Gergely Ferenc Lendvai[1]: Hybrid Regimes and the Right to Access the Internet - Findings from Turkey and Russia in the Context of the Judgments of the European Court of Human Rights (ELTE Law, 2024/2., 87-107. o.)

https://doi.org/10.54148/ELTELJ.2024.2.87

Abstract

The liaison between authoritarian political governance and Internet access is complex, particularly in hybrid regimes like Turkey and Russia. This paper focuses on the right to access the Internet as perceived by European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) case law involving the two aforementioned countries, examining the balance between political interests and individual rights. Through comprehensive case comparisons, the present research outlines tensions between European human rights principles and the actions of hybrid regimes. The paper's focal point lies in examining multiple landmark cases from Turkey and Russia to trace the evolution of ECtHR judgments on Internet freedom. Moreover, the paper reflects on broader implications, questioning whether ECtHR decisions enhance individual rights protection in the digital age and suggests avenues for improving Internet governance in hybrid regimes through international legal mechanisms. The paper is methodologically founded on a comprehensive literature review and legal case comparisons. The findings reveal a critical endangerment of right to access the Internet, most notably in Russia, whose withdrawal from the European Convention on Human Rights exacerbates concerns over freedom of expression and digital rights protection. In Turkey, frequent Internet blockages and legal reforms continue to erode digital freedoms. This research proposes that, despite ECtHR's rulings aimed at reinforcing individual rights, the broader implications remain unresolved as hybrid regimes persistently challenge and undermine the principles of human rights protection in the digital age.

- 87/88 -

Keywords: human rights, European Court of Human Rights, Turkey, Russia, right to access the Internet, digital divide, hybrid regimes

I. Introduction

As the Internet has become the primary source for imparting and receiving information, one could confidently state that those who can access it can access the world itself. An integral and, much rather, inherent segment of our lives, the Internet allows users to communicate with friends and colleagues, shop, create, generate and consume content and work like never before in history. As Merten Reglitz states, however, in our affluent world, Internet access is so readily available that it is easy to forget how fundamentally it shapes our lives.[1] Nonetheless, it is even easier to forget how evident and given it seems, especially for those living in the Global North, that one has access to the Internet all of the time. The present research focuses on a very different Internet experience: one which can be understood within the theoretical and practical frameworks of censorship,[2] state supervision, propaganda,[3] disregard for minorities and their rights, and the suppression of political and religious views.

The paper's primary focus lies in understanding challenges related to the right to access the Internet (RATI) in two countries, often described as hybrid regimes,[4] Turkey and Russia. To support the examination, the research is structured in a tripartite manner. First, the term 'hybrid regimes' is conceptualised using the pertaining academic literature. At this point, I examine how and why both Turkey and Russia may be regarded as hybrid regimes, and I introduce the principal concerns related to Internet usage, access and coverage in a hybrid political system. Second, to contextualise the theoretical background, multiple key cases involving the case law of the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR or Court) in which either Turkey or Russia was the respondent party will be examined and highlighted. These cases serve as the core of the study, as the Court has underlined a myriad of principles guiding the judgments concerning the right to access the Internet. This segment covers crucial cases involving Article 10 of the European Convention of Human Rights (ECHR)

- 88/89 -

from the Cengiz judgment,[5] a case concerning the wholesale blocking of the very large online platform YouTube for Kharitonov and related cases in Russia[6] involving collateral blockings of multiple highly frequented websites. The examination aims to synthesise the findings of the ECtHR and highlight the guiding principles concerning the right to access the Internet. To provide a critical view of the above, the paper also includes perspectives about the future of the right to access the Internet in Turkey and Russia. This section underlines the possible detrimental impacts of digital authoritarianism in the online sphere, an expression used to describe the hindering of human rights, especially freedom of expression, on the Internet.[7]

The present paper aims to contribute to the legal scholarly reception concerning the right to access the Internet and the polemics of hybrid regimes and their liaison with the Internet. A further objective of the study is to amplify the discourse on the issues in hybrid political systems and foster discourse on the possibilities to mitigate the risks thereof. Last, this paper aims to contribute to the ongoing research on discriminatory Internet access cases and the ever-developing legal literature on the relationship between censorship and the role of the Internet as the primary field where one can express oneself.

II. Conceptualisation of Hybrid Regimes and their Relation to Freedom of Expression Online

'Is Russia a democracy?' commences Larry Diamond in his study on hybrid regimes.[8] Despite the simplicity of the question, providing an answer involves issues of near-unimaginable complexity; from pseudodemocracies[9] to the historical essence of liberal democracies,[10] hybrid regimes question the fundamentals of what it means for a society to be democratic, free and open. To lay the foundation for the investigation of the case of access to the Internet in Turkey and Russia, it is essential first to conceptualise what it means to be a hybrid regime. According to Ali Riaz, who refers to Terry Linn Karl, one of the first scholars to define the phenomenon,[11] hybrid regimes are best described as grey areas between

- 89/90 -

consolidated democracy and blatant authoritarianism.[12] Though definitions vary depending on theoretical orientations,[13] an illustrative and guiding conceptualisation that can be interconnected with the definition of Karl and Riaz comes from Leonardo Morlino, whose definition has been cited in many articles on the issue. Morlino describes hybrid regimes as

A set of institutions that have been persistent, be they stable or unstable, for about a decade, have been preceded by authoritarianism, a traditional regime (possibly with colonial characteristics), or even a minimal democracy and are characterised by the break-up of limited pluralism and forms of independent, autonomous participation, but the absence of at least one of the four aspects of a minimal democracy.[14]

Whether Turkey and Russia are hybrid regimes has been confirmed by decades of scholarly literature. Per Joakim Ekman's hybrid regime indicator and Henry E. Hale's study,[15] Russia is the blueprint of a hybrid regime, while Turkey is close to ticking all the boxes that make it a perfect hybrid regime.[16] To specify, Russia's status as a hybrid regime stems from its amalgamation of democratic and authoritarian traits. Despite nominal democratic processes such as periodic elections and institutional structures,[17] authority is heavily centralised under President Vladimir Putin and his close associates. The government exerts stringent control over media platforms, stifles political dissent and restricts civil liberties, creating an environment where opposition voices are marginalised and dissenters face severe consequences.[18] This hybrid nature enables the regime to project an illusion of democratic governance while consolidating authoritarian control, thereby allowing Putin's administration to suppress opposition effectively and maintain power.

