Klára Kerezsi[1]: Human Safety in Central-Eastern Europe (Annales, 2004., 101-120. o.)

In the new Europe, the concept of security has been broadened from traditional notions of national (military) security to wider concepts of international security, and has necessitated the striking of a new balance between the economic, political and 'order-maintenance' requirements. In the processes of democratization and reconstruction, crime is significant. Many member states of the EU are concerned with the possibility of increased criminal activity originating from Central-Eastern European countries and targeting Western European countries as their markets; especially in relation to drugs, illegal immigration, prostitution and economic crimes. However, crime is significant not only in economic terms (the actual cost of the crime, the increasing costs of criminal justice and penal sanctions), but also in its social costs, which contribute to social exclusion and fragmentation.[1]

It is impossible to determine all factors influencing the dynamics of crime development as well as factors causing crime whole in the CEE region. Human security[2] is comprised of a multitude of different risk arenas including economic, social, and political risks. Usually these are attributed primarily to crime but in the overall notion of security these risks go far beyond criminality. This dimension is generally associated with individual perceptions and fears.

The following outline of the situation in CEE countries tries to explore the cross-linked impact of crime problem with several other issues such as poverty, racial discrimination, youth future, that are relevant to human safety, human rights and sustainability of the transition process.

- 101/102 -

Political and economic transition

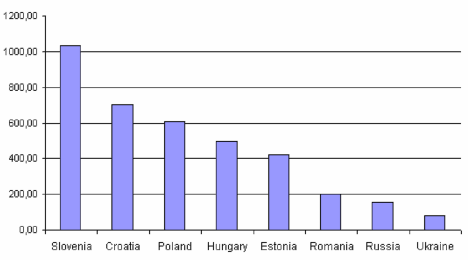

During the political transition much higher changes took place in the social structure of the Central and Eastern European countries than the public had expected. Most of the countries in the region have paid and are still paying a very heavy human and social cost during this transition. The transition had at least three types of consequences: there were such effects that were absolutely non-waited, others that were waited to be shorter, and some other effects that were waited to be positive but had a negative consequence instead. People in Central-Eastern Europe were enthusiastic about the possibility of a new opening, because they desired for a new moral system, for political freedom and a market economy that should solve the inconveniences of the previous 'shortage economy' without the disadvantages of the unrestricted market. They believed that the responsibility of the state would remain untouched. But this seemed to be an illusion. No one could have predicted the 'human costs' of this process. Now, three-quarters of a public poll's respondents in Poland, Romania and Slovakia evaluate the economic situation of their country as bad. The same opinion is expressed by less than half of the Russians, approximately two-fifths of the Czechs and only slightly more than a quarter of the Hungarians.[3] The data somehow justify these views: for instance the difference between gross wages in Slovenia, and in Ukraine, is roughly 15 fold. In Ukraine wages are similar to those in Pakistan, while in Slovenia wages match South African and Portuguese levels.[4] In 2001, the estimated average monthly labour cost level was highest in Slovenia, at estimated $1,034 per month. Croatia and Poland follow it. Other advanced Central European and Baltic economies have average monthly labour costs ranging from roughly $300 to $500 per month, while Russia, and Bulgaria have far lower labour costs of approximately $150. Ukraine has the lowest labour cost, at around $80.[5]

- 102/103 -

Estimated average monthly cost of labour in the year 2001, in USD at current exchange rates

By Western observers Central and Eastern Europe countries often perceived as homogenous regarding economic development. Despite the similarities in their economic systems and very high rates of human capital development, the economic characteristics of the Central and Eastern European countries varied widely. According to the progress took place in economic and political reforms of the CEE countries, two broad groups can be distinguished:

• The 'leading reformers' group, which consists of middle-income countries of democratic capitalism of the Central Europe and Baltic region.

• The group of 'less advanced reformers', which includes mainly lower- and lower-middle-income countries have emerged from former Soviet Union and some others in the region, where both capitalism and democracy are still immature and sometimes heavily distorted.

During the initial decade of transition, the first group represented a much better economic and social record in any respect than the second one.

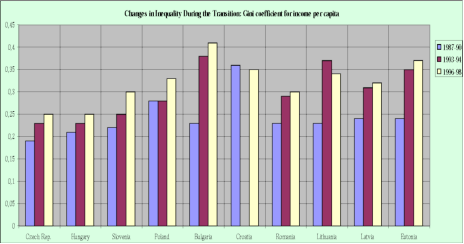

The differentiation involves not only the economic but also the social dimension. The GINI coefficient increased in all post-communist countries during transition what should be considered as a 'normal' effect of departing from communist egalitarianism towards a market determined income structure. However, this increase was on average much higher, for less advanced reform-

- 103/104 -

ers than for the transition leaders. Obviously, most of necessary reform steps in the economic sphere are considered as socially painful, at least in a short term.[6]

Changes in Inequality during the Transition: GINI coefficient for income per capita

Source: World Bank (2000): Transition After a Decade. Lessons and an Agenda for Policy, first draft

Social divisions and social disintegration in Central and Eastern Europe are growing rapidly, and the gap between winners and losers of the transformation process becomes constantly greater. The loss of security (and the growth of fear of crime) is closely connected to the unemployment, exclusion and lost of personal future for some age cohorts or social strata. The following social groups paid a higher prize than the average for the transition: families with children (especially single parent families and the families with many children); the elderly (with low pension); the unskilled and unemployed persons. Prejudices appeared in an open form after the country's political transition. The majority of Romas were losers in the transition.

