Nyilas Anna: Time management of civil procedures in European countries (DJM, 2008/1.)

Fair trial within a reasonable time

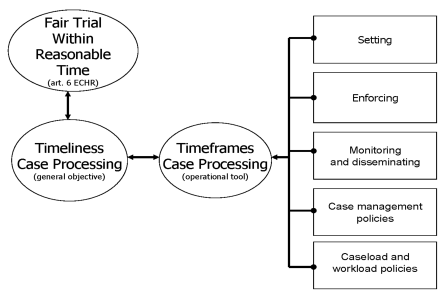

One of the most important aspects related to a proper functioning of courts is the adoption of the principles of a fair trial within a reasonable time and especially the principles laid down in article 6 of the European Convention on Human Rights. Fair trial within a reasonable time must be brought into relation with the workload of a court, the duration of the proceedings, specific measures to reduce their length and improve their efficiency and effectiveness. The length of judicial proceedings has been recognised as a priority within the objectives of the Council of Europe relating to human rights and the rule of law.

The concept of reasonable time sets a standard with a lower limit (which draws the border line between the violation and non-violation of the Convention) and should not be considered as an adequate outcome where it is achieved". Therefore the goal must be the timeliness of judicial proceedings, which means cases are managed and then disposed in due time, without undue delays. In order to do that, courts and policy makers need a tool to measure if cases are disposed in due time, to quantify delays, and to assess if the policies and practices undertaken are functional and consistent to the general objective of timeliness case processing. Timeframes are this tool". Timeframes are inter-organisational and operational tools to set measurable targets and practices for timeliness case proceedings. A timeframe is a period of time during which an action occurs or will occur. Inter-organisational means that since the length of judicial proceedings is the result of the interplay between different players (judges, administrative personnel, lawyer, expert witnesses, prosecutors, police etc.), timeframes have to be goals shared and pursued by all of them.

Timeframes should be established at three levels. At the State level as a general framework. At the court level to suit court features and local contingencies. At the judge level to have a real impact on the day-to-day court operations and practices. In order to be effective tools for the management of case processing, they have to be clearly measurable. Timeframes should be considered different from time limits. The latter are specific procedural rules that refer to a specific case; timeframes are inter-organisational tools to deal with targets and objective related to the timeliness of proceedings and court caseload, and therefore to the whole functioning of the court. Time limit is a limit of time within which something must be done. In judicial proceedings, this term indicates mainly the limits established by procedural rules. These limits can be mandatory and with consequences in a specific proceeding (e.g. the prohibition of presenting evidences after a specific time) or simply intimation without consequence (as when a judge should write a sentence within a week after the decision but nothing happens if the provision is not fulfilled). On the contrary timeframes should not be specified by procedural rules. They are just inter-organisational goals with consequences at this level.

• Denmark (Esbjerg District Court) - 58% of the civil cases should be disposed within 1 year,

• Norway - the timeframes are proposed by the Ministry of Justice with consent from the Norwegian Parliament. As of today, 100% of civil cases should be disposed in six months,

• UK - England and Wales (Manchester) - 80% of small claims should be disposed in 15 weeks, 85% of cases assigned to a so called fast track procedure should be disposed in 30 weeks, 85% of cases assigned to the so called multi track procedure should be disposed of in 50 weeks.

• Austria (Linz District Court) - all the judges receive a summary including the numbers of all the pending cases classified by duration (i.e. more than 1, 2 or 3 years). The heads of courts undertake consistent activities with this information such as balancing the caseload or commencing disciplinary proceedings. Parties can request the Court of Appeal to fix a time limit for special parts of proceedings, if they believe the judge's activities are not on time.

The length of court proceedings in the member states of the Council of Europe has been analysed and collected in a report, based on the case-law of the European Court of Human Rights. In the first part the report establishes criteria for assessing the reasonableness of the length of proceedings and establishes rules for calculation of the length of proceedings in the Court's case law. In the second part, it presents stages of proceedings where delays occurred, identifies causes of delay for various types of proceedings and presents an overview of domestic remedies to reduce the length of proceedings.

