Rachel Wall[1] - Alistair Jones[2]: Combined Authorities: A Loss of Urban Identity or Urban Imperialism? (Annales, 2017., 141-159. o.)

https://doi.org/10.56749/annales.elteajk.2017.lvi.9.141

Abstract

The aim of this paper has been to examine the impact that the process of establishing combined authorities has had on existing political relations between local authorities and senses of identity on an empirical basis. The research has demonstrated how this process rests upon but also can have a significant impact on local politics.

Keywords: England, local governance, urban identity, urbanisation, municipal administration, unitary authorities, combined authorities

I. Introduction

As a result of devolution to Scotland, Wales, Northern Ireland and London, the UK government turned its attention to the rest of England and created a new, centrally inspired legislative framework within which devolution would take place. The latest wave of reform is focused on governance structures and a form of territorial re-scaling with the creation of combined authorities, headed by elected mayors. Combined authorities are created where groups of councils enter negotiations with government to agree the devolution of powers and finances through a 'devolution deal'. The new legislative framework for devolution in England provides councils with opportunities to create a bespoke devolution deal for their areas, which reflects local needs and identities. While this new legal framework makes provisions for devolution deals and combined authorities to be established in urban and rural England, the process has been predominantly city-centric and focused on urban centres and their surrounding rural areas.[1]

- 141/142 -

The process of rescaling governing structures at the local level has implications for existing political relationships and for existing territorial boundaries[2] and how the local political elite identifies with these boundaries - many of which are quite artificial constructs as a result of numerous territorial reforms - while local areas are being combined into new 'super authorities'. Political relations between councils are being tested, as municipalities within these wider metropolitan regions seek to establish new institutions in which they can effectively govern their own localities and simultaneously govern collectively across multiple geographical boundaries. The creation of these new governance structures has implications for where power will lie within combined authorities, where different tiers of local government and different territorial interests (urban and suburban/rural) will have decision-making capacity and how existing territorial identities will be tested, as these sub-regional governing entities are established and senses of place are challenged.

In exploring these implications, the paper will address the following questions:

- What will be the impact of this territorial re-scaling of local government on political relations between municipalities within the new metropolitan regions?

- How will the existing territorial identities within the municipalities comprising the combined authorities respond to these structures?

The paper will retrace the ongoing policy debates of local government reform in England, and how these debates find relevance in academic discussions of territorial reform, territorial identity and metropolitan governance reform. As such, an analytical framework is developed through which to begin to examine the case of Leicester and Leicestershire. The paper will provide an understanding of the critical political and territorial challenges posed by the current devolution agenda in England for a city locked within a metropolitan region.

The next section of the paper will retrace the reorganisation of local government in England since the 1960s in order to illustrate the development (or the absence) of metropolitan governance structures and how they have led to the current devolution process. The second section will set out government thinking on devolution to provide a policy-oriented framework for the paper. The third section will discuss some of the relevant concepts relating to political relations between councils and territorial identity. The penultimate section will present the case of Leicester and Leicestershire and will discuss the findings of documentary analysis, in addition to early empirical research conducted with 12 county, city and district councillors. The final section will draw together conclusions from research conducted to date and present considerations on future directions of the research in terms of a longer PhD project examining the local politics of devolution to English local government.

- 142/143 -

II. Methodology

The paper is based on research conducted as part of a continuing PhD research project and is therefore an early reflection of the development of in-depth case studies as part of a more long-term PhD thesis. The research consists of 12 semi-structured interviews conducted with county, city and district councillors situated within the combined authority area examined in this paper. The data is supplemented by documentary analysis as well as findings from other relevant research projects which have examined the views of councillors in relation to the current devolution process taking place in England. During the period in which the empirical research was conducted, two significant political events were taking place in England, local county elections and a general election. These events had implications for access and, as such, the sample of councillors interviewed is smaller than originally envisaged and further empirical research is required in order to develop further the findings and conclusions within this paper.

III. The rescaling of local government in England: towards metropolitan governance?

The habitual rescaling of local government structures in England has resulted in a long period of institutional instability whereby, with local government having no constitutional right to exist and a lack of autonomy, central government has imposed and continues to impose significant changes on the size, scope and structure of local government in England.[3] The ongoing orthodox assessment, which been in place since the 1960s regarding the appropriate size and scale of local government structures in England, has been dominated by attempts to reconcile the dual-purpose nature of local government.[4] Such debates focus on attempting to strike a balance between ensuring efficient service delivery and maintaining the democratic quality of local authorities.[5]

- 143/144 -

As Table 1 below demonstrates, local government in England has, as a consequence of numerous central reforms, seen a continued reduction in the number of authorities. The table however, must be read with some caution, as it is not a comprehensive listing of all Acts of Parliament that have re-organised local government; rather, the table is indicative and illustrative of the overall process of amalgamations. What the table also shows is how, with a simple legislative change by the centre - and since the 1990s by secondary legalisation - local government units.

