Doris Folasade Akinyooye[1]: Africa - EU Trade Relations - Legal Analysis of the Dispute Settlement Mechanisms under the West Africa - EU Economic Partnership Agreement (ELTE Law, 2020/1., 125-146. o.)

Introduction

The European Union (EU) - Southern African Development Community (SADC) Economic Partnership Agreement (EPA) is the first regional EPA in Africa to become fully operational. West Africa (WA) is the EU's largest trading partner in Sub-Saharan Africa. Yet, the WA - EU EPA has not been ratified. Although the recent entry into force of the African Continental Free Trade Agreement (AfCFTA)[1] signals progress in the regional integration of the fragmented African economies, the regional EPAs - considered as its building blocks - are slowly aligning. Inflexibility and insufficient financial guarantees from the EU to help the African States deal with the detrimental fiscal impacts of the EPAs are the key reasons for the reluctance to ratify. Nigeria, the largest economy on the continent has blocked the WA - EU EPA from coming into force. The WA - EU EPA deserves a focused legal analysis to establish its strengths and weaknesses. In the event of a dispute in trade relations under the EPA, is the current dispute settlement mechanism suitable and effective? The article analyses the text of the WA - EU EPA to determine the characteristics of the legal safeguard provisions and the dispute settlement procedures applicable. It also assesses the legal implications of these legal safeguards to illustrate why they act as disincentives to ratification. The article concludes that the current form of the dispute settlement mechanism is not sufficiently reassuring to the WA States especially in the context of a purportedly development-friendly trade agreement.

- 125/126 -

I. Dispute Settlement Mechanism in the WA - EU EPA

Prevailing factors in WA States such as a lack of diversification of economy and limited sources of fiscal revenue are common. These challenges provide fertile ground for trade barriers.

The European Commission considers dispute settlement as 'a precious tool to address trade barriers'.[2] The provisions embodied in the EPAs should give a legitimate expectation of legal certainty, predictability, and protection to both parties. The extent of their interpretation, application, and enforcement arguably relies on the effectiveness of the underlying dispute settlement mechanism. The EPAs are a partnership based on economic and development cooperation. Although, the EPAs makes many references to the WTO Agreements, the dispute resolution mechanism in the WA - EU EPA cannot be said to be modelled on the WTO Dispute Settlement System. The dispute settlement mechanism provided in the WA - EU EPA have presumably been legally scrubbed in the course of negotiations, however, there remain weaknesses.

Firstly, the lack of capacity, in terms of technical and financial capacity, of the WA States to initiate or participate in the dispute settlement mechanisms is not new, nor does it come as a surprise. This is explicitly acknowledged in the WA - EU EPA under the provision on Cooperation:[3]

The Parties agree to cooperate, including financially, in accordance with the provisions of Part Ill of this Agreement[4], with regard to legal aid and in particular with regard to building up capacities in order to make possible the use by the West Africa Party of the dispute settlement mechanism provided for in this Agreement.

The agreement to cooperate can be interpreted as meaning that the EU party would provide financial and technical support in the form of legal aid. on the other hand, the WA party would need to cooperate by respecting the terms and conditions of the aid. Although it can be argued that the (financial) legal aid is a precondition or a prerequisite before the WA party can be expected to 'make possible the use'[5] of the dispute settlement mechanism. The article is phrased to imply that the (financial) legal aid and capacity building is neither a unilateral obligation of the EU party, nor an absolute right of the WA party. Several EU Civil Society

- 126/127 -

Organisations (CSOs)[6] have remarked on the implied non-committal of the WA - EU EPA provisions on development cooperation in general.[7] They note that the EU resisted ACP requests for EPAs to contain development cooperation provisions from the start of the negotiations and since then the EU has only accepted non-committal language. It should be recalled that the development objective/dimension, that is, an intentional support by the EU party to the WA party in this regard, has always been espoused as the raison d'etre of past and pending ACP-EU trade agreements. The development finance cooperation commitment enshrined under Part 4 of the CA, which is the foundation of the WA - EU EPA states:

ARTICLE 55 Objectives

The objectives of development finance cooperation shall be, through the provision of adequate financial resources and appropriate technical assistance, to support and promote the efforts of ACP States to achieve the objectives set out in this Agreement on the basis of mutual interest and in a spirit of interdependence.

Without an unequivocal commitment to financial and technical aid, it is unsettling to consider that one party in a dispute has an outright comparative advantage over the other, as would be the case since the WA party would rely on the EU party, if it so wishes, to provide the technical and financial means for consultations, mediation, and arbitration. The fairness and equality (key principles of public international law) implications of this are not hard to imagine.

The Africa - EU regional EPAs are intended to be building blocks for the AfCFTA.[8] The general provisions of the AfCFTA are very similar to the EPAs. For example, Article 26 (e) of the AfCFTA covers the same matters (except data privacy and protection) to Article 87(c) of the WA - EU EPA. However, the AfCFTA is said to be 'still very weak and needs a lot of work which could take at least three more years' to finalise.[9] There are also the same outstanding regulatory issues as in the EPA such as investment, intellectual property, competition, rules of origin, and e-commerce.[10] Notably, Benin, Eritrea, and Nigeria have not signed the AfCFTA. Nigeria's main objection is that, just as with the EPA, the protection of domestic industry is not guaranteed. To add to the complexity of the lacking harmonisation between the WA - EU EPA and the AfCFTA, some authors argue that the iEPAs disrupt regional

- 127/128 -

integration because borders will need to be established in those countries, which have not signed iEPAs in order to prevent EU imported goods into the iEPA States from coming into their territories.[11] There is potential for dispute. In this regard, although another key tenet of the WA - EU EPA is the promotion of regional integration, it is difficult to see how the WA - EU EPA could co-exist compatibly with the continent-wide trade agreement: the African Continental Free Trade Agreement (AfCFTA). Furthermore, like the WTO system, the AfCFTA makes provision for a Dispute Settlement Body to be established, which can form a dispute settlement panel and appellate body to assist the DSB in making recommendations or rulings on a dispute. It also allows the State Parties to request/undertake the process of good offices, conciliation, and mediation.[12] This option is not given in the WA - EU EPA. There is also the risk of procedural and jurisdictional confusions that can affect legal certainty due to the fact that the issues of dumping and subsidies fall under a distinct dispute resolution mechanism in the EPA [Article 20(6)]. This special legal review procedure is to be applied where the dispute concerns anti-dumping duties, countervailing measures, and multilateral safeguards. Although Article 20(1) WA - EU EPA allows for both parties to individually or collectively take anti-dumping or countervailing measures under the relevant WTO Agreements (including the Agreement on Subsidies and Countervailing Measures (SCM)), on the other hand, Article 20 (8) WA - EU EPA curtails the dispute settlement procedure to be applied. It states: 'The provisions of this Article shall not be subject to the dispute settlement provisions of this Agreement'. This implies that these measures can neither be subjected to arbitration, nor to the extensive special or additional dispute settlement rules and procedures under the SCM Agreement, nor to the invocation of the WTO dispute settlement mechanism. The following flow chart illustrates the special procedure [Article 20(6)] proposed in the WA - EU EPA:

- 128/129 -

Figure 1.

