István Hoffman[1]: Welfare Services and the EU - Harmonising Systems without Legal Harmonisation? (ELTE Law, 2025/1., 45-58. o.)

https://doi.org/10.54148/ELTELJ.2025.1.45

Abstract

The literature has emphasised that the EU has different competences in different policies, and that the competences of the EU in the field of welfare (social and health care) services are relatively limited. First, the article will examine the role and impact of the Open Method of Coordination, namely, how the coordination of these services impacts the standardisation of welfare services.

Similarly, the role of EU funds in influencing the welfare policies of EU Member States will be analysed. The rules on the funds of the European Cohesion Policy and 'soft' regulations relating to them greatly influence the regional development policies of these countries. The conditions defined by the EU regulations on development funds greatly influence even those Member States' policies that are primarily defined as national policies. As a result of my research, it should be emphasised that there is no direct legal harmonisation in the field of welfare services. Yet, certain tools still result in the indirect legal harmonisation of laws in these fields, such as the Open Method of Coordination, the cohesion policy of the EU, and especially conditionality within cohesion policy.

Keywords: regional development, welfare services, open method of coordination, Regulation (EU) 1060/2021, multilayer governance, soft power

- 45/46 -

I. Introduction and Methods

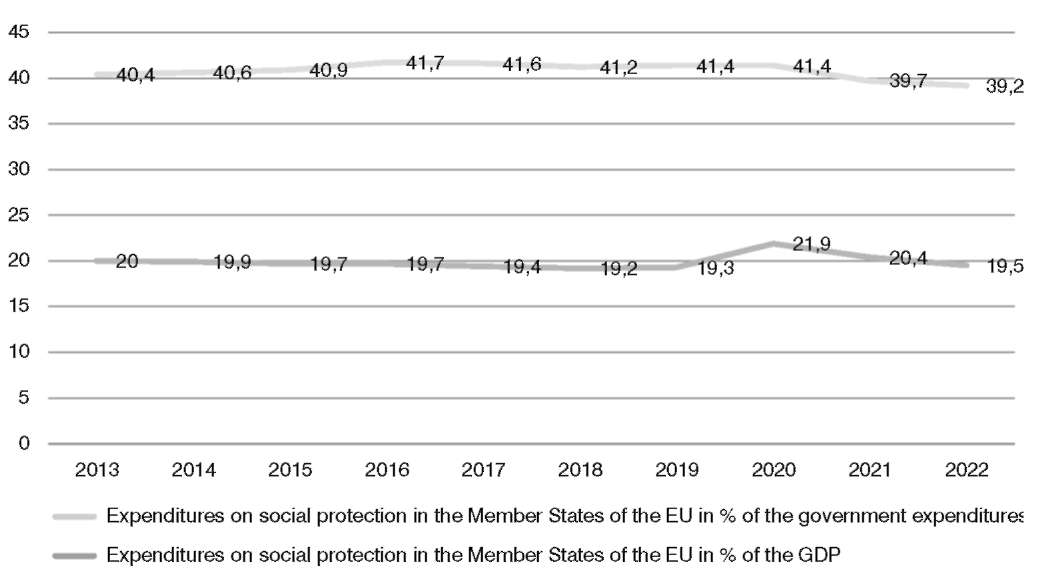

The Member States of the European Union can be considered welfare states,[1] therefore, the role of social policy can be interpreted as very significant in these countries. Around 40 per cent of government expenditure is associated with the funding of the social protection systems in the EU, and these expenditures account for around 20 per cent of the GDP of the EU (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Expenditure on social protection in the EU27 (2013-2022)[2]

Thus, welfare services play an important role in the EU economy.[3] These services are mainly interpreted as services of general interest, and thus, traditionally, the role of integration is limited in this field. The main aim of my paper is to review the legally 'soft' tools of the EU that significantly influence national policies. Thus, I would like to analyse how the EU could impact these services using legally non-binding tools and other EU policies (mainly cohesion

- 46/47 -

policy). I examine how a converging welfare environment may be implemented without or with limited legal harmonisation.

The method of my analysis is based mainly on the jurisprudential approach. Therefore, my examination will focus on legal regulations and judicial practice. My paper will review the socio-economic background and the major models of social policy as part of the analysis of the regulatory ecosystem. In addition, a comparative approach will be applied because the systems of the different Member States will be partially compared.[4]

II. Legal Harmonisation and Welfare Services

1. General Framework

The literature emphasises that the values of the European Union are based on legislation and rules because they may be enforced by the EU bodies (especially by the Commission and the European Court of Justice).[5] Similarly, authors have underlined that subsidiarity became a principle, but the role of directly applicable EC (later EU) regulations has increased in the last decades.[6] Thus, examinations based on the jurisprudential approach have focused on the role of EU legislation, especially on directly applicable regulations and EU directives.[7]

Welfare services are interpreted by European law as services of general interest. Therefore, their provision belongs primarily to the competences of the Member States.[8] Therefore, as seen later, the EU does not have general legislative power in this field.[9] The main fields of

