András Zs. Varga: Beyond Rule of Law (IAS, 2013/2., 117-127. o.[1])

1. Why is useful to look behind the principle of rule of law?

The second decade of the 21st Century started with a series of enthusiastic events from the point of view of a public law researcher in Hungary due to the will of the Parliament elected in 2010 to construct a new Constitution.

The former constitutional order of Hungary was established after the negotiations of the National Roundtable in 1989 (the three 'sides' of the 'round' table had been composed by the leading communist Hungarian Socialist Party of Workers - HSPW -, the group of the so called opposition movements and the third grouping of other social associations). The target of the negotiations was to draft the inevitable legal texts (adopted later by the National Assembly of the People's Republic of Hungary composed mostly and overruled by HSWP) necessary to the free elections. Although in the first phase of negotiations the 'opposition' objected to formulate a new constitution (since the negotiations had no political legitimacy, the leading HSWP was considered to be non-legitimate), the outcome of the negotiations was practically a new text which formally was adopted as Act XXXI of 1989 on Modification of the Constitution. Hence the official title of the Constitution just modified remained Act XX of 1949, the basic act of the transition and of the new Republic was formally an old and illegitimate statute.[1] This characteristic nature of the old Constitution was well-known: its Preamble had limited its effect for an indefinite but not infinite time, until the adoption of a new Constitution. Beyond any doubt, the old Constitution of Hungary was an interim Constitution.

- 117/118 -

The new constitution called Basic Law of Hungary was ready-made for Easter of 2011. Formal validity of the statute couldn't be questioned hence it was adopted by the Hungarian Parliament as the constituent power of our country (within the context of both the former and the new constitution), the procedural law-making rules of the old constitution were respected meticulously, the text was signed by the Speaker of the Parliament and the President of the Republic of Hungary, and it was published in the Official Gazette of Hungary. However, the ink of the President wasn't dried on the Basic Law when a long debate started against this new constitution. The opposition parties were and still are not pleased with its text and its 'ethos', while different international bodies as the European Parliament or the Venice Commission and a number of non-Hungarian academics formulated certain objections regarding the connection of the new text to the Historical Constitution of the former Hungarian Kingdom, the regulation of the rights of human foetus, the rules regarding marriage and family, the new organisation and administration of the judiciary etc.

This paper cannot serve as an apology for the new Basic Law, it tries only to trace some theoretical features of the public law thinking of present time which may help in understanding the critical approaches. As we see if we look around, there is a growing interest within the European academic society in the future of constitutions. One of the last events regarding this topic was the W G Hart Legal Workshop 2010[2] addressed to theory and practice of the comparative aspects on constitutions what suited perfectly the excited status of the 20 years old interim[3] Constitution and the challenged new Basic Law of Hungary.[4] A British survey of the uncertain situation around the national constitutions of Europe was given by Professors Nicholas Bamforth and Peter Leyland[5] in 2003. Another new volume confirming the growing interest and the change of approaches is a recent comparative study based on a set of essays edited by Professors Dawn Oliver and Carlo Fusaro.[6] All of these studies try to look behind the traditional concept of the principle of rule of law and to discover its new dimensions.

- 118/119 -

2. Rule of law as a set of principles governing Governments

Rule of law is usually understood as a set of principles founding a hierarchical order of legal regulations with the Constitution on its top (prohibition of retrospective effect of legal acts, guaranties of fundamental rights and freedoms, legal regulation of state activities, judicial control of administrative acts, presumption of innocence of citizens, democratic legitimacy of government, separation of branches of state, equality of people) which are essential for a state and its legal order if it wants to be accepted as non-arbitrary, non-dictatorial. Components of this set of principles are rooted within the heritage of the main legal families what can be illustrated by some examples as the French principle of constitualism, the English rule of law and the German Rechtstaatprinzip.

