András Zs. Varga: Personal dignity and community (IAS, 2010/4., 167-173. o.[1])

I. First considerations regarding the legal notion of "dignity"

Aspects of dignity and community can be considered within the context of several sciences. If we try to draft some basic considerations regarding their legal character we should start from a practical definition of law.

The definition must be practical because the notion of law looks to be a permanent and inexhaustible topic of the legal thinking. The well known formula of Celsus "ius est ars boni et aequi", or "law is the art of goodness and of fairness" (Dig. 1.1.1.pr.) is a pathetic manifest of the inter-personal function of law but it can hardly be understood as an exact paraphrase. In everyday use law is understood as

a) a complexity of compulsory

b) behavior rules

c) governing attitude of individuals and their groupings

d) created or at least recognized and

e) in extreme situations enforced by the State.[1]

This notion of law will not give answer to all theoretical questions arising, it considers for instance without saying existence and character of the State, but gives emphasize to the most important attributes of law. First of these attributes is that law is composed by behavior rules. This consideration will be give importance by the analytical and synthesized legal description of personal dignity.

Coming back to personal dignity one of the first considerations should be regarding the connection between the person and its dignity. First phrase of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, especially of its Preamble underlines that

- 167/168 -

"recognition of the inherent dignity and of the equal and inalienable rights of all members of the human family is the foundation of freedom, justice and peace in the world". Based on this recognition declares in the first Article that "All human beings [endowed with reason and conscience[2]] are born free and equal in dignity and rights." If the grammatical structure of this sentence was other, if it was saying that: "All human beings have or are entitled with equal dignity", the interpretation would have been that dignity is a simple legal notion (like property, contract, crime or full age), created by legislation or court jurisdiction, which is "added" by law to the person. In other words, in this context the person would have been understand as a natural, extra-legal fact, and dignity as one of its legal qualities. But the Universal Declaration does not use "have" or "being entitled" as predicates, its formulation is explicitly different: the Declaration says that human beings are born equal in dignity.

The two simple words: "are born" leads to a fundamental change in the interpretation of the Article. If dignity is congenitally linked to the person, it is substantially untouchable by positive law.

II. Dimensions of dignity

Untouchableness of dignity does not mean that positive law may not regulate its appearance in different legal situations, legal relations, but untouchableness has a certain consequence: legal interpretation of dignity cannot lead to different levels of dignity related to different individuals. Substantial untouchableness does mean that dignity is absolute irrespectively of any subjective or objective circumstances.

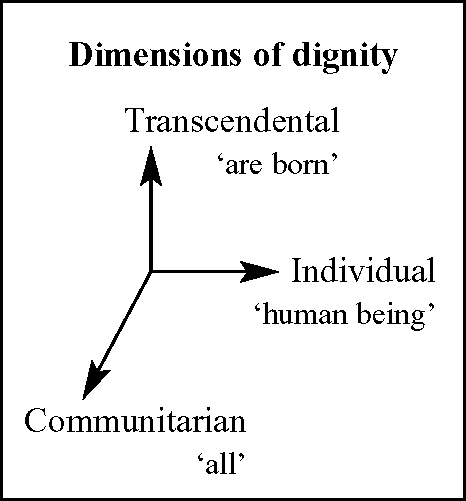

Despite of its untouchable character dignity needs legal interpretation otherwise it cannot be protected by law. As a first step to interpretation the different dimensions of dignity are to be fixed. Like any institutions of law, dignity can be considered separated from other institutions or within the system of norms. These two approaches give the two basic dimensions, one of them projects dignity to its holder, the individual human being, the other tries to understand the effects of the absolute character of dignity to legal relations, in other words the manifestation of dignity in the community. The third dimension is the transcendental one.

This third dimension needs some explication. One of our former considerations was that the formulation of Article 1 of the Universal Declaration, individuals being born free and with equal dignity, makes dignity untouchable. This character can itself be understood as a transcendental feature.

