Balázs J. Gellér[1]: The Identity of the Interpreter of Criminal Norms (Annales, 2005., 281-312. o.)

According to Kelsen, every norm presupposes at least two persons: the normpositor and the norm-addressee;[1] consequently, when examining the constitutionality of a criminal norm both the norm-positor and the addressee must be scrutinised. Whereas the significance of the author in the interpretative enterprise has been subject to intense study in both German and English, as well as in American literature,[2] almost no attention has been paid to the addressee and/or interpreter from the point of view of legality.[3] It should be noted that a

- 281/282 -

duality of terms is being used: the 'addressee' and the 'interpreter'. These two concepts are not to be equated. On the contrary, it is part of this argument that a difference should be maintained between the two groups.

Criminal norms are addressed to everybody; no human being can be above them.[4] Thus the universality of criminal law makes every person under its jurisdiction - with some simplification these persons can be described as citizens -an addressee. Is the addressee, that is the citizen, however, the same as the interpreter of the criminal norm? In other words: if one is to decide upon the constitutionality of a criminal norm (statute or precedent), or of an application of a criminal norm, both the constitutional criteria and the criminal norm or its application have to be understood. Does legality place any requirements on the methodology of this understanding? That is, is interpretation to be undertaken with a view to the universality of the addressee?

It is true that the citizen's status, or the judge's role, in interpreting criminal norms has been expounded by other authors to some extent.[5] The issue, how-

- 282/283 -

ever, of whether an adherence to legality requires some presumption of the characteristics of the addressee has only been dealt with very briefly indeed in the literature.[6]

The first question, which has to be examined, is whether in criminal law legality has any bearing at all on the person of the interpreter (i). In other words, if a criminal norm or its interpretation should conform to the requirements of legality, is it necessary to take into consideration certain attributes of the addressee, and/or the final interpreter? This problem leads to two further points: who is really the addressee of a criminal norm (ia); and what effect does he have on the legality of criminal norms and their interpretation (ib)? A methodological point will then also have to be decided. In light of the answers to the questions put forward above, the approach taken by this study can now be stipulated. These issues will firstly be looked at from a theoretical point of view, and then answers that can be found in various jurisdictions will be considered.

The distinction between the two types of rules - those addressed to the general public and those addressed to officials - can be traced back in modern times to Bentham.[7] By generalising Bentham's ideas Dan-Cohen suggests that the rules addressed to officials (which he calls 'decision rules') necessarily imply the

- 283/284 -

laws addressed to the general public (which he calls 'conduct rules').[8] This in turn would lead to the conclusion that a single set of rules is sufficient to fulfil both functions: guiding official decisions and guiding the public's behaviour.[9] As Dan-Cohen puts it, " When we say that the judge 'applies' (or 'enforces') the law of theft, we mean that he is guided by a decision rule that has among its conditions of application (1) the existence of a certain conduct rule...and (2) the violation of that conduct rule by the defendant."[10] Assuming the validity of this argument, it follows that criminal norms are partly addressed to officials, and partly to the general public.[11]

Nevertheless, acceptance of this approach has not been unequivocal. Kelsen tried to erase the distinction by treating all laws as directives to officials; he saw the sanction (the official legal response to the required behaviour) as a constitutive part of the law, without which the rule would lose its validity.[12] In essence, Austin seems to have attempted the unification of the two norms from the other direction, focusing on conduct rules, by stating that every law or rule is a command.[13]

- 284/285 -

Whilst the above disagreement might seem to be a purely theoretical exercise, in reality it touches on the very essence of the relationship between legality and the identity of the addressee of the norm. If one accepts the proposition that a criminal norm as a whole is not necessarily addressed to the citizen, then those principles, for example, which can be summarised under the common description of the requirement of foreseeability will take on a very different meaning.

Dan-Cohen, using an example of the defence of duress and necessity, claims that "far from being a defect, the failure of these rules to communicate to the public a clear and precise normative message is, in light of the policies underlying the defence, a virtue."[14] Thus, even though courts and commentators have long recognised the vagueness of the defence of duress and necessity,[15] he claims that in this case, as in several other cases, if the ordinary meaning of the words and concepts used by the norm in question could have been understood in the same way as later construed by the court, then the principle of fair warning - that is, legality - was not violated.[16] Similarly, "the clarity and specificity of decision rules, and hence their effectiveness as guidelines, may be enhanced by the use of technical, esoteric terminology that is incomprehensible to the public at large,"[17] and this would still not violate legality. It is now apparent that Dan-Cohen's proposition goes to the heart of the matter, and by taking his examples from American jurisprudence, he takes this study further into an examination of the void-for-vagueness doctrine's relevance to the issue under consideration.

In furtherance of his argument, Dan-Cohen uses a model in his enquiries, which he calls 'acoustic separation'. This term describes a situation, which separates the two groups of addressees (general public and officials), those of the conduct and those of the decision rules respectively.[18] The difference between these two classes of addressees is that the 'officials' know the law, or are equipped to find out as far as possible what the law is, whereas the 'general

- 285/286 -

public' is at best a group of average citizens.[19] These two groups shall be, therefore, referred to as 'lawyer' and 'layman' in the following, which emphasises the fundamental reason for this distinction: the layman is ignorant of the law.

Dan-Cohen suggests that the vagueness of laws is the vehicle for 'selective transmission': when part of the norm reaches only one of the groups. Vagueness in this sense might be caused for the following reasons: 1) the indeterminacy of the standards included in the norm makes it less likely that ordinary citizens will be able to rely on them; and 2) the existence of a huge body of decisional law, which because of its sheer volume and complexity is intellectually (if not physically) inaccessible to the legally untutored citizen.[20]

It seems that the above two situations can indeed be summarised under the heading 'ignorance of law'.[21] The phrase 'ignorance of law' thus acquires two fundamental meanings. One describes the 'general ignorance of law', that is, ignorance of a branch or of a field of an art or a profession. This can manifest itself, as far as law is concerned, as ignorance of law in general, or as a lack of information about a specific law or legal issue. The other meaning, which will be called 'special ignorance', describes a situation, in which all possible information on a specific legal issue is at hand, and is professionally evaluated, but still results in a belief about the lawfulness of an action, which later proves to be erroneous. This latter type of ignorance may affect, as far as law is concerned, lawyer and laymen alike. Both general and specific ignorance can be blameless or blameworthy. General ignorance of law is, as will be shown, blameworthy in most cases - ignorantia iuris neminem excusat. Jeffries suggests a test, the Lambert test, which would mitigate this - as he calls it - the formal lawyers' notice, and introduces a so-called 'reasonable man standard'.[22]

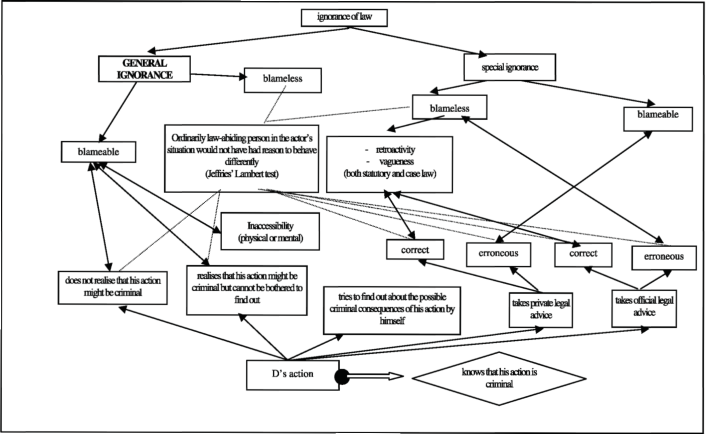

As far as special ignorance is concerned, it is blameless, if a lawyer could not have known or could not have been certain that the act was criminal. This can happen for two main reasons: the law was introduced retroactively, by statute or by judicial decision; or the existing law (statutory or case law) was so vague that it was impossible to ascertain its content with sufficient precision. It will be argued that there is a further type of blameless special ignorance: when the defendant took official advice, acted upon it, and the advice proved to be wrong. In this setting official advice has to be an authority of the state with advisory powers on that certain issue. Erroneous private legal advice will, it seems, not exculpate the defendant. The claims made here will now be addressed in more detail (see Chart 1).

- 286/287 -

Chart 1: Ignorance of law and the action of the defendant.