The French principle of constitualism has in its focus a system of administration (as part of the Executive) separated from any other institution of state and from the ordinary courts within them. Administration as activity of the executive does not remain without judicial-type of control, the special form of administrative courts with the Conseil d'Etat on their top are established to limit and guarantee the proper and legal activity of administrative bodies.[7] The English idea of rule of law became one of the most important concepts of the common European values. Following Albert Venn Dicey rule of law is realised if the powers of the Executive are not arbitrary, due to legal regulations binding the authority of the Cabinet of Ministers and of other administrative bodies, if the ordinary courts of law have jurisdiction over all individuals and all state bodies (what means practically lack of separate administrative law courts) and if general principles of constitutional law depend on the constitutional conventions.[8] From the extremely diverse legal literature of the Rechtstaatprinzip we chose the approach of Robert von Mohl who thought that a state built on law (Rechtstaat) is governed by reasonableness; it sustains its legal order, gives opportunity for its citizens to reach their reasonable goals and guaranties equality before the law and in exercise of fundamental rights and freedoms.[9]

3. Rule of law as European standard of government

If we try to make a synthesis of the consequences of the rule of law on a specific state, we probably are not wrong if we say that the two main requirements of government from the point of view of a lawyer are legality and legitimacy.

Legality in first approach is not else, than the exterior characteristic of the constitutional order. If we examine it from the level of norm-positivism, then a plain

- 119/120 -

answer can be given for the legality of the government: any change of norms and any other activity of the state shall observe the previously accepted norms which still are in force. It is not difficult to recognize that this primary approach carries a historical constraint: any constitutional change may define itself only compared to the earlier order of law, and no activity of State may ignore the requirement to observe formal legality and to be just as appears in the formula of Radbruch). [10]

This approach is built on the equality of the subjects-at-law (people), their equal dignity, or - according to other formulations - the general personality right, or the right for the free development of the personality, shortly the right of self-determination.[11] We need to say that without the recognition of personal dignity constitutionalism and the order of law may be an appearance masking the sheer physical power but not the basis of law. In the absence of guarantees of personal dignity, the system of norms is only "like" law. Recognition of the person's dignity deriving from his nature is the fundamental, universal, objective and necessary requirement of law. On a final row, this is not else than the recognition of the natural substance of law.[12]

As regards political legitimacy nowadays we consider national sovereignty to be the necessary component of constitutionalism. Legitimacy in this notion is not else than the subjective side of the constitutional order, it is practically the nation's decision that accepts this order and the State activity based on it. On the one hand it is the source of the power (its abstract carrier), in other words the legal basis of sovereignty. No Constitution would be able to supply the role of the social minimum without the mutual understanding based on "togetherness" having been experienced at the moment of constituting. More than rational acceptance is needed for this, namely some kind of emotional or rather spiritual identifying: the faith that life is managed in a good manner and the basis of this is "Our" constitutional order. [13] In other words: without solidarity the order of the constitution and of law may not be the basis of the commonly accepted law. Solidarity inevitably carries the historical definiteness of the constitutional order: it does not exist a priori, it can be only a really existing nation's constitutional order.

Within the absolutistic organisation of state both legality and legitimacy were vested on the sovereign. In constitutional states, where a third, organisational requirement of government is separation of powers, two separate branches are delegated as

- 120/121 -

guardians of the main requirements: Parliament as possessor of legislative power is holder of legitimacy while courts are watching through their jurisdiction legality of governmental activity.

4. Rule of law and governmental practice

Practical governmental activity is fulfilled by the third branch, the executive power. Thus - again from the point of view of a lawyer - the practical government, the activity of the executive power, controlled by the other two branches is "good" enough if it is legal and legitimate: if does not commit any infringement of law and if it is not contrary to will of people (or of 'nation', if we want to be more ceremonial). However, being legal and legitimate it is not enough for the executive power hence it has as role (or task) to execute the laws and the will of people. Executive activity has its own measure controlled by its effectiveness. Description of effectiveness of the executive - or more precisely effectiveness of public administration - has a huge literature. In lack of space and for the purposes of this presentation it is enough for us a simple and trivial definition: if law is observed, consequently the normative and practical governmental acts are valid and public will is satisfied, the effects of government are positive. In the opposite case, if governmental acts are void, consequently nullified by courts or these acts are not accepted by people, their effect is negative, the aim of activity is not reached. In brief the activity of the executive branch of state has its own requirement beside legality and legitimacy: and this is efficiency.