Except for a few countries in Central and Eastern Europe that have not seen a dramatic drop in standards of living, most inhabitants of the former socialist countries have lost their welfare net (a core of the socialist system), without gaining the benefits of capitalist system. Widespread impoverishments, particularly in the Soviet successor state, and the feminisation of poverty have resulted.

- 104/105 -

Strong social causes are in the heart in this rapid rise in crime. The transformation in the direction of free market economy resulted in the processes, which excluded substantial parts of Central and Eastern European societies from participation in the benefits of this type of economy. This gives ground to growing influence of various populist and extremist groupings. During the transition of the post-Soviet countries, we can find 12 countries where the democratic movement was not succesful. Among these countries are Russia, Ukraine, Belorus, Georgia, Serbia, Macedonia and Romania. In these countries the existing presidental systems show us that the failure of the democratic movement has produced strong presidental frame. The relative success stories of Poland, Hungary, the Czech Republic and the Baltic states should not obscure what is going on in the rest of the region.

The consequences of growing polarisation of society: Social Exclusion

Social exclusion has recently become a popular and widely used concept. In recent attempt by the EU to monitor social inclusion, there were defined some key areas: education, employment and unemployment, health, housing, access to essential services, financial precariousness, and social participation.

During last years the unemployment in the accession countries was higher than in the EU-15, and actually increased by 2.5 percentage points from 1999 to 2003.

Harmonized unemployment rate, in%[7]

| 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | |

| EU-25 | 9.2 | 8.8 | 8.5 | 8.8 | 9.0 |

| EU-15 | 8.7 | 7.8 | 7.4 | 7.7 | 7.2 |

| ACC | 11.8 | 13.6 | 14.5 | 14.8 | 14.3 |

| Czech Rep. | 8.6 | 8.7 | 8.0 | 7.3 | 7.6 |

| Estonia | 11.3 | 12.5 | 11.8 | 9.5 | 10.1 |

| Latvia | 14.0 | 13.7 | 12.9 | 12.6 | 10.5 |

| Lithuania | 11.2 | 15.7 | 16.1 | 13.6 | 12.7 |

| Hungary | 6.9 | 6.3 | 5.6 | 5.6 | 5.8 |

| Poland | 13.4 | 16.4 | 18.5 | 19.8 | 19.2 |

| Slovenia | 7.2 | 6.6 | 5.8 | 6.1 | 6.5 |

| Slovakia | 16.7 | 18.7 | 19.4 | 18.7 | 17.1 |

- 105/106 -

A strong impact on these figures is made by the data for Poland, where unemployment has risen substantially. The rate for Poland grew from 13.4% in 1999 to 19.2% in 2003. Other countries also showed high values in this period, e.g. Estonia, Lithuania, Latvia and Slovakia, where unemployment rates reached values above 10%. Developments over time were, however, far from uniform. Relatively low unemployment is observed in Hungary and Slovenia, where values were lower than the average EU-15 unemployment rate.[8] Despite the recent return to positive growth in most Central-Eastern European countries, the average rate of unemployment at the end of 1999 was at its highest level since the beginning of the transition (close to 15%, or some 7.6 million people).[9] Some disadvantageous symptom is also striking recently. By the first results of the year of 2004: the total registered unemployment rate was 19,5% in Croatia.[10] At the end of February 2004 the registered unemployment rate reached 10.9% in Czech Republic.

Two main processes contribute to social exclusion: (a) high unemployment (especially long-term unemployment) and job precariousness for people who were previously fully integrated into the society's main institutions, and (b) difficulties, in particular for young people, in entering the labour market and enjoying both the income and the social network associated with it. Strength of the links are between the employment situation and other dimensions of life: family, income, housing, health, social networks, etc. Those people, who are trapped in the bad segments of the labour market or excluded from it, suffer from the risk of becoming excluded from society.[11]

Rate of unemployment by selected age groups in Czech Republic

| Total | 1993 | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | |

| 4,3 | 4,3 | 4,0 | 3,9 | 4,8 | 6,5 | 8,7 | 8,8 | 8,1 | 7,3 | ||

| Age group: | 15 to 19 | 11,8 | 13,2 | 13,1 | 13,3 | 16,5 | 25,1 | 31,8 | 33,6 | 37,3 | 35,8 |

| 20 to 24 | 6,3 | 6,2 | 5,6 | 5,1 | 6,4 | 9,1 | 13,6 | 14,2 | 13,7 | 13,5 | |

| 25 to 29 | 5,3 | 5,7 | 5,4 | 5,0 | 5,9 | 7,5 | 9,7 | 9,4 | 9,1 | 7,9 | |

- 106/107 -

The number of young people in social and economic difficulty with a major risk of social exclusion increases all around in the region. As Kauko Aromaa pointed out a general possible trend for the entire continent for the coming decade is the growing polarisation of society, increased urbanisation, leading to greater isolation and fear of crime, and drug trafficking and organised crime would be the major threat.[12] As Jock Young formulated it recently 'transition from modernity to late modernity can be seen as a movement from an inclusive to an exclusive society'.[13] Or better to put it in this way in connection with the CEE countries: transition from modernity to late modernity has the meaning of taking part in processes of 'global inclusion' and 'local exclusion' at the same time. These parallel processes might be characterized mostly by the changing situation of Roma population. Out of 6 million Romas living in the European region four-fifths of them live on less then 4.30 USD per a day. The Roma's poverty and their social marginalization jeopardize the results of the economic development and social cohesion of the CEE countries. With the end of communism in Eastern Europe, conditions for Roma have actually worsened. Always on the bottom of the social and economic ladder, Roma were helped by socialist education and employment policies. Now, Roma have fallen back into the class of those 'last hired and first fired', despite some governmental initiatives to strength their living circumstances.

