Leon van den Broeke[1] - George Harinck[2]: The Liberal State, the Christian State and the Neutral State: Abraham Kuyper and the Relationship between the State and Faith Communities (GI, 2020/3-4., 9-28. o.)

1. Introduction

In 1879, five years after Abraham Kuyper (1837-1920) left the ministry in the Dutch Reformed Church, the book 'Ons Program' of the 42-year old journalist saw the daylight.[1] Kuyper was the leading journalist of his days in the Netherlands, but he would also be the main founder of the Vrije Universiteit (1880), a professor of Theology (1880-1901), founder of a free church (1886, 1892) and a Member of Parliament (three terms) and prime minster (1901-1905) of his country. 'Ons Program' was a collection of Kuyper's earlier political thoughts of more than 1300 pages, which had been published in the previous decade in his ecclesial weekly De Heraut and his daily newspaper De Standaard. In 1878 this collection of articles was (re)published by the Central Committee of the Anti-Revolutionary Electoral Associations. Kuyper is a towering and many-faceted figure in Dutch history.[2]

In our contribution we focus on Kuyper's early political thoughts on the relationship between faith communities and state. The church was too limited for him, although the pulpit gave him the possibility to spread not only his theology and ecclesial message, but also his political and societal

- 9/10 -

considerations. From the start of his career, he not only had a message for the church and its members, but also for the state and the whole nation. He sought general principles of law. In vain he tried to find them in history, law, and philosophy. He was convinced that God reveals himself by vesting governing authorities with sovereign power. He found these general principles of law in the Holy Scripture as the 'certificate of that revelation' (paragraph 31). These governing authorities could find these principles not only via the special revelation, but by the general revelation as well.

In this contribution we focus on the leading question why Kuyper rejected the liberal state, but also the Christian state, and aimed for the neutral state, what his motives were and what this meant for both the state and faith communities, specifically for the Jewish faith communities in the Netherlands. First, we present Kuyper's general thoughts on the relationship between church and state from his 'Ons Program'. This includes his vision on the state and the church (including their relationship), three systems of church and state relationships, and the concept of sin when it comes to the nature of the state. Thereafter we consider the implications of Kuyper's view on the separation between the state and faith communities. The next paragraphs deal with other types of relationships between the state and faith communities, according to the three models Kuyper treated in his 'Ons Program'. The second part of this contribution consists of a case study. We not only focus on the church, but on faith communities, more specific on the position of Jewish communities in the Netherlands.

2. Kuyper's view on concepts of the state

According to Kuyper the state is a moral organism which has a head: the governing authorities. The state not only ought to honor God, but it is also the servant of God. This limits and reveals the power of the state.

2.1. The first concept: the liberal state

Although, Kuyper was of the opinion that with the God-less state the liberals tried to increase the power of the state and minimize the sovereign authority of God. The liberal view of the state was one of the concepts of the state Kuyper mentioned. He rejected this liberal concept, because the liberals did not only reject the supranatural, but also the natural knowledge of God and by consequence they ignore God.

- 10/11 -

Kuyper objects the liberal state which nature is a contract. It chooses its justification in the free choice of people. Kuyper took a keen interest in the free choice of people, but in the state and in religion, he could not agree with this concept of the state as a contract with people, because the spiritual father of the free choice of people is the British monk and theologian Pelagius (ca. 354-418),[3] the opponent of Augustine of Hippo (354-430). In fact it was connected with Pelagius' earlier considerations about the nature of grace.[4] The same goes for Augustine.[5] Pelagius' theory of the free choice of and absence of sin among people very much contradicts God's predestination.

The free choice of men, liberty, freedom of oppression, became a central notion in the Enlightenment. This became also apparent in the theory of the state as a contract. The theory of the (liberal) state as a contract - social contract theory - is rooted among others in the work of the English philosopher Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679), in his book Leviathan of 1651.[6] According to Hobbes, the state becomes 'that Mortal God' - named after the biblical monster Leviathan - 'to which we owe under the Immortal God, our peace and defence'.[7] Hobbes referred to Abraham as 'the first in the Kingdom of God by Covenant', as God made a contract with Abraham.[8] Hobbes was of the opinion that people had two choices: the primal situation, which is the absolute anarchy situation, or the irrevocably submission to the state. Hobbes considered the social contract according to which people transfer their natural rights, in the mutual transferring of right, different from the state of nature where everyone has the right to everything and where are no limits to the right of natural liberty.[9] It is in the interest of everybody to render a part of one's personal power to a central body, the state, the so-called pactum subjectionis.

Not only in political views in the eighteenth century (Enlightenment) and before, like the one of Hobbes, but also in the field of church polity we see

- 11/12 -

in the uprise of the systema collegiale, the theory of collegialism, as the German jurist Just Henning Böhmer (1674-1749) mentioned it.[10] The German theologian Christoph Matthäeus Pfaff (1686-1760)[11] and the German church historian Johann Lorenz von Mosheim (1694-1755) were influenced in their view of legal foundations by the German jurist Samuel Freiherr von Pufendorf (1632-1694). The church was considered by them as a societas, a collegium, an ordinary association. In general, the nature of collegialism is that people choose the church of their favor. Collegialism is about the sovereignty, equality and freedom of individuals, a societas aequalis et libera.[12] One could speak of collegial religion.[13] More specific, collegialism has a couple of characteristics. First, the formation and reformation of the church is grounded in the free will of individual persons. Second, the church is not founded by God, but is an association of people. This means that membership is not grounded in the covenant (of grace) and/or baptism, but in the individual choice of people. Three, the source of authority is rooted in decision by majority, just like in the idea of people's sovereignty. Four, the relationship between church and state means that the church is no longer characterized by public law if the church is no more than an ordinary association.[14]

Apart from criticism from Reformed experts in church polity, like the German jurist and legal philosopher Friedrich Julius Stahl (1802-1861) who considered the collegial system to be rooted in disbelief as it replaced the order of God by the decisions by headcount,[15] the effects of collegialism were manifest deep in the nineteenth century, not only in Germany, but also in the Netherlands. The church order for the Netherlands Reformed Church, the so-called Algemeen Reglement (General Regulations) of 1816, imposed by King Willem I, is collegial in nature. It was this church and its type of church

- 12/13 -

governance against which Kuyper protested, even as a Reformed minister. In 1886 he broke away from this denomination to form his own, with a decentral Reformed model that had not much in common with collegialism. But he did adopt the notion that the source of authority is rooted in decision by majority - the above-mentioned third characteristic of collegialism -, which means sovereignty by the people. This was something that attracted Kuyper and which he included in this ecclesial model for 'his' Reformed Churches in the Netherlands.

The notion of people who choose to join a church started dominating the notion that God gathers his people in church. In the theory of collegialism the New Testament key word ekklèsia is overshadowed, but also another keyword from the Early Church, namely kuriakè. Ekklèsia means assembly, gathering, meeting, congregation or church.[16] It sounds familiar in the French word église and the Spanish word iglesia. Kuriakè means: what is or belongs to the Kyrios (Lord) - Jesus Christ. We find resemblances in the Dutch word kerk, the German word (Kirche) Scottish and Danish/Swedish word kirk. According to the theory of collegialism it is not God who gathers people, but it is people who choose whether or not to gather and join a faith community as if it is an association.

According to Kuyper it cannot be that the will and the word of people is the ground of all being, also not in and for the liberal state, and that the reality of God's election is being ignored.

2.2. The second concept: theocracy

Kuyper also rejected the concept of the state church. With this rejection he not only aimed at the Roman-Catholics, but also at inconsequent protestants. Both of these groups have theocracy in mind. They give the state an authoritative position regarding both the natural and supranatural knowledge of God. In this way they picture the state as active patron of the Kingdom of God, like in the Middle Ages, and, as for the Protestants, partially in Prussia. But this would only be possible if the state would be a supranatural power or organ, but there is no such thing and there should not be such a power or

- 13/14 -

organ, otherwise the state will become spiritual and the religion will secularize. What is different in nature should not to be mingled. This also goes for church and state. The state is not equal to the Kingdom of God and the Kingdom of God does not fit in the limited forms of the state's life. Kuyper rejects every effort to revitalize the Christian state. He opposed men like the German Lutheran theologian Richard Rothe (1799-1867) who, without boundaries, let the church wrap up in the state and the state in the Kingdom of God. Rothe was 'the apostle of the socialization of the Gospel in a Christian state and culture that will ultimately encompass all humanity, and opponent of all clericalization of life', as the Dutch church historian Jasper Vree (1943-2020) wrote.[17]

2.3. The third concept: the neutral state

Therefore, Kuyper opted for the third choice: the political and yet confessing state of the Reformed or Puritan people who ground the state on the natural knowledge of God (theologia naturalis). This type of knowledge is binding for everyone. By consequence the administration is only active in the sphere of natural knowledge of God. In the sphere of the revealed knowledge of God the state is only passive as maiden servant of God. Kuyper points, as an example, to the United States of America, because there the state honors the seventh day of the week and writes out days of prayer, and at the same time it acts more neutral towards all churches than any other European country. Kuyper sought a system which was practical, and would match the political life with the everyday life of the people. It should be a system in which the Christian would feel him- or herself at home.

Such a Reformed concept of the state should include equal rights for everyone. By consequence this includes equal rights for anyone in the religious domain. The national authorities, although with predilection for the Gospel, should never be misled by banning or binding religious opponents of the Gospel, and favoring one faith community above other faith communities. This characterizes the neutral state: no privilege for whatever faith community or religion. This includes a ban on protection, prevention or repression of any faith community or religion. The national civil authorities avoid the decoy of choosing and favoring one faith community.

By the grace of God Kuyper saw as the task for the governing authorities

- 14/15 -

to: 1. execute the authority as maintainer of Gods law; 2. maintain the oath as the cement of the state's building; and 3. set free the day of the Lord.

3. Separation of church and state

It is clear that Kuyper aimed for the above-mentioned third concept of the state: the neutral state. Faith communities and state should not be mingled, because they are both different in nature. There should be a wall of separation between them, but not a too high and thick wall. Although Kuyper seems to plea for a kind of separation, he nonetheless does not aim for the French model of laicité, for this model was far from neutral. Moreover, it would not match with Kuyper's thoughts on the nature of the state. Although he favors the neutral state which does not promote, protect or oppress one or more religions and/ or faith communities, he considers the state as the maiden servant of God, based on the concept of the natural knowledge of God. This means that the neutral state is not ignorant when it comes to religion, faith communities and the presence of God in the rule of law. A separation between state and faith communities does not exclude their cooperation for the benefit of society.

