János Tamás Czigle[1]: Religious Holidays at the Workplace in the European Union - Issues, Questions and a Note on the Achatzi-case[1] (IAS, 2023/1., 79-108. o.)

Absztrakt

A pluralizmus az Európai Unió egyik legalapvetőbb értéke és legkülönlegesebb jellemzője, melyen belül a vallási pluralizmus egyre fontosabb tényezővé vált az elmúlt évtizedekben. Ugyan a vallási elhivatottság szintje sokat változott az Unóban, egyértelmű, hogy a keresztény hagyományok és gyökerek még mindig mélyen áthatják az egyes Tagállamok munkajogát, kiváltképpen a vallási ünnepek és a heti pihenőnapok tekintetében. Az Európai Unió Bírósága (a továbbiakban: 'EUB') számos munkahelyi vallásszabadsággal kapcsolatos ügyben hozott ítéletet az elmúlt években, kitérve a vallási ünnepekre is. E tanulmány célja, hogy felvázolja a munkahelyi vallásszabadság vallási ünnepekkel és heti pihenőnapokkal kapcsolatos vonatkozásait szabályozó uniós jogszabályi környezetet, egyúttal reflektálva néhány Tagállam sajátos nemzeti, vallási hagyományaira, változó demográfiai-társadalmi kontextusaira. Ennek részeként az EUB Achatzi-ügyben hozott határozata is ismertetésre és elemzésre kerül.

Kulcsszavak: vallásszabadság, vallási ünnepek és heti pihenőnapok a munkahelyen, európai jog, Európai Unió Bírósága, Achatzi-ügy

Abstract

Pluralism is an intrinsic feature and a core value of the European Union. Within pluralism, religious pluralism is becoming an increasingly important factor. Though the level of religious observance has changed significantly in the past decades, it seems evident, that certain Christian religious traditions still dominate most labor codes of EU Member States with respect to holidays and the weekly rest days. The Court of Justice of the European Union (hereinafter referred as 'CJEU') has issued a number of judgements in the past few years related to religious freedom at the workplace, including a guidance on religious holidays. This article aims to outline the European Law regulating the religious holiday related aspects of religious freedom at the workplace, while reflecting on some EU Member State's traditions and the changing societal-demographical context. As part of this analysis the CJEU's decision in the Achatzi-case is also introduced.

Keywords: religious freedom, religious holidays and weekly rest days at the workplace, European Law, Court of Justise of the European Union, Achatzi-case

1. The contemporary concept of religious holidays

Religion plays a crucial role in the lives of most individuals throughout the world. Religious freedom has dual value, both as a prohibition of discrimination based on religion and as a right to fulfil an obligation of one's faith. At the workplace employees are directly affected by the means through which employers protect or restrict their religious beliefs.[2] The growing religious diversity in the European Union (hereinafter referred as 'EU') - a result of migration, changing societal norms and the emergence of new religious movements - has given rise to requests to accommodate religiously motivated demands at both public and private workplaces.[3]

Religious holidays are one of the most distinctive elements of religions conducive to deepening, strengthening, and reaffirming religious identity, referring to values and principles, encouraging self-reflection and spiritual transformation.[4] All religious holidays have certain characteristics that make them a distinctive part of culture in

- 79/80 -

a historical and geographical perspective.[5] The observation of religious holidays, participation in the specific religious ceremonies form a decisive aspect of religious freedom, from religion's internal and external frame of reference ('forum internum' and 'forum externum' respectively). When studying religions from a more theological perspective, we can see that monotheistic religions typically have traditions which commemorate the origins and the history of the relationship between the divine and man, entail various cultural customs, habits or recollect notable events written down in sacred books. In Christianism, the main celebrations are Christmas, the Epiphany, Easter, Corpus Christi, All Saints' Day and All Souls' Day. In Judaism, these are the Jewish New Year (Rosh Hashanah), Day of Atonement, (Yom Kippur), Feast of Tabernacles (Sukkot), Festival of Lights (Hanukkah) and the Feast of Lots (Purim). In Islam these are the holy month of fasting (Ramadan) and the Festival of Breaking the Fast (Eid al-Fitr), Feast of the Sacrifice (Eid al-Adha) and the Night of Power (Laylat al-Qadr).[6]

While religions follow distinctive patterns of religious manifestation, the rules of certain holidays tend to exclude or restrict the ability to work and specify countless additional requirements.[7] These rules may naturally lead to conflicts at the workplace, in schools (for example when students are expected to participate in school festivals celebrating certain religious holidays on a mandatory basis) or in the courtroom where a person may wish to reschedule a trial or testimony for religious reasons.[8]

The persistent and still ongoing Covid-19 pandemic has also left its mark on the way people celebrate religious holidays, which is just a fragment of its tremendous impact on lives and livelihoods of people all over the world.[9] The expression of faith may

- 80/81 -

emphasize the necessity of close contact by holding hands and sharing communion in Christian churches or standing shoulder-to-shoulder during prayers in mosques, touching or kissing religious objects at synagogues and so on. At the beginning of the pandemic, the Pope has established directions on how Christian holidays should be celebrated in line with government guidelines, while Bishops worldwide have suspended Sunday obligations. Similar steps were taken in case of other religions.[10]

This article aims to outline the European law regulating the religious holiday-related aspects of religious freedom at the workplace, while also reflecting on some EU Member State's traditions and the changing societal-demographical context of religion itself. As a part of this, the decision of the Court of Justice of the European Union's (hereinafter referred as 'CJEU') in the Achatzi-case[11] will also be introduced and analyzed. This case is especially interesting, since it follows a series of religious freedom-related cases at the workplace, which have garnered both public and professional interest, due to their overarching implications and sometimes polarizing nature.

2. The religious holidays in the European Union - United in Diversity?

2.1. Religious Holidays - Historical Roots and EU law

Theodor Heuss, the President of the Federal Republic of Germany declared in 1956 that Europe was built in three hills: the Acropolis, the Capitol and the Golgotha, representing the Greek cultural heritage, the Roman legal system and Christianity, the moral and social compass respectively.[12] This heritage - Christianism in particular - however has region and country- specific nuances and intonations. As Pope John Paul II eloquently put it: "The spread of faith on the continent contributed to the formation of individual European nations, planting in them cultural seeds of various features, but connected through a common heritage of values rooted in the Gospel."

Religious freedom is central to the landmark documents in the history of human rights such as the European Convention of Human Rights (hereinafter referred as 'ECHR') or the Charter of the Fundamental Rights of the European Union (hereinafter referred as: Charter).[13] Similarly to diversity, which is an intrinsic feature of European

- 81/82 -

integration, another core value of the EU is pluralism, within which religious pluralism plays a mayor role.[14]

Interestingly, religion and religious freedom was not in the primary focus throughout the earlier history of the European integration up until the 1990's, but this clearly changed in the last decade, as it is once again in the forefront of public discourse.[15] The initial reluctance to focus on religious freedom derives from the earlier concept of integration, which focused on economic rather than human right considerations.[16] Religious freedom at the workplace has become an increasingly pressing question in the last few years with a growing number of cases being referred to the CJEU for preliminary rulings. These decisions are of paramount importance since they are binding for all the EU Member States and create immediately enforceable rights at a national level.[17]

EU Member States have a long tradition of celebrating certain religious holidays: recognizing them as public holidays is a widespread practice. At the same they have diverse approaches to the role of religion(s) in society, how it should be organized and protected on a national level with countless national traditions. These traditions are clearly encapsulated in a variety of legal regulations on religion.[18]

The level of religious observance and the so-called 'religious landscape' have changed significantly over the past decades, especially in Western-Europe. An Eurobarmeter survey of 2010 measured how often Europeans attend religious services besides weddings or funerals. Data shows that nearly 30% of Europeans never attend religious ceremonies, while 17% do so on a weekly or a more frequent basis. A substantial portion of EU citizens attend the ceremonies only on holidays or other special occasions.[19] A similar study in the United States showed that religion plays an important part of life for 56% of the respondents, 39% reported that they attend a religious service once a week, and 58% claimed that they pray at least once a week. In contrast to the Europeans whose level of religiosity has decreased in the last years, religiosity in the USA remains largely the same.[20]