In the case of Turkey, despite democratic institutions such as regular elections and a parliamentary system, power has become increasingly concentrated under President Recep Tayyip Erdogan and the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP). Erdogan's government is often criticised for having gained unprecedented control over media outlets, using legal

- 90/91 -

measures to suppress political opposition and imposing restrictions on civil liberties;[19] as a result, dissenting voices are being marginalised, and individuals who express dissent often face repercussions.[20]

III. Cases from Turkey and Russia

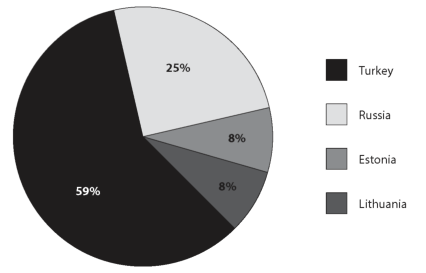

The singling out of two hybrid regimes out of many is a classic case of when a research interest meets research gaps. The ECtHR case law related to the RATI presents a striking picture of how Turkey and Russia 'dominate' cases associated with RATI. Out of 13 cases directly linked to the RATI, 11 are from these two countries, and all general/blanket and content restrictions are particularly and exclusively from these two countries. The figure below presents the overall picture of ECtHR cases related to the RATI.

Figure 1: Statistics concerning countries involved in cases related to the RATI before the ECtHR as of 28 March 2024 (Source: Own editing)

Furthermore, the ECtHR's cases related to RATI involving Turkey and Russia may be divided into two major categories with three subcategories as could be seen in the following table.

- 91/92 -

Table 1: Distribution of cases before the ECtHR concerning RATI (Source: Own editing)

| Cases related to RATI before the ECtHR | ||

| Internet access-blocking measures | Restrictions on Prisoners' RATI | |

| Wholesale/blanket blockings | Content blocking | |

| • Ahmet Yildirim v Turkey • Akdeniz v Turkey • Cengiz and Others v Turkey • Vladimir Kharitonov v Russia, OOO Flavus and Others v Russia, Bulgakov v Russia and Engels v Russia • Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. v Turkey • Taganrog LRO and Others v Russia | • Kablis v Russia • Akdeniz and Altiparmak v Turkey no. 1 (pending) • Akdeniz and Altiparmak v Turkey no. 2 (pending) | • Ramazan Demir v Turkey • Mehmet Reçit Arslan and Orhan Bingöl v Tsurkey |

In the following segments, short summaries of the cases will be presented, followed by a critical analysis of and lamentation about the future of RATI in Turkey and Russia. As the paper's objective is to cover the specific cases of wholesale blockings and the complete restriction of the RATI, these cases will be analysed solely. However, as not many scholars have covered the particular issues regarding content blockings, and cases regarding the RATI of prisoners before the ECtHR have only been recently examined by Gergely Gosztonyi and Gergely Ferenc Lendvai,[21] this paper also serves as an exposition of the prevailing European jurisprudential landscape concerning the RATI, offering a comprehensive portrayal of its nuanced doctrinal intricacies.

1. Ahmet Yildirim v Turkey[22]

The first ECtHR case to deal with the issue of RATI was the Ahmet Yildirim v Turkey case. Per the facts of the case, Turkish national Ahmet Yildirim owned a website hosted by the Google Sites service. The applicant published his academic writings and articles on the site as well as opinion pieces on various issues.[23] In June 2009, the Denizli Criminal Court of First Instance issued an order to block an Internet site accused of insulting the memory of

- 92/93 -

Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, founder of the Turkish Republic, as part of the preventive measures imposed during the ongoing criminal proceedings against the disputed site's owner.[24] The Telecommunications Directorate (PIT) was tasked with executing this order.[25] Subsequently, the PIT requested that the court expand the scope of the order to block access to the entirety of Google Sites on which both the respective site and another owned by the applicant were hosted.[26] The PIT argued that this was necessary as the owner of the offending site resided abroad, making it challenging to block just that specific site.

Consequently, access to all of Google Sites was blocked, including Mr. Yildirim's site. Despite the applicant's attempts to resolve the issue, the court's blocking order persisted and by April 2012, the applicant was still unable to access his own website. He noted that, to his knowledge, the criminal proceedings against the owner of the offending site had been halted due to the inability to ascertain the accused's identity and address, particularly since the latter lived outside the country.[27] The applicant challenged the national courts' decision before the ECtHR.

The applicant alleged a violation of his right to freedom of information under Article 10 of the ECHR due to the blocking of Google Sites, which he argued amounted to indirect censorship. He contended that the repercussions were disproportionate and criticised the lack of fairness and impartiality in the blocking process. Though the Government did not respond, the Open Society Justice Initiative (OSJI) intervened, likening the blocking to prior restraint and cautioning against the risks of 'collateral censorship'. They highlighted the absence of safeguards against arbitrariness in the Turkish system, resulting in numerous prolonged blockades of platforms like YouTube and Google services without adequate oversight. This contrasted with practices in France, Germany and the UK, where more targeted blocking measures had been implemented.

The ECtHR recognised the applicant's ownership and usage of a website for publishing academic work and views associated with various fields. The Court emphasised that while Article 10 of the ECHR does not prohibit prior restrictions on publication outright, it also stressed the need for the meticulous scrutiny of such measures due to their inherent risks. This is especially critical for press freedom, as delays in publication can render information obsolete and diminish its value.[28] Highlighting the significance of websites in fostering freedom of expression, the Court referenced previous rulings[29] that emphasised the role of the latter in facilitating public access to news and information. It noted that Google Sites, a

- 93/94 -

platform enabling website creation and sharing, constitutes a means of exercising freedom of expression.[30]

The Court highlighted the nature of the case's central issue as the collateral impact of a preventive measure adopted in a judicial proceeding. Despite Google Sites and the applicant's site not being directly involved, the PIT blocked access to both sites to enforce a measure ordered by the Denizli Criminal Court. This constituted a form of prior restraint, occurring before a judgment on the merits. The Court deemed such a measure intended to affect Internet accessibility as triggering the defending state's liability under Article 10. The contested blocking resulted from an initial ban on a third-party website, which extended to Google Sites, which affected the applicant's website hosted on the same domain. Despite the limited scope, the restriction significantly curtailed Internet access, impacting the exercise of freedom of expression and information. Consequently, the Court concluded that the measure constituted the interference of public authorities with the individual's right to freedom of expression, including the freedom to receive and communicate information or ideas.

