Anja Amend-Traut[1]: The Aulic Council and Incorporated Companies. Efforts to Establish a Trading Company between the Hanseatic Cities and Spain* (Annales, 2012., 203-238. o.)

I. Introduction

The history of incorporated companies begins as early as in the 15[th] century, but their main characteristics emerge only upon the increasing demand for capital in the mining and oversees trade in the 16[th] century.[1] At this early stage, apart from the so-called Saiger companies[2] that were established in the South of Germany, the scene was for the most part dominated by the two large East India Companies in which Dutch and English merchants joined to form a risk-sharing community. Regardless of the manifold variations and the more or less pronounced sovereign involvement, which subsequent to these two models then led to a veritable wave of foundations in the course of the 17[th] century, the presently available research findings are based primarily on Scandinavian, French and later also Spanish and Portuguese enterprises. What is at best known in respect of the Holy Roman Empire is its territorial endeavours- such as the efforts to establish a trading company initiated by the Brandenburg Elector from the end of

- 203/204 -

the 17[th] century,[3] the activities of the Dukes of Courland[4] or the Abyssinian Project of Duke Ernst I. of Saxe-Gotha and Altenburg.[5] In contrast, for the Empire "it was not until the 18[th] century" that it had "endeavoured to found an overseas company".[6]

As revealed not least by the files of the Aulic Council now examined, there were, contrary to this traditional view (which is likely attributable to the endeavours initiated by the Mercantile Commission founded in Vienna in 1714 to participate in overseas trading via Trieste, or to the foundations of the Oriental Company and the East India Company in 1719 and 1722 [7]), also efforts at the level of the Empire starting from 1625 that were aimed at a participation in an overseas trading enterprise, namely a trading company between the Hanseatic Cities and Spain.[8]

The Aulic Council, one of the two Supreme Courts of the Holy Roman Empire of German Nation, had formed during the period between 1519 and 1564 at the Court in Vienna and also officially bore this name from the time the Rules of the Aulic Council were decreed in 1559.[9] Unlike the

- 204/205 -

Imperial Chamber Court, it was locally and organisationally dependent on the person of the Emperor, and like the Imperial Chamber Court was also a judiciary body, but also an imperial authority that performed governmental and administrative duties in the broadest sense.

As far as litigious proceedings are concerned, attention has already been drawn in general to the importance of the case files of both supreme courts for the history of trade and company law,[10] but for the issues being considered here have nonetheless been assessed only in isolated cases.[11] Thanks to the judicial files of the Imperial Aulic Council recently investigated by the research project of the Academy of Sciences Gottingen in collaboration

- 205/206 -

with the Austrian Academy of Sciences and the Austrian State Archives,[12] the focus of interest now increasingly turns, also with regard to the subject of investigation of interest here, towards those groups of files that emerged from the work of the Aulic Council as an administrative authority and from its function as a political instrument of the Emperor.[13] It was in these latter capacities that the body acted when the Emperor conferred privileges, such as privileges of business, manufacture, trade or printing,[14] when granting moratoria or promises of safe escort for merchants,[15] in some cases when answering and/or pursuing petitions and complaints of individual tradesmen, and lastly quite intensively when advising on and preparing negotiations with regard to questions of principle[16] as were also conducted in the causa examined here. Based on these records alone it is therefore not possible to add anything to the considerations of Konrad Reichards[17] and Franz Mareš[18] from the second half of the 19[th] century on the maritime policy of the Habsburgs and the previous statements made on the economic and political history as well as on the imperial history

- 206/207 -

of the scantly covered late Hanseatic period.[19] Although the relationship between the Hanseatic League and the Empire has often been taken up as a subject of research, such efforts for the most part largely overlooked the aspects of integration of the Hanseatic League into the structures of the Empire.[20] Moreover, based on the sources examined new statements can be made regarding the structure of early forms of incorporated companies as has already been called for in the past,[21] thus making it possible to further elucidate their history.

II. Incorporated companies - emergence and discourse

Amongst the "causes as to why [trade] is organised under a company and cannot be launched with many individually is not least the fact that a united force, in the event of need, is the most convenient way of offering resistance to the enemy. It will also be much harder for the enemy to encroach on such unified structure than on one that is divided. As a body, its members stand by one another more faithfully than in a case of separate accounts being held, since in the latter case each one seeks to maintain their own capital even if detrimental to the others. Because economic concerns begin at home. Moreover, the expenses incurred by this structure are then not so onerous and are also more easily borne by trade; and lastly it is a better means of increasing merchant trade as opposed to when one is divided, since in the latter case no one wants to do anything for

- 207/208 -

the other but instead envies, damages and obstructs the other." ("Zu den Ursachen/ warumb [der Handel] in eine Compagnei gebracht/ und nicht

bey vielen in particular mag angefangen werden; Darunter dann nicht die geringste/ daß eine vereinigte Macht/ im Fall der noth/ die bequemste ist dem Feind Wiederstand zuthun/ Es wird auch dem Feinde viel schwerer/ ein solches vereinigtes Werck anzutasten/ als wann man zertheilet ist/ Wann man auch ein Corpus ist/ stehet man einander getreulicher bey/ als wann unterschiedene Rechnungen seyn/ da ein jeder suchet/ sein eigenes Capital zu erhalten/ ob es gleich sey zu des andern Nachtheil/ Weil einem jeden das Hembd näher ist dan[n] der Rock. Es fallen auch die Unkosten/ die zu diesem Wercke gehören/ so schwer nicht/ und seind auch dem Handel desto leichter zu ertragen; und kürtzlich so ist es ein besser Mittel den Kauffhandel zu vermehren/ als wann man vertheilet ist/ da einer für den andern nichts thun will/ sondern vielmehr einer den andern beneidet/ schadet und hindert.")

It is these benefits, as expressed with these words taken from the agreement of the Australian or Süder=Compagny in the Kingdom of Sweden,[22] that impelled the individual merchants, associations of the latter and whole countries, from the beginning of the 17[th] century to the 18[th] century, to join together in groups which differed significantly from the trading companies that had been commonly known until that time and which today are referred to as privileged trading companies.[23]

Until the end of the 16[th] century economic activity was dominated, in addition to individual merchants, above all by partnerships which usually, with pronounced regional differences were operated in the form of a general partnership (offene Handelsgesellschaft), in some cases also as a

- 208/209 -

limited partnership (Kommanditgesellschaft).[24] It was then especially the overseas expansion and overseas trade that spurred the development of the incorporated companies, notably of the privileged colonial companies[25] - only later were they also founded for other purposes, for example in 1686 in France for maritime insurance, in Prussia in 1770 for exporting corn, or in 1750 in Austria for a sugar factory.[26] Unlike their forerunners, the newly emerging incorporated companies were in principle no longer consortium companies but were instead established to be permanent entities; organisationally it was no longer the individual person that came to the fore but that person's contribution instead, which could be transferred in the form of a stake or share; although the stakeholders or shareholders of the privileged companies participated in the company with their personal capital, but they were no longer themselves involved in trade and in outfitting the ships.[27] Above all, though, they were backed by sovereign guarantees, to a decisive extent through the grant of a monopoly. In addition, they were given various sovereign rights to implement their company purpose, such as policing or jurisdictional powers, as well as customs and staple rights. In their substance the articles of association of such companies were consequently a mix of provisions from both private law and - to use the modern-day terminology - public law.

Here it becomes clear that with such sovereign-backed enterprises overseas trade was not primarily spurred by merchants and traders but was above all intended to improve the balance of trade of whole countries; it was their welfare, not the welfare of individuals, that took precedence when it came to privileging the trading companies. This was put quite bluntly

- 209/210 -

in an imperial instruction prepared as part of the negotiations on the Spanish-German trading company, in which it is stated that "our income should be increased thereby".[28] Accordingly, the privileged companies were understood and lively debated by economists as an instrument of mercantilist economic policy.[29] Among their biggest critics is Adam Smith, who was vehemently opposed to the monopolistic status given to the companies.[30] Although various forms of monopolistic structures had been prohibited by the Cologne Recess of 1512,[31] humanists versed in legal matters, oriented on general well-being, already at the turn of the 16[th] century only regarded unseemly price arrangements, i.e. those "detrimental to the general good", as violations of the prohibition of monopolies.[32]

The intense debate at the level of economic theory is in contrast to the lack of interest in examining the companies from a legal perspective: in the absence of general statutory provisions for incorporated companies during the Ancien Régime, the privileges, which were normally granted to the trade companies in the form of so-called Octroi, Charter or Lettres Patentes,[33] constituted the legal sources of the companies par excellence. For them, just as for the individual merchants since Johann Marquard, the principle of specific law applied as a divergence from the ius commune.[34] In this regard, the privileges of the first established colonial companies, i.e. the English and Dutch East India Company of 1600 and 1602, the West India Company of 1621 or

- 210/211 -

the Hudson Bay Company of 1670, served as a model for the French and Brandenburg companies later founded.[35] Also regarding contemporary legal science, endeavours to define the incorporated companies in legal terms are largely absent. Particularly Marquard attributes the company to the universitas and this, citing a work published at the beginning of the 17[th] century, to the collegia[36] as their subtype, and thus subjects them to the regulations governing such institutions.[37] Moreover, the fairly limited number of relevant works concentrates on individual descriptions[38] or deals with specific problems in isolation.[39] The modern research works of the 19[th] and 20[th] centuries are primarily concerned with the search for the origins of contemporary stock corporations.[40] A summary description has recently been provided by the comprehensive work by Walter Bayer and Mathias Habersack[41] and Wilhelm Hartung and Ralf Mehr use various approaches in making a comparative analysis of entrepreneurial company law prior to 1800.[42]

- 211/212 -

III. The Spanish-German trading company - economic starting position

The files of the Aulic Council reveal a largely unknown facet in the history of the privileged maritime trading and colonial companies, namely the efforts of the Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire and the Spanish Crown to establish a trade treaty during the turmoil of the Thirty Years War.

