Tamás Kende[1]: Distant Cousins - The Exhaustion of Local Remedies in Customary International Law and in the European Human Rights Contexts (ELTE Law, 2020/2., 127-142. o.)

Article 35(1) of the European Convention of Human Rights (ECtHR) provides that it is an admissibility criterion for a matter to heard by the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) that all domestic remedies have been exhausted according to the generally recognised rules of international law.[1] In this context, the limitation 'according to the generally recognised rules of international law' is of interest. Did the framers of the age-old institution of exhaustion of local remedies (ELR) simply transpose, 'as is,' this rule in the context of the ECtHR? If so, does this rule apply to admissibility to the ECHR in the same way as it applies to the admissibility of claims to the International Court of Justice (ICJ)? Or did the framers of the ECtHR just (half)apply an analogy and does it apply rather differently? The latter would not be surprising, as ELR applies in a completely different context, is a precondition of a completely different process and the ECHR in fact does not apply public international law but it applies the rules of a treaty (the ECtHR), its own practice and uses general public international law as a last resort.

I. The Exhaustion of Local Remedies Rule under General Public International Law

Public international law has developed organically over centuries (some parts of it over millennia) and it applied different rules when two sovereigns directly clashed and when a sovereign and subjects of another sovereign were in conflict.

In the former scenario as the Permanent Court of International Justice stated in the Phosphates in Morocco Case (1938) 'this act being attributable to the state and described as contrary to the treaty right of another state, international responsibility would be established immediately as between the two states'.[2]

- 127/128 -

In the latter situation, public international law mandated a much more complicated set of procedures to be followed before it would start to apply. This set of procedures is called exhaustion of local remedies. In public international law, this requirement of ELR dates back to the Middle Ages[3] and concerned the protection by sovereigns of their nationals injured abroad. The requirement concerned a sequence of procedures to follow: such nationals were to first seek redress from the foreign sovereign and 'only if this was not forthcoming could they turn to their own prince for aid'.[4] In this way, the rule gave the host state a certain dispute settlement function in the transnational (state v. alien) disputes in which they were concerned. In classical international law (i.e. international law predating the end of WW2), individuals and corporations could not sue states under it, and a construct was put in place: by causing injury or allowing injury to be caused to foreigners, the state where the injury was suffered injured the home state of the foreigners concerned was. Vattel, a Swiss giant of 18[th] century international law, described this with the following sentence: 'Quiconque maltraite un Citoyen offense indirectement l'Etat...'[5] In Mavrommatis in 1924, it was further explained by the Permanent Court of International Justice as follows:

It is an elementary principle of international law that a State is entitled to protect its subjects, when injured by acts contrary to international law committed by another State, from whom they have been unable to obtain satisfaction through the ordinary channels.[6]

The ICJ clearly stated in the Interhandel case that ELR was a rule of customary international law.[7] The court declared that

The rule that local remedies must be exhausted before international proceedings may be instituted is a well-established rule of customary international law; the rule has been generally observed in cases in which a State has adopted the cause of its national whose rights are claimed to have been disregarded in another State in violation of international law.

In 1986 ELSI[8] the ICJ also confirmed that ELR was 'an important principle of customary international law'[9].

- 128/129 -

The ELR rule reflects a compromise achieved during the centuries between at least two conflicting interests: that of the State where the alleged violation occurred and those of the individual concerned. It is in the interest of the host State to have the issues of law and fact which the claim involves dealt with by its own judiciary in order to discharge its responsibility and to redress the wrong committed.[10] The individual concerned has a slightly but not diametrically opposite goal: he/she/it wants the alleged wrong remedied in the quickest way in its favour. A rule that requires resort to local remedies in most cases hampers the individual from having immediate access to seemingly quick and - if the local fora are biased - then more favourable and independent fora. Arbitrator Bagge framed this as follows: '...it appears hard to lay on the private individual the burden of incurring loss of money and time by going through the courts...'[11]

The law as it currently stands still reflects this compromise with certain major changes in human rights, investment protection, consular protection[12] etc.

Domestic law also applies the ELR requirement in certain exceptional cases. The ELR requirement has appeared, for example, in the US jurisprudence in relation to the Alien Tort Statute ('ATS') of 1789. In Sosa v Alvarez-Machain,[13] the U.S. Supreme Court noted that, in litigation under the ATS, consideration would certainly be given to the rule of exhaustion of local remedies 'in an appropriate case'. Before Sosa, one school of thought argued that, under the ATS, plaintiffs needed to exhaust local remedies[14] and another argued the opposite[15]. In Sosa, ELR essentially became an exception.

Elsewhere in the US jurisprudence, there was a dispute in the application of the ELR in a situation where taking exception to the Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act (FSIA) abrogates the defence of sovereign immunity when a foreign government takes property in violation of international law. It was not clear whether, in these situations, plaintiffs must first exhaust local remedies in the relevant foreign country before filing suit in the United States. In the absence of clear statutory guidance, the circuit courts have reached divergent conclusions.

- 129/130 -

In the jurisprudence, it was argued[16] that that international law does not oblige US courts to impose the exhaustion rule. Courts should, however, require American plaintiffs in cases where foreign governments have taken their property to exhaust local remedies (in foreign jurisdictions) when the president advises such courts that the requirement would advance the national security or foreign policy interests of the United States.