Certain Christian religious traditions undoubtedly dominate the labor codes of European countries. Churches and religious organizations are key actors in the labour

- 82/83 -

market as well. At the same time, a growing number of citizens do not share Christian religious views,[21] while other religions are gaining in popularity, owing to societal and demographic factors.[22] Realizing the changing perception of religion at the workplace -and generally - expert commissions were established in quite a few countries with the purpose of compiling reports to ascertain the different needs and customs of employees, and to outline minority practices. These initiatives include the Commission on the Future of Multi-Ethnic Britain,[23] established by the Runnymede Trust in 1998 which aimed at considering the political and cultural implications of the changing diversity of the British people, the Stasi Commission in France, the Bouchard-Taylor Commission in Quebec and the Foblets-Kulakowski Commission in Belgium.[24]

Some municipal governments, schools and workplaces have already started to facilitate events to celebrate minority festivities in addition to Christmas and Easter, for example in the United Kingdom, where the Mayor of London held a Diwali celebration.[25] Preferential regimes for certain confessions have been also introduced in several EU Member States by way of thematic agreements. An example for this can be found in Italy where members of the Italian Hindu Union are allowed to observe Divapali celebrations based on a framework of flexible working arrangements.[26]

In the EU even agnostics and atheists accept the rhythm of a mostly secular life - from weekly work schedules to holiday traditions - which still reflect the original Christian roots.[27] There are many, who do not belong to any church but consider themselves to be Christian from the perspective of cultural identity, treasuring Christian customs and holidays,[28] these are people who 'belong without faith'.[29] In the highly secular Belgium for example six out of ten public holidays originate in a religious holiday which are

- 83/84 -

deeply embedded in the national culture,[30] notwithstanding a certain level of disconnect from their origins.[31] See the below table on public holidays and their origins in Western Europe[32] which clearly demonstrates how entrenched religious holidays are[33]:

| Country | Total number of public holidays | State/nation building | Universal | Religion related | % of religion related holidays |

| Austria | 15 | 1 | 2 | 12 | 80.0 |

| Belgium | 12 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 75.0 |

| Cyprus | 17 | 4 | 2 | 11 | 64.7 |

| Denmark | 13 | 1 | 1 | 11 | 84.6 |

| Finland | 12 | 1 | 2 | 10 | 76.9 |

| France | 12 | 2 | 3 | 7 | 58.3 |

| Germany | 12 | 2 | 2 | 8 | 66.7 |

| Greece | 14 | 2 | 2 | 10 | 71.4 |

| Ireland | 9 | 1 | 5 | 3 | 33.3 |

| Italy | 12 | 2 | 2 | 8 | 66.7 |

| Luxembourg | 13 | 1 | 2 | 10 | 76.9 |

| The Netherlands | 9 | 2 | 1 | 6 | 66.7 |

| Norway | 13 | 1 | 2 | 9 | 69.2 |

| Portugal | 10 | 2 | 2 | 6 | 60,0 |

| Spain | 14 | 2 | 2 | 10 | 71.4 |

| Sweden | 13 | 1 | 2 | 10 | 76.9 |

| Switzerland | 14 | 4 | 1 | 9 | 64.3 |

| United Kingdom | 8 | 0 | 4 | 4 | 50.0 |

The custom of Sunday rest is also universally accepted in the Christian world[34] and is seen as a definitive guarantee of religious freedom. It may have lost its original religious content,[35] but its secular purpose - i.e. to provide a regular period of rest for workers - is more important than ever.[36] Observing days of rest may pose no difficulty

- 84/85 -

for the majority of nationals in the EU,[37] but workers of certain minority faiths could find themselves overlooked and may end up requesting an alternative work schedule or adjustment. In other words, for religious minorities such as Jews, Muslims[38] or Seventh Day Adventists in Europe, it is clear that the Sunday trading laws and public holiday schedules were not designed with them in mind.[39] A similar trend may be observed in case of the so-called - and more and more widespread - 'neutral' or 'professional' dress codes required by the private workplaces. Most employees have little to no trouble complying, but it goes without saying that these dress codes conflict with some of the religious modesty standards stipulated by certain faiths.[40]

The permanent presence of Islam and Muslims - being the fastest growing religion as well as ethnic minority - was a rather new phenomenon until a couple decades ago in most EU Member states. This first generation immigrants were largely inhabitants of the Muslim world, who migrated to Western Europe for economic or political reasons after World War II and the oil crises of the 1970s. Their descendants, i.e. second, and third generation immigrants - along with the huge influx of refugees and migrants arriving in Europe in the 2010s - may feel more inclined to express their religious views as part of their identity and observe religious holidays. This includes wearing a religious garment, following religious dietary laws and burial practices as well as other core-values, which may prompt private and public employers to consider some level of accommodation to their religious needs. This accommodation and the integration of minorities certainly proves to be a daunting task for EU Member States while their

- 85/86 -

traditional relationship between state and religion is being reassessed.[41] As a gesture towards fostering good relations between religions and different beliefs a wide range of religious festivities are recognized and celebrated in the public and sometimes in the private sector too.[42] In the latter case, the mainstream approach has been letting the employer decide on flexible work arrangements, since states may be of the view that companies are better equipped to manage issues related to work scheduling.

The EU as a general rule respects national legislations on religious associations, communities and churches as enshrined in Article 17 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (hereinafter referred as: TFEU).[43] The Charter is a legally binding quasi-constitution of the EU, that also reiterates the significance of religious freedom[44] while declaring the generic principle of non-discrimination.[45]

Focusing on equality at the workplace, the Employment Framework Directive[46] (hereinafter referred as: Directive) further enshrines the value of religious freedom, but also reflects on its possible limitations. The Directive provides a general framework against discrimination on the grounds of religion or belief in employment, prohibiting direct and indirect discrimination, as well as harassment, victimization, and instructions to discriminate based on religion and belief. Direct discrimination occurs when a person is treated less favourably than another in a comparable situation due to his religion or belief. Indirect discrimination on the other hand occurs when a seemingly

- 86/87 -

neutral provision, criterion or practice has the effect of typically putting persons of a particular religion or belief, disability, age, or sexual orientation at a disadvantage compared with other persons. Such a discrimination may however be justified by a legitimate aim in case the means of achieving this aim are appropriate and necessary.

The Directive highlights certain cases, where discriminatory requirements could potentially be justified, for example in order to ensure public security and to maintain public order or prevent criminal offences, the protection of health and the protection of the rights and freedom of others.[47] The Directive also elaborates on the so-called 'genuine occupational requirements' whereby a religious characteristic may justify certain discriminatory measures as long as the objective is legitimate and the requirement proportionate.[48] Furthermore, in case of employers such as churches or organizations with religious ethos, the employer may also expect a certain degree of loyalty from the employee towards this ethos.[49]

Focusing on the status of Sunday, the first Working Directive[50] was challenged in before the CJEU in the 1990's. In its ruling the CJEU annulled an Article of the former directive that designated Sunday as the default day of rest, but it did so on a technical basis, as the Council has failed to explain why Sunday as a weekly day of rest is more closely connected with the health and safety of employees than other days of the week. Nevertheless, the CJEU did consider the diversity of cultural, ethnic and religious factors which need to be taken into account when assessing which day should be designated as day of rest.[51] Currently, EU law prescribes that Member States must ensure that all workers have at least 24 hours of rest every week but it remains silent[52] on which day this should be, preferring to leave this sensitive matter to the Member States.[53]

- 87/88 -

Due to historical and traditional reasons national laws may prescribe a more favorable treatment for members of religious minority, which, as a form of positive discrimination aim to level the playing field for those adhering these minority religions. The Directive entrenches the above as a concept of positive action, which aims to ensure true equality through the means of promoting the rights of groups facing a certain disadvantage.[54]

Unlike the European Court of Human Rights (hereinafter referred as: ECtHR)[55] the CJEU does not have overarching jurisprudence regarding religious holiday-related issues at the workplace. Hence the case law of the ECtHR is a valid point of reference for adjudicating this right.[56] This is all the more true in the recent years, where the CJEU has largely echoed or even explicitly followed the ECtHR's religious freedom-related guidance. Unlike the ECtHR however, the decisions of the CJEU do not depend on voluntary compliance by a Member State, they are legally binding.