If we try to summarise the requirements of government in a constitutional state based on separation of powers, the triangle of legality, legitimacy and efficiency cannot be avoided. All of these are focused on the executive power: if a government wants to be good, the executive shall act legally (under the control of courts), taking into account the legitimate will of people (under the control of the Parliament) and being efficient (otherwise it will lose its mandate even if being legal and formally legitimate).

In reality manifestation of the triangle of legality, legitimacy and efficiency is not simple. The Parliament and the courts are not only forms of control of the executive, but their activity (based on their special points of view: legality and legitimacy) are obstructing efficiency. If there is not enough weight on the shoulders of the executive branch, we can enhance this aspect: legality and legitimacy are not concordant in restraining efficiency of the executive power but they are doing this from antagonistic directions. In other words legality and legitimacy are not simply brakes of efficiency but both of them are acting against the other. Being legal, legitimate and efficient is almost impossible for an executive power, or in a broader perspective: for a government. One edge of the triangle will be overweight.

- 121/122 -

5. Legality today and its boundaries

In our culture based on rule of law it seems that legality is this overweight edge of government-architecture presented above. Of course, one may say, but sometimes we face not only overweight of legality but the strong restriction of efficiency due to activity of Constitutional Courts, the European Court of Justice or of the European Court of Human Rights. In some cases the point of view of legitimacy is completely ignored. Explanation of this situation is quite simple: courts with the final and noncontestable power of interpretation of law are not only forums of individual legal debates but in the same time courts appear as definitive and sole guardians of the executive power or in a broader sense, of the whole government. If courts and only courts rule on activity of the executive, than any other aspects of responsibility or accountability like political reasonableness, economical profitability or social acceptance are of secondary importance[14] and the mere standard will be formal legality. If we look around this is the appearance of legality today: legality is understood in this manner.[15]

However, if we try to look into deep layers of the nature of legal norms and of jurisdiction, exclusiveness of formal legality will rise certain doubts.

The actual paradigm of interpretation of norms is built on the principle of legal certainty and on the theory of completeness of legal norms, or - as appears in constitutional rulings - completeness of the Constitution. For our purposes it is sufficient the analysis of completeness of constitutions. Completeness within this theory means that any legal question risen any time can - and shall - be answered by - and only by - interpretation of the rules of Constitution, there is no need of other, extra-constitutional principles, rules, values, topics. The most prestigious supranational courts and some national constitutional courts use completeness understood is this manner as permanent guideline of their jurisdiction.

The problem with completeness as fundamental guideline of interpretation of law is that requires the presumption that law as system of norms is consistent (without internal logical contradictions). But we learned in the last century of scientific thinking that consistency of any logical system and objective certainty of any deduction is illusion.

After the centuries of scientific positivism the relation of uncertainty of Heisenberg throw off the general belief in unquestioned causality while incompleteness theorems of Gödel raised doubts regarding efficiency of logical deductions. The relation of uncertainty had been found applicable within historical and economic methodology

- 122/123 -

by John Lukács[16] during the 1960's and by George Soros[17] in 2008. Taking into account the well-known properties of legislation and of jurisdiction, paying special attention to the distorting effects of substantive and procedural law of evidences and the behavioral rules of decision-makers within these effects it can be proved that these axioms of mathematics and physics, uncertainty and incompleteness apply law.

The simplest demonstration is the Raymond Smullyan's contradiction of Knights and Knaves. In a fictional island where two types of citizens live, Knights, who always tell the truth and Knaves who always lie. If a traveller arrives to this island and meets a local citizen, this citizen may not tell him that he (the citizen) is not a Knight. If he is a Knight he must tell the true while the sentence "I'm not a Knight" is false, and inverse, if he is a Knave he must lie while the sentence "I'm not a Knight" is true. Both solutions lead to contradiction. The story can be combined to be less trivial: the citizen cannot formulate the next statement to the traveller: "You will never believe that I am a Knight" and so on.[18]

It can be easily apprehended that if incompleteness is an inevitable character of the most simple logical systems, consequently there are statements which cannot be either proved or denied, in more complex systems as law is with its millions of legal norms is much more incomplete. Another consequence of Gödel's theorem is that even the theoretical completeness of a logical system cannot be proved.[19] Completeness of law is more than an uncertain presumption, it is a real fictio iuris:[20] a characteristic which is accepted as truth when we now that it is false.