What is more important is the growing tendency for exclusionary crime control policies that coincides with growing problems of social exclusion in other areas of social life. For this reason with reference to social causes of crime one can find data in the countries' Human Development Reports. In respect of the fact of changing social conditions and the nature of criminality in the CEE countries the examination of criminality should take into consideration the widest social context. There are two basic indicators that show the deep drawback of an area: the GDP rate per capita, and the changes of unemployment rate. As it shows the case of Hungary, most of socially and economically deprived areas are suffering both from high unemployment and from economically underdevelopment. By comparing geographical distribution of registered crime rate to the division of GDP rate per capita, those areas have higher registered property crime rate, which have higher GDP rate, too. Nevertheless the number of registered offenders is much higher and concentrated in the economically deprived areas.

- 107/108 -

Whether we like it or not, it is indisputable that the unemployment is one of many factors affecting the crime rate. The public polls always reflect the importance of the level of unemployment rate for the public. For instance the Lithuanian respondents consider fighting unemployment as the most important tasks of their Government.[14] It is a well-known fact that the population's sense of security is influenced - in addition to crime figures - by factors such as worsening living standards, greater unemployment rates, or the lack of future prospects.

The circles of criminality: the traditional and the organized crime

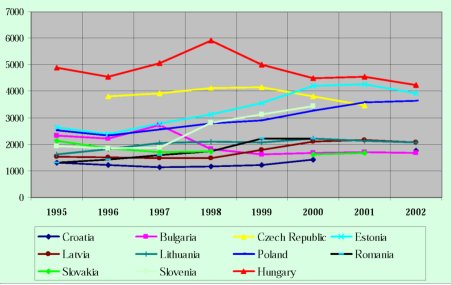

Last decade the public in the region had to face the boom in crime which Western Europe had two decades to get used to. Crime rates at least doubled in all post-communist states.[15] The main property-related crimes include shoplifting, pick pocketing, burglary, car-theft or vehicle break-ins and vandallism. Increasing crime rates have put law enforcement organisations to the test in CEE countries: parallel to the rise in crime, clear-up rates have dropped drastically all over the region.

Fortunately the upward trend, which began in 1990, seems to be reversed and the crime rates in general are getting to stabilise in the region in the last half decade. Of course there are some exceptions. Crime rate in Poland and Czech Republic stabilised, in Estonia started decreasing only in 2001. However the number of registered criminal offences stabilising on a tripled or quadrupled level of the number of criminal offences registered 20 years ago.

- 108/109 -

Crime rate per 100,000 populations in CEE countries (Interpol's or countries' official data)

The continued stagnation of crime or a moderated decline trend is especially true with property crimes. This trend might be influenced by a set of adopted situational crime preventive measures. However in Slovenia the highest rise was seen in minor property offences in the latest years. In the last two years (2000-2001) and in 2002 crime in the Czech Republic moderately increased or stagnated. However if we take into consideration the fact that some previous criminal acts were transferred into the category of administrative offenses we can rather talk about an increase in crime. (According to the data the Czech police recorded about 75,000 administrative offenses, which were in 2001 considered to be criminal offences.)[16] It should also pay attention to the quick increase of crimes against public order and security thouroughout the region. The statistics show a continuous rise in cases of disorder in urban areas, as well as the numbers of persons commit hooliganism.

- 109/110 -

Despite of a stabilising trend in property crime in the CEE region, there is a tendency of increase of more serious types of crimes against property, especially burglary and robbery. Between 1990 and 1996 the number of robberies grew by 418 per cent in Bulgaria, 961 per cent in Lithuania, and 119 per cent in Romania. In the Czech Republic, the number of robberies reached almost 5,000 offenses in 1999. Robbery had become an urban phenomenon by the turn of the millennium, and was being committed with greater violence, brutality and harm. In Hungary the number of armed robberies (banks, post offices) has risen faster than in any other category.[17] Most of robberies committed in the region take place in bigger cities, especially in the capitals. For instance, robberies committed in Prague represent almost 40% of the whole number of robbery committed in Czech Republic.