- 47/48 -

harmonisation can be considered indirect tools. The EU's labour law and employment directives also indirectly impact welfare services. Still, their role in influencing the cost of labour, such as the working time directive, significantly impacts the management of human resources by the institutions providing services and, to some extent, wage costs.[10]

2. 'Land of Confusion' - Different Models and Approaches to the Social Policies of the Member States of the European Union

In an analysis of the role of the EU in the field of welfare services, it should be mentioned that the social policy approaches are quite diversified in the different Member States of the European Union. These models can be distinguished in various ways, but the most widely accepted classification in the literature is based on the research of G0sta Esping-Andersen.[11] As it is clear, at least three - and if we apply the modified Esping-Andersen and the later developed other models, even four or five - models have evolved in the Member States of the European Union.[12] Therefore, even the coordination of these models can be considered a regulatory challenge for European integration.[13]

3. 'Navigare necesse est' - The Coordination of Welfare Regulation in the EU and Legislative Competences of the EU

The idea of European integration has been based on the 'four freedoms': the free movement of persons and the free movement of people, goods, services and capital. However, there was debate over whether to include social policies in the integration process during the 1950s, which led to the inclusion of certain social policy measures under the framework established by the Treaty of Rome.[14]

- 48/49 -

The enforcement of the 'four freedoms' has even impacted national welfare services. These services have an important role in the quality of life of workers, and their status significantly influences the free movement of persons. It is especially social security benefits and services that directly impact the latter: before these systems were coordinated, the possible loss of social security benefits may have influenced the migration of workers.[15] Therefore, the coordination of social security systems is one of the most important issues for European integration in the field of welfare services. It should be emphasised that the coordination of the systems is quite different from the harmonisation of welfare services; it focuses on the interoperability between them.[16] Even in the first period of European integration in the late 1950s and later during the late 1960s and 1970s, these issues were regulated by community legislation[17] and now, the current Regulation (EC) No 883/2004 defines the major rules of this coordination.[18] The principles of the previous coordination regulations and the scope of the benefits concerned have not fundamentally changed. First of all, it should be noted that coordination typically covers insurance-based and universal benefits and does not apply to means-tested benefits, which have become increasingly important in the EU since the economic crisis.[19]

Legal harmonisation was strengthened by the amendments to the Treaty of Rome. The Single European Act, the Treaty of Maastricht and the Treaty of Amsterdam introduced new community legislative competences, especially in the field of public health and individual and collective labour law.[20]

It should be emphasised that the judicial practice of the European Court of Justice (ECJ) has had a significant influence on national welfare policies. Because of the relation between the four freedoms and the welfare policies, there are several landmark decisions, especially related to the free movement of services, which have even impacted national legislation. First, it should be noted that rules on the free movement of services should also be applied to health services that fall under the scope of welfare services, as stated in the Luisi & Carbone case.[21] In this case, it was generally indicated that cases when a person travels to another country to receive health and medical services are also covered by the free movement of services provisions of the EEC Treaty. This right cannot, in the view of the Court of Justice of the European Communities, be unlawfully restricted. Within the above framework, the

- 49/50 -

European Court of Justice first stated in the Grogan[22] case that health care and, in this case, abortion-related treatments could be interpreted as services based on the direct economic relationship between the provider and the recipient and that the rules on the free movement of services, therefore, should apply. In these cases, the ECJ clearly recognised the service character of privately funded welfare (including health) benefits.[23] It was questionable whether social security benefits could be included in this scope. In the Kohll case, the ECJ recognised that social security benefits could also be covered by the free movement of services regime.[24]

The principle of free movement of goods and services has led to increased competition and a more unified market in the European area, particularly in the pharmaceuticals market.[25] Accordingly, in the Decker case, the Court of Justice ruled that the failure of the Luxembourg social security body to reimburse the price of glasses purchased in Belgium was contrary to the principle of free movement of goods.[26] However, the European Court of Justice has been consistent in not classifying social security bodies as undertakings. The Court first stated that in the Poucet and Pistre judgment.[27] In the AOK Bundesverband case, the ECJ also ruled[28] that associations of these insurers cannot be considered undertakings either. In the INAIL case,[29] the Court stated that the existence of only one insurance body for accidents in a country did not infringe competition rules.

It seems that there was a paradigm shift in EU legislation in 2016 and 2017, when first the president of the European Commission, Jean-Claude Juncker, announced the European Pillar of Social Rights. Based on the announcement, the European Social Pillar was proclaimed as a (joint) communication by the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the

- 50/51 -

Regions.[30] The European Social Pillar defines 20 principles in three chapters. It should be mentioned that the Pillar may not be interpreted as a legally binding regulation; it is a soft law document. The literature emphasises that the pillar is based on the European Charter of Fundamental Rights and the current European legislation. It may not be interpreted as a document by which legislative competences are created. It can be considered a summary of the results of Social Europe, and the 'principles' could be the basis for starting new European policies and the coordination of the system. It can even be interpreted as a principle of the EU's cohesion policy in the field of social cohesion. Thus, the literature mainly considers it the 're-packaging' of European social policies and activities.[31]

III. Harmonising without Legal Harmonisation: Soft Tools of the European Union

As seen above, the influence of 'traditional' legal harmonisation can be considered limited in the field of welfare services. Therefore, the role of 'soft' harmonisation tools may be appreciated in this field because the EU Treaties, the policy documents, involve quite extensive soft policy making. Similarly, other EU policies - as may be seen later, especially cohesion policy - give the opportunity to build a more harmonised welfare system in Europe.