For demonstration of legal uncertainty we don't have such a simple model like Knights and Knaves, but the well known rules of jurisdiction already mentioned like law of evidences and the behavioral rules of decision-makers confirm that there is no absolutely objective way of obtaining true facts in a procedure. The decision-maker 'enters the story', and the state of facts of a legal decision is influenced by subjective issues, first of all by the assessment of the decision-maker. The investigator is involved into the investigation.

Consequences of uncertainty and incompleteness may influence the legal thinking regarding instruments of control, system of remedies and of procedural rules. Coming back to our issue, we should conclude that the incomplete system of law considered to be complete and the uncertain decisions of jurisdiction considered to

- 123/124 -

be certain are at least disturbing. If we insist that law and jurisdiction are complete (consistent) and certain while they are not, we accept the inevitable arbitrariness of court interpretations and decisions. The illusion leads to tautology: a final decision of courts in very subtile legal questions is taken without stable logical support. A final decision of a court is true, legal and correct only because it is the final decision of a court.

6. What is beyond rule of law?

If we try to answer the question what is the consequence of our findings regarding the fictio iuris of completeness and certainty we could say that if there is no counterbalance of the free-interpretation of law by courts, the outcome of the control of governmental activity will be as arbitrary as the ex iure divinum government of an absolutely uncontrolled sovereign.

We should consider that good government needs something balancing the ultraestimation of the principle of rule of law. Tautology of rule of law being the only standard of rule of law cannot be kept on. This balance cannot be the executive, otherwise we get another tautology: the controlled institution cannot serve itself as balance of the controller institution. In want of better we should use the legislative branch, holder of legitimacy as counter-balance. Our hypothesis is that one or a small bunch of fundamental and in the same time not formal but substantive principles could help, even if this approach today is not "orthodox". Something like the roman rule: "salus polpuli suprema lex esto"[21] or its Christian (canonical) version: "salus animarum suprema lex esto" could help us.[22] One of the modern paraphrase could be "public weal respecting personal dignity and human rights is the fundamental, inviolable and incontestable criterion of good government".

of course, we need a new view of law and an appropriate procedure of public law implementing this substantive principle. The new view should consider law as something what is more and in the same time less than appears in the contemporary mainstream perception: law is more than an interesting playground of lawyers and less than an absolute and mere set of rules controlling the everyday life. Its rules should be perceived as description of the expected behaviour of people and not being neutral.

The appropriate procedure of public law implementing the substantive principle of public good could be a permanent dialogue between the legislation and the judiciary. This approach, of course, presupposes that the legislator or in special cases the holder of constituent power does not commit heresy if - taking into account the interpretation of courts - tries to pull the ground out from under the courts by amendments of law or of the Constitution.

- 124/125 -

A proper meaning of good government is more than a bow to an arbitrary interpretation of law. One may say that in this approach law looks only like an instrument of government. We will not deny this heterodoxy: if the deduction presented above is correct, the positive law as product of governmental legislation is an instrument, indeed. Some legal rules and fundamental principles are of course more than instruments, but if we want to find this non-instrumental legal stratum we should enter - or perhaps we had already entered - the territory of natural law.

7. "Postamble"

