Attila Pintér[1]: Corporate Governance in Venture Capital Contracts - A German-Hungarian Comparative Law Study (ELTE Law, 2019/1., 145-166. o.)

I. Introduction, Methodology

1. Introduction

'At the moment, Europe has huge reservoirs of scientific talent, but a very poor record at creating start-ups. The question many investors ask is: where is the European Google?'[1]

The basis of a successful company is a good idea. However, a good idea is not enough for success because it is necessary to finance the prototype, the marketing, the salary of the employees, the machinery, etc. It is very rare for the inventor to have enough resources to finance all expenses; as a result, funding usually involves external resources. Bank finance always provides a possibility in order to satisfy these financing needs, providing the company has enough assets as security for the bank loan. At the same time, we shall not forget that even if companies in their early phases do not have such assets which would provide proper securities for banks; on the other hand, the bank loans are expensive money. Unlike bank loans, investors provide equity, which does not have to be given back, although the investor will be a shareholder in the company. Equity transactions are good for the company, since it can use the investor's money as a capital increase, and equity transactions are also good for investors, assuming the company becomes successful and the investor can sell his share at a higher price than his original investment.[2]

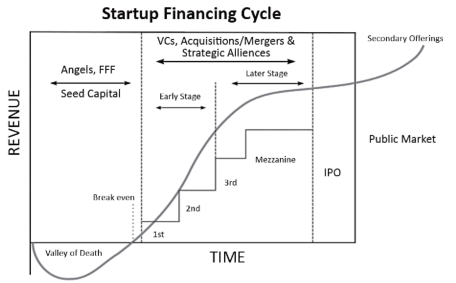

In the different phases of company development, the typical investors are always different entities. In the beginning, the company is financed by the founders and the so-called FFF, namely friends, family and fools. In the very early phase, corporate finance is so risky that there is no person who would take such risk other than the closest friends of the founders, their families or 'foolish' people. In the later phases, the risk is lower and there are some natural

- 145/146 -

persons, named business angels, who believe in the project and finance the company for a short time. When the company is more advanced and it already has sales channels, permanent buyers, a complete prototype, etc., then other investors tend to appear, such as the venture capital investors (VC) and private equity funds (PE). Finally, the company may become strong enough to be financed from the capital market as a listed company.[3]

Obviously, these phases are only the typical, average development phases of a successful company's life cycle but it can probably be accepted as a general experience. The different types of investors, in the different phases of company development are illustrated in Figure 1 below.[4]

Figure 1: Corporate finance in the different phases of the company development

2. Methodology

In this study, we analyse three German and three Hungarian investment contracts and present the corporate governance of the target company after the first venture capital investor has invested in the target company.

In this study, we seek for the person who really manages the target company. In other words, we are looking for the person who is responsible for the decisions.

- 146/147 -

In this study, the company that receives the investment amount will be named the target company, and the investor is always deemed to be a VC fund. The legal forms of the target company were always GmbH in the German contracts and Kft. in the Hungarian contracts. The members of the GmbH will be named shareholders in this study, because the German contracts also used this expression. The Hungarian Kft. has members; therefore we use this expression for the owners of the target company, although it is not a partnership. Many times, when we discuss general problems, we do not differentiate members and shareholders, and use the 'shareholders' expression, since there is no relevant difference between these expressions regarding our study, and it will be easier to understand our statements.

The first shareholders or members of the target company are named founders. We have to note that there is no big difference between VC and PE investors' investment practices in Hungary, so usually, the VC and PE funds use the same terms and conditions but we follow the international trends and this study is based on the practice of VC funds.[5]

In this study, we analyse the Hungarian and German investment laws and practice. Our research method was empirical; we analyse six investment contracts. Three Hungarian contracts were chosen from my own ten-year long investment attorney practice, while three German contracts were chosen from a remarkable German investment law firm's practice, where I worked as an observer researcher.

Our working method had two parts. The Hungarian contracts were selected from the investment contracts available at our own practice, and chose the three most typical risk capital investment contracts. The most typical contracts should be considered that contracts in which the most frequently contained the most atypical investment contractual elements. Atypical contractual elements are those terms and conditions that are not in the Hungarian Civil Code or not otherwise used in daily commercial law practice. This is what Patton calls 'purposeful sampling'.[6] on the other hand, the German contracts were examined based on the contracts, given to us by our German colleagues. We asked them to give us the three most typical risk capital investment contracts from their own practice. The method, when the researcher asks other experts to give research material for their study Webley names 'snowball sampling techniques'.[7]

We have to emphasise that our research is qualitative research; the sampling and our conclusions are not necessarily representative or objective. of course, it is not possible to conduct quantitative research into contractual practice as there is no researcher who could read every investment relevant contract. As was stated by Corbin and strauss, 'Nowadays, however, we all know that in qualitative research, objectivity is only a myth.'[8] Our only purpose with this study is to describe the investment contracts which appeared during our research and give a broad picture of the corporate governance system in these contracts.

- 147/148 -

Our research is based on inductive method, using comparative legal analysis techniques. We explain the most significant statutory laws from both legal systems and also draw some conclusions.

First of all, we introduce the mandatory law relating to the general corporate governance of the target companies in the examined agreements; later, the corporate bodies are presented in detail and finally we will draw some conclusions.

II. Corporate Governance in the Examined Contracts

First of all, we have to clarify what the definition of the corporate governance is. We accept Richard Smaldon's definition:

corporate governance is the system by which business corporations are directed and controlled. The corporate governance structure specifies the distribution of rights and responsibilities among different participants in the corporation, such as the board, managers, shareholders and other stakeholders, and spells out the rules and procedures for making decisions on corporate affairs. By doing this, it also provides the structure through which the company objectives are set, and the means of obtaining those objectives and monitoring performance.[9]

Moreover, it is also necessary to explain contractual corporate governance. Richard Smerdon defines the contractual corporate governance as follows: 'Contractual corporate governance refers to the ways and means by which individual companies can deviate from their national corporate governance standards by increasing (or reducing) the level of protection they offer to their shareholders and other stakeholders.'[10] In view of such a definition, we shall only focus on the question of the difference between the statutory law and the applied corporate governance in the examined contracts.

