Grace X. Yang[1]: World Internet Conference and China's Promotion of Cyber Sovereignty (ELTE Law, 2024/2., 109-126. o.)

https://doi.org/10.54148/ELTELJ.2024.2.109

Abstract

Despite ongoing criticism, the Chinese government has continuously hosted the World Internet Conference for the last decade. This research explores the motives behind China's persistent efforts, particularly focusing on its strategies for advocating cyber sovereignty. It uses natural language processing and discourse analysis to analyse official documents and Chinese media reports about the World Internet Conference. It finds that China uses discourses aligned with the ideologies of Non-aligned Movement members to facilitate the promotion of cyber sovereignty and leverage the World Internet Conference to build partnerships to influence the development of global cyber governance.

Keywords: World Internet Conference; cyber sovereignty; China; Non-alignment Movement; Natural Language Processing

I. Introduction

The World Internet Conference (WIC) is a worldwide annual Internet event jointly hosted in Wuzhen by the Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC) and the Zhejiang Government. It is currently the largest and highest-level Internet Conference in China and one of the largest Internet events in the world. Unlike the multi-stakeholder Internet forum the Internet Governance Forum (IGF), which is accessible to stakeholders around the globe, the WIC is invitation-only; only a few hand-picked businesses and officials are invited.

It has been evident since its inception that WIC is not a simple technical conference but that it has obvious political and diplomatic overtones since each year, top-level Chinese Communist Party (CPC) officials attend, and Chinese President Xi Jinping delivers an opening remark through a letter, video or personal presence. However, it has been de facto

- 109/110 -

boycotted by major Western countries, especially the United States (US) and criticised as 'a propaganda effort' aimed at promoting the Chinese multilateral model of Internet governance.[1] Yet it has consistently been held for the last decade, since 2014. Why does China insist on hosting the event, and what message is China trying to convey through it?

II. Literature Review

Unlike almost all other countries, since it was connected to the World Wide Web in the early 1990s, the Chinese government has controlled all online access routes. The Great Firewall (the Golden Shield Project) was built shortly after this,[2] and national sovereignty has 'naturally' been extended to cyberspace. As stated in the widely cited White Paper on the Internet in China issued by the Information Office of the State Council of China in 2010, the Internet has been regarded as a component of China's infrastructure. Further, the Internet within Chinese borders comes under PRC sovereignty and jurisdiction, and the state plays the leading role in its administration.[3]

In the context of the Arab Spring and visions of what may occur when the Internet is not under state control, China proposed a code of conduct for state behaviour that aims to identify the rights and responsibilities of states in relation to cyber governance at the UN General Assembly together with Russia and other Shanghai Cooperation Organization members in 2011 and 2015. The proposals called for a re-evaluation of the then cyber governance model and emphasised the key role of states in managing domestic cyber affairs. Sovereignty was proposed as the first principle of cooperation in cyberspace at the Budapest Conference on Cyberspace in 2012 by the Chinese delegation, entitling every state to 'formulate its policies and laws in light of its history, traditions, culture, language and customs'.[4]

Edward Snowden's revelations about the US National Security Agency's global espionage campaigns in 2013 stimulated the proliferation of Chinese academic literature on Internet sovereignty, with a focus on how to defend the cyber border. In 2014, the first WIC in Wuzhen was held, and Chinese President Xi Jinping put forward the term

- 110/111 -

'Internet sovereignty' publicly for the first time. At the second WIC, he further claimed that 'we should... respect Internet sovereignty... respect the right of individual countries to independently choose their path of cyber development and model of cyber regulation and participate in international cyberspace governance on an equal footing.'[5]

Since then, the idea of 'Internet sovereignty' has been mentioned frequently by the top leaders of the CCP, including the former Internet 'Czar' Luwei and has been included in discourses and policies by Chinese officials, media and scholars. It has been considered a milestone for China in terms of the definition of norms in the field of global Internet governance. Fang Binxing, the so-called 'Father of China's Great Fire Wall', emphasised the 'man-made' nature of cyberspace, the instrumental aspect of data and the need for the equal participation of sovereign countries in global cyberspace governance in his book Cyberspace Sovereignty: Reflections on Building a Community of Common Future in Cyberspace in 2019. Four versions of the White Paper, Sovereignty in Cyberspace: Theories and Practices were unveiled at the World Internet Conference since 2019, which define the concept, fundamental principles and related practices, thus may be taken as the latest effort of the Chinese government to formulate the respective norms.