Under economic aspects, Spain was of great interest for the Empire: the Spanish colonial empire around the year 1600 extended over large parts of South and Central America, the southern part of what today is the USA, and the Philippines.[43] It was only in the second half of the 17[th] century that Spain gradually lost its supremacy over the high seas to England and France, but despite that the Spanish fleet initially retained its important role as a link to the colonies. That is because in the general scheme of things this market was largely developed, since even as late as the first half of the same century "in Spanish America any traffic with foreigners without a special permit was prohibited on pain of death and confiscation; any foreign ship that showed up there was ... treated like a criminal".[44] Indeed, a system of escort convoys was introduced over the oceans and privileged export and import ports - including Havana in Cuba, Cartagena in Columbia, Veracruz and Acapulco in Mexico, and in particular Spanish Seville - were strongly secured. The reason for these protective measures was to ensure that the export goods could be transported safely from the colonies to Spain and/or East Asia. The chief goods exported from the Spanish colonies, apart from furs, tallow, sugar and cochineal (a scarlet-red dye which was used to produce the famous Vienna or Paris lacquer

- 212/213 -

and was extracted from cochineals), above all included silver from the Mexican and Peruvian mines.

Thanks to such favourable status of Seville, Spanish trade was largely in the hands of the merchants of Seville and was subject to the supervision of the Casa y Audiencia de Indias, (also referred to as Casa de la Contratación) based there and founded in 1503.[45] This was a royal authority that had been established to supervise and enforce the trading monopoly with the Spanish colonies. The Casa de la Contratación, for example for taxation of the colonial trade, recorded all vessel movements and freight, inspected incoming vessels, licensed captains, issued freight and shipping documents, and denied the colonies trade amongst themselves.[46] In short, the Casa - at least theoretically[47] - was a "bottleneck" "capable of identifying and recording every item and every person going to America or coming from America".[48] In addition, the officials working there exercised full civil jurisdiction and thus enforced Spanish trade law.[49] According to the then leading doctrine of the Bullionists,[50] the Castilian Crown was forced to do its utmost to keep precious metal within the country. For that reason it declared free trade as smuggling. Conversely, a policy of free trade, which would have opened all Spanish trading ports, would have caused the loss of nearly the entire trade with the Spanish colonies to the numerous and dynamic French, Dutch and English traders and the absence of State monopolies, which ultimately would have resulted in considerable losses for the Spanish monarchy.[51]

- 213/214 -

As far as the foreign trade situation of the Holy Roman Empire of German Nation was concerned, there were trade treaties with Great Britain and the United Netherlands, but these were fragile. As seen not least in other proceedings brought before the Supreme Courts of the Empire, there were frequently tensions that the Emperor was hardly able to resolve. For example, although the Emperor complied with the petition of the Hanseatic Cities to help them with the renewal of trade privileges that had been denied by Elisabeth I. in favour of some Hanseatic Cities[52] by expelling the Merchant Adventurers (English overseas merchants that over several centuries formed ever more closely knit ties and through trading privileges and contracts had been able to procure for themselves nearly the same position as the local continental Europeans),[53] this mandate was never enforced due to the divergent economic interests within the Empire.[54] And also the imperial order of 1600 to the United States of the Netherlands to withdraw announcements directed against the Hanseatic Cities and published within the Empire, in which trade with Spain and Portugal had been regulated and contravention was prohibited on pain of force, could not be enforced.[55] Here it becomes clear that, under Rudolph II., imperial policy was still extremely reserved when it came to taking external political risks at the insistence of individual subjects of the Empire, especially where their special economic interests were concerned.

By contrast, efforts within the Empire to promote trade were always attended by considerable success. For example, in a dispute between Hamburg and Magdeburg on the one hand and the Dukes Heinrich and Wilhelm the younger of Braunschweig-Lüneburg on the other, the Emperor succeeded in resolving the parties' differences by means of a compromise after setting up a commission "for amicable and legal trading".[56] Avowedly, the

- 214/215 -

negotiations were chiefly concerned with reaching a decision giving due regard to the "common good".[57] The case itself dealt with the freedom of the two Hanseatic cities to navigate on the Elbe which had been blocked by the Dukes in 1567/68 who had demanded that the traded goods be unloaded in Lüneburg and further transported by land.

The Emperor also met the request of Catholic merchants from Hamburg for an imperial protective warrant and an imperial intercession letter to extend authorisation to exercise the Catholic faith on the grounds that the authorisation of the Catholic faith, given the arrival of outside merchants, would "benefit general trading establishments".[58]

In the search for other, reliable overseas trading partners, Spain was attractive on account of its economic significance alone; with its imports from the colonies, it had coveted goods made even more valuable by the prohibition of free trade. Moreover, from the end of the 16[th] century Hanseatic merchants had already once before oriented their trade towards the Iberian Peninsula, after business activities with England had stalled as a result of the dispute with the Merchant Adventurers.[59] This shift had also already been prepared under imperial policy. Already Rudolph II., acting above all under the impression of the response of the English Queen Elisabeth I. to his mediation attempts in the disputes with the Merchant Adventurers, shifted his support to the Spanish side: by expelling them from the Empire he not only wanted to secure the freedom of trade of his own subjects but thereby ultimately also complied with the request of Spanish King Philipp II. for supplying goods.[60]

IV. Personal relations of the trading partners

It was thus also the good personal ties to the Spanish Court that were to facilitate the negotiations on the Spanish-German trading company.

- 215/216 -

Both regents endeavouring to establish a trading company, Emperor Ferdinand II. and Philipp IV. of Spain, were from the House of Habsburg.[61] To strengthen the alliance with Spain, the marriage between Ferdinand's son, who would later become Emperor Ferdinand III., with Philipp's sister, the Infanta Donna Maria of Spain, had been in preparation from 1624 and took place in 1631. Against this background it is not hard to explain why Ferdinand II. in 1628 made it known to the Hanseatic Diet by letter that, especially because of his close family ties to the King of Spain, an agreement in trade issues that would be mutually beneficial for the Hanseatic League and the Empire was possible.

V. Integration of the Hanseatic Cities

He thereby alluded to the plan to induce the Hanseatic Cities to join the planned trading company under the protection and the flag of the Empire. Ferdinand's objective was nothing less than obtaining freedom of navigation to Spain along with all colonies. This is exactly where the company's purpose lay, as was defined by the privilege of an exclusive trading partnership with Spain. To achieve this purpose, the awarding of numerous special rights was contemplated: the draft of the articles of association provided that Lübeck, Hamburg, Rostock, Wismar, Stralsund and Lüneburg were to become staple places of the trade with Spain for northern Germany. This would have meant that all goods that Spain needed from Sweden, Denmark, Holland, England or France could have been purchased only in these cities. Conversely, there would have been a requirement to ship all Spanish export items to these cities first before they could be further traded in the aforementioned countries. What is remarkable in this respect is that otherwise no new imperial awards of staple rights issued since 1500 have been found for which the Emperor was not at the same time also the local sovereign. In all other cases, the Emperor merely confirmed existing privileges.[62]

- 216/217 -

The question of customs sovereignty had also been considered; from a draft concept of an imperial instruction to two delegates it is clear that they were to prepare an expertise on possible customs and toll stations and the possible amount of the tariffs to be charged.[63] Moreover, those "opposing the new admiralty and company established in Spain" were to be prohibited from trading in Germany.[64] And not only that: vested with sovereign enforcement power, the members of the company were to be enabled to seize the goods of "rebels".[65]

