István Hoffman[1]: The Structure of the Personal Social Services in Hungary (Annales, 2017., 83-100. o.)

https://doi.org/10.56749/annales.elteajk.2017.lvi.6.83

Abstract

The article reviews the changes in the service provision system, especially in the structure of Hungarian social care. First, the theoretical and international backgrounds of the topic are shown. Second, the article presents the transformation of the Hungarian social care over the last decades. Here, a trend towards concentration and centralisation can be observed. Third, the mixed nature of the Hungarian municipal social care system is analysed, a system that has been strongly centralised over the last five years. The effects of centralisation are analysed as well; the article shows that the changes in funding have the most significant impact on the spatial structure of service provision.

Keywords: social care, municipal social care, funding, centralisation, concentration, spatial structure

I. Introduction: hypothesis and research method

In Hungary, the system of social care has changed radically in the last decade. The system was originally based on a strong but fragmented municipal system. The main goal of the transformation of the system in the last decade has been to maintain the grassroots model of Hungarian social care. Second, the reforms have tried to minimise the negative effects of economies of scale. This article will examine the regulatory methods and the related budgetary support system applied to this aim. Thus, while the primary method of the research is jurisprudential, the effects of regulation and the practical outcome of the new support system will also be analysed as well.

The paper will first review the main models of social care. This comparative review is very useful, because different administrative systems and paradigms have different concepts of the spatial structure of these services. After a short comparative review, the jurisprudential and budgetary analysis will then show the transformation

- 83/84 -

of the social care system and the paradigm-shift in these services after 2011/12. Finally, this article will examine the effects and impacts of the partly centralised model.

II. Social care and local governments

The role of the municipalities in the field of personal social services is significant in welfare states. Whether social care is partly or fully based on these local entities, several models have evolved.[1]

The models can be characterised on different aspects, because these systems are impacted by the welfare model of the given country, by the municipal model and by the country's spatial structure as well.[2]

The characterisation of these models in my analysis is based mainly on the role of the municipalities and on the spatial structure of service provision. In this way, decentralised and centralised models can be distinguished.

1. Decentralised model

The decentralised model is based on the main service provision role of the municipalities. In this model, the local governments are mainly responsible for the social care services; the agencies of central government have just limited tasks.

Two main types of the decentralised model can be distinguished: the first one is the local community-centred model, which is based on the prominent role of the 1st tier municipalities, and the regional centred model, in which the most important services are organised and provided by the regional (2nd tier government). Inter-municipal cooperation is mainly a correctional tool for the fragmented spatial structure and is very important in the community-centred model.

a) Local community-centred model

Social care is primarily organised by the local (1st tier) municipalities in the countries where this model dominates. These local social services mainly provide basic social care (e.g. home care, catering). In this model, the role of the regional (2nd tier) municipalities is just additional, they organise services which cannot be provided by the local communities (especially several special, residential, in-patient social care services).

- 84/85 -

Although this type of service provision is based on the dominant role of the local (1st tier) municipalities, two subtypes result from the different spatial and municipal system of the given countries.

Large, concentrated municipalities with broad service provision responsibilities: the Nordic model - The Nordic (Scandinavian) countries can be classified as examples of the local community-based model. In Sweden, the Social Services Act[3] makes clear that only the 1st tier local governments are responsible for the provision of social services.[4] Finland developed a model similar to the Swedish one.[5]

Denmark and Norway have a mixed model, because the communities (1st tier municipalities) are responsible for basic social care and the majority of the residential (in-patient) social care services, but regional (2nd tier) municipalities have relevant competences because the residential services of child protection and helping alcohol and drug addicts are provided by these municipalities.

Community-centred model with the additional responsibilities of the regional municipalities and inter-municipal cooperation - The majority of European countries follow this model and so countries with different municipal and welfare models belongs to this. In these states - considering their mainly Bismarckian welfare model - the social services provided by the municipalities are typically means-tested and these services have a complementary role.