1. Open Method of Coordination as a Soft Form of Harmonising Different Systems

One of the most significant innovations of the Amsterdam Treaty and one of the most important European integration steps was the establishment of policy on the inclusion of the fight against social exclusion in EU social policy and the introduction of the Open Method of Coordination (OMC) of the social policies of the Member States. Originally, the first OMC was introduced in the field of employment-related policies.[32] In the first step, the Council sets strategic objectives. Then, based on a Commission proposal, the Council sets guidelines and indicators, based on which each Member State prepares a national action plan. The Commission evaluates these and their implementation, summarises 'good

- 51/52 -

practices', and finally, as a kind of feedback, proposes the next strategic orientations on the basis of the evaluation.[33]

The OMC has been hailed by many as a revolutionary breakthrough and a non-legal instrument for building a social Europe. It can be argued that it is closely aligned with the development of EU law, which is built in many ways on the interactive, consensual elements of good governance.[34] Cooperation at the union level has been achieved without transferring the national competences to supranational bodies.[35] The OMC became an important tool for harmonising European welfare service systems.[36] Although the approaches have been different, this soft, legally non-binding tool has offered the opportunity to adapt successful answers to the same socio-economic challenges. Thus, several important elements of the welfare services have been harmonised by applying this method.[37]

The main advantage of open coordination is also its main disadvantage. Due to the lack of direct union (legislative) competences, the system operates successfully if all Member States participate voluntarily and in cooperation with each other. In practice, there have been differences in the approach of the Member States to cooperation.[38]

While there have been difficulties and differences, the application of OMC has facilitated the exchange of national experiences, particularly in the fields of social inclusion, pensions, health care and care for the elderly, thus promoting the development of more harmonised European legislation by adopting good practice and encouraging a process of convergence between European welfare systems.[39]

2. Cohesion Policy as a 'Soft Tool' for Influencing National Policies

Cohesion policy - which was incorporated into the Treaties by the Single European Act -may impact the policies of the Member States of the European Union. Paragraph 1 of Article 174 of TFEU states that the 'Union shall develop and pursue its actions leading to the strengthening of its economic, social and territorial cohesion'. Thus, Article 174 of TFEU provides an opportunity for the EU to influence the performance of the competences of the

- 52/53 -

Member States, and the welfare policies belonging to these policies because they are related to 'social [...] cohesion'.[40] Based on this regulation, the EU has developed a cohesion policy that covers not only the traditional EU competences. The abstract rule of Article 174 of the TFEU fits with the transformation of the EU, which is an economic integration and an area of common political and social values.[41] Because of these common values, not only can the financial type of conditionality be applied by the EU, but based on this approach, the rules on cohesion policy have been transformed in the last few years.[42] The conditionality mechanism has been introduced by the current regulations on cohesion policy - especially Regulation (EU) No 2021/1060 (hereinafter: Framework Regulation). The background regulation of Article 15 is Regulation (EU, EURATOM) No 2020/2092 on a general regime of conditionality for the protection of the Union budget. These regulations offer the possibility of suspending the EU's funding based on the need to protect its basic values. These rules were contested by Hungary, but the action was dismissed by the European Court of Justice. However, the action of Hungary was based on the EU's lack of competence in such a regulation; the ECJ stated that Articles 2 and 7 of the TFEU could be interpreted as legitimate bases for the rule of law conditionality mechanism. The ECJ highlighted that the values of the rule of law 'define the very identity of the European Union as a common legal order'.[43] Therefore, they could be enforced by the tools of EU cohesion policy.

The cohesion policy of the EU can be interpreted as a complex policy. The original concept, which was based on the 'economic integration' nature of the EU, has been transformed, and now this policy can influence the public service provision of the Member States of the European Union.[44] The cohesion policy of the EU is primarily based on reducing regional disparities. During the budgetary period 2021-2027, 61.3% of the resources for the investment into jobs and growth have been allocated to less developed regions (whose GDP at purchasing power parity is less than 75% of the EU27 average) [Article 110 of the Regulation (EU) No. 2021/1060]. Therefore, the main recipients of these funds are the new Member States of the European Union because their regions mainly belong to this category.[45] The role of cohesion policy is very important in the budgetary policies of these