A human individual being born has of course many practical consequences: it means that someone, a new person exists, it means that it has or produces physiological phenomena, it wears genetic and genealogical affections. All these attributes are perceptible and

- 168/169 -

capable for natural science. Different branches of positivistic social science - and positivistic legal theory within them - can also formulate conclusions based of the fact that a new person, a new member of the society was born.

Contrarily to the factual attributes of being born, the untouchable dignity has no physical or social handholds. Natural and positivistic social scientific methods are applicable only if the analyzed phenomenon is measurable or at least comparable to other phenomena. It is out of question that a human being as member of society can be understood as a statistical data, and in this approach may be subject of social analysis, but this way will not help us in understanding dignity, since being "only" a statistical data is perfectly contrary with being born with dignity. Just the unique and absolute character of dignity is the plus value which elevates dignity from the individual-communitarian plan of thinking of the positivistic sciences. The question 'why has anyone equal and absolute dignity' cannot be answered on positivistic grounds. The right answer is simple and factic: 'because he or she was born'.

Transcendental dimension of dignity has - of course - a rich set of theological considerations,[3] but these are not within the context of this discourse. However transcendental dimension also has implications on interpretation of legal notion of dignity, which will be mentioned later. At this stage we are leaving transcendentalism in order to rough in the two other dimensions.

Individual dimension of dignity is much more plausible since it has in the focus the human person alone, separated from other individuals. If we want to understand this dimension of dignity, we should proceed using analytical method: not the unique exclusivity of dignity but its components are to be identified. The output of this method is a static - theoretically important but right artificial - deconvolution of dignity, a set of rights and specific freedoms. Picturesquely said it is like the rainbow created from the natural light by a prism.

Communitarian dimension is less spetacular. This is the traditional approach of law, which does not dealing with anatomy of dignity, but looks towards dignity in its dynamical action, in the interference of different individuals having the same equal dignity.

All these three dimensions follow from the formulation of the Universal Declaration, which mentions freedom, dignity and rights of 'all' (communitarian dimension) 'human beings' (individual dimension) due to the fact that they 'are born' (transcendental dimension).

III. Different alterations of dignity in legally binding texts

The only failure of our train of though is that Universal Declaration is not a legally binding document. Of course its impact on compulsory regulations is easily recognizable, but unfortunately formulation of legally binding text is not perfectly the same.