China advocates a state-centred and bordered Internet, which is based on territorial sovereignty, focusing on individual responsibilities, maximising economic benefits and minimising political risks for the sake of the one-party rule,[6] while the US and other major Western countries advocate an individual-based, rights-centred, market-driven, single and connected Internet. This became especially relevant when, in 2011, China overtook the US as the global leader in terms of the installation of telecommunication bandwidth. By 2014, its bandwidth was double that of the US.[7] Contestation in the global cyber governance arena between China and the West, especially the US, has been deeply rooted since the beginning of the Internet epoch.

However, due to the Chinese policy formulation process, Zeng and others find - by unpacking the Chinese discourse about 'Internet sovereignty' by analysing Chinese-language literature - that the disagreements and uncertainty within China over its meaning and measures for putting it into practice are huge.[8] For example, there is unresolved

- 111/112 -

discussion about the relative merits of the terms 'information sovereignty', 'Internet sovereignty', and 'cyber sovereignty', the scope of which concepts are broadening; there are also disagreements about the origins of the term (whether it derives from China alone, or it has other origins, such as the NATO-sponsored Tallinn Manual); there are also debates around the concept of 'network frontiers', ie how to define the limit of the application of sovereignty. Although China has a great interest in promoting China's normative position in global cyber governance, the fragmented and underdeveloped domestic formulation of the discourse has restricted the process.

Roger Creemers argues that China's notion of 'cyber sovereignty' involves three normative dimensions that starkly contrast with traditional cyber governance. First, the idea that national governments possess sovereign rights to regulate all online activities within their borders directly conflicts with the global connectivity and openness of the Internet. Second, the assertion of national sovereignty over non-state actors contradicts the multi-stakeholder model promoted by Western countries. Third, the principle that all sovereign states are equal poses a direct challenge to the longstanding dominance of the US in cyberspace.[9]

According to Sarah McKune and Shazeda Ahmed, China's understanding of 'Internet sovereignty' has three dimensions: 'Internet governance', 'national defence', and 'internal influence.'[10] Segal argues that Xi's cyber diplomacy has three major aims. The first is to limit the threat posed by the Internet and the flow of information to the domestic stability and legitimacy of the regime; the second is to extend China's influence in the military, political and economic spheres; the third is to counter the US's advantage and increase China's room for manoeuvre. China is pursuing a 'parallel track' of managing state-to-state relations while trying to generate international norms which could improve its domestic control of the flow of information.[11]

Andrew Devine posits that China assumes four distinct roles within the WIC: developer, global leader, global village member and law-abiding citizen. According to Devine, China strategically adopts these roles to persuade developing and emerging countries to embrace its preferred governance model, cyber sovereignty. The countries targeted are those where China wields economic influence as a developer or political influence as a global leader, particularly in areas where the US has scaled back its involvement in foreign affairs.[12]

- 112/113 -

States that support the concept of cyber sovereignty often do so thinking that the status quo favours a US-favoured, techno-imperialist regime at odds with democratic decisionmaking, which 'allows the US to enforce rather easily its domestic policies, at times with extraterritorial effects'.[13] Therefore, the phenomenon of cyber sovereignty may serve to establish cyber territoriality within a country's borders and diminish the hegemonic power of the Western-led liberal order.

Mueller argues that China is trying to incentivise other developing countries to internalise and adapt its model of realigning control of communication with the jurisdictional boundaries of national states through the WIC.[14] McKune and Ahmed argue that the World Internet Conference's fundamental goal is to combine forces with developing countries to gain international respect for the idea of Internet sovereignty and authoritarian digital practices.[15] Karmazin points out that China is organising this conference to promote its views globally and mobilise potential allies.[16]

III. Theory and Hypothesis

The paper's entry point is the idea of a 'norm', which is mainly adopted from the theory of social constructivism. Unlike neo-realism, which focuses on material capabilities and the distribution of power, social constructivism emphasises the role of ideas, identities and social practices. The identities and interests of states are not given but formed through social interaction.[17] The mutual constitution of social structure and agency is the foundation of social constructivism, with norms serving as the link between these two elements. Social constructivism stresses that ideas and communicative processes primarily determine which material factors are deemed relevant and shape the understanding of interests, preferences and political decisions.[18]

- 113/114 -

According to Fennimore and Sikkink, there are three stages in the 'life cycle' of a norm.[19] The first stage is called 'norm emergence', a process of persuasion by 'norm entrepreneurs'; the second is called the 'norm cascade', involving norm acceptance, which is characterised by imitation of the norm by followers of the norm entrepreneurs; the third is the internalisation of a norm, referring to when norms have acquired a taken-for-granted quality and are no longer a topic of public debate. There is a 'tipping point' after the second stage when the norm has been adopted by a critical proportion of relevant state actors. Many norms do not reach this tipping point, so the completion of the life cycle is not inevitable.

