Eva Tomásková[1] - David Sehnálek[2]: The Hierarchy of Legal Sources - Relation between International Treaties Concluded with Third States by the EU and by the Member States (JÁP, 2011., Különszám, 189-195. o.)

I. Issues to be addressed in this study

In our study we would like to deal with and clarify the relation between international agreements that have been concluded by the European Union and a third country on side and a Member State and a third country on the other side. This issue is not only hypothetical. The European Union nowadays exercises many competences that use to belong to its Member States. Thus, a situation may occur where the Union has concluded an international agreement of the same scope as has some other international treaty[1] that was previously concluded by the Czech Republic before its accession to the European Union. Starting points of our study are following:

There exist two international treaties;

• Both these treaties have at least partially the same scope;

• One of these treaties was concluded by the European Union and a third state;

• The other treaty was concluded by a Member State and a third state prior the accession of the respective Member State to the European Union.

The question is:

• What is the legal relation between these two international treaties?

• Does the principle of primacy of the European law apply in this case?

• And if so shall the agreement to which the European Union is a party take precedence over the treaty concluded by the Czech Republic?

• Or do we have to use principles and propositions relating to the hierarchy of sources as they are set by the international public law?

These questions will be examined in this article in order to find the answer on question of hierarchy of norms and mutual relations among the three legal systems. The analysis will be done from the viewpoint of the Czech Republic and its law with the emphasis on European law.

- 189/190 -

II. Introduction

Historically, two major systems of law have developed - the state law and the international law. Each of them hasits unique characteristics and its own sources of law. Both systems are rather independent as their main purpose is initially significantly different. The main objective of the state law is to regulate relations within the society of a respective state which, of course includes individuals whereas the international law regulates primarily relations among states and subsequently also international organization.

The further development of international relations, however, has changed this. The truth is that the international law even nowadays regulates relations among subjects of international law. Nevertheless, individuals play more and more important role as some of the norms of international public are addressed to them either directly[2] or indirectly[3]. This fact creates a problem of mutual relations between the state law and international law, and a question of possible effects of international public law on individuals where they are addressees or beneficiaries of international law. This is especially important where the norm of the international law is in conflict with a rule of state law. The question for national courts is whether they should apply the rule of international law or of the state law?

Traditionally, this problem of mutual relation and possible conflicts is solved by a state law. Thus, it is the state law that sets, with some exceptions, principles of application of the international public law. The approaches may vary between two opposites - monism and dualism. According to the first one, in its most pure form, the law forms a unity where international public law is directly applicable, has higher legal force as well as precedence over the national law including the constitution of the respective state. Dualism on the other hand requires sources of the international law to be incorporated to the state law. Without such incorporation they are not directly applicable and cannot have any effect against individuals.

With the European Union, things have become more complicated. European Union has formed its own legal order, which is independent on both the state and international law. Thus, with the European law new relations must be taken into the account:

1. The relation between the European law and international law; and

2. The relation between the European law and a state law.

- 190/191 -

III. Czech law and international law

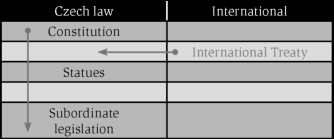

In the Czech Republic, the relation between the Czech law and international law is solved by the article 10 of the Czech Constitution according to which promulgated treaties, to the ratification of which Parliament has given its consent and by which the Czech Republic is bound, form a part of the legal order; if a treaty provides something other than that which a statute provides, the treaty shall apply.[4] In this article the Czech Constitution expresses the monistic approach to the international law. In other words, certain treaties have direct effect in the Czech Republic and in case of conflict with the Czech law they should take precedence over Czech statutes. The situation could be graphically expressed as follows:

Table 1: Relation between Czech law and international law

Important thing is that the Czech Constitution does not solve a question of legal force between the two systems as both legal orders are considered to be independent. Thus, the conclusion of this part is that the legal order applicable in the Czech Republic actually consists of two independent legal orders which shall be applied concurrently. The issue of legal force can be solved only within each system, each of them has also its own rules in this respect, and the mutual relation between them is set in the Czech law partly in favor of the international law save for the constitution.