Applying the three-part cumulative test, the Court emphasised that the phrase 'prescribed by law' in Article 10(2) implied not only that the impugned measure must have had a basis in domestic law but also pertained to the quality of the law itself. It required the accessibility of the law to the individual concerned, who must have been able to foresee its consequences and its compatibility with the rule of law. In this case, the Court observed that blocking access to the website involved in the judicial procedure had a legal basis, namely Article 8(1) of Law No. 5651. However, the applicant argued that Article 8(1) did not meet the requirements of accessibility and foreseeability, alleging its uncertainty. The question at stake was whether, at the time the blocking decision was made, there existed a clear and precise norm that would enable the applicant to regulate his conduct accordingly. The Court noted that under Article 8(1) of Law No. 5651, a judge could order blocking access to Internet publications if there were sufficient grounds to suspect that they constituted offences. However, neither the applicant's website nor Google Sites per se was the subject of a judicial procedure under Article 8(1).

Moreover, there was no indication that the law allowed for the blocking of an entire Internet domain, such as Google Sites. Furthermore, the Court observed that Article 8(3) and (4) of Law No. 5651 granted extensive powers to an administrative body (the PIT) in executing a blocking decision initially adopted for a specific site. In summary, the Court found that Article 8 of Law No. 5651 did not meet the Convention's foreseeability requirement and lacked protection for the applicant, constituting a violation of Article 10.

- 94/95 -

2. Akdeniz v Turkey[31]

On 26 June 2009, the Beyoğlu Public Prosecutor's Office, upon a request from the MÜYAP (Professional Union of Phonogram Producers), decided to block access to 'myspace.com' and 'last.fm' due to alleged copyright violations. Based on Article 4 of Law No. 5846 on artistic and intellectual works, the decision required Internet providers to suspend services within three days, with a seven-day window for opposition.[32] No opposition was lodged by the affected websites or their providers by the deadline. On 29 September 2009, the applicant, Yaman Akdeniz, a user of the aforementioned sites, contested the decision, arguing it infringed his right to information access. He claimed the sites hosted lawful content and constituted vital platforms for the freedom of expression. He also challenged the constitutionality of the relevant law.[33] The Beyoğlu Criminal Court (BCC) dismissed the applicant's claim the next day (30 September), citing his lack of standing and the decision's compliance with legislation. On 5 October 2009, the applicant appealed before the Chamber of Copyright Matters of the BCC (CCBCC).

The applicant's argument centred on the disproportionate nature of the blocking measure, which affected lawful content. He contended that the law lacked clarity and precision regarding its application to Internet platforms. The CCBCC upheld the decision on 12 October 2009, emphasising the necessity of blocking to combat copyright infringement, especially given the global reach of Internet piracy. It has been noted that before requesting the blocking, MÜYAP issued warnings to the affected sites to cease the unauthorised distribution of copyrighted works. However, as the sites did not comply, the public prosecutor ordered the blocking based on expert reports submitted by MÜYAP. The chamber concluded that blocking access to sites engaged in widespread distribution of copyrighted works was the only effective means to protect copyrights, particularly given the prevalence of Internet piracy. It emphasised that since the Internet infrastructure did not allow for selective blocking of site content, a general block was necessary to protect copyrights effectively. The chamber also rejected the argument regarding the alleged unconstitutionality of additional Article 4 of the law on artistic and intellectual works.[34] The applicant challenged the decision before the ECtHR.

The Court first examined whether the applicant could claim to be a victim of a Convention violation due to the website-blocking measure. It reiterated that the notion of 'victim' under Article 34 of the Convention must be interpreted autonomously, irrespective of internal concepts such as interest or standing to act.[35] This primarily concerns those directly affected by the alleged interference. The Court has previously accepted, albeit

- 95/96 -

exceptionally, requests from individuals indirectly affected by Convention violations. However, a link between the applicant and the alleged harm resulting from the violation must exist. In this case, the Court noted that by a decision made on 26 June 2009, the media section of the Beyoğlu Public Prosecutor's Office ordered the blocking of access to the 'myspace.com' and 'last. fm' websites, citing copyright infringement. As a user of these sites, the applicant primarily complained about the collateral effect of the measure taken under the law on artistic and intellectual works. While acknowledging the importance of Internet users' rights, the Court held that the applicant's indirect exposure to the blocking of two music-sharing websites did not suffice for his recognition as a 'victim' under Article 34 of the Convention. Although he could access a variety of music through alternative means without infringing copyright rules, he did not assert that the blocked sites provided unique information of particular interest to him.[36] Furthermore, the Court distinguished this case from previous cases, such as the Yildirim case, where similar measures directly affected individuals. The Court also recalled its strict scrutiny of website blocking decisions due to their potentially significant collateral censorship effects.

Consequently, the Court concluded that the applicant could not claim to be a victim of a violation of Article 10 of the Convention due to the disputed measure. The lack of victim status under Article 10 also affected the applicant's Article 6 complaint. Therefore, the application was incompatible ratione personae with the Convention provisions and had to be dismissed under Article 35 §§ 3 and 4 of the Convention.

3. Cengiz and Others v Turkey[37]

The case concerns Turkish law professors and YouTube, the most significant video-sharing platform in the world. Similarly to the facts in the Yildirim-judgement, the Ankara Criminal Court of First Instance ordered the blocking of access to YouTube with the aim of prohibiting insults to the memory of Atatürk in ten video files on the website.[38] Cengiz and the other applicants (applicants) contested the blocking order, arguing for the right to freedom of information and emphasising the public interest in YouTube access and the disproportionate restriction on their freedom to receive information and ideas.[39] Despite these objections, the Ankara Criminal Court dismissed them, asserting that the blocking order complied with legal requirements. It maintained that while YouTube had blocked access to the files in Turkey, they remained available globally on the platform. Additionally, it has been argued that the applicants lacked standing as they were not involved in the investigation, and a

- 96/97 -

previous dismissal of similar objections was noted.[40] After unsuccessfully exhausting all domestic remedies, the applicants challenged the blocking decision before the ECtHR.