First of all, we introduce the structure of German and Hungarian VC contracts and later we explain how the corporate bodies were working and what power the different corporate bodies had.

1. Corporate Governance in the German Agreements

Each German investment contracts consisted of three main different types of agreement.

The first agreement is an investment agreement, which regulates the investment procedure, the amount of the investment, the tranches and KPIs.[11] The second is a shareholders' agreement which sets out the internal rules of the company's operations and the

- 148/149 -

other rights and obligations between the parties. These two are considered to be trade secret and it is not required to publish their content according to the applicable law. The third agreement is the articles of association, which is a mandatory regulated document mandatory law and qualifies as public data because it is registered in the commercial register. Besides these agreements, there were many other documents in the transactions, for instance power of attorney mandates, business plans, IP agreements and a list of shareholders, etc.

The shareholders' agreement always had two parts in the examined contracts, the corporate governance and the special rights of the investor. Therefore, in the following, we focus on the rules of the shareholders' agreement.

In each contract, there were three main corporate decision-makers:

a) Shareholders' meetings, as the supreme body of the target company.

b) Board: Each contract referred to a so-called 'other corporate body, namely the advisory board. This body makes decisions on issues that are usually within the duties of senior management's (derogating from managing directors' competencies).[12]

c) CEO: None of the shareholders' agreements has any rules for the managing director of the company (CEO), but it was regulated in the articles of association and in mandatory law. As we will see, the managing director has a general power to manage the company, except regarding the powers delegated to other corporate bodies. In fact, the shareholders' contracts all concerned the reduction of the managing director's power and enhancing the power of the general meeting and board.[13]

Finally, it is noted that none of the contracts has any rules for the supervisory board nor the auditor.

2. Corporate Governance in the Hungarian Agreements

Unlike the structure of German VC contracts, there were only two main agreements in one investment transaction in the examined Hungarian transactions: the investment agreement and the articles of association. The first one contained the investment structure, tranches, KPIs and the internal relationships regarding the company's operations and the other rights and obligations between the parties. This document was considered trade secret. The articles of association contained the rules which governed the organization and operations of the target company and which were regulated by the mandatory Hungarian corporate law. The articles of association are public data; thus it must be published upon being registering in the company register. Both of these contracts have detailed rules regarding corporate governance.

- 149/150 -

We found the following corporate governance systems in the examined Hungarian contracts:

a) Members' meeting: The main body of the target company was the members' meeting in each contract.

b) Board: There was only one Hungarian contract in which an 'other corporate body' was established, named as an advisory board. In this contract, there was neither a supervisory board nor an auditor.

c) CEO: Some of the duties and responsibilities of the managing director were regulated in the articles of association but, in a similar way to the German agreements, most rules were in the mandatory corporate law.

d) Supervisory board and auditor: In other two Hungarian contracts, where there was no board, operated a supervisory board and auditor.

Now, let us see what power these corporate bodies have and how the different corporate bodies can work together.

III. Supreme Body of Target Companies

1. Shareholders' Meeting in a GmbH

The shareholders' meeting is the ultimate decision-making body of a GmbH in German law. The shareholders usually exercise their rights at the shareholders' meeting. According to the GmbH Act (Gesetzbetreffend die Gesellschaften mit beschränkter Haftung; GmbH Act), there are two types of shareholders' resolutions:

a) The exclusive competences of the shareholders' meeting.

The powers that are regulated in the mandatory law have to be listed here which and the shareholders cannot diverge from the law (ius cogens). Such powers are, for instance, amending the articles of association;[14] calling in additional contributions;[15] dissolving the company and appointing and recalling the liquidators;[16] and making resolutions regarding measures pursuant to the Transformation Act such as mergers, spin-offs, and changes of legal form.[17]

b) The issues that are generally decided by the management of the company, unless the articles of association of the company provided otherwise.

These issues are not listed in the mandatory law, therefore they belong within the management's competence but, if the shareholders provided otherwise in the articles of association, they can reduce the power of the management and enhance the power of the shareholders' meeting.

- 150/151 -

Moreover, the shareholders' meeting can also reduce the power of the management in other ways, as follows:

a) the shareholders' meeting has the right to instruct the management of the company by its singular resolution, and

b) the shareholders' meeting may set up other corporate bodies and appoint and dismiss the members of these boards.[18] As we mentioned above, in each examined German agreement, the shareholders used this right and set up advisory boards.

In the examined German contracts, the competence of the shareholders' meeting is recorded in the shareholders' agreement and the articles of association. The decision-making system consists of the following rules:

a) General rules: The shareholders' meeting shall have a quorum when the members entitled to vote and representing more than a half of the votes to be cast are present. Unless the mandatory law, the articles of association or the investment agreement provide for a higher majority, all shareholders' resolutions are taken by a simple majority (i.e. more than 50%) of the votes.

b) Veto right: it is not possible to make any resolution in the shareholders' meeting without the consent of the investor. Therefore, the investor alone cannot decide a matter in the competence of the shareholders' meeting, but it can prevent any decision ('destructive veto').[19]

All of the examined German contracts contain a very particular and exhaustive list of topics for the shareholders' meeting. The issues on this list may be decided by the shareholders' meeting with the exclusive destructive veto right of the investor.