- 287/288 -

Whilst these two primary meanings of ignorance of law - general ignorance and special ignorance - are indisputably inter-linked, it seems that Dan-Cohen does not give sufficient weight to this duality of meanings, which has considerable consequences in respect of legality.[23] It follows that the primary question is whether legality should be based on the presumption of general ignorance or specific ignorance. Alternatively, is there a more complicated system built on the relationship between ignorance and the addressee's actions? Only after answering this question will it be possible to find solutions to the problems raised by retroactivity and vagueness, and describe the characteristics of the interpreter of a criminal norm.

Before starting with the analysis of the dilemmas outlined above, a further distinction has to be made between ignorance of law and ignorance of fact. DanCohen, whilst not spelling out this typology, discusses the acting at one's peril rule, which seems to be treated, in some cases of necessity, as an example of ignorance of fact. Such a situation might arise, for example, if a private citizen uses force to apprehend an escaping felon and by that kills him, and he acts on suspicion that a violent or serious felony has been committed; in such a case for the homicide to be justified it must be shown that his suspicion was correct.[24] The acting at one's peril rule is in another form well known to Continental criminal laws. It takes the shape of a so-called objective condition of liability, which describes a constituent of a crime, which by its existence makes the offender liable, regardless of whether he knew about this constituent or not (presuming of course that other conditions of criminal liability are met).[25] For example, under Hungarian law one is only liable for the crime of persuasion to commit suicide,[26] if the person being persuaded commits or attempts to commit suicide. Liability arises regardless of whether or not the offender knows the result of his persuasive activity. If, therefore, the person whose suicide the offender tried to achieve does not even attempt to kill himself, the offender is not punishable.[27]

- 288/289 -

The objective condition of liability, which belongs entirely to the actus reus -that is, the objective side of the offence - is very similar to acting at one's peril. Both make the offender's liability subject to the existence of an objective fact of which the offender may not be aware.[28] Whether a defence should consist simply of the external facts - similar to the objective condition of liability -or the facts plus the state of mind, is a policy issue.[29] Nevertheless, Dan-Cohen suggests that by looking at the mens rea requirement vagueness can be averted.[30] His reasoning shall not be examined in detail here; at this point it is only necessary to observe that he defends his proposition by claiming that the objection to it rests on the fallacy that mens rea requirements are based on knowledge of facts and not law.[31]

If mens rea requirements were to include knowledge of the law, very few convictions could be achieved. Such a reductionist view of law, limiting it basically to the Ten Commandments, is not only erroneous but also unnecessary. The mens rea requirement makes it necessary for the defendant to know the so-called historical facts - that is, those facts of the case, which have a legal consequence. The principle of ignorantia iuris simply says that knowledge of the legal implication of those facts or events in most cases is not relevant.[32] Considering Dan-Cohen's example, the Regina v. Prince[33] case, it is quite apparent from the unnecessarily complicated opinion of Lord Bramwell that his Lordship merely removes the age of the girl from the sphere of mens rea and makes it an objective condition of liability.[34] Dan-Cohen hopes to remedy vagueness, but merely removes a component of the crime to the layer of decision rules. Such a trend would, of course, lead ultimately to complete objective liability -that is, strict liability.[35]

- 289/290 -

It is not possible to accept that the defect of the principle of acting at one's peril as a conduct rule (which lies in its inability to prescribe a workable standard of conduct liability)[36] could be cured, if it were to be regarded as a decision rule.[37] Ignorance of facts - describing it, as one should, that is, as mistake of fact[38] - and ignorance of law are not interchangeable, and legality does not allow for easy intercourse between the two.[39] Changing a factual issue into a legal one, and thus changing the mistake of fact into ignorantia iuris erodes mens rea, and by this violates the culpability principle. The mistake of fact does not have any effect on the identity of the interpreter, but its confusion with ignorance of law obfuscates the issue.

The jurisprudence of the vagueness doctrine as developed in the United States provides some basis to start the enquiry into whether criminal laws should be created and interpreted assuming that the addressee and/or the interpreter is a layman (general ignorance) or a lawyer (specific ignorance). It cannot be the task of this work to examine the void-for-vagueness doctrine in detail, but a few explanatory remarks are essential.

In the United States, courts have long recognised the power to declare legislation unconstitutional on the basis of the doctrine of void-for-vagueness,[40] and

- 290/291 -

thus the vagueness doctrine has become the operational arm of legality.[41] The vagueness of a criminal norm might violate the principle of legality on several points.[42] However, in this respect, the reason described usually as fair warning or notice is significant.[43] Lack of fair warning that certain acts will be punished, or that more severe punishment will be imposed has long been regarded by American case law as a 'trap for the innocent',[44] which has meant, as the Lanzetta[45] Court put it that "no one may be required at peril of life, liberty or property to speculate as to the meaning of penal statutes. All are entitled to be informed to what the state commands or forbids."[46] Similarly, the Supreme Court stated in one of its even earlier decisions, Connally v. General Constr. Co.,[47] that "a statute which either forbids or requires the doing of an act in terms so vague that men of common intelligence must necessarily guess at its meaning

- 291/292 -

and differ to its application, violates the first essential of due process of law"[48] This sentiment of fair warning, therefore, has become a basic element of the due process doctrine enforced through the void-for-vagueness principle,[49] and was also incorporated into the MPC.[50]

The most precise restatement of the vagueness doctrine was rendered by Justice O'Connor for the majority of the Supreme Court in Kolender v. Lawson,[51] which struck down a California statute requiring persons who loitered or wandered on the streets to provide credible and reliable identification, and to account for their presence when requested by the police: "the void-for-vagueness doctrine requires that a penal statute define the criminal offence with sufficient definiteness that ordinary people can understand what conduct is prohibited and in a manner that does not encourage arbitrary and discriminatory enforcement... Although the doctrine focuses both on actual notice to citizens and arbitrary enforcement, we have recognized recently that the more important aspect of the vagueness doctrine is not actual notice, but the other principal element of the doctrine - the requirement that a legislature establish minimal guidelines to govern law enforcement."[52]

As a consequence, a statute might be vague in two different ways: it can be indeterminate and/or inaccessible.[53] A statute is indeterminate, when a significant number of possible situations are neither excluded by it nor included in it.[54] In case of inaccessibility, the question, whether a given situation is within the competence of the statute is believed to have an answer; the defect of the statute lies in the great difficulty of discovering what this answer is. For our present investigation this second shortcoming of a law is of interest, since as Justice Douglas put it, such a situation arises, when the law refers the citizen "to a comprehensive law library in order to ascertain what acts [are] prohibited."[55]

- 292/293 -

The Supreme Court has recognised two ways of curing an otherwise unconstitutional statute: a) by judicial reinterpretation, which would clarify the statute (called 'judicial gloss');[56] and b) by a so-called requirement of scienter.[57] The problem with judicial gloss is - as Dan-Cohen claims - that it often remedies indeterminacy only by increasing inaccessibility. This in turn hinders the communicative aspect of the norm to the public, and therefore jeopardises fair warning.[58] This claim has to be explored first.

Dan-Cohen points us to the United States Supreme Court decision of Rose v. Locke,[59] in which the Court upheld the constitutionality of a Tennessee statute prohibiting 'crimes against nature' and affirmed its application to an act of cunnilingus.[60] He further draws attention to the fact that the majority reasoning was based on analogies and inferences referring to old Tennessee decisions and those of other jurisdictions.[61] This, he purports, "implies that the defendant could have been expected, before engaging in sexual activities, to canvas the law libraries of various jurisdictions in search of the relevant decisions, and then to anticipate the convoluted process of legal reasoning that ultimately led even Supreme Courtjustices to opposite conclusions."[62]

Ultimately, Dan-Cohen reaches the same result as Jeffries, namely that, despite rhetoric to the contrary, the courts frequently do away with fair warning.[63] This, he concludes, might not be detrimental to the fair warning principle, because fair warning and the power control rationale do not apply to the same rules: the former relates to conduct rules, the latter to decision rules.[64] Therefore, vagueness must be examined with a view to the addressee of the relevant rule: "we must always ask: vague for whom?"[65]

- 293/294 -

This question highlights the crux of the issue. In answering, Dan-Cohen splits the addressees of the norm by dividing the criminal norm into decision rules and conduct rules. He claims on the basis of his example - the Locke decision -that building a judgement on prior judicial interpretations, as was done in Locke with respect to the expression 'crimes against nature', is acceptable, if understood as an elaboration on a decision rule.[66] But this does not exactly answer the question, as he himself must acknowledge: the fair warning problem is still unanswered.[67] He only moves the fair warning problem under the accessibility rationale, and suggests the application of the scienter, mens rea remedy.