According to the report, the origins of delay before proceedings start are: territorial distribution of court jurisdiction; transfer of judges; insufficient number of judges; systematic use of multi-member tribunals (benches); backlog of cases; complete inactivity by judicial authorities; systematic shortcomings in procedural rules. From the initiation, to the closure of hearings: Failure to summon parties or witnesses; unlawful summons; late entry into force of legislation; disputes about the jurisdiction between administrative and judicial authorities; late transmission of the case file to the appeal court; delays imputable to barristers, solicitors, local and other authorities; judicial inertia in conduct of the case; involvement of expert witnesses; frequent adjournment of hearings; excessive intervals between hearings; excessive delay before the hearing. Finally, after the hearings: Excessive lapse of time between making of the judgment and its notification to the court registry or parties contributes to the delay.

Particular origins of delay in civil proceedings:

• Failure to use the courts' discretionary power; absence or inadequacy of rules of civil procedure;

• numerous adjournments of hearings, either of the court's own motion or at the parties' request, and excessive intervals between hearings

Such delays reflect civil courts' failure to control the proceedings.

In the Baraona judgment[1], the Court said although domestic legislation allowed state counsel to seek an extension of time the state might still be held responsible for any resultant delays. In the Vaz Da Silva Girao v. Portugal judgment of 2002 (§12) the Court found adjournment of hearings. In the Martins Moreira v. Portugal judgment of 1988, the Court noted that although the Portuguese Code of Civil Procedure made parties responsible for taking the initiative with regard to the progress of proceedings, it also required courts to take all appropriate steps to remove obstacles to the rapid conduct of cases.

In a dispute between the applicant and a health insurance office, the Court criticised the court of appeal for not hearing the case sooner: "in the Court of Appeal, the case was adjourned to a second hearing that was held nearly eleven months after the first.... although, whatever the reason for this adjournment, none of the evidence in the case file justified such a delay"[2]. In a recent case, the Court regretted that "more than 2 years passed between the second and third hearings held by the municipal court"[3]

Adjournments of hearings were held to be even more detrimental in a case where a procedural objection that had been presented 3 years earlier was finally accepted by the court, thus nullifying all the preceding stages of the proceedings (Ferreira Alves v. Portugal (n°2) judgment of 2003).

• Courts' failure to use the powers or discretion granted by the rules of procedure

• Judicial inertia in producing evidence

These are cases where the civil courts are insufficiently active when the rules of procedure allow them to be.

In a judgment, the Court accepted the applicant's argument that the reason she had had to present evidence, often repeatedly, was because the court had failed in its obligation to secure evidence of its own motion, as it was required to do in this type of case.

• Cases where civil procedure prevents the examination of new grounds on appeal

The fact that civil procedure prevents the examination of new grounds on appeal, which means that lower courts must show special vigilance, cannot justify excessive length of proceedings at first instance.

• Civil procedure does not allow courts to rectify parties' failure to conduct proceedings at a reasonable rate

The Court often states that although under the civil proceedings code in question it is for the parties to take the initiative with regard to progress, this does not absolve the courts from ensuring compliance with the requirement of Article 6 concerning reasonable time. In a recent case, in 2002[4], the Court found that even though the proceedings were governed by the initiative of the parties principle, the reasonable time requirement also required courts to scrutinise the conduct of the proceedings and exercise great care in granting adjournments or requests to hear witnesses and ensuring that necessary expert reports were submitted on time. It has emerged from several cases that domestic law does not give courts power to intervene to expedite proceedings. According to the Füterrer v. Croatia judgment of 20 December 2001, " the Government pointed out that in the civil proceedings the courts are limited in their activity as they may not take procedural steps on their own initiative but mostly according to the requests of the parties."

Croatia reformed its civil procedure in legislation of 14 July 2003, which replaced inquisitorial with adversarial proceedings in civil cases. As a result, only the parties to the proceedings are required to establish the facts, and then only at first instance. It is therefore no longer possible to have court decisions quashed and cases referred back for re-examination because courts have failed to establish certain facts on their own initiative. New pecuniary penalties were planned for the parties that misuse their procedural laws and thus cause unjustified delays in the procedures[5]. Moreover, the possibility for the representative of the public prosecution of asking for the revision of final decisions of the court within the framework of an extraordinary procedure was repealed in 2003[6].

The Hungarian system has also changed. Judges are no longer required to instruct the parties about their rights; measures designed to delay proceedings may now be sanctioned; since 1995, evidence has had to be presented at the same time as requests; deadlines may only be extended once by the courts and never by more than 45 days; and alternative means of settling disputes, such as mediation and arbitration, have been introduced.

