Tamás Kende[1] - János Katona[2]: In the Crystal Ball - Outside the EU and What the UK will Find There (ELTE Law, 2016/1., 73-92. o.)

On June 23 2016 the people of the United Kingdom voted - in a legally non-binding but politically imperative referendum - for the UK to discontinue membership of the European Union.

David Cameron, the British Prime Minister, had promised in 2013 a referendum on the United Kingdom's EU membership before the end of 2017. In 2016, his government negotiated a series of EU reforms with the other member-states with special provisions for the UK. The result of the referendum of June 23 2016 was in favour of the withdrawal of the UK from the European Union, notwithstanding the outcome of those negotiations.

While the reasons for the decision of the British electorate are not entirely clear and probably cannot be narrowed down to a single factor, it appears likely that the majority specifically rejected the free movement of workers, a key component of the single market. Based on statistics from 2014, there were only 2.9 million EU nationals in Britain. That is no more than 5% of the UK's population yet the Leave campaign succeeded in convincing a sizeable part of the electorate about the tenability of immigration.

Writing the day after the result was announced, the leader column of The Irish Times stated that the electorate had fallen for an 'easily sold, demagogic delusion'.[1] All elections are thus to some degree. But promises made in a general election generally have to be delivered on, or the promisor gets punished at the subsequent elections. In the case of a referendum, it is more complicated to come back for those who made those promises. Yet, the fact is that news is leaking about Brexit being a bad deal for the UK: the UK's office for budget responsibility predicted Brexit would blow a €70 billion hole in the nation's finances and the Institute for Fiscal Studies said Brexit would see real wages lower in 2021 than they had been in 2008.

Following the referendum, Prime Minister David Cameron resigned and a new Prime Minister, Theresa May was named and the entire cabinet reshuffled. Prime Minister May has not yet submitted to the EU the UK's decision to withdraw from the EU. In October 2016,

- 73/74 -

however, she indicated that such a decision would be submitted in March 2017. She also launched the slogan 'Brexit means 'Brexit, which is likely to mean that the UK will exit the EU regardless of the results of the negotiations with the other 27 member states and regardless of the potential economic consequences.[2] As such, the slogan seems to indicate that she will not submit the results of the negotiations for approval to by the Houses Parliament or by referendum. Although up until recently, the PM declined 'to give parliament a formal vote on the decision to trigger the Brexit process or any deal she achieves, saying it is the government's prerogative',[3] the situation may possibly be altered by the recent ruling of the High Court (if it will be sustained by the Supreme Court.). The High Court held in its decision dated November 3[th] 2016 that the Government does not have the authority (stemming from the Royal Prerogative) for a notification sent under Article 50 of the TEU relating to the withdrawal from membership (see below). The question shall be decided soon on appeal and its outcome may have an effect of the internal constitutional and, consequently, political setup if it requires the Parliament to formally decide on the notification.

In this paper, in the first part we shall briefly review the withdrawal of the UK from the perspective of the EU Treaties, then move on to present the objectives the UK may seek to achieve by the withdrawal from the EU as it has been expressed during the Brexit campaign or since then. We then examine several possible options available for the UK and the EU to regulate their cooperation. Finally, we shall finish with a quick analysis of these options mainly from the aspect of their feasibility and political expedience.

I. Brexit: The Unprecedented Withdrawal from the EU from the Perspective of the Treaties

Withdrawal from the EU is unprecedented, as no member state has until now withdrawn from the integration process. Some bulwarks of the neo-functionalist academic literature claimed that member states were locked in the integration process and so turning back was not a feasible option, politically or economically.[4] Before the Lisbon Treaty there was no formal procedure for a withdrawal and, therefore, the Vienna Convention of the law of Treaties would have applied. However, since the entry into force of Lisbon, Article 50 of the TEU regulates the withdrawal procedure.

When the UK submits its decision to withdraw from the EU, it needs to refer to and its declaration needs to be based on Article 50. This Article provides a legal basis and the procedure to be followed in the event of withdrawal. The relevant parts of the Article state:

- 74/75 -

1. Any Member State may decide to withdraw from the Union in accordance with its own constitutional requirements.

2. A Member State which decides to withdraw shall notify the European Council of its intention. In the light of the guidelines provided by the European Council, the Union shall negotiate and conclude an agreement with that State, setting out the arrangements for its withdrawal, taking account of the framework for its future relationship with the Union. That agreement shall be negotiated in accordance with Article 218(3) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union. It shall be concluded on behalf of the Union by the Council, acting by a qualified majority, after obtaining the consent of the European Parliament.

3. The Treaties shall cease to apply to the State in question from the date of entry into force of the withdrawal agreement or, failing that, two years after the notification referred to in paragraph 2, unless the European Council, in agreement with the Member State concerned, unanimously decides to extend this period.

4. For the purposes of paragraphs 2 and 3, the member of the European Council or of the Council representing the withdrawing Member State shall not participate in the discussions of the European Council or Council or in decisions concerning it.

5. ...[5]

Paragraph 2 provides for a procedure which allows the negotiation of a withdrawal treaty (WT).

The notice for withdrawal is a trigger event that inevitably leads to either the conclusion of a withdrawal treaty followed by the withdrawal or to the withdrawal without a treaty.[6]

During the negotiations on 'Brexit', the UK would remain a member-state and continue to participate in EU activities with the exception provided for in Article 50(4).[7] This exception logically provides that the UK's representative in the European Council and the Council - as well as the bodies preparing for the meetings of these bodies, such as the Permanent Representatives Committee (COREPER) - will not participate on the EU side in negotiations with the UK on Brexit.

- 75/76 -

Interestingly, although the EU has been created by an international treaty between its prospective member states, a withdrawal will not be concluded with all other member-states and, therefore, it would not require ratification by all. It will be concluded by the UK and the EU's institutions. The Council would approve it on behalf of the Union, 'acting by a qualified majority, after obtaining the consent of the European Parliament'.

On the other hand, the withdrawal will require a revision of the EU treaties, to be based on Article 48 TEU, requiring the agreement of all the remaining member states.

Given the complexities of such a withdrawal and the many alternatives which need to be taken into account, it is very likely that the two years allowed for negotiating withdrawal will not be sufficient. In such a case, Article 50(3) allows for an extension of that period, subject to the agreement of the UK and to a unanimous decision of the European Council. If negotiations between the UK and the EU on Brexit are not concluded before the two year deadline, the UK would exit the EU without a treaty and thereafter it would be forced to negotiate and conclude an agreement like any other third party. The conclusion of this agreement negotiated after the two year period would be subject to unanimity in the Council [Article 218(8) of the TFEU].