- 53/54 -

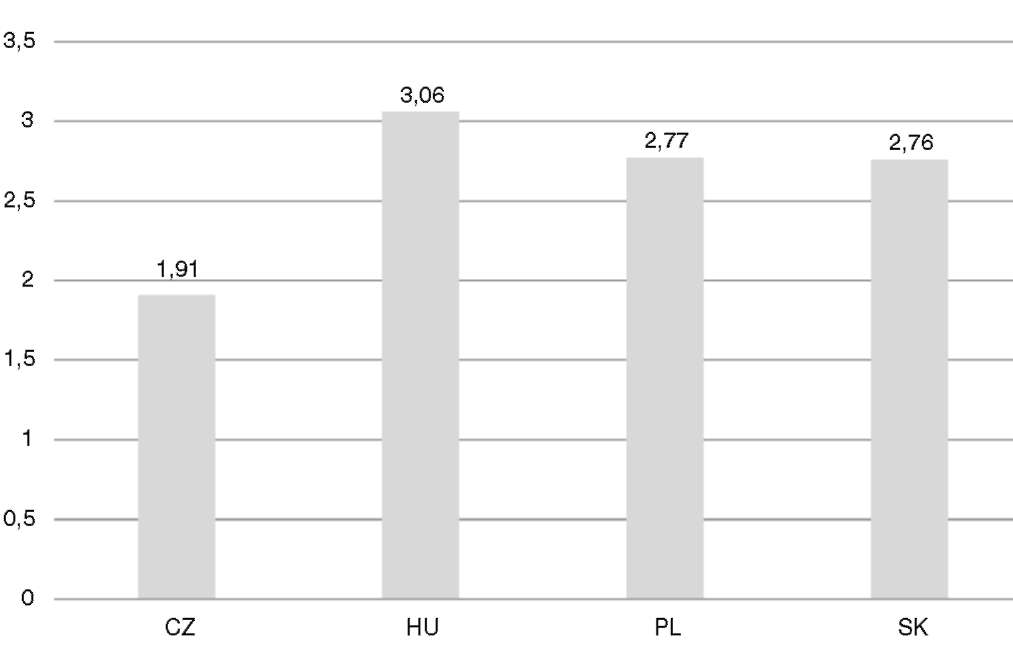

countries.[46] If we look at the Visegrád countries (the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland and Slovakia, which countries joined the European Union in 2004), the actual payments (including the n+2 payments) from the European Structural and Investment Funds may be interpreted as significant.

Figure 2. Yearly European Structural and Investment Funds (ESIF) from EU (2014-2020) as share of average of 2014-2020 GDP (current market prices) (%)[47]

The above-mentioned abstract and general regulation of the TFEU offers a wide range of EU interventions. Similarly, the European Social Fund, which was established by the Treaty of Rome, subsidises not only employment issues but even welfare services.[48] Therefore, the EU funds could influence these national policies, which are defined mainly as the competences