The main tendencies of the European Court regarding reasonable time

The procedural phases of a case deemed to comply with the requirement of reasonable time generally last less than 2 years. When this period lasts longer than 2 years but goes uncriticised by the European Court, it is nearly always the applicant's behaviour that is to blame and the delay is at least partly down to their inactivity or bad faith[7]. In 23 complex cases where there were rulings that no rights had been violated, it is striking to note that in twelve cases - over half - the applicant's conduct is criticised by the Court as having contributed to the delay. The finding of no violation is explained by the inappropriate conduct of the applicant.

Even if the applicant does not act with the required diligence, the Court always considers how the courts have responded: if the courts cannot be found at fault for any particular failure to act and if the case involves proceedings in which the parties bear responsibility in the conducting of the process, the parties will be held entirely to blame for the delays due to their failings and inappropriate demands and it will be ruled that there has been no violation, even if the length of proceedings seems excessive in objective terms.

For any proceedings lasting longer than 2 years, the ECHR examines the case in detail to check the diligence of both national authorities and the parties in the light of the case's complexity; for proceedings shorter than the two-year mark, the Court does not carry out this detailed examination.

What is at stake for the applicant in the dispute is a major criterion for assessment and may prompt the European Court to reconsider its usual practice of considering a period of less than 2 years as acceptable for any court instance[8]. It may also be a reason for a court to prioritise this type of case in its schedule of hearings[9]. Given the backlogs in the courts, the European Court seeks to reconcile the concern with reasonable time with that of proper administration of justice; when considering the treatment to be given to pending cases, it therefore invites courts with a backlog to call cases by order of importance and no longer only on a first come first served basis; it implicitly suggests taking account of what is at stake for the applicant in the dispute[10].

In complicated cases, the Court, bearing the complexity of the case in mind, focuses only on the lengths of proceedings that are manifestly excessive and demands precise explanations regarding these "abnormal" durations if it is to rule that there has been no violation[11]. But it is distinctly less strict in simple cases.

Cases may be delayed because of the inactivity of parties. These cases have to be specifically monitored and addressed in a different way from those cases (active pending) that need a court intervention to proceed.

Procedures should be consistent with the case complexity. The management of cases should be differentiated considering, for example, the value, the number of parties and the legal issues involved in a case. Summary procedures should be established to dispose of cases considered to have a low level of complexity.

Judges are the "third impartial player" in a conflict resolution process. They are the only ones able to set the pace of litigation independent of the parties' interests. Therefore, they should have a pro-active role in case management in order to guarantee fair and timely case processing, according to timeframes. It must also be noted that the jurisprudence of the ECHR says that "court inactivity", "judicial inertia in producing evidence" and the "complete inaction by the judicial authorities" have been causes of violation of the reasonable time clause.

In December 2004 the European Commission for the Efficiency of Justice (CEPEJ) adopted the Report: "European judicial systems: facts and figures". It was the result of an experimental exercise, based on a Pilot Scheme (questionnaire) for evaluating judicial systems designed to obtain comparable, objective quantitative and qualitative figures concerning the organisation and functioning of judicial systems. 40 of the 46 member states of the Council of Europe were considered in the experimental process. This was a European first: no such exercise had ever been conducted in the justice field. Based on the lessons learnt from the pilot exercise, the CEPEJ launched in 2005 an initial regular evaluation exercise, using the in-depth methodological approach implemented in the pilot exercise and drawing on the Network of national correspondents set up to collect figures. This report was adopted by the CEPEJ at its 7 th plenary meeting (July 2006). It is the result of this new evaluation process. It is based on reports by the states, whose preparation was coordinated by national correspondents appointed within the states. It presents the results of a survey conducted in 45 European states. It is unique in the number of subjects and countries that are covered.

| Country | Q68 Total number of civil cases in courts (litigious and not litigious) | Civil and administrative litigious incoming cases (1st instance) | figures per 100 000 inhabitants | Decisions on the merits | % of decisions subject to appeal in a higher court | Cases pending by 1 January 2005 | % of pending cases of more than 3 years |