This is why the UK has not yet - at the time of writing this paper - notified the European Council of its intention to withdraw from the EU, although the new Prime Minister May has clearly indicated that the decision of the referendum will be followed ('Brexit is Brexit'). The UK is apparently trying to extend the two year deadline by not notifying its intention to withdraw until the UK administration has in its own opinion fully prepared for the withdrawal. This - as is suggested in the press - is not likely to be before the first half of 2017 so Brexit is likely to take place at some point in 2019.

The agenda and the precise subject of the Brexit negotiations are further blurred by the fact that no public agenda exists as to the strategy of the UK government relating to the negotiations. The UK government - partly led by Brexiteer politicians - seems to underestimate the difficulty of the negotiations lying ahead and the economic risks associated with it, and is playing up the potential economic benefits of the UK being on its own. Prime Minister May has recently suggested that the UK would be open to conclude a transitional arrangement with the EU in order to avoid the uncertainties that could occur before the complex task of establishing the post-Brexit relations with EU and third countries are finalized.[8] However, unintentional revelations from the UK Ministry preparing the Brexit seems to suggest that the UK is not keen on a transitional arrangement.[9]

- 76/77 -

II. What does the UK Wish to Achieve with the Withdrawal from the EU?

The obvious UK priority is to obtain as much access as possible to the EU's internal market (actually, for the most part, the EEA's market). In other areas of EU policy, some transitional measures would be appropriate. This is because the economies of the UK and the rest of the EU, after more than 40 years of membership, have become closely intertwined and interdependent. This is also because, as EU citizens, about two million British people live, work or are retired in other EU member-states, while some two and a half million other EU citizens live in the UK. All this makes it clear that the UK would have no interest in waiting to negotiate an agreement until after it had formally withdrawn from the EU. It would have a strong interest in negotiating speedily while still a member, and thus being able to benefit from Article 50 TEU special procedure.

While the 'Leave' campaign had a fairly coherent set of campaign slogans as to why the UK would need to leave the EU, the UK government has not, until the time of writing this paper, penned a coherent policy document on the aims of the UK with its withdrawal. If the UK government was to internalise in full the campaign arguments and promises of the 'Leave' campaign then of its commitments to a fully sovereign UK, with no unconditional immigration from the EU, with the rights of UK banks preserved, with more flexibility in trade negotiations and with substantially less payment by the UK into the EU budget emerge.

For these promises to materialise, it seems the UK would look for a withdrawal treaty with the EU in which the free movement of persons would be curtailed but the freedom of movement of goods, capital and services would not. Goods would move freely while there would not be a common external trade policy. In this set of promises, the UK's legislation would remain fully coherent with the EU rules in order for the remaining three freedoms to work seamlessly, although the UK parliament would be free to pass any legislation it, as a sovereign decision maker, wishes to pass. Fulfilling these promises would mean that the UK government has been able to calm the electorate and minimize the negative economic impact of Brexit on the UK economy by keeping the UK and within it the City of London - on its terms - in the single market as far as goods, services and capital are concerned. This solution is a form of 'soft Brexit' as the term was coined - a solution which allows the UK to exit the EU but leaves its economy firmly anchored in its single market - but not the only form of 'soft Brexit' imaginable.

In order to achieve this maximalist set of contradictory aims (access to the single market, no free movement, no contribution to the EU budget, no oversight by the Luxembourg Court), the UK would need to undertake a Herculean negotiating task, as some of these aims mutually exclude each other or, with regard to some of these aims, the EU's current leaders exclude making these concessions.

Probably this recognition and pressure from inside the government from British business circles lead Prime Minister May to stress in October 2016 that Britain would prioritise the control of immigration over anything else and therefore it is ready to withdraw from the EU without an agreement and fall back on the terms which the WTO agreement proposes, a withdrawal that is called 'hard Brexit' by the newspapers A hard Brexit is any form of

- 77/78 -

withdrawal from the EU by the UK in which the UK leaves the single market and, therefore, its economy and primarily its services sectors is open to losses. Donald Tusk is of the opinion that a soft Brexit does not exist and a soft-hard dichotomy is a fallacy. He tweeted, following a conference by the European Policy Centre on October 13 2016,[10] that '...the only real alternative to a "hard Brexit" is "no Brexit". Even if today hardly anyone believes in such a possibility.'[11]

Anyway, it is too early to say whether some or all of the campaign promises or the promises made by the Prime Minister in the autumn of 2016 will make it into the policy brief that will determine the negotiating position of the UK. it is not by chance that the UK itself is likely to want to leave - as we now know - by the end of March 2017 to give it time to devise its negotiating positions and submit its withdrawal.

III. Options for a Withdrawal

As outlined above, a withdrawal could take several forms of the options covered in this paper. These options can be positioned next to one another on an imaginary 'soft Brexit-hard Brexit' axis, mainly by taking into account the EU policies in which that the UK probably wishes to continue to participate, and the institutional consequences of such participation. As discussed widely in public by the academic community and in the press, the available options include solutions such as the 'Norwegian model', the 'swiss model', the 'Turkish model', a free trade agreement (FTA) or trade governed by WTO rules or an à la carte relationship with the EU.

The implementation of these options - except for 'relationship à la carte' - are either based on existing international instruments or on examples that are already present in the external economic relations of the EU (as their names show). The 'Norwegian model' requires EFTA and EEA, while other solutions may be based on the existing free trade agreements of the EU and its Member states, or the ones that are currently being negotiated. A Turkish model is an 'association' type agreement, creating a customs union and, finally, the so-called 'a la carte relationship' is based on a relatively new set of standards of cooperation between the EU and a third state.

Another aspect is that, apart from the conclusion of a WT, most of the options require that the UK enters into further international arrangements, either with the EU only and/or its member states and/or with certain other states, such as the EFTA and the EAA states. It is only the 'hardest' Brexit that is based on the provisions of the existing multilateral framework of international trade, i.e. the WTO, even though it is unclear whether the 're-accession' of the UK to the WTO would be a simple technical issue or a result of complex negotiations.[12]

- 78/79 -

In this section, we shall review the various options the UK faces concerning the next steps following its withdrawal from the EU.