One of the limited examples of CJEU case law focusing on the delicate matter of religious holidays would be the Vivien Prais-case,[57] where a Ms. Prais presented her candidacy to an open competition organized by the Council of the European Communities. She requested that the date of the event be changed as it coincided with the first day of a Jewish holiday which prohibits travelling or writing.[58] When her request was rejected she filed a suit before the ECJ against the European Council,[59] claiming that the decisions violated the clause in the Staff Regulations according to which candidates are chosen without distinction of race, religion or sex. In this early case the Court clearly declared that religious discrimination is prohibited in European law as it plainly violates the fundamental rights of individuals. At the same time, her claim was rejected reiterating that the written test must be identical and take place under the same conditions for all candidates,[60] notwithstanding the fact that the appointing authority should inform itself of the dates which might not be suitable for religious reasons. Nevertheless, in the present case the authority should only set other dates for the tests

- 88/89 -

in case it had been notified before the other candidates were invited.[61] This is an early emergence of the concept of reasonable accommodation of religion in European law, even before the Employment Equality Directive was adopted. With all its implications, the case may be regarded as an important milestone in the development of European human rights jurisprudence.[62]

In the United States[63] and Canada,[64] the concept of reasonable accommodation[65] - i.e. an approach based on the fundamental observation, that some individuals are prevented from performing a task or from accessing certain spaces in conventional ways due to a characteristic they have, for example disability or religion[66] - is historically and societally entrenched. This approach primarily originates from the religious tolerance, but later expanded to also cover the grounds of disability.[67] In the European Union, it was the other way around, as the concept is explicitly identified only on the grounds of disability in Article 5 of the Framework Directive,[68] but there are some signs that Member States[69] endorse applying the approach for religious freedom-related matters

- 89/90 -

at the workplace as well. Several European countries (including Bulgaria for example) have included a specific duty to provide reasonable accommodation for religion regarding working hours and time off for religious festivities. This is hardly surprising, since most complaints concerning a failure to accommodate religious diversity at the workplace originated from the failing to respect working hours to attend religious services or respect religious holidays, which are claimed to accommodate only majority religions.[70]

2.2. Religious holidays and rest days in the EU Member States and beyond - a few examples

2.2.1. France, Belgium and the Netherlands

In France, the Labour Code encapsulates the notion, that an employer may treat any request for holiday or vacation equally, regardless of whether they are motivated by religion or other considerations. In the public sector we can see efforts and gestures made towards religions other than the Christian faith. A ministerial circular in 1967 for example established that managers may authorize absences for civil servants and public agents who so request, to participate in religious ceremonies, provided that these absences are compatible with the regular operation of the service. Since 1967 an annual list of legal holidays in the public sector is published, which coincides with the official legal calendar of holidays in the private sector. In 2003 a Commission (Commission de réflexion sur l'application du principe de laïcité dans la République) was created, which focused on the nature and application of the principle of laïcité. The report of this Commission proposed that religious holidays such as Yom Kippur or l'Aïd el-Kebir should be public holidays in French schools, but that wearing highly visible religious clothing and symbols (large cross, veil, kippa etc.) should be prohibited in the school system. A heavily polarized public debate erupted when Law of 2004-228 of 15 March 2004 was adopted, which prohibited all symbols and clothing that revealed the religious affiliation of the students.[71]

A new circular was issued in 2012[72] rendering the calendar permanent while also renewing it, with a view to include holidays other than Catholic and Protestant ones, for instance Orthodox holidays (Teophany), Armenian (24 April), Muslim (Aïd El Adha, Al Mawlid Ennabi, Aïd El Fitr), Jewish (Chavaout, Roch Hachana, Yom Kippour) and Buddhist (Vesak) holidays. This is a non-exhaustive list, meaning that the heads of the services may grant requests for leave of absence potentially accommodating holidays not captured by the regulation.[73]

- 90/91 -

Getting time off for religious holidays in the private sector is dependent on negotiations with the employer, who is not obliged to grant them if a service would be hindered by the absence of employees. There are examples of businesses that rearrange work schedules during Ramadan by reducing the lunch break or by granting leaves of absence and encouraging employees to take these days off.[74]

As outlined in the first section of this study, most of the public holidays in Belgium have religious origins, which seems like somewhat of a contradiction in a highly secular country that at the same time has one of the most dynamically growing Muslim minority in Europe. Back in 2003, a decree of the Flemish government allowed nursery and elementary school students to take a day off to celebrate their religion or belief recognized by the Constitution.[75] In 2008, the Muslim Festival of Sacrifice coincided with school exam period. Schools found different solutions: some accepted to postpone the exams, others asked pupils to justify their absence for family reasons etc.[76]

In the Netherlands the Islamic holiday's status was set down in the ruling of the Supreme Court (30 May 1984), pronounced in the case of a Turkish housekeeper lodging a complaint against her employer. She had requested a day off to be able to participate in the festivities celebrating the end of Ramadan, which was refused by her employer. Since she did not work that day, she was dismissed with immediate effect.[77]

2.2.2. Spain

In certain cases, there are region- or even city-specific legal calendars. In the Spanish cities of Ceuta and Melilla, enclaves in Northern Africa (where approximately 50% of the population identifies as Muslim) Muslim celebrations were included in the regional holidays for 2018 (Idu Al Adha, 22 August).[78] Spain has also enacted rules to accommodate the religious holiday-related requests of the Jewish and Seventh Day Adventist community.[79] Regulations include Law 25/1992 (Cooperation Agreement with the Federation of Israelite Communities of Spain) and Law 26/1992 (State Cooperation Agreement with the Islamic Commission of Spain).

- 91/92 -

Weekly rest days for Seventh Day Adventists and Jewish communities could be granted instead of the 'general' days of rest based on the agreement between the employer and employee. Members of the Islamic communities belonging to the Islamic Commission may also request permission to stop working on Fridays between 13:3016:30 and one hour before sundown during Ramadan. This is also subject to agreement with the employer and the hours not worked must be made up for.[80]

2.2.3. Germany

Sunday as a weekly day of rest has a tradition of constitutional protection in Germany, dating back to Article 139 of the Weimar Constitution. This declared that Sunday and the recognized holidays would remain days of rest and moral exaltation (seelische Erhebung). There are different Holiday Acts of the Federal States, almost all of which recognize Christian Holidays.

In the sphere of employment, there is no general duty for the employer to accommodate the religious beliefs of his workers and to individually determine the day of rest for them. There is no uniform approach to religious holidays that are not legally recognized, as most state-level rules only privilege workers who belong to a recognized religious community. The Holiday Act of North Rhine-Westphalia[81] and Bavaria for example extends the right to attend worship during working hours to encompass certain Jewish holidays.[82]

Employers need to consider the fundamental rights of their workers, including their religious freedom within the 'measures of reasonability'. A labour court in SchleswigHolstein has recognized this principle and held that a worker belonging to the Seventh-day Adventist Church[83] is entitled to refuse taking up work on Sunday for religious reasons, unless the employer can invoke operational requirements which would indicate otherwise, but religious accommodation must be determined on a case-by-case basis.[84]

A recent controversy over whether Muslim holidays should be recognized in the country sparked considerable debates, which have intensified significantly over the last few years. Between 2010-2016 the number of Muslims in Germany[85] rose from 3.3 to 5 million, partly due to the influx of almost 1 million Muslim refugees to the country. The question of Islamic holidays is part of a much wider discussion on religious freedom

- 92/93 -

for Muslims in the country, including burial sites, building mosques etc.[86] As professor Riem Spielhaus put it quite aptly:

"When society really becomes plural in terms of religion, then religious freedom becomes a challenge."[87]

2.2.4. Denmark

We can see interesting patterns in Denmark, where a major area of conflict between individual religious convictions and the standardized Danish secular labour market, both in public and private spheres. Concerns and questions of accommodation to religious festivities were raised regarding the public holiday calendar. The latter had been established by royal decree at the times of absolutism, consistent with the Protestant Christian holidays, but with certain Danish peculiarities.