| Albania | 41755 | 24960 | 813 | 9,0 | 3386 | 0 | |

| Andorra | 3765 | 3070 | 3993 | 1100 | 1,9 | 1426 | 1,3 |

| Armenia | 101703 | 101703 | 3168 | 84851 | 4,6 | 5927 | |

| Austria | 4807881 | 818213 | 9970 | 44169 | 32,2 | 177106 | 1,5 |

| Azerbaijan | 53249 | 53249 | 638 | 38252 | 21,9 | 4616 | |

| Belgium | 700709 | 694986 | 6653 | 733890 | 5,1 | ||

| Bulgaria | 680742 | 573399 | 7388 | 542417 | 68852 | ||

| Croatia | 417223 | 160790 | 3618 | 237749 | |||

| Cyprus | 338159 | 29043 | 4212 | 31220 | 1,0 | 32679 | 20,0 |

| Czech Republic | 1209659 | 285469 | 2793 | 316367 | 171454 | 5,9 | |

| Denmark | 141486 | 126696 | 2347 | 2,0 | 35308 | ||

| Estonia | 37781 | 25301 | 1873 | 25682 | 9,3 | 11826 | 7,6 |

| Finland | 176171 | 9460 | 181 | 9715 | 24,6 | 5682 | 4,0 |

| France | 3390413 | 1779344 | 2862 | 1368181 | 12,8 | 149000 0 | 12,0 |

| Germany | 1375506 1 | 3083980 | 3738 | 1375938 | 23,4 | 151091 6 | |

| Greece | n.r. | 168651 | 1525 | 113748 | 100,0 | 34087 | |

| Hungary | 635000 | 165027 | 1634 | 86965 | 25,2 | 76203 | 1,4 |

| Iceland | 25664 | 1296 | 441 | 0,9 | 728 | 0 | |

| Ireland | 135510 | 130391 | 3228 | 7716 | 19,0 | ||

| Italy | 3944961 | 3600526 | 6159 | 1156045 | 21,8 | 408731 1 | |

| Latvia | 116808 | 59156 | 2551 | 44491 | 6,6 | 20720 | 1,4 |

| Liechtenstein | 831 | 416 | 1202 | 89 | 154 | ||

| Lithuania | 152132 | 152132 | 4441 | 149646 | 5,0 | 1779 | |

| Luxembourg | 12079 | 4315 | 948 | 8931 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| Malta | 5858 | 5858 | 1455 | 14277 | 33,0 | ||

| Moldova | 56401 | 52414 | 1548 | 42124 | 15,7 | 6692 | n.a. |

| Monaco | 950 | 748 | 2492 | 860 | 20,0 | 1091 | |

| Montenegro | n.r. | 15462 | 2492 | 11996 | 21,7 | 3466 | 8,4 |

| Netherlands | 1131810 | 902980 | 5542 | 896700 | |||

| Norway | 13450 | 13450 | 292 | 13944 | 12,0 | 7751 | 0 |

| Poland | 7602495 | 1162480 | 3045 | 1201149 | 17,8 | 498955 | |

| Portugal | 628170 | 628170 | 5966 | 524684 | 132566 2 | ||

| Romania | 1353749 | 1153187 | 5321 | 933854 | 247337 | ||

| Russian Federation | 6334000 | 5852000 | 4079 | 5019000 | 5,9 | 485000 | 0,8 |

| Serbia | 756758 | 687431 | 9168 | 461589 | 23,7 | 225555 | n.a. |

| Slovakia | 228755 | 238662 | 4420 | 12,0 | 226462 | 15,2 | |

| Slovenia | 550470 | 25335 | 1268 | 18971 | 21,2 | 44418 | 31,8 |

| Spain | 1862966 | 826835 | 1926 | 188246 | 17,5 | 578209 | |

| Sweden | 69721 | 43539 | 482 | 4,8 | 26151 | 3,9 | |

| Turkey | 2116746 | 1391095 | 1955 | 1081777 | 671915 | ||

| Ukraine | 1873438 | 2031123 | 4296 | 224325 | |||

| UK England & Wales | 1770056 | 1597123 | 3011 | 61824 | 0 | ||

| UK Northern Ireland | n.r. | 28062 | 1641 | 24407 | 2,0 | 9364 | |

Recommendations of the Council of Europe

Recommendation R (84)5 on the principle of civil procedure designed to improve the functioning of justice

This recommendation establishes criteria to improve the functioning of justice through more flexible and expeditious judicial procedures, the amendment of the rules that can be manipulated or abused to cause delay, and the promotion of an active role of courts in case management. The focus is on procedures, on their opportunistic use by the parties, and on other delays caused by witnesses or by experts. Solutions aim at discouraging strategic or opportunistic behaviour of lawyers, parties and witnesses with sanctions. On the other side, they suggest a more intensive use of "modern technologies" to take evidence. In addition judges and courts should have a more active role in case management. More in detail, the recommendation suggests several procedural guidelines, among which:

• to establish a typical procedure based on "not more than two hearings, the first of which might be a preliminary hearing of a preparatory nature and the second for taking evidence, hearing arguments and, if possible, giving judgment.";

• the need to impose sanctions:

- to parties that "do not take a procedural step within the time-limits fixed by the law or the court."