4. Other types of relationships between the state and faith communities

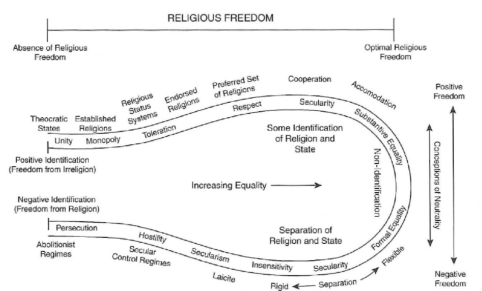

Kuyper includes in 'Ons Program' three concepts of the state. It expresses the situation in the 1870s as he considered and experienced it. He declined the liberal world view, but also the roman-catholic and Netherlands Reformed positions, specifically with view to the relationship between the state and faith communities. It is understandable that Kuyper acted and reacted in this way as a child of his time. Nonetheless, apart from the strengths of his argument it has also its shadow sides. It is far from complete for example. There are more models or types which express the relationship between the state and faith communities than the three Kuyper considered in his 'Ons Program'. W. Cole Durham Jr., an American expert on the relationship between faith communities and state, developed the loop model.[18] The loop has two

- 15/16 -

axes: religious freedom (on the scale between on the one hand absence of religious freedom and the optimal religious freedom) and conceptions of neutrality (positive freedom on the one hand and negative freedom on the other hand). The loop also includes a scale between positive and negative freedom. With positive freedom is meant a range between positive identification (freedom of irreligion) and some identification of religion and state. With negative freedom is meant the range between 4. separation of religion and state, and 5. negative identification (freedom of religion). In between positive and negative freedom is non-identification.

Cole Durham: The loop model of the relationship between faith communities and state.

5. Application of Kuyper's concept of the state: the Jewish community

The loop model raises questions Kuyper may have overlooked when applied in a specific country and/or with view to specific faith communities. Therefore, in this paragraph, we focus on such an application of Kuyper's model of the state for the Jewish faith community in the Netherlands.

- 16/17 -

5.1. Dutch Republic

The Jewish community in the Dutch Republic had been recognizable as a distinct group of people within society. The public church in the Republic was the Reformed Church, that was relatively independent from the state, but always had to be in concord with the state. This privileged church had a public role, and a different position compared to other religious communities - Protestant (Anabaptist, Lutheran, Remonstrant) and Catholic -, and to the Jewish community. But the Republic was a safe haven for Jews. There were no pogroms, and no ghettos. And though the Reformed Church had its local church buildings on the main square and in the main streets (often former Roman Catholic churches), other religious communities were tolerated to practice of their religion. And over time, they also could build churches - or synagogues for that matter -, visible in central public places, like the Lutherans and the Jews did in Amsterdam in the seventeenth century; in other places the degree of freedom was often smaller. The position of the Jews in society was demarcated: they were a separate 'Jewish nation' (a medieval legal concept) within the Republic, with a Sephardic and Ashkenazi branch, alongside other 'nations', consisting of people who originally came from abroad, and who were granted certain rights. They were integrated, but had their own organizations for care for the poor and sick, and for education.[19]

5.2. French intermezzo

In the French intermezzo in Dutch history (1795-1813) the Jews were granted full citizenship. For the first time Jews had the same rights as other Dutch citizens. Thy now belonged to the 'Dutch nation'. This situation would not change any more - with the exception of the five years of German occupation in the twentieth century. When the kingdom of the Netherlands was founded in 1813/1815, the Jews did not only keep their equal position, they were also privileged. As to education, Jewish primary schools were founded with public money, alongside the public schools with a Christian character, in line the dominant religion of the Dutch nation.[20]

- 17/18 -

5.3. Constitution of 1848

The new Constitution of 1848 was of a liberal nature. This meant full religious freedom for Christians and Jews alike. This led in 1853 to the restoration of the Dutch catholic Church province, with bishops and all, a major turning point in the religious history of the Netherlands after its exclusion from the Dutch Republic in the late sixteenth century.[21] Churches - and sects for that matter - were fully free, but positioned outside of the public domain, and in public institutions confessional religion was replaced by a more general 'religion beyond religious divisions'.[22] This resulted in a rather strict separation between church and state. The liberal Constitution implied a religiously neutral public domain. Of course, politics and the media were still dominated by Protestants, but as Protestants they were predominantly liberal. Together with the new Constitution and the dominance of political liberalism, a dominating liberal Protestant culture developed. While the theological departments of the universities of Groningen and especially Utrecht were more on the orthodox side, at around 1850 Leiden university became the bulwark of the so called 'modern theology'. This theology was influenced by the prominence of natural sciences and by the critical-historical method in the humanities. Miracles were denied, including Christ's rise from the dead, and the Bible was not so much a revelation as a flawed historical document. The modern theologians wanted a 'second Reformation', to update Christianity to make it fit for modern times.[23] The religious liberals joined forces with the political liberals and dominated the public debate in the 1850s and 1860s. Most Catholics and Jews favored political liberalism, for this had brought them full freedom as citizens, also religiously. The orthodox Protestants were the first to feel uneasy under this liberal regime. They enjoyed religious freedom, but had to get adjusted to the situation that other denominations and other religions enjoyed exactly the same freedom, the arch-enemy Roman-Catholicism included. By and by they started to organize themselves and give voice to their opinion in a dominantly liberal context.