The ILC Draft articles on the responsibility of states from 2001[17] seem to deal with ELR as a matter of admissibility (a procedural filter) and provides in Article 44 that

The responsibility of a State may not be invoked if: ... (b) the claim is one to which the rule of exhaustion of local remedies applies and any available and effective local remedy has not been exhausted.

As such, the draft itself distinguishes between state to state claims (where ELR does not apply) and state to foreigner disputes where the ELR rules apply. As the ILC has stated, the provision 'is formulated in general terms in order to cover any case to which the exhaustion of local remedies rule applies, whether under treaty or general international law, and in spheres not necessarily limited to diplomatic protection'.[18]

It was not clear for some time whether the ELR is a matter of substance (there is no internationally wrongful act if the remedies were not exhausted) or a matter of procedure[19] (responsibility cannot be invoked). If it is a matter of substance,[20] state responsibility at the international law level only arises after the fruitless resort to local remedies and international law had not been violated at the time the initial injury to the individual was committed. On the other hand, if the liability of a State under international law is already generated at the time of the initial injury to the individual, the responsibility of a State at the international level is already created at the moment it committed an internationally wrongful act, yet its responsibility cannot be enforced until ELR has been complied with. The fact that the draft

- 130/131 -

contains the language 'cannot be invoked' and the other fact that the draft deals with ELR as a matter of admissibility seem to suggest that the ILC considers it as a matter of procedure, not of substance.

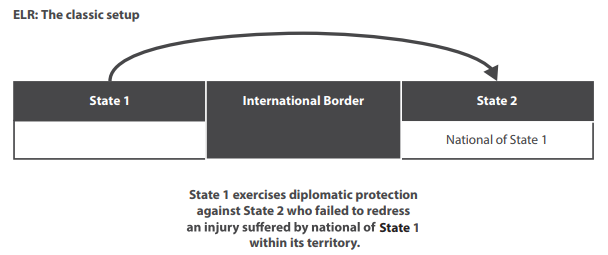

Figure 1: Description of the classic scenario for exhaustion of local remedies

The ILC Draft articles on diplomatic protection from 2006 deals with ELR as a precondition of diplomatic protection.[21] The draft articles provide in their Article 14(1) that A State may not present an international claim in respect of an injury to a national (...) before the injured person has... exhausted all local remedies.' in situations where (see Art 14.3.) 'such an international claim... is brought preponderantly on the basis of an injury to a national.' The ILC Draft - for the first time in international law - actually defines local remedies as 'legal remedies which are open to an injured person before the judicial or administrative courts or bodies, whether ordinary or special, of the State alleged to be responsible for causing the injury.'

Although the ILC draft itself does not go into detail about the way and depth to which local remedies need to be exhausted, the term vertical and horizontal exhaustion has been coined, primarily among the French-speaking students of the ELR rule.

The ILC, in its draft, has also identified several traditional formulas applied in leading international cases where the international tribunals dispensed with ELR. Vertical exhaustion is the requirement of going through all available instances and horizontal exhaustion is the requirement that all meaningful arguments and all necessary evidence be presented, i.e. the claim be pursued at full speed and properly resourced.[22] This latter requirement was

- 131/132 -

tested in the famous Ambatielos case,[23] where the Greek shipbuilders lost the case because in front of the international instance it was successfully argued that they had failed to produce an important witness during the lawsuits in front of local instances. A witness from an agency of the respondent (the Navy) was allegedly prevented from giving testimony. Nevertheless, the Court believed that such a lack of use of a witness was equal to not meeting the ELR requirement.

Table 1: Situations where exhaustion of local remedies can be dispensed with

| FORMULA | CASES[a] |

| 'the local court has no jurisdiction over the dispute in question' | Panevezys-Saldutiskis Railway[b] Norwegian Loans[c] innish Ships Arbitration[d] |

| 'national legislation justifying the acts of which the alien complains will not be reviewed by local courts' | Forêts du Rhodope Central[e] Ambatielos[f] Interhandel[g] |

| 'the local courts are notoriously lacking in inde- pendence' | Robert E. Brown[h] |

| 'there is a consistent and well-established line of precedents adverse to the alien' | S.S. 'Seguranca, X. v. Federal Republic of Germany[i] |

| 'the local courts do not have the competence to grant an appropriate and adequate remedy to the alien' | Velasquez Rodriguez[j] |

| 'respondent State does not have an adequate system of judicial protection' | Mushikiwabo and others v. Barayagwiza[k] |

[a] The commentary of the Draft articles on Diplomatic Protection 2006 quotes all these cases and list the various tests.

[b] The Panevezys-Saldutiskis Railway Case Estonia v Lithuania General List No. 74 and 76 Judgment No. 29, 28 February 1939 PERMANENT COURT OF INTERNATIONAL JUSTICE Judicial Year 1933.

[c] Case of Certain Norwegian Loans, [1957] I.C.J. Rep. 9.

[d] Claim of Finnish shipowners against Great Britain in respect of the use of certain Finnish vessels during the war (Finland, Great Britain) 9 May 1934 VOLUME III pp. 1479-1550.

[e] Affaire des forêts du Rhodope central (question préalable) (Grèce contre Bulgarie) 4 novembre 1931, 29 mars 1933 VOLUME III 1389-1436.

[f] Ambatielos case (n 23).