- to witnesses "in case of unjustified non-attendance" at the hearing;

- to experts "appointed by the court [who] fail to communicate his report or [who] is late in communicating it without good reason."

• courts should also "play an active role in ensuring the rapid progress of the proceedings" with the powers "to order the parties to provide such clarifications as are necessary; to order the parties to appear in person; to raise questions of law; to call for evidence [...] to control the taking of evidence; to exclude witnesses whose possible testimony would be irrelevant to the case [...] or when their number would be excessive".

Recommendation Rec. (86) 12) concerning measures to prevent and reduce the excessive workload in the courts

This recommendation deals with the problem of excessive workload due to the growing number of cases brought to the courts.

More in detail, it advises "encouraging, where appropriate, a friendly settlement of disputes, either outside the judicial system, or before or during judicial proceedings". It considers measures such as "conciliation procedures for the settlement of disputes prior to or otherwise outside judicial proceedings" and "entrusting the judge [...] with responsibility for seeking a friendly settlement of the dispute". Also lawyers should be involved.

Recommendation R (95) 5 concerning the appeal systems and procedures in civil and commercial cases

This recommendation moves away from recognising that in principle it should be possible for any decision of a lower court ("first court") to be subject to the control of a higher court ("second court"), but it should be considered appropriate to make exceptions to this principle. The recommendation then fixes criteria for filtering the cases to be heard by the second court. Exceptions should be founded in the law and should be consistent with general principles of justice.

Specific categories of cases, such as small claims, could be excluded from the right to appeal. Another strategy advised by the recommendation is to "prevent any abuse of the appeal system" with measures such as "requiring appellants at an early stage to give reasoned grounds for their appeals and to state the remedy sought" or "allowing the second court to dismiss in a simplified manner [...] any appeal which appears to the second court to be manifestly ill-founded, unreasonable or vexatious".

The recommendation suggests also three measures well related with the topic of timeframes: the enforcement of time limits, an active role of judges in case management and the involvement of stakeholders. "Strict observance of time limits, [...] and providing sanctions for non-compliance with time limits, for example fines, dismissal of the appeal or not considering the matter to which the time limit related";

Case management in Hungary - some figures

Duration of procedures in Hungarian courts 2006./1. semester, accomplished cases

| Local courts | County court, appeal cases | |||||

| 0-3 months | 33947 | 0-3 months | 5751 | |||

| 3-6 months | 21441 | 3-6 months | 2559 | |||

| 6-12 months | 17660 | 6-12 months | 1432 | |||

| 1-2 years | 7988 | 1-2 years | 166 | |||

| 2-3 years | 1923 | 2-3 years | 20 | |||

| Over 3 years | 1204 | Over 3 years | 11 | |||

| County court, first instance cases | Regional courts of Appeal | |||||

| 0-3 months | 2317 | 0-3 months | 953 | |||

| 3-6 months | 1162 | 3-6 months | 406 | |||

| 6-12 months | 1393 | 6-12 months | 107 | |||

| 1-2 years | 1101 | 1-2 years | 10 | |||

| 2-3 years | 351 | 2-3 years | 1 | |||

| Over 3 years | 122 | Over 3 years | 0 | |||

Incoming cases

| 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006/1. | |

| Local courts | 160242 | 158486 | 158007 | 151204 | 154067 | 150268 | 77356 |

| County court, appeal cases | 23051 | 23307 | 23436 | 22405 | 19914 | 18174 | 9589 |

| County court, first instance cases | 3525 | 4052 | 4740 | 7485 | 10960 | 11134 | 6098 |

| Regional courts of Appeal | - | - | - | - | 1996 | 2443 | 1553 |

Pending cases

| 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006/1. | |

| Local courts | 76831 | 74484 | 72617 | 69439 | 68987 | 68080 | 61256 |

| County court, appeal cases | 4871 | 4796 | 5155 | 5423 | 5180 | 5203 | 4854 |

| County court, first instance cases | 1860 | 2297 | 2879 | 4707 | 7216 | 8522 | 8173 |

| Regional courts of Appeal | - | - | - | - | 429 | 609 | 686 |

At this time, up to one thousand and 2 hundred cases are pending for more than 5 years in the Hungarian courts. However, in 90% of these cases the delay is due to causes that fall out of the courts' responsibility. In the Regional court of Appeal of Debrecen, 50 cases remained pending by the end of the year 2006. The courts' correct work is reflected in the fact that the public trust in the courts is 60 per cent. 86% of the incoming cases terminate in one year. With the re-establishment of the Regional courts of Appeal, the workload of the Supreme Court has been reduced significantly and the processing time has decreased from 3 years to 68 months.