Certain stagnation in the number of crimes against property was accompanied by an increase in the number of burglaries of family houses and flats, and a quite considerable increase in burglaries of shops, thefts of cars and things from cars was recorded. The officially recorded crime rates do not provide a full picture of crime in CEE countries, either. A high level of under-reporting could be found in Poland: in relation to car crime approximately a half of all thefts from cars went unreported. It appeared that only 21.4 per cent of all property crime was reported to the police; low levels of reporting were also apparent in relation to burglary.[18] Victimization rates are relatively high, particularly for car-related crime, thefts of personal property (including pick-pocketing), and robbery. Recovery of stolen cars was the lowest observed, with fewer than half of victims getting their car back.[19]

The number of violent crimes per 100 thousand of population has also risen in CEE region; however, the rate of violent crime has risen more slowly than the rate of crime against property, in the last two decades. In those CEE countries where violent crimes were up, homicide nevertheless remains a rarity. However, some country may be more lethal than the others: homicide rate in Estonia and in Latvia is much higher, than in the other CEE countries. For instance homicide for every 100,000 residents in Tallinn, Estonia was 11.23 in 1999. (The European Union average is 1.70 homicides per 100,000 residents from 1997 to 1999.) A large number of homicides are either domestic (men murdering female partners), or the resolution of disputes between males.

- 110/111 -

From the middle of 90s the data indicate a steady and growing number of drug-related crimes. The calming of the situation in the former Yugoslavia is reviving the 'Balkan Route' - a route that runs through many CEE countries. Slovakia and Hungary have also become an important part of the 'Balkan Route' for drug smuggling. These new crimes reflect the current social and economical changes. Therefore it might be predicted that violent and drug-related crimes will not fall in the region in the long run. According to an international survey conducted in twelve European countries in 1999, drug abuse is most common among the unemployed.[20] (The survey is not concerned whether drugs abuse is the cause or the effect of unemployment.) As regards drug-related crimes in Hungary, it is less the frequency than the rate of growth that is worrying. The number of drug-related crimes that became known rose from 34 to 3930 between 1990 and 2001, and to 4779 by 2002. 130 persons committed drug-related crimes in 1994, whereas the figure in 2002 was 1786. Cannabis products (marihuana, hashish) are becoming increasingly widespread, as are amphetamines such as Speed and Ecstasy. Ninety percent of the individuals caught using these drugs were under thirty. The number of drug-related deaths was 47 in 1997, 31 in 1998, 42 in 2000, and 40 in 2001.[21] Interpol said drug turnover on the Ukrainian market was worth $ 60 million. Among the social class of users 65% were unemployed, 21% manual workers and 5% high school or college students. A total of 90% were under 30 and 40% were under 18.[22]

The most worrying symptoms in the region are that fact, which the first contact with drugs usually comes between the ages of 13 and 16. About 35% of secondary school students admit to having taken drugs, with the largest proportion being among children of educated parents. By the age of 25 about 50% of people have tried drugs and there is a worrying rise in the number of young girls doing so. According to the survey carried out in the Czech Republic, 71% of respondents are very or quite anxious about drugs and the spread of drug addiction. To the question of whether the police should monitor, investigate and prosecute marijuana smoking and its being offered to peers, 46% of respondents answered 'yes always', 23% answered 'yes, if the a victim minds this kind of crime', 23% of respondents stated that they would rather the police did not, and 8% answered 'absolutely not'. The respondents were also anxious about the possibility of their child (age 5-17 years) becoming a drug addict.

- 111/112 -

The widest activities of organized crime in the CEE region are represented by drug production, smuggling and distribution. Behind them there are other fluctuating activities, e.g. corruption, money laundering, CD falsification and video duplicating, violence and murder, thefts of objects of art (belonging specially in the first half of the nineties to the most widespred ones), illegal debt recovery, tax, banking and customs frauds, extortion, trafficking in arms. Looking ahead to coming years, the most widespread organized crime activity might become the drug trafficking, followed by violent crimes, illegal migration, organized prostitution, and money laundering.

Difficult social, political, and economic transitions in Central-Eastern Europe have sometimes resulted in acute tensions and uncertainties that find expression in xenophobia and racism. Often the Roma are the first targets of such social discontent. Three broad categories of human rights violations are affecting Roma: racially motivated violence by skinheads and others; violence by law enforcement officers; and systematic racial discrimination. The incidence of hate crimes is widespread. From Bulgaria to the Czech Republic, to Yugoslavia, young toughs who hold extremist views commit gruesome crimes of racial hatred against Roma victims.[23]

Victimization and fear of crime

The results of victimization survey and public polls showed that inhabitants of transition countries feel a sense of insecurity. Increasing crime rate and the appearance of new commercial media with it's 'what bleeds that leads' - approach played a significant role in growth of fear of crime in the region. As a consequence, there is an inconsistency between fear of crime and the actual incidence of crime.

According to a victim survey conducted in Czech Republic (2003 Victimisation and Citizens' Feelings of Being Safe) in 2002, 26% of persons interviewed were directly affected by a crime (2001: 23%, 2000: 25%, 1999: 24%, 1998: 19%). In 2002 56% of affected respondents reported the crime to the police (2001: 56%, 2000: 61%). The most frequently mentioned offences were thefts, committed in the street, at work, on public transport vehicles or in similar public facilities (2002: 13%, 2001: 14%). The thefts from cars and damage to cars occurred 12% of respondents (2001: 12%) and the rate of burglaries was 11% (2001: 9%).[24]

- 112/113 -

In 2000, 27% of people were victims of crime at least once in Slovenia. In Ljubljana the figure is 40% and in the rest of Slovenia 25%. 10% of persons were victims of consumer fraud in Slovenia, which is the highest percent of all crimes. In Ljubljana most people were victims of car vandalism (12%).[25] In Slovenia a survey on socio-demographic and socio-psychological dimensions of fear of crime was conducted nationwide in 2001/2002.[26] The results show that 36.4% of the studied sample (N=1760) expresses fear of crime. According to the results of the National crime victim survey, in 2001, men feel safer at home than women do: 72% of men and 52% of women feel very safe. After dark, men feel safer in the area than women do: 48% of men and only 23% of women feel very safe. Only 10% of men feel a bit unsafe or very unsafe compared to 29% of women.