1. The Norwegian Model

The Norwegian model is the 'softest' Brexit of all the existing options - provided that the 'no Brexit at all' case is left out from the available possibilities and - consequently - the one that keeps the deepest level of economic integration between the EU and the UK.

The implementation of the Norwegian model would require the accession of the UK to the EAA. This necessitates the approval of the parties to the EAA, namely the EU, its member states and other parties to the EAA, Liechtenstein, Iceland and Norway. The current setup of the EAA also presupposes that the 're-accession' of the UK to the EFTA, which it left upon its accession to the EC back in 1973, would require, in addition, the approval of Switzerland.

An EAA-based integration would bring together the EU Member States, the three EEA States and the UK in a single market, ensuring all the four freedoms of the EU, that is the free movement of goods, persons, capital and the freedom of establishment. It would not include, however, the common trade, agricultural and fishery policy, does not create a customs union and shall not extend to monetary union. Naturally, it covers neither the CFSP nor justice and home affairs.

From an institutional point of view, as a Member of the EAA, the UK would be subject to the EAA institutions, including the EAA Court, when implementing (or failing to implement) the relevant EU-originated legislation. That is comparable to the control exercised by the Court of Justice over the acts of the UK as an EU member state. More importantly, in the areas covered by the EAA single market rules, the UK (with other EFTA members) would be more or less left out of the law-making process, which is a situation much less disadvantageous than that of an EU member state.

A further discouraging factor is that, even though the EAA has functioned for more than 20 years since 1994, neither the EU nor the EFTA parties seem entirely satisfied with it. The Council has recently expressed its discontent with implementation of the relevant EU legislation within the EAA and called for actively working towards a sustainable and streamlined incorporation and application of EEA-relevant legislation.[13] The EFTA parties, in turn, complain that the EU does not sufficiently take their interests and their constitutional problems into account.[14] This is adequately illustrated by various quotes from Norwegian politicians such as

- 79/80 -

the EU spokesman for the Norwegian Conservative Party, Nikolai Astrup: 'If you want to run the EU, stay in the EU. If you want to be run by the EU, feel free to join us in the EEA'[15]. For the sake of completeness, it worth adding that these ideas are not shared unanimously: some commentators highlight that EFTA parties do have effective ways to influence EAA relevant legislation and they are able to achieve meaningful exemptions from EU legislation applicable in the EAA territory.[16]

Be that as it may, the above characteristics of the Norwegian model hardly fit into the political requirements relating to the future status of the UK as expressed by the majority of Brexiteers. First and foremost, a strict limitation and control of migration of EU workers, which was part of the main focus of the Brexit campaign, is not compatible with the EAA. Similarly, the 'outside' legal control exercised by the EEA Surveillance Authority and the EAA Court over the UK in the EAA context seems not to correspond to the 'restoration' of UK sovereignty sought by the supporters of Brexit either. Also, based on the example of Norway, EAA parties are bound to contribute to the EU via the EAA funds that could represent a burden at least comparable to the current contribution of the UK to the EU.[17]

The Norwegian option is not necessarily capable of ensuring the economic advantages that its protagonists expect. For example, the lack of a customs union and the corresponding reestablishment of the customs borders could significantly hinder the operation of the free movement of goods (by increasing the costs of the enterprises) when compared to the current situation. Another structural problem with the EAA is that the current advantages enjoyed by the UK in the EU single market are only replicated in the EAA if they are duly introduced by all EAA members. Taking into account the important backlog of implementation that exists today, EAA-based market access for UK producers could be significantly limited when compared to the current situation.[18]

Although the relatively 'deep' continued integration of the UK into the EU, seemingly implied by the Norwegian model, might seem appealing to those willing to mitigate the effects of the Brexit and/or to maintain close integration, it does not correspond to the political cornerstones placed by the Brexit campaign and may also be disappointing from the perspective of preserving the economic advantages of integration.

- 80/81 -

2. The Swiss Model

The UK could structure a withdrawal treaty in order to implement a solution similar to the Swiss model of relations with the EU.

The relationship between Switzerland and the EU may have seemed promising to Brexiteers because it is largely based on classic international law; the framework is constituted by over a hundred sectoral international agreements (which will clearly not be the case between the EU and the UK.). EU-swiss relations are somewhat looser than those the EU has with EEA members, in the sense that Switzerland is also not legally bound by judgments of the European Court of Justice and there is no court overseeing EU-Swiss relations while the EEA EFTA disputes are decided by an EFTA Court.

Yet, in reality Switzerland has to catch up with EU regulations and directives and has to incorporate those into its domestic legal order and de facto has to follow their interpretation by the ECJ in order to access the EU single market of goods. Moreover, the Swiss sectoral agreements with the EU do not cover services in general and financial services in particular. There is only an odd agreement on life insurance applicable in this sector. in that sense, the Swiss model cannot serve as an example for the UK as a substantial part of British trade is in services and Switzerland also has to contribute financially to the EU budget.

Moreover, it will be difficult to pursue the Swiss model as a model for the UK because the EU is dissatisfied with the state of its relationship with Switzerland and wants to reform it. In December 2010, the EU's Council of Ministers described these relations as 'not ensuring the necessary homogeneity', and causing 'legal uncertainty'. it added that this system 'has become complex and unwieldy to manage and has clearly reached its limits'.[19] In December 2012, the Council reaffirmed that 'further steps are necessary in order to ensure the homogeneous interpretation and application of the internal Market rules', and that it would seek a 'legally binding mechanism' to make Switzerland sign up to revised laws, as well as 'international mechanisms for surveillance and judicial control'.[20]

Then, in February 2014, the Swiss people, based on a legally-binding initiative, decided in a referendum that some form of quotas be placed on immigration from the EU.[21] Switzerland has until February 2017 to implement the results of the 2014 referendum. Based on the results of the referendum, the Swiss government announced that it would not allow free movement of persons with Croatia. Introducing such curbs as required by the referendum and the Swiss government's own initiative would contravene the EU's principle of free movement of people, to which Switzerland must adhere.