[g] Interhandel Case (n 7).

[h] (United States v Great Britain) (1923) 6 R.I.A.A. 120.

[i] S.S. Seguranca (United States of America/Great Britain), Award, ... X v Federal Republic of Germany, ECmHR Case No 27/55.

[j] Inter-American Court of Human Rights Case of Velásquez-Rodríguez v Honduras Judgment of July 29, 1988.

[k] Louise Mushikiwabo, et al., Plaintiffs, v Jean Bosco BARAYAGWIZA, Defendant. No. 94 CIV. 3627 (JSM)

- 132/133 -

Based on the above review of the jurisprudence, Article 15 of the draft articles provides five exceptions where local remedies would not need to be exhausted. These are situations where (a) there are no reasonably available local remedies to provide effective redress, or the local remedies provide no reasonable possibility of such redress; (b) there is undue delay in the remedial process which is attributable to the State alleged to be responsible; (c) there was no relevant connection between the injured person and the State alleged to be responsible at the date of injury; (d) the injured person is manifestly precluded from pursuing local remedies; or (e) the State alleged to be responsible has waived the requirement that local remedies be exhausted. The introduction of these exceptions to the general rule are already quite ground-breaking and they are likely to explain the reticence of the states when the draft articles are submitted to the General Assembly for review and for taking next steps towards turning the draft articles into an international treaty.

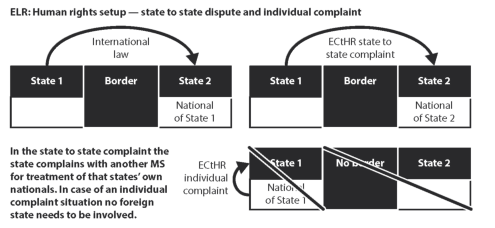

II. Structural Differences between ELR under General Public International Law and ELR within the Context of the Enforcement of Human Rights

Since the end of WW2, states seem to have extended the application of ELR from the diplomatic protection of citizens abroad to the protection of human rights. The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and its Optional Protocol, the former Article 26 (now article 35) of the European Convention on Human Rights and the American Convention on Human Rights all provide for it and call it a principle of general customary international law.[24] These provisions could suggest that the age-old customary rule existing in the field of the treatment of aliens is now applied by analogy in the protection of human rights.

Yet, in human rights, the context in which ELR needs to operate is fundamentally different from the classic setup of diplomatic protection. The parties involved in the two situations are fundamentally different. In the classic one, ELR is a condition for diplomatic protection

- 133/134 -

afforded to one's own national who has suffered an injury abroad. Hence, the situation is first that of a state and an alien - although a resident of planet Earth - transforming into a legal conflict between the state of nationality and the foreign host state. Diplomatic protection is the lever to move the dispute between the foreign national and the host state into the realm of public international law. In the context of human rights, the individual most likely has never left his/her country and the conflict - even after ELR remains a conflict between a single state and an individual who, in most of the cases, is its own citizen.[25]

Moreover, even after an ELR, a state and an individual remain in conflict while, in the classic setup, when the home state grants diplomatic protection, it takes on the claims of the individual who becomes a simple bystander or witness in the conflict between the home and the host state. So while in the classic setup ELR is a condition for diplomatic protection to be granted, in the human rights situation, ELR is a condition for granting access to international fora.

Figure 2: Two situations compared: ELR in case of an international law dispute and in the case of a human rights complaint

It may be self-evident but it makes sense to mention that while the classic setup is well grounded in customary international law, which is just being codified (or not, if the Draft articles on diplomatic protection share the fate of the Draft articles on state responsibility), access to international fora in human rights is exclusively based on treaty law. It therefore makes sense to repeat the question that was asked at the outset: what did the framers of Article 35 mean when they incorporated ELR by reference as it is in customary international law?

- 134/135 -

III. Other Differences between ELR under Customary International Law and ELR within the Context of the Enforcement of Human Rights in Europe, in Particular in the ECHR Context

There are also teleological differences. The primary reason for ELR in international law is the protection of the 'host state's' sovereignty. The reasons for the introduction of the ELR rule in international human rights treaties on the other hand were manifold. The travaux préparatoires of the ICCPR[26] and of the ECtHR[27] show that the ELR rule was discussed to avoid (1) local courts being replaced by international courts and (2) international courts being overloaded with complaints and ultimately to (3) uphold the sovereignty of the member states.

The ECHR has also politely framed one additional reason for ELR. In Burden v United Kingdom[28] it was stated that the ECHR should have the benefit of the views of the national courts, as being in direct and continuous contact with the vital forces of their countries. In Selmouni v France[29] the ECHR also linked the requirement to the assumption, reflected in Article 13 of the ECtHR, that the domestic legal order will provide an effective remedy for violations of Convention rights.[30]

The aim of human rights systems such as the European one based on the ECtHR is to provide effective protection to individuals in the member states. The European Commission of Human Rights aimed at the same thing as the ECHR now seeks, to ensure effective protection, based on a certain level of burden sharing between the national and the international fora. This burden-sharing - such as in general public international law - means that before proceedings are brought to an international body, the State concerned must have had the opportunity to remedy matters through its own legal system. In the Akdivar case, the Court stated that