According to the police data, in Poland the number of reported crimes per 100,000 inhabitants is lower than in most Western European countries. It is also lower than in the Czech Republic and Hungary. In Poland the public polls indicate that the fear of crime is widespread in the country, and this is almost tripled between 1980s and early 1990s. However, when the repondents were asked about crime in their neighbourhood, the perceived fear of crime grew relatively little and was rather stable. Nevertheless, the level of perceived threat to personal safety may be described as high: in the years 1996-2001, approximately two-thirds of the respondents were afraid of becoming victims of a crime (including 15% to 21% of those who were 'very' afraid). The respondents were even more concerned about the safety of their families. According to key findings of the 2000 International Crime Victims Survey, victimization rates in Poland are relatively high, particularly for car-related crime, thefts of personal property (including pick pocketing), and robbery. Recovery of stolen cars was the lowest observed, with fewer than half of victims getting their car back - a different pattern from the dominant one. At present, 66% of the public poll respondents are afraid that they may become victims of crime, including 14% of those who are 'very much' afraid. The fears about the family are stronger, 74% of the respondents have such fears, including 24% of those who are afraid 'very much'. If we combine these two questions, we will see that a quarter of all respondents feel strong fear and slightly more than a fifth are free from such fears.[27]

- 113/114 -

According to the results of a public poll on feeling of safety in the Czech Republic, Hungary and Poland, a large majority of respondents (over 72%) felt safe in the locality of respondent's residence.[28] It is the Czechs whose definite majority (83%) said that they were not afraid of any danger in their neighbourhood; however, the safety of the country as a whole was evaluated much worse. Less than half of the Hungarians and one-third of Poles believed that their country was safe. Most Lithuanians (59%) declared that they did not feel safe in their country. Among the societies participating in this survey, the Russians' opinions were clearly the most negative: only a quarter (25%) declared that they generally felt safe, while most respondents expressed the opposite opinion.[29]

In Hungary according to the data of police-registered crime 3% of the population was directly affected by a crime in 2003. In the same year the National Institute of Criminology conducted a victim survey on a nationwide representative sample. The data show that 12% of the adult respondents were directly affected by crime. The survey data indicate that approximately 10% of the adult population feel unsafe or completely unsafe.[30]

How safe is your living environment?

| Frequency | Percent | Valid Percent | |

| Do not know | 32 | ,3 | ,3 |

| Not at all | 288 | 2,9 | 2,9 |

| 2 | 529 | 5,3 | 5,3 |

| 3 | 2461 | 24,6 | 24,6 |

| 4 | 4257 | 42,5 | 42,5 |

| Completely | 2449 | 24,4 | 24,4 |

| NV/A | 4 | ,0 | ,0 |

| Total | 10020 | 100,0 | 100,0 |

- 114/115 -

What is your opinion about the safety of Hungary?

| Frequency | Percent | Valid Percent | |

| Do not know | 253 | 2,5 | 2,5 |

| Very bad | 809 | 8,1 | 8,1 |

| 2 | 2435 | 24,3 | 24,3 |

| 3 | 5201 | 51,9 | 51,9 |

| 4 | 1187 | 11,8 | 11,8 |

| Very good | 96 | 1,0 | 1,0 |

| NV/A | 39 | ,4 | ,4 |

| Total | 10020 | 100,0 | 100,0 |

Tremendous growth in numbers of private security can be seen as a consequence of new anxieties concerning personal and property safety. In the region the private security firms employed more people than the countries' Police Forces did, which indicative somehow the 'privatisation process of penal justice'.

Increased punitiveness: increasing imprisonment rate

The European Sourcebook found no relationship between the size of the prison population in a country and the level of recorded crime.[31] During the years 2000-2002 one can speak about real explosion of the prison population in the region. The 'new penal wave' has been reinforced by the constantly high level of criminality, public's expectations towards harder punishments and the increase of the effectiveness of the work of police, prosecutors office and court system. It accompanied by some changes in sentencing policies of the courts, and in tightening up of the parole policies.

In Croatia among the type of criminal sanctions, the most frequent were imprisonments (77.5%), followed by fines (17.8%) and judicial admonitions (2.7%). In Estonia the courts impose prison sentence to 22-24% of convicted offenders, and further 43-45% to conditional imprisonment. Imprisonment up to 2 years has been imposed to 70.9 per cent of all the persons sentenced to imprisonment.[32]

- 115/116 -

The tougher court practice is greatly influenced by the legislators in the CEE countries. Firstly, the Penal Codes in CEE countries more or less generally prescribe imprisonment as a type of punishment for the majority of offenses. In Lithuania, for example there are 396 sanctions in the Penal Code, among them 364 sanctions meant some kind of deprivation of liberty. Similarly, the Hungarian Penal Code prescribes more than 550 punishment items; however there are only 11 crimes of which fine can be imposed exclusively. In 1999, a new amendment of the Penal Code introduced a special kind of legal sentencing guidelines. It required from the judges, when they were imposing prison sentence its term should not be shorter than the medium term of imprisonment prescribed by the Penal Code punishing that crime. Although it was a shortlived legal regulation, it was expelled by another amendement of the Criminal Code.