Some countries with a Latin (French) local government type can be included in this model as well, for example Italy and Belgium. In Italy, the settlement-level municipalities (comune) are primarily responsible for the provision of social services, including elderly care, child and youth protection and helping people with a disability. The regional municipalities (regione) have a regulatory and coordinating role in the field of these services. Because of the wide range of municipal tasks, Italian public law developed legal institutions for minimising the negative effects of economy of scale problems. These legal institutions are typically - exceptionally compulsory - inter-municipal associations. This was strengthened by the reform of the leggeDelrio (2014), by which establishing different types of inter-municipal service provider associations has been encouraged.[6]

- 85/86 -

In Belgium, the community governments are primarily responsible for the provision of social care. The municipal social services are organised by the public centres for social welfare (openbare centra voor maatschapelijk welzijn/centrespublics d'aide sociale), regardless of the region to which the municipalities belong.[7] The centres are professionally independent from the municipalities, but their budgets are approved by the local councils.[8] Although the number of Belgian local municipalities (gemeente/commune) was significantly reduced during the 1970s, the inter-municipal associations have been institutionalised by Belgian administrative law in order to correct for the disparity in size between the settlements. The Belgian regions, which can be considered as member states of a federation, are responsible for the higher-cost services.[9]

In Slovakia, the local municipalities are responsible for the non-residential (basic) social care and the regional municipalities, the districts (kraj), are responsible for residential social services and for the services of child protection.[10] The Czech Republic has chosen a similar model. Poland has a special position among the Visegrád countries considering its larger area and greater population. The Polish local government system is a three-tier system. The 1st tier municipalities (communities - gminy) are responsible for non-residential social care and child protection services. The provision of expensive residential services belongs to the competences of the 2nd tier municipalities, to the districts (powiaty). The Voivodships, as 3rd tier municipalities, do not have any competences in the field of social services. The inter-municipal associations do not have significant role in the Polish municipal system because of the concentration of the municipalities.[11]

b) Regional municipality-centred model

The social care system of the United Kingdom can be characterised as a regional municipality-centred one. The - professionally independent - local social authorities of the county councils and unitary councils are responsible for the provision of social

- 86/87 -

services.[12] The reforms encouraged by the New Public Management in the 1980s and 1990s altered the role of the local governments significantly: they became organisers instead of being providers.[13] The private sector has played an increasingly important role in the change, as compulsory competitive tendering (CCT) was introduced for the selection of social care providers. As the result of the reforms, local governments became the 'managers' of the services instead of their providers.[14] The reforms of the Labour Party Government of the Millennium did not significantly alter this model.[15]

2. Centralised model

Germany can be considered as the prime example of the centralised model. Article 3 of Book XII on personal social assistance of the Social Code (Sozialgesetzbuch - SGB) states that personal social assistance is provided by the designated municipal bodies and the designated administrative bodies above the local tier. As a principle, the local administrative bodies responsible for the social care are the German Landkreise (the county-like districts of Germany,[16] and the unitary councils (kreisfreie Städte) - if the provincial social law (Landessozialrecht) does not make an exception.[17] The provinces (Länder) can designate the bodies responsible for regional (überörtlich) services. The provinces (Bundesländer) are empowered by Article 99 of Book XII of the SGB to designate the local municipalities (Gemeinde) and the - typically obligatory - inter-municipal associations (Gemeindeverbände) to provide several basic personal social services. Book XII also determines that - if a provincial act did not have another provision - the administrative level above the German counties (Kreise) (the so-called überörtlich level) is responsible for care for disabled and blind people, for nursing and care services and for the statutory defined social services in the event of crises.[18] As such, the provinces, the Member States of the German Federation, have the most important role in the field of personal social services.[19]

- 87/88 -

Bavaria has chosen a specific solution, which - as the largest German province -has not developed a two, but a three-tier local government system: the seven districts (Bezirke) are self-government units.[20] In this way, social assistance tasks have been shared between the under-intermediate level counties (Kreis) and unitary councils (kreisfreie Städte) and the upper-intermediate level district (Bezirke) municipalities.

It is shown by the short international outlook that the local level has very important role in the provision of personal social services. Even the local municipalities of the countries operating the centralised model could have responsibilities in this field. It is clear that the spatial structure of these welfare services are deeply impacted by the spatial structure of the given country, especially the spatial structure of the municipalities.

After the review of the main models of the spatial structure of personal social services, the Hungarian system will be reviewed, but first the frameworks of the Hungarian system will be analysed.

III. Social care in Hungary

This part of my chapter is based on a jurisprudential analysis. First, I will review the framework of the Hungarian social care system, especially the changes and the role of the municipalities in the Hungarian public service provision system. After that I shall briefly review the changes to the social care services in Hungary and finally, I will summarise the reform of the personal social service system. This analysis shows the main features of the recent spatial structure system.