Public institutions are closed on Christmas, Easter and Pentecost, and also on the following Mondays. Public peace must be kept on some of the central holidays by avoiding disturbances such as loud music, sports etc.[88] The holidays are mutually expected to be recognized in common agreements in the labour market, therefore, in principle these are days of rest for employees, and those who still have to work on these days are compensated. Christians cannot rely on religious custom for going to Sunday service to avoid working, and religious practices are not considered a legitimate argument for extra days or one particular day off. The same approach is taken for minority religions.[89] Any potential accommodation is highly dependent on a compromise between the employer and the employees in both the public and private spheres.

2.2.5. Examples from the Balkans

In Bulgaria, according to the Protection Against Discrimination Act, Article 13 (2) employers have a duty to provide reasonable accommodation for religion in terms of working hours and rest days where this would not lead to excessive difficulties and where it is possible to compensate for the possible adverse consequences on the business. In addition, according to Article 173 of the Bulgarian Labour code employees adhering to a religion other than the Eastern Orthodox Christianity have the right to

- 93/94 -

use their annual leave when they celebrate religious holidays or may take unpaid leave, but not more than the number of days of the Eastern Orthodox Christian holidays.[90]

Limited accommodation is set forth under Article 134 (1) letter F of the Labour Code of Romania in relation to the observance of religious celebrations by employees by granting 2 leave days for 2 religious celebrations on an annual basis, in line with the employee's faith, provided that said religion is a state-recognized religion.

While Catholic religious holidays are national holidays in Croatia, members of the biggest religious minorities (Orthodox Christians, Jews and Muslims) can take a day off on the day of their main religious festivities. Limited accommodation is also mentioned in the Laws on Holidays of the Republic of North Macedonia.[91]

2.2.6. United Kingdom

British Muslims have made numerous claims in the recent years referring to the freedom of religion and non-discrimination when requesting to attend the Friday Prayers at mosques[92] and leave of absence from work to celebrate Eid or to go on Hajj.[93] Most often it comes down to a unique compromise between employers and employees.[94] In the J.H. Walker v. Hussain-case,[95] a holiday arrangement for factory workers was in effect, which prevented Muslim employees from taking a leave of absence to celebrate important religious festivities. The local Industrial Tribunal established, that although the restrictions on taking a leave of absence applied to all workers, it disproportionately affected Muslims. Nevertheless, according to the guidance the discrimination was not based on religion, but rather on ethnic background, since the employees affected were predominantly of Asian origin.

In the Esson v. London Transport-case[96] a bus conductor became a Seventh Day Adventist and was thus precluded from working on Saturdays, absenting himself on several occasions resulting in his dismissal. He claimed that this treatment was unfair, but an industrial tribunal found otherwise: he clearly breached his employment

- 94/95 -

contract, and it was unreasonable to expect the employer to tolerate the disruption caused by his absences.[97]

The Sunday Trading Act of 1994 permits shops to open on Sundays in the United Kingdom under certain conditions, protecting shop workers who may opt out from working on this day, who may not be penalized for doing so.[98]

2.2.7. Hungary

Some controversies centred around the short-lived ban on Sunday trading for stores in Hungary. The ban (Act CII of 2014, enacted on the 15[th] of March 2015 and repealed in April 2016) aimed at protecting worker's physical and mental health by providing adequate rest time and striving for a balance between the freedom of practicing commercial activity and the interest of employees who work on Sundays. A few exceptions (markets, airport shops and petrol stations) were made, but the majority of shops were closed on Sundays with a caveat for the four Sundays before Christmas and an additional Sunday chosen by the operator.

In the early 1990's, leaders of the Jewish religious community in Hungary complained that the greatest Jewish holidays are not public holiday unlike the Christian Holidays, which posed a limitation to their religious freedom. The Hungarian Constitutional Court - like other constitutional courts of the continent had done in similar cases -found that this circumstance did not in itself give rise to an unconstitutionality, because it does not discriminate among the different religions and also noted that the Christian holidays have additional, more secular characteristics and overtone, as well as economic considerations in accordance with societal expectations.[99]

3. Good Friday and the Austrian Legislation, the Achatzi - case

The most recent - and only - case from the past two decades focusing on religious holidays at the workplace in the EU is the Achatzi-case. Certain aspects of religious freedom have already been analysed by national courts and the ECtHR in the past few years in Austria. In the E.S. v. Austria-case[100] for example, the ECtHR found that an Austrian domestic court did not overstep its margin of appreciation when it convicted E.S. of disparaging religious doctrines of the Islam faith pursuant to the Austrian Criminal Code. As a result of a new wave of anti-terrorism measures introduced in the country, the Austrian parliament has also enacted and later amended laws pertaining to Muslims for stricter annual government monitoring of the finances of mosques and Muslim cultural associations focusing on financial flows from abroad. As expected, the

- 95/96 -

Islamic Religious Authority of Austria opposed the law and its amendment claiming that it only applied to the Muslim community, and as such it was discriminatory and interfered with religious freedom.[102]

Origins of religious freedom and tolerance in Austria date back to the Patents of Tolerance of 1781 (Tolerantzpatent) which was one of the most important reforms of Joseph II, granting civic rights to the Jews, provided they would be integrated as active citizens. The body tax was suppressed, distinctive dress codes and bans were eliminated. In January 2011, the percentage of Catholics in Austria was around 64%, while the percentage of Protestants was 3.8%. The Muslims population is the most dynamically growing religious minority in the country, growing from 4.2% in 2001 to 7.9% in 2016.[103] A regulation was adopted in 2015 regarding the recognition of Islam by the State. This regulation refers to several Islamic holidays (Ramadan, Pilgrim and Sacrifice festival, Ashura) and aims to protect the right of Muslims to the full enjoyment of the festivities by affirming that on these days as well as during Friday prayers generally, all avoidable actions that might disturb the festivities are prohibited in the vicinity of places of worship. This regulation does not elevate these holidays to the status of public holidays, nor does it endow Muslim workers with a right to obtain holidays on the specified days, it is however an important step and allows the possibility of including said holidays in collective work agreements. These collective agreements could introduce special rules on holidays provided they do not contradict binding laws, meaning they could include more holidays than the ones defined by the Federal Act on Rest Periods, potentially covering religious holidays or the duty to grant preference to the requests for days off should these coincide with religious holidays.[104]

Good Friday - also known as Holy Friday, Great Friday, Great and Holy Friday - is one of the most sacred holidays of the Christian faith, commemorating the crucifixion of Jesus and his death. As such, it is a public holiday in many predominantly Christian countries worldwide. Examples of European countries celebrating Good Friday as a public holiday include: Andorra, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Hungary (since 2017), Portugal, Spain, Switzerland, Sweden. In France, it is not considered a public holiday, except for Alsace and Moselle, similarly, it is only a regional holiday in Bosnia-Herzegovina. It is a bank holiday in Ireland, and a government holiday in the Netherlands (observed by the government, banks, and insurers).[105]

- 96/97 -

In the predominantly Roman Catholic Austria, Good Friday was a paid holiday only for members of some particular religious denominations under paragraph 7 (3) of the Austrian Law on Rest Periods and Public Holidays. These religions included the Evangelical Churches of the Augsburg and Helvetic Confessions,[106] the Old Catholic Church and the United Methodist Church.[107] If they did work that day, they could claim a wage supplement, but the law did not however prescribe any religious observance, only a formal membership in the recognized minority churches. For those, who did not belong to the abovementioned four churches, it was a working day without the possibility of a wage supplement. This was the case with Mr. Achatzi, an employee at Cresco Investigations, a private detective firm. Mr. Achatzi thus sued before an Austrian court for religious discrimination.[108]

The Austrian Supreme Court (Oberster Gerichtshof) referred multiple questions[109] for a preliminary ruling to the CJEU. In its reference, the Supreme Court pointed out that

- 97/98 -

the religious needs of certain workers were indeed not considered. It also noted that there were certain collective labour agreements which contained terms regarding the days of Yom Kippur in the Jewish Religion and the Reformation Day in Protestant Churches.