- 54/55 -

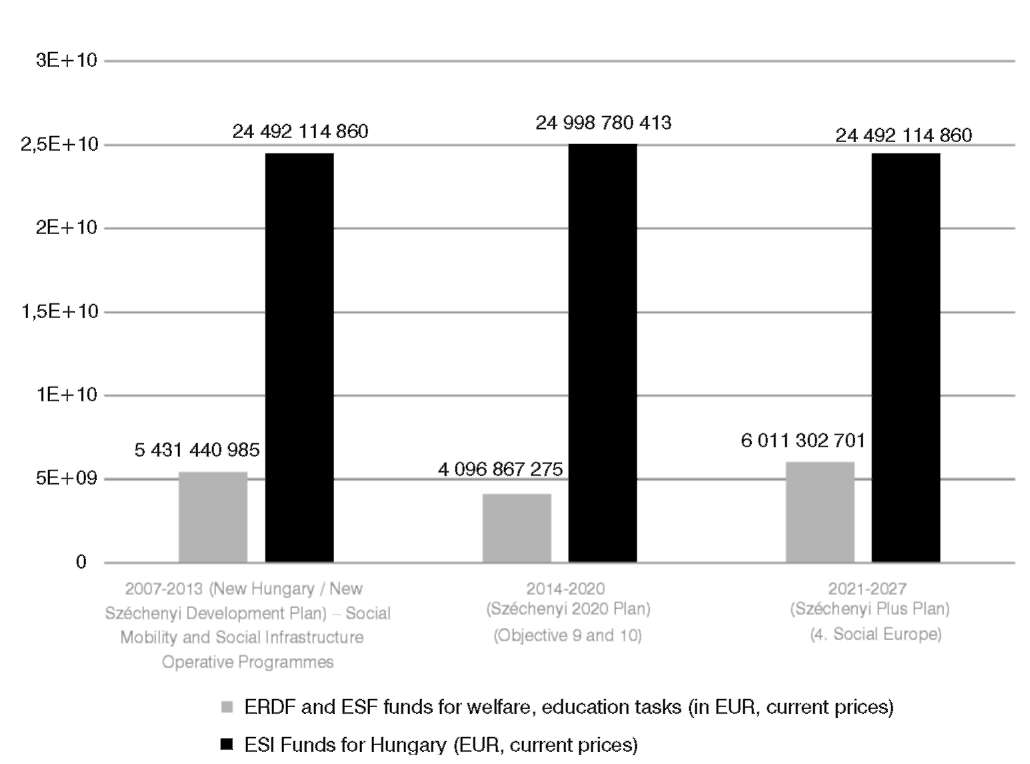

of the Member States.[49] Similarly, because the less developed regions are the main target areas for cohesion policy, the policies of those countries are impacted significantly by countries with lower GDP. Therefore, the welfare, educational and cultural policies of the new Member States of the EU - which accessed the EU after 2004 - are significantly more influenced by the cohesion policy.[50] This influence can be proved by the role of these European funds in national public service development policies. According to the national partnership agreements, the share committed to funding welfare, education, and cultural services is relatively significant within the resources of the cohesion policy. In Hungary, the share of these funds is around 20% (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. ESI Funds and ESI Funds for welfare and educational objectives in Hungary 2007-2027 (based on the partnership agreements / national strategic reference framework)[51]

- 55/56 -

3. The Role of Conditionality as a Factor of Influence in the Field of Welfare Services

Conditionality has been part of EU law since the 1990s and has been embedded in various EU policies, including cohesion policy. These mechanisms are not new to EU legislation, as they have been applied to the Cohesion Fund; however, the 1994 Cohesion Fund conditionality was based on macroeconomic issues. During the 1990s, another form of conditionality was developed: the Copenhagen Criteria defined conditions and values for countries that would like to access European integration.[52] Based on the regulation, a two-tier conditionality system has evolved in the European Union.

The first general tier of the conditionality mechanisms is the rule of law conditionality. As I have analysed earlier, the rule of law conditionality mechanism was introduced by Regulation (EU, EURATOM) No 2020/2092 using a general regime of conditionality to protect the Union budget.[53] Thus, there were antecedents of the regulation. The role of budgetary tools in the field of the protection of the basic values of the EU has been mentioned earlier in the literature as well. It is highlighted by several papers that the countries that are the most problematic in the field of basic values and rule of law backsliding (especially Poland and Hungary) are major recipients of EU funds. The authors emphasise that Member States should follow the basic values of the EU as defined in Article 2 of TFEU. Therefore, countries with issues concerning the rule of law should be sanctioned. It has been clear that the procedure based on Article 7 of the TFEU is not sufficient, and it was highlighted that the issues associated with the rule of law could result in a threat to the EU budget because of the elevated risk of corruption and insufficient spending.[54]

This approach was developed, and in 2021, a second, sectoral tier conditionality mechanism was introduced by Article 15 of the framework regulation of the ESIF (2021-2027) by Regulation (EU) No 2021/1060. So-called horizontal and thematic enabling conditions have been introduced by the Framework Regulation. These rules could be interpreted as a supplementary element of the system of conditionality intended to protect the basic values of the EU. The enhanced conditionality mechanism of cohesion policy defines four horizontal enabling conditions: 1. effective monitoring mechanisms for the public procurement market, 2. tools and capacity for the effective application of State aid rules, 3. effective application and implementation of the Charter of Fundamental Rights and 4. implementation and application of the United Nations Convention on the rights of persons with disabilities (CRPD). Thus, it is not enough to fulfil the requirements of Regulation (EU, EURATOM) No 2020/2092; fulfilling

- 56/57 -

the horizontal enabling conditions is required to receive funds associated with cohesion policy. It is clear that these additional conditions are linked to basic values and especially to the principle of the rule of law. As a second element, the conditionality mechanism is even part of the protection of fundamental rights, which are considered a basic value of the EU, and because of EU membership in the CRPD, its application is required. The third and fourth horizontal enabling conditions are especially important in the field of welfare services. First of all, the values and principles of the European Charter of Fundamental Rights should be applied in the field of these welfare services. Thus, it became a binding requirement for those national administrations which would like to receive funds from the ESIF. Second, the welfare policies related to persons with disabilities are significantly influenced, and the application of the CRPD is a similar requirement because these principles should be applied directly. Therefore, national policies on care services for persons with disabilities have been transformed - community living should be strengthened, and the role of large care institutions should be decreased because Article 19, point c) of the CRPD favours community care services as a means of promoting the independent living of persons with disabilities.[55]

IV. Closing Remarks

There are different tools for harmonising systems in the European Union. The jurisprudential approach focuses primarily on the 'hard' judicial tools, legal harmonisation and the legislative powers of the bodies of the European Union. In the field of welfare services, there have been strong limitations on Union legislation because of the nature of these services: they are services of general interest. Therefore, in this field, national competences are dominant. It may be emphasised that there are different, partially legally regulated, but mainly policy-based toolkits for building a joint European framework. First of all, the OMC resulted in a partial harmonisation of welfare systems. Second, especially in the new Member States, which are the main recipients of the funds associated with Cohesion Policy, the ESIF (and partially, between 2021 and 2026, the RRF) may even be an effective tool for developing more harmonised welfare service systems. If we look at such influence, it may be mentioned that these 'soft' tools can be quite effective, sometimes even more effective than 'traditional' legal harmonisation.[56] My research indicates that it should

- 57/58 -

be emphasised that there is no direct legal harmonisation in the field of welfare services. Yet, certain tools still result in the indirect legal harmonisation of laws in these fields, such as the Open Method of Coordination and the cohesion policy of the EU, especially the conditionality associated with it. ■

NOTES

[1] Gøsta-Esping Andersen, 'Towards the Good Society, Once Again?' in Gøsta-Esping Andersen, Duncan Gallie, Anton Hemerijck, John Myles (eds), Why We Need a New Welfare State (Oxford University Press 2002, Oxford) 1-26) 2-4, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1093/0199256438.003.0001

[2] Source: EUROSTAT, COFOG <https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/en/web/main/search/-/search/dataset?text=COFOG> accessed 1 April 2025.

[3] Pierre Bauby, 'From Rome to Lisbon: SGIs in Primary Law' in Erika Szczyszak, Jim Davies, Mads Andanœs, Tarjei Bekkedal (eds), Development in Services of General Interest (T.M.C. Asser Press 2011, The Hague) 19-36, 21-24.

[4] A similar approach was applied by Rosalind Dixon. See Rosalind Dixon 'Comparing Consitutionally: Modes of Comparison' in Joshua Aston, Aditya Tomer, Jane Eyre Mathew (eds), Comparative Approach in Law and Policy (Springer 2023, Cham) 1-6.

[5] Kim Lane Scheppele, Dimitry Vladimirovich Kochenov, Barbara Grabowska-Moroz, 'EU Values Are Law, after All: Enforcing EU Values through Systemic Infringement Actions by the European Commission and the Member States of the European Union' (2020) 39 Yearbook of European Law 3-121, 7-10, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1093/yel/yeaa012

[6] Paul Craig, 'Subsidiarity: A Political and Legal Analysis' (2012) 50 (1) Journal of Common Market Studies 72-87, 74-76, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5965.2011.02228.x

[7] Paul Craig, Gráinne de Burca, EU Law. Text, Cases and Materials (3rd edn, Oxford University Press 2003, Oxford) 112-114.

[8] The European Court of Justice has produced several landmark cases on the interpretation of welfare services as services of general interest. In the Sint Servatius case - Case C-567/07 Minister voor Wonen, Wijken en Integratie v Woningstichting Sint Servatius, EU:C:2009:593 - it was mentioned by the European Court of Justice that social housing can be interpreted as a service of general interest, which is primarily regulated by national rules. Similarly, the Greek natural risk benefits which are provided as part of the national social policy benefits for farmers are considered similarly as services of general interest, and the primacy of national law was emphasised in this case by the European Court of Justice (Case C-355/00 Freskot AE v Elliniko Dimosio, EU:C:2003:298).

[9] Johan W. van de Gronden, 'Social Services of General Interest and EU Law' in Erika Szczyszak, Jim Davies, Mads Andanœs, Tarjei Bekkedal (eds), Development in Services of General Interest (T.M.C. Asser Press 2011, The Hague, 123-153) 124-127, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-90-6704-734-06

[10] For the impact on the EU rules of working time on costs of services see Ralf Rogowski, 'Sustainability and uncertainty in governing European employment law - the community method as instrument of governance: The case of EU Working Time Directive' in Jean-Claude Barbier, Ralf Rogowski, Fabrice Colomb, The Sustainability of the European Social Model. EU Governance, Social Protection and Employment Policies in Europe (Edward Elgar 2015, Cheltenham, UK, Northampton, MA, USA, 153-179) 158-162, DOI: https://doi.org/10.4337/9781781951767.00015

[11] Gøsta Esping-Andersen, The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism (Polity Press 1990, Cambridge, UK) DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/095892879100100108

[12] For more details on the different models and methodologies, see Wil Arts, John Gelissen, 'Models of Welfare States', in Francis G. Castles, Stephan Leibfried, Jane Lewis, Herbert Obinger, Christopher Pierson (eds), The Oxford Handbook of the Welfare State (Oxford University Press 2010, Oxford, 569-586) 572-580, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199579396.003.0039

[13] Gudrun Biffl, 'Diversity of Welfare Systems in the EU: A Challenge of Policy Coordination' (2004) 6 (1) European Journal of Social Security 33-59, 52-54, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/138826270400600103

[14] Catherine Barnard, The Substantive Law of the EU. The Four Freedoms (6th edn, Oxford University Press 2019, Oxford) 31, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1093/he/9780198830894.001.0001

[15] Sándor Illés, Éva Gellérné Lukács, 'Dual Nature of International Circular Migration' (2022) 19 (2) Migration Letters 149-158, 152-154, DOI: https://doi.org/10.33182/ml.v19i2.1554

[16] Axel Kokemoor, Sozialrecht (9. Auflage, Vahlen 2020, München) 24-25, DOI: https://doi.org/10.15358/9783800663903

[17] Marc Morsa 'The European Regulation on Social Security Coordination from the Perspective of the Belgian Authority' (2019) 1 Belgisch Tijdschrift voor Sociale Zekerheid 139-141, 139-157.

[18] Maximilian Fuchs (ed), Europäisches Sozialrecht (Nomos 2010, Baden-Baden) 43.

[19] Raimund Waltermann, Sozialrecht (9. Auflage, C. F. Müller 2011, Heidelberg) 47-48.

[20] Ralf Rogowski, 'The European Social Model and the Law and Policy of Transitional Labour Markets in the European Union' in Ralf Rogowski (ed), The European Social Model and Transitional Labour Markets (Routledge 2016, London, New York, 9-28) 9-11, DOI: https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315616384-2

[21] Case Graziana Luisi and Giuseppe Carbone v Ministero del Tesoro, EU:C:1984:35.

[22] Case C-159/90 The Society for the Protection of Unborn Children Ireland Ltd v Stephen Grogan and others, EU:C:1991:378.

[23] Tamara K. Hervey, 'If Only It Were So Simple: Public Law Services and EU Law' in Marise Cremona (ed), Market Integration and Public Services in the European Union (Oxford University Press 2011, Oxford, 179-250) 221, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199607730.001.0001

[24] Case C-158/96 Raymond Kohll v Union des caisses de maladie, EU:C:1998:71.

[25] Mark Dawson, New Governance and the Transformation of European Law (Cambridge University Press 2011, Cambridge) 171-172, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139017442

[26] Case C-120/95 Nicolas Decker v Caisse de maladie des employés privés, EU:C:1998:167

[27] Case C-159/91 and C-160/91 Christian Poucet v Assurances générales de France és Caisse mutuelle régionale du Languedoc-Roussillon, EU:C:1993:63

[28] Case C-264/01 AOK Bundesverband, Bundesverband der Betriebskrankenkassen (BKK), Bundesverband der Innungskrankenkassen, Bundesverband der landwirtschaftlichen Krankenkassen, Verband der Angestelltenkrankenkassen eV, Verband der Arbeiter-Ersatzkassen, Bundesknappschaft and See-Krankenkasse v Ichthyol-Gesellschaft Cordes; Case C-264/01 Hermani & Co; Case C-306/01 Mundipharma GmbH; Case C-354/01 Gödecke GmbH and Case C-355/01 Intersan, Institut für pharmazeutische und klinische Forschung GmbH, EU:C:2004:150.

[29] Case C-218/00 Cisal di Battistello Venanzio & C. Sas v Istituto nazionaleper l'assicurazione contro gli infortuni sul lavoro (INAIL), EU:C:2002:36.

[30] Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions Establishing a European Pillar of Social Rights COM/2017/0250 final.

[31] Ulrich Becker, 'Introduction' in Ulrich Becker, Anastasia Poulou (eds), European Welfare State Constitutions after the Financial Crisis (Oxford University Press 2011, Oxford, 1-23) 11, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780198851776.001.0001

[32] Martin Heidenreich, 'The Open Method of Coordination: a pathway to the gradual transformation of national employment and welfare regimes?' in Martin Heidenreich, Jonathan Zeitlin (eds), Changing European Employment and Welfare Regimes. The influence of open method of coordination on national reforms (Routledge 2009, London, New York, 10-36) 10-12, DOI: https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203878873

[33] Mary Daly, 'The dynamics of European Union social policy' in Patricia Kennett, Noemi Lendvai Baiton (eds), Handbook of European Social Policy (Edward Elgar 2017, Cheltenham, UK, Northampton, MA, USA, 93-107) 101-102, DOI: https://doi.org/10.4337/9781783476466.00014

[34] Dawson (n 25) 43-45 and Fabian Terpan 'The definition of soft law' in Mariolina Eliantonio, Emilia Korkea-aho, Ulrika Mörth (eds), Research Handbook on Soft Law (Edward Elgar 2023, Cheltenham, UK, Northampton, MA, USA, 43-56) 50, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.4337/9781839101939

[35] Fuchs (n 18) 44-45.

[36] Caroline de la Porte, 'Social OMCs: Ideas, policies and effects' in Bent Greve (ed), The Routledge Handbook of the Welfare State (Routledge 2013, London, New York, 410-418) 412-413.

[37] Daly (n 33) 102.

[38] Konstantinos Alexandris Polomarkakis, 'Social Europe: A Midsummer Night's Dream' in Paul James Cardwell, Marie-Pierre Granger (eds), Research Handbook on the Politics of EU Law (Edward Elgar 2020, Cheltenham, UK, Northampton, MA, USA, 224-246) 234, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.4337/9781788971287

[39] Fuchs (n 18) 45.