From the point of view of legality, this is untenable. His explanation simply does not answer the problem of inaccessibility by suggesting the mens rea approach. Taking the Locke decision as an example, he suggests that common usage tied up with conventional morality, and not legal technicalities, will determine people's understanding of the normative message conveyed by the legal proscription of 'crimes against nature'. The court rightly implied that notwithstanding legal ambiguities and complexities, the defendant himself perceived his own conduct in terms of this linguistic and moral category and was, therefore, fairly warned.[68] In order to summarise his analysis of the vagueness doctrine and its cures he uses the table below:[69]

| Type of rule | Interest served by its clarity | Language in which it is conveyed | Cure for its vagueness |

| Conduct | Fair warning | Ordinary language | Scienter (mens rea) |

| Decision | Power control | Legal language | Judicial gloss |

Dan-Cohen finds it plausible that in some cases the law may seek to convey both the normative message expressed by common meanings of its terms, and the message rendered by the technical legal definition of the same terms.[70] Briefly, his idea is that if the ordinary meaning of words and concepts used by the norm in question could have been understood in the same way as later construed by the court, then the principle of fair warning was not violated.

- 294/295 -

The problem is that by this statement he presupposes that: 1) the concept in question has an ordinary language meaning; 2) the ordinary language meaning is the same as, or wider than the legal meaning of the term; 3) the offender was familiar with the law as it stood at the time of his act.

His answer to the first criticism is that conventional morality supplied the meaning of the term 'crimes against nature'.[71] In view of the changing nature of sexual morality[72] - leaving aside the issue of the connection between morality and law - Dan-Cohen's argument cannot be sustained. This he acknowledges, without trying to offer further support to his argument in this respect.[73]

His second presumption cannot be upheld either. The very nature of vagueness is that one cannot tell the actual scope of a definition within the norm. Therefore the second postulate can only be valid, if applied in conjunction with a compulsory strict interpretation by the courts to ensure that their legal understanding is narrower, than the ordinary language meaning of the term in question. This runs counter to the Locke decision. Dan-Cohen acknowledges this necessary discrepancy between the official's and the citizen's understanding, and suggests that his approach meets the requirement of the rule of law if " decision rules are more lenient than conduct rules."[74] However, such a solution would not only make a general rule out of the 'chilling effect'[75] - that is, it would restrain such activities by conduct rules, which in the end would not be punishable because of the decision rules - but would be untenable in real life,

- 295/296 -

save for a complete acoustic separation.[76] Hiding the defence of duress, for example, from the general public does not work,[77] because it will only be hidden until the first decision relying on it; if it is subsequently hidden, and if it can be altered, it will already upset expectations.

Is it then true that the void-for-vagueness analysis "address[es] itself to the form of regulation, without reference to the ultimate amenability... of its subject"?[78] On close examination, the fair warning requirement as applied by the courts is formal.[79] Although, contrary to a widely shared belief, ignorance of law is exculpatory in some cases,[80] the main rule remains that ignorantia iuris neminem excusat.

The consequence of this for the present undertaking is that general ignorance of law is not believed to be under the void-for-vagueness doctrine in the United States, and does not fall under the violation of Due Process. Therefore, it is not regarded as excluding criminal liability. This statement is much supported by those exceptions, which cater to an ignorance defence.[81] The cases, where such a defence is admissible involve reliance in good faith on official advice about the law. This official statement on the law moves the ignorance from being general ignorance to special blameless ignorance.

Although Jeffries maintains that "one would think that a system organized around the requirement of fair warning would have to take into account cases where, through no fault of the accused, such warning was not received"[82] as the law stands fair warning equals the hypothetical 'lawyer's notice'.[83] In terms of legality this implies that if a) there is no ignorance about the law on the part of the offender; or a) there is blameworthy ignorance on the part of the of-

- 296/297 -

fender, because he did not seek any legal advice at all; or b) the cause of his blameworthy ignorance is that he did not seek official advice, and the 'private' advice (any legal advice independent of the government)[84] provided for him was erroneous;

then criminal culpability can be imposed, without violating legality under the law of the United States.

This in turn affects our primary question: the identity of the interpreter. The outer limit of accessibility is not determined by the principle that general ignorance is exculpatory - that is, the ordinary citizen must be able to understand the law. The confines of accessibility are drawn between blameworthy and blameless special ignorance, where mistaken official advice, retroactivity and vagueness bar professional foresight of the consequences. These will mark out the ground, which cannot be claimed by criminal norms or their application, if legality is to be heeded. It follows that under the law of the United States the interpreter, as a minimum, must be understood as a professional; and the answer to the question 'vague for whom?' is 'for a lawyer'.[85]

Jeffries strongly criticises this so-called 'lawyer's notice', but is similarly opposed to arguments, which maintain that exculpation for ignorance of the law would "encourage ignorance where knowledge is socially desirable".[86] He advocates a solution that would introduce a new standard, by which the blameworthiness of ignorance could be measured. His test of "would an ordinary law-abiding person in the actor's situation have had reason to behave differently"[87] is a narrowed-down version of general ignorance.

To examine the feasibility of such a standard is outside the scope of this work, but a short comment on it at this stage is appropriate. The suggested test is not only extremely vague - which is in itself paradoxical - but seems to move this complex question of culpability onto factual grounds. A hypothetical case will further emphasise these doubts. Let us say that in State A there is no motorway speed limit (for example, Germany), and in State B the motorway speed limit is 130 km/h (for example, Hungary). D drives from State A to State B (through Austria of course), and in State B, whilst overtaking at a speed of 160 km/h collides with car X, which changed lanes in front of D's car. The passenger in car X is killed. The evidence shows that if D had observed the speed limit of

- 297/298 -

State B, he could have slowed down sufficiently to avert collision, and that the driver of car X assumed that D is driving according to the speed limit and adjusted his actions accordingly. D defends himself, relying on a test similar to that advocated by Jeffries.[88] He introduces evidence suggesting that he had not come into conflict with criminal law before, and that the average overtaking speed on motorways in State A is higher than 160 km/h. Additionally, the vast majority of drivers from State A violate the speed limit in State B; moreover, he actually reduced his speed compared to his normal driving habit for safety reasons. He claims that the exact speed limit in State B was unknown to him.

Instead of dissecting the case above, it will be assumed that it speaks for itself. Nevertheless, Jeffries is not alone in his critical view of the vagueness doctrine. The point has been also made in another jurisdiction, which although under strong American influence, resisted the import of the vagueness doctrine. "It has been clear since the decision of the Canadian Supreme Court in Reference re ss. 193 & 195.1 (1)(c) of the Criminal Code (Canada) ('Prostitution reference') (1990)[89] that there is no similar doctrine in Canada grounded in the principle of fundamental justice guaranteed by section 7 of the [Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms]."[90] In Lebeau the court, nevertheless, stated that "the void-for-vagueness doctrine is not to be applied to the bare words of the statutory provision, but rather to the provision as interpreted and applied in the judicial decisions.' The protection of the principle of fair notice has still been substantially weakened, because the Canadian Supreme Court and the Ontario Court of Appeal place so much emphasis on clarification through judicial interpretation, and the standards vary from 'persons of common intelligence' to 'jurists of unusual diligence'; the focus is too much on specialised legal knowledge, even though it should not be open to the courts to prescribe ex post facto a 'sensible meaning' to vague statutory provisions.[91]

Taking all factors into consideration it seems that, when talking of an ordinary citizen, Canadian criminal law does not actually mean simply an ordinary citizen, but rather a layman taking legal advice if need be.