Source: (D. F. Akinyooye) Author's illustration

- 129/130 -

II. Stepping Stone Agreements under the WA - EU EPA

As an illustration of the nature of Stepping Stone Agreements, the Ghanaian case is briefly examined. The Stepping Stone Agreement (iEPA) with Ghana was signed on 28 July 2016, and ratified by the Ghanaian Parliament on 3 August 2016. A recent headline points to alleged dissatisfaction with the EPA by the local private sector.[13] The Chief Executive Officer of the Private Enterprises Federation (PEF) criticised the EPA stating 'they can ban our products anytime they want without arbitration; without recourse to us. To judge this statement, the relevant provisions of the EPA are assessed. Firstly, under Article 24(2), the EU cannot impose multilateral safeguards on imports from Ghana within five years of the coming into force of the iEPA. At the end of that period, the EPA Committee will need to review the development situation of Ghana to determine if this exception should be extended.[14] If it is not, and the EU enforces multilateral safeguards, such as those having the effect of a 'ban, the matter can only be addressed using the WTO Dispute Settlement mechanism, and not that of the EPA.[15]

Concerning bilateral safeguards only between the EU and Ghana, the EPA lays down prerequisite scenarios (either of them would suffice, they need not be accumulated) that would warrant the imposition of a safeguard measure by the EU on Ghana, and vice versa:

(a) serious injury to the domestic industry producing like or directly competitive products in the territory of the importing Party, or

(b) disturbances in a sector of the economy, particularly where these disturbances produce major social problems, or difficulties which could bring about serious deterioration in the economic situation of the importing Party; or

(c) disturbances in the markets of like or directly competitive agricultural products or mechanisms regulating those markets.[16]

However, only one or more of any of the following safeguard measures (including surveillance measures are also permitted[17]) can be imposed to remedy any of the above situations:

(a) suspension of the further reduction of the rate of import duty for the product concerned, as provided for under this Agreement;

(b) increase in the customs duty on the product concerned up to a level which does not exceed the customs duty applied to other WTO Members; and

(c) introduction of tariff quotas on the product concerned

Presumably, these measures would fall under the general dispute settlement mechanism (including arbitration) provided for in the EPA, but this is not explicitly mentioned under the

- 130/131 -

article. Instead, there is a repeated emphasis on notification to, and periodic consultations within, the EPA Committee.[18] It follows that PEF's interpretation holds true in the case of bilateral safeguards too. This illustrates that the concerns of the private sector have not been allayed, even in an EPA that has been heralded as a showcase of the WA - EU trade relations.[19] The main issues are similar to those put forward by Nigeria, that is, the lack of local capacity to develop indigenous industries and to implement the EPA without adequate support for the local transformation process and reforms.[20]

III. Dispute Avoidance in the WA - EU EPA

Some legal reports opine that the dispute settlement mechanism in the EPA will not be used in practice since state-to-state disputes are rather addressed through alternative, less adversarial means.[21] The first joint meeting of the SADC - EU EPA Implementation Committee already gives an indication of this preference.[22] As the excerpt below shows, the parties agreed to disagree on the legality of the investigation into the South African safeguard duty on EU poultry;[23] the EU party disputed the findings and recommendations of the South African International Trade Administration Commission (ITAC)[24]:

1. SAFEGUARD INVESTIGATION ON POULTRY

• A discussion took place on the safeguard measure. The EU reiterated its disagreement on using Article 34 EPA as a basis for the continuation of the investigation. The parties noted their disagreement on this issue.

• SACU stressed that the ITAC investigation is closed and that any measure needs to be based on facts and on the applicable legal provisions.

• EU to provide a comprehensive written submission on the ITAC recommendation within 14 days.

• Parties agreed to hold a technical discussion on that basis in the week of 21 November 2017 with a view to finding a solution acceptable to the parties concerned.

- 131/132 -

Since then, the safeguard duty has been maintained and extended resulting in lost competitiveness for the EU.[25] The case is significant because it illustrates the two separate adjudicatory paths available for a State party (the South African Minister of Trade and Industry) and for a private entity (the South African Association of Meat Importers and Exporters and the South African Poultry Association) on the valid interpretation and application of the EPA.[26] SADC brought the dispute before the Trade and Development Committee for consultations and periodic reviews in line with Article 34 (7) (e).

The measure is prohibited under Article 34 (10) from being dealt with using the WTO Dispute Settlement mechanism. The private entity can only bring a case before the domestic courts for a judgment on the validity of a State entity's actions in accordance with national legislation. Such a judgment could impact the State's application of the EPA. As some legal academics have rightly opined:

A claim by a private party that executive action is invalid because transitional arrangements in successive trade agreements have been wrongly interpreted, takes arguments about rationality and respect for the rules on the intra vires exercise of powers, into new territory.[27]

The information exchanged and positions adopted by both parties during consultations and mediation remain confidential.[28]

IV. Arbitration under the WA - EU EPA

The WA - EU EPA can be deemed a contract between the EU and WA. The Rome Treaty,[29] and subsequently the Maastricht, Amsterdam, and Lisbon Treaties,[30] provide that the Court of Justice of the EU shall have jurisdiction to give judgement pursuant to any arbitration clause contained in a contract concluded by or on behalf of the Community, whether that contract be governed by public or private law. Furthermore, the legal basis for jurisdiction of the General Court in the WA - EU EPA context is also supported by case law.[31] During the first

- 132/133 -

ten years of implementation of the WA - EU EPA, the SDT applied with respect to dispute settlement is to abstain from arbitration. It is not clear though whether this obligation is to be observed by the WA States too.