- 81/82 -

The EU rejected that move. It also rejected a subsequent proposal that Switzerland should be able to impose quantitative limits on a surge of immigrants from EU countries.[22]

The dispute over the free movement of persons led the EU to review the entire legal framework of bilateral agreements with Switzerland, and the Council of Ministers decided, in May 2014, to mandate the Commission to launch negotiations with Switzerland on 'an international agreement on an institutional framework governing bilateral relations with the Swiss Confederation'.[23]

If concluded, such a new agreement would impose much stricter legal obligations related to the internal market on Switzerland than those of the EEA EFTA members. If the Council mandate is implemented, then

- the European Commission would monitor Switzerland's application of the bilateral agreements,

- the Commission would be given 'investigatory and decision-making powers' similar to those over member-states when policing the single market,

- there would be a maximum time limit for Switzerland to implement EU laws, when they are updated,

- the ECJ should have jurisdiction, and either the EU or Switzerland should be able to take cases to the court 'without the other party's prior consent'.

While these negotiations are continuing[24] and it is not clear what sort of agreement will be hammered out, it seems evident that the Swiss-model is not promising for the UK, in the sense that the agreement as it is now may be past its prime and it is highly unlikely that the EU would be amenable to conclude a Swiss-model agreement with the UK whilst it is in the process of fundamentally reforming that agreement with Switzerland and wishes to take out all those elements which may have seemed attractive for the Brexiteers when they brought up the Swiss model in the first place.

To sum up, the Swiss model is likely to be unsuitable for the British government as a template for negotiations as

- it would provide a partially hard Brexit, as it does not cover services in general and financial services in particular,

- the Swiss model involves the free movement of EU citizens without a limit,

- following the Swiss model would involve contributions by the UK to the EU budget,

- the EU is unlikely to accept a new adherent to the Swiss model while it is in the process of fundamentally renegotiating the archetype of this model.

- 82/83 -

3. The Turkish Model

Some Brexiteers during the referendum campaign mentioned the EU-Turkey association agreement[25] that includes a customs union as a desirable fall-back for Britain.

If the UK entered into a Turkish type customs union with the EU, it would not be free to adopt its own tariffs, because it would have to follow decisions on tariffs made by the EU. If the UK and the EU were to agree jointly on the common external tariffs, this would no longer be the Turkish-model.

Besides, the Turkish model does not give Turkey full access to the EU's internal market, as it covers neither services nor the free movement of individuals, just the free movement of goods and even this at a price. Under the EU-Turkey association agreement, Turkey accepts the EU's acquis communautaire, including regarding competition policy.

In our view, under this model, the UK would not benefit from the free trade agreements (FTA) the EU concluded or concludes. It was mentioned by several Turkish commentators that, following the conclusion of the EU FTA with the Republic of Korea, Turkish exporters have not gained access to the Korean market, while Korean exporters have access to the Turkish market. Also, if the EU-US trade deal is agreed and the UK settled on the Turkish model, American companies would have access to the UK market while the UK would not have access to US markets.

To sum up, the Turkish model is also likely to be unsuitable for the British government as a template for negotiations, as it does not cover services in general and financial services in particular, would curtail UK sovereignty on trade policy and requires a partial acceptance of EU jurisdiction. Nevertheless, it could be an attractive solution in the sense that it does not involve the free movement of people and does not require a contribution to the EU budget.

4. Free Trade Agreement with the EU

Another option available is an FTA with the EU and, in the likely scenario that this would result in a mixed agreement, its member states. This option is sufficiently flexible, as the treaty practice of the EU in this field is changing. This flexibility however, means that it is difficult to identify the main elements of a model contained in an FTA.

The existing agreement include various forms of agreement named, among others, as association, stabilisation, free trade or partnership and cooperation agreements with countries all over the world including in particular Europe, the Mediterranean but also other African and South American states. Association and free trade agreements provide at least for the reduction or abolition of custom tariffs and quotas in certain or most sectors of the economy, while some cooperation agreements leave these barriers to trade unchanged. The cooperation under some these agreements may serve as a means for strengthening economic integration while collaboration remains limited with other countries.

- 83/84 -

Some recent free trade agreements however - that have not yet entered into force, some of them not even signed, - intend to create the framework for a free trade area with only a limited number of reserved sectors. These agreements also extend to areas going beyond free trade and contain important provisions relating to market access, harmonisation of economic regulations etc. The CETA with Canada or the dubious TTIP, and to lesser extent, the free trade agreement with Singapore (EUSTA) and Vietnam are the examples of the evolution of the EU's free trade agreements.

It is undoubted that the weight of the UK in the world economy and its relationship with the EU would call for a free trade or partnership agreement like the CETA or the TTIP. Technically, the parties to an FTA are allowed to agree flexibly on what they deem important. Under such an agreement, it would be possible to ensure a free trade area in the trade of goods and even to various sectors of services, and it would be possible to achieve harmonisation of market regulation (which as a starting point, exists in the EU-UK relationship). On the other hand, an important obstacle to overcome is the complexity of such negotiations. Both the CETA and the TTIP in particular illustrate these difficulties. It is therefore unlikely that a meaningful FTA could be achieved within a reasonable deadline.

5. The UK Falls Back on WTO Rules

It was recently floated that if the UK cannot agree with the EU on some other form of ongoing trade cooperation, it could simply fall back on WTO rules, which set limits on the maximum tariffs that countries can apply to trade in goods. This solution was even mentioned as desirable from the Brexiteers' point of view. The apparent advantage of this solution would be that it would not involve contributions by the UK to the EU budget and would allow the UK to completely free itself from the jurisdiction of the Luxembourg court.

It seems though that it is here that any advantages stop. This would be one of the hardest forms of Brexit, as it would not provide for the free movement of goods, services, capital or people. The EU and its member-states would become third countries for the UK and vice-versa. The UK would have to re-establish customs controls at borders with EU member-states, including the border with the Republic of Ireland. A firm border between the Republic and Northern Ireland could unravel the Good Friday Agreement, according to some sources.[26]

There was quite a bit of discussion as to how long it would take for the UK to sort out details of its membership within the WTO, as it would still have to agree with the EU on its share of tariff concessions made to the EU by third parties. Even so, after the UK becomes an operational independent member of the WTO, it would find itself in a relatively difficult position. While up to 40% of its exports are targeted to the single market, it would find itself on a par with China and the Russia as far as ease of access to the single market is concerned.