This approach closely corresponds to the test developed under the European Convention on Human Rights.[92] Articles 8-11 of the Convention set out in their

- 298/299 -

second paragraphs the conditions under which the State may interfere with enjoyment of the rights described and protected by the first paragraphs of the same Articles.[93] These limitations are allowed, if they are "in accordance with the law" or "prescribed by law', and are "necessary in a democratic society" for the protection of one of the objectives set out in the second paragraph.[94] Whilst on the face of it there seems to be a difference between the formulations of Article 8 (2) "in accordance with the law", and that of Articles 9 (2) - 11 (2) "prescribed by law", in Malone v. the United Kingdom[95] the Court confirmed that both formulations are to be read in the same way.[96] Describing them extremely briefly, these two concepts mean that as a minimum the State must ground its interference with protected rights in some specific legal rule, which authorises this interference.[97]

The examination of the relevant jurisprudence of the concept "prescribed by law" will enable the finding of an answer to the question of the relationship between legality and the addressee of the criminal norm under Convention law. Legality in this sense, according to the Court, is not satisfied merely by appropriate domestic law-making. It is indispensable that it should conform to the principle of the rule of law, which is expressly mentioned in the Preamble to the Statute of the Council of Europe[98] and the Convention.[99] The notion of 'law' - like most of the Convention concepts[100] - is autonomous.[101] 'Law' has been interpreted by the Court as encompassing a wide range of rules, from delegated regulations[102] to unwritten law.[103] Any such rule must, however, be

- 299/300 -

based on the authority of Parliament, because only this will ensure sufficient protection against the executive and will ensure foreseeability.[104] This approach has been criticised for not meeting the requirements of formal legality: that is,

it regards as laws even those rules, which have not secured democratic legitimacy.[105]

In addition to the formal legality requirement of democratic legitimisation, the Court added to the notion of 'law' two further conditions, which are best described in the first Sunday Times case. For the present purposes only the second of the criteria is of importance. According to this, "a norm cannot be regarded as a 'law' unless it is formulated with sufficient precision to enable the citizen to regulate his conduct: he must be able - if need be with appropriate advice -to foresee, to a degree that is reasonable in the circumstances, the consequences which a given action may entail.'[106]

It is quite apparent now that under European human rights law legality is already satisfied, if the understanding of the text of the norm requires legal advice.[107] The same is true of common law, which practically is only available through legal advice. The Court specifically addressed this issue inasmuch as it stated that "it would clearly be contrary to the intention of the drafters of the Convention to hold that a restriction imposed by virtue of the common law is not 'prescribed by law'...this would deprive the common law" states of the protection provided by paragraph (2) of these Articles and "strike at the very roots of that State's legal system".[108]

In Kokkinakis v. Greece,[109] whilst examining an alleged violation of Article 7 of the Convention, the Court restated the need for clear definition of criminal norms, but added only that this is satisfied "where the individual can know from the wording of the relevant provision and, if need be, with the assistance of the court's interpretation of it, what acts and omissions will make him liable".[110] Additionally, in Wingrove v. United Kingdom[111], the Commission

- 300/301 -

recalled that in its opinion in the case commonly known as the Gay News case,[112] it held that the law of blasphemy as defined by the House of Lords at that time was sufficiently accessible and foreseeable.[113] It also observed that considerable legal advice was available to the applicant.[114] The Court further remarked upon the availability of legal advice,[115] which indicates that both institutions attach importance to the norm being judged from a professional's point of view. This statement should be interpreted in the light of the Sunday Times judgement,[116] as indeed the court itself did in Wingrove.[117] It is apparent, therefore, that foreseeability and accessibility are satisfied, if the law is accessible to a legal professional and its implications can be foreseen by him through interpretation.

Finally, in Worm v. Austria[118] the Court reiterated "that the relevant national law must be formulated with sufficient precision to enable the persons concerned - if need be with appropriate legal advice - to foresee, to a degree that is reasonable in the circumstances, the consequences, which a given action may entail."[119]

- 301/302 -

It will have been noticed that a not negligible number of significant cases decided by the European Court of Human Rights involved the United Kingdom, or more precisely English law. Although qualms about the common law not qualifying as law under the Convention in general, as well as common law criminal offences not conforming to the Convention in particular, have been laid to rest,[120] the problem of the inherent retrospectivity of the case law system seems to prevent - even after C. v. D.P.P[121] - a complete reconciliation with prospectivity in criminal law - that is, a requirement of the principle of legality.[122] This, however, is not singularly a feature of common law; in every legal system "legitimate interpretation passes by imperceptible shades into so-called illegitimate extension."[123]

Legality in this respect, as it seems, must be defined with some care in English law.[124] Allan suggests - relying on Hall[125] and authoritative decisions[126] - that in order to understand legality as a condition, which requires that the range of policy represented by a statute should be limited by the actual meaning of the words, the words should be, as far as possible, interpreted by giving preference to the audience's preconceptions and assumptions. It is part of the rule of law that legislation should be construed in the light of constitutional standards and principles. Therefore, legality requires a strict construction of penal provisions, where there is a genuine doubt about their scope.[127]

The principle of strict construction, however, is not only widely disputed as far as its existence and proper application is concerned,[128] but does not clarify the

- 302/303 -

situation of the addressee. It is possible to understand this principle as one, which says that "the citizen...is entitled to act in reliance on the existing law -both common and statute - until it is changed with reasonable certainty and precision.[129]

Such views have been advocated by Glanville Williams, who has claimed that " criminal law...is not meant for lawyers only, but is addressed to all classes of society..."![130] One can only agree with the expression of the universality of criminal law, but does it follow as a requirement of legality that the addressee has to understand the message?

Looking at the decision of the House of Lords in Shaw v. D.P.P.,[131] which Ashworth describes as the modern apotheosis of the conflict between the nonretroactivity principle and the functioning of criminal law,[132] the answer seems to be no. The case also touches upon the issue of general and special ignorance. Shaw published the names, addresses and nude photographs of prostitutes, and in some cases an indication of their practices. The prosecution indicted Shaw with conspiracy to corrupt public morals, in addition to two other charges, under the Sexual Offences Act of 1956 and the Obscene Publications Act 1959.[133] The House of Lords upheld the validity of the indictment, despite any clear precedents that such an offence actually existed. It reasoned that conduct intended and calculated to corrupt public morals is indictable at common law.[134] Shaw relied on legal advice, on the basis of which he rightly presumed - and not because the advice he was given was mistaken - that his conduct was not criminal.[135]

- 303/304 -

For those, who thought Shaw was an unfortunate part of legal history, R. v. R.[136] came as a surprise. In this case the House of Lords abolished the marital exception to rape with retroactive effect. As A.T.H. Smith points out, there was no doubt that the solution was doubtful: the Criminal Revision Committee decided as recently as 1984 that it could not make a unanimous recommendation on the issue;[137] moreover, the Law Commission had only tentatively, in a Green Paper, recommended that the law in this field should be reformed. Parliament had rejected the opportunity to clear up this difficult question in the Sexual Offences Act 1976, and had not removed a suggestive phrase until the Criminal Justice and Public Order Act 1994.[138] The question, therefore, is not whether the minimum standard of special blameless ignorance is sufficient for legality in English criminal law, but rather whether this minimum is met at all in some cases.

With regard to the cases decided by the European Court of Human Rights, one is justified in stating that legality under English constitutional and criminal law differentiates between the universal addressee and the interpreter - the latter being at best a member of the legal profession.

In most jurisdictions - with the possible exception of the European Court of Human Rights' jurisprudence, which was prudently cautious - there seems to be a gap not only between the citizen and the interpreter, but also between the declaration of the citizen's right to understand criminal law, and the actual constitutionally enforceable requirement of exculpation for blameless special ignorance. Germany is certainly no exception to this claim.

The German Constitutional Court emphasised several times that "everybody should be able to foresee, which behaviours are forbidden and threatened with penalty".[139] In the Sitzdemonstration[140] (Picketing) decision the Constitutional Court reiterated its observation that the constitutional requirement embedded in Article 103 II GG compels the legislature to define the conditions of criminal liability in such a concrete manner that the scope and field of application of crime-definitions (Tatbestand) should derive from the wording (Wortlaut), or at least be recognisable and discoverable through interpretation.[141] The Court

- 304/305 -

identified two reasons for this principle. Firstly, it should enable the norm addressee to foresee what behaviour is punishable under criminal law and what punishment might be accorded to it. Secondly, it ensures that the legislature decides beforehand what behaviour deserves a penal response, and not the courts afterwards.[142] The Badge decision[143] equates the addressee with the interpreter by stating that everybody should be able to foresee the consequences of his action.[144] These approaches omit the first step in legal interpretation theory: to acknowledge the inescapable necessity of interpretation, and that such will result in an unavoidably complicated body of case law in any jurisdiction.