For the emergence of a norm, the existence of a norm entrepreneur and 'organisational platforms' are essential.[20] Norm entrepreneurs use language to name, interpret and dramatise norms in a usually contested environment where alternative norms exist. Norm diffusion occurs through social interaction, and norms which are aligned with the target audience's existing beliefs and practices may facilitate diffusion. Organisational platforms at an international level are used by norm entrepreneurs to promote their norms. The norms must be institutionalised in some international rules or organisations for them to reach the second stage. After the tipping point, more countries may adopt the norms without domestic pressure to change. After internalising specific norms, the state's identities and interests may conform accordingly.

Based on this theory, the author formulates the following hypothesis: China tries to promote cyber sovereignty through WIC with discourses acceptable to the targeted audiences and leverages the WIC to build strategic partnerships and alliances to promote cyber sovereignty, particularly with countries sceptical of the Western model.

IV. Data and Methodology

The primary data sources for this research are the official documents associated with the World Internet Conference (some manually translated from Chinese to English), and Chinese news media coverage retrieved from the database Lexisnexis Uni in the period from 1 January 2014 to 1 August 2023.

Among the overwhelming Chinese media coverage of WIC, China Daily appears to be the media outlet that has covered this event most comprehensively and in-depth over the years. It is the leading English-language newspaper, telling Chinese stories to the world. It covers all continents globally, reaching a total readership of more than 350 million, and is the most quoted Chinese publication by foreign media.[21] China Daily has different editions

- 114/115 -

for different regions, including North and South America, Europe, the Asia-Pacific and Africa. The 'global edition' coverage was selected for this research because other editions generally repeat this version. Altogether, 906 reports mentioning WIC were collected during the period under analysis for this research.

Natural language processing (NLP) with Python was used to analyse official documents and media coverage. NLP is at the intersection of computer science and linguistics and began in the 1950s;[22] it is a method to extract meaningful information from large quantities of text data with the help of machine learning. In this research, frequent analysis is used to identify the most frequently occurring terms, sentiment analysis is used to evaluate the sentiment of the news reports, and temporal analysis is used to trace the frequency of words over time.

V. Finding and Discussions

The themes of the conferences over the last ten years - as shown in Table 1 - are quite consistent.

Table 1: Themes of World Internet Conferences (Source: Own editing)

| 2014 | An Interconnected World Shared and Governed by All - Building a Cyberspace Community of Shared Destiny |

| 2015 | An Interconnected World Shared and Governed by All - Building a Cyberspace Community of Shared Destiny |

| 2016 | Innovation-driven Internet Development for the Benefit of All - Building a Community of Common Future in Cyberspace |

| 2017 | Developing Digital Economy for Openness and Shared Benefits |

| 2018 | Creating a Digital World of Mutual Trust and Collective Governance |

| 2019 | Intelligent Interconnection for Openness and Cooperation - Building a Community with a Shared Future in Cyberspace |

| 2020 | Digital Empowerment for a Better Future: Building a Community with a Shared Future in Cyberspace |

| 2021 | Towards a New Era of Digital Civilization - Building a Community with a Shared Future in Cyberspace |

| 2022 | Building a Networked World Together to Create a Digital Future - to Jointly Build a Shared Community in Cyberspace |

| 2023 | Creating an Inclusive and Resilient Digital World Benefitting to All |

- 115/116 -

The meaning of this recurring theme is hard to comprehend at first glance, but like many other Chinese foreign policy concepts, it starts as more of a slogan at the beginning and is gradually discussed and defined in Chinese official discourse.[23] In this context, the meaning of 'Building a Community of Shared Future for Mankind in Cyberspace' was defined as the 'Four Principles' (respect for cyber sovereignty, maintenance of peace and security, promotion of openness and cooperation, cultivation of good order) and the 'Five Proposals' (speed up the building of global Internet infrastructure and promote inter-connectivity; build an online platform for cultural exchange and mutual learning; promote the innovative development of a cyber economy for common prosperity; maintain cyber security and promote orderly development; build an Internet governance system to promote equity and justice) by the Chinese President Xi Jinping in his opening remark at the second WIC.[24] These have been abbreviated as the 'Four Principles' and 'Five Proposals' since then.