...the rule of exhaustion of local remedies... obliges those seeking to bring their case against the State before an international judicial or arbitral organ to use first the remedies provided by the national legal system. .The rule is based on the assumption, reflected in Article 13 of the Convention, that there is an effective remedy available in respect of the alleged breach in the domestic

- 135/136 -

system whether or not the provisions of the Convention are incorporated in national law. In this way, it is an important aspect of the principle that the machinery of protection established by the Convention is subsidiary to the national systems safeguarding human rights.[31]

This principle of subsidiarity has since appeared in several judgments[32] and many policy documents, such as the Brighton Declaration[33] that states in its point 3 that

The States Parties and the Court share responsibility for realising the effective implementation of the Convention, underpinned by the fundamental principle of subsidiarity. The Convention was concluded on the basis, inter alia, of the sovereign equality of States. States Parties must respect the rights and freedoms guaranteed by the Convention, and must effectively resolve violations at the national level. The Court acts as a safeguard for violations that have not been remedied at the national level. Where the Court finds a violation, States Parties must abide by the final judgment of the Court.

This clearly shows that ELR is an effective means of power-sharing between member states and the Court in Strasbourg. The principle is also embedded in Protocol No. 15 amending the Convention, which in its Article 1 on subsidiarity is quite specific about the desired division of labour between domestic courts and the ECHR.[34] It provides as follows:

Affirming that the High Contracting Parties, in accordance with the principle of subsidiarity, have the primary responsibility to secure the rights and freedoms defined in this Convention and the Protocols thereto, and that in doing so they enjoy a margin of appreciation, subject to the supervisory jurisdiction of the European Court of Human Rights established by this Convention.

This addition to the preamble of the ECtHR underpins the importance of Article 35 and ELR.

In what ways is the rule different in the human rights context and, in particular in the context of the ECtHR, different from the requirement of ELR in customary international law? When, in the period after the Second World War, the rule was introduced into some human rights treaties, the aim was to emulate and transpose the rule 'as is' into human rights protection and so ELR in human rights protection is to be interpreted in the light of

- 136/137 -

the equivalent rule in the field of diplomatic protection.[35] The rules, however have developed differently because of the many structural and other differences quoted above. According to D'Ascoli and Scherr, the main reason for this differentiation is the aim to which the rules were applied, the classic one for safeguarding sovereignty, the other to protect individual rights.[36]

According to the report of the ILC, ELR under general public international law and in the context of the ECtHR are different because the practice of the ECtHR is more lenient as to when local remedies may be dispensed with. The ILC draft articles on diplomatic protection of 2006 also find that international jurisprudence uses essentially three different tests to dispense with ELR, namely, where local remedies

(i) 'are obviously futile';

(ii) 'offer no reasonable chance of success';

(iii) 'offer no reasonable possibility of effective redress.

The ILC considers that the practice of the ECHR is based on the second test, and it found that this test was way more relaxed than it was under general customary international practice. The ILC determined that, based on the practice it identified, the third test seems more appropriate to reflect the status in general public international law.[37] The ILC goes on to describe how much more flexible the ECHR test is than the test applied in customary international law.

There are other differences as well. The number of cases originating in one state and ending up in an international tribunal (ICJ or other) under customary international law are nowhere near comparable to case numbers, for example, in front of the ECHR. Besides the fact that overloading the international tribunal is a real possibility, this has several other consequences: the fact, for example, that there was no legal remedy in one case in one country may be proof of the lack of remedies in a similar case in front of the same court. Such an influx of 'mass torts' would likely never happen in general international law, while it happens so often in front before the ECHR that it has developed a new procedure known as the pilot-judgment procedure[38] as a means of dealing with large groups of identical cases that derive from the same underlying problem in order to avoid completely repetitive work.

Large case numbers from countries and a functional limitation of cases to human rights allow the court to know the functioning of each of the judicial instances in each of the member states intricately and to know whether that instance is able to provide a remedy in a given case. Functional specialisation also allows the ECHR to determine, even in advance, whether an instance (given its competences and practice) would be capable in theory of pro-

- 137/138 -

viding an effective remedy to the alleged injury or not. This is not something general public international law instances could ever provide.

The fact that there is a convention and close to 50 member states behind the ECHR also makes it possible for it to study in parallel whether, with regard to a specific right ensured in the convention, a particular instance of the different member states is an effective remedy or not. Not only can the ECHR study in parallel whether, for example, constitutional courts in different member states are effective remedies but also whether different legal causes in different domestic laws that allow recourse to constitutional courts provide adequate remedies in general or just in the context of that particular right ensured in the Convention or that kind of remedy ensured in the convention. The ECHR's practical guide on admissibility[39] gives many examples on this particularity.[40] Such detail and precision and that the Court issues a guide to its own practice relating to ELR are unheard of in terms of legal certainty in international law.