The applicants challenged the YouTube blocking, citing a breach of their freedom of information. They argued that the blanket block disproportionately restricted access to unrelated content. The government countered, asserting the legality and necessity of blocking and aligning it with EU standards. They emphasised fair legal proceedings and recent amendments to the law while acknowledging technological limitations in implementing URL filtering for foreign-based websites in Turkey. The ECtHR revisited the fundamental principle that the Convention does not allow an 'actio popularis', emphasising that individuals must demonstrate they are directly or indirectly affected by a violation attributable to a Contracting state to petition the court. Drawing on precedent cases like Yildirim, Tanrikulu and Akdeniz, the ECtHR underscored the need for a nuanced assessment of each case, considering the manner in which individuals utilise the platform and the potential impact of any measures taken.[41] In this instance, the applicants, active users of YouTube, highlighted the adverse consequences of the blocking order on their academic endeavours and the significant role of the platform in their professional lives. They stressed their active engagement on YouTube as consumers and producers of content relevant to their respective fields. This active involvement resembled the scenario in the Ahmet Yildirim case, where the applicant utilised his personal website to share academic work and views.[42]

Moreover, the ECtHR noted distinctions between these cases and previous rulings,[43] particularly regarding the nature of content hosted on YouTube. Unlike cases involving copyright infringement, YouTube serves as a vital platform not only for artistic content but also for political discourse and social activities. The availability of diverse and unique information on YouTube, which is not easily accessible elsewhere, further underscored its importance to the applicants. Acknowledging the Constitutional Court's recognition of victim status for active users of websites like YouTube, the ECtHR endorsed this perspective. It affirmed that the applicants' active engagement on the platform justified their claim to victim status, irrespective of whether the blocking order directly targeted them.[44]

Reviewing whether the interference was justified, the Court applied the known tripartite test.[45] When evaluating the 'prescribed by law' criteria, the Court acknowledged that while the blocking of a website had a legal basis in section 8(1) of Law no. 5651, concerns were raised regarding its accessibility and foreseeability. The applicants argued that the

- 97/98 -

provision lacked the necessary precision, rendering it too vague to meet the standards of foreseeability.[46] Drawing on precedent cases such as the Yildirim judgment, it noted that Turkish law did not authorise the wholesale blocking of entire websites based on the content of a single page. Instead, it permitted the blocking of specific publications under certain conditions. The absence of specific statutory authorisation for such broad measures has already been highlighted, mainly when the Ankara Criminal Court of First Instance decided to block all access to YouTube.

Moreover, the ECtHR noted the absence of URL filtering technology for foreign-based websites in Turkey, leading to the wholesale blocking of entire websites as the only practical option. This approach substantially restricted Internet users' rights and had significant collateral effects, contravening the requirements of the Convention.[47] Consequently, the Court concluded that the interference resulting from the application of the pertaining national law did not meet the standard of lawfulness under the Convention, failing to provide the applicants with the requisite protection guaranteed by the rule of law in a democratic society. Therefore, the applicants' rights under Article 10 of the ECHR had been violated.

4. Vladimir Kharitonov v Russia,[48] OOO Flavus and Others v Russia,[49] Bulgakov v Russia,[50] Engels v Russia[51]

Following Dirk Voorhoof's note, the cases mentioned above are presented jointly.[52] The cases involved various types of blocking measures, such as collateral blocking, excessive blocking and wholesale blocking of media outlets, implemented under Russia's Information Act. These measures were used to block websites and online media outlets, leading to concerns regarding their arbitrary and excessive effects. The ECtHR emphasised the crucial role of the Internet in enabling freedom of expression in all four cases. To briefly summarise, in the Kharitonov case, the applicant discovered that the IP address of his website, Electronic Publishing News, had been blocked by the Roskomnadzor telecoms regulator. This action had been taken following a decision by the Federal Drug Control Service to block access to another website, rastaman.tales.ru, which shared the same hosting company and IP address as the applicant's website. Despite the applicant's complaint to the court, highlighting that his website contained no illegal content, the courts upheld Roskomnadzor's decision as lawful without considering its effect on the applicant's website.

- 98/99 -

In the OOO Flavus case, the applicants, owners of opposition media outlets, sought judicial review of the blocking measures. OOO Flavus owns grani.ru, the second applicant, Garry Kasparov, is the founder of www.kasparov.ru, and OOO Mediafokus owns the Daily Newspaper (Ezhednevnyy Zhurnal). In March 2014, Roskomnadzor blocked access to their websites at the request of the Prosecutor General, citing the alleged promotion of mass disorder or extremist speech under section 15.3 of the Information Act. This blocking occurred without a court order. The applicants argued against the wholesale blocking of their websites and the lack of specific notice regarding the offending material, which prevented them from taking corrective action to restore access before the Taganskiy District Court and later before the Khamovnicheskiy District Court in Moscow. However, their applications were unsuccessful as both courts rejected the appeal, claiming that 'the blocking measure had had no incidence on the applicants' rights or freedoms'.[53] The applicant appealed the previous domestic decisions before the Moscow City Court which dismissed the appeal in summary fashion, affirming the previous courts' decisions, resulting in the fact that the applicants had exhausted all domestic remedies.

In the Bulgakov case, the applicant discovered that the local Internet service provider had blocked access to his website, Worldview of the Russian Civilization (sic!), based on a court judgment from April 2012, of which he had been unaware. The judgment, issued under section 10(6) of the Information Act, targeted an electronic book in the files section of the website previously categorised as an extremist publication. The court ordered the block order by instructing the provider to block access to the IP address of the applicant's website. Upon learning of the court's judgment, the applicant promptly removed the e-book. However, the courts declined to lift the blocking measure, citing that the initial court order had directed a block on access to the entire website by its IP address, not solely to the offending material.

Last, per the Engels case, a Russian court ordered the local Internet service provider to block access to the applicant's website, RosKomSvoboda, which focused on freedom of expression and privacy issues. This action was based on a complaint filed by a prosecutor, who contended that the information available on the applicant's website regarding bypassing content filters should be banned in Russia. The prosecutor argued that such information enabled users to access extremist material on another unrelated website. Notably, the applicant had not been notified of these legal proceedings. Following the court order, Roskomnadzor requested the applicant to remove the disputed content to prevent the website from being blocked. The applicant complied with this request. However, despite the applicant's argument that providing information about tools and software for browsing privacy protection did not violate any Russian law, the courts rejected his complaint without addressing this central argument.