- 169/170 -

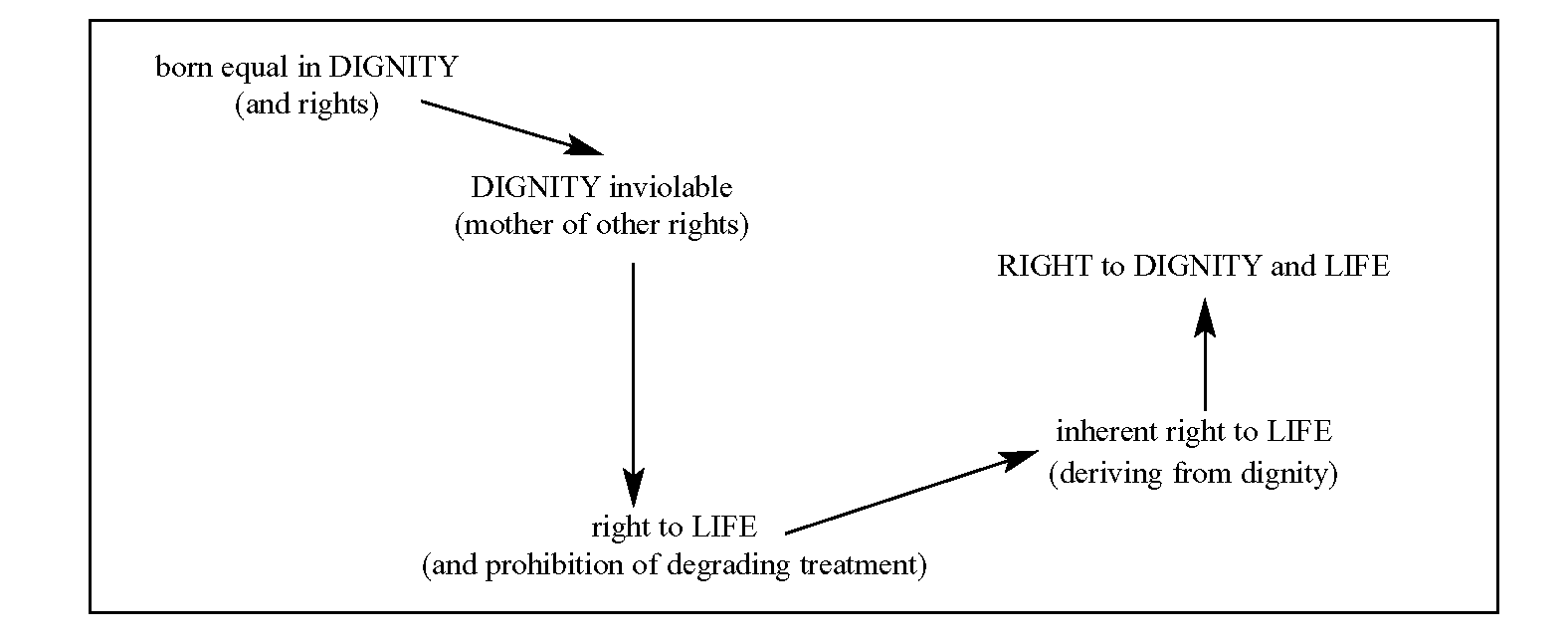

The regulation of Article 1 appeared in less than half a year in Article 1 of the Basic Law of the German Federal Republic (Grundgesetz für die Bundesrepublik Deutschland) as follows:[4] "(1) Human dignity shall be inviolable. To respect and protect it shall be the duty of all state authority. (2) The German people therefore acknowledge inviolable and inalienable human rights as the basis of every community, of peace and of justice in the world. (3) The following basic rights shall bind the legislature, the executive, and the judiciary as directly applicable law. " The Grundgesetz does not use the "are born" formula, but declares the inviolableness of dignity and together with dignity the inviolableness and inalienableness of human rights. The common opinion on this link between dignity and specific rights is that dignity (sometimes understood as personal autonomy or right to free development of personality which appears in the next Article of the Grundgesetz) is the "mother" of all other fundamental rights.[5] On the other hand untouchableness - the transcendental dimension - of dignity is manifested in the regulation of Article 79 para (3) which protects Article 1 from amendments, it considers dignity as eternal value of society and law.

The line begun with the Universal Declaration and followed with the Grundgesetz was broken quickly. The European Convention of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms signed only some mouths later had forgotten the legal protection of dignity. Even if in its preamble refers the Universal Declaration, does not mention dignity, and its first Article prescribing protection of rights and freedoms is followed by the specific rights, firstly by everyone's right to life and prohibition of torture, inhuman or degrading treatment.

"Degrading treatment" does presume, of course, dignity, otherwise this notion looses any reason, but the formulation is too legal. It is rather a behavior rule for each member of the community and for each institution to abstain from the prohibited activity, than recognition of the inherent dignity. In other words the European Convention is blind to the transcendental dimension of dignity and gives ground only for individual and eventually to communitarian projections of specific rights. Right to life can be understood as a substitute of dignity, but in reality right to life is less than recognition of dignity. Right to life practically is right to not be killed, what is beyond any doubt an important right, but the solemnity of the Universal Declaration is missing.