Without listing all individual powers of the shareholders' meeting set out in the contracts, the following main groups are highlighted concerning the power of the shareholders' meeting:

a) The exclusive competences of the shareholders' meeting, mentioned above.

b) Every decision related to the structure of the management: determining the number of the managing directors; concluding, amending and terminating the managing director's service agreement, granting sole and joint power of representation to the managing directors, deciding on the remuneration of the managing board; etc.

c) Share-related decisions: approval of the allocation of shares or parts of shares in the company, including any transfer, pledge or other encumbrance, implementation and termination of a trust relationship; resolutions regarding and in connection with the redemption of shares in the company; etc.

d) Establishment of another corporate body: supervisory board, auditor, advisory board and any other corporate body.

e) Approval of certain transactions. This group divides into two further subgroups:

- 151/152 -

- the legal form of contracts: any contract related to real estate (sale, lease, etc.); loan, factoring, etc.;

- the value of the transaction: by using an exact, maximum value of the transaction, or transfer of a significant part of the company assets.

At this point, we should note that the German Federal Supreme Court clarified the competence of the management in the Holzmüller case relating to the transfer of assets. Although it concerned a listed company, we nevertheless highlight the main points of the case regarding the content of investment contracts and the will of the parties to such contracts. The court decided that the management board was not entitled to transfer the assets to the subsidiary without the approval of the shareholders' meeting, as this measure:

- touched upon the core of the company's operation;

- related to the most valuable part of the company; and

- entirely changed the corporate structure.

In the first case, in 1982, the disposal of a business which amounted to 80% of the company's assets, but later in two other decisions, the Courts clarified the first decision: in relation to company restructuring matters, the unwritten authority of the general meeting exists only in relation to measures which:

- result in substantive changes to the articles of association and therefore affect the fundamental authority of the supreme body,

- have a significant economic effect.[20]

In the contracts examined here, we found that the parties to the investment contract diverged from the German mandatory law and, in a similar way to the Holzmüller decisions, defined a significant asset transfer, whether relating to the deal size, or the types of asset deals, and the significant asset deals drew upon the discretion of the shareholders' meeting. Although we do not assume that the parties agreed on the above rules because of the Holzmüller cases, these rules are however deemed to be representative of the international trend of VC investment contracts.[21]

As a summary, we can record that the role of the shareholders' meeting in the corporate governance is the strategic direction of the company; it decides on major transactions, the designation of the management organisation and the appointment of the members of the management.[22]

- 152/153 -

2. Members' Meeting in a Kft.

The legal structure of a Hungarian Kft. is very similar to that of a German GmbH. Although the Kft. has its own legal personality and its members' liability is limited, the liability of members to the company extends only to the provision of their initial contributions, and to other contributions set out in the memorandum of association,[23] but the members do not have securities regarding their legal relationship to the company.[24] The membership of the Kft. is named 'üzletrész, which means all rights and obligations arising in connection with the capital contribution of the members. Üzletrész shall come to existence upon the company's registration.[25] (The üzletrész is generally translated as business share or quota, but in the following we use 'share', whilst the owner of the share is a 'member.)

The most important rules of the Kft. are regulated by the Hungarian Civil Code. Regarding the Hungarian Civil Code, the main decision-making body of the Kft. is the members' meeting. There is no comprehensive list in the mandatory law of the competences of the member's meeting, although some questions can only be decided by it. Such issues are, for instance, the appointment and dismissal of the managing director, the auditor and the members of the supervisory board, increasing and reducing the capital.[26] Other questions fall into the scope of the member's meeting, except if otherwise provided in the articles of association of the company. Those that are not named in the mandatory law or in the articles of association of the company as within the power of the member's meeting or another corporate body fall into the competence of the management.

In the examined Hungarian contracts, the supreme body of the company has very similar competence and process as in the German contracts:

a) The member's meeting is quorate when the members entitled to vote and representing more than a half of the votes to be cast are present. If there is no quorum at the members' meeting, the reconvened members' meeting shall have a quorum for the issues of the original agenda irrespective of the voting rights or investor being represented. In one of the examined contracts, the reconvened members' meeting is also void if the investor is not represented. In this case, the second reconvened members' meeting will only have a quorum irrespective of the investor being represented.

b) Unless the mandatory law, the articles of association or the investment agreement provides for a higher majority, all shareholders' resolutions are taken by a simple majority (i.e. more than 50%) provided the investor supports the decision (destructive veto).

All the examined Hungarian contracts contain a very particular and exhaustive list of topics for the member's meeting. This list is very similar, and the structure of the issues is the

- 153/154 -

same in each German and Hungarian contract, therefore we do not repeat the topics mentioned above.

IV. Management

1. German Structure

To understand the German GmbH management structure, we first examine the main mandatory corporate rules.

The GmbH has two compulsory corporate bodies: the shareholders' meeting and the managing director. One or more managing directors have to be appointed in each GmbH, according to the GmbH Act.[27] The managing director represents the company in legal transactions and performs the management. The law allows management by shareholder or third-party managing directors.[28] The managing director has the right to represent and act on behalf of the company in all legal transactions in and out of court. The scope of his/her authority is unlimited and cannot be limited in relation to third parties.[29] Unless the articles of association provide otherwise, the managing director is only jointly authorised to represent the company.[30] Nevertheless, the articles of association may allow the managing director to have authority to represent the company alone, or together with another managing director or a so-called procuration officer.

