Dr. Thi My Linh Nguyen - Dr. Thi Truc Giang Huynh - LLM. Khac Qui Tran[1]: Empowering Women's rights in the Digital Age - A comparative analysis of Vietnam and International Standards* (JURA, 2024/4., 36-48. o.)

The rapid development of digital technologies in the fourth industrial revolution has brought both opportunities and challenges, especially for women's rights in cyberspace. Women enjoy the values and benefits of advances in digital technology but also face significant risks such as cyber violence and privacy violations. This article examines Vietnam's legal framework for protecting women's rights in the digital age and compares it with international legal standards. The article emphasizes the importance of amending and supplementing the law to protect women from acts of violence and privacy violations in cyberspace, ensuring their safe and equal participation in the digital environment. In addition, the study also analyzes the critical role of international and European conventions in shaping global legal standards. This work proposes solutions to improve Vietnam's legal framework to protect women's rights in the digital age.

I. Introduction

The Fourth Industrial Revolution has been taking place firmly on a global scale. The development of several breakthrough technologies in the Fourth Industrial Revolution, such as artificial intelligence (AI), 5G network technology, and biotechnology, has strongly impacted all aspects, from security and politics to the economy and society.[1] In the context of the digital technology revolution that is developing strongly in all areas of social life, the issue of protecting women's rights in the online environment is becoming increasingly urgent. Women not only benefit from technological advances but also face many potential risks, such as violence and privacy violations in cyberspace.

Researching and proposing solutions to protect women's rights in the digital environment is necessary and urgent to ensure societal safety and equality. Women need to be protected from cyber violence and have their privacy guaranteed in the context of digital globalization. This is a human

- 36/37 -

rights issue and an essential factor in promoting sustainable development and social justice. Therefore, further research is needed to identify better the challenges and opportunities women face in the digital age. Consequently, it is necessary to study Vietnam's legal regulations on protecting women's rights online compared to international standards to assess the strengths and weaknesses of Vietnamese law, thereby making recommendations to improve the legal framework.

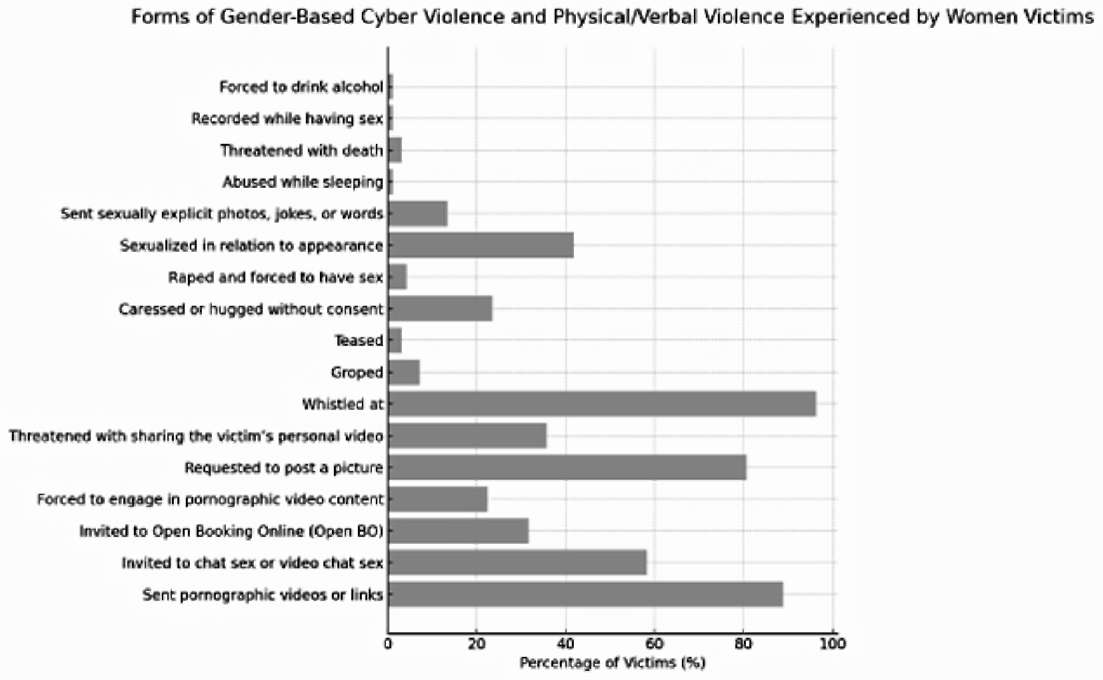

Figure 1: Forms of Gender-Based Cyber Violence and Physical and Verbal Violence in Indonesia Experienced by Women Victims[2]