- 99/100 -

The reason behind examining the cases together stems from the fact that all the applicants involved in the above cases claimed the violation of Article 10 of the ECHR and the lack of effective remedy (Article 13). Furthermore, in all four cases, the Court was unanimous in finding a violation of Article 10. The ECtHR emphasised the crucial role of the Internet in enabling freedom of expression and information. It found that the measures blocking access to websites constituted an interference with the applicants' rights to impart and receive information. However, these measures failed to meet the conditions required by the Convention, particularly the requirement of being 'prescribed by law'.

In the Kharitonov case, the latter's website was blocked under section 15.1 of the Information Act despite not containing any illegal material itself, but solely because it shared the same IP address as a website with illegal content. This lack of legal basis rendered the interference unlawful.

Additionally, in the cases of OOO Flavus and Others, the websites were blocked under section 15.3 of the Information Act based on vague grounds, such as calls for mass disorder or participation in unauthorised public events. The notices issued by Roskomnadzor failed to specify particular web pages, preventing the applicants from addressing the specific content in question. Moreover, the Court found no justification for the wholesale blocking of entire websites, which it deemed an extreme measure akin to banning a newspaper or television station. The Government's failure to specify legitimate aims for the blocking measures raised serious concerns, particularly regarding the potential suppression of opposition media.

In Mr. Bulgakov's case, although the e-book on his website was deemed extremist material, he promptly removed it, yet the blocking measure lacked proper legal basis and justification. Moreover, none of the remedies available to the applicants proved effective, leading to a violation of Article 13 in conjunction with Article 10 in each case.

Finally, in the Engels case, the ECtHR unanimously found violations of both Article 10 and Article 13 with regard to effective domestic remedies. The Court, in its judgment, highlighted that the existing legal framework on which the decision to block Engels' website was too vaguely formulated. In this regard, the Court underlined that due to the fact that the applicant had been 'coerced' to delete the content in question from the website, Russia had violated Engels' rights under Article 10, noting that this interference not only affected the applicant's right to impart information but conversely, the public's right to receive information as well. As for Article 13 - though domestic remedies were available and duly exhausted by the applicant - the Court accentuated once again that the proceedings lacked safeguards. The Court argued that despite the possibility of appeal, the appellate court had failed to address the substance of the grievance, rendering the remedy ineffective.

- 100/101 -

5. Wikimedia Foundation Inc. v Turkey[54]

In the Wikimedia Foundation case, once again, the Turkish regulation on Internet blocking was the focal point. Per the facts of the case, following the Government's request, the Presidency of PIT was instructed to either remove two specific pages from Wikipedia, entitled 'State-Sponsored Terrorism' and 'Foreign involvement in the Syrian Civil War' or alternatively, block the entire website if removal was not feasible.[55] On the same day, the applicant's lawyer received five emails from the PIT demanding the removal of five URL pages within a four-hour timeframe.[56] The PIT decided to block access to the entire website due to the failure to remove the specified pages within the given time limit. It had been deemed technically impractical to block only those specific pages.[57] After the exhaustion of all domestic remedies, the applicant lodged a complaint before the ECtHR.

The Government presented three main arguments against the admissibility of the applicant's complaint. First, it contended that the applicant lacked victim status as the Constitutional Court's ruling recognised the alleged violation, and the subsequent reopening of the case by the domestic court (Criminal Judgeship of Peace of Ankara, CJPA) constituted appropriate redress. Second, it asserted that the applicant had failed to exhaust domestic remedies, highlighting that the individual appeal was pending before the Constitutional Court when the application had been filed to the European Court. Last, the Government urged the Court to declare the application inadmissible due to personal and material incompatibility, suggesting that the Court should focus solely on examining judicial guarantees in the specific case rather than abstract analysis and arguing that the content of the implicated pages fell outside the scope of Article 10 protection under the Convention.[58] The applicant argued that despite the individual appeal route to the Constitutional Court (CC) theoretically providing an effective remedy, it had become ineffective in practice due to systemic issues. She contended that the CC had essentially acted as a first-instance court in examining the legality of such blocking measures, rendering the individual appeal ineffective.

Furthermore, the control exercised by CJPA raised systemic concerns as thousands of websites had been blocked without effective judicial oversight, forcing parties to resort to individual appeals before the CC for unblocking. The applicant asserted that the CC's review process was slow, often delayed until after the case was communicated by the European Court, making it a conditional recourse. Additionally, she claimed that the CC's authority was being disregarded in practice, as evidenced by continued blocking despite CC rulings finding violations in similar cases. Furthermore, the applicant highlighted the inability to

- 101/102 -

directly challenge legislation, such as Article 8/A of Law No. 5651, before the CC, further complicating the remedy process. Thus, she maintained her victim status, arguing that the CC's failure to address systemic issues left her complaints under Articles 6 and 13 unaddressed.[59]

The Court recalled that it was primarily the responsibility of national authorities to rectify Convention violations. Whether an applicant could still claim victim status depended on the situation at the time of application and on all circumstances, including any developments before the Court's examination. A decision or measure in the applicant's favour typically did not deprive them of victim status unless the authorities explicitly recognised and remedied the Convention violation. In this case, despite the Constitutional Court's finding of violation and subsequent lifting of the contested measure, the applicant contested the Government's arguments, maintaining her victim status due to the alleged systemic issue. Regarding the effectiveness of individual appeals, the Court noted its previous rulings that such appeals should be exhausted, particularly in freedom of expression cases. It found no reason to deviate from this jurisprudence, as there was insufficient evidence to suggest that an individual appeal to the Constitutional Court would not provide adequate redress. The Court observed the Constitutional Court's established jurisprudence on website blocking, noting its criteria for such measures and its previous rulings, finding them disproportionate.