There are by now many differences in applying ELR in general public international law and the ECtHR setting. The European Commission of Human Rights[41] had earlier issued a notice[42] on the interpretation of Article 26 and then the ECtHR issued a practical guide on admissibility[43] which officially details the application of the ELR rule. The notice confirms inter alia the international law context of the rule. The guide, in its para 64, refers to the Interhandel case, acknowledging the international legal background of the rule. However, in para 68. it refers to flexibility in both ways:

The exhaustion rule may be described as one that is golden rather than cast in stone. The Commission and the Court have frequently underlined the need to apply the rule with some degree of flexibility and without excessive formalism, given the context of protecting human rights (Ringeisen v. Austria, § 89; Lehtinen v. Finland (dec.); Gherghina v. Romania (dec.) [GC], § 87). The rule of exhaustion is neither absolute nor capable of being applied automatically (Kozacioğlu v. Turkey [GC], § 40). For example, the Court decided that it would be unduly formalistic to require the applicants to avail themselves of a remedy which even the highest court of the country had not obliged them to use (D.H. and Others v. the Czech Republic [GC], §§ 116-18). The Court took into consideration in one case the tight deadlines set for the applicants' response by emphasising the 'haste' with which they had had to file their submissions (Financial Times Ltd and Others v. the United Kingdom, §§ 43-44). However, making use of the available remedies in accordance with domestic procedure and complying with the formalities laid down in national

- 138/139 -

law are especially important where considerations of legal clarity and certainty are at stake (Saghinadze and Others Georgia, §§ 83-84).'

This approach is clearly very different from the approach of the Ambatielos tribunal and also from the approach of the ILC in its draft articles on diplomatic protection.

The guide goes on to detail the rule at length but it does not mention either the vertical or the horizontal exhaustion requirement as set out in Ambatielos. On the contrary, in para. 71, it stipulates that in domestic proceedings the complaint must be raised 'at least in substance' but there is no requirement that all reasonable arguments be made and all possible evidence be availed of.[44] This probably comes from the Van Oosterwijck case, where the Belgian government raised the issue that the complainant never referred to the ECtHR during domestic proceedings. The European Commission of Human Rights[45] stated that 'la référence à la Convention ne lui paraissait pas, en l'espèce, nécessaire, étant donné le caractère peu précis de ses dispositions pertinentes'. Horizontal exhaustion has, therefore been understood first as a requirement to raise in domestic proceedings as a cause of action and then it was dispensed with as unnecessary, although in customary international law, for example, the ambit of this requirement is far wider.[46]

Paragraph 79 of the Guide itself sets out instances where it thinks there may be special circumstances dispensing the applicant from the obligation to avail him or herself of the domestic remedies available (Sejdovic v Italy [GC], § 55) in that context and, unlike in the general setting of public international law, it provides that ELR

is also inapplicable where an administrative practice consisting of a repetition of acts incompatible with the Convention and official tolerance by the State authorities has been shown to exist, and is of such a nature as to make proceedings futile or ineffective (Aksoy v. Turkey, § 52; Georgia v. Russia (I) [GC], §§ 125-59).

It also provides that the rule is inapplicable if

to use a particular remedy would be unreasonable in practice and would constitute a disproportionate obstacle to the effective exercise of the right of individual application under Article 34 of the Convention.[47]

- 139/140 -

In addition to the above, in September 2013 the Committee of Ministers adopted another guide on 'good practice in respect of domestic remedies'. This latter guide informs practitioners as to what may be considered as an efficient remedy in general and in particular situations.

As far as the ECHR's jurisprudence on ELR and interpretation of Article 35 § 1 of the Convention is concerned, its general principles were declared in Vučković and Others v. Serbia.[48] The ECtHR provided that the only remedies to be exhausted are those that relate to the alleged breach and are capable of redressing the alleged violation. The existence of such remedies must be sufficiently certain, not only in theory but also in practice, failing which they will lack the requisite accessibility and effectiveness: it falls to the respondent State to establish that these conditions are satisfied.[49] In the ECtHR's jurisprudence, there is no need to apply the rule on exhaustion with some degree of flexibility and without excessive formalism, given the context of protecting human rights[50] The rule of exhaustion is neither absolute nor capable of being applied automatically; in monitoring compliance with this rule, it is essential to have regard to the circumstances of the individual case.[51]

Recent case law suggests a coherence in ECHR jurisprudence on the matter of ELR. Below I will examine just three recent decisions taken in 2021 on certain Hungarian matters, stating that the jurisprudence on other jurisdictions is very similar.

In Kournikov[52] (2021), the City of London Police opened criminal proceedings against a British national on charges of embezzlement and money laundering. In 2010, Southwark Crown Court ordered the attachment of the bank accounts to which money had been transferred from the defendant's bank account. Relying on the European Convention on Cooperation in Criminal Matters, the London Crown Attorney's Office requested from the Hungarian authorities the attachment of the applicants' personal bank accounts and the bank account of the companies owned by one of the applicants, all held by Hungarian banks. The Hungarian courts - at first and second instance - ordered the attachment of the bank accounts, concluding that the conditions for attachment under the Code of Criminal Procedure were met. In front of the ECtHR, the Hungarian Government argued that - because the Hungarian authorities only assisted the British ones in the matter - the applicants could and should have appealed against the attachment directly before the British authorities. The ECHR noted that the Government failed to point to any specific remedies available in Hungarian law which the applicants should have used but did not. There it did not reject the claim for non-exhaustion of domestic remedies.