- 18/19 -

5.4. Education

What did this situation of dominant liberalism mean for the schools, the most important institution for developing a nation? Education was a liberal project. Liberalism was based on reason, and it was education that would people learn to use reason and to discern what is reasonable from what was superstitious, traditional or habit only. The people had to be raised to good citizenship, the needed 'lux et libertas', as the motto of a prominent liberal newspaper was worded. The light of reason would make them free. What this meant for education was unclear until 1857, when a new law on primary education was adopted, that was in line with the new Constitution. This new law required education in all 'social and Christian virtues'. That formula was a disappointment to orthodox Protestants, for it was not explicitly orthodox, and also made room for liberal Protestantism and 'religion beyond division'. In the new Constitution the Protestant character of the Dutch nation - in the 1850s-1870s 60% was Protestant, 37% Catholic, and 2% Jewish - and the Protestant stamp on its history had not been acknowledged. The orthodox Protestants saw the negative consequence of this omission realized in the new School Law of 1857. This law ignited a movement, on the one side to change this law in an orthodox Protestant sense, and in the second place to establish Protestant schools, for the moment without public funding. This resulted in the so-called school struggle.[24]

This was a Protestant movement only, until about 1870. In 1868 the Catholics in the Netherlands changed allegiances. The liberals had brought them full religious freedom, but the School Law of 1857 made them realize, that this freedom came with a prize. For Catholicism was formally banned from the primary schools, and they aligned with the Protestant school struggle. This struggle became more serious when Abraham Kuyper entered the scene. In 1860 he argued that Protestant parents should not send their children to the public school anymore, for that was Satan's place. They should all send their children to the Christian school instead, and support these school, who were without government funding.

- 19/20 -

5.5. Kuyper and the freedom of education

Kuyper's participation in the debate changed the scene. Up till then the issue was if the public school, and for that matter the public domain, would be liberal or Protestant. Kuyper changed the issue. Think of Catholicism: it does not fit in the dichotomy liberal versus Protestant. He took into account the variety of religions and convictions, all enjoying full freedom and equal rights since 1848. Kuyper embraced the Constitution of 1848 but wanted to push liberalism to a next phase. If liberals promise freedom indeed, they should not require public education to be liberal, but leave room for any worldview that was around amongst the Dutch. In Kuyper's opinion this liberal restriction of the freedom of education revealed the true nature of political liberalism. This liberalism was a caricature of what Protestantism advocated. Protestantism - later Kuyper would prefer to say: Calvinism or Neo-Calvinism - proclaimed freedom of conscience: the church or the state should not enforce a religion. Any religious compulsion 'clashes most vehemently with the character of the Christian faith', as he put it his political program of that same year.[25] Political liberalism now wanted to force the Dutch to become liberal, by excluding confessional teaching of orthodox Protestantism, Catholicism or Judaism from the public school. This aim revealed that this liberalism rooted in the anti-Christian French Revolution of 1789, and not in Protestantism. The liberal position was not a neutral one, but an anti-Christian one. To Kuyper political liberalism and modern theology were two sides of the same coin.[26]

5.6. Antirevolutionary viewpoint

Kuyper therefore corrected this liberalism, by stating that his antirevolutionary viewpoint - he sometimes called this 'Christian liberalism' - was bolder and more consequential when it came to freedom, compared to the liberal one - which he labelled as 'liberalist' - by also making room for error and apostasy.[27] The battle should therefore not be about the orthodox Protestant viewpoint versus the liberal viewpoint, but about the plural character of the

- 20/21 -

public domain instead of a public domain claimed by the liberals only.

This fierce opposition of liberalism changed the scene, not only in the public debate, but also in politics. Kuyper became the editor of his newspaper De Standaard in 1872 and a Member of Parliament in 1874. From that moment on the opposition to liberalism as a suppressing ideology in general and against liberal school politics specifically became a theme in the national debate, it was no longer an issue for orthodox Protestants only.

5.7. The Jews

And here the Jews come in. The liberal project was a national project, aimed at integrating the Dutch people as a unified community, a nation, including Jews, not on a religious base, but based on the notions of Enlightenment and French Revolution. The Jews were grateful to the liberals for this inclusion and their full citizenship. They most of the times joined the political liberals, and several liberal politicians were Jewish. The school law of 1857 meant the end of publicly funded Jewish schools. They would integrate, or even assimilate in the Dutch nation. The Jews, who had had their own schools for decades, readily joined the liberal position and became part and parcel of the public school - with the exception of some orthodox Jews. 'Whereas the number of private confessional (Protestant and Catholic) primary schools grew by 843% during 1870-1930, the number of Jewish schools declined by 62%.'[28] There were other reasons for this course as well: their small numbers, their lack of homogeneity, their geographical distribution.[29]

When Kuyper presented his new paradigm, plural versus uniform, this meant a critique of the liberal position, and, on a different level, also a repositioning of Protestant religion, and religion in general. For if the public domain should be plural, it degrades liberalism from the dominant and neutral position they claimed, into just one of the opinions in the Dutch public debate - and, Kuyper stressed, a minority position, since he claimed the Protestants and Catholics were the large minorities. This Kuyperian position implied that no confession should dominate legally. The state should be neutral in the positive sense. According to the above-mentioned model of Cole Durham, Kuyper can be positioned between some identification of religion and state, and separation of state and religion, so non-identification. A Protestant dominance was still