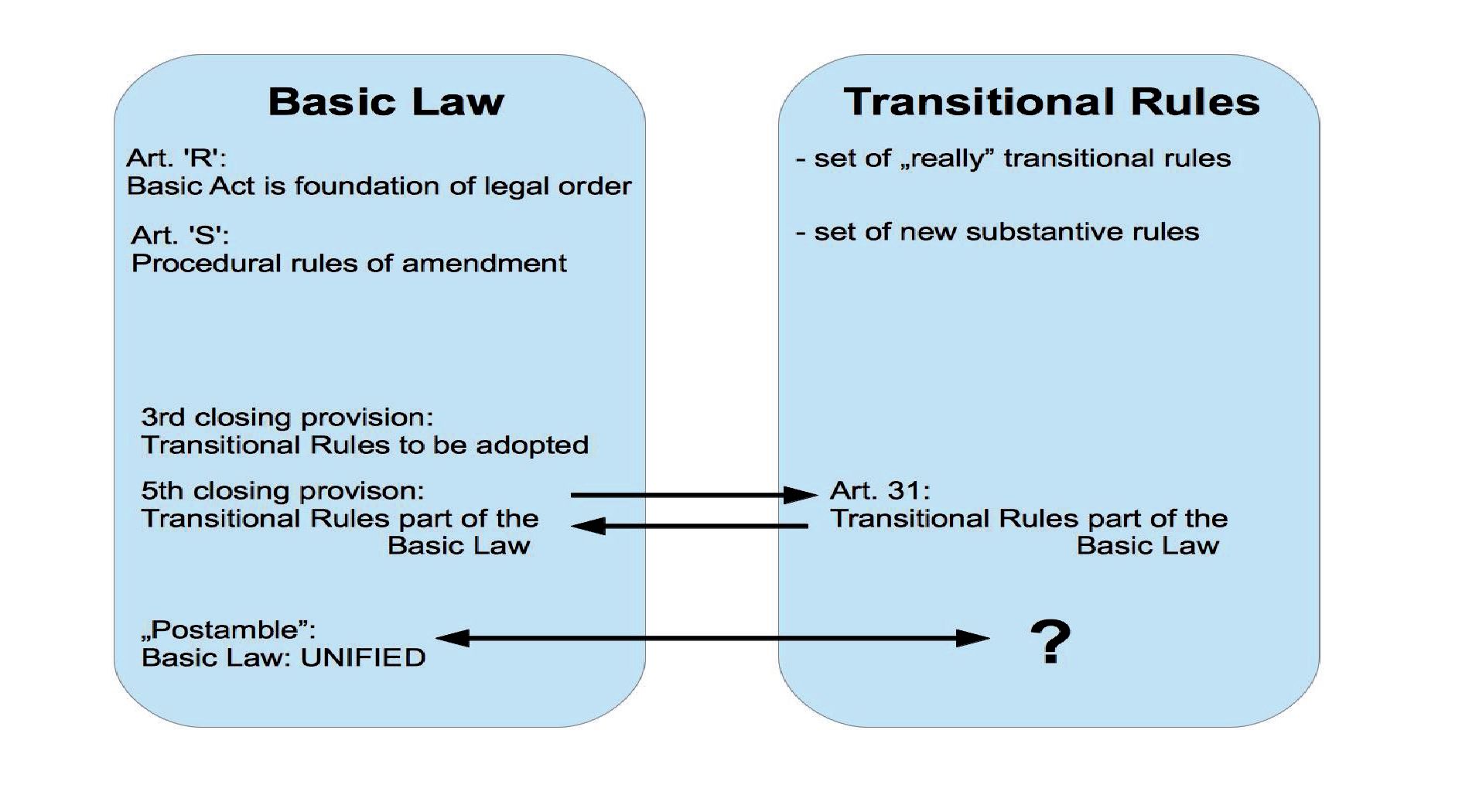

Only some days after the presentation of this paper[23] the Hungarian Constitutional Court nullified a great part of the Transition Rules of the new Basic Law.[24] The Transition Rules were adopted only some days before the Basic Law entered in force (1[st] of January, 2012) by the Hungarian Parliament as constituent power of Hungary. Creation of the Transition Rules was allowed by the 3[rd] closing provision of the Basic Law ("Parliament shall adopt the transition rules related to this Basic Law in a special procedure defined in point 2"[25]).

The controversial situation was originated in the fact that the Parliament adopted new substantial and not only transitional regulations within the Transitional Rules and Section (2) of Article 31 of the Transitional Rules stated that the Transitional Rules are part of the Basic Law. There was no similar provision within original text of the Basic Law: it prescribed only adoption of Transitional Rules without any declaration of "being part". After the first debates on the nature of Transitional Rules the Parliament amended the Basic Law (First Amendment on 18[th] of June 2012). In conformity with Article 'S' of the Basic Law (regulating adoption of a new Constitution and amendment of the Basic Law) the modification by the First Amendment was built in the text of Basic Law ("incorporation") as a new 5[th] closing provision saying that: "The Transitional Rules of the Basic Law adopted (on 31[rd] of December 2011) in conformity with the 3[rd] closing provision are part of the Basic Law". The last sentence of the Basic Law, the "Postamble" remained unchanged: "We, the Members of the Parliament elected on 25 April 2010, being aware of our responsibility before God and man and in exercise of our constitutional power, hereby adopt this to be the first unified Fundamental Law of Hungary."