In another recent and important Hungarian case, in Vig[53] the ECHR in 2021 also rejected the government's argument that the applicant had not exhausted domestic remedies

- 140/141 -

because he had not pursued a review of the decision of the administrative court before the Kúria and did not bring constitutional complaints under section 26(1) and 27 of the Constitutional Court Act. The case concerned a police search carried out based on a notice from the National Police Commissioner, ordering them to carry out regular enhanced checks ('fokozott ellenőrzés') throughout the whole of the territory of Hungary 'on illegal migration routes leading to the European Union and to operate a screening network preventing illegal migration. Vig was searched in Budapest in the Sirály Community Centre although his actions did not give rise to any particular suspicion. After the search he appealed against the notice of police measures to the Independent Police Complaints Board and also lodged a complaint a complaint with the Constitutional Court under section 26(2) of the Constitutional Court Act, challenging the constitutionality of sections 30(1)-(3) and 31 of the Police Act. His complaint to the Constitutional Court was rejected as well as his appeals through the ordinary courts.

The applicant complained to the ECHR that the identity check and search had resulted from the terms of legislation rather than unlawful actions by the authorities (the police officers) being at variance with those provisions and challenged the underlying legislation, and not the police's compliance with those provisions. The ECHR established that the purview of administrative courts and judicial review by the Kúria would have been limited to a formal determination of whether the police powers were legally exercised.

Since the applicant did not argue that the stop and search measures used against him had not complied with the Police Act, judicial review proceedings before the Administrative and Labour Court would not have constituted a relevant or effective remedy in respect of his complaint under the Convention to redress his grievances stemming from the terms of the legislation itself. As a consequence, the remedy identified by the Government - an application for a review by the Kúria of the Administrative and Labour Court's judgment - would not have been an effective remedy either.

The ECHR also rejected the Government's argument that the applicant could have been expected to pursue an application for a review under section 26(1) and/or 27 of the Constitutional Court Act. The ECHR ruled that Vig did try to bring his case before the Constitutional Court. He first lodged a complaint under section 26(2) of the Constitutional Court Act, but that complaint was rejected and he also requested the administrative courts, unsuccessfully, to initiate proceedings before the Constitutional Court to establish that the Police Act was unconstitutional.

Under those circumstances, the ECHR found that the applicant had raised the complaint of the unconstitutionality of the legal provisions before the domestic courts, thus providing the domestic authorities with the opportunity to put right the alleged violation. The ECHR observed that it did not '...consider that the applicant was expected to pursue further constitutional avenues which were to remedy a judicial decision applying the legislation, unrelated to the applicant's complaint' (para 41.).

- 141/142 -

In LB v Hungary,[54] the Hungarian Tax Authority published the applicant's personal data, including his name and home address, on the list of tax defaulters on its website. An online media outlet produced an interactive map called 'the national map of tax defaulters' with the applicant's personal data.

The Government argued that the applicant could have requested that the data controller erase his personal data. If his request had been refused, he could have challenged this decision before the courts. The applicant submitted that the Data Protection Act offered no effective remedy.

The ECHR clarified the burden of proof regarding ELR. It stated that the burden of proof was on the Government to prove that a relevant and effective remedy was available both in theory and practice at the relevant time. Once this burden of proof is satisfied, it falls to the applicant to establish that the remedy advanced by the Government was in fact exhausted or was for some reason inadequate and ineffective in the particular circumstances of the case, or that special circumstances absolved him or her from the requirement.[55] The ECHR noted that, under the Data Protection Act, there was no prospect of LM having his personal data deleted from the tax defaulters' list. The ECHR (in para 30) did not accept that 'it would have served any purpose for the applicant to lodge a request for the erasure of his personal data' and did not accept it as effective in the particular circumstances of the applicant's case.

IV. Conclusions

The exhaustion of domestic remedies rule was transposed from international law at the birth of the European Convention on Human Rights, as well as into a host of other human right conventions. However, certain elements of customary international law have never been truly applied (such as the requirement of horizontal exhaustion) while others have disappeared over time as treaty law in particular has developed, and flexibility became the norm. Now, ELR in the ECtHR context is no more than a distant cousin of ELR under customary international law, even if the truth is that, following codification and progressive development work by the ILC, the exhaustion of local remedies rule is no longer what it was customary international law either. ■

NOTES

[1] '1. The Court may only deal with the matter after all domestic remedies have been exhausted, according to the generally recognised rules of international law...'

[2] PCIJ Series, 1938:28.

[3] Chittharanjan F. Amerasinghe, Local Remedies in International Law (Grotius 1990, Cambridge) 24.

[4] James R Crawford, Thomas D Grant, Local Remedies, Exhaustion of - in Encyclopedia of international law January 2007.

[5] Emer de Vattel, Le Droit des gens ou principes de la loi naturelle [reprinted edition Carnegie Institution Washington 1916]) vol 1 Reproduction of Book I and II of the Edition of 1958 page 309 para. 71.

[6] Greece v Great Britain [Judgment] PCIJ Rep Series A No 2, 7.

[7] Interhandel Case, 1959 I.C.J. at 27.

[8] P. 42, para. 50.

[9] J. Chappez, La règle de l'épuisement des voies de recours internes (Pedone 1972, Paris); G. Perrin, 'La naissance de la responsabilité internationale et l'épuisement des voies de recours internes dans le projet d'articles de la Commission du droit international' in Festschrift für Rudolf Bindschedler (Stämpfli, 1980, Bern) 271; Amerasinghe (n 3).