ARTICLE 82 Transitional provision

To take account of the special situation of West Africa, the Parties agree that, for a transitional period of ten (10) years following the entry into force of this Agreement, the European Union Party shall give full preference to consultation and mediation as ways of settling disputes and shall display moderation in its demands.

In the WA - EU EPA, arbitration is the last resort. There is no appeal procedure. The nature of arbitration deserves some analysis. It is said that the substance of arbitration is procedure as has been famously quoted 'arbitration as a subject is procedure'[32] In international commercial arbitration, the duty of the arbitration panel is to give full satisfaction to party autonomy while simultaneously maintaining fairness and efficiency between the parties.[33] This is especially important for the parties with different legal traditions and norms. Expediency and flexibility are key expectations by the parties in a dispute. Arbitration is also invariably expensive, not least because of the fees charged by highly experienced private lawyers, and rental costs of arbitration forums. It can be inferred that the absence of an appeal level in the EPA is deliberate in the interest of saving cost and time. But where time is paramount, quality and accuracy might be subverted. Given that the arbitration panel rulings may or may not be publicised,[34] it will be difficult to determine how decisions were reached.

Under the CA, if a party requests for arbitration, within thirty days from the request, both parties are to appoint one arbitrator each. The two arbitrators appoint a third arbitrator. In the event of failure to do so, either Party may ask the Secretary General of the Permanent Court of Arbitration to appoint an arbitrator.[35]

Interestingly, the CA does not provide for mediation as a dispute avoidance / resolution mechanism. It only encompasses consultations in general terms[36] and arbitration as the specific dispute settlement mechanism.[37]

The rules of interpretation applicable to the CA, (as for the regional WA - EU EPA), are the customary rules of interpretation of public international law, including those set out in the Vienna Convention of 1969 on the Law of Treaties.[38]

- 133/134 -

Under the WA - EU EPA, the same measure cannot simultaneously be initiated before the WTO Dispute Settlement Body and the EPA Arbitration Panel.[39] The initiated proceeding must first be concluded. A party can suspend observance of its obligations under the EPA if the WTO DSB authorises it to do so. Conversely, if a party is authorised under the EPA to suspend benefits, the WTO Agreement cannot prevent it.[40] Arbitration under the EPA cannot rule on any WTO-related rights and obligations of each Party.[41] The Table 1 below outlines the three main dispute settlement options under the WA - EU EPA.

Table 1. Comparison of the dispute settlement options in the WA - EU EPA

| WA - EU EPA | Consultation Art. 65 | Mediation Art. 66 | Arbitration Art. 67 |

| Means of notification | Written request | Written request | Written request |

| Party to inform | - The other party - The JIC | - The other party - The JIC | - The other party - The JIC |

| Aim of request | Formal initiation of consultations | Agree to mediation | Request for arbitration panel establishment |

| Characteristics of the adjudicator | The JIC presides | 1 mediator - Parties to select within 10 days, or - JIC to select w/in 20 days | 3 arbitrators selected from the List (21 general list + 15 sectoral list) |

| Action | Consultation | Convene mediation | Establish panel |

| Time limits modifiable? | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Time limit for general cases | 60 days | 30 days from date of agreement | Within 10 days from the request, each party appoints an arbitrator. If not, request JIC to appoint within 5 days. |

| Undertake within | 40 days | Within 45 days of appointment, give non- binding Opinion | Within 120 days of establishment, the panel presents an interim report. The parties have 15 days to send written comments. |

| Conclude within | 60 days | Within 15 days from date of meeting collect parties' submissions. | Within 150 days of establishment, the panel ruling. Time extension until 180 days from the date of establishment. |

| In urgent cases | 15 days until 30 days | Within 75 days of establishment until 90 days Within 10 days of establishment, the panel can give a preliminary ruling on urgency of the case |

- 134/135 -

| WA - EU EPA | Consultation Art. 65 | Mediation Art. 66 | Arbitration Art. 67 |

| Outcome option | Mutually agreed solution | Non-binding opinion (may include recommendation) | A binding arbitral ruling that sets out the findings of fact, the applicability of the relevant provisions of the EPA and the reasoning for the |

| No consultation held | Arbitral ruling within 150 days from the date of establishment of the panel, or 180 days, at the latest, after notifying the Parties and the Joint Implemen-tation Committee (JIC) in writing. | ||

| Within 90 days from establishment, arbitral ruling is to be given in urgent cases. | |||

| Next step available | By mutual agreement, seek a mediator | Request arbitration | Actions formulated to achieve compliance with ruling. |

| Request arbitration | Agreement on reasonable time to comply with ruling. | ||

| Within 30 days from ruling, the Defendant party informs the Complainant and the JIC of the time it will take to comply. | |||

| If there is disagreement, the Complainant must send a written request within 30 days from receipt of Defendant's estimated time, to the panel to rule on reasonable time. | |||

| The reasonable period of time can be extended by mutual agreement of the parties. | |||

| Status of information | Confidential | Confidential | Arbitral ruling can be publicised or kept confidential if the JIC so decides. |

| Before end of reasonable compliance time, the Defendant notifies the Complainant and the JIC of the measure taken to comply. | |||

| Complainant can send a reasoned written request for a ruling on the compatibility of the measure to the Panel. | |||

| Within 90 days from date of request, Panel gives its ruling on compliance. Within 45 days, for urgent cases. Within 105 days from request, if original Panel cannot reconvene. |

- 135/136 -

| WA - EU EPA | Consultation Art. 65 | Mediation Art. 66 | Arbitration Art. 67 |

| If Defendant fails to notify before end of reasonable time, or if ruling determines non-compliance, Complainant can ask for compensation (incl. financial). | |||

| If no mutual agreement on compensation is reached within 30 days from end of reasonable time or from delivery of ruling, Complainant can adopt appropriate measures after notifying Defendant. The measure(s) must be those which least affect the attainment of the objectives of the EPA. | |||

| Where the Defendant is the EU, and the complaining Party is entitled to adopt appropriate measures, but asserts that the adoption of such measures would result in significant damage to its economy, the EU shall consider providing financial compensation. The EU shall exercise due restraint in asking for compensation or adopting appropriate measures. These must be temporary until the dispute is settled or the violation is rectified. | |||

| The Defendant shall notify the Complainant and the JIC of the measures taken to comply with the EPA and request that the appropriate measures be ended. | |||

| If the Complainant does not agree that the measure is compliant, it can request within 30 days from notification, the original Panel to rule on the compliance. It must also inform the Defendant and the JIC of this request. | |||

| Within 45 days, the Panel gives a ruling on compliance notifying the parties and the JIC. If incompatible, the Panel determines whether the Complainant may continue to apply appropriate measures. If compliant, the measures must be terminated. If original Panel unable to reconvene, the ruling can be given within 60 days from receipt of request. |