Due to the First Amendment mentioned above the Basic Law and its Transitional Rules took the shape of a "catamaran":

a) the "Postamble" stated that the Basic Law is unified,

- 125/126 -

b) after the First Amendment the 5[th] closing provision stated that the Transitional Rules are "part of ' the Basic Law and Article 31 of the Transitional Rules stated the same,

c) the Transitional Rules were not incorporated within the Basic Law but they are two separated bodies of the Hungarian legal order, while

d) Article 'R' of the Basic Law rules that the Basic Law "shall be the foundation of the legal system of Hungary".

The Constitutional Court examined the legal nature of Transitional Rules on the request of the Commissioner for Fundamental Rights and "found" that the new substantive regulations of the Transitional Rules are not in conformity with the Basic Law, consequently the Court nullified them (with some exceptions) with retroactive effect, from 31[st] of December 2011.

The most important arguments of the Constitutional Court were that

i) although the Hungarian Parliament adopted the Transitional Rules in its capacity of constituent power,

ii) and although the First Amendment declare that the Transitional Rules are part of the Basic Law,

the Transitional Rules "containing" the new substantive regulations cannot be accepted as sources of Hungarian legal order, because

1) the "Postamble" states that the Basic Law is unified, consequently it cannot have an "external" substantive part as Transitional Rules,

2) new substantive regulations can be amended to the Basic Law only in conformity with procedural rules of Article 'S', but after such an amendment the new regulations should be incorporated into the text of the Basic Law,

- 126/127 -

3) in its shape of double bodies some regulations of the Basic Law can be deactivated by new and new amendments of the Transitional Rules which can serve as "slide law" against the "completeness" of the Basic Law.

Arguments of the Constitutional Court are correct, light and comprehensible. There is no doubt, this decision serves the protection of rule of law understood as was described in the first half of this paper.

However, based on similarly correct, light and comprehensible counter-arguments - some of them have appeared within the official justification others have been attached as particular parallel views and dissenting opinions of some justices[26] - the decision of the Constitutional Court could have been the opposite: the Transitional Rules could have been accepted as separated (non-incorporated) parts of the Basic Law hence the Hungarian Parliament adopted them in its capacity of constituent power as part of the Basic Law.

The Constitutional Court strengthened the completeness of the Basic Law but - at least we think that - the arbitrariness of the decision cannot be denied.■

JEGYZETEK

[1] See András Jakab: The Republic of Hungary. Commentary. In: Rudiger Wolfrum - Rainer Grote - Gisbert H. Flanz (eds.): Constitutions of the Countries of the World. Release 2008-2, New York, Oxford University Press, 2008. 8-9.; for approach of László Sólyom see Irena Grudzinska-Gross (ed.): Constitualism in East Central Europe. Bratislava, Czecho-Slovak Committee of the European Cultural Foundation, 1994. 51.

[2] London, Institute of Advanced Legal Studies, see (page downloaded on December 23, 2012) ials.sas. ac.uk/research/hart/wgh_legal_workshop_2010.htm

[3] "In order to serve peaceful transition to a state under rule of law realizing political pluralism, parliamentary democracy and social free-market economy, until the adoption of the new constitution the National Assembly recognises the text of Constitution of Hungary as follows" - states the Preamble (amended by Act XXXI of 1989 on Modification of the Constitution) to Act XX of 1949 on the Constitution of the Republic of Hungary.

[4] See the short but comprehensive study by Jakab (2008) op. cit. 1-48

[5] Nicholas Bamforth - Peter Leyland (eds.): Public Law in a Multi-Layerd Constitution. Oxford, Hart Publishing, 2003.