[10] The Interhandel Case 1959 ICJ Reports, 27: 'Before resort may be had to an international court in such a situation, it has been considered necessary that the State where the violation occurred should have an opportunity to redress it by its own means, within the framework of its own domestic legal system'

[11] Claim of Finnish shipowners against Great Britain in respect of the use of certain Finnish vessels during the First World War (Finland, Great Britain) (1934) 3 UNRIAA, 1497.

[12] LaGrand Case (Germany v United States of America) [Judgment] [2001] ICJ Rep 466 paras 21, 126.

[13] Sosa v Alvarez-Machain, 542 U.S. 692 (2004).

[14] Eric Engle, 'The Torture Victim's Protection Act, The Alien Tort Claims Act, and Foucault's Archaeology of Knowledge' (2003) 67 (501) Albany Law Review 504; Gregory G. A. Tzeutschler, 'Corporate Violator: The Alien Tort Liability of Transnational Corporations for Human Rights Abuses Abroad' (1999) 30 (359) Colum. Hum. RTS. L. Review 396.

[15] Symeon C. Symeonides, 'Choice of Law in the American Courts in 2002: Sixteenth Annual Survey' (2003) 51 (1) The Americain Journal of Comparative Law 48; Eric Gruzen, Comment, The United States as a Forum for Human Rights Litigation: Is This the Best Solution? (2001) 14 (1) Global Business & Development Law Journal 207, 232; Nancy Morisseau, 'Seen but Not Heard: Child Soldiers Suing Gun Manufacturers under the Alien Tort Claims Act' (2004) 89 Cornell Law Review 1263.

[16] Ikenna Ugboaja, 'Exhaustion of Local Remedies and the FSIA Takings Exception: The Case for Deferring to the Executive's Recommendation' (October 2020), 87 (7) University of Chicago Law Review 1937-1976.

[17] Draft articles on Responsibility of States for Internationally Wrongful Acts, <http://legal.un.org/ilc/texts/instruments/english/commentaries/9_6_2001.pdf> accessed 4 April 2021.

[18] Draft articles on Responsibility of States for Internationally Wrongful Acts, with commentaries 2001. 121. <http://legal.un.org/ilc/texts/instruments/english/commentaries/9_6_2001.pdf> accessed 4 April 2021.

[19] Alwyn Vernon Freeman, The International Responsibility of States for Denial of Justice (Longmans, Green 1938, London) 407; Chittharanjan Amerasinghe, 'The Formal Character of the Rule of Local Remedies' (1965) 25 Zeitschrift für Ausländisches Öffentliches Recht und Völkerrecht 445 et al.

[20] See Philip C. Jessup, A Modern Law of Nations (Cambridge University Press 1956) 104; García Amador, 'State Responsibility: Some New Problems' (1958) 94 Hague Recueil 449; Herbert W. Briggs, 'The Local Remedies Rule: A Drafting Suggestion' (1956) 50 (4) Americain Journal of International Law 921; Edwin M. Borchard, 'Theoretical Aspects of the International Responsibility of States' (1929) 1 Zeitschrift für Ausländisches Öffentliches Recht und Völkerrecht 237; C. Durand, 'La Responsabilité internationale des états pour déni de justice' (1931) 38 RGDIP 721. In front of the courts see: Panevetys-Saldutikis Railway Case (PCI], Series A/B, No.76, 47) and Case Concerning the Barcelona Traction, Light and Power Company, Limited: Preliminary Objections (Belgium v Spain), International Court of Justice, judgment of 24 July 1964, ICJ Reports 1964, 6.

[21] Draft articles on Diplomatic Protection 2006 Text adopted by the International Law Commission at its fifty-eighth session, in 2006 see also: <http://legal.un.org/ilc/texts/instruments/english/draft_articles/9_8_2006.pdf> accessed 4 April 2021.

[22] See AIDI, 1956, pp. 302 ss, especially p. 358); and see also in Whiteman, « Digest of international law », Washington, (1963-1973) 8, 778-779). see also D. Sulliger, « L'épuisement des voies de recours internes en droit international général et dans la Convention européenne des droits de l'homme » (Thèse, Université de Lausanne, Faculté de droit 1979, Lausanne) 18-21.

[23] Greece v United Kingdom [1952] ICJ 1 and also Wolfgang Weiß: Ambatielos case in Encyclopedia of Public International law April 2007.

[24] Article 41.1c of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights provides: 'The Committee shall deal with a matter referred to it only after it has ascertained that all available domestic remedies have been invoked and exhausted in the matter, in conformity with the generally recognized principles of international law. This shall not be the rule where the application of the remedies is unreasonably prolonged'), and its Optional Protocol in Article 5.2 provides: 'The Committee shall not consider any communication from an individual unless it has ascertained that: .(b) the individual has exhausted all available domestic remedies. This shall not be the rule where the application of the remedies is unreasonably prolonged'; Former Article 26 of the European Convention on Human Rights provided: 'The Court may only deal with the matter after all domestic remedies have been exhausted, according to the generally recognized rules of international law, and within a period of six months from the date on which the final decision was taken'; and Article 46.1 of the American Convention on Human Rights provides: 'Admission by the Commission of a petition or communication .shall be subject to the following requirements: (a) that the remedies under domestic law have been pursued and exhausted in accordance with generally recognized principles of international law..'). See also the African Charter on Human and Peoples Rights [Articles 50 and 56(5)].