The Emperor was to be the sole judge in all trade disputes in which the shareholders were involved.[66] As for the appellations, "a certain rule" could be prescribed "according to local custom". Ideally, these disputes were to be brought before the Aulic Council in Vienna; "in this way it would be easy to induce Your Majesty to expedite such appellation matters, or to have them expedited in pleno consilio Aulico, before all other matters; to commit panels of experts suited for that purpose, and other apprised of the matter, to such task; or in such countries to delegate such matters, on request, to impartial persons in such a way that they take a collegial decision on the Appellations Acta and the definite judgment ... interlocutorias, and afterwards deliver their vote cum deductione rationum eiusdem to Your Majesty to take a final decision, wherein Your Majesty would once again be most gracious in ordering that such matters be expedited in consilio before all others."[67] Accordingly, the Emperor was personally committed to a privileged judicature that provided for the appointment of experienced persons, swift preliminary judgment in terms

- 217/218 -

of expeditious preliminary decisions as in mandate proceedings, and an early final imperial decision, and was to expedite the proceedings. The vessels were to be maintained by the King of Spain, but sail "under our standard", i.e. under the imperial flag.[68] Lastly, both the King of Spain and the Emperor guaranteed their intention to personally ensure the protection of the trade of all Hanseatic Cities and their own.[69]

With these concessions the Emperor hoped to win over the Hanseatic League for his cause: After all, the Hanseatic Cities for some time had had to painfully experience the soaring economic development of the Netherlands which resulted in between 60% and 70% of total goods transhipment within the Baltic Sea region being controlled by the Netherlands in the 17[th] century - "the Baltic Sea had almost become a Dutch sea".[70]

Negotiations were then initiated with the Hanseatic Cities to implement the project.[71] Already in the past, they had time and again shown an interest in opening up new markets for themselves.[72] For quite some time, their trade had suffered considerable losses as a result of the already mentioned obstacles and impediments posed by Holland and England. At the meeting of the Aulic Council on 4 September 1627, which was attended by Emperor Ferdinand II., the instructions for the imperial chief negotiator, Count Georg Ludwig von Schwarzenberg,[73] were prepared. The Emperor's efforts to enlist the Hanseatic Cities for his cause then also coincided exactly with the loss of Hanseatic supremacy within the

- 218/219 -

Baltic Sea region. It was, the Emperor said, notorious that the Hanseatic Cities during the lifetime of King Rudolf II. and Mathias had been "hard pressed by various monopolies, had been denied freedom of shipping and navigation by foreign potentates, their vessels attacked [and] plundered". Since as a result of this "the commercial activities ... are falling into foreign hands", and the Hanseatic Cities were being deprived of their sources of revenue, and in some cases had even been "completely severed" from the Holy Roman Empire and were no longer able to express their opinions, the Emperor would spare no efforts so that the Hanseatic Cities could be restored to their former "prosperity". The Emperor would give them back "the freedom to navigate and trade" and in return only desired that they place themselves under his protection as their rightful Lord and Head and that they should enter into a company with the Spanish "Admiraldasco".[74] In return, the Emperor offered to grant the privileges and sovereign rights described.[75]

VI. War-related aspects

What interest did the Spaniards have in opening up their market? Already from the days of Philipp II. (1527-98), the country had been plagued by considerable financial woes. Already at that time the proposal had been made to declare state bankruptcy, largely caused by the lack of any industry as a result of which the country's economic needs had to be met with considerable financial expenditures from abroad. Smuggling and piracy that resulted in great losses, the depopulation of the heartland which entailed considerable losses in tax revenue, and particularly the devaluation of Spain's copper coins as a result of the situation that had gripped the whole of Europe from the 1620s, further contributed to the country's difficulties. With the foundation of the Dutch West Indian Company in 1621, the monopoly granted to it for trade in West Africa and America and the acts of war that it triggered, Spain's overseas trade was ultimately hugely weakened, thus resulting in entire Spanish fleets

- 219/220 -

being lost to the Dutch.[76] As a counter-measure, various associations were considered that were to be used in trade but also in war against Holland; it was hoped that "the Dutch would generally be deprived of their commerce, and thus their substance".[77] The objective was therefore not only to create new sources of cash but also to destroy Dutch trade.

Behind these economic aspects were also Spain's - ultimately fruitless - efforts to subjugate the seven northern Dutch provinces that had definitively renounced the Spanish monarch Philipp II. in 1581, but were still claimed by the Spanish Crown: the originally seventeen provinces of the Burgundian Netherlands had fallen to the House of Habsburg in 1477. Religious tensions were running high under Philipp II. after the Reformation, resulting in attempts to achieve centralisation that in 1568 culminated in the "Eighty Years' War". Already in 1579, the secessionist provinces joined together to form the Union of Utrecht and subsequently established the independent "Republic of the Seven United Provinces".[78]

As far as the Emperor's interests in this project were concerned, he hoped to gain additional advantages that were politically rather than economically motivated: vessels were urgently needed for the war with Denmark, and

- 220/221 -

these vessels were not available due to the Empire's hitherto lack of naval presence. As von Schwarzenberg poignantly put it in a letter to Wallenstein, the planned trading company was merely a "pretext for arming" for sea,[79] i.e. an excuse to take up arms.

The above statements reveal the warfare aspects relating to the colonial companies and their foundation stories. Particularly in the 17[th] century, in which the military conflicts in Europe also and particularly affected overseas trade, it was believed that political and military protection above and beyond peace treaties was needed, namely in the form of State guarantees. It was under this impression that Werner Sombart referred to the privileged trading companies as "half-warlike companies of conquest vested with sovereign rights and power resources of the State" and as "buccaneering campaigns turned into permanent organisations".[80] Indeed, the sources examined here show that the two regents were not solely concerned with economic upswing. Also inseparably bound up with that was the desire to take measures so as to be able to resist the much evoked competition, if necessary by resorting to acts of war. It was therefore no coincidence that a fleet of vessels made up of "battle and trading vessels" was planned as part of the outfitting of the contemplated company.[81] In addition, the plans provided among other things for a military occupation of East Frisian ports and other strategically significant points at the mouth of the Elbe so as to control Dutch trade and thus ultimately drive it out of North Sea/Baltic trade.[82]

VII. Balance of religious confessions

It is this war-related aspect pointing to additional considerations that served as the underlying motives, and were foremost in the minds, of those undertaking efforts at the Imperial Court during the Thirty Years War to

- 221/222 -

establish a Spanish-German trading company. To defend the Catholic religion, i.e. to preserve the balance in Europe "which was believed to be found in the balance of the two large religious groups",[83] Ferdinand II. already in January 1625 first sent an envoy to Munich in order to assure himself of Bavaria.[84] The correspondence that continued a few days later then reveals that it was contemplated "given the interest of religion on which these three princes are zealous . without any particular major risk . to maintain a new league and friendship with one another, and to do to the others the same as for oneself" and that new ways of doing this were devised.[85] These also included the contemplated trading company, since shortly thereafter negotiations on its establishment were being conducted at the Spanish Court in Brussels.[86] From there the Spanish Infanta let it be known that "to remedy and avert all intentions and plans . rising up . against the common Catholic existence from so many places . we shall and wish to do our utmost". This also included "seeking and negotiating an alliance with one another".[87]

VIII. Further findings from the files

In this regard the files of the Aulic Council in particular reveal that the initiative actually came from Spain, even though this is not that obvious from the widely read reports passed down from Franz Christoph Khevenhillers.[88] It is expressly stated in the files that "Mr. Gabriel de Roy, Royal Hispanic Council and authorised agent, . to Your Imperial Majesty proposed this means that in Germany, but in particular in the Hanseatic Cities, one or more societies preferably dedicated to Spanish Commerce

- 222/223 -

should be established and maintained".[89] On the other hand, the approach described here does not confirm the image of Ferdinand II., often said to have been indecisive when it came to forming his own opinions and to have been dependent on his advisers, as the "Emperor of the disastrous era in German history".[90] That is because it was common practice in the Aulic Council, after consulting jointly on all documents, to come to a consensual resolution on the further course to be taken. Overall, the Aulic Council had considerable influence over the Emperor's decisions given that its members were selected by the Emperor himself.[91] At any rate, Ferdinand's trusted adviser Hans Ulrich von Eggenberg shared his fascination for the project and underscores the reputation that followed therefrom: "When under Ferdinando 2[o] the Imperial standard will be seen on the high seas- as our ancestors remembered and can be found in books - and when we take precedence before others, this can preserve our voice amongst the nations what glory actually redounds to the Holy Empire and the German Nation?"[92]

IX. Essence of contemplated company

Now as far as the legal structure of the contemplated German-Spanish trading company is concerned, the files examined provide insight into a

- 223/224 -

corporate model which, admittedly, does not have any modern counterpart. Nonetheless, these and other variances are undoubtedly part of the early developmental history of stock corporations and thus of incorporated companies since it is precisely these variants that can be observed as their "historical alternatives".[93] Their different form was promoted by the already mentioned lack of codification of the privileged trading companies.