As Krajewski described the situation, after a relatively short period of expert dominated crime control policies and liberal reforms of criminal law and criminal justice system ended or their progress was halted. Certain concepts and ideas of American crime control policies became increasingly popular among politicians and the media also in Central Europe. 'Zero tolerance', 'three strikes and you are out' and similar slogans are often used as examples of successful policies which brought about not only political success for their creators and enforcers, but 'solved' crime problem in the USA and provided security for the citizens.[33]

In most countries in the region, prison populations are well above the levels in the rest of Europe and are growing. Overcrowding seems to have become significantly worse since 1994. Most prison systems have high rates of pre-trial detention compared with the rest of Europe, and pre-trial detainees in all but four countries are given no more than one hour outside their cells each day. Many prisoners have an alcohol problem in almost three-quarters of the prison systems. There has been progress in recent years in the extent to which prisoners are enabled to be in contact with the outside world. The availability of employment for prisoners has become worse in recent years.[34]

- 116/117 -

During the past ten years, the prison population has steadily increased in Hungary. Prisons are incredibly overcrowded: the capacity of the prisons is 10,799 but there were 17,514 inmates on February 2002. The average period served by an inmate became longer both in remand and sentenced cases. 49% of prisoners were first offenders; and 40% of them came from the Northeast region of Hungary.

There is an inbalance between responsibility, and needs for restoration and reintegration in the existing criminal justice system in the region. At present, it would appear that there's perhaps too much emphasis on responsibility, without enough attention to restoration, and re-integration. However a new trend is also emerging in the criminal justice field, which is slowly reinforcing the alternative solutions to the traditional regulatory system of criminal justice (e.g. diversion, mediation, compensation, conflict resolution). The example might be the new Hungarian Criminal Procedure Act (has been in force from 1 July 2003), which enables cases to be discontinued, with compensation ordered for the victim or the public instead. The Czech Probationary and Mediation Service (PMS) dealt with 29,291 new cases in 2002. PMS is responsible, together with the municipal councils, for implementing the community service.

Prevention of crime - Criminality prevention

Safety and security as a central dilemma in the CEE countries appears a bit different like in the West. The unfavorable socio-economic conditions, low living standards and the situation without a clear value system may set a person into motion a negative trajectory that may result in crime, violence and problems with alcohol and drugs. Therefore all possible prevention policies should include the reduction of risk factors and the development of protection factors.

Since the early 90s the Western countries have started to pay enough attention to the problems of crime prevention. From the middle of 1990s one can trace similar development in some of the Central-European countries, too. In Slovenia for instance the National Social Welfare Programme requires co-ordinated approach in crime and violence prevention and protection of people at risks. A national programme for crime prevention is in prepapation. It also covers the field of prevention of violence and co-ordination in the field of crime and violence prevention. The Ministry of Labour, Family and Social Care financially supports 72 local preventive programmes. The Latvian Crime Prevention Council was established in 1993, the Hungarian one in 1995, and in the Czech Republic in 2000. In accordance with the community crime prevention approach, the Hungarian national strategy aims at a quantitative reduction of crime and a qualitative improvement of citizen's perception of security. It

- 117/118 -

identifies five priority areas: prevention and reduction of juvenile delinquency; improvement of urban security; prevention of violence within the family; prevention of becoming victimized and creating proper means to help victims of criminal acts; and prevention of re-offending.

From the two basic features that all crime prevention programmes must address are the social development and opportunity reduction. Promotion of social cohesion most likely refers to conflict resolution, reconciliation, and rebuilding the 'social fabric' of our society through the promotion of institutions that are sources of 'social capital'.

Resümee - Humansicherheit in Ostmitteleuropa

Die Ostmitteleuropäische Region ist aus Sicht der Sicherheit nicht nur ein geografischer, sondern auch ein politischer Begriff. Im Zusammenhang mit dem EU-Beitritt wurden die Befürchtungen bezüglich der zunehmenden Aktivität der Straftäter in Osteuropa zum Ausdruck gebracht, insbesondere im Zusammenhang mit dem Drogenhandel, der illegalen Migration und der Prostitution, oder im Bereich der Wirtschaftskriminalität.

Die Kriminalität ist zum Einen eine Wirtschaftsfrage (zum Beispiel der durch die Kriminalität verursachte Schaden, die zunehmenden Kosten der Strafrechtsprechung und des Strafvollzugs), und zum Anderen ein Problem, das mit erheblichen Kosten und gesellschaftlichen Folgen einhergeht. Der Verfasser der Studie untersucht die Kriminalität in den ostmitteleuropäischen Staaten anhand von Erscheinungen, die eng mit der Sicherheit der Menschen, der Durchsetzung der Menschenrechte und der Nachhaltigkeit des Demokratisierungsprozesses verbunden sind, wie Armut, Arbeitslosigkeit, Diskriminierung oder Zukunft der Jugend. Der Sicherheitsschwund (zunehmende Angst vor Kriminalität) in den Ländern der Region hängt eng mit der Arbeitslosigkeit, der gesellschaftlichen Ausgrenzung und dem Zukunftsverlust bei einigen gesellschaftlichen oder Altersgruppen zusammen.