The legally binding "translations" of the Universal Declaration are the two International Covenants. That on Civil and Political Rights makes a step back from the European Convention when makes reference in its preamble to the Universal Declaration, on the "recognition of the inherent dignity and of the equal and inalienable rights of all members of the human family" as the foundation of freedom, justice and peace in the world, or the other formula recognizing that rights protected

- 170/171 -

by the Covenant "derive from the inherent dignity of the human person '. However, this step is an uncertain one, hence the binding text of the Covenant turns its back to dignity and in its Article 6 declares only the "inherent right to life". Due to the "inherent" epithet this formulation is stronger than Article 1 of the European Convention. Inherence lets one to the conclusion that life has a transcendental projection but it is an attribute of life (or right to life) and not of dignity. It is out of question that life and dignity have common fields of interpretation but the two notions cannot be handled as synonyms.

In the text of the Hungarian Constitution after the renovation of the constitutionality in 1989, dignity and life appear jointly. Article 54 declares that "everyone has the inherent right to life and to human dignity, no one shall be arbitrarily deprived of these rights." Our Constitution is not an international document, but the firs interpretation by the Constitutional Court of life and dignity (Decision 23 of 1990 on the unconstitutionality of death penalty) is well known in Europe due to the database of the Venice Commission.[6] In this Decision the Court stated that "human life and human dignity form an inseparable unit, having a greater value than other rights; and thus being an indivisible, absolute fundamental right."[7]

If we compare this text to those examined previously, both similarities and differences can be found. The Constitution comes back to dignity but it declares as a right and the right to dignity is not standing alone, it is linked to the right to life. In the Decision of the Court it is palpable the uncertainty in interpretation of dignity or of right to dignity. After all, even if dignity is formulated as a right consequently it has legal connotations, the text does not omit the transcendental projection.

IV. Dignity and community

If we try to give a quintessence of the examined texts, we will see a sway of notions:

- 171/172 -

This sway has certain consequences. The more we want to forget the transcendental dimension of dignity by formulating it as only a more or less important right, the more we close it in the individual dimension. Right to dignity and even more right to life gets importance only in a public law discourse, in the absolute-type legal relation between the individual and State. As a second step in this absolute-type legal relation right to dignity or right to life as mother-rights will disappear and their components, the specific fundamental rights (of speech, of privacy, of self-determination, of data-protection etc.) will encroach them. The outcome is a sick-bug-eye effect: different regulations of law percept only the different components of an individual reflected by the different section-rights and in the different relations regulated by law the section-rights are recognized as completeness. The particle occupies the space of entirety, and in legal contexts - as Professor Frivaldszky pointed out - the human individuality presupposed to be born equal in dignity will disappear or will be diminished to the position of a necessary holder of section-rights.[8]

What conclusion results from this deduction? I think that it can be accepted as demonstrated proposition that dignity conceived in the transcendental-individual plane has at consequence a diminished value, and at extreme limits dignity is disappearing. Law and legal theory therefore should finish preening themselves as creators of values.[9] Public law has to regulate those relations where dignity is endangered, mostly regarding the punitive or restricting power of State, but it must not step across limits of action. Dignity of individual human persons should be left to exist within its natural sphere: the community consisted of individuals born with equal dignity.

The second plane, marked by the transcendental and communitarian dimensions has less implication to personal dignity. Similarly to transcendental-individual plane the transcendental-communitarian one is the action-sphere of public law. Nowadays we consider national sovereignty to be the necessary component of constitutionalism. Nation composed by individuals with equal dignity is the source of the state-power and it is its abstract carrier, in other words the legal basis of sovereignty. Law and the Constitution within it would not be able to supply the role of the social minimum without the mutual understanding based on togetherness having been experienced at the moment of constituting. Somebody else is needed for this beyond the rational acceptance, namely emotional or rather spiritual identifying: the faith that life is managed in a good manner and the basis of this is "our" constitutional order.[10]

In another drafting: without solidarity the order of the constitutionalism and law may be an appearance masking the sheer physical power only, the basis of the

- 172/173 -

common right may not. Though, the solidarity interpreted so inevitably carries the historical definiteness of the new order as well: the new constitutional order does not exist a priori, it is an existing nation's constitutional order. "We" of our deduction has the same transcendental attribute than dignity of a human individual: society is not a multitude of statistical individuals, it has its own dignity emerging from the dignity of its members. However, in everyday life this interpretation plays hardly any role.

