc.com/mundo/noticias/2013/09/130902_colombia_paro_agrario_ (last accessed: 31.12.2024.).

[27] European Commission, Trade Development and Sustainability. Sustainable development, https://policy.trade.ec.europa.eu/development-and-sustainability/sustainable-development_en (last accessed: 31.12.2024.).

[28] European Commission, Non-paper of the Commission services, Feedback and way forward on improving the implementation and enforcement of Trade and Sustainable Development chapters in EU Free Trade Agreements, https://trade.ec.europa.eu/doclib/docs/2018/february/tradoc_156618.pdf (last accessed: 31.12.2024.).

[29] Comparative Analysis of TSD Provisions for Identification of Best Practices to Support the TSD Review, London School of Economics and Political Science, (Feb 2022), https://www.lse.ac.uk/business/consulting/reports/comparative-analysis-of-tsd-provisions-for-identification-of-best-practices (last accessed: 31.12.2024.).

[30] European Commission, Communication from the commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions, COM(2022)409., https://circabc.europa.eu/ui/group/8a31feb6-d901-421f-a607-ebbdd7d59ca0/library/8c5821b3-2b18-43a1-b791-2df56b673900/details (last accessed: 31.12.2024.).

[31] Ex post evaluation 2018, 67.

[32] Ministry of Commerce, Industry and Tourism, Agreements. European Union. Subcommittee on TSD. Minute VIII. (November 2021), https://www.tlc.gov.co/acuerdos/vigente/union-europea (last accessed: 31.12.2024.).

[33] European Commission, Implementing Regulation (EU) 740/2013. On the derogations from the rules of origin laid down in Annex II to the Trade Agreement between the European Union and its Member States, of the one part, and Colombia and Peru, of the other part, that apply within quotas for certain products from Colombia, [2013] OJ L 204., https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=uriserv%3AOJ.L_.2013.204.01.0040.01.ENG&toc=OJ%3AL%3A2013%3A204%3ATOC (last accessed: 31.12.2024.).

[34] European Commission, Implementing Regulation (EU) 741/2013. Opening and providing for the administration of Union tariff quotas for agricultural products originating in Colombia, [2013] OJ L 204., https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=uriserv%3AOJ.L_.2013.204.01.0043.01.ENG&toc=OJ%3AL%3A2013%3A204%3ATOC (last accessed: 31.12.2024.).

[35] European Parliament and the Council, Regulation (EU) 19/2013, Implementing the bilateral safeguard clause and the stabilization mechanism for bananas of the Trade Agreement between the European Union and its Member States, of the one part, and Colombia and Peru, of the other part, [2013], https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32013R0019 (last accessed: 31.12.2024.).

[36] European Parliament and the Council, Regulation (EU) 2017/540. amending Regulation (EU) No 19/2013 implementing the bilateral safeguard clause and the stabilisation mechanism for bananas of the Trade Agreement between the European Union and its Member States, of the one part, and Colombia and Peru, of the other part, and amending Regulation (EU) No 20/2013 implementing the bilateral safeguard clause and the stabilisation mechanism for bananas of the Agreement establishing an Association between the European Union and its Member States, on the one hand, and Central America on the other, [2017], https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32017R0540&qid=1579189798344&from=EN (last accessed: 31.12.2024.).

[37] Ministry of Industry and Trade, Decree 1636 of 2013, By which market access commitments acquired by Colombia under the Trade Agreement between Colombia and Peru, of the one part, and the European Union and its Member States, of the other part, signed in the city of Brussels on June 26, 2012, are implemented [2013], https://www.tlc.gov.co/TLC/media/media-TLC/Documentos/Decreto-1636-del-31-de-julio-de-2013.pdf (last accessed: 31.12.2024.).

[38] Congress of Colombia. Law 1609 of 2013, By which general rules are dictated to which the Government must be subject to modify the tariffs, tariffs and other provisions concerning the Customs Regime, 2013, http://secretariasenado.gov.co/senado/basedoc/ley_1609_2013.html (last accessed: 31.12.2024.).

[39] Ministry of Finance and Public Credit, Decree 1165 of 2019, By which provisions are issued regarding the customs regime in development of Law 1609 of 2013, (2 July 2019), https://www.mincit.gov.co/getattachment/minindustria/temas-de-interes/zonas-francas/normatividad/2019/decreto-1165-de-2019/decreto-1165-del-2-de-julio-de-2019-compressed-1-comprimido.pdf.aspx (last accessed: 31.12.2024.).

[40] Ministry of Finance and Public Credit, Decree 360 of 2021, By which Decree 1165 of 2019 on the Customs Regime is modified and other provisions are issued, (7 April 2019), https://dapre.presidencia.gov.co/normativa/normativa/DECRETO%20360%20DEL%207%20DE%20ABRIL%20DE%202021.pdf (last accessed: 31.12.2024.).