A Report called "Time management of justice systems: A Northern European study" has been completed in 2005. It describes measures that might be helpful in keeping time use in European judicial systems within the boundaries of the "reasonable time" - standard set out in article 6 (1) of the European Convention of Human Rights.

First, the authors have searched for innovative measures or models for time management and focused on the following four elements:

- A brief overview of the problems or dysfunctions that made improved measures against delays desirable,

- A short summary of the ideas and debate behind the reform and how it has been justified,

- A description of the content of the reform or the reform model used and the reform methodology applied,

- A brief overview of the implementation and results, and follow-up systems.

The study separates processing time into two major components - action time and standstill time. Action time - or "working time" - is the time spent when someone works on the case. Standstill time - or "waiting time" or "queuing time" - is the time when nothing happens. The study has a distinct focus on standstill time.

The concept of "court delay" is difficult to define, because it does not refer only to problems related to rules of procedure, but also to working practices of the courts. In civil matters to the interaction between the court and advocates, and to the interaction between parties and the court. One point of attention is also the interaction between first instance courts, appeal courts and the supreme courts. Overall, the complexity of situations involving court delays is highly differentiated.

Without an increase in the number of staff, the processing times will probably continue to rise e.g. because of backlogs from previous years, the expected increase in case loads and because of the increasing complexity of cases. Particularly, civil proceedings consume several days of action time because of their complexity. However, the problems encountered cannot be explained only by the lack of staff; the factors behind delays are more complex. The number of cases that are decided depends on the resources of the court, but also on the efficiency and organisation of the court. Problems also arise because the values and objectives of the regulations are not all followed in practice.

Although indispensable deadlines for courts are rarely used in the Nordic countries, a range of more flexible time limits exists. They are of different kinds: maximum deadlines, ordinary or average deadlines, optimal deadlines ("as fast as possible"). The courts, according to an authority given by law, might set discretionary deadlines. Such deadlines usually affect the parties that might be entitled to complain if they are not complied with. Courts might set up internal deadlines that might be controlled and sanctioned by the court, but without entitlements for the parties. The parliament and the court administration or ministry of justice as part of budgetary allocations or other general administrative directives might also set up such deadlines.

A new kind of deadlines has developed due to an increased emphasis on court management. It can be called 'percentage deadlines': a certain share or percentage of a defined caseload must be handled within one limit, while the rest might be handled within another and more liberal limit. It is left to the courts to select the cases necessary to fulfil the percentage limit. The judge responsible for the preparation should secure a swift, economical process by active and systematic steering work. Immediately after the defendant's response to the claim is received, the judge must examine whether the parties involved have been introduced the possibilities for mediation. Information of court mediation must be given in all cases possible.

Quality benchmarks regarding swiftness of proceedings

| 1. Proceedings organised within an optimal timeframe. |

| 2. Timetables for proceedings planned according to their implications to the parties involved. |

| 3. The parties involved have the notion that the process has been handled in a swift manner. |

| 4. The timeframes agreed upon must be adhered to. |

1. Proceedings organised within an optimal timeframe

What is meant by 'optimal timeframe' in this context is the period of time during which the process can be carried out according to the regulations for legal proceedings. Therefore, the concept of 'optimal timeframes' does not include factors such as the extent and complexity of a matter or the available resources of the court of justice. Attaining the optimal timeframe of proceedings requires that the process does not contain periods during which nothing is done.

2. Timetables for proceedings planned according to their implications on the parties involved T

he second quality criterion requires that matters are processed, and the timetable for proceedings is planned according to their implications and importance to the parties involved. The practice has traditionally been that matters are handled according to the order of arrival. However, this thinking rarely corresponds to real life conditions. Already, because of various regulations regarding hearings, the matters are directed to different 'process tunnels'. The workloads of individual judges also considerably affect the processing times.