Finally we arrived to the third, the individual-communitarian plane. Based on the previous considerations the first conclusion regarding the individual-communitarian plane of interpretation is that on this ground transcendental implications are not taken into consideration. When we try to trace the role of dignity in this plane, transcendental projection of dignity is accepted as a "hinterland-fact", a fact which is not questioned, not measured and not dissolved. Individuals are defined in this plane as it is suggested by the Universal Declaration: "born free and equal in dignity and rights"

This equality anchors the role of law: it is not less and not more than a compulsory rule regulating relations among individuals with equal dignity. If dignity is equal, law cannot make choices between individuals or particular situations where individuals appear. Law should regulate legal and not transcendental relations.[11]

Law should keep quiet when personal dignity is affected by dignity of another person.■

JEGYZETEK

[1] Szilágyi, Péter: Jogi alaptan. (Fundamental Theory of Law) Budapest: Nemzeti Tankönyvkiadó, 1992, 159-163., Petrétei, József: Magyar alkotmányjog I. (Hungarian Constitutional Law I) Budapest-Pécs: Dialóg-Campus, 2002, 119., Kukorelli, István (ed): Alkotmánytan I. (Course of Constitutional Law I) Budapest : Osiris, 2002, 77., Erdő, Péter: Egyházjog. (Canonic Law) Budapest: Szent István Társulat, 2003, 47.

[2] Inserted from the second sentence of Article I. by the Author, A. ZS. V.

[3] Pope Benedict XVI: "Caritas in Veritate", Encyclical Letter, para 15, 18, 32, 43-44, 53. Rome: Libreria Editrice Vaticana. Werner Heun: Az emberi méltóság - A filozófiai koncepciótól a jogi garanciáig. (Human Dignity - From a Concept of Philosophy to Legal Garatees) In Hajas, Barnabás - Szabó, Máté (eds): Emberi méltóság korlátok nélkül. (Human Dignity Without Limits) Budapest: OBH 209, 87-90.

[4] See: 'Introduction' by Prof. Ilse Staff. In Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany. Bonn: Press and Information Office of the Federal Government, 1998, 15., 40.

[5] Sólyom, László: Az alkotmánybíráskodás kezdetei Magyarországon. (Beginnings of Constitutional Jurisdiction in Hungary) Budapest: OSIRIS, 2001, 442., 446., 452.

[6] See: http://www.codices.coe.int/NXT/gateway.dll?f=templates&fn=default.htm, CODICES Precis / Decisions abregees English Europe Hungary HUN-1990-S-003 31.10.1990 23/1990. Also mentioned in Sólyom fn 5, 446.

[7] See CODICES, fn 6.

[8] Frivaldszky, János: Az emberi személy alkotmányos fogalma felé. (Towards a Constitutional Concept of Human Person) In Schanda, Balázs - Varga, Zs. András: Látlelet közjogunk elmúlt évtizedéről. (Diagnose about the Last Decade of our Public Law) Budapest: PPKE-JÁK, 2010, 41.

[9] Schanda, Balázs : Az Alkotmány megújításának kihívása. (Challenge of Reformation of the Constitution) In schanda-Varga fn 8, 55.

[10] This is clear in the first words of the US Constitution: "We the people...". Significance of "We" and inevitable role of "membership" is presented expressively and clearly by Roger Scruton in The Need for Nations. London: Civitas, 2004. See another approach of "We" (as substance of social harmony). In Francis Fukuyama: The Great Disruption. New York: Free Press, 1999.

[11] Takács, Albert: Az emberi méltóság elve a filozófiában és az alkotmányjogban. (Principle of Human Dignity within Philosophy and Constitutional Law) In hajas-Szabó fn 3, 40-42.

Lábjegyzetek:

[1] The author is associate professor (PPKE JÁK)