The managing director has a large scope of duties. Generally, the main duty of the managing director is to conduct the company's affairs with the due care of a prudent businessman.[31] Some particular duties of a managing director, named in the German mandatory law, are:

a) to ensure that the accounts are kept properly, and balance sheets are drawn up properly;[32]

b) to submit tax returns in the name of the company;[33]

c) that the shareholders' meeting is convened by the managing director;[34]

d) to file the necessary applications with the commercial register;[35]

e) if the company becomes insolvent or over-indebted, the managing director applies for insolvency proceedings to be opened.[36]

- 154/155 -

Unless otherwise provided for in the articles of association, the managing director is appointed and recalled by the shareholders meeting. The resolution on such an appointment must be passed by the majority of the shareholders.[37]

Further corporate bodies are optional, and should be stipulated in the articles of association of the company.[38] The name of these bodies can be very different: advisory board ('Beirat'), administrative board ('Verwaltungsrat') or shareholders' committee ('Gesellschafterausschuss'); but there is no mandatory law for these bodies.[39]

In some cases, the parties of the investment contract cannot diverge from the German mandatory law (ius cogens), whilst in other questions, they can regulate their own legal relationships (ius disponendi). For instance, it has to be at least one managing director in a GmbH, but some duties of the managing director are dispositive rules. Using the opportunity of ius disponendi, the parties agree on setting up a corporate body in every examined contract, which is not regulated by the mandatory law, and is named an advisory board ('Beirat'). In the following, let us see how the examined German contracts regulated the power of the advisory board.

In each transaction, the advisory board is established under the articles of association. The advisory board consists of 3, 4 and 6[40] members in the three examined contracts. In one of the contracts, the members of the advisory board were separately delegated by two investors (2 members) and one member was jointly delegated by the founders. In the other two contracts, the members of the advisory board were appointed by the shareholders' meeting. The resolution on such an appointment shall be passed by the majority of the shareholders. We have to note that although the founders pass resolutions by a majority of votes, as we mentioned above, the investor may block the resolution passed by using its destructive veto right, so in fact the members of the advisory board are 'nominated' by the founders and 'appointed' by the investors. The logic of this system is that the stakeholders (founders, investors) have to agree on the members of the advisory board since this corporate body has a large scope of very important topics with regard to corporate governance.

The list of these topics is very long; the parties listed the competence of the advisory board in detail, in each contract. Without listing all the powers of the advisory board individually, the following main groups are emphasised:

a) CEO: In one contract, the managing director is not appointed by the shareholders' meeting, but by the advisory board. In this contract, the advisory board stipulated the number of directors and their duties as well.

b) Management body: In two contracts, the advisory board has the right to establish the rules of procedure for the management whilst in the third contract the shareholders' meeting

- 155/156 -

shall have such a right. In one contract, the advisory board may decide on the remuneration of the managing director.

c) Financial statements: In each contract, the managing director makes and the advisory board comments on the financial statements (balance sheet, profit and loss account, financial plan, investment plan), which are accepted by the shareholders' meeting.

d) Certain contracts: As we detailed above, the most important contracts are approved by the shareholders' meeting. Other contracts are approved by the advisory board, unless the contracts were less significant or connected to the usual daily business which belongs to the duties of the managing director. In this group, the contracts are categorised based on their subject (e.g. real estate, loan or other financing contract, security contracts, investment transactions, etc.), or because of their value.

e) Employment relationships: conclusion, amendment and termination of key employment contracts; implementation of an employee incentive plan; conclusion, amendment and termination of a collective agreement.

f) Subsidiary company: Setting up or acquisition of a share in another company and decision-making related to subsidiaries.

The advisory board could bring any decisions by passing a resolution, except those decisions delegated to the power of the shareholders' meeting. In the company where the advisory board consists of three members and two members are delegated by the investors, the advisory board shall pass resolutions by a simple majority of votes. In the other two companies, where the majority of the members of the advisory board are delegated by the founders, the advisory board passed resolutions by a simple majority of votes, including the votes to be cast by a member with special rights. This member was delegated to the advisory board directly by the investor.

The managing director shall execute the resolution of the advisory board, but the advisory board cannot make decisions that are against the law, the articles of association and the resolutions of the shareholders' meeting.

2. Hungarian Structure

First, let us review the Hungarian mandatory corporate law.

The management of a Kft. is provided for by one or more managing directors.[41] The managing director can be a natural person or a legal person, but if the executive officer is a legal person then it shall designate a natural person to discharge the functions of the executive officer in its name and on its behalf.[42] The managing director manages the operations of the Kft. independently, based on the primacy of the Kft's interests. In this capacity, the managing director discharges his or her duties in due compliance with the relevant legislation, the articles of association and the resolutions of the company's supreme body (members'

- 156/157 -

meeting). The managing director may not be instructed by the members of the Kft. and he may not be deprived of his powers by the members' meeting.[43] Otherwise, the members' meeting may decide to amend the articles of association of the company and make a decision on changing the duties of the managing director; it can increase or decrease his or her duties.[44]

The general rule of civil law is the decisions that are related to the governance of the company and are beyond the competence of the members shall be adopted by one or more managing directors.[45] The Hungarian Civil Code lists some special rules, which belong to the managing director's duties, unless the mandatory law or articles of association of the company otherwise provide for instance: requesting the registration of the company into the company register, representation of the company, convening the members' meeting, etc. The managing director is responsible for every decision which is not included in the issues of the members' meeting or another corporate body, which are based on the articles of association of the company.[46]

According to the decision of the Hungarian supreme court (Curia of Hungary, 'Kúria'), it is allowed that the structure of a kft.'s management is regulated in the articles of the association differently from the mandatory law and more than one managing director is elected to a management board of the company that can make a decision as a corporate body. Notwithstanding, this structure may not change the representation of the company.[47]

In the examined Hungarian investment contracts, I found two different structures for the board of the target company.

One of the examined Hungarian contracts had a management structure of a board, without a supervisory board. Two of the examined contracts have a management structure without a board but with a supervisory board.[48] The decision-making system in these target companies is presented as follows:

a) The target company in which a board has been set up operated very similarly to the German target companies. In this structure, the members' meeting passed resolutions in the most important but few in number of strategic questions; the board made decisions on the daily operation of the target company and managing director executed these decisions. In this structure, the member's meeting was rarely convened, usually only once a year, but the board had meetings very often, even more than two or three times a month. The main powers of the board are not significantly different from the German structure, focused on personal

- 157/158 -

questions (elect and dismiss the CEO, or other key employees), the operation of the target company's bodies, approval of some financial statements, decision on employee matters, and issues regarding the subsidiaries.

b) In two other contracts, in which a board had not been set up but a supervisory board was established, the competence of the members' meeting is very wide; the members' meeting may pass a resolution on every strategic question and the most important operating questions:

- any question that is delegated to the competence of the supreme body of the company by the mandatory law (e.g. amendment of the articles of association, appointment of the managing director, capital increase or decrease, etc.)

- the management structure of the company (e.g. setting up a new corporate body, remuneration of the managing director and key employees, etc.)

- any change of the ownership structure of the company

- the approval of high value or significant contracts.

In this structure, the managing director only executes the decision of the members' meeting. The managing director can only decide on some questions that are not included in the scope of the members' meeting.

Otherwise, the management's area of control is very wide; the members of the companies elected an auditor and set up a supervisory board in both contracts.

The permanent auditor is always an independent person who inspects the books of the company and his or her report shall be published. The permanent auditor, who is appointed by the supreme body, shall be responsible for carrying out the audits of accounting documents in accordance with the relevant regulations, and shall provide an independent audit report to determine whether the annual accounts of the business association are in conformity with the legal requirements, and whether they provide a true and fair view of the company's assets and liabilities, financial position and profit or loss.[49]

Members of the Kft. may provide, in the articles of association, for the establishment of a supervisory board. The supervisory board's task is the supervision of the management in order to protect the interests of the Kft. Regarding the statutory law, the members of the supervisory board shall be independent of the management of the legal person, and shall not be bound by any instruction in performing their duties.[50] Nevertheless, it is not prohibited for a member of the permanent supervisory board to be a member of the target company, or his/her representative.

The members of the examined target companies set up a supervisory board at the request of the investor and one member of the supervisory board is always the deputy of the investor. The investor required the establishment of the supervisory board since, in this structure, the members' meeting may decide on almost every issue of corporate governance, provided the investor supports the resolution, but the investor is not an active player in the daily business of the company, therefore he or she needs information related to the operation of the

- 158/159 -

company. The supervisory board continually supervised the management of the company; it had up-to-date information about the problems with the business of the company or the success of the managing director. The member of the supervisory board delegated by the investor informed the investor about these problems or good news. According to the examined contracts, the investor had the right to know about these problems and had the power to make effective decisions at the members' meeting to deal with such issues.

We have to emphasise that, the member of the supervisory board who was delegated by the investor was not independent; he or she had some legal relationship with the investor and the investor had the right (directly or indirectly) to instruct their deputy supervisory board member. Moreover, the parties accepted in the investment contract that the investor member of the supervisory board could first of all or more particularly inform the investor on the affairs of the target company. Because of their legal relationship, this member supervises the management of the company in favour of the investor, but not in favour of the company or every member of the company. Although we do not know a mandatory law that prohibits this structure, corporate governance can however be deformed by the non-independent supervisory board member.[51]

V. Governance and Management

According to Tricker, a distinction must be made between governance and management: the management runs the business; the board ensures that it is being well run and run in the right direction.[52] In the following, we summarize the theory of the actors regarding the examined transactions and their roles in corporate governance; later we present the management structure in the target companies.

a) Executive director

The executive director is the executive manager of the company who is engaged in the daily management of the company. The chief executive officer is often known as the managing director. The executive manager is usually a member of the management board.[53]

b) Non-executive director

A non-executive manager is the member of the board who does not hold any executive management position in the company.[54] The 2003 Higgs Review stated that

- 159/160 -

The role of the non-executive director is frequently described as having two principal components: monitoring executive activity and contributing to the development of strategy. (...) However, as the non-executive directors do not report to the chief executive and are not involved in the day-to-day running of the business, they can bring fresh perspective and contribute more objectively in supporting, as well as constructively challenging and monitoring, the management team. (...) The role of the non-executive director is therefore both to support executives in their leadership of the business and to monitor and supervise their conduct.[55]

Tricker makes a difference between an independent and a connected non-executive director. The independent non-executive director is a director with no affiliation or other relationship with the company, except the directorship, that could affect, or be seen to affect, the exercise of objective, independent judgement. The connected non-executive director is a director who is not a member of the management but does have some relationship with the company and can affect the management. Such a connected non-executive director is a nominee director, who has been nominated to the board by the majority of shareholders.[56]

In the EU law, a 2005 Commission Recommendation on the role of non-executive or supervisory directors of listed companies and on the committees of the (supervisory) board stated that: 'a director should be considered to be independent only if he is free of any business, family or other relationship, with the company, its controlling shareholder or the management of either, that creates a conflict of interest such as to impair his judgement![57] Annex II of the Recommendation clarified that it is not possible to give a comprehensive list of all threats to the directors' independence but it gave some criteria related to the independence of the directors. Some of them:

- not to be an executive or managing director of the company or an associated company, and not having been in such a position for the previous five years;

- not to be an employee of the company or an associated company, and not having been in such a position for the previous three years;

- not to receive, or have received, significant additional remuneration from the company or an associated company apart from a fee received as non-executive or supervisory director;

- not to be or to represent in any way the controlling shareholder(s);

- not to have, or have had within the last year, a significant business relationship with the company or an associated company, either directly or as a partner, shareholder, director or senior employee of a body having such a relationship;

- not to be, or have been within the last three years, partner or employee of the present or former external auditor of the company or an associated company;

- 160/161 -

- not to be executive or managing director in another company in which an executive or managing director of the company is non-executive or supervisory director, and not to have other significant links with executive directors of the company through involvement in other companies or bodies.

c) Chairman

According to Smerdon: 'there should be a clear division of responsibilities at the head of the company between the running of the board and the executive responsibility for the running of the company's business![58] The reason for this separation is to avoid the potential for abuse if power is concentrated in a single person and enable the chief executive to concentrate on managing the business whilst the chairman handles the running of the board and relations with shareholders and other non-contractual stakeholders such as the government, the regulators and the media.[59]

According to the 2003 Higgs Review, the most important responsibilities of the chairman are to:

- run the board and set its agenda;

- ensure that the members of the board receive accurate, timely and clear information, particularly about the company's performance, to enable the board to take sound decisions, monitor effectively and provide advice to promote the success of the company;

- ensure effective communication with shareholders and ensure that the members of the board develop an understanding of the views of major investors;

- manage the board to ensure that sufficient time is allowed for discussion of complex or contentious issues, with appropriate arrangement for informal meetings beforehand to enable thorough preparation for the board discussion.[60]

Tricker makes a difference between four groups of the board structure: a board only with executive directors, a board with a majority of executive directors, a board with a majority of non-executive directors and the board only with non-executive directors. In the all-executive director board, the top managers are also the directors, whilst the all non-executive director board is entirely composed of non-executive directors. Logically, the board composed with the majority of the executive directors is the majority executive director board, and the board with the majority of the non-executive directors is the majority non-executive director board.[61]

Now, regarding Tricker's grouping, we classify the examined corporate governance structures.

An advisory board was established in four of the examined contracts and in parallel, a supervisory board does not operate in these companies. In two other (Hungarian) contracts, although there was supervisory board and an auditor and advisory board was not established.

- 161/162 -

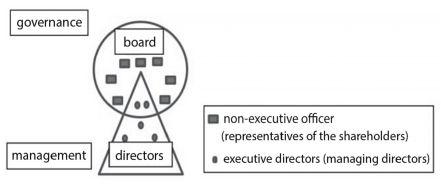

The governance structure, where there was an advisory board, is the following.

a) Majority non-executive director board

In two German and one Hungarian contracts, the board structure is the same: the members of the advisory board were composed of, on the one hand, the representative of the investors and founders and, on the other hand, of the managing directors. The representatives of the shareholders were directly delegated to the advisory board by the shareholders or by a resolution of the shareholders' meeting and they were the non-executive managers of the company. The members of the advisory board, delegated by the shareholders or the founders, were non-independent non-executive directors of the company. The managing directors, who were the executive directors of the company, had the same rights in the board as the nonexecutive directors but they were always in a minority. The chairman of the advisory board was delegated by an investor in the Hungarian contract and elected by the members of the advisory board in the German contracts. There was only one contract where the chairman was also the managing director.[62]

The majority non-executive director board is showed in Figure 2 below:[63]

Figure 2: Majority non-executive director board

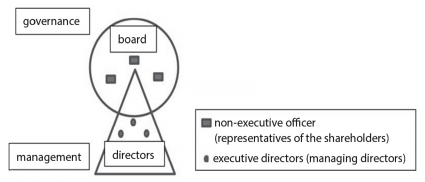

b) All non-executive director board

There was only one German contract where the managing director was not a member of the advisory board. The members of the advisory board are composed of the representatives of the investors and founders. The representatives of the shareholders are directly delegated to the advisory board by the shareholders (not independent non-executive directors) and the chairman was elected by the members of the advisory board.

The all non-executive director board is showed by the Figure 3:[64]

- 162/163 -

Figure 3: All non-executive director board

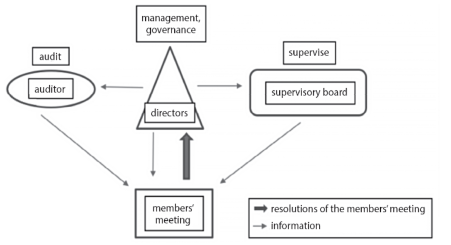

We had only two Hungarian contracts where there was no advisory board but there was a supervisory board and an auditor. This system is often named two-tier or supervisory board architecture (see Figure 4), but we have to emphasize again that, in these contracts, the supervisory board does not have the right to decide on any issues.[65]

Figure 4: Two-tier system

In this system, the supervisory board only supervises the management of the company. Nevertheless, the supervisory board is obliged to supervise the management and company's economic status in order to report to the members' meeting. The necessary decisions are made upon this information by the members' meeting.[66] The members of the supervisory

- 163/164 -

board were always delegated by the investor and the founders (non-independent member) and the supervisory board decided by a simple majority of votes, including the votes cast by a member delegated by the investor.

In this structure, the members always appointed an auditor by passing a resolution at the members' meeting with a simple majority of votes including the votes cast by the investor.

VI. Final Remarks

1. Summary of the Corporate Governance in the Examined Investment Contracts

Finally, we examine the power relations in the target company, and it is time the draw conclusions and pinpoint the person who really manages the target company.

We have to identify the actors in corporate governance and characterise their roles. In this context, we can set up three groups regarding the roles of the shareholders' and members' meetings, the advisory board, the managing directors, the supervisory board and the auditor.

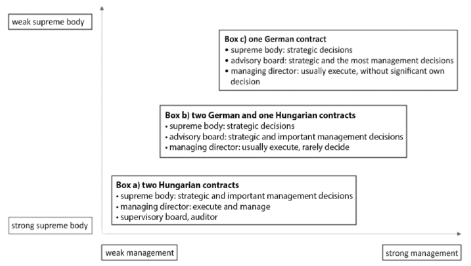

I found that, from this aspect we can group the examined contracts and make three different groups regarding the strength of the management or the main body of the target company.

a) Strong members' meeting

In the first group, there are two Hungarian contracts in which there was no advisory board but there was a supervisory board and an auditor. In this structure, the members' meeting was convened very often since the members of the company constituted articles of association that diverged from the main rules of the Hungarian Civil Code and there are many additional powers in favour of the members' meeting. Usually, these powers are the competence of the managing director; therefore the articles of association deprived the management of power. Any other power shall not fall within the scope of duties of the managing director.

In this structure, there was a supervisory board and an auditor but they both only supervised the operation of the managing director and made reports to the members' meeting. The necessary decision, based on this report, was made by the members' meeting. See Figure 5 with the sign 'Box a).

b) Balanced corporate governance

The third Hungarian contract and two German contracts are in this group. In these contracts, a corporate governance system was constructed in which there was a relatively strong shareholders' or members' meeting but the majority of the management tasks fell within the competence of the advisory board. The advisory board was convened very often and the company was actually managed by the advisory board. Furthermore, the main issues of the corporate governance were shared between the advisory board and managing director, whilst the managing director not only made decisions but he or she executed the resolutions

- 164/165 -

of the shareholders' and members' meeting and of the advisory board, too. See Figure 5 below with the sign 'Box b)'.

c) Strong management

Finally, in the third group there is only one German contract. The corporate governance structure was very similar to group b) but here the advisory board was stronger than mentioned above, since it could make resolutions in more issues related to corporate governance, including the appointment of the managing director. Mainly this latter power explains why we classify this corporate governance in another group, because the advisory board was able to actually manage the company, and if the members of the advisory board were not satisfied with the execution of their resolution then they could dismiss the managing director and appointed another one. See Figure 5 below with the sign 'Box c)'.

The three groups related to corporate governance are illustrated in Figure 5. The vertical axis shows how strong the main body is and the horizontal axis shows the strength of the management. Of course, this is only a screenshot of a company's corporate governance and it must always be borne in mind that the members were able to change the power of each corporate body at any time by modifying the articles of association.[67]

Figure 5: Corporate governance in the examined contracts

- 165/166 -

2. Conclusions

As a summary, regarding Figure 5 above, we can conclude that the parties strongly applied their freedom to derogate from the statutory law. The main purpose of the divergence was to protect the investor and therefore the parties amended the rights of the supreme body and the management. Those parties changed their form of corporate governance Nevertheless, our experience is that there is no significant difference between the German and the Hungarian investment contracts where the parties constructed an advisory board. In the case of the Hungarian contracts in which no advisory board was established but there was a supervisory board and an auditor, we found a different corporate governance system but we can state that this solution is also effectively able to protect the investors' interest by applying another legal way.

So, who manages the target company? We found that, the investor has a strong influence on the management of the target company. It can be a direct influence when the investor exercises his or her voting right in the main body of the target company, as we saw in the cases of two Hungarian contracts, or it can be indirect when the investor's delegated person exercises the will of the investor in the board of the target company as we saw in the cases of all the target companies where a board had been established. Anyway, we can conclude that, after the first VC investment, the target company's corporate governance was changed, and the investor has the right to manage the decisions of the target company.

Although we analysed in detail the corporate governance system but have not examined the strength of the investor's voting rights in either the main body or in the board of the target company. As such, we have to emphasise that although we stated that the investor can manage the target company, we did not state that the investor manages the target company alone in any and all cases. The strength of the investor's rights in the target company is another topic which requires further research and another study. The writer of these lines hopes the reader will read our next study on investors' rights with interest. ■

NOTES

[1] David McWilliams, 'Ireland Inc. Gets Innovated' Sunday Business Post On-line; in Start Up Nation (Dan Senor, Saul Singer, Twelve, 2011) 208.

[2] Azin Sharifzadeh, Venture Capital and Corporate Governance, Inaugural-Dissertation zur Erlangung des Doktor grades des Fachbereichs Wirtschaftswissenschaften der Johann Wolfgang Goethe-Universität Frankfurt am Main, (LLM thesis, University of Augsburg 2010) 81-83.

[3] Eli Talmor, Florin Vasvari, International Private Equity (John Wiley & Sons 2011, Hoboken, New Jersey) 365.

[4] Unknown writer, sources: <http://www.netvalley.com/silicon_valley_history.html> accessed 24 August 2019.

[5] Timothy Spangler, The law of private investment funds (3rd edn, Oxford University Press 2018) 1-27.

[6] Michael Quinn Patton, Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods (3rd edn, Sage Publications 2002, London) 45.

[7] Lisa Webley, 'Qualitative Approaches to Empirical Legal Research' in Peter Cane, Herbert Kritzer (eds), Oxford Handbook of Empirical Legal Research (Oxford University Press 2010) 7.

[8] Juliet Corbin, Anselm Strauss, A kvalitatív kutatás alapjai (L'Harmattan 2015, Budapest) 71.

[9] Richard Smerdon, A practical Guide to Corporate Governance (Sweet & Maxwell 2007, London) 3.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Key Performance Indicator, i.e. the conditions, the target company should fulfil to receive the investment funds, or any part thereof.

[12] Peter Cowley, The Invested Investor (Invested Investor Limited 2018) 124-130.

[13] Sec. 6 GmbH Act. See more: Frank Dornseifer (ed), Corporate Business Forms in Europe (Seiller, European Law Publisher GmbH 2005, München, 103-186 by Frank Dornseifer) 154-160.

[14] GmbH Act, s 53-58.

[15] GmbH Act, s 26.

[16] GmbH Act, s 60, 66.

[17] Transformation Act s 13, 50, 125, 193, 226.

[18] Gerhard Wirth, Michael Arnold, Ralf Morshäuser, Mark Greene, Corporate law in Germany (2nd edn, C. H. Beck 2010, München) 31-32.

[19] See more on the destructive veto right: Sharifzadeh (n 2) 57-58; and Neil J. Beaton, Valuing Early Stage, Venture-Backed Companies (John Wiley & Sons 2010, Hoboken, New Jersey) 27; and Dick Costolo, Brad Feld, Jason Mendelson, Venture Deals: Be Smarter Than Your Lawyer and Venture Capitalist (2nd edn, John Wiley & Sons 2012, Hoboken, New Jersey) 63-73., and Keith A. Allman, Impact Investment: A Practical Guide to Investment Process and Social Impact Analysis (John Wiley & Sons 2015, Hoboken, New Jersey) 171-175.