- 21/22 -

the reality in the 1870s, but that was about numbers, and these could change. Denominations and confessions could not define the public domain, the Antirevolutionary Party only defended a public acknowledgement of a natural theology, but this depended on having a political majority. So, according to Kuyper there should no longer be a direct link between state and Christianity, only a link between Christianity and the public domain, and, at best, a cultural link between the state and natural religion.[30]

The Jews did not act like Kuyper would have preferred. In his view religion or worldview defined your identity, in the private sphere as well as in the public domain. His plurality-paradigm presupposed that everyone had a religion or worldview - a neutral position based on reason did not exist, according to Kuyper - and that everyone would express his conviction in the public domain, in politics, education, and the media in the first place. So, when the Antirevolutionary Party was established in 1879, he expected the Catholics, liberals, Jews and radicals or socialists to do the same and establish political parties based on their worldview. And they did, with the exception however of the Jews. Many Jews did not want to be Jews in the first place in the public domain. They had had this position in Europe for centuries, and they were relieved liberalism in the nineteenth century liberated them from this distinct and second-rate place in society. They were 'intertwined with the liberal agenda'.[31] For this reason they joined the liberals, and for that matter later on in this century also the socialists. To Kuyper this was inconsistent. Now that Jews had an equal position, they should act like the Protestants and the Catholics, and claim their place in the public domain as Jews. But they did not do this.

5.8. Kuyper and Jews

Kuyper was disappointed in the Jews. Why did the Jews join the liberals instead of claiming their own Jewish position in Dutch society? This question was addressed by Kuyper in a series of editorial articles in De Standaard in the Fall of 1878, later that year published as a pamphlet, titled Liberalisten en Joden [Liberalists and Jews] of 1878. As said, his complaint was that liberalism resisted the Christian school movement and curtailed the freedom

- 22/23 -

of conscience. That is why the title of the series and of the pamphlet is not Liberals and Jews, but: Liberalists and Jews. Liberalism had gone astray by, taking its starting point in the French Revolutionary viewpoint, suppressing other worldviews.[32]

The publication date is relevant, for 1878 saw the culmination of the conflict between Kuyper and the antirevolutionary movement with the political liberal movement. The school struggle had developed into a bitter fight, in which Kuyper disqualified liberals as pagans, and the liberals depicted Kuyper as a Christian theocratic tyrant. Kuyper had won a moral victory in August 1878, by presenting a petition to the king in favor of Christian schools, signed by more than 300.000. Catholics collected another 160.000 signatures. This was quite a feat in a country with four million inhabitants and no more than 100.000 voters - it was the largest mass protest in Dutch politics in the nineteenth century.[33] Notwithstanding this protest, the liberals looked down upon the low social status of the signers, and adopted the new law on education, thwarting the Christian schools. In short, in 1878 a 'civil war' or culture war was waged in the Netherlands.[34]

In these days Kuyper wrote a series about Jews and liberals. The conflict over a uniform or pluriform public domain was as far as Kuyper concerns also a conflict between orthodox Christians on the one side and modern or apostate Christians on the other side. To explain the cooperation of Jews and modern Christians Kuyper started by analyzing the position of Jews in Dutch society. Kuyper was positive about the legal equality of Jews since the late eighteenth century: 'Deeply ashamed over its own former injustice', Kuyper wrote, 'almost all Christian countries have welcomed this meaningful product of the revolution as one of its best consequences.'[35] But soon Christians realized that it was a mistake to emancipate Jews on liberal conditions only. The emancipation should have happened in a Christian way, by preaching the gospel to them. Instead the Jews were welcomed warmly, without really inviting them in in this Christian nation. This invitation without obligation

- 23/24 -

had in fact promoted the role and influence of the talented Jewish minority beyond measure. They had connected with the dominating liberal worldview and had won influential positions in politics, in the press, in law courts, in education, in banking and at the stock exchange, Kuyper wrote.

Although emancipated and prominent, the Jews did not assimilate, but kept on being a distinct group. This distinctiveness was stressed by Kuyper: 'Jews in all corners and farthest parts of our continent have stayed a nation in a much stricter sense, than any European people ever was a nation.'[36] Kuyper praised this preservation as God's providence, and distanced himself from the disdainful contempt for Jews in certain German circles.[37]

5.9. Jews and liberalists

After this description of the position of the Jews as a distinct and influential nation within the Netherlands, he came to his main argument: the liaison between Jews and political liberals. Modern Christians like the liberals resembled the Jews, by dismissing the unique position of Christ and adopting the negative Jewish religious position over against Christianity. Because of their religion, Kuyper wrote, the Jewish position could be no other than negative towards Christianity, but the apostate Christians had deliberately chosen this position. He had criticized the liberals many times for their adherence to the ideals of the French Revolution, but to him the essential fallacy of the liberals was their anti-Christian stance. And while the Jews as a nation would stay in touch with their religious and social tradition, modern Christians would finally degrade to the level of Paganism, sorcery, idolatry, and bestiality.[38]

At this moment the liberal press reacted to Kuyper's newspaper series. To them Kuyper was an orthodox tyrant, and they accused him for giving the Jews no choice, but to convert to Christianity or to deprive them of their civil rights.[39] This caricature of Kuyper's position was in line with the way he had been depicted by the liberals in this culture war. Answering the reproaches in the liberal press, Kuyper stressed that his arrows were not aimed at the

- 24/25 -

Jews, who had joined the liberals, but at the liberalists who had approached the religious position of the Jews in their rejection of Christianity. As to the Jews, he said once more he distanced himself from disdaining Jews, but at the same time he repeated carefree the usual stereotypes of his days. He not only mentioned they rejected Christ as Messiah, but also that Jews had nailed Christ to the cross and killed him, and therefore had a blood guilt.[40] And he also mentioned their different physique, appearance, complexion, character, attitude, dress, look, tone, and occupation.