IV. Czech law and European Union law

Unlike the international law, the European law has its own principles of application in Member States - the principle of direct effect and the principle of primacy, both set by the Court of Justice of the European Union in its well-known case

- 191/192 -

law. Thus, the rules contained in the Constitution do not apply in case of the European law including the founding treaties despite the fact that these treaties[5] wereinitially a source of international law.[6]

Please note that rules contained in the Czech Constitution are activated only when the founding treaties are subject to an amendment or a change as was for example case of the Treaty of Lisbon. It is the Czech law and its constitutional rules that set the procedure of ratification of such treaties but once again not their application.

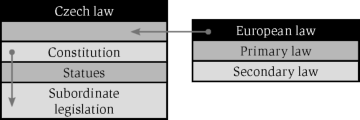

The mutual relation between the Czech law and European law could be graphically expressed as follows:

Table 2: Relation between Czech law and European law

And again, the relation between the Czech law and Union law is a relation between the two mutually independent legal orders, thus the European law does not have a higher legal force than the Czech law.[7]

V. European Union law and international law

Things are becoming more complicating when we take into consideration the fact that the European Union has also the power to negotiate and conclude international agreements which it often exercise especially in the area of the common commercial policy. Thus we have to solve the same problem which is solved by

- 192/193 -

state law, in case of the Czech Republic by the fore mentioned article 10 of the Constitution.

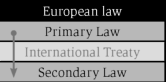

Unfortunately, the European law itself does not provide for an express answer on this issue. The only article which partly deals with this question is the article 216 of the Treaty on Functioning of the European Union which provides that "agreements concluded by the Union are binding upon the institutions of the Union and on its Member States". As we can see, there is no rule on mutual relations between the international and European law in this article. The absence of a specific provision forced the Court of Justice of the European Union to formulate its own rules on this matter. This question was for the first time raised in the case known as International Fruit Company. In this decision the Court of Justice ruled that the validity of measures taken by the institutions may be judged with reference to a provision of international law when that provision binds the Community and is capable of conferring on individuals rights which they can invoke before the national courts. In other words the Court of Justice considers that it can examine the validity of secondary Community legislation in the light of an international agreement. From this one can conclude that according to the Court of Justice the international agreements are a part of the European law with a higher legal force than the secondary law but lower than the primary law.[8]

The relation of the European law and international agreements as a source of international law could be graphically expressed as follows:

Table 3: Relation between International law and European law

VI. European law, international law and state law all together

Let's make a synthesis now. But first we would like to highlight once again, why this is for us so important. It is because a situation may occur where an international agreement concluded by the European Union may provide for something else than an international treaty concerning a same topic that was concluded by a Member State. The question is which shall prevail. Because de iure both these treaties are also a sources of international law. And as we know the international law has specific rules that solve potential conflicts of its sources.

- 193/194 -

The solution is different from the perspective of the international law and the European law. From the viewpoint of the international law the important thing is that European Union and Member States are different subjects of law. Thus, the basic rule lex posterior derogat legi priori cannot be used. And from the perspective of the European Union is important the fact that the relation between the Member State and European Union is set by European law. And the Union's aim is to ensure the uniform and effective application of its law, including the agreements.

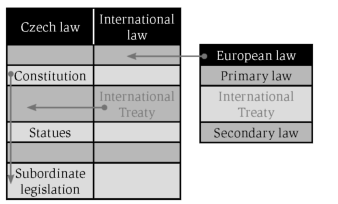

In order to find an answer on this question we must put all the fore-mentioned schemes together. The result can be seen on following scheme:

Table 4: Relation between Czech law and European law in detail

As we can see the principle of primacy of European law and the Article 216 of the TFEU cause that not only primary and secondary European law but also international agreementsconcluded by the European Union take precedence over the conflicting state law. Important thing is that, as the Court of Justice does not recognize any exceptions from the principle of primacy, they shall prevail even over the constitutional law of Member States and rules contained in it. And again, this rule cannot be found in any article of the primary law but it was set in the case law of the Court of Justice.

VII. Practical impacts

We have mentioned previously that the central question which we are trying to answer in this study is not only theoretical. The European Union has already concluded a multilateral agreement which could be potential source of problems. Such anexample may be the Convention on the International Recovery of Child Support and other Forms of Family Maintenance. Please note, that there had been concluded several bilateral international treaties by Member States in the same

- 194/195 -

area prior this Haague Convention. And the question is which shall take the precedence - the bilateral agreement or the agreement negotiated by the Union?[9] The answer is not easy as a third party is involved. From the viewpoint of the Union and the Union law the first logical answer would be to give precedence to the agreementconcluded by the European Union. However, from the viewpoint of this third party the basic legal principle pacta sunt servanda should be taken into the account. The Treaty to which such state is a party shall not be avoided by simple reference to the primacy of the European law over the national law as this issue is only an internal matter of the European Union and its Member States. Relations to other states are in case of Union as well as its Member States regulated by the international law which is independent on the European law.