[6] Dawn Oliver - Carlo Fusaro (eds.): How Constitutions Change. Oxford, Hart Publishing, 2011.

[7] See Szigeti, Péter - Takács, Péter: A jogállamiság jogelmélete. [Legal Theory of Rule of Law]. Budapest, Napvilág, 2004. 171-211.

[8] Albert Venn Dicey: Introduction to the Study of the Law of the Constitution. (10th ed.) London, Macmillan, 1959., Indiannapolis, Liberty Classics, 1982.

[9] Robert von Mohl: Jogállam. ['Rechtstaat'] In: Takács, Péter (ed.): Joguralom és jogállam. [Rule of Law and Rechtstaat] Budapest, ELTE, 1995. 32-36.

[10] The importance of the Radbruch's formula see later.

[11] See decision 8/1990. (IV. 23.) AB (ABH 1990, 42). This decision considers - as decisions of the Hungarian Constitutional Court often do - jurisdiction of the German Verfassungsgericht, US Supreme Court or House of Lords.

[12] We think that Radbruch was "smuggling back" (without a direct will) natural law behind the legal positivism. This approach is not unique in Hungary, see Frivaldszky, János: Klasszikus természetjog és jogfilozófia. [Classical Natural Law and Philosophy of Law] Budapest, Szent István Társulat, 2007. 412-418.

[13] This is clear in the first words of the US Constitution: "We the people...". Significance of "We" and inevitable role of "membership" is presented expressively and clearly by Roger Scruton: The Need for nations. London, Civitas, 2004. See another approach of "We" (as substance of social harmony) in Francis Fukuyama: The Great Disruption. New York, Free Press, 1999.

[14] See Carol Harlow: European Government and Accountability. In: Bamfort-Leyland (2003) op. cit. 79-102.

[15] In Hungary: Sólyom, László: Az alkotmánybíráskodás kezdetei Magyarországon. [Beginnings of Constitutional Jurisdiction in Hungary] Budapest, Osiris, 2001.; Csink, Lóránt - Fröhlich, Johanna: Egy alkotmány margójára. [On the Margin of a Constitution] Budapest, Gondolat, 2012.

[16] See John Lukács: The Historical Consciousness. The Remembered Past. New Brunswick (USA) -London (UK), Transaction Publishers, 1968.

[17] See George Soros: The New Paradigm for Financial Markets. London, Public Affaires, 2008.

[18] See: Raymond Smullyan: Gödel 's Incompleteness Theorems. oxford, oxford university Press, 1992. See also Julian F. Fleron - Philip K. Hotchkiss - Volker Ecke - Christine von Renesse: Discovering the Art of Mathematics. Mathematical Reasoning- Knights and Knaves. (28 September, 2010) artofmathematics.wsc.ma.edu.

[19] See Douglas R. Hofstadter: Gödel, Esher, Bach: an Eternal Golden Braid. Basic Books, 1999. 53-54.

[20] In other words: due to incompleteness we apply conclusions in order to demonstrate a proposition wich cannot be closed into formal systems, see Hofstadter (1999) op. cit. 86-87.

[21] Cicero: De Legibus, Liber Tertius, 8.

[22] Canon no. 1752 of the Codex Iuris Canonici.

[23] The paper was presented at the "Jó kormányzás, jó kormányzat, jó állam" [Good Governance, Good Government, Good State] Conference of the Faculty of Law and Political Sciences of the Pázmány Péter Catholic University (Budapest, Hungary, 19[th] of December, 2012).

[24] Decision no. II/2559/2012 of 28[th] of December 2012.

[25] The reason of reference to "point 2" is that the Basic Law and the Transitional Rules were adopted when the interim Constitution was in force. Point 2 - or the 2[nd] closing provision - prescribed the respect of the procedural rules of the interim Constitution.

[26] Parallel views - consenting with the merit of the decision but based on different arguments - were attached by Justice András Holló and Justice István Stumpf while dissenting opinions - negating even the merit of the decision - were formulated by Justice István Balsai, Justice Egon Dienes-Oehm, Justice Barnabás Lenkovics, Justice Péter Szalay and Justice Mária Szívós.

Lábjegyzetek:

[1] A szerző professor (PPKE JÁK)