- 136/137 -

| WA - EU EPA | Consultation Art. 65 | Mediation Art. 66 | Arbitration Art. 67 |

| Panel sessions may be open to the public unless requested otherwise by the parties or the Panel. | |||

| Interested entities are authorised to submit amicus curiae briefs to the arbitration panel. The Panel must notify the Parties of these submissions and allow them to comment. | |||

| Panel rulings are taken by consensus or, if not possible, then by majority vote. | |||

| Mutually agreed solution can be reached at any time. It should be notified to the JIC (and the Panel, if any) and adopted. | |||

Source: Author's compilation

V. Legal Certainty under the WA - EU EPA

A dispute settlement mechanism should be comprehensive and reassuring to Parties that it provides legal certainty, clarity through interpretation of provisions, and security in protecting rights and enforcing obligations. It is interesting to note that the term 'arbitral award' is not used at all. There is no indication of how to overcome potential or actual deadlock. This raises questions to be further analysed. What appeal options are available beyond the arbitral ruling? What is the status of Panel recommendations (as opposed to ruling)?

A few criticisms can be drawn from these options, especially on arbitration. The set number of arbitrators on a panel is questionable. Why is it fixed to only three arbitrators? The most common composition of the arbitration panel is three as many literatures[42] highlight the speed, cost effectiveness, and efficiency of a three-person panel compared to a higher or lower number. Similarly, international arbitration courts[43] have set the number three as default, but do allow the parties to decide on the number of their choice.[44] Yet in a multiparty case such as would be the case under WA - EU EPA, the issue of party equality and influence over the nomination of arbitrators is an issue. It is probable that the parties on each side would not agree on the designations because of their differing interests. As the watershed Dutco case[45]

- 137/138 -

outlined, the issue of party autonomy and discretion in appointing their choice of arbitrator is a matter of public policy.[46] It is crucial that the parties to a dispute be treated fairly and equally and reach a mutual agreement on the constitution of the arbitration panel, otherwise the arbitral award risks being unenforceable and annulled. Under the Yaoundé Conventions, disputes were first addressed by the Association Council to reach an amicable settlement. Failing this, the dispute was brought before the arbitration court consisting of five arbitrators ruling by a majority vote: a president appointed by the Association Council and four judges (two appointed by the Council of the EEC, and two by the Associated States).[47] It should be noted that the arbitration court under Yaoundé (and Lomé) was a fixed institution, and it was later defunct. The current method relies on the appointment of an ad hoc arbitration panel by the parties.[48]

According to Article 68 WA - EU EPA, the applicant and the respondent are to propose one each, and agree on the chair. They are to consult one another to agree on the selection. However, what about when there are many parties on both sides of a dispute? It is not farfetched to imagine the additional delay and difficulty of several parties agreeing on just one arbitrator in whom they could unequivocally bestow their confidence. According to general principles of international law, the dispute resolution mechanism between contracting parties should provide for a neutral forum that can guarantee the observance of impartiality and fairness. To ensure neutrality, there must be a depoliticization of the dispute resolution mechanisms. However, the Joint Implementation Committee, the executive decision-maker, or at the least, the watchdog on the interpretation and application of the EPA, is to be comprised of senior officials appointed by the Parties. These officials are representatives of the parties' governments and thus inevitably bound by political affiliations and allegiances.

Among the 79 ACP countries,[49] 28 are major common law countries (a distinct feature of their Commonwealth history): Botswana, Cameroon, Gambia, Ghana, Kenya, Kiribati, Lesotho, Malawi, Mozambique, Namibia, Nauru, Nigeria, Papua New Guinea, Rwanda, Samoa, Seychelles, Sierra Leone, Solomon Islands, South Africa, Swaziland, Tanzania, Tonga, Trinidad and Tobago, Tuvalu, Uganda, Vanuatu, Zambia, Jamaica.

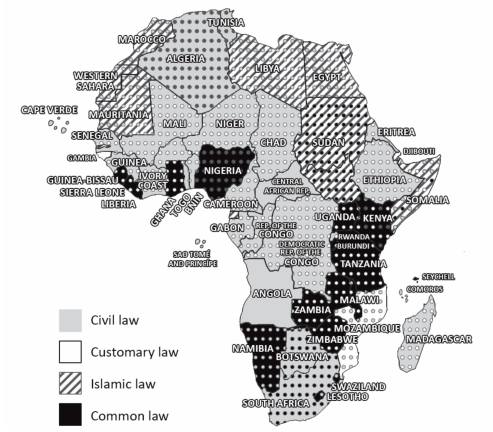

To achieve a level of harmonization that makes the EPA provisions workable, ACP domestic laws and legal systems are undergoing reform. This can be seen as a migration of EU law. The map below illustrates the myriad of mixed legal systems across African States. such a context adds a layer of complexity to achieving regulatory harmonisation and legal reform.

- 138/139 -

Figure 2. Geographical mapping of legal systems in Africa

Source: Opiniojuris.org

The EPA is framed as a stand-alone, self-contained agreement that is neither above nor below in the order of precedence among international economic and development cooperation laws or regulations. This is seen in provisions such as Article 87(c):

Nothing in this Agreement shall be construed to prevent the adoption or application by either Party of measures: (c) necessary to secure compliance with laws or regulations that are not inconsistent with the provisions of this Agreement...

And Article 105(1):

1. Nothing in this Agreement may be interpreted as preventing the taking by the European Union Party or any of the West African States of any measure deemed appropriate concerning this Agreement in accordance with the relevant provisions of the Cotonou Agreement.

- 139/140 -

This provision implies that the EPA is subordinate to the CA because measures not sanctioned or contained in the EPA, and measures that can affect the EPA, can nevertheless be taken by the parties if they are based on the CA. However, in view of the expiration of the CA in February 2020, this provision would become obsolete, thereby rendering the any contemplated measures subject to the EPA itself.

Article 105 (2) provides that: '(2) The Parties agree that nothing in this Agreement requires them to act in a manner inconsistent with their obligations in connection with the WTO.'