The Four Principles are believed to be intentionally used to invoke China's 'Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence' (respect of sovereignty and territorial integrity, nonaggression, nonintervention, equality and mutual benefits, and peaceful coexistence),[25] which were proposed by China when it tried to establish diplomatic relations with neighbouring countries like India and Burma in the 1950s after the establishment of the new country. The five principles were later developed further by the Asian-African Conference (the 'Bandung Conference') convened in Bandung in Indonesia in 1955 into ten principles (the 'Bandung Spirit') to deal with international relations, including respect for the principles of the Charter of the United Nations, respect for sovereignty and integrity, the equality of all races and all nations, non-interference, the right of self-defence, non-aggression, the peaceful settlement of international disputes, mutual interests and cooperation. The Bandung Conference was the starting point for the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM). The concept of nonalignment emerged from the wave of decolonisation after WWII, especially after the Cold War began and when newly independent countries called on each other not to ally with either of the two superpowers but to join forces to support each other's national self-determination against all forms of colonialism and imperialism. The initial leaders of the NAM were India, Indonesia, Yugoslavia, Egypt, Ghana, etc., and there are now 120 member states.[26] Even now, it is still characterised by its vocal opposition to the 'sins of the West'.[27]

- 116/117 -

The Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence have been used to spur cooperation among non-Western countries while portraying China as a leader of these countries. Xi framed cyber sovereignty using a similar discourse in a speech from 2015:

The principle of sovereign equality enshrined in the Charter of the United Nations is one of the basic norms in contemporary international relations. It covers all aspects of state-to-state relations, including cyberspace. We should respect the right of individual countries to independently choose their own path of cyber development, model of cyber regulation and Internet public policies, and participate in international cyberspace governance on an equal footing. No country should pursue cyber hegemony, interfere in other countries' internal affairs or engage in, connive at or support cyber activities that undermine other countries' national security.[28]

Since the first conference, a forum called 'International Rules of Cyberspace: Practice and Exploration' has been dedicated to discussing the rule-making of global cyber governance. Guests and keynote speakers are targeted and invited. The three versions of the White Paper on Sovereignty in Cyberspace: Theory and Practice are the results of these discussions. In the first edition of the White Paper in 2019, cyberspace sovereignty was defined as 'the extension of national sovereignty to cyberspace... regarding cyber entities, behavior, infrastructure, information and governance in its territory'.[29] The second edition added an obligation dimension, which includes non-infringement on other countries' interests, non-interference in other countries' internal affairs, due diligence and protection.[30] The 'international law attributes of cyber sovereignty' were added to the third edition. This states that different countries may have different definitions and understandings of the concept of cyber sovereignty, but this does not affect the legal status of cyber sovereignty as an independent principle and rule. From the development process, we can see a clear tendency to define cyber sovereignty as a legal principle with the potential for universal application rather than as a political slogan in Chinese official documents.

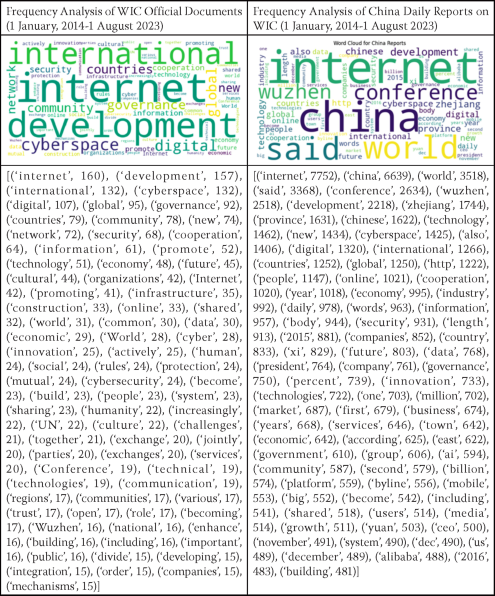

What is the main agenda in the WIC's official documents, and how is WIC framed in Chinese media reportage? Frequency analysis of the official documents of the WIC and Chinese media reportage reveals that the top 80 words are the following:

- 117/118 -

Table 2: Frequency Analysis of WIC Official Documents and China Daily Reports on WIC (Source: Own editing)

In the official documents of the WIC, words like 'countries', 'international', 'UN', 'cooperation', 'world' and 'governance' all related to the state, implying international

- 118/119 -

cooperation and collaboration among different countries, possibly under the auspices of United Nations, are associated with the advocacy of cyber sovereignty and multilateral model of cyber governance.

We identified that some aspects of the Internet are highlighted in the keywords: cybersecurity is underscored by keywords such as 'security', 'protection', 'cybersecurity'; the economic implications and technological development of the Internet are highlighted by 'economy', 'economic', 'innovation', 'companies', 'digital', 'technology'; the physical and technical infrastructure of the Internet is highlighted by 'infrastructure', 'construction', 'build', 'building'; and the social and cultural dimensions of Internet development are underscored by such words as 'community', 'cultural', 'human', 'social', 'humanity' and 'culture'. Meanwhile, 'challenges', 'future', and 'increasingly' are strongly forward-looking words, and 'governance', 'rules', 'exchange' and 'sharing' indicate a state of dissatisfaction with the status quo, pointing to discussions about changes in global cyber governance rules.