Table 1. The Legislative Rescaling of Local Government in England

| Act | Effect |

| London Government Act 1963 | Greater London Council and 32 London boroughs |

| Local Government Act 1972 | Reduced 45 Counties to 39; Replaced 1086 urban and rural districts with 296 District Councils; Abolished 79 County borough Councils; Created 6 Metropolitan County Councils; Replaced 1,212 councils with 378 |

| Local Government Act 1985 | Abolishes 6 metropolitan councils and the GLC |

| Local Government Act 1992 | Results in: 34 County Councils, 36 Metropolitan Borough Councils; 238 Districts; 46 Unitary councils |

| 2009 re-organisation under the provisions of the 1992 Act | Reduced 44 councils to nine across seven English county areas |

Source: Copus et al., Local Government in England... (amended)

The reorganisations of local government since the mid-1970s by successive Conservative and Labour governments have rested on assumptions and beliefs within central departments and selected external bodies.[6] Those beliefs are that, despite unitary local government not being the norm across the rest of Europe, large single-unit municipal authorities can deliver economies of scale, for which evidence is mixed at best.[7] In assessing recent developments of English local government, it is clear that while units of local government have grown in size, they have shrunk in many other aspects; functions have been removed, resources have declined, administrative workforces have been reduced while the intensity and complexity of local needs have increased significantly.[8]

- 144/145 -

Carr[9] reminds us that the manner in which central state legislation determines the scope, autonomy and size of local government is significant in shaping the behaviour of the local political elite. In order to determine just how far-reaching this influence is on the current devolution process, it is important to consider how these policy debates (in England) have travelled and in what way they serve to inform or are reflected in the current devolution policy being implemented. For the purposes of this paper, the journey of reform of London's government and the subsequent policy debates are excluded from the analysis and discussion. The history of local government in London is one that can and has warranted research and publications of its own, and the path of reform has often not occurred in parallel with local government reform throughout the rest of England. London, in the case of local government reform, and so much else, is another country. As such, this paper focuses on solely on local government reform outside of the capital.

1. The Redcliffe-Maud Report: a push for unitary local government

While the current devolution reforms across England have been declared revolutionary by their main architect, former Chancellor of the Exchequer George Osborne, the fundamental principles which underpin combined authorities can be traced back to the local government reforms of the 1960s. The Royal Commission on Local Government (1966-1969), under the chairmanship of Lord Redcliffe-Maud, made a radical set of recommendations for a complete overhaul of the size, structure and functional capacity of local government in England (with the exception of Greater London, which was the subject of the preceding Herbert Commission). The Redcliffe-Maud report broadly recommended that England, under the umbrella of 8 regional provinces, be divided into 61 new local government areas which facilitated an interdependence between urban towns and the rural country. Of these new unitary authorities, it was proposed that there should be three metropolitan areas (Birmingham, Liverpool and Manchester). The figure below sets out the Redcliffe-Maud report's proposed structure for local government in England. As discussed further in this section, these reforms were not largely implemented, only proposed.

- 145/146 -

Figure 1. Redcliffe-Maud recommendations for local government structure in England (1969)

8 Provincial Councils (Regions)

| 58 Unitary Authorities | 3 Metropolitan Authorities (Liverpool, Greater Manchester and West Midlands) |

| Metropolitan Districts |

Communal Councils (Civic Parishes)

Source: Authors own diagram

The rationale underpinning the recommendations of the Maud Commission centred around the notion that not only were existing local authorities too small, but also that the administration and delivery of services in rural and urban areas are interdependent and, therefore, should be delivered by a single authority. The existing administrative fragmentation between counties and county boroughs was deemed to breed 'ambitions and fears' over boundaries and an undesirable hostility between tiers of local government.

It is within the Redcliffe-Maud report that the idea of 'city-regions' as a form of local government was first introduced into mainstream policy debates on local government structures in England - a concept which clearly underpins the current combined authority model in England. The report describes city-regions as:

A conurbation or one or more cities or big towns surrounded by a number of lesser towns and villages set in rural areas, the whole tied together by an intricate and closely meshed system of relationships and communications, and providing a wide range of employment and services.

While the Labour government at the time under Harold Wilson broadly accepted these recommendations (with the addition of more metropolitan authorities), any attempt to implement the proposals formally was halted by the Conservative Party's general election victory in 1970; it was elected on a manifesto which committed to a two-tier structure for local government.