5.10. Kuyper's take on Jews

How did Kuyper deal with Jews in this pamphlet? I ask attention for three aspects. He stressed that Jews were not his target, and he indeed did not propose any solution to the Jewish question. The main theme was: the Netherlands as a Christian nation under siege. As said, a culture war between Christianity and liberalism was going on in 1878. According to Kuyper, the liberals were not moderate Christians, in the end part and parcel of the Dutch Christian tradition, but, to the contrary, they were in his opinion active anti-Christians, that have joined the Jewish position over against Christianity, and tried to exclude orthodox Christians from government positions and to terminate Christian schools. So, the Jews functioned in his series to highlight the antiChristian position of the liberals. This function implied a right-out criticism of the Jewish religion, and took the controversy between Christianity and Judaism as the most basic one in the Netherlands, and in European culture for that matter.

Secondly, Kuyper's focus on the large influence of Jews in society and their coalition with the ruling liberals, made this pamphlet more than plain anti-Judaist. He made his readers aware of the large Jewish influence in society, accentuated their physical difference, and demarcated their distinct position in society. He claimed the right to do so, for these were in his opinion not offenses against Jews, but mere facts. He had always demarcated differences between religious groups explicitly, and treated for example the Catholics and other opponents in the same way, and he labelled liberal protests against his presentation of these facts as annoyance about his disclosure of their anti-Christian position. The result was a presentation of the Jews as a unified and oppositional element in society.

- 25/26 -

And thirdly, one time he qualified the Jews in this pamphlet as guests.[41] As citizens, the Jews belonged to the same kingdom of the Netherlands as every other Dutchman, Kuyper wrote, but they were not of the same nation. He took a nation as a moral community, with a shared history, language, and religion. The Netherlands was not a Jewish, not an Islamic, but clearly a Christian nation, and the Jews had always been a distinct nation within the Republic. Their full citizenship in the Kingdom of the Netherlands had altered this position legally, but not culturally. To the contrary, Kuyper wrote, among the nations the Jews were the nation by excellence.[42] And Scripture teaches that the Jewish nation will not be exterminated. If a nation would tolerate another nation in its midst on an equal footing, was a question of numbers, Kuyper wrote. He did not address this issue any further, but it may have sounded like a warning, when he estimated that one out of four Dutchmen was a Jew, that is: a million. In Amsterdam, where half of the Dutch Jews lived, this impression might resonate, but this number is a gross overstatement; in 1879 two percent (81.000 persons) of the Dutch population where Jewish, and twelve percent of them lived in Amsterdam.[43]

Notwithstanding his religious, social and national reservations, Kuyper would resist attempts to deprive Jews of their legal rights, or create specific rights for them. British liberals and Bismarck in Germany had proposed to exclude Jews from public offices, but he wrote that, if Jews would not have had full civil rights in the Netherlands, he would be in favor of granting these.[44] This is a position he repeated several times in his political career, also when he was prime minister of the Netherlands, from 1901 till 1905.

Kuyper did not give a clear reason for this pamphlet, which we now would call antisemitic, though this word was not in use yet in 1878. He was building up his Antirevolutionary Party, which he would establish half a year later, and after the successful mass petition of August 1878 this was another success. The international antisemitic actions may have directed his attention to the position of the Dutch Jews, but in 1878 he was not in need of rallying support on an antisemitic agenda. He did publish the newspaper series as a pamphlet in reaction to critical comments in the liberal press, but he did not react to Jewish comments to the pamphlet, and would not make antisemitism a theme in his political career.

- 26/27 -

It is our historical understanding that Kuyper chose to write on the Jews, because they were the opposites of the Christians. For centuries they had embodied the anti-Christian position in Europe. And now that Kuyper in his take on the modern, plural society and democracy put worldview in the foreground, and therefore accentuated religious differences, the difference between Christianity and Judaism became more prominent. And since the liberals according to Kuyper copied the Jewish position, it is the coalition of Judaism and liberalism that was the real danger to the neutral state and its plural society based on Protestant or Calvinistic principles. Like he blamed the liberals for having betrayed Christianity, so he blamed the Jews for having betrayed the religion of Israel by rejecting Christ as messiah. Kuyper wrote positively on Jews as well, and he stressed this in his polemic with liberal newspapers, but when it came to reaching out to Jews, it was in the missionary mode only. Catholics and liberals should in his opinion also be converted to orthodox Protestantism, but missionary activities in the direction of these groups were about absent. It was the Jews that had to be converted in the first place, out of love for God's covenant with them, but also because they hardened their hearts - that is why the church had substituted Israel as God's chosen people, according to Kuyper. This was theological frame.