Nevertheless, referring to two previous cases[145] the Court stated again that the certainty of a criminal statute must be judged primarily on the wording [Wortlaut] of the definition of the crime [Tatbestand], which should be recognisable and understandable to the addressee.[146] The Court further declared that "because the object of statutory interpretation can always and only be the statutory text, this represents the standard criterion. The possible word-sense [Wortsinn] of the statute marks the outer limit of allowable judicial interpretation (compare BGHSt 4, 144 [148]). If, as shown, Article 103 II GG demands recognisability and foreseeability of a prescription of punishment or fine for the addressee, than this can only mean that the word-sense must be defined from the viewpoint of the citizen ...If only an 'interpretation' transgressing the recognisable word-sense of the rule leads to the result of punishing a conduct, then this must not burden the citizen."[147] From this follows another rule of

- 305/306 -

interpretation, namely the priority of arguments based on the colloquial meaning of a term over arguments derived from a technical nomenclature.[148]

The Court addressed the issue of the identity of the interpreter from another angle in the Berlin Wall Snipers (Mauerschützen) decision:[149] the culpability principle (Schuldgrundsatz).[150] The Constitutional Court had already described punishment as a "disapproving reaction of the Sovereign to a culpable [schuldhaftes] behaviour",[151] by which the offender is blamed for an unlawful conduct.[152] This principle - 'no punishment without culpability' - as far as criminal law is concerned, is rooted in the constitutionally protected right to human dignity and self-responsibility (Eigenverantwortlichkeit) and the rule of law principle set out in Articles 1 I and 2 I GG. These principles must be respected by the legislature, when shaping criminal law.[153] The culpability principle can also be placed in the penumbra of Article 130 II GG as one of its material guarantees.[154] Consequently, the culpability principle, as a principle which essentially defines the extent of the State's penalisation power, has constitutional rank.[155] It places a duty upon courts to impose in individual cases sentences proportionate to the culpability of the offender.[156]

The Constitutional Court went on to say that in cases, in which the offenders were previously living in a legal and social system, which no longer existed at the time of the criminal proceedings against them, and in which the offenders were bound on several levels in a system of order and duty when committing the acts, then their individual culpability must be thoroughly vetted.[157] Significantly, the Constitutional Court also observed that undoubtedly questions can be raised about the ability of the defendants to recognise the criminal quality of their actions, especially in view of the fact that the state leadership of East Germany extended the concept of criminal defence to exculpating the border guards, who shot people at the Berlin Wall. It is, therefore, not self-evident that boundaries of non-criminal activity were apparent to an average soldier. It

- 306/307 -

would be - the Court continued - untenable under the culpability principle to explain the obviousness of the criminality of their acts simply by pointing to the severe human rights violation, which their action (objectively) entailed.[158] The BGH in one of the Berlin Wall Sniper decisions found that the intentional killing through continuous gun fire of an unarmed escapee, who was - apart from the obvious offence of violating the borders - innocent, was such a horrible act that the violation of the prohibition to kill another human being was apparent and recognisable even to an indoctrinated person.[159] Whilst upholding the decisions of the BGH, the Constitutional Court objected to the obvious lack of a more detailed explanation from the BGH as to why an individual soldier was still able, given the circumstances of his upbringing (indoctrination, etc.), to recognise without dubiety the criminal character of his actions.[160]

The concerns and observations of the Constitutional Court about the culpability principle in its Berlin Wall Snipers decision are strikingly familiar to the scienter cure of vagueness applied by the American Supreme Court. Despite the elaborate argument, the disregard for the culpability principle is apparent: not only did the soldiers receive official advice that their action was not criminal, but they were also encouraged by their Government to shoot, and received promotion if they successfully hindered someone's escape. It is quite obvious that contrary to correct official advice they were retroactively punished and the strongest form of blameless ignorance of law was disregarded by the German courts, which effectively imposed absolute criminal liability.

There are two further constitutional principles in German law, which affect the relationship between criminal norm and its addressee. The requirement of certainty (Bestimmtheitsgebot) can be deduced from all the sub-concepts of the rule of law principle according to German constitutional theory. It gives priority to written law, because it is by this that citizens can find out for themselves what the law is.[161] Additionally, the trust protection principle (Prinzip des Vertrauensschutzes) is also part of the rule of law principle, and should be understood as the protection of the individual from the unforeseeable consequences of his action.[162]

It is not only rare historical situations that test the law to its extreme. The question, whether official advice is exculpatory is often raised by the laws on contravention and civil law. The editors of the Austrian General Civil Code (ABGB) were able to presume that ignorance of a properly published statute

- 307/308 -

will not exclude blame.[163] The civil law of today, however, is of the opinion that, with regard to the flood of statutes, ignorance of law and mistake in law in the narrow sense can only be blamed on a person, if knowledge of the law could have been reasonably expected.[164]

Similarly, according to Article 5 of the Statute on Administrative Offences (VStG), it is an exculpatory factor, if the offender is not aware of an administrative regulation; he cannot be blamed for this ignorance, if additionally he could not have recognised the unlawful character of his action without knowledge of the administrative regulation in question. The mistaken interpretation of an administrative regulation - that is, mistake of law in the narrow sense -falls under the same heading as ignorance of administrative law.[165]

Any culpability must be based on the refusal to follow the command of criminal law. This, however, presupposes the recognisability of the existence of a command, which does not entail only the mere existence of the command, but also perception of its content.[166] If it is impossible to ascertain the normative content of a criminal norm because of the large number of possible divergent interpretations, the objective unlawfulness of a conduct, which nevertheless breaches the criminal norm may diminish: "the ascertained high degree of vagueness of the rule deprives the norm of its legal quality".[167]

On the other hand, there appears to be a contrary development, both in German and Austrian jurisprudence, which is very similar indeed to the 'thin ice' principle set out in English law, but goes even further. A person, who is aware that some authorities in the applicable case law regard a certain activity as unlawful (that is, the precedents are not conclusive, or in other words, the law is vague), but still performs this activity, behaves quasi-intentionally and may not later invoke ignorance or mistake in law as a defence.[168] What is of interest now is that as a principle, and not only under exceptional historical circumstances or in connection with extremely hideous crimes, even correct specialised legal advice cannot exculpate if the vagueness of the law was apparent and the law could have been construed as criminalising the activity in question.[169] Whether

- 308/309 -

this approach is acceptable is highly disputed. Such a view could rightly be compared to the Nazi laws, which condemned whatever was deserving of punishment according to "fundamental conceptions of a penal law and sound popular feeling", and would condone Shaw v. D.P.P,[170] as Hart has pointed out.[171] If this rule were to be adopted, the very question of whose interpretation should be regarded as a standard, when examining the legality of a criminal norm would become pointless, since only acts performed in good faith following an official's erroneous advice might exculpate the defendant. This would indeed reverse the fundamental principle of the rule of law, which states that behaviour, which is not forbidden is allowed. Instead, there would be a rule under which only expressly allowed behaviour could guarantee freedom from possible criminal consequences. This is completely unacceptable under any notion of legality.

The above presumption is not, however, equivalent to the duty imposed by the case law of concerning administrative law in Austria for the individual addressee to be informed of the law (Erkundungspflicht). This requires him to contact the relevant authorities or other professional persons or organisation qualified to give appropriate advice.[172] This also appears to be the principle in criminal law, if one wishes to be certain that the activity to be undertaken will not run contrary to criminal prohibitions. Finally, Lewisch observes that the dividing line between allowed and not allowed interpretation is marked out by the word-limit of the definition of the criminal offence (Wortlautschranke). This is for a functional reason: criminal law can exercise its guarantee function if a person already conversant with both the language and the law can define with some certainty the sphere of activity which is definitely not criminalised.[173]

The experience of the jurisdictions examined above leads to two fundamental observations: 1) as Dan-Cohen suggests, the law is not reducible to a simple rule, not even to a rule stating that ignorance of law is not a defence;[174] 2) a rule still seems to outline itself, however: there is a minimum excuse for ignorance if, contrary to correct legal advice, consequences could not have been foreseen (retroactivity, vagueness), or ignorance is caused by mistaken governmental advice (officials acting in their official capacity).

- 309/310 -

This too has a profound impact on this enquiry. It seems that, contrary to the rhetoric of courts and some academic writings, ignorance of law is only constitutionally accepted as exculpating one from criminal liability, when the law is so vague as to disable legal professionals from foreseeing the outcome of the activity in question, or the law has been retrospectively imposed. Addressees of criminal norms are not the same as people, whose understanding of those norms should be scrutinised, when looking at the legality of criminal norms or their application. It is 'professional advice', in the words of the European Court of Human Rights, which indicates best that the legal professional should be the standard in gauging legality of criminal norms. Obviously, laws, which are comprehensible to non-legally educated persons, do not raise questions of constitutionality in this respect. Suggestions that all criminal laws must be comprehensible to the average citizen must be discarded as lacking understanding of the theoretical basis of the norm-interpretation. Similarly, views, which would limit legality to the specialised understanding of officials of the government, are contrary to the basic principles of the rule of law.