[20] BGH 25.02.1982, Az.: II ZR 102/81 in M. J. Thomas Möllers, German and European company law (university notes, University of Augsburg 2017) 15.

[21] Orrick, Herrington & Sutcliffe LLP (Markus Piontek, Vanessa Sousa Höhl, Johannes Rüberg, John Harrison Barbara Hasse, Lars Wöhning, Justine Koston), Orrick's Guide to Venture Capital Deals in Germany (Orrick, Herrington & Sutcliffe LLP, January 2018) 54.

[22] See more about the role of the shareholders: Ken Rushton, The business case for corporate governance (Cambridge University Press 2008, Cambridge) 81-99.

[23] 2013. évi V. törvény a Polgári Törvénykönyvről (Act V of 2013 on the Hungarian Civil Code) 3:159.

[24] Kisfaludi András, Szabó Marianna (eds), A Gazdasági Társaságok Nagy Kézikönyve (Complex 2008, Budapest) 875; Pintér Attila, Az üzletrész-átruházási szerződésről' (2016) 24 (5) Gazdaság és Jog 11-15.

[25] Hungarian Civil Code (n 23) book 3:164. (1).

[26] Osztovits András (ed), A Polgári Törvénykönyvről szóló 2013. évi V. törvény és a kapcsolódó jogszabályok nagykommentárja, I. kötet (Opten Informatikai Kft. 2014, Budapest) 668, (by Pázmándi Kinga).

[27] GmbH Act s 6 para (1).

[28] GmbH Act s 6 para (3).

[29] GmbH Act s 37 para (2).

[30] GmbH Act s 35 para (2).

[31] GmbH Act s 43 para (1).

[32] GmbH Act s 41, 42.

[33] The Fiscal Code of Germany, s 34.

[34] GmbH Act s 49 p (1).

[35] GmbH Act s 78.

[36] German Insolvency Statue s 15a. p (1).

[37] Wirth et al. (n 18) 38-48.

[38] Karel Van Hulle, Harald Gesell (eds), European corporate law (Nomos 2006, München) 157.

[39] Wirth et al (n 18) 50.

[40] In this contract, there were several investors in the transaction and the company was also in its later phase; probably that was the reason for the high number of members.

[41] Hungarian Civil Code book 3 s 196 p (1).

[42] Hungarian Civil Code book 3 s 22 (2).

[43] Hungarian Civil Code book 3 s 21. p (2) and book 3 s 112. p (2).

[44] Petrik Ferenc (ed), Polgári jog, jogi személy (HVG-ORAC 2014, Budapest) 161.

[45] Hungarian Civil Code book 3 s 4. p (2)-(3), book 3 s 21. p (2)

[46] Barta Judit, Harsányi Gyöngyi, Majoros Tünde, Ujváriné Antal Edit, Gazdasági Társaságok a Polgári Törvénykönyvben (Patrocinium 2016, Budapest) 89.

[47] BDT 2015. 3272.

[48] See more about the participation of the investors in the management of the target company in Hungary: Karsai Judit, A kockázati tőkéről befektetőknek és vállalkozóknak (Magyar Befektetési és Vagyonkezelő Rt. 1998, Budapest) 64-72.

[49] Hungarian Civil Code book 3 p 129 s (1).

[50] Hungarian Civil Code book 3 p 26 s (1).

[51] See more about the independent manager: Lawrence A. Cunningham, 'Rediscovering Board Expertise, Legal Implications of the Empirical Literature' in F. Scott Kieff, Troy A. Paredes (eds), Perspectives on Corporate Governance (Cambridge University Press 2010) 62-95.

[52] Bob Tricker, Corporate Governance, principles, polices, and practices (Oxford University Press 2009, Oxford) 35.

[53] Tricker (n 52) 50.

[54] Tricker (n 52) 50.

[55] Derek Higgs, 'Review of the role and effectiveness of non-executive directors' 2003, 27-28. <http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20070603185143/http://www.dti.gov.uk/bbf/corp-governance/higgs-tyson/page23342.html> accessed 18 August 2018.

[56] Tricker (n 52) 50-53.

[57] Commission recommendation of 15 February 2005 on the role of non-executive or supervisory directors of listed companies and on the committees of the (supervisory) board (Text with EEA relevance) (2005/162/EC) s 13.1.

[58] Smerdon (n 9) 179.

[59] Tricker (n 52) 58.

[60] Higgs (n 55) 99.

[61] Tricker (n 52) 61-67.

[62] See more about the busy director: Darina Feicha, Board Structure and Auditor-Clint Negotiations, (Inauguraldissertation zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades eines Doktors der Wirtschaftswissenschaften der Universität Mannheim 2015) 52-55.

[63] Based on: Tricker (n 52) 36 and 62.

[64] Based on: Tricker (n 52) 36 and 64.

[65] Tricker (n 52) 64; and Jean J. du Plessis, Bernhard Großfeld, Claus Lutterman, Ingo Saenger, Otto Sandrock, Matthias Casper, German Corporate Governance in International and European Context (3rd edn, Springer 2017) 8-13.

[66] Kecskés András, Felelős társaságirányítás (corporate governance) (HVG-ORAC 2011, Budapest) 263-311.

[67] See more the relationships of the corporate bodies: Hossam Zeitoun, Corporate Governance Modes, Stakeholder Relations, and Organizational Value Creation (PhD diss. 2011, Zurich) 2-19, 61-79.

Lábjegyzetek:

[1] The author is a doctoral student, attorney, Eötvös Loránd University Faculty of Law. Contact details: Hungary, 1112 Budapest, 1-3. Keveháza utca, e-mail: pinter.attila@pinterlaw.hu.