- 84/85 -

A lot of the British industries, such as car assembly plants and the car parts industry, would be seriously hurt by tariffs. These supply chains would be disrupted if the UK fell back under WTO rules and firms might decide to scale back or stop production in the UK if they could not optimally reach the single market from their current factories. In addition to tariffs, non-tariff barriers to trade, such as long waits at the border, could cause further disruption as the WTO has had extremely modest results in reducing non-tariff barriers to trade in manufacturing or trade in services.

Moreover, it is far from evident that the re-accession of the UK to the WTO that will be formally required is going to be a simple, technical exercise, as some argue. Although the UK is a WTO member, this membership is bundled with that of the EU and the purpose of the negotiations with other WTO members would be to reinstate the 'single' and independent UK membership. This exercise may lead to intense negotiations with several countries or group of countries and may have an impact in the UK too, if important social groups find themselves in a less favourable situation than before Brexit.[27]

A rather peculiar situation would arise as regards to those 60 or so free trade agreements (FTAs) that cover about 35 per cent of world trade concluded by the EU that are 'mixed agreements'. These so-called 'mixed agreements' were concluded both by the EU and the UK, because their content affects the EU's exclusive competence and also some UK competences. Because of its exclusive power on trade, the EU made commitments on trade in these agreements. If the UK were no longer a member of the EU, the part on trade - services, such as financial services - would no longer apply between the UK and the non-EU country that had signed the agreement. The UK, therefore, would - based on the Vienna Convention of the Law of Treaties - either end up with a large number of FTAs which no longer have an active part on trade or no FTAs at all. It would have to start negotiating FTAs with third countries and try to achieve, on its own, terms similar to the existing ones. That is unlikely, though. The UK alone would have less clout than the EU as its imports and exports constitute roughly 20% of those of the EU; no more. As such, it is likely to be forced to content itself with worse terms of market access than those achieved by the EU or unequal market access, as with the China-Switzerland FTA, concluded in 2013, where Switzerland has given China more access to its markets than vice versa.[28]

Thus, for several years after Brexit, to say the least, British external trade would be negatively affected.

A long period of uncertainty would be weighing on Britain's trade and inward foreign investment, and this would affect economic growth. In the long run, one hopes, when bilateral trade agreements between the UK and all its main partners, including of course the EU, come into force, the situation will improve.

- 85/86 -

6. A Customised Solution

Many have come up with customised solutions for the UK. This would entail a solution that is not based on pre-existing models and would be a UK-only model, which, therefore, would take longer to negotiate as it could not be based on existing subsets of models. In trying to have a customised solution, the UK is also running a risk. The EU has always been trying to have certain objective models in place for external relations. If the UK is no trying to introduce a UK-model, this could subvert existing models, especially the Swiss and the Turkish one and would, therefore, create an even more complex set of negotiations.

Moreover, as has often been stated publicly in the almost half year since the referendum, EU leaders are of the opinion that the UK must not benefit too much from its withdrawal[29] from the EU because this would create a dangerous precedent and sort of a disintegrating force for other member states.[30]

In a rather influential paper, Bruegel[31] the think tank proposed a customized solution in August 2016. The authors argued that none of the existing models of partnership with the EU would be suitable for the UK. They proposed a new form of collaboration, a continental partnership, which would considerably less deep than EU membership but somewhat closer than a simple free-trade agreement. The proposed continental partnership would consist of the UK participating in goods, services and capital mobility and to some extent in labour mobility. The UK would participate in a new system of inter-governmental decision-making and enforcement of common rules to protect the homogeneity of the deeply integrated market. The UK would have a say on EU policies but ultimate formal authority would remain with the EU. According to and as a consequence of the proposal, there would a Europe with an inner circle, the EU, and an outer circle with less integration for the UK and potentially for Turkey, Ukraine and other countries. It appears that the paper was not warmly received and is not now considered as a pattern for the solution of the UK's dilemma.

In our view, the agreement ironed out in February 2016 between Donald Tusk and David Cameron[32] could partially be a basis for a blueprint for a custom-made solution. This solution has already been considered acceptable by the other member states, so this could be a point of departure for negotiations, even if in its earlier form it was voted down in the referendum. That agreement provided for an 'emergency brake' on in-work benefits for up to four years if there is pressure on a particular member state. This agreement would have indexed child benefit to

- 86/87 -

the level of the member state where the child resides. According to the agreement, member states could take further action against sham marriages and fraudulent immigration claims.

Another idea recently touted is the 'Canada-plus' option,[33] suggesting Britain could look to replicate the free trade deal (CETA) hammered out over seven years by the EU and the North American country. The plus would be the addition of services, especially of financial services. If the UK was proposing taking the 'Canada-plus' option, at least a part of the negotiations could be spared. David Davis, the new minister for Brexit, has called it the 'perfect starting point for our discussions with the Commission'. Earlier this year, Boris Johnson stated on Brexit that 'we can be like Canada'.[34]

The Canadians government officials seem a little sceptical as to how the UK could use CETA as a model: 'How they think CETA is the panacea, I'm confused,' said one senior Canadian government official who was deeply involved with the negotiations. "We still don't get complete access to the EU market[35] the way the Brits currently have as a member state. So I don't understand this looking towards CETA as the answer to Brexit when they will be taking a 43-year step backwards in terms of the current access they have to the European Union.'[36]

Canadians also think that the agreement cannot be replicated as the UK and Canada are two different countries: 'I honestly don't know how it can be exactly replicated,' said Sylvain Charlebois, a professor at Dalhousie University in Halifax. 'Gains are going to be different, stakes are going to be different. And therefore the deal has to be different.' [37]

7. An Evaluation of the Options

It seems from the above that none of the existing models offers a solution which meets either the Brexiteers' campaign promises or the declared aims of the UK government. It appears that none of the existing models may serve even as a good point of departure for starting negotiations.