[25] Cyprus v Turkey, 25781/94, 2001 ECHR 331 (10 May 2001), paras 82-102; Denmark v Turkey, 2000 ECHR 150, (5 April 2000), p. 34; and Cyprus v Turkey, 8007/77, Dec. 10.7.78, D.R. 13, p. 85.

[26] Guide to the "travaux préparatoires" of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights by Marc J. Bossuyt; preface by John P.Humphrey. Dordrecht; Boston: M. Nijhoff; Hingham, MA: Distributors for the United States and Canada: Kluwer Academic Publishers, c1987.

[27] See <https://www.echr.coe.int/LibraryDocs/Travaux/ECHRTravaux-ART26+27-CDH(70)30-BIL3774370.pdf> accessed 4 April 2021. See for example Draft Convention presented by the European Movement in Jul 1949: 'It is, of course, most important that the authority of national courts should not be impaired or undermined in any way by the establishment of the European Court of Human Rights...'.

[28] [GC], § 42.

[29] [GC], § 74; see also Kudta v Poland [GC], § 152.

[30] See also Demopoulos and Others v Turkey (dec.) [GC], §§ 69 and 97; Vučković and Others v Serbia (preliminary objection) [GC], § 69).

[31] Akdivar and others v Turkey, Application No.21893/93,16 September 1996, in Reports, 1996-IV, para. 65.

[32] Selmouni v France, 28 July 1999, in Reports, 1999-V, 175, para 74; Ankerl v Switzerland, 23 October 1996, in Reports, 1996-V, 1565, para 34.

[33] High Level Conference on the Future of the European Court of Human Rights Brighton Declaration The High Level Conference meeting at Brighton on 19 and 20 April 2012 <https://www.echr.coe.int/Documents/2012_Brighton_FinalDeclaration_ENG.pdf> accessed 4 April 2021.

[34] Protocol No. 15 amending the Convention on the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms, Strasbourg, 24. June 2013, Council of Europe Treaty Series - No. 213.

[35] Silvia D'Ascoli, Kathrin Maria Scherr, 'The Rule of Prior Exhaustion of Local Remedies in the International Law Doctrine and its Application in the Specific Context of Human Rights Protection' EUI Working Papers LAW 2007/02, 17.

[36] Ibid 17.

[37] Official Records of the General Assembly, Sixty-first Session, Supplement No. 10 (A/61/10).

[38] Rule 61 of the rules of the court <https://www.echr.coe.int/Documents/Rule_61_ENG.pdf> and <https://www.echr.coe.int/Documents/Pilot_judgment_procedure_ENG.pdf> accessed 4 April 2021.

[39] Practical Guide on Admissibility Criteria 4th edition.

[40] See page 21 of Practical Guide on Admissibility Criteria 4th edition.

[41] An institution folded into the ECHR in 1998.

[42] EUROPEAN COMMISSION OF HUMAN RIGHTS NOTE by the Human Rights Department concerning Article 26 of the Convention Strasbourg; September-1955, DH (55) U Or. Fr. <https://www.echr.coe.int/Documents/Library_TP_Art_26_DH(55)11_ENG.pdf> accessed 4 April 2021.

[43] Practical Guide on Admissibility Criteria 4th edition.

[44] The practical guide in para 71 refers to a number of ECtHR cases in this respect such as Castells v Spain, § 32; Ahmet Sadik Greece, § 33; Fressoz and Roire v France [GC], § 38; Azinas v Cyprus [GC], §§ 40-41; Vučković and Others v Serbia (preliminary objection) [GC], §§ 72, 79 and 81-82; Gäfgen v Germany [GC], §§ 142, 144 and 146; Karapanagiotou and Others v Greece, § 29; Marić v Croatia, § 53; Association Les témoins de Jéhovah v France (dec.); Nicklinson and Lamb v the United Kingdom (dec.), §§ 89-94).

[45] A body folded into the ECHR in 1998.

[46] See Ph. Couvreur, L'épuisement Des Voies De Recours Internes Et La Cour Europeenne Des Droits De L'homme: L'arret Van Oosterwijck Du 6 Novembre 1980. in RBDI 1981-82 <http://rbdi.bruylant.be/public/modele/rbdi/content/files/RBDI%201981%20et%201982/RBDI%201981%20et%201982%20-%201/Etudes/RBDI%201981-1982.1%20-%20pp.%20130%20%C3%A0%20171%20-%20Philippe%20Couvreur.pdf> accessed 4 April 2021.

[47] Veriter v France, § 27; Gaglione and Others v Italy, § 22; M.S. v Croatia (no. 2), §§ 123-25.

[48] Preliminary objection [GC], nos. 17153/11 and 29 others, §§ 69-77, 25 March 2014.

[49] McFarlane v Ireland [GC], no. 31333/06, § 107, 10 September 2010.

[50] Ringeisen v Austria, 16 July 1971, § 89, Series A no. 13.

[51] Kozacioğlu v Turkey [GC], no. 2334/03, § 40, 19 February 2009.

[52] Kosurnyikov v Hungary (Application no. 59017/14).

[53] Vig v Hungary (Application no. 59648/13).

[54] L.B. v Hungary (Application no. 36345/16).

[55] Tiba v Romania, no. 36188/09, § 21, 13 December 2016.

Lábjegyzetek:

[1] The author is Associate Professor, ELTE Law School, Department of Public International Law.