It follows that the methodologically correct approach is not to examine a criminal law from an ordinary citizen's point of view. This would lead to a paradox, where one would have to ask what is meant by an 'ordinary citizen' in the estimation of an ordinary citizen. Secondly, to use the standard suggested by Jeffries, the question "would an ordinarily law-abiding person in the actor's situation have had reason to behave differently?"[175] equates criminal law with the majority's morality. Not disclaiming D. Smith's argument on the idolatry of constitutional adjudication, it is correct to state that a Dworkinian moral reading of a constitution[176] does not amount to a majoritarian imposition of values,[177] be that in the form of judicial guessing of an ordinary law-abiding person's beliefs.

- 310/311 -

Summary - The Identity of the Interpreter of Criminal Norms

The significance of the author in the interpretative enterprise has been subject to intense study in legal literature, however, almost no attention has been paid to the addressee of a norm from the point of view of legality. Criminal norms are addressed to everybody; no human being can be above them. Thus, the universality of criminal law makes every person under its jurisdiction an addressee. A question then has to be asked: if one is to decide upon the constitutionality of a criminal norm, or the application of a criminal norm, both the constitutional criteria and the criminal norm or its application have to be understood. Does legality place any requirements on the methodology of this understanding? That is, is interpretation to be undertaken with a view to the universality of the addressee? In other words, if a criminal norm or its interpretation should conform to the requirements of legality, is it necessary to take into consideration certain attributes of the addressee, and/or the final interpreter? This problem leads to two further points: who is really the addressee of a criminal norm; and what effect does he have on the legality of criminal norms and their interpretation? This study tries to find an answer to these questions, and also looks at the problem of ignorantia iuris neminem excusat, as it is presented at the crossroad of interpretation and legality of criminal norms.

Resümee - Die Identität des Auslegers von strafrechtlichen Normen

Die Bedeutung des Autors im Unternehmen der Rechtsauslegung wurde in der Rechtsliteratur bereits ausführlich untersucht, dem Adressaten der Norm wurde jedoch aus dem Aspekt der Gesetzlichkeit bisher kaum Aufmerksamkeit geschenkt. Strafrechtliche Normen sind an alle adressiert, kein Mensch kann über ihnen stehen. Die Universalität des Strafrechts macht jede Person in seinem Zuständigkeitsbereich zum Adressaten. Dann stellt sich jedoch die Frage: falls

- 311/312 -

über die Verfassungsmäßigkeit, oder die Anwendung einer strafrechtlichen Norm entschieden werden soll, müssen sowohl das Kriterium der Verfassungsmäßigkeit, als auch die strafrechtliche Norm, oder ihre Anwendung richtig verstanden werden. Stellt die Gesetzlichkeit irgendwelche Anforderungen an die Methodologie dieses Verstehens? Das heißt, soll die Interpretation die Universalität des Adressaten vor Augen halten? Mit anderen Worten, wenn eine strafrechtliche Norm oder ihre Auslegung die Anforderungen der Gesetzlichkeit erfüllen soll, sollten dabei gewisse Eigenschaften des Adressaten, und/oder des endgültigen Auslegers in Erwägung gezogen werden? Dieses Problem leitet zu einer anderen Frage über: wer ist der tatsächliche Adressat einer strafrechtlichen Norm, und was für einen Einfluss übt er auf die Gesetzlichkeit der strafrechtlichen Normen und deren Auslegung aus? Diese Studie versucht eine Antwort auf diese Fragen zu finden und befasst sich mit dem Problem "ignorantia iuris neminem excusat", so wie es an der Kreuzung von Auslegung und Gesetzlichkeit der strafrechtlichen Normen erscheint. ■

NOTES

[1] As Kelsen puts it: "No norm without a norm-positing authority, and no norm without an addressee." Kelsen, H. (1991) General theory of norms (trans: Hartney, M.). Oxford: Clarendon Press, 28.

[2] On German law see for example Alexy, R. and Dreier, R. (1991) Statutory interpretation in the Federal Republic of Germany. In: MacCormick, N. and Summers, R.S. (eds.) Interpreting statutes: a comparative study, 73. Aldershot and Brookfield: Dartmouth Publishing Ltd.; Brugger, W. (1994) Legal interpretation, schools of jurisprudence, and anthropology: some remarks from a German point of view. American Journal of Comparative Law 42: 395.; Schacter, J. S. (1995) Metademocracy: the changing structure of legitimacy in statutory interpretation. Harvard Law Review 108: 592. The huge body of work within the American literature makes it difficult to provide general references. Therefore, only a few examples will be listed here: Ackerman, B. A. (1991) We the people. Cambridge, Mass. and London: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 142-50; Bork, R. (1990) The tempting of America: the political seduction of the law. London: Sinclair-Stevenson, 74-84; Knapp, S. and Michaels, W.B. (1992) Intention, identity and the constitution: a response to David Hoy. In: Leyh, G. Legal hermeneutics: history, theory, and practice, 187. Berkeley, Los Angeles, Oxford: University of California Press; Smith, S.D. (1993) Idolatry in constitutional interpretation. Virginia Law Review 79: 583.

[3] This does not mean that the author is not aware of the problem, but the latest findings on legality and interpretation have not been analysed with reference to each other. Consider Ashworth, A. (1991) Interpreting criminal statutes: a crisis of legality? Law Quarterly Review. 107: 419.; Ashworth, A. (1995) Principles of criminal law. 2[nd] ed. Oxford: Clarendon Press; New York: Oxford University Press. 67-74; Dworkin, R. (1985) A matter of principle. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, Chapter 1; Dworkin, R. (1978) Taking rights seriously (New impression, with a reply to critics). London: Duckworth, 131-149; Dworkin, R. (1991) Law's Empire. London: Fontana Press. (1[st] ed. 1986), 313-320, 359-369; Dworkin, R. (1996) Freedom's law: the moral reading of the American Constitution. Oxford: Clarendon Press; New York: Oxford University Press. Jeffries raises the issue briefly in his article: Jeffries, J. C. Jr. (1985), Legality, vagueness, and the constitution of penal statutes. Virginia Law Review 71: 189., 205-223; Kelman, M (1981) Interpretive construction in the substantive criminal law. Stanford Law Review 33:591.; Lewisch, P. (1993) Verfassung und Strafrecht. Verfassungsrechtliche Schranken der Strafgesetzgebung. Wien: Universitätsverlag.[.]

[4] Speaking about a criminal code, Thomas observes that "politically, a (it) may acquire symbolic significance as an expression of national unity...Morally, (it) may amount to a concrete manifestation of the judgement of the community on the central values, which bind it together and serve notice on the citizen of the limits of permissible behaviour". Thomas, D: A. (1978) Form and function in criminal law. In: Glazebrook, P. R. (ed.) Reshaping the criminal law: essays in honour of Glanville Williams, 21. London: Stevens & Sons, 21.