The article will focus on essential concepts such as "cyberbullying" and "invasion of privacy" against women and compare international legal standards for the issue of ensuring women's rights in cyberspace. Specifically, the concept of "cyberbullying" is the use of cyberspace to harm or threaten others, especially by sending them unpleasant messages.[3] This can include harassment, threats, defamation, or violation of women's dignity and honor in online space. In addition, "invasion of privacy" is an act of unjustified invasion of another person's privacy by appropriating that person's name or image, by unreasonably interfering with that person's isolation, by publicizing information about that person's private matters that a reasonable person would find objectionable and without legitimate public interest, or by unreasonably publicizing information that causes that person to be misunderstood.[4] These concepts will be the basis for analyzing and comparing Vietnamese law and international standards. Thus, ensuring women's rights in the

- 37/38 -

digital age means that women must be equal, safe, and secure.

Figure 2: Reporting sexual harassment online to law enforcement agencies in Pakistan in 2017 conducted by Hamara Internet

Many international organizations, such as the United Nations (UN) and UN Women, have pioneered research and recommendations on protecting women in cyberspace. These studies not only identify the prevalence of cyber violence but also emphasize the need to strengthen existing legal frameworks.[5] According to UN Women's research, about 73% of women experience online violence at least once in their lives.[6] Cyber violence, such as harassment, abuse of personal information, defamation, and cyberbullying[7], not only causes mental harm but also seriously affects their lives, work, and safety (Figure 1).[8] In this situation, the development of a legal framework to protect women from cyber violence is gradually gaining attention in many places around the world.[9] In Vietnam, although research on this issue is limited, there are still bare and necessary regulations in developing a legal framework to protect women's rights against risks from cyberspace.

There have been many studies around the world related to protecting women from online violence and privacy violations. In a 2018 survey on gender-based violence and unwanted sexual behavior in Canada, one in five women (18%) said they had been harassed online.[10] In Pakistan, 40% of women reported various forms of online harassment in 2017, according to a survey conducted by Hamara Internet. In the same study, 70% of women said that when they were harassed online, they would not report the incident to the Federal Investigation Agency (FIA) of Pakistan, 11% did not report it because they thought it would not help, and only 15% chose to report it to the FIA (Figure 2).[11]

In Vietnam, according to a 2023 survey by the Program for Internet and Society Studies (VPIS, University of Social Sciences and Humanities), 78% of internet users confirmed that they had been victims or knew of cases of hate speech on social networks; 61.7% had witnessed or become victims of slander, defamation, and defamation,

- 38/39 -

and 46.6% had been slandered or fabricated information.[12] However, only some studies have compared Vietnamese law and international standards for protecting women's rights in the digital age. This article aims to overcome these shortcomings by analyzing international legal frameworks and comparing them with Vietnamese law.

The article will use legal analysis methods to evaluate and compare international and regional legal regulations on protecting women's rights in the digital environment and compare them with the current legal framework in Vietnam. The main contents of the article include analyzing international legal regulations, analyzing legal regulations, assessing the application situation in Vietnam, and proposing solutions to improve the law to protect women's rights more effectively in the context of global digitalization.

II. International laws governing the protection of women's rights online

The legal framework related to the protection of women's rights against violence and gender equality and ensuring cyber security includes the following typical international and regional conventions: i) Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW)[13]; ii) Istanbul Convention[14]; iii) Maputo Protocol[15]; iv) Inter-American Convention on the Prevention, Punishment and Eradication of Violence against Women (Belem do Pará Convention )[16]; v) Budapest Convention on Cybercrime[17]; vi) General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR)[18]; vii) Guidelines for Consumer Protection in the Digital Environment by the United Nations[19]; viii) Global Telecommunications and Cybersecurity Regulation adopted by the International Union (ITRs )[20]; ix) Resolution of the Human Rights Council on Accelerating Efforts to Eliminate Violence Against Women and Girls: Preventing and responding to violence against women and girls with women and girls in the digital context[21]; x) The UN's 2030 Agenda[22] with 17 sustainable development goals, including the goal of ensuring gender equality towards a more equitable and prosperous society by 2030.

From the perspective of an international convention issued by the United Nations, CEDAW has a vast influence due to the number of member states that have ratified it. However, CEDAW only issues provisions on the protection of women and anti-discrimination, which can be fully applied to protect women's rights in cyberspace. At the regional level, the Belém do Pará Convention, the Istanbul Convention, and the Maputo Protocol, which are influenced by the Pan-American, European, and African spheres, respectively, all recognize the issue of protecting women's rights against violence and gender equality. Similarly, the above regional conventions and protocols do not directly regulate the protection of women's rights in the online environment but do not limit the scope of protection.

In the field of network environment, The 2018 United Nations Human

- 39/40 -

Rights Council resolution directly addresses the protection of women and children from violence online. The resolution lists harassment, stalking, bullying, threats of sexual and gender-based violence, death threats, arbitrary or unlawful surveillance and tracking, human trafficking, extortion, censorship, and hacking of digital accounts, mobile phones, and other electronic devices as forms of violations, abuse, discrimination and violence faced by women in the digital context. The resolution also calls on businesses to implement the Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, protect the privacy of women and girls, create transparent and effective processes for reporting violence, and develop policies to protect women and girls from violence in the digital context. It can be said that the resolution has pointed out current forms of violence against women and children in the online environment and set out principles that businesses operating in the online environment need to implement to protect women and children.

In addition, the Budapest Convention, GDPR, and ITRs, respectively, also indicate the acts considered as cybercrimes and provide principles to ensure a safe digital environment, protect personal data, and protect consumer rights in the digital environment. These documents do not directly regulate the protection of women but protect all subjects of violations towards a safe online environment and respect for privacy and personal data. For example, the Budapest Convention (Articles 2, 3, 5, 8, and 10) indicates acts considered cybercrimes, such as harassment, cyber violence, applications with user tracking features, and stealing user information.[23] Sociological studies, in particular, show that women are more likely to be targeted by social media trolls and online abuse. While both men and women are vulnerable online, women are more likely to experience abuse and are more severely affected.[24]

In summary, international and regional conventions recognize the importance of protecting women's rights against violence and inequality. The fact that member countries participate in signing and ratifying international and regional conventions shows that member countries recognize the critical role of state policies, telecommunications service providers, and authorities in promoting social, spiritual, and moral interests and women's physical and mental health. This shows the importance of protecting women against information and behaviors that are harmful to women online, requiring the joint efforts of both the public and private sectors in each country.

III. Vietnamese law regulates the protection of women's rights online

1. Vietnam's legal framework for protecting women's rights online

In the context of the rapid development of information technology, in addition to the promulgated regulations such as the Constitution, Civil Code, and Penal Code, Vietnam has issued the Law

- 40/41 -

on Cyber Security and sub-law documents to protect civil rights in general and women's rights in cyberspace. This legal framework not only protects women from violence, harassment, and privacy violations but also encourages their participation in the technology sector. This shows that Vietnam is serious about implementing its commitment to protecting women's rights, thereby making an essential contribution to building a fair and sustainable digital society. Some crucial documents contributing to the protection of women's rights in cyberspace include the following:

The 2013 Constitution safeguards women's rights in cyberspace through its provisions on human rights and equality. Specifically, Article 21 of the Constitution states that all citizens, including women, have the right to protect their honor, dignity, and privacy. Furthermore, Article 16 guarantees the equality of all citizens before the law and explicitly prohibits all forms of discrimination.

The 2015 Civil Code protects women's rights in cyberspace through honor, dignity, and privacy provisions. Articles 34 and 25 affirm the right to preserve honor, reputation, and dignity in the online environment. Article 38 protects the right to privacy, stating that disclosing personal information without consent violates this right. Thanks to these provisions, women have a legal basis to request protection of their rights when they are violated on social networks.

The 2015 Penal Code (amended and supplemented in 2017) stipulates crimes related to violence, sex, and the dissemination of private images without consent, along with other acts such as human trafficking and illegal use of network information, thereby ensuring women's rights in the online environment.

The 2018 Cybersecurity Law protects women's rights online by ensuring information security and personal rights. It provides measures to combat cyber violence, harassment, and discrimination and requires personal data protection. This creates a safe online environment, encourages women to participate and access information equally, and enhances women's presence and voice.

In addition, sub-law documents such as Decree 13/2023/ND-CP on personal data protection also protect women's rights online by requiring consent when collecting and processing personal data and prohibiting unauthorized disclosure of information. The Decree allows women to request correction or deletion of personal data, helping to prevent privacy violations, harassment, and discrimination, ensuring safety and equality online.

2. Content to protect women's rights online

Based on the analysis of international legal provisions on the protection of women's rights in the online environment and the overview of Vietnam's relevant legal framework mentioned above, this section will delve into clarifying the detailed contents of Vietnamese law in two aspects: (i) protecting

- 41/42 -

women from cyber violence, (ii) ensuring women's privacy.

Protecting women from cyber violence has become an urgent necessity in the context of rapid technological advancements. In Vietnam, the National Assembly has made significant efforts to develop and improve legal regulations aimed at protecting women from cyber violence. These efforts are reflected in Article 16 of the 2013 Constitution and

Article 34 of the 2015 Civil Code, which recognize citizens' right to protect their honor, dignity, and reputation. These provisions implicitly extend to protecting women from acts of cyber violence, as such acts can have a profound impact on their honor and dignity.

Furthermore, the 2018 Law on Cyber Security contains specific provisions to safeguard women's rights in the online environment. For instance, Article 15 explicitly prohibits acts such as cyber violence, sexual harassment, and conduct that insults personal dignity and honor.

Additionally, the 2015 Penal Code, as amended and supplemented, includes various provisions addressing crimes related to violence, many of which apply to acts committed via digital platforms:

i) Article 155: Crime of Humiliating Others - This article addresses actions that insult the honor and dignity of others through words or deeds. While it does not explicitly mention social networks, using computer networks or electronic devices to commit such crimes is aggravating under Paragraph 2(e). Penalties for this crime range from non-custodial reform for up to 3 years to imprisonment from 3 months to 2 years, depending on the severity of the offense.

ii) Article 156: Crime of Slander - This article deals with acts of disseminating false information to seriously harm the dignity, honor, or legitimate rights and interests of others, including women. When committed via social networks or electronic media, such acts are punishable by imprisonment for 1 to 3 years, with penalties varying based on the circumstances.

iii) Article 133: Crime of Threatening to Kill - This article criminalizes acts of threatening to kill others, including women, whether through direct means or via social networks. The penalty for this offense ranges from 6 months to 3 years in prison, and in aggravating circumstances, it can increase to between 2 and 7 years.

These legal provisions highlight the importance of creating a robust legal framework to effectively address and prevent acts of cyber violence against women in Vietnam. However, continued efforts are required to further clarify and strengthen these laws in response to the evolving challenges posed by digital technology.

Protecting women's privacy on social media has become an increasingly urgent issue, particularly in the context of rising online violence and harassment. Research indicates that women are fre-

- 42/43 -

quently targeted for privacy violations, ranging from the unauthorized use of personal images to emotional abuse.[25] Moreover, privacy is not merely a personal matter but is deeply intertwined with human rights, imposing a responsibility on governments to safeguard it.

In Vietnam, the legal framework for protecting women's privacy in cyberspace is outlined in Article 21 of the 2013 Constitution. This article guarantees every individual the right to privacy and its protection, thereby establishing a legal foundation for addressing violations of women's privacy online. Any infringement of personal privacy is subject to legal penalties as stipulated by Vietnamese law. The personal rights provisions under Article 25 of the 2015 Civil Code further reinforce these protections. Since the right to privacy constitutes a personal right of women, any breach of this right entitles them to seek compensation as prescribed by the 2015 Civil Code. Additionally, Article 26 of the 2018 Law on Cybersecurity defines the rights and responsibilities of organizations and individuals in safeguarding personal information, serving as another legal basis for ensuring women's privacy on social media platforms. Furthermore, Article 8 of Decree 13/2023/ND-CP specifies prohibited activities related to the processing of personal data, including processing data without the consent of the individual or in violation of legal regulations. These provisions are particularly significant in protecting women's privacy and ensuring that their personal information remains secure in cyberspace.

With respect to sanctions, in addition to the direct provisions outlined in Article 288 of the 2015 Penal Code, which addresses the crime of illegally providing or using information on computer networks and telecommunications networks, as well as Article 289, which pertains to the crime of illegally accessing computer networks, telecommunications networks, or electronic devices of others, it is also possible to apply other related provisions, such as Article 155 (Crime of Humiliating Others) and Article 156 (Crime of Slander) [26]. These articles may be utilized to address violations of women's privacy in cyberspace.

For instance, consider a case where Mr. A secretly collects personal information about Ms. B, including private photographs and her home address, and subsequently posts this information on social media without her consent. Moreover, A accuses B of engaging in illegal activities, such as financial fraud, on his social media page. This conduct severely damages B's honor and reputation, causing her to suffer harassment from numerous strangers.

Under Article 288 of the 2015 Penal Code, A's actions constitute the crime of illegally providing or using information on computer networks and telecommunications networks, as he publicly disclosed B's personal information online without her consent. The penalty for this crime ranges from six months to three years of imprisonment. Additionally, if it is determined that A illegally accessed B's electronic device to obtain this private information, he/she may also be charged under Article

- 43/44 -

289, which criminalizes illegal intrusion into computer networks. Furthermore, A's behavior could be prosecuted under Article 155 (Crime of Humiliating Others) due to the dissemination of information that seriously insults B's honor and dignity. If it is established that A intentionally fabricated false information about B to harm her/his reputation, he/she could also face charges under Article 156 (Crime of Slander). Depending on the severity of the offense and the presence of aggravating circumstances, the penalty for slander ranges from three months to one year of imprisonment or more.

In summary, the Vietnamese legal system has established many regulations to protect women's rights to protection from violence and privacy in the online environment, as reflected in documents such as the Constitution, the Civil Code, the Law on Cyber Security, and Decree 13/2023/ND-CP.

These regulations affirm Vietnam's commitment to protecting women's rights and are consistent with international human rights standards. However, implementing the above rules to protect women's rights in cyberspace in Vietnam still faces many challenges. One of the major problems is the need for more education and awareness raising. Many people, especially women, must be fully informed about their rights in cyberspace. This leads to them not daring to speak up or needing to learn how to protect their rights when violated. In addition, the lack of uniformity in the legal system also creates difficulties in handling cases of privacy violations and cyber violence.

Furthermore, the ability to coordinate between authorities in enforcing legal regulations is limited. Law enforcement agencies must proactively monitor, detect, and handle violations. The establishment of reporting and victim support mechanisms also needs to be improved to make it easier for women to access and request protection.

IV. Recommendations for improving the protection of women's rights online for Vietnamese law to comply with international legal standards

In the digital age, women face many challenges online, from violence to privacy violations. Both Vietnamese and international laws ensure that women's rights are protected. However, Vietnam needs to continue to improve its legal framework to align with global standards and better protect women from challenges in the online environment.

1. The issue of cyber violence against women

Cyber violence against women is one of the most pressing issues in the digital age, manifesting itself in behaviors such as online sexual harassment, threats, and the spread of misinformation. These behaviors not only cause psychological harm but also undermine fundamental human rights, es-

- 44/45 -

pecially for women.[27] To address this issue, Vietnam needs to implement the following solutions:

Firstly, it is crucial to strengthen the legal framework addressing cyber violence.

Although the 2018 Law on Cyber Security outlines several prohibited acts related to cybersecurity and the 2015 Penal Code, as amended and supplemented in 2017, provides provisions on cybercrimes, additional specialized regulations are needed to effectively address cyber violence against women. In particular, it is imperative to explicitly define the various forms of online violence targeting women within the Law on Cyber Security.

Second, the government needs to increase the use of technology to support and protect women from cyber violence. There needs to be a mechanism to protect victims through the establishment of specialized agencies for preventing cyber violence and implementing psychological and legal support programs for affected women. Building a simple, fast, and reliable reporting process is necessary to encourage women to speak up. Some countries are applying artificial intelligence (AI) to protect women from cyber violence, including prominent programs in the North Africa and Middle East regions. For example, Egypt has developed HarassMap[28], an online tool that helps report and map sexual harassment incidents in real time. The application uses AI to analyze reporting data to identify dangerous areas and notify women to avoid those areas. In addition, the StreetPal application in Egypt allows women to send notifications to relatives and quickly connect to support agencies when necessary, helping to reduce the risk of harassment and helping to protect users in dangerous situations.[29]

The Securella app helps women stay alerted to dangerous streets in Morocco through secure connections to participating businesses or restaurants. This network allows users to trigger an alarm when in danger and receive support from these safe locations. These applications demonstrate how technology and AI can be deployed to support women in both online and offline environments, creating remote preventive measures that improve women's safety.[30]

Thirdly, efforts to promote education and communication about women's rights in cyberspace should be intensified through targeted awareness campaigns, with a particular focus on the role of civic education in the digital environment. Additionally, the Women's Union should play an active role in monitoring instances of cyber violence and providing support to victims.

2. Women's privacy issues

Privacy is a fundamental right that is particularly vulnerable to violations in cyberspace. For women, these violations become even more severe when personal information and private images are exploited and illegally distributed. Vietnamese law requires specific adjustments to better protect women's privacy in the digital age, as outlined below:

Firstly, it is crucial to strengthen the protection of online privacy. While the

- 45/46 -

2013 Constitution, the 2015 Civil Code, the 2018 Law on Cybersecurity, the 2015 Penal Code (amended and supplemented in 2017), and Decree 13/2023/ND-CP on personal data protection contain provisions on privacy, additional amendments and supplements are needed to enhance the protection of personal data. New regulations should prioritize the safeguarding of women's sensitive information, including images, health data, and personal information related to private life. There is a pressing need for a separate and specific provision within the Law on Cybersecurity to address the protection of women's privacy in cyberspace.

Second, the government needs to handle violations strictly. The government must strengthen penalties for breaches of privacy and ensure that laws clearly define the responsibilities of all involved parties, including social media platforms, in cases of violations. Acts such as the distribution of images or personal information without consent must be rigorously prosecuted and penalized to deter such offenses.

Third, Vietnam's authorities apply science and technology to protect privacy. Vietnamese authorities should leverage scientific and technological advancements to safeguard privacy. Drawing lessons from international legal frameworks, Vietnam can adopt measures such as advanced encryption technologies and enhanced security mechanisms developed by network service providers to protect women's privacy. Additionally, Vietnam should increase its participation in and implementation of international commitments to protect women's rights in the digital environment by ratifying and enforcing relevant conventions such as CEDAW and the Istanbul Convention.

Furthermore, many countries utilize artificial intelligence (AI) to enhance online privacy protection through both legal frameworks and technological innovations. For instance, the European Union (EU) has set an exemplary standard with the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and the AI Act. The GDPR requires explicit user consent for data collection and provides individuals with rights to access, correct, or delete their data. The AI Act, introduced in 2021, complements the GDPR by establishing safety and transparency requirements for AI systems and promoting ethical AI development that respects user privacy. By studying and adapting such practices, Vietnam can improve its legal framework to better protect women's privacy in cyberspace.[31]

V. Conclusion

In conclusion, Vietnam has taken significant steps in establishing a legal framework to protect women from cyber violence and uphold their privacy rights online, as seen in its Constitution, Civil Code, Law on Cyber Security, and recent decrees. These efforts reflect Vietnam's commitment to protecting women's rights and align with international human rights standards. However, implementation challenges include limited public awareness, legal inconsistencies, and difficulties in

- 46/47 -

enforcement coordination among authorities.

Addressing these issues requires further action: strengthening the legal framework on cyber violence, enhancing technology-based support systems, and promoting public education on women's rights in cyberspace. Additionally, Vietnam could benefit from international practices, such as the European Union's GDPR and AI regulations, which offer robust data protection standards. By adopting similar measures and refining current laws, Vietnam can better protect women's rights online, ensuring that legal protections evolve alongside technological advancements and conform to global standards. ■

NOTES

* This study is funded by the Can ho University, Code: CTCS2024-04-02.

[1] Nguyen Tuan Anh: Tac dong cua cuoc Cach mang cong nghiep lan thu tu den the giói, khu vuc va Viet Nam - Impact of the Fourth Industrial Revolution on the world, region and Vietnam. Communist Journal. Published online 2022. Accessed November 8, 2024. https://www.tapchicongsan.org.vn/web/guest/the-gioi-van-de-su-kien/-/2018/825809/tac-dong-cua-cuoc-cach-mang-cong-nghiep-lan-thu-tu-den-the-gioi%2C-khu-vuc-va-viet-nam.aspx.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Cambridge Dictionary: Cyberbullying, 2024. Accessed November 8, 2024. https://dictionary.cambridge.org/vi/dictionary/english/cyberbuUying#google_vignette.

[4] Invasion of privacy: The tort of unjustifiably intruding upon another's right to privacy by appropriating his or her name or likeness, by unreasonably interfering with his or her seclusion, by publicizing information about his or her private affairs that a reasonable person would find objectionable and in which there is no legitimate public interest, or by publicizing information that unreasonably places him or her in a false light.

[5] Powell A, Henry N: Sexual Violence in a Digital Age. Published online 2017. doi: https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-58047-4.

[6] UN Women: Technology-Facilitated Violence Against Women: Taking Stock of Evidence and Data Collection, 2023. Accessed November 8, 2024. https://www.unwomen.org/sites/default/files/2023-04/Technology-facilitated-violence-against-women-Taking-stock-of-evidence-and-data-collection-en.pdf.

[7] Mas'udah S, Razali A, Sholicha SMA, Febrianto PT, Susanti E, Budirahayu T. Gender-Based Cyber Violence: Forms, Impacts, and Strategies to Protect Women Victims. J Int Womens Stud. 2024;26(4). Accessed November 8, 2024. https://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws/vol26/iss4/5. See Article 5.

[8] Ibid.

[9] For example: United States, United Kingdom, Australia, Canada, European Union. See more: Law Obrien. Cyberbullying Laws: How Different Countries Address Online Harassment, 2024. Accessed November 8, 2024. https://www.lawobrien.com/cyberbullying-laws-how-different-countries-address-online-harassment/.

[10] The Daily: Gender-based violence and unwanted sexual behaviour in Canada, 2018: Initial findings from the Survey of Safety in Public and Private Spaces. Statistics Canada. 2019. Accessed November 8, 2024. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/191205/dq191205b-eng.pdf

[11] Hamara Internet: Measuring Pakistani Women's Experience of Online Violence, 2017. Accessed November 8, 2024. https://digitalrightsfoundation.pk/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/Hamara-Internet-Online-Harassment-Report.pdf.

[12] Khanh Minh: Hiem hoa tu bao luc mang - The danger of cyber violence, 2024. Accessed November 8, 2024. https://nhandan.vn/hiem-hoa-tu-bao-luc-mang-post797710.html.

[13] This international convention was adopted in 1979 by the United Nations General Assembly. The basic content of the convention refers to women's rights and the responsibility of states to ensure these rights, including protection from violence. To date, 189 countries have ratified the CEDAW convention. It can be downloaded from the link: https://treaties.un.org/pages/ViewDetails.aspx?src=IND&mtdsg_no=IV-8&chapter=4&clang=_fr#EndDec. See more: Zwingel S. From intergovernmental negotiations to (sub)national change. Int Fem J Polit. 2005;7(3):400-424. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1461674050016118; Englehart NA, Miller MK. The CEDAW Effect: International Law's Impact on Women's Rights. J Hum Rights. 2014;13(1). p.22-47. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14754835.2013.824274.

[14] Officially known as the Council of Europe Convention on Preventing and Combating Violence against Women and Domestic Violence, the

- 47/48 -

treaty aims to protect women from all forms of violence and ensure their safety. Download link: https://www.coe.int/en/web/conventions/full-list?module=signatures-by-treaty&treatynum=210. See more: McQuigg RJA. The Istanbul Convention, domestic violence and human rights. The Istanbul Convention, Domestic Violence and Human Rights. Published online September 19, 2017:1-183.

[15] Protocol to the African Charter on Human and Peoples' Rights on the Rights of Women in Africa, which contains provisions for the elimination of discrimination and violence against women. The Protocol has been signed by 43 African countries and ratified by 41.

[16] The regional convention was adopted by member states of the Organization of American States (OAS) in 1994 and recognizes the right of women to live free from violence and discrimination , and can be downloaded from the link: https://www.oas.org/juridico/english/sigs/a-61.html

[17] This is the first and only international treaty on cybercrime, adopted by the Council of Europe in 2001. It sets standards on cybercrime and international cooperation in the investigation and prosecution of cybercrime. It can be downloaded from the link: https://www.coe.int/en/web/cybercrime/the-budapest-convention

[18] This European Union regulation, which came into effect in 2018, protects the privacy and personal data of EU citizens. GDPR requires organizations to implement strict rules on data security and handling.

[19] The guidelines were issued by the United Nations and include principles on consumer protection in the digital environment, including privacy and information security.

[20] Adopted by the International Telecommunication Union (ITU), these regulations govern issues related to telecommunications and cybersecurity globally.

[21] Resolution adopted by the Human Rights Council in 2018, available for download at: https://documents.un.org/doc/undoc/gen/g18/214/82/pdf/g1821482.pdf.

[22] The 2030 Agenda was unanimously adopted by all members of the United Nations in 2015.

[23] Adriane van der Wilk: Protecting Women and Girls from Violence in the Digital Age, 2021. Accessed September 17, 2024. https://edoc.coe.int/en/violence-against-women/10686-protecting-women-and-girls-from-violence-in-the-digital-age.html#.

[24] J. Clement: Online Gaming Forms of Harassment in the U.S. by Identity 2023 | Statista, 2024. Accessed November 8, 2024. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1133194/harassment-video-games-identity/

[25] Mutambiki I, Lee J, Al Muqrin A, Zhang JZ, Baihan M, Alkhanifer A. Privacy Concerns in Social Commerce: The Impact of Gender. Sustainability 2023;15(17). p.12771. doi: https://doi.org/10.3390/SU151712771, See more: Im J, Schoenebeck S, Iriarte M, et al. Women's Perspectives on Harm and Justice after Online Harassment. Proc ACM Hum Comput Interact. 2022;6(2CSCW); Jackson EF, Bussey K, Trompeter N. Over and above Gender Differences in Cyberbullying: Relationship of Gender Typicality to Cyber Victimization and Perpetration in Adolescents. J Sch Violence. 2020;19(4). p623-635.

[26] This applies when false information about women is spread to harm their honor and reputation. Spreading rumors or false information can lead to serious injury, infringing on the victim's privacy.

[27] Nguyen Thi Thanh Thuy, Do Van Trong: An toan cho phu nur va tre em tren khong gian mang -Safety For Women And Children In Cyberspace. State Management Journal. 2023;(329). p.71-75. Accessed November 8, 2024. https://vi.quanlynhanuoc.vn/qlnn/article/view/555

[28] HarassMap official website: https://harassmap.org/en.

[29] UN Women: Accelerating Efforts to Tackle Online and Technology-Facilitated Violence Against Women and Girls, 2021. Accessed November 8, 2024. https://www.unwomen.org/sites/default/files/2022-10/Accelerating-efforts-to-tackle-online-and-technology-facilitated-violence-against-women-and-girls-en_0.pdf

[30] Al-Nasrawi S: Combating Cyber Violence Against Women and Girls: An Overview of the Legislative and Policy Reforms in the Arab Region. The Emerald International Handbook of Technology-Facilitated Violence and Abuse. Published online January 1, 2021. p.493-512. doi: https://doi.org/10.1108/978-1-83982-848-520211037

[31] Chin-Rothmann C: Protecting Data Privacy as a Baseline for Responsible AI. Published online 2024.

Lábjegyzetek:

[1] Faculty of Law, Can Tho University, Vietnam