Article 84 (3) raises the legal status of the EPA to the same level as the WTO. Since the EPA(s) was (were) established to rectify and regulate Africa - EU trade regimes on the principle of conformity with the WTO, it follows that the EPAs fall under the umbrella of the WTO Agreement. However, attention should be paid to Article 84 (3) which is ambiguous, and therefore can be misleading, in understanding the order of precedence of both agreements: 'The WTO Agreement cannot prevent the Parties from suspending the benefits granted under this Agreement.'

The few exceptions where parties' actions are permitted to 'subordinate' the EPA are those that concern security purposes,[50] balance of payments difficulties,[51] taxation[52]. Having said this, the EPA accumulates the existing rights and obligations under the various WTO Agreements as it makes reaffirmations of these across a significant number of provisions. Notably, mutual obligations pertaining to SPS and TBT standards.[53]

VI. EU Case Law and Potential Impact on the WA - EU EPA

There are notable legal safeguards in place within EU primary law and secondary law.

The ECJ has the competence to give a preliminary ruling on the provisions of the Cotonou Agreement. In Afasia Knits Deutschland,[54] the Court ruled that all contracting states of the CA, as well as the European Commission, have the right, even when a matter does not directly concern their national authorities, to initiate an investigation into a suspected infringement of the CA provisions. The main proceedings of this particular case involved the post-clearance recovery of import duties by the German customs based on the wrongful issuing of (EUR.1) certificates of origin by the Jamaican (ACP States) authorities entitling the exported textiles to preferential treatment. The Court further held that the findings of such a verification investigation are binding on the national authorities of the importing State concerned:

- 140/141 -

32. It follows that, as pointed out in the written observations of the Czech and Italian Governments and of the Commission, and as observed by the Advocate General at point 23 of his Opinion, subsequent verification must be carried out not only when the importing Member State so requests, but also, in general, when, according to one of the States party to the Agreement or according to the Commission, which, in accordance with Article 211 EC, is charged with ensuring the correct implementation of the Agreement, there are indications which point to an irregularity in regard to the origin of the imported goods.

This judgment highlights the importance of mutual trust and administrative cooperation provisions in the CA, and consequently, in the EPA. There is, as yet, no EU case law that refers to the EPA. Given the fierce economic diplomacy and internationalisation of EU trade values, it is not farfetched to posit that the long arm of the ECJ's jurisdiction will increasingly adjudicate on EPA provisions. It is only a matter of time, however, before main proceedings in an EU Member State(s), are referred by a national court to the ECJ to interpret the proper meaning of the EPA. Through Articles 56 (2) (d) and (e), and Articles 64 (2)-(5) of the Modernised Customs Code,[55] the EPA-based EU commitment to duty-free, quota-free (DFQF) ACP imports are enshrined in EU law.

It has become settled EU case law that a 'special situation'[56] such as 'ambiguous and inconsistent determinations' by an exporting State customs authority resulting in unreliability justifies an overruling of the mutual trust principle and places the onus on the Commission to take over the investigation.[57] The Court has also emphasised the key role which the exporting State has to play in order to derive the benefits of the preferential treatment:

50. ...it is only after the authorities of the State of export have been involved that the products originating from the ACP State in question will be permitted to benefit from the arrangement introduced by Annex V to the Cotonou Agreement.[58]

- 141/142 -

VII. WTO Case Law and Potential Impact on the WA - EU EPA

Free trade can be brutal. The 'Banana wars' that lasted from 1993 to 2012 between the US and the EU illustrates this. The WTO ruled in favour of the US and demanded the EU to revoke its preferential arrangement with the Caribbean on its banana exports. It held that the special arrangement was discriminatory towards Latin American suppliers and therefore a violation of WTO rules. As at November 2018, there have been no cases brought by or against any ACP State in WTO DSU. In contrast, the EU has been a party to cases brought to the WTO DSU, with the main opponents being the US, Canada, India, China, and Argentina.[59]

There are multiple anti-dumping disputes brought against the EU by WTO Members before the WTO DSB. One such case was between China and the EU concerning anti-dumping duties on High-Performance Stainless Steel Seamless Tubes (HP-SSST) from the EU.[60] The EU argued that China had contravened Article 6.9 of the WTO Anti-Dumping Agreement because it did not disclose the facts underlying its dumping determinations with respect to specific cost and sales data determining the margin of dumping, which therefore prevented the affected parties from properly defending their interests. The Panel rejected the EU's claim and instead ruled that a narrative description was sufficient to satisfy the requirement for essential facts under Article 6.9, so long as the technical details were in the possession of the investigating authority.[61]

The Panel itself referred to past WTO rulings to support its understanding of the article:

Previous WTO dispute settlement panels have established that the basic data underlying an investigating authority dumping determination constitute "essential facts" within the meaning of Article 6.9. We agree. In addition, the panel in China - Broiler Products[62] found that a narrative description of the data used cannot ipso facto be considered insufficient disclosure, provided the essential facts the authority is referring to are in the possession of the respondent... We agree.

The EU appealed the Panel's ruling as erring in the interpretation and application of the said article, whereas China argued that the article can be interpreted in different ways that equally satisfy the obligation.[63] The Appellate Body considered this issue to be a point of law concerning a legal standard[64] and therefore allowed the appeal. The Appellate Body applied a logical

- 142/143 -

approach to construe the meaning of the Article. It referred to previous WTO rulings on, and further analysed, the word 'essential':

Whether a particular fact is essential or "significant in the process of reaching a decision"[65] depends on the nature and scope of the particular substantive obligations, the content of the particular findings needed to satisfy the substantive obligations at issue, and the factual circumstances of each case, including the arguments and evidence submitted by the interested parties... Thus, while Article 6.9 does not prescribe a particular form for the disclosure of the essential facts, it does require in all cases that the investigating authority disclose those facts in such a manner that an interested party can understand clearly what data the investigating authority has used, and how those data were used to determine the margin of dumping.[66]

By applying both inductive and deductive interpretation methods,[67] the Appellate Body laid down the parameters of the obligation, and found that the scope of the legal standard is to be determined by having regard to the object and purpose of the obligation. This is consistent with the customary rules of interpretation, particularly Article 31 of the Vienna Convention.

It held that:

While the Panel's reading of the scope and meaning of Article 6.9 is not entirely clear, it appears to us that...contrary to what the Panel stated, it does not suffice for an investigating authority to disclose "the essential facts under consideration" but, rather, it must disclose the essential facts under consideration that "form the basis for the decision whether to apply definitive measures".[68]

Following on from its interpretation, the Appellate Body proceeded to complete the legal analysis of the merits of the case finding in favour of the EU.