The position of the Jews in the school struggle and in the development towards a plural public domain was at odds with Kuyper's view of a plural society. This view fitted well in Kuyper's notion of freedom conscience, and of common grace, but it conflicted with Kuyper's view of the deepest antagony in Dutch politics and society, the opposition of Christianity and non-Christianity, formulated by him in the notion of antithesis. On the one hand he would place Protestants, Catholics and Jews on the theist side, on the other hand, he considered the Jewish position as the enmity of Christianity par excellence. That is why he wrote that Jews had not moved over to the liberal position, but that liberalism had adopted the Jewish position. So the most fundamental dichotomy in Kuyper's 1878 pamphlet was Christianity and Judaism.

6. Concluding remarks

This contribution is about Kuyper's rejection of the liberal state, but also of the Christian state. Kuyper aimed for the neutral state. His motives for rejecting both the liberal and the Christian state were on the one hand the free choice of men from a religious point of view (the liberal State) and on the other hand theocracy (the Christian state). Both positions did not do justice to the

- 27/28 -

Christian faith. From the perspective of the relationship between church and state, Kuyper's preference for the neutral state meant a separation of faith communities and the state, and also that there is no space for privileges for whatever faith community or religion in the neutral state. In this way the churches could be real free churches, without stating that a church would be collegial in nature, belonging to the collegial system.

Approaching Kuyper's view from the perspective of the above-mentioned Jewish case in the Netherlands, the Jews showed the limitation of Kuyper's view of a pluriform public domain. They did not act as they should, according to his paradigm, and did not strive for being facilitated to live out their worldview in the public domain, but joined the liberals instead. This inconsistency - in Kuyper's eyes - led him to blame the liberals for having adopted an anti-Christian position, and as such had started to resemble the Jews, the arch-enemy of Christianity. But this inconsistency also showed the limits of Kuyper's societal view. What if a citizen would not have his place and role determined by his worldview, and what if a citizen would not count himself as a member of a group, but as an individual? These questions reveal the limits of Kuyper's s solution, and they also remind us the present-day challenge of respecting the freedom of religion for all citizens alongside respecting the will of citizens to be free of religion. The casus of Kuyper and the Jews as a faith community helps us to understand the downside and the challenges of his and our choice for a neutral state. ■

NOTES

[1] Kuyper, Abraham: 'Ons Program'. Amsterdam, J.H. Kruyt, 1879. English translation: Our Program. A Christian Political Manifesto. Translated by van Dyke, Harry. Bellingham, Lexham, 2015.

[2] The best introduction to Kuyper in English is: Bratt, James D.: Abraham Kuyper: Modern Calvinist. Christian Democrat. Grand Rapids, Michigan, Eerdmans, 2013.

[3] van Egmond, Peter J.: "A Confession without Pretence": Text and Context of Pelagius' Defence of 417 AD, diss. VU Amsterdam, s.l.: s.n., 2013.

[4] van den Brink, G. - van der Kooi, c.: Christian Dogmatics: An Introduction. Transl. by Bruinsma, Reinder - Bratt, James D. Zoetermeer, Boekencentrum, 2017, 276.

[5] Van den Brink, G. - Van der Kooi, c.: Christelijke Dogmatiek, 631; Matthias Zeindler: Erwählung: Gottes Weg in der Welt. Zürich, Theologischer Verlag, 2009, 35.

[6] Hobbes, Thomas: Leviathan, Or, The Matter, Form, and Power of a Common-wealth Ecclesiastical and Civil. London, Andrew Crooke, 1651.

[7] Hobbes op. cit. 87.

[8] Hobbes op. cit. 249.

[9] Hobbes op. cit. 66.

[10] Böhmer, Just Henning: lus Ecclesiasticum Protestantium Usum Hodiernum Iuris Canonici. Tom. 5., Praeloquium De Systemate Universi Iuris Canonici §XI1, 17; Schlaich, Klaus: Kollegialtheorie: Kirche, Recht und Staat in der Aufklärung (Jus Ecclesiasticum 8). München, Claudius Verlag, 1969.

[11] Pfaff, Christoph Matthäeus: Origines iuris ecclesiastici. Tübingen, Schramm, 1756; Pfaff, Christoph Matthäeus: Akademische Reden über das sowohl allgemeine als auch Teutsche Protestantische Kirchen-recht. Tübingen, Sigmund, 1742.

[12] Schlaich op. cit. 14.

[13] Schlaich op. cit. 89.

[14] Bouwman, Harm: Gereformeerd kerkrecht, vol. 1. Kampen, Kok, 1928, 13.; Sehling, Emil: Geschichte der Protestantischen Kirchenverfassung, 2[e] Aufl. Leipzig-Berlin, Druck und Verlag von B.G. Teubner, 1914, 38.

[15] Stahl, Friederich Julius: Die lutherische Kirche und die Union: Eine wissenschaftliche Erörterung der Zeitfrage. Berlin, Wilhelm Hertz, 1859, 266.; Schlaich op. cit. 23.

[16] Coenen, Lothar - Beyreuther, Erich - Bietenhard, Hans (eds.): Theologisches Begriffslexikon zum Neuen Testament. Band II/1, 2[nd] . ed. Wuppertal, Theologischer Verlag Rolf Brockhaus, 1970, 784-799; Arndt, William F. - Gingrich, F. Wilburg: A Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament and Other Early Christian Literature. 2nd ed. Chicago-London, The University of Chicago Press, 1979, 240-241.

[17] Vree, Jasper - Zwaan, Johan: Abraham Kuyper's Commentatio (1860): The Young Kuyper about Calvin, a Lasco and the Church. Leiden-Boston, Brill, 2005, 13.

[18] Durham Jr., W. Cole: Perspectives on Religious Liberty: A Comparative Framework. In: Witte, John - van der Vyver, Johan D. (eds.): Religious Human Rights in Global Perspective: Legal Perspectives. Part 2. The Hague-Boston-London, Martinus Nijhoff, 1996, 1-44.; Cole Durham Jr. published an earlier and less developed version of this article in: Garlicki, Leszek Lech (ed.): First Amendment Freedoms and Constitution Writing in Poland. Warsaw, s.n., 1994, 61-72.

[19] Huussen Jr., A. H. - Wedman, H. J.: Politieke en sociaal-culturele aspecten van de emancipatie der Joden in de republiek der Verenigde Nederlanden. Documentatieblad Werkgroep Achttiende Eeuw, 1981, 51/52, 208-213.

[20] See for the history of the Jews in the Republic, and prior to 1848: Blom, Hans- Wertheim, David- Berg, Hetty- Wallet, Bart (eds.): Geschiedenis van de Joden in Nederland. Amsterdam, Balans, 2017, 55-232.

[21] Vis, Jurjen - Janse, Wim (eds.): Staf en storm. Het herstel van de bisschoppelijke hiërarchie in Nederland in 1853: actie en reactie. Hilversum, Verloren, 2002.

[22] See: Harinck, George: Een leefbare oplossing. Katholieke en protestantse tradities en de scheiding van kerk en staat. In: ten Hooven, Marcel- de Wit, Theo (eds.): Ongewenste goden: De publieke rol van religie in Nederland. Amsterdam, SUN, 2006, 111-112.

[23] See: Krijger, Tom-Eric Marinus: A Second Reformation? Liberal Protestantism in Dutch Religious, Social and Political Life, 1870-1940. Dissertation, Groningen, 2017.

[24] Hooker, Mark T.: Freedom of Education: The Dutch Political Battle for State Funding of all Schools both Public and Private (1801-1920). h.n., Llyfrawr, 2009.

[25] Kuyper op. cit. 64.

[26] Harinck, George: Abraham Kuyper's Vision of a Plural Society as a Christian Answer to Secularization and Intolerance. In: Karpov, Vyacheslav - Svensson, Manfred (eds.): Secularization, Desecularization, and Toleration - Cross-Disciplinary Challenges to a Modern Myth. London, Palgrave MacMillan, 2020, 115-133.

[27] De Standaard, 18 June 1874.

[28] Knippenberg, Hans: Assimilating Jews In Dutch Nation-Building: The Missing 'Pillar'. Tijdschrift voor Economische en Sociale Geografie, 2002/93, 193.

[29] Knippenberg op cit. 202-203.

[30] Harinck, George: Neo-Calvinism and Democracy: An Overview from the Mid-Nineteenth Century till the Second World War. In: John Bowlin (ed.): The Kuyper Center Review, Volume Four: Calvinism and Democracy. Grand Rapids-Cambridge, Eerdmans, 2014, 1-20.

[31] Blom op cit. 242.

[32] In: De Standaard, 4 April 1872, Kuyper wrote that 'liberalists' 'in naam der vrijheid, de vrijheid van conscientie weer durven aanranden'.

[33] Houkes, Annemarie: Christelijke Vaderlanders: Godsdienst, burgerschap en de Nederlandse natie 1850-1900. Amsterdam, Wereldbibliotheek, 2009, 218-230.

[34] Jeroen Koch: Abraham Kuyper: Een biografie. Amsterdam, Boom, 2006, 178.

[35] Kuyper, Abraham: Liberalisten en Joden. Amsterdam, J.H. Kruyt, 1878, 6.: "Diep beschaamd over eigen vroegere ongerechtigheid, heeft toen de Christenheid schier in alle landen deze beteekenisvolle vrucht der revolutie als een harer uitnemendste consequentiën toegejuicht."

[36] Kuyper op. cit. 14: "Joden in alle hoeken en uiteinden van ons werelddeel [zijn] nog steeds in veel strenger zin een natie gebleven, dan eenig Europeesch volk ooit een natie was."

[37] Kuyper op. cit. 14-15.

[38] Kuyper op. cit. 26: 'Eenmaal aan den Christus ontzonken, moeten natiën, die zijn zegen eenmaal indronken, oneindig dieper wegzinken dan Israël, dat in zijn tegenwoordige verschijning den zegen van dien Christus nooit heeft gekend.'

[39] Het Algemeen Handelsblad, referred to in Kuyper op. cit. 17-18.

[40] Kuyper op. cit. 23, 33.

[41] In 'Ons program' he did nowhere use the word 'guest' for Jews, except in this series.

[42] Kuyper op. cit. 14, 22.

[43] Kuyper op. cit. 28.; Knippenberg op. cit. 195, 197.

[44] Kuyper op. cit. 32.

Lábjegyzetek:

[1] The Author is Associate Professor, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam; Theologische Universiteit Kampen.

[2] The Author is Professor, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam; Theologische Universiteit Kampen, Director, The Neo-Calvinism Research Institute, Kampen.