Additionally, it addressed the applicant's argument regarding the inability to challenge legislation directly, highlighting that her challenge to the law's predictability could be raised in an individual appeal. While acknowledging the systemic issue raised by the applicant, the Court found no compelling evidence that the Constitutional Court could not address it. It emphasised the Constitutional Court's ability to establish guiding criteria and the potential for pilot judgment procedures to tackle systemic issues. Despite the lengthy proceedings before the Constitutional Court, the Court did not find the duration manifestly excessive, though it stressed the importance of swift judicial review in such cases. The applicant's complaint under Articles 6 and 13 was considered by the Constitutional Court under the right to freedom of expression, aligning with the Court's jurisprudence, according to which complaints are defined by the facts alleged rather than the legal arguments. Ultimately, the Court concluded that the Constitutional Court's acknowledgement of the violation and its adequate redress meant the applicant had lost victim status. Therefore, the application was deemed incompatible ratione personae with the Convention and deemed inadmissible.[60]

- 102/103 -

6. Taganrog LRO and Others v Russia[61]

The case concerned the forced dissolution of Jehovah's Witnesses religious organisations in Russia, the banning of their religious literature and international website on charges of extremism, the revocation of their permit to distribute religious magazines, the criminal prosecution of individual Jehovah's Witnesses (JW), and the confiscation of their property.[62] The jointly handled cases involving the forced dissolution of the local JW organisation, Taganrog, the banning and confiscation of religious publications in different Russian regions, the criminal prosecution of the applicants for distributing 'extremist' literature, the forced dissolution of a local JW organisations (eg Samara) and the JW Administrative centre, the withdrawal of the distribution permit and prosecution of applicants for the distribution of unregistered media and the seizure of a consignment of religious literature and in relation to RATI, the banning of access to the JW's website (jw.org) - in sum, an all-out, total attack on JW as a religion and an organisation. The latter restriction is of utmost importance, especially from a procedural perspective. In 2013, the Tsentralniy District Court in Tver (TDCiD), following an application by a prosecutor, pronounced that the website was 'extremist' as it contained digital brochures and articles concerning the studies and beliefs of the JW community. Per the facts of the case, however, the pertaining applicants, Watchtower Bible and Tract Society of New York (together: WNY), were not informed of the proceeding against them as the TDCiD held that the inclusion and the participation of WNY was unnecessary, given that they were operating an allegedly extremist website.[63] WNY, in an unorthodox manner, was informed of the proceeding via media reporting. Consequently, appeals were filed by WNY and individual JW members, arguing that they were not given a fair chance to participate in the proceedings. The TDCiD initially overturned the decision, citing procedural errors and the absence of extremist materials on the website within Russia. However, the Supreme Court of the Russian Federation reinstated the extremist designation despite objections and logistical issues faced by WNY. Subsequently, in 2015, the Ministry of Justice added 'jw.org' to the Federal List of Extremist Materials, 'cementing' its status as extremist in Russia. The WNY challenged the decision before the ECtHR.

With regard to the alleged violation of Article 10 concerning the banning of the website and deeming it extremist, the applicants highlighted procedural flaws and denial of participation. The Russian government argued that jw.org contained materials previously declared extremist by Russian courts, referencing brochures and magazines deemed as such. It asserted that the website's content posed a threat to public order and safety. Additionally, Russia claimed that the presence of extremist materials justified branding the entire website as extremist, despite the existence of non-extremist religious content and further

- 103/104 -

emphasised their authority to act against materials they deemed as extremist to protect Russian citizens from potentially harmful ideologies.

The ECtHR when assessing the case accentuated once again the pivotal role of the Internet in both freedom of expression and accessing information.[64] The Court also reiterated the findings of the OOO Flavus case, marking the dichotomy of information access as a dual right as it entails both the imparting and the receiving/accessing of information. Focusing on Article 10, the Court found that the lack of procedural safeguards in Russian law exacerbated the infringement of rights to impart and access information. The Court criticised the absence of mechanisms allowing website owners to participate in blocking proceedings or remove offensive content before enforcement. Furthermore, the Court underlined that the broad blocking of the entire website, as opposed to the targeted removal of specific allegedly unlawful content, demonstrated disregard for the distinction between legal and illegal information.[65] The Court found that such indiscriminate measures had violated the principles of necessity and proportionality. Subsequently, the Court found that the interference was not prescribed by law and was not necessary in a democratic society.

IV. Chasing a Wild Goose? - Drawing Consequences from ECtHR Case Law

Taking into account the above judgments, the following table summarises the decisions on general Internet restrictions in Turkey and Russia.

Table 2: Distribution of judgments in view of violation of Article 10 and admissibility (Source: Own editing)

| Country | Judgment | ||

| No violation of Article 10 | Violation of Article 10 | Inadmissible | |

| Turkey | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Russia | 0 | 5 | 0 |

| Σ | 0 | 7 | 2 |

The evidence per the judgments seems quite clear: Turkey and Russia have a systemic issue with the RATI. Interestingly, however, this systemic problem stems from the first part of the tripartite test,[66] namely, whether the restriction of the RATI was prescribed by law. As

- 104/105 -

seen in all seven cases where violation of Article 10 was decided, questions about legitimacy were raised about the Turkish and Russian legislation. Whether concerning the applicability or the arbitrary enforcement of the respective law, a sequential criticism emerging from the ECtHR case law findings may be examined.[67] The question can rightly be raised: Why do Turkey and Russia not amend their legislation regarding the RATI? Besides being a juridical issue, the legitimacy of the question may be substantiated by the economic factors associated with the above judgments. For instance, in the Taganrog LRO case, Russia was ordered to pay around 63.6 million USD in pecuniary and 3.7 million USD in non-pecuniary damages.

Though answers to the question may derive from societal, political or even technical standpoints, following the line of argumentation in the above segments, it can be speculated that from the perspective of a leader of a hybrid regime, the newfound freedom of communication that the Internet has created presents a dilemma as it contradicts the former's inclination to regulate the content and dissemination of information.[68] Kristin Eichhorn and Eric Linhart also stress that Internet restrictions can be a means of hindering the flow and extent of critical views about the respective regime.[69] In this context, I argue that with regard to the websites blocked in Turkey and Russia, such as social media websites and YouTube, the restrictions of the RATI not only constitute a local polemic but a global one - the marginalisation of Turkish and Russian Internet users in an ever-growing and interconnected digital sphere.