The CJEU needed to establish whether this differential treatment could be justified. First and foremost, the CJEU needed to establish whether the Austrian provision constituted discrimination and if so whether it constituted direct or indirect discrimination. This classification is of paramount importance since the different forms of discrimination have different possible justification tests. The CJEU also needed to determine if the treatment could be considered a necessary measure for protecting the rights and freedoms of others i.e. the religious freedom of those who belong to the minority churches, as such complying with legitimate positive measures entrenched in the Directive. If so, an exception could potentially be established allowing for a more favourable treatment of parties experiencing certain social inequalities. In case the existence of discrimination can be established, and it is also found that there were no legitimate reasons underlying it, the CJEU must provide guidance to the national courts by establishing how the legislation should be adjusted, and how the employers are expected to treat employees in the interim period if they worked on Good Friday.[110]

4. The decision of the CJEU and its rationale in the Achatzi-case

Regarding the definition of 'religion' the CJEU referred back to the concept embedded in its previous 'headscarf-decisions'[111] and emphasized that freedom of religion is

- 98/99 -

one of the fundamental rights and freedoms recognized by EU law and that the term 'religion' must be understood as a broad concept, covering both the 'forum internum' and the 'forum externum'.[112]

In matters relating to religious freedom the primary point of reference must be to ascertain whether the individuals (in this case the employees) are in a comparable situation or not. In other words, the CJEU needs to determine, whether the treatment prescribed by the Austrian law impacting Mr. Achatzi, who was not a member of the favoured religious denominations could be compared to those individuals (not necessarily at his workplace) who were. Advocate General Bobek considered the above to be an easy case of discrimination and pointed out, that the issue did not originate in the employee's religious practices or beliefs, but in the national law affording different treatments to members of certain faiths.[113] The problem in his opinion did not stem from allowing believers of certain faiths to have Good Friday off, but from doubling the pay of religiously observant employees who worked on Good Friday while not giving the same supplement to other employees belonging to the minority religions who also worked that day. He clearly considered the measures favouring certain churches to be disproportionate in the sense that they were not appropriate to achieve their original purpose of protecting the religious freedom and were also unnecessary.[114] He also noted the lack of clear definitions for positive actions both under Article 7 (1) of the Directive and the existing case law.[115] In light of these considerations, AG Bobek focused on the impermissible salary discrimination based on religion. [116]

The approach taken by the CJEU mostly followed the Advocate General's guidance and presumed that the status of those employees who do not belong to the aforementioned minority churches - or any church for that matter - and who would request Good Friday to be a public holiday is similar and comparable to those, who do belong to these denominations.[117] The reason for this is that members of the minority churches are entitled to have Good Friday as a public holiday regardless of whether they perform any forms of religious observance this day while they are also entitled to

- 99/100 -

the public holiday pay if they do decide to work regardless of whether they have worked without experiencing 'any obligation or need to celebrate' the religious festivity.

By establishing that these employees are in a comparable situation, the CJEU also declared that the Austrian measure constituted direct discrimination based on religion, implying a strict legitimation test in line with the Directive. The measure failed said test, since it did not seem to be necessary for attaining the objectives of Article 2 (5) of the Charter i.e., inter alia ensuring the protection of the religious freedom of others -even if it originally intended to do so.

A similar approach was taken when considering whether this measure could alternatively be seen as a compensation for the hypothetical disadvantages linked to being a member of the minority churches[118] within the meaning of the Article 7 of the Directive. The CJEU did not question the fact that Member States could retain or adopt specific measures to prevent or compensate disadvantages linked to the grounds covered in the Directive, but the principle of proportionality requires that the derogations are to remain within the dimensions of what is appropriate and necessary in order to achieve the aim.[119] Here the CJEU concluded that the measure went beyond what was necessary to compensate for the alleged disadvantages[120] by treating employees in a comparable situation differently.[121]

To restore equal treatment, and until Austria has amended its legislation[122] in a way that would grant the right to a public holiday on Good Friday to members of certain churches, a private employer must also grant other employees Good Friday as a public holiday if the employee has sought prior permission from the employer to be absent from work. These employees would also be entitled to a payment in addition to their regular salary for the work done that day, in case the employer refuses to approve their holiday request.[123]

The possibly most divisive question was whether Article 21 of the Charter of Fundamental Rights could be directly relied upon before national courts in a horizontal context. The CJEU, while referring back to the Egenberger-case where it ruled that the prohibition of discrimination based on religion or belief is a general principle of EU law,[124] concluded that the prohibition of discrimination laid down in Article 21 is sufficient itself to confer on individuals a right they may rely upon in case of disputes

- 100/101 -

between them, in other words it falls within scope of the EU law.[125] Consequently, when national provisions - even in case their purpose is to implement the EU Law - cannot be interpreted in a manner consistent with the Directive, national courts must rely on Article 21 of the Charter. The application of the principle of horizontal (direct) effect[126] in private disputes is a sensitive issue[127] since it raises essential questions regarding the division of competences between the EU and its Member States, the internal separation of powers between the CJEU and EU legislator (i. e. institutional balance), and the public-private divide.[128]

The question remains whether the decision would have been the same if the law had only given an unpaid day off to the members of the minority churches, this way granting no financial benefit to the same. In this case, one could argue that the employees of these churches would not need an entire day off to practice their religion. Assuming that Mr. Achatzi was not a member of a religion who either wanted Good Friday off or another day not provided by the law for religious celebration or to perform religious rites, there is an argument that his situation would not be comparable. Even so, this would still be discriminatory, as the unpaid day off was not connected to any religious needs, only to the formal membership in the said minority churches. His situation would still be comparable to an employee who was a formal member but treated it as any other day of rest. Whereas an employee, who wished to observe Good Friday, but was not a member of the four Churches would not have the right to a day off.[129]

To summarize the decision, the CJEU concluded that the national legislation that stipulated that only workers of certain Christian Churches have the right for a day off on this religious holiday, or alternatively foresaw an extra pay in case they carry out their work constitutes direct discrimination based on religion. Granting Good Friday as a public holiday to workers who belong to a specific church did not presuppose fulfilling

- 101/102 -

any religious obligation by the employee on that day, consequently, they were free to dispose over this period by resting, undertaking recreational activities etc. At the same time, the law's promise of double pay for working on Good Friday discouraged rather than encouraged these employees to observe their religion's holy day.

The CJEU reaffirmed, that a discriminatory measure may be justified, if it aimed to favour persons and groups who suffered from social inequalities, but this national legislation could not be considered a necessary measure for protecting and promoting the rights of others and did not compensate for any religion-related disadvantages. Cases where the CJEU must consider state measures aiming to protect new or minority religion who are more likely to suffer from societal discrimination and state policies and practices that favour members of traditional churches and religious groups can be expected in the future. This would certainly have powerful ramifications for EU Member States with long traditions of church-state relations and regulating religious holidays.

In line with the CJEU's guidance, the domestic courts will need to rely on EU law as opposed to national law in case of a conflict which further embeds the principle of the supremacy of EU law. This would also mean, that future decisions would have the potential to dismantle certain aspects of the church autonomy despite the EU principle of respecting national church-state relationships as well as domestic legislations, agreements surrounding it.[130]

Shortly after the CJEU issued its guidance, the Austrian Supreme Court confirmed in its own follow-up judgment that all employees are entitled to public holiday pay when working on Good Friday, but only in cases where the employee had previously asked the employer to be granted leave of absence on this day and the employer did not comply with the request. At the same time, the Supreme Court referred the case to the first court for a new hearing and decision.[131] The Austrian law has since been amended, workers are now allowed to make use of 'personal holidays' taken from the 30 (or 37 depending the case) holiday days they are entitled to per year and Good Friday is no longer a legal holiday, as the regulation allows workers to once a year unilaterally determine when they want to take a day off, thereby differentiating this day from the rest of the typical vacation days. Unlike regular holiday applications employers can't refuse the personal holiday, even where work is considered to be essential for operational reasons.[132] If workers are asked by the employer not to take the personal holiday and decided to work on that day, they will be entitled to holiday pay, but another personal holiday will not be provided in the current vacation year.