3. The parties involved have the notion that the process has been handled in a swift manner

Although the case might have been processed in a swift manner from the courts' perspective, the parties involved may not share this notion. The differences in perceptions between the court and the parties involved can be reduced by explaining to the parties involved the separate phases the overall timeframe consists of and why.

4. The timeframes agreed upon must be adhered to

During the court proceedings the court sets several internal time limits for different phases of the process. The judge and the parties involved might agree upon a particular action to be carried out at a set time. The fourth criterion provides that both the court and the parties involved comply with the dates set.

Court specialisation

Court specialisation is both a way to improve the quality of the courts and to improve their swiftness. Court specialisation can be roughly divided into two categories: internal and external specialisation. One type of internal specialisation is a model, which covers all the judges of the court in contrast to a model that concerns only certain legal matters and therefore only certain judges. The specialisation method used depends on the size of the court in question. Extending the specialisation to all judges is assumed to lead to a higher quality and increased swiftness and adjudication of all types of matters in the court. In this model all judges receive the same opportunities to enhance and develop their skills. There can also be reasons to limit specialisation only to certain judges or legal matters. This reason can be that the matter is complicated and creates unbalance in the court. Special competence of certain judges in a court can also result in simplifying the launch of special working-methods in this area.

The simplest way to carry out external specialisation suggested in the report is that the judges interested would report themselves to an 'expertise bank' within a region. The expertise bank would contain information of the interests and experiences that the judge has according to certain matter. The expertise bank should be available to all courts within a defined region. A court that wishes so could in complicated cases contact a judge listed in the expertise bank in order to receive advice or adjudication help in the matter. It would then be possible to record special skills that certain judges already obtain in particular matters with minimum administration.

One obvious problem related to question of specialisation is that in reasonably small countries (such as the Nordic states) the model of specialised individual courts might not be a very cost-effective solution. The geographical distances are in many cases long and the legal protection of citizens might become jeopardised in this kind of model. When assessing the models of internal specialisation the option to limit specialisation within individual courts to certain judges or legal matters appears to be the best solution.

Swedish judges were interviewed about their experiences of specialisation and about the advantages and disadvantages related to it. Many general courts expressed the notion that the major advantage of specialisation is that the overall time of proceedings becomes shorter and the handling and adjudication more effective. In several answers the notion that with more specialisation there is a greater possibility to acquire and develop skills and experience on special matters from the specialised judges, was expressed. This in turn results in continuity and increased quality of adjudication. Several respondents believed that specialisation leads to a more established legal praxis. Many pointed out that the more important the specialisation is, the more independent is the branch of jurisdiction in question (e.g. property formation, environment matters and economic matters). Specialisation can be necessary within these branches of jurisdiction in order for the judges to attain the necessary depth of professional skills.

Experiences for and against specialisation expressed by Swedish judges

| Advantages | Disadvantages |

| Shorter processing times | Problems in personnel replacement |

| More established legal praxis | Allocation of matters according to needs |

| Consistency, firmness, efficiency of adjudication | Uneven distribution of workloads |

| Increased skills, expertise, competence, efficiency | Increased monotony |

| Undesirable development of legal praxis |

The most often mentioned disadvantage related to specialisation in the general courts was that in cases where the specialised judge is absent it can be difficult to find a replacement, which can make the system of specialised judges vulnerable. Another drawback mentioned was that the workloads can become unevenly distributed so that certain judges have too many cases to decide and some judges only rarely or never receive cases of particular type. Many courts mentioned as a disadvantage the fact that working with just one type of matter may result in finding the work too monotonous. This can be tackled by rotating judges and/or matters among different departments in the court. Another disadvantage mentioned was the possibility that specialisation leads to the 'specialists' developing their own legal praxis. An advantage mentioned by administrative courts was that specialisation enables a better concentration on more unusual matters, which results in reaching a certain level of expertise.

Division of tasks

The basic idea behind the system of delegating tasks is to increase the amount of time the judge has to conduct his/her 'priority tasks' (such as adjudication work) by allocating some 'secondary tasks' (such as administrative work) to other members of the staff. When the judge has the opportunity to concentrate on his or her main tasks it is assumed that the levels of quality and efficiency increase as well as the use of resources in the court. There are probably large variations between different courts on their level of delegating duties. These variations can be explained by differences in competence or resources in case processing time. The arguments point to a persisting dilemma in organising courts. Specialisation appears to be double edged. Specialised judges are supposed to be more effective. They handle more cases with better quality than non-specialised judges within the same time spent. However, they also create inflexibility if all cases that fall within their specialised competence are supposed to be handled by them and not by other, non-specialised judges. Then they might become bottlenecks if they are too few compared to the caseload.