- 118/119 -

Im Zuge des Systemwechsels kam es in der Struktur der osteuropäischen Gesellschaften zu Änderungen, die um Größenordnungen größer waren, als mit denen die Menschen gerechnet hatten. Die Menschen sehnten sich nach einer neuen moralischen Ordnung, nach politischen Freiheitsrechten und nach der Marktwirtschaft, welche die Mangelwirtschaft ablösen sollte. Mit den ungünstigen Folgen der neuen Wirtschaftsordnung hat man aber nicht gerechnet. In den osteuropäischen Staaten nahm die gesellschaftliche Desorganisation zu, und die Kluft zwischen den Gewinnern und den Verlierern des Systemwechsels wurde immer tiefer. Der Verfasser analysiert die für die einzelnen Länder kennzeichnenden gesellschaftlichen Nachteile anhand der Kennzahlen der Arbeitslosigkeit und des GDP pro Kopf.

In den meisten Ländern der Region konzentriert sich die Kriminalitätskontrolle auf die Bekämpfung der organisierten und der grenzüberschreitenden Kriminalität, und sie widmet wenig Aufmerksamkeit der Behandlung der herkömmlichen Kriminalität, die den Alltag der Menschen stark beeinflußt.

Trotz der Tendenz einer Stabilisierung bei den Vermögensdelikten in der Region ist eine Zunahme der schwereren Formen der Vermögensdelikte insbesondere der Wohnungseinbrüche und der Raubdelikte zu beobachten. Der zügige Anstieg von Delikten gegen die öffentliche Ordnung ist eine neue Erscheinung. Obwohl auch die Häufigkeit der Gewaltstraftaten in der Region eine zunehmende Tendenz aufweist, blieben Tempo und Maß der Zunahme hinter denen der Vermögensdelikte zurück.

Die Zahl der offiziell erfassten Straftaten gibt kein vollständiges Bild über die Entwicklung der Kriminalität, auch in den osteuropäischen Ländern nicht. Aus diesem Grund analysiert der Verfasser die Zusammenhänge zwischen den Angaben der Kriminalstatistik und den über die Ordnungswidrigkeiten in den einzelnen Ländern der Region. Die Studie geht auf die Ergebnisse der Opferuntersuchungen in der Region - zum Beispiel auf die in Ungarn 2003 durchgeführte Forschung -, die eine große Häufigkeit der Angst vor Straftaten belegen.

Für die Länder der Region ist ein kontinuierlicher Anstieg der Verhängung von zu verbüßenden Freiheitsstrafen und für die Gefängnisse eine Überfüllung typisch. Nach der Analyse stellt der Verfasser fest, daß im System der Strafrechtspflege in den Ländern der Region eine Unausgewogenheit zwischen der Geltendmachung der Verantwortlichkeit, dem Anspruch der Opfer auf Restitution bei Schäden und der Notwendigkeit der Reintegration.

- 119/120 -

Der Verfasser schildert auch die verstärkte Vorbeugung von Straftaten, die sich in der Einsetzung von Regierungskommissionen zur Kriminalitätsvorbeugung und - in einigen Ländern - in der Schaffung einer nationalen Strategie zur Vorbeugung von Kriminalität manifestiert. Zugleich stellt er fest, daß die Gemeinden ihre Rolle in der Kriminalitätsvorbeugung kaum finden, die Vorbeugung von Kriminalität beschränkt sich vor allem auf die Einschränkung der Möglichkeit von Straftaten.

Gemäß Standpunkt des Verfassers kommen die langfristigen Mittel der Kriminalitätsbekämpfung, wie die Verstärkung der gesellschaftlichen Kohäsion, der Kampf gegen Ausgrenzungen, die Konfliktlösung und die Einbeziehung von Institutionen in die Kriminalitätsvorbeugung, welche die Grundlagen des gesellschaftlichen Kapitals bedeuten, in den Ländern der osteuropäischen Region nur begrenzt zur Geltung. ■

NOTES

[1] Spencer, J.-Hebenton, B. (1999): Crime and insecurity in the new Europe: some observations from Poland. The British Criminology Conferences: Selected Proceedings. Volume 2. (ed.: Mike Brogden) Papers from the British Criminology Conference, Queens University, Belfast, 15-19 July 1997.

[2] The meaning of human security Economic Governance Program Bratislava RSC, January 2003

[3] CBOS - Public Opinion Research Centre: Economic Situation and Living Conditions in Central and Eastern Europe. Polish Public Opinion, March, 2002. http://www.cbos.pl

[4] Database Central Europe: Labour Costs in Central and Eastern Europe. Budapest, February 2003 http://www.databasece.com/PR-1.htm

[5] Database Central Europe: Labour Costs... http://www.databasece.com/PR-1.htm

[6] Dąbrowski, M. - Gortat, R. (2002): Political Determinants of Economic Reforms in Former Communist Countries. Studies & Analyses 242, Center for Social and Economic Research. Warsaw

[7] Kuhnert, I. (2004): An Overview of the Economies of the New Member States. Statistics in focus. EUROSTAT. European Communities Economy and Finance, Theme 2 - 17/2004. p.6.

[8] Kuhnert, I. (2004): An Overview... p.6.