Several issues remain to be settled, as other than provided in the Austrian Paid Holiday Act employers have little say in the choice of the date of rest. Concerns arose

- 102/103 -

that an abusive use of the unilateral days could be expected, for example when several employees take such a personal holiday at the same time, causing operations to come to a standstill. It is also unclear whether employees can interrupt existing schedules or shifts through their unilateral choice and how these gaps may be filled by employers.[133] The new regulation also fails to reflect on the Yom Kippur provision in the general collective bargaining agreement - like the Good Friday problem - which may also give raise to concerns in the future.[134]

The new regulation gave rise to a number of criticisms, including from minority churches who filed a constitutional complaint with the Constitutional Court requesting the repeal of the Good Friday regulation, reclaiming it would directly interfere with their inner church life and would also violate the constitutionally guaranteed right of religious freedom. In addition, the applicant churches were also of the view that the principle of equal treatment had been violated, as the Roman Catholic Church was not deprived of a holiday. Furthermore, they argued that their right to freedom of association as employers were also violated.[135]

The Court noted that religious freedom is protected at constitutional level by Article 15 of the Basic Law on the General Rights of Citizens (hereinafter 'StGG') and that legally recognized churches and religious communities have the right to administer their internal affairs independently in line with Article 15 of StGG and Article 9 of the ECHR, which must be read in conjunction. The contested provisions, that is, the rules governing working hours and labour law did not directly affect the legal sphere of churches. Furthermore, the Constitutional Court held that the applicant churches had no right to introduce or maintain a specific legal holiday. The Court also pointed out that while a specific selection of public holidays may initially have had religious grounds, in today's context these holidays mainly pursue goals of personal rest and relaxation. As such, the abolition of the public holiday status of Good Friday did not directly affect the churches' legal sphere.

The Achatzi-case has multiple aspects that are relevant for religious minorities. First, it shows how the prohibition of discrimination constrains measures aimed at the protection of religious minorities by identifying limitations. These minorities are in most cases are also ethnic minorities, hence the intersecting identities resulting in multiple levels of discrimination. Where there is a measure, which could protect the minority without excluding adherents of other religions from the benefits of the measure, said benefits should also be afforded to the latter. The ruling also shows, that the CJEU scrutinizes possible exceptions to the prohibition of direct discrimination, implying a high level of protection against differential treatment based on religion. The

- 103/104 -

case also emphasized, that the CJEU does not easily accept measures as a legitimate form of affirmative positive action[136] without a supporting and justifiable rationale.

The Achatzi-case also showed that the CJEU's analysis is deeply rooted in a concern over individual equality and does not condone laws that confer blanket privileges to certain religious groups.[137] The Austrian law is an example of certain religious groups being privileged over others because they had the political capital and power to press for a particular right in response to the social-political situation at the time (the 1950s in this case). These privileges raise issues since they are not granted to the more numerous and more recently arrived religious minorities (for example Muslims).

5. Conclusions

Supranational courts provide a fresh perspective for religious freedom-related cases which is not influenced by the historical, traditional national framework.[138] The principle of equal treatment is one of the main principles driving EU integration, some might even argue, that it is the main principle.[139] Today, the issue of religion and its impact on workplaces is becoming increasingly relevant, particularly with regard to working and non-working times.[140] There are many sensitivities and expectations which must be managed in the sphere of employment, while at the same time, the employer is primarily interested in maximizing the productivity of the religious, agnostic and atheist co-workers. Accommodating (which does not mean giving preference to) certain manifestations during religious holidays may mean that agnostic or atheist employees have to pick up work on these days, changing their work patterns. This could potentially result in a snowball effect and ultimately, ill feelings.[141]

In most countries the organization of labour has - albeit implicitly - traditionally taken the specificities of the dominant religion into account. This is epitomized in the choice of the days of rest that usually reflect the holidays of the majority religion(s).[142] So what happens when members of a minority religion ask for adaptations in regulations

- 104/105 -

enabling them to practice their faith? How should employers react to such demands?[143] What happens to the religious needs of workers who observe minority religious obligations, for example ritual fasting, and would like to perform prayers[144] during the day or request extraordinary leave of absence? Should the employer check whether they indeed sincerely observe these religious obligations?[145]

Demands for accommodating religious festivities present a dual problem in case of the Ramadan and Eid al-Adha, for example.[146] A great number of employees take the day off based on their personal preferences, but an additional problem presents itself when the number of Muslim employees is high at a given workplace. A company either accepts to work with reduced personnel if possible, or anticipates these holidays in planning its work schedule. In the public sector on the other hand, the continuity of service must be guaranteed, hence the scope of potential accommodation is more limited. The concept of neutrality is also frequently invoked, particularly in countries with historical secular traditions. In the education system a paradox situation may also be observed, since students may have the right to stay home during religious festivities in certain cases, while the teachers on the other hand do not have this option.[147]

It would seem tempting to interpret the overrepresentation of minorities in religious freedom related cases at work as a sign of their rising religiosity that contrast with the decline of religious practice in the majority population. This phenomenon of supposed growing religiousness among Muslims is often portrayed as a challenge to the European tradition of secularity, becoming a common narrative in European media.[148] Religion is here to stay, and freedom of religion is unique in its potential to challenge almost every area of law. Developments and signs of the contemporary European Zeitgeist cannot be overlooked when considering religious identity and diversity, as it relates to the workplace, education and every aspect of one's life, creating a crucial test case of policies pursuing substantive or genuine equality in Europe. As a powerful expression of personal identity, religion has again made its way into the amalgam of the contemporary European workplace and issues related to this basic human right are increasingly raised before domestic and international courts. The role and position of

- 105/106 -

religion and religious identity itself is often controversial, contentious and evolving, unsurprisingly so, since the definition of religion itself is also divisive.[149]

It seems, that while in the 1990s and 2000s the questions around gender, race and ethnicity were placed at very centre of the rediscovery of the European Union's antidiscrimination law, and religion seemed to stand in the background of the European Agenda, we can now see a clear paradigm shift starting with the late 2010's.[150] Particularly in Western Europe, there is a transition from the secular to a so-called 'post-secular society' in which 'secular citizens' have to afford (a previously denied) respect for 'religious citizens'. The latter now feel encouraged to draw upon from their religious convictions to offer criticism of established solutions.[151] European nations are undoubtedly changing culturally and socially, acutely so in countries such as France, Germany and Belgium. Across the religious spectrum, there are also forces pushing toward progress and reaction, assimilation, separatism, secularism, fundamentalism, tolerance, and violence.[152]

Upon reviewing the Vivian Prais-case, although the case is almost 50 years old, we may conclude that its fundamental logic still holds water, since employers may attempt to accommodate faith-motivated requests, but ultimately the organizational logic will prevail. The etymology and the contemporary lay meaning of the English word ' holiday' encapsulates the tension against which the question of religious holidays in employment must be conceptualized. The word 'holiday' retains much of its religious overtone, stemming from 'holy' days, referring to moments reserved for sacred rites and celebrations. In its contemporary use on the other hand, 'holiday' has become a quasi-secular synonym for vacations and days off, irrespective of their motivation, religious or otherwise. Naturally, this is only a thumb-rule for the English language, nevertheless it resonates in other languages and cultural contexts as well.[153]

The relationship between the EU and churches has been peppered with heated controversies around the influence of the sacred upon the constitutional structure of the EU, the competencies as well as the limits of a European policy.[154] The phenomenon of globalization - contrary to previous expectations - has made cultural diversity and pluralism even more evident. As a consequence of multiculturalism, states are

- 106/107 -

confronted with an increasing number of conflicts between minority norms and the national law designed for the cultural majority.[155]

Recurring issues for religious minorities span a broad range of topics, including the recognition of a person's religious affiliation, the registration of a religion; the possibility of establishing a religious organization, building and maintaining places of worship, the accommodation of religious diversity at work (focusing on working schedule, religious holidays, dietary requirements, rules concerning slaughter,[156] dress code) and education as part of broader questions pertaining to a religious way of life. In the heart of it all is the right not to be discriminated against based on religion.[157]

Most societies are organized in a way which historically makes it relatively easy for members of the religious majority to practice their religion: work schedules in employment and education are designed to facilitate their observance of the weekly holy day and religious holidays.[158] At the same time, it is also unsurprising, that religious minorities, especially the ones with growing numbers are increasingly vocal about their religious freedom and its protection.