This case is illustrative of the significance of interpretation of the legal standard applicable to investigating authorities' obligations in anti-dumping measures determination. The Appellate Body's reversal of the Panel's interpretation marked the turning point in favour of the EU's appeal.[69] China lost the case as it was requested to bring its measures into conformity with the Anti-Dumping Agreement and GATT 1994.[70]

- 143/144 -

VIII. Development Cooperation

The EPA is not just an FTA. It is intended to be a development instrument. The rationale for the waiver is predicated on the special situation of the developing countries. The key principles of development effectiveness defined in the Busan High Level Forum on Aid Effectiveness in 2011 and renewed at the last High-Level Meeting in Nairobi (2016) are: Country ownership; Transparency and accountability; Focus on results; and Inclusive development partnerships. The EU itself regularly monitors its performance in implementing the effectiveness principles through, for example, consultancies on partner country analysis, consultations with the EU Delegations on ground, and evaluation of the progress against the development effectiveness indicators. Such continuous monitoring and reporting is a standard development management system of major donors like the EU, World Bank, USAID, ADB, and AfDB. The findings are used by the senior officials in high-level committees. This system is their means of promoting accountability among their members, in their region, and on the global stage.

One credible solution would be to define development targets and indicators to be linked to the EPA implementation and review process.[71] By setting a benchmark for the EPA, the success or failure towards its objectives can be objectively measured. In sum, as succinctly put by some authors: 'reciprocity should be based on the attainment of objective socioeconomic indicators rather than on arbitrary timeframes and percentage of traded goods.[72]

At the expiry of the tariff-dismantling period, the trade-related part of the EPA would have served its purpose. It would essentially become obsolete and the WTO Agreement provisions would govern the trade and economic relations. What would be left of the EPA is its development cooperation dimension?

Conclusions and Recommendations

In the process of writing this article, there are a few significant events that have occurred and are worth mentioning. The French 'Yellow Vest' protest against high tax rates imposed by the Macron government. The Nigerian incumbent president was voted in again for a second four-year term. The US banned Huawei's access to US mobile networks and software updates, sparking a trade sanctions retaliation by China in ceasing its rare earth mineral supplies to the US. British Prime Minister Theresa May resigned after several failed attempts to secure a good deal to finalise Brexit. The European Parliament elections resulted in more seats for the Greens and Liberals, as well as for the far-right Eurosceptic parties. After ratification by the 24 [th] State, the African Continental Free Trade Agreement (AfCFTA) came into force on 30 May 2019, marking a historic milestone globally. This is a short, and perhaps bewildering, list, but its purpose is to illustrate the current state of affairs across continents in this globalized world.

- 144/145 -

Though direct and indirect impacts of all of these events on the state of the Africa - EU relations can be drawn, perhaps the most poignant for this article is the AfCFTA. When the continent-wide market of 1.2 billion people launches on 7 July 2019, the world's largest free trade area will be formed since the establishment of the WTO.

The negative consequences of market liberalization most often feared by parties of a preferential trade agreement such as the EPAs are dumping and subsidies. The EPAs explicitly provide that anti-dumping and countervailing measures shall be governed by the WTO Agreements. Disputes related to these are to be dealt with in the WTO Dispute Settlement mechanism (in the SADC - EU EPA) or by a special legal review mechanism (in the WA - EU EPA). This single legal review mechanism is not sufficiently detailed to inspire confidence about its workability. The WA States do not have the requisite level of experience, expertise, or capacity to initiate a WTO Dispute Settlement procedure, and therefore have little chance of successful claims. Reviewing the records of WTO disputes, the more active developing countries have been from Latin America and Asia. There are practically no WTO cases brought by or against African States (except South Africa). The closest experience Nigeria has had with WTO dispute settlement proceedings is as a third party.

In view of the findings of this article, there are several recommendations to be made. Firstly, the WA - EU EPA should incorporate development indicators to measure its progress at achieving its development objective. This would ensure that the original aim of the CA, to promote the growth and sustainable development of the ACP States, is respected. Secondly, the general principles of international law, particularly the need for independent and neutral dispute settlement mechanisms, can be better observed if the implementation committees of the EPAs are not politically affiliated officials of the contracting States. Instead, the role of the committee could be undertaken by dedicated officers in a neutral international institution such as the WTO, World Customs Organization (WCO), UNCTAD or OECD.

The arbitration mechanism under the EPA could be designed to better incorporate the privileges provided to developing countries under the WTO.[73] The EPA could provide for detailed rules on the possibilities for deadline extensions and accelerated procedures for the WA party. Fifthly, recalling Article 82 under which consultation and mediation are to be the only dispute settlement methods for the first ten years of EPA operation, it would be pragmatic to also include the method of good offices. Incorporating this diplomatic method into the overall dispute settlement mechanism of the EPA is logical since it is compatible with the other options of consultation and mediation. The positive impact of good offices should not be underestimated especially in the context of international trade and development relations between unequal partners as the WA, the ACP, and the EU.

The emerging political context in the EU should not be ignored either. The growing clout of the Green party in the European Parliament reflects the steady prioritization of environmental issues, which is likely to change the substance of the EPAs in the near future given the interdependence between commerce and environmental resources. Aspects like rules of

- 145/146 -

origin and SPS would need to be progressively revised. In view of this, the author also proffers a sixth recommendation that focuses on the influence of public policy on the reasoning of adjudicators. Dedicated trainings for the Joint Implementation Committee and the pool of arbitrators of the WA - EU EPA (but also for the other ACP-EU EPAs) on impact and causal analyses could sharpen their understanding of the relationships between market situations and factors of production. Keeping up-to-date in this regard would give them greater confidence in correctly interpreting and applying the provisions of the EPA.

The author acknowledges that there are several ways in which this topic can be further enhanced possibly within a doctoral program. For example, to attain a comprehensive picture of the strengths and weaknesses of the EPAs, a comparative legal analysis of the EU's trade agreements with the US, China, and Japan could be made. The methodology could be supplemented by quantitative analysis and an impact assessment. The findings would rank the quality of the Africa - EU EPAs within a broader global context. Another way would be to further elaborate on the regional integration dimension of the EPA. The research could hone in on the evolving process of the AfCFTA juxtaposed against the continuing negotiations of the EPAs towards becoming full and comprehensive regimes covering Services, Competition, and Investment. The findings would shed a new light on the nature of the Africa - EU EPA on how they can harmonise inter-, and intra-regional objectives. ■

NOTES

[1] Agreement establishing the African Continental Free Trade Area between the Member States of the African Union. Signed in Kigali on 21 March 2018 (Entry into force 30 May 2019) (hereafter AfCFTA).