With regard to the relationship to sovereign power, the drafts show that no formal or separate act of establishment was planned for the project. Rather, the Spanish-German company was to be established simultaneously with the privileges being awarded. This approach was perfectly consistent with contemporary doctrine - which in this case, however, only partly followed Roman law.[94] According to that, the sovereign act of authorisation was the essential requirement for the existence of a universitas, but this could coincide with the grant of privileges. The same approach was taken for the two first privileged companies, i.e. the two East India Companies; in the royal charter of 1600 addressed to the adventurers of the East India Company, the grant of privileges and the establishment of the corporation were combined. And also the Octroi of the United East India Company of 1602 linked the establishment of the company to the grant of the privileges.[95]

The already mentioned privileges provided for in the draft were explicitly to be granted for the common benefit. In several passages it is emphasised that the contemplated company was to be established for "the benefit of the entire Holy Roman Empire".[96] Thus, the privileges would have been in perfect harmony with the admissibility of grants of privileges linked to the utilitas as had been taken from Roman law and defended by Marquard for commercial privileges in the 17[th] century.[97]

- 224/225 -

Strictly speaking, the deliberations in the Aulic Council were not aimed at establishing a completely new enterprise. In one passage the records passed down refer to the accession of the Hanseatic Cities to the "Spanish trading company" or to the "Almirantazgo".[98] What was thus meant by this was the German trading dependency[99] based in Seville which King Philipp IV. of Spain had established with privileges in the early 1620s and according to its statutes had subjected to the admiralty. Moreover, as German stakeholders, the Hanseatic League was to act as a cartellike association of ship owners and merchants which had also already long existed. Efforts were thus geared towards subjecting the existing association and the Spanish fleet to one common order. By contrast, there seemed to be a lack of agreement on the certainly not insignificant question of whether the future combined structure should sail under the flag of the German Emperor or that of the King of Spain. This approach, too, is consistent with the United East India Company since, under that company too, enterprises already existing were subjected to a common order, thus ultimately resulting in the creation of a "professional association".[100] It is no coincidence that this model is reminiscent of present-day chambers of trade and industry associations to which already in the past links were also traced to the trading companies.[101]

In the Aulic Council, a common order was seen as indispensable; only a company "thus founded and provided with such rules and statutes" fulfilled "the stated and contemplated purpose, namely the increase and improvement of trading business".[102] In terms of company capital, the plan was to require "firstly common, ample liquid funds" by "all

- 225/226 -

Hanseatic=imperial cities, and other subjects of the Empire, or tradesmen, so that trading would be all the stronger and also all the stronger continued, namely the goods from these and other countries would be exported all the more frequently to Spain, and also the Spanish, and Indian goods exported all the more frequently."[103] In order to promote investment in the company, the "Magistraty" should "properly inform predominant tradesmen in the cities on the project... , and ensure that they contribute towards equipping" the company. In order to set for private investors "a good example, and to motivate them all the more for a good work, it would be very good, namely in any case necessary, that the honourable cities, each according to their wealth, primarily ex communi Aerario, to furnish an acceptable sum of money and contribute it to the common company, so that the company at the very beginning should be all the better established."

The amount of the contributions made was to determine the proceeds to be paid out - "each proportionally" - and this "according to the trade revenues", i.e. according to the reported profit, "at the appropriate time". This applied both for "the cities, . and private persons", as far as this was "in the best interest of the company" and as long as the investor leaves "his capital therein".[104] For the contribution, a certain date was to be set, after expiry of which a participation was only still possible if it was in the interest of the company: "But in order for ... the company is established as soon as possible, and may be put to work, it will be necessary . to set and fix a certain date for all those who wish to join it, in which they shall contribute their quota, namely as much as each one wishes to invest in this general, or any subordinated individual company whereby it shall be communicated that after expiry of such date, . they would no longer enjoy . any advantage, . nonetheless the city, or the company hereafter, if it is useful or necessary for the company, can grant dispensation at any time, according to its reasonable discretion."[105]

Also the supervision of the company by expert persons was considered: "For cash auditing, including the accounting for all contributions, expenditures and trading activities, the cities shall have to appoint several

- 226/227 -

trustworthy, well-esteemed and capable persons who are also experienced in trading, to administer the same locally, where they shall be appointed, and to properly account for all income and expenditures, and in particular to report thereon." In this regard the members of the Aulic Council oriented themselves expressly on the organisational structures of already founded companies, as they "are all managed there in Holland and at other places."[106]

- 227/228 -

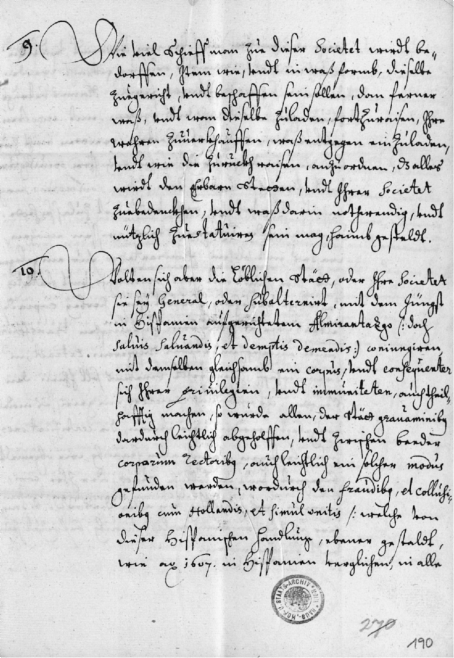

Excerpt from the considerations of the Aulic Council on the establishment of the company, HHStA, RHR, Antiqua, 30/1

- 228/229 -

As far as the company's organisational structure and the already existing legal obligations in the internal and external relationship were concerned, those in Vienna wanted to give the Hanseatic cities largely free reign and proposed either to establish the practices they were used to amongst themselves cumulatively to the new, own statutes of the company, or to recognise and to continue exclusively such practices: "Moreover, the honourable cities will be left to choose whether they, in order to promote the entire company, whether set up as a whole or divided into various subordinated entities, establish a particular Trade Jurisdiction - notwithstanding their existing direct jurisdiction and privileges - or act in any other manner as they wish to conduct the same, so that the parties involved in the company, and even the cities themselves by reason of the contribution they have furnished, and whatever other dispute possibly arising, do not get caught up in a drawn-out process but are entitled to summary proceedings as is anyway the law between tradesmen."[107]

Here, too, the inspiration presumably came from the United East India Company; already their common, binding and superior statutes did not have any influence on the individual legal connections in the internal and external relationship resulting from the company's activity - liability, participation and profit distribution: they were subject to the law already in force previously, i.e. to common and customary law.[108] As expressed in the source cited, this was quite expedient and reasonable; amongst merchants special procedural rules applied that were to continue in force and were not to be overridden by a validity claim of the general jurisdiction.

On the basis of such provisions relating to the internal organisation, modern literature on legal history tries to find answers to the question of what events and elements eventually gave rise to a separate legal personality of the privileged companies. In this regard, a rough distinction is made between two basic types, the so-called joint stock companies and the terminable stock or regulated companies.[109] In the former instance, the company acted already as a legal person by carrying on trade itself,

- 229/230 -

providing the necessary capital and paying out dividends. In the latter instance, however, trade continued to be in the hands of the members of the company who also contributed the capital. The company constituted its protectionist shield, serving solely to provide legal, military and diplomatic protection.

It would be pointless to try to allocate the planned German-Spanish Trading Company to one or the other group since it never got beyond the planning stage and as such could not prove itself in practice. At any rate, though, it may be said that trade itself was to continue to be in the hands of the Hanseatic merchants and that the capital was to be contributed by such merchants themselves and by the cities. Only maintaining the ships was to be the responsibility of the King of Spain who, according to the plans, was to act as an additional provider of funds in this regard. In this regard, the company was to provide its members with extensive support and assistance in the aforementioned sense. That said, initial steps towards consolidation into a separate legal personality of the contemplated company can also be found, as indicated by the intended use of supervisory bodies or where indirect mention is made that "the city, or the company",[110] themselves were granted the right to admit new members.