Lamentations about the future of the above marginalisation leave no room for optimism. Both scholars and journalists have noted Turkey's systemic Internet and specific website blockings. Between 2014 and 2018, a total of 245,000 websites were banned in Turkey,[70] including the likes of Wikipedia and Facebook, leaving users of these sites two options: to either leave behind these online spheres or use VPNs to access them. Turkey has also recently passed the so-called 'censorship law' on online reporting, criticised by Article 19 and Human Rights Watch, two renowned NGOs specialised in human rights and freedom of expression, for its 'draconian' sanctions for disseminating critical views online, such as criminal penalties and, potentially, prison sentences.[71] Istanbul-based civil society,

- 105/106 -

Alternatif Bilişim Derneği (Alternative Informatics Association) also drew attention to systemic Internet throttling that has been implemented during emergency situations such as major earthquakes when, curiously, access to the most popular social media platforms such as TikTok and Twitter were mysteriously and without any explanation, shut down for 10 hours.[72] Seemingly, nothing seems to be changing either. Deutsche Welle reported that before the local elections, the Turkish government was censoring websites (around 712,000 in 2022 alone) and VPN services, too, leaving absolutely no room for citizens to access information.[73] In this regard, President Erdoğan saying 'We will defeat the opposition in all their strongholds' sustains both the worry and the hopelessness of those who argue that the RATI should be regarded as a human right.[74]

The situation in Russia proves to be even worse; Dasha Litvinova calls the Russian measures regarding the Internet a process of creating a cyber gulag, a digital environment where the country tracks, censors and controls its citizens.[75] In this regard, reports also suggest that Russian authorities have taken a systemic approach to blocking access to the Internet: shutting down nearly all VPN programs, limiting messaging apps and restricting access to global news sites and social media sites, such as Instagram.[76] In contrast to Turkey, however, Russian citizens have even less international legal protection. As announced in late 2022, Russia ceased to be a party to the ECHR six months after its exclusion from the Council of Europe.[77] This means that Russian citizens who are not satisfied with the decisions of local courts no longer have any international legal remedies for challenging domestic decisions.

V. Conclusions

The persistent violations of Article 10 of the ECHR underscore systemic issues with Turkey and Russia's legislative frameworks. Despite international scrutiny, both governments show little willingness to amend restrictive Internet laws, driven by economic, legal, and political

- 106/107 -

factors. These restrictions extend beyond borders, stifling global discourse and connectivity while marginalising Internet users and suppressing dissent. With escalating measures and diminishing legal protections, the future of digital rights in Turkey and Russia appears grim. Citizens face heightened surveillance and censorship, necessitating advocacy, solidarity and international intervention. Civil society, human rights organisations and the global community must support Internet users in both countries, affirming the right to access the Internet as vital for democracy, freedom of expression and global connectivity in the digital era. The present paper aimed to analyse ECtHR case law, draw conclusions about the future of the RATI in two hybrid regimes and add to the scholarly literature on freedom of expression in autocracies. ■

NOTES

[1] Merten Gerlitz, 'The Human Right to Free Internet Access' (2019) 37 (2) Journal of Applied Philosophy 314, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/japp.12395

[2] Gergely Gosztonyi, Censorship from Plato to Social Media. The Complexity of Social Media's Content Regulation and Moderation Practices (Springer 2023, Cham) 147-168, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-46529-1_10

[3] Gergely Ferenc Lendvai, 'Media in War: An Overview of the European Restrictions on Russian Media' (2023) 3 (3) European Papers, DOI: https://doi.org/10.15166/2499-8249/715

[4] Ole Frahm and Katharina Hoffmann, 'Dual Agent of Transition: How Turkey Perpetuates and Challenges Neo-Patrimonial Patterns in Its Post-Soviet Neighbourhood' (2020) 37 (1) East European Politics 110, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/21599165.2020.1733982

[5] Cengiz and Others v Turkey, nos. 48226/10, 14027/11, ECHR, 1 December 2015.

[6] Vladimir Kharitonov v Russia, no. 10795/14, ECHR, 23 June 2020.

[7] Richard Ashby Wilson, 'The Anti-Human Rights Machine: Digital Authoritarianism and The Global Assault on Human Rights' (2022) UCONN Faculty Articles and Papers 614.

[8] Larry Diamond, 'Thinking About Hybrid Regimes' (2002) 13 (2) Journal of Democracy 21, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2002.0025

[9] Petra Bárd, Laurent Pech, 'How to Build and Consolidate a Partly Free Pseudo Democracy by Constitutional Means in Three Steps: The 'Hungarian Model' Reconnect Europe Working Paper 2019/4, DOI: https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3608784

[10] T. F. Rhoden, 'The liberal in liberal democracy' (2013) 22 (3) Democratization 3, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2013.851672

[11] Terry Lynn Karl, 'The Hybrid Regimes for Central America' (1995) 6 (3) Journal of Democracy 72-87, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.1995.0049

[12] Ali Riaz, Voting in a Hybrid Regime (Springer 2019, Cham) 14, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-7956-7

[13] Muntasser Majeed Hameed, 'Hybrid Regimes: An Overview' (2022) 22 (1) IPRI Journal 5, DOI: https://doi.org/10.31945/iprij.220101

[14] Leonardo Morlino, 'Are There Hybrid Regimes? Or Are They Just an Optical Illusion?' (2009) 1 (2) European Political Science Review 273, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/s1755773909000198

[15] Henry E Hale, 'Eurasian Polities as Hybrid Regimes: The Case of Putin's Russia' (2010) 1 (1) Journal of Eurasian Studies 33, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.euras.2009.11.001

[16] Joakim Ekman, 'Political Participation and Regime Stability: A Framework for Analyzing Hybrid Regimes' (2009) 30 (1) International Political Science Review 7, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0192512108097054

[17] Luke March, 'Managing Opposition in a Hybrid Regime: Just Russia and Parastatal Opposition' (2009) 68 (3) Slavic Review 504, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/s0037677900019707

[18] J Paul Goode, 'Redefining Russia: Hybrid Regimes, Fieldwork, and Russian Politics' (2010) 8 (4) Perspectives on Politics 1055, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/s153759271000318x

[19] Nate Schenkkan and Aykut Garipoglu, 'Turkey Elections 2023: How Erdogan and the AKP Could Rig the Vote' (May 16, 2023) Foreign Policy, <https://foreignpolicy.com/2023/05/03/turkey-elections-erdogan-ldlicdaroglu-vote-manipulation-suppression-media/> accessed 15 October 2024.

[20] Nikolaos Stelgias, 'Turkey's Hybrid Competitive Authoritarian Regime; A Genuine Product of Anatolia's Middle Class' (2015) 4 (2) The Levantine Review 2, DOI: https://doi.org/10.6017/lev.v4i2.9161

[21] Gergely Ferenc Lendvai, Gergely Gosztonyi, 'Access Denied - interpreting the digital divide by examining the right of prisoners to access the Internet in the case law of the European Court of Human Rights' (2024) 17 (1) Baltic Journal of Law & Politics 223-237, DOI: https://doi.org/10.2478/bjlp-2024-0011

[22] Ahmet Yildirim v Turkey, no. 3111/10, 18 December 2012 ECHR.

[23] Ahmet Yildirim v Turkey § 7.