- 87/88 -

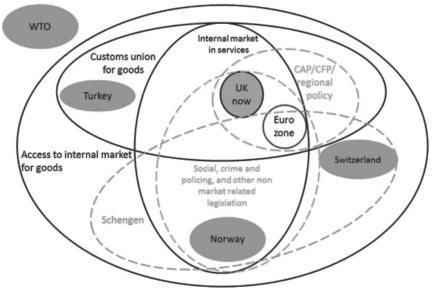

Drawing 1. Alternatives for Britain

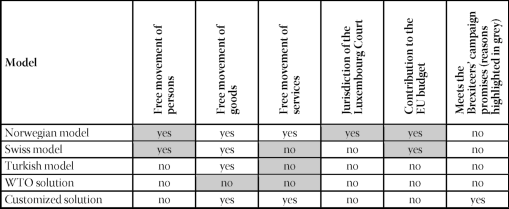

Table 1. Models and Brexit campaign promises

We suspect that the UK government probably has already drawn the conclusion that the difference between the goals and reality are irreconcilable, and remaining in the single market may prove unrealistic. This seems to be confirmed by a document photographed in the hands of a senior Conservative official on Downing Street. The handwritten note, carried by an aide

- 88/89 -

to the Tory vice-chair Mark Field after a meeting at the Department for Exiting the European Union, could be seen to say: 'what's the model? Have your cake and eat it.'[38] The Times[39] characterised the handwritten note as giving away the UK government's duplicity in negotiations and the facts that 'ministers may be reluctant to compromise with EU'. The handwritten notes also appear to rule out single market membership (the Norwegian option): 'Why no Norway -two elements - no ECJ intervention - we're a rule-taker beyond our trade with Europe. Unlikely to do internal market.'

As such at present, it appears that the UK may opt for a customised solution, which would best reflect the UK's policy goals (no free movement, no ECJ jurisdiction, and no contribution to the EU budget) but which is outside the single market. In this case, the CETA agreement may indeed serve as a point of departure, and access to the market in services would need to be added on top of it. It is unclear what the UK plans to offer in order to seal the deal and gain access to the EU market in services. It may be that the reference included in the above handwritten note 'Europe gets a good deal on security' [40] wishes to suggest that the UK would somehow top up the CETA deal on its side by UK concessions on security in exchange for UK access to the services market. It is hard to assess how realistic this idea is.

IV. Looking in Our Crystal Ball

Uncertainty is bad for business and the economy, and anything related to Brexit at the time of writing is uncertain.

(1) It is uncertain (but more likely than not) whether Brexit will happen at all.

(2) It is not certain how it will happen, namely whether the Houses of Parliament will be involved in the process and whether there will be a parliamentary decision or referendum concerning the terms negotiated. It is also uncertain whether the UK will strive to conclude a transitional arrangement before concluding a final agreement on exiting the EU.

(3) It is not certain when it will happen, namely whether the notice on withdrawal will be served on the EU in March 2017 and whether the negotiating period will be a two year period or it will be prolonged by a transitional agreement.

(4) It is also uncertain whether the UK government will negotiate to customise for itself one of the existing models or will try to negotiate a solution tailor-made for the UK or if it will exit the EU by default.

- 89/90 -

ad 1) Ms. May and her government very clearly are of the opinion that Brexit must take place, as the referendum has decided on the exit of the UK ('Brexit means Brexit') from the EU and the question is merely how and when. Ms. May seems to be of the opinion that Brexit must take place whatever the consequences may be. On the other hand, according to former Prime Minister John Major, there is a 'perfectly credible' case for a second referendum on leaving the European Union.[41] Former Prime Minister Tony Blair said in an interview that he was not predicting Brexit would not happen, only that there was a possibility it would not. 'It can be stopped if the British people decide that, having seen what it means, the pain-gain, cost-benefit analysis doesn't stack up. And that can happen in one of two ways. I'm not saying it will [be stopped], by the way, but it could. I'm just saying: until you see what it means, how do you know?'[42]

I am currently of the opinion that if an Article 50 notice on withdrawal is made then withdrawal will take place, whether through an agreement of through the passage of time. In that sense, the question is whether the notice on withdrawal will be served or not.

ad 2) Given the decision of the High Court[43] on the need to involve Parliament in the withdrawal of the UK from the EU and the expected decision on appeal by the Supreme Court, the Houses of Parliament will likely be involved in and have a decisive say in the UK's decision on withdrawal and probably also in the negotiations with the EU. If Parliament is involved in the political process of the withdrawal under Article 50 of the TEU and with the preparation of the exit strategy then the UK may not file its withdrawal notice in March 2017 or may not file it at all. This may lead at some point to snap elections in the UK, as the UK cannot leave the EU in limbo for ever even if the unfortunate wording of Article 50 of the TEU makes the EU a hostage of the departing member state. If the snap elections would result in a Parliament with a very different composition and in a clear mandate for exit or remain, this may lead to the UK deciding on filing a notice on withdrawal under Article 50 of the TEU or not filing it at all.

Even if the EU leaders now are of the opinion that there can be no negotiations before the withdrawal notice is submitted[44] and the UK government was also of this opinion before the referendum,[45] it may be that Angela Merkel - who emerges somehow as the only European authority on Brexit - would somehow give a sign to the UK that the EU is ready for transitional arrangements[46] as the two year withdrawal period is insufficient for creating a satisfactory new regime for UK-EU relations.

- 90/91 -

ad 3) Given the uncertainty as to the role of Parliament and the flexibility of the EU, it is not clear when the negotiations would start, how long those negotiations would last and when they would end.

ad 4) Most important of all, it is unclear what the negotiating aims and strategy of the UK are. The stated aim of the UK government is to get maximum access to the single market with a minimum or no freedom of movement, no payment to the EU and no acceptance of the jurisdiction of the EU Court of Justice. According to former Prime Minister Blair, attempting to secure access to the single market will be the defining negotiation. "Either you get maximum access to the single market - in which case you'll end up accepting a significant number of the rules on immigration, on payment into the budget, on the European Court's jurisdiction. People may then say, 'Well, hang on, why are we leaving then?' Or alternatively, you'll be out of the single market and the economic pain may be very great, because beyond doubt if you do that you'll have years, maybe a decade, of economic restructuring.'[47]

So it seems from the above and the analysis under Section 3 above that none of the existing models offer anything similar to what the UK seems to want.[48] The UK will therefore either have a tailor-made solution or no solution at all and. if the UK submits its notice for withdrawal under Article 50 of the TEU, at the end of the two year term it would likely exit by default and without an agreement and it would simply fall back in international trade in goods and services according to the WTO rules. With this potential outcome and the uncertainties attached, the UK government has been forced to offer compensatory state aid for an industry and may be forced to offer the same for others.[49]

Yet the outcome does not bode well for the UK or the EU as it seems that the UK government is split and intellectually ill prepared[50] and probably dishonest including the foreign secretary, Boris Johnson who are '...saying things that are intellectually impossible, politically unavailable, so ... [are] ... not offering the British people a fair view of what is available and what can be achieved in these negotiations'.[51]

As to the next steps as they are visible at the time of writing, a lot may depend on the decision of the Supreme Court in the case Miller & Tozetti Dos Santos -v- The Secretary of State for Exiting the European Union[52] as to whether the Houses of Parliament will be implicated in the decision on the withdrawal or not.