X. The negotiations with the Hanseatic League

The imperial cause as formulated in the instructions was put forward by the Vienna delegates at the assembly of the so-called Wendish Hanseatic Cities of Lübeck, Hamburg, Rostock, Wismar, Stralsund and Lüneburg which, in view of the general importance, scope and implications of the project, decided to convene a general Hanseatic Diet.[111] Information on the course thereof and the decisions taken is provided, in addition to the files of the Aulic Council, above all by the so-called Hanseatic recesses that were prepared for the Hanseatic Diets between 1356 and 1669.[112] At the start of

- 230/231 -

the Hanseatic Diet on 14 February 1628, the Emperor apologised initially by way of epistles that the rebellion in Bohemia and the Turkish Wars had prevented him from helping the Hanseatic Cities. Now that there had been a noticeable improvement in the situation, he wanted to devote his full attention to the needs of the Hanseatic League. He therefore invited them to conclude a trade treaty with Spain.[113]

It was henceforth not the Hanseatic Cities which, as members of the Empire, were asserting their right to support and assistance against foreign competition before the supreme courts of the Empire or the Emperor personally; but now it was the other way around: it was the leading instances of the Empire in Vienna that were now courting for the co-operation of the Hanseatic Cities. As two decades earlier, the trading obstacles put in the way of the Hanseatic League by England had been evoked, to a decisive extent by Lübeck, as a hindrance to the trade of all subjects of the Emperor and thus as a legal matter of the Empire as such,[114] it was now the Emperor and his supporters who emphasised in the negotiations that the economic fate of the Empire depended on the co-operation of the Hanseatic cities in the contemplated enterprise. Possibly it was even believed in Vienna that this request, in return for the mandate that was to ban the Merchant Adventurers from the Empire and that had been decreed at the insistence of the Hanseatic cities, could not be turned down. However, it is more likely that the Emperor's advisers already at a very early stage recognised that the project had no prospects of success. The imperial mandate against the English was in fact being undermined. The Emperor had not been in a position to give the successful support and assistance that would have provided the psychological basis for such strategic considerations. Further, the divergent interests amongst the Hanseatic Cities were an incalculable factor in the preparation of the negotiations with their representatives. In the 1620s, the often praised Hanseatic solidarity had at any rate become a matter of history. However, the consultations during the Hanseatic Diet and the events subsequent thereto nevertheless show that there had been

- 231/232 -

lively participation on the question of the planned trading company and that the decisions were backed by a considerable majority.[115]

A commission made up of delegates from the cities of Hamburg, Lübeck, Bremen and Danzig,[116] subsequent to the proposal submitted before the Hanseatic Diet, stated a number of demands including, for example, the exemption from export duties, the exemption from the inquisition tribunals and the appointment of a joint counsel to preserve their rights.[117] This approach was quite customary; in special matters certain cities were authorised to act for all,[118] and thus virtually served as a speaker for a representative of the entirety of the Hanseatic cities.

However, there was no willingness on the part of Spain to accommodate such demands. In a reply, the Hanseatic League stated that the cities could not find that the draft was "advisable for themselves".[119] This was certainly an expression of their disgruntlement about the Spanish position taken on the Hanseatic demands. Much more, however, the refusal was probably attributable to Spain's intention to make the Hanseatic League part of the Spanish Admiralty and to thus easily procure a fleet for itself: it was known that the King of Spain planned to proceed in this way in Brussels and Antwerp.[120] In additional notes and negotiations, the imperial delegates tried to emphasise the purely mercantile character of the agreement. They assured that the aims of the Spanish-German Trading Company were "nothing more than mercantile in character", and that the

- 232/233 -

Emperor certainly did not want "the Hanseatic League to meddle in the Dutch war".[121]

But in the end these promises could not convince the representatives of the Hanseatic League led by Lübeck. The expert opinions of city corporations obtained by the Lübeck council, such as the corporations of the maritime traders with Bergen, Riga, Nowgorod, Schonen, and even of the maritime traders with Spain were opposed to the planned trading company.[122] This confirms something that had already been known, namely that the interests represented before a Hanseatic Diet were defined by the council of a city.[123] The lawyer Lorenz Möller, among others, participated as the representative of Lübeck in the Hanseatic Diets of 1628 and 1630. He had acted in various positions in the Lübeck city council during the period of two decades and was known for his cautious politics during the 30 Years War, one of which was to enter into pacts and alliances only if these were indispensable.[124] Under Hanseatic diplomacy it was logically presumed that such an agreement would restrict the decision making scope between various potential trading partners from the North and Baltic Sea region. Also, the "good neighbourly correspondence", such as with Danzig and the Danish Crown, would be jeopardised by such a treaty, which is why it was preferred to stay neutral.[125] This would also to some extent allow foreigners to assume the management over their property, but they alone would have to bear any loss. The intended exclusive staple right for the transport of goods from and to Spain would draw the wrath of foreign governments on the Hanseatic cities. Overall, such a trade treaty would be tantamount to a restriction, not an expansion of trade. Here the mercantile endeavour to follow its own paths - which time and again had been demonstrated throughout the ages no matter what entrepreneurial activity was involved - was again revealed;[126] and even some two hundred years

- 233/234 -

later, Jonas Ludwig von Heß stated a corresponding rejection of monarchy and monopolistic company with the following words: "The merchant does not share his advantages in ill-calculated dividends with his princes or supreme trading authority".[127]

The attempt to expand, or perhaps even establish in the first place, an imperial power position in the north of the Empire and beyond its borders in the north of Europe had thus failed, since Ferdinand after all needed the experience and resources of the Hanseatic cities to establish a fleet. The latter, however, rejected the imperial courtship, a move which they certainly made to preserve their neutral and at the same time lucrative situation, but possibly also at least because of their religious differences to the imperial house and doubts about a pronounced imperial interest in the north.[128]

XI. End of efforts - conclusion

On 2 October 1629 the Hanseatic Diet was officially closed. As a result, "all the effort, work, diligence and costs incurred by his Imperial Majesty and the King of Spain for this useful transaction, ... came to naught"[129] and the "maritime projects of the Habsburgs were forever abandoned".[130]

In summary, the following can be stated:

1. The sources examined supplement the statements to date regarding the economic and political history of the Habsburgs - a naval presence was planned whose first step was to be the contemplated company.

- 234/235 -

2. The legal history of the late Hanseatic age, which before now has only been touched on, is rounded off as further insights in previously overlooked aspects of the Hanseatic League's integration into the imperial structures have come to light by revealing its dismissive stance towards the Emperor's endeavours.

3. Above all, the sources examined allow for the first time for statements with regard to the structure of the early form of incorporated companies from a first-hand legal source - in particular, the considerations of the members of the Aulic Council already indicate their development towards a separate legal personality. Consequently, the previous insights into those chapters of history which to a decisive extent are based on Dutch and English, and later also on Scandinavian, French, Spanish and Portuguese enterprises, have to be corrected. Some 150 years earlier than had been believed, it was the Habsburgs, namely the Emperor acting through the members of his Aulic Council, who through their foundation attempts made a decisive contribution (albeit only in theory) to the history of incorporated companies.

Summary - The Aulic Council and Incorporated Companies. Efforts to Establish a Trading Company between the Hanseatic Cities and Spain

The early chapters in the history of incorporated companies and thus the search for the first traces of an independent legal personality of trading associations would be incomplete without looking at the efforts undertaken in this regard by the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation.

- 235/236 -

For the first time since certain sources have been examined, a hypothesis can be made of the structure of the early forms of incorporated companies. Ideas formulated by members of the Aulic Council indicate efforts that incorporated companies made to obtain an independent legal personality. It is inevitable therefore to correct what historians have said of this phenomenon so far. Our information is mainly based on Dutch English and later Scandinavian, French, Spanish and Portuguese enterprises. Some 150 years earlier than what has been supposed up to now, the Habsburgs - more exactly, the emperor - acting via his court counsels - made an important - albeit theoretical - contribution to the history of incorporated companies by attempting to found some.

A glance at the first so-called privileged trading companies (privilegierte Handelscompanien) and their preferential status first of all illustrates that their spread was based more on interests of sovereign power than on commercial considerations. The body of legal instruments resorted to was not the common law of ius commune but the principle of specific law

(II) . The files of the Aulic Council, which also served as official political authority, provide an impressive picture of the timeless phenomenon of the correlation between economic and political interests: Spain and Germany shared more than just the desire to compensate for the loss of supremacy over the high seas or to find a reliable maritime partner in the first place

(III) and to cultivate their family relations (IV). The negotiations were concerned first and foremost with military co-operation (VI) intended to help return the secessionist Dutch provinces to the Spanish Crown and to restore or preserve the highly sensitive religious balance of Europe during the Thirty Years War (VIII). In this context, the draft of the planned trading cooperation as the actual foundation and key element of these diverse strategic considerations provides an insight into the legal structure of the early privileged trading companies, which on the one hand reveals some astounding parallels to the law of modern incorporated companies and on the other hand illustrates that such comparisons must not make us overlook archaic practices of trading associations (IX). The Emperor's courting for participation of the Hanseatic Cities in the project and their response ultimately show that the latter did not perceive themselves as members of the Empire in the sense of wanting to actively contribute to its economic and/or political well-being (V, X).

- 236/237 -

This information has helped us complement the late history of the Hanseatic Cities, which has been hardly analysed so far. The Hanseatic League had an uncooperative attitude to the emperor's endeavours, which sheds a new light on the process of its eventual integration into the imperial structure.