[24] Ahmet Yildirim v Turkey § 8.

[25] Ahmet Yildirim v Turkey § 9.

[26] Ahmet Yildirim v Turkey § 10.

[27] Ahmet Yildirim v Turkey § 14.

[28] Ahmet Yildirim v Turkey §§ 46-47.

[29] cf Times Newspapers Ltd v the United Kingdom (dec.), nos. 3002/03 et 23676/03, ECHR 2009, § 27.

[30] Ahmet Yildirim v Turkey § 49.

[31] Akdeniz v Turkey (dec.), nos. 41139/15, 41146/15, ECHR 2021-II.

[32] Akdeniz v Turkey §§ 2-3.

[33] Akdeniz v Turkey § 5.

[34] Akdeniz v Turkey § 8.

[35] Akdeniz v Turkey § 19.

[36] Akdeniz v Turkey § 22.

[37] Cengiz v Turkey (dec.), no. 48226/10 and 14027/11, ECHR 2015.

[38] Cengiz v Turkey § 7.

[39] Cengiz v Turkey § 8.

[40] Cengiz v Turkey § 10.

[41] Cengiz v Turkey § 48-49.

[42] Elena Lazăr and Nicolae-Dragoş Costescu, 'Romania' in Oreste Pollicino (ed), Freedom of Speech and the Regulation of Fake News (Intersentia 2023, Cambridge) 431-437.

[43] cf Akdeniz v Turkey.

[44] Cengiz v Turkey §§ 54-55.

[45] Janneke Gerards, 'How to improve the necessity test of the European Court of Human Rights' (2013) 11 (2) International Journal of Constitutional Law 11.

[46] Cengiz v Turkey §§ 60-62.

[47] Cengiz v Turkey § 64.

[48] Vladimir Kharitonov v Russia (dec.), no. 10795/14, ECHR 2020.

[49] OOO Flavus and Others v Russia (dec.), nos. 12468/15, 23489/15, 19074/16, ECHR 2020.

[50] Bulgakov v Russia (dec.), no. 20159/15, ECHR 2020.

[51] Engels v Russia (dec.), no. 61919/16, ECHR 2020.

[52] Dirk Voorhoof, 'ECtHR: Vladimir Kharitonov v Russia, OOO Flavus and Others v Russia, Bulgakov v Russia, Engels v Russia' (2020) 1 IRIS 8.

[53] OOO Flavus and Others v Russia § 9.

[54] Wikimedia Foundation Inc. v Turkey, no. 25479/19, ECHR 2022.

[55] Wikimedia Foundation Inc. v Turkey § 3.

[56] Wikimedia Foundation Inc. v Turkey § 4.

[57] Wikimedia Foundation Inc. v Turkey § 5.

[58] Wikimedia Foundation Inc. v Turkey § 20.

[59] Wikimedia Foundation Inc. v Turkey §§ 21-26.

[60] Wikimedia Foundation Inc. v Turkey §§ 50-51.

[61] Taganrog LRO and others v Russia, nos. 32401/10 and 19 others, ECHR 2022.

[62] Taganrog LRO and others v Russia § 1.

[63] Taganrog LRO and others v Russia § 80.

[64] Ahmet Yildirim v Turkey §§ 48-54.

[65] Taganrog LRO and others v Russia § 232.

[66] Gehan Gunatilleke, 'Justifying Limitations on the Freedom of Expression' (2020) 22 Human Rights Review 91, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s12142-020-00608-8

[67] Gergely Gosztonyi, 'The European Court of Human Rights: Internet access as a means of receiving and imparting information and ideas' (2020) 6 (2) International Comparative Jurisprudence, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.13165/j.icj.2020.12.003

[68] Christian Göbel, 'The Information Dilemma: How ICT Strengthen or Weaken Authoritarian Rule' (2013) 115 (4) Statsvetenskaplig Tidskrift 115.

[69] Kristin Eichhorn and Eric Linhart, 'Election-Related Internet-Shutdowns in Autocracies and Hybrid Regimes' (2022) 33 (4) Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties 705, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17457289.2022.2090950

[70] Luke Edwards and Chiara Castro, 'What Websites and Online Services Are Blocked in Turkey - Facebook, Wikipedia and More' (2022) Techradar <https://www.techradar.com/vpn/websites-online-services-blocked-turkey-facebook-wikipedia> accessed 15 October 2024.

[71] Human Rights Watch, 'Turkey: Dangerous, Dystopian New Legal Amendments' (2022) <https://www.hrw.org/news/2022/10/14/turkey-dangerous-dystopian-new-legal-amendments> accessed 15 October 2024.

[72] EDRI, 'Internet Restrictions in Turkey - European Digital Rights (EDRi)' (2023) <https://edri.org/our-work/internet-restrictions-in-turkey-violate-fundamental-rights/> accessed 15 October 2024.

[73] Elmas Topcu, 'Turkey: Internet Censorship before Local Elections' (2024) <https://www.dw.com/en/turkeys-internet-censorship-escalates-before-local-elections/a-68066987> accessed 15 October 2024.

[74] Topcu (n 73).

[75] Dasha Litvinova, 'The Cyber Gulag: How Russia Tracks, Censors and Controls Its Citizens' (2023) APNews <https://apnews.com/article/russia-crackdown-surveillance-censorship-war-ukraine-internet-dab3663774feb666d6d0025bcd082fba> accessed 15 October 2024.

[76] Adam Satariano, Paul Mozur and Aaron Krolik, 'Russia Strengthens Its Internet Controls in Critical Year for Putin' (2024) The New York Times <https://www.nytimes.com/2024/03/15/technology/russia-internet-censors-vladimir-putin.html> accessed 15 October 2024.

[77] Thomas Giegerich, 'Struggling for Europe's Soul: The Council of Europe and the European Convention on Human Rights Counter Russia's Aggression against Ukraine' (2022) 25 (3) Zeitschrift für Europarechtliche Studien, DOI: https://doi.org/10.5771/1435-439x-2022-3-519

Lábjegyzetek:

[1] The author is PhD Candidate, Pázmány Péter Catholic University and Research Fellow at the University of Richmond. This paper was supported by the Rosztoczy Foundation Scholarship, the project 149657_ADVANCED_24 provided by the Ministry of Culture and Innovation of Hungary from the National Research, Development and Innovation Fund and the Hungarian Hungarian State Eötvös Scholarship. https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3298-8087.