1. Hungary: a country with a fragmented municipal system

Hungary has a fragmented spatial structure. The majority of Hungarian municipalities had fewer than 1,000 inhabitants in 2010.[21]

- 88/89 -

Table 1. Population of the Hungarian municipalities (1990-2010)[22]

| Inhabitants | Year | ||

| 1990 | 2000 | 2010 | |

| 0-499 | 965 | 1,033 | 1,086 |

| 500-999 | 709 | 688 | 672 |

| 1,000-1,999 | 646 | 657 | 635 |

| 2,000-4,999 | 479 | 483 | 482 |

| 5,000-9,999 | 130 | 138 | 133 |

| 10,000-19,999 | 80 | 76 | 83 |

| 20,000-49,999 | 40 | 39 | 41 |

| 50,000-99,999 | 12 | 12 | 11 |

| 100,000- | 9 | 9 | 9 |

| Source | 3,070 | 3,135 | 3,152 |

The provision of local public services - included personal social services - in Hungary has been based on this condition, and (inter-communal) cooperation has a significant role.

a) Personal social services before 1945

In the 19th century, when the modern Hungarian public administration evolved, the social services had only limited significance. Only the framework of services for the poor and child protection were established. This fragmented and residual system was based on the communities, which had limited self-governance under the supervision of the county municipalities.[23]

b) Social services of the Soviet-type administration

After World War II, a Soviet administrative system evolved in Hungary and the administration radically changed after 1950. The self-governance of the communities, towns and counties was terminated, and the former intercommunal associations were liquidated[24] as well. Social administration was an empty space in Hungarian public administration. First, social benefits were 'taboo' in the Soviet-type system, because it was

- 89/90 -

an axiom of the Communist regime that poverty was liquidated by Socialism. As such, only personal social services and social insurance remained public administration tasks.[25] This model changed after the reforms of 1968; the significance of personal social services increased. Although merging communities was an important element of the public service provision reforms, intercommunal associations were reborn. A dual system evolved: the local councils (1st tier) were responsible for basic social care and the county councils (2nd tier) were responsible for residential (in-patient) social care. The main elements of this system were large institutions, by which residential social care was primarily provided. During the 1980s, the frameworks of the social administration were stabilised.

c) Democratic Transition and the rebirth of the social administration system

In 1990 a new, local government system was established by the Amendment of the Constitution and by Act LXV of 1990 on the Local Self-Governments (hereinafter: Ötv.). This system was a two-tier but local-level centred system. The first tier was the local (community) level. According to the Ötv., villages, large villages, towns, county towns and Budapest as the capital city were considered local-level governments (municipalities). The second tier was the county level. The county local governments had an intermediate service-provider role, but county-level service delivery could largely be overtaken by the municipalities. The local-centred nature of the Hungarian local government system was strengthened by the system of voluntary inter-municipal associations.[26]

In 1993, Act III of 1993 on Social Administration and Social Benefit was passed. Municipal social benefits and personal social services were regulated by this act. A new, model, centred at local level, evolved. The local municipalities - the communities and the towns - were responsible for basic social services and the counties and the towns with county rank were responsible for residential social care. The local municipalities could take over the provision of residential social care. The main provider was thus the local level and the counties - as regional municipalities - had practically supplementary tasks: residential social care was provided by them if the local municipalities could not organise the provision of these services.[27]

d) Institutionalisation and dysfunctional phenomena

Although the act on social administration and benefits was passed in 1993, the institutionalisation of the new service system required years. As I have mentioned earlier, the provision of personal social services was based on the great pre-1990 institutions.[28] As such, the system of local basic services evolved in several steps.

- 90/91 -

The period of institutionalising these services practically ended around the Millennium, therefore, after 2000, the dysfunctional phenomena of the new system could be analysed. These dysfunctions were connected with the general dysfunctions of the new municipal system. After 1990, a local tier-centred and fragmented local government system evolved in Hungary, according to which model the major responsibilities belonged to the communities and towns. This fragmented spatial structure was strengthened by democratic changes, as a counterpart to former Communist times, when compulsory inter-municipal associations (the common village councils presented above) addressed inefficiency problems due to lack of scale. This compulsory form was unpopular among Hungarian municipalities, so it disappeared with the democratic changes, giving an opportunity to a trend towards disintegration in the transition period.[29]