Small claims

For certain types of disputes many countries have introduced proceedings to handle the cases within a short period. Recently, in many countries, specific proceedings (with a short duration) have been introduced in the area of small financial claims.

Sometimes the proceedings are simplified and the intervention of the judge is limited. In other situations new information technology has been introduced to handle small cases quickly and efficiently. The treatment of the small claims cases can be done by specialised courts (for instance municipal courts), specialised judges (like peace judges) or a unit within a first instance court of general jurisdiction.

ADR (alternative dispute resolution)

Alternative dispute resolutions, in its various forms, can decrease the first instance court caseload and avoid court congestion. There are different forms of ADR, namely: arbitration, conciliation and mediation. In certain countries arbitration is often used to solve a dispute outside a court (Germany and the Netherlands are examples of countries where arbitration is one of the many options to solve a dispute). However in most recent years another form of alternative dispute resolution has been introduced: mediation. Mediation is mostly practiced in some specific areas of conflict: a dismissal case, a divorce case, certain administrative law cases and also in the area of criminal matters. The general idea of mediation is that both parties are willing to find a solution to a conflict, which is acceptable to all (instead of a decision made by a judge, which can be in favour of one party and against the (losing) other party). In Slovenia (Nova Gorica District Court) - the court has set up a specific program of ADR in civil cases. The goal is to solve the cases by settling the dispute without trial. If both parties agree, the court guarantees to schedule the first mediation meeting in 90 days. The proceeding is free for both parties. Specially trained mediators have the task to help the parties to reach an agreement that solves the dispute using negotiation techniques.

Final reflections

The confidence of citizens in the legal system is dependant on their perceptions on how quickly cases are processed by the justice system and on the extent to which this processing is conducted in a way that ensures the protection of the individual's legal rights. Naturally, the case processing times of courts are directly related to the number of incoming cases and to the number decided.

Delays in proceedings have several negative implications. Often the cases in legal proceedings concern issues that are strongly connected to people's every-day life such as children, family, income, living conditions, work, property and safety. The legal process is often a unique experience in the life of a person that might take over thoughts and consume energy and resources from other areas of life. Already for these humane reasons it is essential that the proceedings are carried out without unjustified delays.

The public service of justice must operate in an efficient way, considering both the need to guarantee individual rights and freedoms and the necessity to deliver quality service for the sake of the community. The aim is to assess the judicial system respectful both of the rights of individuals and the quality provided to the users of a public service. One of the instruments to provide citizens free of charge information on legal texts, case-law of higher courts and other (practical) documents is the creation of special websites or webportals. ■

NOTES

[1] Baraona v. Portugal judgment of 8 July 1987.

[2] Duclos v. France judgment of 17 December 1996.

[3] Volesky v. Czech Republic judgment of 29 June 2004, §105.

[4] Violation of Article 6§1 for proceedings lasting thirteen years and three months in a complex case of expropriation with an appeal on points of law still pending (three levels of court).

[5] Resolution ResDH(2005)60 concerning the judgments of the European Court of Human Rights in the case of Horvat and 9 other cases against Croatia (see appendix I) adopted on 18 July 2005.

[6] Resolution ResDH(2005)60 idem.

[7] Aforementioned Dosta v. Czech Republic judgment, 25 May 2004: an interesting judgment in this connection as several sets of civil procedures were lodged by the same applicant in simple cases examined by the ECHR.

[8] Le Bechennec v. France judgment of 28 March 2006.

[9] See in this connection the CEPEJ Framework Programme "A new objective for judicial systems: the processing of each case within an optimum and foreseeable timeframe" of 11 June 2004, Line of Action 10: "defining priorities in case management", p. 15.

[10] Union Alimentaria Sanders SA v. Spain judgment of 7 July 1989.

[11] "the investigating judge concluded the preliminary judicial investigation [...] four years and seven months after the applicant was first questioned as a suspect. This would appear to be a disturbingly long period of time.[...]. In the circumstances, it is particularly necessary for the length of this period to be convincingly justified." (§ 51) Hozee v. Netherlands judgment of 22 May 1998 (no violation in a complex criminal case).