- 146/147 -

2. Local Government Act of 1972: the two-tier system

The commitment to a two-tier system, which placed an emphasis on respecting existing historical boundaries, was implemented through the Local Government Act of 1972. The Act retained the Redcliffe-Maud model of two-tiered metropolitan authorities, although the geographic boundaries took in less of the surrounding rural areas than originally proposed - a political move which sought to control predominantly Labour urban centres from exerting too much influence over the surrounding Conservative localities.[10] These new metropolitan counties covered Greater Manchester, Merseyside, South Yorkshire, Tyne and Wear, West Midlands and West Yorkshire. The Act made provisions for the rest of England to be governed by two-tiered authorities. The Act also stipulated a minimum population size for districts of 40,000 residents, a clear reduction of the Redcliffe-Maud suggestion of 250,000.

3. Abolishing the Metropolitan Counties

The metropolitan authorities had experienced a short life before they were abolished only 13 years later by the Thatcher government in 1986. This Act effectively turned the lower-tier metropolitan districts into unitary authorities. The majority of functions were devolved to the new unitary councils, with three authorities now holding city status.[11] While unitary councils are generally responsible for running their own services, some county-wide structures for service delivery still remain even now.[12] These joint boards, which are residual structures from the upper metropolitan counties, are made up of councillors who are appointed to these bodies by their respective council. This abolition of metropolitan government across England was, much like their inception but only in parallel, perceived to be a highly political move which served to benefit the government of the day; specifically, to address the growing tensions over public spending between the largely Labour-controlled metropolitan counties and the Conservative Thatcher government.

The Banham Commission of the early 1990s focused on English local government, excluding London and the old metropolitan counties. While the post-Thatcher

- 147/148 -

Conservative Government tried to steer the Banham Commission towards the introduction of unitary authorities across England, Banham did not play ball. Instead, there was a mixture, where some unitary authorities were introduced (e.g. the city of Leicester), and tiered authorities were retained elsewhere (e.g. the remainder of Leicestershire). Interestingly in the case of Leicester and Leicestershire, the status quo of a straight two-tiered structure was not considered as an option.

Indeed, policy debates surrounding the shape of English local government and, more specifically, the shape of metropolitan government in England have corresponded with the development of academic understandings and conceptualisations of metropolitan governance reform. As such, the debate has been dominated by the two traditional schools of thought; the Metropolitan Reform Tradition (MRT) and the Public Choice Perspective (PCP).[13] Consequently, the circular debate of local government reform in England can be characterised as being dominated by two narratives; i) MRT: local government is too fragmented and inefficient and, thus, must be amalgamated into larger units; and, ii) PCP: fragmentation enhances competition and, hence, local government would benefit from smaller units with greater capacity for local self-governance.

The next section of this paper will outline the more recent development of the current devolution policy being implemented in England, in order to identify whether we are experiencing a shift away from traditional, circular debates of size and efficiency, towards something more closely aligned to a 'New Regionalism' approach to metropolitan governance.

IV. Devolution and combined authorities: revolution, evolution or convolution?

formal structures of regional governance - and, by extension, metropolitan governance -are somewhat of a novelty to England; as we read in the previous section, where formal structures of metropolitan governance have existed, they have only done so for very brief periods at the expense of the political expediency of central government. The more recent attempts at establishing a formal structure of elected regional governance in England has proved unsuccessful. In considering the recent development of combined authorities, a meaningful point to begin would be the creation (and later abolition) of the Regional Development Agencies (RDAs) during Tony Blair's Labour Government (1997-2007), which enjoyed little popularity among the demos.[14] Since this unsuccessful attempt

- 148/149 -

to establish democratically elected regional governance in England, there has been a significant shift from devolution focused on delivering democratic accountability at a sub-national level, to devolution that centres on economic objectives and delivering growth.[15] Amongst the large volumes of Acts of Parliament within recent decades that impact on local government, there are some recent pieces of legislation and government policies which are directly relevant and have arguably helped to formulate and shape the current devolution agenda in England.

First, the Local Democracy, Economic Development and Construction Act 2009 made provisions for the establishment of combined authorities, meaning that a group of local councils in any given area, providing there is consensus between them, could pool appropriate responsibilities and receive certain functions from central government, limited to transport and economic development. The Cities and Local Government Devolution Act 2016 introduced amendments to the 2009 Act by removing statutory limitations on which powers could be devolved and made provision for the introduction of directly elected mayors to combined authorities.

In a continued pursuit for local economic growth in England, the Coalition Government (2010-2015) abolished the RDAs through the Pubic Bodies Act 2011 and introduced Local Enterprise Partnerships (LEPs), the remit of which was to define local economic priorities and lead economic growth and job creation within their local areas, to which LEPs could apply for finances.[16] This replacement of a regional tier of government with a sub-regional tier presented implications for democratic accountability and efficiency: councils are able to join more than one LEP, and the new LEPs are made up of unelected individuals and, as organisations, lack a formalised role and legal powers to effect change.[17]

The former Chancellor, George Osborne, in order to address England as the 'unfinished business' of devolution in the United Kingdom[18] laid out a long-term, purportedly radical agenda for local government to build upon the progress of City deals and Growth deals - prosperity through partnerships - which were intended to increase the capacity of local civic and business leaders to identify local economic needs and promote growth. The legal framework within which these changes were

- 149/150 -

to be implemented took the form of The Cities and Local Government Devolution Act 2016. The Act gave effect to the Greater Manchester Combined Authority while providing statutory authority for the rest of England to enter into negotiations with The Cities and Local Growth Unit, HM Treasury and officials from the Department for Business, Innovation & Skills to agree on a set of devolved powers and responsibilities from central government, through a 'Devolution Deal', to create a combined authority of local councils within a functional economic area.[19]

The 2016 Act does not provide any detail or prescription of which powers are to be devolved. It is here that the Act has the potential to enable what central government has coined a 'bespoke devolution', whereby local councils can join together to negotiate the terms of devolution to their combined authority on an area-by-area basis.[20] In a speech to the Conservative Party Conference in 2015, then Chancellor - and prominent advocate of the current devolution agenda in England - George Osborne, promised 'the biggest transfer of power to our local government in living memory' and challenged all who were listening to 'let the devolution revolution begin'.

V. Territorial relations and identity

The reform debate in England has long been dominated by the dichotomy of representation and efficiency.[21] Numerous studies have explored territorial reforms and the resulting patterns of conflict.[22] While there is extensive academic literature addressing the development of local governance, partnerships and networks,[23] it would seem that, in parallel with the increasing focus on the governance relations between the public and private spheres, one key element of local governance has been somewhat overlooked; the relations between local political actors across existing boundaries and, by extension, how central policy change affects these relations.

- 150/151 -

Zimmerman[24] notes the need for 'double legitimacy' for any new form of government. For this reason, a new identity needs to be instilled. This had previously failed with the introduction of the aforementioned RDAs. For most people, there was no identification with those bodies, and that they were non-elected merely increased the degree of separation. Instead of this 'double legitimacy', there is instead a fear of further amalgamation and re-organisation, as the lower tiers of government feel increasingly threatened by the introduction of combined authorities. The belief, mistaken or otherwise, is that the creation of a new tier of government may be at their expense. Even so, that closeness of contact between the public and 'government' tends to be through that lower tier. It is the territorial identifier to which people tend to attach themselves.

One of the salient issues that has emerged through the process of creating the new combined authorities in England is the issue of identity. The existence of distinct regional identities in England is not universal. In some instances, such as the West Midlands and the North of England, regional identity is clearly identifiable and naturally occurring, having developed historically and is rooted in a sense of collective memory.[25] On the other hand, there are 'regions' of England which are founded on artificial boundaries which serve a purely administrative and strategic purpose - one such example being the East Midlands.[26] There is an extensive literature covering different aspects of 'identity' from different academic disciplines and perspectives, notably (political) geography, history, sociology and psychology. While acknowledging all of that literature, one aim of this paper is to touch briefly upon the idea of territorial and regional identity. The notion of 'territorial identity' has been extensively researched and developed, particularly within the context of the European Union and regional governance.[27] For the purposes of this paper, the concept of 'identity' and, more specifically, 'territorial identity', is borrowed from scholars such as Paasi,[28] who defines 'regional identity' as a process of formalising 'territorial boundaries, symbolism and institutions'.[29]

In light of the considerations given thus far to the policy context of territorial rescaling in England, the development of devolution reforms and the salience of

- 151/152 -

territorial relations and identity, the next section of the paper will now turn to the empirical case being examined, Leicester and Leicestershire.

VI. The case of Leicester and Leicestershire

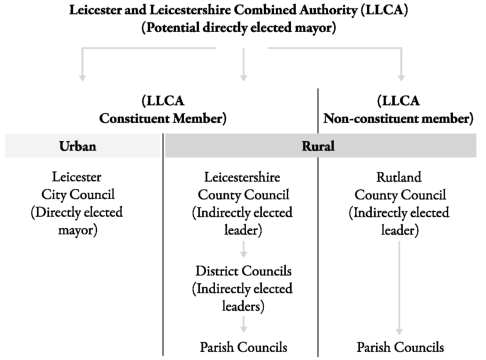

In December 2015, the city council, county council and all seven district councils, together with the Leicester and Leicestershire Local Enterprise Partnership, submitted a prospectus for a Leicester and Leicestershire Combined Authority (LLCA). The proposal, branded beneath the slogan 'Leicester and Leicestershire: Delivering Growth Together', sets out plans for a combined authority which would seek to obtain, through a devolution deal with central government, additional powers and funding from central government to stimulate economic growth, develop transport and infrastructure and address issues surrounding skills and employment. The proposed name of the LLCA was indicative of the dominant role that the city and county have taken in formulating this new governance structure. This dominant role is also reflected through a proposed operating agreement for the LLCA, which outlined key statutory and non-statutory administrative roles and from which councils within the LLCA that individuals for such roles would be drawn. As such, it was proposed that these senior administrative and managerial roles would be entirely appointed from either the county council or the city council. The proposed governance structure of the LLCA is outlined in Figure 2.

When examining the city of Leicester and the surrounding county of Leicestershire, a number of issues arise. There is a clear urban-rural divide. This is not simply city versus county, but any urban areas, including the likes of Loughborough, Market Harborough an Shepshed. Those in the city tend to lump everyone else together. If you are not in the city, you are county. This is not reciprocated. The idea of there being a 'Leicestershire' territorial identity is not clear. Rather, there is a degree of identity with the lower tier of council - the closest tier of government to the people. Such a geographical territorial identity is not new, especially at a regional level.[30] Thus, it could be expected for people across the region to identify with the newly proposed body. In reality, the 'political' identities of the city of Leicester, and those of the lower tier authorities appear much more profound.

- 152/153 -

Figure 2. The proposed structure of the Leicester and Leicestershire Combined Authority

Source: designed for this paper

1. Territorial relations: turfwars

Interviews with councillors confirmed the notion that political relations between councils in two-tier areas can be problematic and characterised by tension and conflict, which, as we have seen from our assessment of the ongoing policy debate, is often attributed to 'ambitions and fears' over boundaries between tiers that experience different levels of influence and autonomy. When asked to comment on whether the current devolution process and the prospect of a combined authority has affected, positively or negatively, the relationships between the borough, county and city councils, it began to emerge that, even prior to devolution being discussed, the relationships between the county and the districts showed a greater degree of tension and conflict than the relationship between the city and the county and/or districts. As one city councillor highlighted:

- 153/154 -

You often find loggerheads with the county councillors and district councillors, even those within the same party; they fight behind the scenes, swearing at each other. The district councillors like to have a go at the big boys with the big boots. (City Councillor)

The interviews conducted with district councillors highlighted in particular a distinct fear that, despite devolution policy broadly being a joint effort between councils to establish a combined governance structure (and, as such, a move away from previously formalised amalgamations of local authorities), the introduction of a combined authority would lead to the upper tier (the county) dominating and centralising services and functions away from the lower tier. As one councillor summarised, thus:

I can't begin to tell you how opposed the county council were to Leicester becoming unitary. You just would not believe the tactics that were used at that time. It was appalling, frankly. So, I doubt very much that's its changed sufficiently for the county to willingly devolve services to boroughs. Terefore, a unitary, erm, sorry [...] devolution in Leicestershire would be about the county taking control and I would be strongly opposed to that because it's taking services away. (District Councillor)

As such, the research has highlighted that the policy rhetoric surrounding the 'revolutionary' devolution process currently taking place in England, which boasts a promise of bespoke and radical reforms resulting in bottom-up solutions to be developed between councils is, in some instances, instead resulting in the reemergence of old and circular debates about reorganisation, particularly in favour of larger, unitary units of local government. The (re)emerging fear among district councillors extended as far as the county wanting to abolish districts entirely, in favour of a single unitary authority to cover the entire county of Leicestershire, resulting in a reduction of the number of councillors representing residents within the county. Some district councillors described what they perceived to be a clear message from the county council of such intentions, as expressed by one councillor:

I think so because I think, I'm thinking of one particular county councillor, who has made it quite clear that he wants unitary [...] that's what it looks like to me. (District Councillor)

The hostility between tiers over their territorial turf and any consequent desire for reorganisation was not simply top-down. Indeed, district councillors, as the lower tier, expressed a view that the county council could be abolished entirely, leaving only the smaller districts to provide services across the county at smaller scales, as smaller units of local government. Interestingly, some district councillors were not outrightly

- 154/155 -

opposed to the idea of combining existing authorities, but more opposed to the outcome being shaped from above by both the city and the county. The source of conflict for district councillors is less about change and more about a perceived urban and county imperialism. As one councillor highlights it:

We could abolish the county council; there might be some other boroughs that we'd have to combine where they're not big enough and we could share services where it was appropriate, we could buy them from other districts. (District Councillor)

What has emerged from the research is that, of those city councillors interviewed, there was a clear trend that distinguished those who had previously sat simultaneously on both the county council and the city borough (as 'twin-hatters) prior to the 90s reforms, and those who had not. Those who had were markedly more in favour of abolishing district councils and amalgamating Leicestershire and its districts into one unitary county. Those who had not experienced either did not have a view or were clearly opposed to the idea.

In the case of Leicester and Leicestershire, these conflictual conversations of reorganisation, much like the devolution proposal, which was developed for the LLCA, is led predominantly by the county and the city, at the expense of the districts. The process is perceived as 'devolution going on "up there" but we can't reach for it because it's being kept at a distance from us' (District Councillor). The city of Leicester is seemingly immune from any calls for amalgamation, seen as the distinct urban centre by its rural counterparts. Some councillors highlighted by political interdependence between the city and the county through their similar levels of autonomy and remit for service delivery and decision-making. As such, the political relationship between the city and county is stronger, despite the stark contrast of their party politics, than between the county and the districts which, by comparison, are broadly homogenous in partisan terms.

2. The dichotomy of representation and efficiency

The circular dichotomy of efficiency and representation, which has dominated central policy debates of local government reform in England, was reflected in how the local political elite have responded to the new devolution reforms. More specifically, a distinction became apparent where councillors at different levels were providing a rationale underpinning their views on what the future structure of local government should look like in Leicester and Leicestershire. The way in which individual councillors attempt to reconcile the dichotomy of efficiency vs. representation appears, albeit broadly, to correlate with the tier of local government at which they operate. These distinct views

- 155/156 -

can be categorised into three general groups. First, there are those councillors, serving at the county level, who wish to see larger units of local government and who favour cost savings and efficiency. This view is articulated by one councillor thus:

There is the potential for positive results if we were to reorganise and amalgamate. We could achieve greater efficiencies through synergy of back office functions; we could reduce bureaucracy, and eliminate duplication through the removal of dual hatted councillors, which the public do not often understand in any case. (County Councillor)

Second, there are those councillors - predominantly district councillors - who wish to retain smaller units of local government. These councillors were primarily concerned with ensuring sufficient representation of their local communities, which was seen as a more worthwhile pursuit than achieving cost savings and efficiencies through larger units of local government. As one district councillor commented:

In the end, I am not convinced but I don't know, because the figures have never been presented to me, but I am not convinced that, in the end, it would save that much money and we would lose an awful lot in terms of the big things like democracy. It would be much less democratic and we would have things that are vitally important to local people like planning being dealt with at county where you would have officers who have never set foot in the area deciding about planning in areas that they know nothing about. (District Councillor)

The final group of councillors are those who did not appear to have a strong view on whether the structure of local government should change. They place very similar amounts of value upon ensuring that structures of local government are efficient and cost-effective, and also safeguarding the adequate representation of local areas and that their identities retain relevance and influence in decision-making processes. This group broadly consisted of city councillors (except for those who were former 'twin-hatters').

3. Challenging senses of identity

One of the starkest trends among district councillors was the way in which they perceived the prospect of the combined authority to be a direct challenge to the local areas they represent, the identities of localities they serve and the relevance of the tier of local government of which they are an elected member. A number of district councillors expressed their agreement when questioned about whether they felt the new combined

- 156/157 -

authority structure would draw powers up from the lower tier rather than draw them down from central government.

There was a consensus among all the councillors interviewed, at all tiers, that the areas they represent have a strong sense of local identity within their current administrative boundaries. Even in the case of the city, councillors expressed a view that residents are more inclined to identify with their ward or suburb, rather than the wider city of Leicester, a view summarised by one city councillor:

Residents in my ward don't say they're from Leicester or from the city. They usually say they're from [city ward anonymised] or even from their neighbourhood. There's small pockets of communities within the city itself. People looking at the city from the outside might assume the city has one identity but local residents might say otherwise. (City Councillor)

The existence of twin and in some cases triple hatters - where a councillor sits on a principal authority (or two principal authorities) and a district and/or council - makes the relationships between different tiers of local government somewhat more difficult. What emerged from interviews with councillors was that where a district councillor sits on both the district and their local parish or town council, the concerns they have about the impact upon their local area of a new combined authority structure is somewhat intensified.

Some of the district councillors we interviewed were 'twin-hatted', in that they sit on both the district council and the local parish council. A prominent concern for these councillors was that the distance between those making decisions which impact upon their local area and the residents they serve in those areas would be increased drastically as a result of the creation of a combined authority. As two councillors commented:

Particularly out in the villages where it's very local and if they can't access a person face to face who they know, they get quite distraught. We're [Councillor B] both on the parish council together as well and this comes through very much at that level. (District Councillor)

That county even at the moment is there and we are here and we are dealing with everyday problems in the borough and in the wards. We can bring it into here, we can bring it into the offices here and actually get something done; we can use leverage. (District Councillor)

Councillors struggled to provide an explanation of the identity that was displayed by the combined authority for district councillors, the combined authority is perceived to

- 157/158 -

only represent city and county interests. City councillors took a more holistic view. The issue of identity was less salient for county councillors. While there was a recognition that different parts of the county of Leicestershire have their own senses of identity - particularly towns and smaller urban centres - there was less concern at this upper level that the introduction of a combined authority would have a tangible impact on their importance and relevance.