- 91/92 -

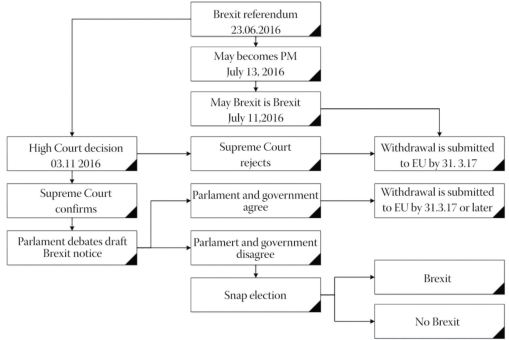

Drawing 2. Likely timeline on Brexit

If the Houses of Parliament will participate in the decision-making, it may be difficult to maintain Ms. May's timetable and submit the withdrawal notice when she planned. More importantly, the Parliament may also somehow prevent the government from submitting the withdrawal notice to the EU at all, in which case snap elections are likely to be called. Based on the snap elections, a new parliament with a different political make-up could be elected and this could mean a new government, potentially with a different set of goals.

Our crystal ball has not yielded a clear prediction of what exactly will happen in the coming twelve months. What is clear, it is as if the UK has stepped Through the Looking Glass[53] and from June 24 Brexiteers, Remainers and the entire EU and its population now found itself on the other side, in a strange parallel, unsafe and mysterious world where clocks work backwards. ■

NOTES

[1] Irish Times view: Brexit a bewildering act of self-harm http://www.irishtimes.com/opinion/editorial/irish-times-view-brexit-a-bewildering-act-of-self-harm-1.2698212.

[4] Historical Institutionalist Perspective by Paul Pierson' Harvard University and Russell Sage Foundation Program for the Study of Germany and Europe Working Paper No. 5.2 (October 25, 1994).

[5] Consolidated Versions Of The Treaty On European Union And The Treaty On The Functioning Of The European Union, OJ, July 6, 2016 C-202 p. 43.

[6] 'The Lord Chief Justice asked whether once Article 50 had been invoked it could be stopped and whether some form of 'conditional notice' could be given. Pannick said there was no possibility of the UK either giving conditional notification or stopping it once it had been started. But the question of the 'reversibility' of Article 50 surfaced again in the afternoon, and the lord chief justice asked for further clarification of the procedure. Helen Mountfield QC, who represents the crowd-funded People's Challenge, said: 'There's no authority [for reversing a decision to leave the EU] because it's never been attempted before. Reversibility is a question of interpretation of EU law.' None of the parties in the case are so far suggesting that departure is anything other than a one-way street.' https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2016/oct/13/government-cannot-trigger-brexit-without-mps-backing-court-told-article-50?CMP=share_btn_fb.

[7] See the UK Parliament's own debate on this: https://hansard.parliament.uk/commons/2016-11-07/debates/C59A3B55-6FB3-455D-B704-F8B1BF5A5AF5/Article50.

[8] 'May hints she may be open to transitional agreement with EU'. Reuters, November 21, 2016. http://uk.reuters.com/article/uk-britain-eu-industry-brexit-idUKKBN13G10H.

[9] The notes revealed on 28.11.2016 said: 'Transitional - loath to do it. Whitehall will hold onto it. We need to bring an end to negotiations.' UK unlikely to stay in single market, Tory document suggests: https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2016/nov/28/uk-unlikely-to-stay-in-single-market-tory-document-suggests.

[10] http://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2016/10/13-tusk-speech-epc/

[11] 'Hard Brexit' or no Brexit, Donald Tusk warns UK: https://www.ft.com/content/df4885fa-9160-11e6-8df8-d3778b55a923.

[12] Peter Ungphakorn, Nothing simple about UK regaining WTO status post-Brexit. http://www.ictsd.org/opinion/nothing-simple-about-uk-regaining-wto-status-post-brexit. Last accessed, November 22, 2016. Alan Beattie, 'Brexit and the WTO option: Key questions about a looming challenge' Financial Times, 12 July, 2016. https://www.ft.com/content/5741129a-4510-11e6-b22f-79eb4891c97d. Last accessed, November 22, 2016.

[13] Council conclusions on a homogeneous extended single market and EU relations with Non-EU Western European countries. p. 4. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/uedocs/cms_data/docs/pressdata/en/er/146315.pdf. Last accessed: November 24, 2016.

[14] Jean-Claude Piris: If the UK votes to leave: the seven alternatives to EU membership. Citing: Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 'The EEA Agreement and Norway's other agreements with the EU, 2012-13. See also Jacques Pelkmans, 'The EEA Review and Liechtenstein's Integration Strategy' Centre for European Policy Studies, Brussels, March 2013. https://www.cer.org.uk/publications/archive/policy-brief/2016/if-uk-votes-leave-seven-alternatives-eu-membership. Last accessed: November 24, 2016.

[15] See for example: What would 'out' look like? https://www.google.hu/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=2&cad=rja&uact=8&ved=0ahUKEwjMu8qr577QAhVMuhQKHcFdDnIQFggkMAE&url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.policy-network.net%2Fpublications_download.aspx%3FID%3D9287&usg=AFQjCNHzPLpVi1t1c51D_OzKJ3e7lwIjYA&sig2=fvKTS-mwCNCkBYRc1wmVPA p.5 n.13 citing: http://www.cbi.org.uk/media/2133649/doing_things_by_halves_-_lessons_from_switzerland_and_norway_cbi_report_july_2013.pdf.

[16] Safe harbour: why the Norway option could take the risk out of Brexit. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/business/2016/06/18/safe-harbour-why-the-norway-option-could-take-the-risk-out-of-br/.

[17] See (n 14) p. 12.

[18] Ibid p. 12.

[19] Council conclusions on EU relations with EFTA countries, 3060th GENERAL AFFAIRS Council meeting Brussels, 14 December 2010 http://www.consilium.europa.eu/uedocs/cms_data/docs/pressdata/en/foraff/118458.pdf.

[20] Council conclusions on EU relations with EFTA countries Brussels, 20 December 2012 http://eeas.europa.eu/archives/docs/norway/docs/2012_final_conclusions_en.pdf, p. 6.

[21] 'Swiss immigration: 50.3% back quotas, final results show'. http://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-26108597.

[22] See (n 12) p. 7. point 47. Last accessed: November 24, 2016.

[23] Press release 3310th Council meeting Economic and Financial Affairs Brussels, 6 May 2014 http://www.consilium.europa.eu/uedocs/cms_data/docs/pressdata/en/ecofin/142513.pdf, p 18. Last accessed: November 24, 2016.

[24] https://www.admin.ch/gov/fr/accueil/documentation/communiques.msg-id-63829.html

[25] http://ec.europa.eu/enlargement/pdf/turkey/association_agreement_1964_en.pdf

[26] Northern Ireland could veto Brexit, Belfast high court told: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/oct/04/ireland-to-seek-special-status-to-keep-open-border-with-uk-amid-hard-brexit-fears; Ireland confirms talks under way over post-Brexit border controls: https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2016/oct/10/ireland-confirms-talks-under-way-over-post-brexit-border-controls.

[27] See (n 11).

[28] Free Trade Agreement between the People's Republic of China and the Swiss Confederation http://fta.mofcom.gov.cn/topic/enswiss.shtml.

[29] Brexit: Francois Hollande demands UK pay heavy price for deciding to leave EU http://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/politics/brexit-hollande-ffance-uk-must-pay-price-eu-withdrawal-crisis-a7349756.html.

[30] David Davis warns EU leaders not to go ahead with 'punishment plan' for Britain: http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2016/10/10/theresa-may-brexit-talks-denmark-netherlands-live/.

[31] Jean Pisai-Ferry, Norbert Röttgen, André Sapir, Paul Tucker And Guntram B. Wolff: Europe after Brexit: A proposal for a continental partnership, http://bruegel.org/2016/08/europe-after-brexit-a-proposal-for-a-continental-partnership/.

[32] Decision of the Heads of State or Government meeting within the European Council concerning a new settlement for the United Kingdom within the European Union: https://www.documentcloud.org/documents/2716240-Brexit-Deal.html.

[33] UK unlikely to stay in single market, Tory document suggests: https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2016/nov/28/uk-unlikely-to-stay-in-single-market-tory-document-suggests.

[34] Canada's trade deal with EU a model for Brexit? Not quite, insiders say https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/aug/15/brexit-canada-trade-deal-eu-model-next-steps; Britain must earn from the EU-Canada Ceta trade deal saga https://www.theguardian.com/business/2016/oct/29/britain-must-learn-from-the-eu-canada-ceta-trade-deal-saga.

[35] The agreement promises that around 98.6% of goods traded between Canada and the EU will be free of duty and empowers regulatory bodies to accept the standards and tests carried out in each other's jurisdictions. While the trade deal aims to liberalize services, hundreds of exceptions are listed. Under CETA, Canada will have no hand in setting EU regulations or formulating product standards and no access to the banking passport system that would have allowed its banks and financial services to trade freely. The freedom of movement clauses are primarily focused on businesspeople.

[36] Canada's trade deal with EU a model for Brexit? Not quite, insiders say, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/aug/15/brexit-canada-trade-deal-eu-model-next-steps;

[37] Canada's trade deal with EU a model for Brexit? Not quite, insiders say https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/aug/15/brexit-canada-trade-deal-eu-model-next-steps;

[38] UK unlikely to stay in single market, Tory document suggests: https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2016/nov/28/uk-unlikely-to-stay-in-single-market-tory-document-suggests.

[39] 'Have cake and eat it' - aide reveals Brexit tactic Ministers may be reluctant to compromise with EU http://www.thetimes.co.uk/edition/news/have-cake-and-eat-it-aide-reveals-brexit-tactic-wrj58bjbn.

[40] Ibid.

[41] John Major: case for second Brexit referendum is credible, https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2016/nov/25/brexit-sir-john-major-says-perfectly-credible-case-for-second-referendum.

[42] http://www.newstatesman.com/politics/uk/2016/11/tony-blair-s-unfinished-business

[43] The Queen on the application of (1) Gina Miller & (2) Deir Tozetti Dos Santos v The Secretary of State for Exiting the European Union, (1) Grahame Pigney & Others, (2) AB, KK, PR and Children - Interested Parties Mr George Birnie & Others - Interveners [2016] EWHC 2768 (Admin) Case No. CO/3809/2016 and CO/3281/2016 3 November 2016 https://www.judiciary.gov.uk/judgments/r-miller-v-secretary-of-state-for-exiting-the-european-union/.

[44] Brexit: Germany rules out informal negotiations see: http://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-36637232.

[45] See: The process for withdrawing from the European Union see: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/504216/The_process_for_withdrawing_from_the_EU_print_ready.pdf.

[46] May hints at transition deal on Brexit to avoid 'cliff edge' for business https://www.theguardian.com/business/2016/nov/21/government-working-hard-avoid-brexit-cliff-edge-business-theresa-may-cbi.

[47] http://www.newstatesman.com/politics/uk/2016/11/tony-blair-s-unfinished-business.

[48] Brexit and beyond: how the United Kingdom might leave the European Union http://ukandeu.ac.uk/research-papers/.

[49] UK seeking tariff-free EU deal for carmakers, Nissan told https://www.theguardian.com/business/2016/oct/30/nissan-eu-tariff-free-brexit-sunderland.

[50] According to a memo by Deloitte leaked to the press on November 6, 2017 'Despite extended debate among permanent secretaries, no common strategy has emerged,' http://www.thetimes.co.uk/edition/news/cabinet-split-threatens-to-derail-may-s-brexit-talks-hxfwmv2td.

[51] European ministers ridicule Boris Johnson after prosecco claim, https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2016/nov/16/european-ministers-boris-johnson-prosecco-claim-brexit.

[52] See above (n 42).

[53] Lewis Carroll: Through the Looking-Glass (Dover Thrift Editions, Paperback. Mineola May 14, 1999, New York).

Lábjegyzetek:

[1] The author is Phd, Associate Professor of International and European Law at the Faculty of Law and Political Sciences of ELTE University.

[2] The author is an attorney at law and a part-time lecturer at the Department of International Law at the Faculty of Law and Political Sciences of ELTE University.