[9] Promoting the policy debate on social exclusion from a comparative perspective. Trends in Social Cohesion No. 1. Council of Europe, December 2001. p.21.

[10] http://www.dzs.hr/defaulte.htm

[11] Promoting the policy debate on social exclusion from a comparative perspective. Trends in Social Cohesion. No.1. Council of Europe, December 2001. p.14.

[12] Aromaa, K. (2000): Trends in Criminality. In: Crime and Criminal Justice in Europe, Council of Europe Publishing

[13] Young, J. (1998): From inclusive to exclusive society. Nightmares in the European Dream. In: V.Ruggiero, N.South, I.Taylor (eds) The new European Criminology. Crime and Social Order in Europe. Routledge, London and New York, pp. 64 - 91.

[14] CEORG (2001 June): Lithuanian Public Opinion Trends. Vilmorus Market & Opinion Research

[15] In the former Soviet Union the number of crimes that became known rose from 1.798 million (1987) to 2.786 million (1990). In the former Czechoslovakia, crime rates swelled by 200 per cent after the Velvet Revolution, in 1989. As a member of the united Czechoslovakia, Slovakia had a crime rate of 41 thousand in 1989. The figure jumped to 99 thousand by 1992.

[16] Effective from 1 January 2002 the amendment to Act No. 265/2001 Coll. the Code of Criminal Procedure, a newly regulated calculation of the amount of damage for the purpose of criminal proceedings - amounts determining the limit of criminal liability for some crimes against property and classification of the circumstances of such crimes depending on the amount of the damage have been increased up to CZK 5,000 Kč (formerly CZK 2,000).

[17] Kertész, I. (2000): The Unfinishable War, Publisher of the Ministry of the Interior, Budapest, p. 311.

[18] Spencer, J. - Hebenton, B (1999): Crime and Insecurity in the New Europe: Some Observations from Poland. The British Criminology Conferences: Selected Proceedings. Vol. 2. Papers from the British Criminology Conference, Queens University, Belfast, 15-19 July 1997. (Editor: Mike Brogden)

[19] van Kesteren, J. - Mayhew, P. - Nieuwbeerta, P.: Criminal Victimisation in Seventeen Industrialised Countries. Key findings from the 2000 International Crime Victims Survey. Onderzoek en beleid, no. 187.

[20] EC Committee on the Environment and Agriculture (2001. July): Security and crime prevention in cities: setting up a European observatory. Report. Doc. 9173.

[21] Report on the Hungarian drug situation, 2002. Ministry for Youth and Sports, Budapest, 2002. p. 76.

[22] http://www.ogd.org/rapport/gb/RP05_2_UKRAINE.html

[23] See: Romani Human Rights in Europe. Hearing before the Commission on Security and Cooperation in Europe One Hundred Fifth Congress. First Session. Printed for the use of the Commission on Security and Cooperation in Europe JULY 21, 1998 [CSCE 105-1-X] p. 11-12.

[24] 'The Continuous Research of Victimisation and Citizens' Feelings of Being Safe 2000-2002'; '1999 Security Risks1'. The data was gathered in April 2003 by the method of standardised interviews - a sample of 1,500 respondents of over 15 years of age from the whole country. The sample was selected using so-called quota selection.

[25] Questionnaire on everyday violence (Slovenia). Council of Europe, Integrated Project 2. Responses to violence in everyday life in a democratic society. Questionnaire answered by Dr. Gorazd Meško.

[26] Meško, D.: draft version, 2003.

[27] CBOS - Public Opinion Research Centre: Fear of crime among the residents of Poland. Polish Public opinion, May 2002. http://www.cbos.pl

[28] CEORG (July 2002): Perceptions on Personal Safety, Quality of Police Protection and Attitude towards Death Penalty in Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Hungary, Lithuania, Poland and Russia. July, 2002. Central European Opinion Research Group. http://www.ceorg-europe.org

[29] CBOS - Public Opinion Research Centre: The Feeling of Safety among the Poles, Czechs, Hungarians, Lithuanians and Russians. Polish Public Opinion, July-August 2001. p.1. http://www.cbos.pl

[30] 'Victims and Opinions' Victim Survey ("Áldozatok és vélemények") National Institute of Criminology, Budapest, 2003. (Manuscript) The data was gathered in April-June 2003 by the method of standardised interviews - a sample of 10,020 respondents of over 18 years of age from the whole country. http://www.okri.hu

[31] Aebi, M.- Barclay, G. - Jehle, J-M. - Killias, M: European Sourcebook of Crime and Criminal Justice Statistics, 1999 (Council of Europe) Key findings

[32] http://www.just.ee/index.php3?cath=2232

[33] Krajewski, K: Transformation and Crime Control: Towards Exclusive Societies Central and Eastern European Style? Conference paper presented at 'New tendencies of delinquency, changes of criminal policy in Central and Eastern Europe' The 65th Regional Seminar of the Hungarian Society of Criminology and of the International Society of Criminology, 11-14 March 2003. Miskolc, Hungary

[34] Walmsley, R. (2003): Further developments in the prison systems of Central and Eastern Europe. HEUNI. Helsinki. p. x-XIV.

Lábjegyzetek:

[1] Department of Criminology, Telephon number: (36-1) 411-6521, e-mail: kerezsi@ajk.elte.hu