As highlighted by parallel research conducted with district councils across the whole of England for the All Party Parliamentary Group for District Councils, many of the new combined authorities are utilising Functional Economic Areas (FEAs) as the most suitable geographical scale for the development of these new structures. These 'natural' economic geographies go beyond and across historical administrative boundaries, in favour of reflecting patterns of economic activity. Many districts provided evidence of how delivering different services at the right spatial level is viewed as an opportunity wherein devolution could lead to more sustainable models of public service provision. While this rationale for the development of combined authorities at a sub-regional level serves an administrative purpose (they are 'natural' in that they reflect the clustered economic demands of regional areas), this does not appear to resonate at the most local level. These new and artificial structures exist at such a distance from local communities that there is a danger that senses of identity and place become subsumed and somewhat lost. Our research with councillors suggests that, as we move further away from the new structure and towards local communities, this concern is more prevalent.

VII. Conclusion

The current devolution process playing out in England is a relatively new approach to metropolitan governance and decentralisation. Whilst previous reforms to local government in England have, in large volumes, attempted to alter the role, shape and scope of local government, none has attempted to do so across groups of local authorities and in direct tension with existing territorial identities and administrative boundaries. The current devolution process in England therefore presents us with a new contested space for local and regional politics to play out within.

The aim of this paper has been to examine the impact that the process of establishing combined authorities has had on existing political relations between local authorities and senses of identity on an empirical basis. The research has demonstrated how this process rests upon but also can have a significant impact on local politics.

In the case of Leicester and Leicestershire, the process of shaping and establishing a combined authority as part of the new legal framework for devolution has had a significant impact on existing relationships between the city, county and

- 158/159 -

district councils involved in this new structure. The city and county councils have taken a leading role in driving the combined authority forward. For the district councils, as the lower tiers of local government, the process has intensified existing fears about their existence and a desire from the upper tier to abolish and amalgamate existing structures of local government. As such, the devolution process has failed to deliver on a central promise of 'bespoke' and 'bottom up' solutions which step away from previous reforms. Rather, the devolution process has intensified existing conflicts and stimulated a local response to the policy which centres on reorganisation and circular debates about efficiency versus representation. ■

NOTES

[1] C. Copus, M. Roberts and R. Wall, Local Government in England: Centralisation, Autonomy and Control (Palgrave, London, 2017), https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-26418-3; R. Wall and N. Vilela Bessa, Deal or no deal: English devolution, a top-down approach, (2016) 14 (3) Lex Localis Journal of Local Self-Government, 657-672, https://doi.org/10.4335/14.3.655-670(2016)

[2] H. Baldersheim and L. Rose, Territorial Choice: The Politics of Boundaries and Borders (MacMillan, Hampshire, 2010), https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230289826

[3] J. Stewart, An era of continuing change: reflections on local government in England 1974-2014, (2014) 40 (6) Local Government Studies, 835-850, https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2014.959842; P. John, The Great Survivor: The Persistence and Resilience of English Local Government, (2014) 40 (5) Local Government Studies, 687-704, https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2014.891984; H. Elcock, J. Fenwick and J. McMillan, The reorganization addiction in local government: unitary councils for England, (2010) 30 (6) Public Money & Management, 331-338, https://doi.org/10.1080/09540962.2010.525000

[4] M. Chisholm, Structural Reform of British Local Government: rhetoric and reality (Manchester University Press, Manchester, 2000); HMSO, Committee of Inquiry into the Conduct of Local Authority Business (Widdicombe Committee), Research Vol. II (The Local Government Councillor, Cmnd 9799, London, 1986); N. Flynn, S. Leach and C. Vielba, Abolition or Reform? Greater London Council and the Metropolitan County Councils (Harper Collins, London, 1985); HMSO, Committee on the Management of Local Government, (Maudreport), Research Vol. II (The Local Government Councillor, London, 1967).

[5] Copus et al., Local Government in England...

[6] Stewart, An era of continuing change... 835-850.

[7] Ibid; M. Chisholm, Emerging realities oflocal government reorganization, (2010) 30 (3) Public Money & Management, 143-150, https://doi.org/10.1080/09540960903513847; Elcock et al., The reorganization addiction in local government., 331-338.

[8] S. Weir and D. Beetham, Political Power and Democratic Control in Britain: The Democratic Audit of Great Britain (Routledge, London, 1999).