[2] Report from the Commission to the Parliament and the Council on Trade and Investment Barriers, January-December 2017, 24. <http://trade.ec.europa.eu/doclib/docs/2018/june/tradoc_156978.pdf> <<http://trade.ec.europa.eu/doclib/docs/2018/june/tradoc_156978.pdf>> accessed 01 June 2019.

[3] Economic partnership agreement between the West African States, the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) and the West African Economic and Monetary Union (UEMOA), of the one part, and the European Union and its Member States, of the other part (hereafter WA - EU EPA), art 86.

[4] PART III: Cooperation for Implementation of Development and Achievement of the Objectives of the Agreement, WA - EU EPA.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Afrikagrupperna/Africa groups of Sweden; AITEC, France; ATTAC France; 11.11.11, Belgium; Both Ends, Netherland; Coordinadora de ONGD de Euskadi, Spain; CNCD 11.11.11, Belgium; Comhlamh, Ireland; Fair, Italy; Forum Syd, Sweden; German Stop EPA Coalition www.stopepa.de; Germany; IBIS, Denmark; Micah Challenge, Portugal; MS ActionAid, Denmark; Oxfam International; Setem-Catalunya, Spain; Traidcraft, UK; Trocaire, Ireland; World Development Movement, UK; World Rural Forum, Spain.

[7] Critical issues in the EPA negotiations, An EU CSO discussion paper, August 2009, <https://www.ft.dk/samling/20081/almdel/euu/bilag/555/718662.pdf> accessed 10 March 2020.

[8] 'Strengthening the EU's partnership with Africa Africa-Europe Alliance for Sustainable Investment and Jobs' <https://ec.europa.eu/commission/sites/beta-political/files/factsheet-africaeuropeallianceprogress-18122018_en.pdf> accessed 04 May 2019.

[9] Landry Signé and Colette van der Ven, 'Keys to success for the AfCFTA negotiations' May 30, 2019 <https://www.brookings.edu/research/keys-to-success-for-the-afcfta-negotiations> accessed 03 June 2019.

[10] Ibid.

[11] K. Nnamdi and K. Iheakaram, 'Impact of Economic Partnership Agreements (EPA) on African Economy: A legal perspective' <http://cega.berkeley.edu/assets/miscellaneous_files/6-ABCA-Nnamdi-Impact_of_EPA_on_AFR_economy.pdf> accessed 17 May 2019, 12.

[12] AfCFTA, Protocol on Rules and Procedures on the Settlement of Disputes, art 8.

[13] 'Ghana's private sector will block implementation of EPAs in its current form, New Ghana, 01 June 2019: <https://www.newsghana.com.gh/ghanas-private-sector-will-block-implementation-of-epas-in-its-current-form> accessed 02 June 2019.

[14] Stepping stone Economic Partnership Agreement between Ghana, of the one part, and the European Community and its Member States, of the other part. Signed in December 2014. (Entry into force December 2016) (Hereafter Ghana - EU Stepping Stone Agreement), art 24(3).

[15] Ghana - EU Stepping Stone EPA, art 24(4).

[16] Ghana - EU Stepping Stone EPA, art 25(2).

[17] Ghana - EU Stepping Stone EPA, art. 25(4)-(5).

[18] Ghana - EU Stepping Stone EPA, art 25(7) (a-e).

[19] See <https://eeas.europa.eu/delegations/ghana/7766/eu-welcomes-ghanas-signing-and-ratification-of-the-epa_en> accessed 02 June 2019.

[20] See <https://www.newsghana.com.gh/ghanas-private-sector-will-block-implementation-of-epas-in-its-current-form/> accessed 02 June 2019.

[21] Andrew Mizner, 'EU - Africa deal comes into effect' (November 2016) African Law and Business <https://www.africanlawbusiness.com/news/6863-eu-africa-deal-comes-into-effect> accessed 02 June 2019.

[22] ECONOMIC PARTNERSHIP AGREEMENT between the European Union and its Member States, of the one part, and the SADC EPA States, of the other part, signed on 10 June 2016 (Entry into force February 2018) (hereafter SADC - EU EPA). The SADC - EU EPA is used as an example here because there are no publicly accessible records on such issues with the WA - EU EPA or the Ghana / Ivory Coast iEPAs.

[23] It concerned a 13.9% provisional safeguard duty in 2016, expired in 2017, then renewed in 2018 to 35.3% imposed by South Africa on bone-in chicken imports from the EU. It will decrease to 15% over 4 years between March 2021-2022. Brazil and the US are strong competitors in the sector where the EU has lost some of its market share.

[24] Joint Report of the 2nd Meeting Of The Trade And Development Committee Of The Economic Partnership Agreement Between The European Union And The Southern African Development Community (SADC) EPA States, 21 October 2017, Brussels: <http://trade.ec.europa.eu/doclib/docs/2017/october/tradoc_156355.pdf> accessed 04 May 2019.

[25] South Africa: South Africa Extends Safeguard Duty on EU Bone-in Broiler Meat, 22 October 2018: <https://www.fas.usda.gov/data/south-africa-south-africa-extends-safeguard-duty-eu-bone-broiler-meat> accessed 04 May 2019.

[26] Gerhard Erasmus and Willemien Viljoen: The Battle over Safeguards on Poultry Imports from the EU continues, September 2017: <https://www.tralac.org/discussions/article/12101-the-battle-over-safeguards-on-poultry-imports-from-the-eu-continues.html> accessed 04 May 2019.

[27] Ibid.

[28] WA - EU EPA, art 65(3) and art 66(6).

[29] Treaty establishing the European Economic Community (EEC Treaty, hereafter Rome Treaty) Signed in: Rome (Italy) 25 March 1957. (Entry into force: 1st January 1958), art 181.

[30] Treaty of Lisbon amending the Treaty on European Union and the Treaty establishing the European Community (OJ C 306, 17.12.2007); (entry into force on 1 December 2009) (hereafter Lisbon Treaty), art 272.

[31] C-274/97 Commission v Coal Products; T-401/07 Caixa Geral de Depósitos v Commission; C-43/17 P Jenkinson v Council and Others, etc.