Attempts to solve this fragmentation and the related size inefficiency problem by inter-municipal cooperation were based on voluntary cooperation. The new types of associations could not stop the disintegration because of their purely voluntary nature and the poor financial support provided by the central budget. As a result, the number of service provider associations was only 120 in 1992. The joined municipal administrations decreased in these years: the number of common municipal clerks was 529 in 1991, 499 in 1994, and only 260 administrative inter-municipal associations existed by 1994.[30] The lack of intercommunal cooperation, the fragmented spatial structure, and the weak, subsidiary intermediate level public service provider role of the county local governments resulted in significant service delivery dysfunctions. The local self-governments - especially the small villages, which were the majority of Hungarian municipalities - were not unable to perform a significant part of their municipal tasks. In 2005, the most basic social services - social catering and social home care - were not performed by 725 municipalities, by almost a quarter of the municipalities in Hungary.[31] Such municipal social services were mandatory tasks, so they should have been performed and their performance was supported by the central budget. Their share of central grants was very limited; in 2006, 50.4% of municipal expenditure on basic social services was financed by central grants,[32] so the small communities, which had only limited own revenues could barely perform their tasks.

Although there were service deficiencies in the field of basic social services, residential social care was relatively well organised as the heritage of the former service provision system. The service deficiencies in basic care resulted in a dysfunctional

- 91/92 -

phenomenon: people who required basic care were provided with residential care because basic home-based social care was not available for them.[33] Another problematic element was the care need test: this test was generally performed by the institutions, by the providers, therefore it was not an independent one and the remedies against the decisions were limited.[34]

A consensus therefore evolved among the Hungarian experts by the Millennium: reforms were required.

2. The social care reforms

a) The first step: new forms of municipal cooperation (2005-2007)

The first step of the reforms was connected to municipal reforms. First, at the end of the 1990s, the institutions of the various inter-municipal associations were regulated, and new, additional state subsidies were introduced to accelerate the formation of voluntary inter-municipal associations after 1997.[35] As a result of these changes, the number of inter-municipal associations radically increased.[36]

Table 2. Number of inter-municipal associations responsible for public service provision between 1992 and 2005

| Year | Number of the inter-municipal associations responsible for public service provision |

| 1992 | 120 |

| 1994 | 116 |

| 1997 | 489 |

| 1998 | 748 |

| 1999 | 880 |

| 2003 | 1,274 |

| 2005 | 1,586 |

Source: Belügyminisztérium, A helyi önkormányzati rendszer tizenöt éve. 1990-2005. 15 év a magyar demokrácia szolgálatában (BM Duna Palota és Kiadó, Budapest, 2005) 205.

- 92/93 -

In 2004, the legislator introduced a new type of inter-municipal association - the multipurpose micro-regional association, based on the French inter-municipal association form 'SIVOM'. The central government significantly supported service delivery through associations: in 2004, the share of the special subsidies for them was 1.19% of the whole central government subsidies for local governments, and in 2011 it already reached 2.91%.[37]

b) Partial reforms of personal social services

In 2007 a partial social service reform was passed by the Hungarian Parliament. The reform act amended the act on social administration and benefits. The decentralised, local level-centred model remained but the partial reform tried to solve several problematic elements of the service delivery system. The funding of the services was partly transferred: the share of central funding in the field of the basic social services was increased, which resulted in a rapid increase in the number of recipients of basic social services. For example, in 2007, 45 989 persons were received social home care, but 48 120 persons benefited in 2008 and 63 392 in 2009.[38] The service delivery tasks of the inter-municipal associations were encouraged by the funding reform as well. The share of the grant for joint service provision was increased.

The care need test was amended as well. A new model was established: the care need test was performed by an independent commission which was organised by the chief public servants of the town municipalities (by the town clerks - jegyző). The detailed conditions of the test were regulated by a ministerial decree and that tried to make the test objective.[39]

c) The effects of the constitutional and municipal reforms. The age of centralisation after 2011

The former municipal regulation was changed radically, the former decentralised model was transformed by the new Constitution - the Fundamental Law of Hungary - and by the new Municipal Code - Act CLXXXIX of 2011 on the Local Self-Governments of Hungary (hereinafter Mötv.). The local service performance role of the municipalities has been weakened, and the scope of their tasks has become narrower. Due to this remodelling, the concentration of municipal local services has partially lost its significance. The regulation of voluntary tasks has been changed as well. A simple model has been chosen by the central government to reduce the fragmentation of the public service system: the most problematic service provisions were centralized and now they are performed by the local agencies of central government. In this way, local government

- 93/94 -

tasks have been significantly reduced, which is reflected in the size of local government expenditure: before the reforms, in 2010, the total local government expenditure was 12.8% of the GDP, while in 2016 it was only 8.1%.[40]