[9] J. B. Carr, Chapter 10: Whose Game Do We Play? Local Government Boundary Change and Metropolitan Governance, in R. Feiock, Metropolitan Governance: Conflict, Competition and Cooperation (Georgetown University Press, 2010) 296-332.

[10] J. A. Chandler, Explaining Local Government: Local Government in Britain Since 1800 (Manchester University Press, Manchester, 2007), https://doi.org/10.7228/manchester/9780719067068.001.0001

[11] S. Leach, The transfer of power from metropolitan counties to districts: An analysis, (1987) 13 (2) Local Government Studies, 31-48, https://doi.org/10.1080/03003938708433329; A. Coulson, Economic Development - The Metropolitan Counties 1974-1986, (1990) 16 (3) Local Government Studies, 89-104, https://doi.org/10.1080/03003939008433527

[12] S. Leach, and H. Davis, The Operation of the Metropolitan Passenger Transport Authorities since 1986, (1991) 11 (1) Public Policy and Management, 51-56, https://doi.org/10.1080/09540969109387642

[13] D. Kubler, Introduction: Metropolitanisation and Metropolitan Governance, (2012) 11 (3) European Political Science, 402, https://doi.org/10.1057/eps.2011.41

[14] C. Copus, Leading the localities: executive mayors in English local governance (Manchester University Press, Manchester, 2006), https://doi.org/10.7228/manchester/9780719071867.001.0001

[15] V. Lowndes and A. Gardner, Local Governance under the Conservatives: super-austerity, devolution and the 'smarter state', (2016) 42 (3) Local Government Studies, 357-375, https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2016.1150837; D. Richards and M. Smith, Devolution in England, the British Political Tradition and the Absence of Consultation, Consensus and Consideration, (2016) 51 (4) Representation, 385-401, https://doi.org/10.1080/00344893.2016.1165505

[16] John, The Great Survivor..., 687-704.

[17] J. Morphet and S. Pemberton, 'Regions Out - Sub-Regions In' - Can Sub-Regional Planning Break the Mould? The View from England, (2013) 28 (4) Planning Practice and Research, 384-399, https://doi.org/10.1080/02697459.2013.767670

[18] C. Jeffery, The Unfinished Business of Devolution, (2007) 22 (1) Public Policy and Administration, 92-108, https://doi.org/10.1177/0952076707071506

[19] F. Gains, Metro Mayors: Devolution, Democracy and the Importance of Getting the 'Devo Manc' Design Right, (2016) 51 (4) Representation, 425-437. https://doi.org/10.1080/00344893.2016.1165511

[20] HM Government, The Cities and Local Government Devolution Act 2016 (The Stationary Office, London, 2016).

[21] Copus et al., Local Government in England...; H. Elcock, Local Government: Policy and Management in Local Authorities (Routledge, London, 1994); J. Dearlove, The reorganisation of British Local Government: Old Orthodoxies and a Political Perspective (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1979).

[22] Baldersheim and Rose, Territorial Choice...; M. Keating, The New Regionalism in Western Europe: Territorial Restructuring and Political Change (Edward Elgar, 1998); S. Lansley, S. Goss and C. Wolmar, Councils in Conflict: The Rise and Fall of the Municipal Left (Macmillan, Hampshire, 1989), https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-349-20231-7

[23] B. Denters and L. Rose, Comparing Local Governance: Trends and Developments (Palgrave MacMillan, London, 2005); S. Goss, Making Local Governance Work: Networks, Relationships and the Management of Change (Palgrave, London, 2001); R. Rhodes, Understanding Governance: Policy Networks, Governance, Reflexivity and Accountability (Open University Press, 1997).

[24] K. Zimmerman, Democratic Metropolitan Governance: Experiences in Five German Metropolitan Regions, (2014) 7 (2) Urban Research and Practice, 182-199, https://doi.org/10.1080/17535069.2014.910923

[25] M. Halbwachs, On Collective Memory (University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1992), https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226774497.001.0001

[26] I. Hardill, P. Bennetworth, M Baker and L. Budd, The Rise of the English Regions? (Routledge, London, 2006), https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203421505

[27] M. Keating, Thirty Years of Territorial Politics, (2008) 31 (1-2) West European Politics, 60-81, https://doi.org/10.1080/01402380701833723

[28] A. Paasi, Region and Place: Regional Identity in Question, (2003) 28 (4) Progress in Human Geography, 475-485, https://doi.org/10.1191/0309132503ph439pr

[29] Ibid.

[30] Ibid.

Lábjegyzetek:

[1] The Author is PhD Researcher, Local Governance Research Unit, De Montfort University Leicester.

[2] The Author is Senior Lecturer, Local Governance Research Unit, De Montfort University Leicester.