A quote by Bengamin L. Berger involuntarily springs to mind:[159]

"The story of religion is, in substantial part, the story of adaptation and response to changing social worlds and, for centuries, the law has been one important figure in this dynamic history. Law has not just struggled with questions of religious freedom but has challenged religion to test the resiliency, complexity, and resources of its own traditions. An important challenge for contemporary human rights law is to ensure that it continues to encourage this dynamism rather than serving as a freezing agent."

- 107/108 -

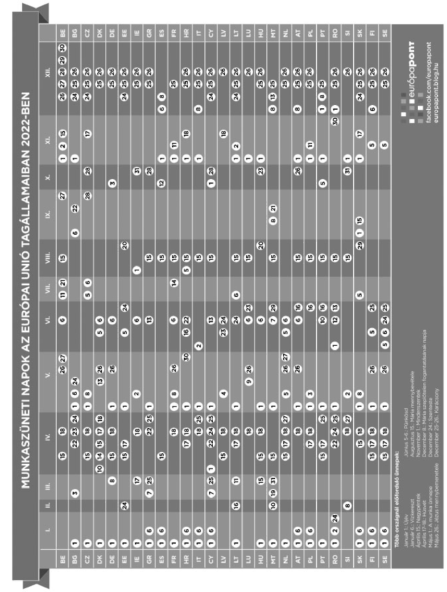

Annex

Public Holidays in the EU Member States as of 2022[160] ■

NOTES

[1] Supported by the ÚNKP-21-4 New National Excellence Program of the Ministry for Innovation and Technology from the source of the National Research, Development and Innovation Fund.

[2] Erika C. Collins: Religious Discrimination in International Employment Law. The Law Reviews, Employment Law Review, 02. 16. 2022. https://rb.gy/6atz1r

[3] Kristin Henrard: Duties of reasonable accommodation on grounds of religion in the jurisprudence of the European Court of Human Rights: A tale of (baby) steps forward and missed opportunities. International Journal of Constitutional Law, Vol. 14., No. 1. (2016) 962-963.

[4] Anna Sugier-Szerega: Christian Holidays and the Formation of Religious Identity. In: Leon Dyczewski (ed.): Secularization and the Development of Religion in Modern Polish Society. Polish Philosophical Studies, XIV Christian Philosophical Studies, XIII. The Council for Research in Values and Philosophy, 2015. 99-100.

[5] Holidays could generally be grouped into three categories. Firstly, there are holidays focusing on nation-building, commemorating events that were important for the founding of the state or the main ethnic group. Secondly, there are the holidays based on religion (and hence in the primary scope of this study). The third category cannot be directly linked to the first two and is more general or universal in nature (New Year's Eve for example). See: Zhidas Daskalovski: Public Holidays and Equality for Muslims in Western Europe. Journal of Muslim Minority Affairs, Vol. 37., No. 3. (2017) 333-334. Religious holidays have further sub-categories. In Poland for example there are 5 such categories: 1) Catholic holidays free of work in line with §9. of the concordat between the Holy See and Poland, (2) Catholic holidays free of work but not according to the concordat, (3) Catholic holidays not free of work (4) holidays of other churches and associations free of work and learning for confessors; (5) holidays of other churches and confessional associations not free of work and learning for confessors. See: Bartosz Hordecki: The Escape from Everyday Life? Accounts of Holidays and Anniversaries in TV news. Środkowoeuropejskie Studia Polityczne, 2011/1. 107.

[6] See: Sugier-Szerega op. cit. 101.

[7] Religions also tend to have gender-specific requirements, focusing on the manifestation of belief by wearing reliigous clothing or symbols. The women are often expected to dress in a modest manner in line with the Quran but the Orthodox Christian and Jewish texts also state that women should cover their hair and dress in a loose clothing. See Castillo Ortiz - Amal Ali - Navajyoti Samanta: Gender, intersectionality, and religious manifestation before the European Court of Human Rights. Journal of Human Rights, Vol. 18., No. 1. (2019) 76-91.

[8] Schanda, Balázs: A vasárnap védelme - Néhány alapjogi szempont. Iustum Aequum Salutare, Vol. 11., 2015/2. 138.

[9] Fareena N. Malfa - Zehra Aftab - Sheheryar Banuri: When norms collide: The effect of religious holidays on compliance with COVID guidelines. 11. 27. 2020. https://rb.gy/tknvho

[10] See: Andrew C. Miller - Alberto A. Castro Bigalli - Phanniram Sumanam: The coronavirus disease-2019 pandemic, social distancing, and observance of religious holidays: Perspectives from Catholicism, Islam, Judaism, and Hinduism. International Journal of Critical Illness & Injury Science, Vol. 10., No. 2. (2020).

[11] C-193/17. Cresco Investigation GmBH v. Markus Achatzi, Judgment of the Court (Grand Chamber), 22. January 2019. [ECLI:EU:C: 2019:43].

[12] János Martonyi: Law and Identity in the European Integration. Hungarian Journal of Legal Studies, Vol. 60., No. 3. (2019) 228.

[13] Sergio Carrera - Joanna Parkin: The Place of Religion in European Union Law and Policy: Competing Approaches and Actors inside the European Commission. RELIGARE Working Document, No. 1 / September 2010. 7-8.

[14] Directorate - General for Internal Policies: Religious practice and observance in the EU Member States, 2013. http://www.europarl.europa.eu/studies

[15] Andrea Pin - John Witte, Jr.: Meet the New Boss of Religious Freedom: The New Cases of the Court of Justice of the European Union. Texas International Law Review, Vol. 55. (2019) 224-226.

[16] Florian Grötsch: The Mobilization of Religion in the EU (1976-2007): From "Blindness to Religion" to the Anchoring of Religious Norms in the EU. Journal of Religion in Europe, Vol. 2. (2009) 232-235.

[17] Pin-Witte op. cit. 236-237.

[18] See Florian Grötsch: Lost in Translation - Unterschiedliche Fassungen der Religionsfreiheit in Europa. In: Jamal Malik - Jürgen Manemann (eds.): Markierungen im religiösen Feld. Münster, Aschendorff, 2009.

[19] See more at: Caroline Sägesser - Jan Nelis - Jean-Philippe Schreiber - Cécile Vanderpelen-Diagre: Religion and Secularism in the European Union. Observatory of Religions and Secularism (ORELA). Report, September 2018.

[20] See more at: Pew Research Center: How religious is your state? 2. 29. 2016. https://rb.gy/figpvm

[21] David W. Miller - Timothy Ewest: A new framework for analyzing organizational workplace religion and spirituality. Journal of Management, Spirituality and Religion, Vol. 12., No. 4. (2015) 2.

[22] See more: Fabienne Bretscher: Religious Freedom of Members of Old and New Minorities: A Double Comparison. Erasmus Law Review, Issue 3. (2017) 151-162.

[23] 'Parekh Commission' in short.

[24] See more: Katayoun Alidadi: Charting perspectives, positions and recommendations in four commission reports -Reasonable accommodation for religion or belief as barometer. In: Katayoun Alidadi - Marie-Claire Foblet (eds.): Public Commissions on Cultural and Religious Diversity National Narratives, Multiple Identities and Minorities. London, Routledge, 2018.