Table 3. Total local government expenditure in Hungary (as a % of GDP) 2002-2015

| Year | 2002 | 2006 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 |

| Total local government expenditure (as a % of GDP) | 12.9% | 13.0% | 12.8% | 11.6% | 9.4% | 7.6% | 7.9% | 8.1% |

Source: Eurostat, Total Government Expenditures, http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/tgm/refreshTableAction.do;jsessionid=9ea7d07e30dcd247b519937c4d909261df02fe3369b7.e34MbxeSahmMa40LbNiMbxaMchmTe0? tab=table&plugin=1&pcode=tec00023&language=en (Last accessed: 17 June 2017)

The main tasks of education, inpatient care, residential social care and residential child protection are performed by the agencies of the central government.[41] The county municipalities lost their tasks in the field of social services (included the services of child protection). Although the basic social services are provided by the local level municipalities and several forms of residential care for the elderly can be performed by these communities, the majority of the provision of residential care was nationalised. The majority of the providers of residential social care and the child protection institutes are thus maintained by the county agencies of the Directorate General of Social and Child Protection, which is an agency of the Ministry of Human Capacities.[42]

The transformation of the role of the central administration can be observed in the change of total expenditure of the budgetary chapter - practically the sectors -directed by the Ministry of Human (formerly National) Capacities.[43]

- 94/95 -

Table 4. Total expenditure (in million HUF) of the budgetary chapter directed by the Ministry of Human Capacities

| Year | Total expenditure (in million HUF) of the budgetary chapter directed by the Ministry of Human (formerly National) Resources |

| 2011 | 1,535,370.6 |

| 2012 | 1,949,650.5 |

| 2013 | 2,700,363.9 |

| 2014 | 2,895,624.8 |

| 2015 | 3,049,902.2 |

| 2016 | 3,011,947.7 |

Source: Act CLXIX of 2010 on the budget of the Republic of Hungary, Act CLXXXVIII of 2011, Act CCIV of 2012, Act CCXXX of 2013, Act C of 2014 and Act C of 2016 on the central budget of Hungary. Inflation rate was 3.9% in 2011, 5.7% in 2012, 1.7% in 2013, and -0.9% in 2014 based on the data of the Hungarian Central Statistical Office.

Although the central budget support for the municipalities has been reduced, in 2012, the funding of basic social care was increased, especially the funding of social home care. The funding of municipal social services was strengthened by the new municipal finance model, which was based on actual expenses.

d) Reform in recent years

The last reform of the Hungarian municipal social system was in 2015. The reform was focused primarily on social benefits. In the new model, the central budget support for municipal social cash benefits was greatly reduced; several municipal cash benefits were nationalised. The most important transformation of the reforms was the amendment of the financing of social benefits and services. In the new model, most of these benefits and services are mainly financed by the local business tax. State aid is only a supplementary source for funding these services. As such, the basic services are, in practice, real municipal services and the central government has only a compensative role.

The regulation of the social services in Hungary changed significantly over the last decade. The changes were connected to municipal and public service reforms. Although the majority of residential social care was nationalised, social services have remained the most important municipal ones.

These changes impacted the spatial structure of the Hungarian social service system as well. In the next point I will review this impact.

- 95/96 -

IV. Spatial structure of personal social services in Hungary

1. Hypothesis

As I have mentioned earlier, the reforms in the last decade tried to solve the economy of scale problem of Hungarian personal social services, which were based on the fragmentation of the Hungarian municipal system. Because of this, the provision of the high cost services, personal services, was nationalised.

Second, the new provision of the basic services was encouraged by the new financing methods, especially in rural areas. The service provision of the smaller municipalities has been supported by increased financing, support from inter-municipal cooperation and the new block grant.

Two hypotheses could thus be formulated. The first hypothesis is that access to social services has been improved by the new financial mechanism. The second hypothesis is based on the strong nationalisation of residential care. I therefore postulate that the spatial structure of residential social services has been most impacted by the nationalisation.

2. Analysis and findings

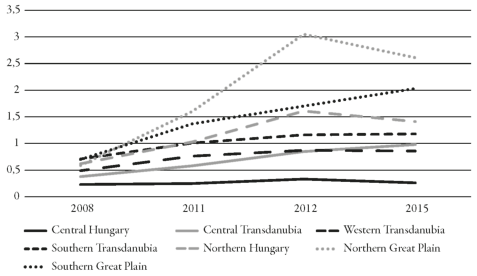

To examine these hypotheses, I analysed the number of recipients and the share of recipients of two basic social services (social meals and social home care). As I mentioned earlier, they were not provided by almost a quarter of Hungarian communities in 2005. If we look at the number of recipients of social catering it could be observed that the number of the recipients has increased significantly between 2008 and 2011, when the funding reforms occurred. The share of the recipients decreased modestly after 2012, when the central budget support decreased and the municipal own revenues were preferred. Similar changes occurred in the number and share of the recipients of the social home care.[44]