[5] Allen, F.A. (1987) The erosion of legality in American criminal justice: some latter-day adventures of the nulla poena principle. Arizona Law Review 29: 385; Arndt, H-W. (1974) Probleme der rückwirkender Rechtsprechungsänderung; dargestellt anhand der Rechtsprechung des Bundesgerichtshofes, des Bundesfinanzhofes, des Bundesarbeitsgerichts und des Bundesverfassungsgerichts. Frankfurt am Main: Athenäum Verlag; Ashworth (1991); Calliess, R-P. (1985) Der strafrechtliche Nötigungstatbestand und das verfassungsrechtliche Gebot der Tatbestandsbestimmtheit. Neue Juristische Wochenschrift 27: 1506; Dannecker, G. (1996) Strafrecht in der Europäischen Gemeinschaft. Eine herausforderung für Strafrechtsdogmatik. Kriminologie und Verfassungsrecht Juristenzeitung 18: 869.; Hillgruber, C. (1996) Richterliche Rechtsfortbildung als Verfassungsproblem. Juristenzeitung 3: 118; Jeffries (1985); Krey, V. (1977) Studien zum Gesetzesvorbehalt im Strafrecht. Eine Einführung in die Problematik des Analogieverbots. Berlin: Duncker & Humblot; Krey, V. (1989) Gesetzestreue und Strafrecht. Schranken richterlicher Rechtsfortbildung, Zeitschrift für die gesamte Strafrechtswissenschaft 101: 838; Lewisch (1993), chapter II.C); Neumann, F. (1991) Rückwirkungsverbot bei belastenden Rechtsprechungsänderungen der Strafgerichte? Zeitschrift für die gesamte Strafrechtswissenschaft 103: 331; Robbers, G. (1988) Rückwirkende Rechtsprechungsänderung. Juristenzeitung 481; Sax, W. (1956) Das strafrechtliche "Analogieverbot": eine methodologische Untersuchung über die Grenze der Auslegung im geltenden deutschen Strafrecht. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht; Schroth, U. (1983) Theorie und Praxis subjektiver Auslegung im Strafrecht. Berlin: Duncker & Humblot; Schreiber, H.-L. (1979) Jewish law and decision-making: a study through time. Philadelphia: Temple University Press; Smith, A. T. H. (1984) Judicial law making in the criminal law. The Law Quarterly Review 100: 46; Strassburg, W. (1970) Rückwirkugsverbot und Änderung der Rechtsprechung in Strafsachen. Zeitschrift für die gesamte Strafrechtswissenschaft 82: 948.; Styles, S. C. (1993) Something to declare: a defence of the declaratory power of the High Court of Justiciary. In: Hunter, R.F. (ed.) Justice and Crime: essays in honour of The Right Honourable The Lord Emslie, M.B.E., P.C., LL.D., F.R.S.E, 211. Edinburgh: T&T Clark; Wang, S. (1995) The judicial explanation in Chinese criminal law. American Journal of Comparative Law 43: 569; Willock, I. D. (1996) Judges at work: making law and keeping to the law. The Juridical Review V: 237; Schmidt-Assmann in Maunz-Düring, Komm. z. GG. Art. 103 Rdnr. 178 et seq. In general see Dworkin (1978), 31-39, 68-71, 137-140; Dworkin, R. (1991) Law's Empire. London: Fontana Press, esp. chapters, 9-10;

[6] For example see Ashworth (1991), 441-445; Ashworth (1995), 71-72; Erb, V. (1996) Die Schutzfunktion von Art. 103 Abs. 2 GG bei Rechtfertigungsgrunden: zur Reichweite des Grundsatzes nullum crimen sine lege unter besonderer Berücksichtigung der "Mauerschützen-Fälle" und der "sozialethischen Einschränkungen". Zeitschrift für die gesamte Strafrechtswissenschaft. 108: 266., 274-275; Jeffries (1985), 205-212, Papier H-J. and Möller, J. (1997), Das Bestimmtheitsgebot und seine Durchsetzung. Archiv des öffentlichen Rechts 122: 177., 181; Roxin, C. (1992) Strafrecht, Allgemeiner Teil, Band I. 2[nd] ed. München: C.H.Beck'sche Verlagsbuchhandlung, 116-117.

[7] Dan-Cohen (1984), 625-677, 626. Dan-Cohen cites Bentham, J. (1948) A fragment on government: an introduction to the principles of morals and legislation (ed. Harrison, W.). Oxford: Blackwell. The example given by Bentham is "Let no man steal" as a conduct rule, and "Let the judge cause whoever is convicted of stealing to be hanged" as a decision rule. He maintained that the imperative law and the punitory law attached to it are completely distinct. Bentham (1948), 430.

[8] Dan-Cohen (1984), 627.

[9] Id.

[10] Id., 629.

[11] Dicey, nevertheless emphasised the legal equality of officials and ordinary citizens, and stated that the "universal subjection of all classes to one law administered by the ordinary courts" is the basis of the rule of law. Dicey, A.V. (1959) An introduction to the study of the law of the Constitution. 10[th] ed. Basingstoke: Macmillan Education, 193. The distinction between laws addressed to officials and those to citizens reminds one of the Hartian differentiation, although it is necessary to note that Hart's usage of the terms 'citizens' and 'officials' is somewhat more complicated. Hart, H. L. A. (1994) The concept of law. 2[nd] ed. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 90-8. He points to "two minimum conditions necessary and sufficient for the existence of a legal system. On the one hand...rules of behaviour...must be generally obeyed, and, on the other hand...rules of recognition must be effectively accepted as...standards of official behaviour by its officials." He concludes that the existence of a legal system hinges on the obedience by ordinary citizens and the acceptance by the officials of secondary rules. Id., 116-117.

[12] "The legal norm is applied when the prescribed sanction - punishment or execution of judgment - is directed at behaviour contrary to the norm. The validity of a norm - i.e. its specific existence - consists in the norm to be observed, and if not observed, then applied." Kelsen (1991), 3. In the first addition of his Reine Rechtslehre he phrased this concept as follows: "what makes certain behaviour a delict is simply and solely that this behaviour is set in the reconstructed legal norm as the condition of a specific consequence, it is simply and solely that the positive legal system responds to this behaviour with a coercive act." Kelsen, H. (1934) Collective and individual responsibility in international law with particular regard to the punishment of war criminals. California Law Review 31: 530., 26. Kelsen maintained this position also in the second revised edition of his Pure Theory. Kelsen, H. (1967) Pure theory of Law (trans. Knight, M.). Berkeley Cal., Los Angeles: University of California Press, 33-35. He also put forward a similar argumentation citing as an example the "One shall not steal" maxim and observing that "if at all existent, the first norm is contained in the second, which is the only genuine legal norm." Kelsen, H. (1961) General theory of law and state (trans. Wedberg, A.). New York: Russell and Russell, 61.

[13] Austin, J. (1998) The province of jurisprudence determined (eds: Campbell, D. and Thomas, P.) Aldershot and Brookfield: Dartmouth, 18.

[14] Dan-Cohen (1984), 639.

[15] Fletcher, G. (1978) Rethinking Criminal Law. Boston: Little, Brown, 17; Fletcher (1985) The right and the reasonable. Harvard Law Review 98: 949, 312-316. Samaha refers to the wide variations, which exist between different theorists and jurisdictions on questions of duress. Samaha, J. (1990) Criminal Law. 3[rd] ed., St Paul: West Publishing Co, 235; MPC, Vol. I, 372 et seq. The effect of case law on defences was considered by A.T.H. Smith as well. Smith (1984), 63-67. For a German account of the same problem see Erb (1996); Kaufmann, A. (1995), Die Radbruchsche Formel vom gesetzlichen Unrecht und vom übergesetzlichen Recht in der Diskussion um das im Namen der DDR begangene Unrecht. Neue Juristische Wochenschrift 48: 81., 83; Kirchhof, P. (1986) Die Aufgaben des Bundesverfassungsgerichts in Zeiten des Umbruchs. Neue Juristische Wochenschrift 23: 1497.

[16] Dan-Cohen (1984), 664.

[17] Id. , 668.

[18] Id. , 630.

[19] Compare Bentham (1948); Dan-Cohen (1984), 627 et seq.

[20] Id., 640.

[21] Dan-Cohen does not draw this conclusion, indeed he later discusses ignorance of law separately. Id., 645.

[22] Infra 87.

[23] Dan-Cohen (1984), 645 et seq.

[24] Id., 643, fn 45 cites Commonwealth v. Chermansky, 430 Pa. 170, 174, 242 A. 2d 237, 240 (1968). It is surprising to compare this case with Dadson. R. v. Dadson (1850) 4 Cox CC 358. See Williams, G. (1961) Criminal law: the general part. 2[nd] ed. Holmes Beach, Florida: Gaunt, 23 et seq.

[25] Wiener, A. I. (1995) Alkotmány és büntetőjog. (Constitution and criminal law) Állam- és Jogtudomány 1-2: 91., 177. Similarly in Austrian criminal law today there still are elements in the definition of some crimes, which do not have to be covered by the mens rea of the offender. Triffterer, O. (1994) Österreichisches Strafrecht, Allgemeiner Teil. 2nd ed. Wien, New York: Springer-Verlag., 191-197. The same can be said about German criminal law. Jescheck, H-H. (1978) Lehrbuch des Strafrechts, Allgemeiner Teil. 3[rd] ed. Berlin: Duncker & Humblot, 448-453.

[26] Article 168 Btk.

[27] MBK, 338-339.

[28] These rules must be distinguished from the Dadson principle, which concerns a similar scenario to the acting at one's peril rule. Dadson, however, introduced a mens rea element by holding that "a person making an arrest must know of, or at least suspect, the existence of valid grounds for an arrest" See Smith, J.C. & Hogan, B. (1998) Criminal law. 8[th] ed. London, Edinburgh, Dublin: Butterworths, 36-37; Smith, J.C. (1989) The Law Commission's criminal law bill: a good start for the criminal code. Statute Law Review 16: 105., 34-41.