[25] See more: Lucy Vickers: Religious Freedom in the UK workplace: Promoting Diversity at Work. Hungarian Labour Law E-Journal, 2019/1 7.; and: London.Gov.Uk: Diwali Festival. 10. 28. 2018. https://www.london.gov.uk/events/2018-10-28/diwali-festival-2018

[26] See more at: Francesco Buffa: Rapporto di lavoro degli extracomunitari, tomo I, Soggiorno per lavoro e svolgimento del rapporto., Cedam, 01/2009. 1448.

[27] Brent F. Nelsen - James L. Guth: Religion and the Struggle for European Union: Confessional Culture and the Limits of Integration. Washington, Georgetown University Press, 2015. 119.

[28] Leon Dyczewski (ed.): Secularization and the Development of Religion in Modern Polish Society Polish Philosophical Studies. XIV Christian Philosophical Studies, 2015. 15-16.

[29] See more: Daniele Hervieu-Léger: Religion und Sozialer Zusammenheit in Europa. Transit: Europäische Revue, Issue 26. (Summer 2004) 101-119.

[30] The number of public holidays intersecting with religious holidays may change from time-to-time. For example, in Portugal, 2 religious holidays lost - Corpus Christi, 5 October, 1 November and 1 December - the public holiday status. See more at: David Carvalho Martins: Labour Law in Portugal between 2011 and 2014. National Report. 2014. https://tinyurl.com/5fsuac87

[31] Easter Monday, Ascension, Pentecost Monday, Assumption, All Saints' Day, Christmas. See more at: Fabienne Kéfer: Religion at work. The Belgian experience. Hungarian Labour Law E-Journal, 2019/1.

[32] Please also see the Annex for a more detailed chart on the public holidays in the EU Member States.

[33] Daskalovski op. cit. 337-338.

[34] In addition to the holidays, another example of the Christian influence on employment regulations is that European legislations legalizing abortion usually recognize the right to conscientious objection for doctors and nurses. See for example the legislation in France: Article 2212-8 of the Public Health Code (Code de santé publique) (Loi No. 2001-588 du 4 juillet 2001, J.O. 7 July 2001).

[35] Paczolay, Péter: A lelkiismereti és vallásszabadság. In: Halmai, Gábor - Tóth, Gábor Attila (ed.): Emberi jogok. Budapest, Osiris, 2008. 550-551.

[36] There are quite a few exceptions around the world of course. Nepal for example has a six-day working week, as the working days are Sunday - Friday. In Saudi-Arabia, though the week has five working days, it starts on Sunday, not on Monday and we can see similar patterns in other Muslim countries. In Israel, the working week is Sunday - Thursday, following the Jewish calendar and so on.

[37] In its judgment of 12 November 1996, in Case C-84/94, United Kingdom v. Council, the CJEU established, that "[...] whilst the question whether to include Sunday in the weekly rest period is ultimately left to the assessment of Member States, having regard, in particular, to the diversity of cultural, ethnic and religious factors in those States [...] the fact remains that the Council has failed to explain why Sunday, as a weekly rest day, is more closely connected with the health and safety of workers than any other day of the week. In those circumstances, the applicant's alternative claim must be upheld and the second sentence of Article 5, which is severable from the other provisions of the directive, must be annulled."

[38] A survey conducted in 2016 asked Muslim respondents if they experienced any discriminatory situations at work because of their ethnic or immigrant background, and some of these were linked to religious practices. About 12% of the Muslim respondents said that they were not allowed to take time off for an important religious holiday, service or ceremony, which was the most frequently referred concern. See: Second European Union Minorities and Discrimination Survey Muslims - Selected findings. European Agency for Fundamental Rights, 2017. 31.

[39] An alternative way around obstacles originating from religiously mandated practices conflicting with mainstream professional duties is presented by the French 'Bureau du Chabbath' which was set up to link Jewish job applicants with open positions that guarantee the Sabbath and days off for Jewish festivals. More commonly though, there are individual strategies and coping mechanism, implying personal or family sacrifices, choosing from a limited range of employment options or self-employment, ultimately resorting to pulling out from the labor market. See: Efrat Tzadik: Jewish Women in the Belgian Workplace an anthropological perspective. In: Marie-Claire Foblets - Katayoun Alidadi (eds.): A Test of Faith? Religious Diversity and Accommodation in the European Workplace. Farnham, Routledge, 2012. 225-242.

[40] Katayoun Alidadi: Reasonable Accommodations for Religion and Belief: Adding Value to Article 9 ECHR and the European Union's Anti-Discrimination Approach to Employment? European Law Review, Vol. 37., No. 6. (2012) 699-700.

[41] Wasif Shadid - Sjoerd van Konigsveld (eds): Religious Freedom and the Neutrality of the State: The Position of Islam in the European Union. Paris, Peeters, 2001. 2-3. See more at: Matthias Koenig: Incorporating Muslim Migrants in Western Nation States: A comparison of the United Kingdom, France, and Germany. Journal of International Migration and Integration / Revue de l'integration et de la migration internationale, Vol. 6., No. 2. (2005) 219-234.

[42] Deirdre McCann: Decent working hours as a human right: intersections in the regulation of working time. In: Colin Fenwick - Tonia Novitz (eds.): Human rights at work: perspectives on law and regulation. Oxford, Bloomsbury, 2010. 509-528.

[43] Article 17 states:

"1. The Union respects and does not prejudice the status under national law of churches and religious associations or communities in the Member States.

2. The Union equally respects the status under national law of philosophical and non-confessional organizations.

3. Recognizing their identity and their specific contribution, the Union shall maintain an open, transparent and regular dialogue with these churches and organizations."

[44] See for example:

Article 10: Freedom of thought, conscience and religion Article 14: Right to education Article 21: Non-discrimination

Article 22: Cultural, religious and linguistic diversity Article 52: Scope of guaranteed rights

[45] "1. Any discrimination based on any ground such as sex, race, colour, ethnic or social origin, genetic features, language, religion or belief, political or any other opinion, membership of a national minority, property, birth, disability, age or sexual orientation shall be prohibited.

2. Within the scope of application of the Treaties and without prejudice to any of their specific provisions, any discrimination on grounds of nationality shall be prohibit."

[46] Council Directive 2000/78/EC of 27 November 2000 establishing a general framework for equal treatment in employment and occupation.

[47] Article 2 (5):

"This Directive shall be without prejudice to measures laid down by national law which, in a democratic society, are necessary for public security, for the maintenance of public order and the prevention of criminal offences, for the protection of health and for the protection of the rights and freedoms of others."

[48] Article 4:

"1. Notwithstanding Article 2(1) and (2), Member States may provide that a difference of treatment which is based on a characteristic related to any of the grounds referred to in Article 1 shall not constitute discrimination where, by reason of the nature of the particular occupational activities concerned or of the context in which they are carried out, such a characteristic constitutes a genuine and determining occupational requirement, provided that the objective is legitimate and the requirement is proportionate."

[49] See the following two cases from the recent case law of the CJEU: C-414/16. Vera Egenberger v. Evangelisches Werk für Diakonie und Entwicklunge. V., Judgement of April 17., [ECLI:EU:C:2018:257] and C-68/17. IR v. JQ, Judgement of 11 September 2018. [ECLI:EU:C: 2018:696].

[50] Directive 93/104/EC of 23 November 1993 was replaced by Directive 2003/88/EC of 4 November 2003.

[51] Case 84-94. United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland v. Council of the European Union. Judgement of 12 November 1996. [ECLI:EU:C: 1996:431]

[52] European equality law review - European network of legal experts in gender equality and nondiscrimination. Brussels, European Commission, Directorate-General for Justice and Consumers, 2018. 65. [Hereinafter: EC (2018)]

[53] See for example the Communication from the Commission, Reviewing the Working Time Directive, 21 Dec. 2010, COM (2010) 801 final, 11: "[...] the question of whether weekly rest should normally be taken on a Sunday, rather than on another day of the week, is very complex, raising issues about the effect on

health and safety and work-life balance, as well as issues of a social, religious and educational nature. However, it does not necessarily follow that this is an appropriate matter for legislation at EU level: in view of the other issues which arise, the principle of proportionality appears applicable."

[54] Article 7 (1):