[40] Steven Ballantine, Lorenzo Mascioli, 'Spaces of subsidiarity: A comparative inquiry into the social agenda of Cohesion Policy' (2024) 58 (4) Social Policy and Administration 605-620, 607-610, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/spol.13006

[41] Stephen Weatherill, Law and Values in the European Union (Oxford University Press 2016, Oxford) 393-395, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199557264.003.0008

[42] Laurent Pech, Kim Lane Scheppele, 'Illiberalism Within: Rule of Law Backsliding in the EU' (2017) 19 Cambridge Yearbook of European Legal Studies 3-47, 7-10, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/cel.2017.9

[43] Case C-156/21 Hungary v European Parliament and Council of the European Union, ECLI:EU:C:2022:97.

[44] Julia Bachtrögler, Ugo Fratesi & Giovanni Perucca, 'The influence of the local context on the implementation and impact of EU Cohesion Policy' (2020) 54 (1) Regional Studies 21-34, 23, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2018.1551615

[45] Arjan H. Schakel, 'Multi-level governance in a 'Europe with the regions' (2020) 22 (4) The British Journal of Politics and International Relations 767-775, 769-771, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/1369148120937982

[46] John Bachtler, Martin Ferry, 'Cohesion policy in Central and Eastern Europe: is it fit for purpose?' in Gregorz Gorzelak (ed), Social and Economic Development in Central and Eastern Europe (Routledge 2020, London, New York, 313-344) 334-337, DOI: https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429450969-14

[47] Source: edited by the Author based on data from Eurostat national accounts 2014-2020 and <https://cohesiondata.ec.europa.eu/countries> accessed 1 April 2025.

[48] Karen Hermans, Johanna Greis, Heleen Delanghe, Bea Cantillon, 'Delivering on the European Pillar of Social Rights: Towards a needs-based distribution of the European social funds?' (2023) 57 (4) Social Policy and Administration 464-468, 467, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/spol.12879

[49] Juhász Gábor, Taller Ágnes, 'A társadalmi kirekesztődés elleni küzdelem az EU új tagállamaiban' (2005) 16 (6) Esély 23-63, 35-36.

[50] Beáta Farkas, 'Quality of governance and varieties of capitalism in the European Union: core and periphery division?' (2019) 31 (5) Post-Communist Economies 563-578, 567-570, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/14631377.2018.1537740

[51] Source: edited by the author, based on Hungarian partnership agreements and the 2007-2013 national strategic reference framework <http://pik.elte.hu/file/_j_Magyarorsz_g_Fejleszt_si_Terv___MFT_.pdf>; <https://www.palyazat.gov.hu/download.php?objectId=52032; https://www.palyazat.gov.hu/partnersegi-megallapodas> accessed 1 April 2025.

[52] Christophe Hillion, 'The Copenhagen Criteria and their Progeny' in Christophe Hillion (ed), EU Enlargement: A Legal Approach (Hart Publishing 2004, Oxford, UK, Portland, OR, USA, 1-22) 7-11.

[53] Pech, Scheppele (n 42) 7-9.

[54] Pech, Scheppele (n 41) 24-28 and Antonia Baraggia, Matteo Bonelli, 'Linking Money to Values: The New Rule of Law Conditionality Regulation and Its Constitutional Challenges' (2022) 23 (2) German Law Journal 131-156, 140-142, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/glj.2022.17

[55] Andrea Broderick, Silvia Favalli, 'The Transition from Institutional Care to Community Living in the EU: Lessons Learned in the Shadows of COVID-19 Pandemic' in Philip Czech, Lisa Heschl, Karin Lukas, Manfred Nowak, Gerd Oberleitner (eds), European Yearbook on Human Rights 2021 (Intersentia 2022, Cambridge) 231-258, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/9781839702266.013, 242-246 and Áine Sperrin, 'A Disability Rights Approach to a Constitutional Right to Housing' (2023) 3 (1) International Journal of Disability and Social Justice 80-95, 85-86, DOI: https://doi.org/10.13169/intljofdissocjus.3.1.0080

[56] A similar result is shown by Nikolaos Voulvoulis, Karl Dominic Arpon, Theodoros Giakoumis, 'The EU Water Framework Directive: From great expectations to problems with implementation' (2017) 575 Science of the Total Environment 358-366, 363, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.09.228

Lábjegyzetek:

[1] The author is (PhD, dr. habil., DSc.), Professor at Eötvös Loránd University (ELTE), Faculty of Law, Budapest, Hungary, a Professor at the University at Maria Curie-Skłodowska University, Faculty of Law and Administration, Lublin, Poland, and Research Professor at HUN-REN Centre for Social Sciences, Institute for Legal Studies, Budapest, Hungary (e-mail: hoffman.istvan@ajk.elte.hu). This article is based on the investigations of the research project 'Restricting the legal capacity of adults in Hungary' No. OTKA FK 132513, supported by a research grant from the Hungarian National Research, Development and Innovation Office. The research was supported by the COST Action CA20123 IGCOORD, as well.