If we look at the regional data, it can be observed that the number and share of recipients increased more in all regions but the most significant growth can be observed in those regions where the spatial structure is not very fragmented and medium-sized villages (with 2,000 to 4,000 inhabitants) are dominant.[45] Thus, primarily, their

- 96/97 -

access to these services has been strengthened. The modest decrease in the number of recipients shows that service provision is sensitive to any decrease in central budget support.

Table 5. Recipients of social catering in Hungary (as a share of the population, in %)

| NUTS 2 region / Year | Central Hungary | Central Trans- danubia | Western Trans- danubia | Southern Trans- danubia | Northern Hungary | Northern Great Plain | Southern Great Plain | Hungary |

| 2008 | 0.59 | 0.9 | 1.2 | 1.43 | 1.66 | 1.38 | 1.13 | 1.08 |

| 2011 | 0.72 | 1.35 | 1.57 | 1.98 | 2.15 | 2.18 | 2.03 | 1.55 |

| 2012 | 0.79 | 1.34 | 1.51 | 1.93 | 2.28 | 2.53 | 2.28 | 1.67 |

| 2015 | 0.63 | 1.31 | 1.49 | 1.89 | 2.41 | 2.89 | 2.76 | 1.73 |

Source: Központi Statisztikai Hivatal, Éves társadalomstatisztikai adatok 2000-2016, http://www.ksh.hu/docs/hun/xstadat/xstadat_eves/i_fsi002b.html?down=644 (Last accessed: 17 June 2017)

Table 6. Number of recipients of social home care in NUTS-2 regions of Hungary

| Year | ||||

| Regions | 2008 | 2011 | 2012 | 2015 |

| Central Hungary | 6,683 | 7,548 | 9,914 | 7,753 |

| Central Transdanubia | 4,144 | 6,426 | 9,260 | 10,397 |

| Western Transdanubia | 4,897 | 7,598 | 8,525 | 8,485 |

| Southern Transdanubia | 6,779 | 9,508 | 10,753 | 10,600 |

| Northern Hungary | 7,490 | 12,252 | 19,312 | 16,568 |

| Northern Great Plain | 8,746 | 23,716 | 45,537 | 38,657 |

| Southern Great Plain | 9,181 | 17,893 | 21,980 | 25,921 |

Source: KSH, Éves társadalomstatisztikai adatok 2000-2016.

- 97/98 -

Figure 1. Social home care - share of recipients (in % of the population)

Source: KSH, Éves társadalomstatisztikai adatok 2000-2016.

Hence, hypothesis 2 has been validated by the statistical data: the provision of services is very sensitive to financing, especially to central budget support. The spatial structure of the services refers the degree of need better after the reforms in 2008. The system was impacted by the municipal reform to a limited extent; the preference for own revenues in particular has had a modest effect on the structure of the basic services.

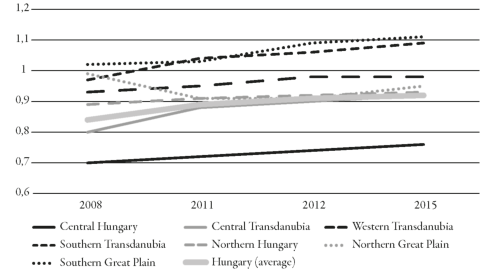

If we look at residential social care, only a modest change can be observed. Although the service system became moderately balanced, the regional differences partially decreased, but the whole system has not been transformed.[46]

- 98/99 -

Table 7. Number of recipients of residential social care

| Year | ||||

| NUTS - 2 regions | 2008 | 2011 | 2012 | 2015 |

| Central Hungary | 20,640 | 21,417 | 21,847 | 22,630 |

| Central Transdanubia | 883 | 9,607 | 9,770 | 9,836 |

| Western Transdanubia | 9,304 | 9,477 | 9,721 | 9,630 |

| Southern Transdanubia | 9,201 | 9,818 | 9,853 | 9,858 |

| Northern Hungary | 10,239 | 10,904 | 11,111 | 10,797 |

| Northern Great Plain | 14,786 | 13,542 | 13,692 | 14,077 |

| Southern Great Plain | 13,441 | 14,121 | 14,106 | 14,152 |

Source: KSH, Éves társadalomstatisztikai adatok 2000-2016.