Resümee - Der Reichshofrat und die Kapitalgesellschaften. Bestrebungen zur Errichtung einer Handelsgesellschaft unter der Teilnahme der Hansestädte und Spaniens

Die frühe Geschichtsschreibung der Kapitalgesellschaften und damit die Suche nach ersten Spuren einer eigenen Rechtspersönlichkeit handelsmäßiger Zusammenschlüsse ist um die Bemühungen des Heiligen Römischen Reichs Deutscher Nation zu ergänzen. Die untersuchten Quellen lassen erstmals Aussagen über die Struktur der Frühform der Kapitalgesellschaften aus originär juristischer Hand zu - insbesondere deuten die Überlegungen der Reichshofräte bereits die Verdichtung zu einer eigenen Rechtspersönlichkeit an. Damit müssen die bisherigen ErkenntnissedieserGeschichtsschreibungkorrigiertwerden,diemaßgeblich auf niederländischen und englischen, später auch auf skandinavischen, französischen, spanischen und portugiesischen Unternehmungen beruhen. Rund 150 Jahre früher als bislang angenommen, waren es die Habsburger, namentlich der Kaiser durch seine Reichshofräte, die durch ihren Gründungsversuch maßgeblich, wenn auch nur theoretisch, zur Geschichte der Kapitalgesellschaften beigetragen haben.

Ein Blick über die ersten sog. privilegierten Handelscompanien und ihre bevorrechtigte Stellung verdeutlicht zunächst, dass weniger kaufmännische als mehr obrigkeitliche Interessen ursächlich für ihre Verbreitung waren. Als juristisches Instrumentarium griff man nicht auf das ius commune, sondern auf das Sonderrechtsprinzip zurück (II.). Die Akten des auch als politische

- 237/238 -

Behörde fungierenden Reichshofrats geben ein beeindruckendes Bild über das zeitlose Phänomen der Verknüpfung wirtschaftlicher und politischer Interessen: Spanien und Deutschland verband mehr als nur das Streben, den Verlust der Vormachtstellung auf den Weltmeeren zu kompensieren oder eine marinemäßige Präsenz des Reichs aufzubauen bzw. überhaupt einen verlässlichen maritimen Handelspartner zu finden (III.), und die Pflege ihrer verwandtschaftlichen Beziehungen (IV.). Vor allem ging es bei den Verhandlungen um eine militärische Zusammenarbeit (VI.), die dazu beitragen sollte, die abtrünnigen niederländischen Provinzen der spanischen Krone zurückzuführen und das hochsensible konfessionelle Gleichgewicht Europas während des Dreißigjährigen Krieges wieder herzustellen bzw. zu bewahren (VIII.).

Dabei gibt der Entwurf der geplanten Handelskooperation als das eigentliche Fundament und Kernstück dieser vielfältigen strategischen Überlegungen Einblick in die rechtliche Struktur der frühen privilegierten Handelscompanien, die einerseits verblüffende Parallelen zum Recht der modernen Kapitalgesellschaften aufzeigt, andererseits verdeutlicht, dass derartige Vergleiche nicht dazu führen dürfen, den Blick auf überkommene Spielarten handelsmäßiger Zusammenschlüsse zu versperren (IX.). Das Werben des Kaisers um die Mitwirkung der Hansestädte an dem Projekt und deren Reaktion zeigen schließlich, dass sich Letztere als Glieder des Reiches nicht derart verstanden, als dass sie aktiv zu dessen wirtschaftlichem bzw. politischem Wohl hätten beitragen wollen (V., X.). Die Rechtsgeschichte der bisher spärlich behandelten hansischen Spätzeit wird hierdurch weiter vervollständigt, indem durch die ablehnende Haltung der Hanse gegenüber den Versuchen des Kaisers bislang unberücksichtigte Aspekte ihrer Integration in die Reichsstrukturen zutage getreten sind. ■

NOTES

* Expanded, written version of the inaugural lecture of 27 January 2012 at Julius Maximilian University of Würzburg and the presentation held at Eötvös Loránd University, Budapest/Hungary of 30 March 2012.

[1] On the history of the stock corporation, summary with further substantiation by A. Cordes, Art. Aktiengesellschaft, in: HRG[2], vol. I, col. 132-134.

[2] For further details, C. Bauer, Unternehmung und Unternehmungsformen im Spätmittelalter und in der beginnenden Neuzeit, reprint of Jena issue from 1936, Aalen 1982.

[3] Most recently K. Jahntz, Privilegierte Handelscompagnien in Brandenburg und Preußen. Ein Beitrag zur Geschichte des Gesellschaftsrechts (= Schriften zur Rechtsgeschichte, 127), Berlin 2006.

[4] o. H. Matiesen, Die Kolonial- und Überseepolitik der kurländischen Herzöge im 17. und 18. Jahrhundert, Stuttgart 1940, pp. 77-94.

[5] Most recently S. Klosa, Die Brandenburgische-Africanische Compagnie in Emden. Eine Handelscompagnie des ausgehenden 17. Jahrhunderts zwischen Protektionismus und unternehmerischer Freiheit, diss., Frankfurt am Main i.a. 2011, pp. 24 seq. with further substantiation.

[6] K. Lehmann, Das Recht der Aktiengesellschaften, Berlin 1898, p. 60. W. van den Driesch deals with the trade relations between Spain and the Habsburg Monarchy since the 18[th] century in Die ausländischen Kaufleute während des 18. Jahrhunderts in Spanien und ihre Beteiligung am Kolonialhandel (= Forschungen zur internationalen Sozial- und Wirtschaftsgeschichte, 3), Cologne/ Vienna, 1972, pp. 427-434.

[7] The latter was dissolved again already in 1731 notably under political pressure from the major naval powers. On this "pawn" in the "overriding political interests" R. Gmür, Die Emder Handelscompagnien des 17. und 18. Jahrhunderts, in: W. Hefermehl, R. Gmür, H. Brox (ed.), Festschrift für Harry Westermann zum 65. Geburtstag, Karlsruhe 1974, pp. 167-197, here p. 177; H. Duchhardt, Europa am Vorabend der Moderne 1650-1800 (= Handbuch der Geschichte Europas, 6), Stuttgart 2003, p. 262.

[8] However, the idea is scarcely mentioned in J. Marquard, Tractatus politico-juridicus de iure mercatorum et commerciorum singulari, Francofurti 1662, Lib. III, cap. I., no. 81, p. 370 seq.

[9] On the early development phase of the Aulic Council E. ortlieb, Vom königlich/kaiserlichen Hofrat zum Reichshofrat. Maximilian I., Karl V., Ferdinand I., in: B. Diestelkamp (ed.), Das Reichskammergericht. Der Weg zu seiner Gründung und die ersten Jahrzehnte seines Wirkens (1451-1527) (= Quellen und Forschungen zur höchsten Gerichtsbarkeit im Alten Reich, 45), Cologne/Weimar/Vienna 2003, pp. 221-289.

The Rules of the Aulic Council of 1559 and the preceding council orders, including remarks in T. Fellner and H. Kretschmayr (ed.), Die Österreichische Zentralverwaltung. I. Div. Von Maximilian I. bis zur Vereinigung der österreichischen und böhmischen Hofkanzlei (1749), 2[nd] volume of records 1491-1681 (= Veröffentlichungen der Kommission für Neuere Geschichte Österreichs, 6), Vienna 1907, are available online at http://www.literature.at/viewer.alo7objid=19475&viewmode=fullscreen&rotate=&scale=5&page=1 (last visited on 13 January 2012). On the changing provisions of the council rules in general, W. Wüst, Hof und Policey. Deutsche Hofordnungen als Medien politisch-kulturellen Normenaustausches vom 15. bis zum 17. Jahrhundert, in: W. Paravicini and J. Wettlaufer (ed.), Vorbild - Austausch - Konkurrenz. Höfe und Residenzen in der gegenseitigen Wahrnehmung. 11. Symposium der Residenzen-Kommission der Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Göttingen (= Residenzen-Forschung, 23) Ostfildern 2010, pp. 115-134.

[10] For the Aulic Council, L. Gross, Die Reichshofratsakten zur Geschichte der deutschen Untersuchung, in: C. Brinkmann (ed.), Zur Wirtschaftsgeschichte der deutschen Unternehmung (= Schriften der Akademie für Deutsches Recht, 5), Berlin 1942, pp. 65-97, which documents numerous trade disputes by way of example. At this point a special word of sincere thanks goes to Dr. U. Rasche for the information; for the Imperial Chamber Court, A. Amend-Traut, Die Spruchpraxis der höchsten Reichsgerichte im römisch-deutschen Reich und ihre Bedeutung für die Privatrechtsgeschichte (= Schriftenreihe der Gesellschaft für Reichskammergerichtsforschung, 36), Wetzlar 2008, here in particular pp. 7-11, 17-19, and From the same author, Brentano, Fugger u.a. - Handelsgesellschaften vor dem Reichskammergericht (= Schriftenreihe der Gesellschaft für Reichskammergerichtsforschung, 37), Wetzlar 2009.

[11] N. Jörn, Die Auseinandersetzungen zwischen Hanse und Merchant Adventurers vor den obersten Reichsgerichten im 16. und 17. Jahrhundert, in: Zeitschrift des Vereins für Lübeckische Geschichte und Altertumskunde 78 (1998), pp. 323-348; A. Amend-Traut, Wechselverbindlichkeiten vor dem Reichskammergericht. Praktiziertes Zivilrecht in der Frühen Neuzeit (= Quellen und Forschungen zur höchsten Gerichtsbarkeit im Alten Reich, 54), Cologne/Vienna 2009.

[12] The first volume has already been published: W. Sellert (ed.) and U. Machoczek (author), Die Akten des kaiserlichen Reichshofrats. Series II: Antiqua. Volume 1: Box 1-43, Berlin 2010. On the recording project, T. Schenk, Ein Erschließungsprojekt für die Akten des kaiserlichen Reichshofrats, in: Archivar 63 (2010), pp. 285-290, online version at http://www.archive.nrw.de/archivar/hefte/2010/ausgabe3/Archivar_3_10.pdf, and on the funded project as a whole http://www.reichshofratsakten.uni-goettingen.de (both last visited on 13 January 2012).

[13] The old Aulic Council repertories classify the proceedings solely by name of claimant, with particulars on the subject matter of the dispute usually being absent. That means that in the past a complete picture of the a case could only be formed after first systematically combing through several hundred scattered files.

[14] The latter were examined by F. Lehne, Zur Rechtsgeschichte der kaiserlichen Druckprivilegien, in: MIÖG 53 (1939), pp. 323-409, on the basis of Aulic Council records, here in particular pp. 348 et seq. More recently - with the focus on case files - T. Gergen, Auseinandersetzungen um Kölner Druckprivilegien vor dem Reichshofrat (presentation as part of the conference "In letzter Instanz. Appellation und Revision im Europa der Frühen Neuzeit", Vienna, 7-9 September 2011).

[15] The significance of this administrative activity of the Aulic Council for economic history was already underscored by Gross (as in fn. 10), pp. 68 seq.

[16] This differentiated competence of the two imperial supreme courts was already stated by Jörn (as in fn. 11) for the disputes between Hanse and Merchant Adventurers, p. 347.

[17] K. Reichard, Die maritime Politik der Habsburger im siebzehnten Jahrhundert, Berlin 1867 (Digitalisat Bayerische Staatsbibliothek).

[18] F. Mares, Die maritime Politik der Habsburger in den Jahren 1625-1628, in: MIÖG 2 (1881), pp. 49-82.

[19] This subject was also taken up by A. Gindely, Die maritimen Pläne der Habsburger und die Antheilnahme Kaisers Ferdinand II. am polnisch-schwedischen Kriege während der Jahre 1627-1629. Ein Betrag zur Geschichte des dreißigjährigen Krieges, in: Denkschriften der kaiserlichen Akademie der Wissenschaften, philosophisch-historische Classe 39, Vienna 1891, pp. 14-30; J. O. Opel, Der niedersächsisch-dänische Krieg, vol. 3: Der dänische Krieg von 1627 bis zum Frieden von Lübeck (1629), Magdeburg 1894, pp. 483-511, 566-582, 642-644; O. Schmitz, Die maritime Politik der Habsburger in den Jahren 1625-1628, Diss. phil. Bonn 1903, pp. 39-64; H.-Chr. Messow, Die Hansestädte und die Habsburgische Ostseepolitik im 30jährigen Kriege (1627/28) (= Neue Deutsche Forschungen, 23, Div. Neuere Geschichte, 1), Berlin 1935; G. Lorenz (ed.), Quellen zur Geschichte Wallensteins (= Ausgewählte Quellen zur deutschen Geschichte der Neuzeit. Freiherr vom Stein-Gedächtnisausgabe, 20), Darmstadt 1987, pp. 69-74, albeit always with the focus on general historical aspects.

[20] Substantiation in Jörn (as in fn. 11), p. 324.

[21] A. Cordes, K. Jahntz, Aktiengesellschaften vor 18077, in: W. Bayer and M. Habersack (ed.), Aktienrecht im Wandel, 1[st] vol., Entwicklung des Aktienrechts, Tübingen 2007, pp. 1-45, here marginal no 18, p. 9.

[22] The privilege from the "ausführlichen Bericht über den Manifest= oder Vertrag brieff der Australischen oder Süder=Compagni im Königreiche Schweden" of 14 June 1626, fol. 4, can be found in Marquard (as in fn. (8), no. 83, p. 371. According to E. Duyker (ed.), Mirror of the Australian Navigation by Jacob Le Maire. A Facsimile of the 'Spieghel der Australische Navigatie ...' Being an Account of the Voyage of Jacob Le Maire and Willem Schouten 1615-1616 published in Amsterdam in 1622 (= Australian maritime series, 5), Sydney 1999, pp. 11-30, the foundation of this "Australischen oder Zuid Companie" goes back to the Dutch sailor Isaac Le Maire in the year 1614.

[23] H. Coing, Europäisches Privatrecht, vol. I, Älteres Gemeines Recht (1500 bis 1800), Munich 1985, for the first time makes mention of "privileged maritime trading and colonial companies", p. 524.

[24] On the history of their development, see summary with further substantiation by A. Amend-Traut, article on "Handelsgesellschaften", in: HRG[2], 11[th] delivery, Berlin, 2010, col. 703712.

[25] In addition to the privileged maritime trading and colonial companies, these also include the Italian Montes and the non-privileged companies emerging from the end of the 17[th] century; for more information, see Lehmann, Recht der Aktiengesellschaften (as in fn. 6), pp. 32-51; Coing with further substantiation (as in fn. 23), p. 524.

[26] Gmür (as in fn. 7), p. 195, and G. otruba (ed.), Österreichische Fabriksprivilegien vom 16. bis ins 18. Jahrhundert (= Fontes Rerum Austriacarum, third section Fontes Iuris, 7), Vienna/ Cologne/ Graz 1981, no. 55, pp. 273-282.

[27] For more detailed information on this, see Coing (as in fn.23), p. 527. For a summary citing a few examples of the European trade and economic area, see most recently (albeit with a few inaccuracies) also Klosa (as in fn.5), pp. 15-26.

[28] Draft of 4 September 1627, HHStA, Kriegsakten 57, fol. 10[v].

[29] For example in J. J. Becher, Politische Discurs, unchanged reprint of 3[rd] ed. Frankfurt 1688, Glashütten 1972, especially Cap. III, pp. 116-120, Cap. XXI., pp. 205-208; summary in Gmür (as in fn. 7), p. 181.

[30] A. Smith, An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, Vol. 2, Oxford 1976, pp. 569-641, especially pp. 575 et seq., 637. Moreover, Becher (as in fn. 29) also criticised the monopolies, pp. 110 et seq.

[31] Neue und vollständigere Sammlung der Reichs=Abschiede, Zweyter Theil derer Reichs=Abschiede von dem Jahr 1495. bis auf das Jahr 1551. inclusive, Franckfurt am Mayn 1747, p. 144, § 16.

[32] In this regard, K. Nehlsen-van Stryk, Die Monopolgutachten des rechtsgelehrten Humanisten Conrad Peutinger aus dem frühen 16. Jahrhundert. Ein Beitrag zum frühneuzeitlichen Wirtschaftsrecht, in: ZNR 10 (1988), pp. 1-18, here pp. 6 seq. After that, the benefit for "society as a whole" is also taken up later, for example with Becher (as in fn.29), p. 116.

[33] For further details, see Coing, p. 526; Gmür (as in fn. 7), pp. 180-185.

[34] For further details on this aspect, see H. Mohnhaupt, "Jura mercatorum" durch Privilegien. Zur Entwicklung des Handelsrechts bei Johann Marquard (1610-1668), in: G. Köbler (ed.), Karl Kroeschell zum 60. Geburtstag (= Rechtshistorische Reihe, 60), Frankfurt am Main i.a. 1987, pp. 308-323, here pp. 312 et seq.

[35] As in H. Lévy-Bruhl, Histoire juridique des Sociétés de Commerce en France au XVII[e] et XVIII[e] siècles, Paris 1938, p. 44; K. Lehmann, Die geschichtliche Entwicklung des Aktienrechts bis zum Code de Commerce, Frankfurt 1968, reprint of Berlin 1895 edition, § 3, pp. 29-48. A summary of the individual Dutch companies is provided by S. van Brakel, De hollandsche handelscompagnieën der zeventiende eeuw. Hun ontstaan - hunne inrichting, 'S-Gravenhage 1908.

[36] N. Lossaeus, Tractatus de iure universitatum, Venetiis 1601, Pars I, cap. II., no. 53 seqq. On this classification, see also Cordes/ Jahntz (as in fn. 21), p. 5. For a summary on the doctrine of the Universitas, Coing (as in fn. 23), 12[th] chap., pp. 261-265, with further substantiation.

[37] Marquard (as in fn. 8), no. 8, 9, p. 361. In greater detail, R. Mehr, Societas und Universitas. Römischrechtliche Institute im Unternehmensgesellschaftsrecht vor 1800 (= Forschungen zur Neueren Privatrechtsgeschichte, 32), Cologne/ Weimar/ Vienna 2008, pp. 232 et seq.

[38] For further details on this, see references in Lévy-Bruhl (as in fn. 35) for France, p. 42, Sir W. S. Holdsworth, A History of English Law, London 1923-72, vol. VIII, 1947, pp. 192 et seq., here especially 206-222, for England, and Gmür (as in fn. 7) for the Empire, pp. 171 et seq.

[39] For example, J. Voet, Commentarius ad Pandectas, 6[th] edit., Hagae-Comitum 1731, looks at the question of how shares can be transferred, Tom. I., Lib. XVIII., Tit. IV., no. 11, p. 793. In this regard, see also Mehr (as in fn. 37), p. 313.

[40] A classification of the incorporated companies as legal persons and their essential principles is provided by B. Windscheid, Lehrbuch des Pandektenrechts, vol. 1, 6[th] edit., Frankfurt am Main 1887, § 57, pp. 156-161 with further substantiation, with regard to the various views of different Romanists and Germanists as to who is generally the holder of rights in legal entities, ibid, § 58, fn. 3, pp. 162 seq. Most recently A. M. Fleckner, Antike Kapitalgesellschaften. Ein Beitrag zu den konzeptionellen und historischen Grundlagen der Aktiengesellschaft (= Forschungen zum römischen Recht, 55), Cologne / Weimar/ Vienna 2010.

[41] W. Bayer and M. Habersack (ed.), Aktienrecht im Wandel, 2 vol., Tübingen 2007.

[42] W. Hartung, Geschichte und Rechtsstellung der Compagnie in Europa. Eine Untersuchung am Beispiel der englischen East-India Company, der niederländischen Vereenigten Oostindischen Compagnie und der preußischen Seehandlung, Bonn 2000; Mehr (as in fn. 37).

[43] Colonisation started in 1493 with the occupation of Hispaniola, G. Parker (ed.), The Times - Große Illustrierte Weltgeschichte, Vienna i.a. 1995, p. 270. After the first journeys of Columbus, the newly discovered regions were distributed between the involved commanding powers of Portugal and Spain in the Treaty of Tordesillas in 1494: Spain was awarded all countries, the 370 the Spanish leguas, i.e. approx. 1770 km, that had already been (or were yet to be) discovered west of the Cape Verde islands, with consequently everything east of this meridional line going to Portugal. By the middle of the 16th century, the Spanish Crown succeeded in establishing the two Viceroyalties of New Spain (Central America) and New Castilla (South America). For further details on the subject, see also L. Pelizaeus, Der Kolonialismus. Geschichte der europäischen Expansion, Wiesbaden 2008.

[44] Reichard (as in fn. 17), p. 3.

[45] For more details on this, see van den Driesch (as in fn. 6), pp. 62-66.

[46] The work of B. Siegert, Passagiere und Papiere. Schreibakte auf der Schwelle zwischen Spanien und Amerika, Munich 2006, was prepared based on the documents that have been passed down to us from this authority. The files are kept in the Archivo General de Indias (general archive for the Spanish overseas colonies) located in the Casa Lonja de Mercaderes, the former stock exchange of Seville.

[47] In actual fact, the monopoly was frequently circumvented. On this, and the legal provisions and sanctions issued in this regard, see van den Driesch (as in fn. 6), pp. 80-93.

[48] Siegert (as in fn. 46), p. 51, and also on the keeping of the register pp. 50-62.

[49] Siegert (as in fn. 46), p. 15.

[50] From English "bullion" = coin bars, uncoined precious metal. For details on this, see article on bullionism in: Encyclopedia Britannica at http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/84477/bullionism (last visited on 26 September 2011).

[51] W. A. McDougall, Let the Sea Make a Noise. A History of the North Pacific from Magellan to MacArthur, New York 1993, p. 29.

[52] In this regard, see HHStA, RHR, Antiqua, 29/2.

[53] In this regard, see petition to withdraw the imperial trade permit by the imperial fiscal prosecutor Dr. Johann Wenzel, HHStA, RHR, Antiqua, 27/1, 28/1, 29/3, 29/4, 29/5, 29/6, 29/7, 29/8, 29/9, 29/10, 29/12, 29/13, 29/20, 29/21, 29/22, 29/26, 29/27, 30/3. Summary by A. F. Sutton, The Merchant Adventurers of England. Their origins and the Mercers' Company of London, in: Historical Research 75 (2002), pp. 25-46, Jörn (as in fn.11).

[54] HHStA, RHR, Antiqua, 29/17, fol. 1[r]-2[r], 5[r]. Summary in this regard by Jörn (as in fn. 11), pp. 339-347.

[55] HHStA, RHR, Antiqua, 29/32, fol. 1[r]-3[v].

[56] HHStA, RHR, Antiqua 12/4, Kaiserliche Privilegien an die beiden Städte fol. 39[r]-42[v] for Hamburg, fol. 43[r]-46[v] for Magdeburg, Mitteilung der Einsetzung einer Kommission, fol. 205[r].

[57] HHStA, RHR, Antiqua 12/4, fol. 117[r].

[58] HHStA, RHR, Antiqua 13/1b, fol. 1[v].

[59] von den Driesch (as in fn. 6), pp. 14 et seq., 17-20, 418 with further substantiation; Jörn (as in fn. 11), p. 332.

[60] For more detailed information, see Jörn (as in fn. 11), p. 333.

[61] On this, see B. Vacha (ed.), Die Habsburger. Eine europäische Familiengeschichte, Vienna 1992.

[62] Regarding the staple right, see M. Hafemann, Das Stapelrecht. Eine rechtshistorische Untersuchung, Leipzig 1910, here in particular p. 29; U. Dirlmeier, Mittelalterliche Zoll- und Stapelrechte als Handelshemmnisse?, in: H. Pohl (ed.), Die Auswirkungen von Zöllen und anderen Handelshemmnissen auf Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft vom Mittelalter bis zur Gegenwart. Referate der 11. Arbeitstagung der Gesellschaft für Sozial- und Wirtschaftsgeschichte vom 9. bis 13. April 1985 in Hohenheim (= Vierteljahrschrift für Sozial- und Wirtschaftsgeschichte. Beihefte, 80), Stuttgart 1987, pp. 19-39. Information on individual staple rights and related literature available through the portal funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG), the "Joint Portal for Libraries, Archives and Museums" (BAM-Portal) (last visited on 27 September 2011).

[63] HHStA, Kriegsakten 57, fol. 12[v].

[64] F. C. Khevenhiller, Annalium Ferdinandeorum, Darinnen Königs und Kaysers Ferdinand des Andern dieses Nahmens, Handlungen ... Wie auch Alle denckwürdige Geschichte, Geschäffte, Handlungen, Regierung vol. 11, Vom Anfange des 1628. biß zu Ende des 1631. Jahrs, col. 143. Established subsequent to a letter of the Emperor dated 23 February 1628 in which he emphasises the necessity of participation of the Hanseatic Cities, col. 134-143.

[65] HHStA, Kriegsakten 57, fol. 13[r].

[66] HHStA, Kriegsakten 57, fol. 11[r].

[67] HHStA, RHR, Antiqua, 30/1, fol. 189[v], under point 8.

[68] HHStA, Kriegsakten 57, fol. 11[v], 12[r].

[69] Mareš (as in fn. 18), p. 67.

[70] Duchhardt (as in fn. 7), p. 222.

[71] These began with the decision of the statutory privy council and other councils to send the member of the Aulic Council, counsellor Dr. Hans Ulrich Hämmerle who in the trade dispute with England had acquired the respect of the Hanseatic Cities, to Lübeck as a delegate of the Emperor in order to clarify whether there was a general willingness to establish the company in question, HHStA, RHR, Antiqua, 30/19, undated, around 1626, fol. 1-6. Then HHStA, RHR, Antiqua, 30/1: kaiserlicher Befehl vom 21.10.1626 zur Berichterstattung darüber, welche Mittel die Hansestädte vorschlagen, um die zuvor angebotene freie Seefahrt nach Spanien zu erlangen, fol. 5[r]-6[r].

[72] von den Driesch (as in fn. 6).

[73] With regard to him, see F. von Krones, Art. Georg Ludwig von Schwarzenberg, in: ADB, Volume 33 (1891), pp. 303-305.

[74] Imperial letter dated 4 September 1627, HHStA, Kriegsakten 57, fol. 6[r]-9[v]. The broad basis on which the plans had been developed is summarised in Mares (as in fn. 18), pp. 53 et seq.