Nimród Mike (LL.M., CIPP/E): Security or Privacy? Shuffling the Puzzle of Blockchain Compatibility with the EU-GDPR (IJ, 2019/1. (72.), 34-38. o.)

1. Introduction

Blockchain is a distributed database, which maintains a list of records that goes on increasing continuously known as blocks that are secured from tampering and revision.[1] The technology of blockchain was conceptualized by Satoshi Nakamoto in 2008 and implemented as a main component of the digital currency Bitcoin.[2] Therefore, it is solely understandable that this relatively new technology is associated to financial transactions. Nonetheless, the advantages of blockchain technology can be fruitfully exploited in other industries as well (i.e. smart contracting, licensing, supply-management, asset management, identity provider, insurance and fund-raising).[3] Utmost care should be taken on the use of proper terminology. While blockchain is a new approach of performing transactions in a trackable manner, Bitcoin in itself is a digital currency, enabled by the invention of blockchain.

In the meantime, the protection of personal data has become increasingly important with the adoption of the new EU-GDPR[4] legislation. The Regulation adopted by the EU lawmakers has its merits on detailing certain parts of the already known celebrities of data protection principles (i.e. Integrity and Confidentiality) and brings new methodological fits for data controllers to assess data security and data privacy levels from the earliest stages possible (i.e. Data Protection by Design and Default; Data Protection Impact Assessment).

This paper has its scope of analyzing the compatibility of blockchain technology with the EU-GDPR. In the first section general ideas are presented on the functionalities of blockchain (2), due to the importance of grasping the nature of the phenomena. In the following chapter a systematic approach should be taken towards identifying personal data in the blockchain and its relation to the data protection principles (3). This chapter should also discuss certain roles of the blockchain ecosystem and rights of data subjects related to their personal data. Finally, a conclusion has to be drawn pointing out possibilities for future work (4).

2. Review of Blockchain

As it was concluded in the doctrine:

a blockchain is a nothing but a decentralize database that requires blending of different kinds of technologies ranging from peer to peer networks to consensus mechanism, including public-private key cryptography. Consensus mechanism is the backbone of the Blockchain. To understand correctly that which kind or type of blockchain is being used by a particular network, the consensus mechanism is sufficient to utter the nature of the same. The Blockchain uses the cryptographic protocol in which a number of computers, generally called nodes, are allowed to form a network for sharing the information or maintaining the ledger.[5]

Common characteristics of a Blockchain are decentralization, openness or transparency, as well as data integrity achieved through encryption.[6] To the before-mentioned characteristics some add immutability as a distinct one.[7] This might seem like the recipe for a perfect data protection tool as GDPR places emphasis on demonstrating compliance. Blockchain's transaction transparency and immutable fabric provides an integrity assured audit trail for recording how personal data were processed and shared.[8] And it must be admitted that indeed, cryptography is extensively used in blockchain.[9] The result is that the vast majority of the data undergone processing throught the network is encrypted. Encryption is recognized and thus encouraged by GDPR Article 32 Par. 1(a) as a secure processing mechanism of personal data. Although, it covers personal data, since no anonymization techniques are applied towards the collected and stored data.

2.1. Decentralization

Blockchain in essence distributes the control to all peers in the transaction chain instead of having one central authority controlling everything within an ecosystem.[10] Thus the technology works on the principle of a shared infrastructure. Figure 1 accurately shows the difference between centralized, partly decentralized and fully decentralized blockchains.

Figure 1. Type of Ledgers[11]

Decentralizing control over peers in the chain leads to significant boost in consumer trust. The novelty of this technology resides in the fact that it eliminates the so-called Trusted 3rd Parties, that are centralizing all the transactions and storing them in one data-base. Eliminating such intermediaries translates into enhanced security and brings economic incentives as well, cutting out unnecessary costs. Beyond cost efficiency, transactions are also faster than those performed by any intermediary.

With regard to enhanced security, it is worth noted the distributed or decentralized ledger holds up to a great achievment. The thinking behind the Blockchain approach affords participants with huge redundancy, meaning that an attacker will have to compromise a great many of the distributed ledgers before they can have any impact on the ledger contents.[12] Indeed, considering that consensus among participants is needed for new blocks to be added to the chain, should give high confort towards the veracity of its content. It also supports on documenting provenance of newly recorded events.

2.2. Openness

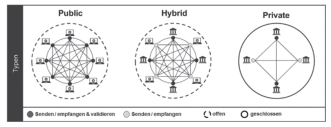

The concept of openness is highly dependent on the type of blockchain implemented. By default not all kinds of blockchains based solutions are open to all participants. The distinguishment between permissioned and permissionless blockchains had been associated with this characteristic of blockchains. Based on the "law of permission" permissionless, permissioned, consortium or hybrid blockchains were classified separately. Figure 2 explains the difference between these.

- 34/35 -

Figure 2: Diagrams of different modes of Blockchain[13]

In a permissionless and public blockchain, all the participating nodes, in the network, have to validate the transaction, and for doing so each node has the right to read and write the transaction.[14] Best known exemples of public blockchains are Bitcoin and Ethereum. Bitcoin has its own contribution on the invention of blockchain-based crypto-currency, meanwhile Ethereum earned some landmark achievements on the field of smart contracting, based on event-condition-action approach.

It is worth noted, that what makes a blockchain permissionless is the consensus mechanism. While in case of public chains, all nodes have to validate the transaction, in the permissioned blockchains, only a selected group of nodes do this job and only they have the right to write.[15] This selected group of nodes are often called Miners.

On the other hand, the consortium or hybrid blockchain borrows some properties from both the public and private blockchain models. Usually participant nodes to a hybrid blockchain can have writing rights only, and it is case-dependent whether reading rights can be assigned publicly or not. As it was suggested by some authors, a hybrid blockchain might be suitable for diverse institutional collaborations especially for the creation, reviewing, and verifying transactions, by a permitted group of nodes[16]. A clear position on blockchain typology was shown by Salmensuu depending on different types of blockchains according to the validator and access criteria, as illustred by Figure 3.

A teljes tartalom megtekintéséhez jogosultság szükséges.

A Jogkódex-előfizetéséhez tartozó felhasználónévvel és jelszóval is be tud jelentkezni.

Az ORAC Kiadó előfizetéses folyóiratainak „valós idejű” (a nyomtatott lapszámok megjelenésével egyidejű) eléréséhez kérjen ajánlatot a Szakcikk Adatbázis Plusz-ra!