[29] Smith & Hogan (1998), 36.

[30] Dan-Cohen (1984), 662 et seq.

[31] Id.

[32] Jescheck, H-H.(1969) Lehrbuch des Strafrechts, Allgemeiner Teil. Berlin: Duncker & Humblot, 297-299; Triffterer (1994), 270-271.

[33] 2 L.R.-Cr. Cas. Res. 154 (1875) as cited by Dan-Cohen. The case involves a statutory rape.

[34] Id., 174-75.

[35] See Ashworth, A. (1995a) Principles of criminal law. 2[nd] ed. Oxford: Clarendon Press; New York: Oxford University Press, 158-167. Stuart uses the term 'absolute liability', where no fault, merely proof of an act is required. Stuart, D. (1995) Canadian criminal law: a treatise. 3[rd] ed. Scarborough, Ontario: Carswell, 173-181.

[36] Dan-Cohen (1984), 643.

[37] In such a case the conduct rule would simply forbid citizens to use deadly force against suspected criminals, but the decision rule would allow a qualified defence predicated on the actual 'success' of the use of force. Id., 644.

[38] Fletcher (1978), 755-58. Fletcher's account on mistake of law accords with Dan-Cohen's analysis of ignorance of law as a defence. Dan-Cohen (1984), 646 et seq. For a critical assessment of Fletcher's views see Smith, A. T. H. (1982b) The idea of criminal deception. Criminal Law Review, 721.

[39] The claim that legality places requirements on mens rea will not be further substantiated in this thesis, because that would greatly exceed the limits of the work. It is sufficient to observe that, as far as English law is concerned, Allan suggests, on the basis of Sweet v. Parsley (1970) AC 132, 152 (Lord Morris), that mens rea is in all ordinary cases an essential ingredient of guilt of a criminal offence, which is reflected in the legislative context in the presumption that the court "must read in words appropriate to require mens rea" Id., 148 (Lord Reid). See Allan T. R. S. (1993) Law, liberty, and justice: the legal foundations of British constitutionalism. Oxford: Clarendon Press; New York: Oxford University Press, 39. Similarly in German law, the principle - "no punishment without culpability" - as far as criminal law is concerned, is rooted in the constitutionally protected right to human dignity and self-responsibility. NJW (1997) 929, 932. In Austrian law whilst the extent of the constitutional protection awarded to the culpability principle is disputed, it is still generally accepted that it is part of the rule of law principle. Lewisch (1993), 156-278.

[40] For a somewhat dated but fundamental discussion of the vagueness doctrine see Amsterdam's note. Amsterdam (1960) The void-for-vagueness doctrine in the Supreme Court. University of Pennsylvania Law Review 109: 67. Waldron presents a philosophical approach (Waldron, J. (1994), Vagueness in law and language: some philosophical issues. California Law Review 82: 509), whilst Post an economic analysis of the doctrine (Post, R.C. (1994) Reconceptualizing vagueness: legal rules and social orders. California Law Review 82: 491). Further consider Tribe, L. H. (1988) American Constitutional Law. 2[nd] ed. Mineola, New York: The Foundation Press, 1033 et seq.

[41] It is generally accepted that there are two rationales for the void-for-vagueness doctrine. Dan-Cohen identifies them as follows: a) fair warning rationale; b) the other is what he calls the 'power control' rational, which concerns the guiding and controlling judicial decisions [Dan-Cohen (1984), 658]. Jeffries arrives at a similar conclusion [Jeffries (1985), 196-7], and Post observes also that "the doctrine underwrites the clarity of the law's distinction between acceptable and forbidden behaviour, so as both to guide the actions of citizens and to restrict the discretion of government officials" [Post (1994), 491]. The focus on the 'power control' rationale is not only apparent from Justice O'Connor's statement in Kolender v. Lawson. Already in Papachristou v. City of Jacksonville, 105 U.S. 156 (1972), the Supreme Court invalidated an anti-vagrancy ordinance of the city of Jacksonville in Florida. The Court based its decision on the void-for-vagueness doctrine (Id., 162) characterising the ordinance as a vehicle for 'whim' and 'unfettered discretion' (Id., 168) (quotation omitted).

[42] Jeffries (1985), 201-212;

[43] One of the famous expositions of the fair warning principles was the pronouncement of Justice Holmes in McBoyle v. United States, 283 U.S. 25 (1931) in which the relevant point involved interpreting interstate transportation of a stolen 'motor vehicle' to exclude an aeroplane: "Although it is not likely that a criminal will carefully consider the text of the law before he murders or steals, it is reasonable that a fair warning should be given to the world in language that the common world will understand, of what the law intends to do if a certain line is passed. To make the warning fair, as fair as possible the line should be clear." Id., 27. This expression has also been used by the Model Penal Code [MPC §§1.02. (2) (d)] and by Jeffries in his article [Jeffries (1985), 201, 205-212] and was similarly referred to by Ashworth [Ashworth (1991) 419, 432; Ashworth (1995a), 73]. Note that Thomas describes notice as a purpose of criminal law. Thomas (1978), supra 4.

[44] United States v. Cardiff, 344 U.S. 174 (1952). Id., 176. Cited also by Jeffries (1985), 205.

[45] Lanzetta v. New Jersey, 306 U.S. 451 (1939). In this case the Supreme Court voided a statute, which made it criminal to be member of a gang.

[46] Id., 453.

[47] Connally v. General Constr. Co., 269 U.S. 385 (1926). This case involved a lawsuit to enjoin certain state and county officers of Oklahoma from enforcing provisions of an Oklahoma statute, which created an eight-hour day for state employees and set out a minimum wage. On the violation of these provisions a penalty was imposed including a fine and /or imprisonment. Id., 388.

[48] Id., 391.

[49] The doctrine has developed from the requirement of the Sixth Amendment, that the accused should know the nature of the accusation against him, and also from the general due process protection of the Fourteenth Amendment; it is now firmly rooted in the due process clauses of the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendment See for example Bjerregaard, B. (1996) Stalking and the First Amendment: a constitutional analysis of state stalking laws. Criminal Law Bulletin 32: 307, 311. In constitutional adjudication under what is known as the 'chilling effect' doctrine [Columbia Law Review (1969) (Note), 808] a higher standard of scrutiny is applied to statutes, the uncertainty of which may inhibit people from exercising constitutionally protected rights.

[50] As the MPC puts it, "to give fair warning of the nature of the sentences that may be imposed on conviction of an offence" MPC §§1.02. (2) (d).

[51] Kolender v. Lawson, 461 U.S. 352 (1983).

[52] Id., 357. (Citation in the original omitted).

[53] Dan-Cohen (1984), 659.

[54] Id.

[55] Screws v. United States, 325 U.S. 91, 96 (1945).

[56] See for example R. A. V. v. United States, 120 L. Ed. 2d 305 (1992) in which a group of teenagers burned a cross within the fenced portion of the yard of a black family living in a white neighbourhood. One of the perpetrators was prosecuted under a hate speech ordinance, which he later challenged. This was rejected by the Minnesota Supreme Court, which constructed the St. Paul ordinance in question in such a way that it became restricted to 'fighting words'. For more detail see Gellér, J. B. (1998a) Laws penalising bias speech and their constitutionality in the United States. Acta Juridica Hungarica 39: 25. Compare with Dan-Cohen (1984), 658.

[57] One method for the legislature, which has been utilised to mitigate any vagueness challenges and to provide law enforcement and judicial agents with an objective method of judging the defendant's behaviour is to impose a scienter element. Dan-Cohen (1984), 658, fn 28 quoting the appropriate state laws. Id. quoting the appropriate state laws. Specific intent elements in antistalking legislation usually require that the actus reus be intended to place the victim in fear of death or serious bodily injury. Bjerregaard (1996), 312. See also Dan-Cohen (1984), 659.

[58] Dan-Cohen (1984), 659-60.

[59] 423 U.S. 48 (1975).

[60] Id., 49.

[61] Dan-Cohen (1984), 660.

[62] Id.

[63] Id. Jeffries (1985), 205-211.

[64] Dan-Cohen (1984), 661.

[65] Id.

[66] Id.

[67] Id., 662.

[68] Id., 663.

[69] Id., 664.

[70] Id., 652.

[71] Id., 663.