VIII. Solution and conclusion

This problem is addressed by the European Union in the Art. 351 of the TFEU. This article states that rights and obligations arising from agreements concluded before the date of the accession, between one or more Member States on the one hand, and one or more third countries on the other, shall not be affected by the provisions of the Treaties.[10] The term Treaties must be of course interpreted in a broad meaning covering also the secondary law and international agreements concluded by the European Union. In other word such treaties can be still applied by the respective Member States until they are terminated.

The conclusion is that the problem of conflicting international treaties is not solved using the principles and rules of the international public law but by the European Union law itself. However, the European law must give respect to international commitments of Member States. Since the obligations of Member states toward third states must be respected the former international treaty concluded by the respective Member State will apply. This situation is a nice example of an exception from the principle of the primacy of the European law over the national law. ■

NOTES

[1] The international treaties concluded by the European Union are in the European law referred to as the "international agreements" and the term "treaty" is reserved just for the founding treaties of the Union. That is why we will use both terms in this study in order to follow both the EU terminology (in case of treaties concluded by the Union) and the traditional terminology of the international law (in case of treaties concluded by states).

[2] Which is for example a case of norms adopted in order to protect human rights.

[3] Which is for example a case of norms which are addressed to states and individuals are their beneficiaries, for example in the area of international trade etc.

[4] Originally, the wording of this provision was different. The Article 10 provided that: ratified and promulgated treaties concerning the fundamental rights and freedoms by which the Czech Republic is bound are directly applicable and shall have primacy over statutes. Thus, the precedence of an international treaty over the Czech law was possible only in case of some of them.

[5] Treaty on European Union (hereinafter referred to as the "TEU") and the Treaty on Functioning of the European Union (hereinafter referred to as the "TFEU").

[6] Unlike the "Constitutional Treaty" the recent wording of the TEU a TFEU after the Lisbon Treaty does not contain any provision similar to Article I-13. Thus the principle of primacy is still legally based only on case law of the ECJ. However, its recognition by Member States is strengthened by the fact that a special declaration was attached to the TEU and TFEU. This declaration was ratified together with abovementioned Treaties which implies tacit acknowledgement of the principle of primacy by Member States. For more information on this topic see Chalmers, D., Monti, G. European Union Law Updating Supplement. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008, p. 50.

[7] See also Tichy, L, Arnold, R., Svoboda, P., Zemánek, J., Král, R. Evropské právo. 3. vydání, Praha: C. H. Beck, 2006 since p. 285; Tyc. V. Pusobení práva Evropské unie ve sfére ceského právního rádu - Úvodní studie in Sborník z workshopu konaného na Právnické fakulte MU v Brne dne 26.9.2006 Evropsky kontext vyvoje ceského práva po roce 2004, Brno, Masarykova univerzita, 2006, pp. 10 -28.; Svoboda, P. K povaze práva Evropské unie. Právník, 1994, c. 11. p. 940.

[8] See also Malenovsky, J., Mezinámdní právo verejné: jeho obecná cást a pomer k jinym právním systémum, zvláste k právu ceskému. 5., podstatne upravené a doplnene vydánî, Brno : Masarykova univerzita, 2008. p. 533.

[9] The problem of conflict may likely happen as Member States are often the ones who ensure the implementation of EU measures including those related to international agreements concluded by the EU. See also Baere De Geert, Constitutional Principles of EU External Relations. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 2008. p. 91.

[10] Hartley states that the word "rights" refers to rights of the non-Member State and the word "obligation" refers to the obligation of the Member States which could mean the rights of Member States may be affected by the EU law. See Hartley TC, The Foundations of European Community Law, Sixth Edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 2007. p. 96.

Lábjegyzetek:

[1] A szerző assistant professor, Masaryk University Department of Financial Law and Economics.

[2] A szerző lecturer, Masaryk University Department of International Law and European Law.