[32] J. Gillis Wetter, 'The International Arbitral Process, Public and Private' (1979) Vol. II, 288, cited in Jeff Waincymer, Part I: Policy and Principles, Chapter 1: The Nature of Procedure and Policy Considerations, in Procedure and Evidence in International Arbitration, Volume 4 (Kluwer Law International 2012).

[33] Waincymer, ibid, 8.

[34] WA - EU EPA, art 81 (2).

[35] CA, art 98.

[36] CA, art 38A.

[37] CA, art 98.

[38] WA - EU EPA, art 80.

[39] WA - EU EPA, art 84 (2).

[40] WA - EU EPA, art 84 (3).

[41] WA - EU EPA, art 84 (1).

[42] J. Mair, 'Equal treatment of Parties in the Nomination Process of Arbitrators in Multi-Party Arbitration and Consolidated Proceedings' Austrian Review of International and European Law Online, 1 January 2010, pages 59-82. J-Louis Delvolvé, 'Multipartism: The Dutco Decision of the French Cour de cassation' (1993, June) 9 (2) Arbitration International 197-202.

[43] International Chamber of Commerce (ICC) Rules of Arbitration, art 10; Belgian Centre for Mediation and Arbitration (CEPANI) art 9; UNCITRAL Arbitration Rules, art 7, etc.

[44] London Court of International Arbitration (LCIA) Rules have three-person tribunal as the maximum number.

[45] Siemens AG and BKMI Industrienlagen GmbH v Dutco Construction Co., Cour de Cassation, Jan. 7, 1992.

[46] R. Ugarte & T. Bevilacqua, 'Ensuring party equality in the process of designating arbitrators in multiparty arbitration: An update on the governing provisions' (2010) 27 (1) Journal of International Arbitration 9-49, 2010.

[47] The First Yaounde Convention (1963-1969) - OJ 093, 11/06/1964 P. 1431, signed on 20 July 1963, end of validity: 31/05/1969 (hereafter YC I); Expiry in 1969 with a renewable term of five years. Art 51.

[48] Eric C. Djamson, The Dynamics of Euro-African Co-operation Being an Analysis and Exposition of Institutional, Legal and Socio-Economic Aspects of Association/Co-operation with the European Economic Community (Martinus Nijhoff/The Hague 1976).

[49] There are 48 countries from Sub-Saharan Africa, 16 from the Caribbean and 15 from the Pacific. <http://www.acp.int/content/secretariat-acp> accessed 06 May 2019.

[50] WA - EU EPA, art 88.

[51] WA - EU EPA, art 89.

[52] WA - EU EPA, art 90 (3): 'Nothing in this Agreement shall affect the rights and obligations of the Parties under any tax convention. In the event of any inconsistency between this Agreement and such a convention, the convention shall prevail to the extent of the inconsistency.'

[53] WA - EU EPA, art 28.

[54] Case C-409/10 Hauptzollamt Hamburg-Hafen v Afasia Knits Deutschland GmbH [2010] ECLI:EU:C:2011:843.

[55] Regulation (EU) No 952/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 9 October 2013 laying down the Union Customs Code (recast) (hereafter Customs Code).

[56] This refers to an exception to the obligation of import or export duty repayment covered under Article 239 of the Customs Code, and Article 905 of Commission Regulation (EEC) No 2454/93 of 2 July 1993 laying down provisions for the implementation of Regulation No 2913/92 (OJ 1993 L 253, 1), as amended by Commission Regulation (EC) No 1335/2003 of 25 July 2003 (OJ 2003 L 187).

[57] See the following judgments: Case C-204/07 P, C.A.S. v Commission [2008] EU:C:2008:446; Case C-574/17 P Commission v Combaro [2018] EU:C:2018:598; and Case C-589/17 Prenatal S.A [2019] ECLI:EU:C:2019:104, Opinion of Advocate General Sharpston delivered on 7 February 2019(1).

[58] In Case C-175/12 REQUEST for a preliminary ruling under Article 267 TFEU from the Finanzgericht München (Germany), made by decision of 16 February 2012, received at the Court on 13 April 2012, in the proceedings Sandler AG v Hauptzollamt Regensburg, [2013] ECLI:EU:C:2013:681, para. 50. [Per curiosum, the Court chamber was composed of Hungarian judges: E. Juhász, President of the Tenth Chamber, A. Rosas and C. Vajda (Rapporteur), Judges].

[59] WTO Dispute Settlement Reports and Arbitration Awards: https://www.wto.org/english/res_e/publications_e/ai17_e/tableofcases_e.pdf accessed 25 May 2019.

[60] China - Measures Imposing Anti-Dumping Duties on High-Performance Stainless Steel Seamless Tubes (HP-SSST) from the European Union AB-2015-5 - WT/DS460 Appellate Report: https://docs.wto.org/dol2fe/Pages/FE_Search/FE_S_S006.aspx?DataSource=Cat&%3bquery=%40Symbol%3dWT%2fDS454%2fAB%2fR*&%3bLanguage=English&%3bContext=ScriptedSearches&%3blanguageUIChanged=true (accessed 25 May 2019.)

[61] WT/DS460 (n 60), EU Panel Report, (n 60), para. 7.236.

[62] WT/DS460 (n 60), EU Panel Report, para. 7.235 and fn 396 thereto. (fns 395 and 397 omitted) cited in WT/DS460/AB/R, 54.

[63] WT/DS460/AB/R, (n 60) China's appellee's submission, para. 333.

[64] WT/DS460/AB/R, (n 60) para. 5.128.

[65] WT/DS460 (n 60), Appellate Body Report, China - GOES, para. 240.

[66] WT/DS460/AB/R, 53.

[67] Panos Merkouris, 'Interpreting the Customary Rules on Interpretation' (2017) 19 (1) International Community Law Review 134-135, https://doi.org/10.1163/18719732-12341350 (This is an interesting study on the overall interpretation process by courts and tribunals and the WTO DB on customary international law).

[68] WT/DS460/AB/R, 54.

[69] Up until the issue of interpretation on Art. 6.9., the Appellate Body upheld the first set of the Panel's findings.

[70] WT/DS460/AB/R, 105-107.

[71] Nnamdi and Iheakram (n 11) 16.

[72] Ibid.

[73] WTO, Understanding on Rules and Procedures Governing the Settlement of Disputes, art 11.

Lábjegyzetek:

[1] The author is a qualified lawyer admitted to the Nigerian Bar. She wishes to thank dr. Éva Gellérné Lukács for her academic guidance, support, and the opportunity to publish this article. (email: dfakinyooye@gmail.com).