Figure 2. Share of the recipients of residential social care (in % of the population)

Source: KSH, Éves társadalomstatisztikai adatok 2000-2016.

- 99/100 -

Thus hypothesis 1 has been just partially confirmed: nationalisation had just a modest impact on the residential social care system. It can be observed that the service provision is strongly impacted by the transformation of its financing, and then the transformation of the organisation and management of these services.

V. Conclusions

If we look at the structure of Hungarian personal social services, it could be stated that the community (1st tier municipality) centred system has remained, although the majority of residential care service providers were nationalised after 2012. The main actors in the system are the local municipalities. The role of the municipal own revenues increased in the funding of the social care because of the reforms after 2015.

Although the reason for the nationalisation of residential care was to balance the unequal and fragmented service provision system, this transformation impacted the system of social services only moderately. Tis effect was far more limited that had been expected by the experts. Although the system became a little more balanced, the former inequalities and fragmentation have remained.

If we look at the Hungarian reforms, it can be observed that the most effective reforms are those on funding; the organisational reforms have just limited effect and impact. ■

NOTES

[1] Lőrincz L., A közigazgatás alapintézményei (HVG-ORAC, Budapest, 2005) 191-194.

[2] Hoffman I., A személyes jellegű szociális szolgáltatások igazgatása, in Horváth, T. M. and Bartha, I. (eds), Közszolgáltatások megszervezése és politikái. Merre tartanak? (Dialóg Campus, Budapest-Pécs, 2016, 329-342) 330-332.

[3] SFS (Social Services Act) 2001: 453.

[4] S. Strönholm, An introduction to Swedish law (Norstedts, Stockholm, 1981) 93; S. Thakur et al., Sweden's welfare state. Can the bumblebee keep flying? (International Monetary Found, Washington D. C., 2003) 8.

[5] H. Niemelä and K. Salminen, Social security in Finland (Finnish Centre for Pensions, Helsinki, 2006) 17-18.

[6] L. Vandelli, Citta metropolitane, province, unioni, e fusioni di communi. La legge Delrio, 7aprile 2014, n. 56 commentata comma per comma (Maggioli, Santarcangelo di Romagna, 2014) 125-145.

[7] H. Bocken and W. de Bondt, Introduction to Belgian law (Kluwer Law International, The Hague, 2001) 70.

[8] Y. Aerts and H. Siegmund, Belgium, in H. G. Wehling (ed.), Kommunalpolitik in Europa (Verlag V. Kohlhammer, Berlin-Stuttgart-Köln, 1994, 102-114) 110.

[9] Bocken and de Bondt, Introduction to Belgian law, 70-71.

[10] V. Nižňanský, Verejná správá na Slovensku (Government of Slovakia, Bratislava, 2005) 56; L. Malikova, Regionalization of Governance: Testing the Capacity Reform, in H. Baldersheim and J. Batora (eds), The Governance of Small States in Turbulent Times: The Exemplary Cases of Norway and Slovakia (Barbara Budrich Publishers, Opladen, 2012, 208-228) 210, https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvdf01dj.14

[11] H. Wollmann and T. Lankina, Local Government in Poland and Hungary: from post-communist reforms towards EU-accession, in H. Baldersheim et al. (eds), Local Democracy in Post-Communist Europe (Leske + Budrich, Opladen, 2003, 91-122) 106, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-663-10677-7_4

[12] A. Arden, J. Manning and S. Collins, Local Government Constitutional and Administrative Law (Sweet & Maxwell, London, 1999) 103-104.

[13] B. Jones and K. Thompson, Administrative Law in the United Kingdom, in R. Seerden and F. Stroink (eds), Administrative Law of the European Union, Its Member States and the United States. A Comparative Analysis (Intersentia, Antwerpen-Groningen, 2007, 199-258) 232.

[14] D. Wilson and C. Game, Local Government in the United Kingdom (Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke - New York, 2011[5]) 135-136.

[15] J. Healy, The Care of Elder People: Australia and the United Kingdom, (2002) 36 (1) Social Policy and Administration, (1-19) 6-8, https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9515.00266

[16] U. Steiner (Hrsg.): Besonderes Verwaltungsrecht (C. F. Müller, Heidelberg, 2006) 147-148.

[17] R. Waltermann, Sozialrecht (C. F. Müller, Heidelberg, 2009) 129.

[18] E. Eichenhofer, Sozialrecht (Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen, 2007) 298.