[41] International Labour Organization, Sustainable supply chains to build forward better. Coffee production in Colombia for the European Market, (2020), https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_dialogue/---sector/documents/genericdocument/wcms_777245.pdf (last accessed: 31.12.2024.).

[42] Connect Americas, Rules for exporting coffee to the European Union, https://connectamericas.com/content/rules-exporting-coffee-european-union (last accessed: 31.12.2024.).

[43] World Intellectual Property Organization, Case Studies, Making the Origin Count: The Colombian Experience, https://www.wipo.int/ipadvantage/en/details.jsp?id=2617 (last accessed: 31.12.2024.).

[44] G. Ferro, United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. National Workshop on Fostering Integration of the Ethiopian Roasted Coffee Value Chain into Regional Value Chains (11 March 2021), https://unctad.org/system/files/information-document/THAN_ETH_Gustavo_Ferro_Colombia_110321.pdf (last accessed: 31.12.2024.).

[45] Ex post evaluation 2018, 40.

[46] EEAS 2021.

[47] European Commission, Strategy and Policy. Food Safety, https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/food-safety_en (last accessed: 31.12.2024.).

[48] European Parliament and the Council of the European Union, Regulation (EC) No 178/2002 of 28 January 2002 laying down the general principles and requirements of food law, establishing the European Food Safety Authority and laying down procedures in matters of food safety, [2012] OJ L 31, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/ALL/?uri=CELEX:32002R0178 (last accessed: 31.12.2024.).

[49] European Commission, RASFF Window, https://webgate.ec.europa.eu/rasff-window/screen/search?event=SearchForm (last accessed: 31.12.2024.).

[50] European Food Safety Authority, EFSA, https://www.efsa.europa.eu/en/about/about-efsa (last accessed: 31.12.2024.).

[51] European Parliament and the Council of the European Union, Regulation (EU) 2017/625. of 15 March 2017, on official controls and other official activities performed to ensure the application of food and feed law, rules on animal health and welfare, plant health and plant protection products, amending Regulations (EC) No 999/2001, (EC) No 396/2005, (EC) No 1069/2009, (EC) No 1107/2009, (EU) No 1151/2012, (EU) No 652/2014, (EU) 2016/429 and (EU) 2016/2031 of the European Parliament and of the Council, Council Regulations (EC) No 1/2005 and (EC) No 1099/2009 and Council Directives 98/58/EC, 1999/74/EC, 2007/43/EC, 2008/119/EC and 2008/120/EC, and repealing Regulations (EC) No 854/2004 and (EC) No 882/2004 of the European Parliament and of the Council, Council Directives 89/608/EEC, 89/662/EEC, 90/425/EEC, 91/496/EEC, 96/23/EC, 96/93/EC and 97/78/EC and Council Decision 92/438/EEC (Official Controls Regulation), [2017] OJ L 095, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A02017R0625-20220128 (last accessed: 31.12.2024.).

[52] European Commission, Health and Consumer Protection Directorate-General, Guidance Document, Key questions related to import requirements and the new rules on food hygiene and official food controls, 2014, https://food.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2016-10/biosafety_fh_legis_guidance_interpretation_imports.pdf (last accessed: 31.12.2024.).

[53] European Commission. Regulation (EC) 1881/2006 setting maximum levels for certain contaminants in foodstuffs, [2006] OJ L 364, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex:32006R1881 (last accessed: 31.12.2024.).

[54] European Commission, Regulation (EU) 2022/1370, Amending Regulation (EC) No 1881/2006 as regards maximum levels of ochratoxin A in certain foodstuffs, [2022] OJ L 206, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32022R1370 (last accessed: 31.12.2024.).

[55] CBI Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

[56] Commission Regulation (EU) 2017/2158, Establishing mitigation measures and benchmark levels for the reduction of the presence of acrylamide in food (Text with EEA relevance), [2017], https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex:32017R2158 (last accessed: 31.12.2024.).

[57] European Parliament and the Council, Regulation (EC) 396/2005, on maximum residue levels of pesticides in or on food and feed of plant and animal origin and amending Council Directive 91/414/EEC, [2005], https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A02005R0396-20220516 (last accessed: 31.12.2024.).

[58] European Commission, Food Safety, EU Pesticides Database, https://food.ec.europa.eu/plants/pesticides/eu-pesticides-database_en (last accessed: 31.12.2024.).

[59] Commission Regulation (EU) 2023/334, Amending Annexes II and V to Regulation (EC) No 396/2005 of the European Parliament and of the Council as regards maximum residue levels for clothianidin and thiamethoxam in or on certain products. [2023] OJ L 47, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2023/334/oj (last accessed: 31.12.2024.).

[60] European Commission, Regulation (EC) 2023/2006, On good manufacturing practice for materials and articles intended to come into contact with food. [2006]. OJ L 384, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32006R2023 (last accessed: 31.12.2024.).

[61] European Parliament and the Council, Regulation (EU) 1169/2011, On the provision of food information to consumers, amending Regulations (EC) No 1924/2006 and (EC) No 1925/2006 of the European Parliament and of the Council, and repealing Commission Directive 87/250/EEC, Council Directive 90/496/EEC, Commission Directive 1999/10/EC, Directive 2000/13/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council, Commission Directives 2002/67/EC and 2008/5/EC and Commission Regulation (EC) No 608/2004. [2011] OJ L 304, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/ALL/?uri=CELEX%3A32011R1169 (last accessed: 31.12.2024.).

[62] CBI Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

[63] European Commission, Implementing Regulation (EU) 2019/1793 of 22 October 2019 on the temporary increase of official controls and emergency measures governing the entry into the Union of certain goods from certain third countries implementing Regulations (EU) 2017/625 and (EC) No 178/2002 of the European Parliament and of the Council and repealing Commission Regulations (EC) No 669/2009, (EU) No 884/2014, (EU) 2015/175, (EU) 2017/186 and (EU) 2018/1660. [2019], https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A02019R1793-20220703 (last accessed: 31.12.2024.).

[64] European Commission. DG Trade, Access2Markets, My Trade Assistant Goods + ROSA, https://trade.ec.europa.eu/access-to-markets/en/results?product=090121&origin=CO&destination=HU (last accessed: 31.12.2024.).

[65] EEAS 2021.

[66] FTA, 2188.

[67] FTA, 2188.

[68] Instituto Nacional de Vigilancia de Medicamentos y Alimentos - INVIMA. Cooperación Internacional. https://invima.gov.co/es/web/guest/cooperacion-internacional (last accessed: 31.12.2024.).

[69] Ministry of Commerce, Industry and Tourism, Decree 925 of 2013. Official Journal No. 48.785 of May 9, 2013, https://www.cancilleria.gov.co/sites/default/files/Normograma/docs/decreto_0925_2013.htm#25 (last accessed: 31.12.2024.).

[70] Ibid.

[71] Administrative Department of the Civil Service. Decree 2106 of 2019, by which rules are issued to simplify, suppress and reform unnecessary procedures, processes and procedures existing in the public administration. Official Journal No. 51.145 of November 22, 2019. https://www.cancilleria.gov.co/sites/default/files/Normograma/docs/decreto_2106_2019.htm#87 (last accessed: 31.12.2024.).

[72] Administrative Department of the Civil Service. Decree 1782 of 2014, which establishes the requirements and procedure for the Pharmacological and Pharmaceutical Evaluations of biological medicines in the process of sanitary registration. September 18, 2014. https://tinyurl.com/5f5bpkt9 (last accessed: 31.12.2024.).

[73] Ministry of Health and Social Protection, Regulation 5402 of 2015, By which the manual and the instrument of verification of Good Manufacturing Practices of Biological Medicines is issued. December 17, 2015. Preamble, https://studylib.es/doc/7707423/resoluci%C3%B3n-5402-de-2015---ministerio-de-salud-y-protecci%C3%B3... (last accessed: 31.12.2024.).

[74] Ministry of Commerce, Industry and Tourism - Directorate of Foreign Trade. Notice 18 of 2020. Official Journal 51,427 of 04 September 2020. Article 1.4, https://www.cancilleria.gov.co/sites/default/files/Normograma/docs/circular_mincomercioit_0018_2020.htm (last accessed: 31.12.2024.).

[75] Ibid. Article 2.5 numeral 1 and 2.

[76] Presidency of the Republic of Colombia, Decree 1148 of 2020, which establishes the sanitary requirements that facilitate the manufacture and import of products and services to address the COVID 19 pandemic and dictates other provisions. August 18, 2020, https://www.funcionpublica.gov.co/eva/gestornormativo/norma.php?i=138950 (last accessed: 31.12.2024.).

[77] Presidency of the Republic of Colombia, Decree 1787 de 2020, which establishes the sanitary conditions for the processing and granting of the Emergency Use Sanitary Authorization - EUSA for chemical synthesis and biological medicines for the diagnosis, prevention and treatment of Covid-19. December 29, 2020. Preamble, https://www.funcionpublica.gov.co/eva/gestornormativo/norma.php?i=154146 (last accessed: 31.12.2024.).

[78] Ibid.

[79] Ministry of Health and Social Protection, Decree 1651 of 2022, By which the emergency technical regulation is issued for the processing of Sanitary Authorization of Emergency Use - ASUE of chemical and biological synthesis drugs and other provisions are issued. August 6, 2022, https://www.cerlatam.com/normatividad/minsalud-decreto-1651-de-2022/ (last accessed: 31.12.2024.).

Lábjegyzetek:

[1] The Author is lawyer; LL.B. (ICESI University, Cali, Colombia), LL.M. (ELTE, Budapest, Hungary).