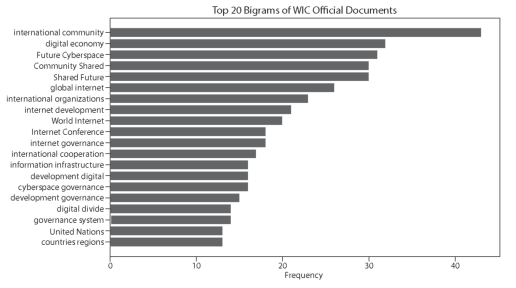

To get a better idea of the topics in the official documents, N-gram analyses were conducted, and the top 20 bigrams and trigrams are shown above. Multilateral model advocacy may be seen from keywords such as 'international cooperation', 'United Nations', 'countries regions', 'international governance cyberspace' and 'governments international organizations'. The words 'internet development', 'information infrastructure', 'development digital', 'development governance', 'development digital economy' and 'internet development governance' show a strong development orientation. In contrast, 'shared community' is a recurring theme that shows that advocacy is aimed at developing countries.

- 119/120 -

Figure 1: Top 20 Bigrams and Trigrams of WIC Official Documents (Source: Own editing)

From the frequency of words, we can observe the significant themes in Chinese media:

1. A focus on global and international perspectives: Words like 'world', 'international', 'countries' and 'global' indicate that the Chinese media portrays the conference as a global event; 'cooperation' also stands out, highlighting China's intention to collaborate internationally in the digital space; 'Governance' and 'security' suggest discussions around the rules, regulations and security in cyberspace.

2. A focus on technological and economic developments: Words like 'internet', 'technology', 'digital', 'cyberspace', 'data' and 'AI' indicate a strong focus on the conference's technological aspects; the frequent occurrence of 'innovation', 'development', 'economy', 'industry', 'market', 'business' and 'growth' suggests an emphasis on progress and advancements, pointing to the economic importance of digital technologies.

3. Stress on the importance of location: 'Wuzhen' and 'Zhejiang.' Wuzhen is a small town close to Alibaba's headquarters. This e-commerce platform has created enormous opportunities for ordinary people across China to create their own businesses at little cost. Compared to the more elitist and costly 'Silicon Valley' model, Wuzhen is more attractive to developing countries in terms of bridging the digital divide and progressing in digital development.[31]

- 120/121 -

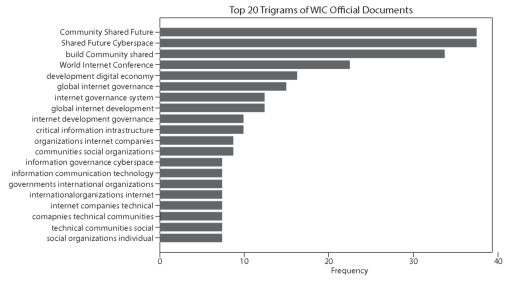

To obtain a better understanding of the value orientation of the Chinese reports, further analysis of the 'special words' which clearly demonstrate value orientations was conducted on the China Daily reports, and the result is as follows: ('sovereignty': 179, 'multilateralism': 16, 'multistakeholder': 0, 'censorship': 3, 'freedom': 67, 'right': 140, 'human right': 0, 'state': 228, 'government': 610, 'control': 123, 'democracy': 15, 'territory': 8, 'technology': 1462, 'security': 931)

The high frequency of 'sovereignty' (179) and 'government' (610) indicate a strong emphasis on national sovereignty in the context of the Internet, aligning with China's stance on cyberspace sovereignty; China's focus on 'multilateralism' (16) aligns with its preference for state-led Internet governance, while the absence of 'multistakeholder' (0) reflects no interest in involving multiple stakeholders; the high frequency of 'technology' (1462) and 'security' (931)underscores the focus on technological advancement and cybersecurity in the narrative; the low frequency of 'freedom' (67), 'democracy' (15), and 'censorship' (3) indicates limited discussion or avoidance of the topics.

Based on the above discussion, one may wonder who is actually invited to these conferences and who the 'community' China is trying to address is. Due to China's emphasis on the role of states and governments in cyber governance, we focus on governmental representatives only in this research. While the complete participant lists of the conferences over ten years have not been published, we have obtained lists based on the official websites and media reports, although these are not exhaustive.

We find the consistent participation in WIC of the following governments/countries: Afghanistan, Algeria, Argentina, Azerbaijan, Bangladesh, Barbados, Bahrain, Belarus, Burundi, Cambodia, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Cuba, Congo (DRC), Egypt, Equatorial Guinea, Ethiopia, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Iran, Iraq, Jordan, Kazakhstan, Kenya, Kiribati, Kyrgyzstan, Laos, Lebanon, Lesotho, Malawi, Malaysia, Maldives, Mauritius, Mexico, Micronesia, Montenegro, Myanmar, Namibia, Nauru, Nepal, Niger, Nigeria, Pakistan, Palestine, Rwanda, Russia, Samoa, Saudi Arabia, Singapore, Somalia, South Korea, Sri Lanka, Sudan, Switzerland, Syria, Tajikistan, Tanzania, Thailand, Turkmenistan, Tuvalu, Uganda, Uzbekistan, Yemen, Zambia, Zimbabwe, etc.

- 121/122 -

Figure 2: Word Frequency Over Time in China Reports (Source: Own editing)

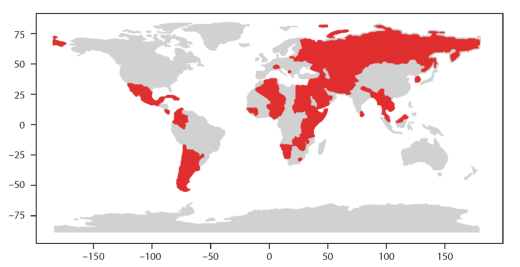

Figure 3: Regular Governmental Participants of the WIC (Source: Own editing)

- 122/123 -

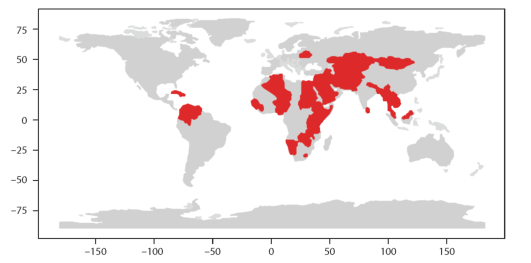

Most of them are also members of the NAM, which shares the ideology of the Bandung Spirit.

Figure 4: NAM Countries among Regular Governmental Participants of the WIC (Source: Own editing)

- 123/124 -

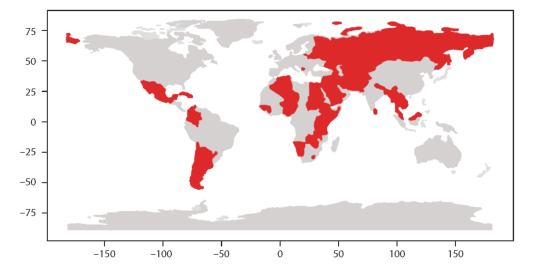

Most participating governments are also engaged in China's Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), of which 23 countries are classified as Least Developing Countries, and most are African. In 2021, China launched a 'China-Africa Initiative to Work Together to Build a Community with a Shared Future in Cyberspace' initiative at the China-Africa Internet Development and Cooperation Forum held via video link during the COVID-19 pandemic. In the said initiative, China advocated respect for cyber sovereignty as the premise for expanding Internet access and connectivity to African countries and advocated a leading role for the UN as the primary means of international cyberspace governance.[32]

Figure 5: BRI Countries among Regular Governmental Participants of the WIC (Source: Own editing)

Unsurprisingly, members of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation have been the most consistent participants throughout the whole decade, as they form a de facto alliance in promoting the norm of cyber sovereignty in international arenas like the UN General Assembly, and the leaders of those countries are often given the opportunity to make opening remarks at the World Internet Conference. In 2015, when Chinese President Xi Jinping attended the conference personally, he met with leaders of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization member states collectively. The Russian Prime Minister Medvedev remarked in his keynote speech that Russia had always advocated that all countries should have equal access to Internet management - as advocated by Xi - and that the work should be done

- 124/125 -

under the framework of the United Nations and based on the work of the International Telecommunication Union.[33]

China's persistent promotion of cyber sovereignty at the WIC over the last ten years, with discourses that align with those of the developing countries, especially those sceptical of the Western model, is influencing the rule-making associated with global cyber governance, leading to a more multilateral cyber governance landscape. The passing of UNGA Resolution 73/27 in 2018,[34] which established an 'Open Ended Working Group' to discuss the role of state government in global cyber governance, is a sign of this development. Among the 119 countries that voted in favour of the Resolution, 52 are frequent attendees of the World Internet Conference.

VI. Conclusion

Despite a de facto boycott by Western countries and ongoing criticism and ignorance, China has been hosting the World Internet Conference consistently for a decade. From a general examination of its official documents and Chinese media reportage from 2014 to 2023 that used a natural language processing approach, the research finds that China has been leveraging the WIC to build strategic partnerships and alliances to promote a cyber sovereignty agenda and a state-primacy model of Internet governance to shape a favourable global cyber order by strategically using discourses acceptable to and alignment with the targeted audience.

The research finds that the Chinese government is developing the term 'cyber sovereignty' into a universal legal principle rather than a mere political slogan, and Chinese official discourses at the WIC emphasise the importance of non-interference and sovereignty, the positive role of state and governments, the positive economic implications of technological developments, and have a strong developmental and forward-looking orientation. China has been intentionally defining cyber sovereignty in a way that aligns with the Bandung Spirit of the Non-Aligned Movement, whose main points include respect for the principles of the UN Charter, respect for sovereignty, non-interference and non-aggression, to promote the mobilisation of support. Most of the governmental participants of the conference are from developing countries, especially those engaged in the Belt and Road Initiative and the Non-alignment Movement.

- 125/126 -

China's advocacy of cyber sovereignty and a state-primacy Internet governance model through the World Internet Conference has by no means challenged a free and open Internet or contributed to the fragmentation of the Internet. The issue is particularly crucial for the developing world, which is at a critical point in determining its path to digitalisation and whose choices will significantly influence the future rule-making of global cyber governance. However, this research is limited to China's promotion strategies without examining the effectiveness of its influence and global reception, particularly those of the developing world. This gap should be addressed in future research. ■

NOTES

[1] Milton Mueller, 'Wuzhen Promotes the Chinese Internet Way (with a Little Help from Its Friends)' (30 November 2016) Internet Governance Project, <https://www.internetgovernance.org/2016/11/29/wuzhen-promotes-the-chinese-internet-way-with-a-little-help-from-its-friends/> accessed 15 October 2024.

[2] Gergely Gosztonyi, 'Special models of internet and content regulation in China and Russia' (2021) (2) ELTE Law Journal 92, DOI: https://doi.org/10.54148/ELTELJ.2021.2.87

[3] Information Office of the State Council of the People's Republic of China, 'The Internet in China' (2010) <https://nsarchive.gwu.edu/document/20842-03> accessed 15 October 2024.

[4] Huikang Huang, 'Statement by Huang Huikang, Director General of the Department of Treaty and Law of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, at the Budapest International Conference on Cyber Issues' Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People's Republic of China, 4 October 2012 <https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/web/wjb_673085/zzjg_673183/tyfls_674667/xwlb_674669/201210/t20121009_7669976.shtml> accessed 15 October 2024.

[5] Jinping Xi, 'Remarks by H.E. Xi Jinping President of the People's Republic of China At the Opening Ceremony of the Second World Internet Conference' Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People's Republic of China, 16 December 2015 <https://chinacopyrightandmedia.wordpress.com/2015/12/16/speech-at-the-2nd-world-internet-conference-opening-ceremony/> accessed 15 October 2024.

[6] Min Jiang, 'Authoritarian Informationalism: China's Approach to Internet Sovereignty' (2010) 30 (2) SAIS Review of International Affairs 73, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1353/sais.2010.0006

[7] David Robson, 'Why China's Internet Use Has Overtaken the West' (9 March 2017) BBC, <https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20170309-why-chinas-internet-reveals-where-were-headed-ourselves> accessed 15 October 2024.

[8] Jinghan Zeng, Tim Stevens, Yaru Chen, 'China's Solution to Global Cyber Governance: Unpacking the Domestic Discourse of "Internet Sovereignty"' (2017) 45 (3) Politics & Policy 432, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/polp.12202

[9] Rogier Creemers, 'China's Conception of Cyber Sovereignty: Rhetoric and Realization' in DWJ Broeders, van den. B. B. (eds), Governing cyberspace: Behavior, power and diplomacy (Rowman and Littlefield 2020, London) 114-115, DOI: https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3532421

[10] Sarah Mckune, Shazeda Ahmed, 'The Contestation and Shaping of Cyber Norms Through China's Internet Sovereignty Agenda' (2018) 12 International Journal of Communication 3835.

[11] Adam Segal, Chinese Cyber Diplomacy in a New Era of Uncertainty (2 June 2017) Hoover Institution <https://www.hoover.org/sites/default/files/research/docs/segal_chinese_cyber_diplomacy.pdf> accessed 15 October 2024.

[12] Andrew Devine, 'Contesting the Digital World Order' (2019) 42 Politikon 61, DOI: https://doi.org/10.22151/politikon.42.3

[13] Richard Hill, 'Chapter 4 Internet Governance: The Last Gasp of Colonialism, or Imperialism by Other Means?' in Roxana Radu, Jean-Marie Chenou, Rolf H Weber (eds), The Evolution of Global Internet Governance: Principles and Policies in the Making (Springer 2014, Cham) 86, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-45299-4_5

[14] Milton Mueller, Will the Internet Fragment? Sovereignty, Globalization and Cyberspace (Wiley 2017, New Jersey).

[15] Mckune, Ahmed (n 10) 3845.

[16] Aleš Karmazin, 'China's Promotion of Cyber Sovereignty Beyond the West' in Šárka Kolmašová, Ricardo Reboredo (eds), Norm Diffusion Beyond the West: Agents and Sources of Leverage (Springer 2023, Cham) 61, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-25009-5_4

[17] Alexander Wendt, 'Anarchy Is What States Make of It: The Social Construction of Power Politics' (1992) 46 (2) International Organization 394, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818300027764

[18] Martha Finnemore, Kathryn Sikkink, 'Taking Stock: The Constructivist Research Program in International Relations and Comparative Politics' (2001) 4 Annual Review of Political Science 393, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.polisci.4.1.391

[19] Martha Finnemore, Kathryn Sikkink, 'International Norm Dynamics and Political Change' (1998) 52 (4) International Organization 895, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1162/002081898550789

[20] Finnemore, Sikkink (n 19) 897.

[21] 'About China Daily Group' China Daily <https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/e/static_e/about#> accessed 15 October 2024.

[22] Prakash M Nadkarni, Lucila Ohno-Machado, Wendy W Chapman, 'Natural Language Processing: An Introduction' (2011) 18 (5) Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association 544, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1136/amiajnl-2011-000464

[23] Jinghan Zeng, Slogan Politics: Understanding Chinese Foreign Policy Concepts (Palgrave McMillan Singapore 2020, Singapore) 2.

[24] Xi (n 5).

[25] Karmazin (n 16) 64.

[26] André Munro, 'Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) - Definition, Mission, & Facts | Britannica' (21 June 2024) Encyclopedia Britannica <https://www.britannica.com/topic/Non-Aligned-Movement> accessed 15 October 2024.

[27] Andrew Cheatham, The New Nonaligned Movement Is Having a Moment (4 May 2023) United States Institute of Peace <https://www.usip.org/publications/2023/05/new-nonaligned-movement-having-moment> accessed 15 October 2024.

[28] Xi (n 5).

[29] China Institute of Contemporary International Relations, Shanghai Academy of Social Sciences and Wuhan University, 'Sovereignty in Cyberspace: Theory and Practice (Version 1.0)' (21 October 2019) <https://www.wicinternet.org/2019-10/21/c_815434.htm> accessed 15 October 2024.

[30] Wuhan University, China Institute of Contemporary International Relations and Shanghai Academy of Social Sciences, 'Sovereignty in Cyberspace: Theory and Practice (Version 2.0)' (26 November 2020) <https://www.widnternet.org/2020-11/26/c_808744.htm> accessed 15 October 2024.

[31] Anbin Shi, 'China's Role in Remapping Global Communication' in Daya Kishan Thussu, Hugo de Burgh, Anbin Shi (eds), China's Media Go Global (Routledge 2017, London) 46, DOI: https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315619668-3

[32] Cyberspace Administration of China, 'Cyberspace Administration of China Launches the Initiative on China-Africa Jointly Building a Community with a Shared Future in Cyberspace' (Office of the Central Cyberspace Affairs Commission, 25 August 2021) <https://www.cac.gov.cn/2021-08/25/c_1631480920680924.htm> accessed 15 October 2024.

[33] Official Weibo of the News Center of the World Internet Conference, 'In Addition to Xi Jinping's Speech at the Opening Ceremony of the World Internet Conference, Let's Take a Look at What the Guests from Various Countries Said (Shijie Hulianwang Dahui Kaimushi Chule Xi Jinping Yanjiang, Kankan Geguojia Bin Doushuo Le Sha)' (The Paper) <https://m.thepaper.cn/newsDetail_forward_1409778> accessed 15 October 2024.

[34] Developments in the field of information and telecommunications in the context of international security. Resolution adopted by the General Assembly on 5 December 2018. A/RES/73/27.

Lábjegyzetek:

[1] The author is PhD Candidate, Osteuropa Institut, Freie Universität Berlin. This paper was supported by the project 'PRIN 2022KTTSBC - Digital Sovereignty', funded by the Italian Ministry of Research and University. https://orcid.org/0009-0003-9275-4650.