[19] B. Baron von Maydell, F. Ruland and F. Becker, Sozialrechtshandbuch (Nomos, Baden-Baden, 2008[4]) 401.

[20] M. Reiners, Verwaltungsstrukturreformen in den deutschen Bundesländern. Radikale Reformen auf der Ebene der Staatlichen Mittelinstanz (VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, Wiesbaden, 2008) 154.

[21] See Table 1.

[22] E. Szigeti, A közigazgatás területi változásai, in T. M. Horváth (ed.), Kilengések. Közszolgáltatási változások (Dialóg Campus, Budapest - Pécs, 2013) 282.

[23] Hoffman I., Önkormányzati közszolgáltatások szervezése és igazgatása (ELTE Eötvös Kiadó, Budapest, 2009) 89-90.

[24] Ibid, 105-109.

[25] Krémer B., Bevezetés a szociálpolitikába (Napvilág, Budapest, 2009) 126.

[26] Verebélyi I. (ed.), Az önkormányzati rendszer magyarázata (KJK-Kerszöv, Budapest, 1999) 30-36.

[27] Velkey G., Központi állam és a helyi önkormányzatok, in Ferge Zs. (ed.), Magyar társadalom- és szociálpolitika 1990-2015 (Osiris, Budapest, 2017, 125-160) 128-133.

[28] Ibid, 126-128.

[29] Hoffman, Önkormányzati közszolgáltatások szervezése és igazgatása, 130-132.

[30] Hoffman I., A helyi önkormányzatok társulási rendszerének főbb vonásai, (2011) 4 (1) Új Magyar Közigazgatás, (24-34) 30-31.

[31] Rácz K., Szociális feladatellátás a kistelepüléseken és a többcélú kistérségi társulásokban, in Kovács K. and Somlyódyné Pfeil E. (eds), Függőben. Közszolgáltatás-szervezés a kistelepülések világában (KSZK ROP 3.1.1. Programigazgatóság, Budapest, 2008, 183-209) 191.

[32] Ibid, 189.

[33] Krémer B. and Hoffman I., Amit a SZOLID Projekt mutat. Dilemmák és nehézségek a szociális ellátások, szolgáltatások és az igazgatási reformelképzelések terén, (2005) 16 (3) Esély, (29-63) 35.

[34] Ibid, 50-51.

[35] I. Balázs, L'intercommunalité en Hongrie, in M. C. Steckel-Assouère (ed.), Regards croisés sur les mutations de l' intercommunalité (L'Harmattan, Paris, 2014, 425-435) 428.

[36] See Table 2.

[37] Hoffman, A helyi önkormányzatok társulási rendszerének főbb vonásai, 31.

[38] KSH, Éves társadalomstatisztikai adatok 2000-2016.

[39] Rácz, Szociális feladatellátás a kistelepüléseken..., 193-194.

[40] See Table 3.

[41] The main tasks of the education, inpatient care, residential social care and residential child protection are performed by these agencies. The maintenance of the state-run schools belongs to the responsibilities of the Klebelsberg Maintainer Center which is a central agency with district and county level bodies. The residential social care and children protection institutes are maintained by the county agencies of the Directorate General of the Social and Children Protection. The inpatient health care institutions are maintained by the National Healthcare Service Center. Thus the local governments are mainly responsible for the settlement operation, for the maintenance of the kindergartens, for basic social care, for basic services of child protection, and for cultural services. See I. Balázs and I. Hoffman, Can (Re)Centralization Be a Modern Governance in Rural Areas?, (2017) 13 (1) Transylvanian Review of Administrative Sciences, (5-20) 12-13, https://doi.org/10.24193/tras.2017.0001

[42] Fazekas J., Fazekas M., Hoffman I., Rozsnyai K. and Szalai É., Közigazgatási jog. Általános rész I (ELTE Eötvös Kiadó, Budapest, 20152) 269-270.

[43] See Table 4.

[44] See Table 5, 6 and Figure 1.

[45] P. Szabó and M. Farkas, Different types of regions in Central and Eastern Europe based on spatial structure analysis, in T. Černěnko, L. Sekelský and V. Szitásiová (eds), 5th Winter Seminar of Regional Science (Society for Regional Science and Policy, Bratislava, 2015, 1-13) 8-10.

[46] See Table 7 and Figure 2.

Lábjegyzetek:

[1] The Author is dr. habil. PhD, Associate Professor, ELTE University Budapest, Faculty of Law. This article was supported by the János Bolyai Research Scholarship of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences.